Case presentation

A 64-year-old woman requested a second opinion after being diagnosed with incipient cognitive impairment of vascular origin. She was accompanied by her daughter, and explained an acute onset – 6 months prior – of a set of symptoms that they referred to as “disorientation.” Previously, the patient had never reported cognitive or behavioral problems of any kind and had an irrelevant medical history.

The first symptom presented, which was referred to as disorientation, consisted in the development of episodes of reduplicative paramnesia. During these episodes, the patient insisted to her daughter that she had the impression that she was living in a house very similar to her own but which was not her own. The onset of this symptom was accompanied by the development of a persistent anxiety, apparently reactive to the impact on the patient of the “inexplicable” experience of being in a different but identical house to her own. In the following days, the patient developed complex and structured visual hallucinations with preserved insight. Both the episodes of reduplicative paramnesia and visual hallucinations were repeated throughout the days. The hallucinations initially consisted of the vision of her parents sitting on the sofa in the dining room. The patient recognized that they were hallucinations since her parents had been deceased for years. Subsequently, she began to present hallucinations in the form of faceless, footless human figures appearing through the walls of the house and disappearing. There was no interaction with the hallucinations. The development of these complex symptoms in few days was associated with a frank exacerbation of anxiety. All of these prompted an urgent consultation with a psychiatrist.

The patient was seen in the psychiatric emergency room of a hospital. A CT scan was performed showing a chronic right lenticular infarction and signs of subtle cortico-subcortical atrophy. The case was classified as a possible incipient cognitive impairment of vascular etiology with associated anxiety and depressive symptoms, and the patient was discharged.

As the days passed, the family and the patient noted a frank worsening of the episodes of hallucinations and reduplicative paramnesia both in frequency and impact on the patient’s life. At the same time, the patient began to report clumsiness, especially in the left hemibody, and repeated trips and falls. Therefore, a second opinion was requested at our center.

Neuropsychological examination

In the anamnesis interview, the symptoms previously described were explored in detail, confirming the apparently rapid progressive course of all of them. It was also possible to confirm that the first symptom to appear was a reduplicative paramnesia. Table 1 summarizes the scores obtained in the neuropsychological examination.

Table 1. Neuropsychological assessment scores

MMSE = mini-mental state examination; ULE/URE = upper left/right extremity; nf = not finished; ↓ = performance below range of normality or in range of clinical relevance.

a Free and cued selective reminding test.

b Rey-Osterrieth complex figure test.

c Judgment of line orientation.

d Visual object and shape perception test.

Upon initial contact, the patient was slightly disoriented in time, but oriented in person and place, cooperative and fluent, with no signs of impaired comprehension or confusion. Slight dysarthria was evident in spontaneous speech. She obtained a MMSE score of 21/30 at the expense of failures in the items of temporal orientation, attention/calculation and recall.

The evaluation of episodic memory with the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test showed impairment of both short- and long-term free recall processes. The recall facilitated by semantic cues showed certain benefit that did not reach normality. The memory profile suggested an involvement on attention, access and retrieval, although the absence of a clear benefit mediated by semantic facilitation suggested a certain involvement of medial-temporal component. Immediate auditory-verbal span and working memory were within the normal range. Long-term visual memory, assessed with the recall of the Rey-Osterrieth complex figure (ROCFT), was profoundly impaired.

At the visuoconstructive and visuoperceptual level, the patient showed evident difficulties in organization and planning during ROCF copy (type IV copy). Type IV copy is characterized by the juxtaposition of details without an organized and planned strategy, even though the final result, in terms of similarity to the model, may be perfect. This is exactly what we observed in this patient’s performance.

Although the quality of the copy was good (33/36 points), the patient required approximately 4 min to complete the copy, placing the performance relative to the execution time in the 4th percentile. On a qualitative level, a clear compromise of the visual scanning and visual/spatial integration was evident during the ROCF copy. Intrusions of eye movements, especially of the left eye, were also noted. These intrusions were subsequently evidenced during neurological examination as saccadic intrusions. Spontaneous eye tracking and eye movements were intermittently interrupted by rapid intrusive movements, especially in the left eye, which tended to show interruptions of harmonic horizontal movement in the form of abrupt inward movements.

