Introduction

‘Strategy’ is defined by Bryson and George (Reference George2020, p. 3) as “a concrete approach to aligning the aspirations and the capabilities of public organizations or other entities in order to achieve goals and create public value.” While strategy has long served public purpose – especially in a military and governance context (Freedman, Reference Freedman2013; Gaddis, Reference Gaddis2018), public strategy has only recently become a focal point of much public policy and administration research (Ferlie & Ongaro, Reference Ferlie and Ongaro2015; Bryson & George, Reference Bryson and George2020). Literature reviews suggest that much of this research has centered on linking specific strategy processes or content directly to public service performance (Walker, Reference Walker2013; George et al., Reference George, Walker and Monster2020). For instance, studies have investigated the public service performance impact of strategic planning and management (e.g., Johnsen, Reference Johnsen2018), of network governance and management (e.g., Warsen et al., Reference Warsen, Klijn and Koppenjan2019) and of having prospector, defender or reactor strategy content (e.g., Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Boyne and Walker2006). While these studies have been extremely useful in their own right, other public strategy scholars have argued that public strategy is a micro-level practice, something individuals and teams of policymakers ‘do’ (e.g., Hansen, Reference Hansen2011; Brorström, Reference Brorström2019; George, Reference George2020), and how they do it explains the extent to which public strategy eventually influences public service performance. In other words, these scholars suggest that the meso-level relationship between public strategy and public service performance is enabled or constrained by micro-level mechanisms (Höglund et al., Reference Höglund, Caicedo, Mårtensson and Svärdsten2018). One such micro-level mechanism that has been shown to be particularly important in organizational theory is strategic decision-making (Brunsson, Reference Brunsson2007).

But how can one study micro-level mechanisms such as strategic decision-making? This New Voice article aims to present and discuss a conceptual framework (i.e., ‘behavioral public strategy’) that can be used to investigate the micro-foundations of public strategy using theories from behavioral science. Specifically, I ask: How can we link public strategy research with theories from behavioral science? To answer this question, I combine insights from more classic books and articles on public strategy and behavioral science to construct the conceptual framework of behavioral public strategy with more recent empirical studies in public policy and administration research to exemplify the constructed framework. Importantly, this is not a systematic literature review aimed at exhaustively identifying all of the literature on the subject; rather, this is a narrative, theory-building review aimed at presenting and explaining a conceptual model for future research that will help us to theorize and to test how the public strategy and public service performance relationship is enabled or constrained by micro-level mechanisms.

