1. Introduction

Gapping, unlike most elliptical constructions (such as pseudogapping, verb phrase ellipsis, sluicing, etc.), is usually assumed to be ruled out in embedded contexts (Hankamer Reference Hankamer1979; Sag Reference Sag1976; Johnson Reference Johnson2009, Reference Johnson2014, Reference Johnson, van Craenenbroeck and Temmerman2018, among others). See, in this respect, the contrast in Example (1): the pseudogapped clause others had shrimp (containing two remnants surrounding the auxiliary) allows embedding under she claims that in Example (1a)Footnote 2, whereas the gapped clause others shrimp (only containing two remnants, in the absence of the main verb) in Example (1b) is disallowed across the embedded clause boundary. The same constraint is typically assumed to apply to stripping constructions, cf. Johnson (Reference Johnson, van Craenenbroeck and Temmerman2018): in Example (1c), the remnant Jones too cannot be embedded, as is the case for gapped clauses.

Hankamer (Reference Hankamer1979: 20) formalises this constraint on gapping as the ‘Downward Bounding’ constraint, according to which, gapping “does not go down into subordinate clauses”, operating “strictly in structures directly conjoined with each other”. The Downward Bounding Constraint is further discussed in detail by Johnson (1996/Reference Johnson2004, Reference Johnson2009, Reference Johnson2014, Reference Johnson, van Craenenbroeck and Temmerman2018), who dubs it the ‘No Embedding Constraint’.Footnote 3 Its general formulation (applying to gapping as well as stripping) is given in Example (2). This constraint accounts for the ungrammaticality of Examples (1b) and (1c) above since the embedding verb is not included in the ellipsis.

The ‘No Embedding Constraint’ is considered by Johnson as strong evidence for a ‘low’/subclausal coordination analysis of gapping (also called ’Small Conjunct Analysis’; see Section 2 for other arguments). Under this approach, gapping involves a coordination of small verb phrases (vPs), under a single Tense head shared across conjuncts, and not a coordination of clauses. Moreover, it is assumed that a Tense Phrase (TP) from a matrix clause may not dominate a vP from an embedded one; therefore, the low coordination account of gapping automatically rules out violations of the ‘No Embedding Constraint.’

However, the ban on embedded gapping does not seem to be a strong constraint, as shown by the empirical evidence from other languages, such as Persian (Farudi Reference Farudi2013, Bîlbîie & Faghiri Reference Bîlbîie and Faghiri2022), Spanish (Bîlbîie & de la Fuente Reference Bîlbîie and de la Fuente2019) and Romanian (Bîlbîie et al. Reference Bîlbîie, de la Fuente and Abeillé2021), where the gapped clause can appear in an embedded configuration, violating the ‘No Embedding Constraint’ (see Section 5.5).

Though gapping is found more often than not in coordination structures, it may also occur in some ‘oppositive’ structures, such as Example (3), and in some temporal or causal clauses, as illustrated in Example (4) with parallel remnants (and prosodic stress), which are usually considered subordinate.

In the theoretical literature, embedded gapping is controversial in English. According to Weir (Reference Weir2014), fragments in general can be embedded in English in some very restricted cases. First, they become acceptable if the complementizer is absent (Morgan Reference Morgan, Kachru, Lees, Malkiel, Pietrangeli and Saporta1973), cf. Examples (5) and (6); in Example (6), the fragment NP Bob can be embedded under I think only without that.

The same constraint is discussed for embedded stripping by Wurmbrand (Reference Wurmbrand2017), who proposes the generalisation in Example (7).

Both Weir (Reference Weir2014) and Wurmbrand (Reference Wurmbrand2017) suggest that similar restrictions apply to gapping, the omission of the complementizer showing ‘an ameliorating effect in gapping’ (Wurmbrand Reference Wurmbrand2017: 361), as observed in Examples (8) and (9): in both sets of examples, without that, embedded gapping improves significantly. Park (Reference Park2019) provides similar attested embedded occurrences, found on the Internet, as illustrated in Example (10).

However, these observations stand in sharp contrast with Hankamer (Reference Hankamer1979), Sag (Reference Sag1976) and Johnson (1996/Reference Johnson2004), who claim embedded gapping to be ungrammatical, with or without a complementizer, as shown in Example (11).

Moreover, for Johnson (1996/Reference Johnson2004), gapping and answer fragments differ: according to him, answer fragments allow embedding under I think in Example (12a), while gapping does not in Example (12b).

Second, beyond the restriction related to the absence of the complementizer, Weir (Reference Weir2014) observes that embedding predicates do not seem to behave the same: some verbs seem to embed more easily than others. According to Weir (Reference Weir2014), only ‘bridge’ verbs (e.g. non-factive predicates, such as believe, think, suppose, suspect, imagine) allow fragment embedding, as opposed to ‘non-bridge’ verbs (e.g. factives, such as know, remember, realize, find out, be surprised, as previously proposed by de Cuba & MacDonald Reference de Cuba, MacDonald, Amaro, Lord, de Prada Pérez and Aaron2013 for Spanish). This suggests that there is a correlation between fragment embedding and extraction: predicates which do not allow extraction from their complements do not allow fragment embedding either. However, his intuitions, given in Example (13), reflect gradient acceptability rather than binary categorical judgments. Being aware of the heterogeneous behaviour of factive verbs, he notes: “it is not clear that extraction of the object from a verb like find out […] is degraded at all; the literature reports varying judgments on such cases” (Weir Reference Weir2014: 235). He extends his observations to gapping, suggesting that the verbs which allow embedded fragments in English would allow embedded gapping as well, as illustrated in Example (14). Though not all ‘bridge’ verbs seem to be equally appropriate in Example (14a), he postulates a clear contrast between Examples (14a) and (14b, c).

The main goal of this paper is to gather experimental data to obtain a deeper insight into embedded gapping in English. It is important to note, however, that the kind of behavioural data that will be gathered is based on the notion of ‘acceptability’, which refers to whether a sentence sounds more or less acceptable in a particular context. Acceptability is, thus, a gradable notion (i.e. sentences can be fully acceptable or partially acceptable, all the way down to completely unacceptable). Acceptability is not the same as the theoretical notion of ‘grammaticality’, which refers to the hypothesis of a given sentence possibly being generated by the grammar of the language or not. Grammaticality is usually considered not to be gradable, but rather binary (i.e. sentences are either grammatical or ungrammatical). There is, however, a relation between acceptability and grammaticality, where ungrammatical sentences tend to be judged as unacceptable. Although this is not necessarily always the case: grammatical sentences can be judged as unacceptable (e.g. because they are hard to process) and, likewise, ungrammatical sentences can be judged as acceptable (e.g. because of ‘good enough processing’, cf. Ferreira et al. Reference Ferreira, Karl and Ferraro2002; Ferreira & Patson Reference Ferreira and Patson2007). In order to test the grammaticality of embedded gapping, the accounts presented above rely either on production (corpus) data or on introspective judgments, leading to significant variation in the judgments and even to contradictory data (compare Examples (8–9) with Examples (11–12)). We argue, therefore, that only an approach based on the acceptability judgments of naive participants can provide a more fine-grained insight into the phenomenon of embedded gapping in English (i.e. the ‘No Embedding Constraint’), in general, and into the factors that might render embedded gapping more or less acceptable (e.g. the semantic class of the embedding predicate and the presence/absence of the complementizer), in particular. More specifically, if the ‘No Embedding Constraint’ is indeed a purely grammatical constraint, one would expect a very low acceptability of gapping in all environments irrespective of these factors.

