Introduction

Understanding the geographical distribution and migration patterns of blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) (Linnaeus, 1758) populations is an essential prerequisite for the formulation and implementation of effective conservation measures within the northeast Atlantic. Despite historical exploitation as a result of commercial whaling between the late 19th and mid-20th centuries (Brown, Reference Brown1976; Tønnessen and Johnsen, Reference Tønnessen and Johnsen1982), the blue whale remains a cosmopolitan species ubiquitous throughout the world's major oceans (Yochem, Reference Yochem1985).

Four distinct subspecies are currently recognized (committee on Taxonomy, Reference Taxonomy2021) which generally conform to populations with defined geographical distributions: B. m. musculus in the North Atlantic (Pike et al., Reference Pike, Víkingsson, Gunnlaugsson and Øien2009) and North Pacific (Calambokidis et al., Reference Calambokidis, Barlow, Ford, Chandler and Douglas2009); B. m. intermedia in the Southern Ocean surrounding Antarctica (Attard et al., Reference Attard, Beheregaray and Möller2016) and South Atlantic (Thomisch, Reference Thomisch2017); B. m. brevicauda in the southern Indian Ocean, subantarctic zone and southwestern Pacific Ocean (Ichihara, Reference Ichihara and Norris1966) and B. m. indica in the northern Indian Ocean from the Bay of Bengal west to the Gulf of Aden (Charles et al., Reference Charles, Branch, Alagiyawadu, Baldwin and Marsac2012).

The North Atlantic population was long thought to comprise two separate putative populations divided between the East and West Atlantic (Ingebrigtsen, Reference Ingebrigtsen1929; Gambell, Reference Gambell1976; Best, Reference Best1993); however, more recently photo identification studies (Sears et al., Reference Sears, Vikingsson, Santos, Steiner, Silva and Ramp2015), satellite tracking (Heide-Jørgensen et al., Reference Heide-Jørgensen, Kleivane, ØIen, Laidre and Jensen2001) and passive acoustic monitoring investigations (Clark, Reference Clark1994) indicated some degree of mixing, more reminiscent of a single panmictic population roaming the entire North Atlantic basin as originally suggested by Thompson (Reference Thompson1928).

The distribution of blue whales in the northeast Atlantic appears to range from The Gambia south of Cape Verde (Djiba et al., Reference Djiba, Bamy, Samba Ould Bilal and Van Waerebeek2015) northwards to Svalbard, only limited by the extent of the pack ice (Ingebrigtsen, Reference Ingebrigtsen1929; Leonard and Øien, Reference Leonard and Øien2020). Whilst migration routes remain poorly understood, the North East Atlantic population generally adheres to an annual northward migration to productive feeding areas in the summer and then return via similar routes southwards to calving and mating grounds in sub-tropics during winter (Jonsgård, Reference Jonsgård and Norris1966; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Haug and Øien1992; Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Smith, Josephson, Clapham and Woolmer2004).

Pre-exploitation population estimates within the North Atlantic remain ambiguous (Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Clapham, Brownell and Silber1998). Gambell (Reference Gambell1976) suggested that the population comprised between 1100 and 1500 individuals; however, estimates by Rørvik and Jonsgård (Reference Rørvik and Jonsgård1978) and more recently by Aguilar and Borrell (Reference Aguilar and Borrell2022) implied abundance was far higher numbering ca. 12,500 and 15,000–20,000, respectively. As a result of commercial whaling between the 1860s and 1960s, the same population was estimated to have decreased to approximately 100 individuals (Gambell, Reference Gambell1976) constituting only 0.5–9.1% of their potential historic abundance.

North Atlantic catch records compiled by the International Whaling Commission (IWC) indicate that ca. 11,000 blue whales were taken as a result of commercial whaling between 1868 and 1978 (Branch et al., Reference Branch, Allison, Mikhalev, Tormosov and Brownell2008; Allison, Reference Allison2017). When taking into account an additional 13,000 individuals that were classified as unidentified large whales (Allison, Reference Allison2017) and the high percentage of ‘struck and lost’ records (Tønnessen and Johnsen, Reference Tønnessen and Johnsen1982), it is likely that blue whale mortality rates were in fact much greater between 15,000 and 20,000 (Cooke, Reference Cooke2018).

