Introduction

Since the mid-1990s there has been an unprecedented expansion of temporary labour migration in Australia. This has occurred through the creation of new temporary visa categories aimed at attracting migrant workers qualified to address high-skilled vacancies and the expansion and repurposing of other schemes that have effectively become ‘de facto’ low-skilled visas (Reference Wright and ClibbornWright and Clibborn, 2017). This development is significant because it contrasts with the system of permanent migration that prevailed in Australia throughout much of the 20th century.

Until recently, Australian governments consciously shunned guest-worker systems in order to prevent migrant workers from being exploited, which was seen as important for maintaining social cohesion (Reference Markus, Jupp and McDonaldMarkus et al., 2009). As recently as 2006, Peter Costello, the Treasurer in the Howard Coalition government, rejected the idea of such a shift in Australia’s immigration policy: ‘Australia has never been a guest-worker country. We’ve never been a country where we bring you in and ship you out. I don’t think Australia will be a guest-worker country and I don’t think Australians want to see that’ (Reference GordonGordon, 2006).

In this article, we argue that, in contrast to the statement above, Australia has nonetheless moved towards a ‘guest-worker’ system of temporary migrant labour. Guest-worker schemes have been used in Western Europe, Singapore, Japan and Gulf Cooperation Council states, and through schemes specific to the agriculture industry in many countries (Reference Davies, Costello and FreedlandDavies, 2014; Reference MartinMartin, 2003; Reference Yea and ChokYea and Chok, 2018). The features of these schemes vary, but most definitions point to policies restricting the rights of migrants to settle permanently, or to move freely between different employers, and making migrant workers’ residency rights conditional upon retaining employment with their sponsoring employer (Reference Baldwin-EdwardsBaldwin-Edwards, 2011; Reference MessinaMessina, 2007). Their essential feature is to curtail migrant workers’ rights, agency and bargaining power, which can produce short-term dividends for businesses and governments seeking a more cost-efficient and productive workforce (Reference Papademetriou and SumptionPapademetriou and Sumption, 2011). While guest-worker schemes can provide migrant workers with better employment and income opportunities compared to those available in their home countries (Reference RuhsRuhs, 2013), these schemes have been found to contribute to migrant worker exploitation and labour market segmentation (Reference Wright, Groutsis and van den BroekWright et al., 2017; Reference Yea and ChokYea and Chok, 2018).

In earlier articles, we have identified the reasons for policy changes that have contributed to the growth of temporary migrant labour schemes in Australia since 1996 (Reference Wright and ClibbornWright and Clibborn, 2017) and analysed the rise of employer theft of temporary migrant workers’ wages during this period (Reference Clibborn and WrightClibborn and Wright, 2018). By contrast, this article draws upon secondary sources to present an historical and comparative analysis of the bargaining power and agency granted to migrant workers in Australia under two different labour immigration policy regimes: the period from 1973 to 1996, when labour immigration policy was defined by a system of permanent skilled visas; and the period since 1996, when temporary skilled visas were introduced on a large scale and various de facto temporary work visas were expanded. The article builds upon existing scholarship demonstrating how immigration status can contribute to worker vulnerability (e.g. Reference AndersonAnderson, 2010; Reference Sargeant and TuckerSargeant and Tucker, 2009) by analysing four themes identified in the wider literature on the factors affecting the power and agency of migrant workers: residency status, mobility, skill thresholds and institutional protection.

Using these criteria, our analysis finds that migrant workers prior to 1996 had comparable bargaining power and agency to non-migrants, which prevented them from being systematically exploited at the workplace and marginalised in the labour market. In recent years, however, policy changes have diminished migrants’ power and agency substantially, placing them at higher risk of vulnerability and contributing to the rising incidence of employer theft of migrant workers’ wages (Reference Clibborn and WrightClibborn and Wright, 2018). Our arguments contrast with recent optimistic assessments of the temporary migration system operating in Australia (e.g. Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA), 2019; see also Treasury/Department of Home Affairs, 2018), Footnote 1 which do not adequately account for incremental yet significant changes in this system that have failed to protect, and in some cases systematically weakened, the bargaining power and agency of migrant workers.

Literature review: Factors affecting the bargaining power and agency of migrant labour

People who move from one country to another in order to work typically have less knowledge than other workers about the labour market, in terms of available job opportunities, their workplace rights and entitlements and how to protect them. These information asymmetries aside, we should not presuppose that migrant workers are necessarily more vulnerable than other workers (Reference BauderBauder, 2006). However, there is a growing body of scholarship on how immigration rules can weaken the position of migrants at work (e.g. Reference AndersonAnderson, 2010; Reference Sargeant and TuckerSargeant and Tucker, 2009). This article builds upon this scholarship by drawing insights from the wider literature on migrant workers, which suggests there are four specific factors affecting their bargaining power and agency: residency status, mobility, skill thresholds and institutionalised protections. We now examine these four factors in turn.

First, a person’s residency status, particularly in terms of whether or not they possess citizenship, determines their access to the rights and benefits that citizenship entails. In some countries, non-citizens’ residency rights are conditional upon maintaining employment and, unlike citizens, their access to social security and welfare support is restricted (Reference Goldring and LandoltGoldring and Landolt, 2013; Reference WalshWalsh, 2014). Limits on unemployment protection and health, education and child care support can have the effect of shifting ‘the cost of social reproduction from the state to the immigrants’ (Reference BauderBauder, 2006: 27). This can increase migrants’ dependence on employment and thereby heighten their vulnerability to underpayment and other mistreatment. By contrast, citizenship and permanent residency generally confer full access to employment and social rights, which can allow people to leave or change employment without compromising their residency rights (Reference BauderBauder, 2008; Reference Dauvergne and MarsdenDauvergne and Marsden, 2014).

Second, restrictions on the freedom of workers to exercise mobility between employers is a feature of certain temporary immigration schemes (Reference AndersonAnderson, 2010). Visas that tie workers’ right to live in a country to maintaining employment with a sponsor or requiring them to get an employer to certify their employment in order to gain a visa extension have become more common in recent years (Reference SumptionSumption, 2019). Such schemes are seen as effective ways of ensuring that migrants work for organisations where their skills are in greatest demand (Reference RuhsRuhs, 2013; Reference Wright, Groutsis and van den BroekWright et al., 2017). However, immigration rules that limit worker mobility between employers can weaken migrant workers’ capacity to exercise voice or to exit from exploitative employment relationships (Reference Cangiano and WalshCangiano and Walsh, 2014; Reference HoweHowe, 2019; Reference ZouZou, 2015).

Third, visa categories often specify a skill threshold for migrant workers to gain entry, that is, the possession of specific qualifications to perform certain occupations or a minimum level of general qualification (e.g. a university degree). The rationale for such thresholds is to protect the labour market by ensuring that migrants gain employment in occupations where their skills are most needed. However, skill thresholds can also serve to protect migrants from being mistreated. Employers typically place greater value on specialised and scarce skills. This provides high-skilled migrants with mobility and the capacity to command higher wages and better conditions. By contrast, the agency, mobility and bargaining power of migrant workers with generalised skills that can be easily replaced is generally limited, thereby placing low-skilled migrants at greater risk of exploitation (Reference AndersonAnderson, 2010; Reference DauvergneDauvergne, 2016; Reference WalshWalsh, 2014).