The present paper is structured as follows: In Section 2, we spell out our research questions and predictions, followed by Section 3, where we present a first experiment, testing factivity in relation to complementizer omission in embedded complement clauses in English, outside coordination and ellipsis. Subsequently, in Section 4, we present two experiments testing the ‘No Embedding Constraint’ in gapping, in order to observe the role of the complementizer across different semantic types of predicates. Finally, Section 5 provides a general discussion of our experimental results, and focuses, inter alia, on the consequences on the syntactic analysis of gapping in English.

2. The present study

Before spelling out our research questions, we briefly present the main syntactic accounts of gapping and the predictions they make with respect to embedded gapping.

2.1 Syntactic accounts of gapping

Depending on the size of the gapped material, two configurations have been proposed: Small Conjunct Gapping (henceforth, SCG), involving roughly VP-sized conjuncts (subclausal/‘low’ coordination), and Large Conjunct Gapping (henceforth, LCG), involving clause-sized conjuncts (clausal/‘high’ coordination). Each of them comes in various versions. However, listing all of them lies beyond the scope of this paper. Within SCG approaches, we discuss the movement-based analysis of gapping (involving either across-the-board movement of the shared verb out of each conjunct, cf. Johnson 1996/Reference Johnson2004, Reference Johnson2009, or sideward movement, cf. Winkler Reference Winkler2005), illustrated in Example (15a). Within LCG approaches, we discuss the classical deletion-based analysis (Ross Reference Ross, Bierwisch and Heidolph1970; Kuno Reference Kuno1976; Sag Reference Sag1976), involving deletion of a Tense Phrase (TP) or Complementizer Phrase (CP), as illustrated in Example (15b), and the competing construction-based analysis in terms of fragments (Culicover & Jackendoff Reference Culicover and Jackendoff2005; Abeillé et al. Reference Anne, Bîlbîie, Mouret, Boas and Gonzálvez-García2014; Bîlbîie Reference Bîlbîie2017), which appeals to a dedicated meaning-form rule mapping a headless structure to a clausal meaning, as shown in Example (15c).Footnote 4

The main argument for an SCG analysis of gapping is semantic: as observed by Siegel (Reference Siegel1984, Reference Siegel1987), McCawley (Reference McCawley, Guenter, Kaiser and Zoll1993) and Johnson (1996/Reference Johnson2004, Reference Johnson2009), gapping allows cross-conjunct binding and wide scope of some operators, such as modals, negation or quantifiers. Example (16a) illustrates this for modals and negation: the negated modal can’t in the first conjunct yields a wide scope above the coordination, incompatible with the interpretation in Example (16b).Footnote 5

But, as pointed out by Kubota & Levine (Reference Kubota and Levine2016) and Park (Reference Park2019), the SCG approach is challenged by cases involving topicalised elements in Example (17a) or fronted wh-words in Example (17b), which are assumed to be above the TP projection.

As mentioned in Section 1 supra, the main syntactic motivation for an SCG account of gapping is precisely the ‘No Embedding Constraint’, postulated by Johnson (1996/Reference Johnson2004, Reference Johnson2009, Reference Johnson2014, Reference Johnson, van Craenenbroeck and Temmerman2018). In such an approach, two vPs are shared by a unique Tense (T) node in a subclausal coordination, as in Example (15a). Cases where the gapped clause is embedded within the conjunct it belongs to, as in Example (1b) above, are problematic under this account, as the unique T head cannot be shared by two vPs if one of them is embedded under another T head. Therefore, SCG automatically rules out embedded gapping, with or without a complementizer.

As for the LCG approaches in terms of ellipsis, as in Example (15b), they usually appeal to remnant movement operations to the left periphery (topic/focus projections), followed by clausal ellipsis (deletion at the level of Phonological Form or ‘PF-deletion’). However, remnants may occur in what would be an island for extraction (see Culicover & Jackendoff Reference Culicover and Jackendoff2005).Footnote 6 An attested challenging example with the gapped material in a syntactic island, i.e. a relative clause, while cannot has wide scope, is the following:

If one maintains such an analysis for gapping, an approach involving leftward movement of remnants predicts embedding only under non-factive predicates (such as think) and only with that. As observed by Hooper & Thompson (Reference Hooper and Thompson1973), operations targeting the left periphery, e.g. topicalisation of the NP given in italics in Example (19), cannot occur with factive predicates (such as regret; compare Examples (19a) and (19b)). Moreover, activation of the left periphery of the clause for a topic or focus constituent seems to force the presence of a complementizer (Grimshaw Reference Grimshaw1997; Doherty Reference Doherty2000).

So, the LCG approach in terms of ellipsis in Example (15b) predicts that gapping can only be embedded in the presence of that, in conflict with the Embedded Stripping Generalisation, postulated by Wurmbrand (Reference Wurmbrand2017), which admits embedding only without a complementizer. So, though the deletion-based LCG account may allow embedded gapping, it does not fit the intuitive data about that-omission from the literature (e.g. Weir Reference Weir2014).

As for the construction-based version of LCG approaches, in terms of fragments, as in Example (15c), it assumes that there is no head verb in the gapped clause (Culicover & Jackendoff Reference Culicover and Jackendoff2005; Abeillé et al. Reference Anne, Bîlbîie, Mouret, Boas and Gonzálvez-García2014; Bîlbîie Reference Bîlbîie2017). It is inspired by Ginzburg & Sag (Reference Ginzburg and Sag2000)’s analysis of English fragments, which are assumed to be non-finite but verbal, thus allowing in principle for fragment embedding.Footnote 7 The various restrictions on embedding are dealt with by means of a Boolean feature independent clause (IC):Footnote 8 therefore, a [IC+] constraint on short answers ensures that declarative fragments (=fragment answers) cannot function as an embedded declarative clause. This blocks ellipsis in configurations other than independent clauses, as in Example (20). In contrast, interrogative fragments (=short questions) may be underspecified for the feature IC, allowing for the possibility of ellipsis in both matrix and embedded environments, as in Example (21).

Coming back to gapping constructions, the predictions for embedding are different according to the type of the fragment involved. For Culicover & Jackendoff (Reference Culicover and Jackendoff2005) and Abeillé et al. (Reference Anne, Bîlbîie, Mouret, Boas and Gonzálvez-García2014), fragments are non-finite and non-verbal: they are neither Verb Phrases (VP) nor Inflectional Phrases (IP). This automatically excludes embedded gapping. On the other hand, if one assumes that fragments are non-finite but verbal (à la Ginzburg & Sag Reference Ginzburg and Sag2000), this kind of fragment-based analysis predicts that embedding will be possible in gapping but only in the absence of the complementizer (as that requires a finite clause).Footnote 9

2.2 Research questions and hypotheses

We have contradictory claims in the literature (no embedding gapping for Johnson Reference Johnson, van Craenenbroeck and Temmerman2018, limited embedded gapping for Weir Reference Weir2014), and contradictory structures making different predictions: no embedding for the SCG analysis in Example (15a), embedding under non-factive verbs with complementizer for the LCG analysis with deletion in Example (15b) and embedding without complementizer for LCG analysis with fragments in Example (15c).

In light of the above, the present study addresses the following research questions: Is embedded gapping acceptable in English, contrary to the predictions of the ‘No Embedding Constraint’? What role does matrix verb factivity play (if any)? What role does complementizer omission play (if any)? More generally, is embedded gapping constrained by syntax (presence or absence of a complementizer), by semantics (class of embedding predicate) or by both?

Given the lack of consensus in the theoretical literature, we ran three acceptability judgment tasks (AJT), following formal methods for judgment collection (Gibson & Fedorenko Reference Gibson and Fedorenko2013).

