Introduction

The role of tactical ambiguity during protests

“What are they shouting about?” is a central question for students of contentious politics (McAdam et al. Reference McAdam, Tarrow and Tilly2001). But this question presupposes that protesters are in fact usually shouting about something, whether explicitly or not. Tilly (e.g. Reference Tilly2008: 63), in particular, has called on analysts to uncover the claims for justice that presumably express themselves through violent protests, against official narratives that often reduce the latter to apolitical “riots”. In the same line of thought, Scott (Reference Scott1990) introduced the concept of “hidden transcripts” to describe contentious claims that cannot be made in public for fear of retaliation, and suggested that these “transcripts” might be used as subtitles for nonspeaking forms of contention, such as grumbling and sabotage. Other authors have relied on post-hoc storytelling (Polletta Reference Polletta2006), local media framing (Snow et al. Reference Snow, Vliegenthart and Corrigall-Brown2007), and informal deliberations in backstage venues (Mische Reference Mische2008) to provide interpretive captions for protests with vague or underdefined agendas.

In this article, I propose a different approach to this problem. Instead of attempting to figure out what protesters really want, an equally important task is to understand why protesters will sometimes avoid making explicit political claims. The answer I develop is that there are tactical advantages to deferring the presentation of grievances, and that these advantages are particularly salient during high-risk contentious events. Instead of speaking their mind, protesters will be well-advised to engage in provocative actions that have no clear meaning. If they speak at all, protesters will benefit from remaining prudently vague as to what they ultimately want.

A concept is needed to capture this general principle. I shall call equivocal challenges those contentious performances that:

-

(1) avoid explicit claim-making,

-

(2) could be interpreted as supporting all sorts of claims,

-

(3) and consequently shift on authorities the responsibility of figuring out what protesters want.

The third point is key. In practice, the meaning of equivocal challenges will be defined by the official response they elicit. As they try to decide what protesters want from them, authorities will indirectly reveal what issues they are themselves willing to negotiate on (as pointed out by Markoff Reference Markoff2010: 600–6). Depending on the favorability of the official interpretation they receive, equivocal challenges may then be endorsed as having meant to convey the latter all along or walked back as never having had this intention. This move can thus alternatively serve as a steppingstone to, or offer plausible deniability for, the presentation of political claims.

Equivocal challenges should not be confused with has been diversely described as “multiple targeting” (Mische Reference Mische, Diani and McAdam2003), “polyvalent performances” (Tilly Reference Tilly2003), “multivocal discourse” (Steinberg Reference Steinberg1999), “polysemy” (Polletta Reference Polletta2006), or more colloquially as “dog-whistle politics” (Albertson Reference Albertson2015). All these terms refer to public discourses that make explicit political claims but obfuscate who they are ultimately addressed to. When a political orator uses this kind of discourse, the question is not what her words meant, but who she meant them for: is she really addressing everybody in the audience, or is she signaling specifically to members of a core constituency? What is uncertain in this case is the message’s intended target, not the message itself, including when the latter is full of euphemisms and circumlocutions, because the latter can be clarified by determining the identity of the target.

The hypothesis I defend, in contrast, is that there are circumstances in which it is better for protesters to hold off claim-making altogether. To be sure, there is no reason to assume that equivocating is always the best tactical move. But it seems reasonable to expect that equivocalness should be very acute in uncertain political contexts. Where collective mobilization faces objective danger, in particular due to the threat of governmental repression, there are obvious incentives to buying information on a claim’s chances of success before taking the risk of broadcasting it.Footnote 1

In this article, I provide detailed illustrative support for this hypothesis through a study of the 1948 Bogotazo, one of the deadliest and most destructive episodes of contentious mobilization in modern Latin American history. A case study is better suited to my purposes than a large catalog of contentious events. Because most catalogs are compiled from the official accounts that contentious events elicited (typically in the press or in parliamentary debates; see Tilly Reference Tilly2008: 13–27), their data reifies the struggle to interpret equivocal lines of action. As a result, most events become coded under just one of the multiple claims categories that they prompted (for instance, the meaning of a strike becomes locked down as being “about” wages, because it was ultimately resolved by promising protesters a raise). In contrast, I will exploit variations within my case study to gain greater analytic purchase on the logic of equivocal challenges. I will show, in particular, how protesters made it difficult for observers to understand what they wanted, and how different groups of powerful actors responded to the ambiguity of the situation.

The April 9 insurrection

In the second half of the 1940s Colombia was rapidly descending into a brutal civil conflict that would come to be known as La Violencia and would last approximately two decades (Sánchez Reference Sánchez Gómez1985; Roldán Reference Roldán2002; Gutiérrez Sanín Reference Gutiérrez Sanín2014). The Conservative party, having just returned to power in 1946 after more than 15 years in the opposition, presided over the violent removal of Liberals from public offices, and turned a blind eye to decentralized campaigns of collective killings targeting Liberal families in predominantly rural regions of the country. The Conservative party had only won the 1946 Presidency because the Liberal party had presented two candidates, and the Liberals had then won a majority of seats in the Legislative elections of 1947. Partisan competition for control of state institutions was consequently at an all-time high. At the same time, the surge in local clandestine violence was matched by a remarkable rise in political mobilization nationwide: general strikes, presidential speaking tours, party conventions, and other trans-locally coordinated events were drafting into public life more participants than ever before (see, in particular, Gutiérrez Sanín Reference Gutiérrez Sanín2017: 199–220; Palacios Reference Palacios2006: 139ss; and Archila Neira Reference Archila Neira1995). The situation on the eve of the Bogotazo was thus simultaneously one of escalating political risks and increased mobilization.

On April 9, 1948, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán—a rising populist figure who had become leader of the Liberal Party after a long internal struggle with the party’s old guard, which had cost Liberals the previous presidential election—was gunned down on Bogotá’s main street (the Carrera Séptima). News of his assassination sparked violent protests across the city. The Bogotazo, as it was immediately branded by the press, led to generalized looting and wreaked destruction on entire blocks of the city center. Civil unrest spilled over to other Colombian cities, was prolonged by a general strike, and was only quelled by a bloody military crackdown that made at least 549 victims in Bogotá alone.Footnote 2 These are the basic facts. But these facts are enmeshed in an interpretive conundrum.

The conundrum is that despite the availability of an obvious partisan motive—the assassination of a prominent Liberal—and a universal propensity on the part of contemporary observers to read partisanship into the chain of events leading up to it, the Bogotazo essentially eluded traditional partisan labels. The “crowd” of April 9 did not have leaders, explicit demands, or clear political colors. As H. Braun (Reference Braun1985: 203) puts it at the end of a masterful narrative reconstruction of the Bogotazo: “If ever there was a crowd that would substantiate the idea of the disorganized and normless character of violence, riots, and collective behavior, the crowd of the nueve de abril would seem to be the one.” The apparent apolitical character of the mobilization in Bogotá is all the more startling that the collective violence of the next two decades, in contrast, would opportunistically embrace national party labels to rebrand parochial conflicts (Roldán Reference Roldán2002).

In a laudable effort to push back against dismissive views that the Bogotazo was a mere “riot” ran by an irrational “mob” (Sánchez Gómez Reference Sánchez Gómez1984: 1; Braun Reference Braun1985: 4), historians have often been tempted to articulate grievances on behalf of the protesters, suggesting, inter alia, that the collective violence unleashed in Bogotá implicitly bemoaned socio-economic inequalities (Martz Reference Martz2012 [1962]), the soaring cost of life (Sharpless Reference Sharpless1978; Aprile-Gniset Reference Aprile-Gniset1983), the influence of American imperialism on politics and of international capitalism on the economy (Sánchez Gómez Reference Sánchez Gómez1984), the oligarchic pact between Conservative and Liberal elites (Medina Reference Medina1984), a highly exclusionary political order (Braun Reference Braun1985), the failure of Gaitanist populism (Pécaut Reference Pécaut1987; Henderson Reference Henderson2001), the power of the Conservative party and the Church (Arias Trujillo Reference Arias Trujillo1998), a manufacturing economy dominated by a putting-out system (Sowell Reference Sowell1998), or the city’s forced Haussmannization in previous years (Oelze Reference Oelze2017).

To be sure, all these interpretations ring true. They all point to contentious issues that had been publicly debated in previous years. Indeed, many of these debates had been recently rekindled by the upcoming Pan-American Conference of April 1948, which Bogotá was hosting. But despite this abundant reservoir of preexisting grievances, the fact is that Bogotans globally dispensed on April 9 with explicit claim-making. In this situation, the role of historical interpreters is not to offer themselves as spokespersons on behalf of the protesters, but to understand why nobody successfully took on that role then. To be sure, with Gaitán’s death, one of the most influential public voices of the time had been removed. Yet, given the influence of Gaitán’s powerful rhetoric on public life in preceding years (see Braun Reference Braun1985), it is surprising that the latter should not have played a greater part in shaping the response to his own death. Besides, there was no shortage in 1948 of talented political entrepreneurs peddling ready-made packages of contentious claims, which protesters could have reasonably adopted as their own. Yet none of these packages prevailed. Why not?