Finally, studies have identified the importance of institutional protections for migrant worker power and agency. Such protections can exist in the form of strong trade unions and/or government agencies to enforce minimum employment standards and monitor employer behaviour. In countries and sectors with laws and traditions that make it difficult for unions to represent workers, bargain collectively and engage in industrial action, or if government inspectorates do not have adequate resources to ensure systematic compliance, migrant workers are more likely to be underpaid and otherwise mistreated (Reference Afonso and DevittAfonso and Devitt, 2016; Reference McGovernMcGovern, 2007; Reference ZouZou, 2015).

Scholars have used these four criteria relating to residency status, mobility, skills thresholds and institutional protections to analyse migrant workers’ risk of marginalisation under certain temporary and employer-sponsored visa schemes (e.g. Reference BauderBauder, 2006; Reference DauvergneDauvergne, 2016; Reference Wright, Groutsis and van den BroekWright et al., 2017). These criteria can be used as a framework for assessing migrant worker bargaining power and agency under the immigration policies operating in certain countries and at particular historical moments, such as guest-worker schemes.

Perhaps the most famous examples of guest-worker schemes were those established in the post-war decades in many Western European countries. Guest-workers in these countries were generally concentrated in lower skilled employment, discouraged from bringing their family members, and often employed on a rotational basis where their stay was limited to a specified number of months or years at which point they were required to depart and make way for other guest-workers (Reference GeddesGeddes, 2003; Reference HammarHammar, 1985). Such policy arrangements in West Germany represented ‘the pinnacle of the guest-worker system’ (Reference CastlesCastles, 1986: 768): Temporary migrants were entitled to ‘all basic rights, except the basic rights of freedom of assembly, freedom of association, freedom of movement and free choice of occupation, place of work and place of education, and protection from extradition abroad’ (Foreigners Act, quoted in Reference CastlesCastles, 1985: 522). West Germany and every other Western European country that adopted guest-worker schemes had abandoned them by the 1970s, in part because of poorly designed policies that attempted to treat ‘migrants purely as economic men and women, and to separate between labour power and other human attributes’ (Reference CastlesCastles, 1986: 776).

To use the four criteria introduced above, guest-workers in West Germany had weak bargaining power and agency by virtue of their temporary residency status, constrained mobility and employment typically in low- and intermediate-skilled jobs (Reference CastlesCastles, 1986). However, migrant workers generally received institutional protection, and therefore comparable wages and working conditions, because they were employed in a labour market where unions were strong and collective bargaining coverage extensive (Reference Penninx and RoosbladPenninx and Roosblad, 2000). This represents a contrast with certain contemporary guest-worker schemes. For example, under the work permit systems operating in Sweden, temporary migrant workers are entitled to be paid in accordance with the relevant collective agreement. However, there are problems with enforcing this provision in industries where unions are weak, such as hospitality and horticulture, which account for large shares of work permits. The lack of a labour inspectorate to enforce labour standards compounds these institutional protection deficiencies (Reference Woolfson, Fudge and ThörnqvistWoolfson et al., 2014).

More extreme contemporary examples can be found in the Gulf Cooperation Council countries and Singapore. In addition to migrant workers having temporary immigration status with low skill thresholds and strict constraints on their mobility, institutional protection in the Gulf Cooperation Council is very low due to weak unions and ineffective labour enforcement regimes that fail to monitor unscrupulous employer behaviour (Reference Baldwin-EdwardsBaldwin-Edwards, 2011). Temporary migrant workers in these countries thus have weak bargaining power and agency making them highly vulnerable to exploitation. This situation has parallels with Singapore where the work permit system grants significant control to sponsoring employers and imposes restrictions on temporary migrants’ ability to exit from exploitative employment relationships or seek redress. This represents an institutionalised form of ‘unfreedom’ that contributes to degraded working conditions and labour and human rights violations (Reference Yea and ChokYea and Chok, 2018).

Previous studies have pointed to differences between labour immigration policy arrangements in contemporary Australia and those under the various guest-worker schemes discussed above (Reference MaresMares, 2016). However, they share key similarities, including the removal of safeguards that once ensured migrant workers in Australia were employed on terms equal to citizens. After first establishing the historical context of Australia’s migration policies, the following sections use the framework of criteria influencing migrant workers’ power and agency to evaluate and compare policies affecting their treatment in Australia in the period from 1973 to 1996 with the period since 1996.

Context: The treatment of migrant workers in Australia prior to 1973

Our analysis of the power and agency of migrant workers in Australia under different policy regimes focuses on the period since 1973. We have selected this starting point because 1973 marked the establishment of a dedicated ‘skilled’ immigration programme following the formal abolition of the White Australia policy (Reference TavanTavan, 2004). In order to contextualise our analysis, this section examines the power and agency of migrant workers prior to 1973.

Following British invasion in 1788, colonial governments in Australia sought to increase their populations and workforces through the migration of convict labour and of free settlers attracted by financial incentives (Reference BlaineyBlainey, 1975). In the latter decades of the 19th century, employers actively utilised and supported the colonial governments’ initiatives to increase the pool of migrant labour, such as assisted passages for free settlers and the importation of Pacific Islanders to work in the plantation industries (Reference CastlesCastles, 1988). Unions resisted such efforts, fearful that migrant labour would undermine their collective power and hold down wages (Reference VastaVasta, 2005).

After the colonies federated to form the Commonwealth of Australia in 1901, workers were provided fair minimum wages, enshrined by the Harvester Judgement of 1907, Footnote 2 which the manufacturing industry accepted in return for tariff protection. A highly restrictive and racist immigration policy regime provided additional institutional support for the wage system since it maintained scarcity of labour supply (Reference CastlesCastles, 1988). Economic arguments were not the sole basis of support for the strict control of migrant labour that characterised Australian immigration policy for the first half of the 20th century. This policy was underpinned by the White Australia policy, as set out in the Immigration Restriction Act 1901, which reflected racist attitudes within the union movement and across broader society and a desire to preserve the legacy of British colonialism in the visible appearance of Australia’s workforce (Reference FitzpatrickFitzpatrick, 1940). Its implementation ‘ensured that, with very few exceptions, non-whites would not be permitted to settle, work, or live temporarily or permanently in Australia’ (Reference HawkinsHawkins, 1991: 14).

The Contract Immigrants Act 1905 served as a further mechanism for the control of foreign labour by specifying that employers could only engage foreign workers of any race or nationality (including Britons) if they could prove no Australian worker was able to fill the position. Moreover, it specified that foreign nationals had to be employed according to legal minimum wages and conditions, as specified in the relevant award, and could not be used to break industrial disputes. While fundamentally racist, these laws were also universalist in their application to workers within the Australian labour market (Reference CrockCrock, 1998; Reference Mitchell, Arup and HoweMitchell et al., 2001). The few foreign nationals able to immigrate in the post-federation decades were not cast off to a secondary labour market, but enjoyed the same wage rates, working rights and benefits as Australian citizens. According to Reference Watson, Buchanan and CampbellWatson et al. (2003), immigrants faced neither ‘economic marginalisation nor social exclusion’ (p. 14).

