INTRODUCTION

Archaeologies of interment were first undertaken in relation to American Civil War sites and artefacts,Footnote 1 with Boer WarFootnote 2 and European Second World War campsFootnote 3 subsequent research areas. The field has rapidly expanded to include consideration of the first modern purpose-built camps during the Napoleonic warsFootnote 4 through to Franco’s camps in Spain (1936–52),Footnote 5 and even Camp Delta, Guantanamo Bay, in use since 2002.Footnote 6 Several edited volumes have brought together international archaeological approaches, often combining these with anthropological, historical and art-historical perspectives on both military and civilian internment.Footnote 7 These publications have concentrated on resistance or on retention of cultural traits of the home culture while held in a foreign land, and most use either site evidence (survey or excavation) or craft artefacts from collections. Here, the two strands are drawn together in an integrated approach for the first time for a First World War military camp.

Studies of Second World War prisoner of war experiences dominate the archaeological literature, in part because personal testimony has been available to augment the material remains; nevertheless, a literature is developing on First World War internment.Footnote 8 It was the British treatment of internees during the Boer War that drew attention to the need to plan appropriate infrastructure in camps to prevent disease, but during the First World War the psychological impact of confinement – termed ‘barbed wire disease’ – also became apparent.Footnote 9 This study examines the archaeological evidence at Les Blanches Banques camp, Jersey, and the artefacts made there to explore the activity of placemaking, an approach developing out of one author’s consideration of prisoner of war coping strategiesFootnote 10 and another’s examination of internees’ nested experienced and imagined spaces.Footnote 11

Placemaking is a process by which individuals and groups construct a meaningful location, and this can combine both physical modification and the creation of meanings and memories through both daily routines and exceptional events that give that place a significance. A recent cross-disciplinary review of relevant literature has identified several key themes within placemaking that are drawn out in this historical archaeology study.Footnote 12 One theme is variation along a continuum, strongly present in the dynamic at Les Blanches Banques. The process of placemaking is framed and partially constructed by the top-down British military command, but is also created by an individual or group through the bottom-up group and individual behaviour of the prisoners and guards. Another theme is here central to this interpretation: the process of placemaking creates an attachment or connection between the community member and the place in which they live, work and play.Footnote 13 At Les Blanches Banques, both the prisoners and the guards were members of different communities but joined within the military imperative of wartime prisoner management. Another theme in the literature is that an individual’s sense of place can be either positive or negative,Footnote 14 here linked to the camp experience shared by all, which involved separation from family and civilian friends. However, camaraderie within the organised camp units and accommodation, and some opportunities for skills and pastimes perhaps unavailable in normal circumstances, provided some positive associations with place.

Placemaking in archaeology has been largely confined to prehistoric periods and often with reference to ritual in the landscape,Footnote 15 or in historical archaeology within contexts of resistance or defiance.Footnote 16 However, meaningful places are also created through repeated daily social activities and relationships, especially when these are vital for maintaining resilience under conditions such as internment.Footnote 17 Placemaking can be at an individual level – that may be revealed through a craft product – but is often combined at a social level of shared experiences and meanings and revealed through communally-used spaces. In the pressure-cooker environment of the overcrowded internment camp with limited privacy, individual imagination was balanced with intimately shared living and practice.

It must be remembered that, unlike criminal prisoners, the inmates had no knowledge of how long they might be held, nor how the world into which they may eventually be released might react to them. They had to manage survivor guilt, safe in captivity, while comrades had to continue to fight and risk their lives for their country, and endure long periods away from home.Footnote 18 They resided in a liminal location physically and socially, and so creating meaningful places was a form of agency in their restricted world. Recent studies of coping reveal how individual personalities and past experiences affect responses to incarceration;Footnote 19 this multidisciplinary study of Les Blanches Banques reveals how several placemaking mechanisms were employed by at least some of the prisoners, though their effectiveness in coping with the stresses of communal imprisonment remains unknown.

LOCATION AND CONTEXT

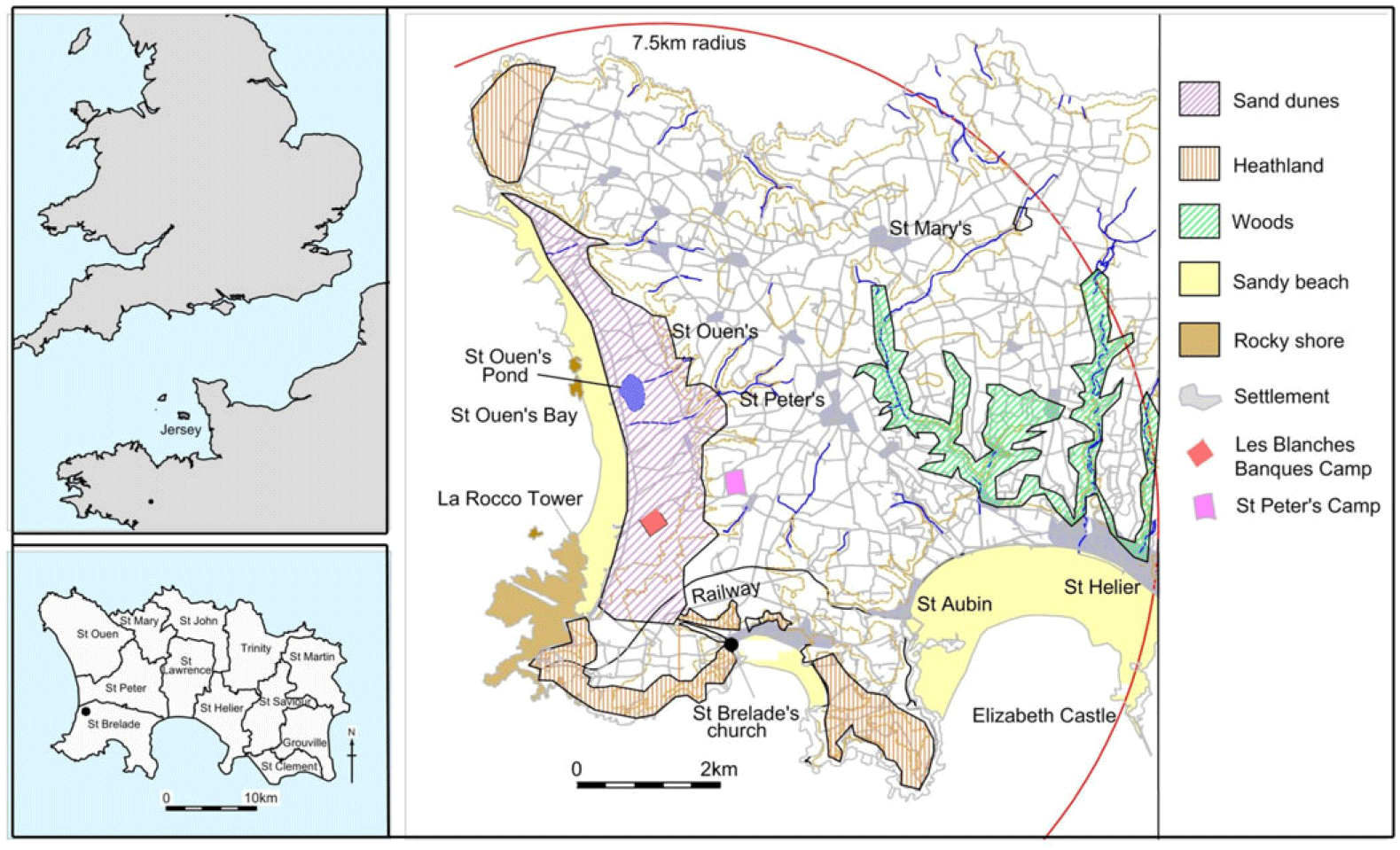

Les Blanches Banques lies in the south-eastern part of Jersey, within the parish of St Brelade. It is set slightly back from the shoreline of St Ouen’s Bay to the east of Chemin des Basses Mielles, which leads down to the coastal road and Le Braye slipway. It is overlooked by higher ground to the east and south and has views out to sea and along the coast to two notable landmarks: La Rocco Tower, completed in 1801 but a ruin in the early twentieth century, and the functioning nineteenth-century concrete La Corbière lighthouse. The nearest settlement to the camp lay up the scarp to the north, but the sand dunes that covered the area offered little potential for agriculture, so the area was largely deserted. The mapping of field boundaries and settlement (fig 1) emphasises the intensity of agriculture on the island, and that the sand dunes were the largest unexploited area available. It was also close to the military St Peter’s Camp on the higher land to the east, meaning that additional armed forces could be quickly summoned should there be any need.

