Monte Irvin saved Roberto Clemente for last. On 6 August 1973, Irvin, who first made his name as a versatile left fielder for the Newark Eagles at the twilight of the Black leagues, stood before a podium in Cooperstown, New York, and acknowledged his fellow Hall of Fame inductees: George “High Pockets” Kelly, Warren Spawn, and, “of course, my real good friend Roberto Clemente.”Footnote 1 Clemente had died that winter in a plane crash off the coast of Puerto Rico, and Irvin glanced at his friend's widow, Vera, seated onstage, as he spoke. He had met Clemente a long time ago in San Juan, he said. Irvin reflected on his playing days there and in Venezuela, Mexico, and Cuba before, at thirty, twelve years into his professional career, breaking into Major League Baseball. His Hall of Fame plaque – “Negro Leagues 1937–1948, New York N.L., Chicago N.L., 1949–1956” – didn't acknowledge his time in the Caribbean and Mexican leagues. Irvin had been, for the Hall and in that week's news, an icon of civil rights and integration, a man who took his talents from the Black leagues to the big leagues and showed a wider public what he could do.

Clemente, his late friend, an Afro-Puerto Rican as Black as Irvin, received a different kind of tribute. The New York Times declared that his induction, in an unprecedented special election that spring, had made him “the first Latin-American player picked for the museum at Cooperstown.”Footnote 2 The Atlanta Daily World, the long-running Black newspaper, agreed: Clemente's stood as “the first induction of a Latin American player.”Footnote 3 The Baseball Hall of Fame had, that August day, celebrated two men for breaking new ground in the game – one Black, the other, in the emerging language of the time, Latin.

The Puerto Rican great had idolized Irvin as a child in the mid-1940s. On weekends, he would take the bus from his home in Carolina, east of San Juan, to Sixto Escobar Stadium to see Irvin roam the outfield for the Senadores. “He not only was a good hitter but had a very good arm,” he recalled of his childhood hero. “Even my friends called me Monte Irvin as a nickname.”Footnote 4 Clemente waited outside the stadium before games, hoping to catch a glimpse of Irvin, who, like other Black American stars of the time, cobbled together a living with income from the Black leagues, winter ball in the Caribbean or Mexico, and barnstorming in between. Irvin noticed the local kid milling around the entrance and invited him to walk in with him. Clemente saved fifteen cents and gained a mentor. “I taught Roberto how to throw,” Irvin said. “Of course, he later surpassed me.”Footnote 5

Clemente could see himself in Irvin, Irvin in Clemente – an Afro-Puerto Rican and an African American who lived for baseball. No one noticed the resemblance in 1973. Irvin's career had been domesticated. Clemente's had been abstracted from Black baseball. The two men who had first met outside a stadium in San Juan arrived, thirty years later, on opposite sides of a Black/brown color line.

C. L. R. James had confronted that line on another island and in another sport. The future playwright, historian, and pan-Africanist had first, as a young man on colonial Trinidad, dedicated himself to cricket. After graduating from Queen's Royal College, a prestigious boarding school in Port of Spain, he joined a club team that he remembered, in his classic memoir Beyond a Boundary, as “a motley racial crew” of Black and brown cricketers and one white man, “a Portuguese of local birth, which did not count exactly as white (unless very wealthy).” When the club disbanded at the end of his first season, James had a decision to make, a decision that, he wrote, “plunged me into a social and moral crisis.”Footnote 6 The island's white elite and Catholic clubs wouldn't have him, a Black Protestant, leaving James with two options: the club of the brown-skinned middle class, which, overlooking his dark skin, had invited him to join, and that of the Black lower middle class. He chose the former, a decision that he came to regret, believing that it had taken him “to the right” and stunted his “political development for years.”Footnote 7 Club cricket had forced him, a defensive batsman with a nascent anticolonial consciousness, to take a side in the island's racial struggle, a struggle not limited, he discovered, to color.

It took James years to fully comprehend the political significance of his club affiliation. “Between the brown-skinned middle class and the black,” he later wrote in The Life of Captain Cipriani, his first book, “there is a continual rivalry, distrust and ill-feeling, which, skillfully played upon by the European peoples, poisons the life of the community.”Footnote 8 James had made the wrong choice, he thought. But he also had no choice. The Black/brown division didn't serve him. It didn't serve the interests of Black and brown people. Race on Trinidad had to do with skin color but also with class, education, and other status markers. The Portuguese cricketer was white but, because he was born on the island and lacked an inheritance, not too white. So he landed on the mixed-race club. James was Black but, because he was educated at QCR and had taken to delivering lectures on Wordsworth and Longfellow at local salons, not too Black. So the brown-skinned club recruited him. The color line governed race on the island, but it often bent, blurred, shifted. It gave rise to other lines and categories of difference. But that variation did not, the older James determined, destabilize the color line but strengthen it, obscuring white dominance in the Caribbean behind a young cricketer's decision between Black and brown.

James published Beyond a Boundary in 1963, a year in which Clemente hit .320 for the Pittsburgh Pirates, played in his fourth consecutive All-Star Game, and witnessed a new racial division forming, one that alienated him from his idol Irvin. The future Hall of Famer, whose father had made his living in the sugarcane fields on the northeast coast of the island, debuted with the Pirates in 1955. Jackie Robinson had integrated the league in 1947, two years ahead of Irvin, and most liberal baseball writers had received his first season with the Brooklyn Dodgers as further evidence of the game's democratic national character. Robinson and the man who signed him, Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey, had, in their accounts, bent the moral arc of the universe, reminding Americans of the better angels of their nature. Few knew what to say about Clemente, a Black man, a Puerto Rican, an American citizen who couldn't vote but not because he lived in the South. Clemente's own team recognized Curt Roberts, a second baseman from Oakland, California, who took the field for Pittsburgh in 1954, as the first Black Pirate, when the Afro-Puerto Rican outfielder Carlos Bernier had started close to a hundred games for the team in the 1953 season. What made Robinson, Irvin, and Roberts Black and Clemente and Bernier not – or at least not Black enough to count as integrators? Whose interests, as James might have asked, did that distinction, the distinction between Black and brown, serve?