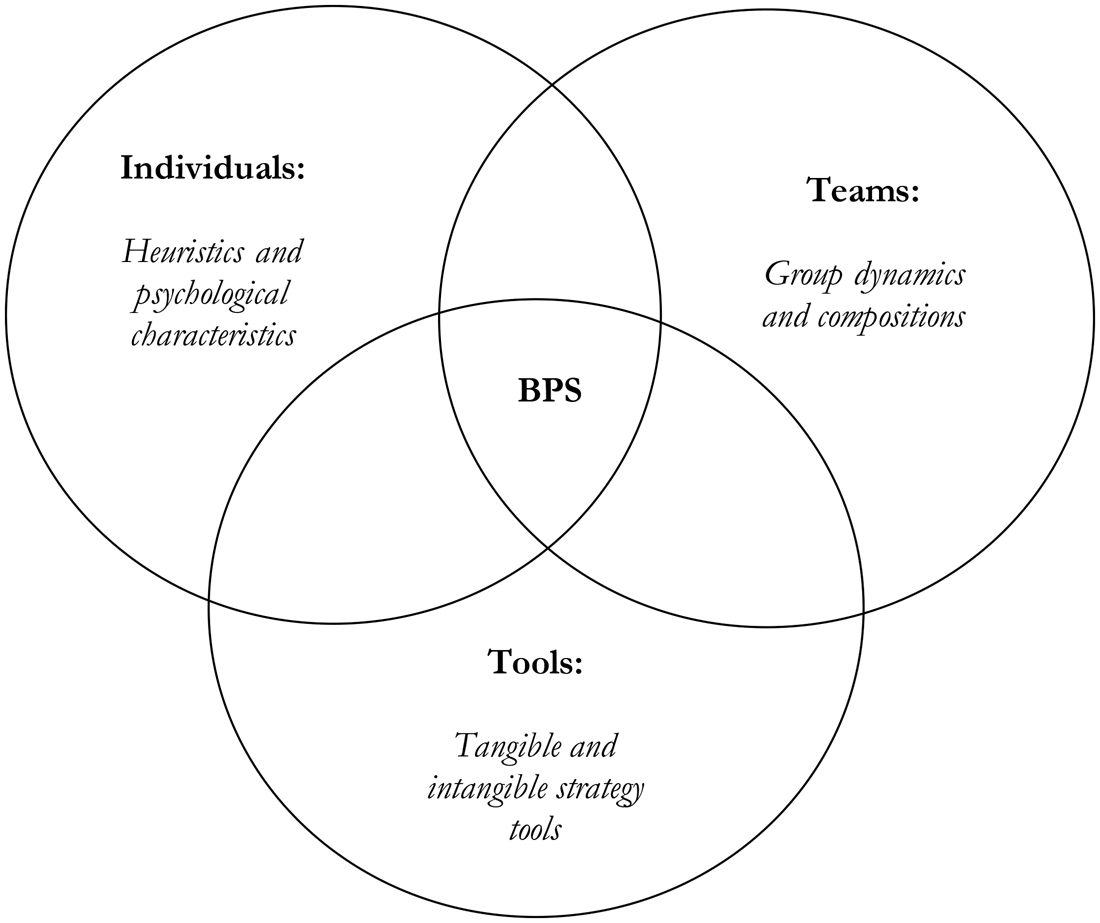

The recent influx of theories from behavioral science into public policy (Oliver, Reference Oliver2013) and public administration (Grimmelikhuijsen et al., Reference Grimmelikhuijsen, Jilke, Olsen and Tummers2017) research offers an important starting point to elucidate the need for and focus of behavioral public strategy. Such research has shown: (1) the existence of several heuristics, or shortcuts, taken by policymakers that might result in biased strategic decisions (e.g., Nielsen & Baekgaard, Reference Nielsen and Baekgaard2015; Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Dahlmann, Mathiasen, Moynihan and Petersen2018; George et al., Reference George, Walker and Monster2020); (2) that psychological characteristics of policymakers impact their ethical, information-seeking and learning behavior (e.g., Kroll, Reference Kroll2014; Stazyk & Davis, Reference Stazyk and Davis2015; George, Reference George2020); (3) that group dynamics among teams of policymakers influence the quality of strategic decisions as well as trust-related outcomes between these policymakers (e.g., Grissom, Reference Grissom2014; Klijn et al., Reference Klijn, Edelenbos and Steijn2010; George & Desmidt, Reference George and Desmidt2018); (4) that team composition influences shared understanding among policymakers, financial decisions and learning with partners (e.g., Opstrup & Villadsen, Reference Opstrup and Villadsen2015; Siddiki et al., Reference Siddiki, Kim and Leach2017; Desmidt et al., Reference Desmidt, Meyfroodt and George2018); and, finally, (5) that strategy tools employed by policymakers can be boundary-spanning or sense-making objects, but can also induce specific heuristics and lead to biased strategic decisions (e.g., Spee & Jarzabkowski, Reference Spee and Jarzabkowski2011; Vining, Reference Vining2011; Bryson et al., Reference Bryson, Ackermann and Eden2016; Höglund et al., Reference Höglund, Caicedo, Mårtensson and Svärdsten2018,). As such, a variety of public service performance dimensions can be affected, ranging from quality, efficiency, effectiveness, equity, service outcomes and responsiveness to more governance-related outcomes through these micro-level behavioral phenomena (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Boyne and Brewer2010). Behavioral public strategy thus explicitly focuses on how to make strategic decisions that enhance public service performance in public organizations and networks by looking at the micro-foundations of public strategy, namely the individuals (i.e., heuristics and psychological characteristics), teams (i.e., group dynamics and compositions) and tools (i.e., tangible and intangible strategy tools) underlying public strategy.

