Although craft production has been studied extensively at Mayapan, the primary Postclassic period political capital of the Maya Lowlands during a.d. 1150–1450 (Figure 1), prior investigations have mostly focused on common goods pertaining to everyday life. In this article, we offer a perspective on attached production under elite supervision of two classes of symbolically charged goods—effigy censers and figurines. Historically, the making and exchange of restricted, artisanal goods at Classic period Maya (a.d. 250–900) centers has garnered much attention (e.g., Aoyama Reference Aoyama2009; Foias Reference Foias, Masson and Freidel2002; Inomata Reference Inomata2001; Luke and Tykot Reference Luke and Tykot2007; Reents-Budet Reference Reents-Budet1994). In contrast, research at Mayapan since the 1950s has focused on the material worlds of ordinary families (Brown Reference Brown1999; Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014a:18; Masson et al. Reference Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021; Pollock Reference Pollock1954; Sabloff Reference Sabloff2007; Smith Reference Smith, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962). Similarly, elite and public architecture feature prominently in the annals of Classic period publications (Sabloff Reference Sabloff2019:4), while only one top-tier Postclassic palace has ever been excavated in the Northern Maya Lowlands (Proskouriakoff and Temple Reference Proskouriakoff and Temple1955; but see Pugh et al. Reference Pugh, Rice, Cecil, Rice and Rice2009 for the Peten Lakes region to the south).

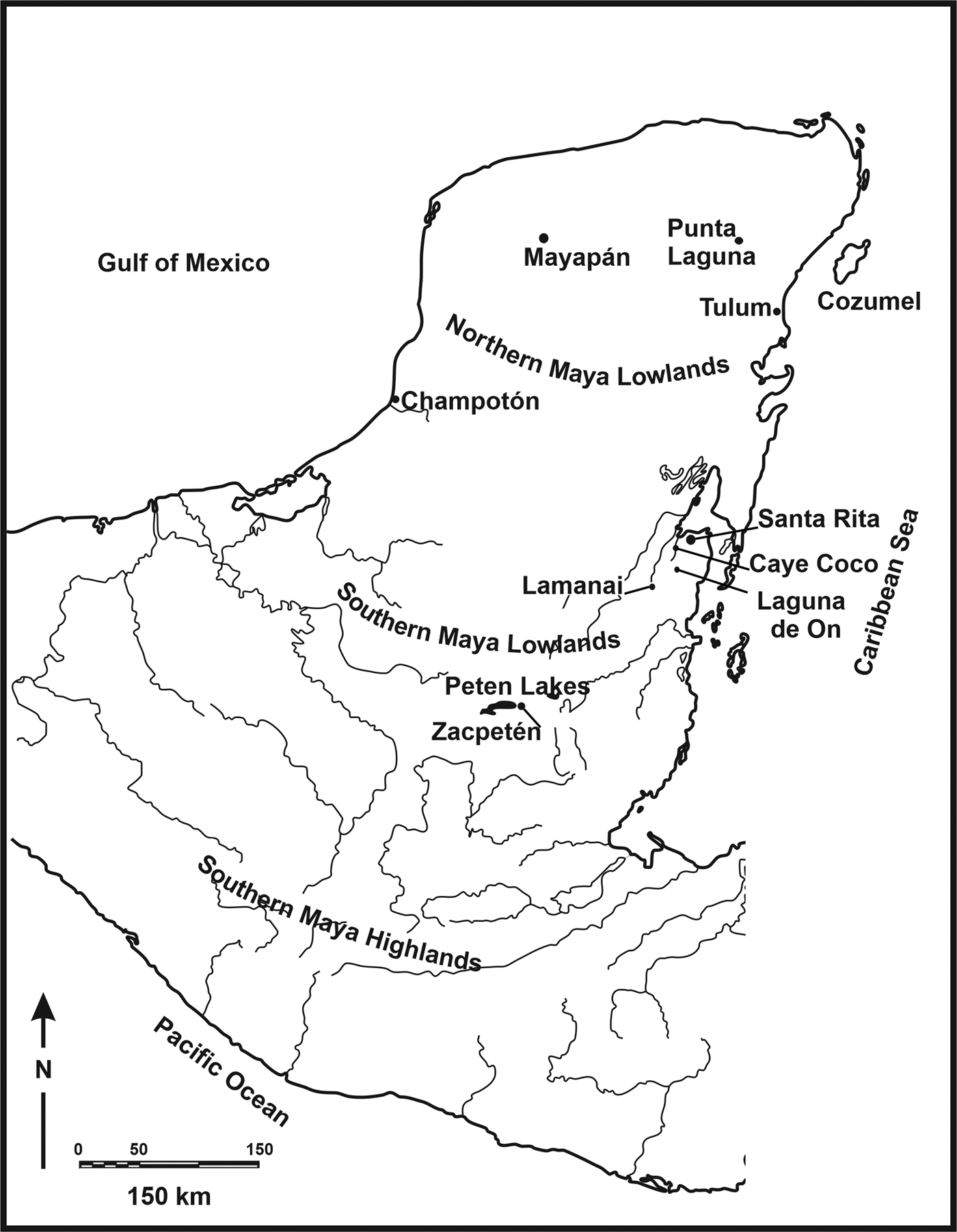

Figure 1. Location of sites discussed in text. Map by Masson.

The contrasting emphases for these time periods have fueled models regarding a prestige goods economy for the Classic Maya, based on political authority drawn from webs of personal obligations and gift-giving (e.g., Blanton et al. Reference Blanton, Kowalewski, Feinman and Finsten1993:221, Reference Blanton, Feinman, Kowalewski and Peregrine1996). The prestige goods model did not disappear once economies of everyday life were recognized within the residential zones of non-elites at Classic Maya sites with evidence for craft specialization and dependence on market exchange (Becker Reference Becker1973; Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase2004; Hester and Shafer Reference Hester and Shafer1984; King Reference King2012; Robin Reference Robin2012). For example, a dual-exchange model proposes that the circulation of elite treasures was distinct from that of objects commonly found in ordinary houselots (Scarborough and Valdez Reference Scarborough and Valdez2009). Blurring this dichotomous view are arguments for more complex, articulated economies in the Maya past, in which crafting of the exquisite and the quotidian was complementary, related, and overlapping (Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Masson and Rich2016, see also McAnany Reference McAnany2010:203). However, mold-made ceramics discussed in this article may represent an exception, given the social and spatial limitations of their production and use at Mayapan.

The quality and workmanship of objects sharing similar forms may be gauged along a continuum of relative value and frequency. Valuables regularly found in commoner contexts sometimes emulated exquisite, rarer forms (Freidel and Reilly Reference Freidel, Reilly, Staller and Carrasco2010; Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Reese-Taylor, Mora-Marin, Marilyn A. and Freidel2002, Reference Freidel, Masson and Rich2016: Figure 13; Lesure Reference Lesure and Robb1999; McAnany Reference McAnany2010:225). For example, axes of serpentine replicate the form of jade axes and Oliva sp. shells with simple notches (mouths), and perforations (eyes) abbreviate the features of those carved as death heads. Similarly, red shell beads overlap in form with white shell versions, and the former were worth more than the latter in the early Colonial period (Freidel et al. Reference Freidel, Masson and Rich2016:42–44). Parallel observations have been made for Classic period polychromes (Culbert Reference Culbert and Sabloff2003). Effigy censers and figurines at Mayapan exhibit partial overlap in terms of entities portrayed, but the former are more elaborate and limited in their distribution compared to the latter. Rare, exotic treasures, restricted to elite consumption, existed in pre-Columbian Maya society, just as for other complex societies, but their existence does not constitute an argument for a(n) (exclusively) prestige goods economy (Smith Reference Smith2004:89). The term “restricted goods,” as used in this article, refers to items not regularly found at commoner domestic contexts, but rather concentrated at or near elite residences or public buildings.