Solving this empirical puzzle requires, first, that we specify the scope of our case study. So far, I have spoken of the Bogotazo as if it were a single event. But this name is just a convenient shorthand for multiple sequences of events, which intersected on April 9 in the center of Bogotá. Five main sequences can be analytically disentangled, because they comprise distinct sets of actors, locations, and immediate outcomes: (1) Gaitán’s assassination on the Carrera Séptima, (2) the formation of two initial clusters of protesters, (3) the subsequent riots across the city center, (4) the seizure of radio stations by small groups of students and intellectuals, and (5) the political negotiations between Liberal and Conservative elites inside the Presidential Palace. The first three sequences correspond to actions taken by nonelite actors, while the last two represent the contrasted responses of intellectual and political elites. The first group of events can therefore help us explore the logic of equivocal challenges from the point of view of challengers, while the second group allows us to compare elite responses to the interpretive challenge of deciding what protesters wanted.

An examination of the first three sequences will reveal that, far from failing to articulate their grievances, Bogotans of all stripes generally succeeded in keeping these ambiguous, thereby putting increasing pressure on political elites to take a stand on the situation confronting them. Next, looking at sequences 4 and 5, I will compare how students and intellectuals, on the one hand, and Liberal and Conservative politicians, on the other, handled the challenges mounted by ordinary Bogotans. While the first group rushed to make public claims on behalf of the protesters, the second engaged in protracted negotiations behind closed doors. As a result, the former rapidly lost touch with the protesters, while the latter painstakingly reached an agreement that effectively defined the situation as one of civil disorder.

Sources of data

Historical studies of the Bogotazo have relied primarily on the profuse but unashamedly partisan secondary literature generated in the wake of the events (Aprile-Gniset Reference Aprile-Gniset1983; Sánchez Gómez Reference Sánchez Gómez1984; Braun Reference Braun1985). Besides the flurry of press articles produced in the days and weeks following April 9 by local Liberal and Conservative newspapers, a number of long-form accounts were hurriedly printed before the year 1948 was over (see Alape Reference Alape1983, 635–53 for an extensive survey). I generally eschewed these partisan sources, except as exemplars of the interpretive framings that were activated at the time by observers. But because these sources either impute conflicting motives to protesters (depending on the political line of the publication) or decry the absence of explicit grievances as proof of irrational popular violence, they cannot be used to explore a hypothesis about equivocal challenges.

Instead, I focus on sources that provide more direct data on connections between actors and on their repertoires of contention. In particular, I make extensive use of Alape’s (Reference Alape1983) massive sourcebook on the Bogotazo—a chronologically organized collection of materials (such as newspaper articles, radio broadcast transcripts, public speeches, and press photographs) that comprise almost everything that was publicly said or written about the Bogotazo as the latter was unfolding, interspersed with excerpts from first-person testimonies by protagonists. From this source, I extracted all first-person testimonies, including (1) signed judicial auditions, (2) selections from printed recollections, and (3) the interviews that Alape himself conducted, roughly three decades after the events, with 46 direct witnesses. I combined these testimonies with interviews conducted by the police as part of the judicial investigation (known as the Proceso Gaitán) into the assassination (143f). By combining the data extracted from Alape’s sourcebook with that of the Proceso Gaitán, I obtained information from 114 unique individuals. As each of these 114 individuals mentioned specific interactions with multiple others, I was able to extract detailed relational data on key social networks: the assassin’s, the cliques of bystanders at the scene of the crime, and the conversational networks between political elites.Footnote 3

Short of a verbatim transcript, I also tapped into this source to reconstruct the structure of the negotiations inside the Palace. I additionally checked Alape’s transcripts of contemporary radio broadcasts against recordings from the Radio Nacional for my analysis of the revolutionary juntas’ storytelling.Footnote 4 Finally, spatial data on targets of collective attacks were taken from Aprile-Gniset (Reference Aprile-Gniset1983), whose cartographical work combined observations from aerial photographs taken soon after the Bogotazo with a meticulous list established by a governmental commission in the following months. Reading the locations of destructed and looted buildings off Aprile-Gniset’s detailed maps, I converted the latter into a network of adjacent city blocks to investigate patterns of connections between targets.

Shirking interpretive responsibility

Sequence 1: the assassination

I begin with Gaitán’s assassination because it is a miniature of the interpretive ambiguities surrounding the Bogotazo more generally. Why did the assassin, a young working-class Bogotan named Juan Roa Sierra, go after the leader of the Liberal Party? His intentions were never disclosed: he left no manifesto, told no one of his plans, and refused to answer the questions of those who had captured him (see testimonies in Alape Reference Alape1983, 239–40). Contemporary commentators explained this mystery away by downgrading Roa to the ancillary role of “material author” of the assassination, and by tentatively assigning its “intellectual authorship” to one of the many political organizations that could have (in theory) benefited from Gaitán’s elimination.Footnote 5

Roa’s political associations were vague enough to suit virtually every conceivable conspiracy theory: his relatives described Roa to the police as an unattached client who had offered his services to both the Liberal Gaitán and the Conservative President Mariano Ospina Pérez; as an ardent Liberal who voted for Gaitán in 1946 but became disenchanted with the latter after he lost his bid to the presidency; as an occasional Nazi sympathizer (he had worked with his brother Luis at the German legation during World War Two); and as someone who just didn’t like to talk about politics.Footnote 6 In short, Roa had virtually as many political attitudes as he had people to discuss them with. The result was a “shroud of multiple identities” (to steal a phrase from Padgett and Ansell Reference Padgett and Ansell1993: 1310) which neither the people who knew him nor, later, the police and the press could cut through.

