In September 2019, 6-year-old Kaia Rolle was listening to her teacher read a story in her Orlando classroom when she was suddenly arrested, placed in the back of a police car, and brought to a juvenile detention center where her mugshot and fingerprints were taken. Earlier that day, the first grader was accused by a teacher of throwing a tantrum in school. In response, Orlando police officer Dennis Turner came to arrest her as she cried and begged him for “a second chance” (Toohey Reference Toohey2020). In officer Turner’s over 20-year career, he had arrested several children before, the youngest of which was 7 years old. At 6 years old, Kaia’s arrest had simply, in his words, “broken the record.” Despite officer Turner’s record, Kaia’s arrest was framed in media outlets as novel. In reality, however, Black girls regularly face a disproportionate level of punishment—through suspensions, expulsions, arrests, and incarcerations—at alarmingly high rates across the USA.

Starting as early as preschool, Black girls—who compose just 20% of the public-school population in the USA—represent nearly half of preschoolers who have experienced one or more suspensions (U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights, 2014). As they enter primary school, Black girls are six times more likely to get suspended compared with white girls and by high school represent 43% of those arrested in school incidents. Once arrested, Black girls are nearly four times more likely than white girls to be incarcerated. These trends also continue into adulthood when Black women are imprisoned at twice the rate of white women (Crenshaw et al. Reference Crenshaw, Ocen and Nanda2014).

Despite the jarring statistics on the punitive experiences of Black girls, there is little political science research that investigates the public attitudes that might make such treatment by educational and criminal justice systems possible. Most of the research documenting the punishment of Black girls is located in the field of education and largely focuses on how classroom policies shape their punitive experiences (e.g., Morris Reference Morris2016). But missing from this work is an examination of the broader public’s role in potentially contributing to Black girls’ punitive experiences as well.

Research in political science has long documented the ways in which stereotypes and social constructions of groups inform how policy benefits and burdens are distributed (Schneider, and Ingram Reference Schneider and Ingram1993; Soss Reference Soss1999), with particular interest in how negative social constructions of Black communities shape their access to benefits like welfare entitlements (Gilens Reference Gilens1996). Yet it is only more recently that the discipline has concertedly turned its attention to examining the punishment that Black communities endure at the hands of what Soss and Weaver (Reference Soss and Weaver2017) call “the second face of the state” (see also, Burch Reference Burch2013; Gottschalk Reference Gottschalk2006; Weaver, Prowse, and Piston Reference Weaver, Prowse and Piston2019). This more recent work, located at the nexus of race, criminal justice, and public opinion research, does the important work of centering the lived experiences of Black communities that face disproportionate levels of punishment, surveillance, and predation via the criminal justice system. But it is also, thus far, centrally focused on investigating the punishment of Black men or, at a more aggregated level, Black communities (e.g., Enns Reference Enns2016; Peffley, and Hurwitz Reference Peffley and Hurwitz2010). This may come as little surprise; many of our national headlines report on the regularized punishment and killing of Black men at the hands of state institutions like the police and prisons. But in doing so, we can lose sight of the distinctive punitive experiences borne by Black women and girls, and the ways that public attitudes and policy on punishment in America are not only racialized, but gendered.

Accordingly, this paper seeks to link scholarly conversations on public attitudes toward Black girls taking place in gender and education research with those on public support for punishment and punitive policy occurring in political science research. In doing so, we argue that how the public sees Black girls matters for how they are treated from a policy and institutional perspective. This study uses original experimental and observational survey data to investigate the stereotypes that undergird public attitudes toward Black girls and connects them with evidence of support for their disproportionate punishment. First, we expand on the existing literature on race and gender in educational settings and provide evidence of the adultification of Black girls among the public: using responses to an experimental vignette, we find that Black girls are seen as acting older than their age, more dangerous, and more experienced with sex than their peers. Second, in an important extension, we demonstrate that respondents who share these adultification perceptions are more likely to support the harsh punishments of Black girls compared to their peers. Finally, we find that negative stereotypical attitudes about Black girls are associated with support for harsh punishment both in general school policy and specific real-world incidents reported in the news.

Together, these findings help to draw the empirical link between the racial and gender stereotypes that shape public perceptions of Black girls and support for their disproportionate punishment. They also, ultimately, emphasize the importance of understanding the intersectional nature of racialized and gendered public attitudes on punishment in America. Our findings uncover the ways in which racialized and gendered stereotypes combine to produce a distinct set of punitive experiences for Black girls—experiences that look different from those experienced by white girls, white boys, and Black boys. The next section will engage in a brief examination of the research on stereotypes shaping Black women’s policy experiences before discussing the specific case of Black girls.

Race-gender stereotypes and public support for punishment

Established political science research on race and policy finds that negative stereotypes often shape public perceptions of Black Americans, particularly Black women (Niemann et al. Reference Niemann, O’Connor and Randall1998; Stephan, and Rosenfield Reference Stephan, Rosenfield and Miller1982; Weitz, and Gordon Reference Weitz and Gordan1993), and that these stereotypes impact their experiences and engagement with public policies (Gilens Reference Gilens1996; Schram et al. Reference Schram, Soss, Fording and Houser2009). Gilens’ (Reference Gilens1996) classic work on welfare attitudes, for instance, finds that Americans’ lack of support for welfare policy is directly related to stereotypes of Black recipients—most of whom are women—as lazy and undeserving. Similarly, Schram et al.’s (Reference Schram, Soss, Fording and Houser2009) study finds that those responsible for welfare distribution are more willing to negatively sanction Black women for engaging in the same behaviors as white women due, in part, to prevailing stereotypes about these groups (see also, Watkins-Hayes Reference Watkins-Hayes2009).

