“The refugee problem in Dade has set white against Cuban, black against Cuban, black against white, and in a sense, all of the above against Carter.”

—The Washington Post, September 29, 1980Footnote 11. Introduction

Does exposure to a mass migration event cause citizens to vote against incumbents? In this paper, I investigate one of the most acute mass migration events in US history: the 1980 Mariel Boatlift during which more than 125,000 Cubans fled to South Florida in seven months at the height of President Jimmy Carter's reelection campaign. I study this case in two steps. First, I use a difference-in-differences design and synthetic control approach to estimate how much smaller Carter's vote share was in 1980 when compared to counties not affected by the Boatlift. I then use archival precinct-level data from Miami and Hudson County, New Jersey, the county with the second largest Cuban population in the US, to evaluate which neighborhoods voted more against Carter and whether this was a consequence of local immigration.

I find that Miami voted less for Carter in 1980 than expected based on previous elections and similar counties but that this was not a local consequence of the refugee crisis in their community. Instead, Cubans dramatically shifted to support Carter's opponent, Ronald Reagan, even in counties that were not exposed to the crisis. The most likely explanation for this pattern is Reagan's aggressive anti-Castro stance rather than a shift toward Republicans in general or a general distaste for incumbents. While I do not have direct evidence for this, I find that Republican challengers in US House races in Miami did not fair better in Cuban neighborhoods in 1980 than in 1976, suggesting that Cuban neighborhoods were favoring Reagan in particular rather than increasingly supporting Republicans or challengers in general.

In other cases, citizens may punish incumbents for refugee crises in their communities. The Mariel Boatlift is unusual when compared to hypothesized immigration where immigrants move in as a very small minority—Miami had a large Cuban population before the crisis, and that may have made the crisis less disruptive. Yet, it is often the case that immigrants settle in communities where immigrants from their country have settled in the past, making this aspect of the case more similar to typical immigration than it may at first appear. The Mariel Boatlift also stands apart from some recent migration events. While refugees in some more recent crises have either only briefly interacted with natives or have participated in facilitated interactions with natives (e.g., Steinmayr, Reference Steinmayr2021), the Cuban refugees fell somewhere inbetween with many moving to Miami but only beginning to adjust to life in the US after the 1980 presidential election I study. Finally, the Mariel Boatlift also occurred at a time when immigration policy was less partisan. Perhaps, if a similar event happened today, voters would be more likely to change their vote.

Despite these caveats, this study still suggests that even a historically large, acute refugee crisis may not lead citizens to noticeably punish incumbent politicians.

2. Studying the effect of immigration on voter behavior

2.1 Should we expect citizens to punish incumbents for immigration?

The expectation many have that citizens in receiving communities will punish incumbents for immigration has two components: first immigration makes citizens worse off in some way, whether economically, socially, or psychically, then those citizens vote against the politicians in office because they were made worse off.Footnote 2 This first step is subject to considerable debate in the economics literature, including multiple papers studying the case of the Mariel Boatlift. While some scholars find that the increased labor supply from the Boatlift caused a drop in wages for specific subgroups (Borjas, Reference Borjas2017), the bulk of the evidence suggests that the Boatlift did not meaningfully reduce wages, even for the Miami residents most likely to compete with the refugees for work (Card, Reference Card1990; Peri and Yasenov, Reference Peri and Yasenov2019). Still, citizens may have other concerns about local immigration unrelated to the labor market. For example, citizens may see increased demand for government services like schools or health and human services agencies and worry that they may not have access in the future or that they will have to pay higher taxes to support their new neighbors (Hanson et al., Reference Hanson, Scheve and Slaughter2007). Or, citizens might believe that their region's economy will decline (Citrin, Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997). Citizens may also be concerned about changes in their group status or see changes in the ethnic composition of their home as a threat to their social position (Sniderman et al., Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004; Brader et al., Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay.2008; Enos, Reference Enos2014). This feeling of threat or disruption may be especially pronounced when citizens have relatively limited interactions with the immigrants (Dinas et al., Reference Dinas, Matakos, Xefteris and Hangartner2019; Hangartner et al., Reference Hangartner, Dinas, Marbach, Matakos and Xefteris2019; Steinmayr, Reference Steinmayr2021).

The effect of immigration on a citizen's perceived welfare may also be different for different types of immigration events and in different receiving communities. Citizens may develop more positive attitudes toward immigrants after prolonged exposure, especially when citizens and immigrants interact as equals and with a common purpose (Allport, Reference Allport1954; Pettigrew, Reference Pettigrew1998; Paluck et al., Reference Paluck, Green and Green2019; Steinmayr, Reference Steinmayr2021). Further, citizens may only feel threatened by people they see as different when they are in very close contact (Enos, Reference Enos2016). Finally, when national politics is not focussed on immigration, or when a community is already home to a diverse population including people who share a culture with the new migrants, citizens may feel less threatened by recent immigration (Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Reingold, Walters and Green1990; Taylor, Reference Taylor1998; Cain et al., Reference Cain, Citrin and Wong2000; Dixon and Rosenbaum, Reference Dixon and Rosenbaum2004; Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2010; Newman, Reference Newman2013; Reny and Newman, Reference Reny and Newman2018).

If, taking this all into account, voters feel they are worse off because of immigration into their community, they may punish incumbent politicians for this change. This can happen whether voters are backward-looking, punishing candidates for poor performance (Key, Reference Key1966; Fiorina, Reference Fiorina1981), or forward-looking, favoring the politicians who will make them better off going forward (Fearon, Reference Fearon1999; Ashworth, Reference Ashworth2012). In the first case, citizens may develop the heuristic of voting against incumbents when they are worse off because it is simpler than prospectively calculating which politician will bring them the highest returns. In the forward-looking version of the model, voters use information from the past performance of incumbents to infer how the incumbent is likely to perform where they returned to office. While these models are quite different, both models predict that an incumbent will receive fewer votes when she has made voters worse off.