Under the auspices of the IWC, North Atlantic blue whales were afforded protection in 1955, which was later extended to Antarctica in 1965 and to the North Pacific in 1966 (Best, Reference Best1993). In direct contradiction to the IWC's moratorium in 1955, Iceland refused to conform until 1960 (Tønnessen and Johnsen, Reference Tønnessen and Johnsen1982). The North Atlantic population is now classified as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species and is protected under Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) of Wild Fauna and Flora and the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) (Oliver, Reference Oliver2018).

Since the abolition of commercial exploitation in 1966, the northeast Atlantic blue whale population has slowly begun to recover at a rate of ca. 5% per year (Sigurjónsson and Gunnlaugsson, Reference Sigurjónsson and Gunnlaugsson1990; Pike et al., Reference Pike, Víkingsson, Gunnlaugsson and Øien2009). Abundance estimates remain tenuous; however, Pike et al. (Reference Pike, Gunnlaugsson, Mikkelsen, Halldórsson and Víkingsson2019) suggested that ca. 3000 individuals were present in the North Atlantic in 2015 which would constitute between 15 and 20% of the potential pre-exploitation abundance as presented by Aguilar and Borrell (Reference Aguilar and Borrell2022).

Sustained multilateral conservation efforts underpinned by international legislation guided principally by up-to-date and robust scientific studies are required to ensure the northeast Atlantic blue whale population continues to recover. This study raises questions surrounding our current understanding of distribution and migration phenology of the blue whale in the North East Atlantic by documenting the first live sighting in the central North Sea, a new area of occurrence for the species.

Materials and methods

Dedicated visual observations specifically targeting marine mammals were conducted as part of a wider benthic habitat assessment and environmental baseline survey being undertaken aboard the research vessel Fugro Venturer during the survey period 25th October to 16th December 2020.

Visual observations were undertaken by a single dedicated marine mammal observer (MMO) from the vessel's bridge during hours of daylight.

The primary observation technique adopted by MMOs was to scan the area 360° around the vessel with the naked eye inspecting any areas of interest using 7 × 50 mm Helios marine reticle binoculars. Visual cues indicative of marine mammal presence included blow spray, surface disturbance, irregular white water, bird activity, dark or light shapes below the surface and of course visible surface behaviour. When possible, sighting photographs were captured using a Nikon D750 DSLR camera and Nikkor 200–500 mm telephoto zoom lens. Area coverage was non-systematic and dependent on vessel movements throughout the survey.

Results

At 10:21 (UTC) on the 9th of November 2020, two blue whales were observed at position 55°13.99′N, 01°13.62′W, 18 km off the east coast of the UK in the central North Sea just north of Newcastle at a water depth of 76 m (BSL) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map highlighting the sighting location of two blue whales (B. musculus) 18 km off the east coast of the UK in water depth of 76 m relative to bathymetry and land.

The pair were initially sighted at a range of 1750 m crossing perpendicular to the bow of the vessel at a bearing of 340° to true north heading towards the coast due west at 270°. As the vessel was travelling at 3.1 knots on a bearing of 350° proximity to the whales decreased to a closest distance of 1000 m before moving away and eventually out of sight of the vessel at 10:54 (UTC).

The encounter lasted a total duration of 33 min with both individuals surfacing four to six times before diving for 3–5 min. Upon surfacing the rostrum, splashguard and shoulders initially broke the surface immediately followed by a tall columnar blow ca. 6–8 m, the body then rose exposing vast flanks after which the blow hole disappeared beneath the surface initiating a long slow roll eventually revealing the dorsal fin before sinking gracefully below the surface. The caudal peduncle was raised high out of the water immediately prior to long dives, however, at no point were the tail flukes observed above the surface.