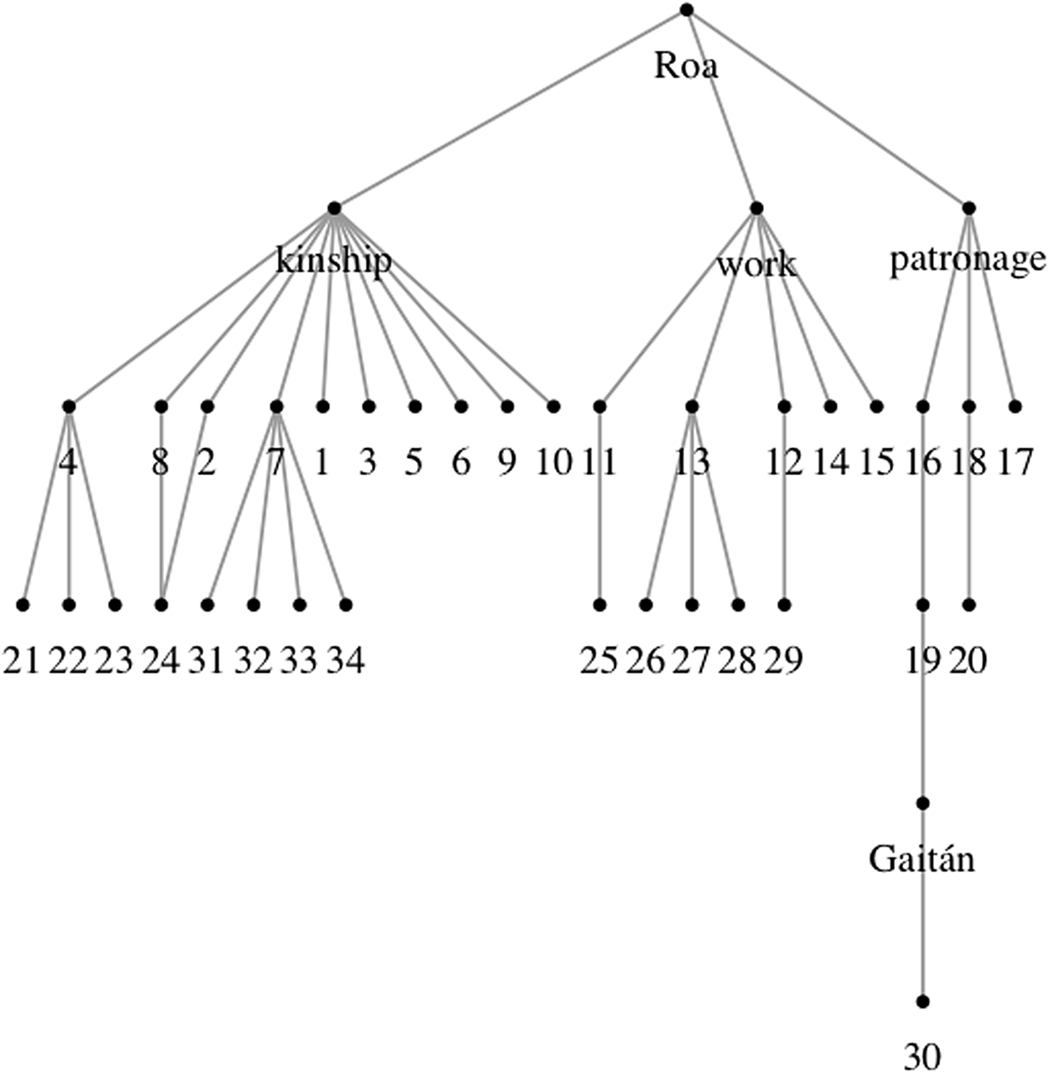

Instead of looking for hypothetical co-conspirators, we can reconstruct Roa’s concrete network of relations on the basis of testimonies gathered by the police after the crime (see Figure 1 ). This network presents, at first glance, an unremarkable sample of working-class sociability. Roa’s relations (both direct and indirect) came predominantly from kinship, work, and patronage (from local elites promising and occasionally delivering jobs, money, and other forms of material support, in exchange of loyalty). These three clusters, however, were poorly integrated, only connecting to one another through Roa himself.

Figure 1. The assassin’s social relations.

Remarkably, Roa pulled off a high-profile assassination by turning to his advantage this precarious network structure. Financing, hardware, biographical availability (i.e. freedom from relational constraints, McAdam Reference McAdam1986), and strategic access were all obtained through distant acquaintances, which Roa persuaded his connections to unblock under false pretenses (see Figure 2 )—a deliberate enrollment of weak ties to break out of the involuteness of stronger attachments (Granovetter Reference Granovetter1973).Footnote 7 Because each set of relations had a different perception of who Roa was and what his aspirations were or ought to be, but no means of checking this perception against information from other sets, they could easily be fed different stories by and about Roa without their suspicions being aroused. While these stories were globally incompatible, and could thus not yield a durable and consistent social status, they were individually plausible to each cluster of relations, and could therefore yield the latter’s limited cooperation.

Figure 2. Logistics of the assassination.

Admittedly, the foregoing analysis fails to present a motive in the juridical sense. It tells us how, not why, the assassination occurred. But it shows us that this particular how required the elision of an explicit why. For Roa, a practical condition for bringing together the different partitions of his network was to withhold explicit claims to a self-consistent personal identity. How Roa understood this constraint subjectively is both beyond empirical investigation and beside the point. For just what made the latter feasible also made it unintelligible, thereby effectively shifting the responsibility for determining what it meant onto the public that would witness its accomplishment.

Sequence 2: initial gatherings

As he attempted to flee the scene, the assassin was captured by two patrolling policemen. He was hurriedly taken to, and briefly sheltered inside, a drugstore across the street, before a group of men managed to wrench him out, and unceremoniously proceeded to lynch him. His lifeless body was then unclothed, dragged through the streets, and eventually exposed in front of the Presidential Palace (see Braun Reference Braun1985: 135–36). Meanwhile, only a few blocks away, another gathering was forming outside the clinic where a moribund Gaitán had been swiftly translated by his acolytes (see Figure 3 ).

Figure 3. Initial Gatherings (Downtown Bogotá).

Subsequent historical accounts have generally assumed that the “people” of Bogotá were staunchly devoted to Gaitán and that they spontaneously acted out their moral indignation at his death, first against the assassin, and then, unappeased, against the political rival who had beaten him in the 1946 presidential elections (e.g. Medina Reference Medina1984: 73; Braun Reference Braun1985: 135; Pécaut Reference Pécaut1987: 478). Yet this interpretation takes for granted just what needs to be investigated: that Bogotans possessed a ready-made collective identity—as the “people”—and that they were naturally predisposed to acting in concert in response to the assassination because it had obliterated the complementary identity of “leader of the people” (caudillo del pueblo). To be sure, Gaitán was a charismatic leader in the style of Perón and Vargas in Argentina and in Brazil, with a large following amplified by mass media and new repertoires of mobilization (see below). But lest we naturalize his charisma and the devotion of his followers, we need to treat both as emergent properties of a social relationship.Footnote 8

A gathering of individuals attending to the same object is a considerable social accomplishment (McPhail Reference McPhail2017). In practice, it requires decoupling participants from ongoing activities that make competing demands for their continued involvement. The Séptima, a busy commercial street, certainly provided a demographic baseline for mobilization. But this datum can be misleading. Braun (Reference Braun1985: 138, 157–58), following a familiar trope, speculates that the mass anonymity of the urban center facilitated the sudden shift from pacific routines to collective violence through a suspension of personal accountability. Yet, while the participants Braun interviewed claimed that they did not recognize familiar faces in the crowd, his own evidence suggests that most of them had in fact arrived to the Séptima as part of small groups of acquaintances. I conclude that while participants did not necessarily identify individuals in the crowd other than those they had come with, few of them were milling alone when Gaitán was shot.Footnote 9

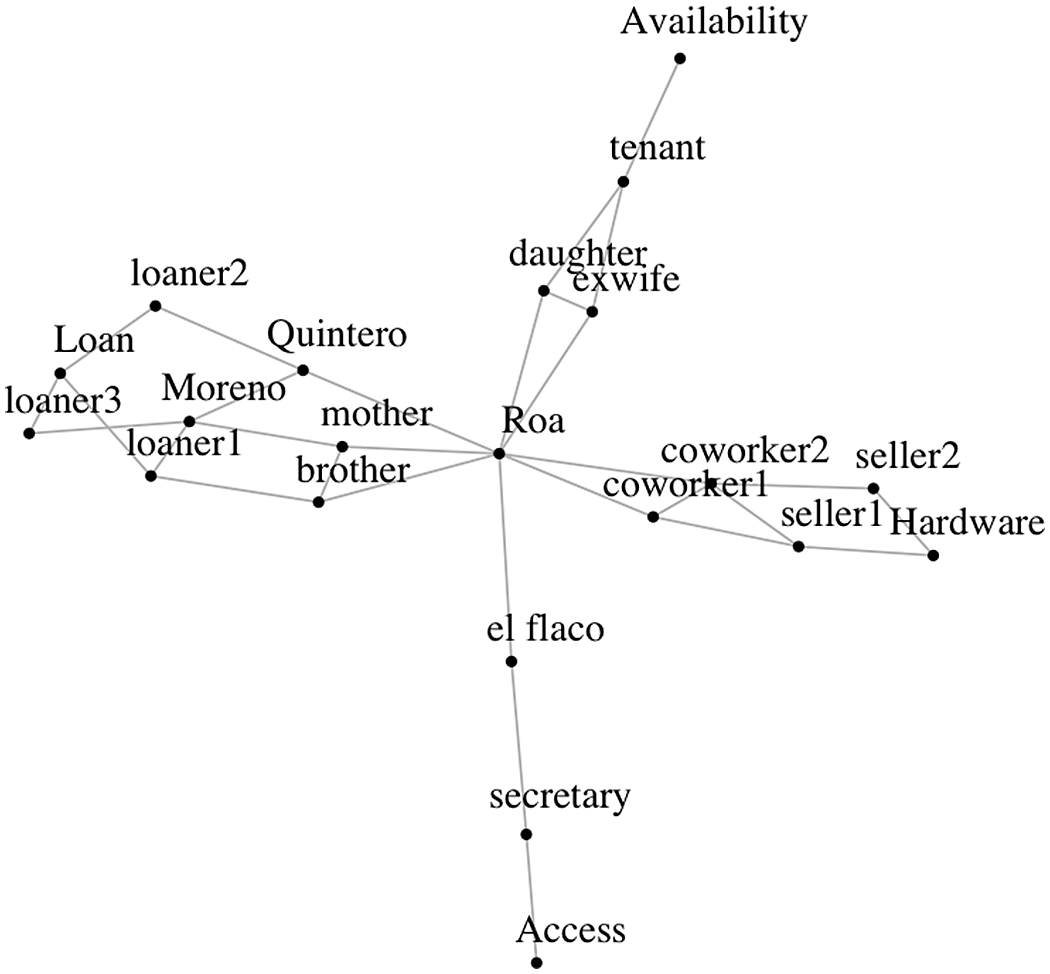

Even short of nominal recognition, participants easily identified one another and interacted according to conventional story-sets. We can parse four types of ties in our sample: kinship (connecting local residents to family members); friendship and friendly acquaintanceship (connecting patrons at cafés and restaurants to their friends’ and their friends’ friends); business (between customers and specialized services via storefronts with store names and uniformed employees); and civility (within and between social classes, membership to the latter being signaled by rigid styles of dress). Thus, rather than assembling free-floating individuals into a multitude homogeneously identifying as the “people”, the initial gatherings were produced by sampling from, and activating ties across, a congeries of local cliques (see Figure 4 ).

