Many developing countries have been undergoing a rapid nutrition transition with sharper increases in rates of obesity and obesity-related chronic diseases compared with those observed in developed countries( Reference de Onis, Blossner and Borghi 1 – Reference Rueda-Clausen, Silva and Lopez-Jaramillo 3 ). Childhood obesity is of special concern because, in addition to its multiple adverse effects on health in the short term( Reference Must and Strauss 4 ), it tracks into adulthood( Reference Singh, Mulder and Twisk 5 ) and predicts the development of chronic diseases later in life( Reference Must and Strauss 4 ). While research has focused on the immediate causes of childhood obesity that affect energy balance, including dietary intake and physical activity( Reference Gupta, Goel and Shah 6 , Reference Uauy and Diaz 7 ), fewer studies have focused on the role that psychosocial characteristics may play in this epidemic. Body image perception, defined as ‘the picture we have in our minds of the size, shape and form of our bodies; and our feelings concerning these characteristics and our constituent body parts’( Reference Slade 8 ), is one critical psychosocial factor that is related to body weight. While mostly investigated in the context of eating disorders, body image dissatisfaction (BID) is highly prevalent among healthy boys and girls( Reference Lowes and Tiggemann 9 – Reference Tremblay, Lovsin and Zecevic 12 ).

BID is associated with weight status, as heavier persons tend to be more dissatisfied with their body image compared with normal-weight people. The common assumption is that increased weight leads to dissatisfaction with one’s body. However, BID may lead to obesity through an increase in sedentary behaviour( Reference Colella, Morano and Robazza 13 , Reference Morano, Colella and Capranica 14 ) or through social isolation and depression( Reference Ali, Fang and Rizzo 15 , Reference Swallen, Reither and Haas 16 ). Body image concerns and weight-related anxiety may also contribute to excessive weight gain over time( Reference Lynch, Liu and Wei 17 ). Yet, the vast majority of these studies investigating the associations between BID and weight status in children have been cross-sectional in nature. While obesity can lead to BID, cross-sectional studies do not allow ascertaining whether BID could also lead to obesity.

BID is likely to increase in developing countries( Reference Becker, Gilman and Burwell 18 ) in parallel with urbanization and exposure to mass media that promote stereotypical ideas of body shape( Reference Chen, Fox and Haase 19 – Reference Xu, Mellor and Kiehne 22 ). Because body image perception is potentially modifiable( Reference Stice, Shaw and Marti 23 ), it is crucial to determine whether it can lead to the development of adiposity in children over time.

We conducted a prospective study to investigate whether BID predicts development of adiposity in school-age children. These children were recruited from public schools of Bogotá, Colombia, an upper middle-income country undergoing epidemiological and nutrition transitions in recent years. We hypothesized that BID may predict differences in the growth trajectories of children.

Methods

Study population and field methods

The study was conducted using data from the Bogotá School Children Cohort Study, a nutrition and health study of primary-school children in Bogotá, Colombia. As previously described( Reference Arsenault, Mora-Plazas and Forero 24 ), recruitment was based on a cluster sampling strategy, in which clusters were defined as classes from all 361 primary public schools in Bogotá by the end of 2005. In February 2006, we enrolled 3202 children aged 5–12 years who represented 2981 households, after accounting for siblings. The study population is representative of low- and middle-income families in the city, since the majority of children in the public school system are from these strata( 25 ). Self-administered questionnaires were filled out by parents during the first week of classes (82 % response rate). The questionnaires inquired about sociodemographic characteristics including maternal age, birthplace, marital status, parity, years of education and indicators of household socio-economic level. These included the local government’s classification of neighbourhoods for tax and planning purposes, home ownership status and number of home assets (including bicycle, refrigerator, blender, television, stereo and washing machine). We also collected data on additional predictors of the children’s weight gain that could confound the associations of interest. Maternal BMI was calculated from measured height and weight in 40 % of the mothers and from self-reported data otherwise. Information on the child’s time spent playing outdoors or in front of a screen was also collected at baseline.

