The Mughal Empire enjoyed a period of relative prosperity in its first 150 years. Five emperors had ruled much of northern India with relative success. Following the death of Aurangzeb in 1707, the empire entered a period of sharp decline, so much so that 10 emperors sat on the throne in the next 50 years.Footnote 1 This decline resulted from fratricidal civil wars, foreign invasions, and court intrigues. In the picturesque words of Lord Macaulay: ‘A succession of nominal sovereigns sunk in indolence and debauchery sauntered away life in secluded places, chewing bhang, fondling concubines and listening to buffoons.’Footnote 2

After the 1739 invasion of Nadir Shah, the remaining prestige of the Mughals crumbled and many opportunistic powers took advantage of the chaos that followed. The East India Company, having defeated the Mughal army in the battles of Plassey (1757) and Buxar (1764), joined the land-grabbing enterprise. Similarly, the Marathas, led by ambitious generals like Peshwa Bajirao I (d.1740), took the Mughal state by storm. The Sikhs in the Punjab and the Nizam in the Deccan declared independence from Mughal rule, proclaiming sovereignty over their respective territories. The decline of the Mughals and the resultant political strife gave rise to many foreign as well as local powers contending to ‘invest heavily in military innovation as well as professional soldiers’.Footnote 3 Haidar Ali was one such professional soldier and military adventurer who rose through the ranks in the army of Mysore and helped carve an empire for his employer, the Wodeyar raja of Mysore. He later usurped power from the raja after relegating him to a titular head to become the nawab himself.Footnote 4

It was but natural for him to come into conflict with other regional land-grabbing powers in order to protect his recently acquired domain. This gave rise to modernising the military along European lines. He used French officers to conduct military training for his army thus giving his forces the ability to execute ‘well-planned and disciplined military manoeuvres on the battlefield’ that put them at a strategic advantage over his hostile neighbours.Footnote 5 Haidar established a new system, which introduced a defined number of soldiers using European-style flintlocks, within each army division. Haidar also systematically engaged Frenchmen to organise his artillery, arsenal, and workshop.Footnote 6 From using new technologies on the battlefield to ‘constituting a department of Brahmin clerks’Footnote 7 adept at garnering revenue from each part of Mysore's ever-expanding territory without harassing the population, his statesmanship propelled Mysore to become one of South India's strongest powers, stretching from Dharwar in the north to Dindigul in the south and from the Arabian sea in the west to the Ghats which rose from the Carnatic in the east.

In 1782 Tipu Sultan succeeded his father Haidar Ali to the throne of Mysore. Unlike his father, who had risen from humble beginnings and was illiterate,Footnote 8 Tipu Sultan had received the education of a prince, which was immersed in the Indo-Persian culture of the time.Footnote 9 Alongside his studies of Persian, Arabic, Hindustani, and Kannada, he was well versed in Islamic thought as well as horsemanship, archery, and the military arts that he learned from the teachers appointed by his fatherFootnote 10 and through years of experience participating in military campaigns at his father's side.Footnote 11

Tipu Sultan was one of the most creative, innovative, and capable rulers of the pre-colonial period in India. His innovations in areas as varied as agriculture, irrigation, as well as social reforms were unparalleled for Indian rulers of that time. Tactically, the Mysorean army was as advanced as the military of the East India Company.Footnote 12 Tipu also excelled in taking the best of European military methods and combining them with the best of Mysorean military traditions.

The Mysorean army's flintlock rifles and field cannon, which were ‘based on the latest European designs as well as specialization in gun casting and metallurgy’, stood it in good stead in the many conflicts with its neighbours and the English.Footnote 13 So good was his military manufacturing that some of his guns, made in the factories across Mysore, were thought to be of better quality than the EnglishFootnote 14 and FrenchFootnote 15 models. The rockets that his men used with chilling effect in the Anglo-Mysore wars were later taken to England and the technology was adapted for use in the British Congreve rockets that saw action in the Napoleonic wars, with good success.Footnote 16

Tipu Sultan's redeeming qualities in the spirit of enquiry, his adaptability to modern European methods of military drill, and his independent mind prompted him to order the writing of military manuals for his army, titled fath-ul-mujahideen, which covered topics as varied as military troop formations and war tactics to marching songs, and so on.Footnote 17 At around the same time he also commissioned several other governmental decrees on statecraft as well as military affairs. This article discusses one such treatise in manuscript, which was an outcome of the sarkar-i-khudadad or khudadad sarkar that signifies ‘God-given government’, as Tipu Sultan called Mysore, as it attempted to take its place as pre-modern India's most advanced state.

Our objective in studying the manuscript

Kate Brittlebank in her seminal work Tipu Sultan's Search for Legitimacy mentions that literature on the devolution of power in the eighteenth century has ‘concentrated mainly on social political, economic and administrative processes and less on religious, ritual and symbolic practice’.Footnote 18 The mechanics of establishing the legitimacy of the ruler via statecraft has generally not been explored in depth. This article delves into the ritual and symbolic processes involved in the establishment and assertion of legitimacy by Tipu Sultan in Mysore which have been gathered from a reading of the Risala-i-Padakah through the award of medals to his civil and military personnel.

Michael Soracoe writes about how the Anglo-Mysore Wars were portrayed by the British not as expansionist wars undertaken to acquire more wealth and territory in southern India, but as a war of liberation designed to unshackle the people of Mysore from their horrible ruler.Footnote 19 He writes:

In addition to the endless association of ‘tyranny and despotism’ with Tipu, the Sultan was also accused of being a ‘faithless ruler’ who could not be trusted. Tipu was said to break treaties whenever it suited him, making it impossible to honour his word. Despotism was very frequently associated by the English with Indian rulers like Tipu Sultan. The notion of ‘Oriental despotism’ was increasingly invoked by Europeans as an explanation for conquest, arguing that this tyrannical system of rule had impoverished the region and brought about the faltering state of affairs.Footnote 20

Alexander Beatson provided an extended sketch of Tipu's character at the end of his narrative about the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War, describing Tipu as a weak ruler completely incapable of making decisions and untrustworthy due to his constantly changing tyrannical whims. Beatson writes:

He paid no respect to rank or position, and undermined the administration of Mysore. The whole of his conduct therefore ‘proves him to have been a weak, headstrong, and tyrannical prince…totally unequal to the government of a kingdom, which had been usurped by the hardiness, intrigue, and talents of his father’.Footnote 21

Tipu Sultan was thus portrayed as lacking all of the character traits that were required of an ideal ruler. His supposed flaws were used to justify the Company's invasion and annexation of Mysorean territory in order to replace the corrupt native political system with superior British institutions.

Scholars like Kate Brittlebank have gone further to show how reductionist and far-fetched such colonial views on Tipu's character were. She asserts that in order to justify their land-grabbing expansionist policy in India, the East India Company propagandists painted Tipu as a bloodthirsty despot.Footnote 22 This article further strengthens such modern assessments of Tipu's achievements and character. It sets out to challenge the allegations of Tipu Sultan being ‘faithless, paying no respect to rank or position and being unfit to rule’ by examining his actions in the context of his order to design and award medals to different ranks in Mysore's civil and military administration, the first pre-modern Indian state to do so.

This article opens up an entirely new chapter in the study of Indian history as well as that of medals. It will also be of advantage in learning about the different departments that comprised the Mysorean army.

The zabita as an administrative manual

A common term found in this manuscript is ‘zabita’. The practice of putting to paper rules and regulations that governed the administration of a state is called the ‘zawabit’ or ‘zabita’. This practice was not one instituted by Tipu Sultan but was part of a continuing Islamic tradition. The fourteenth-century Indian historian Ziya-al Din Barani defined zawabit as ‘a rule of action which a king imposes as an obligatory duty on himself for realizing the welfare of the state and from which he never deviates’. While Barani was adamant that the zawabit framed by the sultan should not violate the provisions of Islamic sharia law, he also asserts that the zawabit were not based on any religious text or their interpretation by the ulema but were legislated by the king solely on the basis of his understanding of what was good for his kingdom.Footnote 23 Furthermore, from a Hindu viewpoint, the practice of rulers commissioning manuals in politics, warfare, economics, and horsemanship, among others, was a practice that dated back to ancient times.Footnote 24 Thus, Tipu Sultan was walking on the same path as the rulers who had preceded him in other parts of India.