Figure 4. Communities among witnesses on the Séptima (Max modularity solution).

Further, while the idea of the “people” presupposes unanimity around a common focus, the first protesters were cleft in twain from the very start, precisely because none of them had direct access to Gaitán. On the one hand, a first group of bystanders detached itself when Gaitán was carried off for treatment, walking behind the taxi transporting him, and then staging a vigil outside the clinic where he had been taken. As they could not leave of their own accord without appearing to defect from their vigil, they repeatedly called out the Liberal leaders who had flocked to Gaitán’s side to come out and lead them to the Presidential Palace—a responsibility that Liberal leaders prudently shirked by staying inside. On the other hand, a second group had stayed behind and was pressing against the door of the drugstore where the assassin had been taken, eventually managing to flush him out. Once lynched, the latter became movable, and the lynching mob made itself mobile by the same token. They marched on the Presidential Palace.

Now, the decision to relocate outside the Presidential Palace rather than on the Plaza de Bolívar—the city’s largest public place and the traditional meeting point of all large political protests—is especially noteworthy, because it ostensibly went against habits of popular mobilization. Citizens of Bogotá possessed a long-established right to occupy the Plaza, going back to colonial times (Ortega Ricaurte Reference Ortega Ricaurte1990). There, they would have found a safe, capacious space for public displays of unity, numbers, and commitment (Tilly and Tarrow Reference Tilly and Tarrow2015: 153). Conversely, they would encroach on the narrow street between the Palace and the quarters of the Presidential Guard at their own risks. As most of them at this point were unarmed, they effectively hedged themselves in a physically vulnerable position that they were completely unprepared to hold.

This seemingly poor tactical choice is all the more remarkable that protesters had to pass through the Plaza to get to the Palace, and obstinately resist calls from some participants to occupy the former instead (see testimonies in Alape Reference Alape1983: 249). Yet a demonstration on the Plaza would have required protesters to articulate public claims. For what makes a public place a polyvalent medium for assemblies of all persuasions is the fact that it has no political meaning attached to it other than what its temporary occupants may bring with them (e.g. Bayat Reference Bayat2013: 175ss; Said Reference Said2015). In order to occupy the Plaza, protesters would have had to specify, at the very least, who they blamed for Gaitán’s assassination and what sort of political reshuffling the vacancy suddenly left by his death should trigger.

The obstacle, in the event, was not that protesters lacked answers to these questions: rumors had already begun to circulate, and were soon echoed on the radio, that Gaitán had been shot by a Conservative policeman (or a delivery boy from the Conservative newspaper El Siglo) and that President Ospina would most likely resign in response (or had already been hanged) (Alape Reference Alape1983: 256; Braun Reference Braun1985: 146; see also Williford Reference Williford, Augusto, Diago, Javier, Osorio, Alberto and Villalobos2009). Converting unsubstantiated rumors into public claims, however, would have laid the protesters open to the risk of discredit and the threat of governmental retaliation, should the rumors prove untrue—which they did. To paraphrase J. Markoff (Reference Markoff2010: 243–44), it was much safer to riot on behalf of rumors than to assembly in support of an openly expressed and rationally developed critique of government policy, because the first move redirected the threat of governmental repression onto those who sowed the rumors, while protecting the rioters themselves from charges of sedition.

By dragging the assassin’s cadaver to the doorsteps of the Presidential Palace, and then attempting to crucify him to the gates, the protesters forcefully transferred interpretive responsibility for Gaitán’s assassination and its political implications to public authorities. They dared the Conservative Government to reclaim the cadaver, and thus to reveal themselves to have been behind the assassination, at the same time as they addressed them a veiled threat of meeting a fate similar to the assassin’s if they did. But nobody ever came out of the Palace to remove or at least cover the naked corpse, which remained in the same position throughout the afternoon (Braun Reference Braun1985: 157).

Sequence 3: sustained collective violence

The standoff was eventually broken when one protester surged at a soldier, wrested his rifle, and took aim at the Palace’s windows. Returning fire, the Presidential Guard swiftly drove the protesters away. As they folded back on the Plaza de Bólivar, the protesters merged with new clusters of participants drawn primarily from neighboring blocks. Scattered attacks against governmental buildings and military barrages, accompanied by the ransacking of police stations and hardware stores for weapons, gradually gave way to the coordinated destruction of administrative buildings, Conservative centers, churches, and ecclesiastical institutions around the Plaza. The protest then seemingly devolved into a moral holiday, marked by the smashing of private cars, streetcars, and high-street stores, the liberation of prisoners, generalized looting, public sales of seized goods below market price, and festive drinking. Despite heavy rainfall, choking smoke, and the threat of stray bullets from ambushed snipers, street action continued throughout the night, until military reinforcements retook control of the city center sometime before dawn (for a movielike reconstruction, see Braun Reference Braun1985: 155–66).

I listed at the outset of this article the many disparate historical interpretations that the looting and destruction of the city center have elicited, and I noted that all these interpretations seem reasonably plausible. But that’s the rub: they all do. Which is the most plausible is a moot point, because plausibility is conditional on the type of targets that the observer choses to highlight: governmental buildings, ecclesiastical institutions, Conservative symbols, or commercial establishments and merchandizes. Conflicting interpretations naturally arise because the protesters aimed their attacks at a variety of targets without ever formally stating what they wanted from the political, religious, and economic elites who occupied these premises.