During the three weeks post-recruitment, professionally trained research assistants visited schools and obtained information on body image perception from a randomly chosen sub-sample of 629 children. This was achieved with use of a Stunkard-like figurine rating scale( Reference Stunkard, Sorensen and Schulsinger 26 ) which had been previously adapted and validated in children( Reference Mciza, Goedecke and Steyn 27 ). This sex-specific visual tool depicts eight silhouettes in an increasing order of body girth from 1 (thinnest) to 8 (heaviest). Children were asked to indicate specific silhouette numbers in response to questions regarding their perceptual body image, i.e. to identify the silhouette that resembled their current body image, and their attitudinal body image, i.e. the silhouette that represented the body image they desired to have. At the same school visits, height and weight of the children were measured using standard protocols( Reference Lohman, Roche and Martorell 28 ), after they had indicated the silhouettes in response to the body image questions. Height was measured without shoes to the nearest 1 mm using wall-mounted portable Seca 202 stadiometers, and weight was measured in light clothing to the nearest 0·1 kg on Tanita HS301 solar-powered electronic scales.

Study dietitians visited children at schools again in June and November 2006 and annually thereafter until 2008. At these visits, new anthropometric measurements were obtained, following the same protocol. When children were absent from school on the day of assessment, home visits were arranged and the measurements took place at home. Sex- and age-specific height-for-age Z-score (HAZ) and BMI-for age Z-score (BAZ) were calculated according to the WHO 2007 growth reference( Reference de Onis, Onyango and Borghi 29 ).

Written informed consent was obtained from parents or primary caregivers of all children prior to enrolment as previously described in detail( Reference Arsenault, Mora-Plazas and Forero 24 ). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National University of Colombia Medical School and the Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan.

Data analysis

The 629 children included in the study did not differ from the rest of the cohort in terms of sex, age, socio-economic status or anthropometric characteristics. BID score was calculated as the difference of current minus desired silhouette number. BID was categorized as negative when desired body image was greater than current body image, representing a desire for a heavier body size. For example, if a child marked silhouette 5 as desired and 4 as current, his/her BID score would be –1, representing a desire for a heavier body (BID = [–]). BID was 0 when desired body image was equal to current body image, reflecting satisfaction with body image (BID = [0]); or positive when desired body image was smaller than current body image, i.e. a desire for a thinner body (BID = [+]).

Average BMI-for-age growth curves were estimated for each BID category with the use of mixed-effect models for repeated measurements with restricted cubic splines( Reference Durrleman and Simon 30 ). Cubic splines represent non-linear terms for age at each assessment that allow the smoothing of a growth curve. Piecewise cubic polynomials were smoothly jointed at joint points or ‘knots’( Reference Durrleman and Simon 30 ). We placed these knots at 6, 8, 10, 12 and 13 years of age in order to properly capture the curvilinear segments of the BMI-for-age curve during this period. Each model included BMI as the outcome, whereas predictors were indicator variables for BID categories, linear and spline terms for child age in decimal years, and interaction terms between BID category indicators and the linear and spline terms for age. We included random effects for the intercept and the linear term of age (slope) to account for within-child correlations of measurements in the estimation of variance( Reference Diggle, Heagerty and Liang 31 ). All available measurements were included in the models since these methods do not require that all participants provide the same number of measurements or that these measurements be obtained at the same time( Reference Lourenco, Villamor and Augusto 32 ). The outcome of interest was change in BMI between age 6 and 14 years, estimated from the growth curves for each BID group. This estimation of sub-population growth trajectories over the age range of measures contributed by individuals is valid even if each participant was not followed fully over the estimation period, under the assumption of lack of birth cohort effects. We evaluated this assumption by including interaction terms between age at recruitment and BID in the models. These terms were not statistically significant and their inclusion did not change the point estimates for BID; thus, we concluded that the assumption was fulfilled. Adjusted differences in change with 95 % confidence interval were estimated between BID exposure groups by introducing potential confounders into the mixed models as additional covariates. These included previously reported correlates of child overweight in this population, such as child birthplace, maternal marital status and BMI, and household socio-economic status( Reference McDonald, Baylin and Arsenault 33 ). Further adjustment for time spent outdoors or in front of a screen as indirect measures of physical activity did not change the results. Analyses were conducted separately for boys and girls and according to measured weight status of the child at baseline since both BID and weight trajectories depend on initial weight. We categorized participants by their BAZ at the time of recruitment as of low BAZ (<−0·5), adequate BAZ (≥−0·5 and <0·5) or high BAZ (≥0·5). These cut-offs were chosen to assure that the normal-weight children had an especially low risk of being either under- or overweight at baseline by carefully separating them from the groups of children with lower or higher BAZ.