Prevailing weather conditions were not particularly conducive to visual observations with advection fog reducing visibility to ca. 3 km; swell was low (<2 m); sea state slight (no or few white caps) and wind force ranged from Beaufort force three to four.

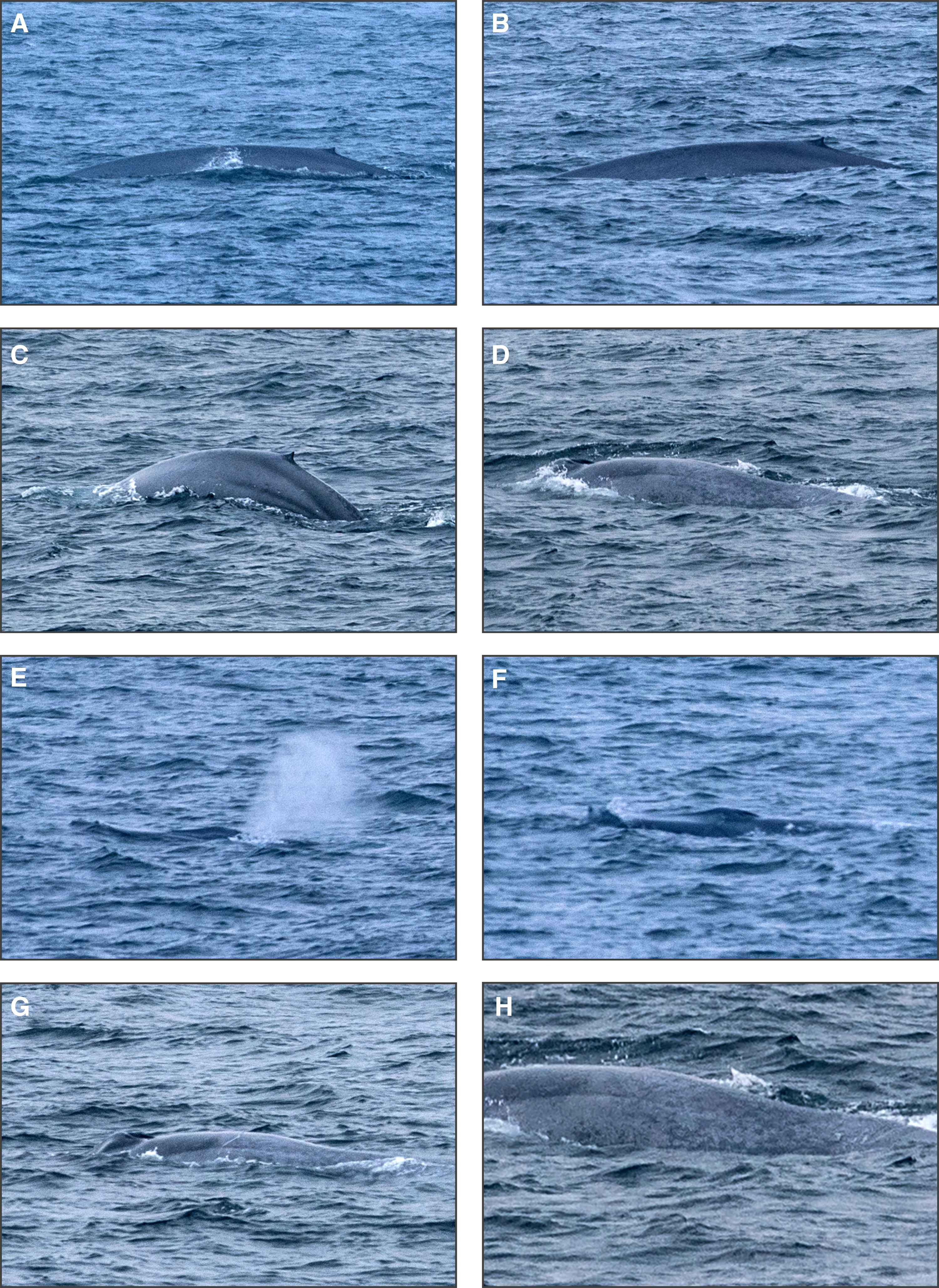

Despite unfavourable weather conditions, key diagnostic features were clearly visible as the two individuals transited across the bow of the vessel. Both individuals were ca. 20–25 m in length and presented the following key diagnostic features: diminutive falcate dorsal fin located close to posterior; extremely robust caudal peduncle; mottled blue to grey dorsal surface and flanks; tall columnar blow ca. 6–8 m high; proportionately long U-shaped rostrum with single rostral ridge and heavily pronounced splash guard (Figure 2).

Figure 2. (A) Images of a blue whale (B. musculus) photographed on the 9th of November 2020 using a Nikon D750 DSLR camera and Nikkor 200–500 mm telephoto zoom lens (© Edward Lavallin, 2020). Key diagnostic features include: (B) diminutive falcate dorsal fin located close to the posterior; (C) extremely robust caudal peduncle raised out of the water prior to longer dive; (D) mottled blue grey colouration on dorsal surface and flanks; (E) tall columnar blow ca. 6–8 m high (bushy and dispersed by wind in this image); (F) proportionately long U-shaped rostrum with single rostral ridge; (G, H) heavily pronounced splash guard.

Whilst no feeding behaviour was observed at the surface, numerous benthic trawl fishing vessels were present in close proximity to the sighting location in much higher concentration than observed on previous days. At the time of the sighting the vessel's Hugin 1000 autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) also picked up a high-density target on the integrated obstacle avoidance sonar and when returned to deck numerous northern krill (Meganyctiphanes norvegica) (Sars, 1857) were found trapped within the AUV housing.