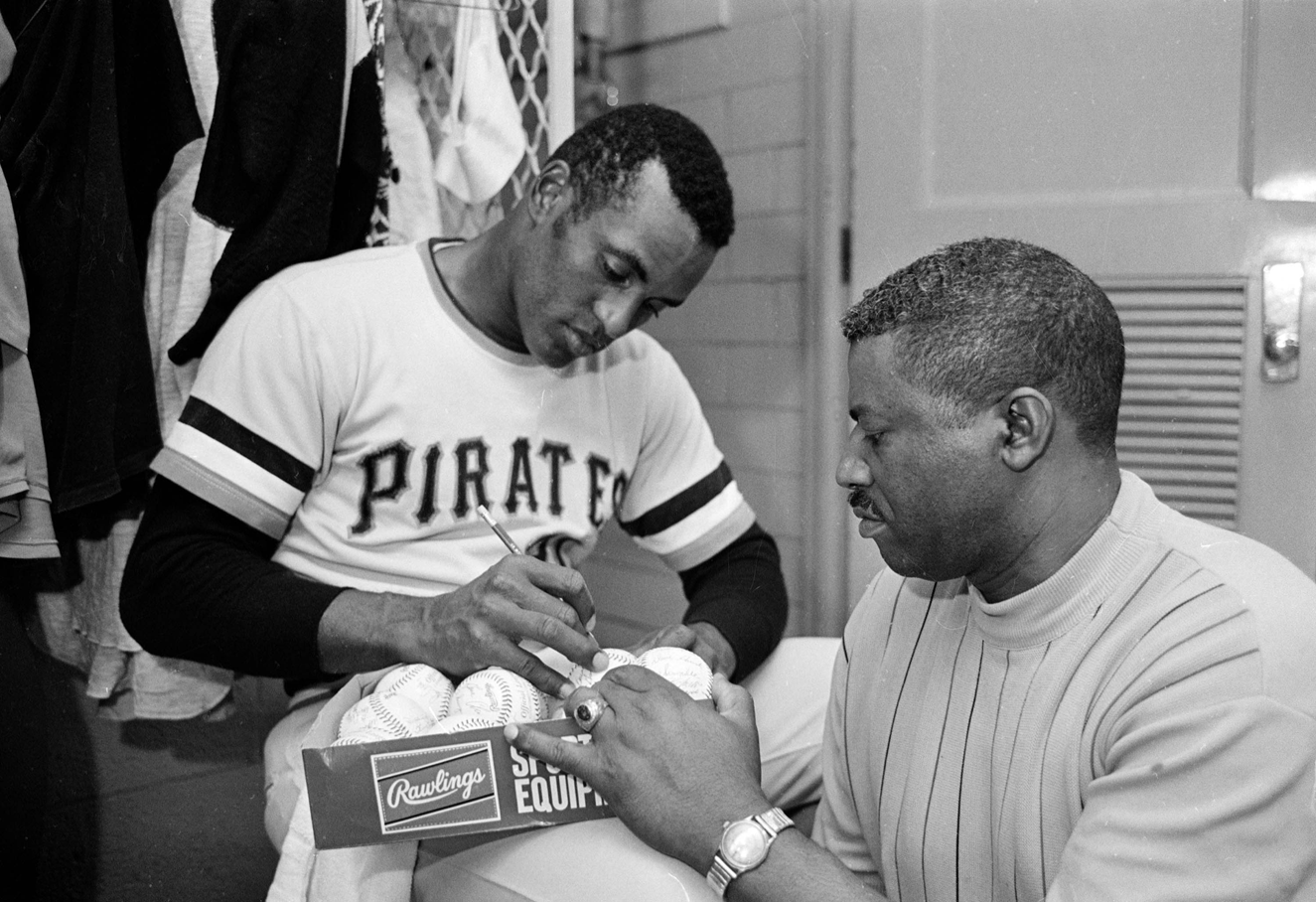

Figure 1. Left to right: Roberto Clemente, Willie Stargell, and Donn Clendenon at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh in 1965. Photograph by Charles “Teenie” Harris. Reproduced by permission from the Carnegie Museum of Art.

Most baseball writers and fans assume that the integration of baseball unfolded in two waves: first the Black wave of Robinson, Irvin, Willie Mays, and Hank Aaron, then the “Latin” wave of Minnie Miñoso, Clemente, Juan Marichal, and, later, Fernando Valenzuela and thousands more. But the waves, as historians of Latino baseball have documented, didn't come one after the other.Footnote 9 Before Robinson, general managers looking for an edge but unwilling to break the game's racial code sometimes turned to Latino players, including Afro-Latinos, who often carved out careers in the Black leagues (as non-Latino Black players did in the Caribbean and Mexican leagues), to give their rosters a boost. Clark Griffin, the owner of the Washington Senators and a stanch segregationist, recruited Cubans – including one or two Afro-Cubans, some suggest – to his club in the 1930s and 1940s. Branch Rickey himself considered Afro-Cuban infielder Silvio García a candidate for integrating the Dodgers before Robinson. Latinos, the historian Adrian Burgos writes, “acted as test subjects in a battle over the color line's half century leading up to baseball's ‘great experiment.’”Footnote 10

Clemente entered that league, a league in which Latinos and Latin Americans had long straddled the color line, sometimes raced Black, sometimes white, sometimes, when it suited Griffin and Rickey, neither. His major league career, which stretched from 1955 until his death in a plane crash on New Year's Eve of 1972, coincided with dramatic changes in how Americans thought about race. If sportswriters didn't know what to say about Clemente's background in 1955, they didn't hesitate when they sat down to write his obituary in the first hours of 1973. Clemente, once illegible in sportswriters’ stories of Black–white integration, had come to stand for what they called the Latin game. When the Puerto Rican star came to bat at Pittsburgh's old Forbes Field, Pirates broadcaster Bob Prince would, summoning the image of the sombreroed cartoon mouse Speedy Gonzales, call out, “Arriba! Arriba! Arriba, Roberto!”Footnote 11 When the Hall of Fame honored him alongside Irvin, no sports page failed to mention that it made Clemente the first Latin American enshrined at Cooperstown.

Historians of race have traced the “making” or “inventing” of a panethnic Latinx identity to the noisy, post-civil rights convergence of social movements, federal agencies, and ethnic media organizations.Footnote 12 But for Americans disinclined to take it to the streets or advocate for changes to the Census form, baseball had already offered a casual environment for thinking (or not thinking) about what it meant to be Cuban, Dominican, Mexican, or Venezuelan American or a stateside Puerto Rican and what it might mean to see that “motley racial crew,” in James's words, as one.Footnote 13 In distinguishing Latino and Latin American players from, and often setting them against, their Black and white teammates, sportswriters encouraged fans to see MLB clubhouses as breaking down into three nonintersecting wings: Black, white, and brown. Their writing on the national game, which reached a far wider and more consistent audience than President Nixon's Cabinet Committee on Opportunities for Spanish-Speaking People or the Census Bureau, contributed to the formation of an uncritical multiculturalism that did not destabilize but sustained anti-Black ness and white dominance as the nation's anchoring racial ideologies. The image that sports media constructed of Clemente and other Caribbean MLB stars grounded emerging ideas about Latinos after civil rights: that Latinos remained, no matter the generations or Indigenous roots, immigrants and foreigners in the United States; that Latino named not a racial but an ethnic form of difference, something in between, neither Black nor white, a kind of stabilizing buffer between Blackness and whiteness. The Latin player of the civil rights era paved the way for the panethnic Latino constituency – the chimeric “Latino vote” – of the ensuing decades.

The historian Allen Guttmann once wrote that “exclusion on the basis of race” is “clearly an anomaly within the structure of modern sports.”Footnote 14 It originated, he argued, with the segregation of the once Black-dominated Kentucky Derby after Reconstruction and ended with Robinson, Rickey, and the arrival of the civil rights movement. Scholars of race and sport have disagreed, of course, countering that sports were “born out” of and remain mired in the divisions that Guttmann cast as anomalous.Footnote 15 But Guttmann might have been right, or at least half right. Exclusion did end in some sports because anti-Blackness had changed, taking new form after civil rights. Sometimes, in fact, it took the form of inclusion.