These works on race and policy are clearly related to the policy experiences of Black women. However, many of them do not directly consider the distinctly racialized and gendered experiences of Black women. More typically conceptualized and discussed as an outcome of the analysis, the meaning and importance of the intersectional positionality of Black women, as a doubly marginalized group in terms of race and gender, are often lost in the analysis (Hancock Reference Hancock2007a, Reference Hancock2007b; Simien Reference Simien2005, Reference Simien2007). Established research on intersectionality, however, explains that race and gender are mutually constitutive for Black women (Collins Reference Collins1990, Reference Collins1993; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989). Neither a race nor a gender lens alone can explain their experiences with the political system (e.g., Davis Reference Davis1983). In the criminal justice system, for instance, research finds that Black women experience racialized forms of punishment due to their Blackness while simultaneously experiencing gendered forms of punishment due to their womanhood (Richie Reference Richie2012; Ritchie Reference Ritchie2017). Existing at the intersection of multiple axes of oppression, such as race and gender, can produce distinct experiences within the criminal justice system for Black women—experiences that cannot be easily explained nor understood through only racialized or gendered perspectives.

The intersectional experiences of Black women with punishment are rooted in racist and sexist practices beginning with slavery (George Reference George2015). During slavery, the white American majority justified the sexual exploitation of Black women by developing stereotypes that labeled Black women as seductive, hypersexual, and immoral (also referred to as the “Jezebel” stereotype). As these stereotypes became ingrained in American culture, they created a racialized hierarchy of femininity and sexualization in which white women, understood to be sexually pure and moral, represented the feminine ideal. In contrast, Black women, understood to be sexually promiscuous, represented a deviation. As media and political elites cast Black women as a deviation from the norm, these public perceptions were integrated into policy, particularly punitive policies of “social correction” that use punishment to “fix” the behavior of Black women (George Reference George2015, 102). These stereotypes persisted through the period of Jim Crow, producing a unique set of policies and experiences of gendered racism directed toward Black women, referred to as “Jane Crow,” that ran parallel to those experienced by Black men (Essed Reference Essed1991; Murray, and Eastwood Reference Murray and Eastwood1965).

Many of these perceptions of Black women persist today, with racist and sexist stereotypes interacting to produce distinct punitive experiences for Black women in America (Morris Reference Morris2016; Ritchie Reference Ritchie2017). However, the intersectional nature of the challenges posed by the contemporary carceral state on Black women is often rendered invisible, especially in political science research. To be sure, there is a growing set of literature on the intersectional political evaluations of Black women as political candidates or voters (e.g., Gay, and Tate Reference Gay and Tate1998, Lemi, and Brown Reference Lemi and Brown2019; Philpot, and Walton Jr. Reference Philpot and Walton2007; Sigelman, and Welch Reference Sigelman and Welch1984). In describing the intersectional tensions that Black women experience as potential voters, Gay and Tate (Reference Gay and Tate1998), for example, find that Black women identify “as strongly on the basis of their gender as their race” and will even mute their support for “Black” political causes that conflict with their interests as women (169). Other works reveal the political burdens that Black women experience while operating at the intersection of multiple axes of oppression. Research finds, for instance, that stereotypes about the strength and anger of Black female political candidates make the public less willing to support them without a higher burden of proof (Philpot, and Walton Jr. Reference Philpot and Walton2007).

However, most of the research on the intersectional challenges that Black women face in American politics focuses on investigating issues of democratic representation and responsiveness reflected in the “first face of the state,” rather than on Black women’s experiences with the punitive role of the “second face” (Soss and Weaver Reference Soss and Weaver2017; see, e. g., Bonilla, and Tillery Reference Bonilla and Tillery2020; Brown Reference Brown2014). One notable exception is provided by Ange-Marie Hancock (Reference Hancock2004) whose classic work shows how stereotypical depictions of Black women as lazy, hyper-fertile, and irresponsible mothers shaped the public debate on welfare reform—so much so that Black and white legislators supported reforms that disproportionately punished Black, woman welfare recipients. Hancock’s work provides an uncommon but crucial example of how racialized and gendered public perceptions of Black women can have serious consequences for the punitive policies that affect their lives.Footnote 1 This investigation expands upon Hancock’s important intersectional work on the punitive implications of stereotypes attached to Black women, focusing instead on the perceptions and punishment of Black girls.