Having earned a reputation for strong leadership among his subjects and contemporary rulers, in the words of his biographer: ‘He also formed regulations on every subject and for every department depending on his government, every article of which was separately written with his own hand.’Footnote 25 Copies of such manuscripts were made and distributed throughout the kingdom.Footnote 26

Tipu Sultan's library and the Risala-i-Padakah manuscript

The defeat and death of Tipu Sultan on 4 May 1799 in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War saw Mysore's capital city Seringapatam being sacked and subjected to indiscriminate pillage by the victorious English army and their allies. In the course of this pillage, Tipu's magnificent library was also discovered in the palace. In his work on how Tipu used the library to legitimise his rule, which, after defeating him, the East India Company also used for a similar purpose, Joshua Ehrlich writes:

The library's accommodation resembled the palace's private treasure houses rather than its public audience halls which signified that Tipu Sultan envisioned the library, on one level, as a store of art and knowledge bound up with the person and power of himself.Footnote 27

The argument that much of Tipu's library was acquired through plunder is unjust. It contained many original works, the collection of which was personally supervised by the sultan, including this manuscript. While books were acquired by different means in those days, including plunder, exchange of gifts, as well as purchasing, one cannot assume that most manuscripts in the sultan's library were acquired through plunder, as today we know that there remains no more than a quarter of the 3,000–4,000 manuscripts that this library once contained which are dispersed in collections worldwide.Footnote 28

British officers decided to send the major part of the library to the Court of Directors of the East India Company in London; a minor portion of the collection was to be kept in Bombay and Madras and the rest donated to the Asiatic Society of Bengal in Calcutta, which had been established by Sir William Jones in 1784.Footnote 29 The manuscript we chose for this study is from the part sent to the Asiatic Society of Bengal.

An overview of the manuscript

The manuscript labelled with the serial number 1640 and titled Risala-i-Padakah in the Asiatic Library of Calcutta is in readable condition. It has 83 folios of European-manufactured paper measuring 20 x 14 cm with Persian text in Nastaliq script. The printed catalogue available at the library has this to say about the manuscript:

A guide book to the great variety of differently shaped medals, decorations, etc. introduced by Tipu, undoubtedly in imitation of the insignia of the Europeans. There are also descriptions of a great number of flag-tope, seals, brands, etc. with drawings illustrating their forms. At the end there is an appendix on special flags carried on elephants.Footnote 30

In his catalogue of manuscripts from the library of Tipu Sultan, Charles Stewart also mentions the presence of this manuscript in the Asiatic Society of Bengal collection.Footnote 31

The folios contain sketches of decorations, seals, horse brands, flag standards, and flags, arranged in groups according to their types. Out of 166 folios that make up the manuscript, only 70 of them have any entries, with the remaining folios left blank.Footnote 32 Each folio has a sketch of one or several of these objects, along a description of each object. Of the 70 folios with text and images on them, 39 folios (nos. 1b–20a) detail the design of padakah (medals); 12 folios (nos. 26b–32a) detail the design of mohur (seals); two folios (nos. 32b and 33a) detail the design of dagh (horse brandings); four folios (nos. 74b–76a) detail the design of alam (flag standards), and 13 (nos. 76b–82b) detail the design of alam (flags).

There is no mention of the term ‘risala’ anywhere in the manuscript. This leads the authors to believe that the title of this manuscript (Risala-i-Padakah) in the Asiatic Society, Calcutta, catalogue was given by one of its early reviewers who observed that this manuscript was in the form of a booklet (risala in Persian) with the initial folios all detailing the design of padakah (medals).

The folios and contents

The first folio (marked in pencil as number 1b by a later hand) (see Figure 1) is very important in that it provides us with an introduction to as well as the provenance of this manuscript. The folio has a heading which reads: ‘hukumnama zabita-i- padak hai mursa wa neem mursa wa saada tilai wa naqrai sarkar-i- ahmadi’ (Decree—rules regarding medals inlaid, partially inlaid, plain gold and silver for the ahmadi Footnote 33 government).

Figure 1. Folios 1b and 2a of the manuscript. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

Hence the heading in folio 1b makes it clear that this manuscript is a hukumnama (decree). A clue as to its date can be found on the same folio of the manuscript which bears the official sealFootnote 34 of Tipu Sultan himself (see Figure 2). It reads ‘Tipu Sulṭan, 5121’ (i.e. 1215 mawludi era, circa 1787/1788).Footnote 35 It is believed that Tipu had issued his set of regulations for different departments by 1787–1788.Footnote 36

Figure 2. The personal seal of Tipu Sultan dated 1215 Muhammadi or 1787 ad affixed to the top centre of folio 1b of the manuscript. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

The first folio, again, has another mark on the top-right side of the page which looks like a signature in a different hand. This appears to be written in a different style using different pen-strokes from the rest of the text in the manuscript. This reads ‘bismillah al- rahman al- rahim’ or ‘In the name of Allah the beneficent and merciful’ and is found on many manuscriptsFootnote 37 in Tipu Sultan's library as well as on many letters emanating from the capital in Seringapatam. It is most likely that this signature was transcribed by the sultan himself. The presence of the personal seal and signature of Tipu Sultan demonstrates that he would have personally commissioned, approved, and handled this manuscript. The text in this folio goes on to explain that this manuscript describes the different types of medals and also mentions those that are fully inlaid (mursa), partially inlaid (neem mursa), and gold and silver.

It is curious that while we know that the manuscript contains information about different kinds of state insignia like medals, flags, standards, seals, and horse brandings, the introduction to the manuscript on folio 1b only mentions padakah (medals). It is possible that this hukumnama may have originally been intended only for medals awarded by the sarkar and that later details about the flags, standards, seals, and horse brandings were added to it. However, the scope of this article will be limited to studying Tipu Sultan's instructions regarding the medals.

The inlaid medals

Folio 1b states that the aftab numa Footnote 38 medal is to be awarded to the asaf taran, asaf yam, and the asaf ghabra.Footnote 39 The design of the larger padak kalan asaf taran medal is described as follows:

The sun-shaped medal will have 14 rays each of one angusht and two taha length and 12 taha width emanating from it. Inside each ray will be a diamond studded bubri Footnote 40 (tiger stripe) ten taha long and four taha wide. Around each diamond bubri, the four taha wide outer lining of the ray is inlaid with rubies. Around the asadullahi monogram in the centre is a lining of three angusht and two taha width. In this lining are 23 emerald inlaid bubris of 12 taha length and four taha in width. The asadullahi monogram in the centre also has a large ruby in the middle. The medal is worn with a suspension that is tiger face shaped with a ruby inlaid tongue attached to a gold chain of eight girah Footnote 41 length.

Folio 2a contains the design of the smaller medal for the asaf taran. The padak kuchaq asaf taran is described as follows:

The (smaller) medal has 16 rays each eight taha long and six taha wide. In the middle of each ray is a diamond inlaid bubri six taha long and two taha wide. Around each diamond bubris, the two taha wide outer lining of the ray is inlaid with rubies. Around the centre of the medal is a lining of two angusht width. In this lining are 12 diamond inlaid bubris of ten taha length and four taha in width. The centre has a large ruby in the middle of ten taha circumference. The length and width of the medal should be three angusht all around. There should be two golden hooks at the back of the medal for the chain to pass.