Still, voters may not always punish candidates when they are made worse off. Citizens may do a bad job of assigning blame for why they are worse off (Healy and Malhotra, Reference Healy and Malhotra2013; Achen and Bartels, Reference Achen and Bartels2017). Citizens may also focus on what candidates are going to do in the future not what they have delivered in the past (Downs, Reference Downs1957).

Put together, this theory suggests that citizens are more likely to punish incumbents for large, acute, disruptive migration events, especially when citizens have only brief interactions with the immigrants or when these interactions fail to bring citizens and immigrants together with a shared purpose. But, even with such an event, the conditions under which the effects will be large, small, or nonexistent vary considerably based on the model.

2.2 Selective migration threatens many designs

Migrants choose whether to leave and where to settle by weighing how attractive their home is relative to alternatives abroad. This means immigrants will, all else equal, move to places with better economies and better opportunities for their children (Sjaastad, Reference Sjaastad1962; McKenzie and Rapoport, Reference McKenzie and Rapoport2010; Mahajan and Yang, Reference Mahajan and Yang2020; Abramitzky et al., Reference Abramitzky, Boustan, Jácome and Pérez2019). If citizens reward incumbents for good economies, and punish incumbents for higher rates of immigration, the choice of immigrants to move to places with good economies will confound cross-sectional estimates of the effect of immigration—even if the effect of immigration is to reduce incumbent vote shares, places with more immigration may vote for incumbents because they have better performing economies.

This same selection bias appears over time as well. Immigrants are most attracted to a place when its economy is improving, inducing a within-county, over-time correlation between immigrant population size and economic performance. Citizens may also reward incumbents for periods of good economic performance. These two factors together mean that a standard difference-in-differences estimate of the effect of changes in the immigrant population on changes in incumbent vote share will be negatively biased.

2.3 To remove selective migration as a confound, study a forced migration event

One way to minimize the risk that migrants are moving because conditions have gotten much better in the receiving community is to find cases of forced migration. When a war breaks out or a natural disaster strikes, refugees may have to trade away quality for convenience in deciding where they go first. Their final destination may even be determined for them and selected based on availability rather than fit (Bansak et al., Reference Bansak, Ferwerda, Hainmueller, Dillon, Hangartner, Lawrence and Weinstein.2018). Accordingly, refugee flows offer a particularly plausible natural experiment for estimating the impact of migration on the votes of native-born citizens (Becker and Fetzer, Reference Becker and Fetzer2016; Tabellini, Reference Tabellini2018; Dinas et al., Reference Dinas, Matakos, Xefteris and Hangartner2019; Dustmann et al., Reference Dustmann, Vasiljeva and Damm2019; Steinmayr, Reference Steinmayr2021).

The same logic holds for cases in which migrants who were previously unable to migrate are suddenly allowed to move. In this case, it is plausible that the migrant was not motivated to move by the quality of the labor market in their new home at the exact time they moved. Rather, they would have moved to this place at any time in recent years, but they were unable to due to a policy barrier.

2.4 Sharp changes in local politics threaten difference-in-differences designs and the synthetic control method

If changes in economic performance are relatively smooth over time and immigration happens in bursts, approaches like the synthetic control method, trajectory balancing, and similar procedures, which find control units on similar trends to the places that received an immigration shock, overcome the bias in a standard difference-in-differences design (Abadie et al., Reference Abadie, Diamond and Hainmueller2010; Doudchenko and Imbens, Reference Doudchenko and Imbens2016; Xu, Reference Xu2017; Athey et al., Reference Athey, Bayati, Doudchenko, Imbens and Khosravi2018; Hazlett and Xu, Reference Hazlett and Xu2018). But if there are important changes coincident with the immigration event in the places that received the immigrants, difference-in-differences designs and more flexible approaches like the synthetic control method will both be biased. A classic example of this comes from medicine—when two drugs are administered simultaneously, the experiment cannot reveal which drug is responsible for any changes observed in the treated patients.

Occassionally, though, this type of bias can be quite subtle. This is especially true when studying the effect of migration on politics. Migrants often move to places that already have large populations of expatriots from their home country. For example, most immigrants and refugees fleeing Cuba moved to southern Florida where Cubans already made up a large share of the population. Studying the effect of migration on Republican presidential vote share, the synthetic control method identifies parts of the US where the migrants did not move that, on average, have the same voting patterns as the place that received the migrants. Still, the region receiving the migrants often has many more expats from the sending country than nearly any other region in the US. If the expats from that sending country shift their politics sharply at the same time as the migration event but for reasons unrelated to the migration event, this shift may be mirrored in the counties that make up the synthetic control, making the synthetic control method a biased estimator.

As I explore in Section 4, this is an especially important threat to the synthetic control method when used to study the Boatlift given how large the Cuban population was in Miami in 1980 compared to every other US county and how quickly Cuban-American politics were changing during that period.