The recognition of superimposed figures and the ideational and ideomotor praxis were normal. In contrast, performance on the Benton’s Judgment of Line Orientation test and on the spatial localization subtest of the Visual and Object Space Perception Test were impaired, with performance at the 4th and 1st percentiles, respectively.

At the language level, the patient had a fluent spontaneous speech, without aphasic features but with dysarthria. Confrontational naming, reading, writing, repetition of words and pseudowords were preserved, with only some difficulties in the repetition of long and complex sentences.

Phonetic fluency (words beginning with the letter P) and semantic fluency (animals) were in the normal range. Parts A and B of the Trail Making Test (TMT) were profoundly impaired. A clear component of visual scanning deficit was again evident in the performance of part A of the test. The low performance in this test was mediated by the patient’s difficulties in looking for and finding numbers, obtaining a score in the 4th percentile. In part B of the TMT, in addition to the visual scanning difficulties, there were problems in cognitive flexibility associated with multiple perseverative errors. She was unable to finish the task and we decided to stop timing once the time spent was found to be in the range of alteration according to the normative data.

The neuropsychiatric assessment was conducted using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory and a semi-structured interview performed to the patient and caregiver. As reported, the first episode consisted in reduplicative paramnesia within her home. The patient explained that she had the profound impression of living in a house identical to her own, with the same furniture, the same rooms and the same arrangement of objects, but that it was certainly not her house. She could not explain either how she had come to this house or why she had been taken there. She knew it wasn’t her home because she felt it wasn’t her home and she was afraid that someone was trying to do something bad to her. At the time of the examination, there were also multiple episodes of complex visual hallucinations with her deceased parents and ghostly characters crossing the walls of the house. All of these were associated with a very important generalized anxiety, partially mediated by the impact of the experience of these “phenomena” but also occurring without clear triggers. Less significantly, but also evident to the caregiver, she was much more irritable.

Overall, both the neuropsychiatric symptoms reported in the form of reduplicative paramnesia and visual hallucinations, as well as the neuropsychological profile, delineated an eminently posterior-cortical syndrome suggestive of lateral parietal, occipital and parahippocampal gyrus involvement, although signs of fronto-temporal and cerebellar involvement were also evident. Taking into account the course and evolution reported by the patient and her family, the case was oriented as a rapidly progressive process under study.

Neurological examination

One week after the neuropsychological visit, the neurological evaluation was performed. During this visit, the family provided an MRI study performed 1 month before where only slight signs of cortico-subcortical atrophy were reported.

At the time of the examination, the patient presented a clearly unstable gait, impossibility for the tandem maneuver and evident coordination problems in the lower extremities. There was also a decomposition of the finger-nose test. No oculomotor limitations were observed, but there were occasional spasms with forced intrusions and elevation of both eyes. Campimetry was normal, there were no signs of parkinsonism, muscle stretch reflexes and sensibility were normal. Throughout the examination, polymyoclonus were observed in the hands.

Based on the set of findings described, the case was oriented at the syndromic level as a predominantly posterior-cortical rapidly progressive cognitive impairment with an associated cerebellar syndrome. Thus, at an etiological level we considered a paraneoplastic process versus a prion-mediated neurodegenerative disease, and admission to a hospital was scheduled for study.

