The National Health Service (NHS) Plan (Department of Health, 2000) set out an intention to establish 335 crisis resolution and home treatment teams in England by 2004, with the expectation that bed usage in acute adult general psychiatry could be further reduced (Reference Joy, Adams and RiceJoy et al, 2001). The initiative also aimed to make generally available a more acceptable and appropriate model of care, including ‘interventions aimed at maintaining and improving social networks’ (Department of Health, 2001b : p. 16).

The work of these teams is usually characterised as diverting care away from admission beds (Reference BrimblecombeBrimblecombe, 2001). However, enabling early discharge, when admission has not been avoided, can also be part of their routine remit.

This article emerged from the experience of one crisis resolution team receiving in-service training in social systems intervention and crisis resolution. The team asked for something to refer to, in the way of a practical ‘how to do it’ guide, supplementing theoretical instruction and complementing otherwise invaluable on-the-job training. As in-patient wards review their working practices and align themselves with crisis resolution teams (Department of Health, 2002a ), this guide also serves as an introduction for ward staff to the relevance of social context when providing in-patient care. Furthermore, it is anticipated that this overview will be of interest to generic community mental health teams (Department of Health, 2002b ), specialist assertive outreach teams (Department of Health, 2001a ) and early-intervention teams (Department of Health, 2001c ) and to approved social workers performing assessments under the Mental Health Act 1983 (Reference DunnDunn, 2001).

The theoretical background (Reference CaplanCaplan, 1964, Reference Caplan1974; Reference PolakPolak, 1967, Reference Polak1970) and practical procedures (Reference FishFish, 1971; Reference PolakPolak, 1971a , Reference Polak1972) brought together here were first explored and established 30 and more years ago. One of the earliest mobile psychiatric emergency services was set up in Amsterdam 70 years ago, with the aim of preventing hospitalisation (Reference QueridoQuerido, 1968). As community psychiatry has developed, the relevance of social context in general (Reference CohenCohen, 2000), and crisis intervention in particular (Reference HoultHoult, 1986; Reference RosenRosen, 1997; Reference Minghella, Ford and FreemanMinghella et al, 1998; Reference Joy, Adams and RiceJoy et al, 2001), in providing acute psychiatric care has remained crucial. Certainly, clinical experience in setting up and running current crisis resolution and home treatment teams endorses the continuing relevance of social systems intervention when resolving crises in acute mental health care.

Terminology and theory

‘Crisis’ implies here a failure in adequate coping (Reference Minghella, Ford and FreemanMinghella et al, 1998) associated with an acute episode of mental illness or distress. When the individual's resources and the existing support from others have been exhausted and, conventionally, admission to hospital is indicated, the term ‘referral crisis’ is appropriate. Reference CaplanCaplan (1964) more generally defined crises as brief, non-illness responses to stress (Box 1). Thus, a crisis is not a clinical disorder, although the one can cause the other. Equally, stress is not a crisis, although it might provoke one. An emergency is more than a crisis and it requires a different type of response.

Box 1 Crises

Non-illness, brief reactions to stress

Feature adaptive or maladaptive coping

Involve individuals and social systems

Increase accessibility for help

Can occur in connected series

‘Crisis intervention’ (Box 2) is characterised by rapid response and intense, short-time work, in the ‘here and now’ (Reference WaldronWaldron, 1984). It usually involves working with social networks. Intervention should be aimed at detecting maladaptive responses – denial of difficulty, failure to express feeling, avoidance of help – in order that help can be provided and healthy coping facilitated. Most such intervention is not the province of psychiatry (Reference RosenRosen, 1997).

Box 2 Crisis intervention

Rapid response offered in situ, rather than elsewhere

Intense, ‘here and now’, short-term

Usually not by mental health services

Facilitates ‘healthy coping’

Usually involves social networks

Several crises might have been involved in the process leading to a referral for possible in-patient care: admission itself can represent a social systems crisis (Reference PolakPolak, 1967). The referral crisis that precipitates contact with a crisis resolution team may be the end result of a series of unresolved crises in more than one social system. For intervention to be appropriate it is important to be able to identify and describe each crisis clearly.

The predicament of the individual can thus be understood within a broad social network. This network has been described as a series of overlapping social systems (Reference PolakPolak, 1971a , Reference Polak1972): sets of interactive human relationships that vary in size, formality, function and permanence (Box 3). Like individuals, social systems are both sensitive to external stress and liable to internal conflict. They can cope adaptively or maladaptively. An individual often relates to several social systems at any one time. Some are relatively intimate and egocentric. These are embedded in less-intimate, community relationships with a general social group cohesiveness that is referred to as ‘social capital’ (Reference Kawachi and BerkmanKawachi & Berkman, 2001). Although social support for the individual derives from belonging to a social network, networks do not guarantee the availability of support (Reference Dickinson, Green and HayesDickinson et al, 2002). The cohesiveness of an overall social group can sometimes work against a stigmatised individual (Reference McKenzie, Whitley and WeichMcKenzie et al, 2002), when for example members of a group share a strong negative attitude towards an individual's behaviour.

Box 3 Social systems

Sets of interactive relationships

Vary in size and formality

Sensitive to external stresses

Liable to internal conflicts

Individuals can relate to several systems

Understanding a mental health crisis in terms of social system breakdown (Reference PolakPolak, 1972) leads to ‘social systems intervention’ as a technique for achieving crisis resolution, and this can provide an alternative to admission to hospital. As shown in vignette 1, a particular stressful event such as bereavement might equally cause a crisis for a social system as it does for an individual within the system.Footnote 1

Vignette 1

A young man becomes profoundly depressed after the death of his father. When his mother, despite his frame of mind, expects him to act as host for social gatherings, major conflict emerges, with further deterioration in his mental state.

