On November 15, 2019, following almost a month of massive daily demonstrations across Chile, most political parties agreed to initiate an unprecedented constituent process. This process introduced institutional innovations for the Constitutional Convention elections, including gender parity, reserving 17 seats for indigenous individuals, and allowing nonparty candidates to run as independent candidates (Heiss Reference Heiss2021; Suárez-Cao Reference Suárez-Cao2021).

This article examines the distance between society, political parties, and social movements by analyzing the composition of the 2021–2022 Constitutional Convention. I contend that it reflected an intermediation crisis exacerbated by society’s distrust of political parties and their detachment from social movements. The analysis incorporates an original dataset containing the Convention delegates’ background (Rozas-Bugueño Reference Rozas-Bugueño2023), the Social Longitudinal Study of Chile (ELSOC) from the Centre for Social Conflict and Cohesion Studies (COES), and 25 in-depth interviews conducted with Convention delegates and candidates.

SOCIETY, POLITICAL PARTIES, AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS

In contemporary democracies, there is growing distrust in institutions, with a particular focus on political parties. Recent global elections have shown a breakdown of political-party systems, mainly due to the isolation of political elites from society, which leads to political detachment (Sánchez-Cuenca Reference Sánchez-Cuenca2022; Urbinati Reference Urbinati2023).

Extensive research examines the relationship between society and political parties in Chile, primarily focusing on the gap between parties and social movements. Scholars have called this phenomenon the “political autonomization of social movements” (Parra Reference Parra, Navarrete and Tricot2021; Somma and Bargsted Reference Somma, Bargsted, Cox and Castillo2015; Somma and Medel Reference Somma, Medel, Donoso and von Bülow2017). It involves a two-way process in which political parties no longer rely on social movements for political sustainability and movements no longer require party resources to implement their strategies (Somma and Bargsted Reference Somma, Bargsted, Cox and Castillo2015, 228–29).

The autonomization process in Chile began with the return of democracy in 1990. The center-left Concertación governments embraced a governance strategy founded on demobilizing social sectors and promoting economic growth to prevent an authoritarian reversal (Parra Reference Parra, Navarrete and Tricot2021; Tricot Reference Tricot, Navarrete and Tricot2021). According to the specialized literature, most movements have followed an autonomization pattern during the past two decades (Parra Reference Parra, Navarrete and Tricot2021; Somma and Medel Reference Somma, Medel, Donoso and von Bülow2017). Although autonomization is a general trend in Chile, there have been nuances in the process.

The workers’ and human-rights’ movements have historical ties with leftist parties, dating back to before the 1973 coup and during Pinochet’s dictatorship. The Chilean workers’ movement maintains connections with the Christian Democratic, Socialist and Communist parties (CP), which have persisted since the return of democracy. The Unitary Workers’ Center, which is the primary labor organization, has been led by representatives from these parties since 1990. Nonetheless, discontent within the movement has led to the emergence of new workers’ centers, including the National Workers’ Union and the Autonomous Workers’ Center (López Reference López2023). The human-rights’ movement emerged as a response to human-rights abuses during the dictatorship, primarily against left-wing party members. However, it has moved increasingly toward autonomy, maintaining ties mainly with the CP (Parra Reference Parra, Navarrete and Tricot2021).

The autonomization trend has been more evident in various other movements. In the 1990s, the Mapuche movement began distancing from political parties when the Frei government proceeded with a hydroelectric project in the Biobío River, despite opposition from the indigenous group (Somma and Bargsted Reference Somma, Bargsted, Cox and Castillo2015). Another crucial step in the autonomization occurred during the 2006 high school student mobilizations, called the “penguin revolution.” The Bachelet government responded with the General Education Law in 2009. However, the student movement viewed this reform as a political betrayal because it believed that the law did not substantially change the framework inherited from the Pinochet dictatorship (Von Bülow and Bidegain Reference Von Bülow, Bidegain, Almeida and Cordero2015). Following this episode, the CP was the only party with a significant presence in the student movement, but even it began to lose influence after the 2011 student-protest cycle.