Fig 1. Location map for Les Blanches Banques camp. Potential area available for organised walks for the prisoners indicated by the 7.5km arc; St Brelade’s church, where prisoner burials took place, is marked. Diagram: R Philpott.

Les Blanches Banques is today a sand dune area that is open for public access, protected for its ecological importance and listed as a Natural Site of Special Interest under Jersey legislation since 1996.Footnote 20 The site also has several upstanding prehistoric sites, notably a Chalcolithic ossuary cist and three standing stones, all investigated in the 1920s and surviving because of being buried within the dunes.Footnote 21 Neolithic artefacts were also recovered during the construction of some of the camp infrastructure.Footnote 22 The twentieth-century archaeology of the area is partly visible, and this is noted on an interpretation panel in the car park that lies between the camp and the road. A recent local history volume has drawn attention to the site,Footnote 23 but academic research has been limited.

History and archaeology of First World War internment

The First World War was the first conflict that led to the capture of large numbers of enemy combatants that required a coherent management at many different locations, greatly expanding on what had been provided for the Napoleonic and Boer wars.Footnote 24 When numbers were small, these could be held in empty army camps in Britain, but once these facilities were required for training the increasing numbers of British troops, and as prisoner numbers escalated, dedicated prisoner of war camps were established across the British Isles. By the end of 1915, a total of twenty-five camps were in operation across the UK, including Les Blanches Banques, though by late 1917 there were 165 camps when there were over 150,000 prisoners in Britain.Footnote 25 This number continued to increase during the last months of the war.Footnote 26 In addition, more than 30,000 male enemy alien civilians were also interned during the First World War, initially in prisons and makeshift accommodation across the country but then organised into a small number of camps. Some of these have recently received some archaeological attention, notably at Stobs Camp in Scotland;Footnote 27 this was redesignated as a military prisoner of war camp as the civilian internees there and elsewhere were transferred to camps on the Isle of Man, and these have also received a small amount of archaeological attention.Footnote 28

From 1916, many ordinary ranks prisoners across Britain worked outside the camps on construction, forestry, quarrying and agriculture. Les Blanches Banques prisoners of war were rarely employed out of the camp even though the island relied on labour-intensive agriculture, and the camp management attempted to make such arrangements and legally they could be used in this way.Footnote 29 Most prisoners were sent to England to work on the land in February 1917; the remaining 300 were used to load potatoes onto steamers for export but were then removed in August 1917, leaving the camp deserted. However, by September 1917 Austro-Hungarian military prisoners were being used on Jersey farms, and housed in civilian accommodation, though there were risks that the prisoners could fraternise with the local women both at the pier and on farms.Footnote 30 With large numbers of prisoners being captured during the last year of the war, the camp reopened in April 1918 and gradually 1,000 officers were housed there,Footnote 31 placed in Jersey because they could not be compelled to work and there was little demand for prisoner of war labour on the island, unlike in England. However, the increased call up of local labourers meant that even these prisoners were allowed to leave for paid work by June 1918, if they chose.Footnote 32 Their placemaking in their work contexts lies outside the scope of this paper, but was no doubt important to those individuals.

Despite its proximity to France, the Channel Islands only ever housed the one prisoner of war camp during the First Word War. The degree of regional variability in distribution of camps has been demonstrated by the recent Cadw-sponsored surveys, which have thus far identified fifty-five prisoner of war camps across Wales, only eight of which have been noted in south-east Wales, partly because camps close to the border of England provided labour in adjacent parts of Wales.Footnote 33 Of the thirteen prisoner of war camps in Gwynedd, that at Frongoch is notable because it was used to hold, at different times, both Irish Republican prisoners and German prisoners, and has recently attracted archaeological investigation.Footnote 34 Frongoch also acted as one of the major camps from which German prisoners were sent out to smaller work camps, even as far as south-west Wales, which had only eight main camps.Footnote 35 Clwyd, in contrast, contained far more camps, with twenty-six examples.Footnote 36 A recent survey of army camps for England sadly did not include prisoner of war sites.Footnote 37

The first detailed survey of the extant remains at Les Blanches Banques suggests that, because standing structures and associated concrete surfaces survive, it is one of the best preserved First World War camps in the British Isles. This level of survival is because of the protection of the sand dunes and the limited reuse of the landscape. Stobs camp has the advantage of some surviving in situ buildings, but has been disturbed by subsequent reuse, and Brocton Camp contains some well-preserved foundations, but many elements have been damaged.Footnote 38 Les Blanches Banques can therefore throw light on aspects of First World War experience that has hitherto received limited archaeological attention.

PROJECT METHODOLOGY

Contemporary historical sources for Les Blanches Banques are not as plentiful as those from some other camps,Footnote 39 but a few newspaper reports and a Parliamentary paper are informative.Footnote 40 The article in the Bulletin of the Société Jersiaise by Major Naish, who designed the camp and was present throughout its occupation, is invaluable in assisting with the interpretation of the small number of contemporary images of the camp and the extensive archaeological remains identified during the survey, but does not reflect on the life experiences of either guards or prisoners.Footnote 41 A small number of official photographs survive, some taken during the construction of the camp, but also including a vertical aerial photograph of 1933 that reveals areas of the camp which have since been buried by the shifting sand dunes.Footnote 42 A small number of other photographs of prisoners or the camp are in private possession and some are visible online.Footnote 43

The survey undertaken combined mapping of architectural and topographic features and magnetometry to identify some of the structures and infrastructure such as underground ceramic sewage pipes.Footnote 44 It had been thought that the masking effects of the dunes would have made the application of LiDAR, so effective for both military and prisoner of war camps on Cannock Chase,Footnote 45 inappropriate here, but a LiDAR survey of Jersey has recently become available (fig 2) and many elements of the camp appear clearly.

Fig 2. LiDAR image of the Les Blanches Banques camp, released 2023. This shows more clearly than any other source the rectangular enclosure round the hospital complex in the south-western corner of the camp. Image: courtesy of Jersey Heritage HER.