The Chifley Labor government of 1945 to 1949 sought to expand the immigration intake significantly, a mission continued by Coalition governments from 1949 to 1972, in order to improve Australia’s industrial and defence capabilities. The relaxation of immigration controls helped to provide labour for major public works projects such as the Snowy River Scheme and the burgeoning and generally highly unionised automotive and ship manufacturing, coal, steel and timber industries (Reference Holton, Sloan, Wooden, Holton and HugoHolton and Sloan, 1994; Reference Quinlan and Lever-TracyQuinlan and Lever-Tracy, 1988).

Between 1947 and 1953, around 170,000 people came to Australia from war-torn Europe under the Displaced Persons Program. Displaced persons were obliged to undertake a 2-year employment contract in an unskilled job at a prescribed location, conditions that other migrants and citizens were not subject to (Reference CollinsCollins, 1988). These restrictions did not apply to workers who arrived in the late 1950s and 1960s, who worked primarily in higher-skilled and intermediate-skilled jobs (Reference SalterSalter, 1978). Many of these workers arrived via bilateral migration agreements with various European nations and were generally selected according to their likelihood of productive employment (Reference JuppJupp, 2007). However, there continued to be racialised preferences in immigration selection (Reference CollinsCollins, 1988).

The post-war expansion of the immigration intake required the creation of a bureaucracy to determine the necessary number of migrant workers and the particular industries and occupations where they were needed. These matters were administered by the new Ministry of Immigration (now the Department of Home Affairs), which established tripartite advisory councils to identify labour market needs and build consensus among employers and workers (Reference SalterSalter, 1978). The government used the advisory councils to make a case that increased immigration to address labour shortages would not negatively impact on overall wages and unemployment. This successfully allayed the fears of unions which had high levels of membership density across the workforce and strong powers to enforce labour standards (Reference Goodwin and MaconachieGoodwin and Maconachie, 2007; Reference VastaVasta, 2005). Unions’ concerns were further placated by the prominent role they were granted at the centre of the conciliation and arbitration system, setting decent award wages and conditions and enforcing them through rights to enter workplaces, to inspect employer records and to take industrial action (Reference Clibborn and WrightClibborn and Wright, 2018). This system of arbitral protections gave unions influence in their representation, regulation and enforcement activities among migrant workers (Reference Quinlan and Lever-TracyQuinlan and Lever-Tracy, 1988). According to Reference Quinlan and Lever-TracyQuinlan and Lever-Tracy (1990: 161), this ‘restricted the capacity of employers to use immigrants as a ‘super exploitable’ category of labour. This formed the cornerstone of union acceptance of mass immigration after 1945 and of their growing tolerance towards non-European workers’ (see also Reference O’Donnell and MitchellO’Donnell and Mitchell, 2000).

Using the framework of criteria influencing migrant workers’ bargaining power and agency, Australia’s immigration policies from 1953 (when the Displaced Persons Programme ended) to 1972 provided migrants with permanent residency status, free mobility within the labour market, an intermediate skill threshold and high institutional protection through the conciliation and arbitration system and strong unions that enforced award provisions. While the policy regime of immigration selection was fundamentally racist, those allowed to migrate during this period had moderately high bargaining power and agency, in contrast to migrant workers employed under the post-war European guest-worker programmes (Reference CastlesCastles, 1986). This was strengthened with the introduction of a formal non-racially discriminatory policy of permanent skilled immigration after 1973.

The treatment of migrant workers from 1973 to 1996

From the early 1970s, race and nationality ceased to be the principal foundations for immigration selection policy: the White Australia policy was formally abolished and employment-related criteria were given more prominence (Reference TavanTavan, 2004). Under the Structured Selection Assessment System introduced by the Whitlam Labor government in 1973, applicants were awarded ‘points’ for possessing employment-based criteria (Reference HawkinsHawkins, 1991). The Fraser Coalition government made further reforms in 1979 through the introduction of the Numerical Assessment Scheme, which created two broad visa categories: ‘skilled’ and ‘family’ (Reference JuppJupp, 2007). For skilled visas, preference was given to applicants with tertiary-level qualifications and English language ability and high likelihood of job attainment. In 1981, the skilled immigration programme was split into Occupations in Demand and Employment Nominees visas (Reference BirrellBirrell, 1984). Under the Hawke Labor government first elected in 1983, selection criteria for skilled visas were weighted more heavily towards factors such as qualifications, youth and English language competency. Employers wanting to sponsor immigrants on an Employment Nominees skilled visa had to show proof that no resident workers were available and that they had devoted sufficient resources to training (Reference CrockCrock, 1998). In 1989, further reforms were made to immigration selection policy. An adjustable pass mark for skilled visas was established, enabling intake levels to be easily raised or lowered through changes to points thresholds, thereby giving the government greater control over the size of the annual immigration programme (Reference BirrellBirrell, 1998).

The 1989 reforms directly followed recommendations of the Committee to Advise on Australia’s Immigration Policies (1988), which the Hawke government commissioned. The Committee’s report was highly critical of the priority given to family connections over skill-based criteria in immigration selection, which had led annual immigration intakes to be dominated by family over skilled visas for much of the 1980s, and called for a greater focus on skills and entrepreneurship. Employer groups were muted in their advocacy for higher intakes of skilled visas during this period, largely because economic stagnation diminished demand for migrant labour. Although unions sought training of local workers as the main policy response for addressing skills needs, they remained supportive of immigration as part of the solution to skills shortages. This support rested upon the continued effectiveness of the conciliation and arbitration system in protecting migrant workers and enforcing award standards (Reference Parkin, Hardcastle, Parkin, Summers and WoodwardParkin and Hardcastle, 1994).

There remained minimal scope for temporary migration during this period. The exceptions were visa categories for tourists, students and ‘temporary residents’. The latter of these permitted the temporary entry of various types of skilled workers, but only small numbers of executives and those with highly specialised qualifications. From 1987–1988 to 1991–1992, a total of 22,700 temporary skilled resident visas were issued per year on average to primary applicants (Reference Baker, Sloan and RobertsonBaker et al., 1994). Employers could also collectively sponsor groups of migrant workers on a temporary basis through a Labour Agreement, but only if the Commonwealth government and relevant unions formally agreed that no resident workers were available to undertake the required tasks (Reference CrockCrock, 2001). Other temporary visas such as the working holiday visa and the student visa provided limited work rights. Nonetheless, the focus was overwhelmingly on permanent skilled immigration. According to Reference Markus, Jupp and McDonaldMarkus et al. (2009),

the fundamental premise of Australian immigration policy until the 1990s was that those admitted to Australia came as permanent residents, enjoying the same rights and privileges and with the same obligations as the Australian-born. There was a conscious rejection of the ‘guest-worker’ programs which developed in postwar Europe. (p. 9)

This period saw a series of wider changes to economic and labour market policy with implications for immigration policy. The opening of the Australian economy through tariff reduction by the Whitlam Labor government in 1973 and further trade liberalisation by the Hawke and Keating Labor governments between 1983 and 1996 led to agitation from industry and economic policymakers for greater wage and labour market flexibility. This precipitated several waves of labour market deregulation, which led to the introduction of enterprise bargaining in the early 1990s and further changes to industrial relations policy after 1996, including a weakening of the role that unions had previously performed in representing workers and enforcing minimum standards. These changes undermined the conciliation and arbitration and award systems and contributed to declining union membership, which eroded institutional protections for all workers (Reference Cooper and EllemCooper and Ellem, 2008). Employers would later seek greater flexibility not only through further labour market deregulation but also through liberalisation of visa rules to make it easier to hire migrant workers (Reference WrightWright, 2012), as we discuss below. However, industrial relations and immigration policy arrangements designed to protect migrant workers that were consolidated in the immediate post-war decades and strengthened after 1973 largely remained in place until 1996.