With the return of democracy, the feminist movement was divided into two factions: institutional feminists, who engaged in politics, and autonomous feminists, who avoided political ties (Palacios-Valladares Reference Palacios-Valladares2022). This movement was pivotal in pushing for the emergency contraceptive pill (2007) and abortion rights (2013, 2016–2017). In 2018, the movement gained significant momentum in tackling sexual abuse and harassment in universities. Miranda and Roque (Reference Miranda, Roque, Larrondo and Lara2019) highlighted the emergence of performative feminists during the 2018 protests alongside the other two groups. This faction emphasized personal reflection and protests. Regarding the LGBTIQ+ movement, its leading organizations have maintained autonomy from political parties and have cultivated instrumental relationships with legislators (López Reference López2023).

Other movements emerged in the 2010s. Environmental and regional–local movements were successful in garnering support from international organizations to develop their tactics and protest campaigns. These included the Movement for the Defense of Access to Water, Land, and Environmental Protection (MODATIMA) and Patagonia without Dams. This support enabled them to operate independently of political-party resources (López Reference López2023; Parra Reference Parra, Navarrete and Tricot2021). Similarly, the No+AFP movement—a coordinating committee of trade unions and citizens opposed to the individual capitalization pension system—developed its tactics with political autonomy (Rozas and Maillet Reference Rozas-Bugueño and Maillet2019).

However, the distancing between society and political parties is not the sole pivotal aspect of the contemporary crisis in democracy (Sánchez-Cuenca Reference Sánchez-Cuenca2022). Recent worldwide protest movements are marked by spontaneous and leaderless social uprisings in which individuals express discontent without intermediaries and join for various reasons (Urbinati Reference Urbinati2023). Furthermore, these uprisings challenge social organizations characterized by traditional structures and relationships with the establishment. Thus, the current crisis is more an intermediation than a political–institutional crisis (Sánchez-Cuenca Reference Sánchez-Cuenca2022).

The October 2019 Chilean social uprising exhibited these same characteristics: it began spontaneously, lacked clear leadership from social organizations, and was centered on rejecting politics (Somma et al. Reference Somma, Bargsted, Disi and Medel2021). During the uprising, self-organized territorial assemblies known as cabildos emerged to discuss crucial national issues and the demand for constitutional reform, typically excluding party representatives (Tricot Reference Tricot, Navarrete and Tricot2021). This highlights the significance of the territorial aspect in the uprising.

This study argues that the composition of the Constitutional Convention mirrors an intermediation crisis. Many of the Convention delegates had no party affiliation and emerged from social organizations linked to territorial, feminist, and environmental issues, which shows the significance of territorial concerns in the 2019 uprising and the presumed weaker ties of recent protest-associated groups to the political elite.

This study argues that the composition of the Constitutional Convention mirrors an intermediation crisis. Many of the Convention delegates had no party affiliation and emerged from social organizations linked to territorial, feminist, and environmental issues, which shows the significance of territorial concerns in the 2019 uprising and the presumed weaker ties of recent protest-associated groups to the political elite.

THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION’S COMPOSITION: AN INTERMEDIATION-CRISIS EXPRESSION

This section is divided into two parts. The first part uses an original dataset to analyze the background of the Constitutional Convention delegates, including their political affiliations and participation in civic volunteer organizations. This dataset was constructed for the analysis of Rozas, Olivares, and Maillet (Reference Rozas-Bugueño, Olivares and Maillet2022) and complemented with new variables and data for this article. The second part of this section includes an exploratory analysis using data from ELSOC–COES to understand the Convention’s composition. Qualitative data from 25 in-depth interviews with Convention delegates and nonelected candidates also complement the analysis. Further methodological information is available in the online appendix. Figure 1 describes the interviewees’ profiles.

Figure 1 Sample of Interviewees’ Description

The Constitutional Convention featured diverse delegate trajectories. Moving beyond the simplistic classification of militants and independents, I grouped delegates into three categories based on Rozas, Olivares, and Maillet’s (Reference Rozas-Bugueño, Olivares and Maillet2022) typology: (1) partisan militants (33.6%), formal party members; (2) partisan independents (31.6%), independents with historical political ties; and (3) nonpartisan independents (34.8%), those without party affiliations or prior political connections. This typology provides a rigorous framework for analyzing evidence related to the autonomization theory.