2.5 Case: Mariel Boatlift when 125,000 Cubans fled to US through South Florida

In this paper, I study the case of the Mariel Boatlift in which approximately 125,000 Cubans fled to South Florida following a change in Cuban domestic politics (Duany, Reference Duany1999; Garcia, Reference Garcia1996). Between 1973 and 1980, only a small number of Cubans made it to the US. The constraints that the Cuban government placed on exit appear to have led to pent up demand. After thousands of Cubans seeking asylum took over the Peruvian embassy in the spring of 1980, the Cuban government opened the Mariel harbor, just west of Havana, to ships coming to pick up Cuban citizens. Roughly 125,000 Cubans—over 1percent of the Cuban population at the time—fled to the US between April and September 1980, the vast majority of whom traveled through Key West and Miami, Florida for processing. Sixteen percent of all Cubans living in the US in 1990 arrived during this period. Sixty percent of Boatlift migrants were living in Miami-Dade County as of 1990, and no other county received more than 4 percent. This influx accounted for a roughly 4 percent increase in Miami-Dade's population and a 40 percent increase in Miami-Dade's Cuban population from the 1980 census, taken before the Boatlift when Cubans made up 25 percent of the population, to the 1990 census.

The fact that the timing of the Boatlift was a consequence of Cuban politics rather than changes in Miami-Dade makes it a good case. As I discussed in Section 2.2, the timing of the immigration into South Florida is not a consequence of changing political conditions in Miami making it unlikely to be coincident with a sharp change in political conditions in Miami in the absence of the Boatlift. Importantly, this does not rule out changes in the economy over time that are different from the average county in the US, but the synthetic control method and selecting appropriate comparison counties to use for the difference-in-differences design overcomes this issue by building a counterfactual Miami that is on a similar trend.

The fact that nearly all of the Mariel refugees reached the US by boats that could only travel short distances also suggests that Miami-Dade was not a strategically chosen landing spot. Instead, nearly all Cuban refugees had to at least pass through Miami during the height of the 1980 election. Again, this does not guarantee that Miami-Dade would be experiencing the same political changes in the absence of the Boatlift, but it rules out important and obvious forms of immigrant selection into communities that are experiencing rapid economic improvement relative to the rest of the country.

I focus my study on the effects the Boatlift had on the 1980 presidential election. The migrants came to the US at the height of the campaign. The president at the time of the Boatlift, Democrat Jimmy Carter, was facing a difficult reelection bid with a struggling national economy and intra-party competition from two popular politicians, Ted Kennedy and Jerry Brown. Carter faced former California Governor Ronald Reagan in the general election. Reagan positioned himself as the strong anti-communist candidate. As president, Carter was responsible for overseeing the national response to the Boatlift.

Carter's response to the Boatlift changed over time, making him appear unsteady and unprepared.Footnote 3 He began by welcoming all of the refugees. When Cuban President Fidel Castro announced that he would be releasing prisoners to join the refugees in fleeing Cuba, Carter reversed course and announced an unsuccessful blockade to stop Cubans from fleeing. The standard procedure of processing refugees outside of the US was impossible in this case, moving the processing to the US and creating new logistical challenges previous administrations had not faced when admitting refugees. The Carter administration set up camps in Miami to process the refugees and offer them assistance, meaning that Miami residents were first-hand observers of the disruption from these unexpected logistical hurdles. Ultimately, the Boatlift ended when Castro closed the port, opening up Carter for attack by allowing Castro to dictate who enters the US and when rather than US policy.

Reagan began the Boatlift by tying the crisis to his anti-communist stance, saying that the crisis is a reflection of how many Cubans seek a new life and advocating for aggressive measures to help extract them.Footnote 4 But, he also used the opportunity to criticize his opponent's performance. By the end of the presidential campaign, Reagan's campaign criticized Carter with his vice presidential runningmate, George H W Bush, saying we “we need a national policy dealing with all refugees that is set by the United States and not by Fidel Castro” and that the US “just can't accept everyone.”Footnote 5

While this event is useful for studying political accountability for local immigration, the event is less useful for understanding contemporary hostility toward immigrants. Immigration and refugee policy were much less polarized in 1980 than they are today, making it more difficult to map changes in anti-immigration attitudes onto changes in voter behavior. In other words, because the parties held similar positions on immigration policy, an analyst cannot infer a voter's views on immigration policy from their vote choice in the 1980s. I test this empirically in Table A.1 in the Appendix. I find that, while supporters of admitting more Cuban refugees were more likely to support Carter than Reagan, supporters of admitting more Vietnamese refugees or refugees in general were about as likely to support Reagan as those who favored barring most refugees. This stands in contrast to a substantial gap on immigration policy views between Republican and Democratic voters today. The public has also become more favorable toward immigration policy over time according to Gallup surveys conducted repeatedly from 1966 to today.Footnote 6 This suggests that citizens might be less likely to punish politicians for local immigration in 2020 when compared to 1980.

Another key challenge with using the Boatlift to estimate the effect of immigration on support for incumbents is that Miami had a much larger Cuban voting population than any other county in the US. If the difference between Democratic and Republican presidential candidates changes over time in ways that led Cubans to vote differently, the simple county-level aggregate analyses would not account for this and would incorrectly interpret these changes as a consequence of the Boatlift rather than changes in Cuban voting everywhere. In other words, a change in Miami's presidential voting relative to similar counties could be part of a national change in Cuban-American politics that did not impact the voting behavior of other communities. Even the flexible panel techniques will likely not be able to adjust for this.

We also know that Ronald Reagan was an especially vocal supporter of the anti-communist and anti-Castro cause. If Cuban voters were especially drawn to the way Reagan made anti-communist foreign policy a central part of his platform, more so than prior Republican presidential candidates, we could see an increase in support for Republicans in 1980 in Miami that was not at all a consequence of the mass migration into Miami happening at the same time.