Final diagnosis

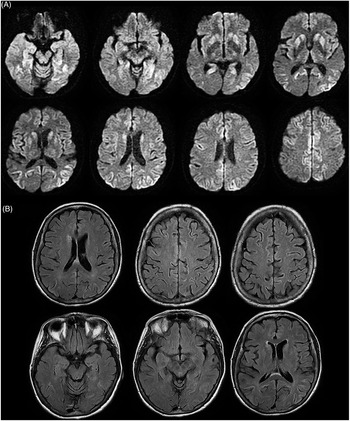

During admission, a new MRI study was requested. DWI sequences (Figure 1) showed hyperintensities in the caudate and putamen and multiple cortico-subcortical foci of hyperintensity, highlighting cortical ribbons prominently and bilaterally affecting the parahippocampal gyrus, inferior temporal, lingual and middle temporal gyrus, posterior cingulate, insula, middle occipital areas, medial frontals and lateral parietal. At time of CSF analysis, the 14-3-3 protein was negative in the determination of the protein by ELISA. The samples were sent to the reference center for possible analysis by Rt-Quick but finally the study was rejected, considering the neuroradiological and clinical findings to be sufficient. Genetic study was performed but no known mutation was detected. EEG study was normal at time of acquisition. The neuroimaging findings, the clinical symptoms and the pattern of disease progression was highly suggestive of a Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. In this sense, based on the characteristics at disease onset in the form of complex visual symptoms, the predominantly posterior-cortical neuropsychological profile, and the pattern of brain hyperintensities in posterior regions, a diagnosis of Heidenhain variant of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease was made.

Figure 1. (a) Axial sections of DWI showing hyperintensities in the basal ganglia and several cordial regions. First upper left sections show several foci of hyperintensity in the parahippocampal gyrus and occipital regions. (b) Axial sections of FLAIR sequence.

Discussion

The Heidenhain variant of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob (sCJD) disease is an unusual form of presentation sCJD which is prominently characterized, at disease onset, by visual disturbances in co-occurrence of posterior-cortical (mostly occipital) prion-related brain changes (Baiardi et al., Reference Baiardi, Capellari, Ladogana, Strumia, Santangelo, Pocchiari and Parchi2016; Feng et al., Reference Feng, Zhao, Zhou, Ye, Yu, Jiang and Zhou2021). The Heidenhain variant of sCJD is considered as one of the most atypical clinical presentations of CJD. The pattern of visual symptoms that can accompany the presentation of the disease includes disturbances at level of vision, perception, as well as hallucinations (Baiardi et al., Reference Baiardi, Capellari, Ladogana, Strumia, Santangelo, Pocchiari and Parchi2016).

Due to the infrequency of this form of presentation of sCJD, there are few cases reported in the literature. In one of the most exhaustive reviews carried out on this variant, a series of 18 cases were reported (Baiardi et al., Reference Baiardi, Capellari, Ladogana, Strumia, Santangelo, Pocchiari and Parchi2016). There, the most frequent symptoms were of a visual nature. Among them, blurred vision, visual field restrictions, disturbed color perception, distortion of object perception, some forms of visual agnosia and visual hallucinations stand out as the most frequent. In none of the cases reported in this review or in the literature, reduplicative paramnesia phenomena is described as the first symptom or as a symptom related to the Heidenhain variant of sCJD. It should be noted, however, that there are some reports of atypical forms of sCJD presentation in the form of extraordinarily florid psychotic episodes (Javed et al., Reference Javed, Alam, Krishna and Jaganathan2010; Nagashima et al., Reference Nagashima, Okawa, Kitamoto, Takahashi, Ishihara, Ozaki and Nagashima1999). That is why, given the peculiarity of this form of presentation, we considered it interesting to report the case.

Reduplicative paramnesia can be conceptualized into the misidentification syndromes, but unlike entities such as Capgras or Fregoli delirium – that are frequent in psychiatric disorders – reduplicative paramnesia usually has a neurological origin (Politis & Loane, Reference Politis and Loane2012). The core feature of reduplicative paramnesia is the belief or subjective perception that a place has been duplicated (i.e., the patient’s own home). In the case of “place reduplication,” patients usually report the impression of being in a place similar to their home, which is clearly not their home but a duplication. Generally, they do not know how to explain how they have arrived at this duplicated house, or why it exists, but they are convinced that it is so. Sometimes they refer to subtleties in the position of furniture or rooms that reinforce their conviction.