Furthermore, it is necessary to investigate the Convention delegates’ participation in civic volunteer organizations to ascertain their association with their political affiliations. I used a dichotomous indicator denoting whether a delegate was a civic volunteer organization member (=1), which is a proxy for involvement in social movements. There is a limitation of this approach: not all civic volunteer organizations are necessarily associated with social movements. Nevertheless, using this criterion as an objective measure became more feasible when comprehensive secondary data on social trajectories were not readily accessible.

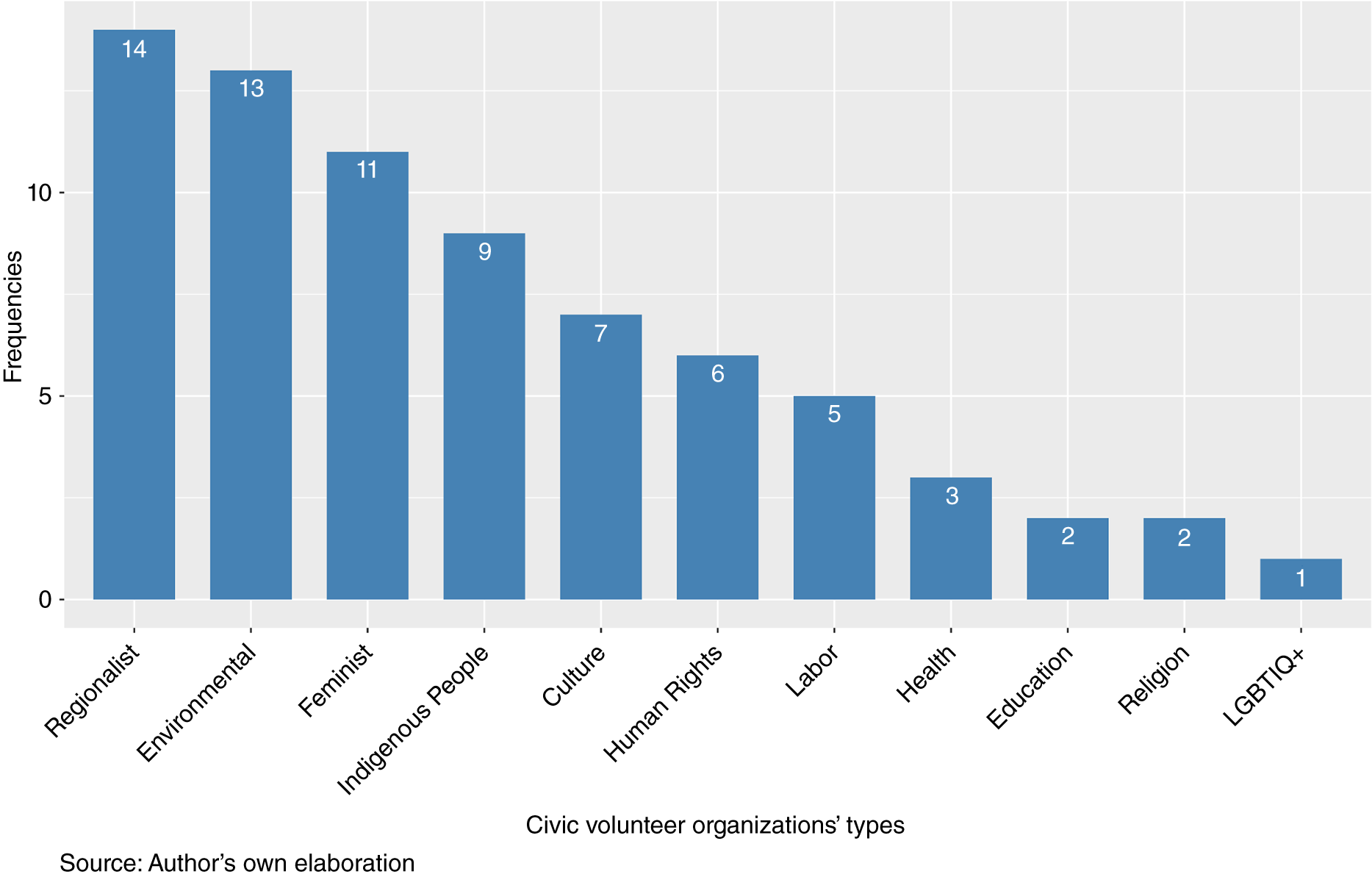

Consequently, 73 delegates (47.1%) originated from civic volunteer organizations. It is important to note that these civic volunteer organizations encompass various types. I adopted the protest-demands categorization used by the COES Observatory of Conflicts to classify the type of organization. Figure 2 illustrates that more than half of these organizations fall under the categories of regionalist (14), environmental (13), and feminist (11).