In generalizing beyond the case of the Boatlift, it is important to note the differences between the Boatlift and more recent refugee crises. While the Syrian refugees either had minimal interactions with natives that led to anti-immigrant hostility (e.g., Hangartner et al., Reference Hangartner, Dinas, Marbach, Matakos and Xefteris2019) or had prolonged interactions with natives that led to more favorable views of the refugees (e.g., Steinmayr, Reference Steinmayr2021), the majority of the Cuban refugees moved in permanently but had only been in Miami for a short period by the time of the election. The Cuban refugees also lacked a formal status. Given these conditions, I interpret the Boatlift more as a case of intergroup exposure than a case of intergroup contact and would expect the effect to be negative were one to exist.

3. Miami's Republican presidential vote increased after the Boatlift

3.1 County-level presidential election data

To study the effects of the Mariel Boatlift on presidential voting, I obtained results for every presidential election from 1960 through 2000 for nearly every county from the Congressional Quarterly elections results database. This data covers 3060 of the 3142 counties in the US, with 82 missing due to historical gaps in the data. I add to this dataset population estimates for each county based on the 1980 decennial census.

3.2 Design: compare Miami after the Boatlift to counties with similar vote histories

Putting aside concerns about a national shift in Cuban-American politics for the moment, I begin by using a number of flexible panel techniques to estimate how much Miami punished the incumbent President Carter. I break this into two steps.

First, I look for a set of counties to which I can compare Miami-Dade. Of course, it is natural to compare Miami-Dade to all counties in the US and to all other Florida counties, and I do so.Footnote 7 As an additional check, I look for a set of counties most likely to be on the same trend in terms of voting behavior as Miami-Dade. Given the rural-urban split in voting patterns in recent decades, I expect Miami-Dade County voters to respond to national events more like other urban counties throughout the US than other counties in Florida or the average county in the US. Accordingly, I use population estimates from 1980 to rank counties based on how similar their population is to Miami-Dade's. First, I report difference-in-differences estimates of the effect of the Boatlift using ex ante plausible sets of similar counties (250 and 500). I then estimate the use of the presidential elections from 1960 to 1976 to estimate a placebo effect in 1976—pretending as though the Boatlift had happened four years earlier—and measure the placebo effect for every potential control county population threshold (e.g., using a control pool of the ten counties most similar to Miami-Dade in terms of population then the 15 most similar counties, then the 20 most similar counties, and so on). Since this placebo effect should be zero, I find the number of comparison counties that minimizes the square placebo effect: 1500 counties. I report the estimated effect of the Boatlift using this control pool as well.Footnote 8

Once I have a pool of candidate counties, I estimate the impact of the Mariel Boatlift on Republican presidential vote percentage using a panel regression with election and county fixed effects of the form

where $V_{it}$![]() is the Republican presidential vote percentage in county $i$

is the Republican presidential vote percentage in county $i$![]() at time $t$

at time $t$![]() , $M_{it}$

, $M_{it}$![]() is a dummy variable that takes on the value one for Miami-Dade in 1980 and after zero otherwise, $\alpha _i$

is a dummy variable that takes on the value one for Miami-Dade in 1980 and after zero otherwise, $\alpha _i$![]() is a county fixed effect, $\gamma _t$

is a county fixed effect, $\gamma _t$![]() is an election fixed effect, $\epsilon _{it}$

is an election fixed effect, $\epsilon _{it}$![]() is a residual, and $\tau$

is a residual, and $\tau$![]() is the estimated shift in support for the Republican presidential candidate.

is the estimated shift in support for the Republican presidential candidate.

I also estimate the effect using the synthetic control method, which was designed with this type of case study in mind (Abadie et al., Reference Abadie, Diamond and Hainmueller2010, Reference Abadie, Diamond and Hainmueller2015). The synthetic control method constructs a weighted average of the vote patterns among the control counties. The weights are selected to minimize the difference between the weighted average of presidential vote in control counties and Miami-Dade before the Boatlift. The weights are restricted to fall between zero and one so that the synthetic control is not an extrapolation beyond the support of the control pool.

Formally, I consider a pool of $N$![]() potential contributor counties to the synthetic control indexed by $i$

potential contributor counties to the synthetic control indexed by $i$![]() where $i = 0$

where $i = 0$![]() represents Miami-Dade. I use $T$

represents Miami-Dade. I use $T$![]() pre-treatment observations to select the weights. I represent the pre-treatment outcome data as a matrix $K_0$

pre-treatment observations to select the weights. I represent the pre-treatment outcome data as a matrix $K_0$![]() for the control pool counties and a vector $K_1$

for the control pool counties and a vector $K_1$![]() for Miami-Dade. I select the vector of weights $W$

for Miami-Dade. I select the vector of weights $W$![]() such that

such that

Using the same control pool selection procedure as before (estimating a placebo effect for Miami-Dade county in 1976), I select a threshold of 555 control counties for the synthetic control method.Footnote 9