To summarise, migrant workers’ bargaining power and agency in Australia was high between 1973 and 1996. The immigration system remained focused almost exclusively on permanent residency and migrant workers had free mobility within the labour market. Applicants needed a high level of qualifications to obtain a skilled visa, and institutional protections remained strong by virtue of the equalising effects of the conciliation and arbitration and award systems.

The treatment of migrant workers since 1996

Since 1996 there have been significant changes to policies pertaining to migrant labour. The foundations of these changes were laid by the Howard Coalition government, which introduced new temporary skilled visas and made changes to other temporary visas. The Howard government oversaw reform and expansion of permanent skilled visas, which was achieved in large part by making it easier for temporary visa holders to gain permanent residency. Subsequent governments maintained and extended these changes to temporary visa policy, but at the same time have weakened pathways between temporary and permanent visas. Before we examine the impact of these changes on migrant workers’ bargaining power and agency, the main elements of policy reform since 1996 will be outlined.

Permanent skilled visas

The Howard government introduced several changes in 1999, 2001 and 2005, which had the effect of significantly increasing the permanent skilled immigration intake. For the skilled Independent visa regulated by a points test, applicants were given additional points if they had Australian tertiary qualifications, local work experience in shortage professions, or language proficiency, or if their spouse possessed certain skills. Changes were also made to the Employer Nomination Scheme, including the weakening of labour market testing obligations and eligibility requirements and the creation of occupation lists that allowed employers to more easily sponsor applicants who possessed skills identified as being in shortage. A key element of these reforms was the strengthening of pathways between different types of visas, which made it easier for temporary visa holders residing in Australia to apply successfully for permanent visas (Reference WrightWright, 2015). Temporary–permanent visa pathways were consolidated by the Howard government’s creation and expansion of various temporary visa schemes (Reference Gregory, Chiswick and MillerGregory, 2015). While changes introduced after 1996 improved the likelihood of permanent visa holders gaining employment, they negatively impacted these migrants’ likelihood of holding onto a ‘good’ job that utilised their qualifications (Reference Junankar and MahuteauJunankar and Mahuteau, 2005). Nevertheless, there have been relatively few reported cases of exploitation among permanent skilled migrants since 1996.

Temporary skilled visas

While Australian immigration policy focused almost exclusively on permanent settlement prior to the election of the Howard government, in 1996, a new temporary skilled visa, called the 457 visa, was established, which operated on the basis of employer sponsorship. In contrast to permanent skilled visa grants regulated by an annual quota set by ministerial decree, the 457 visa intake was determined exclusively by employer demand. The 457 visa was introduced following the independent Roach Review commissioned by the Keating Labor government in 1995 and whose recommendations the Howard government subsequently adopted. The removal of labour market testing requirements set the 457 visa apart from the temporary skilled visa schemes that existed prior to 1996 which, as mentioned above, only allowed for small intakes. The Roach Review reasoned that removing labour market testing would allow for greater ‘procedural simplicity’ and business efficiency, particularly for multinational service firms seeking to transfer professional and managerial staff from their operations abroad to operations in Australia. However, it cautioned that the temporary visa should only be open to high-skilled workers with high agency and minimal vulnerability to exploitation and whose engagement would not erode existing labour standards:

The new arrangements are not meant to apply to the traditional skills trades or to professionals like nursing and teaching. Furthermore, policies and procedures for facilitating the entry of key business personnel must not provide an avenue for the recruitment of unskilled or semi-skilled workers, or the channelling of overseas workers into low paid or low skilled work … Wages and employment conditions meet accepted Australian standards. (Roach Review, 1995: 1.11)

However, subsequent reforms to the 457 visa failed to heed these warnings. In 2001, the minimum skill thresholds for sponsoring workers under the scheme were lowered and various exemptions for minimum salary requirements were introduced for employers located outside of the largest cities. These changes effectively transformed the 457 visa from a high-skilled to an intermediate-skilled scheme (Reference Campbell and ThamCampbell and Tham, 2013).

Reports of 457 visa holders being underpaid and mistreated emerged in the early 2000s and escalated in 2006 following the Howard government’s Work Choices legislation that abolished compulsory arbitration and significantly curtailed the ability of unions to represent workers and enforce minimum standards. Unions claimed these changes left visa holders more vulnerable to exploitation. Reports of 457 visa holders being underpaid increased during this period and were concentrated among intermediate-skilled workers in industries with low levels of union representation, such as hospitality and residential construction (Reference Toh and QuinlanToh and Quinlan, 2009; Reference VelayuthamVelayutham, 2013).

When the Rudd Labor government came to office in 2007, it commissioned the independent Deegan Review of the 457 scheme and subsequently implemented several of the review’s recommendations (Reference Campbell and ThamCampbell and Tham, 2013). In 2008 and 2009, the government expanded the powers of its labour inspectorate, the Fair Work Ombudsman (FWO), to monitor and investigate possible non-compliance by employer sponsors, introduced penalties for employers found in breach of their obligations and increased the minimum salary requirements for visa holders. In 2013, the Rudd government acted upon another recommendation of the Deegan Review by extending from 28 days to 90 days the period for a 457 visa holder to find another sponsor if their employment relationship ceased. According to the Deegan Review, 28 days did not provide migrant workers with sufficient mobility to escape from exploitative employment relationships (Deegan Review, 2008). However, in 2016, the Turnbull Coalition government reduced the period to find an alternative employer to 60 days based on reasoning that this would increase employment opportunities for local workers (Minister for Home Affairs, 2016).

In 2018, reforms were made to the temporary skilled visa scheme, which was renamed the 482 visa and split into a 2-year ‘short-term’ stream focusing mainly on intermediate-skilled occupations and a 4-year ‘medium and long-term’ stream focusing primarily on high-skilled occupations. Whereas the 457 visa gave all visa holders the opportunity to apply for permanent residency, under the 482 visa, this possibility is now available only to workers sponsored for occupations eligible under the ‘medium- and long-term’ stream. Workers sponsored under the ‘short-term’ stream essentially have no opportunity to convert from temporary residency status thus potentially diminishing their agency and bargaining power (Reference Wright and ConstantinWright and Constantin, 2020). Removing the pathway to permanent residency has transformed the short-term stream of the 482 visa into a guest-worker visa. The safeguards that existed when the 457 visa was first introduced in 1996 to ensure that migrant workers retained their agency and bargaining power have thus been whittled away by successive policy changes. However, compared to other temporary visas, there have been relatively few reported cases of temporary skilled visa holders having their rights violated. Where such instances occurred, they were disproportionately in occupations characterised by intermediate skills and low levels of union membership (Reference BoucherBoucher, 2019).

