Mala Pećina Cave and the Balkan Neolithic

The Eastern Adriatic context has long been disputed within archaeological discourse on the Neolithic period in south-east Europe. Questions concerning social organisation, the Mesolithic to Neolithic transition, economy and interaction between the Eastern Adriatic and both the Balkan hinterland and the Western Adriatic dominate the debate (see, for example, Forenbaher et al. Reference Forenbaher, Kaiser and Miracle2013; Orton et al. Reference Orton, Vander Linden and Pandžić2014). Ongoing excavations at Mala Pećina Cave in southern Croatia aim to illuminate the relationships between coastal societies and hinterland groups (see also Biagi et al. Reference Biagi, Shennan, Spataro, Nikolova, Fritz and Higgins2005). The main objectives for the 2016 campaign were to understand the role played by the cave in the passage that crosses the Dinaric Alps, and to investigate if the cave was part of a route that connected the Adriatic coast with the Balkan hinterland.

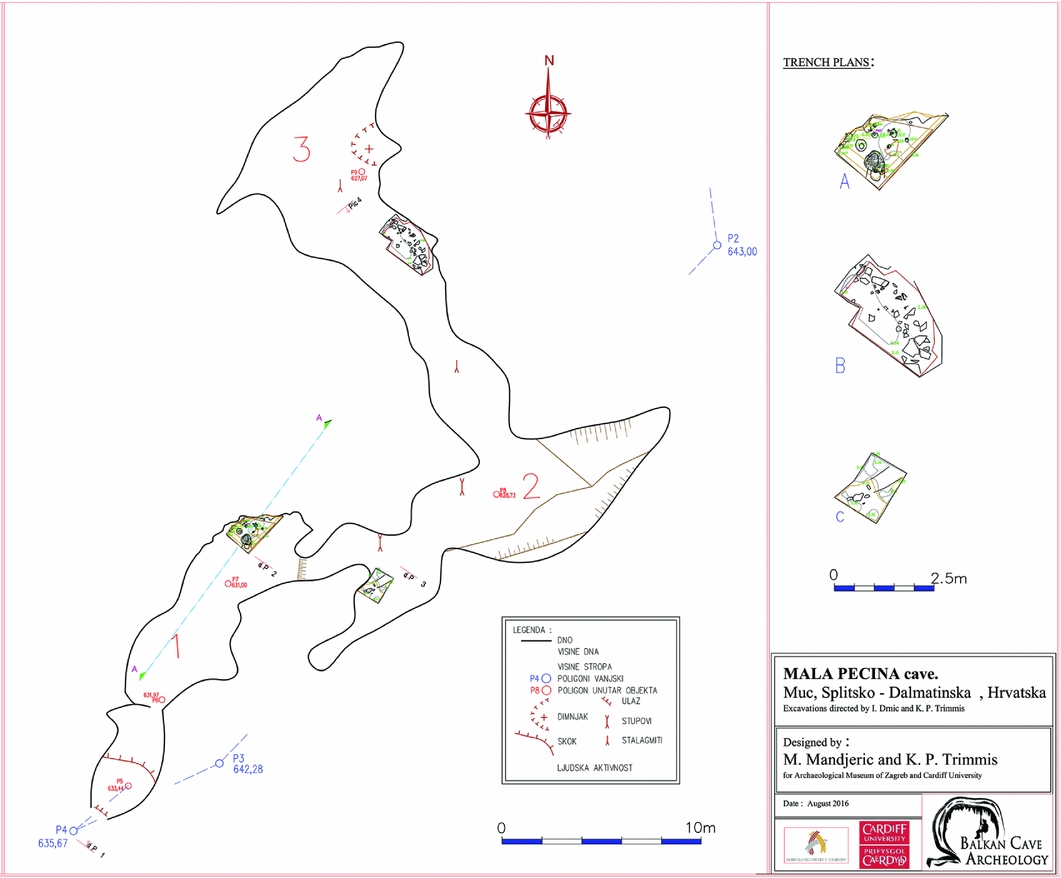

Mala Pećina (or Nova Pecina) Cave is located in the hinterland of Dalmatia (Zagora) in southern Croatia. The cave is deep in the hills, almost a mile south of the road connecting the town of Sinj with the village of Gorni Muć (Figure 1). The cave comprises three chambers, with a low, long passage linking chambers two and three (Figure 2). Don Miho Granić, a local priest, discovered Mala Pecina in the late nineteenth century, and it became the first cave survey to be published in a Croatian scientific journal (Granić Reference Granić1882). In 1998 and 2003, an archaeologist from the Archaeological Museum in Split conducted a walkover survey (Kliškić Reference Kliškić2004). In 2010, an expedition of the Speleological Society for Filming and Survey Karst Phenomena from Zagreb re-visited the site. The team recovered Early Neolithic pottery sherds and an articulated bone fragment from the low passage. The bone fragment was analysed by Beta Analytic (Miami, USA) and yielded a date between 5780–5650 cal BC (Beta-287818).

Figure 1. Mala Pecina's location in the Dalmatia region, Croatia, and in relationship with Sutina village.

Figure 2. The plan of the cave. Designed by Toni Terez and modified by M. Manderjić.

