Introduction

The Assyrian dialect of Akkadian in the first millennium BCE is closely related to the Babylonian dialect. This, together with their common cultural background and the high degree of interaction and mobility between the two regions means that the personal name repertoires of Assyria and Babylonia overlap to a significant degree. For example, Neo-Assyrian sources mention many individuals who can be identified as Babylonians, whether active in Assyria (as deportees, visitors, or settlers) or in Babylonia (as mentioned, for example, in Assyrian royal inscriptions, or in the Babylonian letters of the official correspondence). Their personal names, for the most part, are indistinguishable from those of the Assyrians themselves. These circumstances make it somewhat challenging to distinguish names of genuinely Assyrian derivation and to identify them in the Babylonian sources.

The Babylonian name repertoire is well established, thanks to the wealth of published Neo-Babylonian everyday documents. For Assyria, The Prosopography of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (PNA) includes not only biographies of all named individuals but also concise analyses of the linguistic background of individual names, together with the attested spellings (Reference RadnerRadner 1998, Reference Radner1999; Reference BakerBaker 2000, Reference Baker2001, Reference Baker2002, Reference Baker2011). The series includes more than 21,000 disambiguated individuals bearing in excess of 7,300 names. The names themselves represent numerous linguistic backgrounds, including Akkadian (Assyrian and Babylonian), Aramaic, Hebrew, Moabite, West Semitic, Phoenician, Canaanite, Arabic, Egyptian, Greek, Iranian, Hurrian, Urarṭian, Anatolian, and Elamite. PNA covers texts of all genres in so far as they mention individuals by name; it forms the basis for any attempt to distinguish between Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian personal names. The focus of this chapter is on presenting the methodology and issues involved in identifying Assyrian names in Babylonian sources, with due consideration of the historical context. The names discussed here are intended to be representative cases; they do not constitute a complete repertoire of Assyrian names documented in Babylonian texts.Footnote 1

Before addressing current approaches to identifying Assyrian names in Babylonian sources, it is worth highlighting a key difference in Assyrian and Babylonian naming practices: while family names are commonly used in Babylonia by members of the traditional urban elite (see Chapter 4), they were never adopted in Assyria. Also, these same members of the Babylonian urban elite regularly identified themselves by their father’s name in everyday documents, whereas in Assyria, with the exception of members of scribal/scholarly families, genealogical information is far less common, being limited to the occasional inclusion of the father’s name. This means that the disambiguation of individuals is generally easier for Neo-Babylonian sources than for Neo-Assyrian ones, especially in the case of common names. One final point to bear in mind: feminine personal names make up around 7 per cent of the total number of names catalogued in PNA, so it is hardly surprisingly that Assyrian feminine personal names can only very rarely be identified in Babylonian texts.

Historical Background

As far as the onomastic material is concerned, the fall of Nineveh in 612 BCE forms a watershed for the presence of Assyrian name-bearers in Babylonia. Evidence prior to the fall of Assyria is slight: John P. Reference NielsenNielsen’s 2015 study, covering early Neo-Babylonian documents dated between 747 and 626 BCE, includes only six individuals bearing names that are clearly Assyrian according to the criteria discussed later in the chapter. They are: Aššur-ālik-pāni ‘Aššur is the leader’ (IAN.ŠÁR–a-lik–pa-ni), Aššur-bēlu-uṣur ‘O Aššur, protect the lord!’ (IAN.ŠÁR–EN–URÙ), Aššur-dannu ‘Aššur is strong’ (IAN.ŠÁR-dan-nu), Aššur-ēṭir ‘Aššur has saved’ (IdAŠ-SUR), Aššur-ilāˀī ‘Aššur is my god’ (IAN.ŠÁR-DINGIR-a-a), and Mannu-kî-Arbail ‘Who is like Arbaˀil?’ (Iman-nu-ki-i-LIMMÚ-DINGIR) (Reference NielsenNielsen 2015, 41–2, 196; cf. Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 5). Aššur-bēlu-uṣur is a particularly interesting case since he served as qīpu (‘(royal) resident’) of the Eanna temple of Uruk at some time between 665 and 648 BCE (Reference BeaulieuBeaulieu 1997, 55–6). The question has been raised of whether he was posted there or belonged to a local family, but, as Karen Radner notes, the office of qīpu denoted the king’s representative as an ‘outsider’, in contrast to the other high temple officials who were drawn from the local urban élite (Reference Radner, Levin and MüllerRadner 2017, 84; cf. Reference KleberKleber 2008, 26–7). In general, though, this scarcity of Assyrian names in Babylonian sources prior to the fall is interesting because a lot of Assyrians were stationed or active in Babylonia during this period of more or less continuous Assyrian domination. The onomastic evidence suggests either that such people seldom bore diagnostically Assyrian names, or, if they did, then they did not integrate or mix with local people in a way that led to them featuring in the local transactions that dominate the extant sources from Babylonia.

The inhabitants of Assyria continued to worship the god Aššur long after the fall of Assyria in 612 BCE, as is clear from the Parthian onomasticon as late as the third century CE (Reference MarcatoMarcato 2018, 167–8). In fact, based partly on the evidence of the Cyrus Cylinder, Karen Radner has recently suggested that the post-612 BCE rebuilding of the Aššur temple at Assur may be attributed to Assyrians who had fled to Babylonia but who returned to Assur after the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus in 539 BCE (Reference Radner, Levin and MüllerRadner 2017). Be that as it may, there is no direct contemporary evidence for actual deportations of Assyrians following the fall of their empire, though it seems clear that a great many people either fled or migrated into Babylonia from the north after 612 BCE. Evidence for this comes mainly in the form of Assyrian personal names in Babylonian texts written during the Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid periods. In the case of Uruk, there is evidence for a flourishing cult of Aššur, with a temple or chapel dedicated to him in that city (Reference BeaulieuBeaulieu 1997). Moreover, one of the texts discussed by Paul-Alain Beaulieu refers to lúŠÀ-bi–URU.˹KI*˺.MEŠ ‘people of Libbāli (= Assur)’ (Reference BeaulieuBeaulieu 1997, 61). This evidence for an Assyrian presence in the south is complemented by the mention of some toponyms of Assyrian origin in Babylonian sources (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 3). While Karen Radner attributed the establishment of the cult of Aššur in Uruk to fugitives who fled Assur following its conquest in 614 BCE (Reference Radner, Levin and MüllerRadner 2017, 83–4), Paul-Alain Beaulieu considers the Urukean cult of Aššur to date back to the late Sargonid period, when Uruk was an important ally of Assyria (Reference BeaulieuBeaulieu 2019, 8).

Text Corpora

The Neo-Babylonian and Achaemenid-period text corpora that contain Assyrian personal names derive especially from the temple sphere, including the archives of Eanna at Uruk and Ebabbar at Sippar. While these two cities dominate the material under discussion, Assyrian names have also been identified in archival texts written in other Babylonian cities, including Babylon and Nippur (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 10–11). A detailed examination of the archival background of the relevant texts, which would assist in further contextualising the Assyrian name-bearers, is outside the scope of the present study; the individual archives and their contents are treated in summary form by Michael Reference JursaJursa (2005).

Principles for Distinguishing Assyrian Names from Babylonian Names

For the sake of the present exercise, we may distinguish three major groups of Akkadian names of the first millennium BCE: (1) distinctively Neo-Assyrian personal names, (2) distinctively Neo-Babylonian personal names, and (3) names that were common to both Assyria and Babylonia. Only names belonging to the first group are of interest here, so our challenge is to define this group more precisely with reference to the other two groups. This process of distinguishing Neo-Assyrian from Neo-Babylonian personal names centres on four key features which may occur separately or in combination, namely: (i) Assyrian divine elements, (ii) Assyrian toponyms, (iii) Assyrian dialectal forms, and (iv) vocabulary particular to the Neo-Assyrian onomasticon. I shall deal with each of these features in turn in the following pages.

Names with Assyrian Divine Elements

With regard to Assyrian divine elements, Ran Zadok has remarked: ‘It should not be forgotten that the Assyrians worshipped Babylonian deities (as early as the fourteenth century), but the Babylonians did not worship Assyrian deities. Therefore, if a name from Babylonia contains an Assyrian theophoric element its bearer should be regarded as an Assyrian’ (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 2). This is a sound methodological principle, although in practice it is of restricted application since there are few Assyrian deities that were not traditionally worshipped in Babylonia: the two pantheons overlap to a considerable extent. The following paragraphs deal with the relevant divine names, their spellings, and their reading.

Aššur and Iššar (Ištar)

The name of the god Aššur is commonly written AN.ŠÁR in Neo-Assyrian royal inscriptions from the reign of Sargon II on, although it is first attested considerably earlier, in the thirteenth century BCE (Reference DellerDeller 1987; Reference BeaulieuBeaulieu 1997, 64, n. 22). However, in Babylonian sources personal names that contain the divine element AN.ŠÁR pose a problem of interpretation. As Simo Parpola notes in the introduction to the first fascicle of PNA, Aramaic spellings confirm that the divine name Ištar was pronounced Issar in Assyria, reflecting ‘the regular Neo-Assyrian sibilant change /št/ > /ss/’.Footnote 2 He also observes that the Babylonian version Iššar was sometimes shortened to Šar, attributing this to aphaeresis of the initial vowel and arguing that this ‘implies a stressed long vowel in the second syllable’.Footnote 3 When this happens, the writing dŠÁR (Iššar) is indistinguishable from AN.ŠÁR (Aššur).Footnote 4 The reading dŠÁR = Iššar is confirmed in some cases by syllabic writings attested for the same individual. Ran Zadok understands Iššar to be a Babylonian rendering of Assyrian Issar; therefore, in his view these names are unquestionably of Assyrian background (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 4). Thus, in Babylonian texts we face the challenge of deciding whether the signs AN.ŠÁR represent Aššur or Ištar. In some instances a clue is offered by the predicative element of the name since some predicative elements work with the divine name Aššur but not with Ištar (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 4, 7–8). An example of this is the name type DN-mātu-taqqin ‘O DN, keep the country in order!’, which is attested with the god Aššur but not with Ištar: PNA lists Aia-mātu-taqqin, Aššur-mātu-taqqin, and Nabû-mātu-taqqin (PNA 1/I, 91, 194–6; PNA 2/II, 846). Conversely, some names formed with AN.ŠÁR have a feminine predicate and therefore the divine element must be read dŠÁR = Iššar rather than Aššur, as in the case of IdŠÁR-ta-ri-bi ‘Issar has replaced’, a name which also has unequivocal writings with diš-tar- and diš-šar- (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 4). Sometimes a predicate is attested with both Aššur and Issar, and thus it provides no guide as to the reading of the divine name. In the case of the temple É AN.ŠÁR, its identification as a shrine of Aššur rather than Ištar is supported by the fact that it is listed among the minor temples of Uruk, making it unlikely that the great temple of Ištar (i.e., Eanna) is intended (Reference BeaulieuBeaulieu 1997, 61).