All analyses were conducted with the use of the statistical software package SAS version 9·2.

Results

Forty-nine per cent (n 309) of children in the study were girls (Table 1). Mean age at the time of recruitment was 8·6 (sd 1·7) years. Mean HAZ and BAZ were −0·7 (sd 0·9) and 0·1 (sd 1·1), respectively. Overall, mean BID score (current minus desired silhouette) was 0·1 (sd 1·7). Thirty-eight per cent, 22% and 40 % of the children had negative, zero and positive BID, respectively. Among girls, these proportions were 36 %, 23 % and 41 %; whereas in boys they were 40 %, 22 % and 38 %, respectively. Mean follow-up time was 28·0 (sd 7·1) months, during which children contributed 2608 anthropometric measurements, with a median of 4 per child. The number of available measurements during follow-up at each year of age ± 6 months from 5 to 15 years was 21, 119, 247, 313, 450, 519, 457, 321, 124, 27 and 10, respectively. Thus, the estimation of BMI change was based on data that amply represented the growth period of interest.

Table 1 Characteristics of the schoolchildren and their mothers at the time of recruitment, Bogotá, Colombia

HAZ, height-for-age Z-score; BAZ, BMI-for-age Z-score; BID, body image dissatisfaction; TV, television.

* According to the WHO 2007 growth reference( Reference de Onis, Onyango and Borghi 29 ).

† BID was calculated as the desired body image subtracted from current body image, according to the child’s rating of child-adapted Stunkard scales.

‡ From a list that included bicycle, refrigerator, blender, TV, stereo and washing machine.

§ Stratum 1 or 2 of a maximum 4 in the sample, according to the government’s classification for tax and planning purposes.