Since factivity and that-omission may be related, we ran a first experiment testing the interaction between that-omission and factivity in embedded complement clauses in English without gapping. We follow Karttunen (Reference Karttunen1971, Reference Karttunen1973), Kiparsky & Kiparsky (Reference Kiparsky, Kiparsky, Steinberg and Jakobovits1971), Hooper & Thompson (Reference Hooper and Thompson1973) and Hooper (Reference Hooper and Kimball1975), who distinguish between non-factives and factives, on the one hand, and between semi-factives and true factives, on the other hand. Therefore, we make use of three classes of predicates:

-

- non-factives: epistemic and communication predicates (cf. class B in Hooper & Thompson Reference Hooper and Thompson1973, e.g. think), which have been traditionally analysed as expressions that do not presuppose the truth of their complement clause;

-

- semi-factives: cognitive predicates (cf. class E in Hooper & Thompson Reference Hooper and Thompson1973, e.g. discover), which concern knowledge of facts, and are ‘soft’/’weak’ presupposition triggers (Abusch Reference Abusch2002, Reference Abusch2010; Jayez et al. Reference Jayez, Mongelli, Reboul, van der Henst and Schwarz2015), i.e. they presuppose the truth of their complement clause, but presupposition can be easily suspended;

-

- true factives: emotive predicates (cf. class D in Hooper & Thompson Reference Hooper and Thompson1973, e.g. regret), which concern emotional attitudes towards facts, and are ‘hard’/’strong’ presupposition triggers (Abusch Reference Abusch2002, Reference Abusch2010; Jayez et al. Reference Jayez, Mongelli, Reboul, van der Henst and Schwarz2015), i.e. they presuppose the truth of their complement clause, and this presupposition cannot be suspended as easily.

Assuming this tripartition, and based on previous theoretical accounts, we expect that -omission to be more acceptable under non-factive verbs than under factive verbs, and within factives, that -omission should be more acceptable under semi-factive verbs than under true factive verbs.

We subsequently ran two experiments, comparing gapping and non-gapping, one with non-factive verbs, and one with factive predicates in order to test the predictions above but this time with respect to embedded gapping.

The three experiments were administered on Ibex Farm (Drummond Reference Drummond2013). For each, we recruited participants from the United States via an online market place for work (Mechanical Turk, Amazon, United States) in 2019. Each experiment lasted 10 to 15 minutes, and participants received $1.25.

3. Testing the interaction between factivity and complementizer: Experiment 1

Complementizer omission in embedded complement clauses in English has been extensively studied from different perspectives, and by taking into account various linguistic and non-linguistic (cognitive, social) factors (for an overview, see Jaeger Reference Jaeger2006, Reference Jaeger2010). In Experiment 1, we explore the semantic factor of factivity, which, to our knowledge, has never been investigated in relation to that -omission in English.Footnote 10

While the judgments seem to be clear for non-factives and true factives (i.e. non-factives easily allow that -omission, as in Example (22a), true factives disfavor complementizer omission, as in Example (22c)), there is no consensus with respect to semi-factives (Kiparsky & Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky, Kiparsky, Steinberg and Jakobovits1971; Hooper & Thompson Reference Hooper and Thompson1973, etc.).Footnote 11 As illustrated in Example (22b), complementizer drop under the semi-factive discovered is supposed to be ungrammatical, as is the case with other factive predicates in Example (22c). However, for de Cuba (Reference de Cuba2018: 11), some semi-factives, such as notice, know, discovered, seem to allow that-omission in Example (23). The same observation comes from Shim & Ihsane (Reference Shim and Ihsane2017), based on an informal survey from 10 native speakers of various varieties of English: that can be optional under semi-factive verbs (24).

3.1 Participants

A total of 51 English native speakers participated in Experiment 1 (20 female and 31 male; mean age: 43.4; range: 25–69).

3.2 Materials

We built 20 experimental items following a 2x2 factorial design with Complementizer (+that vs –that) and Factivity (Factive vs Non-factive) as independent variables. This yielded the four experimental conditions in Example (25). As a reminder, we predict that the condition where the complementizer is dropped after a factive predicate, i.e. [–that, +factive], will be significantly less acceptable than the other conditions.

All experimental items were complex sentences with 20 embedding predicates: 10 non-factives (epistemic and communication verbs, repeated in two different items: I think, I suppose, I suspect, I imagine, I believe, it seems, I figure, I expect, I guess, it appears), five true factives (emotion verbs, repeated in two different items: I’m surprised, I’m bothered, I love, I like, I regret) and five semi-factives (knowledge verbs, repeated in two different items: I notice, I know, I observe, I see, I realize).Footnote 12 The embedded verb was always transitive and past tense indicative, with a proper name or a definite NP subject.Footnote 13

In order to control for frequency effects, we also took into account the matrix verb’s frame frequency since both the verb’s frequency (Bolinger Reference Bolinger1972; Elsness Reference Elsness1984; Roland et al. Reference Roland, Dick and Elman2007) and its bias for a sentential complement (Jaeger Reference Jaeger2006, Reference Jaeger2010; Kothary Reference Kothary, Grosvald and Soares2008; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Ryskin, Futrell and Gibson2019; Richter & Chaves Reference Richter, Chaves, Denison, Mack, Xu and Armstrong2020) have been shown to play a role: that is more frequent after less frequent matrix verbs and after less S-biased verbs.Footnote 14 For our experiment, the prediction is that matrix verbs with a lower S-complement verb-frame frequency will be rated lower without that. Moreover, Jaeger (Reference Jaeger2010) showed that the probability of the embedded clause (based on verb’s subcategorisation frequency) seems to be involved in explaining that-omission in English:Footnote 15 the higher a verb’s bias for the complement clause frame, the higher rate for the complementizer drop.Footnote 16 Following Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Ryskin, Futrell and Gibson2022), we calculated the verb-frame frequency for all our verbs by multiplying the frequency of the matrix verb by the frequency of the verb in a that-clause, i.e. P(matrix verb, sentence complement) = P(matrix verb) * P(sentence complement | matrix verb), based on the number of occurrences in the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA), searching for V and V+that (Complementizer) frequencies.

Table 1 lists all the predicates used in Experiment 1, along with their corresponding S-complement verb-frame frequencies. It is to be noted that our matrix predicates have different verb-frame frequencies: the mean frequency of non-factive verbs (0.023) is higher than that of true factive ones (0.0034).

Table 1 Summary of predicates used in our experiments and verb-frame frequencies.

In addition to the 20 experimental items, 20 filler items from an unrelated experiment were included. They tested preposition (mis-)matching in comparative sentences (Poppels & Miller Reference Poppels and Miller2022). In order to make sure that participants were reading the sentences carefully, we also included 16 control items, which present ungrammatical constructions due to subject-verb agreement mismatches, as in Example (26). Half of the experimental and filler items were followed by a ‘yes/no’ comprehension question, which was introduced as a further control measure.

3.3 Procedure

Sentences were presented in a Latin Square within-subjects design, so that participants were exposed to experimental items in all four conditions but never to the same item in more than one condition. After reading the instructions and answering some background questions, participants judged the acceptability of a set of practice items. They were instructed to read the sentences carefully and to judge their acceptability by using a Likert scale, from 1 (completely unacceptable) to 7 (completely acceptable). The Ibex software did not allow participants to go back to change a previous judgment.

3.4 Analyses and results

Only participants who answered at least 75% of the comprehension questions correctly were considered for subsequent analyses. Accordingly, one participant was excluded, and the data from the remaining 50 participants were subsequently analysed.