A further complication is the possibility that AN.ŠÁR might alternatively represent the deity Anšar, although Paul-Alain Beaulieu has argued convincingly against this on the grounds that Anšar was a primeval deity of only abstract character and was not associated with any known cult centre (Reference BeaulieuBeaulieu 1997, 61). Note the attempt to ‘Assyrianise’ the Babylonian Epic of Creation by replacing Marduk with Aššur and equating Aššur (written dAN.ŠÁR) with Anšar, which resulted in genealogical confusion since Anšar was originally Marduk’s great-grandfather (Reference LambertLambert 2013, 4–5). Anyway, a reading Anšar can certainly be discounted: the name Iman-nu–a-ki-i–É–AN.ŠÁR (Mannu-akî-bīt-Aššur ‘Who is like the Aššur temple?’), attested alongside other Aššur names, supports the idea that we are dealing with a deity worshipped in Babylonia at the time (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 3). While it cannot be entirely ruled out that the name-givers intended to reference the original Aššur temple in Assyria as preserved in the folk memory of people of Assyrian descent living in sixth century Uruk, rather than the Aššur temple/chapel in Uruk, the name nevertheless attests to the continuing reverence of Aššur in Babylonia. It is also worth noting that this particular name type, Mannu-(a)kî-DN/GN/TN and variants, is considerably more common in Assyria than in Babylonia: PNA catalogues 47 such names borne by around 370 individuals (PNA 2/II, 680–700), compared with 7 names and less than 10 name-bearers listed by Knut L. Tallqvist in his Neubabylonisches Namenbuch (Reference TallqvistTallqvist 1905, 99).

Names with the theophoric element written (d)aš-šur = Aššur are unambiguous. Note the potential confusion between the names IdAŠ–SUR = Aššur-ēṭir ‘Aššur has saved’ (Reference NielsenNielsen 2015, 42) and I/lúDIL–SUR = Ēdu-ēṭir ‘He has saved the only one’ (Reference NielsenNielsen 2015, 112), which are written with identical signs apart from the determinative(s); the latter occurs as a family name.

Ištar-of-Nineveh (Bēlet-Ninua)

The goddess Ištar-of-Nineveh, in the form Bēlet-Ninua (‘Lady of Nineveh’), occurs in Babylonian sources as an element of the family name Šangû-(Bēlet-)Ninua:

‒ PN1 A-šú šá PN2 A lúSANGA-dGAŠAN-ni-nú-a (Nbn. 231:3–4, 14–15)

‒ PN1 A-šú šá PN2 A lúSANGA-ni-nú-a (VS 3 49:18–19)

In her study of Nineveh after 612, Stephanie Dalley points to these two Neo-Babylonian texts as evidence for the continuation of Nineveh after its fall in 612 BCE (Reference DalleyDalley 1993, 137). These instances allegedly involve a man who is called ‘son of the priest of the Lady of Nineveh’. However, this reflects a misunderstanding of the Neo-Babylonian convention for representing genealogy: the man in question is actually a member of the family called ‘Priest-of-Bēlet-Ninua’ (Šangû-Bēlet-Ninua), a clear parallel to other Neo-Babylonian family names of the form Šangû-DN, ‘Priest of DN’. It is uncertain exactly when the cult of Ištar-of-Nineveh was introduced into Babylonia; however, the goddess’s temple in Babylon is already mentioned in the topographical series Tintir which was likely compiled in the twelfth century BCE (Reference GeorgeGeorge 1992, 7). Thus, while there is no way of knowing when the eponymous ancestor entered Babylonia (assuming he, like the cult itself, came from Assyria), this family name cannot be taken as evidence for the continuation of the city of Nineveh after 612 BCE.

The question has been raised as to whether the toponym that forms part of the divine name Bēlet-Ninua is actually Nineveh or a local place, Nina (reading ni-ná-a instead of ni-nú-a) in Babylonia (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 10). However, there are reasons to suppose that this family name does actually refer to the Assyrian goddess Ištar-of-Nineveh. First, the name of Bēlet-Ninua’s temple in Babylon, Egišḫurankia, is the same as that of her temple in Assur, according to Andrew R. George, who understands Ninua in the divine name to represent Nineveh and not Nina (Reference GeorgeGeorge 1993, 95, nos. 409 and 410). Second, her temple in Babylon is mentioned in an inscription of Esarhaddon (RINAP 4 48 r. 92–3), and it seems most unlikely that this would refer to the goddess of a very minor Babylonian settlement.

Eššu

In his study of Assyrians in Babylonia, Ran Zadok cites a number of names with the theophoric element Eššu (written -eš-šu/šú and -dáš-šú), including Ardi(/Urdi?)-Aššu and Ardi(/Urdi?)-Eššu, Dalīli-Eššu, Dān-Eššu, Gubbanu(?)-Eššu, Kiṣir-Eššu, Sinqa-Eššu, Tuqnu-Eššu and Tuqūnu-Eššu, Ubār-Eššu, and Urdu-Eššu (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 9). However, it should be noted that Eššu names do not feature prominently in the extant Neo-Assyrian onomasticon: only a single such name, Šumma-Eššu, is recorded (PNA 3/II, 1286 s.v. ‘Šumma-Ēši or Šumma-Eššu’). On the other hand, some of the Eššu names listed above have predicates that are typically Assyrian rather than Babylonian, namely Kiṣir-, Sinqa-, Tuqnu-/Tuqūnu-, and Urdu- (see later in chapter). This suggests an Assyrian background for these particular names, even though they are not yet attested in Assyrian sources.

We then have to confront the question of how to interpret the theophoric element Eššu. According to Ran Zadok, Eššu is ‘probably the same element as ˀš which is contained in names appearing in Aramaic dockets … and an Aramaic tablet … from the NA period’ (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 9). These Aramaic dockets with ˀš feature on tablets which give the personal name also in Assyrian cuneiform, and in all instances where it is preserved the divine element is written d15, to be read Issar. For example, the names of the sellers of a house, Upāqa-ana-Arbail ‘I am attentive to Arbaˀil’ (Ipa-qa-a-na-arba-ìl) and Šār-Issar ‘Spirit of Issar’ (IIM-15), feature in an Aramaic caption on the edge of tablet SAA 14 47:15´–16´, dated in 617* BCE: pqnˀrbˀl / srˀš.Footnote 5 If the association between Eššu and Aramaic ˀš(r) is correct, we are dealing with a variant of the divine name Ištar. This is compatible with the elements Kiṣir-, Sinqa-, Tuqūnu- and Urdu- listed earlier, which are all attested in Neo-Assyrian sources in names formed with Issar.

In PNA the name Šumma-Eššu (written Išum-ma–eš-šú) was translated ‘Truly Eši! [= Isis]’ and interpreted as ‘Akk. with Egypt. DN’ (Luukko, PNA 3/II, 1286). Although this is the only instance of an Eššu name in PNA, a number of other names of supposed Egyptian derivation are listed that contain the element Ēši/Ēšu, understood as ‘Isis’, namely: Abši-Ešu (Iab-ši-e-šu), Dān-Ešu (Ida-né-e-šu), Ēšâ (Ie-ša-a), Eša-rṭeše (Ie-šar-ṭe-e-[še]), and Ḫur-ši-Ēšu (Iḫur-si-e-šú, Iḫur-si-ie-e-šú, Iḫur-še-še, Iḫur-še-šu). However, given that in Babylonian sources the element Eššu is written with -šš- and is particularly associated with typical Neo-Assyrian predicates, as noted earlier, it seems that regardless of whether Eššu is associated with Aramaic ˀš (= Issar), it should be kept separate from the Egyptian element Ēši/Ēšu, which is written with -š- and does not occur with those predicates.

Names Formed with Assyrian Toponyms

In addition to the names discussed here which contain Assyrian divine elements, there are a number of occurrences in Babylonian sources of personal names formed with Assyrian toponyms, notably Arbaˀil (modern Erbil): Arbailāiu ‘The one from Arbaˀil’ and Mannu-(a)kî-Arbail ‘Who is like Arbaˀil?’ (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 8–9; Reference Zadok1985, 28). The feminine name fUrbil-ḫammu ‘Arbaˀil is the master’ (fur-bi-il-ḫa-am-mu), borne by a slave, can be added to these (Reference ZadokZadok 1998). The family name Aššurāya ‘Assyrian’ (Iaš-šur-a-a), based on the city name Assur, is also attested. Since none of the members of this family bore Assyrian names, Ran Zadok suggests that the family’s ancestor migrated to Babylonia before the Neo-Babylonian period (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 2). As I noted already, the Assyrians did not use family names, so the adoption of Aššurāya as a family name must reflect the ‘Babylonianisation’ of the descendants. Related to this phenomenon is the presence of Assyrian toponyms in Babylonian sources, such as Aššurītu, written uruáš-šur-ri-tú (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 3); there is no telling when such toponyms were originally introduced into Babylonia.