Sighting photographs were sent to Richard Sears at the Mingan Island Cetacean Study for further analysis; however, we were unable to match either individual to the North Atlantic blue whale database (R. Sears, pers. comm., 24th November 2020).

Discussion

To draw conclusions from a single-opportunistic sighting is not only challenging but exceeds the capacity of this paper. We can, however, discuss the potential significance of this particular observation in light of current literature highlighting areas requiring further research to aid ongoing conservation efforts.

Distribution in the northeast Atlantic

Blue whale distribution in the northeast Atlantic appears to range from Svalbard in the Arctic (Leonard and Øien, Reference Leonard and Øien2020) southwards to the sub-tropics of The Gambia south of Cape Verde (Djiba et al., Reference Djiba, Bamy, Samba Ould Bilal and Van Waerebeek2015). Blue whales have been documented historically in landing records from UK whaling stations based in the Hebrides and Shetland Islands on the west coast of Scotland (Brown, Reference Brown1976). Strandings have also been recorded along the west coast of Scotland, notably on the Isle of Colonsay in 1916 as well as the Isle of Eigg and Isle of Lewis both in 1920 (Coombs et al., Reference Coombs, Sabin, Cooper, Allan, Smith, Lyal and Museum2018). Stranding records from the adjacent North Sea are particularly scarce, comprising single events from Belgium in 1827, Holland in 1840 (Smeenk and Camphuysen, Reference Smeenk, Camphuysen, Broekhuizen, Spoelstra, Thissen, Canters and Buys2016), Germany in 1881 (Möbius, Reference Möbius1885) as well as two accounts from Denmark in 1907 and 1931 (Kinze, Reference Kinze, Baagøe and Jensen2007). Strandings on the northeast coast of the UK are limited to a single record from Staxigoe in 1923 (Coombs et al., Reference Coombs, Sabin, Cooper, Allan, Smith, Lyal and Museum2018) ca. 375 km north of the sighting on the 9th of November 2020.