This conceptual framework differs from ongoing micro (public) strategy, behavioral public policy and behavioral public administration research in the following distinct ways. First, strategy as practice, a well-established movement in strategy research, albeit mostly in management, has also focused on the micro-foundations of strategizing (Whittington, Reference Whittington1996). The main difference, however, is that strategy as practice is a practice and process theory aimed at explaining ‘how’ practitioners strategize (Jarzabkowski & Spee, Reference Jarzabkowski and Spee2009). Behavioral public strategy is a variance theory in the sense that it aims to use theory from behavioral science in order to theorize about and test why specific variations in the individuals, teams and tools involved in public strategy influence strategic decisions and, in turn, public service performance. Second, behavioral public policy has typically focused more on citizens, companies and other societal actors and how they can be nudged into making decisions that increase their welfare and contribute to the common good (Oliver, Reference Oliver2013). Behavioral public strategy explicitly focuses on the actual policymakers making strategic decisions in public organizations and networks and how theories from behavioral science help unravel how they can make strategic decisions that contribute to public service performance. Finally, behavioral public administration has an almost unilateral focus on the micro-foundations of public administration and typically draws on experimental methods and psychological theory to explain the behavior of individuals (Grimmelikhuijsen et al., Reference Grimmelikhuijsen, Jilke, Olsen and Tummers2017). Behavioral public strategy is distinct from this movement because it: (1) uniquely focuses on public strategy as a focal point as opposed to other public administration topics; and (2) investigates micro-foundations of public strategy not only at the individual level, but also at the team level, and with the underlying quest to identify how micro-level mechanisms enable or constrain meso-level phenomena.

In what follows, I define behavioral public strategy, present the proposed conceptual framework and exemplify its underlying characteristics. I conclude with the implications of this framework for public policy and administration research.

Defining behavioral public strategy

Behavioral public strategy is a conceptual framework that aims to unravel how the individuals, teams and tools involved in strategic decision-making by policymakers enable or constrain the public strategy–public service performance relationship using theories from behavioral science.

This definition already indicates the core aspects of behavioral public strategy – namely its focus on (1) theories from behavioral science, (2) policymakers and (3) strategic decision-making.

Theories from behavioral science

The theoretical underpinnings of behavioral public strategy derive from behavioral science. Specifically, behavioral public strategy focuses on the individuals, teams and tools that underlie strategic decision-making in public organizations and networks. Behavioral public strategy is thus particularly interested in the micro-level of strategic decision-making in public organizations and networks (i.e., the actual people making strategic decisions). Figure 1 visualizes the theoretical focus of behavioral public strategy.

Figure 1. Micro-foundations underlying behavioral public strategy (BPS).

Heuristics and psychological characteristics

Fields such as behavioral economics, behavioral strategy and behavioral public policy have already identified how several heuristics can influence decision-making in general. Behavioral public strategy specifically identifies whether these heuristics also emerge in public organizations and networks when specific strategic decisions are made and whether these heuristics result in biased strategic decisions that hamper public service performance. For instance, Nielsen and Baekgaard (Reference Nielsen and Baekgaard2015) found that spending preferences of Danish policymakers are influenced by negativity bias, as opposed to being purely rational strategic decisions. George et al. (Reference George, Baekgaard, Decramer, Audenaert and Goeminne2018a) uncovered that performance information is used more to inform strategic learning by Flemish policymakers when a social norm is tied to said information. Christensen et al. (Reference Christensen, Dahlmann, Mathiasen, Moynihan and Petersen2018) identified how cognitive dissonance influences performance evaluations by Danish policymakers in the sense that preferences concerning the nature of government become more important than goal preferences. These studies thus indicate that heuristics can influence how strategic decisions are made (George et al., Reference George, Baekgaard, Decramer, Audenaert and Goeminne2018a), as well as how these decisions could influence effectiveness (Christensen et al., Reference Christensen, Dahlmann, Mathiasen, Moynihan and Petersen2018) and efficiency (Nielsen & Baekgaard, Reference Nielsen and Baekgaard2015) in public organizations and networks.