Working holiday maker visas

While there has been much attention in policy discussion and academic research to temporary skilled visas, there have also been important changes to other temporary work visas. The Working Holiday Maker (WHM) scheme was established in 1975 to promote cultural exchange. This remains the scheme’s explicit objective, but successive incremental policy changes since the late 1990s have effectively turned the WHM into a de facto low-skilled work visa. The WHM scheme, which now consists of the Working Holiday 417 visa and the Work and Holiday 462 visa, originally permitted a limited number of 18- to 25-year-olds from three countries (Reference Tan, Richardson and LesterTan et al., 2009), whose entry was regulated by an annual quota, ‘to have an extended holiday in Australia by supplementing their travel funds through incidental employment’ (Department of Immigration and Multicultural Affairs, 2007: 6). However, changes since 1996 have fundamentally transformed this scheme.

Soon after it was first elected, the Howard government raised the WHM scheme intake quota and increased the maximum eligibility age to 30 years. Subsequently, the intake quota was abolished for the 417 visa, though it remains in place for the 462 visa. New bilateral agreements were also established with several dozen additional migrant sending countries (Reference Reilly, Howe and van den BroekReilly et al., 2018; Reference Tan, Richardson and LesterTan et al., 2009). A significant change occurred in November 2005, when a second-year extension was made available for any WHM visa holder who worked in the horticulture sector in a regional area for 88 days during the initial 1-year visa term. In July 2006, the second-year visa extension was permitted for WHM visa holders who had worked for 88 days in any primary industry and the maximum time visa holders could work for a single employer was increased from 3 to 6 months (Reference Reilly, Howe and van den BroekReilly et al., 2018; Reference Wright and ClibbornWright and Clibborn, 2017). Further changes were made in 2018 and 2019: a third-year visa extension was introduced for visa holders who undertake 6 months of ‘specified work in a specified regional area’ in their second year; the maximum period that visa holders could work for a single employer was extended to 12 months; annual quotas for 462 visa holders were increased; and the maximum eligible age for visa holders from certain countries was extended to 35 years (Department of Home Affairs, 2018a).

These changes have transformed the function of the WHM scheme. The intake of WHM visa holders has increased more than fivefold from 40,273 in 1995–1996 to 210,456 in 2017–2018 (Department of Home Affairs, 2018b; Reference Reilly, Howe and van den BroekReilly et al., 2018). Visa extension rules channel significant numbers of WHM visa holders into work in the horticulture industry. Unlike temporary skilled visas, work performed by WHMs is not monitored by the state other than vetting applications for visa extensions. Given the unregulated nature of this working visa, accurate quantification of work performed by WHMs is not possible. However, it is clear that many perform work in horticulture with 32,062 second-year extensions granted to WHMs in 2018 alone (Department of Home Affairs, 2018b: 41). WHM visa holders are not tied to any one employer. However, forms of employer documentation, such as pay slips, are required to support applications for second- and third-year visa extensions. This creates dependent relationships that can limit some workers’ mobility and likelihood of reporting employer breaches of employment laws, and therefore the practical availability of institutional protections (Reference ClibbornClibborn, 2019; FWO, 2016). WHM visa holders potentially possess skilled qualifications; however, the inducement of the second- and third-year visa extensions confine many to low-skill jobs such as picking, packing or grading horticulture produce during their work towards those extensions (Reference Howe, Clibborn and ReillyHowe et al., 2019).

International student visas

Australia has been a destination for international students on temporary visas since the Colombo Plan was established in 1951 (Reference Markus, Jupp and McDonaldMarkus et al., 2009). International students are allowed to work up to 40 hours per fortnight during teaching periods and unrestricted hours outside of these periods. For many years, they have been ‘generally prepared to undertake low skilled and low paid work’ (Reference Sloan and KennedySloan and Kennedy, 1992: 777). Small enrolment numbers limited international students’ participation in the labour market prior to the 1990s. However, in the period since, international student intakes have expanded significantly. The number of international student visas granted increased over 17-fold, from around 20,000 in 1986–1987 to 354,594 in 2018–2019, including 189,477 to university students (Department of Home Affairs, 2019a; Reference HugoHugo, 2004). Several factors have contributed to this increase, including the abovementioned pathways created through various policy changes between the late 1990s and late 2000s that made it easier for students to gain temporary work visas (such as the Temporary Graduate 485 visa) and apply for permanent residency after the completion of their studies (Reference Gregory, Chiswick and MillerGregory, 2015).

The prospect of a permanent visa has been identified as an important factor attracting international students into universities and vocational training colleges (Reference Toner, Cahill and TonerToner, 2018). According to a review commissioned by the Commonwealth government, this prospect ‘resulted in some [education] providers and their agents being interested in “selling” a migration outcome to respond to the demand from some students to “buy” a migration outcome’ (Reference BairdBaird, 2010: 7). Also important are changes to the funding of the vocational training and tertiary education sectors. Government funding decline since the 1990s prompted education providers to seek alternative funding sources, including through increased enrolments of full-fee paying international students, which in recent years has been the largest source of revenue growth for universities (Reference Ferguson and SherrellFerguson and Sherrell, 2019).

International student visas currently allow up to five years temporary residency in Australia subject to meeting several conditions such as maintaining enrolment and satisfactory attendance in a registered course of study (Department of Home Affairs, n.d.-b). Student visa holders may undertake paid work in Australia once their studies have commenced and they technically enjoy complete mobility between employers. However, like WHMs, their options are constrained by the practical application of rights. Those enrolled in coursework studies are limited to working a maximum of 40 hours per fortnight (Department of Home Affairs, n.d.-a), by the geographical location of their studies and by difficulties obtaining jobs in the formal labour market that comply with employment laws (Reference ClibbornClibborn, 2018). Some international students have also reported fear of deportation for technical breaches of the 40-hour restriction if they report their employers for providing sub-legal wages and conditions (Reference ReillyReilly, 2012; Senate Education and Employment References Committee, 2016). These restrictions have resulted in limited mobility for international student visa holders (Howe, 2019). While many international students already possess qualifications and all are evidently working towards formal qualifications, their constrained access to ‘legal’ jobs renders many unable to utilise those skills in their work in Australia and are instead channelled towards low-skill jobs such as in hospitality and retail.