Names with Assyrian Dialectal Forms

Examples in this category include names formed with the Assyrian precative -lāmur ‘may I see’ (Bab. -lūmur), and nouns in Assyrian dialectal form, such as urdu ‘servant’ (Bab. ardu). The Assyrian D-stem imperative -balliṭ ‘keep alive!’ (Bab. -bulliṭ) comprises another potentially distinctive form, though I know of no example of the name type DN-balliṭ attested in Babylonian sources to date. Examples of names with Assyrian dialectal forms include:

Pāni-Aššur-lāmur ‘May I see the face of Aššur’ (IIGI–AN.ŠÁR–la-mur; Reference BeaulieuBeaulieu 1997, 59–60). The use of Neo-Assyrian dialect was not always consistent since IIGI–AN.ŠÁR–lu-mur is also attested (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 6). In UCP 9/2 57 the name is written with both -lāmur (l. 8) and -lūmur (l. 4) (Reference BeaulieuBeaulieu 1997, 59).

Pāni-Bēl-lāmur ‘May I see the face of Bēl’ (Ipa-ni–dEN–la-mur; Reference BeaulieuBeaulieu 1997, 59–60).

Urdu-Eššu ‘Servant of Eššu’ (Iur-du-eš-šú, Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 2). The common use of the logogram ÌR often makes it impossible to tell whether a name includes urdu or ardu.

In addition, the Neo-Assyrian onomasticon – unlike the Neo-Babylonian – includes names formed with the imperative of riābu ‘to replace’ (Rīb(i)-DN) as well as with the preterite (Erība-DN), though note that logographic writings with ISU- as first element are ambiguous. A number of elements particular to Assyrian occur only with Assyrian divine names, according to Ran Zadok: ‘It is worth pointing out that the exclusively Assyrian forms urdu “slave”, rīb (Bab. erība), bēssunu (Bab. bēlšunu) and iššiya (reflecting NA issiya) “with me”; Bab. ittiya) are recorded in N/LB only as the predicates of -eššu and dŠÁR names’ (Reference ZadokZadok 1984, 4–5).

Names Formed with Vocabulary Characteristic of the Assyrian Onomasticon

In discussing the divine name Eššu, I identified a number of Assyrian names formed with characteristic vocabulary items, namely (with translations following PNA): Kiṣir-DN (‘Cohort of DN’), Mannu-(a)kî-DN (‘Who is like DN?’), Sinqi-DN (‘Test of DN’), Tuqūn-DN (‘Order of DN’), Tuqūnu-ēreš (‘He [a deity] has desired order’), and Tuqūnu-lāmur (‘Let me see order!’). To these we can add Unzaraḫ-[…] (Iun-za-ra-aḫ-[…]; Reference ZadokZadok 1998); compare the names Unzarḫu (‘Freedman’?), Unzarḫu-Aššur, and Unzarḫu-Issar (PNA 3/II, 1387–8).

Orthography and Phonology

In the writing of Assyrian names in Neo-Assyrian sources, the divine determinative is often omitted, whereas in Neo-Babylonian this is only rarely the case. In Babylonian the divine name Ea is rather consistently written dé-a, whereas in Assyrian it is often written (d)a-a and, more rarely, ia, rendered Aia (Parpola in PNA 1/I, xxv–xxvii). Note that Aia is not to be confused with the goddess Aya ((d)a-a), spouse of the sun god Šamaš. Otherwise, in terms of phonology, the main difference between the writing of Assyrian and Babylonian names lies in the treatment of the sibilants. We have already seen how the Assyrian divine element Issar (Ištar) was rendered Iššar in Babylonian. The sibilant š in Babylonian names may be rendered s in Neo-Assyrian: for example, the common Neo-Babylonian name Šumāya was sometimes rendered Sumāya, written Isu-ma-a-a and Isu-ma-ia in Neo-Assyrian sources (PNA 3/I, 1157–8). This tendency of Assyrian scribes to ‘Assyrianise’ Babylonian names may hinder the identification of Babylonians in the Assyrian sources. The same is true of the converse: if a Babylonian scribe were to render an Assyrian name by, for example, changing -lāmur to -lūmur, then there would be no way of identifying the individual as Assyrian in the absence of an Assyrian theophoric element or of further corroborating evidence.

Introduction

The Aramaic onomasticon found in Babylonian sources linguistically belongs to the West Semitic languages while it is written in cuneiform script used to express Late Babylonian Akkadian, an East Semitic language (see Figure 8.1). Among the languages classified as West Semitic, four are recognisable in the Late Babylonian onomasticon: Arabic names, generally viewed as representing the Central Semitic branch; Phoenician; Hebrew (or Canaanite); and Aramaic names representing its Northwest Semitic subgroup.Footnote 1

Figure 8.1 A family tree model of Semitic languages.

Aramaic names make up the largest part of the West Semitic onomasticon in the Neo- and Late Babylonian documentation. They will be the focus of this chapter. Chapter 9 deals with Hebrew names, Chapter 10 with Phoenician names, and Chapter 11 with Arabic names from this period. The Aramaic onomasticon of the preceding Neo-Assyrian era, which has been researched by Fales, is not included here.Footnote 2 A given name may be recognised as Aramaic on the basis of patterns and trends regarding patronym, the occurrence of an Aramaic deity, and the socio-economic context of the attestation. Despite the fact that these factors provide valuable background information (see section on ‘Aramaic Names in Babylonian Sources’), the most secure way of deciding on the Aramaic nature of a name is based on linguistic criteria:

- phonological: phonemes of Semitic roots are represented in a way specific for Aramaic;

- lexical: words are created from roots that solely appear in Aramaic;

- morphological: forms and patterns used are peculiar for Aramaic;

- structural: names are constructed with, for instance, Aramaic verbal components.Footnote 3

Opinions differ as regards the nature of the Aramaic language in Babylonia during the Neo-Babylonian era. Aramaic attestations from this timeframe are – together with those from the preceding Neo-Assyrian period – variously evaluated as belonging to Old Aramaic as found in sources from Aramaean city states, as manifestations of local and independent dialects, or as (precursors of) Achaemenid Imperial (or Official) Aramaic.Footnote 4

Defining the variety of Aramaic used in Babylonia is hindered by the fact that direct evidence from this area is generally scarce and textual witnesses from its state administration, which presumably was bilingual Akkadian–Aramaic, are non-extant. Aramaic texts mainly appear as brief epigraphs written on cuneiform clay tablets.Footnote 5 Moreover, a small number of alphabetic texts were impressed into bricks by those working on royal buildings in Babylon.Footnote 6

Chronologically, the major part of the Aramaic onomasticon appears in cuneiform texts dating to the latter half of the fifth century – a period in which the use of Aramaic as chancellery language of the Achaemenid Empire seems to have been established in all parts of its vast territory. Achaemenid Imperial Aramaic is attested in a large variety of literary genres across socio-economic domains and is written in alphabetic script on various media, such as papyri, ostraca, funerary stones, and coins.Footnote 7 Overall, the orthography of this language variety is marked by consistency (especially in administrative letters), its syntax displays influences from Persian and Akkadian, and its lexicon contains an abundance of loanwords from various languages.Footnote 8

Aramaic Names in Babylonian Sources

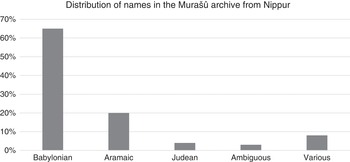

Aramaic names can be found in cuneiform economic documents from all over Babylonia, but they appear most frequently in texts from the villages Yāhūdu, Našar, and Bīt-Abī-râm, dating to the sixth and early fifth centuries,Footnote 9 and in the extensive Murašû archive originating from the southern town of Nippur and its surroundings, which covers the second half of the fifth century.Footnote 10 By contrast, the proportion of West Semitic names in city-based cuneiform archives is relatively marginal: about 2 per cent of the c. 50,000 individuals appearing in this text corpus bear an Aramaic name if the Murašû documentation is disregarded; this amounts to 2.5 per cent if the latter archive is included.Footnote 11 The proportion of Aramaic names in the Murašû archive is ten times higher than the norm (see Figure 8.2).Footnote 12

One of the reasons behind the marked difference in the proportion of non-Babylonian names between the rural archives and the Babylonian sources in general is the fact that the former are characterised by less formative influence – and thus representation – of Babylonian elites, who formed a relatively homogenous social group. They lived in the city; were directly or indirectly connected to its institutions, most notably the temples; and virtually always bore Babylonian personal names, patronyms, and family names (see Chapter 1).Footnote 13 Unsurprisingly, they appear as protagonists in the urban documentation, while individuals with non-Babylonian names tend to have the passive role of witnesses.Footnote 14

Onomastic diversity thus correlates with a decidedly rural setting. This is underlined by the fact that Murašû documents not written up in Nippur, but in settlements located in its vicinity, display larger proportions of both parties and witnesses with non-Babylonian names.Footnote 15 Likewise, texts from the rural settlements of Yāhūdu, Našar, and Bīt-Abī-râm contain a substantive amount of West Semitic names. Indeed, the multilingual situation in Babylonia’s south-central (or possibly south-eastern) region, whence these two cuneiform corpora originate,Footnote 16 already stood out during earlier centuries. Letters in the archive of Nippur’s ‘governor’ written between c. 755 and 732 BCE attest to the connections between powerful leaders of Aramaean tribes and feature many Aramaic-named individuals, as well as Aramaisms.Footnote 17 Moreover, a letter dated to king Assurbanipal’s reign (seventh century BCE) mentions speakers of multiple different languages living in the Nippur area (roughly indicated by the brackets in Figure 8.3).Footnote 18

Figure 8.3 Nippur and its hinterland.

Various forms of migration contributed to the multi-ethnic character of the population in this region. First, non-Babylonian sections – among which were Aramaean groups – migrated into the territory east of the Tigris (the area indicated by the arrows in Figure 8.3).Footnote 19 Second, the diverse populace was a result of forced migration. For instance, the Babylonian king Nabopolassar (626–605 BCE) took many prisoners of war – most of them Aramaeans – from settlements in upper Mesopotamia and the middle Euphrates region and relocated them to the Nippur area in 616 BCE. Not long before, Nippur itself had been an Assyrian town where a garrison was stationed; it was only besieged and conquered between 623 and 621 BCE. Campaigns led by subsequent kings, most notably Nebuchadnezzar II (604–562 BCE), resulted in deportations of communities from Syria and the Levant and their resettlement in the same region around Nippur.Footnote 20 The state provided the deportees with fields and in return levied taxes and/or rents and conscripted the landholders as troops. The process is documented in its early stages in the cuneiform texts from Yāhūdu and its environs. Also, the Murašû archive depicts individuals active in this so-called land-for-service system.Footnote 21 Due to these migratory flows, not only the onomasticon is diverse: many toponyms in this region are non-Akkadian or Akkadian – West Semitic hybrids as well. They may refer to Aramaean tribes, eponymous forefathers, or places of origins in Syria or the Levant.Footnote 22 Finally, Aramaic epigraphs are quite well-attested in these archives.