The 2016 excavation

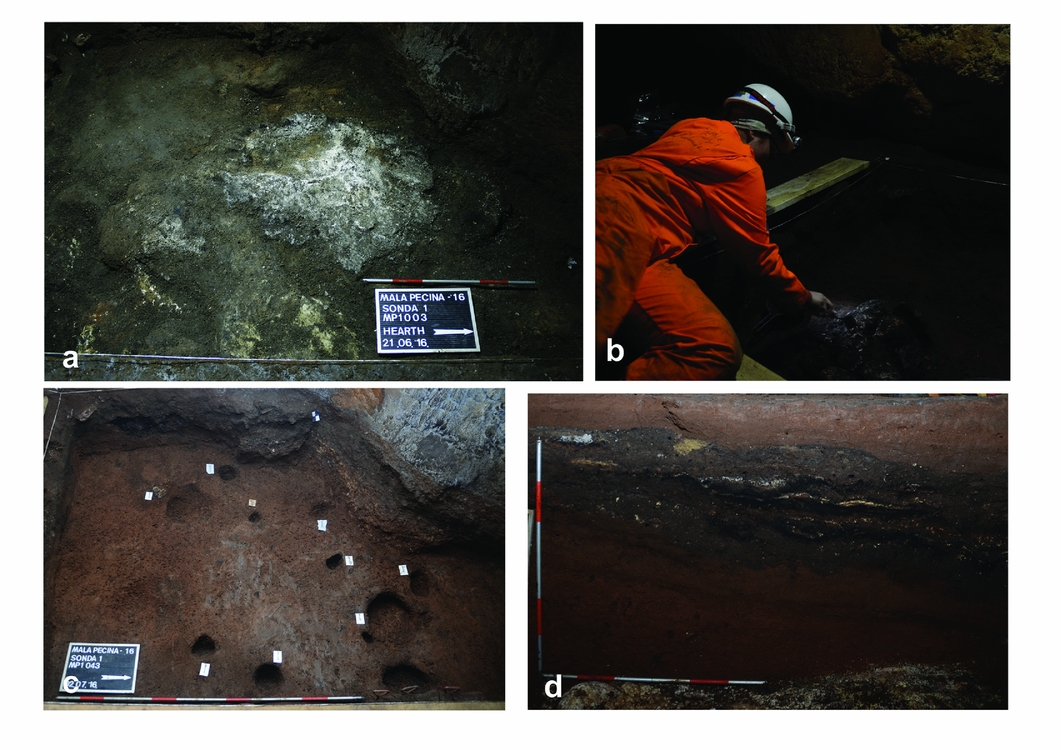

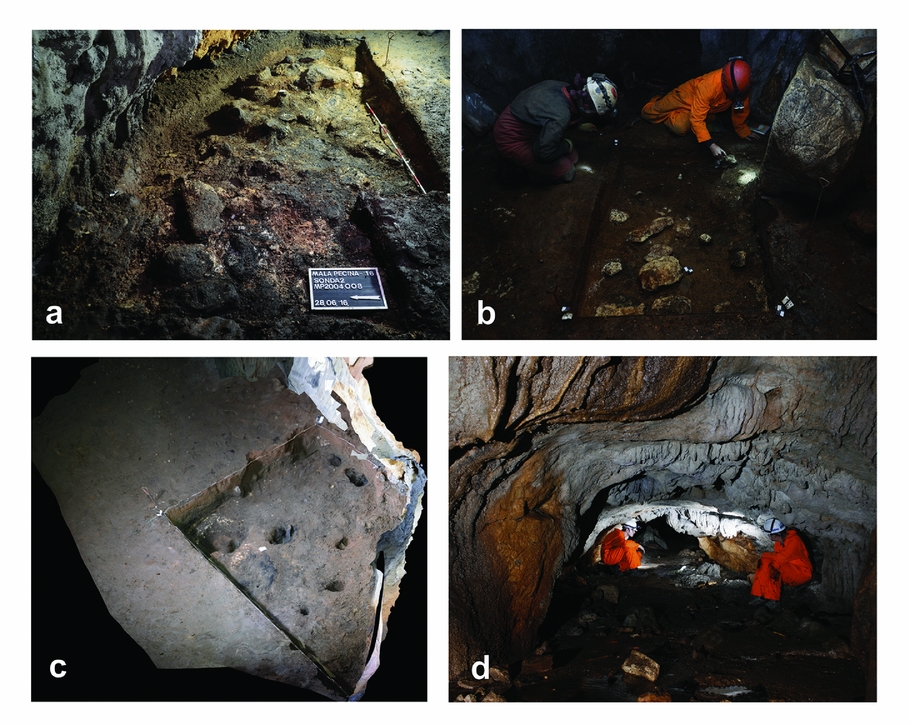

Excavations in 2016 opened three trenches: trench 1 at the end of the first chamber; trench 3 at the southern end of the second chamber; and trench 2 at the point that the lower passage leads to the third chamber. The upper layers of trench 1 revealed an organised hearth with associated Late Neolithic pottery. Directly beneath the hearth was a sterile horizon that sealed an Early Neolithic layer. This formed the fill of a cut, which is defined by a series of stakeholes, to the west and north of the trench. At the centre of this complex was a large posthole with stone filling at the base, along with a complex of three shallow pits (Figure 3). Trench 2 in the low passage yielded exclusively Early Neolithic material, including a dry stone feature. This may represent a low wall that was part of a circular or semi-circular structure (Figure 4). At the base of the fill of the structure was a burnt layer containing animal bones. In trench 3 a layer of burnt stones was unearthed, among which was a decorated stone with curves, lines and possible red colouring.

Figure 3. a) The Late Neolithic hearth; b) excavating the base of the Early Neolithic posthole; c) the Early Neolithic postholes; d) the west-facing section of trench 1.

Figure 4. a) The Early Neolithic structure in trench 2; b) excavating trench 3; c) 3D model of the Early Neolithic layers of trench 1; d) view of the long passage, chamber 2; trench 2 is located at the end.

Connecting worlds

The spatial arrangement of the archaeological features, bones and pottery finds in the Late Neolithic layer of trench 1 may suggest that the cave functioned as a temporary shelter for mobile groups during the Late Neolithic.