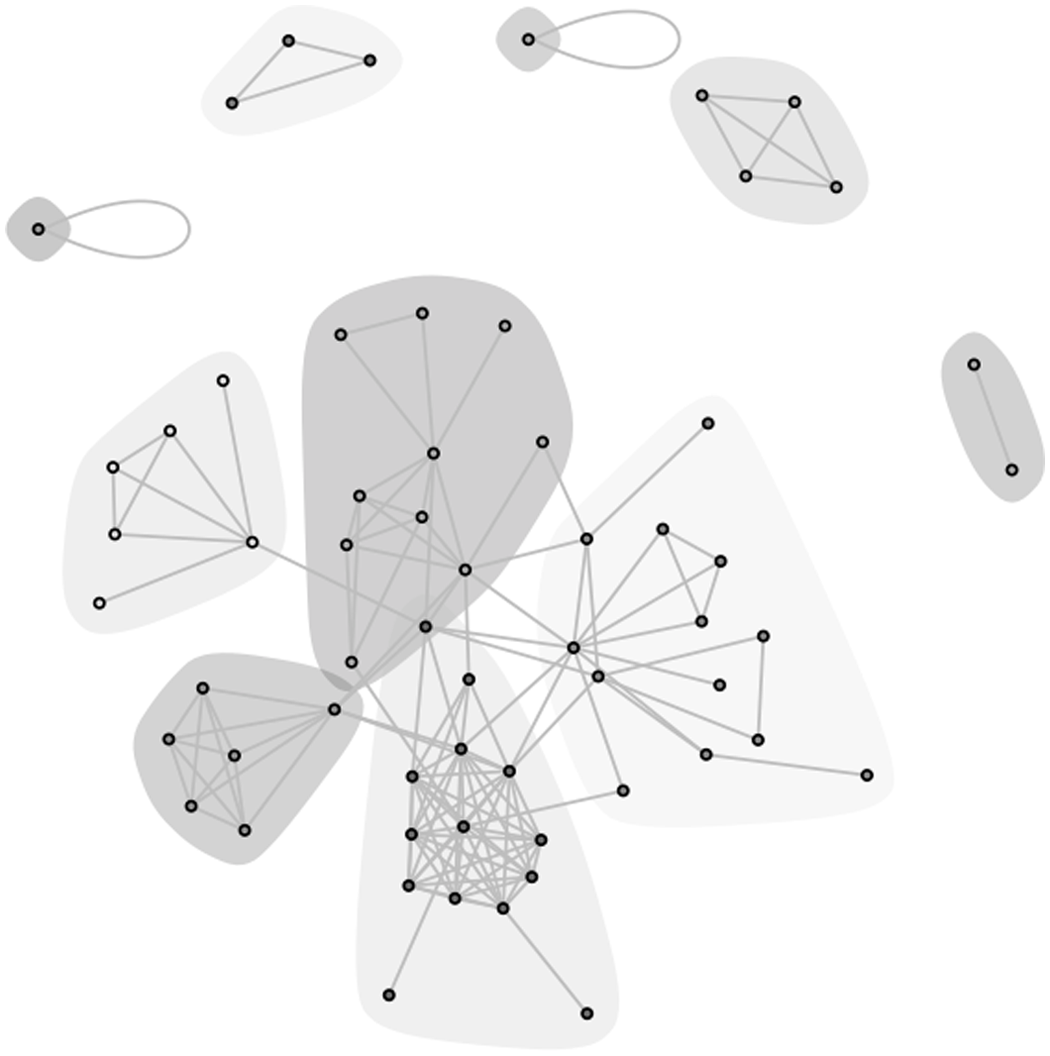

Taking advantage of Bogotá’s grid layout, we can economically visualize the Bogotazo as a network of targets. Each node in Figure 5 represents a city block containing at least one attacked (i.e. looted, torched, or both) building; an edge is drawn between every targeted block and any of its eight nearest neighbors if these also contained a target, and if the latter could be accessed by a straight walk (i.e. edges were omitted if a turn was required to go from one target to the other). While a map (e.g. Medina Reference Medina1984: 72) gives a misleading impression that the riots concentrated around key governmental and ecclesiastical buildings, because a planar representation tends to emphasize sheer physical distances, a network visualization allows us to take into account walkability. The result is that the most symbolic targets were in their majority isolated from the rest of the network, presumably because they were quickly shielded by military barrages, and because the largest share of participants arrived when collective action had already shifted to looting.

Figure 5. Looting and destruction during the Bogotazo.

Note: Governmental and ecclesiastical buildings have been shaded.

Since target selection responded so massively to dynamic constraints, the very project of supplying a post hoc interpretation of the Bogotazo on the basis of what this or that target might have meant to some imaginary protester is, arguably, wrongheaded. Looking for what the protesters did not say but could have, directs our attention away from what they actually did—which did not include, in the event, the sort of repertoire needed to broadcast definite claims to an attentive audience.

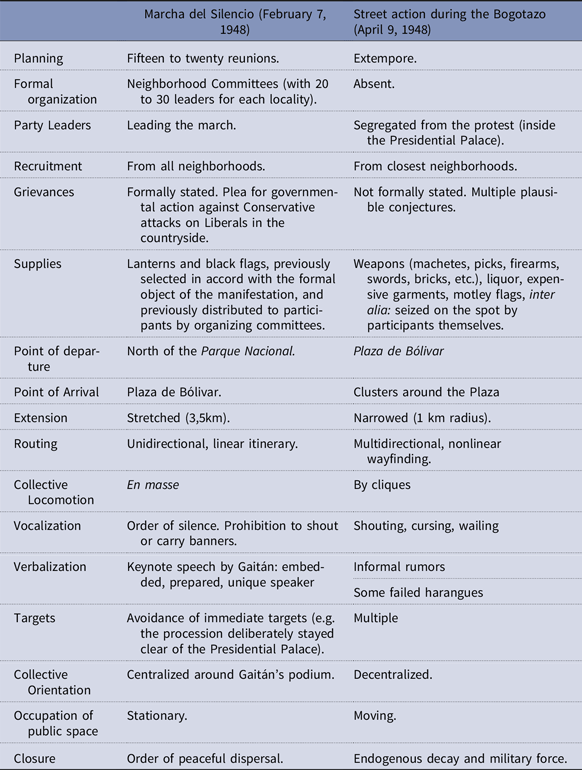

For contrast, consider the remarkably elaborate repertoire of mobilization that the Gaitanist movement had developed through countless rallies and marches during the recent electoral campaigns of 1945 and 1947 (Sharpless Reference Sharpless1978: 147–71; Braun Reference Braun1985: 91–129; Green Reference Green2003: 233ss). This repertoire had been most recently perfected with the Manifestación del Silencio of February 1948, called to denounce Conservative violence against Liberals in the countryside (see Table 1 ), often regarded as the most successful rally of Gaitán’s career (see Alape Reference Alape1983, 103–8). Events such as the Manifestación del Silencio were often planned weeks and sometimes months in advance. Drafting participants from distant neighborhoods, they carefully funneled them onto the Séptima, and then typically routed them to the Plaza de Bólivar. Strong limitations were placed on collective expression, either through mandatory silence or preselected banners, flags, and chants: Gaitán was meant to be the only official speaker. Crucially, the marches avoided direct contact with potential targets (in particular the Presidential Palace), lest unplanned surges should break marching order. At the Plaza, orderly collective occupation of public space was achieved by assigning each delegation to a specific location around the tribune where Gaitán would solemnly address protesters as his personal audience. Once the tribune had concluded his harangue, he would order the protesters to disperse peacefully.

Table 1. The Manifestación del Silencio and the Bogotazo

This configuration was turned on its head during the Bogotazo. Although some groups did initially parade in the streets with flags and banners from past mobilizations that did not quite match the occasion, most adopted a very different repertoire of contention. At such short notice, participants were chiefly drafted from locally available populations, with little immediate reinforcements from the rest of the city. Stochastic arrivals and departures caused considerable congestion. Locations in public space were constantly shifting, dictated by the tasks at hand, rather than fixed by categorical affiliation to a neighborhood committee. Along the way, almost all available targets were directly attacked, without explication de texte, because no banner or slogan had been preapproved. Instead, protesters shouted, cursed, and repeated wild rumors (for example, that the President and the leader of the Conservative party had been hanged). Although some Liberal leaders propped themselves up on streetcars and attempted to harangue the crowd, nobody paid them attention. No staged oratory performance captured the common focus, or produced an official interpretation on behalf of the gathering. Without ceremonial closure, dispersion was only brought about by a combination of endogenous decay and forced removal.

Yet despite initial appearances, the fundamental contrast between the two configurations is not between tidy organization and mayhem, but between two types of ordered sets. On the one hand, the linear ordering contrived by local Gaitanist committees and national party cadres is remarkable because it built on the simplest of order relations—with every participant occupying a structurally equivalent position of subordination to Gaitán. This pristine organization, however, required social organizers to remain in the background and to shunt distracting targets off the stage. On the other hand, and paradoxically, a thicket of confusion grew around the protesters on April 9 because they made no effort to conceal either their sources of supply or their targets. The resulting phenomenology was only dizzying because supplies and targets were chained together by looting and destroying establishments across several broad equivalence classes. Thus, supplies were drawn from “hardware stores” (makeshift weapons), “police stations” (firearms), and “high-street stores” (liquor, flags, and clothes), and targets were obtained from abandoned vehicles that could be attacked without weapons (cars and streetcars), protected buildings that could be stormed or fired at with weapons (e.g. “governmental buildings”), and undefended buildings that could just be destroyed (i.e. “governmental allies”, including the Church and the Conservative party).

We can easily represent these chains as forming a partially ordered set and contrast them with the set of actions during the Manifestación del Silencio (see Figure 6 ). The difference between the two sets, we may observe, is merely that the first only admits one total ordering, whereas the second is compatible with multiple possibilities. In short, contrary to what contemporary political observers hastily concluded (see Alape Reference Alape1983, 605–19), protesters did not run amok in the absence of competent organizational supervision. While we cannot tease out a unified political meaning of the street riots, we need not conclude that they lacked structure altogether. Protesters could not have sustained grueling actions for hours on end without inducing at least a few topological orderings. But these, in turn, merely followed from chaining together actions that might prompt a response from elites who could, and just might, authoritatively impose meaning on the situation.

Figure 6. Hasse diagrams for the Manifestación del Silencio and the Bogotazo.

Rushed versus delayed claim-making

Sequence 4: broadcasting the revolution

The protesters prompted a first, immediate response from a self-selected group of kibitzers. Small numbers of writers, journalists, academics, and students rushed to occupy all major radio stations in the city. They then went on air to announce that they were constituting themselves as “revolutionary juntas” and taking the reins of what they reframed as a revolution of the Colombian people (pueblo, revolución, and Colombia are the three most frequent words in our corpus, with 81, 51, and 40 occurrences respectively) (see Table 2 ). Yet, precisely because the protesters’ actions were not directed at them, the revolutionary juntas could only present themselves as the legitimate interpreters of the popular will by keeping up the fiction that these actions obeyed their explicit directives (e.g. the militaristic cry “A la carga!”, a trope borrowed from Gaitanist rhetoric, occurs 11 times in our corpus). This fiction, however, rapidly lost all plausibility as contradictions between street action and the narrative spewed on the radio cropped up.

