The French Revolution was widely regarded at the time as an unprecedented event. One unexpected consequence in London was the emergence of a remarkably rich and vibrant popular radical culture. Enthusiasm for this phenomenon may often steer my tone towards the celebratory, but this book aims to give a sense of the aspirations, complexities, and contradictions involved in the creation of a broad-based movement for radical change in Britain. The story of the radical societies has been told before, primarily by political historians, usually in relation to the unfolding of larger narratives of the struggle for parliamentary reform or the creation of working-class consciousness. Those narratives are important here, but my approach is particularly concerned with the emergence of popular radicalism through experiment, contestation, and performance, especially in its relations to the medium of print and the associational world that surrounded it. Print is taken in this book to have been a condition of possibility for a popular radical platform, creating the circumstances for London to act as the major clearing house of ideas and as the organisational centre of a movement spread across the four nations of Britain. Print made it possible to think of consulting and mediating what Thelwall called ‘the whole will of the nation’.1 Beyond their practical engagement with the medium, the participants themselves shared important assumptions and ideas about print, not least the deep faith they frequently showed in its efficacy as an agent of emancipation. This faith tended towards a form of magical thinking when it assumed a power in the medium regardless of causative relations.2

The passing of the Two Acts in 1795 severely curtailed the activities of the popular societies and provides a partial endpoint to this study. The Acts made it impossible for meetings of more than fifty people to gather without the explicit permission of a magistrate and increased the punishments for what were deemed seditious activities. Leaving aside the implications for the law of treason, so eloquently discussed by John Barrell, the Seditious Meetings Bill had grave repercussions for the kinds of events the LCS could undertake and the kinds of spaces it could operate in.3 There was a sense in the country at large that the guiding spirit of reform was being threatened with extinction, even though the LCS was not actually banned until 1799. In the build up to the 1795 legislation, Robert Sands wrote from Perth about the difficult part London had been given to play in what he called ‘the Comedy of Regeneration’:

We look up to the London Corresponding Society, and the Others who have affiliated with them. We know the whole depends on their exertions and that without them nothing can be done. It is an old doctrine of mine that the Metropolis is the same to a Nation as the heart is to the body: it is the seat of life. If it is pure the whole body must be so, and vice versa. If the Chanel [sic] of corruption is not stopt [sic] in London, you cannot expect it to be so in Perth or anywhere else.4

Relations between regional societies and those in London were not as straightforward or as deferential as this may sound. More than once even provincial English societies refused to comply fully with the protocols that the LCS sent them, as was the case with the Tewkesbury Society discussed in Chapter 2. The LCS itself was sometimes subject to internal conflict, for instance, when it came to relations between the executive and its divisions. Nevertheless these tensions themselves speak to the key role London played in the creation of a popular radical platform out of material practices embedded in complex social relations.

Placing this study within the series ‘Cambridge Studies in Romanticism’ implies an understanding of popular radicalism as a kind of ‘literary’ culture. At least, it argues for the centrality of the writing, production, and circulation of printed texts that took up so much of the time of the radical societies. If aspects of this approach are ‘literary’ in general terms, the book is not intended to provide a backdrop to Romanticism and its major poets, novelists, and playwrights.5 In certain respects, this formation and the associated identification of the literary with what John Thelwall called ‘sallies of the imagination’ were the product of a crisis brought on by the emergence of the popular radical culture opened up in this book, but the story is not a straightforward one. Thelwall himself could identify ‘literature’ both with a domain of imagination separable from politics and with print as the principal engine of emancipatory change.6 My aim has been to pay attention to the everyday labours of the radical societies in creating a public sphere through print and associated practices, from poring over the proper forms of addresses to be issued in their names to penning songs and toasts for tavern meetings.7 Robert Thomson’s efforts writing and collecting for the LCS songs – discussed in Chapter 2 – may represent an uncanny parallel to his brother George’s work with Robert Burns, but for all the reorientation to popular melodies in polite taste at this time political songs were rarely allowed into the realm of the ‘literary’.8 The lyrical or literary ballad, as Ian Newman has shown, was increasingly severed from the convivial space of the alehouse in the emergent cultural field scholars now identify with Romanticism.9 Ironically, for some members of the LCS, Francis Place among them, such activities were too raucous to be regarded as properly within the republic of letters. On these terms, the identification of ‘literature’ with improvement could separate it from Thomson’s songs and toasts just as effectively as the idea that it belonged primarily to an interiorised realm of the imagination.