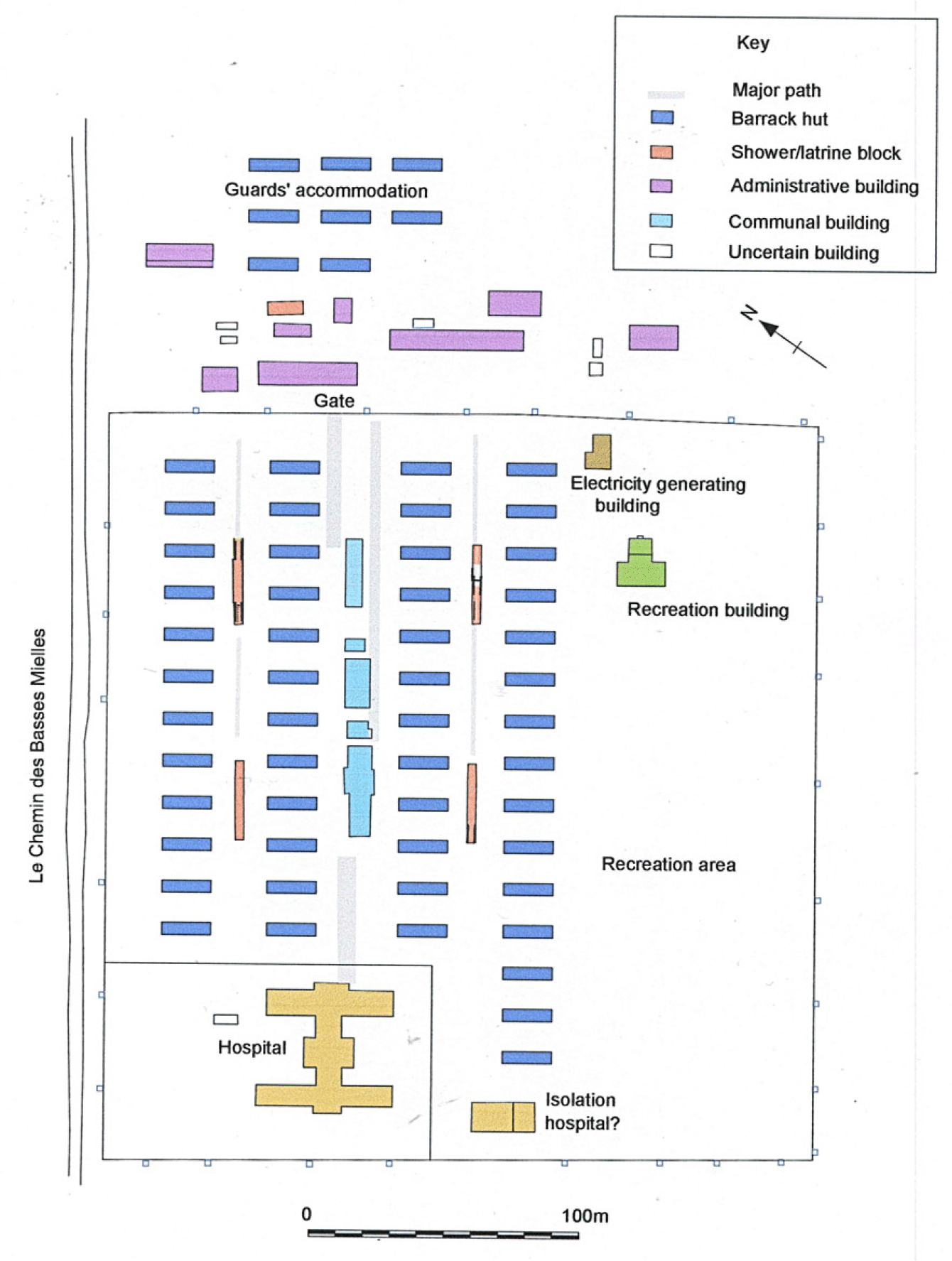

The survey data combined with the photographic and painted images have enabled a full plan to be proposed and confirmed by LiDAR. By combining multiple sources it is possible to define the small world in which the prisoners lived most of the time and over which the guards observed (fig 3). A descriptive account of the camp plan and the surviving structures based on the survey has been published.Footnote 46 The layout and barbed wire boundaries of the camp created a set of internal and external spaces within which placemaking could take place through daily routines and shared experiences and activities.

Fig 3. Interpretive plan of the Les Blanches Banques camp based on information from surface survey, aerial photographs, LiDAR and contemporary drawings and photographs. Diagram: R Philpott.

The American Embassy visit on 20 April 1916 on behalf of the International Committee of the Red Cross provides the only contemporary contextual documentation for the camp buildings in use and the social structures within the camp. This account also provides some detail about camp activities, though it makes no mention of the creation of craft items such as those which survive.Footnote 47 However, objects in the possession of collectors and museums in Jersey show us the extent of prisoner craftwork, though the relatively limited range of subject matter may reflect patterns of retention rather than original production. The role of creativity behind barbed wire as a way of copying physically and psychologically has now been well-established,Footnote 48 and also reflected the prisoners’ placemaking. Many items without the camp name or a view of the camp, including interior view photographs of barracks and theatrical performances and exterior views with a backdrop of just a barrack building, are so similar to those known from many other camps that identifying their place of production is impossible unless they are annotated or have a known history, but a few such images have been identified.

All identified craft products have been recorded by photography, but detailed measurement and analysis of the objects has not yet proved possible as they were only made briefly available on site by their private owners, and more items may yet come to light. The craftwork surviving from the camp is limited, and probably represents a surviving range of items once made for the camp guards and administrators for barter or in exchange for money as these have remained in Jersey and some have recorded provenance; only a few of the items seem to have been made for use by the prisoners themselves, or for sending to their families, though such items may exist in private hands in Germany. These items need to be considered, therefore, not only in terms of their meaning to the prisoner of war artists but also those for whom they were commissioned. Unlike creative categories known from elsewhere, such as camp newspapers that were created for internees by internees, or some artworks for display within the barracks or to be sent to relatives, these commissioned items were created for a clientele who had their own, relatively privileged, experience of the camp. They had a certain gaze, reinforced by these representations as part of the customers’ placemaking. The craft products linked to placemaking comprise examples of the folk art ‘ship in a bottle’ tradition, landscape scenes painted or created through marquetry and other items that speak of place and would have acted as souvenirs of the camp.