The punishment of Black girls

Investigations of public perceptions of Black girls, and their punitive impacts, receive even less attention in political science. This silence is particularly perplexing given evidence that suggests many of the negative public perceptions that affect the punitive experiences of Black women trickle down to Black girls (Harris-Lacewell Reference Harris-Lacewell2001).Footnote 2 Research in psychology, childhood studies, and sociology, for example, finds that Black children are often perceived as less in need of socio-emotional support compared to white students (Goff et al. Reference Goff, Jackson, Di Leone, Culotta and DiTomasso2014; Okonofua, and Eberhardt Reference Okonofua and Eberhardt2015). These perceptions, according to the literature, are a product of the same stereotypes that affect the treatment of Black women: for example, the Strong Black Woman trope that makes medical physicians less likely to take Black women’s pain seriously, or the Angry Black Woman (“Sapphire”) trope that makes police officers more likely to arraign Black women for mental breakdowns (Harris-Lacewell Reference Harris-Lacewell2001; Weisse et al. Reference Weisse, Sorum and Dominguez2003). The negative stereotypes assigned to Black women and their punitive impacts, in other words, may affect Black girls well before they become Black women.

Research on educational and criminal justice systems finds that Black girls experience disproportionate levels of punishment in these two systems. Black girls make up a disproportionate percentage of the students who are suspended and expelled from school systems, and who are arrested and detained by the criminal justice system. These disparities emerge as early as preschool. Within a school context, the disproportionate punishment of Black girls can culminate in being pushed out of school and into the criminal justice system through the now well-documented school-to-prison pipeline (Morris Reference Morris2016; Ritchie Reference Ritchie2017). Within the criminal justice system, Black girls receive harsher punishments than white girls. A study conducted by the American Bar Association and National Bar Association found that seven out of every 10 cases involving white girls were dismissed by prosecutors, compared with only three out of every 10 cases involving Black girls (American Bar Association and National Bar Association 2001). Further, Black girls often fail to receive equal opportunities for diversion—that is, discretionary prosecutorial strategies that assign disciplinary measures in lieu of formal criminal processing. This disproportionate treatment likewise extends to the foster care system where Black girls are three times more likely to be removed from their homes and placed in state custody than their white peers (Chesney-Lind, and Jones Reference Chesney-Lind and Jones2010; Roberts Reference Roberts2009).

Across multiple systems—education, criminal justice, and foster care—evidence of the disproportionality of Black girls’ punishment is clear and well-documented, but there is much that remains to be understood about the distinct punitive experiences of this group. As we outline in the following section, political science research has the potential to offer significant insights into how public perceptions of Black girls—particularly, racialized and gendered stereotypes that contribute to their “adultification”—can drive support for their punishment and punitive policy more generally. This link, though, has not yet been tested. The following section provides a brief discussion of this link before delving into this study’s specific empirical goals and contributions.

The adultification of Black girls and their punitive consequences

Black girls face race and gender-based oppression but are additionally subject to considerations of age, especially perceptions of their adult-like status. Research on race and gender has found that perceptions of the premature “adultification” of Black girls negates their status as children by the white majority (Morris Reference Morris2007; Wun Reference Wun2016a, Reference Wun2016b). As Priscilla Ocen observes, “histories of racial and gender subordination, including slavery and Jim Crow, …interacted with the category of childhood to create a liminal category of childhood that renders Black girls vulnerable to sexual exploitation and criminalization” (Ocen Reference Ocen2015, 1600). Childhood has long been a contested space of identification for Black children in America. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, Black children were often excluded from freedom laws that applied to Black adults and were required to endure indentured servitude until they were 21 or even 25 years old (Webster Reference Webster2021). At the same time, enslaved Black girls were expected to reproduce, forcing them into a liminal space between childhood and adulthood. In this liminal space, Black girls were often denied the legal privileges in the criminal justice system that childhood typically affords, like the presumption of innocence or lenience during a period of instruction. Even in the post-emancipation period, Black girls could be indentured as a form of punishment for alleged wrongdoings that ranged from owing debt to fleeing indenture (Webster Reference Webster2021).

Today, this historical notion that Black girls occupy a liminal space between childhood and adulthood persists. Adultification has both racialized and gendered components. In one of the first (and perhaps only) statistical studies published on the adultification of Black girls, scholars found that white respondents viewed Black girls as adults at 5 years old; this is 5 years earlier than Black boys and significantly earlier than every other demographic group studied (Epstein, Blake, and Gonzales Reference Epstein, Blake and González2017). Further, white respondents reported that Black girls needed less nurturing, protection, support, and comfort and were more knowledgeable about sex and adult topics than white girls.Footnote 3 Research suggests that these views likely provide fertile ground for the punishment of Black girls, especially for engaging in behavior (e.g., being too talkative, loud, knowledgeable) that is seen as inconsistent with and in defiance of traditional feminine norms (e.g., presenting as docile, meek, polite, quiet), and which must therefore be “corrected” (Crenshaw et al. Reference Crenshaw, Ocen and Nanda2014; Evans-Winters, and Esposito Reference Evans-Winters and Esposito2010; Morris Reference Morris2016; Skiba et al. Reference Skiba, Michael, Carroll Nardo and Peterson2002). But this specific relationship—between perceptions of Black girls and support for their “correction” and punishment—has not yet been empirically tested.