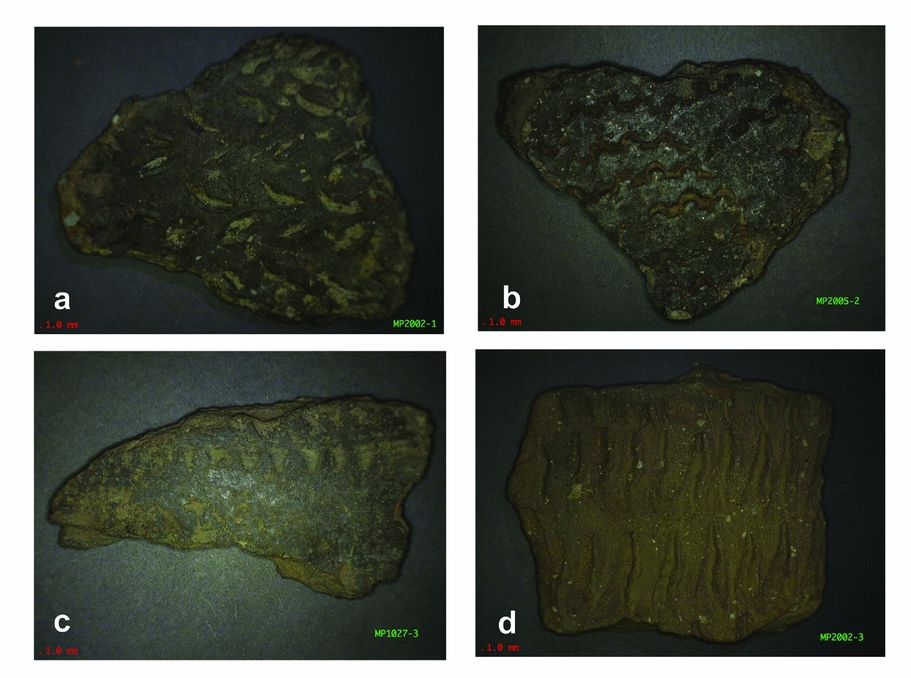

Preliminary dating evidence from trench 2 places the Early Neolithic occupation at Mala Pećina in the first half of the sixth millennium BC. The presence of both coastal and hinterland Impresso-type pottery (Figure 5) in the same context (Mala Pećina, 2001) indicates that the Adriatic Neolithic might not just be the predecessor of the Balkan hinterland Neolithic. On the contrary, Neolithic groups in both areas may have been in contact from the very early centuries of the sixth millennium BC.

Figure 5. Pottery sherds with Impresso decoration from trench 2.

Mala Pećina presents the Early Neolithic ‘package’ with decorated pottery, structures, signs of ritual activities (trench 3) and evidence for domesticated animals and plants. These groups were neither living within the cave, nor staying inside for long periods (for seasonal-periodical occupation). The bone assemblage comprising mainly young animals, and the large quantities of open vessels suggest that the cave was used for social congregation by groups travelling between the Adriatic coast and the central Balkan plains. More research is required in order to investigate the patterns and the duration of such movement. Mala Pećina provides a good example of the connection of two areas—the coast and the hinterland—separated by the Dinaric Alps. It also indicates that there was no clear Early Neolithic coast to hinterland route, but rather more of a mutual interaction between the respective Early Neolithic groups of each area. The Dinaric Alps may be a ‘marginal space’ where different cultural groups were in contact and exchanged ideas and objects.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Cardiff University, the British Cave Research Association, the Conservation Department of the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Croatia in Trogir, the caving club DISKF from Zagreb and the Archaeological Museum in Zagreb for their support. K.P. Trimmis is also grateful to the Greek Archaeological Committee of United Kingdom for their support for his doctoral studies, of which the Mala Pećina research formed a part.

In the article by Trimmis and Drnić (Reference Biagi, Shennan, Spataro, Nikolova, Fritz and Higgins2018), the caption for Figure 2 contained two spelling errors. The correct caption is as follows: Figure 2. The plan of the cave. Designed by T. Terezić and modified by M. Mađerić.