In terms of those who frequented and created this culture, the picture that emerges is not one peopled solely by ‘the radical artisan’ often associated with E. P. Thompson’s Making of the English Working Class.10 This divergence may be accentuated by my focus on print and its associated practices, but it also speaks to a period when radical discourse was largely concerned with a split between the represented and the unrepresented, between a narrow identification of the political nation with the elite and a broader idea of ‘the people’.11 Many of the subaltern classes who involved themselves in the popular societies did not have easy access to the medium of print because they could not write or sometimes even read. Nevertheless, they frequently interacted with print by hearing pamphlets and newspaper paragraphs read aloud at meetings or joining in with songs that were circulated on printed sheets. The popular societies were made up of a broad social range from what Thomas Hardy called ‘the lower and middling class of society called the people’.12 The LCS’s collaboration for most of the period 1792–5 with the more polite Society for Constitutional Information (SCI) only further complicates these social issues.

Within this broad formation there were a number of ‘gentleman’ radicals, such as Joseph Gerrald, who were members of both societies. Gerrald became a flamboyant hero of the struggle in 1793; his fate – transportation to Botany Bay and an early death – made him a print celebrity to the radical societies in 1794–5 and beyond. Gerrald seems to have been associated with another gentleman, Robert Merry, an SCI member active in the collaborations with the LCS in 1792, even if he never joined the more popular society. Gerrald and Merry had both been students of Samuel Parr, ‘the Whig Dr. Johnson’, attended SCI meetings together in 1792, and came to know and be influenced by Parr’s friend Godwin. The progressive education both received from Parr seems to have taken fire at the French Revolution and driven them into contact with men from very different social backgrounds.13 Friends of Merry saw in this process – discussed in detail in Chapter 3 – a fundamental loss of social identity:

The change in his political opinions gave a sullen gloom to his character which made him relinquish all his former connexions, and unite with people far beneath his talents, and quite unsuitable to his habits.14

A more precipitous descent can be traced in Charles Pigott – tracked in Chapter 4 – with whom Gerrald and Merry both associated. By February 1794, isolated after being discharged from prison, Pigott was a member of the LCS, but also touting for as much hackwork as he could get, producing a spurious volume of scandalous memoirs and the scabrous attacks on aristocratic women in the Female Jockey Club, before his death from prison fever. His personal circumstances in 1794 may have driven Pigott further in this direction, but in terms of their later populist orientation it is worth noting that both he and Merry were using the newspapers to communicate their opinions from at least as early as the 1780s. They were well aware – as Merry put it to Samuel Rogers – of the effects of a ‘daily insinuation’ in the press.15

The popular radical movement often owned these elite activists with pride, not without serious reservations in Pigott’s case, but respect for literary talents with the pen did not simply translate into social deference. The shoemaker Thomas Hardy was the key figure of the 1792–4 period, prior to the treason trials. Highly literate, purposeful, and well read in the canon of English liberty, he learned from Scottish Presbyterian traditions that placed a high premium on modest confidence in one’s own abilities.16 Hardy doesn’t seem to have felt any desire to be known as an author or even the founder of the society. Thelwall, on the other hand, claimed for himself a genteel ancestry, and had already struggled to make a way for himself as a writer and editor after abortive careers as a silk mercer, a tailor, and a lawyer. Thelwall never abandoned his literary aspirations, even if at different times in his life they seemed to lie in a far from simple relation to his politics.