During the Achaemenid period, the southern region functioned as a passageway between the Persian heartland and the Empire’s western provinces. Through the Kabaru Canal the Babylonian waterways were directly connected with Susa, the Persian capital in Elam. Except for thus being of geopolitical importance, this area hosted travellers from Babylonia and far beyond who began the last stage of their trip to the capital here, upon changing boats in the settlement of Bāb-Nār-Kabari.Footnote 23

Spelling and Normalisation

The normalisation of West Semitic names written in Babylonian Akkadian, for which no academic standard has been formulated, is challenging. First, it is not always straightforward whether a name is Akkadian or Aramaic; for instance, Iba-ni-a can be read as Akkadian Bānia and as West Semitic Banī, a hypocoristic form of the sentence name ‘DN-established’. Second, there are many ways to approach the transcription of Aramaic names, based on the question of whether an attempt should be made to reconstruct the characteristics of an Aramaic name and, if so, to what extent. This could pertain to relatively straightforward issues, such as phonemes not represented in Akkadian (for instance, the gutturals) or those rendered differently (for instance, /w/ written /m/, as visible in the Judean theophoric element Yāma). However, it also relates to features such as vowel quality, vowel length, and stress, which are often not easy – or are downright impossible – to reconstruct due to incongruity of the writing systems and the inconsistency in which Aramaic names are converted into Akkadian.Footnote 24 Therefore, taking the Akkadian spelling as a point of departure and including only the most basic features rendered by it in a relatively consistent manner is my preferred modus operandi for transcription.

At the same time, some degree of harmonisation is necessary as, for instance, the spelling of the perfect in the Aramaic name DN-natan shows: IDN-na-tan-nu/-ni/-na (the final CV-sign merely indicates that the previous syllable is stressed). Abstraction on the basis of the Aramaic verbal form avoids a plethora of names that are in fact orthographic varieties. Moreover, although vowel length is not included in transcription when uncertain, a frequent and clear trend is taken into account: as the final long vowel of the perfect 3.sg. m. of verbs ending in ˀ/y/h is nearly always represented, the transcription of, for example, IDN-ba-na-ˀ is DN-banā. These examples demonstrate that there will always be a margin of error and that a hybrid transcription is inevitable – something that does not seem unfitting in view of the sources.Footnote 25

Typology of Aramaic Names

The Theophoric Element

Besides the general theophoric element, this section deals with specific Aramaean deities. When these occur with Akkadian complements, the names are viewed as hybrids; in order to qualify as an Aramaic name, the linguistic criterion is decisive.

ˀl and ˀlh

The most frequently attested theophoric element is ˀl (ˀil) ‘god’. In cuneiform script, this element is written DINGIR, the logogram and determinative for the Babylonian word ilu ‘god’, which also has the phonetic value an.Footnote 26 It is broadly acknowledged that the (plural) logogram DINGIR.MEŠ is employed for the same purpose in the Late Babylonian period.Footnote 27 In other words, a name like Barik-il ‘God’s blessed one’ can be rendered Iba-ri(k)-ki-DINGIR as well as Iba-ri(k)-ki-DINGIR.MEŠ. Similarly, Raḫim-il ‘God’s loved one’ is spelled both Ira-ḫi-im-DINGIR and Ira-ḫi-im-DINGIR.MEŠ. The same orthographic variation applies to the element ˀl in the name of the deity Bīt-il: for example, Bīt-il-ḫanna ‘Bīt-il is gracious’ (IÉ-DINGIR-ḫa-an-na) and Bīt-il-adar ‘Bīt-il has helped’ (IÉ-DINGIR.MEŠ-a-dar-ri).Footnote 28

The element ˀlh (ˀilah) is less frequently attested. Examples are Abī-ilah and Ilah-abī ‘God is my father’ (IAD-ìl-a and Iìl-a-AD).Footnote 29 It tends to appear as final component, followed by possessive suffix 1.sg. -ī, for example, in the names Mannu-kî-ilaḫī ‘Who is like my god?’ (Iman-nu-ki-i-i-la-ḫi-ˀ) and Abī-ilaḫī ‘My father is my god’ (IAD-la-ḫi-ˀ; IAD-i-la-ḫi-ˀ).Footnote 30

Aramaean Deities

A common theophoric element in Aramaic names is Addu or Adad, the storm god, written dad-du and dIŠKUR respectively:Footnote 31 Addu-rapā ‘Addu has healed’ (Idad-du-ra-pa-ˀ), Adad-natan ‘Adad has given’ (IdIŠKUR-na-tan-nu). Despite being a Mesopotamian god, the epicentre of Adad’s veneration remained northern Syria. Here, he took the primary place among the Aramaean deities. The fact that Adad has a strong familial association with the deities Apladda and Būr is visible in father – son pairings Būr-Adad or Adad-Būr in the corpus from Yāhūdu, Našar, and surrounding settlements.Footnote 32 Adgi, a West Semitic form of Adad, is attested with an Aramaic predicate in the Murašû archive.Footnote 33

Tammeš, whose Akkadian equivalent is Šamaš, is attested with a wide variety of Aramaic complements, especially in Nippur, one of which is Zaraḫ-Tammeš ‘Tammeš has shone’ (Iza-ra-aḫ-dtam-meš). Although various phonetic cuneiform spellings are employed to render the initial West Semitic consonant /s/, dtam-meš is the most current orthography in Neo- and Late Babylonian sources.Footnote 34

The name of the moon god Iltehr (based on ˀil and *sahr) is akin to Akkadian Sîn. This is visible in tablets from the village of Neirab, a settlement of deportees originating from the like-named ‘centre of the moon’ cult in Syria.Footnote 35 In those tablets, we find the name of the same person Iltehr-idrī ‘Iltehr is my help’ spelled both Idše-e-ri-id-ri-ˀ and Id30-er-id-ri-ˀ. However, typically Iltehr is written dil-te-(eḫ-)ri in cuneiform texts.Footnote 36

Another Aramaean deity from the heavenly realm is ˁAttar (ˁttr), with cognates in a range of Semitic languages. In Akkadian this is Ištar, which has the variant form Iltar:Footnote 37 Attar-ramât ‘Attar is exalted’ (Idat-tar-ra-mat), Iltar-gadā ‘Iltar is a fortune’ (Iìl-ta-ri-ga-da-ˀ). The Neo-Assyrian sources show that the consonantal cluster -lt- often shifted to -ss-, which was pronounced -šš-. Although these examples show that this shift did not carry through consistently in Babylonia, it may be visible in the name Iššar-tarībi ‘Iššar replaced’.Footnote 38

Amurru is a popular theophoric element in Aramaic names from the sixth and fifth centuries, although the deity had a low status in the Mesopotamian pantheon. From the late third until the middle of the second millennium it was used as a device by Sumerians and Babylonians to identify Amorites whose distinct linguistic and cultural presence was becoming more prominent. As the Amorites started to assimilate, the need of othering disappeared and groups of West Semitic origins adopted Amurru in name-giving practice as a way to self-identify.Footnote 39 Amurru being the most frequent West Semitic theophoric element in the onomasticon from Našar and neighbouring villages is a manifestation of this trend.Footnote 40 Also attested in these villages is the deity Bīt-il, who was venerated in an area close to Judah and whose name-bearers may have been deported simultaneously.Footnote 41

Other West Semitic deities that appear with Aramaic complements are Našuh or Nusku (for instance, in the Neirab documentation),Footnote 42 Qōs,Footnote 43 Rammān,Footnote 44 and Šēˀ.Footnote 45 Šamê, ‘Heaven’, also appears with various Aramaic complements.Footnote 46 Attestations of the Aramaean deity ˁAttā are scarce and ambiguous. It may be linked to ˁAnat in a similar way as Nabê is connected with Nabû and Sē with Sîn.Footnote 47

Verbal Sentence Names

Most frequent is the sentence name that has a perfect verbal form, also referred to as the suffix conjugation, as its predicate. The subject, which is a theophoric element, often appears as initial component. Generally, the verbal forms are in the G-stem. Some examples are Nabû-zabad ‘Nabû has given’ (IdAG-za-bad-du), Sîn-banā ‘Sîn has established’ (Id30-ba-na-ˀ), Aqab-il ‘God has protected’ (Ia-qab-bi-DINGIR.MEŠ), and Yadā-il ‘God has known’ (Iia-da-ˀ-ìl).Footnote 48

Names in which a deity is addressed by means of a perfect 2.sg. m. (indicated by the suffix -tā) are specific for the Late Babylonian period. They are followed by the object suffix 1.sg. (-nī): Dalatānī ‘You have saved me’ (Ida-la-ta-ni-ˀ), Ḫannatānī ‘You have favoured me’ (Iḫa-an-na-ta-ni-ˀ).

Other predicates have the form of an imperfect, which is also referred to as the prefix conjugation:Footnote 49 Addu-yatin ‘May Adad give’ (Idad-du-ia-at-tin), Idā-Nabû ‘May Nabû know’ (Iid-da-ḫu-dAG), Aḫu-lakun ‘May the brother be firm’ (IŠEŠ-la-kun), Tammeš-linṭar ‘May Tammeš guard’ (Idtam-meš-li-in-ṭár).Footnote 50

Finally, verbal sentence names can contain an imperative: Adad-šikinī ‘Adad, watch over me!’ (IdIŠKUR-ši-ki-in-ni-ˀ), Nabû-dilinī ‘Nabû, save me!’ (IdAG-di-li-in-ni-ˀ).