The participants’ acceptability ratings (ranging from 1 to 7) were entered into a mixed-effect linear regression analysis using the lme4 package (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R (R Development Core Team 2008). We entered Factivity (Factive vs Non-factive), Complementizer (Complementizer vs No Complementizer) and their interaction as the predictors. The model was fitted with the maximum random effect structure which contained random intercepts for Subjects and Items and by-subject and by-item slopes for the Factivity*Complementizer interaction. We also entered the log-transformed verb-frame frequencies (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Ryskin, Futrell and Gibson2022) as an additional fixed predictor.

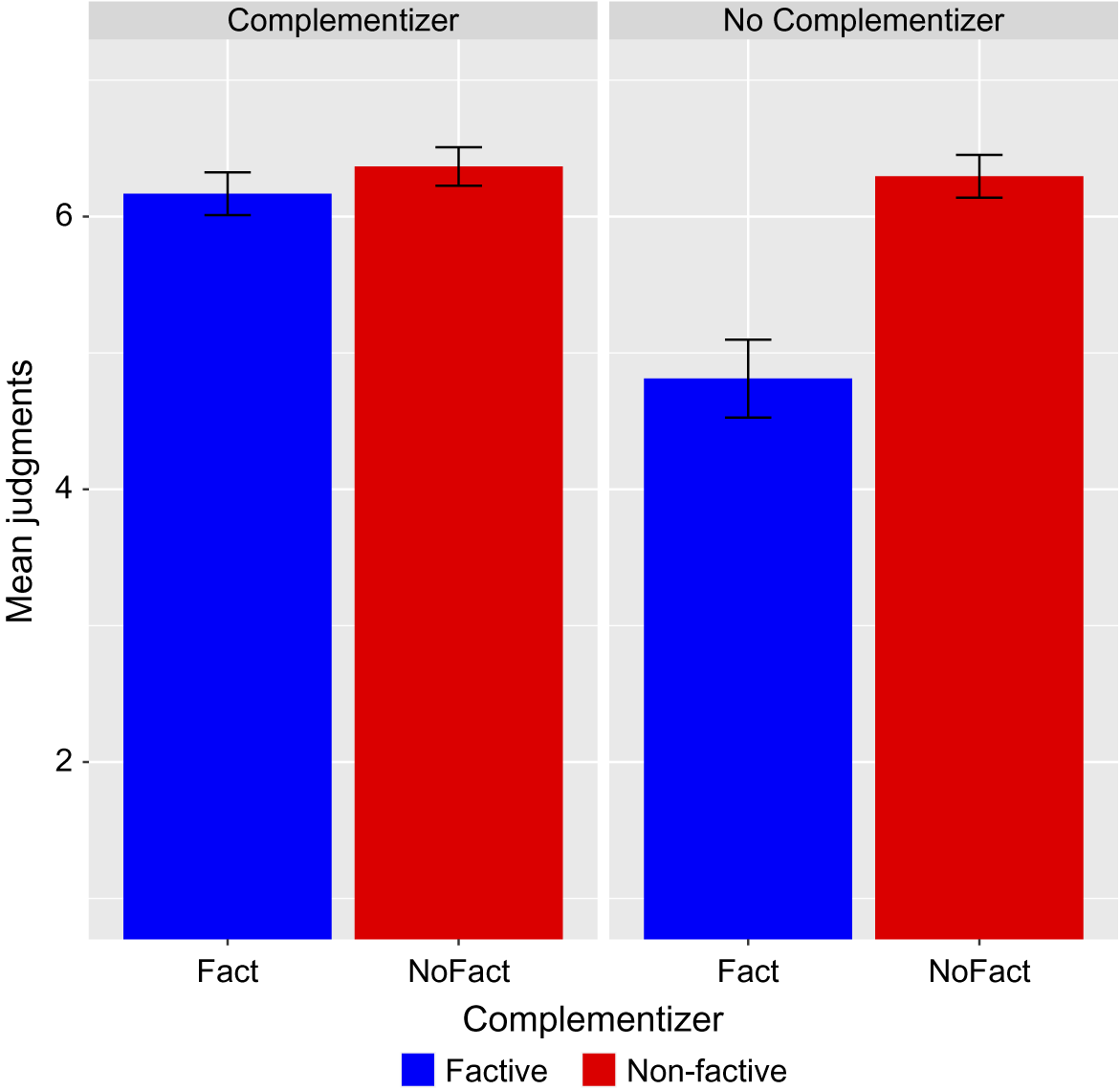

The analyses revealed, first of all, a significant main effect of Complementizer (p<.01), as participants rated the – that conditions significantly lower than the + that conditions. In addition to the main effect of Complementizer, the analyses revealed a significant main effect of Factivity (p<.01), as participants rated significantly lower the Factive conditions than the Non-factive conditions (5.49 vs 6.33) and a significant interaction between the factors Complementizer and Factivity (p<.01), as the difference in ratings between factive and non-factive predicates was bigger in the – that than in the + that conditions. The verb-frame frequency was also highly significant (p<.001) and was motivated by the fact that items containing predicates with a higher verb-frame frequency were rated as more acceptable than those containing predicates with a lower-frame frequency. This was especially the case in the – that conditions. The mean acceptability judgments for Experiment 1 are given in Table 2 and plotted in Figure 1. We observe that there are no differences in judgments with non-factive verbs with or without that, unlike with factive verbs. Moreover, bare clauses (i.e. without that) embedded under a factive verb (mean rating: 4.81) are more acceptable than the ungrammatical controls (mean rating: 3.64).

Table 2 Mean acceptability judgments for Experiment 1 (SD in parentheses).

Figure 1 (Colour online) Mean acceptability judgments for Experiment 1.

In order to further explore the attested sensitivity to the factive nature of the predicates, we ran additional linear regression analyses on the +factive conditions data only, distinguishing between true factive (emotive) verbs from semi-factive (cognitive) verbs. The new model was identical to the one previously used but now included Factive Type (True factive vs Semi-factive), Complementizer (Complementizer vs No Complementizer) and their interaction as the fixed predictors. These analyses revealed a significant main effect of Complementizer (p<.001), given that the participants rated the – that conditions significantly lower than those + that (4.79 vs 6.17). The factor Factive Type did not come as significant. However, the model revealed a significant interaction (p<.001) between Complementizer and Factive Type, as the difference in ratings between semi- and true factives is significantly bigger in the – that conditions, compared to the + that conditions. The factor verb-frame frequency did not come out as significant this time. Table 3 gives the mean acceptability judgments for the two kinds of factive predicates. Figure 2 illustrates these findings. We observe, therefore, that semi- and true factives do not give rise to exactly the same acceptability judgments, with respect to that-omission. Bare clauses embedded under a semi-factive verb are more acceptable than under a true factive verb.

Table 3 Mean acceptability judgments for factives in Experiment 1 (SD in parentheses).

Figure 2 (Colour online) Zoom into factive predicates in Experiment 1.

Given the fact that both non-factives and semi-factives allow the absence of the complementizer, one could say that there are only two categories: non-factives and semi-factives together versus true factives. Non-factives and semi-factives seem to share various properties: not only the possibility to embed a bare clause (in the absence of the complementizer) but also the possibility to have a parenthetical use (Hooper & Thompson Reference Hooper and Thompson1973), as in Example (27). In order to test this possibility, we performed an additional statistical analysis to measure the difference between non-factives and semi-factives only (irrespective of true factives), in order to see if there is indeed a tripartite distinction. The analyses revealed a significant main effect of Complementizer (p<.01), a significant main effect of Factivity (p<.001) and a marginally significant interaction between the factors Complementizer and Factivity (p<.1). The factor frequency was also highly significant (p<.001).

3.5 Discussion

The results of Experiment 1 show that that -omission is significantly less acceptable with factive predicates than with non-factive predicates, and significantly lower with true factive predicates than with semi-factive predicates. They confirm that factive verbs do not display a homogenous behaviour when it comes to the presence/absence of that, as evidenced by the gradience in acceptability judgments: non-factives > semi-factives > true factives.