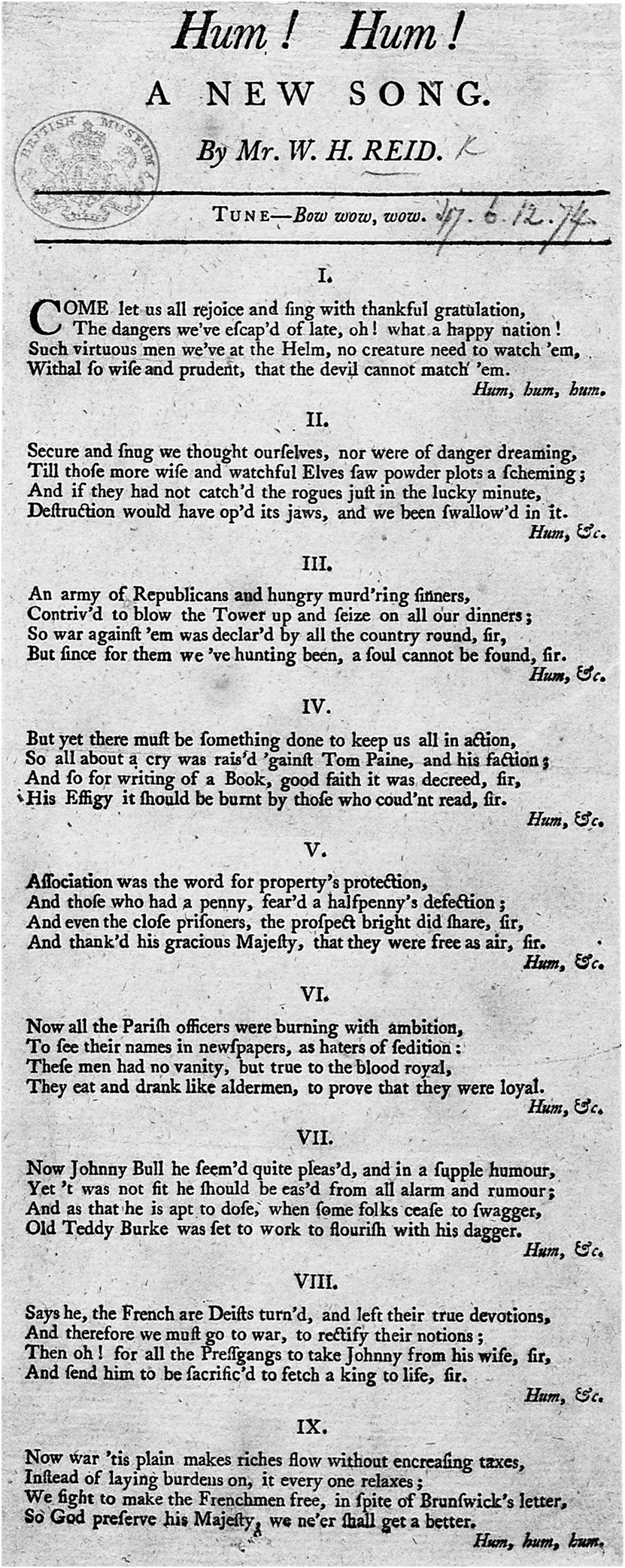

Others who merit more extended treatment than constraints of space will allow in this book include William Hamilton Reid. In the 1780s, Reid – ‘the son of persons occupying no higher status than that of domestic servants’ – had been puffed as the English Burns by the newspaper editor James Perry.17 He was soon supplying copy at a penny a line for the Gazetteer, especially translations of continental news, along with poetry and songs. For the LCS, where he was active from at least June 1792, he knocked out productions like ‘Hum! Hum! A New Song’ shown here (Figure 1). Reid seems to have seceded from the LCS in 1795 for religious reasons, joining the shadowy group sometimes known as the Society for Moral and Political Knowledge. Driven underground after the Two Acts, he was arrested at one of their meetings in February 1798. Even then he continued to pursue an aspiration to write, bringing out The rise and dissolution of the infidel societies in this metropolis (1800), with the support of the bishops of Durham and London, before turning his coat once again to publish a biography of the SCI leader John Horne Tooke.18

Fig 1 W. H. Reid, ‘Hum! Hum! A New Song’ [1793].

Religion remained an important aspect of print culture for W. H. Reid throughout his literary career, as it did for the clerk Richard ‘Citizen’ Lee, who first appeared in print as the religious poet ‘Ebenezer’, before the period of a few months transformed him into Citizen Lee, a journey traced more fully in Chapter 5. Thelwall, Reid, and Lee all aspired to authorship before they joined the popular societies. Others seem to have first found their voice via their involvement. John Baxter, for instance, followed up the pamphlet Resistance to Oppression (1795), discussed in Chapter 2, with A new and impartial history of England (1796) dedicated to the efforts of the LCS. Numerous others unknown must have written songs, helped frame addresses, and so on. Not all aspired to become authors; a few sustained a position as writers, several (or their widows) later applied to the Literary Fund for relief, including Reid and his fellow LCS songwriter Robert Thomson. Literary aspirations were not necessarily the equivalent of a desire for self-expression that placed a premium on the individual over the struggle. Men like Reid and Thelwall may have been first drawn to a career in print on the assumption that the republic of letters in its proper form was a sphere open to talents underwritten by the freedom of the press, but they soon discovered that this was far from the case and pressed for a more genuinely accessible domain.