Sentence names that consist of three elements sporadically occur. They are influenced by Akkadian fashion and even may incorporate an Akkadian element. An example hereof is the first element of the following name, which contains an Aramaic predicate with a G-stem imperfect 2.sg. m.:Footnote 51 Ša-Nabû-taqum ‘(By help?) of Nabû you will rise’ (Išá-dAG-ta-qu-um-mu).

Nominal Sentence Names

In nominal sentence names the subject generally takes the initial position. The object is often followed by the possessive suffix 1.sg. -ī; sometimes 2.sg. -ka:Footnote 52 Abu-lētī ‘The father is my strength’ (IAD-li-ti-ˀ), Abī-ilaḫī ‘My father is my god’ (IAD-i-la-ḫi-ˀ),Footnote 53 Tammeš-ilka ‘Tammeš is your god’ (Idtam-meš-ìl-ka), Nanāya-dūrī ‘Nanāya is my bulwark’ (Idna-na-a-du-ri-ˀ),Footnote 54 Iltehr-naqī ‘Iltehr is pure’ (Idil-te-eḫ-ri-na-aq-qí-ˀ), and Nusku-rapē ‘Nusku is a healer’ (IdPA.KU-ra-pi-e).

Sentence names that form a question are of nominal nature as well. They either start out with the interrogative pronoun ˁayya ‘where?’ or with man ‘who?’Footnote 55: Aya-abū ‘Where is his father?’ (Ia-a-bu-ú), Mannu-kî-ḫāl ‘Who is like the maternal uncle?’ (Iman-nu-ki-i-ḫa-la).

Compound Names

This type of name consists of two nominal components in a genitive construction. Nominal components can be regular nouns, kinship terms, deities, or passive participles:Footnote 56 Abdi-Iššar ‘Servant of Iššar’ (Iab-du-diš-šar), Aḫi-abū ‘His father’s brother’ (IŠEŠ-a-bu-ú), and Barik-Bēl ‘Bēl’s blessed one’ (Iba-ri-ki-dEN).

Hypocoristica

The hypocoristic suffix -ā, written -ˀ or -h in Aramaic and -Ca-a/ˀ in Akkadian, is added to most nominal sentence names and compound names. It may be like the Aramaic definite article that is of similar form and is suffixed to nouns as well. Hypocoristic -ā became so popular during the first millennium BCE that it replaced other hypocoristic suffixes common during the previous millennium. Moreover, it started to be attached to Arabian and Akkadian names as well.Footnote 57 Aramaic examples – with a translation of their nominal bases – are: Abdā ‘Servant’ (Iab-da-ˀ), fBissā ‘Cat’ (fbi-is-sa-a), Ḫarimā ‘Consecrated’ (Iḫa-ri-im-ma-ˀ), Zabudā ‘Given’ (Iza-bu-da-a), and Iltar-gadā (Iltar + fortune; Iil-tar-ga-da-ˀ).

Hypocoristic names with suffix -ī tend to be Aramaic. It may be based on the gentilic or suffix 1.sg. and is written -y in Aramaic, which is rendered -Ci-i/ia/iá or -Ci(-ˀ) in Akkadian:Footnote 58 Abnī ‘Stone’ (Iab-ni-i), Namarī ‘Leopard’ (Ina-ma-ri-ˀ), Raḫimī ‘Beloved’ (Ira-ḫi-mì-i), and Barikī ‘Blessed’ (Iba-ri-ki-ia). Its phonological variant is -ē.

One of the hypocoristic suffixes partly replaced by -ā is -ān, written -Ca-an(-nu/ni), -Ca-(a-)nu/ni:Footnote 59 Nabān ‘Nabû’ (Ina-ba-an-nu), Binān ‘Son’ (Ibi-na-nu).

A great deal of variety is achieved by adding combinations of two of these suffixes to nominal formations.Footnote 60

One-Word Names

Nearly all names that consist of one word are affixed with a hypocoristic marker. Exceptions are attested in various formations, which often are hard to distinguish due to inconsistent Babylonian spelling.Footnote 61

Naming Practices

As regards naming practice, it is striking that Babylonian theophoric elements appearing in the Aramaic onomasticon are not the ones prominent in contemporaneous Babylonian names. For instance, hardly any Aramaic names in the Murašû documentation contain the theophoric element Enlil, while this Babylonian deity enjoyed immense popularity in the Nippur area at the time.Footnote 62 This also is the case for Enlil’s son Ninurta (attested only once) and for Marduk, Nergal, and Sîn. Babylonian gods that are found in greater numbers in Aramaic names are Nabû, who takes second position after Tammeš in Nippur’s Aramaic onomasticon, as well as Bēl and Nanāya. Interestingly, Nabû primarily appears in patronyms, which indicates a decline of his prevalence.Footnote 63

In feminine names, a tendency of different order stands out. Although suffixes -t, -at, -īt, and -ī/ē are attested, there seems to have been a strong preference for feminine names ending in -ā:Footnote 64 fBarukā ‘Blessed’ (fba-ru-ka-ˀ), fGubbā ‘Cistern’ (fgu-ub-ba-a), fḪannā ‘Gracious’ (fḫa-an-na-a), fNasikat ‘Chieftess’ (fna-si-ka-tu4), fDidīt ‘Favourite’ (fdi-di-ti), and fḪinnī ‘Gracious’ (fḫi-in-ni-ia).

Tools for Identifying Aramaic Names in Cuneiform Sources

Various Aramaic verbs have surfaced in the examples. A more extensive – although not exhaustive – overview of verbs commonly attested in Aramaic names is presented in Table 8.1.

| Regular verbs | Irregular verbs | |

|---|---|---|

| brk – to bless | ˀmr – to say | ngh – to shine |

| gbr – to be strong | ˀty – to come | nṭr – to guard |

| zbd – to give, grant | bny – to build, create | nsˀ – to raise |

| zbn – to redeem | brˀ – to create | nṣb – to place |

| zrḥ – to shine | gˀy – to be exalted | ntn – to give |

| sgb – to be exalted | gbh – to be exalted | ˁny – to answer |

| smk – to support, sustain | ḥwr – to see | pdy – to ransom, redeem |

| srḥ – to be known | ḥzy – to see | ṣwḥ – to shout |

| ˁdr – to help, support | ḥnn – to be gracious, favour | qwm – to rise |

| ˁqb – to protect | ḥṣy – to seek refuge | qny – to get, create, build |

| rḥm – to love, have mercy | ybb – to weep | rwm – to be high |

| rkš – to bind, harness, tie up | ydˁ – to know | rˁy – to be pleased, content |

| šlḥ – to send | yhb – to give | rpˀ – to heal |

| šlm – to be well | ypˁ – to be brilliant | šly – to be tranquil |

| šmˁ – to hear | yqr – to be esteemed | šˁl – to ask |

| tmk – to support | mny – to count | šry – to release |

Nouns that regularly appear in nominal sentence names are presented in Table 8.2.Footnote 65

Nouns that typically appear in compound names are given in Table 8.3.

Table 8.3 Nouns attested in Aramaic compound names from the Neo- and Late Babylonian periods

| *ˀab | father | ˀb |

| *ˀaḥ | brother | ˀḥ |

| *ˀamat | female servant | ˀmt |

| *bVr | son | br |

| *bitt | daughter | brt |

| *gē/īr | patron, client | gr |

| *naˁr | servant, young man | nˁr |

| *ˁabd | servant | ˁbd |

The outline of elements of which Aramaic names may consist (presented in the section ‘Typology of Aramaic Names’) and these tables may give a taste of what such names could look like. If one suspects a name to be Aramaic, either the indices of Reference ZadokRan Zadok (1977, 339–81) may be checked, or Reference Zadok, Stökl and WaerzeggersZadok 2014, which includes attestations from later publications as well (the latter in a searchable PDF). As names have not been transcribed, use the Akkadian spelling for a search.

Introduction to the Language and Its Background

Historical and Ethno-Linguistic Background

Following Nabopolassar’s and Nebuchadnezzar II’s western campaigns, major Levantine cities – Jerusalem, Tyre, and Ashkelon, among others – surrendered to Babylonia’s sovereignty. The Babylonian kings forcibly took rebellious local rulers and citizens in exile to Babylonia. As a result, a significant number of Hebrew and other (North)west Semitic anthroponyms and toponyms start to appear in the Babylonian records of the long sixth century, as well as a small number of Philistine names.

There is some evidence for the presence of a Judean person (or was he Israelite?) in Babylonia already in the late seventh century BCE, before Nebuchadnezzar II’s deportations. The man’s name is rendered Igir-re-e-ma in cuneiform, which Reference ZadokRan Zadok (1979, 8, 34) identifies as a Yahwistic name containing the West Semitic noun gīr and therefore meaning ‘Client of Y’, but Tero Alstola raises some problems with such an identification (Reference Alstola2020, 230, n. 1164). There are no other attestations of Yahwistic names in Babylonian records from pre-exilic times.

Not all bearers of Yahwistic or Hebrew names in Babylonia necessarily arrived from Judah with Jehoiachin in 597 BCE or with the great deportations of 587 BCE. Some may have come from Israel, either directly in the late eighth century BCE, or via Assyria after the fall of the Neo-Assyrian Empire a century later. Indeed, in principle at least, it is possible that the Assyrians deported some people from the territory of the former kingdom of Israel to Babylonia (732–701 BCE). Moreover, there is indirect evidence that descendants of Israelite deportees, who had settled in Assyria (especially in the Lower Ḫabur area), migrated from there to Babylonia after the collapse of the Neo-Assyrian Empire. The above-mentioned Gīr-Yāma as well as the members of the family of Yašeˁ-Yāma (Iia-še-ˀ-ia-a-ma, Isaiah), who lived in Sippar (531/0 BCE), were probably such migrating Israelites (Reference Zadok, Gabbay and SecundaZadok 2014, 110–11).