Table 2. Most frequent nouns and adjectives in the Revolutionary Juntas corpus

First, though the narrative of a vanguard conducting the insurrection at a distance was nominally addressed to the protesters (repeatedly addressed as pueblo, movimiento, fuerzas [revolucionarias], compañeros, and calle), it was in practice heard by static listeners who were not engaged in street action. Thus, although the radios could not directly influence the behavior of actors on the ground, they could nevertheless generate expectations among listeners, which were at risk of being belied by the former. In a telling example, the radios announced that the army had taken sides with the insurgents and sent three tanks against the Presidential Palace. Listeners inside the Palace, including the President, initially succumbed to panic. Yet upon reaching their destination, soldiers inside the tanks revealed themselves to be loyalist troops (see the multiple testimonies collected in Alape Reference Alape1983: 278–80, 336–37, 340–48, 365–66). The radios also announced that the assassin was a Conservative policeman, that Laureano Gómez, President Ospina, and other prominent Conservatives had been lynched, that former Liberal president Eduardo Santos was returning from New York to assume the presidency, and that the Gaitanist Darío Echandía would assume power in the interim—all claims that would later be retracted.

Second, as the juntas had no means of enforcing the peremptory orders they issued on the air, the façade of authority that they attempted to present was vulnerable to popular actions that were formally inconsistent with the latter. Looting and festive drinking, in particular, alarmed the revolutionary juntas. The self-appointed president of the Comité Ejecutivo de la Junta Revolucionaria de Gobierno, Adán Andrade threatened the looters that they would be tried in a (made-up) Consejo Revolucionario (see testimony in Alape Reference Alape1983: 442). To be sure, these actions could have been narratively reconciled with other political interpretations of the situation. For example, looting would later be glossed as xenophobic reprisals against foreign economic interests (Sowell Reference Sowell1998) and festive drinking as a cross-class ritual of fraternization (Braun Reference Braun1985). But none of these alternatives was consistent with the rhetoric of disciplined masses obeying the direct orders of a revolutionary vanguard in pursuit of overarching political goals.

Interpretive incongruence was inevitable, third, because the revolutionary juntas could not move the narrative of a political revolution without the strategic cooperation of at least some state agents and political elites. These were needed to catalyze street action directly into state structures, force a removal of the President, and install a new government. The radios rushed to announce that the Liberal party, the army, and the police had joined the revolution against the Government (Liberal, gobierno, policia, and ejercito are all among the 10 most frequent words in our corpus). Yet despite some early individual defections,Footnote 10 most law enforcement and military forces in Bogotá adopted noncommittal lines of conduct throughout the afternoon, waiting for orders that cagey officials would not give. As a result, the narrative which was being looped on the radios of a triumphant offensive against and inside state structures appeared increasingly disconnected from the direction that street action was taking, ever further away from an assault on the Palace.

While it did little more than provide an increasingly out-of-touch commentary of the protests, the juntas’ precipitated claim-making on April 9 would retrospectively allow the Government to lay blame for the Bogotazo at the door of the Communist Party and the left-wing of the Liberal Party. Not unreasonably, historians (Aprile-Ginset Reference Aprile-Gniset1983; Sánchez Gómez Reference Sánchez Gómez1984; Braun Reference Braun1985; Martz Reference Martz2012 [1962]) have maintained that communists were opportunistically scapegoated by politicians who were eager to save face with international observers congregated in Bogotá for the Pan-American Conference. But regardless of the hidden intentions we may critically impute to the government, the fact is that when political observers searched for actors who had made explicit political claims during the Bogotazo, the only that could be found were the Leftist intellectuals and students who had repeatedly and emphatically called for an armed revolution on the radios.

Thus, although the board-game theory of revolutionary action advises to capture means of mass communication to establish a monopoly on the public interpretation of the situation, this can also be a liability, as actors who broadcast public claims become lastingly accountable for them. Conversely, the government quickly ordered a gag ruling on medias after Gaitán’s assassination. Even after the Army had regained control over most radio stations, a formal allocution by the President was not put out on the air until April 11, when the situation had definitely turned in favor of pro-governmental forces. More generally, we go on to see, the behavior of political elites in both the Government and the Opposition throughout the events was almost cautious to a fault.

Palace negotiations

The Liberal leaders who had gathered inside the Clínica Central delayed a public announcement of Gaitán’s death. Despite being called out by the crowd, they did not move from inside the clinic until they received an invitation from the President’s staff to meet with Ospina. They made a prolonged stop on their way to the Presidential Palace to ditch the cortege of protesters that accompanied them and to discuss strategy. Once at the Palace, they engaged in protracted negotiations with the Conservative President. When they emerged out of the Palace the next day, they had agreed to join a government of national unity led by Ospina, to back the President’s decision to declare a State of Emergency, and to let the military in charge of restoring public order.

Contemporary commentaries and retrospective history alike have often commended President Ospina for his ability to temporize a decision against mounting pressures, and criticized Liberal leaders for their unwillingness to pounce on the opportunity to seize power (e.g. Sharpless Reference Sharpless1978: 179; Sánchez Gómez Reference Sánchez Gómez1984: 22). The Government and the Opposition are thus respectively praised and blamed for adopting the exact same attitude—namely, deferring the articulation of an official position—during the Bogotazo. This seems to be a classic instance of asymmetrical explanation: the same variable is interpreted differently depending on whether we adopt the perspective of the winning or the losing side. Instead of siding with the victor, we should ask two questions: Why did both sides operate on the theory that they should stave off a formal claim to power? Why was one side able to outlast the other?

The eventual asymmetry of positions is all the more remarkable that the President and Liberal leaders met in an initially level playing field. Both sides faced equally intense levels of “environmental impatience” (Gibson Reference Gibson2011). Not only were external events impinging on the negotiations (sometimes directly, as when a stray bullet lodged itself into a wall of the conference room), but both sides were furthermore under threat of being overran by their extremes. On the one hand, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the parliamentary wing of the Conservative Party (led by the ultraconservative Laureano Gómez) initially pushed for a military government.Footnote 11 On the other hand, the revolutionary juntas called for an insurgent government. These two variables reinforced each other, for once inside the palace, both sides were physically cut out from the outside; both were accordingly dependent on extremely unreliable radio and phone communications with their impatient allies for information on the evolution of the situation on the street. A game of patience was therefore equally uncertain and perilous for both sides.

Second, and at the same time, face-to-face negotiations were inescapable because neither side had a free hand. The Opposition could not lawfully seize power as long as President Ospina was in place; they therefore needed him to tender his formal resignation to create a legal vacancy that would justify the designation of an interim President from the Liberal party. Similarly, President Ospina needed to secure the Opposition’s support because he could not lawfully declare a State of Emergency without the cooperation of the Legislative and the Judicial branch of government, which were controlled by Liberal majorities. Hence the minimalistic terms of the negotiations: each side merely pressed the adversary to redefine the situation in a way that would then allow them to make a strong claim to power. As any of these two options required that the other be formally rescinded, formal negotiations were at an impasse before even starting.

