INTRODUCTION

The past decade has seen academia become an increasingly common political target. For example, former presidential candidate Rick Santorum accused professors of “trying to indoctrinate students,” and called colleges and universities “indoctrination mills” (Gross Reference Gross2012). Given the propensity of college professors to be politically liberal (Rothman, Lichter, and Nevitte Reference Rothman, Robert Lichter and Nevitte2005), perhaps it should come as no surprise that conservative politicians would periodically fixate on the professoriate and accuse the institution of academic tenure of helping to perpetuate the indoctrination of college students and prohibiting a truly diverse intellectual environment, despite recent literature showing such concerns to be unfounded (Mariani and Hewitt Reference Mariani and Hewitt2008; Woessner and Kelly-Woessner Reference Woessner and Kelly-Woessner2009).

This study explores the student–teacher relationship by focusing on students’ perceptions of professors’ ideology. More specifically, we examine the link between student ideology, professor favorability, and perceptions of professors’ ideology. Recent research in this area has shown that students tend to project their own ideology onto their professors (Kelly-Woessner and Woessner Reference Kelly-Woessner and Woessner2006), that students who perceive a greater difference between their own ideology and their professors’ ideology are more likely to show interest in the subject (Kelly-Woessner and Woessner Reference Kelly-Woessner and Woessner2008), and that students with a stronger sense of identity are more likely to perceive their professors as having a political bias (Linvill Reference Linvill2011). We suspect that the literature has missed an important potential interaction between student ideology and professor favorability, and that students—like most individuals—will process incoming information in a way that is consistent with their pre-existing beliefs (Lewandowsky et al. 2012). Consequently, we predict that students will be more likely to project their ideology onto their professors, conditional on whether they like those professors; conversely, students will be more likely to project the opposite ideology onto their professors if they dislike those professors. This is similar to behavior consistent with social identity theory (see Devine Reference Devine2015; Tajfel et al. Reference Tajfel, Billig, Bundy and Flament1971; Billig and Tajfel Reference Billig and Tajfel1973), in that ideological projection onto a well-liked professor reinforces positive self-evaluations and helps establish a sense of belonging.

In order to gauge the aforementioned relationship, we design a survey instrument, employed at two different universities, that measures students’ political ideology, political knowledge, favorable views regarding their professors, and perceptions of professors’ ideology, inter alia.

This article will proceed by first reviewing the relevant literature on political ideology and the classroom experience. We then discuss our extension of the literature, in particular, the interaction between student ideology and professor favorability. Next, we describe the survey in more detail, including the variables that were created using the survey responses. Finally, we discuss the findings and their implications for instructors and future research.

In order to gauge the aforementioned relationship, we design a survey instrument, employed at two different universities, that measures students’ political ideology, political knowledge, favorable views regarding their professors, and perceptions of professors’ ideology, inter alia.

STUDENT AND PROFESSOR IDEOLOGY

Consistent with the popular stereotype of a liberal professoriate, recent research has shown that college professors in general (Gross and Fosse Reference Gross and Fosse2012), and political science professors in particular (Rothman, Lichter, and Nevitte. Reference Rothman, Robert Lichter and Nevitte2005), are predominantly liberal.

Other studies have qualified the liberal bias of college professors. For example, Nakhaie and Brym (Reference Nakhaie and Brym1999) find significant variation among college professors according to their field of study. Their results show that political science professors tend to be more liberal than those in business, engineering, and the natural sciences (Nakhaie and Brym Reference Nakhaie and Brym1999). In a similar result, Zipp and Fenwick (Reference Zipp and Fenwick2006) find considerable variation across fields of study. Conservatives are even the plurality in some fields and institutional types. Footnote 1 Most interestingly, the authors find that the overall trend between 1989 and 1997 was for college professors to move towards the center and become more moderate, contrary to the stereotype that the professoriate is only becoming more liberal (Zipp and Fenwick Reference Zipp and Fenwick2006).

Does a professor’s ideology really matter? There is a long-held assumption that college professors are not only liberal, but that their influence tends to make students more liberal. However, contrary to the fears of some conservative politicians, recent research has shown that a professor’s ideology has little impact upon the ideology of their students (Mariani and Hewitt Reference Mariani and Hewitt2008), and that students do tend to become more liberal over the course of a semester, but the change is the same regardless of a professor’s ideology (Woessner and Kelly-Woessner Reference Woessner and Kelly-Woessner2009).