The Babylonian exile marks a watershed in the linguistic history of Hebrew. By the tenth century BCE, two Hebrew-speaking states flourished in the central hill country of Palestine: Israel to the north, in the Samarian hills and portions of central Transjordan and Galilee, and Judah to the south, in the Judean hills, with its capital at Jerusalem. Hebrew spoken in the north significantly differed from that in the south. The Israelites deported by the Assyrians spoke the former, whereas the Judeans deported by the Babylonians spoke the latter. The southern form of Hebrew constitutes the classical phase of the language and is primarily represented by Standard Biblical Hebrew and numerous inscriptions from Judah. In the Hebrew of post-exilic Judah (sixth–second centuries BCE), represented by later biblical literature, we find numerous linguistic features, prototypes of Rabbinic Hebrew, that are entirely absent from the earlier literature. Thus, beneath the surface of pre-Rabbinical Hebrew, for which the Bible is our major source, a remarkable plurality of linguistic traditions extends over some 800 years. It is important to bear this in mind when interpreting cuneiform Hebrew names in the light of Biblical Hebrew and onomastics.

Basic Characteristics of Hebrew Names

It may be argued that a name that is linguistically Hebrew or includes a Yahwistic theophoric element should be classified as a ‘Hebrew name’. Footnote 1 The bulk of Hebrew names in the cuneiform corpus are Yahwistic names.

Applying the aforementioned definition of ‘Hebrew’ to the foreign onomasticon of Babylonia is easier said than done. If Hebrew names are stricto sensu names with nominal or verbal elements that reflect Hebrew grammar or lexicon, Hawšiˁ ‘He saved’ from Nippur would have a typical Hebrew name (//MT Hôšēaˁ הוֹשֵׁעַ). In view of the Hiphil-formation it is linguistically Hebrew rather than Aramaic, which has Aphel-formations (hence, ˀwšˁ and ˀwšˁyh at Elephantine). Moreover, ‘the root Y-Š-ˁ is foreign to Aramaic’ (Reference Muraoka and PortenMuraoka and Porten 1998, 20–1; cf. 113–16). However, the name could also be borne by any of the other Canaanite-speaking population groups and is, for instance, attested among the Transjordan Ammonites (hwšˁl, Reference Al-QananwehAl-Qananweh 2004, 71). Consequently, the major problem that confronts anyone interested in detecting linguistically Hebrew names in the cuneiform corpus of first millennium BCE Babylonia is to distinguish them from Aramaic, Phoenician, and Transjordan equivalents.

Yahwistic names in Babylonian cuneiform sources (i.e., names with the theophoric element YHWH), are Hebrew in the theological sense of the word, ‘seeing that no other ethnic group in pre-Hellenistic Mesopotamia worshiped Yhw’ apart from those originating from Judah (Reference Zadok, Gabbay and SecundaZadok 2014, 111–12).

Besides linguistically and theologically Hebrew names, Šabbātay and Ḥaggay can be classified as ‘culturally’ Hebrew. They refer to religious practices characteristic of the (Biblical) Judean community, such as the observance of Sabbath and religious feasts. The problem is that they were not exclusively borne by Judean exiles or their descendants in Babylonia, and Ḥaggay is also attested among, for instance, Ammonites and Phoenicians (Reference Al-QananwehAl-Qananweh 2004, 73–4; Reference AlstolaAlstola 2020, 56–7). Therefore, when the individuals bearing these names had blood relatives with Yahwistic names, their Judean background is probable and the name may be classified as ‘(culturally) Hebrew’. Otherwise, one has to investigate their circle of acquaintances as well as the archive and overall socio-economic context in which they appear for connections with Judah or Judeans before labelling their name ‘Hebrew’.

Some non-Yahwistic anthroponyms in the cuneiform corpus have parallels in the Bible, but this does not guarantee that they are Hebrew stricto sensu. At the most, such a name hints at the bearer’s Judean descent. Famous biblical figures such as Abraham, Jacob, Benjamin, Menahem, Ezra, and Menashe bore non-Yahwistic names that are, linguistically speaking, not just Hebrew but West Semitic in general. Often parallels exist already in Ugaritic, Amorite, and/or Canaanite-Amarna onomastics from the second millennium BCE. The names listed above, all attested in Babylonian sources from the first millennium BCE, are excluded from this chapter on linguistic grounds, even when advanced prosopographic research established a Judean background for the individuals behind them.

Overall, having a Yahwistic or linguistically Hebrew name or patronym in the Babylonia of the long sixth century BCE signifies Judean (exceptionally, Israelite) descent, but the reverse is not necessarily true. Ethnic Judeans in Babylonia gave their children not only Yahwistic/Hebrew names, but also West Semitic/Aramaic and even Babylonian/Akkadian and Iranian names.

Applied Writing Systems of Hebrew in Cuneiform

Sketch of the Problem

The complicated process of detecting and decoding foreign names in the Babylonian sources, and subsequently encoding them into English, can be illustrated by the name spelled Ia-mu-še-eḫ in a tablet from the Murašû archive (EE 113). He is the father of Mattan-Yāma (Ima-tan-ia-a-ma) ‘Gift of Y’ and, since the latter has a clear Hebrew–Yahwistic compound name, it is likely that we may find his name to be Hebrew as well. This assumption is further corroborated by the fact that he occurs in the company of other men with Yahwistic names, such as Yāḫû-zabad (Idia-a-ḫu-u-za-bad-du) ‘Y has granted’ and Yāḫû-laqīm (Idia-a-ḫu-ú-la-qí-im) ‘Y shall raise’ in an archive that is known for its many Yahwistic names.

In order to crack the cuneiform spelling Ia-mu-še-eḫ, we have to consider certain features related to the cuneiform writing system. First, there is the Neo-/Late Babylonian convention to write w as m. Second, there is the established Babylonian practice to render the West Semitic consonants h and ˁ, for which the cuneiform syllabary did not have a specific sign, with ḫ-signs or leave them unmarked. Finally, there is the problem of rendering diphthongs in cuneiform script and the avoidance of final consonant clusters. Considering all these points, Ia-mu-še-eḫ can be analysed as a cuneiform writing for the Hebrew name Hawšiˁ ‘He saved’.

Converting this information in an acceptable English (Latin-script) form is a difficult balancing act, for which see section on ‘Spelling and Normalisation’.

Cuneiform Orthographies of YHWH

The man who owed barley to the Babylonian Murašû family, according to a cuneiform tablet excavated at Nippur (EE 86), is called Idia-a-ḫu-u-na-tan-nu (Yāḫû-natan) ‘Y has given’. On the tablet’s right edge his name recurs, but this time it is written in alphabetic script as yhwntn. Similarly, the debtor’s name in CUSAS 28 10 from Yāhūdu is spelled Išá-lam-mi-ía-a-ma (Šalam-Yāma) ‘Y completed/is well-being’ in cuneiform and šlmyh in alphabetic script on the same tablet. These and other alphabetic spellings reveal that dia-a-ḫu-u- and -iá-a-ma are cuneiform renderings of the Yahwistic theophoric element.

Actually, the divine name is spelled in numerous ways by the Babylonian scribes ‘who probably wrote what they heard’ (Reference Millard and KhanMillard 2013, 841) and were not restricted by orthographic traditions. It appears in different forms depending on whether it is the first or the last component of the anthroponym.Footnote 2 Alphabetic and cuneiform spellings do not necessarily correspond, and their relation to the actual pronunciation(s) of the divine name remains an open question.

The superscripted d preceding the Yahwistic element in some cases is a modern convention for transcribing the DINGIR sign which Babylonian scribes used to indicate that what follows is the name of a deity. When writing the names of their own gods, such as Marduk or Nabû, they rigorously included it, but for foreign gods they had a more compromising attitude. Therefore, when actually used, it highlights the scribe’s awareness and recognition of the divine nature of YHWH. When absent, it may imply different things – such as, for instance, his ignorance, his denial, or his carelessness. Nebuchadnezzar’s scribes at Babylon c. 591 BCE did not use the DINGIR sign, but their colleagues at Nippur and Yāhūdu at around the same time did (583 and 572 BCE).Footnote 3 It shows that the latter ‘were aware of the divine nature of Yhw at the very beginning of their encounter with the exiles’ (Reference Zadok, Gabbay and SecundaZadok 2014, 111, n. 18). Whether this awareness grew or declined over time, and how far it was influenced by geographical and demographic factors, needs further study.

Characteristics and Limitations of the Cuneiform Writing System

Cuneiform scribes were not required to be consistent in spelling, and the cuneiform script allowed many variations. Despite that, orthographic conventions and historic spellings reduced the scribes’ choices, in particular in writing anthroponyms. They used traditionally fixed logograms to write divine names and recurrent name elements. Predicates such as iddin ‘he gave’, aplu ‘firstborn son’, and zēru ‘offspring’ were more often spelled with logograms (respectively MU, A or IBILA, and NUMUN) than syllabically (i.e., in the way they were pronounced).

Logograms do not show in Hebrew names (and only rarely in West Semitic ones). A few exceptions confirm this rule. Some Babylonian scribes recognised Hebrew kinship terms leading to the use of ŠEŠ and AD for Hebrew ˀaḥ ‘brother’ and ˀab ‘father’ (EE 98:13; PBS 2/1 185:2). In addition, we have one instance each of the logogram DÙ for the Hebrew verb root B-N-Y ‘to create’ (CUSAS 28 37:12) and perhaps also of the logogram MU for Hebrew N-T-N ‘to give’ (Reference Zadok, Gabbay and SecundaZadok 2014, 123).

The cuneiform scribes’ relative consistency when writing Babylonian names contrasts with the high orthographic variation of foreign names. To give an idea, Reference Pearce and WunschLaurie E. Pearce and Cornelia Wunsch (2014, 27) count twelve different writings of the name Rapaˀ-Yāma ‘Y healed’ in the Yāhūdu corpus alone. Some are insignificant for linguistic analysis; for instance, the variation among homophonous signs (ú/u, ia/ía, etc.). In other cases, they may hint at contrasting linguistic relations: Iba-ra-ku-ia-a-ma ‘Y has blessed’ (Barak-Yāma; Hebrew G qatal-perf.) vs. Iba-ri-ki-ia-a-ma ‘Blessed by Y’ (Barīk-Yāma; Aramaic passive participle); Išá-lam-ia-a-ma ‘Y is well-being’ (Šalam-Yāma; Hebrew G qatal-perf.) vs. Išá-lim-ma-a-ma ‘Kept well by Y’ (Šalīm-Yāma; Aramaic passive participle) vs. Iši-li-im-iá-a-ma ‘Y made recompense’ (Šillim-Yāma; Hebrew D qittil-perf.).