Whilst the North Sea is known to accommodate three mysticete species, comprising Balaenoptera acutorostrata (Lacépède, 1804), B. physalus (Linnaeus, 1758) and Megaptera novaeangliae (Borowski, 1781) (Hammond et al., Reference Hammond, Lacey, Gilles, Viquerat, Börjesson, Herr, Macleod, Ridoux, Santos and Scheidat2017; Leopold et al., Reference Leopold, Rotshuizen and Evans2018; Leonard and Øien, Reference Leonard and Øien2020), its’ relatively shallow waters are not considered to provide acceptable habitat for B. musculus, which generally frequent deeper water off the continental shelf (Sears et al., Reference Sears, Wenzel and Williamson1987; Víkingsson et al., Reference Víkingsson, Pike, Valdimarsson, Schleimer, Gunnlaugsson, Silva, Elvarsson, Mikkelsen, Øien and Desportes2015). Three separate large-scale monitoring surveys titled Small Cetaceans in European Atlantic waters and the North Sea (SCANS, SCANS II and SCANS III) were conducted in 1994 (Hammond et al., Reference Hammond, Berggren, Benke, Borchers, Collet, Heide-Jørgensen, Heimlich, Hiby, Leopold and Øien2002), 2005 (Hammond et al., Reference Hammond, Macleod, Berggren, Borchers, Burt, Cañadas, Desportes, Donovan, Gilles and Gillespie2013) and 2016 (Hammond et al., Reference Hammond, Lacey, Gilles, Viquerat, Börjesson, Herr, Macleod, Ridoux, Santos and Scheidat2017), respectively. Whilst other large rorquals were recorded, at no point were B. musculus encountered within the North Sea (Hammond et al., Reference Hammond, Lacey, Gilles, Viquerat, Börjesson, Herr, Macleod, Ridoux, Santos and Scheidat2017). Comparable large-scale shipboard cetacean surveys conducted by Leonard and Øien (Reference Leonard and Øien2020) in the North Sea and greater northeast Atlantic between 2014 and 2018 also failed to record the B. musculus in the North Sea.

To the best of our knowledge, this record is the only confirmed account of live blue whale presence in shallow coastal waters of the central North Sea and highlights a new area of occurrence within the accepted range of the northeast Atlantic population, an area in which sightings of this poorly understood and endangered species are extremely rare.

Migration routes in the northeast Atlantic

The northeast Atlantic blue whale population appears to conform to a general pattern of migration in which summers are spent feeding at high latitudes as far north as the Fram Strait west of Svalbard, followed by migration southwards through the Norwegian Sea, Faroe-Shetland channel and west of Ireland towards lower latitudes around the Azores and Mauritania in winter (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Haug and Øien1992; Reeves et al., Reference Reeves, Smith, Josephson, Clapham and Woolmer2004; Visser et al., Reference Visser, Hartman, Pierce, Valavanis and Huisman2011; Baines and Reichelt, Reference Baines and Reichelt2014; Leonard and Øien, Reference Leonard and Øien2020; Pérez-Jorge et al., Reference Pérez-Jorge, Tobeña, Prieto, Vandeperre, Calmettes, Lehodey and Silva2020). Historically, southward migration from summer feeding grounds was thought to begin in September (Ingebrigtsen, Reference Ingebrigtsen1929). Recent passive acoustic monitoring studies conducted by Charif and Clark (Reference Charif and Clark2009) indicate peak abundance north and west of the UK occur between November and December; therefore, the two individuals observed on the 9th of November generally conform to accepted migration phenology. Their presence within the central North Sea, however, indicates significant migration route deviation and supports suggestions of migration plasticity as documented by Szesciorka et al. (Reference Szesciorka, Ballance, Širović, Rice, Ohman, Hildebrand and Franks2020).

Research is only just beginning to elucidate the drivers and environmental cues associated with blue whale migration behaviour and relatively little is known about the spatiotemporal intricacies of routes taken (Oliver, Reference Oliver2018; Szesciorka et al., Reference Szesciorka, Ballance, Širović, Rice, Ohman, Hildebrand and Franks2020). This is particularly pertinent in the northeast Atlantic (Pike et al., Reference Pike, Víkingsson, Gunnlaugsson and Øien2009) an area which would benefit from increased research effort.