The Postclassic Maya period is best-known for its commercial economy (Sabloff and Rathje Reference Sabloff and Rathje1975; Smith and Berdan Reference Smith, Berdan, Smith and Berdan2003), although researchers now recognize that market exchange was also fundamental during the Classic period (Culbert Reference Culbert and Sabloff2003; Dahlin et al. Reference Dahlin, Bair, Beach, Moriarty, Terry, Staller and Carrasco2010; Fry Reference Fry and Sabloff2003; King Reference King2015; Masson and Freidel Reference Masson and Freidel2012, Reference Masson, Freidel, Hirth and Pillsbury2013). Contact period sources of the sixteenth century report lively trading ports, market towns, and canoe-borne merchants, yet potential historical analogies into the deeper past of the Classic period tend to be overlooked, given assumptions that the Postclassic/Contact era society was fundamentally different, and thus irrelevant to the study of its antecedents (Pollock Reference Pollock, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962:17; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1955, Reference Proskouriakoff, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962:330). (For a more detailed discussion of the “other” status of the Postclassic, see Masson [Reference Masson and Paris2021]).

This article challenges the idea of Classic to Postclassic differences in one specific aspect by documenting elite-sponsored craft production during the latter period. At Mayapan, sponsored artisans worked on behalf of palaces, governors, or priests at the city to manufacture restricted effigy pottery in a manner analogous to the sponsored production of symbolically charged polychrome vessels and goods at Classic Maya sites (Halperin Reference Halperin2014; Halperin and Foias Reference Halperin and Foias2010, Reference Halperin, Foias, Foias and Emery2012; Inomata Reference Inomata2001; Reents-Budet et al. Reference Reents-Budet, Bishop, Taschek and Ball2000). The site's effigy censers were of particular ritual significance, rendered in the likenesses of gods and ancestors and forming centerpieces of Postclassic Maya religion and ritual practice (Masson Reference Masson2000:224–239; Milbrath and Peraza Lope Reference Milbrath, Lope and Aimers2013; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Walker, Lope, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021; Rice Reference Rice, Rice and Rice2009; Russell Reference Russell2017). Molded figurines included in this discussion overlapped with censers in terms of production localities and, occasionally, in entities represented. They exhibit greater variation in their discard and use contexts, although both forms were used in public ceremonies. For modeled figurines made without molds, production localities are harder to track and are not considered here. However, they, too, were recovered mostly at public buildings (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Gómora and Hendon2012).

The recovery of ceramic molds provides the best evidence for production localities of Mayapan's effigy ceramics (Figures 2 and 3). We identify 27 production localities for ceramic figurines and effigy censers at, near to, or next to elite residential and public buildings at Mayapan and at four other localities representing ordinary dwellings (Table 1). These findings complement earlier extensive research at Mayapan that determined that the use of figurine and effigy censer fragments was scarce in ordinary houselots. Such artifacts were primarily made for elites and deposited in high-status mortuary contexts or discarded near public buildings (e.g., Thompson Reference Thompson1957:601–602, Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Gómora and Hendon2012; Peraza Lope and Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014a). Their manufacture concentrates within or adjacent to the site's monumental center. Years of survey and excavation in the urban and rural residential zones of the city (since 2001) failed to identify effigy ceramic workshops elsewhere at the site (Hare Reference Hare, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021). The term effigy ceramics as used here refers to effigy censers and figurines of the Chen Mul Modeled type (Smith Reference Smith1971:196, 210). Mayapan's residential zones commonly housed producers making surplus shell, obsidian, chert objects or everyday ceramic vessels for exchange (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014b; Masson et al. Reference Masson, Hare, Lope, Escamilla Ojeda, Paris, Kohut, Russell and Alvarado2016). Surplus craft production was arbitrarily defined in these prior studies at locations with densities (per cubic meter) of at least one standard deviation beyond the mean for an extensive sample of test pits or broader excavations. That most of these urban crafters did not undertake figurine or effigy censer production underscores the fact that doing so was a restricted practice.

Figure 2. Molds and clay impressions made from Mayapan structures R-183b, Q-40a, Q-141, and Q-57; (a–b) young male censer faces (miniature on the left may be an adorno); (c) merchant deity censer face; (d) Itzamna or Old God censer face; (e) animal figurine. Photographs and clay impressions by Russell.

Figure 3. Molds and clay impressions from Mayapan structures Q-54 and Q-99; (a) censer molds for a human face and merchant deity; (b) merchant deity figurine, Chaahk censer face, animal figurine; (c) female censer face and female figurine body. Photographs and clay impressions by Russell.

Table 1. Types of Postclassic period molds recovered by structure at Mayapan. Most structures lie within or adjacent to the monumental center (except for R-106, R-183b, S-132, AA-78, BB-12, P-146, and R-112) All but four structures (AA-78, BB-12, P-146, R-112) were elite or public buildings, or located next to or near to such buildings.

MAYAPAN'S ECONOMY

Mayapan was the primary political capital of the Postclassic lowland Maya world from a.d. 1150 to 1450. It was the central node of a market exchange system within northwest Yucatan and beyond, along the Gulf and Caribbean shores of the peninsula, and into the Guatemala Highlands (Figure 1). Craft production was well-developed at the city as well as at distant hinterland sites near the Caribbean coast of Belize (Masson Reference Masson2000, Reference Masson, Gyles and Connell2003). The manufacture and circulation of different combinations of products varied according to town and location in the Postclassic and Contact periods, as indicated by a 1549 tribute list analyzed by Piña Chan (Reference Piña Chan, Lee and Navarrete1978; displayed graphically by Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014b:Figure 6.1). Surplus craft industries at Mayapan involving shell, obsidian, chert/chalcedony, and ordinary pottery vessels were essential to this exchange system at the household, community, and regional (peninsular) scales (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014b; Masson et al. Reference Masson, Hare, Lope, Escamilla Ojeda, Paris, Kohut, Russell and Alvarado2016). Commoner crafter household wealth indices are higher than those of non-crafting commoner dwelling groups (Masson and Freidel Reference Masson and Freidel2012:Figures 3–8; Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014b:419). As for other pre-modern states, crafting helped to diversify Mayapan's domestic economies and promoted interdependencies at the site and regional scale.

Chert and chalcedony varied in quality, with finer varieties more common near the site center compared to its outskirts (Kohut Reference Kohut, Masson, Lope, Hare and Russell2012). Perishable goods made and/or exchanged into Mayapan that were essential to everyday life would have included wax, honey, copal incense, cotton (and other fabric) threads, salt, and wooden objects or raw materials (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014b). Objects made and sold at Mayapan, as well as nonlocal trade items, such as Gulf Coast (Fine Orange) pottery and obsidian from the Maya Highlands, were acquired by most houselots at the city. Long-distance seafaring merchants carried a portion of these goods along Maya area coasts and beyond. Aside from trade, some products satisfied tribute or ritual obligations. Mayapan obtained raw materials for its chert, marine shell, obsidian, and textile industries via exchange and converted these resources into finished products within residential workshops (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014b). Porous limestone caprock represents Mayapan's primary local geological resource, useful for rougher grinding stones, construction stone, and for rendering plaster. Finer, harder limestone metates and manos from elsewhere in northwest Yucatan were sometimes traded into the site.

In contrast to chert, shell, obsidian, and pottery vessels at the site, effigy censers and figurines were categories of goods for which production and use took place under elite supervision and at or near public buildings; use at selective mortuary settings is also observed. While goods made by or for elites may end up in typical commoner contexts in low quantities, such distributions contrast with the relative abundance of market-obtained goods, whether local and ordinary, local and embellished, or imported (Cyphers and Hirth Reference Cyphers, Hirth and Hirth2000; Hirth Reference Hirth1998; Masson and Freidel Reference Masson and Freidel2012). Elite patronage of effigy ceramic manufacture neatly matches Landa's sixteenth-century testimony regarding the strict supervision of “idol” carving (Clark and Houston Reference Clark, Houston, Costin and Wright1998:35–36, 41; Landa Reference Landa and Tozzer1941:159–160). Like mold-made censers and figurines, metal objects, particularly bells, were also produced by elites or artisans in their service at Mayapan (Paris Reference Paris2008; Paris and Peraza Lope Reference Paris, Lope, Shugar and Simmons2013). Upper-status mortuary contexts have concentrations of copper objects that do not appear in commoner graves.