In so far as they can be reconstructed from the archive, these backstories also indicate that the popular radicalism of the 1790s was the product of forces that reached back before 1789, even as they were crucially influenced by the sense of the French Revolution as an unprecedented event. The Revolution was both a sign such men had been expecting, a fulfilment of a spirit of progress they believed they were sustaining, and something that required them to rethink their relations to power. Synchronically, radicalism in the 1790s was not the expression of a coherent ideological code or language, but the product of the social practices of the surrounding culture reacting to events and ideas. This book understands radical culture as a complex and unstable field of forces, ‘fragmented’ as Mark Philp has it, reacting to events in France, and indeed to global forces and events; seeking to influence change in Britain and aspiring to influence change in a wider world.19

For many of those involved, books were regarded as a principal agent of political change, sharing Louis Mercier’s belief that Thomas Paine’s Common Sense (1776) had not only roused the American colonists but also provided ‘a general shock to the political world, which has given birth to a great empire, and a new order of things’.20 This idea was reinforced by the general explosion of print in the final decades of the eighteenth century and the rapid development of an infrastructure that enabled the transmission of knowledge.21 Most historians of print identify a takeoff in the number of imprints from as early as the 1760s.22 Nevertheless the trade was far from industrialised, print runs were relatively small, and booksellers and printers – many of whom joined the radical societies – often provided a close-knit form of interaction with writers and readers of a sort noted many times in these pages. The idea of a political society as the hub for the creation, collection, and dissemination of political information in print was a defining feature of both the SCI and the LCS. Both societies also eagerly exploited formats that had been extending the reach of the press, especially newspapers and periodicals, acting upon a widespread belief that they had become integral to the political process. ‘But, gradually, they have assumed a more extensive office’, wrote the New Annual Register in 1782, ‘they have become the vehicles of political discussion in a far higher degree than they formerly were, and, in this respect, they have acquired a national importance.’23 Some members of the radical societies, as we have already seen, had already exploited these media in the 1780s and were to continue to exploit them in the 1790s. The LCS used newspapers to advertise its meetings and was very close to Sampson Perry’s newspaper the Argus, at least in 1792, and then the Courier and the Telegraph in 1794–5. In terms of periodicals, the LCS twice attempted to compete in the market for information with its own: the short-lived Politician that struggled into life at the end of 1794, and the marginally more successful Moral and Political Magazine (1796–7).

Various associational practices had become interwoven with such formats over the course of the eighteenth century. Periodicals frequently reported the activities of clubs and societies, which often formed themselves around subscriptions. Books clubs and reading societies circulated their rules and regulations, sometimes printed in periodicals, producing a high degree of uniformity across their activities.24 Many of the protocols of the SCI and the LCS were governed by these emergent general conditions for interacting with print. Except for the fact that many reading societies banned the discussion of politics and controversial religion in their rules, the first gathering of Thomas Hardy and his friends in the Bell in January 1792 looks like just such a group. Hardy’s decision in 1806 to donate his political pamphlets to the Mitcham Book Society seems to acknowledge the continuities. Songs and toasts were an important aspect of the structured conviviality of the associational world more generally. The vigour supplied by Robert Thomson’s songs and toasts seems to have saved LCS divisions threatening to fold in 1792. Although oral performance was central to the vivifying effects they had on dwindling divisions, bringing those who could not read into the associational world, circulation of songs and toasts around the society often depended on print. The medium also allowed Thomson and others to reproduce songs for LCS meetings that had previously been used in very different social milieux.

