Introduction

Two-photon microscopy (2PM) provides three-dimensional (3D) and four-dimensional (4D) (x, y, z, t) imaging in living specimens or under experimental physiological conditions very close to live. In conjunction with fluorescent labels, 2PM provides a powerful means of investigating the relationships between structure and function at the microscopic level that are key to understanding biological systems [Reference Diaspro1]. This technique is able to provide time-resolved, 3D images of dynamic systems with near-diffraction-limited resolution and highly specific structural contrast [Reference Ronneberger2].

Two-photon microscopy occupies a clearly defined position relative to other microscopies used in life science applications. As a light microscopy, it will never approach the pure resolving power of electron microscopy; however, electron microscopy cannot duplicate 2PM's ability to observe living specimens. As an aside, there is considerable interest within the life sciences community in combining the specific localization capabilities of fluorescence microscopy with the high resolution of electron microscopy in a technique known as correlative microscopy. Atomic force microscopy and other scanning probe microscopies also offer very high resolution, but they are surface techniques that lack 2PM's ability to look beneath the surface within living systems. The comparison of 2PM with confocal microscopy, another widely used 3D technique, is more subtle, because the two approaches are related in many aspects of their optical design. Two-photon microscopy is ultimately distinguished from confocal by greatly reduced scattering of the illuminating and fluorescing light, which allows it to image structures deeper within live specimens [Reference Helmchen and Denk3].

Fluorescence Microscopy

Unlike conventional light microscopes, which create images from light reflected from or transmitted through the specimen, fluorescence microscopy requires a sample that fluoresces. That fluorescence emission may be native to the sample, or it may be introduced by various labeling techniques. The underlying key principle of this method is the Stokes shift between the excitation and emission wavelengths, which enables the use of dichroic beam splitters to separate the fluorescence from the excitation light. As a result, only objects that actually emit fluorescence will be detected [Reference Lichtmann and Conchello4].

The beauty of fluorescence microscopy lies in the existence of several specific labeling techniques. Because of the specificity of the labeling, it is possible to image only the desired cellular components. There is a steadily increasing number of labels available for all kinds of purposes, samples, and cellular structures. Some of these use artificial dyes coupled to antibodies, whereas other techniques modify the cells in such a way that they produce the label by themselves [Reference Miyawaki, Sawano and Kogure5]. In the latter, the genetic sequence that codes for the fluorescent protein is inserted into the gene that codes for the protein of interest, thus allowing the investigator to identify and visualize metabolic activity related to that molecule and associated cellular structures.

Confocal Fluorescence Microscopy

Confocal microscopy is a widely used technique that shares with 2PM the ability to capture 3D/4D images of biological systems and is thus the technique to which 2PM is most frequently compared. Many early 2PM microscopes were modified confocal microscopes. In a confocal microscope, illumination from a point source (originally a pinhole aperture in front of a conventional light source but now more frequently a laser) is focused by the objective lens to a point in the object plane. Another pinhole aperture, in front of the detector and confocal with the illumination aperture, excludes light originating above or below the object plane within the sample. By scanning the beam (using some combination of beam, sample, and optics movement) through a volume within the sample, data are collected point-by-point in a 3D array that can be reconstructed to reveal structures within the specimen.

Laser scanning confocal microscopes (LSCM) scan a single beam through the sample volume. Spinning disc confocal microscopes (SDCM) greatly increase the speed of the technique by scanning and collecting signals from multiple beams simultaneously. SDCM is especially suitable for live cell imaging, because it is much gentler to living specimens compared with conventional LSCM. The name of the technique derives from the spiral array of confocal lenses or apertures located on a spinning disc and used to create the multiple beams. SDCM systems are particularly valuable in live specimen applications because their speed allows them to capture dynamic events with very high time resolution, depending on the application and the sample conditions (how fast is the CCD, how bright is the sample, what laser power is available) [Reference Wang, Babbey and Dunn6]. Under optimal circumstances, up to several hundreds of frames per second are possible.

Confocal microscopy is useful for delivering 3D images of relatively thin specimens. However, its performance degrades rapidly with increasing thickness or depth below the sample surface. The UV to visible light required to excite the fluorescent labels and the visible light they emit are both strongly scattered by typical biological specimens. For example, the average distance between scattering events in fixed brain tissue is less than 50 to 100 μm for excitation with 630 nm light [Reference Helmchen and Denk3]. In a confocal microscope, only unscattered illumination and emission light contribute to (meaningful contrast in the final image. In addition, scattered illumination photons can generate diffuse fluorescence that reduces S/N ratios and causes photobleaching and phototoxicity. Thus, confocal images lose intensity and contrast rapidly at depths greater than a few tens of microns.