EFFIGY CENSER AND FIGURINE USE

Effigy Censers

Effigy censers were a hallmark object of religious practice at Mayapan and across the Yucatan peninsula (Figure 4), as has long been noted (Masson Reference Masson2000:197–216; Milbrath and Peraza Lope Reference Paris, Lope, Shugar and Simmons2013; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Aimers, Lope and Folan2008; Peraza Lope and Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014b:427–430; Thompson Reference Thompson1957). Their manufacture increased markedly during the second half of the city's occupation, from around 1300–1450 (Peraza Lope et al. Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Hare and Delgado Kú2006; Smith Reference Smith1971). Effigy censer use continued well into the Colonial period (Chuchiak Reference Chuchiak2003). Effigies were made in the images of gods or ancestral beings, who served as patrons for key ceremonial events or periods (Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Rice1985, Reference Chase, Sabloff and Andrews V1986; Graff Reference Graff, Bricker and Vail1997; Milbrath and Peraza Lope Reference Milbrath, Lope and Aimers2013; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Walker, Lope, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021:303; Peraza Lope and Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014b; Rice Reference Rice2004, Reference Rice, Rice and Rice2009; Russell Reference Russell2017). Effigies were installed and replaced periodically for k'atun, New Year, and other intervals. They were also deposited during rites of pilgrimages and other processions marking boundaries or ritual places, including monumental buildings of earlier periods that were incorporated into Postclassic sacred landscapes (Kovac Reference Kovac2020; Lorenzen Reference Lorenzen2003; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Walker, Lope, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021:307). Postclassic shrines at localities with or without substantial Postclassic period settlement were sometimes built to house censers (Kurnick Reference Kurnick2019:62–63; Masson Reference Masson1999:Figure 8; Walker Reference Walker1990:319, 407–409). Similarly, Postclassic effigy censers are common in caves and architectural shrines within caves in Quintana Roo (Pzrybyla Reference Pzrybyla2021:Table 6.1).

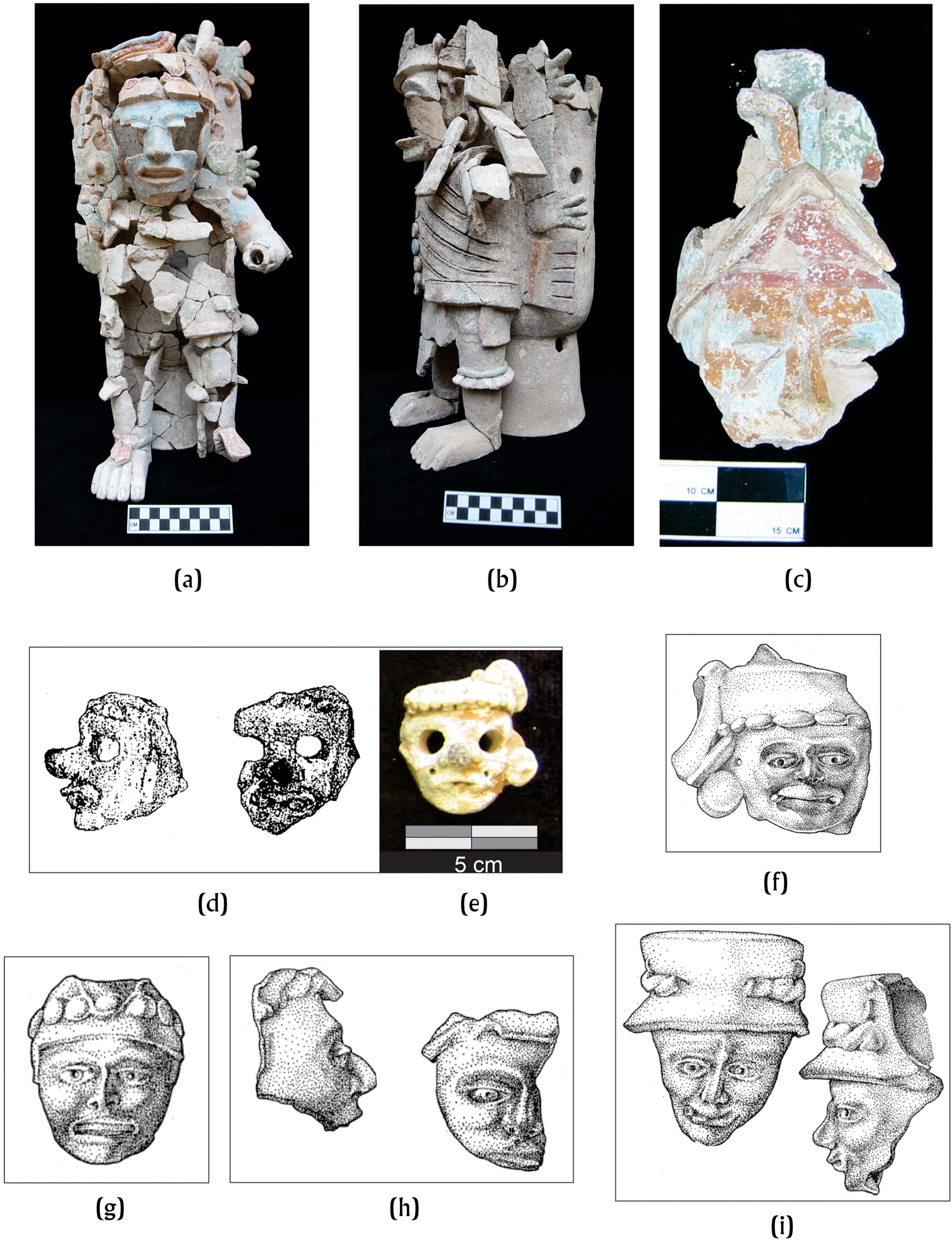

Figure 4. Examples of finished effigy censers from Mayapan, (a, b) with pedestal vase attached; (c) with stucco and paint on face; (d) an example from Laguna de On, Belize; (e) with a nearly identical rendition of the merchant god Ek Chuah; and (f–i) examples of finished effigy censers from Progresso Lagoon, Belize. (a–c, e) Photographs by Russell; (d) illustration by Anne Dean; (f–i) illustrations by Ben Karis.

Determining that effigy censers were restricted in distribution (Peraza Lope and Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014a) overturns longstanding assertions to the contrary, that they represented artifacts of household-scale, decentralized religious practice during the Postclassic period (Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff1955:88; Thompson and Thompson Reference Thompson and Thompson1955:238–242). Recent analyses indicate that effigy censers were heavily concentrated at elite dwellings and public buildings. No reconstructible effigy censers or concentrations of sherds from the same vessel were found during a long-term test pit and horizontal excavation program of commoner household contexts at Mayapan. For example, Chen Mul Modeled (effigy censer) sherds—a type that encompasses both effigy censers and figurines—recovered from modest commoner houses comprised less than 0.8 percent of the total number of sherds at five fully excavated commoner dwellings (Peraza Lope and Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014a:Table 3.3).

How might ordinary residents have obtained limited pieces of censers? It is true that effigy censers were large ceramic sculptures that were systematically smashed, discarded, and replaced throughout their period of use at Mayapan, creating hundreds of sherds per vessel (e.g., Masson et al. Reference Masson, Lope, Alvarado, Milbrath, Stanton and Kathryn Brown2020). Some acquisitions may have been casual. The feet, arms, faces, headdress elements, and hand-held adornos of censers had value as curio items, subjected to removal from their original contexts, even after sites were abandoned, as Walker (Reference Walker1990:31) observes.