Figure 2 Delegates’ Civic Volunteer Organization Types

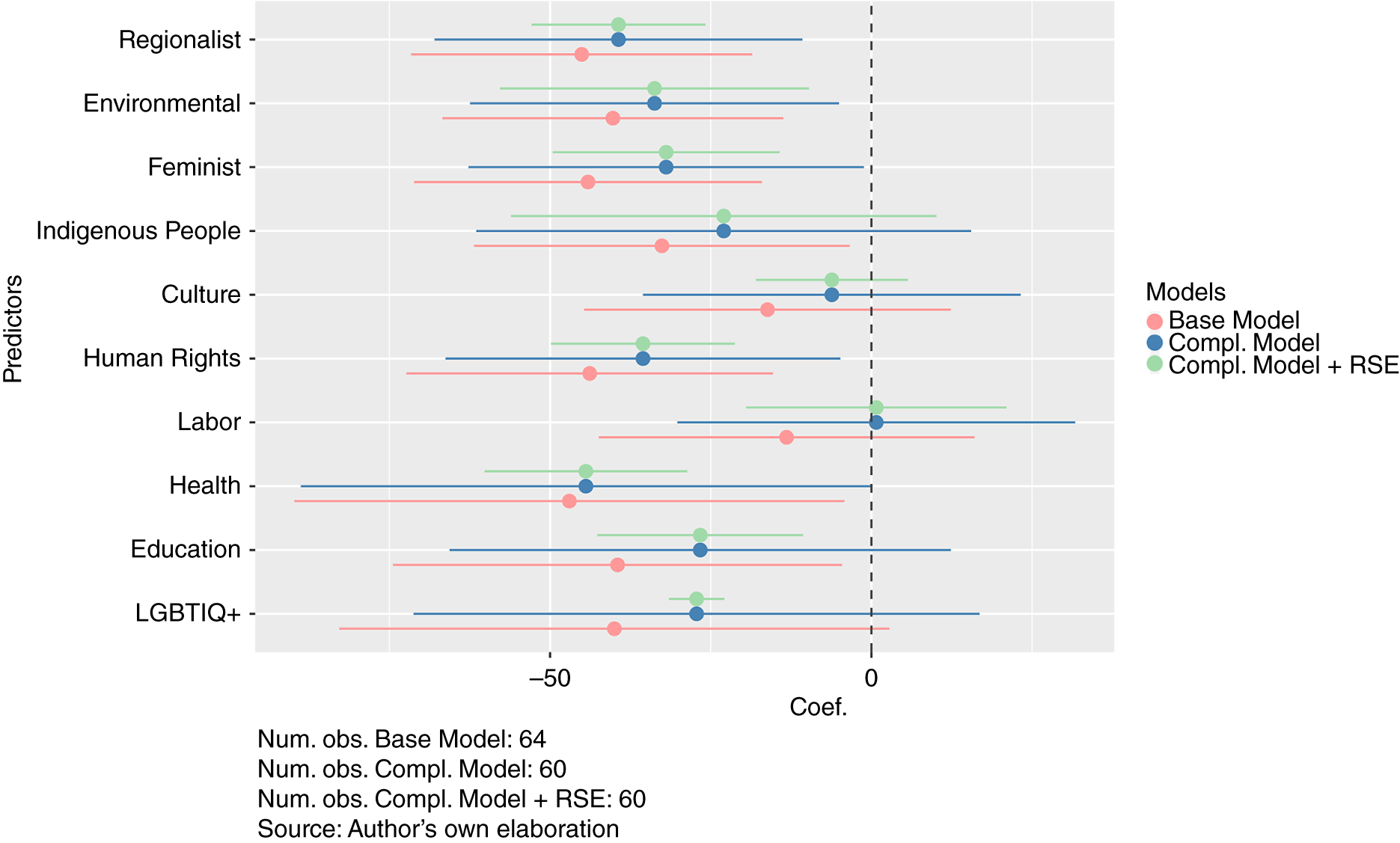

Next, I analyzed the factors influencing Convention delegates’ membership in civic volunteer organizations as well as the age of these organizations. I used linear-probability models to predict membership (figure 3). The base model included independent variables such as political affiliations (with partisan militants as the reference category) and district type (with metropolitan-region districts as the reference category). The complete model added demographic controls including age, gender, education level, and marital status to the base model. The final model incorporated robust standard errors clustered by electoral districts.