Our experimental results clearly show that semi-factive and true factive verbs are two distinct classes, as initially observed by Karttunen (Reference Karttunen1971). They do not have the same behaviour with respect to that -omission, as well as with respect to other phenomena (e.g. island constraints, cf. Ambridge & Goldberg Reference Ambridge and Goldberg2008, a.o.).

Additionally, positing a semantic tripartition challenges some syntactic analyses which try to account for the distinction between non-factive and factive predicates in the syntax. Kiparsky & Kiparsky (Reference Kiparsky, Kiparsky, Steinberg and Jakobovits1971)’s analysis assumes a more complex structure for factive clausal complements than for non-factive clausal complements. More recent studies (Haegeman Reference Haegeman2006; de Cuba Reference de Cuba2007; de Cuba & Ürögdi Reference de Cuba and Ürögdi2010) propose the opposite view, namely, the structure of factive complements is simpler than that of non-factive complements. However, none of these proposals easily accounts for the ‘hybrid’ semantic class of semi-factives. We will come back to these syntactic issues in Section 5.3.

As shown by our results, there is a clear graded acceptability across the three types of predicates. Therefore, in what follows, we will build on this semantic tripartition to test the acceptability of embedded gapping in English.

4. Testing embedded gapping constructions: Experiments 2 and 3

Experiments 2 and 3 tested the role of the complementizer in embedded gapping, with the same embedding predicates as in Experiment 1: non-factive predicates were investigated in Experiment 2, while factive predicates were looked into in Experiment 3. Given the contradictory judgments in the literature (see Example (28)), and the different syntactic analyses proposed, we want to test: (i) which role that-omission plays, if any, and (ii) which role verb factivity plays (if any). Our hypothesis is that a similar generalisation to that proposed by Wurmbrand (Reference Wurmbrand2017: 345) for embedded stripping in English would apply to embedded gapping configurations, namely, the complementizer omission should show an ameliorating effect in embedded gapping.

Furthermore, because, as shown in Experiment 1, non-factive predicates allow that-omission more easily than factive predicates, the type of embedding predicate should have an effect on embedded gapping. Given that Experiments 2 and 3 were very similar, we present them together in the following sections.

4.1 Participants

Experiment 2 had 47 English native speakers who participated (33 female and 14 male; mean age: 46.9; range: 22–72) and Experiment 3 had 50 (24 female and 26 male; mean age: 40.9; range: 27–66).

4.2 Materials

We built 20 experimental items following a 2x2 factorial design with Gapping (Gapping vs No Gapping) and Complementizer (Complementizer vs No Complementizer) as independent variables. Using the same verbs as in Experiment 1 (Table 1), we had 10 non-factive verbs (each repeated twice) in Experiment 2, see Example (29), and 10 factive verbs, i.e. true factive (each repeated twice) and semi-factive predicates (each repeated twice) in Experiment 3, see Example (30).

In order to facilitate gapping, each experimental item was introduced by an initial adjunct, which sets the background in discourse (i.e. a circumstantial frame setter, that limits the applicability of the main predication to a certain restricted domain, cf. Chafe Reference Chafe and Li1976).Footnote 17 The experimental items were all coordinated sentences with and. Each of the two conjuncts introduced a character by means of a proper name or a definite NP. The main verb was always a transitive verb in the past tense indicative, as in Experiment 1.

Beside the 20 experimental items, we used 28 filler items from unrelated experiments, which were different from the ones used in Experiment 1. Two of the filler item conditions tested ungrammatical subject- and object-extracted relative clauses in it-cleft constructions, as in Example (31), and were used as control conditions. As in Experiment 1, half of the items were followed by a ‘yes/no’ comprehension question.

4.3 Procedure

Experiments 2 and 3 follow the same procedure described for Experiment 1.

4.4 Analyses and results

Only participants who answered at least 75% of the comprehension questions correctly were considered for subsequent analyses. Accordingly, one participant was excluded from Experiment 2 and four from Experiment 3. The data from the remaining 46 participants, in each experiment, were subsequently analysed.

As in Experiment 1, the participants’ acceptability judgments (ranging from 1 to 7) were entered into a mixed-effect linear regression analysis using the lme4 package (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015) in R (R Development Core Team 2008). We entered Gapping (Gapping vs No Gapping), Complementizer (Complementizer vs No Complementizer) and their interaction as fixed predictors. The model was fitted with the maximum random effect structure which contained random intercepts for Subjects and Items as well as by-subject and by-items slopes for the Gapping*Complementizer interaction. We also entered verb-frame frequency as an additional fixed predictor.

The mean acceptability judgments for Experiment 2 are given in Table 4 and plotted in Figure 3.

Table 4 Mean acceptability judgments for Experiment 2 (SD in parentheses).

Figure 3 (Colour online) Mean acceptability judgments for Experiment 2 (non-factive verbs).

The analyses of Experiment 2 revealed a significant main effect of Gapping (p<.001), as the No Gapping conditions were rated significantly higher than the Gapping conditions (6.35 vs 4.95), and a significant main effect of Complementizer (p<.001), as the conditions without that were rated significantly higher than the conditions where it was present (5.84 vs 5.46). Moreover, the interaction between Gapping and Complementizer was also significant (p<.01), as the difference in ratings regarding the presence/absence of the complementizer was stronger in the Gapping conditions. In the No Gapping conditions, the difference in ratings between + that and – that conditions was not significant, suggesting that there is no effect of the complementizer when there is no gapping (despite a higher frequency of that-omission in corpora, see Roland et al. Reference Roland, Dick and Elman2007). To conclude, that-omission has an ameliorating effect on embedded gapping; interestingly, embedded gapping under a complementizer is more acceptable than ungrammatical controls (mean rating: 2.86). To conclude, the factor verb-frame frequency was also significant (p<.05).

The mean acceptability judgments for Experiment 3 are given in Table 5 and plotted in Figure 4. The analyses of Experiment 3 revealed a significant main effect of Gapping (p<.001), motivated by the fact that the No Gapping conditions were rated significantly higher than Gapping conditions (4.88 vs 2.74), and a significant main effect of Complementizer (p<.01), as the + that conditions were rated higher than the –that conditions (4.01 vs 3.61). Moreover, we found a significant interaction between Gapping and Complementizer (p<.001), given that, in the No Gapping conditions, participants rated the +that condition significantly higher than the – that condition. Interestingly, embedded gapping (with or without that) is less acceptable than ungrammatical controls (mean rating: 3.24). The effect of the verb-frame frequency was marginally significant (p<.1).

Table 5 Mean acceptability judgments for Experiment 3 (SD in parentheses).

Figure 4 (Colour online) Mean acceptability judgments for Experiment 3 (factive verbs).

We conducted some additional analyses by distinguishing between semi-factive and true factive verbs. The new linear-mixed model included Gapping, Complementizer, Factive Type, and their interaction as fixed predictors, and random intercepts for Subjects and Items. In addition to this, verb-frame frequency was also included as a fixed predictor. The mean acceptability judgments from these analyses are given in Table 6 and illustrated in Figure 5.

Table 6 Mean acceptability judgments as a function of the type of factive verb for Experiment 3.

Figure 5 (Colour online) Zoom into the different kinds of factive predicates in Experiment 3.