3.3 Difference-in-differences estimates

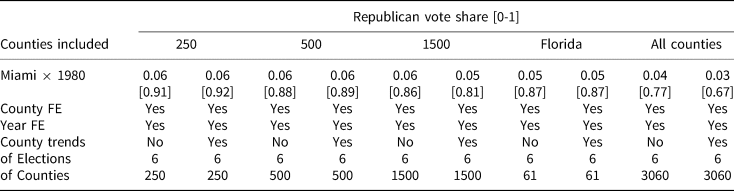

Table 1 presents the results of the difference-in-differences analysis. Each cell in the table reports an estimate of the increase in Miami vote for the Republican presidential candidate in 1980, the year in which the Boatlift took place, after differencing out the change in support for Republican presidential candidates in counties similar to Miami-Dade. Columns 1through 4 report estimates based on an ex ante plausible set of comparison counties: the 250 and 500 counties nearest to Miami-Dade in terms of population. I also adjust for county-specific time trends in columns 2 and 4 to account for differences in the paths that Miami-Dade and the comparison counties were on prior to the Boatlift. In columns 5 and 6, I report the fixed effects estimates using 1500 counties in the control pool, which minimized the forward prediction error for the 1976 presidential election, first without and then with county-specific time trends. In columns 9 and 10, I present the estimates using all counties. And, in columns 7 and 8, I report the fixed effects estimates after restricting the control pool to include only Florida counties. The last four columns report the least plausible estimates since many of the counties in the control pools are rural counties where political preferences tend to be quite different from those held by residents in Miami-Dade and where Republican support is increasing through this period. In the absence of meaningful analytic standard errors, I report where the estimated effect lies in the distribution of placebo effects (Abadie et al., Reference Abadie, Diamond and Hainmueller2010; Doudchenko and Imbens, Reference Doudchenko and Imbens2016). This distribution of placebo effects under the null comes from estimating a placebo effect for every county included in the analysis, using the same regression as I use to estimate the effect for Miami-Dade, but holding out Miami-Dade.

Table 1. Increase in Republican presidential vote share in Miami-Dade county following the Mariel Boatlift, fixed effects estimates

Each cell reports an estimate of the increase in support for Ronald Reagan over Jimmy Carter in the 1980 presidential election. All estimates calculated holding out counties that border Miami-Dade. Columns 250, 500, and 1500 are estimated with the 250, 500, and 1500 counties most similar to Miami-Dade in terms of log population as of 1970. The share of the placebo distribution less than the effect estimate is reported in square braces.

Despite the wide variety of control pools I use, all of my fixed effects estimates imply an increase in the percentage of Miami-Dade voters supporting Reagan in the 1980 presidential election relative to what we would expect based on the support for Reagan in other counties. Still, these estimates are noisy, and there is reason to think that the counterfactual trends implied by these estimates may not be right. This is particularly likely in the case of the Florida-only and all-county columns. In order to impute a more plausible counterfactual trend for Miami-Dade, I turn to the synthetic control method.

3.4 Synthetic control estimates

Figure 1 presents observed and synthetic Miami-Dade Republican presidential vote share from 1960 to 2000.Footnote 10 As intended in the construction of the weights, the synthetic Miami-Dade is nearly identical to the true Miami-Dade prior to the election in 1980, at which point they separate.Footnote 11 This post-Boatlift split translates into a roughly 7-percentage-point increase in Republican presidential vote share in 1980.

Fig. 1. Synthetic control method estimate of Mariel Boatlift impact on Republican presidential vote share.

As I described in the previous section, I conducted a placebo analysis for each of the remaining roughly 550 counties that I used in the construction of the Miami-Dade synthetic control, following the advice of Abadie et al. (Reference Abadie, Diamond and Hainmueller2010) and Doudchenko and Imbens (Reference Doudchenko and Imbens2016). I find a synthetic control for each of these counties which allows me to construct a null distribution from the placebo impacts. In Figure 2, I present the results of this analysis. The dark line represents the synthetic-control-method-estimated impacts for Miami-Dade and the light grey lines reflect the placebo impacts for all of the remaining counties.

Fig. 2. Miami-Dade synthetic control-estimated impacts against distribution of Placebo impacts.

Figure 2 clearly shows that the change in support for Republican presidential candidates after 1980 that Miami-Dade exhibited was near the edge of the range of null effects, particularly in the first few years after the Mariel Boatlift. The average estimated change in Miami-Dade County across the six elections following the Boatlift is at the 96th percentile of the average placebo impacts represented in this figure, suggesting that these estimated impacts are very unlikely to be a purely chance event. I further infer from this analysis that the standard deviation of placebo change is 4.0 percentage-points, suggesting that, though this roughly 7-percentage point change is large relative to the null distribution, it is still a noisy estimate.

In Table A.2 in the Appendix, I report the estimated shifts toward Republican presidential candidates for six presidential elections held after the Mariel Boatlift. In the first column, I present the synthetic control estimates based on a control pool of 250 counties. In the second column, I present the results based on the control pool size selected by minimizing a moving average of mean squared forward prediction error, which is 555. I find a 6.7 percentage-point shift toward Republicans in 1980 using the control pool of 250 counties, and a 7.0 percentage-point shift using a control pool of 555 counties. I also present, in the third column, estimates from a synthetic control selected using only Florida counties. Visual inspection of the synthetic control for Miami-Dade prior to 1980 reveals that Miami-Dade lies outside of the convex hull of pre-1980 Republican presidential vote share for other Florida counties, and they may not offer a useful counterfactual. Nevertheless, Miami-Dade still shifted more toward Reagan than would be expected when compared to the weighted average of Florida counties most similar to Miami-Dade before 1980. All three estimates fall above the 90th percentile of their empirical placebo distributions.

As I indicated above, one important methodological concern I have about these analyses is that the synthetic control or fixed effects regressions may be fit on the wrong set of counties. To address this concern, I estimate the shift toward Republicans using a large variety of control pools with both the synthetic control method and fixed effects regressions. Figures A.2 and A.3 in the Appendix present the results. The synthetic control estimates are noisy, but all of the estimates with both techniques are positive.

The results above suggest that voters in Miami-Dade County supported Republican presidential tickets after 1980 more than we should expect based strictly on prior election results. Very few similar counties moved more toward the Republican party in 1980. One plausible explanation for this shift is that white and black Miami-Dade residents punished Carter for permitting the Boatlift migrants to come. Workers who compete with the Marielitos for jobs may also have punished Carter. But are not the only workable stories.