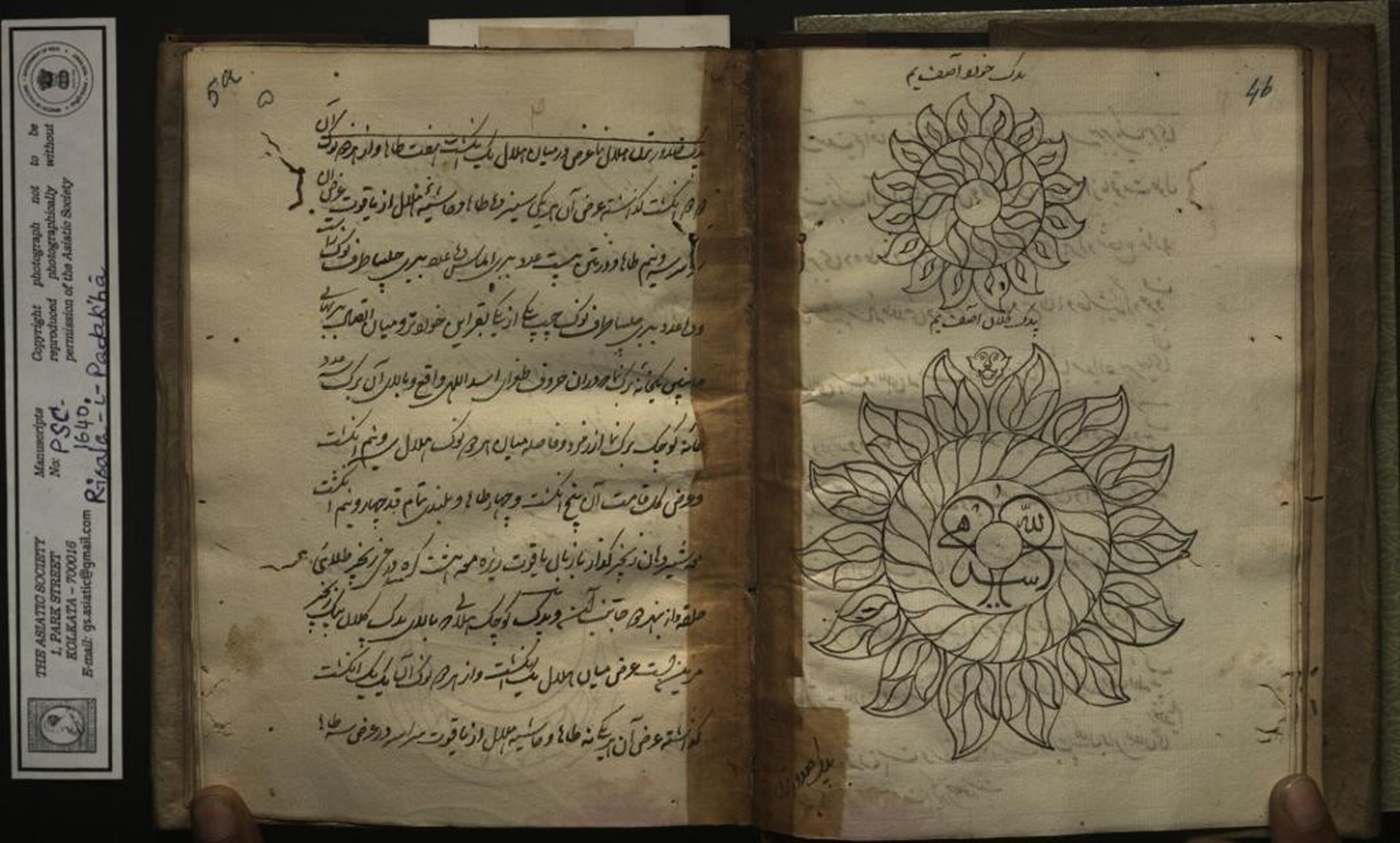

Folio 2b has the sketches of the large and small padak asaf taran medals. Folio 3a contains the details of the larger aftab numa medal for the asaf ghabra (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. The padak kuchaq asaf taran and padak kalan asaf taran (folio 2b and folio 3a) from the manuscript. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society Calcutta.

The padak kalan asaf ghabra (large medal for asaf ghabra) is described as follows:

The medal has 14 sun-rays within each of which, there are two diamond inlaid bubris. The length of each bubri is ten taha and the width is three taha. The two taha thick lining around these bubris is emerald inlaid. There are 23 bubris around the monogram asadullahi in the middle of the medal which has a large emerald inlaid in the centre.

The folio further continues with the description of the smaller asaf ghabra medal, the padak kuchaq asaf ghabra (small medal for asaf ghabra), which is described as follows:

The smaller medal has one diamond inlaid bubri inside each ray. And the lining around the ray is emerald inlaid with 12 ruby inlaid bubris in the space around the lining. A large emerald is inlaid in the middle of the medal.

Folio 4a (see Figure 4) contains the description of the large and small medals for the asaf yam. The padak kalan asaf yam (small medal for asaf yam) is described as follows:

The sun-shaped medal will have 14 rays emanating and inside each ray will be three bubris. Of the three bubris one on the top is tipped with a diamond and the other two with rubies. The length of each bubri will be ten taha and the width will be three taha. Each ray will have gold strip one and a half taha thick around it. There is a large ruby inlaid monogram in the centre reading asadullahi, around which are 23 bubris inlaid with emeralds.

Figure 4. The padak kuchaq asaf ghabra and padak kalan asaf ghabra (folio 3b and folio 4a) from the manuscript. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

The same folio 4a has the description of the padak kalan asaf yam (smaller medal for the asaf yam) that is described as follows:

Inside each ray there is a diamond inlaid bubri and the lining around the ray is ruby inlaid and in the space around the gem inlaid in the middle, there are 12 emerald inlaid bubris and the gem inlaid in the middle is a large ruby.

Folio 5a (see Figure 5) contains the description of the large and small hilal numa Footnote 42 medals which were to be awarded to the sudur taran, sudur ghabra, and sudur yam.Footnote 43 The text describes the construction of the padak kalan hilal numa sudur taran (large crescent shaped medal for sudur taran) as follows:

The crescent which is one angusht (finger) and seven taha wide in the middle has passages of 13 taha width at the tips for the chain of 16 girah length. The distance between the 2 tips is three and a half angusht and the height of the medal is four and a half angusht. There are 20 diamonds inlaid bubris running along the entire medal within a gold lined border of width three and a half taha, inlaid with rubies. The monogram ‘assadullahi’ is placed between the bubris at the middle of the medal along with a leaf shaped pearl and 3 similar shaped emeralds. On the middle upper edge of the medal is a suspender in the shape of a tiger head with a ruby inlaid tongue.

Figure 5. The padak kuchaq asaf yam and padak kalan asaf yam (folio 4b and folio 5a) from the manuscript. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

Folios 5a and 5b go on to describe the design of the small hilal numa medal. The padak kuchaq hilal sudur taran is described as follows:

The smaller crescent shape medal has a width at the middle of the crescent of one angusht and on both tips there are hook passages of one angusht and the width of each hook is nine taha. The ruby inlaid lining around the crescent is three taha wide. The main space (on the crescent) has 12 bubris with six towards the right tip and six towards the left tip. In the middle of bubris there is an asadullahi monogram. Two gold hooks for a chain passageFootnote 44 are attached behind the medal. Height of the medal is two and a half angusht and the width is three angusht. The distance between the two tips is two angusht.

The folio also has the details of the large and small hilal numa medals for the sudur ghabra and sudur yam which have similar designs to the sudur taran except that the ruby inlaid lining is substituted with emeralds. Folio 6a has the sketch of the padak kalan hilal sudur taran.