Print was often taken to be the precondition for discussion and debate. In his account of the enlightening effects of the printing press, Thelwall concurred with his lawyer John Gurney that ‘the invention of printing had introduced political discussion’.25 Although written correspondence between societies across the postal network was a key form of circulation, handled by Hardy in the important position of secretary until 1794, he understood the printing of the LCS’s first Address in 1792 as the moment when it became public. Both the SCI and the LCS self-consciously presented themselves as nodes via which radical opinion in the country could enter into dialogue, creating a space in which the popular will could come to know itself. More than once, as with the Tewkesbury Society, the LCS invited groups to adapt their forms and practices and even change their names to become corresponding societies after the image of the parent society. Resistance to such proposals sprang from an anxiety about forms of organisation that might slide into another version of the ‘virtual representation’ that its members associated with aristocratic despotism.26

At certain points the societies seem to operate under the spell of ‘print magic’, that is, a faith that print could liberate mankind simply by bringing ideas into printed circulation. In terms of a distinction made by William Warner, this could appear to be a dream of ‘communication’ over ‘transmission’, whereby differences of time and place are overcome in a republic of letters imagined as a transparent and unified domain of the circulation of ideas.27 Frequently, ‘print magic’ provided the societies with a sustaining myth, a confidence in a deep logic that bonded print to progress and positioned any political defeat as a merely local matter. Several autobiographies from the period attest to the transformative effects of the encounter with print in the 1790s, and situate individual narratives of improvement within a larger narrative of liberty. Nevertheless faith in print magic coexisted with a serious attention to the everyday labours of composition, production, and circulation. This attentiveness to transmission was reinforced by the legal architecture governing the circulation of knowledge and opinion. In the form of the various laws governing opinion, especially seditious libel and, ultimately as it turned out, the law of treason, these legal constraints, for all their inefficiency, had serious effects on the forms that radical print culture could take. Prosecutions soon forced the LCS and SCI to be bitterly aware, if they were not already, of the difficulties of transmission, the intricacies of mediation that needed detailed work on forms and modes, whether to avoid prosecution or, more positively, to find the most appropriate forms of representation for the popular will. Their members often exploited these formal possibilities brilliantly, not least in their development of the rich tradition of satire and pasquinade they had inherited from the earlier eighteenth century.

Part I of this book explores these conditions of mediation. Chapter 1 is concerned with the key concepts of print and publicity and their relation to complicating issues of space and gender. The spatial politics of London placed its own constraints on the LCS.28 The basic need to find venues where it could meet in the face of pressure from local authorities was one important factor. After the Royal Proclamation of May 1792 landlords were increasingly threatened with the loss of their licences (and their livelihoods) if they provided a home for the radical societies. The LCS fought to find a place for itself in the diversified social geography of eighteenth-century London. Beyond the practical exigencies of finding somewhere to meet, it was insisting on its place before the public, refusing to fulfil the account of its activities as inherently underground and conspiratorial. This response need not be understood only as a reaction to external pressures that invested in ‘respectability’. Thomas Hardy had some sharp things to say about conventional understandings of that word in his memoirs. There is no reason to think that the LCS did not understand itself to belong properly within the public sphere. It regularly demonstrated that it was open to inspection, not simply to defend itself from slurs that it was conspiratorial, but because it was committed to what Thomas Paine called ‘the open theatre of the world’.29 Among those public spaces was the theatre itself, where members protested from within the audience and leafleted in the foyers as well as writing plays.

As with much of the broader associational world of clubs and societies, women seem to have played little official part in the popular radical societies, despite Robert Thomson’s toast to ‘patriotic females’ in his Tribute to Liberty (1792).30 Nevertheless, this study aims to restore a sense of the female presence in popular radical culture, even if individual women are mainly glimpsed only in the interstices of LCS activity. Susan Thelwall attended debates with her husband and provided commentary to her family on the development of radical opinion in London. Eliza Frost publicly denied the government’s claims about her husband. Susannah Eaton ran her husband’s shop when he was in prison or in hiding. John Reeves complained of her ‘particular parade’ in selling libels for which her husband was in prison.31 In 1793 the LCS encouraged a ‘female Society of Patriots’, noted in Chapter 1, but no record of it ever meeting survives. ‘Female citizens’ did attend the general meetings of 1795 and anonymously addressed the publications of the societies. More generally, though, the LCS seems to have conformed to masculine definitions of citizenship and related practices, not least in the homosocial environment of singing and toasting at dinners. Predictably perhaps given these perspectives, the part played in Lydia Hardy’s death by events surrounding her husband’s arrest was presented as a deep intrusion into the domestic realm. Such intrusions provided a trope that had an important role to play in Thelwall’s writing, where the domestic sphere was often represented as the moral ground of his political character.