Figurines

Human figurines in Mesoamerica are sometimes linked to household religious practices, especially in central Mexico (e.g., Brumfiel Reference Brumfiel and Wright1996; Halperin Reference Halperin2017:533; Smith Reference Smith2005:53). Figurines were also ubiquitous during the Mesoamerican Formative period (Lesure Reference Lesure2011; Rice Reference Rice2019). Female figurines from domestic contexts may have been associated with curing and ritual, particularly for women (Joyce Reference Joyce1993:265); and they may reflect female ideal types or roles (Joyce Reference Joyce1993; Lesure Reference Lesure, Claasen and Joyce1997; Robin Reference Robin, Hendon and Joyce2004:152–153; Triadan Reference Triadan2007:284). Women oversaw household ritual in much of the Mesoamerican past (Hendon Reference Hendon, Hendon and Joyce2004:314–317; Vail and Stone Reference Vail, Stone and Ardren2002). Aztec figurine traditions sometimes portray elites or deity figures (Charlton Reference Charlton, Hodge and Smith1994). Classic period Maya figurines also exhibit a number of vividly adorned social personae, many of them linked to noble, courtly, divine, or other supernatural personages (Butler Reference Butler1935; Halperin Reference Halperin2017:Table 2; Halperin et al. Reference Halperin, Faust, Taube, Giguet, Halperin, Faust, Taube and Giguet2009). Postclassic figurines of the Peten include high frequencies of female entities, along with males and a host of other more generalized personages for which social or religious identity is difficult to infer (Halperin Reference Halperin2017:Table 2). Mayapan's figurine assemblage is also numerically dominated by females, most of whom wear simple tunics (Figure 5). Other human, deity, and animal forms are also present (Figures 2–4, Table 2).

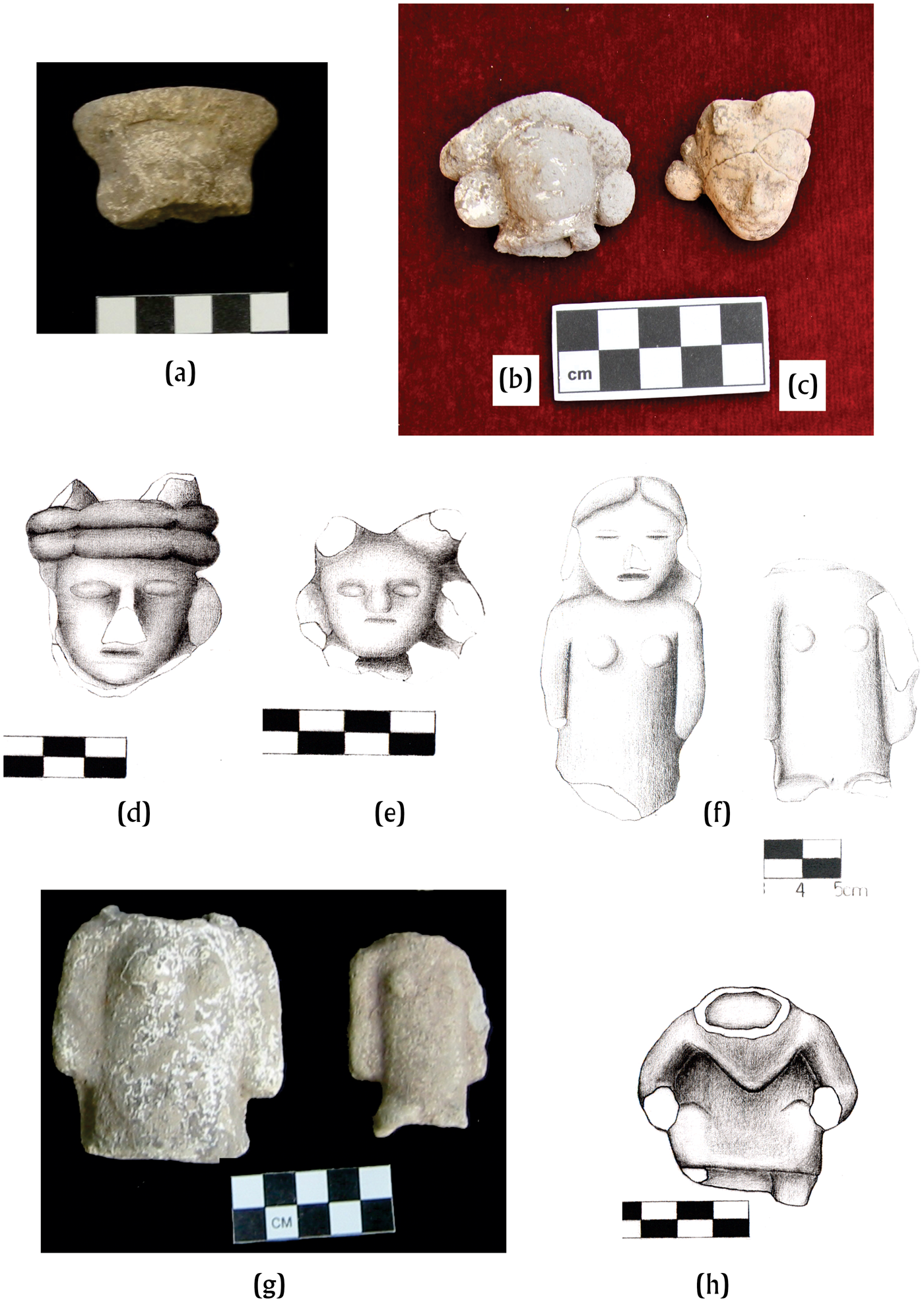

Figure 5. Female figurines from Mayapan, illustrating differences in hair, headdress styles, and dress, (a–c) from an upper-status burial at dwelling Q-39; and (d–h) from the monumental center. (a–c, g) Photographs by Masson; (d–f, h) illustrations by Cruz Alvarado.

Table 2. Identified figurine types from Mayapan. Data summarized from a previous study (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Gómora and Hendon2012), based on a sample of Peraza Lope's INAH-Mayapan project and published Carnegie project figurine images in Smith (Reference Smith1971) and Weeks (Reference Weeks2009).

Like censers, human and zoomorphic figurines are scarce in ordinary Mayapan houselots (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Gómora and Hendon2012:Table 1). To emphasize their ubiquity at public buildings, the site's principal pyramid, the Temple of K'uk'ulkan and adjoining colonnaded halls (Q-161, Q-163), had 30 percent of the figurine fragments from a sample (n = 448) of monumental center ceramics (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Gómora and Hendon2012:122). It is doubtful that production of figurines occurred at this temple and hall, as only one mold was present (Table 1). An extensive residential zone test pit program at Mayapan sampled 59 contexts within the city wall, of which only seven yielded figurine fragments. Five horizontally excavated dwelling groups not near the monumental center also had few figurine fragments. Three of these groups had no fragments, one had four figurine sherds, and another house (elite) had one figurine sherd.

How and why figurines came to be deposited at the ceremonial heart of the city is not fully understood. Pilgrimage or other ritual attendances at the monumental center, minimally, involved the use, breakage, and discard of figurines. In addition to the concentration of figurines at monumental center buildings at Mayapan, other clusters occur within mortuary contexts, especially with child burials, as reported by Carnegie Project investigators (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Gómora and Hendon2012:124). Fifty-eight percent of the Carnegie figurine sample (of 101 figurines) is from burials, and 47 of these 59 figurines in burials are from elite residences or monumental zone structures. The Carnegie sample was biased toward upper-status contexts equipped with family tombs, unlike simpler burial pits at ordinary houses (Delgado Kú et al. Reference Delgado Kú, Escamilla Ojeda, Masson, Lope, Kennett, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021; Smith Reference Smith, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962). Jaina Island figurines also tend to be found in mortuary contexts, although this practice is more widespread at Jaina than Mayapan. Figurines were not exclusive to high-status graves at Jaina (Piña Chan Reference Piña Chan1968). Unlike Mayapan, Aztec figurines were recovered more generally in everyday domestic contexts and seem to have been broadly accessible (Smith Reference Smith and Plunket2002:102, Table 9.2).