Earlier research on the classroom experience focused more on professor favorability than ideology. For example, Feldman (Reference Feldman1986, 301) found that students and teachers tend to rate the characteristics of a good teacher similarly, with three notable exceptions: stimulating students’ interest, encouraging self-initiated learning on the part of students, and the extent to which teachers challenge students intellectually.

More recent research has linked favorability with ideology. For example, Kelly-Woessner and Woessner (Reference Kelly-Woessner and Woessner2006) found that students are more likely to be liberal than conservative, but that students are still more ideologically diverse than their professors. Moreover, “greater ideological/partisan difference results in more negative course evaluations” (Kelly-Woessner and Woessner Reference Kelly-Woessner and Woessner2006, 499). Footnote 2 Although the aforementioned work by Kelly-Woessner and Woessner (Reference Kelly-Woessner and Woessner2006) looked at correlations between student–professor ideological congruence and professor evaluations, it left the question of whether perceived ideological congruence might be conditional on professor favorability open for future research.

Although some studies have shown that presenting subjects with factual information can cause them to change their positions on issues (Kuklinski et al. Reference Kuklinski, Quirk, Jerit, Schwieder and Rich2000), other studies have shown that people often reject information that does not conform to their pre-existing beliefs (Lewandowsky et al. 2012; Lord et al. Reference Lord, Ross and Lepper1979; Taber and Lodge Reference Taber and Lodge2006). Moreover, attempts to correct factual information pertaining to previously held beliefs may “actually strengthen misperceptions” among those with fervent ideological inclinations (Nyhan and Reifler Reference Nyhan and Reifler2010, 323). Given these relationships, students may be loathe to believe that a professor whom the student likes does not share their political views. We suspect that students will tend to project their own ideology onto professors they view with favor, absent accurate information about their professors’ true political orientation. Since many professors, including the authors of this paper, take pains to avoid directly stating their party affiliation or ideological orientation, it seems less likely that the causal direction could be reversed; namely, that professor favorability could be the result of student ideology, conditional on professor ideology. Footnote 3 Regardless, we test for this endogenous relationship and discuss the findings in both the results section and the appendix.

To state our predictions empirically, (H 1 ) when liberal/conservative students view a professor favorably, they will perceive their professor as also being liberal/conservative, ceteris paribus. However, (H 2 ) when liberal/conservative students view their professor unfavorably, they will perceive that professor as being aligned with the opposite ideology (conservative/liberal), ceteris paribus. In the next section, we propose an original survey that allows us to examine the relationship between student ideology, professor favorability, and perceptions of professor ideology.

To state our predictions empirically, (H 1 ) when liberal/conservative students view a professor favorably, they will perceive their professor as also being liberal/conservative, ceteris paribus.

RESEARCH DESIGN

In order to test our hypotheses, we designed a survey questionnaire to be completed by current students and administered towards the end of each semester. Students were awarded a small amount of extra credit in exchange for their participation. Footnote 4

The surveys were conducted during the spring 2014, fall 2014, spring 2015, fall 2015, and spring 2016 semesters, using students from multiple classes at Texas A&M University—Kingsville and Arkansas State University. Classes included freshman-level introductory classes and upper-level electives in both public law and international relations. Footnote 5 The sample included 81 freshmen, 112 sophomores, 71 juniors, 42 seniors, and 28 students that listed themselves as “something else” or “unsure.” A total of 334 students were recruited, 62 of which were political science majors.

The Student Ideology and Professor Ideology variables were created using subjects’ answers to placement questions measured on a five-point scale, where 1 was “very conservative” and 5 was “very liberal” (this, and all question wordings can be found in the online appendix). The average student reported an ideology that was moderate (

![]() $\overline x = 2.95$

). Students tended to rate their professors as slightly more liberal than themselves (

$\overline x = 2.95$

). Students tended to rate their professors as slightly more liberal than themselves (

![]() $\overline x = 3.18$

); this difference was statistically significant (t(333) = -3.6, p < 0.001). Similar results were found for variables indicating students’ political party affiliation.