Other work visas

The Seasonal Worker Programme (SWP) was created, like the WHM’s second- and third-year visa extensions, to increase the supply of labour to the horticulture sector. Also like the WHM programme, the SWP has a primary purpose other than work, in this case foreign aid. Introduced in 2008 by the Rudd Labor government, and formally launched in 2012 after a pilot programme, the current SWP programme allows approved employers to sponsor workers from the Pacific and Timor-Leste to work in Australia’s horticulture sector and, in some locations, the accommodation sector, for up to 9 months. The programme remains small as a proportion of all migrant workers in horticulture, but growing in the total number of workers from 1473 in 2012–2013 to 12,200 in 2018–2019 (Reference Dufty, Martin and ZhaoDufty et al., 2019). SWP visa holders do not have the benefit of mobility as they are tied to their sponsoring employer. However, there is some institutional support through site visits and audits from the Department of Employment, Skills, Small and Family Business that administers the programme and monitoring by the FWO. Employers can lose their right to sponsor SWP visa holders if they breach employment laws. Some research has found the programme working positively for SWP visa holders who can send valuable remittances to their home countries (Reference Doyle and HowesDoyle and Howes, 2015). However, other research has identified practical difficulties for workers in accessing institutional support due to their dependence on employers and fear of losing ongoing work in Australia, allowing excessive deductions from wages for accommodation and transport (Reference Howe, Clibborn and ReillyHowe et al., 2019).

In November 2016, the Turnbull Coalition government introduced several new visas with work rights, including the Temporary Work (Short-Stay Specialist) 400 visas, the Training 407 visa and the Temporary Activity 408 visa. Some of these new visas consolidated several existing smaller visas. While it appears the government made no formal announcement regarding these schemes upon their introduction, over 100,000 visas holders were permitted entry under these schemes combined in 2017–2018 (Department of Home Affairs, 2019). Workers on these visas are often channelled into high-skilled work requiring formal qualifications, but their bargaining power and agency is constrained. While the conditions of these visas vary somewhat, in general, visa holders are confined to work with their sponsoring employer, have restricted capacity to apply for other visas or permanent residency and have limited access to union representation. These factors seem to contribute to reported cases of workers under these schemes being underpaid and exploited (e.g. Reference Hunter and BagshawHunter and Bagshaw, 2017; Reference PattyPatty, 2019).

Discussion

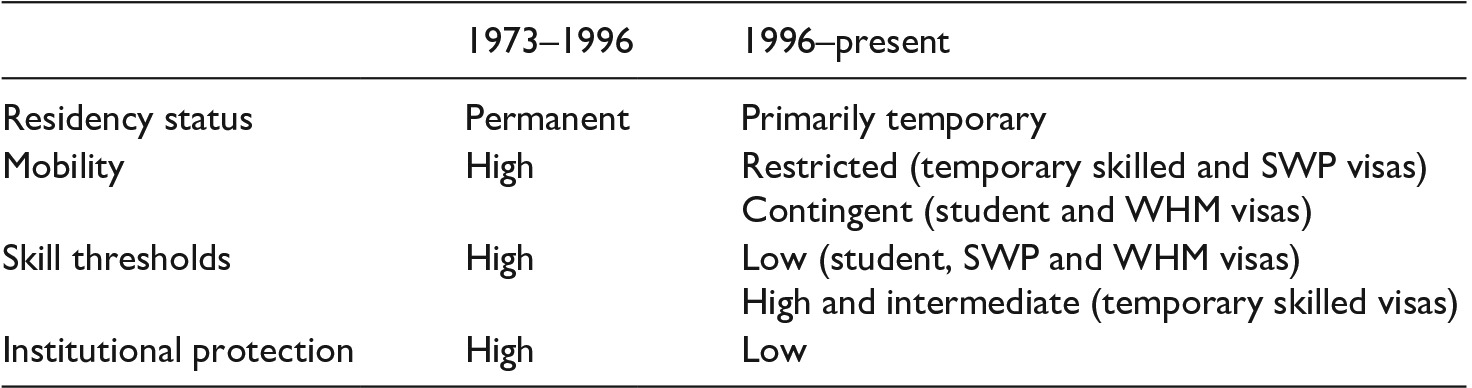

In this section, we return to the framework of four criteria affecting migrant workers’ bargaining power and agency – residency status, mobility, skill thresholds and institutional protections – to evaluate and compare the migrant labour policy regime in place from 1973 to 1996 with the one that has emerged since 1996. Our findings are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. An assessment of Australian labour immigration policy 1973–1996 and 1996–present on four criteria of migrant worker power and agency.

SWP: Seasonal Worker Programme; WHM: Working Holiday Maker.

Residency status

The almost exclusive focus on permanent visas from 1973 to 1996 accompanied by an effective system of labour standards enforcement meant that migrant workers enjoyed the same social and employment rights and entitlements as Australian citizens. With the creation and expansion of temporary visa schemes after 1996, temporary migrants initially had the opportunity to apply for permanent residency with a reasonable expectation that this would be granted so long as they fulfilled standard eligibility requirements. However, more recent policy changes, such as the creation of the temporary skilled visa short-term stream, have removed this opportunity for some visa holders.