Halperin suggests that Maya figurines were used in commemorating the life cycles of individuals, including death, and that they also invoked concepts of “monumental time” (Halperin Reference Halperin2017:532–535, see also McVicker Reference McVicker2012). That is, they contributed to enduring transgenerational conceptualizations of self and society, as well as long cycles of state religious practice and belief. Postclassic effigy ceramic caches at Santa Rita, Belize, also likely pertained to calendrical rituals (Chase Reference Chase, Chase and Rice1985, Reference Chase, Sabloff and Andrews V1986; Chase and Chase Reference Chase, Chase, Chase and Chase1992:127). The circulation of people and portable objects, including figurines, represented an important dynamic of placemaking for Maya society, as Halperin (Reference Halperin2014:112, 119) argues for Classic period Maya figurines. Mobile objects, Halperin observes, symbolize connections to the recipients of original owners, owners, or places. Souvenirs, as Halperin notes, are clear examples of this.

It seems likely that for Mayapan, figurines were centrally distributed, perhaps as gifts, at events such as political investiture, rites of passage, period endings, and other ceremonies, as argued for earlier periods by Halperin (Reference Halperin2017:532). Gifts were bestowed, for example, at youthful rites of passage in the northern Maya region at the time of Landa's writing in the 1500s (Landa Reference Landa and Tozzer1941:106). Some gifted figurines may have been broken accidentally at such ceremonies, accounting for the concentrations of finished figurine fragments at edifices such as the Temple of K'uk'ulkan. Alternatively, they may have been acquired and deposited reverentially at ritual events.

The curation of Mayapan's figurines, including broken fragments, is evident, given the recovery of figurines as grave goods. For example, at least three human and three animal figurine heads (Figure 5) were associated with a child interred in an upper-status family tomb at Mayapan's House Q-39 (Delgado Kú et al. Reference Delgado Kú, Escamilla Ojeda, Masson, Lope, Kennett, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021:Figure 5.15). Some figurines, acquired at ceremonial festivities, may have been retained by participating individuals, who transported them to their residences. Individuals may also have obtained figurines via neighborly transactions, either directly from producers or as gifts from patrons or guests participating in mortuary rites. As Walker suggests for effigy censers, figurine heads could also have attracted casual collectors during Mayapan's occupation. A range of possibilities can be imagined, if not reliably tracked, for the movements of figurines.

Clearly, initial views of “household-scale” Postclassic Maya religious practice at Mayapan advanced by Carnegie Institution archaeologists (Pollock Reference Pollock, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962:17; Proskouriakoff Reference Proskouriakoff, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962:136; Thompson Reference Thompson1957:624) were based on a sample of effigy ceramics of higher-status domestic contexts. This model ignored Carnegie Project data that revealed large concentrations of effigies at public buildings compared to dwellings (e.g., Adams Reference Adams1953; Stromsvik Reference Stromsvik1953; Winters Reference Winters1955). Given prior studies of restricted distribution of finished figurines and effigy censers at Mayapan (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Gómora and Hendon2012; Peraza Lope and Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014a), it is perhaps not surprising to discover that their production is largely confined to a limited range of contexts.

ENTITIES PORTRAYED BY EFFIGY CENSERS, FIGURINES, AND MOLDS

The ceramic molds in our sample are fragmentary and have limited potential for identifying the beings whose images they were used to create. Below, we summarize the personages identified in both censer and figurine form at the site and describe entities identified from the molds. To accomplish identifications from some of the better-preserved molds, we made clay impressions from larger mold fragments (Figures 2 and 3).

Effigy Censers

Iconographic meanings of Postclassic effigy censers have been well-explored (Milbrath Reference Milbrath2008; Milbrath and Peraza Lope Reference Milbrath, Lope and Aimers2013; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Aimers, Lope and Folan2008, Reference Milbrath, Walker, Lope, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021; Rice Reference Rice, Rice and Rice2009; Russell Reference Russell2017; Thompson Reference Thompson1957; Walker Reference Walker1990). Molds for effigy censers are limited to the production of facial elements. The remainder of the figures’ bodies were modeled, to which stucco plaster was applied, overlain with paint. Bodies and limbs were built with hollow slabs and tubes. Modeled chest adornments often exhibit twisted or braided clay. Sandals are simple, and headdresses are large and elaborate, with features such as animal heads, jewels, turbans or miters, maize foliage, or feathers. Deity effigies usually hold offerings or other objects, such as birds, serpents, flowers, feathers, jewelry, cacao pods, maize, tamales, shells, and incense (Smith Reference Smith1971:113). Molds helped to replicate desired facial features of old, young, male, female, skeletal, and other personages, providing faces to which distinctive identifiers were added with modeled, appliqued, painted, or carved features, as observed in the examples in Figures 4a–4c.

Mayapan has greater effigy censer frequencies, larger and more elaborate censers, and more diverse personage representation on censers than any other site, and it was the seat of peninsular religion (Peraza Lope and Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014b:427; Roys Reference Roys, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962:50–56). Contemporary towns on the peninsula mostly produced their own censers, as these large and fragile objects were difficult to transport (Milbrath and Peraza Lope Reference Paris, Lope, Shugar and Simmons2013:214; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Walker, Lope, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021:309). Variation at different sites is observed in the relative elaboration and specific traits of faces, eyes, dress, and head gear, with some degree of quality dissipating with distance from Mayapan toward coastal and southern locations (Masson Reference Masson2000:239; Milbrath and Peraza Lope Reference Milbrath, Lope and Aimers2013:215–216; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Aimers, Lope and Folan2008, Reference Milbrath, Walker, Lope, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021:309; Rice Reference Rice, Rice and Rice2009; Russell Reference Russell2017). Mayapan effigy censers portray Chaahk/Tlaloc, Itzamna, old and young female goddesses, Ek Chuah/Whiskered deity, Xipe Totec, the Maize God, a Venus god, an old god, a fire god, a death god, Ehecatl, K'uk'ulkan, diving entities, a Monkey Scribe, and other young male faces lacking attributes of known deities in the Maya codices (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014b:Table 7.4; Milbrath and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Götz and Emery2013; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Walker, Lope, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021:305; Thompson Reference Thompson1957:608–621). At Zacpeten in the Peten Lakes, many of these entities were recognizable, including a female goddess (Ix Chel/Chak Chel), Ek Chuah, a fire god, a diving entity, Chaak/Tlaloc, and young male faces (Rice Reference Rice, Rice and Rice2009:281–284). Sites of northeastern Belize exhibit censers portraying Itzamna, Ek Chuah, Ix Chel, the death god, an old god, Xipe Totec, a diving entity and young male entities (Masson Reference Masson2000:239; Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Walker, Lope, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021:311; Sidrys Reference Sidrys1983). Some effigy censers to the south represent exceptions to the generalization that censers are poorly rendered at a distance from Mayapan. For example, two renditions of Ek Chuah, one from Mayapan and one from Laguna de On, Belize, are identical (Figures 4d and 4e). Likewise, the female faces from Progresso Lagoon are finely portrayed (Figures 4 g and 4h). Two male faces from the same site are asymmetrical, with a comic effect that may well have been intended (Figures 4f and 4i).

Figurines

Female figurines represent around 29.7 percent of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) sample of 448 figurine fragments at Mayapan, with males forming 3.6 percent, and gender unidentified for another 7.1 percent (Table 2, Figure 5). Of the INAH sample, 247 (55.1 percent) represent animals and 20 examples are of unidentified fragments or geometric pieces (Table 2; Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Gómora and Hendon2012). The most common animal figurines are birds (16.1 percent of the INAH sample), many not identified to species, but including parrots, quetzals, eagles, and turkeys. Snakes are also common (17.6 percent), followed by dogs (3.6 percent), deer (3.3 percent), and other mammals, reptiles, fish, or amphibians that occur less frequently (Table 2). Additional figurine identities may be gleaned from Carnegie Project publications (Smith Reference Smith1971; Weeks Reference Weeks2009), as we have previously attempted (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Gómora and Hendon2012).

Female and human figurines also form the majority of the Carnegie Project sample of 101 figurines, with few males represented, and various animals, among which birds and snakes are the most common (Table 2). The Carnegie sample includes seven additional figurines that portray male deities or other distinctive personae, including Itzamna, Ek Chuah, a spear-wielding warrior, a human/zoomorph with a projecting snout, and males standing on the backs of animals (Table 2). Bird and serpent figurines bear close resemblances to aspergillum and headdress adornments associated with deities in Maya codices (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Gómora and Hendon2012:Figures 10–12). However, bird and serpent effigies were often modeled rather than mold-made (Figure 5), making their production localities difficult to discern.