Baseball historians have hailed the 1971 Pittsburgh Pirates – the “Black nine,” the “all-soul” Bucs – as “the team that changed baseball.” Never before, Clemente biographer Bruce Markusen writes, had MLB fielded a team “assembled purely on available talent with no consideration of skin color.”Footnote 16 With the iconoclastic Dock Ellis winning nineteen games and Willie Stargell hitting a league-leading forty-eight home runs, the ’71 Pirates won fans in the Black Power movement. But white sportswriters often accentuated clubhouse tensions between the non-Latino Black Pirates and their Latin American teammates, casting Clemente and other Afro-Caribbeans against a movement with which they often identified and modeling how multiculturalism would later be used to defuse and divide the radical, cross-racial, often transnational coalitions of the time. The unwillingness of broadcasters and writers to engage with Clemente's background as an Afro-Puerto Rican allowed baseball fans to set aside the histories it signaled, including the routes of the transatlantic slave trade, American colonialism in the Caribbean, and the wider circulation of anti-Blackness and colorism. Baseball media transformed the dominant integration framework of Black and white into something more subtle after civil rights. The white men in the broadcast booth and the newsroom detached themselves from discourses of racial and ethnic difference with a shift from the Black/white binary of integration to the Black/nonwhite binary of multiculturalism, of Black and brown without white.

Black and Latino players didn't like each other. That's what sportswriters decided at the height of the civil rights movement. When Sports Illustrated asked Robert Boyle in 1960 to investigate the lives of Black MLB players, he returned with a story not of Black life in a white business but of a mutual distrust between Black and Latino teammates, all of whom he described as “Negroes.” Black players had “certain reservations” about their “Latin Negro” teammates, he wrote. “Latin Negroes do not willingly mingle with American Negroes off the field.” Boyle, an early SI staff writer, traced that uneasiness to “the segregation issue” and to “the American Negro's low status in U.S. society in general,” suggesting that Latino and Latin American players, including Afro-Latinos, distanced themselves from their non-Latino Black teammates to elevate their own racial status.Footnote 17 Alex Pompez, the Cuban American director of international scouting for the San Francisco Giants and a former Black league club owner, told Boyle that Black Latin Americans often struggled to adjust to the segregation of the American South. One Black player felt that his Latino teammates looked down on him. “I'm not any better than they are,” he said, “but I'm not any worse, either. They think they're better than the colored guy.”Footnote 18 Boyle, who didn't interview any active Latino or Latin American players for his story, described all athletes of color as Black but concluded that “Latin Negroes are not Negroes, at least as far as they themselves are concerned.”Footnote 19 Thirteen years after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier, Boyle nudged that barrier from Black/white toward Black/brown, recasting Afro-Latinos – by their own choice, he suggested – as Latin.

The belief that Latin American players had it better than, and might want to disassociate themselves from, their Black teammates originates with the name of a Black American professional club that formed on Long Island in 1885: the Cuban Giants. Sol White, an infielder with the club and an early historian of Black baseball, later told Esquire that he and his teammates had “passed as foreigners” and often “talked a gibberish to each other on the field which, they hoped, sounded like Spanish.”Footnote 20 Historians have since raised doubts about White's account, but the idea that Black ballplayers identified as Cuban out of a sense of mischief and racial self-interest stuck, lodging itself in Black league lore. Some suggest that Black clubs might have instead adopted the name in a gesture of racial solidarity amid the island nation's wars of liberation against Spain.Footnote 21 Most of the Cubans whom Black players encountered at the time would have been Black themselves and no better off after Reconstruction, not that white promoters would have bought the charade that White described, had his Giants ever tried it. (Pompez subsequently reclaimed the name for his Cuban Stars, a Black league team composed of Cuban and other Latin American players, and for his New York Cubans, a club of Latin American and Black American players. His teams' names signaled not an atmosphere of appropriation and mockery but of transnational intimacy and institution building.)Footnote 22

Revolutionary Cubans traveled the Black baseball circuit in the late nineteenth century and associated the sport with resistance to the Spanish Empire, for which bullfighting stood as the height of sporting achievement.Footnote 23 The tale that early Black clubs had attempted to pass as Cuban to receive better treatment, to secure some of the wages of whiteness, transformed a sign of diasporic consciousness – of Black Americans seeing themselves in Afro-Cubans and Afro-Cubans seeing themselves in Black Americans – into an act of racial deceit, a gag, something an Esquire reader could laugh at. Baseball could be an expression of freedom and resistance and also an instrument of racial division with which media and management disciplined difference.

The invention of Latin ball preceded the panethnic terms Hispanic and Latino. Historians of Latinx panethnicity trace the emergence of that identity to the 1970s, when Cuban and Mexican Americans and mainland Puerto Ricans with often radically different backgrounds adopted a new secondary identification as Hispanic or Latino. Most credit the uneven convergence of social movements (Boricua and Chicano), federal agencies (the Cabinet Committee on Opportunities for Spanish-Speaking People and the Census Bureau), and media organizations (Univision) in the making of Latinx panethnicity. That convergence left unanswered whether Latino constituted a race, an ethnicity, or something else. The Census Bureau decided to include a “Spanish/Hispanic origin” question as a supplement to the race question in the 1980 Census (a strategy it had piloted in 1970) out of a concern that combining them could lead to decreases in the Black, Native, and white counts in some regions, upsetting other constituencies and undercutting the integrity of past data.

The compromise sowed confusion. The bureau maintained that Spanish/Hispanic did not constitute a race but then interpreted the data as if it did, sorting Black, Hispanic, and white into nonintersecting categories (“non-Hispanic Black,” “non-Hispanic white”). “Although technically Hispanics could be any race,” the sociologist Cristina Mora writes, “the racial analogies made the Hispanic category seem race-like.”Footnote 24 The ambiguity of the term, the legal historian Laura Gómez adds, has made Americans reluctant to name anti-Latino racism as racism and has sometimes set Latinos against their Black neighbors as striving ethnic immigrants, American dreamers pulling themselves up by their bootstraps. The Census has been, in Gómez's words, “a primary race-making site.”Footnote 25 But most Americans didn't then (and don't now) think twice about Census data. Long before the Census Bureau added a Hispanic-origin question, baseball broadcasters and writers had been speculating, 162 days a year to a mass audience, about the Cuban, Dominican, Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Venezuelan players who formed a panethnic fraternity in Major League Baseball, the future Latinos of the national pastime.Footnote 26 For the vast American sporting public, the image of the Latin ballplayer that sports media had presented in the 1960s smoothed over the incoherence of the Hispanic category that the government introduced in the next decade.

Sociologists and political scientists have raised parallel questions about the changing face of Black life in the United States. Since the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, many Black immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean have resettled in the United States, often achieving, as the sociologist Tod Hamilton observes, “greater social and economic status than black Americans” because they arrived “at a time of expanding opportunities for minorities and for women” and because of “selectivity in migration” (wealth, education).Footnote 27 Hamilton worries that ignorance of the patterns of Black immigration gives policymakers a false impression that Black Americans have made dramatic economic gains since civil rights, when a closer look at the data reveals a more sobering truth. Few studies, he notes, account for the differences between a descendent of people enslaved in the American South and a first-generation Nigerian American.

The political scientist Christina Greer identifies among Black immigrants what she terms an “elevated minority status,” wherein Africans and Afro-Caribbeans in the United States seek to remain “perpetual outsiders and forever foreign so as not to ever fully incorporate themselves into the black American populace” – “an extension of the model minority,” she calls it.Footnote 28 Greer's model casts Black immigrants as the authors and primary beneficiaries of that differentiation, as having observed the anti-Blackness of their adopted country and distanced themselves from native-born Black Americans in an act of self-preservation. The post-1965 negotiation of difference in baseball tells a different story, a story of white executives and sportswriters defining the boundaries of Blackness to elevate not Afro-Caribbeans over Black Americans but themselves over athletic labor and the content of their columns.