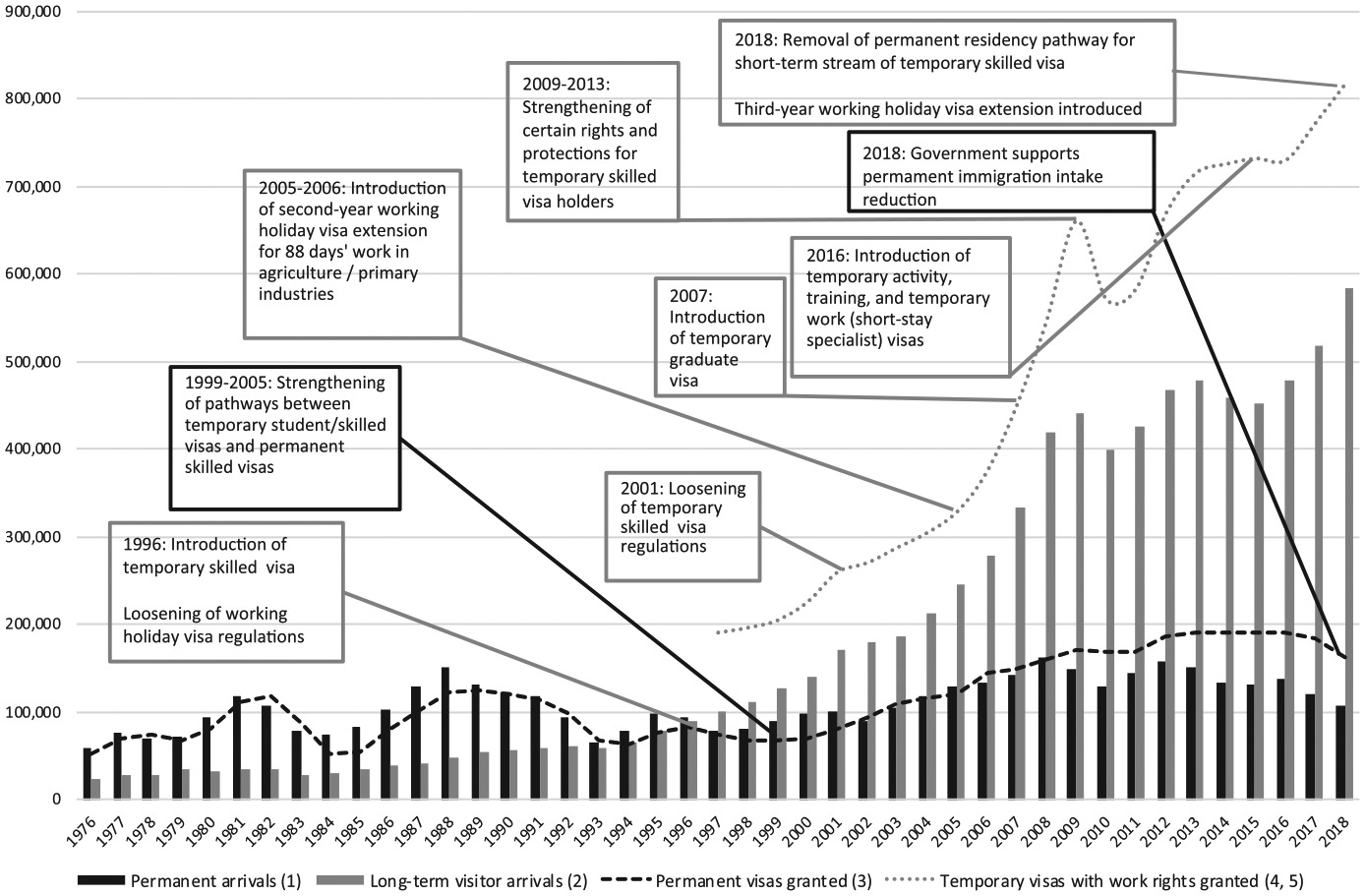

Furthermore, in every year from 1976 to 1996, ‘permanent arrivals’ consisting of foreign nationals eligible to settle permanently in Australia outnumbered ‘long-term visitor arrivals’, that is, foreign nationals intending to live in Australia for at least 12 months, but not permanently (see Figure 1). This latter category includes temporary skilled, WHM and international student visa holders, but not tourists. By contrast, long-term visitor arrivals have outnumbered permanent arrivals in every year since 1997. In 2018, the 583,300 long-term visitors arriving in Australia outnumbered the 107,670 permanent arrivals by more than fivefold. These trends mirror the large increase in temporary visas with work rights granted from 191,068 in 1996 to 816,719 in 2018. Permanent visa grants have also increased over the period but not by the same magnitude.

Figure 1. Permanent and long-term arrivals and permanent and temporary labour immigration intakes and associated policy decisions, 1976–2018.

Sources: (1) Permanent arrivals and (2) long-term visitor arrivals from Australian Bureau of Statistics (2019); (3) permanent visa intakes from the Department of Home Affairs (2019b); (4) temporary visa intakes 1996–2009 from the Department of Home Affairs (various sources). Includes student, working holiday and temporary skilled visas; (5) temporary visa intakes 2009–2019 from the Department of Home Affairs (2019a). Includes student, working holiday maker, temporary skilled, temporary activity, temporary graduate, temporary work (short-stay specialist) and training visas. Does not include other visas including Special Category visas available to New Zealand citizens.

Year reported is for data for the financial year ending (e.g. 2018 is 2017–2018 data).

The large gap between temporary work and permanent visa grants reflects the erosion of the temporary-permanent migration pathway, as indicated in the rapid rise of migrants on ‘bridging visas’ waiting for their visa applications to be decided, due to processing delays. This can create significant vulnerability for temporary migrants on the long yet uncertain journey to permanent residency (Reference Robertson and RunganaikalooRobertson and Runganaikaloo, 2014). According to Reference SherrellSherrell (2019), between 2013 and 2018, the number of people who had been on temporary visas for eight or more years increased threefold. This gives credence to the claim that Australia is creating ‘a permanent class of temporary visa holders who are at all times extremely vulnerable’ (Reference CarrCarr, 2017). Temporary migrants in Australia are denied or have restricted or conditional access to many of the rights and protections that citizens are entitled to, such as protection of income in the event of workplace injury, recovery of unpaid entitlements when their employer goes into administration, and subsidised health care, education and unemployment benefits. There are also high costs associated with obtaining temporary visas (Reference MaresMares, 2016). As studies in other countries have found, the denial of such protections to migrant workers with temporary residency can weaken their bargaining power and agency relative to those with permanent residency (Reference BauderBauder, 2008; Reference Dauvergne and MarsdenDauvergne and Marsden, 2014).

Mobility

A feature of permanent migration in Australia is the right of visa holders, like citizens, to move freely between employers. From 1973 to 1996, when immigration policy was built almost exclusively upon the principle of permanent residency, migrant workers could leave their employer in the event they were being mistreated or if they could receive better wages and conditions or utilise their skills more effectively with another employer.

By contrast, under temporary visas that have been created or expanded since 1996, migrant workers’ mobility is restricted or conditional. Workers on temporary skilled, SWP and training visas have their residency rights tied to their employer sponsor; if the employment relationship with their sponsor ceases, they have a short timeframe to find another sponsor or face deportation. While international student and WHM visa holders are free to move between employers, there is a risk of employers reporting technical breaches for exceeding working hour limitations in the case of international students, and withholding documentation required for WHM applicants to gain visa extensions.

In support of international scholarship suggesting that constraining migrants’ mobility can diminish their power and agency (Reference Cangiano and WalshCangiano and Walsh, 2014; Reference ZouZou, 2015), Australian studies have identified such constraints as an important factor contributing to temporary migrant workers’ vulnerability to underpayment and other forms of mistreatment (e.g. Reference Howe, Clibborn and ReillyHowe et al., 2019; Reference ReillyReilly, 2012; Reference VelayuthamVelayutham, 2013).

Skill thresholds

Like other groups of workers, migrant workers’ skills and qualifications can influence their bargaining power with employers to negotiate good wages and conditions and their agency to move between employers. High-skilled migrants with scarce qualifications and experience tend to have stronger bargaining power and agency than lower skilled migrants who can be replaced more easily and may therefore be more tolerant of poor working conditions (Reference AndersonAnderson, 2010; Reference DauvergneDauvergne, 2016; Reference WalshWalsh, 2014). These findings are reflected in our analysis of the skill thresholds under labour immigration policy regimes in Australia.

From 1973 to 1996, Australian labour immigration policy focused solely on skilled immigration. This meant that foreign nationals seeking work visas were required to possess tertiary qualifications and skills in high demand. This did not preclude migrants from working in lower skilled occupations, which was an outcome for migrants facing challenges getting their skills recognised upon arrival (Reference GroutsisGroutsis, 2003). But it meant they had the required qualifications and experience to gain employment in high-skilled work once skill recognition was achieved.

Since 1996, the qualifications threshold for permanent skilled visas has remained high. This was initially the case for the temporary skilled visa, but reforms after 2001 expanded eligibility of this scheme to a large number of intermediate-skilled occupations not requiring university-level qualifications. Cases involving underpayment of temporary skilled visa holders disproportionately involve workers in such occupations, such as cooks and builders’ labourers (Reference BoucherBoucher, 2019). The expansion of international student visa intakes and changes to the WHM visa have encouraged large numbers of temporary migrants into low-skilled work in the hospitality, retail and horticulture industries. Perceptions by these workers that they are easily replaceable, which is a consequence of the low barriers to entry for these occupations, is a factor contributing to widescale underpayment of temporary migrant workers in these industries (Reference ClibbornClibborn, 2018).