Female figurines at Mayapan display subtle markers of social identity, suggesting their makers rendered images of female ideal types. A common type of female figurine has a slender body, wears a simple tunic (obscuring the legs), with arms extending to the sides of the body; large, circular ear ornaments are common (Figure 5). Their faces are mature, without signs of advanced age. Other human figurines (male and female) that are solid and modeled (not mold-made) exhibit idiosyncratic postures, wear less clothing, and have distinct arms and legs (Figure 5). Differences in female hairstyle or gear include variants of braids or flaring, crown-like turbans, or bands of cloth above the forehead. A few wear their hair pulled back and parted in the middle and some have two buns on top of their heads (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Gómora and Hendon2012:Figures 13–25). The site's figurines sometimes exhibit preserved face or clothing paint; Thompson (Reference Thompson1957) identified one female figurine as the central Mexico goddess, Tlazolteotl. Within the INAH sample, only seven female figurines exhibited protruding bellies suggestive of pregnancy (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Gómora and Hendon2012:Figure 6), and one figurine may reflect a childbirth posture (Figure 5h). At the Postclassic site of Zacpeten, pregnant female figurines were more common (Rice Reference Rice, Rice and Rice2009:292).

Molds

Facial molds represent censers or, rarely, pendants or adornments. Body molds represent figurines. Deities identified from the mold assemblage include Itzamna (God D) or another aged entity, such as a Pauahtun (God N), as illustrated by the censer face mold in Figure 2. Itzamna's elderly facial characteristics include sunken eyes, prominent cheekbones, wrinkles, a nose bridge bump, and, sometimes, fangs (Peraza Lope and Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014b:Figure 7.3; Thompson Reference Thompson1957). Chaahk (God B) is recognized by a long or bulbous nose and fangs; at least one censer face mold in our sample seems to represent him (Figure 3). Ek Chuah (God M), a merchant deity regularly portrayed in Mayapan's effigy censer assemblage, has hollow eyes, sometimes with an elongated, straight nose or a lip plug (Figures 4d and 4e). At least three molds (two censer faces and one figurine) suggest Ek Chuah (Figures 2 and 3). Some merchant god censers at the site exhibit a beard, mustache, or fangs (Peraza Lope and Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014b:Figure 7.4; Thompson Reference Thompson1957:Figures 1e–1f). Young male deities include the Maize God (God E), who can be difficult to identify in cases where he lacks ritual regalia or distinctive dress (Peraza Lope and Masson Reference Peraza Lope, Masson, Masson and Lope2014b:Figure 7.5; Thompson Reference Thompson1957:Figure 2d). Figure 2 illustrates two young male censer faces, one of them a miniature, perhaps an adorno for a larger censer. Effigy ceramic variants include miniature, perforated masks or deity heads (such as skull bonnets) that were attached to the regalia worn by the principal censer personage (Smith Reference Smith1971:111). The young female goddess, known by various names in Maya literature (Vail and Stone Reference Vail, Stone and Ardren2002), is suggested by the parted hair along the forehead of a censer face mold in Figure 3 (bottom left). An additional female figurine mold is illustrated by a torso fragment in Figure 3 (bottom right) that resembles finished examples in Figures 5f and 5g. Two figurine mold examples represent small zoomorphic images, perhaps a spider monkey with bulging eyes, long limbs, and a pot belly (Figure 3), and a coatimundi with round ears and a snout (Figure 2). Both molds are in a bipedal position and exhibit a playful demeanor. The entities portrayed by finished Mayapan figurines are more fully explored by Masson and Peraza Lope (Reference Masson, Lope, Gómora and Hendon2012).

MAYAPAN'S EFFIGY CENSER AND FIGURINE PRODUCTION CONTEXTS

The greatest concentration of molds was at House Q-40a, to the east of and adjacent to the monumental center (Table 1, Figures 6 and 7). Other mold concentrations come from the site's central public buildings and, occasionally, from ordinary houses in the settlement zone (Table 1).

Figure 6. (a–b) Effigy censer mold and (c) broken mold-made face from (d) House Q-40a. (a–c) Photographs by Masson; (d) photograph by Miguel Delgado Kú, courtesy of the Proyecto Económico de Mayapán.

Figure 7. Location of structures Q-39, Q-40a, and elite platform Q-41, and nearby structures and houselot boundary walls at Mayapan. Modified by Masson from Hare (Reference Hare, Marilyn A., Lope and Hare2008:Figure 2.3).

House Q-40a and its Neighbors

House Q-40a was fully excavated in 2009 and it fits expectations of an attached artisan dwelling (Cruz Alvarado et al. Reference Cruz, Wilberth, Lope, Cobá, Masson, Masson, Lope, Hare and Russell2012; Delgado Kú Reference Delgado Kú, Masson, Lope, Hare and Russell2012). Its size (22.5 sq m) is within the range of commoner dwellings for the site, and it was situated at ground level, next to the platform of one of the largest elite residential complexes at the site, Group Q-41 (Figures 6 and 7). House Q-40a's association with the elite group is underscored by the fact that both features are located within the same albarrada (houselot wall) enclosure (Figure 7). Molds represent the primary evidence for Q-40a's identification as a workshop (Figures 2 and 8), along with a high density of censer sherds representing broken debris from the manufacturing process (Figure 6c). Next to elite group Q-41 and House Q-40a, House Q-39 was situated within its own walled enclosure (Figure 7); its occupants were quite wealthy and may have been related to the residents of Q-41. The family at Q-39 engaged in craft activities, including, perhaps, figurines, but not effigy censers, as well as fine chert tools, shell, and metal objects (Masson et al. Reference Masson, Hare, Lope, Escamilla Ojeda, Paris, Kohut, Russell and Alvarado2016:Table 1). A total of 30 figurine fragments were recovered from Q-39, but only one mold was present (Table 1). Both houses (Q-40a and Q-39) were also associated with copper bell production (Paris and Cruz Alvarado Reference Paris, Cruz Alvarado, Masson, Lope, Hare and Russell2012). A human bone spindle whorl from Q-40a suggests the fabrication of symbolically important cloth (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014b:Figure 6.7).

Figure 8. Distribution of effigy censer and figurine production debris at house Q-40a, Mayapan. Shaded areas indicate excavated areas of the house. Maps by Masson.

Pedestal vases, which are attached to and support standing effigy figures and hold incense cones (Figures 4a and 4b), are missing in the sherd assemblage from Q-40a. The artisans working at this dwelling concentrated on the most highly skilled aspects of effigy censer production—the molding, modelling, plastering, and painting of effigies. Pedestal vase portions were made elsewhere, presumably by potters living nearby. A central burial cist within House Q-40a contained the graves of two superimposed adults, accompanied by a plastering tool, a piece of red pigment, a copper bell, and a whistle figurine (Masson et al. Reference Masson, Hare and Lope2014:Figure 5.32). The grave goods correspond to the artisanal pursuits documented at the residence.

Structure Q-40a was identified as an effigy censer workshop by the presence of 11 censer face mold fragments, five figurine molds, and six additional mold fragments of either censers or figurines (Table 1). The molds at Q-40a were recovered from seven different 2 × 2 m excavation units around the house. Four of these seven units had from three to five molds per cubic meter (Figure 8). The distribution of broken fragments of molded effigy censers or figurines ranges from 4 to 131 sherds per cubic meter around the house and they were recovered in 21 different grid squares, with four hotspots of 64–131 sherds per cubic meter (Figure 8). Square 9-A (behind the house) has concentrations of molds and effigy censer sherds, indicating a favored location for discarding manufacturing debris. Mold storage is suggested by another concentration within at least one interior space of the dwelling (Figure 8). A vase for mixing fine plaster was also found at this house; such stucco covered the clay surface of effigy faces and bodies, which were subsequently painted.