Miami's demographics offer an alternative explanation: Since Miami has a uniquely large Cuban population, might the unusually high support for Reagan reflect a Cuban political realignment unrelated to exposure to the Boatlift? Miami's Cuban-American population prior to the Boatlift was composed of disproportionately high earners and are less likely to consider Cuban refugees an out group, suggesting that these voters are least likely to punish incumbents for exposure to immigration under most models. But Jimmy Carter's response to events shortly preceding the election, including the Boatlift and Soviet troops being discovered in Cuba, could have led voters who cared a lot about Cuban-American relations to vote for Reagan. Any shift in Cuban-American politics will confound the estimates I reported above. If the shift is large enough, a positive estimate could be consistent with the Boatlift having no local effect of even with it increasing support for Carter.

Looking at Figure A.2, the fact that Miami-Dade continues to deviate from its synthetic control for many years after 1980 does not fit with the explanation that citizens are voting against an incumbent whose performance they disliked. Instead, this is more consistent with a persistent change in support for the Republican party. I present evidence for this alternative explanation in the next section.

4. Increased Cuban-American support for Reagan, not exposure to the Mariel Boatlift, explains the change in Miami

The results above are consistent with two very different stories: either the Boatlift had an effect on support for Reagan in Miami-Dade, or something else happened in Miami-Dade between 1976 and 1980 that changed support for Republican presidential candidates relative to other similar counties. The most likely alternative explanation is that voting-eligible Cubans throughout the country shifted from Carter in 1976 to Reagan in 1980 in large numbers because of Reagan's vocal anti-communist and anti-Castro stances or some other set of positions or work of political organizations. Since Miami-Dade has a larger Cuban population than any other county in the US—three times greater than the second largest Cuban population in the US—Miami-Dade would change much more than any other county if Cubans shifted dramatically to Reagan in 1980.

Below, in three steps, I present evidence that a national shift in Cuban politics, not the Boatlift, was responsible for the shift toward Reagan in Miami-Dade in 1980. First, I demonstrate that the shift toward Reagan in Cuban neighborhoods was large enough to account for the entire shift to Republicans in Miami-Dade. Second, I present evidence that the Cuban neighborhoods in Hudson County, New Jersey, a county that was not directly exposed to the Boatlift, shifted to Reagan at the same rate as Cuban neighborhoods in Miami. Finally, I present evidence that this Cuban shift was specific to the presidential elections, finding that the change in support for Republican US House candidates from 1976 to 1980 in Miami was similar in neighborhoods with more and fewer Cuban voters.

4.1 Estimating neighborhood-level Cuban population and Republican vote

As a first step in investigating whether a change in Cuban voting was responsible for the shift toward Reagan in Miami-Dade, I used public records requests to obtain historical precinct-level election results from the Miami-Dade County Elections Department. This data, which covers all Miami-Dade County elections from 1976 to 1992, allows me to allocate county-wide changes in voting to particular parts of town. Unfortunately, Miami-Dade does not use consistent or informative precinct labels. This means that often I cannot identify the same precincts or even neighborhoods from one election to the next. Fortuitously for this project, the precinct numbering system stayed the same from 1976 to 1980, and all precincts in nine neighborhoods housing approximately 65 percent of the city of Miami's residents are flagged with their neighborhood names.Footnote 12

I pair my estimates of each neighborhood's two-party vote share with estimates of the Cuban, non-Latin black, non-Latin white, and total population. I construct these estimates by aggregating block-level 1980 census counts to the neighborhood level using Zillow's Florida neighborhood shapefile and the IPUMS NHGIS 1980 block shapefile (Manson et al., Reference Manson, Schroeder, Riper and Ruggles2017).Footnote 13

As a robustness check, I also present estimates using precinct-level data on the share of registered voters in a precinct who are Hispanic as a proxy for the Cuban population. While this measure is not as closely connected to the core group and is measured in 1981, it has the advantage of being at the precinct-level, removing any error introduced in the process of linking historical precincts to neighborhoods.

4.2 Shift toward Reagan concentrated in Cuban neighborhoods

I estimate the increase in Republican presidential vote share among Cubans using my neighborhood-level and precinct-level panel data. I run regressions of the form

where $V_{it}$![]() is the Republican presidential vote share in neighborhood or precinct $i$

is the Republican presidential vote share in neighborhood or precinct $i$![]() at time $t$

at time $t$![]() , $C_{it}$

, $C_{it}$![]() is the Cuban share of the neighborhood or precinct's population, $\alpha _i$

is the Cuban share of the neighborhood or precinct's population, $\alpha _i$![]() is a neighborhood or precinct fixed effect, $\gamma _t$

is a neighborhood or precinct fixed effect, $\gamma _t$![]() is an election fixed effect, $X_{it}$

is an election fixed effect, $X_{it}$![]() is a vector of time-varying controls, $\epsilon _{it}$

is a vector of time-varying controls, $\epsilon _{it}$![]() is a residual, and $\lambda$

is a residual, and $\lambda$![]() is the estimated shift among Cubans relative to other groups.

is the estimated shift among Cubans relative to other groups.

This regression compares the increased support for Republicans in more Cuban neighborhoods to that same increase in less Cuban neighborhoods. Putting aside concerns about ecological inference for the moment, by including controls, I change the comparison group. For example, including the interaction of a dummy variable for 1980 and the non-Latin white share of the neighborhood's population makes citizens who are not either non-Latin white or Cuban the comparison group.