Prey presence and influence on migration

North Atlantic blue whales are stenophagous, feeding almost exclusively on zooplankton predominantly comprised of northern and arctic krill (M. norvegica and Thysanoessa raschii (Sars, 1868) respectively) in the summer months (Sears et al., Reference Sears, Wenzel and Williamson1987; Pauly et al., Reference Pauly, Trites, Capuli and Christensen1998) and generally avoid feeding behaviour in favour of fasting whilst overwintering (Corkeron and Connor, Reference Corkeron and Connor1999), a concept collectively referred to as the ‘feast and famine’ hypothesis.

More recently, however, research conducted by Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Prieto, Jonsen, Baumgartner and Santos2013) highlighted that some blue whales exhibit opportunistic feeding behaviour deviating from migration pathways to spend time in areas of high localised productivity as observed in other rorquals including Southern Hemisphere humpback whales (M. novaeangliae) (Gales et al., Reference Gales, Double, Robinson, Jenner, Jenner, King, Gedamke, Paton and Raymond2009; Silva et al., Reference Silva, Kaufman, Hutsel, Macie, Maldini and Rankin2011; Zerbini et al., Reference Zerbini, Andriolo, Danilewicz, Heide-Jørgensen, Gales and Clapham2011). Whilst feeding behaviour was not observed during the sighting, dense concentrations of northern krill detected on the AUV obstacle avoidance sonar, combined with increased fishing vessel presence, was indicative of high localised productivity. Whilst anecdotal, prey presence and the potential for opportunistic feeding behaviour may partially explain why two blue whales were observed in an area considered outside their usually accepted range. Tagging and satellite-tracking studies, such as those conducted by Silva et al. (Reference Silva, Prieto, Jonsen, Baumgartner and Santos2013) and Pérez-Jorge et al. (Reference Pérez-Jorge, Tobeña, Prieto, Vandeperre, Calmettes, Lehodey and Silva2020) in the Azores, focusing on the northernmost extent of blue whale range in the northeast Atlantic would provide much needed insight into the intricacies of southward migration routes and behaviours aiding ongoing conservation efforts.

Conclusion

It is difficult to draw conclusions from a single ‘fluke’ encounter obtained under opportunistic circumstances; however, to the best of our knowledge, this paper is the only confirmed account of live blue whales in the central North Sea and signifies a new area of occurrence, extending the accepted range of the northeast Atlantic population.

The record supports suggestions that blue whale migration routes and timings express a certain degree of plasticity with some individuals potentially deviating from suggested migration routes to take advantage of localised areas of high productivity through opportunistic feeding behaviour.

Industry-focused surveys which incorporate dedicated cetacean monitoring offer an opportunistic platform for research mitigating the usually high costs associated with offshore cetacean surveys, however, inherent operational constraints can detract from the overall merit of findings.

Dedicated satellite tracking and genetic sequencing studies focusing on the northernmost extent of blue whale range in the northeast Atlantic are required to address paucity in information surrounding migration spatiotemporal dynamics and behaviour to assess implications on conservation efforts.

Only through peer-reviewed scientific publications derived from robust scientific studies can policy makers formulate and implement effective conservation legislation to ensure the continued recovery of a still heavily depleted blue whale population in the northeast Atlantic.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our gratitude to the crew of the research vessel Fugro Venturer for their company and hospitality during our time aboard the vessel. We would also like to thank Fugro for allowing the sighting and associated findings to be published.

Author's contribution

Edward Lavallin conducted all field work and prepared the manuscript. Nils Øien assisted in verifying the sighting. Richard Sears conducted photographic identification and evaluation against the North Atlantic blue whale database. Both Richard and Nils provided expert insight and advice contributing significantly to the final publication. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript prior to publication.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

None.