TOP-DOWN AND BOTTOM-UP PLACEMAKING

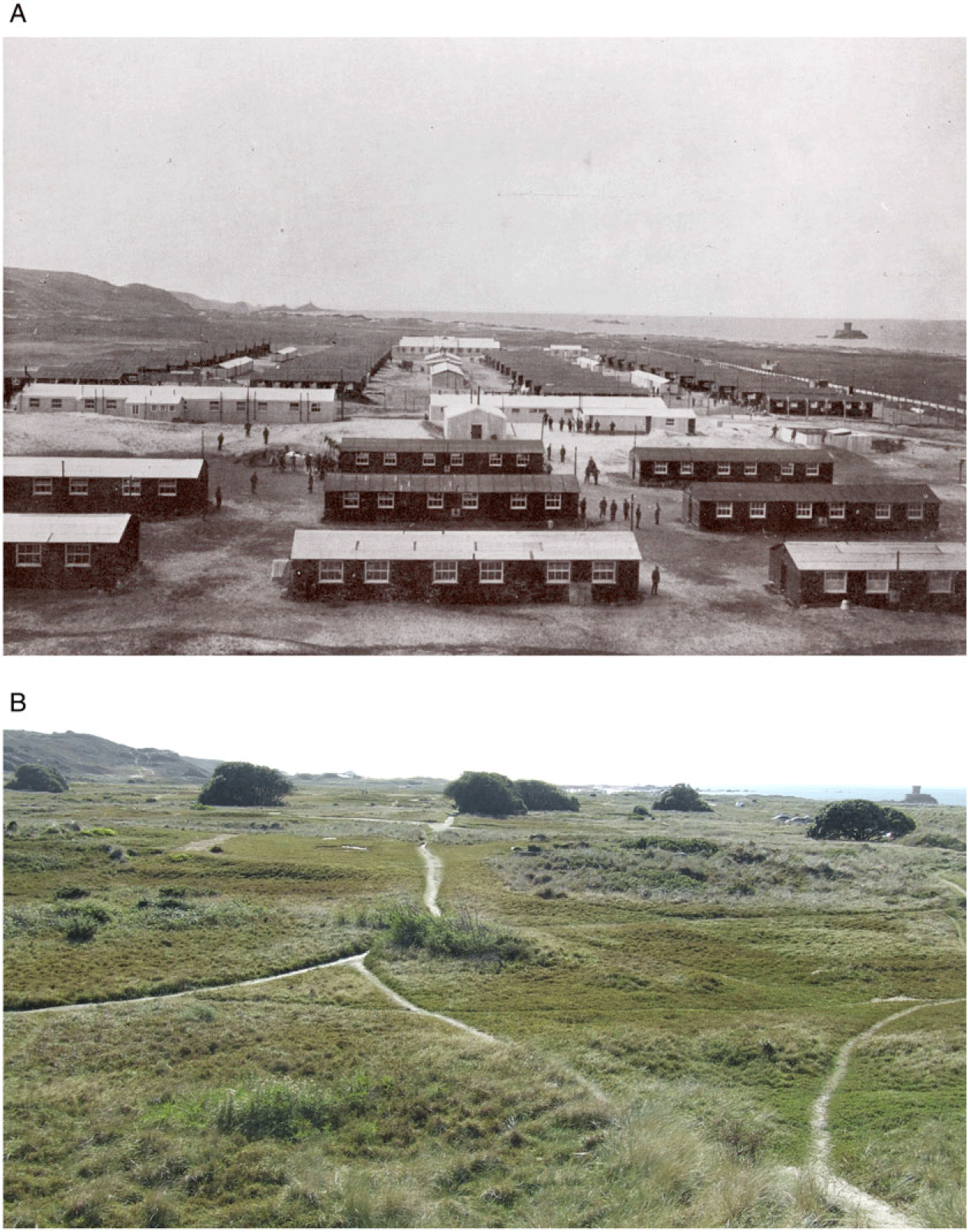

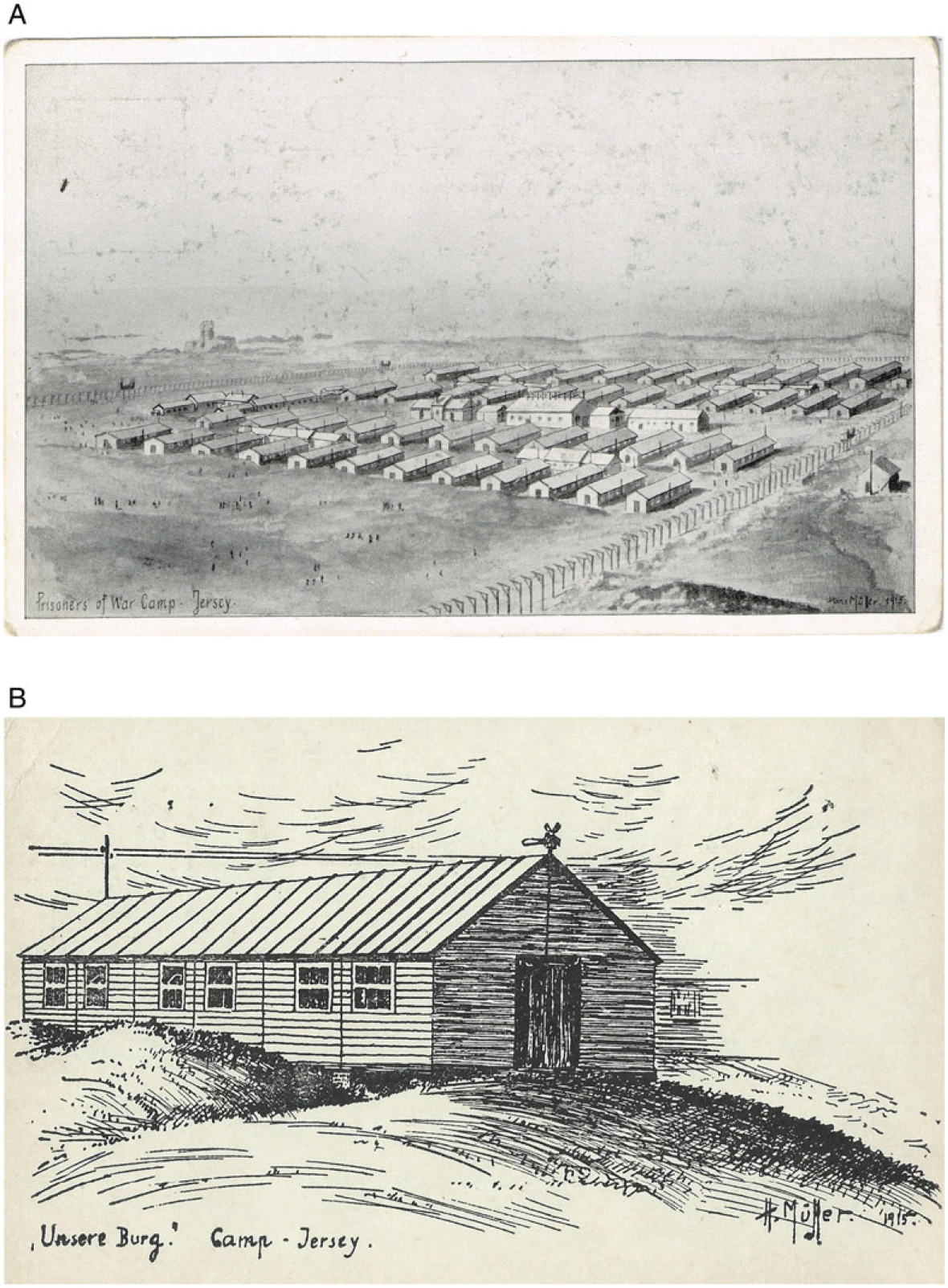

During the First World War, the British specially-built prisoner of war camps were based on the design of army camps, albeit adjusted to local circumstances. These used contemporary military building designs including tents and wooden and metal buildings – usually prefabricated – that were designed for military purposes.Footnote 49 Surviving photographs and artwork showing the camp all emphasise the constrained space, the symmetrical layout of barracks and support buildings, and a uniformity that gives the impression of depersonalisation. These are most obvious in the 1915 photographs of the recently completed camp where the architecture and planning visually dominate over the evidence of human lived experience, as they portray the structural coherence of the camp as a settlement (fig 4A).

Fig 4. Views of the site of the camp from the north east A: the completed camp 2015; B: view in 2017. Photographs: H Mytum.

The military authorities created and maintained the camp within a challenging landscape while maintaining security in a location so close to the sea. There was pressure on the British government to manage prisoner of war camps according to the 1906 Geneva Convention and a resolution passed at the International Conference in 1912.Footnote 50 The captives had to be kept physically and emotionally safe, unlike British practice during the Boer Wars when there was extensive criticism of the treatment of both civilian and military prisoners in South African camps, with epidemic deaths of 26,000 white women and children,Footnote 51 and probably large numbers of black civilians also dying. These experiences framed the British planning of prisoner of war camps during the First World War, creating well-organised and sanitary accommodation with an emphasis on function that formed the environment within which prisoners and guards lived.Footnote 52

The difficulties of establishing the camp are confirmed by the survey of the sand dune landscape setting, and considering how this was manipulated and used from the field evidence combined with historic vertical aerial photographs and the account by Major T E Naish, who commanded the Royal Engineers in Jersey from September 1914 until December 1919. He only published his experiences in 1955, but they are extremely detailed and are dated April 1920.Footnote 53 Most of Jersey was intensively farmed at this time, but the sand dunes of Les Blanches Banques (still present today, fig 4B) were already owned by the War Department for practice manoeuvres and were already framed as a place with a military association. The camp both attracted inquisitive locals wishing to view the enemy and interrupted movement along Le Chemin des Basses Mielles during construction, to the consternation of the civilian authorities.Footnote 54 Building the camp– a contribution by Jersey to the war effort in housing prisoners who reflected British military success, but also housing the exotic – was placemaking the foreign onetime combatants whose uniforms and language emphasised their difference, and so it gained a new significance to the Jersey population.

The plan of the camp (fig 3) was based on that of a British infantry battalion for 1,000 men,Footnote 55 and comprised numerous standard prefabricated buildings ordered by the War Office from contractors in England and assembled by local firms. These structures were comparable to those on many military installations; that the users were prisoners did not affect their suitability, and others were indeed occupied by the guards.Footnote 56 Elements of the buildings had to be built on site, notably the concrete hard-standings for communal buildings, brick piers on which the wooden barracks would stand, the lower portions of latrine blocks and concrete posthole fills for the boundary fence, all of which are archaeologically visible (fig 5). These were all erected by local Jersey contractors, but they were then inhabited by prisoners and guards who lived, worked, relaxed and moved around this particular landscape for a length of time far greater than troops, who would be frequently moved to new postings.

Fig 5. Surviving components of the camp. A: barrack block piers; B: latrine block. Photographs: A: Société Jersiaise, B: H Mytum.

The camp was initially designed for 1,000 non-officer prisoners, and the compound was erected to enclose an area for this number. In July 1915, however, the camp received a further 500 prisoners, so three new barracks were constructed and some of the dining halls were converted to sleeping accommodation, with the remainder now managing all meals through double sittings; the size of the camp was not increased.Footnote 57

All this infrastructure created a new settlement that was effective in terms of sanitation, security, sleeping and catering arrangements and was a form of military, top-down placemaking. The adjacent guards’ complex, outside the camp but slightly elevated to enhance surveillance, combined with the presence of observation towers round the perimeter, meant that the prisoners lived under constant military observation when outside, and in overcrowded conditions with no privacy inside. Study of the various sources reveal, however, that the barracks were homes, not just billets. The built environment created patterns of movement and habitation that would, through repetition, create a daily routine structured in space and time where variations and nature of interactions would gain greater meaning, and what might appear mundane locations would be imbued with placemaking significance. This shift reworked that camp from the planners’ view of placemaking to that formed by the creative participant placemaking process.Footnote 58

The water supply enabled the provision of latrines and washing facilities in four blocks, each with about a dozen barrack blocks each for thirty men (fig 2). These are among the best preserved structures, with the external walls upstanding. These are to a standard military design, with a portion for urinals and toilet cubicles at each end and a central section (the ablution shed) for washing.Footnote 59 The provision of showers seems to have been limited, but some were located in the south-eastern part of the prisoner of war camp and others were surveyed in the guards’ area (fig 3).