Table 2 presents the estimates from these regressions. I find that, relative to three groups of other Miami residents, a hypothetical neighborhood with 10 percentage points more of the population with Cuban backgrounds swung toward Republicans by about 2.5 percentage points. Column 4 finds a similar pattern using a completely separate measure of Cuban population: the share of registered voters who self identify as Hispanic. Of course, this includes non-Cubans who identify as Hispanic, but since Cubans made up a substantial majority of the Hispanic population in Miami-Dade in 1980, this in an encouraging robustness check. Figure 3 further shows that this is being driven by neighborhoods and precincts that are overwhelmingly Cuban swinging to Reagan by massive margins.

Fig. 3. Large shift toward Republicans in Miami by Cuban population.

Table 2. Large shift toward Republicans among Cubans in Miami

Block bootstrapped standard errors from 1000 samples are reported in parentheses below each estimate. All population share variables, including the Cuban population share and the share of registered voters who are Hispanic, range from zero to one.

An effect this size is large enough to explain the entire 7-point gap between Miami-Dade and its comparison units that I found in Section 3. In other words, these effects are large enough to imply that exposure to the Mariel Boatlift had no effect on votes for Reagan in 1980 Miami-Dade. If we assume that the estimates I report in the Section 3 are unbiased for the total shift toward Reagan due to the combined effect of the Boatlift and national Cuban-American political changes, we can back out how large the change in Cuban-American voting would have to be for the local effect of the Boatlift to be null. Only an exceptional shift in Cuban-American politics could produce such a large swing toward Republicans in Miami-Dade as a whole. Miami-Dade's synthetic control supported Reagan in 1980 by about 3 percentage points more than it did Ford in 1976. Miami-Dade supported Reagan by almost 10 percentage points more than Ford. Let us assume for simplicity that Cubans vote at about the same rate as other residents in Miami-Dade and that turnout did not change from 1976 to 1980. Let us also assume that Cubans were entirely responsible for the shift toward Reagan and that non-Cuban Miami-Dade voters followed the synthetic control. This would mean that 25 percent of the population would have to account for a 7-percentage-point change in the vote, implying that 28 percent of Cubans in Miami-Dade would have to switch from Carter in 1976 to Reagan in 1980. This is almost identical to the estimated swing based on the regressions reported in Table 2.

4.3 Similar increase in Republican support among Cubans in Miami and elsewhere

Increased support for Republicans in Miami-Dade among Cubans rather than white or black citizens could be a response to a changing political environment like Reagan's anti-communist stance or Carter's response to Cuban and Soviet behavior. But it could still be a consequence of exposure to the Boatlift that is isolated among Cubans or in Cuban neighborhoods. To arbitrate between these two explanations—a local, exposure-driven change in Cuban voting versus a national political change that pushed Cubans toward Reagan—I compare the Cuban shift in Miami to the Cuban shift in the county with the second largest Cuban population in the US, Hudson County, New Jersey.

To make this comparison, I gathered precinct-level presidential election results for Hudson County from the New Jersey State Archives. I obtained the results for the 1976 and 1980 presidential elections. I also worked with the Hudson County Division of Planning to gain access to election district maps. I construct ward-level and city-level demographic estimates in Hudson County using the same procedure I use to construct neighborhood-level estimates in Miami. Since the ward boundaries may have changed in ways my maps do not account for, I run all analyses separately at the city level as a robustness check.

With this paired demographic and presidential election data, I estimate the difference in the shift toward the Republican presidential ticket among Cubans between Miami and Hudson County. I report these results in Table 3. In the first column, I find that if one city in Hudson County has a Cuban population that makes up five percentage points more of its total population than another ward, it should have shifted toward Republicans in 1980 by about one- percentage-point more. This difference is slightly larger in Miami, where it only takes a four-percentage-point difference in Cuban population share to expect one-percentage point larger shift toward Republicans.

Table 3. Similar shift toward Republicans among Cubans in Miami and Hudson county

Adjustments for particular subpopulations is done by including two additional vairables in the regression: an interaction between the subgroup's population share with a flag indicating that the year is 1980 and separately the subgroup's population share interacted with a flag for 1980 and Miami. Block bootstrapped standard errors from 1000 samples are reported in parentheses below each estimate. All population share variables, including the Cuban population share, range from zero to one.

Since an increase in the Cuban population share means a decrease in some other population share, these regressions are estimating how much more a neighborhood with more Cubans, rather than non-Cubans, shifted toward Republicans in 1980. The non-Cuban population in the Miami neighborhoods in my data may have a different demographic profile than the non-Cuban population in Hudson County. I deal with this in columns 2 and 3 by adjusting for the share of the neighborhood or city that identifies as non-Latin black and non-Latin white, respectively. Given the small sample, these adjustments make the estimates even noisier, but the results are still consistent with Hudson County Cubans shifting toward Reagan by slightly less than Miami-Dade or perhaps even more than Miami-Dade. Columns 4 through 6 report estimates from the same regressions reported in columns 1 through 3 but using ward-level rather than city-level data in Hudson County. The results from these analyses are similar to the city-level results, but slightly less noisy.

These results suggest that the large shift toward Republicans in 1980 in Miami-Dade County may be an artifact of its unique demographics. This does not rule out the importance of the Boatlift as an event for Cuban politics in the US. But it suggests that Miami's unique exposure to the mass migration event was not the primary driver of this shift.

4.4 Shift toward Reagan, not all Republicans and not all challengers

The evidence in the Sections 4.2 and 4.3 suggests that nearly all of the shift toward Reagan in Miami-Dade was a consequence of changes in Cuban politics. There are two plausible explanations for this shift: Cubans punished incumbents for generally bad conditions, or something specific about Reagan and Carter led many Cubans to switch their support to Reagan in 1980. These two explanations are equally consistent with the pattern of presidential election returns I have presented this far. Was the Cuban shift to Reagan and anti-incumbent vote or a specific vote for Reagan?