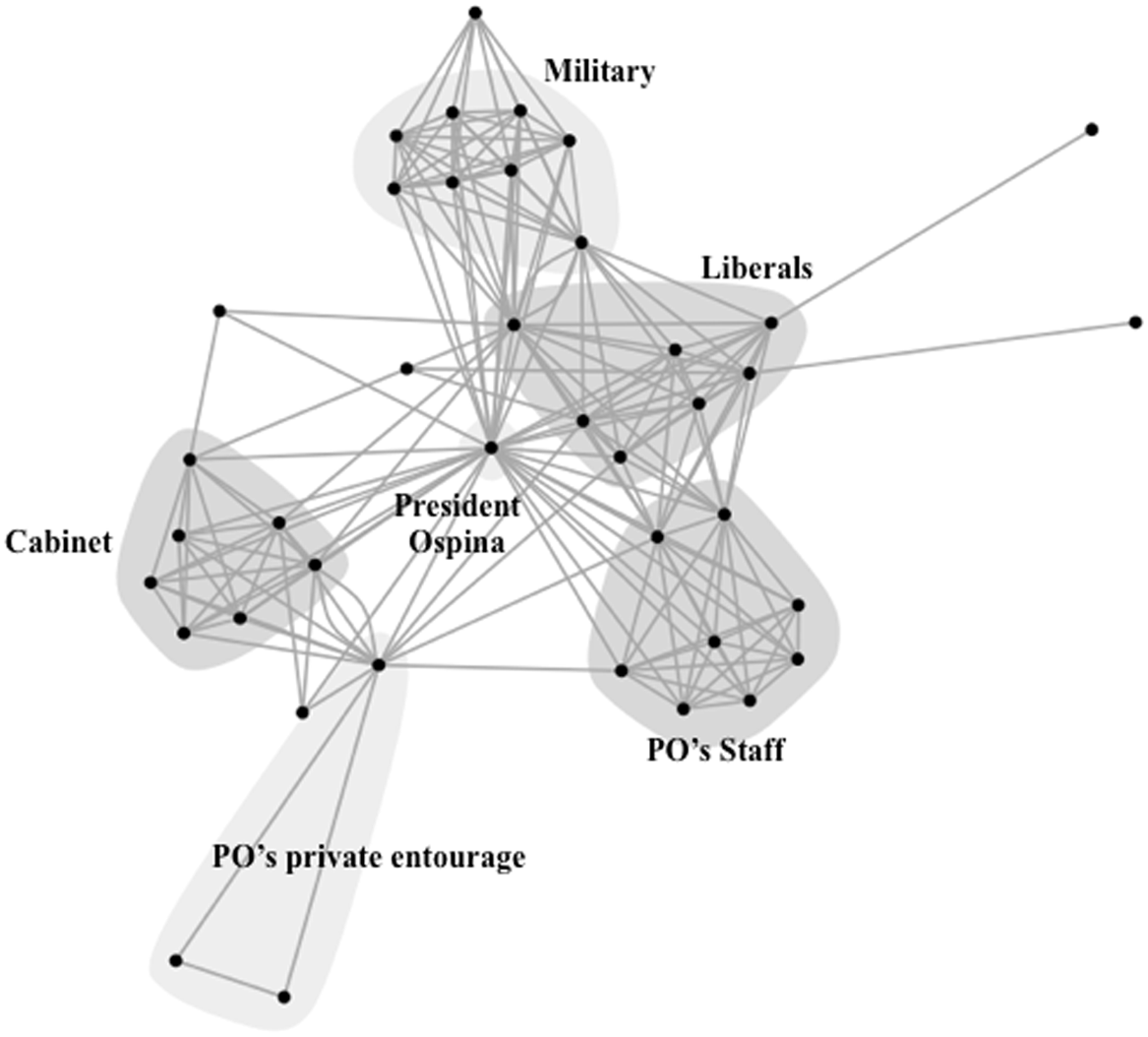

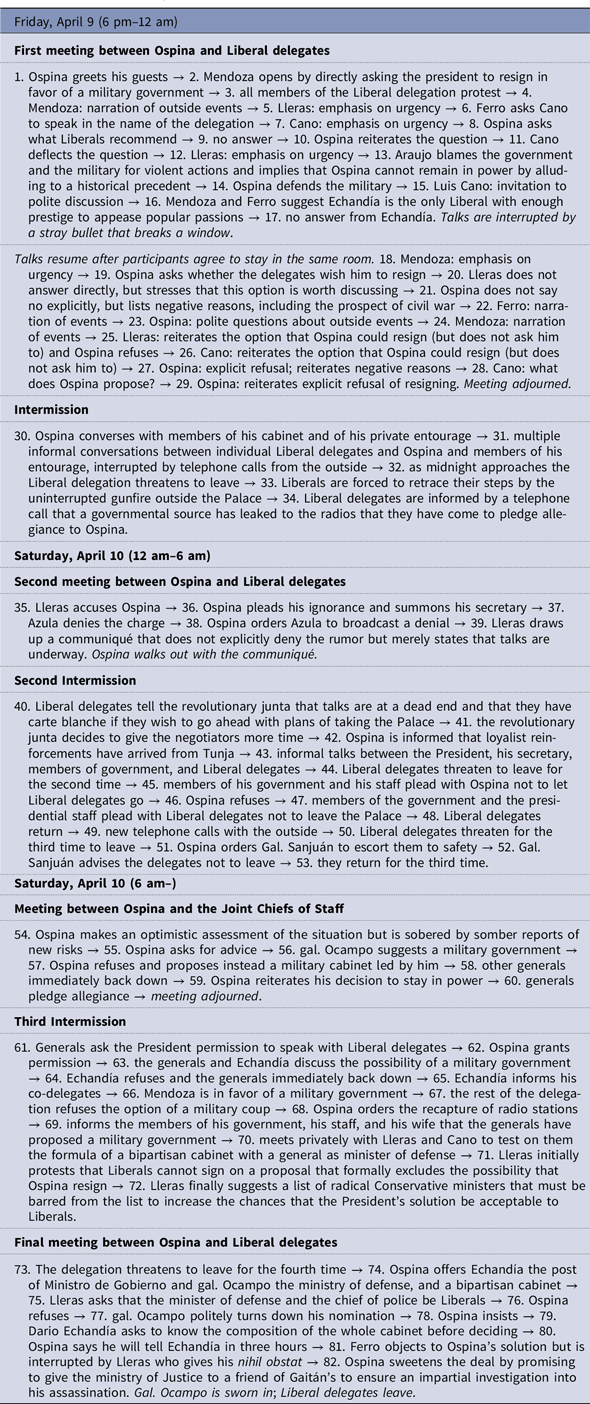

To understand how this deadlock was eventually broken, we must, first, call attention to the checkered pattern of the negotiations. Discussions between the President and leaders of the Opposition were constantly interrupted. Interruptions occurred because Ospina was simultaneously engaged in several other conversation networks—with military advisers, members of his government and his party, his personal staff and private entourage, and outside informants (including Laureano Gómez)—that made requests on him in a stochastic fashion, as fresh news arrived that urgently needed to be discussed. Liberals, too, were occasionally approached by individual participants in the President’s conversation networks, and they had their own contacts with outside informants through the telephone. Instead of using the Presidential palace to centralize all participants inside a unique “situation room”, President Ospina freely circulated between them, and no less significantly authorized others to interact both within and outside their respective circle without his being present to supervise their exchanges (see Figure 7 ).

Figure 7. Conversations inside the Palace.

Despite gaps in our timeline and imperfect data on the specifics of verbal behavior, we can identify recurring patterns within conversations by looking at the fairly limited set of topics broached by participants. Table 3 summarizes the timeline of events.Footnote 12 Most strikingly, sustained attention to explicit proposals never occurred until the final round of negotiations. Prior to this point, whenever explicit proposals were hazarded by a participant, other participants invariably withdrew their support, and the topic was immediately dropped (e.g. 2→3, 16→17, 56→58, 63→64). Instead, each side repeatedly attempted to coax or extort indications of personal disposition and political position from the other. Participants thus attempted to prompt a response with threats to abandon the negotiations (e.g. 32, 44, 50, 73), pressures on external actors (e.g. 34, 40, 68), emphasis on time constraints and environmental pressures (e.g. 5, 7, 12, 18 and 4, 22→23→24, 52, 54), turn-transfer—i.e. asking somebody else to speak—and role-transfer—assessing hypothetical scenarios from somebody else’s point of view (e.g. 6, 8, 10, 19, 28, 50, 57 and 20, 25→26, 57, 72).

Table 3. Timeline of Meetings and Events Inside the Palace

These two patterns of interaction—conversational decentralization and indirections—allowed participants to engage in a continuous process of “Bayesian updating” (Mische and White Reference Mische and White1998) on both external events and internal interactions. First, circulation between conversational networks, in the long periods of intermission between talks, created frequent opportunities to gage the disposition of other participants and exchange news from the outside. Second, during talks, conversational indirections (for instance when an actor asked a direct question refuses to answer by keeping silent or by changing the topic) successively led to the revelation that Darío Echandía was reluctant to assume power (16→17), that President Ospina would not resign (25→26→27→28→29; 57), that the generals were unwilling to push for a military government without political support from at least one of the two main parties, which neither was willing to grant (58, 64), that the revolutionary juntas would not attempt an all-out assault on the Palace (40→41), that the Liberal delegates would not leave the Palace without a political solution (32, 44, 50, 73), and that a bipartisan cabinet might be acceptable to both Conservatives and Liberals (70→71→72). Only then did Ospina make his move (73).

The observed outcome therefore gradually emerged from, but required the temporal dilation of, the negotiations (compare with Gibson Reference Gibson2011: 404–5). Participants who were the most mobile between conversation groups throughout these protracted negotiations were more often exposed to fresher information, and thereby acquired frequent occasions to update their perception of shifting circumstances and dispositions. And none was more active than President Ospina. Yet, far from being the product of deliberate planning or political savviness, Ospina’s centrality in an otherwise decentralized conversational network merely followed from his being simultaneously the frequent addressee of urgent news, in his official capacity as President, and the (occasionally reluctant) addresser of repeated marks of attention to all his guests, in his courteous role as host.

Discussion

Since Snow et al.’s (Reference Snow, Rochford, Worden and Benford1986) landmark article on frame alignment, students of social movements have come to assume that collective action requires participants to coordinate around a common interpretation of the grievances they wish to present. Although there may initially be several framings available, consensus should quickly “crystalize” around one of them (Snow et al. Reference Snow, Vliegenthart and Corrigall-Brown2007). The default scenario was most elegantly outlined by R. Gould (Reference Gould1995: 200): first, a “given instance of political or social conflict… [such as] an assassination… will render salient only one or a few identities out of a wide range of candidates”; a popular mobilization will then be able to rally around the winning platform, generating contentious performances broadly understood to support a recognizable cluster of collective claims. Although Gould conceded the possibility that a great many political entrepreneurs may initially “compete to provide definitive interpretations of what is going on”, he nevertheless took it for granted that a relatively coherent platform would come out of this liminal situation—otherwise, individual participants would lack a plausible rationale for joining the fray, especially if danger is involved.