The movement between barracks and latrine blocks created frequently experienced but extremely limited routes, and, once the mess halls were taken over for accommodation, most prisoners’ time inside was spent in and between these two types of structures (fig 3). Unlike many camps, the sand subsoil meant that these heavily used thoroughfares, constructed and maintained by the prisoners,Footnote 60 remained dry in all weathers but provided little visual stimulation (fig 6). The exterior space, notably the exercise area, thus became an even more important component of prisoner experience, enhanced by the vistas of seascape and landscape visible through the barbed wire. Although overlooked on three sides by guards on raised platforms or watchtowers around the perimeter (figs 6 and 7), it allowed the playing of various games including football, a form of rounders and what Naish describes as ‘a form of tennis or badminton played with a football’,Footnote 61 which may have been some form of volleyball or handball. The prisoners also constructed a tennis court, and they used outside gymnastic equipment. The making and use of places of sport and fitness were placemaking activities that modified the camp to create bespoke, meaningful zones that prevented boredom and maintained health but also reinforced individual and group self-worth.

Fig 6. An enlargement of part of a view of the camp from the east that shows the roads between the buildings. Note the washing lines strung between the barracks. Photograph: Société Jersiaise.

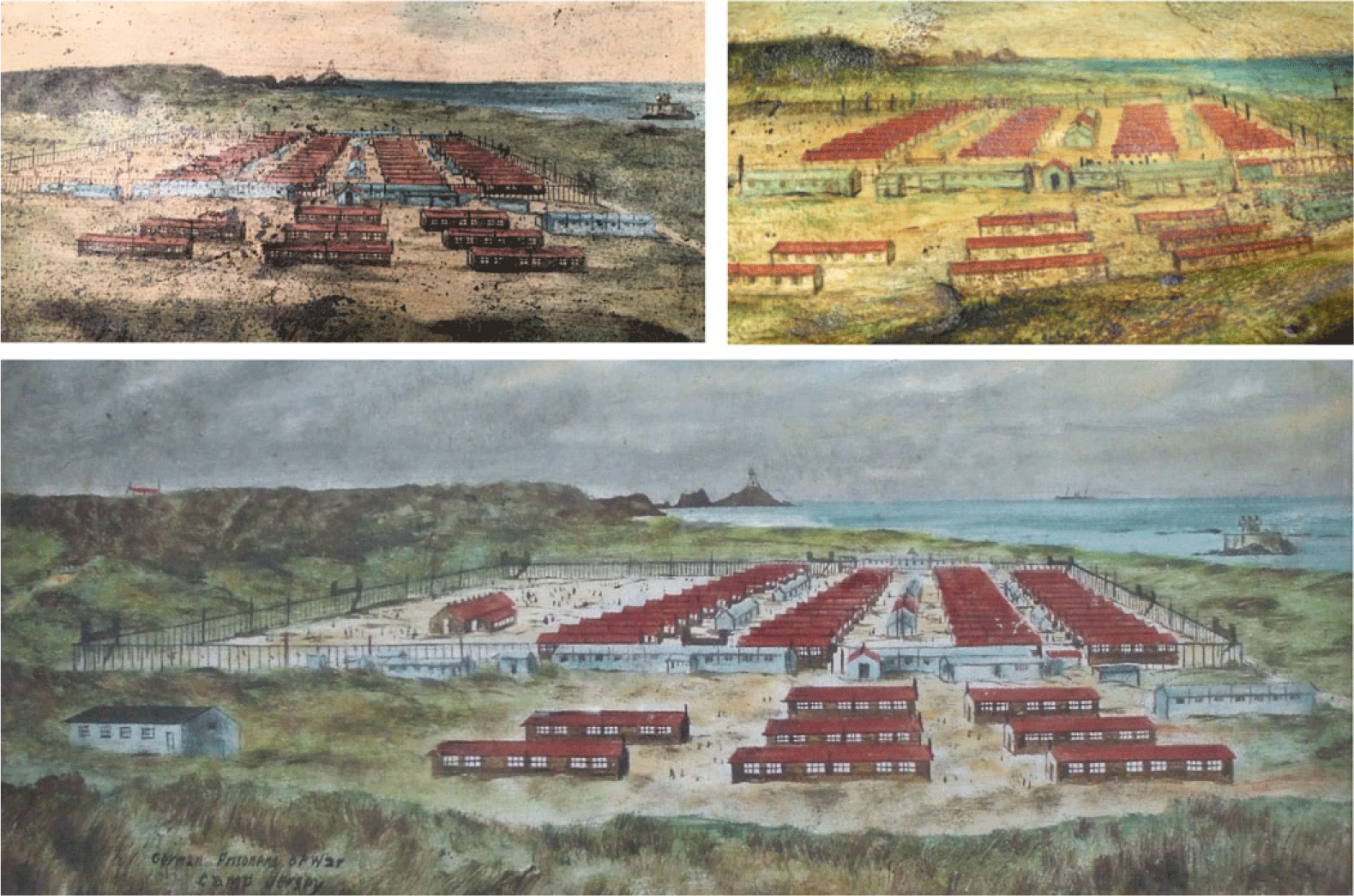

Fig 7. Images of the camp from the north east with the guards’ camp on the foreground. Photographs: G Carr, courtesy of Damien Horn.

The buildings provided well-ventilated barrack accommodation, with the brick piers providing airflow beneath as well as inhibiting the hiding of contraband and making the digging of escape tunnels more difficult, though often sand dunes built up against the piers and some of the images suggest that the ground was deliberately built up to close off the voids. These were the same design as those for British troops but, as the prisoners stayed in the same bunk for a long time, unlike the troops who moved on to other locations, the few internal images show that, as elsewhere, they were allowed to make the small amount of space their own with images and craft items.Footnote 62 These helped to create some personal space, as the continuous communal living could be one of the greatest causes of psychological problems.Footnote 63 The British authorities allowed as much latitude as possible and most management was by the prisoners themselves, so that they could maintain self-respect, care for one another, and be busy running the internal activities within the camp. The camp was where new friendships were forged, experiences shared, skills learnt and an alien place experienced and, as far as possible, recreated into a male form of domestic space.

These spaces were also transformed into meaningful places by prisoners working together for the performance of music and theatre,Footnote 64 creation of craftworkFootnote 65 and newspapers,Footnote 66 or physical activities such as gardening and sports.Footnote 67 Many of these activities invested meanings in places, not only for participants but also other prisoner or guard observers. As with many camps managed by the British, routines were carried out and managed by prisoners, from catering to running the library, to organising activities and events such as concerts and sporting competitions, to buildings and grounds maintenance. Some of these activities are represented in the Les Blanches Banques evidence, and are examined below, but only a sample of the likely placemaking activities can be confirmed. Moreover, others found elsewhere seem to be missing from Les Blanches Banques, most notably gardening,Footnote 68 which in camps elsewhere involved both allotments and flower beds around the barracks, often decorated with kerbing or small fences to create special places for social activities such as tea drinking.Footnote 69 Their omission may be due to the sand dune location, with the scale and frequency of wind-blow and undeveloped soils preventing the establishment of cultivated areas; indeed, many images show sand building up against the buildings, indicating a constantly changing topography.

Exercise and organised sport took place on the large area without buildings in the southern part of the camp, and is highly visible in all images of the camp. The initial military planning was found to be inadequate to support the range of activities desired, particularly as the dining halls were not available for recreation outside mealtimes when they were converted into barracks when the camp was expanded to house 1,500 prisoners instead of the planned 1,000. The army built a recreation building for the guards, and later the American YMCA provided materials for a prisoner recreation building. This was erected by the prisoners,Footnote 70 and the concrete base was located in the survey. Images show changes to the camp that were designed to move beyond the main survival elements, and to create meaningful places for social interaction. Many of the images show the early design of the camp (fig 7, top). An exception is a framed painting of the camp that shows a later stage of the camp’s development with the guards’ recreation building shown bottom left, and the prisoners’ YMCA recreation building erected by the prisoners themselves sits within their exercise area (fig 7, bottom).