$\overline x = 3.18$

); this difference was statistically significant (t(333) = -3.6, p < 0.001). Similar results were found for variables indicating students’ political party affiliation.

Given the preceding theoretical discussion, we expect that students’ ideology will interact with professor favorability to determine perceptions of professors’ ideology. We use three different variables to capture professor favorability. First, the variable Recommend indicates students’ likelihood of recommending the course measured on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 was “strongly disagree” and 5 was “strongly agree.” Second, the variable Quality of Instruction captured assessments of instruction quality using a 1-7 scale, where 1 was “extremely poor” and 7 was “extremely good.” Finally, a third variable was added in the last two semesters of testing (fall 2015 and spring 2016). The more direct Like Professor variable asked students about their personal feelings towards their professor, where 1 was “I very much dislike him” and 5 was “I very much like him.” Ancillary analysis revealed these three variables are all closely related concepts (α = .74); moreover, factor analysis suggests these three variables are measuring the same unidimensional construct. Footnote 6 Descriptive statistics for the ideology and favorability variables are provided in table 1.

Table 1 Summary Statistics

We interacted all three professor favorability variables with the student ideology variable. If our first hypothesis is correct, we expect the interactions to be positively related to perceptions of professor ideology, since students who like the professor should be more likely to project their own ideology, so as to remain consistent with their favorable views. Similarly, commensurate with our second hypothesis, students should perceive ideological incongruence for a professor that is viewed unfavorably.

FINDINGS

We use perceived Professor Ideology as the dependent variable. Self-reported Student Ideology, the three professor favorability variables, and interactions between Student Ideology and the professor favorability variables are the primary independent variables.

Given the ordinal nature of the dependent variable, an ordered logit or probit model would be most appropriate. However, for simplicity of interpretation, results are estimated using OLS regression. Footnote 7 Because estimated standard errors may vary systematically by classroom (i.e., the variance of the error terms are not random), we cluster the standard errors by classroom. Finally, since we are pooling across two different professors, we include a dummy variable (Professor A Dummy indicated subjects from Ausderan’s classes) to capture any variance explained by this difference.

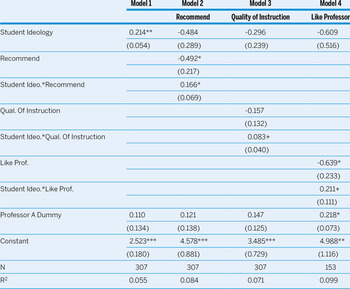

We begin by replicating models previously explored in the literature (Kelly-Woessner and Woessner Reference Kelly-Woessner and Woessner2006). Namely, we regress student ideology on professor ideology. The results are shown in table 2, model 1.

Table 2 The Effect of Student Ideology and Professor Favorability on Student Assessment of Professor Ideology

Note: OLS regression estimates. Dependent variable is student assessment of professor ideology (1=very conservative, 5=very liberal). Robust standard errors clustered by class in parenthesis. ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, + p < 0.10 (two-tailed).

As expected, the regression coefficient for the Student Ideology variable is positively signed and statistically significant at the p < .01 level. This indicates that more liberal students tend to perceive their professors as more liberal (and conversely, that more conservative students tend to perceive their professors as more conservative). Considering that our survey was not only conducted using an entirely different population, but several years after Kelly-Woessner and Woessner’s (Reference Kelly-Woessner and Woessner2006) study, our results contribute significantly to the robustness of the relationship between students’ ideology and perceptions of professors’ ideology. Footnote 8

Models 2, 3, and 4 test the first and second hypotheses by adding the three measures of professor favorability discussed above and their interactions with student ideology. In all three model specifications, the interaction between the professor favorability measures (Recommend, Quality of Instruction, and Like Professor) and Student Ideology are all positive and statistically significant (table 2).

As expected, the regression coefficient for the Student Ideology variable is positively signed and statistically significant at the p < .01 level. This indicates that more liberal students tend to perceive their professors as more liberal (and conversely, that more conservative students tend to perceive their professors as more conservative).