Totally, 66 figurine fragments found at Q-40a are considered to be manufacturing failures. Other special ceramics may have been made at this dwelling. The distribution per cubic meter of ladle censers and special pottery (miniature cup or vase fragments) overlaps with that of molds and figurine or whistle fragments. In four (2 × 2 m) grid squares at Q-40a, all these forms were recovered and at least two forms co-occur in eight other squares. Figurines or whistles range in density from 1 to 33 per cubic meter and are spatially distributed in 11 (2 × 2 m) grid squares. Three of four squares with the densest figurine fragments overlap with the units where the most censer fragments were discarded (Figure 8). The densest production debris zones in and around House Q-40a were in midden deposits that also contained abundant quotidian artifacts typically found in domestic settings at the site.

Censer and figurine production was a low-volume industry, with effigy ceramic sherds (Chen Mul Modeled) making up only 3.3 percent of the total ceramic sherd assemblage for Q-40a (Cruz Alvarado et al. Reference Cruz, Wilberth, Lope, Cobá, Masson, Masson, Lope, Hare and Russell2012:Table 15.20). However, this proportion is high compared to lower percentages of Chen Mul Modeled at other fully excavated craft specialist dwellings, 0.06 percent at House I-55 and 0.7 percent at House Q-176, where two mold fragments were recovered (Table 1; Cruz Alvarado et al. Reference Cruz, Wilberth, Lope, Cobá, Masson, Masson, Lope, Hare and Russell2012:Tables 15.12 and 15.16).

This pattern of dense discard zones, located amidst a more widely distributed sheet midden within walled houselots, is typical for Mayapan workshops. We cannot rule out the possibility that artisans at Q-40a also made ordinary vessels alongside effigy ceramics. The proportions of ordinary vessel forms from this house resemble those of House Q-176, home to potters who made surplus dishes, ollas, and bowls (and, less frequently, molded figurines). Potters at Q-176 made a variety of common forms found at houselots across the site. Identifying the ceramic-making livelihood at Q-176 was facilitated by extraordinarily high sherd densities, as well as caches and grave goods featuring stores of potting pigments (Delgado Kú et al. Reference Delgado Kú, Escamilla Ojeda, Masson, Lope, Kennett, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021:Figure 5.16; Masson et al. Reference Masson, Hare, Lope, Escamilla Ojeda, Paris, Kohut, Russell and Alvarado2016).

Monumental Center and Residential Zone Production Contexts

The remaining molds in the sample are primarily from colonnaded halls, custodial houses, temples, and oratories, often distributed at pairs of such buildings in the site center. Artisanal goods were likely made at these localities for use by the political and priestly nobility. The custodial house is a distinctive feature of Mayapan's monumental center, with key implications for understanding patronage of artisans at the site (Delgado Kú et al. Reference Delgado Kú, Escamilla Ojeda, Masson, Lope, Kennett, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021). Physically, they resemble small commoner-size houses from across the site, but they differ in that they are disembedded from the residential zone and are located adjacent to epicentral halls and temples. The occupants of these houses engaged in artisanal pursuits (e.g., Paris Reference Paris2008), and these production activities link central custodial houses with each other and with Q-40a. There is little evidence pointing to priestly occupations for residents of custodial houses, but their spatial proximity to monumental edifices suggests they might have served as guardians, in addition to crafting.

Aside from House Q-40a, 28 architectural contexts yield 92 additional effigy censer or figurine molds from the site's monumental center and settlement zone (Table 1, Figures 2–3 and 9–11). Three of the 28 buildings have only one fragment for which mold identification is uncertain (Q-163, Q-61, Q-55). The presence of a single mold provides an insufficient basis to confirm (or deny) effigy ceramic-making activities at these localities. Two contexts (Q-57, Q-66) had a single Classic period figurine mold and are excluded from this analysis. Nineteen of the 28 localities have only one or two mold fragments and it is unclear whether these molds reflect ongoing, onsite effigy ceramic production. However, some contexts with few molds (AA-78, BB-12, P-146) were not fully excavated, but were instead explored via test pit samples that yield less conclusive results with respect to production scale. Nine contexts have three or more molds; of these, seven have from three to eight molds, and two individual buildings (Q-99, Q-54) stand out for their ubiquity, with 15 and 20 molds, respectively. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate examples of molds recovered from monumental center buildings.

Figure 9. Mold distribution at Mayapan's monumental center. Map by Masson and Russell, modified from Delgado Kú (Reference Delgado Kú2004) and Proskouriakoff (Reference Roys, Pollock, Roys, Proskouriakoff and Smith1962).

Figure 10. Photographs of selected structures in the monumental center of Mayapan associated with effigy ceramic production. Photographs by Pedro Delgado Kú.

Figure 11. Location of molds found in the residential portion of the walled city of Mayapan. Modified by Masson from original map courtesy of Timothy S. Hare.

Halls Q-54 and Q-99 are located, respectively, on the west and east edges of the monumental zone (Figures 9 and 10). Oratory Q-140 and Temple Q-141 (with eight and six molds, respectively) are located just to the south of Hall Q-99 (Figures 9 and 10). Where the type of mold could be determined, both figurine and effigy censer molds were recovered from a limited number of contexts in the monumental center (Q-54, Q-99, Q-141) and in the residential zone (R-106 palace and Q-40a, as discussed). Eight contexts in Table 1 had identifiable figurine molds, while 11 contexts had effigy censer molds, and 31 molds in the sample could not be identified to type (Table 1).

The 14 molds combined from Temple Q-141 and its adjacent oratory (Q-140) represent an additional significant concentration (Delgado Kú et al. Reference Delgado Kú, Escamilla Ojeda and Lope2012; Peraza Lope et al. Reference Peraza Lope, Kú, Ojeda and Alvarado2008). This sample includes female figurines (Figure 3). Another pairing of edifices with molds includes Hall Q-99 and its attached (rear) custodial house Q-86 (Figure 10), which together yielded 18 molds. It is noteworthy that outside of the monumental center, one context with three molds (one figurine, two censers) was elite palace group R-106. Elite house R-183b, impressively constructed, also had two molds, and two smaller elite dwellings each had one mold (Q-39, S-132). Table 1 lists other monumental center or residential zone contexts with few molds, including the modest commoner houselots of BB-12, P-146, R-112, AA-78, P-146, Q-176 (a crafter house that made several other types of products), and Z-42 (next to a public monumental group and sacbe terminus, Z-50). Custodial House Q-92, which had figurine molds, is located behind burial shaft Temple Q-95. The residents of this house group were also engaged in metallurgy (Paris Reference Paris2008). Custodial House Q-86, with five molds (Table 1) is the only custodial abode physically attached to a public building (Hall Q-99) at the monumental center (Figures 9 and 10). A cluster of custodial houses (Q-57, Q-56, Q-67) to the south of Temple Q-58 were making effigy censers (Figures 9 and 10).

Do the molds recovered from the monumental center's public buildings derive from activities at adjacent custodial houses? Although this is possible, in some cases there are more molds at the public buildings than at the nearby dwellings—for example, Hall Q-99 has 15 molds, and its custodial house, Q-86, has five molds. If mold fragments originate from custodial houses, one might expect higher frequencies at the original contexts. However, a range of processes could account for the movement of mold fragments across adjacent buildings.

DISCUSSION

In one respect, the effigy censer and figurine mold distributions parallel patterns of onsite production at monumental center buildings previously observed for stone and bone tools, spindle whorls, food preparation and storage vessels, faunal remains, and manos and metates (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014b:Tables 6.4 and 6.5). These findings suggest ritual preparations, including crafting and the full butchering of animals destined for sacrifice or feasts (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Götz and Emery2013:273). Such onsite preparations represented key contributions to ritual economies elsewhere in the Mesoamerican past (Cyphers and Hirth Reference Cyphers, Hirth and Hirth2000) and continue in the region today (McAnany Reference McAnany2010:134, 216).