These additional analyses revealed a significant main effect of Gapping (p<.001), as the Gapping conditions were rated significantly lower than the No Gapping conditions (2.75 vs 4.89). The statistical analyses also showed a significant main effect of Complementizer (p<.001), given that the + that conditions were rated significantly better than those – that (3.99 vs 3.64), and a significant main effect of Factive Type (p<.05), motivated by the fact that semi-factive predicates were rated significantly higher than true factive predicates (4.16 vs 3.48). In addition to these main effects, the model yielded significant Gapping*Complementizer (p<.001) and Complementizer*Factivity (p<.001) interactions. This was driven, on the one hand, by the fact that the – that conditions were rated significantly lower than the + that conditions when there was no gapping, with respect to the conditions with gapping; and, on the other hand, by the fact that items with true factive predicates were rated significantly lower than with semi-factive predicates, especially in the – that conditions. The effect of verb-frame frequency and the Gapping*Factive Type and the Gapping*Complementizer *Factive Type interactions were not significant. Crucially, all these results suggest that that-omission has an ameliorating effect on embedded gapping under semi-factive verbs with respect to true factive verbs and confirm the results from Experiment 1: bare clauses embedded under a semi-factive verb are more acceptable than under a true factive verb.

4.5 Discussion

First, we found an ellipsis penalty, since participants rated the No Gapping conditions significantly higher than the Gapping conditions, in line with what has been previously reported in the literature for English: Carlson (Reference Carlson2001) shows, based on two experimental studies (a written questionnaire and an auditory comprehension study), that in English, there is a preference for non-gapping over gapping structures.Footnote 18

Second, the combined results of Experiments 2 and 3 show that that -omission has an ameliorating effect on embedded gapping. Crucially, however, this ameliorating effect for gapping was, once again, modulated by the semantics of the embedding predicates. Our hypothesis was that embedding under non-factive verbs should be more acceptable than under factive ones, and, within factive predicates, embedding under semi-factive verbs should be more acceptable than under true factive ones. These hypotheses were all borne out by the results of Experiment 2 and 3. That-omission clearly shows an ameliorating effect with non-factive predicates compared to factive predicates, but this ameliorating effect arises again when we compare semi-factive to true factive predicates.

Moreover, in order to assess the semantic tripartition, we ran an additional statistical analysis to measure the difference between non-factives (Experiment 2) and semi-factives (Experiment 3) only (irrespective of true factives), as we did in Experiment 1. The analyses revealed a main effect of Gapping (p<.001), of Complementizer (p<.001) and of Factivity (p<.001), as well as a significant interaction between the factors Gapping and Complementizer (p<.001), and Gapping and Factivity (p<.001). This shows that non-factives and semi-factives behave indeed as two distinct classes.

To summarise, our experimental results show that the ‘No Embedding Constraint’ in English is affected by the presence/absence of that, as well as by the semantic class of the embedding predicate. We observed that factivity plays a role in embedded gapping (as it does with that-omission in general); the same semantic tripartition revealed by our Experiment 1 is at work in embedded gapping (cf. Experiments 2 and 3). An approach based on gradient acceptability (and not on categorical grammaticality) seems to be a better fit to capture these effects. Specifically, if the ‘No embedding Constraint’ was a purely grammatical constraint, we would have expected to see very low acceptability ratings of gapping constructions across the board. The combined results of Experiments 1–3 go against this assumption.

5. General discussion

We explain why our results are problematic for the ‘No Embedding Constraint’ and which consequences this has for the syntactic analysis of gapping. We then sketch a construction-based fragment analysis, before turning to some cross-linguistic considerations.

5.1 Revising the ‘No Embedding Constraint’

We found that embedded gapping is acceptable in English (contrary to Johnson), but its acceptability is affected by a syntactic and a semantic factor: it suffers from a complementizer penalty (Experiment 2) and from a factive verb penalty (Experiment 3). Embedded gapping is more acceptable under some semantic predicates provided the embedded clause has no complementizer. Gapping is preferably embedded under non-factive (and semi-factive) predicates but not under true factive predicates.

As shown by Experiment 1, these two factors are not independent, since factive verbs do not allow that-omission as easily as non-factive ones (independently of ellipsis); in particular, we observe a general penalty for that-omission under true factive predicates. We thus observe a preference clash: gapping prefers a that-less clause, whereas true factive predicates prefer the presence of the complementizer. This preference clash explains the unacceptability of embedded gapping under true factive predicates in English.

5.2 True embedding or parenthetical syntax?

It has been suggested that the availability of embedded gapping in English is due to the parenthetical use of the embedding predicate (Boone Reference Boone2014)Footnote 19, cf. Temmerman (Reference Temmerman2013) for a similar account of embedded fragments. It may account for the complementizer penalty found in Experiments 2 and 3, since that is not compatible with a parenthetical use, as in Example (32).

Under a parenthetical analysis, the embedded gapped clause is in fact a matrix fragment (as in regular gapping), so it is not truly embedded.Footnote 20 In this way, the ‘No Embedding Constraint’ would still apply in gapping constructions.

As appealing as this may be, there are some issues with such proposals. First, in our materials (which are written questionnaires), the embedding predicate is not isolated by commas from the rest of the utterance, so there is no overt indication of a parenthetical reading.

Second, according to Temmerman (Reference Temmerman2013), both ordinary parentheticals and cases of fragment embedding are restricted to a first-person subject, to a positive verbal form (no negation), to a verb without adverbial modification, etc. In our materials, most matrix predicates were with first-person subject, present tense, without negation, so they could be compatible with a parenthetical use (cf. Urmson Reference Urmson1952). But we also had two cases with it, as in Example (33a, b). In addition, it seems that the verb appears is less felicitous as a parenthetical (compare Examples (33c) and (33d)).

More generally, Weir (Reference Weir2014) adds further evidence in favour of a true syntactic embedding of fragments: the subject may be other than the speaker, as in Example (34); a fragment containing a negative polarity item (NPI) can be licensed, unlike with a parenthetical, as in Example (35); the subject can be negative, unlike in parenthetical contexts, as in Example (36).

Coming back to embedded gapping, a parenthetical analysis makes the wrong predictions with respect to the behaviour of semi-factives, which do not allow embedding as easily as non-factives (Experiment 3). In general, parenthetical insertion is typical of non-factives (see Example (37a)) and semi-factives (see Example (37b)), but it is less felicitous with true factives (see Example (37c)). As observed by Hooper & Thompson (Reference Hooper and Thompson1973) in Example (38), the complement of a semi-factive (but not true factive) verb can be preposed, so it can be raised to the position of a main assertion (as is the case with non-factives). However, our experimental results show that non-factives and semi-factives do not have the same behaviour and constitute two distinct classes, despite their potential parenthetical use.

Moreover, reducing embedding cases of gapping to parenthetical constructions does not account for more complex cases of embedded gapping, such as the naturalistic data in Examples (39)−(40), pointed out by Wellstood (Reference Wellstood2015) and discussed in Park (Reference Park2019), where both the gapped and its source are embedded; in these examples, the gapped clause appears as the complement of the embedding predicate, and we cannot analyse the embedding clause (marked in bold in these examples) as a parenthetical.

In light of the above, we conclude that there is no evidence in favour of a parenthetical analysis of the embedding predicates.

5.3 Consequences for the syntactic analysis of gapping

What are the consequences for the different syntactic analyses mentioned in Section 2? The SCG approach rules out embedded gapping, as a TP from the matrix clause cannot dominate a vP from an embedded clause; in other words, embedding the gapped clause necessarily implies a TP-coordination. Thus, the SCG analysis is unable to account for the embedding data we observed in Experiment 2: it cannot explain why embedded gapping is possible under non-factive verbs. Therefore, an LCG analysis of gapping seems to be a better fit to account for the embedding facts.