The psychological characteristics of individuals involved in strategic decision-making in public organizations and networks include, for instance, personality characteristics, cognitive styles and public service motivation. For example, George et al. (Reference George, Desmidt, Cools and Prinzie2018b) illustrated that the cognitive style of Flemish planning team members are predictors of their commitment to strategic plans – with members that have a creating cognitive style being more committed to plans as opposed to those with a knowing and planning cognitive style. Kroll (Reference Kroll2014) found that German policymakers with a creating cognitive style and high public service motivation are also more likely to use performance information to inform strategic decisions. Stazyk and Davis (Reference Stazyk and Davis2015) uncovered a positive relationship between public service motivation and ethical decision-making by policymakers in US municipal governments. These studies thus illustrate the importance of psychological characteristics in strategic decision-making in public organizations and networks in terms of the followed process (Kroll, Reference Kroll2014), as well as the impact on effectiveness (George et al., Reference George, Desmidt, Cools and Prinzie2018b) and governance-related outcomes such as ethics (Stazyk & Davis, Reference Stazyk and Davis2015).

Group dynamics and compositions

In addition to individuals involved in strategic decision-making in public organizations and networks, behavioral public strategy also explicitly looks at strategic decision-making teams. Specifically, behavioral public strategy seeks to identify the role of group dynamics and compositions. Group compositions focus on how strategic decision-making teams are actually composed and include, for instance, demographic, political, functional and cognitive diversity. For example, Desmidt et al. (Reference Desmidt, Meyfroodt and George2018) found that political diversity among Flemish city councils negatively impacts the extent to which these councils have a shared perspective on what the strategic priorities are in the local authority. Opstrup and Villadsen (Reference Opstrup and Villadsen2015) investigated gender diversity in top management teams within Danish municipalities and found that this diversity matters for the financial decision-making – and subsequent performance – of these municipalities. Siddiki et al. (Reference Siddiki, Kim and Leach2017) illustrated that diversity in beliefs among participants within a US-based collaborative partnership has a positive impact on relational learning within said partnership. These studies lead to the conclusion that team composition influences both how strategic decisions are made (Siddiki et al., Reference Siddiki, Kim and Leach2017) in public organizations and networks and governance outcomes such as shared understanding (Desmidt et al., Reference Desmidt, Meyfroodt and George2018) and efficiency (Opstrup & Villadsen, Reference Opstrup and Villadsen2015).

Group dynamics focus on the interactions within a strategic decision-making team and include, for instance, trust, conflict and justice perceptions. For example, Grissom (Reference Grissom2014) identified the negative impact of intra-board conflict on a range of board and organizational outcomes within school boards in California. Klijn et al. (Reference Klijn, Edelenbos and Steijn2010) focused on the role of trust between the key actors within a Dutch governance network and found that trust enhanced several network outcomes. George and Desmidt (Reference George and Desmidt2018) found that perceived procedural justice of strategic decision-making processes among Flemish pupil guidance centers is positively associated with the perceived quality of strategic decisions. These studies thus suggest that group dynamics underlying strategic decision-making in public organizations and networks influence governance outcomes such as collaboration (Klijn et al., Reference Klijn, Edelenbos and Steijn2010), broader organizational outcomes (Grissom, Reference Grissom2014) and quality (George & Desmidt, Reference George and Desmidt2018).

Tangible and intangible strategy tools

Strategy tools also play a vital role in behavioral public strategy. Strategy tools can be either tangible (e.g., strategic plans, SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats) analyses, balanced scorecards, performance information) or more intangible (e.g., creativity workshops, strategy retreats, role-playing games, teambuilding activities). Behavioral public strategy seeks to assess how these tools might strengthen or weaken the impacts of heuristics, psychological characteristics, group dynamics and group compositions on strategic decision-making in public organizations and networks. For example, Spee and Jarzabkowski (Reference Spee and Jarzabkowski2011) illustrated that writing multiple drafts of a strategic plan in a British university is an important communicative process. It helps policymakers comprehend and integrate different stakeholder perspectives during strategic decision-making, thus coping with team diversity. Höglund et al. (Reference Höglund, Caicedo, Mårtensson and Svärdsten2018) investigated the role of a range of strategy tools – including management by objectives, strategic plans and balanced scorecards – during strategic decision-making within the Swedish transport administration. They concluded that using these tools creates specific tensions during strategic decision-making that might induce specific biases, including finding a balance between the short and long term, parts and the whole and reactivity and proactivity. In other words, these studies show how tangible strategy tools help achieve governance outcomes such as shared understanding (Spee & Jarzabkowski, Reference Spee and Jarzabkowski2011) and influence the potential biases underlying strategic decisions (Höglund et al., Reference Höglund, Caicedo, Mårtensson and Svärdsten2018) in public organizations and networks.