Chapter 2 takes a chronological route through 1792–5, tracing the way in which print formats and practices were elaborated and tested across different popular radical groups, especially in relation to the experience of the LCS and its members as they responded to events in Britain, France, and the wider world. At the heart of these responses a fundamental question of representation and mediation faced the popular societies. How were they to identify and give form to the ‘general will’ of the people? Rousseau had understood the ‘general will’ to be unrepresentable in theory. The British system of representation, he avowed, reverted to a form of slavery after each election: ‘Every law that is not confirmed by the people in person is null and void.’32 Despite their commitment to a programme of universal suffrage within the British system, the popular radical societies did not necessarily accept Parliament as the final horizon of their endeavours. The commitment to the circulation of political information in the societies accepted Rousseau’s assumption that ‘the general will is always right, but the judgment by which it is directed is not always sufficiently informed’.33 Thelwall for one was aware of a tension between the idea of ‘the scattered million’ and ‘the people’ the societies wished to represent.34 In 1795, the bookseller and LCS member Daniel Isaac Eaton brought out an edition of Rousseau’s Social Compact in his Political Classics series, but there is no reason to assume it provided the theoretical basis for the approach to these questions in the British popular societies.35 In terms of their everyday practice, the primary focus of this book, the radical societies encouraged an ongoing process of debate indebted to Paine’s idea that ‘discussion and the general will, arbitrates the question, and to this private opinion yields with a good grace, and order is preserved uninterrupted’.36 They self-consciously tasked themselves with what Seth Cotlar calls ‘the difficult process of constructing and sustaining an incessantly deliberative, politically efficacious and professedly inclusive mechanism for forming and discerning the general will’.37

Plenty of those in and around the popular radical movements were aware both of the theoretical arguments of Rousseau and of their influence on the French Revolution. Robert Merry and David Williams were directly involved in framing constitutions in the context of the French National Convention in 1792. Debates between the LCS and SCI early in 1794 about consulting more broadly with other radical societies reached deadlock over the word ‘convention’. To some, it simply implied a canvassing of opinion, but to others it represented a more significant step towards new forms of mediation for the will of the people. Pitt’s government chose to see their meetings in the worst possible light, identifying their goal as an anti-parliament. If the delegates from the two societies do not seem to have been very close to making any such claim themselves, wrangling within the LCS continued through 1794 and 1795 about its own constitution, especially the relation of the divisions to the executive. Some members – Thelwall included – argued that any form of constitution represented a usurpation of the rights of the divisions. Possibly informed by Godwin’s thinking in Thelwall’s case, there seems to have been a line of thought within the LCS that continuously aimed at the devolution of power. One might see in these various debates ‘the rudiments of a deliberative theory of publicity’ that Gilmartin discusses in relation to British radicalism after 1815. Ernesto Laclau’s idea of ‘populist reason’ and its permanent negotiation of heteronomy and autonomy might even be glimpsed in the LCS decision ultimately not to impose its forms and methods on the wider movement, but one should also bear in mind Gilmartin’s acknowledgement of an alternative tendency ‘to treat internal conflict as the consequence of error or government interference, something to be corrected rather than negotiated’. ‘Print magic’, understood, as it rarely was, in its purest form, often represented differences only as the ‘prelude to some final reconciliation or union, not a permanent condition to be addressed through ongoing procedures of public arbitration.’38 The idea of an endpoint when all debate and discussion would cease often featured as part of the rhetoric of popular radicalism in the 1790s, often shaped by a Christian sense of millenarian revelation as much as by anything like Rousseau’s notion of the ultimately transparent authority of the ‘general will’.39