Institutional protection

Labour market regulation is an important factor determining the extent to which migrant workers’ bargaining power and agency is supported. In particular, previous scholarship has highlighted the role of trade unions and government inspectorates in institutionalising protections by establishing and enforcing decent labour standards. The absence of such institutional protections can allow employers to pay migrant workers below these standards to gain a competitive advantage (Reference Afonso and DevittAfonso and Devitt, 2016; Reference McGovernMcGovern, 2007; Reference ZouZou, 2015).

From 1973 to 1996, institutional protections for migrant workers were strong. The conciliation and arbitration and award systems provided relatively standardised wages and conditions for workers. An effective labour standards enforcement regime supported by strong unions helped to ensure that workers received the wages and conditions they were entitled to under the relevant industry or occupational awards (Reference Goodwin and MaconachieGoodwin and Maconachie, 2007; Reference Hardy and HoweHardy and Howe, 2009), including migrant workers (Reference Quinlan and Lever-TracyQuinlan and Lever-Tracy, 1990). The permanent immigration policy buttressed strong institutional protections for migrant workers, who had the same workplace rights and entitlements as Australian citizens.

This scenario has changed since 1996. As Figure 1 illustrates, visa intakes have increased to unprecedented levels with many more migrants working in jobs where enforcement of labour standards is weak. This is the case not only among temporary migrants but also undocumented workers who form a large proportion of the horticulture workforce in certain regions (Reference Howe, Clibborn and ReillyHowe et al., 2019; Reference Underhill and RimmerUnderhill and Rimmer, 2016). While temporary migrants have de jure access to the minimum standards regulated in the relevant awards, there are considerable challenges to enforcing such standards among these workers. Temporary skilled visa holders, international students, and SWP and WHM visa holders are concentrated in industries and organisations with low levels of union representation (Reference ClibbornClibborn, 2018; Department of Immigration and Border Protection, 2014; Reference Howe, Clibborn and ReillyHowe et al., 2019). This has been affected by declining levels of union membership over the past three decades, as well as industrial relations policy changes, especially (but not only) those introduced by the Howard government, which intentionally weakened unions’ role in regulating labour standards (Reference Cooper and EllemCooper and Ellem, 2008). Temporary migrants account for a disproportionate amount of the FWO’s activities, yet the FWO has insufficient resources and faces structural challenges to enforcing labour standards in the parts of the labour market where temporary migrants are concentrated (Reference ClibbornClibborn, 2015; Reference Clibborn and WrightClibborn and Wright, 2018). Consequently, while institutional protections for migrant workers were strong prior to 1996, since then they have weakened considerably.

Conclusion

This article has contributed to emerging scholarship examining how immigration rules can contribute to migrant worker vulnerability (e.g. Reference AndersonAnderson, 2010; Reference Sargeant and TuckerSargeant and Tucker, 2009). In particular, we have used criteria identified in the wider literature on labour immigration to assess the bargaining power and agency conferred upon migrant workers in Australia. Based on our assessment of labour immigration policies relating to migrants’ residency status, mobility, skill thresholds and institutional protections, it is clear that migrant workers arriving in Australia in the 1973 to 1996 period had high levels of bargaining power and agency. This stood in contrast to the labour immigration policies pertaining to the guest-worker schemes of post-war Western Europe, and contemporary examples such as Singapore and the Gulf Coast Council countries, involving the curtailment of migrant workers’ power and agency.

However, since 1996, Australia’s labour immigration policy regime has increasingly resembled a guest-worker policy regime. Temporary migrant labour and long-term visitor arrival intakes have both increased dramatically since this date and, as Figure 1 above indicates, these trends have been driven by the policy changes of successive governments. When temporary visas were first introduced and expanded in the late 1990s, the process was done cautiously in order to ensure that temporary migrant workers were treated fairly and in accordance with minimum legal standards. Pronouncements by senior ministers and advisers indicated that Australian governments were determined to avoid outcomes associated with guest-worker schemes, such as exploitation, labour market segmentation and the creation of a permanent class of temporary visa holders. However, such caution has been either forgotten or thrown to the wind by recent governments, including the incumbent government which has presided over policy changes that have further increased temporary work visa intakes, while at the same time explicitly seeking to reduce permanent immigration.

Decisions by recent governments to increase temporary immigration without strengthening the underlying institutional protections threatens to further deteriorate the already weak power of temporary migrant workers in Australia. Our comparison of the 1973–1996 period with the post-1996 period indicates that migrant workers on permanent visas were – and still are – much less at risk of underpayment and other forms of mistreatment and marginalisation than temporary visa holders. Australia’s post-war system of permanent migration that existed until 1996 involved ‘the more or less unproblematic incorporation of immigrant labour into existing regulatory structures’ (Reference O’Donnell and MitchellO’Donnell and Mitchell, 2000: 2). The foundation of permanent residency was a key reason why an expansive immigration policy was embraced in Australia and other countries such as Canada, in contrast to Western European countries with guest-worker programmes where public support for large immigration intakes was much weaker (Reference Hollifield, Martin and OrreniusHollifield et al., 2014).

Despite recent reports arguing that Australia’s temporary visa system is working effectively (CEDA, 2019), our analysis supports other academic studies and policy reports (e.g. Reference Berg and FarbenblumBerg and Farbenblum, 2017; Reference Boucher and DavidsonBoucher and Davidson, 2019; Reference DaleyDaley, 2019; Reference Howe, Clibborn and ReillyHowe et al., 2019) indicating that this system is inadequately protecting migrants in the workplace. Australia’s immigration system increasingly resembles a guest-worker system, where temporary migrants’ rights are restricted, their capacity to bargain for decent working conditions with their employers is curtailed and their agency to pursue opportunities available to citizens and permanent residents is diminished. The ability of temporary migrants in Australia to seek redress if they are underpaid or otherwise mistreated is limited by visa rules that place considerable power in the hands of employers. Like the guest-workers of post-war Western Europe, temporary migrants in Australia ‘constitute a disenfranchised class’ (Reference WalzerWalzer, 1983: 59). The visa rules that allow for differential treatment of temporary migrants compared to other workers in Australia is a fundamental injustice that needs to be rectified. This could be addressed by lifting restrictions on temporary migrants’ pathways to citizenship and labour mobility and removing barriers to effective representation, regulation and enforcement. If such measures are not adopted, Australia may suffer a fate similar to countries with guest-worker schemes where, in many cases, these programmes were shut down because the policies designed to deliver short-term economic benefits inevitably produced unintended consequences and public hostility.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Editor-in-Chief Anne Junor and the Area Editor PN (Raja) Junankar for their guidance and the three anonymous reviewers for their feedback.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This article draws upon research conducted for two projects funded by the Australian Research Council’s Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE170101060 and DE200100243).