Vining (Reference Vining2011) developed an updated version of Porter's Five Forces model specifically applied to the public sector. The underlying idea is that this specific strategy tool can help policymakers analyze and make sense of their environment during strategic decision-making in order to make more informed strategic decisions, thus coping with bounded rationality. Bryson et al. (Reference Bryson, Ackermann and Eden2016) similarly propose a specific strategy tool – namely visual strategy mapping – to help policymakers better understand potential collaborative advantages underlying inter-organizational collaborations. Again, such a tool facilitates collaboration within a strategic decision-making team even when team members come from different organizations. These studies thus demonstrate that strategy tools can influence how strategic decisions are made (Vining, Reference Vining2011) and stimulate governance outcomes such as a shared understanding of collaborative advantages (Bryson et al., Reference Bryson, Ackermann and Eden2016).

Policymakers

Behavioral public strategy explicitly focuses on the people actually making strategic decisions in public organizations and networks. In that sense, policymakers should be interpreted broadly rather than narrowly, thus including managers, board members, politicians, union representatives, consultants and staff functions. Behavioral public strategy does not have a predefined function (e.g., elected officials) that it focuses on, but rather identifies who is actually making strategic decisions in public organizations and networks. Moreover, behavioral public strategy focuses on strategic decision-making in the broadest sense. In other words, behavioral public strategy investigates strategic decision-making in more classical public organizations (e.g., municipalities, public schools or local authorities), as well as in other public entities such as inter-organizational collaborations (e.g., networks, public–private partnerships, communities). Indeed, strategic decision-making in the public sector not only occurs within organizations, but also often transcends organizational boundaries.

Finally, behavioral public strategy considers public organizations and networks as being mostly focused on creating public value (Moore, Reference Moore1995). In that sense, behavioral public strategy also looks at semi-public contexts and thus includes non-profit settings with a distinct focus on creating public value (e.g., hospitals, public–private partnerships, education and cultural organizations). Conclusively, behavioral public strategy is unique in the sense that it focuses on: (1) strategic decision-makers more broadly; (2) organizations and inter-organizational collaborations; and (3) the public and semi-public sectors. This is clearly distinct from other public strategy research that tends to focus on managers, organizations and the public sector more narrowly (for reviews, see Poister et al., Reference Poister, Pitts and Edwards2010; George & Desmidt, Reference George, Desmidt, Joyce and Drumaux2014).

Strategic decision-making

Strategic decisions in public organizations and networks are decisions linked to strategy formulation, strategy implementation or continuous strategic learning (Bryson & George, Reference Bryson and George2020). These decisions are thus focused on the long-term goals and public value that a public organization or network wants to achieve and how it does so. For example, strategic planning is often used to formulate strategies and includes a range of strategic decisions on (Bryson, Reference Bryson2018): Who is involved during strategic planning? What are the mandate, mission, values, purposes and vision of the organization or network? What are the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats of the organization or network? What are its competitive and collaborative advantages? Which strategic issues are confronting the organization or network? Which strategies address these issues? Who do we work with to realize these strategies and how? Similarly, strategy implementation often centers on change management, performance management, resource management and organizational design, and thus includes strategic decisions on (Poister, Reference Poister2010): How can we create commitment and a coalition of supporters towards strategies? How are resources allocated? Which goals, objectives and key performance indicators do we focus on? Which actions, programs and projects are stipulated to realize goals and objectives and by who? How do we structure our organization or network and attract human resources based on our strategy? Who is held accountable and how? How is performance being evaluated? Finally, strategic decisions are often also emergent in practice (Mintzberg, Reference Mintzberg1978) – policymakers need to continuously assess whether their strategic decisions concerning strategy formulation and implementation are still applicable or whether changes are needed (i.e., strategic learning). Strategic decisions here are thus mostly focused on ensuring the relevance of earlier strategic decisions and the need for potential changes.