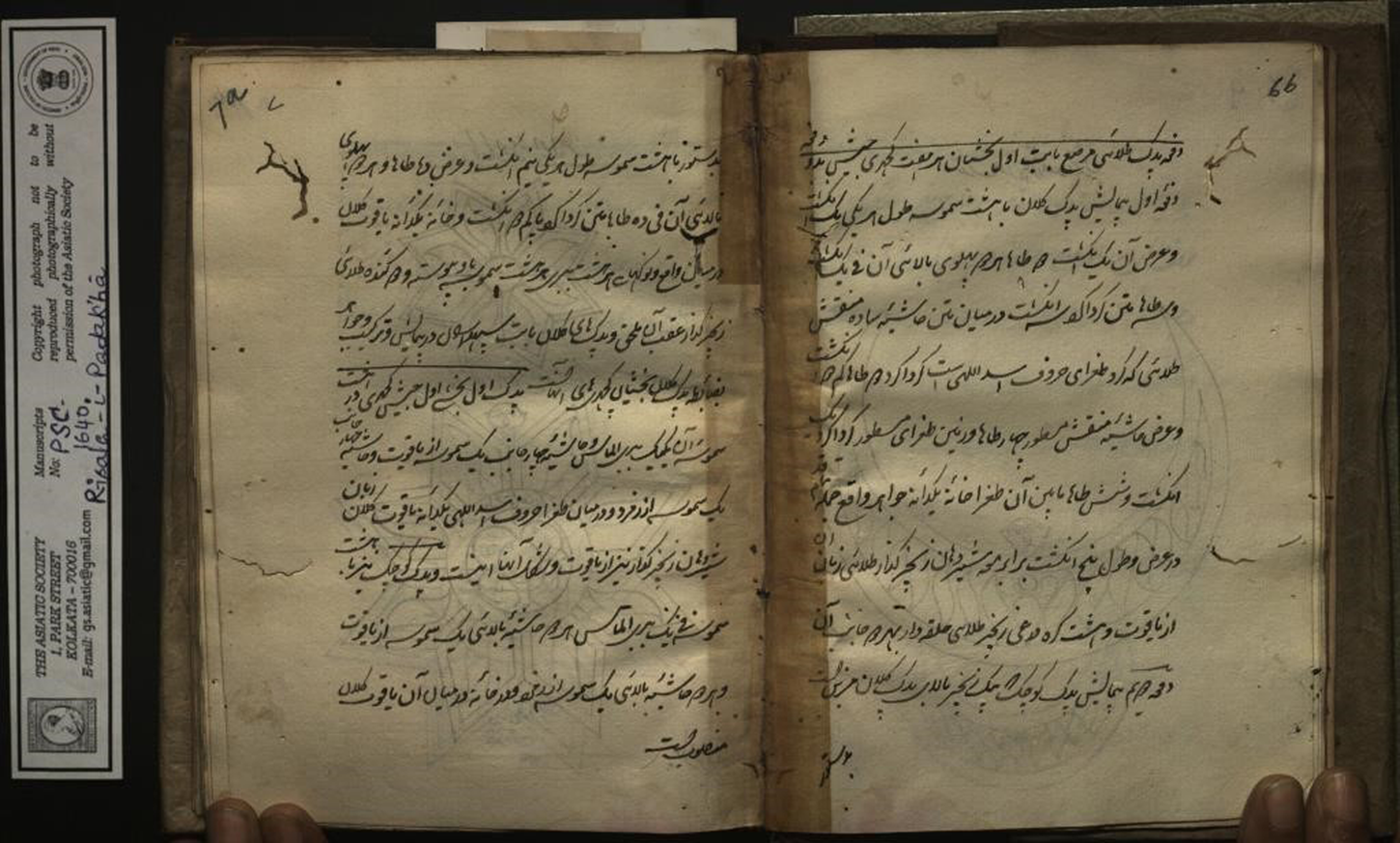

Folios 6b and 7a (see Figure 7) contain the description of the large and small hasht-samosa (eight triangle star shaped) medals which are mentioned here in kalan (large) and kuchaq (small) sizes and to be awarded to the individuals holding the position of awwal bakhshi (commander-in-chiefs) of the seven jaish kacheri (infantry brigades)Footnote 45 that are mentioned here: awwal jaish kacheri, doem jaish kacheri, soem jaish kacheri, chaharum jaish kacheri, panjum jaish kacheri, shashum jaish kacheri, and haftum jaish kacheri.Footnote 46

Figure 6. The padak kuchaq hilal sudur taran (folio 5b) and padak kalan hilal sudur taran (folio 6a) from the manuscript. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society Calcutta.

Figure 7. Folios 6b and 7a from the manuscript. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

The text describes the design of the large medal as follows:

This medal is of the hasht-samosa type with eight triangles (samosa) of one angusht length and one angusht, two taha width with one angusht, three taha space between each of them emerging from a central circular space with a large ruby inlaid and the monogram asadullahi which is four taha wide inscribed. The chain would pass through the tiger head suspension for the kalan medal.

The text specifies the design of the small medal which is worn with a chain above the larger medal as follows:

This medal is of the hasht-samosa type with eight triangles (samosa) of half angusht length and 10 taha width with 10 taha space between each of them, emerging from a central circular space with a large ruby inlaid. Each samosa has a diamond tipped bubri inside and the medal has two rings attached at the back for the passage of the chain.

A very important point mentioned here is that the size and the design of all the hasht samosa medals are based upon the size and the design of the very first example given. This is clearly evident from the following words found in this textual description: ‘Paymaish wa tarkeeb-e-shakal wa ghayrah bazaabta-i awwal kachehrist…’ which may be translated as ‘The size and the appearance etc. are to follow the pattern of the awwal kachehri (medal)’.

Folio 7b (see Figure 8) has the sketches of the smaller padak kuchaq awwal bakshi awwal kachehri and the larger padak kalan awwal bakshi awwal kachehri medals. Folio 8a (see Figure 8) includes both the sketch and the description of the larger awwal bakhshi doem jaish kacheri medal. This medal has two diamond inlaid bubris (in each triangle) and the rest of the dimensions and appearance are the same as the smaller awwal kacheri medals.

Figure 8. Folios 7b and 8a from the manuscript. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society Calcutta.

Folio 8b (see Figure 9) describes the medal for the awwal bakhshi soem jaish kachehri and folio 9a (see Figure 9) describes the medal for the awwal bakhshi chaharum jaish kachehri. These medals have three and four diamond inlaid bubris (in each triangle) and the rest of the dimensions and appearances are the same as the awwal kacheri medals.

Figure 9. Folios 8b and 9a from the manuscript. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society Calcutta.

Folios 9b and 10a (see Figure 10) describe the medals for the awwal bakhshi soem panjum kachehri and the awwal bakhshi shashum jaish kachehri respectively. These medals have five and six diamond inlaid bubris (in each triangle) and the rest of the dimensions and appearances are the same as the awwal kacheri medals.

Figure 10. Folios 9b and 10a from the manuscript. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

Folio 10b (see Figure 11) describes the medal for the awwal bakhshi soem haftam kachehri which have seven diamond inlaid bubris (in each triangle) with the rest of the dimensions and appearances the same as the awwal kacheri medal. It should be noted that the dimensions and design of the smaller medal for the awwal bakshi of each of these kacheris will be similar to that of the first kind of medal described, that for the awwal bakshi of the awwal kacheri.

Figure 11. Folios 10b and 11a from the manuscript. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

Folio 11a (see Figure 11) mentions that similar types of inlaid hasht-samosa medals were awarded to individuals from the askar sawaran kacheri (horse-mounted brigade)Footnote 47 holding the following positions: awwal bakhshi awwal askar kachehri (commander-in-chief of the first horse-mounted brigade); awwal bakhshi doem askar kachehri (commander-in-chief of the second horse-mounted brigade); awwal bakhshi soem askar kachehri (commander-in-chief of the third horse-mounted brigade); awwal bakhshi chaharum askar kachehri (commander-in-chief of the fourth horse-mounted brigade); and awwal bakhshi panjum askar kachehri (commander-in-chief of the fifth horse-mounted brigade). All of the these medals are inlaid and are hasht-samosa (eight triangles) type. This folio describes the design of the medals for the awwal bakshi awwal sawaran kacheri (i.e. the first bakshi of the first cavalry brigade) which is the first example of this type. The text in Persian describes these medals as follows:

They have eight triangular edges giving the appearance of a star to them. The medal is inlaid with diamonds, rubies and emeralds and has gem encrusted bubris along the edges. It would be worn using a golden chain through a small tiger head with a ruby inlaid tongue attached to the upper edge of the medal. There is a large ruby in the centre of the medal, surrounded by the monogram ‘assadullahi’.