My analysis of the Bogotazo, however, reveals the intriguing possibility that mass mobilization can not only take off without a clear winner emerging from this initial interpretive shuffle, but that it may in fact require to defer a verdict indefinitely. Gaitán’s assassination, rather than rendering salient a unifying platform, spewed instead a stream of equivocal collective performances. Indeed, while most historians have prudently glossed it over, I gave special attention to the assassination because I wanted to show that, far from merely “triggering” an episode of social conflict, as if the subsequent mobilizing dynamics were already in place, this event was really the first in a chain of equivocal challenges. Similarly, I concluded my analysis with the negotiations between political elites to show that, despite the apparent contrast between polite talks inside the Palace and collective violence on the street, both involved similar processes of pushing others to show their hand before venturing explicit claims of one’s own.

In light of this generalized interpretive shuffle, a key finding of this article is that rushed claim-making during contentious events may very well be a losing tactic. Publicly tying oneself to a definite position has several disadvantages: it limits claimants’ ability to adapt to changing circumstances, allows others to hold them accountable for what they do and say, and makes them vulnerable to retaliation by increasing their visibility. Conversely, ambiguity has tactical value because it is noncommittal (see Leifer Reference Leifer1988): it keeps participants’ options open, shifts the burden of interpreting the situation on other actors, and thus lets the latter define the field of contention before challengers decide to stake out a formal position within the latter.

On April 9, the only actors who did not at least initially dodge the responsibility of making public claims on behalf of the protesters were the self-styled “revolutionary juntas”. As a result, they unintentionally laid themselves open to being almost at once discredited—and then, in the following months, to intense political repression. In contrast, caution generally paid off. Although greater advantages accrued to the actor who waited the longest to stake a formal claim to power (i.e. President Ospina), others were also rewarded for their restraint. Thus, no effort was made to identify or prosecute the members of the mob that lynched Gaitán’s assassin or marched on the Palace. Similarly, most of the protesters captured on April 9 and 10 were eventually released without charges, and a general amnesty was decreed before the year was over (L. 82/48, diciembre 10, 1948, Diario Oficial [D.O.]). Leaders of the Liberal party were admitted into the government, where they negotiated a vast electoral reform that essentially secured their victory in the 1949 legislative elections (L. 89/48, diciembre 16, 1948, Diario Oficial [D.O.]). The one exception to this rule seems to have been Gaitán’s assassin. But then again, although he was put to death on the spot, he did acquire posthumous fame by the same token.

Why were the revolutionary juntas virtually alone in rushing to make claims about the mobilization? It is easy to impute their foolhardiness to the political inexperience and idealism of the youthful students and intellectuals that composed them. But a less invidious hypothesis is that the historical precedent that Leftist Colombian intellectuals consciously sought to emulate—the Bolshevik seizure of power during the 1917 Revolution—seemingly suggested that an audacious vanguardist minority could hijack a turbulent situation to stake out its own claim to power. Though Colombian intellectuals can hardly be blamed for buying into the narratives of “Red October” that were then prevalent, it must be pointed out that the latter distorted in fundamental ways the unfolding of events that actually led Lenin and his followers to victory: in practice, Bolsheviks exercised great tactical caution, and won the day in no small measure because the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries, conversely, did not (see Rabinowitch Reference Rabinowitch1976).

While capturing radio stations afforded the revolutionary juntas social a public platform that uncontrollably reached beyond their regular confidential audiences, other actors were forced to exercise communicative caution precisely because they could only count on the limited span of their preexisting network affiliations. Whether to pull off an assassination, improvise a demonstration, sustain collective mobilization, or negotiate a political agreement, they only had immediate access to, and a legitimate expectation of cooperation from, a handful of people. This was true including when these interactions took place in the context of what may look to a distant observer like huge, anonymous crowds: for even in a sea of people, every participant is only sited next to a few others.

This goes to the heart of the methodological problem raised by equivocal challenges. If we are looking for evidence that our actors deliberately fudged their motivations, we are setting ourselves on a fool’s errand. Only actors that were incredibly unskilled would let themselves be caught broadcasting their intention to disguise their intentions. A better question is therefore to ask how actors might develop the “social skill” (Leifer Reference Leifer1988) required to mount an equivocal challenge.

On this point, our evidence suggests that social skill has less to do with personal ingeniousness than with connectivity. Like Padgett and Ansell’s (Reference Padgett and Ansell1993) portrait of Cosimo de Medici, the actors of the Bogotazo did not need to be exceptionally shrewd or manipulative to adopt courses of action displaying high tactical ambiguity. The impostures that Roa contrived, the repertoire of collective violence that protesters adopted, the diplomatic indirections that political elites employed were not particularly inventive. But they worked because they were embedded in heterogeneous networks that refracted and augmented them. Thus, and most emblematically, the reason that President Ospina gained a decisive advantage over his rivals and a hold on a dangerously uncertain situation was not that he displayed a superior political acumen. Instead, he won the day by merely doing what every good host should do—attend to all of his guests.

These are the immediate implications of the Bogotazo. An unresolved question concerns the historical significance of this event. A common diagnostic among historians is that the Bogotazo split Colombian history in two (see Braun Reference Braun1985: 3, 192, 251–52). Perhaps a more accurate way to frame this issue would be to say that the Bogotazo stands awkwardly in between two notable periods of Colombian history: the Liberal Republic (1930–46) and La Violencia (late 1940s-early 1960s). Indeed, the Bogotazo can neither be understood as the final act of the former nor as the launch of the latter. On the one hand, the Liberal Republic was marked by a hegemonic Liberal party, governmental stability, and organized public mobilization, while the Bogotazo combined the weakness of the Liberal party, complete institutional disruption, and spontaneous street action. On the other hand, the homicidal patterns of La Violencia were rural, explicitly partisan, and long-drawn-out, while the Bogotazo was urban, politically unaffiliated, and short-lived. I would therefore argue the Bogotazo should not be understood as the fulcrum between one period and the next. Rather, it briefly concentrated, and in so doing brought to light, the multiple ambiguities of this interval phase: neither peace nor all-out civil war yet, no hegemonic dominance from either of the two main parties, and a public space that had not yet been shut down but that was no longer safe for collective mobilization.

Conclusion

Being together in public is merely a precondition for issuing credible contentious claims. But it is up to protesters to select which claims they want to voice, and indeed, whether or not to voice them out. Indeterminacy is thus built in public contention. I have shown that this indeterminacy can be tactically harnessed, turned against specific targets, and indefinitely perpetuated by protesters. The concept of equivocal challenges is just one heuristic tool to observe and account for the tactical use of ambiguity during public protests.

Significantly, the word contention is itself ambiguous. It can apply to a power struggle or to a persuasive claim in a debate. To contend is both to strive in opposition and to advocate for a cause in public. This dual meaning is perfectly apt, for the same dilemma is constitutive of contentious events. Just as claims without backing from a large movement lack credibility, so too, a collective mobilization unaccompanied by a legitimate political message risks being dismissed as irrational mob action. Mobilization and advocacy must somehow be patched together. But there is no guarantee that they will be.

When protesters fail—or choose not—to clarify their agenda, we should not rush to doing it on their behalf. Of course, it is entirely justified to bring out evidence that explicit claims were in fact issued but then knowingly suppressed either by governmental censorship or by a politically motivated historiography, the classic example being Thompson’s (Reference Thompson1971) analysis of 18th century “food riots”. But often enough analysts find themselves in just the opposite situation. When this is the case, our role is not to compete with local authorities, political entrepreneurs, and social commentators in the ventriloquist act of speaking in the name of tenaciously reticent actors. The task of the analyst, to adapt a familiar argument (e.g. Bourdieu Reference Bourdieu1988), is not to take sides in this interpretive shuffle, but to understand how the latter naturally springs from, and is decisively fed back to, an inherently ambiguous situation.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a grant from the University of Los Andes. I am grateful to John Markoff for comments and criticism on an earlier draft. I would also like to thank Miguel Torres, Herbert Braun, Gabriel Escalante, Ricardo Arias, Carlos Andrés Charry, and Anthony Picón for advice and help with locating sources. Suggestions by two anonymous reviewers and the journal’s editors greatly improved the article. Special thanks should go to Daniela Fazio, who helped code all the files of the Proceso Gaitán and provided invaluable assistance and critical feedback throughout this project.