The interpretation of interactive relationships can be somewhat precarious, so to aid in this effort, figures 1-3 show the predicted values of the dependent variable (perceived Professor Ideology) as Student Ideology changes from very liberal to very conservative. The dashed lines show this change for students who reported the maximum value for the professor favorability variables, hence the upward slopes (i.e., for students who like the professor, students at the lower, conservative end of the ideology scale perceived the professor as also being at the lower end). The solid lines show this change for students who reported the minimum value for the professor favorability variables, hence the downward slopes (i.e., for students who dislike the professor, students at the lower, conservative end of the ideology scale perceived the professor as being at the higher, liberal end of the ideology scale. Footnote 9

Figure 1 Predicted Values of Professor Ideology as Student Ideology Changes from Very Liberal to Very Conservative, Conditional on Recommend

Figure 2 Predicted Values of Professor Ideology as Student Ideology Changes from Very Liberal to Very Conservative, Conditional on Quality of Instruction

Figure 3 Predicted Values of Professor Ideology as Student Ideology Changes from Very Liberal to Very Conservative, Conditional on Like Professor

Beginning with figure 1, we see the relationship between Student Ideology (x-axis) and perceived Professor Ideology (y-axis) for two different scenarios, where the level of Recommend is held at the minimum value (solid line), and where the level of Recommend is held at the maximum value (dashed line), all else is held constant. Just as hypothesis one predicted, for students who would recommend the course (dashed line), conservative students perceive their professor as being conservative (Professor Ideology = 2.49), while liberal students perceive their professor as being liberal (Professor Ideology = 3.88). Conversely, for students who would not recommend the course (solid line), conservative students perceive their professor as being liberal (Professor Ideology = 3.79), while liberal students perceive their professor as being conservative (Professor Ideology = 2.53).

Figures 2 and 3 tell a similar story. In figure 2, we show the same changes but use the Quality of Instruction variable to measure favorability (table 2, model 3). While the differences are slightly less pronounced for conservative students, again, we see students projecting their own ideology onto their professor when they enjoyed the quality of instruction (3.83 for liberals, versus 2.70 for conservatives), and students projecting the opposite ideology onto their professor when they were displeased with the quality of instruction (3.14 for conservatives, and 2.30 for liberals).

Finally, in figure 3 we show the same changes, but use the Like Professor variable to measure favorability (table 2, model 4). Consistent with hypothesis 1, when the professor is liked (dashed line), conservative students believe that they have a conservative professor (2.26), and liberal students a liberal professor (4.04); however, when the professor is disliked (solid line), the opposite is true (3.97 for conservatives, 2.39 for liberals).

Cautious readers may have a few questions about the robustness of the findings; we conducted a number of ancillary tests to preempt such concerns. Namely, we used an instrumental variables approach to check for endogeneity (none was found) and checked to ensure the results were not conditional on students’ level of political knowledge (they were not). Footnote 10 These results can be found in the online appendix.

CONCLUSION

The statistical results in this article suggest that, rather than forming perceptions of their professors’ political views based on their professors’ actual policy positions (which the authors of this article were careful not to reveal), students tend to project their own ideology (or the opposite) onto their professor based on the extent to which they like their professor. This should bring a degree of solace to those concerned that the university setting is an enclave of like-mindedness. On the contrary, it appears professors are first subjected to evaluations from students, which then condition attitude formation about professors’ ideology.

Future research could build upon this study in a number of ways. First, the authors of this article are both male, which may have affected the survey results. Although the authors have no explicit expectations regarding sex-based differences in the hypothesized relationships between student ideology, professor likability, and perceptions of professor ideology, extant research has suggested that students evaluate male and female professors differently. For example, Centra and Gaubatz (Reference Centra and Gaubatz2000) found that female instructors received higher evaluations from female students, while male instructors showed no difference in evaluations contingent on the student’s sex. This study could be improved upon by evaluating the robustness of the results using female professors.

Second, it would be useful to collect survey data multiple times throughout a single semester (naturally, using the same sample of students), so that changes in perceptions of professor ideology could be tracked over the course of a semester as students get to know their professor better. In every course, there will be some students who drop out before the semester is over (and before survey data is collected). It is possible that there are observable differences between students who leave and students who remain in the course through the end of the semester. The student population at the beginning of the semester would therefore be systematically different from the student population at the end of the semester, in ways that could affect the results of the survey. Tracking the exact rates of change in perceptions of professor ideology and whether students like their professors, especially as grades come in over the course of the semester, has the potential to further illuminate the process by which students form those perceptions.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096516003206