Figure 3 Probability Linear Models to Predict Delegates’ Civic Volunteer Organizations Membership (95% Confidence Intervals)

The results reveal that Convention delegates from districts outside of Santiago’s metropolitan region and with a nonpartisan independent profile were more likely to be members of civic volunteer organizations. Therefore, the results highlight the significance of territorial concerns and political detachment in the composition of the Constitutional Convention, in line with theoretical expectations.

Another expectation was that the Convention delegates presented a detachment toward not only political parties but also classical social movements. Therefore, the delegates who were members of organizations likely belonged to newer organizations associated with significant protest cycles around 2019. To investigate this, I constructed linear-regression models to predict the age of civic volunteer organizations. Organization age was computed as the difference between its establishment year and the delegates’ election year (2021), with organization type as the independent variable. I used religious organizations as the reference because this category has the oldest age average. The models in figure 4 replicate previous models: the base model includes the independent variable; the complete model adds demographic controls (matching those in figure 3) along with political affiliations and district type; and the final model incorporates robust standard errors clustered by a delegate’s district type.

Figure 4 Linear Regression Models to Predict the Age of Delegates’ Civic Volunteer Organizations (95% Confidence Intervals)

The results show that, on average, all of the organizations are newer than the religious organizations except the indigenous, cultural, and labor organizations. The effect size highlights more substantial differences in health, regionalist–local, human rights, environmental, and feminist organizations. These findings support the contention that the composition of the Constitutional Convention reflects an intermediation crisis, emphasizing the importance of newer territorial, environmental, and feminist organizations and delegates with limited or weak political affiliations.

The interviews also support these findings, as indicated by the following testimony of an elected woman delegate from an independent list and feminist organization:

There was disillusionment with the political system, stemming from its perceived inefficiency over the past 30 years in Chile…. There was a window for those not affiliated with political parties. Each list member was charged with carrying out a very active citizen campaign in their respective territories. Furthermore, I think what contributed [to the electoral result] was the fact that we are amid the feminist movement’s peak, which undoubtedly holds significant political capital. (Interview 12; June 4, 2023)

However, it is notable that the analysis must be approached with caution due to the limited number of observations and the uneven distribution across the organizations (see figure 2).

I conducted a supplementary analysis using the ELSOC–COES survey, which spans six waves from 2016 to 2022, to assess individual support for various social movements. Fieldwork for the 2019, 2021, and 2022 waves coincided with critical events in the constitutional process: the 2019 fieldwork began during the social upheaval; the 2021 fieldwork took place from January to July, aligning with the Constitutional Convention elections and its subsequent commencement; and the 2022 fieldwork coincided with the referendum on the constitutional proposal. This context allows us to view the survey as representing citizen sentiment.

To gauge support for social movements, I used the following survey question: “Which social movement do you value most?” The responses encompassed various movements; I focused on those related to student, labor, environmental, indigenous, LGBTIQ+, feminist, and pension demands because they aligned with the Convention’s dataset domains. These responses appear in all of the survey waves except for the feminist and No+AFP movements, which have been included only since the 2018 wave. Unfortunately, the list excludes the regionalist–local demands movement. I assessed support through seven binary variables, one for each movement. As figure 5 indicates, nonsupport consistently ranged from 35% to 40% over time, except between 2019 and 2021. Within this context, support for student, labor, and No+AFP movements remained relatively high, with occasional variations.