From the point of view of the processes and brain systems involved, reduplicative paramnesia cannot be solely conceptualized as a visuoperceptive disorder. This symptom includes features of visuospatial and visuoperceptive deficits, as well as disturbed integration of semantic knowledge about the peripersonal space. Accordingly, lesions involving the ventral visual stream, and interfering the communication between the visual cortex and visual processing areas of the inferior temporal lobe, and visual memory of the parahippocampal gyrus, seems to strongly contribute to the development of reduplicative paramnesia (Budson et al., Reference Budson, Roth, Rentz and Ronthal2000; Sellal et al., Reference Sellal, Fontaine, van der Linden, Rainville and Labrecque1996). In the case we report, neuroimaging findings were prominently found in posterior-cortical regions involving all of these territories. Moreover, neuropsychological and neuropsychiatric deficits were also of clear posterior-cortical characteristics. At the time of MR imaging, the findings were evident in several cortical and subcortical territories, but a significant lesional burden was evident bilaterally, at the parahippocampal, fusiform, lingual, calcarine and occipital levels, with also evident lesions at the level of the orbital prefrontal cortex, thalamus and basal ganglia. Although few studies have been able to explore the pathophysiology of reduplicative paramnesia (Alves et al., Reference Alves, Fonseca, Silva, Andrade, Pinho, Thiebaut de Schotten and Martins2021; Hakim et al., Reference Hakim, Verma and Greiffenstein1988), in many of the cases studied, a clear discrepancy between performance in different types of processes was observed. In most of the cases, and in ours, visuospatial and frontal processes were compromised but naming and verbal memory were relatively preserved (Hakim et al., Reference Hakim, Verma and Greiffenstein1988). At the imaging level, although reduplicative paramnesia of place has been described in patients with right and left lesions, findings related to the involvement of the right hemisphere predominate (Alves et al., Reference Alves, Fonseca, Silva, Andrade, Pinho, Thiebaut de Schotten and Martins2021; Budson et al., Reference Budson, Roth, Rentz and Ronthal2000). Particularly remarkable are the imaging findings suggestive of involvement at the level of fronto-thalamic and occipito-temporal connections whose dysfunction would contribute to reduplicative paramnesia through the participation of a whole series of dysfunctional processes (Alves et al., Reference Alves, Fonseca, Silva, Andrade, Pinho, Thiebaut de Schotten and Martins2021). On the one hand, defects at the fronto-thalamic level would contribute to: (a) alterations of multimodal integration, where the recognition of space would remain intact but not the judgment of one’s position or place with respect to this space (Alves et al., Reference Alves, Foulon, Karolis, Bzdok, Margulies, Volle and Thiebaut de Schotten2019); and (b) to defects in the processing of incongruence and reality monitoring that would condition context update (Simons et al., Reference Simons, Garrison and Johnson2017). On the other hand, the disruption of temporo-occipital regions of the ventral visual stream could contribute to the defects at the level of the allocentric spatial representations seen in patients with reduplicative paramnesia of place (Benson et al., Reference Benson, Gardner and Meadows1976). That is, patients, as in our case, are not able to locate themselves in the space or environment they occupy, although egocentric processing remains intact, as they are able to describe the routes between different places, including the one they are misidentifying. In any case, the mechanisms involved in the genesis of the phenomena of reduplicative paramnesia of place remain partially understood and deserve to be studied in depth.

Overall, we report an atypical form of presentation of an atypical condition, such as is a reduplicative paramnesia as the first clinical feature of a Heidenhain Variant of sCJD. According to this report, reduplicative paramnesia can be included as one of the possible clinical features accompanying the Heidenhain Variant of sCJD.

Acknowledgements

None.

Author contributions

SMH: Writing, data analysis, clinical follow up, review CNM: Writing, data analysis, clinical follow up, review SCG: Writing, data analysis, clinical follow up, review IAB: Writing, review. JK: Writing, linical follow up, review.

Funding statement

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.