PLACEMAKING CONNECTIONS BETWEEN PEOPLE AND PLACE

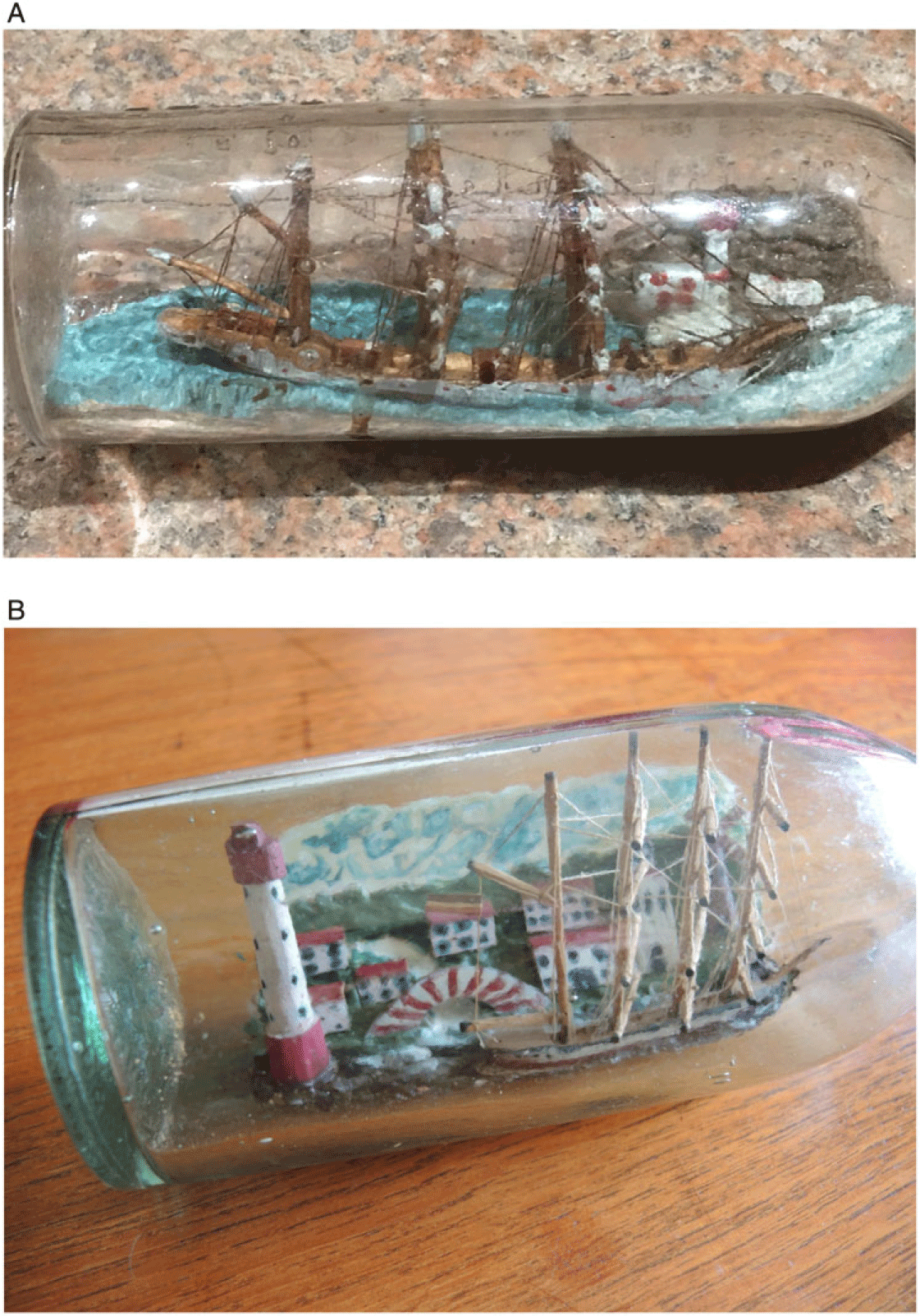

The numerous mariners among the early cohort of prisoners would have been familiar with the craft of making ships in bottles, often creating models of the ship on which they sailed. This was their world, their home, a place of significance that was made through not only work but companionship, shared hardships and dangers as well as a symbol of freedom to travel. Four ships in bottles made in the camp are known, and they were presumably made by the members of the substantial minority of prisoners who came from naval backgrounds (about a third of the original cohort). Their placemaking traditions would include their ship as a meaningful locale, and similar to the internment camp in that they would be in confined spaces occupied by the same limited group of people for a considerable period of time with no chance of escape. Confined to land yet within sight of the sea and passing shipping, the bottles with both coastline and ship reveal the mariner’s world perspective, but, interestingly, while cottages are depicted on some, there are no representations of the camp (fig 8A). Another bottle contains a German ship, the Else, sailing gently past a hillside with a scatter of red-roofed white buildings.Footnote 71 It dominates local waters, claiming the seascape for the Germans, but was given to one of the guards of the Royal Jersey Militia by a prisoner of war (fig 8B). Its detail reveals more about the maker’s placemaking than the guard’s, a relatively unusual perspective in the surviving craftwork from Les Blanches Banques.

Fig 8. Mariners’ placemaking. A: ship in a bottle with the coast in the background; B: German vessel Else with coastal scene. Photographs: G Carr, courtesy of Damien Horn (A) and Jersey Museum (B).

Most of the images of placemaking are from artefacts owned by Jersey families who curated gifts or purchases created by prisoners for guards. These indicate the customers’ placemaking strategies, creating memories to be perpetuated with their gaze. The images were created by the prisoners and no doubt reinforced their placemaking in terms of camp planning, architecture and broader landscape setting, but their literal perspective is one of an outsider (fig 7).

Almost invariably, the views of the camp are heavily focused – not to say, fixated – on its landscape setting and show either the camp itself, nestled in the sand dunes, or the view of the sea from the camp. This reflects the degree to which the world of the camp and the existence of those inside it had shrunk to this small geographical area at the bottom of St Ouen’s Bay, but also how the guards knew this wider landscape largely outside the captives’ experience. As there are these opposing views and experiences of landscape, the placemaking implications of their composition is discussed in the following section; here the focus is on the numerous landscape images that reveal strong identification with the land and seascape.

Two beach pebbles of a similar size are known, and both are clearly painted by different artists but of the same view. One, in Jersey Museum, has no story attached and is slightly worn although still colourful (fig 9);Footnote 72 the second is in private ownership and belongs to the son of a camp guard. This confirms the nature of at least some of these objects as souvenirs for guards, and the desire of the prisoners to earn money using the most basic of freely accessible raw materials. The beach pebbles would have been collected during the swimming visits to the beach or on the exercise marches, and they may have carried additional potency for the prisoners as they represented a link with outside the camp, and a remembrance of trips beyond the barbed wire. Here perhaps placemaking of both guards and prisoners is combined.

Fig 9. Beach pebble, 12.0cm × 18.9cm, with a painted scene of the camp from the north east. Photograph: H Mytum with permission of Jersey Museum.

A similar viewpoint for the camp is represented on an ox scapula in private ownership (fig 10A). The reverse reveals a feature present in a number of items of prisoner art at Les Blanches Banques, that of naming the site. The surface (fig 10B) is painted brown and varnished so that it resembles wood, and shows a cream-coloured ribbon banner with the words ‘Prisoners of War Camp Jersey 1914 15 16’. This prominent naming of the camp is part of the placemaking process, identifying with the camp and indeed the length of the war, though the prisoner could only have been a resident from 1915. This phrasing of the camp name is found on a number of items in a range of materials,Footnote 73 but the local place name Les Blanches Banques is not used. The prisoners define their own temporary place-made camp in this naming, seen as on Jersey not a more specific location, a foreign enclave on the island, also emphasised when German is added to the title

Fig 10. Ox scapula painted at the camp. A: view of the camp from the north east; B: reverse showing text on a banner. Photographs: G Carr, courtesy of Damien Horn.

The association with the island of Jersey and prisoners’ placemaking within the island setting is demonstrated in several artefacts. A marquetry wooden box with a painted central scene shows the view from the south of La Rocco Tower, a Napoleonic off-shore fort that can be seen clearly from the site of the camp but from a completely different angle (fig 11A). A sketch on which to base this design might have been made on one of the exercise marches, or even on the return walk from a burial at St Brelade churchyard. It is notable for not displaying the camp and is an escapist, romantic view of the island made more attractive, despite its crude design, with a glow of sunset provided in the painted scene. A similar, smaller fort (now no longer standing) can also be seen. The central panel of a wooden marquetry tray shows an unusual view of the camp, but this is peripheral and the focus is concentrated on the bay, emphasising the place as perceived and experienced by someone when outside the camp (fig 11B).Footnote 74 These items demonstrate how craft production, noted in the American Embassy inspection of 1916,Footnote 75 was creating products that could be given or sold as souvenirs, erasing the war and even their producers, from the scene. These are celebrations of the Jersey landscape, the prisoners’ place of incarceration. It is possible that these were merely commercial transactions, with no empathy on the part of the maker for this view and setting, but given that it is close to the camp, albeit only visible on a walk with guards, suggests that there is some positive relationship with the wider Jersey landscape and coastline embodied within the marquetry.