Two-Photon Excitation Fluorescence Microscopy

Multiphoton excitation (we consider here only the two-photon case) is a non-linear phenomenon exploited to provide 3D resolution in 2PM. Two lower-energy photons absorbed simultaneously (within ~10−18 seconds) can combine their individual energies to raise a fluorophore to its excited state, leading ultimately to fluorescent emission. Similar to confocal microscopy, in 2PM the light source is focused to a small spot within the sample, and this spot is scanned through a 3D volume [Reference Helmchen and Denk3]. The likelihood of two photons arriving at a fluorescent marker sufficiently close in time to induce fluorescence depends on the intensity of the light—specifically, the square of the intensity. In addition, the intensity within the beam decreases with the square of the distance above or below the focal plane, making the overall likelihood of excitation and fluorescence a function of the fourth power of distance from the focal plane. Thus, the region within which two-photon excitation can occur is intrinsically limited to a sub-femtoliter (10−15 liter) volume centred at the focal point of the beam (Figure 1) [Reference Xu7]. That the signal from this excitation can be detected from relatively deep within the specimen gives two-photon microscopy a significant combination of advantages compared to other light microscopy methods (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Comparison of excitation regions. Single-photon excitation with the classic double cone of a focused 488 nm beam (left). Two-photon excitation using an IR pulsed laser exhibits a much smaller focused spot (right). The sample is a dilute fluorescein solution in a quartz cuvette. Insets show magnified images of the excitation regions. (Courtesy of Dr. Steven Ruzin, University of California Berkeley.)

Figure 2: Microscopy techniques for 3D/4D live cell imaging. Comparison of four different techniques for capability in axial resolution (RES), speed (SP), cell viability (CV), and depth of penetration (DP). A “perfect” system would yield a full square.

Two-photon microscopy enjoys several advantages over single-photon excitation confocal microscopy, mostly related to the longer wavelength IR light used for excitation (compared to the UV-to-visible light used) [Reference Helmchen and Denk3]:

• Fluorescence is confined to the small region at the focal point. Individual photons in the illuminating beam cannot degrade resolution by exciting fluorescence above or below the focal plane [Reference Brown7, Reference Xu8].

• IR light is less strongly absorbed and scattered by biological tissues and so can penetrate more deeply. Imaging at depths up to 1 mm are possible, sufficient to cover the entire thickness of gray matter in mouse neocortex (Figure 3) [Reference Oheim9].

• Scattered IR photons cannot generate fluorescence individually and have almost zero likelihood of combining with another photon for two-photon excitation.

• Photodamage and photobleaching are confined to the immediate region of the two-photon excitation.

• Absorption spectra for the two-photon excitation are usually broader than the single photon equivalents, permitting excitation of several different fluorophores simultaneously at one fixed excitation wavelength (Figure 4) [Reference Bestvater10].

• Greater separation between absorption and emission spectra permits use of filter systems with broad bandwidth and good separation characteristics (Figure 4).

• The elimination of the confocal detector pinhole greatly simplifies signal collection and detection efficiency. The signal need not be routed back through the optical system. All fluorescence originates from the two-photon excitation volume and should be added to the useful signal (compare Figures 5a and 5b).

Figure 3: Projection of a 3D image stack of mouse neurons expressing YFP, recorded in vivo ~200 μm below the brain surface. The false colors give the relative depth, close to the lens (white-yellow) and far from the lens (blue). Note the clear display of dendritic spines (examples are marked with arrowheads), indicating the image resolution. (Courtesy of Sabine Scheibe BIZ, Munich, Germany, 2010; recorded with a TILL Photonics Intravital2P two-photon microscope.)

Figure 4: Absorption spectra (single-photon and 2-photon) and the fluorescence emission spectra for Alexa568 (data from www.spectra.arizona.edu) together with a filter set suitable for this dye. For excitation a 780 nm laser (magenta) was used. The resulting emission photons were reflected by the beam splitter toward the detection system.