Figure 5 Individual Support for Social Movements over the Survey’s Waves

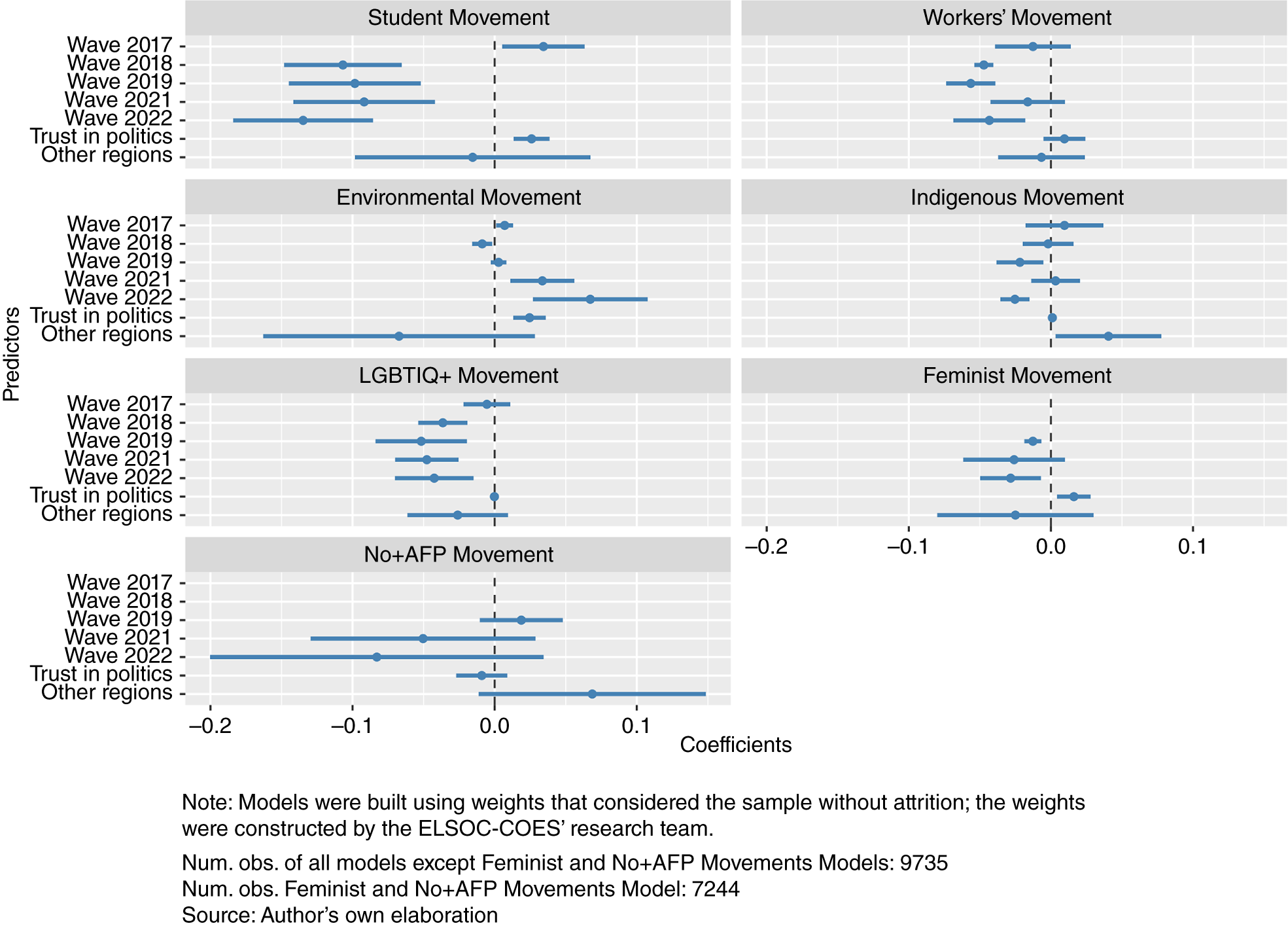

To expand the analysis, I used fixed-effect linear-probability models with robust clustered standard errors by region of residence to predict support for social movements over time. The models included three independent variables: (1) survey waves (the 2016 wave as the reference category, except for No+AFP and feminist movements, which have the 2018 wave as the reference category); (2) a trust index in political institutions (comprising four items related to parliament, the national government, the president, and political parties, with an alpha of 0.79); and (3) a binary variable distinguishing respondents outside of the metropolitan region. Control variables in the models encompassed sex, age, political ideology, and education level.