Fig 11. Marquetry produced in the camp. A: box lid with La Rocco Tower; B: tray, 11.8cm × 21.0cm, with central roundel depicting St Ouen’s Bay and La Rocco Tower with part of the camp in the foreground. Photographs: G Carr, courtesy of Damien Horn (A) and H Mytum with permission of Jersey Museum (B).

Two parts of cattle tibia have survived as carved souvenirs of the camp (fig 12). One is adorned with a tulip with the word andenken (souvenir) at the top and a carved collar of geometric shapes, perhaps reminiscent of a typical Jersey granite wall, at the bottom. It is identical in form to numerous contemporary vases produced by civilian internees on the Isle of Man,Footnote 76 so it is probable that it reflects a form of vase that may have already been in use in Germany before the war. A section of cattle tibia, probably a napkin ring, is carved with the surname ASCHE and ‘Isle of Jersey’. The name may be that of the carver or the original user of the item, but it indicates that a relationship or friendship of sorts must have been struck up between the prisoner of war and guard, and the prominence of the named place shows how the island itself was significant to the creator, a sentiment also expressed on similar Manx internee items.Footnote 77 Prisoners created their own worlds within the camp, insulated from the unstable and ever-changing world outside. The island location further emphasised this isolation, yet also reinforced the sense of place.

Fig 12. Carved bone craftwork labelled as a souvenir, and surname ASCHE in false relief and inscribed ‘Isle of Jersey’. Photograph: G Carr with courtesy of Martin Walton.

One other item emphasises Jersey as a place. A whisky bottle (which was more likely to have come from a guard than a prisoner) shows a detailed and colourful scene comprising a grey warship, mounted with guns and a British flag, sailing past a landscape studded with Jersey flags; here, as with the napkin ring, it is Jersey as a place that is being celebrated (fig 13). It was made by a prisoner of war, but the choice of a British ship suggests that it was for a guard.

Fig 13. A ship in a bottle made in the camp; a British warship passing the coast of Jersey with its flags. Photograph: G Carr, courtesy of Damien Horn.

Place unmaking and remaking after the prisoners left

The camp had to be removed after the war; it no longer had any value as a place to the inhabitants of Jersey. Everyone who had occupied it during the war, however significant it had been in their lives during that time, had departed. The camp became a non-place, one unmade by the eventual return of the prisoners to Germany, and irrelevant to the physical and social landscape in which it sat. The structures were dismantled and sold off, and only those remains such as the latrine blocks and the barrack piers that had no reuse value were left.

A mound close to the domestic midden outside the northern guard buildings comprised heavily rusted and unidentifiable iron – probably corrugated iron sheets – and charred wood. This may represent debris from the camp swept to the edges of the area of habitation in the final demolition of the site, but it could also reflect civilian refurbishment of cottages. However, in the eastern area of the camp a prominent mound with similar numerous iron fragments suggests that the clearance involved creation of such mounds; the location of the second mound was away from the road and is unlikely to be civilian domestic refuse.Footnote 78

The buried infrastructure was also removed if of value, and for this reason the magnetometry did not locate the metal water pipe system, as this had been recovered for reuse and recycling. The line of the major cast iron water pipe that fed from the arrangements at the spring was identified during the survey as a robber trench that was not backfilled and was substantial enough to survive sand wind-blow, but their significance was forgotten, and gradually parts of the camp were consumed by the shifting dunes (fig 4B).

The placemakers are now the dog walkers and the ecologists who value the coastal dune landscape, unusual in Jersey and so given statutory protection but with limited significance thus far given to its cultural heritage.

POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE PLACEMAKING

The subject and compositional choices for the craft products reveal interests, associations and conscious or unconscious values of place. The products themselves, once viewed, acted to create and recreate the importance of places. Placemaking is directed and reinforced through the viewpoint depicted in the image. Most surviving views of the camp show the guards’ barracks in the foreground, red-roofed prisoners’ barracks in the middle ground, the hospital and the outside world beyond (fig 7). The background is hills on one side and the sea on the other. This reflects the degree to which the world of the camp and the existence of those inside it had shrunk to this small geographical area at the bottom of St Ouen’s Bay, but also how the guards, the consumers of most of these images (indicating why they survive locally), knew this wider landscape largely outside the internee experience. To have visualised this perspective of the camp and its setting, the artist was either allowed out to climb to this vantage point or, more likely, was given a photograph of this view, as such photographs do survive (fig 4A).

Accompanied by guards, regular marches of up to six miles enabled around three hundred prisoners at a time to see beyond the barbed wire, with up to three walks a week allowed if the weather was suitable.Footnote 79 Even a little less than a three-mile radius would allow a wide range of terrain to be experienced (fig 1). In addition, groups were taken out of the camp and down to bathe in the sea a short distance away, although this was not without any danger, with one prisoner drowned despite a rowing boat manned by prisoners in the bay assisting any who got into difficulties – in this case too late.Footnote 80

Funerals were another occasion on which prisoners were allowed out of the camp. Ten prisoners died while interned, and were buried locally in the strangers’ section of St Brelade’s church burial ground following a funeral service held in the camp with all prisoners present. Only around 150 were allowed to attend the interment, about an hour’s march away (fig 1).Footnote 81 Surviving photographs of a funeral procession show the use of a horse-drawn hearse, the presence of the camp brass band and the large number of prisoners in uniform accompanied by guards.Footnote 82 The churchyard would have had a strong emotional significance to the prisoners, and participation in the burial rituals would have created a place of significance. The laying to rest of comrades who were never to return to their homeland comprised a package of placemaking activities.

A cattle scapula painted black with gold lettering appears to have been a display item of the Royal Hampshire Regiment, which indicates the significance to both guards and prisoners at the funeral ceremonies (fig 14). Marked with the years 1915–16, the regiment’s cap badge – flanked by flags and capped with a crown – sits atop a gold-bordered classic image of the camp, with the guards’ quarters in the foreground. This was perhaps made in gratitude to commemorate a specific event: on 12 May 1916, Konrad Flechig of the 243rd Infantry Regiment died of cancer at the camp, and at his funeral the men of the Hampshire Regiment formed a guard of honour to line the route and reversed their guns as a mark of respect. On the reverse of the bone is a view of the camp, which covers the whole of the surface and is an unusual one within the surviving repertoire. Taken from the south and from a height, it sets the camp within the dunes and the sweep of St Ouen’s Bay and foregrounds the exercise area and the prisoner of war camp with the guards’ accommodation in the background. Here, the prisoner space and experience is prioritised over that of the guards. It is also the view obtained on the return from St Brelade church, a perspective emphasising the brief external experience before returning to the introspection of camp life. The two camp images together commemorate the shared landscape location where both guards and prisoners were living – and some dying – and with the contrasting experiences of camp space for each. Even in the large image, however, the boundaries of the camp and the observation platforms and access steps are dominant. The meanings of the camp and its components were different for each side, although the reciprocal relationships were at least at times cordial and respectful, as indicated by this and other craft products.

Fig 14. Ox scapula with two contrasting views of the camp and its setting. Top: black background with the Royal Hampshire Regiment cap badge surrounded by flags and crow, with ‘German Prisoners Of War Camp Jersey 1915–16’ and a roundel with the guards’ view of the camp; Bottom: view of the camp from the south with the exercise yard in the foreground and the northern part of St Ouen’s Bay in the background. Photographs: G Carr, courtesy Damien Horn.

The churchyard was within the range of the exercise marches and so prisoners and their military escorts may have visited or at least passed close by the site, reinforcing its significance. No contemporary grave markers survive as the bodies were exhumed and placed in Mont de Huisnes German Military Cemetery in France in 1961, but photographs of memorials of those who died at Knockaloe, Isle of Man, were all of a similar and distinctively German style, and definitely a culturally specific placemaking endeavour.Footnote 83

Not all prisoner activities were within the authorities’ rules. Escapes and escape attempts from the camp were recorded in both the local press and in the official account of the camp’s construction and daily life,Footnote 84 but only two were briefly successful. This communal effort for what appears to be a minority of prisoners reinforced a sense of place of resistance, a place where even in confinement the conflict could be enacted. These can be viewed as placemaking resistance efforts, both for those attempting escape and indeed the guards attempting to prevent this – justifying their role away from families, fighting their own form of the war. The attempts also created places to be remembered, to know that comrades could challenge authority, that the interned were not passive accepters of their fate.