However, the LCG approach with leftward remnant movement and verb deletion predicts that embedded gapping be available only under non-factive predicates and only with an overt complementizer, since it is a topicalised structure. Crucially, our experimental results show that embedded gapping is ameliorated only without that (as postulated by Wurmbrand Reference Wurmbrand2017 for embedded stripping in English). Moreover, although non-factive predicates are those which get the highest rates, we observe that, within factives, semi-factives get significantly higher rates than true factive predicates. This cannot easily be handled by the deletion-based LCG account, which only accounts for the difference between non-factive and factive verbs (see the classical dichotomy between ‘bridge’ vs ‘non-bridge’ verbs) and does not predict gradience across the three semantic classes of matrix predicates (non-factives vs semi-factives vs true factives).

5.4 Towards a construction-based fragment analysis

Since we do not see how an SCG nor an LCG approach with leftward movement could account for our data,Footnote 21 we now turn to a construction-based version of an LCG approach. In a constructionist approach, gapping, like stripping, uses a dedicated rule mapping a headless structure (i.e. a fragment) to a clausal meaning. In this approach, each elliptical construction may have its specific constraints (Ginzburg & Sag Reference Ginzburg and Sag2000; Goldberg & Perek Reference Goldberg, Perek, van Craenenbroeck and Temmerman2018).Footnote 22

As an illustration, we present the main ingredients of a syntactic analysis couched within Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG)Footnote 23 (cf. Abeillé et al. Reference Anne, Bîlbîie, Mouret, Boas and Gonzálvez-García2014; Bîlbîie Reference Bîlbîie2017; Park et al. Reference Park, Koenig and Chaves2019), a constraint-based and surface-oriented framework. In such a fragment-based analysis, the gapped clause receives a clausal interpretation (with semantic reconstruction of the missing material) without having the internal structure of an ordinary clause, as initially proposed by Ginzburg & Sag (Reference Ginzburg and Sag2000) to account for short answers and short questions in English.

This fragment-based analysis of gapping has two crucial ingredients to account for the experimental results from Experiments 2 and 3: it assumes that the headless fragment is non-finite, and that the gapped clause must address the same Question Under Discussion (QUD) as the antecedent clause.

This analysis assumes that the gapped clause is non-finite, thus allowing regular gapping, and prohibiting embedding under a complementizer (assuming that requires a finite clause in English). Assuming that the gapped clause is a non-finite fragment directly accounts for data, such as Example (41), where gapping occurs in a coordination of embedded clauses: in these contexts, gapping is allowed only in the absence of that (Hartmann Reference Hartmann2000; Repp Reference Repp2009; etc.).

Some further arguments for this analysis are that the gapped clause is also appropriate with non-sentential negation and not in Example (42a) and the non-clausal conjunction as well as in Example (42b). These constructions are both acceptable with non-finite VPs, as in Example (42c). These kinds of data are problematic under a deletion-based analysis of an LCG account, as they show that gapped clauses may have different syntactic properties compared to those of their full counterparts.

In addition, the fragment-based analysis easily accounts for the attested Example (43a) that involves the accusative pronoun me, whereas the full counterpart in Example (43b) involves the nominative case. In the gapped version with accusative case, there is no finite verbal head to assign the nominative case, like in non-finite clauses as in Example (43c).Footnote 24

At the syntactic level, the fragmentary gapped clause only contains remnants (cf. Example (15c) above); each remnant must be paired with some ‘major’ correlate in the source clause (cf. Hankamer 1971’s Major Constituent Condition) and match its correlate in its HEAD value. The correlates of the remnants are identified via a contextual feature SAL(ient)-UTT(erance) (cf. Ginzburg & Sag Reference Ginzburg and Sag2000). Therefore, each remnant must match a possible subcategorisation of the verbal predicate in the source.

At the semantic level, each remnant must be in a contrastive relation with a correlate in the source; therefore, remnants are contrastive topics and contrastive foci (cf. Rooth Reference Rooth1985, Reference Rooth1992; Winkler Reference Winkler2005), i.e. they evoke alternatives. The content of the gapped clause is built from the meaning of the source, the remnants and their correlates.Footnote 26

Crucially, our fragment-based analysis includes a discourse component, which makes use of the contextual feature QUD (cf. Roberts Reference Roberts2012; Ginzburg & Sag Reference Ginzburg and Sag2000; Reich Reference Reich, Schwabe and Winkler2007; Ginzburg & Miller Reference Ginzburg, Miller, van Craenenbroeck and Temmerman2018; Kim & Nykiel Reference Nykiel, Kim, Müller, Abeillé, Borsley and Koenig2021). In a QUD-based approach, each utterance is supposed to contribute to the QUD, and can be analysed as an answer to an overt or implicit QUD (Roberts Reference Roberts2012). The most salient question in the discourse is the Maximal Question Under Discussion (MAX-QUD, cf. Ginzburg & Sag Reference Ginzburg and Sag2000). In gapping constructions, the most salient QUD generally corresponds to a multiple wh -question, cf. Steedman (Reference Steedman1990: 248): “Fred ate bread, and Harry, bananas, is only really felicitous in contexts which support (or can accommodate) the presupposition that the topic under discussion is Who ate what.” Most importantly, the discourse constraint on gapping is that both the gapped and the source clause must answer the same QUD (Reich Reference Reich, Schwabe and Winkler2007; Park Reference Park2019).

The discourse constraint that requires the gapped clause to address the QUD triggered by its source allows the gapped clause to be embedded, provided the embedding clause does not introduce a new QUD that is different from the one associated with the source clause (Park Reference Park2019). This directly predicts a penalty for embedded gapping under factives. As traditionally assumed (Karttunen Reference Karttunen1971, Reference Karttunen1973; Kiparsky & Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky, Kiparsky, Steinberg and Jakobovits1971), non-factive predicates do not presuppose the truth of their complement clause; in these cases, the embedded clause contains the foregrounded information, being the main assertion of the utterance (Hooper & Thompson Reference Hooper and Thompson1973). In other words, under a non-factive predicate, the embedded gapped clause contributes the main point of the utterance (i.e. ‘at-issue’ content, in the sense of Potts Reference Potts2005). Therefore, the QUD-based constraint is observed in embedded gapping under a non-factive verb, such as suspect in Example (44a): both the gapped and the source clause answer the same QUD (namely, Who ordered what?). On the other hand, factive predicates presuppose the truth of their complement, and in these cases, the embedding clause contributes the main point of the utterance, ‘at-issue’ content, whereas the embedded complement contains backgrounded information, ‘non-at-issue’ content (see Ambridge & Goldberg Reference Ambridge and Goldberg2008 for experimental evidence). Crucially, this kind of environment violates the QUD-based constraint stipulated above: in contexts such as Example (44b), the embedding clause I regret involves a new QUD (i.e. What effect did it have on the speaker?), different from the QUD of the source clause (i.e. Who ordered what?).

However, factive predicates do not behave exactly the same. One has to distinguish between semi-factive (cognitive) predicates and true factive (emotive) predicates (Karttunen Reference Karttunen1971; Hooper Reference Hooper and Kimball1975): with semi-factives, presupposition can be easily suspended, whereas it cannot be suspended as easily with true factives. We expect then a ‘hybrid’ behaviour of semi-factives: they may come closer to non-factives with respect to embedded gapping in cases where presupposition is suspended.Footnote 27 If embedding under a true factive predicate involves a new QUD in gapping constructions, this is not necessarily the case with semi-factives. This would explain why semi-factives are better at embedding predicates than true factives.

Consequently, our fragment-based analysis can easily handle the gradience we have observed through the three semantic classes of predicates (non-factives vs semi-factives vs true factives).

As we do not postulate any other specific syntactic constraint on embedding, we expect embedded gapping to be possible not only in the configurations we have analysed through this paper (when only the gapped clause is embedded) but also in more complex environments, such as Examples (39–40) above, where both the gapped and its source are each embedded.