Some general managers didn't want Afro-Caribbeans to integrate their teams. The Afro-Puerto Rican first baseman Vic Power, a future six-time All-Star, languished in the minor leagues from 1951 to 1953, waiting for Yankees general manager George Weiss to call him up. He hit .331 for the club's top minor league affiliate in 1952 and then led the league in batting in 1953. “The Yankees never have been averse to having a Negro player,” Weiss said, when a reporter asked him about Power. “Our attitude has been that when a Negro comes along who can play good enough baseball to win a place on the Yankees, we will be glad to have him, but not just for exploitation.” He added, without using Power's name, that “the first Negro to appear in a Yankee uniform must be worth having been waited for.”Footnote 29 The other two New York teams, the Dodgers and the Giants, had integrated their rosters, and Weiss had to explain why his club hadn't. He blamed Power, the Yankees’ top Black prospect, for being the wrong kind of Black player. Power didn't conform to Weiss's conservative standards – the Puerto Rican had little patience for mainland racial mores, often dating white women and lighter-skinned Latinas – but the general manager also wanted the kind of press that Branch Rickey had received for signing Robinson. He didn't think he'd get it for promoting an Afro-Puerto Rican to the big leagues. So he never did, trading Power to the Philadelphia Athletics before the 1954 season. The hollowing out of the Black leagues through one-directional integration had rendered Black and Latino players pure labor, with no controlling stake in the future of the game, and the division of that labor, into Black and brown, gave white owners and managers an additional lever of power. Pompez, the former Black league club owner, who made the transition to the majors as smoothly as anyone, still found himself working as a scout for an organization that could dismiss him as easily as Weiss did Power.

Jim Bouton, who pitched for the Yankees, Seattle Pilots, and Houston Astros in the 1960s, described MLB clubhouses as hostile environments for Latino and Latin American players in his landmark 1970 memoir Ball Four. He remembered a white player telling an injured Dominican teammate to “talk English! You're in America now” – a common complaint in New York, Seattle, and Houston, Bouton admitted. But he singled out coaches and general managers as the worst offenders. Joe Schultz, the manager of the short-lived Pilots, referred to all Latinos and Latin Americans on his team as “Chico.” Spec Richardson, the general manager of the hapless Houston Astros, once climbed onto a team bus and stared at five Latino players speaking Spanish to one another. “He stood listening for a while, his eyes shifting back and forth, as if he understood what they were saying,” Bouton wrote. “Finally he said, ‘Abbadabba dabbadabba.’”Footnote 30 Richardson controlled their contracts and could trade them whenever he wished.

Latin American athletes needed a “bill of rights,” Felipe Alou, the San Francisco Giants outfielder, decided in 1963. After MLB commissioner Ford Frick fined him and other Dominican players $250 each for participating in exhibition games against a Cuban squad in his hometown of Santo Domingo, he accused the league, in a long essay in Sport magazine, of a willful ignorance of his and other Latin Americans’ situations. The games had been organized, Alou explained, as goodwill exhibitions for a nation enduring political turbulence after the assassination of dictator Rafael Trujillo, and most Dominican pros, unable to find other offseason work, needed the money from winter ball. “We had to play the Cuban series,” he wrote. “You have to know all this before you can understand why I was so angered by the action of Mr. Frick.” Players from Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela had their own unique histories with the league, Alou acknowledged, but their poor treatment in professional baseball had united them. Although his own citizenship status made earning a living in the United States more difficult, he observed that an American passport didn't shield his Puerto Rican teammate José Pagán from anti-Latino racism. Pagán “is treated the same way as any Latin who is not an American citizen,” Alou wrote. “This means that the Puerto Ricans find themselves closer to other Latins than to other Stateside players. It makes foreigners out of a country's citizens.”Footnote 31 Their manager, the notorious Alvin Dark, had issued an English-only clubhouse policy in 1962, and Alou, Pagán, and other Latinos and Latin Americans resolved to respond as a panethnic alliance. Raced as Latin, they turned around and demanded a bill of rights for that race.

Alou, an Afro-Dominican, could see his identity being cleaved. When the Giants signed him in 1956 and sent him to a Class D affiliate in Lake Charles, Louisiana, he, new to the United States, roomed with a Black player from Harlem. Most of his teammates and most of the people in the town identified him as Black, not Dominican or Latin. That changed in the big leagues, where he experienced a kind of racial reshuffling, first raced Black, then as “Black Latin,” then as just Latin, an identity parallel to but, he discovered, dissociated from Black. White managers and sportswriters assigned different negative attributes to Black and Latino pros, suggesting that Black players “chocked” while Latino players didn't hustle or had “no guts.”Footnote 32 Their anti-Black and anti-Latino assumptions derived from a common set of what the historian Natalia Molina calls “racial scripts” – ideas about weak work ethic and timidity have a long history in anti-Black thought – but they functioned in the 1960s, Alou noticed, to separate Blackness from brownness while freeing whiteness, unnoticed, from that racial scrum.Footnote 33 He and other Latin American players sought to repurpose the identity to their own ends – to turn it into a platform from which to make demands on management – but ran up against a white sports media industry that increasingly cast them in opposition not to the commissioner or the owner but to their own teammates.