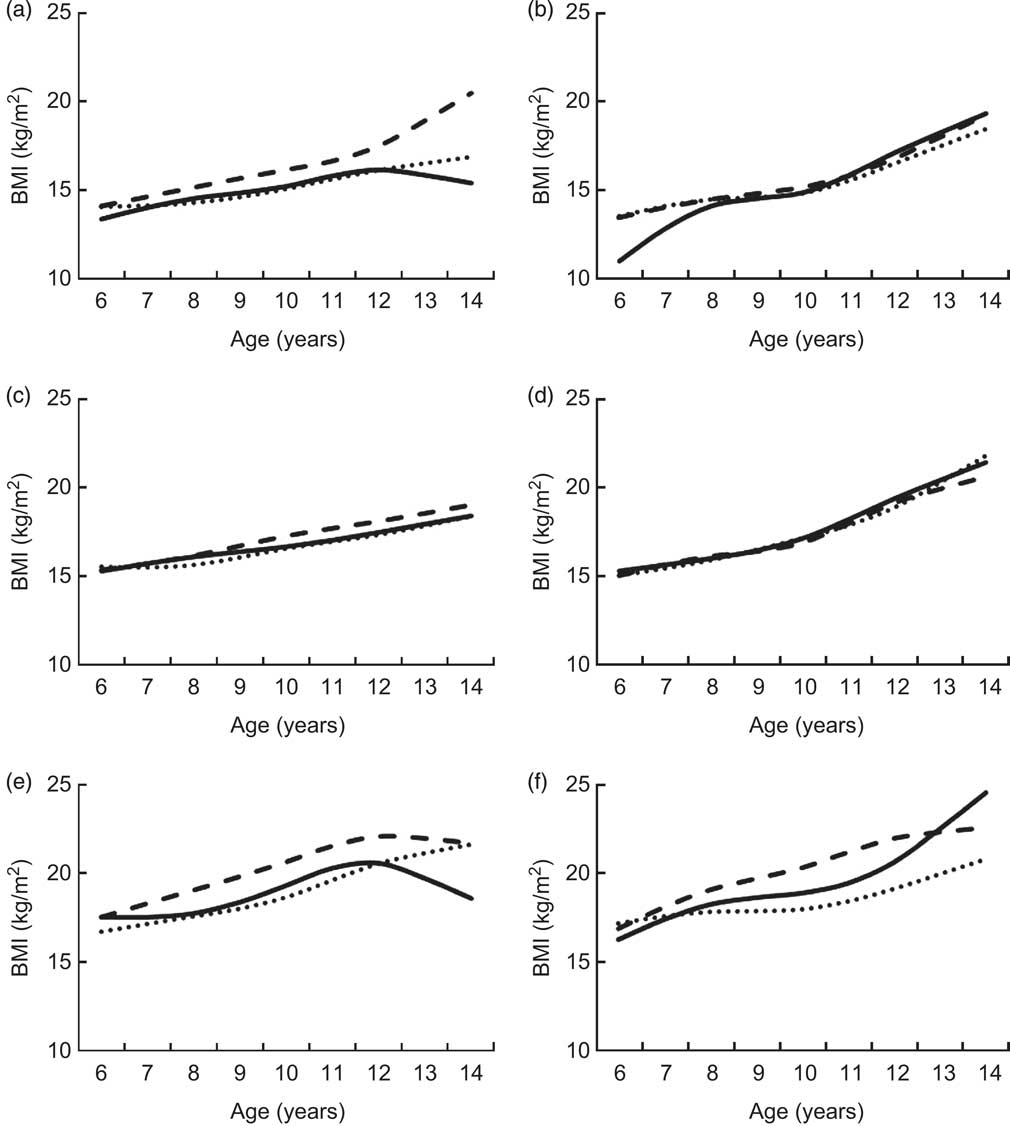

Among children with low or high BAZ at baseline, BID significantly predicted BMI trajectories (Fig. 1). In multivariable analyses (Table 2), boys with baseline BAZ < −0·5 who desired to be thinner gained an estimated 5·8 kg/m2 more BMI from age 6 to 14 years, compared with low-BAZ boys without BID (P = 0·0004). The increase was larger after age 12 years. Boys with baseline BAZ ≥ 0·5 who desired to be heavier gained an estimated 4·2 kg/m2 more BMI than high-BAZ boys without BID at the time of recruitment (P = 0·003). Boys with high BAZ who desired to be thinner gained an estimated 3·3 kg/m2 (P = 0·007) more BMI than their peers who were satisfied with their body image at baseline. Low-BAZ girls who desired to be heavier gained an estimated 3·1 kg/m2 less BMI compared with their peers without BID at the time of recruitment (P = 0·0008). Similarly, low-BAZ girls who desired to be thinner gained an estimated 2·2 kg/m2 less BMI between age 6 and 14 years, compared with their low-BAZ counterparts who were satisfied with their body image at baseline (P = 0·05). Among girls with high BAZ, those who desired to be heavier gained 4·8 kg/m2 less BMI than those without BID at enrolment (P = 0·0006). No associations were observed between the level of BID and BMI change among boys or girls with baseline BAZ ≥−0·5 and <0·5.

Fig. 1 Estimated BMI change from age 6 to 14 years according to body image dissatisfaction (BID) in school-age children ((a), (c) and (e), boys; (b), (d) and (f), girls) from Bogotá, Colombia, stratified by weight status at baseline ((a) and (b), baseline BAZ < –0·5; (c) and (d), baseline BAZ ≥–0·5 and <0·5; (e) and (f), baseline BAZ ≥ 0·5). BMI-for-age growth curves were constructed using restricted cubic splines mixed models with BMI as the outcome and spline terms for age, indicator variables for BID and their interaction terms as predictors. Robust estimates of variance were used in the models. BID was calculated as current minus desired body image according to the child’s rating of child-adapted Stunkard scales: ![]() , [−], desired > current body image (i.e. ‘a desire to be heavier’);