Correcting Black girls’ behavior through punishment, after all, often begins in the classroom (e.g., Wun Reference Wun2016b). Over the past three decades, schools across America have engaged in national disciplining projects in the form of zero-tolerance policies that have resulted in the outsourcing of disciplinary responsibilities from schools to juvenile courts and school resource officers (Blake et al. Reference Blake, Butler, Lewis and Darensbourg2011; Hines-Datiri, and Andrews Reference Hines-Datiri and Andrews2020). As research demonstrates, the students most affected by these policies are Black and Brown youth, with Black students composing nearly 30% of school arrests, despite only making up 15% of the school population (Nelson, and Lind Reference Nelson and Lind2015). This has major consequences for the punitive experiences of Black children. Cathy Cohen’s seminal text, Democracy Remixed (Reference Cohen2010), for instance, demonstrates how the stereotyping of Black youth as deviant produced a “moral panic” among the public that justifies the criminalization of Black youth and contributes to their early exclusion from American political life. Arguing that Black youth are among the most demonized and marginalized populations in American society, Cohen provides important context for how stereotypes of Black youth shape their lived realities in ways relevant to the adultification literature: by framing Black youth as deviant—as opposed to deserving of second chances and respect—Black youth are held responsible, and often harshly punished, for behaviors that white youth are not.

But the punitive experiences of Black youth can also be uniquely gendered through the rules and regulations included in school codes of conduct (Aghasaleh Reference Aghasaleh2018). Many dress code requirements, for example, only apply to girls’ attire, such as rules stipulating the minimum length and coverage of skirts, shorts, or shirt sleeves (Kosciw et al. Reference Kosciw, Greytak, Zongrone, Clark and Truong2018). These gendered regulations are often justified with the rationale that female students’ bodies can distract their male peers and that it is “unladylike” and inappropriate to dress in ways that challenge traditional gender norms of feminine morality and purity. But Black girls are doubly disadvantaged by school policies like these because of how the public views their bodies. Historically, the American public and popular media has stereotyped Black girls as sexually promiscuous or “Jezebels,” suggesting that they have heightened sexual appetites (Collins Reference Collins1990; French Reference French2013; Harris-Perry Reference Harris-Perry2011). Existing research suggests that these stereotypes continue to shape the ways that Black girls are viewed compared to white girls today, thus demonstrating “how deeply entrenched controlling narratives of Black women and girls are – no matter how young and small they are” (Ritchie Reference Ritchie2017, 74). This often results in the hyper-vigilant policing of Black girls’ bodies in schools where research has found that, even when Black girls are not actively violating a dress code, school leaders may still accuse them of intentionally doing so because of their perceived hypersexuality (French Reference French2013; Townsend et al. Reference Townsend, Neilands, Thomas and Jackson2010).

Importantly, the perception of Black girls as hypersexual undermines and negates their identity as children and has consequences for shaping opinions around the commensurability of their punishment. The adultification of Black girls contributes to societal expectations that they be held responsible for their actions—a level of responsibility that our educational and criminal justice systems do not typically assign to other children (Epstein, Blake, and Gonzales Reference Epstein, Blake and González2017; Morris Reference Morris2016). Perhaps the most notable recent example is that of a 9-year-old Black girl who was arrested and pepper-sprayed by police officers after throwing a tantrum in Rochester, New York, in January 2021. Following the incident, a journalist reported that “at one point, one officer says, ‘You’re acting like a child,’ to which the girl can be heard responding, ‘I am a child!’” (Ly, and Levenson Reference Ly and Levenson2021). The exchange between the officer and the 9-year-old girl illustrates how Black girls are explicitly “aged up” and thus held responsible for “disruptions” that would be considered age-appropriate behavior for most children.

Given existing theory and research, therefore, we expect that public perception of Black girls as un-childlike—as individuals who should be treated like adults—likely plays an important role in shaping support for the punishment of Black girls at the hands of state institutions like schools and the criminal justice system. We know from research on gender and race in the field of education that gendered, racialized, and age-based stereotypes about Black girls result in public perceptions of their hypersexuality and adult-like status. We also know that Black girls are disproportionately punished in school and criminal justice systems. What we do not yet know is how and whether “adult-like” perceptions of Black girls are associated with support for their punishment or for punitive policy, more generally, because the link between public attitudes on adultification and punishment has not been explicitly tested.

Strategy for analysis

Based on the theories presented in the research above, we hypothesize that Black girls will be seen as more adult-like than otherwise comparable peers and that this adultification will drive support for harsher punishment of Black girls for equivalent transgressions. To test these expectations, we conducted two rounds of surveys designed to measure public perceptions of Black girls and attitudes toward their punishment. First, we fielded an exploratory set of survey experiments via MTurk with a representative sample of 1,466 adults between March 8 and March 15, 2020. We then followed up with a replication of this study in October 2020 on a representative sample of 2,266 adults via Prime Panels. In the replication, we included an extra battery of questions on support for additional types of punishment and punitive policies. The samples are primarily white and relatively highly educated, democratic, and liberal compared to the general population.Footnote 4 Nevertheless, the samples are more diverse than many samples commonly used in experimental survey research (see, e.g., Berinsky, Huber, and Lenz, Reference Berinsky, Huber and Lenz2012; Collins Reference Collins2021; Guess, and Coppock Reference Guess and Coppock2020; Huff, and Tingley Reference Huff and Tingley2015).Footnote 5