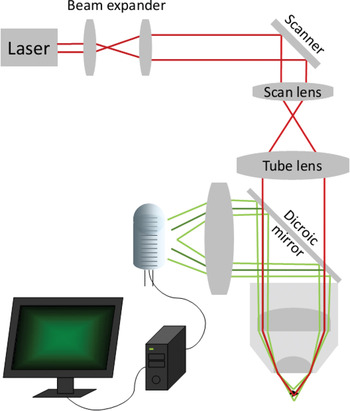

Figure 5a: Schematic drawing of the light path in a two-photon microscope. Unlike confocal microscopy (Figure 5b), fluorescence excitation is confined to the focal spot, so there is no need for a confocal pinhole. Fluorescent light is collected with a collecting lens and a large detector tube positioned close to the back aperture of the objective.

Figure 5b: Schematic drawing of the light path in a confocal microscope. High-energy laser light (blue) is focussed by the objective to a focal spot within the sample (arrow), causing dye molecules to fluoresce. Fluorescent light travels back through the microscope (green rays), until it reaches the confocal pinhole. Fluorescent light that does not originate from the focal spot cannot pass the pinhole and be detected.

System Design Details

Several practical considerations enter the design of a 2PM system and distinguish it from its confocal relatives, including choices for excitation light source, beam scanning, and signal collection (Figure 5a). Although the history of 2PM begins with a 1931 doctoral dissertation by Maria Goeppert-Mayer [Reference Göppert-Mayer11] describing the theory of two-photon quantum transitions, practical implementation had to await the development of laser-based light sources with sufficient intensity in the 1960s and 1970s. Still, the technique didn't really take off until the 1990s when mode-locked infrared lasers became commercially available. Titanium sapphire (Ti:Sa) lasers are now widely used for their tunability and output power, however they are costly and complex. Most 2PM biological applications are limited by photodamage, so high output power is not typically used, and the broadened absorption spectra of fluorophores for two-photon excitation reduces the value of tunability. Recently, simpler and less costly erbium-doped fiber lasers with more moderate power levels have demonstrated their value in 2PM applications. They operate at a fixed wavelength of 780 nm, adequate for most commonly used fluorophores (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

Figure 6: Probability of two-photon excitation fluorescence of many common dyes dependent on the laser wavelength. Data are plotted as cross section (measured in G|f-ppert-Mayer units [GM]), which is directly proportional to the likelihood of a given dye molecule to fluoresce under illumination with the given laser wavelength. Note that, as opposed to single-photon absorption spectra, the spectra are very broad. The dashed red line at 780 nm marks a wavelength that is suitable for excitation of many different dyes.

Figure 7: Mouse brain slice stained with DAPI (green, stains all nuclei) and Alexa647 (red, immuno-staining for BRDU). Both dyes were excited simultaneously with a 780 nm fiber laser at 10 mW. Separating the fluorescence from these dyes into two color channels was achieved by filtering. Image recorded on TILL Photonics Intravital2P two-photon microscope. Under single-photon conditions, one would have needed two separate lasers to excite these dyes.

Scanning speed, resolution, and range have been greatly improved by the latest generation of low inertia galvanometric scanners. These offer flexibility in the definition of the scanning parameters, as well as the speed required to capture time-resolved images. They also reduce phototoxic effects in long-term in-vivo imaging experiments. One of the most important advantages of 2PM is its ability to image effectively, at low light levels and with improved signal-to-noise ratios, deep within highly scattering tissue (Figure 8). Because of the nature of the two-photon excitation, cell toxicity is greatly reduced compared to conventional LSCM, leading to improved dynamic measurements in live specimens. These advances derive primarily from enhanced signal collection efficiency. Because it is not necessary to route the fluorescent light through a confocal detector pinhole, the collection system can be designed to take advantage of every available fluorescent photon—even scattered photons that seem to originate from different focal planes. Those photons would be blocked in the case of LSCM or SDCM.

Figure 8: Crayfish tail muscle stretch receptor neuron, FITC-immunostained for tubulin. Ten optical sections from a 435 μm × 305 μm × 50.5 μm 3D image stack. Optical sections shown are 5 |gmm apart. Image is false-color coded to enhance visibility of faint, dark structures. (Sample from Mikhail Kosolov, Southern Federal University, Rostov-on-Don, Russia.)

Conclusion

Two-photon microscopy can provide time-resolved, 3D images of dynamic systems, with near-diffraction-limited resolution and highly specific structural contrast. It has become a mainstay of many life science laboratories, occupying a clearly defined position complementary to electron microscopy, scanning probe microscopies, and confocal fluorescence microscopy. Its particular strength is the imaging of living specimens to depths as great as 1 mm, offering researchers a new means to investigate dynamic structure-function relationships at the microscopic scale.