A smaller medal that is designed differently accompanies the larger medal.

Folio 11b has the sketch for the smaller and larger medal for the awwal bakhshi awwal askar kachehri while folio 12a goes on to describe and sketch the larger medal for the awwal bakhshi doem askar kachehri (see Figure 12). Folio 12b has the details of the design and sketch for the larger medal for the awwal bakhshi soem askar kachehri, while folio 13a has the description and sketch of the larger medal for the awwal bakhshi chaharam askar kachehri (see Figure 13).

Figure 12. Small and large padak awwal bakhshi awwal askar kachehri (folio 11b) and large padak awwal bakhshi doem askar kachehri (folio 12a) from the manuscript. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

Figure 13. Large padak awwal bakhshi soem askar kachehri (folio 12b) and large padak awwal bakhshi chaharam askar kachehri (folio 13a) from the manuscript. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

Folio 13b (see Figure 14) has the details of the design and sketch for the larger medal for the awwal bakhshi soem panjam kachehri. The designs of these medals are very similar; again, we find this sentence across these folios: paymaish wa tarkeeb-e-shakal wa-ghayrah ba-zaabta-i-awwal kachehrist, which means that the size and the design of the medals in this category are based upon the size and the design of the very first example of each type which are the medals for the awwal bakshi of the awwal kachehri. Folio 14a (see Figure 14) contains details of the inlaid tiger-nail shaped (nakhun sher) medals which were awarded to individuals holding the positions of sipahdar asadullahi kacheri (commandant of the Asadullah brigade) and sipahdar ahmadi kacheri (commandant of the Ahmadi brigade).Footnote 48 The design of medals for the bakshis of these kacheris has been provided in Figure 6.

Figure 14. Large padak awwal bakhshi panjam askar kachehri (folios 13b and 14a) from the manuscript. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

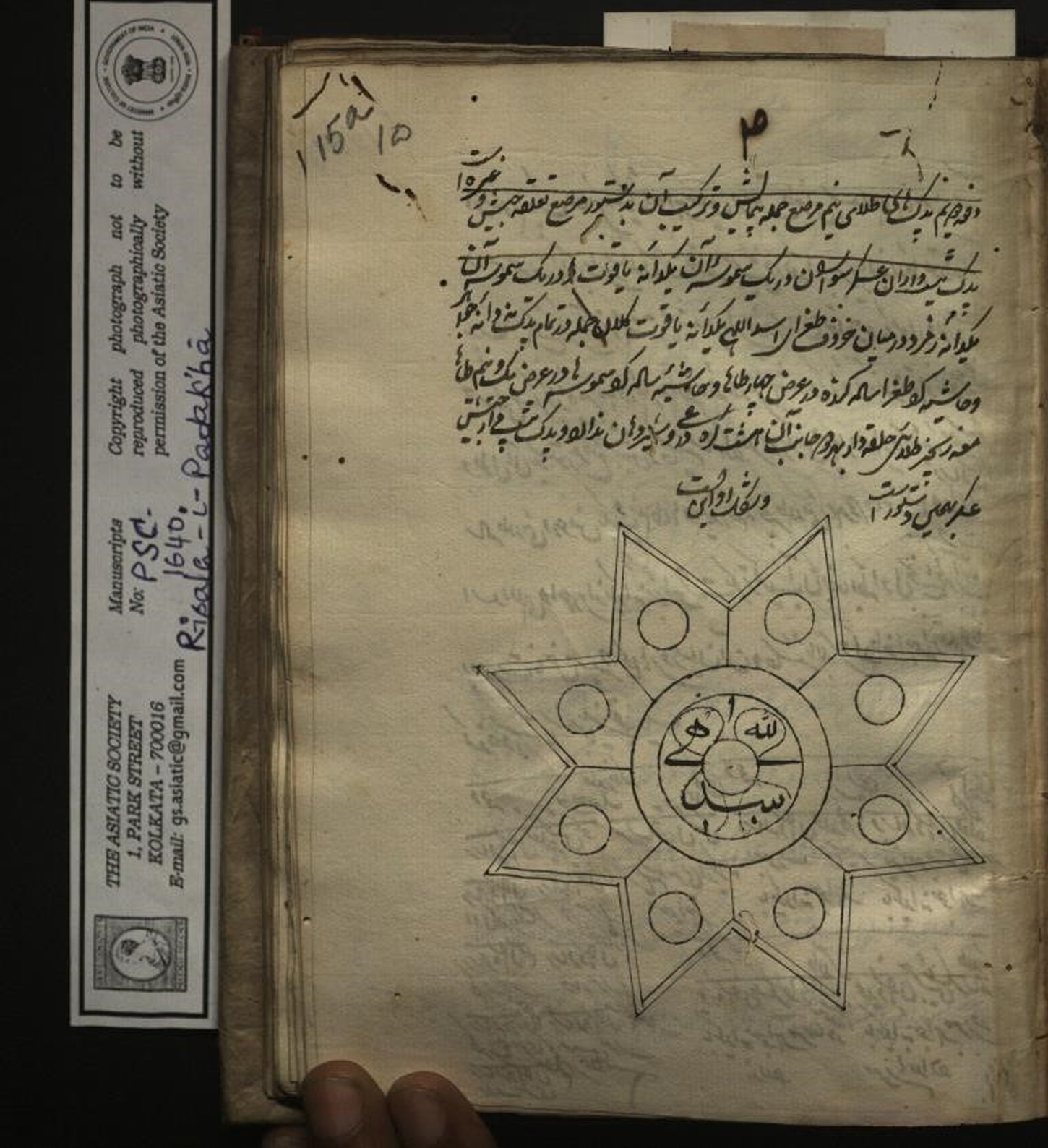

The Persian text on folio 14a describes the design of the larger medal as follows:

There are eight tiger nail shaped edges of one angusht—four taha length and one angusht width. A small emerald of twelve taha length and 7 taha width will be inlaid in the middle of each nail which will have an outer lining that is four taha wide inlaid with rubies. The centre of the medal will have a large emerald with the monogram ‘assadullahi’, four taha wide inlaid with rubies.

The description of the smaller tiger-nail medal follows and one medal is prescribed for the sipah-daraan assadullahi and ahmadi as well.

Note:

After the title, the manuscript provides the names, illustrations, and the descriptions of what it terms ‘mursa’ (inlaid)—these are a group of medals made in gold and encrusted (inlaid) with precious gems such as diamonds, rubies, and emeralds. The use of gemstones, in addition to being a demonstration of wealth and prestige, was also perceived to have magical, talismanic qualities by Hindus and Muslims alike.Footnote 49

In India, the jewel is not merely bodily adornment. It functions as an icon that is associated with almost every aspect of an individual's personality, their social status, caste, community, and religion. When an ornament is worn, there is an automatic association of ideas between the jewel, the symbolism inherent in each ornament, and the reaction of the observer from the same cultural milieu.Footnote 50

All the inlaid medals came in four shapes and two sizes—small and large. These medals were awarded to individuals holding the following positions: asaf taran—the governor of the hill regions; asaf ghabra—the governor of the flat land; asaf yam—the governor of the coastal regions. Each Mysorean province was in the charge of an asaf or civil governor. Tipu had given a new nomenclature to different geographical areas of Mysore, calling the coast districts the ‘yam suba’, the hilly areas the ‘taran suba’, and the plain country the ‘ghabra suba’.Footnote 51 The shape of the medal (aftaab for the sun) had a special symbolism here. While the Hindus worshipped the sun, it was also one of the six dynastic insignia of the Mughals since their arrival in India. Tipu adopted the sun with radiating rays in his banner, which was purple silk, with a central sun, consisting of stripes of green at the corners and bordered with gold in a circle.Footnote 52 When referring to himself, the most common epithet he and others used was huzur-i-purnur which translates as ‘resplendent presence’ or ‘full of light’.Footnote 53 Presenting his governors with a sun-shaped medal would have been a signal of his confidence in his governors who also now owed fidelity to Mysore as well as the Sultan.