For the survey experiment, respondents were given a scenario about a dress code violation in which the perceived race and gender of the student were randomly assigned. Following previous research, the scenario manipulated the perceived race and gender of the students through names only, randomly assigning each respondent one of four names: Keisha (Black girl), Emily (white girl), Jamal (Black boy), and Jake (white boy). The selected names were derived from previous work that found them to be disproportionately common among particular racial-gender subgroups (Bertrand, and Mullainathan Reference Bertrand and Mullainathan2003; Gilliam et al. Reference Gilliam, Maupin, Reyes, Accavitti and Shic2016 Okonofua, and Eberhardt Reference Okonofua and Eberhardt2015).Footnote 6 The dress code scenario presented to the respondents was the following:

Consider an instance where a student named [name] is wearing shorts to school. When [name] arrives to class, the teacher tells [her/him] that [his/her] shorts violate the school’s dress code policy. The teacher tells [her/him] to leave class and go to the office. This also isn’t the first time that [name] has worn clothes that violate the school’s dress code policy. For example, [he/she] has previously worn tank tops that are against school rules.

The content of the dress code scenario was developed based on qualitative research of the distinctly racialized and gendered punishment that Black girls experience in school settings (Morris Reference Morris2016). The intersectional nature of these experiences is commonly overlooked in studies that focus on just issues of race or gender. Thus, the vignette is meant to capture a scenario that could feasibly happen to both boys and girls but could still be perceived differently if viewed through a racialized and gendered lens (e.g., how clothing may be viewed on Black girls vs. white girls).Footnote 7 Dress code violations, specifically, are commonly referenced as an example of this type of scenario in the relevant literature (Morris Reference Morris2016; Evans-Winters, and Esposito Reference Evans-Winters and Esposito2010). Footnote 8 Since all other properties of the scenarios and questionnaire were identical, any observed differences between conditions in responses to the scenario’s questions can be attributed to race and gender.Footnote 9

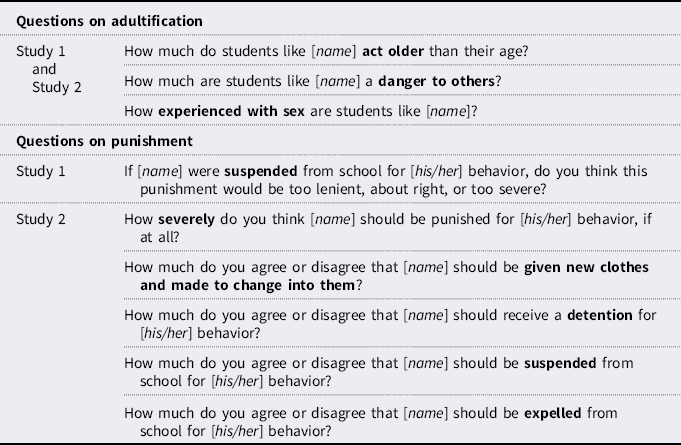

Following the presentation of the dress code scenario, respondents were asked about their perceptions of the student randomly assigned to them. In particular, we are interested in capturing how adult-like the student appeared to be to respondents. To develop our measures of adultification, we replicated items used by Goff et al. (Reference Goff, Jackson, Di Leone, Culotta and DiTomasso2014) and Epstein, Blake, and Gonzales (Reference Epstein, Blake and González2017) that measure how racial and gender stereotypes can contribute to evaluations of Black children as more adult-like. Table 1 includes the question wording used in our adultification measures, in which survey respondents were asked whether they felt that students like the one named in the dress-code scenario 1) act older than their age, 2) are a danger to others, and 3) are experienced with sex, using a 4-point scale ranging from not at all to a great deal.

Table 1. Question wording for adultification and punishment variables in survey experiment

We then asked respondents whether they felt different punishment(s) were appropriate for the student in the vignette. In Study 1, we asked respondents whether a punishment of suspension was too lenient, about right, or too severe. In our follow-up study (Study 2), we asked four questions about whether the respondent supported (using a 7-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree) a series of punishment scenarios: the student should be made to change his/her clothes, should be given detention, should be suspended, or should be expelled. Respondents were also asked a question about “how severely [the student] should be punished for [his/her] behavior, if at all?” and were given a 5-point scale ranging from not at all to extremely.