Related to the matter under consideration is the degree of the scribes’ phonemic awareness. Were they able to hear and identify the specific Hebrew phonemes and sounds, such as the peculiar West Semitic ś (שֹ) in Maˁśēh-Yāma ‘Y’s work’? Does their occasional rendering with lt (e.g., Ima-al-te-e-ma) suggest they heard a fricative-lateral pronunciation of the phoneme (Reference ZadokZadok 2015a; cf. Reference ZadokZadok 2002, 31 no. 38; Reference Zadok, Gabbay and Secunda2014, 116)? Did they hear the ayin (ˁ) in the names ˁAzar-Yāma (initial) ‘Y helped’ and Šamaˁ-Yāma (internal) ‘Y heard’, the aleph (ˀ) in ˀAṣīl-Yāma (initial) ‘Noble is Y’, the heh (h) in Hawšiˁ (initial) ‘He saved’ and in Yāhû (internal), or the diphthong in some of the names just cited? Did they hear a difference between the k in Kīn-Yāma ‘True is Y’ and its fricative allophone (ḵ) in Yəhôyākîn – assuming that the spirantisation of at least some of the bgdkpt had already started in the Hebrew of the sixth century BCE?

Even if they understood the names or at least heard them correctly, the scribes were not always able to document them properly with the tools at their disposal. Which cuneiform sign or combination of signs could they use to write down, for instance, the Hebrew gutturals?

Ran Zadok extensively dealt with these problems in 1977, in the appendix to his monumental book On West Semites in Babylonia (pp. 243–64), and again in 1988, in the course of his research on The Pre-Hellenistic Israelite Anthroponomy (cf. Reference Millard and KhanMillard 2013, 844). With the publication of the documents from Yāhūdu in 2014 the pool of (Yahwistic) Hebrew names significantly increased, but the rules laid down by him are still in force and only minor additions are in place (Reference ZadokZadok 2015a).

As enhancement to Ran Zadok’s findings, we include here a table (Table 9.1) that visualises the conventional cuneiform renderings of the West Semitic (incl. Hebrew) gutturals in first millennium BCE names from Babylonia. It is based on his data, but differentiates between zero- and vowel-spellings, in view of writings such as Iaq-bi-ia-a-ma (zero) vs. Ia-qa-bi-a-ma (vowel) for the initial ayin in ˁAq(a)b-Yāma ‘Protection is Y/Y protected’. Illustrations from esp. Yahwistic names are provided, except for Amurru-šamaˁ (common West Semitic).

Table 9.1 Cuneiform renderings of the Hebrew gutturals

| Initial | Internal | Final | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ayin | ḫ | Iḫu-uz-za-a = ˁUzzāya | Išá-ma-ḫu-ia-a-ma = Šamaˁ-Yāma | Ia-mu-še-eḫ = Hawšiˁ |

| ˀ | - |

| IdKUR.GAL-šá-ma-ˀ = Amurru-šamaˁ | |

| V | Ia-za-ra-ia-a-ma = ˁAzar-Yāma |

|

| |

| Ø | Iaz-za-ra-ia-a-ma = ˁAzar-Yāma |

| - | |

| g | Ipa-ra-gu-šú = Parˁōš ‘Flea’ (< Parġōš) | |||

| aleph | V |

| Ira-ap-pa-a-a-ma = Rapaˀ-Yāma | - |

| Ø | Iur-mil-ku = ˀŪr-Milk(i) |

| - | |

| ˀ | - | Ira-pa-ˀ-ia-a-ma = Rapaˀ-Yāma | Ira-pa-ˀ | |

| ḥeth | Generally ḫ | |||

| heh | ḫ | Iḫu-ú-na-tanan-na = <Yā>ḫû-natan |

| - |

| ˀ | - |

| - | |

| Ø |

| Iia-a-ḫi-in-nu = Yāḫ<û>-ḥīn | - | |

| k | - |

| - | |

It may happen that the zero and multiple spellings for Hebrew gutturals, long vowels, and consonant clusters leave the modern scholar with more than one choice. In principle, Iḫi-il(-lu)-mu-tu, for which no exact biblical parallel exists, derives from the verb roots Ġ-L-M (> ˁ-L-M) ‘to be young’ (cf. biblical toponym ˁAlemet עָלֶמֶת, Reference ZadokZadok 1988, 67) or Ḥ-L-M (cf. the biblical name Ḥēlem חֵלֶם ‘Strength’, Reference ZadokZadok 1979, 31; Reference Zadok1988, 116). More examples are adduced elsewhere in the chapter (e.g., qatl/qitl-nouns vs. G perf.; and ḥiriq compaginis vs. 1.sg. genitive suffix).

Babylonisation of Hebrew Names

Babylonian scribes occasionally reinterpreted Yahwistic names through re-segmentation of name components, assonance, inter-language homophony, and metathesis. Reference Pearce and WunschLaurie E. Pearce and Cornelia Wunsch (2014, 28, 42–3, 61, 66) notice four occurrences in the Yāhūdu corpus which they analyse in detail. In all these examples, a fine line distinguishes between Judeans reshaping their names to recognisable Babylonian forms (perhaps even with the specific aim of obliterating their Judean identity) and Babylonian scribes nativising foreign names to approximate Akkadian names.

Spelling and Normalisation

Encoding Hebrew names, transmitted in cuneiform script, in Latin script is a difficult balancing act. Some scholars avoid the problem by simply citing the names in their original cuneiform spelling. Otherwise, the choices range from normalisations that are faithful to the cuneiform form (Amušeḫ) to those that are based on historical-linguistic reconstructions (Hawšiˁ) or inspired by biblical parallels with its Tiberian vocalisation (Hôšēˁa הוֹשֵׁעַ); conventional English renderings thereof (Hosea) are acceptable only for popularising publications. In any case, conversion rules for Hebrew and Aramaic names should be the same because they share the same linguistic features. Consistency is desirable, but probably not always attainable.

Particularly complex is transcribing the divine name, as we do not know its original Hebrew articulation and the cuneiform transcriptions are many and confusing. As a result, in the scholarly literature, we find Yāma, Yāw, Yāḫû, among others. In this contribution, I use Y as an abbreviation of the Hebrew divine name in English translations, adopting a neutral stance on this complex issue.

The Name Material in Babylonian Sources

Text Corpora and Statistics

Babylonian sources with Hebrew names are chiefly administrative and legal documents from the sixth and fifth centuries BCE that can be connected to three main types of archives (royal, private, and temple). Most Hebrew names are recorded in the first two types. Very few occur in Babylonian temple archives. A couple appear in documents whose archival context cannot be established. The archival classification provides us with valuable information on the name-bearers’ socio-economic or legal background. Remarkably, Hebrew names are absent from the Neo-Babylonian corpus of historiographic texts. There are also virtually no Hebrew names in the published corpora of administrative and private letters (except perhaps for fBuqāšu in Reference Hackl, Jursa and SchmidlHackl et al. 2014 no. 216).

Four corpora of cuneiform administrative and legal texts stand out, described in much detail by Reference AlstolaTero Alstola (2020, chps 2–5), including bibliographic references to editions and secondary literature. In chronological order, these are:

(1) The royal archives from Babylon, excavated in Nebuchadnezzar’s palace, primarily consisting of ration lists (archive N1). They refer to the Judean king Jehoiachin and his entourage in 591 BCE.

(2) A group of six cuneiform documents, originating from Rassam’s excavations at Abu Habbah (ancient Sippar), that pertain to the descendants of Ariḥ, a family of Judean royal merchants in Sippar in the years 546–493 BCE.

(3) The corpus of c. 200 documents, acquired on the antiquities market, that were drafted at various villages in the rural area south(-east) of Nippur over a period of 95 years, from 572 to 477 BCE. The main villages are Yāhūdu, Našar, and Bīt-Abī-râm.

(4) The private archive of the Babylonian Murašû family found in situ in Nippur. It consists of c. 730 documents dated to the second half of the fifth century BCE (452–413 BCE). Drafted in Nippur-city or in villages in the nearby countryside, they record the business activities of the descendants of Murašû, in the course of which they encountered men of Judean descent, many bearing Yahwistic/Hebrew names. The Murašû archive ‘constitutes the last significant corpus of cuneiform evidence on Judeans in Babylonia. Only a single text survives from the fourth century BCE’ (Reference AlstolaAlstola 2020, 222).

The information that we can draw from these sources is dictated by their archival and archaeological origin (or lack thereof). They were written by and chiefly for the Babylonian members of the urban elite. The only exception seems to be the documents from the environs of Yāhūdu. Here, Judeans do not just appear against the backdrop of other people’s transactions or as an object, but they are the leading characters, leasing land, paying taxes, etc. Even so, they are still presented by indigenous Babylonian scribes who, by recording their foreign names and activities, may have served the royal administration more than the Judeans. Anyway, no sources written by the Judean deportees themselves or their descendants survive. A complicating factor, furthermore, is the incomplete publication of some of the sources, and the scribes’ limited knowledge of Hebrew grammar and culture.

Among the c. 2,500 names in the Murašû archive from Nippur in central Babylonia, Ran Zadok identified seventy Hebrew names (of which thirty-six are Yahwistic): less than 3 per cent. He suspects ‘that this may be just an accident of documentation and it does not necessarily mean that the largest concentration of Judeans in Babylonia was in the Nippur region’ (Reference ZadokZadok 2002, 63).

In and around Yāhūdu, approximately 159 individuals with Yahwistic/Hebrew names can be identified among the roughly 1,000 individuals recorded in c. 200 documents. This means that about 15 per cent of all names there are Yahwistic, with the largest concentration of them occurring in the town of Yāhūdu itself (c. 35 per cent). Variations in counting occur among scholars, but the overall picture remains the same (cf. Reference Pearce, Stökl and WaerzeggersPearce 2015, 20).