Bubri from ‘bubur’ (Persian for lion/tiger) was the typical ‘S’-shaped motif, hollow at the centre and re-curved at the ends denoting a tiger stripe.Footnote 54 Tipu Sultan surrounded himself with images of the tiger and adopted the motif as an emblem to convey ‘both to his subjects and to his enemies the awesome power of the tiger that was the most powerful and feared animal in South India. The presence of the bubri design on his medals would also have been a potent way to transmit some of this power to his men whose chests they adorned.

The taha is an ancient unit of measurement in Karnataka and 16 tahas made an angusht. Angusht means thumb, and scales from the eighteenth century show that the width of a thumb was equal to three centimetres and three millimetres. So a taha would have measured about two millimetres in Tipu's time.Footnote 55

Asadullahi in Arabic is an attribute that literally means ‘the Lion of God’, which in the Mysorean context is to be taken as ‘Tiger of God’. This title was used for Imam Ali who was a warrior as well as the son-in-law of the Prophet Mohammad and thus a powerful symbol of valour for Tipu Sultan as well as the bearer of these medals.Footnote 56 Tipu held Ali in great veneration, which would have been on account of Imam Ali's attribute as an unbeaten warrior of 72 battles with his two-edged sword as well as his esoteric association with Sufism.Footnote 57 The appearance of this monogram on the Mysore medals is testament to the Sultan, equating each of his favoured men with a hero no less than Imam Ali himself. The crescent-shaped (hilal numa) medals conformed to a central icon in Islamic tradition and art—the crescent moon (hilal). The crescent is indeed a very widespread motif in Islamic iconography. The device seems to have entered Islam via the Seljuk Turks who dominated Anatolia in the twelfth century, and was widely used by their successors, the Ottoman Turks, whose influence on the states of the Deccan was significant.Footnote 58 Tipu Sultan, who inherited the same traditions, used the crescent symbol on war shields and many other accoutrements of state.Footnote 59 As for the star-shaped medals, in Islam God is described as light: as the Holy Quran proclaims, ‘God is the light of the heavens and earth’.Footnote 60 Stars produced light in the heavens, so it is not surprising that the star came to occupy a very important place in Islamic iconography. They were used to decorate sacred buildings as well as illuminations for sacred texts. The repeating geometric patterns that multi-triangle stars produce are a glimpse into the spiritual world and perfection. The Greeks had contemplated the perfection of geometry and came to associate it with divine properties. The Muslims, who studied Greek mathematical works, among others, agreed and integrated geometric art as a spiritual gate to the divine plane.Footnote 61

But why are two medals—small and large—awarded? What purpose did the smaller medal serve? While we initially thought that the smaller medals were used in imitation of the miniature medals of European officers when they were in undress uniform, we soon discounted this idea because miniature medals were first made and worn in England as late as 1815, at the close of the Waterloo campaign which was the first war where British soldiers across ranks were awarded a military medal.Footnote 62 This was more than three decades after this manuscript was written.

The answer to this question lies in a portrait of Tipu Sultan himself, seen in Figure 15A. In this portrait, the ruler of Mysore is wearing a bright green tunic with matching green turban, decorated with a jewelled ornament. He wears three pearl necklaces, each with a jewelled pendant, of which the lower two are of a similar design but different sizes. Of these two necklaces, the necklace on the top with the smaller pendant was called jugni and the one at the bottom was called kanthi.Footnote 63 We can see that this large and small set of medals was imitating a popular jewellery tradition of that time. In the Deccan, the practice of the ruler bestowing a favour on someone through the gift of jewellery was well established by Tipu Sultan's time.Footnote 64

Figure 15. Sketch of the padakah awwal bakhshiyaan kachehri assadullahi wa Ahmadi (folio 14b). Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society Calcutta.

Figure 15A. Portrait of Tipu Sultan (1749–1799) (Mysore, 1790). Source: Gayer-Anderson Collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

The combination of diamonds, rubies, and emeralds with the occasional pearl set on gold that we see on the medals would have been crafted at the royal workshops in Mysore which were known for producing some of the finest specimens of jewellery from India in the eighteenth century.Footnote 65 It was only the king and his family who were permitted to adorn themselves with such jewellery in court. Subjects who were gifted jewellery by the king himself were allowed to wear it in court as a symbol of royal patronage and honour.Footnote 66 A Padakh awwal bakhshi awwal jaish kacheri would thus have adorned the bakhshi in the same way as the jugni-kanthi necklace and would have announced to the durbar (assembly) the prestige of the wearer.

The chain of a specified length would be attached to the tiger mouth-shaped suspension on the large medal; from there it would go around the passages at the back of the small medal. The two medals, with the smaller above the larger, would be worn together, with the medals prominently visible on the wearer's chest.

Partially inlaid medals

Folio 15a contains a description and sketch of the first of the partially inlaid medals described in the manuscript. This medal (see Figure 16) is described as being similar in size and design to the inlaid medals (hasht-samosa type medal) for the jaish.

Figure 16. Sketch of the padakah hasht durran askar sawaraan (folio 15a). Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society Calcutta.

The description of the design of the padakah hasht durran askar sawaraan (medal with eight gems for cavalry) is as follows (see Figure 16):

One triangle (samosa) edge is inlaid with a ruby and the others with emeralds. The monogram ‘assadullahi’ is in the center along with a large ruby. In total, the medal is inlaid with nine gems and has a lining around the monogram as well as the edges of the triangles of four as well as one and a half taha width respectively. This medal has a chain of 8 girah length attached to two ends of the medal instead of the usual tiger face suspension.

The description on folio 15b (see Figure 17) has instructions prescribing different designs for the risaal-daraan (head of a regiment) from different military departments. Designs varied from department to department. For instance, risaal-daraan from kachehri ahmadi would be granted a tiger-nail shaped medal with one gem inlaid in the middle. The partially inlaid star-shaped medal that was awarded to sarysaqchis of the jaish-huzur kacheri is described as an eight triangle (hasht-samosa) medal of silver with three bubris (within each triangle) and one gem inlaid in the middle

Figure 17. Design and sketch of the medal for saryasaqchis (folios 15b and 16a). Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

Note:

The partially inlaid medals were made with equal skill as the fully inlaid medals but lack the work on gold as well as the variety and the number of precious stones that embellished the inlaid medals discussed earlier. These were for senior functionaries, while the partially inlaid medals seen here were for middle ranking functionaries. This shows that the monetary value of the medals decreased with the rank of the awardees, thus contradicting Beatson's claim that Tipu Sultan paid no attention to rank or position. Folio 16a (see Figure 17) also has the sketch of the medal for saryasaqchis.

Silver medals (padakah naqrai)

Folio 16a also describes the silver star-shaped medal to be awarded to individuals holding the positions of jouqdar Footnote 67 of the jaish (infantry) and sarysaqchis Footnote 68 of the asadullahi kacheri. Details on the size of the decorations follow and the depiction of the medal is found on folio 16b. This folio also mentions that jauq-daraan ta'lluqa jaish, sar-yasaqchiyaan kachehri assadullahi, among others, will be awarded this medal. It seems that it was designed for the ‘jauq-daraan’ and ‘yasaqchiyaan’ within the army.