I answer this question by extending my Miami-Dade precinct analysis to US House races. If Cubans switched to Reagan because they were voting against all incumbents, the three incumbent Democratic US House candidates should receive fewer votes in Cuban neighborhoods in 1980 than they did in 1976. If this switch in Cuban-American voting is indeed a response to Reagan's politics in particular, the increased support for Reagan should not translate into a drop in Cuban support for incumbent Democratic House members.

As I report in Table 4, I find that Cuban neighborhoods did not swing to Republican US House candidates more than other neighborhoods. This is markedly different from the swing in presidential voting. This result rules out a general switch away from federal incumbents due to exposure to immigration. Instead, the switch in Cuban neighborhoods is something specific to the presidential race, potentially a distinctly anti-communist presidential candidate in Ronald Reagan.

Table 4. No shift toward Republican house candidates among Cubans in Miami

Block bootstrapped standard errors from 1000 samples are reported in parentheses below each estimate. All population share variables, including the Cuban population share, range from zero to one.

Table A.4 reports a formal comparison between the shift to Reagan against the shift to Republican US House candidates, and the difference in those slopes is quite clearly not zero or close to it. This makes clear that the changes in voting in Miami from 1976 to 1980 were exclusively about presidential politics rather than general increase in support for Republican candidates or ideology.

4.5 Alternative explanations

Tables 2 and 3 make clear that neighborhoods in Miami and Hudson County shifted toward Reagan in proportion to the size of their Cuban population. I interpret this as evidence that the Cuban population itself was shifting. This is not the only explanation for the result. If non-Cubans living in Cuban neighborhoods shift toward Republicans, it is possible that this shift toward Republicans was driven by non-Cubans living in Cuban neighborhoods. I cannot rule this out using my aggregate data, and this explanation for the pattern is plausible. Many of the Boatlift migrants moved to or were processed in predominantly Cuban neighborhoods in Miami (Garcia, Reference Garcia1996). Those that moved to Hudson County mostly did so with family members, meaning that they moved to cities or wards that housed many Cubans before the Boatlift. This means that exposure to the Boatlift migrants was highest in Cuban neighborhoods. Punishment of Carter could, then, be largest in Cuban neighborhoods. For this to be true, the effect of exposure on non-Cubans’ propensity to switch to Republicans would have to increase dramatically between moderate and high levels of exposure. Also, the effect would have to be incredibly large: since neighborhoods that were nearly 80 percent Cuban shifted to Reagan by 15 percentage points, the effect would need to produce a nearly 75-percentage-point shift among white and black residents of Cuban neighborhoods. Given these facts, I attribute to Cubans the majority of this shift toward Reagan in Cuban neighborhoods.

Putting aside these concerns about ecological inference, one additional threat to the sub-county-level analysis is the difference in voting patterns of non-Cubans between Miami-Dade and Hudson County. This creates a problem because the regressions I am running estimate how much higher the shift toward Reagan is among more Cuban neighborhoods compared to less Cuban neighborhoods in the same county. If non-Cubans are meaningfully different in Miami and Hudson County, the within-county differences in the swing will be different as well. I take a small step toward addressing this in Table 3 by adjusting for the racial composition of the comparison group. Despite the noise in the estimates, these adjustments are still consistent with Cubans in Hudson County and Miami-Dade following similar paths. Still, there are likely remaining difference between the Cuban and non-Cuban populations across these parts of the country that influence the trend they are on, but I cannot adjust for this given the small number of periods I have in my data.

5. Final remarks

Does exposure to migration cause native-born voters to vote against incumbents? In this paper, I present a case in which even large-scale migration likely did not cause a large number of citizens to vote against the incumbents who allowed the refugees to come. I find that Miami-Dade voted for Reagan at a much higher rate than one would predict from prior election results, but that this change was likely due to a national change in Cuban-American politics, implying that it was not a consequence of local exposure to the Boatlift. Cubans throughout the country may have supported Reagan more than Ford because of Reagan's foreign policy platform or Carter's performance. Cubans—even those in other parts of the country who received few or no Boatlift refugees—may have even increased support of Reagan because they disliked Carter's handling of the Boatlift. Either way, my analysis does not support theories that predict voters in refugee-receiving communities will punish incumbents. Instead, my findings are consistent with a much more idiosyncratic and candidate-specific change in voting patterns.

Based on my newly collected precinct-level data, the shift of Cubans toward Reagan was significant and widespread. Further research studying what caused this shift is warranted.

The evidence I have presented throughout is only suggestive—my precinct-level analysis is not a perfect design for estimating the effects of migration by subgroup. But my robustness checks also clarify a risk to many analyses of the effects of immigration: most immigrants move to places with unusually high concentrations of expatriates from their country, making it difficult for the analyst to rule out changes in that population's voting unrelated to the immigration.

Acknowledgments

For helpful discussion and comments, the author thanks Justin Grimmer, Jens Hainmueller, Andy Hall, Dominik Hangartner, Apoorva Lal, Hans Lueders, Clayton Nall, Judith Spirig, Sarah Thompson, Yamil Valez, Vasco Yasenov, Jesse Yoder, and members of Stanford's Working Group on Empirical Research in American Politics. The author also thanks Ramon Castellanos of the Miami-Dade County Elections Department for providing historical election results, HistoryMiami for advice on mapping historic Miami neighborhoods, IPUMS for providing formatted Census microdata, Daryl Krasnuk of the Hudson County Department of Planning for sharing Hudson County ward boundary data, and Ralph Thompson for assistance gathering archived Hudson County election results. This research was generously funded by Stanford's Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/psrm.2021.76. To obtain replication material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EZ9DHK.