Findings on public perceptions of the adultification of Black girls

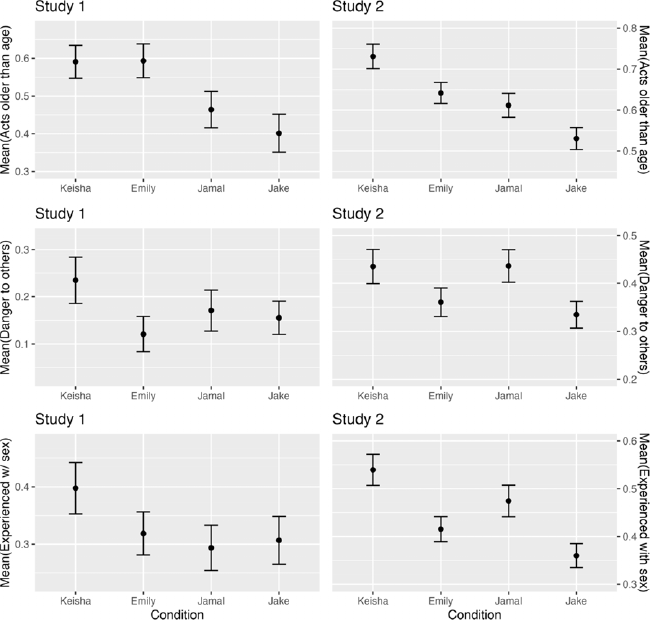

The following section reports our experimental results on the three adultification questions posed in Study 1 and Study 2. Each subfigure in Figure 1 illustrates the treatment group means on the survey question given at the left.Footnote 10 Following Graham (Reference Graham2023) and Julious (Reference Julious2004), point estimates for the mean are drawn with 84% confidence intervals to aid with interpretation; statistical significance can be discerned from a visual comparison of the estimates.Footnote 11 The results for Study 1 and Study 2 are presented side-by-side for ease of comparison.

Figure 1. Respondents’ perceptions of student’s age-appropriateness, danger to others, and experience with sex, by experimental condition

The left-hand column of the first row of Figure 1 displays the means of participant responses in Study 1 to the question of how much students like [assigned name] in the dress code scenario act older than their age. The results reveal that respondents viewed students like Keisha and Emily (M = .59, se = .03 for both Keisha and Emily) as both acting older than their age compared to students like Jake (M = .40, se = .04) or Jamal (M = .46, se = .03). These differences between Keisha or Emily and Jake or Jamal are significant at the p < .01 level.

The second row of Figure 1 displays the means of participant responses to the question of how much students like [assigned name] in the dress code scenario are a danger to others. This analysis reveals respondents viewed Keisha (M = .24, se = .03) as more of a danger to others as compared to Emily (M = .12, se = .02, different from Keisha at p < .05). Respondents also viewed Keisha as more of a danger to others compared to Jamal (M = .17, se = .03) or Jake (M = .16, se = .02), but neither of these differences were statistically significant. There were no statistically significant differences between how respondents viewed Emily, Jamal, and Jake.

The third row of Figure 1 displays participant responses to the question of how much students like the one in the dress code scenario are experienced with sex. Respondents viewed Keisha (M = .40, se = .03) as more experienced with sex than Jamal (M = .29, se = .03) and Jake (M = .31, se = .03) with differences that are significant at the p < .10 level. The difference between how respondents evaluated Keisha and Emily (M = .32, se = .03) is not significant.

The results from Study 2 are displayed in the right-hand column of Figure 1. Study 2 was fielded in October 2020 immediately following the summer of mass protests held in response to the murder of George Floyd. This was a period of heightened national awareness and exposure to stories about the punishment of Black men at the hands of authority and thus may have made race more salient to respondents. Like in Study 1, participants responding to the older-than-age question largely viewed Keisha as acting older than her age (M = .73, se = .03). But unlike in Study 1, the mean for Keisha was significantly higher than that for any of the other treatment groups, including Emily (M = .64, se = .03), Jamal (M = .61, se = .03), and Jake (M = .53, se = .03), with all differences significant at p < .01. Still, the mean for each girl (Keisha and Emily) was significantly higher than the mean for the boy in their racial group (Jamal and Jake, respectively). Study 2, in other words, provides evidence that responses to the older-than-age measure of adultification were not only gendered (as was found in Study 1) but also racialized.

Participant responses to the danger-to-others question in Study 2 also reveal more significant racialized effects than are present for the same question in Study 1. In particular, respondents viewed Keisha (M = .43, se = .04) and Jamal (M = .44, se = .03) as more of a danger to others as compared to Emily (M = .36, se = .04) and Jake (M = .33, se = .03), with differences significant at the p < .05 level.

Participant responses to the experienced-with-sex question viewed Keisha (M = .54, se = .03) as more experienced with sex than Jamal (M = .47, se = .04), Emily (M = .42 se = .03), and Jake (M = .36, se = .03), with differences significant at the p < .05 level. It is notable that in Study 2 the Black students had the highest means, suggesting a racialized effect in the responses to this question. But Keisha was still seen as significantly more experienced with sex than Jamal.

Overall, the results in Figure 1 reveal that Black girl students are likely to be perceived as more “adult-like” in the context of infractions like dress code violations. While Jamal plays a more prominent role in Study 2 than in Study 1 on the adultification questions pertaining to being a danger to others and more experienced with sex, overall Keisha was still perceived as acting relatively older than her age, dangerous to others, and more experienced with sex than most other students across the questions in Study 2. These findings are consistent with research on the intersectional nature of racist and sexist stereotypes of Black girls in schools (Morris Reference Morris2016; Epstein, Blake, and Gonzales Reference Epstein, Blake and González2017). In particular, both Studies 1 and 2 provide evidence that Black girl students are viewed as acting older than their age compared to white boys, white girls (in Study 2),Footnote 12 and Black boys. Further, they reveal that Black girls are viewed as more of a danger to others than white boys and girls, as well as more experienced with sex than all other students examined (in Study 2). To be sure, Study 2 also demonstrates that Black boys are similarly viewed as more threatening and experienced with sex than white boys and girls. Yet, given the racialized political climate of the time when the survey was fielded, one might expect respondents to be more attuned to issues facing Black boys than in Study 1. In this way, Study 2 acts as a more conservative test of our adultification questions. Still, despite this racialized context, the results of Study 2 largely support our original hypotheses as stereotypical adult-like perceptions of Black girls remain strong across conditions.Footnote 13 Altogether, the studies suggest that Keisha tends to be viewed as relatively older-acting, more dangerous, and experienced with sex in the context of violating the dress code.