The padakah naqrai malma' tilai wa zanjeer naqrai (silver gilt medal with a silver chain) (see Figure 18) is described as being of silver gilt and star shaped. It is suspended with a silver chain.

Figure 18. Description and sketch of the padakah naqrai malma' tilai wa zanjeer naqrai (folios 16b and 17a). Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

Folio 17a describes the silver multi-arch shaped medal that was prescribed for the sarkhel Footnote 69 ranks within the army. The sarkhel ta'lluqa jaish (sarkhel belonging to the infantry), sarkhel 'alam-bardar sawaar (sarkhel who is flag bearer (alam-bardar) of the cavalry), and the sarkhel jaish 'alam-bardar (sarkhel who is flag bearer of the infantry) would be awarded this medal.

The padakah naqrai do-az-dah burji (silver medal with twelve arches) (see Figure 19) is described in folio 17b as follows:

It is of equal length and width of four angusht and four taha. At its centre is the monogram ‘asadullahi’ in a square of one angusht long and 12 taha wide. The medal is worn with a silver chain attached to it on two sides.

Folio 18a describes and depicts the silver square shaped medals that were awarded to ‘shihab-daraan’.

Figure 19. Description and sketch of the padakah naqrai do-az-dah burji (folio 17b). Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

The padakah naqrai mrubba' babat shihab-daraan (square silver medal for rocket-men) (see Figure 20) for rocket men is described as follows:

The square gold gilt medal is of four angusht and four taha length and width. There is a square ‘asadullahi’ monogram of one angusht length and one angusht four taha width at its centre. The medal is worn with a 20 girah length silver chain attached to a suspender.

Figure 20. Description and sketch of the padakah naqrai mrubba' babat shihab-daraan. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

Note:

In Mysore the rocket was called ‘baana’—Kannada for arrow—and the rocket men were called ‘baana-dar’ or ‘they who hold arrows’. In his time Tipu renamed ordinances and gave the baana another name ‘shihab’—‘shooting star’.Footnote 70 In Haidar Ali's time Mysore holds the distinction of using rockets with metal casings for the first time in history.Footnote 71 This was a major scientific leap forward that would have far-reaching effects on the science of rocketry. In Tipu's army a company of 39 rocket men was attached to each qushoon.Footnote 72

Folio 18b has the description and sketch of the silver round medal which is mentioned as being awarded to dar-khash-andazaan Footnote 73 (gunners attached to the Mysorean army). The text describes the padakah naqrai dar-khash-andazaan qurs mudawwar (silver medal for dar-khash-andazaan round tablet type) (see Figure 21) and mentions that it is round, with a silver chain for the suspender and the ‘asadullahi’ monogram at the centre.

Figure 21. Design and sketch of the padakah naqrai dar-khashandazaan qurs mudawwar (folio 18b). Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

Note:

Each qushoon (brigade) had a jouq of gunners attached to it to man the cannon. The number of guns attached to each qushoon depended upon the strength of the corps and the nature of the service and, accordingly, varied in size from one to five guns.Footnote 74

It is recorded that after the conquest of Seringapatam, ‘There were taken 929 pieces of cannon, including mortars and howitzers, 424,000 iron balls, 520 000 lbs. of powder and 99 000 stand of arms, while in the magazines and foundries was found all manner of warlike munitions in the same proportion.’Footnote 75 All the above medals are silver and were awarded to relatively junior ranks like alam-bardars (flag bearers), jouqdars (captains), darkhash-andazan (gunners), and shihabdar (rocket-men). Devoid of any precious gems, they are an example of the simplest kinds of medallion made of a precious metal. However, the medal for rocket-men made of gold gilt symbolises the importance of the ‘baana’ or war rockets in the Mysorean military arsenal.

Folio 19a has the description and sketch of the silver octagon-shaped medal that was awarded to ‘khalasis’ Footnote 76 in service of the Mysore army. The text describes the design of the padakah khalasiyan naqra hasht-pehloo (silver medal with eight edges (octagonal)) (see Figure 22) and mentions it having a silver chain for the suspender and the ‘asadullahi’ monogram in the centre. Another medal for the leader of the khalasis (jouqdar) is the padakah sar-i-lashkar khulasiyaan babat tilai. This medal is described as octagonal shaped, gold, and inlaid with rubies and diamonds. It also has the assadullahi monogram with a diamond at the centre.

Figure 22. Description and sketch of the padakah khalasiyan naqra hasht-pehloo (folio 19a). Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

Note:

The ‘khalasis’ are proficient in the maintenance and repair of machinery in the army camp. Relying largely on physical strength, skill, and teamwork, they used the dabber, slinky, ropes, and pulley among other tools. They would also create tools to ease their efforts if and when the situation demanded. The khalasis were also organised in jouqs or companies with a jouqdar as their leader and these jouqs, along with other kinds of jouqs, were incorporated into a qushoon.Footnote 77

Copper medals

Folio 19b has the description and sketch of a copper crescent-shaped medal to be awarded to the gardoon-nawaz, fay-nawaz, sanjar-nawaz, and the tari-nawaz of the asadullahi and ahmadi infantry as well as the tari-nawaz of the regular cavalry.

The padakah hilali mussi malma' tilai (copper crescent-shaped medal gilded with gold) (see Figure 23) is described as follows:

It is a crescent shaped medal of six angusht height and six angusht and eight taha width. The tips of this crescent are one angusht and four taha wide which steadily increase to one and a half angusht at the broader part of the crescent where a monogram asadullahi of fourteen taha length and width one angusht and four taha is stamped. The width of the chain suspenders for silk ribbons at each of the ends is 12 taha and these ends themselves are separated from each other by a distance of one angusht and four taha.

Folio 20a has been left blank. Folio 20b is the final folio that describes medals and includes the description and sketch for a gold medal which is awarded to the leader of the group of khalasies. The padakah sar-i-lashkar khulasiyaan babat tila (gold medal for the head of the group of khalasies with gold chain) (see Figure 24) is described as follows:

Figure 23. Description and sketch of the padakah hilali mussi malma' tilai. Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

Figure 24. Description and sketch of the padakah sar-i-lashkar khulasiyaan babat tila (folio 20b). Source: Risala-i-Padakah, PSS 1640, Asiatic Society, Calcutta.

Figure 24A. Tippoo's bodyguard. Source: Thomas and William Daniell, British Library IOL, P&D.

This medal is inlaid with rubies and diamonds. It is octagonal in shape and has an assadullahi monogram in the middle. There is a diamond inlaid in the middle of the monogram.

Note:

Even as late as the eighteenth century, the large majority of medals in the West were cast as portraiture or emblematic tokens that concentrated on the dignity derived from rank. The military medals that started being awarded towards the end of that century in Europe were reserved for the officer class and it was not until as late as 1851 in England that soldiers of ‘other ranks’ were allowed to wear these medals in cases where they were awarded to them.Footnote 78

The examination of this manuscript has brought to light a different approach that Tipu Sultan adopted in the presentation of medals. The following two medals were awarded to the least among the ranks of men who served in or were attached to the army. That these non-combatants were also considered by Tipu Sultan to be worthy of wearing a medal is testament to the attention that each department of his government and army received from him as well as the importance given to each functionary, however small a rank he may have held. There could have been no greater encouragement that this to the personnel from the lower ranks.

On the medals of Tipu Sultan and kingly behaviour

Towards the later part of the eighteenth century, Mysore burst upon the world stage as the greatest threat to the British colonial enterprise in India. It succeeded in doing this by replicating, albeit on a smaller scale, the emerging European model of an industrial state with a strong army. Tipu Sultan had realised that the East India Company could only be fought with its own weapons. Some of these weapons were trade monopoly, military modernisation, import of technology, innovation, diplomacy, mass production as well as standardisation of the means of production. Unlike other Indian rulers, Tipu Sultan imitated the EIC military model in many respects, even in giving awards for service. The design of military medals and instructions contained in this manuscript would have aided the designers in their production.