, [−], desired > current body image (i.e. ‘a desire to be heavier’); ![]() , [0], desired = current body image (i.e. ‘satisfied with body image’);

, [0], desired = current body image (i.e. ‘satisfied with body image’); ![]() , [+], desired < current body image (i.e. ‘a desire to be thinner’). BAZ, BMI-for-age Z-score, according to the WHO 2007 growth reference(

Reference de Onis, Onyango and Borghi

29

)

, [+], desired < current body image (i.e. ‘a desire to be thinner’). BAZ, BMI-for-age Z-score, according to the WHO 2007 growth reference(

Reference de Onis, Onyango and Borghi

29

)

Table 2 Estimated BMI change from age 6 to 14 years according to BID in school-age children from Bogotá, Colombia, stratified by weight status of the child at baseline

BID, body image dissatisfaction; BAZ, BMI-for-age Z-score.

* Values are estimated from BMI-for-age growth curves obtained with restricted cubic splines mixed models with BMI as the outcome and spline terms for age, indicator variables for BID and their interaction terms as predictors. Differences in change and 95 % confidence intervals were adjusted for child’s height-for-age Z-score and birthplace, and for maternal BMI and marital status at baseline, as well as for household socio-economic status. Robust estimates of variance were used in all models.

† According to the WHO 2007 growth reference( Reference de Onis, Onyango and Borghi 29 ).

‡ BID was calculated as the desired body image subtracted from current body image, according to the child’s rating of child-adapted Stunkard scales.

Discussion

In the current longitudinal study of school-age children from Bogotá, Colombia, we found that baseline BID was associated with BMI change during follow-up, with important differences according to sex and baseline weight status. BID was related to faster weight gain in boys with high BAZ at baseline and to slower weight gain in low-BAZ girls. Also, low-BAZ boys who desired to be thinner gained more weight than those without BID and high-BAZ girls who desired to be heavier gained less weight than those without BID. Although it is not possible to determine whether body image perception is causally related to the development of adiposity from this observational study, the results indicate that children’s dissatisfaction with their body may play an important role in their growth process.

Previous studies had suggested that childhood obesity was associated with a desire to be thinner whereas thinness was related to a desire to be heavier( Reference Pallan, Hiam and Duda 10 , Reference Colella, Morano and Robazza 13 , Reference McArthur, Holbert and Pena 34 , Reference Xanthopoulos, Borradaile and Hayes 35 ). In other words, overweight and obese boys and girls tend to desire a thinner body image, while thin children usually desire to be heavier (or less thin). However, these studies had a cross-sectional design which prevented them from establishing whether BID influences weight status or vice versa.

Our results extend the current body of literature in several ways. First, we conducted a longitudinal investigation in which BMI change, as it relates to baseline BID levels, was ascertained over time. Second, we examined the associations between BID and BMI after stratifying the children according to their sex and their actual weight status at baseline. Associations of BID with BMI trajectories were found among children with high or low BAZ at baseline, who were likely to be more concerned with their body image compared with normal-weight children. We found that any BID among high-BAZ boys led to faster weight gain; similarly, any BID among low-BAZ girls led to slower weight gain. This indicates that the mere presence of BID, and not specifically a desire to be heavier or slimmer, might influence weight gain over time and may worsen any ongoing trends towards excessive weight gain or thinness. Furthermore, the potential effects of BID seem to occur in opposite directions for boys and girls. The associations between BID and weight gain could be explained by weight-control behaviours like skipping meals or binge eating( Reference Sonneville, Calzo and Horton 36 ), or by overweight-related anxiety that may impair one’s coping capabilities and thus lead to additional weight gain( Reference Lynch, Liu and Wei 17 ). BID could potentially contribute to excessive weight gain via additional behavioural and social pathways, including a reduction in physical activity( Reference Colella, Morano and Robazza 13 , Reference Morano, Colella and Capranica 14 ), social isolation and depression( Reference Ali, Fang and Rizzo 15 , Reference Swallen, Reither and Haas 16 ). Future research on the extent to which these mechanisms are sex-specific could explain the modifying effect of sex on the associations between BID and BMI.