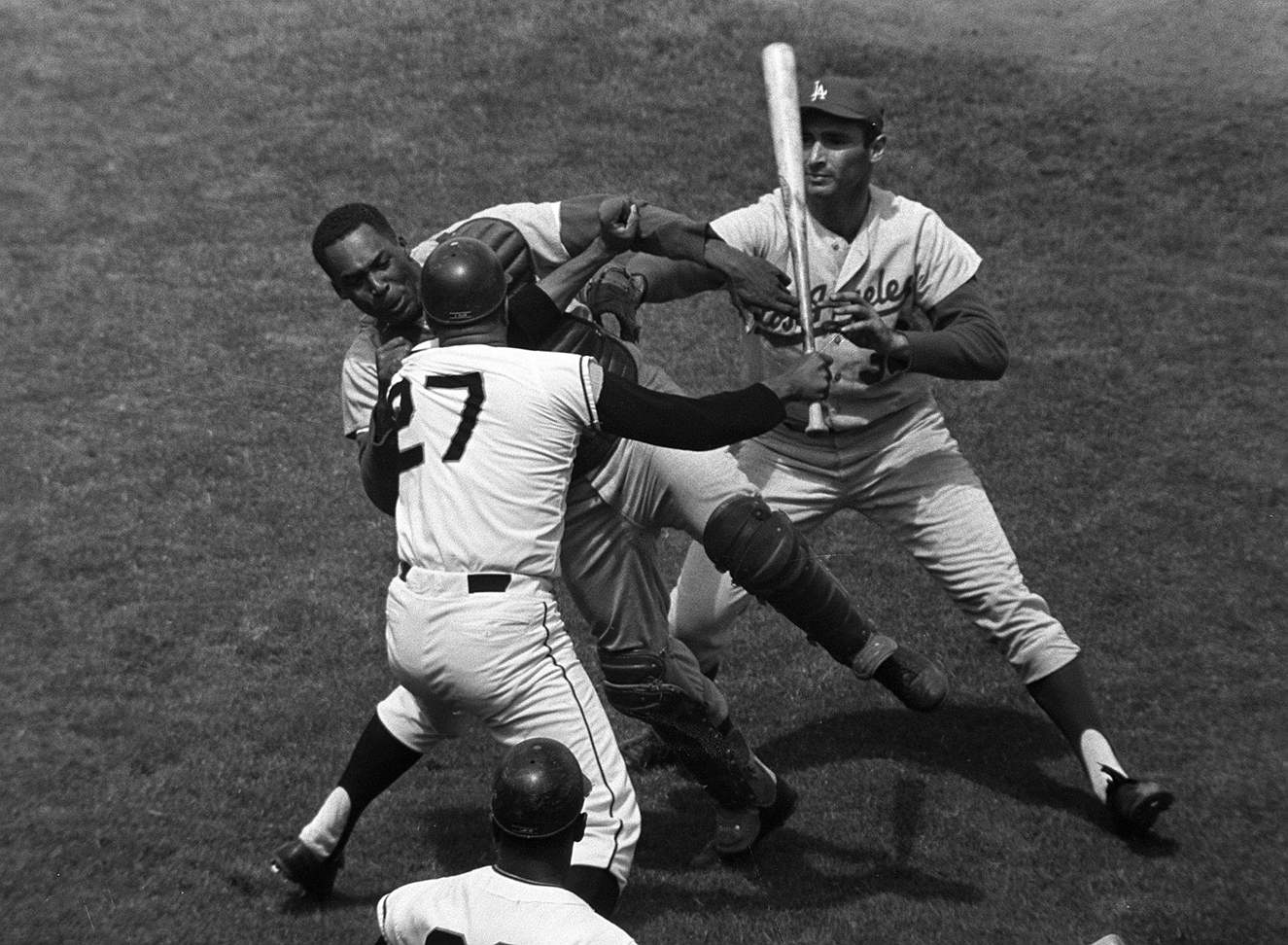

A flashpoint in MLB's racial reordering came on 22 August 1965, when Giants Afro-Dominican ace Juan Marichal hit the Los Angeles Dodgers Black catcher John Roseboro over the head with his bat. Roseboro had grazed Marichal with the ball as retaliation for the Giants pitcher having beaned two Dodgers earlier in the game, and Marichal swung at him, setting off a dugout-clearing brawl. Marichal received an eight-game suspension and a $1,750 fine. Most white sportswriters framed the incident as evidence of widespread Latino animosity toward Black players in the league. “The true problem is that the American Negroes and the Latin Negroes do not like each other – not even a little bit,” Dick Young of the New York Daily News wrote of the Marichal–Roseboro incident. “They are on the opposite sides even when they wear the same uniform.”Footnote 34 Bob Broeg, the sports editor of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, described Marichal's actions as characteristic of “a tendency of Latin American ball players to fight with weapons other than their fists,” which he condemned as “dangerous and despicable” and as setting a poor example for the “hero-worshipping small fry.”Footnote 35 Willie Mays of the Giants had shielded his friend Roseboro during the fight, leading Young, Broeg, and others to conclude that Mays had perceived his teammate Marichal's actions as racially motivated, an attack on all non-Latino Black players. White sportswriters, whatever their interpretation of the specifics, turned the fight into a representative event, a spectacular uncorking of pent-up hatred between Black and Latino players – and, by extension, Black and Latino communities. They didn't have much other evidence to cite. For them, one example made a pattern.

Figure 2. Juan Marichal (27), Joe Roseboro (center), and Sandy Koufax (right) at Candlestick Park in San Francisco in 1965. Photograph by Robert H. Houston. Reproduced by permission from AP Photo.

Joe Black, the former Dodgers pitcher, countered their analysis in the New York Amsterdam News, then among the most widely read Black newspapers in the country. He dismissed the idea that Black and Latin American athletes disliked one another as a “ridiculous theory,” reminding readers that the Black leagues, in which he had played for six seasons before signing with the Dodgers, had a long history of exchange with the Caribbean and Mexican leagues.Footnote 36 But Black found himself swimming against a current of white baseball men agreeing with one another that something called Latin ball now stood apart from and against Black baseball, one forever swinging a bat at the other.

“I'm Puerto Rican. I'm Black. And I'm between the wall,” Roberto Clemente told Sam Nover of the Pittsburgh NBC affiliate WIIC-TV in 1972.Footnote 37 The mainland press had, he said, never made space for the complexity of his family history. Over the course of his long career, it had recategorized him, an Afro-Puerto Rican raised in the shadow of the island's sugarcane plantations, as Latin. It had obscured the story his background told of empire, slavery, and capital. It had stuck him between the wall.

Clemente, the most prominent Caribbean athlete of his generation, whose career coincided with the rise of civil rights and Latinx panethnicity, had watched that wall go up. In 1960, his Pirates had faced the Yankees in the World Series. Life magazine, with a circulation of more than five million, enlisted Jim Brosnan to break down the Pittsburgh lineup. The editors introduced Brosnan, an unexceptional relief pitcher for the Cincinnati Reds, as a “highly literate man,” and Brosnan framed his scouting report as “my book on the Pirates.” Of the Pirates right fielder, he wrote, “Clemente features a Latin-American variety of showboating. ‘Look at número uno,’ he seems to be saying.” Brosnan described how Clemente had earned a reputation as “hard-headed” when, while running from first to second, he had taken a ball between the eyes and “didn't even blink.”Footnote 38 The Reds pitcher, who a few years earlier might have identified Clemente as Black, portrayed his style of play, behavior, and intelligence as a manifestation of his Latinoness. He offered the Yankees bullpen a racial scouting report: pitch to Clemente as you would any Latin American batter.

Brosnan epitomized an emerging character in sports media: the white intellectual athlete. In 1958, Sports Illustrated ran an excerpt of his diary (“the uninhibited diary of a professional ballplayer”) with a photograph of the relief pitcher, then with the St. Louis Cardinals, smoking a pipe. “The pleasant young fellow on the left looks like a professor,” the caption read. “He wears glasses, smokes a pipe, reads good books and welcomes conversation on any subject from religion to real estate.” Sports Illustrated introduced Brosnan as the “antithesis” of Ring Lardner's uneducated, headstrong fictional ballplayer Jack Keefe.Footnote 39 He might lose more games than he wins, but Brosnan, the editors insisted, made up for it with a one-of-a-kind mind, an eccentric genius among jocks. When Harper and Brothers published Brosnan's diary as the 1960 book The Long Season, it landed him on the best-seller list, creating an opening for Jim Bouton and other white journeyman athletes to distinguish themselves (and make a buck) off the field, as a growing number of Black and brown pros outmaneuvered them on it.

Brosnan, who had spent one semester as Xavier University, fashioned himself as a student of race. In The Long Season, he recounts a conversation with Brooks Lawrence, a Black teammate on the Reds, in which he surprises Lawrence with his knowledge of jazz music. “I didn't know you like jazz, Brosnan,” Lawrence remarks. “What do you dig? Basie? Progressive? Dixieland?” “I try to make every scene, man,” Brosnan tells him. When he notices that Lawrence only mentions Black artists, he offers an aside to the reader: “This was the first time I'd talked seriously to Lawrence. Best to find out if he was stuffy about being a Negro. Some of them are. Why they feel they have to be better than us I don't know.” Brosnan presents his diary as an inside look at the MLB clubhouse, which turns into an amateur investigation into Black and Latino cultures in the sport. “It's a Negro term, isn't it?” he asks some Black teammates of an Italian anti-Black slur he hears them using. A glossary of baseball terms appearing in the front matter includes the entry “Bean Bandit: A Latin-American ballplayer.”Footnote 40 Brosnan's next book, Pennant Race, a diary of the 1961 season, reports on what he calls the “lobby of Latins” forming in the big leagues. “As a minority group in a Caucasian world, they stand out with hand gestures hypnotic and lip movements unintelligible,” he writes of finding himself, the white athlete as anthropologist, “en conclave” among Caribbean players gathered behind the batting cage.Footnote 41 The sociologist Roderick Ferguson observes that white liberals sustained their racial dominance after civil rights through “a certain investment in minority difference” that recast them as administrators of an antiredistributive multiculturalism.Footnote 42 Brosnan and other white athletes discovered that trick early, distinguishing themselves from their Black and brown teammates as clubhouse intellectuals, defining and sorting the bodies around them.