Behavioral public strategy specifically focuses on the performance impacts of these strategic decisions, which have long been argued by organizational theorists to be critical predictors of performance across organizations and other entities (Brunsson, Reference Brunsson2007). In other words, behavioral public strategy seeks to elucidate how the teams, individuals and tools involved in public strategy can result in strategic decisions that enhance public service performance. The concept of public service performance has been at the forefront of public management research for the past two decades (Walker & Andrews, Reference Walker and Andrews2015). Public service performance is a multidimensional concept in which different public values are engrained and represented through different dimensions. These dimensions include quality, efficiency, effectiveness, equity, service outcomes, responsiveness and more governance-related outcomes in public organizations and networks (Walker et al., Reference Walker, Boyne and Brewer2010). Behavioral public strategy does not favor one dimension over the other, but aims to ensure a balanced representation of the different dimensions in subsequent research projects.

So which types of strategic decisions are needed to enhance public service performance? Behavioral public strategy focuses first on how strategic decisions are made. Within behavioral economics, two types of decisions are discerned: automatic versus reflective decisions (Thaler & Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008). Automatic decisions are the result of our System 1 brain (also called Homo sapiens) and are taken instantly, without careful consideration. System 1 is linked to cognitive ease, a state of mind where creativity is stimulated (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011). Reflective decisions are the result of our System 2 brain (also called Homo economicus) and emerge through a process of reflection before an actual decision is made. System 2 is linked to cognitive strain, a state of mind where analysis is induced (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011). Strategic decision-making in public organizations and networks is a balancing act between creativity and analysis, and sound strategic decisions require both sides of the coin. Behavioral public strategy thus explicitly investigates how individuals, teams and tools can induce (or hinder) creativity and analysis during strategic decision-making in public organizations and networks while simultaneously avoiding specific biases from creeping in. In other words, behavioral public strategy proposes that strategic decisions grounded in analysis and creativity and without detrimental biases are more likely to enhance public service performance.

Conclusively, the assumed causal pathway underlying behavioral public strategy implies multiple equations (and thus more complex causal models). Behavioral public strategy investigates how the individuals, teams and tools involved in strategic decision-making in public organizations and networks induce (or hinder) creative, analytic and unbiased strategic decisions and, in turn, how those strategic decisions impact public service performance. This causal, indirect logic between strategy and performance clearly differs from the direct effects often tested in contemporary public strategy research. Figure 2 illustrates this causal pathway, moving from strategy processes at the organizational and network levels to micro-foundations at the individual and team levels to strategic decisions at the individual and team levels, and finally to performance at the organizational and network levels (i.e., a bathtub model).

Figure 2. The bathtub model of behavioral public strategy.

Finally, it is also important to note that behavioral public strategy does not carry a methodological preference. As is clear from the earlier cited examples, behavioral public strategy aims to adopt a pluralistic methods perspective. The binding factor of behavioral public strategy research is its focus on the individuals, teams and tools underlying strategic decision-making in public organizations and networks and its usage of theories from behavioral science. Which method is employed depends on the type of research question asked. This pluralistic focus is in line with what is recommend by other scholars focusing on public strategy (Bryson et al., Reference Bryson, Berry and Yang2010; Poister et al., Reference Poister, Pitts and Edwards2010) and ensures a more inclusive research group than other behavioral groups that have tended to almost exclusively focus on experimental methods. Box 1 summarizes the abovementioned characteristics of behavioral public strategy.

Box 1. Characteristics of behavioral public strategy.