Of note, BID in adequate-BAZ children was not associated with excessive weight gain over follow-up in our study. These findings differ from those of previous longitudinal studies of the association of BID with weight trajectories among normal-weight individuals. A prospective study conducted in Norway( Reference Cuypers, Kvaloy and Bratberg 37 ) found that normal-weight adolescents of both sexes who perceived themselves as overweight at baseline gained significantly more weight during an 11-year period compared with adolescents who were satisfied with their body weight. These differences remained statistically significant after adjusting for physical activity and sedentary behaviour, socio-economic status, social activity and eating behaviours. In the longitudinal Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study conducted in adult men and women in four US cities( Reference Lynch, Liu and Wei 17 ), normal-weight white men and women who perceived themselves as overweight at baseline gained more weight compared with adults of the same sex or race who perceived themselves as normal weight. The fact that we did not observe an association of BID with weight trajectories in adequate-BAZ children, by contrast with previous studies, may be a result of various factors, including differences in the length of follow-up, varying prevalence of body image concerns and associated behaviours across populations, heterogeneity in the assessment of body image and the age distribution at baseline, since participants were younger in our study than those in previous investigations and concerns with body image may increase with age( Reference Ricciardelli and McCabe 11 ).

There are several strengths to our study. First, it was conducted in a large sample of children representative of a population that is undergoing rapid increases in childhood obesity. We used state-of-the-art analytic techniques to fit growth curves and had the possibility to examine sex- and weight-specific associations. In addition, the longitudinal design provides an opportunity to examine the directionality of the associations between BID and excessive weight gain, and therefore offers an advantage over prior cross-sectional studies. Last, the present study enhances our understanding of the relationship of BID with weight gain in children from developing countries, where information is scant.

One limitation of the study is the reliance on a single measurement of exposure (BID) at baseline. We assumed that it remained constant during the follow-up period. If this assumption does not hold, it is not possible to completely preclude reverse causality as a potential explanation of the findings. For example, higher weight gain in children who were already overweight and therefore dissatisfied could have led to continuous dissatisfaction over follow-up. Also, although we controlled in the analyses for important covariates, residual confounding by unmeasured common causes of BID and BMI change cannot be completely ruled out. Sexual maturation status could be one of those potential confounders that we did not measure. We cannot necessarily equate changes in BMI to changes in adipose tissue since, among children and adolescents, BMI increases represent changes in both fat mass and fat-free mass. Finally, while the adapted Stunkard scale has been successfully validated in comparable settings( Reference Mciza, Goedecke and Steyn 27 , Reference Stevens, Story and Becenti 38 ), it has not been formally evaluated in our population.

In sum, our findings suggest that body image self-perception in school-age children may play an important role in excessive weight gain during this sensitive period. Since childhood obesity is increasing at an alarming rate in developing countries, meticulous characterization of its causes in the context of the nutrition transition is required for the design and implementation of successful public health interventions. BID can be ameliorated through family( Reference Corning, Gondoli and Bucchianeri 39 )- and school( Reference Wick, Brix and Bormann 40 )-based interventions. Thus, clinical or public health activities dealing with BID might have a potential impact on childhood obesity. Future studies are needed to determine whether interventions geared towards modification of body image perception in school-age children affect growth trajectories during childhood and into adolescence.

Acknowledgements

Financial support: The Bogotá School Children Cohort Study is currently sponsored by the ASISA Research Fund at the University of Michigan. Funding sources did not play any role in the design, conduct, analyses or interpretation of the study. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: O.D. contributed to data analyses, interpretation of the results and writing of the first draft of the manuscript; C.M. and M.M.-P. contributed to the study design and data collection; A.B. contributed to the study design, data collection and data interpretation; J.M.L. and C.M.d.L. contributed to data interpretation; E.V. contributed to the study design, data collection and analyses, interpretation of the results and preparation of the manuscript. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript. Ethics of human subject participation: The research was conducted in accordance with guidelines laid down by the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National University of Colombia Medical School and the Health Sciences and Behavioral Sciences Institutional Review Board at the University of Michigan.