Sociologists of sport took a more critical look at the changing racial environment of the MLB clubhouse. In 1967, Harold Charnofsky, an assistant professor at Cal State Dominguez Hills who had played minor league ball in the Yankees farm system, made national headlines when he delivered a paper at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association in which he argued that “racial and ethnic equality in baseball is still a matter of expedience with respect to the dollar.”Footnote 43 The Los Angeles Times picked up the story (“Whites, Negroes Keep ‘Social Distance’”), then the Associated Press (“Social Gap Seen between Races in Big Leagues”). Charnofsky had conducted seventy-three interviews and one marathon “bull session” with active pros (fifty-eight white, nine Black, and six Latin American) and found that players formed few cross-racial friendships and that many white interviewees thought their Black teammates benefited from “favoritism” and considered their Latino teammates “temperamental.” The sociologist concluded that, while the league might have curbed overt forms of discrimination out of economic self-interest, racism endured “in a variety of subtle ways.”Footnote 44 But Charnofsky's paper, a piece of his then unfinished dissertation, did more than observe racial differences in Major League Baseball. With the full authority of science, it created them. It naturalized the idea that white, Black, and Latin American constituted discrete identities, separate categories of study. The Latin ballplayer had first to be invented – as neither Black nor white, as belonging to a third race – before he could be criticized as temperamental. When Charnofsky filed his dissertation, he included a footnote acknowledging that Latinos and Latin Americans could also be, and often were, Black. Their “development is a sociological story that merits separate attention beyond the more general discussion presented here,” he admitted.Footnote 45 But he, Brosnan, and others had already begun telling that story, with and without letters after their names.

Clemente did not care for the story sports media told or for the way they denied him the ability to tell his own. Sportswriters often quoted him as speaking an almost incomprehensible English. An infamous 1961 AP story had him saying, “I get heet and Willie scores and I feel better than good.”Footnote 46 The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette ran it under the headline “I Get Heet, I Feel Good.” Les Biederman of the Pittsburgh Press, the city's other major daily, once quoted him as explaining, “Me like hot weather, veree hot. I no run fast cold weather. No get warm in cold. Not get warm, no play gut.”Footnote 47 Clemente accused Biederman of creating “propaganda” against him and later told United Press International that he blamed writers for casting Latinos and Latin Americans as “something different entirely from the white players” and “inferior in our station of life.”Footnote 48 He could see that white baseball men had secured their own dominance of the sport, a sport with a growing number of Black and brown stars, through the administration of difference, which often involved first inventing and then hierarchizing it – rendering Latinos first as “something different entirely,” then as inferior in their “station of life.” While critics then and now point to the lack of Black and brown owners and coaches in professional sports, Clemente identified the white world of sportswriting as the complementary industry that held that racial structure in place, locating the white observer above the field of play.

Although Clemente admitted, in his 1972 interview with Nover, that he disliked “lots of writers,” not all of them raised his ire.Footnote 49 In a 1962 profile for Sport, Howard Cohn acknowledged that other sportswriters exaggerated the Puerto Rican's accent in print, a practice that, he announced, “won't be duplicated here.” Cohn observed that Clemente and other Afro-Caribbeans faced unique obstacles in Major League Baseball. “Because they speak Spanish among themselves, they are set off as a minority within a minority,” he wrote. Generalizations about Afro-Caribbeans “fall apart easily enough, of course, when individual skills and personalities are considered. But some people don't, or won't, consider them.”Footnote 50 In 1965, Arnold Hano, author of the acclaimed A Day in the Bleachers, contributed his own Clemente profile to Sport in which he asked why a player of Clemente's caliber had received almost no endorsement deals. His answer: language and race. Salaried at $50,000, the Pirates right fielder did not, Hano wrote, earn “too much extra, because Clemente is Latin and Clemente is dark-skinned, and somehow advertising agencies think that there's nothing quite like running a stainless blade over the pink cheek and fuzzy skin of a young white lad from Peoria.”Footnote 51 (Then the leading sports magazine in the United States, Sport soon lost market share to the Time Inc.–backed Sports Illustrated and faded from newsstands.) Cohn and Hano heard Clemente out. Baseball media had, he showed them, wedded race to language and language to national belonging, imagining an intermediate race of Spanish speakers who must hail from somewhere else, foreigners to the national pastime. Clemente, a Black citizen of the United States, found himself raced brown and recast as a striving immigrant.

But the Pittsburgh star found in sportswriters’ broad generalizations about Latinos and Latin Americans a site of belonging and resistance. He took it upon himself to mentor younger players from the Caribbean and Central and South America and spoke out on behalf of all Latinos and Latin Americans in the league. He made national headlines in 1966 when he told the Associated Press that professional baseball shortchanged players from Latin America, paying them less and never inviting them to off-season banquets or recommending them to corporate sponsors. “I am an American citizen. I live 250 miles from Miami,” he said. “But some people act like they think I live in the jungle some place. To the people here we are outsiders, foreigners.” He informed the AP, which described him as “brooding” and “intense,” that he had been organizing gatherings of Latin American players to talk about their concerns.Footnote 52

Some teams admitted that they looked at scouting in the Caribbean as a cost-saving measure. A talented Dominican might sign for $1,500, one team official told the New York Times, whereas a white American high-school or college prospect could demand as much as $60,000. As white players insisted on more, MLB teams recovered the money – checked the “dollar drain,” as the Times put it – by extracting greater amounts of surplus value from Latin American athletic labor.Footnote 53 Clemente thought the term Latin elided his and others’ heterogeneous racial and ethnic identities and histories with the United States, but he also recognized, as Felipe Alou had, that Latinos and Latin Americans needed to organize. The name on the banner mattered less than the alignment of interests.

When the 1971 Pirates (“the team that changed baseball”) won the World Series, sportswriters, players, and fans spoke of the team in the language of difference that had emerged over the course of Clemente's career. “You had a Latino player in Clemente, a black guy [in] Willie Stargell and you got a white guy in Mazeroski,” Steve Blass, who pitched in game seven for the Pirates, later told Markusen, the Clemente biographer. “We had the whole program covered. They were leaders. All three of them.”Footnote 54 Brosnan, Charnofsky, and Blass had come to think of the league in new racial terms: not of Black and white but of Black, white, and brown. Clemente, Stargell, and Mazeroski might have together led the ’71 Pirates, but they also, Blass implied, headed discrete racial wings of the clubhouse.

The civil rights struggle brought to the surface what the political scientist Claire Jean Kim describes as twin racial binaries. “The White/non-White binary, for all of its influence, has been contingent on the non-Black/Black binary, which structures the terms within which it plays out,” she writes.Footnote 55 White dominance depends on anti-Blackness and the recruitment of non-Black people of color to that anti-Black regime, creating a ceiling above which Arabs, Asians, and Latinos cannot rise (whiteness) and a floor below which they cannot sink (Blackness). The Black/white binary obscures how non-Black people of color do not straddle one binary but, Kim argues, buffer two. But the story of the white sportswriter and the invention of Latin ball suggests the emergence of a new binary after civil rights: Black/nonwhite. White baseball men moved Clemente from Black to nonwhite but also removed themselves from the racial scene, obscuring white dominance while attributing anti-Blackness to Latinos and Latin Americans. Mazeroski retired. Empire and slavery vanished into multiculturalism. White supremacy slipped out of sight, into the stands and press box overlooking the players on the field.