Moreover, the QUD-based constraint predicts that gapping could occur in syntactic contexts other than coordination, provided the subordinating conjunctions introducing the gapped clause do not trigger the construction of a new QUD. Thus, we could explain the contrast we observe in Example (45) between the subordinating conjunctions while and because. As explained by Park (Reference Park2019), a because-clause introduces a new QUD (a why-question), so we expect Example (45) to be inappropriate with because, whereas a while-clause still answers the same QUD addressed by the main clause, so we expect Example (45) to be acceptable with while. Therefore, we observe that the purely syntactic configuration (coordination vs subordination) in which a gapping construction occurs is less important than its discourse functioning.

We note that this QUD constraint on gapping can subsume another discourse constraint discussed in the literature, namely, the availability of gapping only with symmetric discourse relations (Levin & Prince Reference Levin and Prince1986; Kehler Reference Kehler2002; Culicover & Jackendoff Reference Culicover and Jackendoff2005), i.e. resemblance relations (e.g. parallelism or contrast) and unacceptability of gapping with asymmetric discourse relations, e.g. cause-effect relations. We can say that all symmetric discourse relations involve a QUD-identity between the elements involved in this kind of relations, whereas asymmetric discourse relations do not necessarily maintain the same QUD.

The fact that gapping involves a semantic and discourse parallelism is also observed in Example (46), where we have one of some naturally occurring examples of embedded gapping, collected by Park (Reference Park2019) from Google. In this case, we have some symmetric/reciprocal relation between the remnants and the correlates, cf. the inverted order of pronouns in the contrastive pairs.

When the semantic and discourse parallelism is accommodated, gapping becomes available even in syntactic environments assumed to disallow gapping, as shown by the occurrences in Example (4) above, from Park (Reference Park2016), repeated for convenience in Example (47). Therefore, subordinating structures accommodating some kind of semantic and discourse parallelism may allow gapping.

Based on all these facts, we have to admit that gapping seems to be more constrained by semantic and discourse parallelism than by syntactic parallelism (Culicover & Jackendoff Reference Culicover and Jackendoff2005; Abeillé et al. Reference Anne, Bîlbîie, Mouret, Boas and Gonzálvez-García2014; Bîlbîie Reference Bîlbîie2017; Park Reference Park2019).

To conclude, embedded gapping in English is constrained both syntactically and semantically. The syntactic constraint requires the complementizer to be absent. This syntactic constraint is automatically accounted for in a fragment-based analysis, where the fragment is a non-finite phrase. In addition, there is a discourse constraint at work that allows embedded gapping only under some semantic types of predicates. We thus posit a specific QUD constraint, requiring the gapped clause and its source to address the same QUD.

5.5 A cross-linguistic perspective on embedded gapping

Based on our experimental evidence, we concluded that embedded gapping is possible in English, and is affected by both the semantic class of the embedding predicate and the presence/absence of that. In all our experiments, there is a significant interaction between the effect of the complementizer and the effect of the semantic class of embedding predicate.

From a cross-linguistic perspective, the semantic factor seems to hold across languages. If the true factive predicate penalty comes from the fact that the gapped clause must address the same QUD as the antecedent clause, we expect it to be universal. Recent experimental work (also based on several acceptability judgments tasks) by Bîlbîie & de la Fuente (Reference Bîlbîie and de la Fuente2019) for Spanish, Bîlbîie et al. (Reference Bîlbîie, de la Fuente and Abeillé2021) for Romanian and Bîlbîie & Faghiri (Reference Bîlbîie and Faghiri2022) for Persian show that embedded gapping is possible in these languages, and that non-factive verbs embed more easily than factive ones; and among factive verbs, semi-factive (e.g. cognitive) predicates embed more easily than true factive (e.g. emotive) ones. In Spanish, as shown in Bîlbîie & de la Fuente (Reference Bîlbîie and de la Fuente2019), embedded gapping is as acceptable as embedded non-gapping under non-factive verbs, such as creo ‘I think’ in Example (48).

Instead of stipulating a universal syntactic ‘No Embedding Constraint’ on gapping, we rather propose a generalisation, such as the following: there is a cross-linguistic semantic constraint related to the tripartition non-factives versus semi-factives versus true factives.

On the other hand, the presence versus absence of the complementizer seems to vary across languages: English allows embedded gapping only in the absence of that, as in Example (49), whereas Spanish (or Romanian) has embedded gapping with an overt complementizer, as in Example (50). So in these languages, either the gapped clause is finite or the complementizer is compatible with a non-finite clause, unlike in English.Footnote 28 In addition, a language such as Persian allows embedded gapping with both overt and omitted complementizer, as in Example (51), though experimental studies (Bîlbîie & Faghiri Reference Bîlbîie and Faghiri2022) suggest a preference for the absence of complementizer.

If one tries to explain the specific behaviour of embedded gapping in English, this could be related to the availability of competing variants. First, the fact that English has two options for embedding, namely, with and without that, imposes the selection of one of them for embedded gapping (and fragments in general). This may be a factor that significantly degrades embedded gapping with an overt complementizer. Languages such as Spanish or Romanian, which do not have two variants for embedding, only allow embedded gapping with an overt complementizer. Persian, which allows both of them, still manifests a preference for complementizer drop in such contexts (like English).

Second, the existence of an alternative elliptical construction in English, which is not available in the other languages under discussion, could also explain the specific constraints on embedded gapping in English. In particular, English has an alternative with pseudogapping that Spanish, Romanian or Persian do not have (Farudi Reference Farudi2013; Bîlbîie Reference Bîlbîie2017); whereas one cannot embed gapping under that, one can easily embed pseudogapping under that, as illustrated by the attested data in Example (52) from Miller (Reference Miller and Piñón2014).

Third, languages may differ with respect to the preference between an elliptical construction and its non-elliptical counterpart: our experimental results from English show that, without embedding, there is a general preference for non-gapping constructions in English (as observed by Carlson Reference Carlson2001); on the other hand, no clear preference for either gapping or non-gapping construction was attested in Romance languages (Bîlbîie et al. Reference Bîlbîie, de la Fuente and Abeillé2021), whereas in Persian, a clear general preference for gapping was observed (Bîlbîie & Faghiri Reference Bîlbîie and Faghiri2022). The fact that gapping has a very low frequency in language use in English (Tao & Meyer Reference Tao and Meyer2006) could be related to this ellipsis penalty in this language. This general preference for non-gapping may give rise to a superadditivity effect with embedded gapping: an elliptical construction, such as gapping, which is rare and less preferred compared to other elliptical constructions in English, is moreover constrained when it comes to embedding.

6. Conclusion

In this study, we have shown that the ‘No Embedding Constraint’ proposed for gapping in English is not a strong syntactic constraint. Controlled experiments show that embedded gapping is indeed acceptable in English but seems to be modulated by the presence/absence of that, as well as by a semantic tripartition of the embedding predicates (non-factives vs semi-factives vs true factives). In order to account for these facts, we have proposed a construction-based fragment analysis, where the gapped clause is a non-finite fragment that has to address the same QUD as its source. We conclude that the ‘No Embedding Constraint’ cannot be used as a diagnostic of gapping (pace Johnson Reference Johnson2014: 8). After all, gapping has a similar behaviour as fragments in general, with respect to embedding, as hypothesised by Weir (Reference Weir2014), Boone (Reference Boone2014) and Wurmbrand (Reference Wurmbrand2017). The research we presented here shows that an approach that combines theoretical, experimental and cross-linguistic data is optimally suited for the investigation of the constraints applying to ellipsis phenomena.