Connecting adultification to support for punishment and punitive policy

To examine the hypothesized link (“adultification”) between stereotypes and punitive attitudes, we perform a mediation analysis using the data from Study 2. To create a measure of punitive attitudes, we included results from our five questions on punishment from Study 2 (see Table 1) in a principal components analysis. A single factor emerged, suggesting the questions combine to predict the underlying construct of punishment in an index variable (see details in the Appendix). We then estimated two Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression models with this factor-based punishment index as the dependent variable. In the first model (“Treatment Only”), we included only the set of treatment indicators. In the second model (“Mediation”), we added the measures of stereotypes discussed in the previous section: acting older than one’s age, being a danger to others, and being experienced with sex.

The coefficient estimates of these regression models are presented in Figure 2.Footnote 14 In the Treatments-Only model, receiving the Keisha treatment was associated with increased punitive attitudes (per the index) relative to the base category (the “Jake” treatment); no other treatments were significantly different from the base category. In the Mediation model, the coefficients of all treatment indicators are reduced in magnitude and none are significant at p < .05. The measures of adultification—acting older than one’s age, knowledge of sex, and especially being a danger to others—are significant and positively associated with punitive attitudes toward the student in the vignette. This analysis provides evidence that the heightened punitive attitudes elicited by the Keisha treatment run through the adultification stereotype pathways.

Figure 2. Mediation analysis: predictors of support for harsher punishments

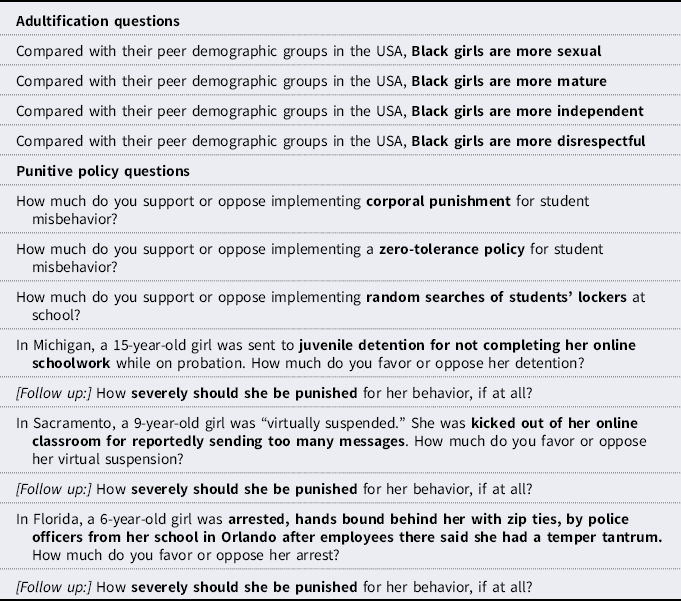

Finally, we present observational evidence that a similar pattern between stereotypical adult-like perceptions of Black girls and attitudes on punishment exists in “real-world” school settings. In Study 2, we asked respondents a series of questions about adultification stereotypes and a second battery of questions about how they viewed student punishment. In this battery, we asked about respondents’ support for or opposition to a series of punishment policies (e.g., corporal punishment, zero-tolerance policies, random searches of students’ lockers) and about real-world scenarios that had been reported in the news in which students had been punished or arrested for school infractions. For the real-life scenarios, we asked whether respondents supported or opposed the punishment or arrest of the student in question and follow-up questions on how severely the student should be punished. The wording of the adultification questions and punishment questions is presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Question wording for observational measures on adultification and punishment

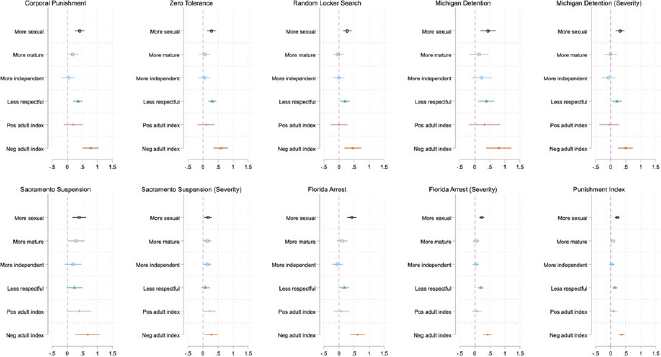

We also used principal components analysis to build more robust measures of stereotypical adultification attitudes and punitive attitudes using each of the blocs of questions in Table 2. For the adultification stereotypes questions, two factors emerged from the data and we created a variable based on each. The first is associated with being more sexual and disrespectful; we label this the “negative adultification index.” The second is associated with maturity and independence; we label this the “positive adultification index.” Two factors emerged for the punishment questions and we use scores based on the first factor in our analyses.Footnote 15 Full diagnostics of the factor analyses are provided in the Appendix. We use OLS regression to examine the relationships between perceptions of adultification and support for punitive policies and punishment in the real-life scenarios. Each subfigure in Figure 3 presents the results of bivariate regressions of support for a particular punitive policy or punishment (at top) on each stereotypical perception (listed at left).