Theories from behavioral science

Individuals: heuristics and psychological characteristics

Teams: group dynamics and compositions

Tools: tangible and intangible strategy tools

Public organizations and networks

Organizations and networks, communities or other forms of collaborations aimed mainly at creating public value

Strategic decision-making

Decisions linked to strategy formulation, strategy implementation or continuous strategic learning

Policymakers

Any individual involved in making strategic decisions: managers, board members, politicians, union representatives, consultants and staff functions

Public service performance

Analytic, creative and unbiased strategic decisions that positively impact quality, efficiency, effectiveness, equity, service outcomes, responsiveness or more governance-related outcomes

Methodological focus

Pluralistic: qualitative, quantitative, mixed and multimethod

Discussion and conclusion

This New Voice article aimed to answer the question: How can we link public strategy research with theories from behavioral science? I presented a novel conceptual framework labeled ‘behavioral public strategy’ that can help us to answer this question. The framework combines insights from public strategy, behavioral public policy and behavioral public administration research to propose a bathtub model connecting micro- and meso-levels. Underlying the model is the idea that strategic decisions in public organizations and networks should contribute to public service performance. However, this contribution is enabled or constrained by the micro-foundations of public strategy, implying that the individuals, teams and tools involved in making strategic decisions impact on whether or not these enhance public service performance. Specifically, behavioral public strategy argues for the importance of strategic decisions being grounded in analysis as well as creativity and free from detrimental biases, and it proposes a focus on theories centered on heuristics, psychological characteristics, group composition, group dynamics, tangible tools and intangible tools. The proposed model has important implications for practice, theory and research.

There are a great many theories from behavioral science that can be fitted into behavioral public strategy's bathtub model. Theoretical mechanisms underlying heuristics, psychological characteristics, group composition, group dynamics, tangible tools and intangible tools can be extrapolated to the context of strategic decision-making in public organizations and networks. Behavioral economics has provided an overview of different heuristics and biases, such as outcome bias, hindsight bias, discriminatory bias, in-group bias and so on, which have been shown to impact on decision-making. Cognitive psychology has developed a range of psychological characteristics of individuals that have been shown to matter in decision-making, such as personality characteristics, cognitive styles, prosocial motivation and so on. Social psychology and management theory have identified a range of group composition and group dynamics that are important for team decision-making, including group demographic diversity, group functional diversity, group intellectual diversity, constructive conflict and so on. Similarly, strategy theory has developed a number of strategy tools aimed at supporting specific cognitive and social tasks, ranging from tools stimulating analysis (e.g., SWOT, benchmarking), to tools stimulating creativity (e.g., strategic off-sites, brainstorm sessions), to tools stimulating collaboration (e.g., strategy mapping, trust exercises). All of these fields provide interesting theoretical starting points for behavioral public strategy research and can provide the needed theoretical mechanisms to theorize about how the individuals, teams and tools underlying public strategy influence strategic decisions and, in turn, public service performance.

For practice, behavioral public strategy can help to raise awareness concerning the micro-level of public strategy. Indeed, behavioral public strategy brings the strategy practitioner to the forefront of research by investigating how policymakers actually make strategic decisions. Public strategy is not only about adopting specific strategy processes such as strategic planning or performance management, or about having more proactive as opposed to reactive strategies. It is very much about ‘people doing stuff’ – policymakers sitting together, using tools, debating about relevant courses and making strategic decisions. Behavioral public strategy fully recognizes this reality underlying public strategy and offers a pathway to understanding how this ‘doing of strategy’ in public organizations and networks can be optimized to produce strategic decisions that contribute to public service performance. A study published in McKinsey Quarterly (Lovallo & Sibony, Reference Lovallo and Sibony2010) already showed that strategic decisions free from bias in companies actually create monetary value (i.e., an increase in return on investment of 6.9% when moving from the bottom to the top quartile of unbiased strategic decision-making) and are good business. It is thus safe to assume that improving strategic decision-making in public organizations and networks through the insights provided by behavioral public strategy can be an important pathway to increased public service performance.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the anonymous reviewers and editors of Behavioural Public Policy for their excellent comments and handling of the manuscript. Special thanks also go to Rianne Warsen, Markus Tepe and Sean Webeck for their friendly reviews of the first draft of this manuscript. The manuscript was presented at EGPA's Behavioral Public Administration Study Group; thanks are given to the chairs and participants of that group for their excellent suggestions.