Only a handful of Hebrew names are recorded in Uruk and its region, while none are mentioned in Ur, so that one may conclude that ‘very few Judeans resided in southern Babylonia, despite the rich Babylonian documentation from there’ (e.g., the vast Eanna temple archive from Uruk) (Reference Zadok, Gabbay and SecundaZadok 2014, 113; Reference Jursa and ZadokJursa and Zadok 2020, 21, 28–31).

Judeans with Yahwistic/Hebrew names or patronyms also dwelt in the capital and in most of the major cities of northern Babylonia (Sippar, Borsippa, Opis, and Kish). The evidence comes primarily from the royal administration in Babylon and the mercantile community in Sippar. Hebrew names are, however, virtually absent from the private archives of the urbanite North Babylonians and the temple archive of Sippar. For example, among the 1,035 individuals that can be identified in the Nappāḫu family archive from Babylon none bore West Semitic names in general, or Hebrew names in particular. Similarly, only one Hebrew name pops up among the 1,130 individuals in the Egibi family archive, and Hebrew names are rare in the vast Borsippean family archives. No more than eight Yahwistic names occur in the thousands of documents from Sippar’s temple.

Typology of Names

Ran Zadok has written extensively on the West Semitic name typology, and the reader is referred to his studies for details (especially Reference ZadokZadok 1977, 78–170 and Reference ZadokZadok 1988, 21–169). The following sections present a summary of those formations that are relevant for the study of the cuneiform Yahwistic names and the linguistically Hebrew profane names. The examples are illustrative, not exhaustive.

Yahwistic Verbal Sentence Names

Most cuneiform Yahwistic names are verbal sentences, with the name components predominantly put in the order predicate–subject, and without an object (cf. biblical Yahwistic names).

The verbal predicates display the following characteristics: (1) They are always in the G-stem, except the Hiphil in Hawšiˁ ‘He saved’, and a few disputable cases;Footnote 4 (2) Perfect (qtl) is the norm, with only a few predicates in the imperfect (yqtl; e.g., Yigdal-Yāma ‘Y will be(come) great’, Išrib-Yāma ‘Y will propagate’), imperative (e.g., Qī-lā-Yāma ‘Hope for Y!’ < Q-W-Y),Footnote 5 active participle (e.g., Yāḫû-rām ‘Y is exalted’, Nāṭi-Yāma ‘Y bends down’), and passive participle (e.g., Ḥanūn-Yāma ‘Favoured by Y’); (3) The predicate is always in the 3.sg. (except for those in the imperative), and without object suffixes or other extensions, a few exceptions notwithstanding.Footnote 6

Yahwistic Nominal Sentence Names and Genitive Compound Names

In the Yahwistic nominal sentence names the predicate–subject sequence prevails. The predicates are all nouns, except for the adjective in ˀAṣīl-Yāma ‘Noble is Y’. An adjective is also present in Iṭu-ub-ia-ma if understood as Ṭōb-Yāma ‘Good is Y’ (rather than Ṭūb-Yāma ‘Goodness is Y’).

The distinction between qatl and qitl forms is not always clear, partly because qatl could become qitl because of the attenuation a > i, already in Biblical Hebrew names, especially after ayin or near liquids and nasals (e.g., ˁazr > ˁizr, malk > milk). Moreover, the cuneiform scribes may not always have been aware of, or careful enough about, these differences. They may also have heard variant pronunciations for the same name from different speakers.

Further noteworthy is the wavering between segholite (CVCC) and bisyllabic (CVCVC, anaptyctic?) spellings – as, for instance, in the orthographies of Ṣid(i)q-Yāma ‘Justice is Y’. Thus we have a qitl spelling (CVCC) in Iṣi-id-qí-iá-a-ma along with qitil spellings (CVCVC) in Iṣi-di-iq-a-ma and Iṣi-di-qí-ia-a-ma. As a result, it is hard to determine whether the bisyllabic spellings in the following names reflect verbal (G qatal-perf.) or nominal (qatl) predicates: Mal(a)k-Yāma ‘Y rules/The king is Y’, ˁAz(a)z-Yāma ‘Y is strong/Strength is Y’, ˁAq(a)b-Yāma ‘Y protected/Protection is Y’, ˁAt(a)l-Yāma ‘Y is pre-eminent/The prince is Y’, Šal(a)m-Yāma ‘Y completed/Peace is Y’, and Yāḫû-ˁaz(a)r ‘Y helped/Help is Y’.

Uncertainty arises about the exact relationship between the elements in names such as Ṣid(i)q-Yāma: genitive ‘Y’s justice’ or predicative ‘Y is justice’.

Finally, the choice between a ḥiriq compaginis or 1.sg. possessive pronoun cannot be sufficiently determined on the basis of the cuneiform orthographies. For instance, the spellings Iṣi-di-qí-ia-a-ma and Iṣi-id-qí-iá-a-ma do not reveal whether we have Ṣidqi-Yāma ‘Justice is Y’ or Ṣidqī-Yāma ‘My justice is Y’.

Yahwistic Interrogative Sentence Names

Under this category falls the name Mī-kā-Yāma ‘Who is like Y?’.

Yahwistic Names With a Prepositional Phrase

The name Bâd-Yāma (Iba-da-ia-a-ma) ‘In the hand/care of Y’ in a text from the Murašû archive belongs here, and perhaps also Iqí(-il)-la-a-ma, Idi-ḫu-ú-li-ia, and Iia-a-ḫu-lu-nu/ni, if they indeed reflect Hebrew lā ‘for’, respectively, lî ‘for me’ and lānû ‘for us’ (CUSAS 28 77, 90; Reference ZadokZadok 1979, 18–19).

Abbreviated Yahwistic Names

Included in this category are one-element names in which the divine name is shortened by means of suffixes (hypocoristica). Reference Pearce and WunschLaurie E. Pearce and Cornelia Wunsch (2014, 20) list the following abbreviated forms of the final Yahwistic elements: -Ca-a-a, -Ce-e-ia-a-ˀ, -Ci-ia-a-ˀ, Ci-ia/ía, -Cu-ia, -ia-[a]-ˀ, and -ia-a-ˀ. However, not all names ending in, for instance, -Ci-ia/ía or -Ca-a-a in cuneiform texts are abbreviated Yahwistic names. These endings are common hypocoristic endings in Babylonian and West Semitic onomastics. Accordingly, names such as Iḫa-an-na-ni-ía, Ipa-la-ṭa-a-a, and Izab-di-ia are not abbreviated Yahwistic names, unless additional (con)textual data confirm this.

A clear example is that of Ḥanannī ‘He has been merciful to me’, whose father bore the Iranian name Udarnā. We would not consider him a worshipper of YHWH in tablet BE 10 84 from the Murašû archive, where his name is spelled Iḫa-an-na-ni-ˀ, were it not for two other tablets from the same archive where his name is rendered with the theophoric element fully spelled Iḫa-na-ni/nu-ia-a-ma ‘Y has been merciful to me’ (BE 9 69; PBS 2/1 107). One of his brothers was called Zabdia (Izab-di-ia) ‘Gift’: did he have an abbreviated Yahwistic name – for example, Zabad-Yāma ‘Given by/Gift of Y’ (cf. PBS 2/1 208: Iza-bad-ia-a-ma) – or a plain West Semitic one derived from the root Z-B-D with a hypocoristic ending -ia? Similar illustrative cases of individuals bearing both a full Yahwistic name and a hypocoristic thereof derive from the Yāhūdu corpus: Banā-Yāma (Iba-na-a-ma) ‘Y created’, son of Nubāya, is also known as Bānia (Iba-ni-ia) ‘He created’; Nīr(ī)-Yāma (Ini-i-ri-ia-a-ma) ‘Y’s light/Y is (my) light’, son of ˀAḥīqar, as Nīrāya (Ini-ir-ra-a, Ini-ir-ra-a-a) ‘Light’; and Samak-Yāma (Isa-ma-ka-ˀ-a-ma) ‘Y supported’, father of Rēmūtu, as Samakāya (Isa-ma-ka-a-a) ‘He supported’.Footnote 7

Finally, the Yāhūdu and Murašû corpus attest names with an abbreviated form of the divine name in initial position: Iia-a-ḫi-in(-nu), Yāḫ<û>-ḥīn ‘Y is grace’ and Iḫu-ú-na-tanan-na, <Yā>ḫû-natan ‘Y has given’.

Non-Yahwistic Hebrew Names and Hypocoristica

The non-Yahwistic names are typically one element names with(out) hypocoristic suffixes, rarely two-element names. The hypocoristic endings are feminine -ā, adjectival -ān > -ōn, adjectival -ay(ya), and ancient suffixes -ā, -ī/ē, -ūt, or -ī+ā (= ia).

There are two categories depending on the predicate: names with an isolated verbal predicate and those based on nouns. fBarūkā ‘Blessed’, Hawšiˁ ‘He saved’, Ḥanan(nī) ‘He consoled (me)’, Yamūš ‘He feels/removes’ (Reference ZadokZadok 2015b), Natūn ‘Given’, Naḥūm (Ina-ḫu-um-mu) ‘Consoled’, Satūr ‘Hidden/Protected’, and ˁAqūb (Ia-qu-bu) ‘Protected’ belong to the first group. ˀAškōlā ‘Bunch of grapes’, Ḥaggay ‘(Born) on a feast’, Ḥannān(ī/ia) ‘Consolation’, Ḥillumūt ‘Strength’, Mattania ‘Gift’, Naḥḥūm (Ina-aḫ-ḫu-um) ‘Consolation’, ˁAqqūb (Iaq-qu-bu) ‘Protection’, Pal(a)ṭay ‘Refuge’, Parˁōš ‘Flea’, fPuˁullā ‘Achievement’, Šabbātay ‘(Born) on Sabbath’, Šamaˁōn ‘Sound’, and Šapān ‘(Rock) badger’ belong to the second group, but the line is sometimes hard to draw due to defective cuneiform orthographies: for example, Iši-li-im for Šil(l)im ‘He is (kept) well’ or Šillīm ‘Loan’. Yašūb-ṭill(ī) ‘(My) Dew will return’Footnote 8 and Yašūb-ṣidq(ī) ‘(My) Justice will return’ are extensions of the first group. For most of the above-listed names recorded Yahwistic compounds exist.