In terms of the trajectory of my own thinking about this culture, it goes back over thirty years to reading E. P. Thompson’s The Making of the English Working Class as an undergraduate in the politically unpromising era of the early 1980s. Thompson understood the LCS primarily in terms of a class coming to consciousness. Since then literary scholars and historians have offered a diversity of accounts that have moved on from the Thompsonian model in their accounts of the radical societies. In the early 1980s, scholars sometimes suggested that radicalism failed because of the lack of coherence in its arguments for reform. Such a perspective tends towards a view of the domain of politics as a rational debate governed by the force of the better argument familiar from Habermas’s work, whether directly indebted to him or not. Such an approach can fail to register asymmetries of power and resources in economic and cultural senses and the limits to the Enlightenment faith in the reach of the republic of letters.40 This book attempts more fully to situate the complexities of popular radicalism in its everyday business, including at least some account of the domestic world on which it frequently drew and/or intruded. Recent scholars of radicalism have done much to explore the ways that ideology emerges in performance. Building on their work, I examine public lectures, toasting, tavern debates, and song, but also more mundane and less colourful associational practices, such as day-to-day editorial discussion about what to publish under the LCS’s name.

Scholars following Iain McCalman’s work have been particularly interested in the radical ‘underworld’ that emerged after 1795, once the popular radical societies were forced underground. This book is very much indebted to those enquiries, but is more concerned with the attempts of the societies to create a role within a broader public sphere prior to the narrowing of opportunity after the Two Acts passed into law. Of the studies brought out in the wake of McCalman, it perhaps most closely resembles the account of popular radicalism after 1815 given in Kevin Gilmartin’s Print Politics (1996). Particularly concerned with the nexus of publicity and print, Gilmartin’s approach focused ‘on the print resources developed in relation to the other aspects of radical culture (meetings, clubs, debating societies, petition campaigns, boycotts)’.41 This approach takes print as the key term in a cluster of issues relating to mediation, including association and performance. Consequently, the book is primarily concerned with the attempts of the popular societies to affiliate themselves to and in the process transform the enlightened public sphere, and with the various rebuffs they received.

Part of this process was the role of print personality as a form of mediation, that is, both attacks on personalities by the radical press – Pitt being the most obvious example, Charles Pigott being the most obvious exponent – but also the development of personae by writers and booksellers. Samuel Taylor Coleridge complained in 1809 that he lived in ‘this age of personality, this age of literary and political Gossiping’.42 Ironically he was writing about the veteran reformer Major John Cartwright, a member of the SCI, whose manner if not his politics he was praising precisely for their ‘freedom from personal themes’. The radical societies contained enough people familiar with the emergent modes of popular press to know the value of personality in print. Pigott, especially, had no compunction about mixing scandal with republican principles, but as an author he published anonymously for the most part and presented himself as a version of ‘the negation of persons in public discourse’ that Michael Warner has identified with eighteenth-century republicanism in America.43 The same holds true for Thomas Hardy in his role as secretary of the LCS. Hardy tended to subsume identity within his office, but for many others ‘the bold signature’, to use Gilmartin’s phrase, was deemed more useful.44 Many radical authors and booksellers created identities that functioned as nodal points in the flow of political information and could compete for attention in a world where personality was becoming a key aspect of publicity in the theatre and the newspapers.

Individual members of the society soon developed a use for personality in developing their claims to a place within the public sphere. Robert Merry imagined himself disseminating the spirit of liberty from pole to pole. Recitation of his odes added his glamour to political meetings. Radical writers and lecturers were prone to annexing a Whig-Protestant martyrology passing down from Hampden and Sydney, but whose numbers were added to from their own ranks, most conspicuously by Joseph Gerrald. Nor was print personality as it functioned in radical culture just a question of authorship. Daniel Isaac Eaton’s shop at the sign of ‘the Cock and Swine’ developed its personality from his acquittals for selling an allegory of a tyrannical game bird to the swinish multitude. Eaton at ‘the Cock and Swine’ and Lee at his ‘Tree of Liberty’ participated in a print marketplace where personality mattered as an interface between print and its readers. For all the universality of the public sphere constructed by radicals, it was still populated by showmanship of the sort that thrived across eighteenth-century print culture. If Pitt’s political legerdemain was parodied in the guise of Signor Pittachio after the pattern of an Italian street magician, this did not mean that radicals themselves were averse to the theatre of politics. Thelwall joined the travelling showmen in the newspaper columns around his advertisements by hawking his lectures north and south of the river for ‘positively the last time’. As lecturer and orator whose words were circulated in diverse textual forms from song sheets to the pages of the Tribune, Thelwall was the most prominent shape shifter among the print magicians of the radical movement by 1795.