Clemente might have found himself caught between racial binaries – “between the wall,” as he put it to Nover – but he lived in Black Pittsburgh.Footnote 56 In 1955, Pirates pitcher Bob Friend introduced the Puerto Rican rookie to Phil Dorsey, a Black postman with whom Friend had served in the Army Reserve. Clemente had been living in a cramped downtown hotel room, and Dorsey set him up with his friends Stanley and Mamie Garland, a Black couple with a spare room in Schenley Heights, a hub for Black culture in the city's Hill District. Clemente's first and best friend in Pittsburgh, Dorsey took the newest Pirate to the Crawford Grill, the renowned jazz club where John Coltrane, Miles Davis, and Charles Mingus played. Gus Greenlee, owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords of the Black leagues, had founded the club in the 1930s, and it remained a hangout for visiting Black athletes into the 1950s. Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella could be found there whenever the Dodgers came to town. Dorsey and Clemente shot pool at the local Y and at a bar that Dorsey's brother owned in Homewood, another of the city's Black neighborhoods. The press knew Dorsey as Clemente's constant companion and protector, nicknaming him “Pittsburgh Phil.” Dorsey, who liked the nickname, had mock business cards printed up: “Pittsburgh Phil, representing Roberto Clemente.”Footnote 57 The young outfielder ate every night with the Garlands, whom he referred to in later years as his American parents. Black players from the States showed him and other players from the islands how to navigate mainland segregation. “Wait a minute,” Joe Black, the Dodgers pitcher, remembers telling one of his Puerto Rican teammates who wanted to go clothes shopping, “Let somebody go with you cause you can't just walk in all these stores.”Footnote 58 Clemente wasn't Latin in 1950s Pittsburgh. He was Black.

Figure 3. Roberto Clemente and Phil Dorsey in 1971. Reproduced by permission from AP Photo.

Others remember Clemente's first years with the Pirates differently. Bill Nuun, a sportswriter for the Pittsburgh Courier who lived four blocks from the Garlands, later told an interviewer that Clemente had been an outsider in Schenley Heights. “I think it was always tough for Clemente,” he said. “For years in the black community there was a little tension with blacks from other countries. There were no Puerto Ricans to speak of, not like in New York. The thing here was steel mills, which didn't draw workers from the Caribbean.”Footnote 59 Black Americans and Afro-Caribbeans didn't get along, he suggested, and that had left Clemente on the outside of the Schenley Heights and Homewood communities. But Nuun might have projected a later assumption about intraracial tension onto the 1950s. How could there be tension between Black Americans and Afro-Caribbeans if there wasn't a Caribbean American community in Pittsburgh? Few Pittsburghers, Black or white, would have identified Clemente as anything other than Black (and perhaps Puerto Rican) in 1955 because the panethnic identities of Hispanic and Latino had not yet entered national consciousness.

Nuun's own paper, headquartered a short walk from the neighborhood in which he and Clemente lived, wrote of the new Pirates right fielder as a native son. The Courier published an annual list of Black MLB players that didn't differentiate between players from the States and players from the islands. Clemente always received a prominent mention as one of the league's “tan stars.”Footnote 60 A 1954 op-ed asked, “How Democratic Is Baseball?” and answered, very – for white men. By paying Black players from the United States and the Caribbean less, the author observed, executives preserved a white “baseball democracy” built on the exploitation of a transnational circuit of Black labor that stretched from Pasadena, California to Carolina, Puerto Rico.Footnote 61 Nuun himself hailed Clemente's rookie season as a return to form for Black baseball: in 1954, a white player had won National League Rookie of the Year honors for just the second time since Robinson joined the Dodgers, and Nuun thought Clemente could return the “laurels” to the league's Black fraternity.Footnote 62 (He didn't, but Frank Robinson won the award a year later.) Clemente and Nuun later teamed up to fight for the integration of hotels and restaurants in Fort Myers, Florida, where the Pirates held spring training. “I am against segregation in any form,” Clemente told the sportswriter, describing how he and other Black Pirates couldn't stay, eat, or travel with their white teammates. “We are members of the Pirates. As such, we should be given the same privileges as all the rest of the players.”Footnote 63 No one, least of all Nuun, questioned the young Puerto Rican's Black bona fides in his first years as a Pirate.

But the questioning did come. Rumors swirled during the 1960 season that Clemente preferred the company of white people. A society note in the Courier implied that the Afro-Puerto Rican “didn't want to be recognized as a Negro.” Clemente had told a reporter that he didn't like how white people in the States treated Black people, including himself. The reporter interpreted him as saying that he didn't like being treated as a Black person. Some readers then took the reporter's paraphrase to mean that Clemente didn't like being Black, that he didn't want to associate with other Black people. Clemente rushed down to the paper's offices on Centre Avenue to “nail that lie.”Footnote 64 Nuun interviewed him and ran the transcript of their conversation as a guest column. It appeared in the phonetic spelling that, Clemente knew, further distanced him from non-Latino Black Pittsburghers, undercutting his argument that he identified with them. “Som’ co-lored people I understand saying Clemente, he not like co-lored people. This is not the truth at all. Look at me, I am not of the white people,” Nuun quoted him as saying. “Thees’ people tell me that I don't like co-lored people. Well, I use this time to tell deeferent. I like myself, so I also like the people who are like me.”Footnote 65 No one would ever mistake him for a white man, Clemente stressed, and only white people would ever meaningfully profit from the division between Black Puerto Ricans and Black mainlanders. But he could never quite shake the rumor that he didn't consider himself Black – that he must be, in the emerging language of clubhouse difference, Latin, a racial buffer between Black ballplayers and their white teammates, Black Pittsburgh and white Pittsburgh.

The national Black press split on the racial status of Afro-Caribbeans in the 1960s. Older sportswriters, some who had themselves played with Black Cubans and Puerto Ricans in the Black leagues and on the islands, tended to identify Afro-Caribbean pros as Black and situate them within the unfolding civil rights struggle. Sheep Jackson of the Cleveland Call and Post celebrated “the rise of the Latin Negroes,” recalling fondly how Black Americans, Afro-Cubans, and Afro-Puerto Ricans had toiled together in the interwar years, bouncing from the Black leagues to the Caribbean and Mexican leagues and barnstorming together. “In those days the games were played on open diamonds mostly, where the old tin-pans were passed among the spectators,” he wrote in 1965, a day before the Marichal–Roseboro incident ignited talk of a rift between Black and Latino major leaguers.Footnote 66 He spoke not of Black and Latin but of a diaspora of athletes who had cobbled livings together under Jim Crow.