The East India Company had already awarded its first medal—the Deccan Medal—to native Indian troops who took part in the major English campaigns in India between 1778 and 1784.Footnote 79 There was, however, no precedent for the making or awarding of medals in any Indian state prior to that of Tipu Sultan's Mysore. There is also no manuscript, such as this one, for the production and use of such insignia prior to the production of the Risala-i-Padakah. This Mysorean innovation stemmed in no small measure from an urge to honour its own men with something tangible as a reward and token of appreciation from the state.

Through rewarding his men with medals, Tipu was actually transferring his authority down to his subordinates who wore the medals, thus strengthening their loyalty to the sultan. F. W. Buckler has argued that: ‘the Eastern king…..stands for a system of rule of which he is the incarnation, incorporating into his own body, by means of certain symbolic acts, the person of those who share his rule’. Once incorporated after the gifting of a medal, according to Buckler, ‘a person became a deputy of the king, performing such functions of the king as has been delegated to him and, in the ruler's absence, acting as the king would act’.Footnote 80

Conclusion

A letter from Tipu to his ambassadors instructed them to visit the raja of Kutch, where Tipu had a factory. They were informed that the raja's brother and another of his officials had already been presented with an ‘honorary dress’. The ambassadors were instructed to visit the raja's officers and ‘be careful to inspire them with hopes of the favour of the presence (Tipu Sultan), and render them subservient to the will of the Khoodadaud Sircar’.Footnote 81

Tipu's assertive appropriation of the loyalty of his men through actions like the presentation of medals ensured that they remained intensely devoted to him, even in times of great adversity. As Thomas Munro has pointed out, during the Third Anglo-Mysore War the Mysore ruler's military setbacks were never brought about by the defection of his officers.Footnote 82

With regard to Tipu Sultan's ordinary subjects, for the time they were said to have displayed unusual loyalty to their ruler. Mackenzie noted that in the southern part of Tipu's dominion, in the region of Dindigul, they ‘yielded to a change of government with a degree of reluctance, seldom exhibited by the inhabitants of eastern countries’.Footnote 83 Evidently, Tipu's policy of rewarding his subjects, as low in rank as water-bearers and timekeepers, contributed in some measure to the loyalty they felt for their sovereign.

The authors have still not yet come across any example of these medals in museums, private collections, or auction catalogues. Some clues as to why this is the case may be found in eyewitness accounts of that time. One such account is this: ‘During a search of his palace in 1795, some gold medals were found in the palace, on which the following was inscribed on one side in Persian: ‘of God the bestower of blessings’ and the other: ‘victory and conquest are from the Almighty’. These were carved in commemoration of a victory after the war of 1780.’Footnote 84

Interestingly, there are at least three references to medals in the Nishan-i-Haidari, an eyewitness account of the lives of both Haidar Ali and Tipu Sultan. Tipu's biographer Kirmani testifies that the sultan rewarded the sipahdars with medals: ‘khud banawazish wa inamaat padak wa halqa-i-dast sarfraz gashtand’ (The sultan himself rewarded (the sipahdars) for their hard work with medals and pearls and armlets).Footnote 85 This would have been the nakhoon sher medals awarded to the sipahdars of the asadullahi and ahmadi kacheris.

The second reference is to the mir miraans (senior ministers) being presented with bejewelled medals: ‘ba-jami' mir-i-miraan turrah hai tilaa par jawahir padak hai mursa inayat wa marhamat gardid’ (All mir-i-miraans were rewarded with gold embroidered robes, bejewelled tassels and inlaid medals).Footnote 86 And, once again, Kirmani, when describing the events after Tipu's death, mentions ‘takht shikasta yafta ma'a zewar mursa wa padak hai jawahir wa maal hai marwarid waghairah sandooqcha haraaj’ (The throne was broken up with jewels and chests upon chests of bejewelled medals and pearl necklaces were sold by auction).Footnote 87 All these accounts are of the period 1793–1797. Perhaps the most compelling evidence of the state having awarded medals to its servants is this watercolour attributed to the Daniells who were touring in Mysore, exploring several hill forts there between 1792 and 1793.Footnote 88 The painting (see Figure 24A) shows a flintlock-bearing bodyguard of Tipu striking a proud pose wearing the typical uniform of Tipu's soldiers, with bubris stripes on purple cloth.

What is striking here is a golden object shown on the belt he wears towards the left of his chest. In the eighteenth century, although there was no formal regulation, medals, secured with a ribbon, were usually worn on the left side of the chest, even in Europe. This gold-coloured object on the left-hand side of the bodyguard's chest is most likely to be one of the Mysore medals described in the manuscript.

But what can account for the intriguing fact that none of these medals has come to light in museums or in private collections to date? A clue to this can be found in the translation of Kirmani's biography of Tipu Sultan, by Colonel W. Miles published in 1864, where the Persian word for medal, padakah, is translated as ‘jewelled gorget’ and not as ‘medal’.Footnote 89 This suggests that they were mistaken for regular pieces of jewellery and probably broken apart for their precious gems and the simpler silver and copper medals simply discarded or melted down. Due to this error of attribution, posterity was unaware of the existence of Tipu's medals on such a large scale. The authors hope that this article will bring about some awareness and ignite a search for any of these medals that may have survived.

Today in the twenty-first century when every authority—commercial or governmental—has its own corporate identity manual, it is indeed notable that back then the state of Mysore understood the importance of representing symbols and insignia of the state across the board. Such a distribution of medals goes to show that Tipu Sultan, far from being ‘faithless, paying no respect to rank or position and being unfit to rule’, was an able ruler: in awarding these medals the sultan highlights his complete confidence in the recipient's ability. There is reciprocity here: where the sultan bestows his trust on the recipients, his subjects demonstrate their loyalty by serving the state with all their abilities.

Tipu gave importance to the order of ranks in awarding the most inlaid medals to higher ranks, while simpler medals went to lower ranking personnel. However, he paid due respect and attention by awarding medals to even low-ranking servants such as the water carriers, cleaners, and loaders. The details of the distribution of ranks in his army show high levels of planning and governance on the part of the sultan. A sultan who was ‘unfit to rule’ would not have been able to commission such a manuscript to organise his military at a time when three hostile neighbouring armies were on the attack.

Joshua Ehrlich contends that Tipu used his library to legitimise his authority and that after defeating him in 1799 the East India Company did the same by seizing its contents which would have been useful and important enough for the victors to appropriate.Footnote 90 Tipu Sultan's personal seal and signature on this manuscript also displayed his attributes as a leader who was astute enough to commission and personally review this manual. As we can see, all of this stands in sharp contrast to the character that his adversaries of that period and even later thrust upon him.

On the evening of 5 May 1799, by which time the palace containing his library had been ransacked, the funeral procession carrying the mortal remains of Tipu Sultan wound its way slowly and silently through crowds of weeping onlookers.Footnote 91 He ruled over Mysore for only 17 years but he managed to pivot himself as the single Indian ruler who did more than any other to resist the onslaught of the English. This resistance would not have been possible but for the innovations and regulations of his government, an example of which is seen in this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the president of the Asiatic Society, Calcutta, for facilitating their study of the manuscript. Special mention needs to be made of all the assistance provided to the authors by the following: the late Professor Isha Mahammad, president of the Asiatic Society; Dr Keka Adhikari Banerjee, curator of museums, and Mr Syed Shah Fadir Irshad Al Qadri, keeper of manuscripts—Persian department. The authors are grateful to the reprography department of the Asiatic Society, Calcutta, and Sukant Bhattacharjee for their timely assistance. And, finally, we thank the reviewers of JRAS for their patience as well as their most valuable comments.

Conflicts of interest

None.