In one of the escape attempts, a tunnel was built under a hut using a tin can, with the sand placed on a flat tray that was drawn back and forth by means of a long string. Naish recorded how the sand that accumulated under the barrack hut was scattered by the wind overnight, leaving no trace. Intriguingly, Naish noted and confiscated the beef-fat-burning lamp, made from a biscuit tin, used by the prisoners during their excavations, but neither the biscuit tin, flat tray nor the tin used as an excavation tool appear to have survived. However, it may be noteworthy that one of the camp landscape scenes is painted on a tray; this may have been a reminder of the tools used in an escape, although it was also one of few objects available in the camp on which a large scene could be portrayed (fig 15). These repurposed food containers and cooking items suggest that a prisoner who worked in the cook house was involved in the escape attempt; these reused mundane objects indicate that at least some prisoners were engaged in resistance to internment, and the location of the tunnels created places that indicate prisoner agency and preserve their military worth.

Fig 15. Metal tray with a large painted scene from the north east. The inscription in the rectangular panel states ‘German Prisoners Of War Camp Jersey 1914 15 16’. Photograph: G Carr, courtesy of Damien Horn.

Two surviving postcard images, drawn by prisoner Hans Müller, provide an inmate’s perception of the camp. One drawing shows a monochrome view from above the south-eastern corner of the camp and, while it again suggests the external viewer perspective as dominant, it is one that excludes the guards’ complex. This represents a rare surviving inmate perspective, and it may have been a postcard design that the prisoners could send to their families (fig 16A). It emphasises the prisoner of war perspective of the place where they have made by their home, excluding the guards’ camp, which they never experienced. Instead it focuses on the barracks and with the exercise area – the main space for socialising – which is in the foreground. Although the prisoners are only mere dots in the vista, they are seen in a well-organised, tidy camp, set in a scenic location. The nested placemaking is also revealed at a smaller scale in another postcard by the same artist, with the view of a single barrack (fig 16B). Without people, it shows the focus of daily life around the barrack building, the sand building up against the sides although one brick pier is still visible. The title of this sketch, Unsere Burg (our castle), suggests that this possibly ironic title reflects the prisoners’ attachment to their domestic space, filled with military, their defence against the external world. The barrack interior does not survive in the art (it would have been of no interest to the guards, who have only commissioned and retained items that related to their experience), but even so there are some photographs to show placemaking at a personal scale.

Fig 16. Sketches by prisoner Hans Müller. A: view of the camp from the south, excluding the guard’s accommodation and with a strong focus on the prisoners’ world; B: sketch of a barrack building on brick piers, though with encroaching sand dunes. Photographs: G Carr with permission of the private owner (A) and Société Jersiaise (B).

The ship bottle previously discussed showing a German ship, the Else (fig 8B),Footnote 85 reveals the maker’s idealised place, an imaginary and imaginative escape from the camp, a memory of a past place and perhaps an anticipation of a future return to that place created through the mariner’s normal practices. While the postcards revealed the prisoners’ world within the camp, this bottle, perhaps more than all the others, demonstrates a determination to escape, albeit only imaginatively, from its confines and return to normality.

The few group photographs that survive from the camp are of barrack members and of the band, which created a positive visual message to send to worried relatives but also materialised memories of friends and activities. Some photographs are clearly visible on the barrack walls on internal scenes, although it is notable that the equivalent Manx photographs display far more material culture displayed by internees’ space.Footnote 86 The personalisation of the bed space was one of the few ways by which placemaking at an individual level was possible in the crowded camp.

For the prisoners, this was a landscape of shame, of frustration, but also of camaraderie and survival – away from the horrors of the front where existing skills were developed and new ones learnt. The painting and carving were actions that, by creating and recreating certain imagery of the camp and its setting, were placemaking in giving it a significance worthy of art and craftwork. And yet this landscape – and the relationships between guards and prisoners – was also one of hierarchy and control, and this is reflected in the prisoner art that shows particular perception of the place. The guards dictated the design of their desired souvenir of the camp, and the prisoners were the ones who replicated it again and again for the guards’ delight. The artists were the agents who created the placemaking images, but to the specified desires of the guards who were therefore also with agency. Those views foregrounded the guards’ barracks – the place for the guards that was their camp home, with the prisoners’ much larger compound depicted as a more remote, telescoped component. The alternative views, though rare in the surviving art (although perhaps not in the total of what was produced), reveal that other scales of place were represented, from ships and barracks to the whole camp without the guards’ accommodation visible.

CONCLUSIONS

Placemaking was conducted by numerous actors from their respective positions during the four years that the Les Blanches Banques camp was in existence. Although ephemeral and transitory, it dominated the lives of all those involved for the length of their presence on the site. This was a unique form of existence for both prisoners and guards, in a liminal existence away from family and friends while the maelstrom of total war was taking place only a relatively short distance away across the Channel. This placemaking was therefore constructed within a particular nexus of time, space and prisoner of war relationships. The bulk of the physical remains of the camp were removed in an act of erasure, although not all traces could be removed. However, that phase of significance was largely lost as the population to whom the place carried meanings dispersed, but the surviving craft items reflect memories that were valued and curated, and more were presumably taken back or had been posted to Germany by prisoners and may yet be identified.

Analysis of surface and subsurface survey results combined with that derived from documentary sources and artefacts allows a multi-faceted consideration of the ways in which the various groups of actors – guards and prisoners – perceived their built environment and the wider landscape, and how they created places of significance within it. The camp designer and commandants had the agency to manage the security and welfare of the prisoners, albeit constricted by the structural limitations of finance, supply, attitudes to prisoners and wider expectations of prisoner conditions at the time. They anticipated the practical issues of sleeping, washing, eating and exercising, but it was the inhabitants of the camp who gave meaning to both these activities and the places in which they took place.

Guards could relax both within the community and in their own camp recreation building, and commission craft products from prisoners. This is materially attested through the surviving structural and infrastructural components identified during the field survey and elaborated through use of the visual images of the camp created at various points through its life. These images then acted to reinforce memories and meanings of place to the viewers, and they were prompts for recounting experiences to others. The prisoners were constrained by the structures of military discipline and additional rules imposed by the camp authorities, which were materially manifested by the buildings and infrastructure. The images of the camp cannot avoid the dominance of the fenced perimeter, although the distant views mean that the common prisoner of war trope of the barbed wire is avoided in the extant craftwork, suggesting more positive attitudes to the camp as a place. The prisoners showed agency through placemaking, with cultural, sporting and educational activities giving meanings to particular places within the camp, and outside in their managed activities at the beach and on walks. They personalised the spaces around their beds, they had small-scale networks of movements in daily life around parts of the camp and occasionally experienced the wider landscape through managed excursions. These are the nested scales of placemaking seen in the use of the camp architecture and plan, and depicted in the craftwork.

The actions of the guards also had a direct effect on the prisoners, and they clearly coped by developing relationships with them that led to the production of craft items that were either given or sold and that showed the customers’ perceptions of place.Footnote 87 Although there was some resistance, as demonstrated by a few escape attempts, it is hard to identify widespread defiance; the camp experience was not ideal for guards or prisoners, but the external inspection that stated that the ‘camp seemed to be almost a model of its kind’ may be confirmed from the material remains.Footnote 88 The numerous images of the camp as a whole suggest that all inhabitants felt that this was a place of significance in their lives, and one that could be celebrated through imagery which emphasised order in a beautiful landscape, a place of peace during a time of conflict and one where they shared experiences which would be remembered for the rest of their lives.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Jersey States Department of the Environment for granting permission for the survey. Local historians and collectors Mark Lamerton, Martin Walton, Damien Horn and Colin Isherwood and the Société Jersiaise kindly facilitated access to their collections and contributed their insights into the camp’s history, and Jersey Heritage (Jersey Museum and HER) and the Société Jersiaise allowed reproduction of images. Funds for the fieldwork was provided by the Société Jersiaise; McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge; University of Liverpool; and the Society of Antiquaries of London.