Figure 3. Association between adultification stereotypes about Black girls and support for harsh punitive policy

In nearly every case, negative adultification-stereotype perceptions of Black girls being more sexual and less respectful (and the factor-based index of negative adultification views) are positively associated with support for punitive policy and statistically significant. In most cases, the more positive stereotypes of maturity and independence are not significantly associated with support for punishment. In the highest-level relationship, we find that a one standard-deviation increase in negative adultification-stereotype perceptions is associated with a .36 standard deviation increase in support for punitive policies. This pattern of findings provides more evidence for the link between adultification and punishment.

These relationships hold up in nearly every case when we add additional demographic and ideological covariates to the model; for the most part, those other covariates are not significantly related to attitudes toward punishment (with the exception of women, who are less supportive of harsh punishments across the board). These findings indicate that there is a robust association between negative stereotypical perceptions of the adultification of Black girls and support for harsher punishment in school settings.

Conclusion

Over 15 years ago, Evelyn Simien wrote, “empirical assessments of the simultaneous effects of race and gender are indeed rare” in political science (Reference Simien2005, 531). A growing number of political scientists have employed the theoretical and empirical tools of intersectionality to examine how categories of marginalization intersect with each other to shape Black women’s political lives (e.g., Bonilla, and Tillery Reference Bonilla and Tillery2020; Farris, and Holman Reference Farris and Holman2014; Smooth Reference Smooth2006). As in other areas of study, however, most of the extant research on public perceptions of Black women focuses on how race and gender stereotypes might affect their support as political candidates or their voting behavior as evaluators of politics (e.g., Brown Reference Brown2014; Simien Reference Simien2007). Far less scholarly attention has been paid to how intersectional stereotypes shape formative interactions with authority for young Black women or girls.Footnote 16

Accordingly, this investigation places the punitive experiences of Black girls at the center of research on race, gender, and American public opinion. In so doing, it provides substantial empirical support for a literature on race-gender stereotypes that has up to now been largely theoretical, particularly as it relates to Black girls (Collins Reference Collins1990, Reference Collins1993; Crenshaw Reference Crenshaw1989; Harris-Perry Reference Harris-Perry2011; Nuamah Reference Nuamah2019). Further, it helps to illuminate the mechanisms by which these attitudes operate, particularly for an existing set of research that reports on Black girls’ disproportionate punishment.

As Ange-Marie Hancock explains in her classic work on intersectionality, research that conflates “group unity” with “group uniformity”—or, assumes that individuals who share one marginalized identity [Black or female] have uniform experiences of discrimination—is incomplete (Hancock Reference Hancock2007a, 65). Hancock explains that the policy solutions that emanate from this research often benefit white women at the cost of women of color and exacerbate existing inequities (Hancock Reference Hancock2007a, Reference Hancock2007b). The inequities produced by these policies exist for Black girls as well, making them disproportionate recipients of punishment. This investigation specifies the potential role of the general American public—not just political elites or school leaders—in contributing to the uneven punitive experiences these policies produce for Black girls.Footnote 17

Beyond public opinion, this work raises serious questions about the consequences of Black girls’ punishment for democracy in America. What does a lifetime of punishment—starting in our most formative institutions, like schools—mean for this population’s political behavior (see Bruch, and Soss Reference Bruch and Soss2018; Nuamah Reference Nuamah2022)? What lessons might Kaia Rolle draw from her recent experiences with the justice system, and how might they impact her relationship with the government as an adult? Research on the punishment of Black men and Black communities has found that incarceration lowers the political participation of not only those who have felony convictions but their families and neighbors as well (Burch Reference Burch2013). Studies on the political effects of punishment for Black women are less common, but there may be similar negative consequences of high incarceration rates and detention on what have otherwise been record levels of political participation for Black women (Brown Reference Brown2014; Farris, and Holman Reference Farris and Holman2014).

Ultimately, given the superlative participation of Black women in American electoral politics, one would expect the punitive experiences of Black girls to have lasting impacts on the future strength of American democracy, especially as they become voting-age adults. Still, before Black women become adult voters or political candidates, they are Black girls. And as this investigation reveals, Black girls are disproportionately punished with the majority-white American public’s robust support. If American democracy is only as strong as its participants, then the punishment of Black girls, and the perceptions shaping them, must not only be understood but also dismantled. In short, public support for the punishment of Black girls can no longer be ignored.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2023.13

Acknowledgements

This paper benefited from valuable feedback provided by academic colleagues at the Institute for Policy Research at Northwestern University, the University of Pennsylvania’s Graduate School of Education, Ashoka University’s “Politics and Thought” Series, and Oxford University’s Politics Colloquium, where earlier versions of this work were presented. The authors would also like to thank Tabitha Bonilla, Kevin Levay, Thomas Ogorzalek, and the anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful comments and suggestions, and for research support from students Irene Kwon, Vivica Lewis, and Carol Silber. The authors would like to thank Carnegie Corporation for providing funding for this project. There are no competing intetests.

Competing interests

There are no competing interests.