Part II of this book attends to the question of personality by looking at Thelwall as one among four different radical careers. Two of my case studies, Robert Merry and Charles Pigott, were radicals from above, that is, they were men born into the elite who became detached from a sense of belonging to the dominant culture of eighteenth-century Britain.45 Citizen Lee and John Thelwall are more obviously representative of the LCS’s claim to represent ‘the people’, although they both harboured aspirations to participate in the republic of letters prior to their political awakenings, as we have already seen. They had also already positioned themselves in print as ‘friends to humanity’. It was a soubriquet not unusual with the societies, which often invoked a larger ‘moral’ vision beyond any narrow programme of parliamentary reform.46 Gerrald, Henry Redhead Yorke, Merry, and Pigott may be numbered among those who consistently invoked the universal cause of the human race against tyranny from the perspectives of what Amanda Goodrich calls ‘Enlightenment cosmopolitanism’.47 Although Linebaugh and Rediker have suggested that Hardy and his associates soon gave up this platform, there is plenty of evidence that it was never dropped from the purview of the radical societies, whatever the external pressures to justify the Britishness of their interest in reform.48

For many, this broader moral programme depended on a religious vision of the ‘human’, although no less invested in various forms of print mediation, whereas for others religion contradicted what they saw as an Enlightenment imperative towards rational debate. Both secular and religious imperatives could translate into a broader ‘moral’ concept of reform, if of very different kinds. Religious differences always complicated Thelwall’s relations with Coleridge, for instance, and within the LCS, freethinkers objected to ‘saints’ like John Bone doing missionary work within the divisions. Although these differences produced internal schism in 1795, the different parties felt no compunction about continuing to correspond and collaborate with each other when it came to printing and circulating cheap books. Religious and non-religious, various members believed that knowledge, not just political knowledge, was central to the improvement of the people. Although the English radical movement is often presented as narrowly concentrated on constitutional matters and an English tradition of liberty associated with the names of the Whig pantheon, the contribution of London Scots with a heritage of Presbyterian resistance seems to have played an important part, especially in 1792–3.

More broadly, the radical societies continued to have strong international contacts, not least because a steady stream of their members were forced to flee or migrate to France and the United States from as early as 1792. Events in Ireland and Scotland were constantly in the thoughts of the London societies. Many of those involved had arrived in the metropolis from those countries. London societies corresponded with French confrères, especially in 1792, their more elite members often drawing on experiences of Enlightenment cosmopolitanism that preceded the Revolution. Some of these members participated in the British Club at Paris over the winter of 1792–3 and agents like John Frost and Robert Merry travelled back and forth reporting on events. Merry eventually moved to France, was forced to return to Britain after Robespierre moved against foreign fellow residents in Paris, and tried to make for Switzerland in 1793 before finally migrating to the United States three years later. Members like Gerrald and Redhead Yorke heralded from an Atlantic world that seems to have contributed to their outsider perspectives, even though they claimed and were often granted gentry status. Others like Richard Lee and Merry fled to the United States after 1795, where they continued to contribute to a transatlantic radicalism, under the dyspeptic eye of William Cobbett. Despite the pressure to defend their Englishness and state their continuities with homegrown traditions, especially after war began in February 1793, the ‘moral geography’ of the radical societies was not limited to London or even what is now the United Kingdom.

Popular radical publicity aimed, in Redhead Yorke’s words, at a ‘complete revolution of sentiment’.49 The radical societies insisted that they were part of a general process of improvement from which political versions of ‘reform’ could not be omitted. To do so, they implied, would breach the promise of Enlightenment in so far as it had at least appeared to propose the existence of a republic of letters that knew no boundaries. The establishment of this ‘open theatre of the world’ was as much the object of the popular radical societies as parliamentary reform. Their faith in the power of print and publicity was bracing in this regard, but also brought with it vulnerabilities, not least a tendency to see an unfolding moral revolution as the necessary result of the story of print. Reading, writing, and discussion were their primary agents for imagined change. When the state closed down these channels of dissemination with the Two Acts, they struggled to imagine other ways of organising to attain the laurel of liberty, although many of them kept their faith alive, even in exile on distant shores. My own larger hopes for my account of their struggles here is that it might fit with Geoff Eley’s ambition for scholarship to continue to reveal ‘how the changeability of the world might be thought or imagined’.50