Jackie Robinson, who had played a season with the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League before signing with the Dodgers, recognized that Black and Latin American players, while coming from different backgrounds, had common enemies. When Giants manager Alvin Dark, who had banned the speaking of Spanish in the San Francisco clubhouse, explained to a Newsday columnist that his team had struggled because it had “so many Negro and Spanish-speaking players” who lacked the “mental alertness” of their white teammates, Robinson redirected the blame back at Dark.Footnote 67 How can the team's Black and Latino players perform their best, he asked, when they “have to work with a man who has strange cobwebs in his mind about people of color?”Footnote 68 Robinson admitted that he had been shocked by Dark's contribution to a 1964 volume of essays he had coedited on the integration of baseball in which the manager, a Louisiana native, had suggested that white southern coaches “take care” of Black athletes better than northern coaches.Footnote 69 Robinson and his coeditor had titled the volume, without irony, Baseball Has Done It. Dark got fired and then hired and then fired and hired again. He titled his 1980 autobiography When in Doubt, Fire the Manager.

A younger generation of Black sportswriters didn't share Jackson's memories of transnational Black baseball and identified Latin American players, Black and white, as belonging to a third, nonintersecting racial bucket: Latin. When Hank Aaron criticized a reporter in 1968 for naming Clemente rather than him the best right fielder in baseball, the Courier sports page declared, “J. Robinson–Mays Age Dying: The Latins, Whites Take over Baseball.” Noting the prominence of Caribbean players on the paper's own list of “standouts” from the previous season, the column determined that Major League Baseball “finally has applied brakes to the brigade of U.S. tanskins; to compensate for their inescapably devastating triumphs in boxing, basketball, and football.” The writer identified the awarding of the 1965 American League MVP to Afro-Cuban shortstop Zoilo Versalles as a turning point, marking “the first time a tan import had been chosen.”Footnote 70 A few years earlier, Versalles's MVP award would have been heralded as a Black achievement, a continuation of the legacy of Robinson and Mays. Now it stood as a reversal of that legacy.

Sheep Jackson himself, two years after lauding the accomplishments of Clemente and other Afro-Caribbeans, worried that non-Latino Black athletes’ “colored brethren are taking the spotlight [from them], whether they want to admit it or not.”Footnote 71 His attitude toward Latin American players had also changed. In 1965, he remarked that the time in which they “grouped altogether in the clubhouse” had “gone forever.” In 1967, he observed that Latin Americans “stick together in the majors” and that it would “take time for them to mix more with both the white and colored Americans.”Footnote 72 Caribbean players were, in his column, integrated and then self-segregated, Black “Latins” and then just Latins. When Clemente died, Ebony ran a long essay that dwelled on how the Puerto Rican had resented comparisons to Willie Mays, giving the strong impression that he had disliked them not because he wished to be seen as his own ballplayer but because he didn't want to be identified with a Black man.Footnote 73 The Black press and the white press agreed at last that Roberto Clemente did not belong in Black Pittsburgh.

Clemente's career coincided with the transformation of Robinson, who retired in 1956, from hero to legend. Doc Young, the longtime sports editor at the Chicago Defender and the Los Angeles Sentinel, chronicled Robinson and his generation of Black ballplayers and their legacy. In 1953, he published Great Negro Stars and How They Made the Major Leagues, in which he situated Robinson among a host of other pioneering Black athletes, including Minnie Miñoso, the Afro-Cuban outfielder and Black league star who made his MLB debut in 1949, two years after Robinson. Young described theirs as “the era of Jackie Robinson, Minnie Miñoso, et al.”Footnote 74 In 1963, he put out a rough sequel to Great Negro Stars titled Negro Firsts in Sports that elevated the story of Robinson and Branch Rickey to near-mythological status. “Seldom before in history has so vastly important a change in a racial group's fortunes been as directly traceable to one person,” he wrote of Robinson. “To Jackie, also, can be attributed the broadening of opportunity for colored players from such Latin American areas as Santo Domingo, Cuba, Puerto Rico, South America.”Footnote 75 Although he continued to celebrate Miñoso, Young had shifted from an account in which Robinson and Miñoso had struggled together against Jim Crow into one in which Robinson led a wave of Black players into the major leagues, creating the conditions for a subsequent wave of Latin American players. Included in the pages of Negro Firsts, Miñoso retained his status as Black, but younger Afro-Caribbean players didn't make the racial cut. Players who entered the majors before 1955 (Miñoso, Vic Powers) were Black. Players who entered after (Felipe Alou, Orlando Cepeda, Clemente) were Latin. Young might have participated in the racial reshuffling, but he knew who had the strongest interest in separating Black from brown. “Invariably, it's the Caucasian,” he wrote after Marichal struck Roseboro with his bat in 1965, “who screams the loudest.”Footnote 76

Some remembered another Black baseball. In his 1984 autobiography, Amiri Baraka looked back on the Newark Eagles of his youth, where he had felt a sense of belonging not bound to the United States. “Those other Yankees and Giants and Dodgers we followed just to keep up with being in America,” he wrote. “But for the black teams, and for us Newarkers, the Newark Eagles was pure love.” He mocked Major League Baseball's relentless celebrations of Robinson and integration as the fulfillment of an American creed, asking, “Is that what the cry was on those Afric’ shores when the European capitalists and African feudal lords got together and palmed our future[?] ‘WE'RE GOING TO THE BIG LEAGUES!’”Footnote 77 At Ruppert Stadium in Newark's Ironbound neighborhood, he had once, at the urging of his father, introduced himself to the team's left fielder and Clemente's idol, Monte Irvin, who bent down and shook his small hand. The integration of Major League Baseball propelled Irvin to a bigger stage and a World Series title, but it came at the cost of a league in which a Black ballplayer could be more than valuable athletic labor. For Baraka, integration and the resulting dissolution of the Black leagues stood not as a national triumph but a diasporic loss, the alienation of Black people from the pure love of the Newark Eagles, a team he remembered as “being in America” but of something larger. The Eagles of his boyhood belonged to a circuit of Black ball that bound the American South to the Caribbean, Mexico, and Central America, uniting Black Americans with the people who would become, in the racial shift of the 1960s and 1970s, Latin. Walter O'Malley, the chief legal counsel to the Brooklyn Dodgers at the time of integration, later admitted to the sportswriter Roger Kahn that Branch Rickey had chosen Robinson over the Afro-Cuban Silvio García because he could sell “an American boy who had gone to war” as American first and Black second.Footnote 78 He couldn't sell García as the former, and before long, he wouldn't have been able to sell him as the latter either.

Baseball has transformed from the time of the Newark Eagles into a sport with a reputation as white. One recovering baseball fan after another has bemoaned the disappearing Black baseball star, citing statistics suggesting that the proportion of Black players in the majors has dropped from 18 percent in the 1980s to 7 percent in 2021.Footnote 79 (Chris Rock, a lifelong fan of the New York Mets, summarizing most Black Americans’ thoughts on the team in 2015: “What the fuck's a Met?”)Footnote 80 But the numbers don't tell the whole story because more than 30 percent of active players are categorized as Latino, and many Latino players also identify as Black. Black American participation has fallen, and we should ask why. But Black participation hasn't. Why do we measure demographics in Black and brown? Why does Blackness require Americanness? Why does Latinoness supersede Blackness? The construction of new color lines and racial boundaries after civil rights perpetuated what Lisa Lowe describes as the liberal capitalist West's need to disrupt the “intimacies” among the colonized, the enslaved, and the exploited. Race constitutes a remainder or what she calls a “trace” of that violent process of economic assimilation and physical separation.Footnote 81 Sports have often functioned to shroud the traces of colonial intimacies behind new vocabularies of difference. Monte Irvin could see traces of it in San Juan, C. L. R. James on Trinidad, Amiri Baraka at a Newark Eagles game, Roberto Clemente in Pittsburgh's Hill District. There they found not national pastimes but wider intimacies at play.