Figurine and effigy censer production in the monumental center involved an interesting class of people at Mayapan, the occupants of custodial houses. Along with House Q-40a's location within an elite residential group's houselot enclosure wall, clearer cases for spatial “attachment” of producers are hard to imagine. Metallurgical work, we now know, was practiced by attached artisans, as well as by elites living at finely built house groups, such as R-183 (Paris and Peraza Lope Reference Paris, Lope, Shugar and Simmons2013). Metallurgy was the first restricted and/or attached industry identified at Mayapan, and the musicality of bells made them ritually important in Mesoamerica (Hosler Reference Hosler1994). Effigy ceramic production by attached artisans expands our understanding of the importance of making symbolically charged artifacts.

Such artisans would have had patronage relationships with the burgeoning class of priests and political families responsible for constructing, maintaining, elaborating, and hosting events at the city's monumental buildings. At least two graves at artisan houses include offerings pertaining to the crafts they practiced in life (Delgado Kú et al. Reference Delgado Kú, Escamilla Ojeda, Masson, Lope, Kennett, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021; Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014a:Figure 5.32). The midden assemblage from House Q-40a reveals a standard of living equivalent to independent, affluent crafter house groups in the city. Crafters at Mayapan had more ubiquitous and diverse artifact assemblages, including nonlocal goods, compared to commoners who did not make surplus craft goods (Masson and Freidel Reference Masson and Freidel2012; Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014b; Masson et al. Reference Masson, Hare, Lope, Escamilla Ojeda, Paris, Kohut, Russell and Alvarado2016).

While this article identifies concentrated production and use of figurines and effigy censers at or near public buildings or high-status residences, effigy ceramic molds are also occasionally recovered at ordinary, outlying houses in the residential zone. Their recovery at independent (unattached) houselots implies that restriction of production was not rigidly enforced. However, for a large proportion of the city's residents, household ritual did not involve the making mold-made effigies or keeping effigy censers or figurines within the dwelling.

Interpreting the use and meaning of figurines is notoriously difficult (Lesure Reference Lesure2011), but the primary use contexts of Mayapan's effigy ceramics link them to state religion. An interesting parallel case in Mesoamerica is the identification of a censer-making workshop in Teotihuacan's citadel (Múnera Bermúdez Reference Múnera Bermúdez1985; Sugiyama Reference Sugiyama2002). Effigy censers, made for a suite of complex calendrical celebrations and destined for the city's many shrines, temples, and colonnaded halls, were commissioned by and used by elites. Sponsoring calendrical ceremonies equated to carrying the burdens of time and was a sought-after honorific in Contact as well as late pre-Columbian times (e.g., Love Reference Love1994; Rice Reference Rice2004:111–115; Roys [1933] Reference Roys2008:86, 95–112; Walker Reference Walker1990:405). Figurines, likely made for and distributed at state events, circulated in a way that most often resulted in their redistribution in ritual contexts (public or mortuary).

CONCLUSIONS

We identify the sponsored, attached production of effigy censers and figurines at Mayapan and summarize data regarding the restricted, though divergent distribution and use contexts of these two classes of artifacts. In so doing, we note that Mayapan, like earlier Classic period centers of its past, had a complex economy. Although the Postclassic period is better-known for the scale of its commercial exchange, reflected by household choices to furnish dwellings with nonlocal goods made by others as part of their daily inventories, effigy censers and figurines were not part of the market economy. Lords and priests of this city, like the nobility of earlier centuries, sponsored talented artisans to make objects used in the promotion of and participation in state religion. The pattern of restricted production and consumption for certain artifacts is clear, but it is not absolute. This is true for other luxury or special-purpose industries in Mayapan. Only elites or attached specialists made copper artifacts (Paris and Peraza Lope Reference Paris, Lope, Shugar and Simmons2013), and while metal artifacts are concentrated in elite mortuary contexts, they occasionally grace commoner domestic assemblages (Masson and Peraza Lope Reference Masson, Lope, Masson and Lope2014b:411–412; Paris Reference Paris2008).

Figurines provided greater numbers of people with the opportunity to acquire and use effigy ceramics, while effigy censers were reserved for occasions of the most solemn and exclusive ritual import. The Mayapan case is interesting, given its differences with Postclassic central Mexico, where figurines were made by independent crafters at places such as Otumba, who sold them into Aztec market networks (Charlton et al. Reference Charlton, Nichols and Charlton2000). Aztec figurines were destined for residential use in practices such as midwifery and curing (Smith Reference Smith and Plunket2002). Confounding our findings is Landa's (Reference Landa and Tozzer1941:129) testimony that sixteenth-century Maya women indeed put female effigies (“the idol of a goddess called Ix Chel”) under their beds to help mitigate the risks of childbirth, and he also writes that these objects formed part of physicians’ medicine bundles (Landa Reference Landa and Tozzer1941:154). These references suggest they should be more commonly recovered at Mayapan's domestic contexts. Perhaps, however, such figurines were carefully curated and/or discarded, or used temporarily during a midwife's attendance at a birth. In any case, our results suggest that these effigies were not ordinarily made or owned by commoners.

We thus observe that goods produced in restricted contexts have restricted circulation. Mayapan's elites controlled and patronized artisanal production in similar ways to those proposed for early Classic Maya courts. Our findings support the idea of a relatively exclusive sphere of circulation for effigy ceramics that was outside of the realm of market exchange. Effigy censers were more restricted in use than figurines, and these two artifact classes existed along a continuum of elaboration that, at times, portrayed overlapping entities with greater (effigy censer) and lesser (figurine) degrees of embellishment. Non-effigy censers may be considered part of this continuum of symbolically meaningful, embellished ritual pottery. Representing decorated pedestal vessels with appliqué motifs, non-effigy censer vases also held cones of copal, as did the pedestal vases attached to effigies (Milbrath et al. Reference Milbrath, Walker, Lope, Masson, Hare, Lope and Russell2021:311; Rice Reference Rice1999). Non-effigy censers may have been more accessible to devout Postclassic families of lesser status. Although uncommon at Mayapan houselots, they exist in greater frequencies (n = 62, 0.25 percent of all sherds) than effigy ceramic sherds (n = 16, 0.06 percent)—for example, at House I-55. Non-effigy censers are also common in assemblages of northeastern Belize (Masson and Rosenswig Reference Masson and Rosenswig2005; Walker Reference Walker1990), as well as in Zacpeten (Rice Reference Rice, Rice and Rice2009), attesting to important differences in ritual practice from place to place.

Effigy censer and figurine making were geared toward overlapping, yet different ranges of intended use, with the former more restricted than the latter. These findings suggest a complex set of linking, intermediate practices binding objects, ritual participation, and people from different sectors within the city. This examination of effigy ceramic production sheds light on one dimension of Mayapan's economy that existed apart from market exchange and recalls long-term traditions of elite patronage of artisans in the region.

RESUMEN

Los contextos espaciales de incensarios efigie y moldes de figurilla en Mayapán, Yucatán, México sugieren una industria bien controlada en la que representantes de la élite del gobierno estatal y órdenes religiosas ejercieron la supervisión sobre la producción y distribución. Artesanos adjuntos en Mayapán produjeron estos y otros bienes restringidos para residentes de palacios y patronos de los edificios públicos de la ciudad. El estudio de la producción de cerámica efigie revela que como reinos mayas anteriores del período clásico, las élites postclásicas también patrocinaron la elaboración de bienes cargados simbólicamente. Este hallazgo amplía la comprensión de la organización económica del período postclásico, que es mejor conocido por su intercambio de mercado regional expansivo. La distribución limitada de incensarios efigies y figurillas atestigua aún más su uso principal en el contexto de ceremonias patrocinados por el estado y, en un grado menor, en el contexto de ocasiones funerarias de alto estatus. A diferencia de otros lugares y épocas de Mesoamérica, ni las figurillas ni los incensarios efigie son representativos de la práctica religiosa a escala doméstica para la mayoría de los residentes urbanos de Mayapán.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research at Mayapan has been generously supported by Mexico's Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia and by the National Science Foundation (NSF-BCS grants 1406233, 0742128, 010946, 1406233, and 1144511), the National Geographic Society (grants 8598-08, 193R-18), and grants from the University at Albany – SUNY's College of Arts and Sciences and Department of Anthropology.