Figure 6 shows mostly negative wave effects, which reinforces the previous analysis. Notably, the No+AFP movement had no significant effect in 2019, whereas support for the environmental movement increased after 2019. These findings highlight the importance of the “territorial” dimension in the post-uprising political process because environmental issues are closely tied to territorial conflicts such as extractive and energy disputes (López Reference López2023; Somma and Medel Reference Somma, Medel, Donoso and von Bülow2017). The uprising boosted local political engagement (Tricot Reference Tricot, Navarrete and Tricot2021), potentially influencing the constitutional process amid detachment from parties.

Figure 6 Individual Fixed Effect Linear Probability Models to Predict Support for Social Movements (95% Confident Intervals)

The interviews highlight that elected Constitutional Convention delegates perceived the territorial aspect as more crucial to their campaign than their association with the primary protest cycles of the 2010s. For instance, a delegate from an environmental organization noted: “I’m not sure if people saw me as part of the protest decade [the 2010s], but I had done significant territorial work that allowed me [to secure a seat in the Convention]… I have a lot of confidence in my territorial work.” (Interview 20; December 4, 2023)

On the contrary, the 2022 wave reduced support for most social movements, consistent with expectations of assimilation between social movements and institutional politics. Notably, “traditional” movements active since early democracy (i.e., students, workers, LGBTIQ+, and indigenous groups) generally experienced declining support. In contrast, movements closer to the social uprising displayed more resilience: the 2021 and 2022 waves had a positive impact on environmental-movement support; No+AFP support remained unaffected by time; and although the 2022 wave negatively affected feminist movement support, the decline was less pronounced.

The following quote, extracted from an activist for a workers’ movement who did not win election to the Constitutional Convention, illustrates this from his campaign experience:

We also had to acknowledge that actors who had played a significant role in shaping public policy were also subject to these critical perspectives…so it wasn’t surprising that if there was criticism about how institutions were addressing future challenges, this criticism also extended to figures within the realm of labor. (Interview 17; November 4, 2023)

Regarding trust in political institutions, the models show a positive impact on support for student, environmental, and feminist movements, with no effect on other outcomes. This suggests a link between distrust in political institutions and reduced support for specific social movements, indicating a connection between (dis)trust in political institutions and social-movement support.

Finally, predictors linked to respondents’ regions significantly affect support only for the indigenous movement, contrary to expectations. The territorial aspect of the demands apparently had a more crucial role in garnering support for the social movements. The findings concerning the environmental movement underscore the relevance of the territorial component, emphasizing the significance of the territorial dimension within the movement context beyond only physical location.

CONCLUSIONS

This study sheds light on the Chilean constitution-making process. The article provides evidence that the composition of the Constitutional Convention and the process that began with the social uprising reflected an intermediation crisis. The results suggest that the absence of connections to political parties and membership in relatively new organizations—particularly those linked to territorial, environmental, indigenous, and feminist sectors—were the most prominent characteristics among the Convention delegates.

The second part of the analysis highlights that the Constitutional Convention evolved against a backdrop of political disaffection and waning support for social movements. However, the environmental and, to a lesser extent, the feminist and the No+AFP movements exhibited greater resilience. This aligns with the areas of focus on delegates’ civic volunteer organizations that held more influence in shaping the Convention.

These findings show how social movements, in an intermediation-crisis context, can be assimilated as political institutions in terms of mistrust regardless of a historical opportunity. This is exemplified by the experience of the Chilean Constitutional Convention, in which delegates from social movements held a pivotal position. This article opens future research around exploring the role of social movements within the constitutional processes and the implications of the intermediation crisis in political phenomena.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Claudia Heiss and Julieta Suárez-Cao, PS: Political Science & Politics guest editors, and the blinded peer reviewers for their insightful comments and feedback on this article. I also extend thanks to Nicolas Bicchi, Natalia Solís, Toni Rodon, and David Espinoza for their support and revisions of earlier versions of this manuscript. I am grateful for the funding provided by the ANID–Millennium Science Initiative Program–ICS2019_025. I also thank research assistants Catalina Riquelme, Valentina Martínez, and Agustina Cathalifaud for their assistance in coordinating and transcribing in-depth interviews. Finally, I extend my thanks to the 25 interviewees who generously shared their experiences and viewpoints for this article.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/FA6E1V.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096523001130.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declares that there are no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.