The crisis of loss and grief that he is experiencing is mirrored by a separation crisis for the family – his widowed mother and his sister. There is now a risk of regression of the social system, with labelling, scapegoating and extrusion: admission to hospital may result. Furthermore, the healthy process of grieving in individual family members may become inhibited.

A simple social systems intervention – meeting with all concerned and facilitating discussion – enables the reconstitution of a supportive social framework, within which the son's incapacitating depression is successfully treated without admission to hospital, and important roles and functions within the family (such as breadwinner and host) are successfully reorganised and reallocated.

Crisis theory (Reference RosenRosen, 1997), which was partly derived from general system theory (Reference Von BertalanffyVon Bertalanffy, 1968), proposes that a crisis represents both a risk of regression and failure and an opportunity for constructive growth and adaptation. At the time of crisis there can be an increased accessibility to offered help, and small interventions can relatively quickly produce large changes in coping. Crisis theory thus indicates that detection and intervention are best sooner rather than later, and in situ rather than elsewhere.

‘Complexity science’ (Reference Plsek and GreenhalghPlsek & Greenhalgh, 2001), which echoes aspects of general system theory, also provides a framework for understanding how individuals behave in social systems. Social systems are examples of complex adaptive systems. In such systems, events occur in ways that are not totally predictable, but are nevertheless interconnected: one agent's action changes the context for other agents. This framework is applicable to the majority of clinical situations: ‘few if any human illnesses can be said to have a single “cause” or “cure”’ (Reference Wilson and HoltWilson & Holt, 2001).

Social factors and admission

Despite the common assumption that psychiatric admission to hospital can be regarded as synonymous with an episode of ‘real’ mental illness, it is evident that admission of a patient in acute mental distress can be as much a social as a medical necessity (Reference PolakPolak, 1967; Reference MorriceMorrice, 1968; Reference Polak and JonesPolak & Jones, 1973; Reference Tyrer, Tyrer and CaseyTyrer, 1993). Such an admission is usually necessary to deal with a crisis in coping after one or more significant life events – the resources for dealing with the situation otherwise seem exhausted. However, a common potential side-effect of the admission is to translate what should at least partly be understood as a social necessity into a medical problem requiring medical treatment: after all, the social context is now the hospital (Box 4).

Box 4 Side-effects of in-patient admission

Neglect of usual social circumstances

Emphasis on the medical model

Stigmatising exposure to an institutional social context

Disengagement with community mental health teams

Delayed discharge

Readmission

It has been argued that the social environment of the psychiatric ward has little or no relevance to the disturbances in social context in the real-life setting that bring the patient there (Reference PolakPolak, 1971b ). The process of admission seals the avoidance and denial of social systems problems, with medicalisation emphasised on admission by the mandatory physical examination, often with routine laboratory and radiological investigations. After a day or so, any awareness of the social reasons behind the admission can be lost, especially when those involved in the admission decision are off duty, or are not involved in ongoing in-patient care. Hence, there is a powerful and stigmatising tendency for the need for in-patient care to be subsequently re-framed in terms of the individual and not in terms of his or her social circumstances (Reference PolakPolak, 1970, Reference Polak1971b ). This phenomenon, first described 30 years ago, seems have been exaggerated by the intervening ascendance of biological psychiatry (Reference CohenCohen, 2000; Reference DoubleDouble, 2002). Additional contributory factors include a recent emphasis on developing resources outside the hospital, a consequent general neglect of the process of psychiatric in-patient care, and an increasingly custodial response to the perceived risk of violence (Reference Wall, Hotopf and WesseleyWall et al, 1999). In hospital, the patient's mental state, diagnosis, need for medication and risk management become the overriding concerns. Subsequently, when discharge from in-patient care seems feasible from the medical point of view, delays and difficulties can occur, as relevant but so far neglected social issues come back into focus.

It was previously estimated that the average acute psychiatric admission addressed only one-third (largely related to the individual) of the pertinent issues creating the need for hospitalisation. Two-thirds (largely related to social circumstances) remain to cause future difficulties on discharge (Reference PolakPolak, 1967; Reference MorriceMorrice, 1968). Discharge from traditional in-patient care may be deemed feasible because the individual is now more able to cope, or because circumstances outside hospital are now more favourable to coping. However, if the social circumstances that caused the admission in the first place have remained throughout the admission, they can be reactivated on discharge. While in hospital, the individual's coping resources may have become adequate, even though illness behaviour may have been reinforced by the ward environment. But on discharge, the natural environment within relevant social systems may prove relatively hostile, and unresolved conflicts and communication problems (Reference PolakPolak, 1971a ) may remain, once more testing the individual's coping ability.

Vignette 2

A woman is admitted to hospital after a serious overdose precipitated by her 30-year-old daughter's going on holiday. Her severe depressive illness apparently reflects her inability to negotiate a healthy process of emancipation for her daughter. The admission removes the mother from the conflict situation, and with the passage of time and treatment with antidepressants, her depression remits.

The cause of the illness has not been resolved by hospital admission. Although the mother is discharged with an improved mental state, if the failure in mother/daughter emancipation is not addressed, the risk exists of recurrent depression. Moreover, what might now may take weeks of discussion may have been achieved in a few days of appropriate intervention in the situation that led to the admission.

Labelling, scapegoating and extrusion (see vignette 1) are social processes that can lead to psychiatric admission (Reference PolakPolak, 1972). When a social system is affected by a significant life event it enters a period of disequilibrium. A vulnerable person within such a system may take the brunt of the disturbance and be labelled by the system as a patient. The patient can then become a scapegoat. The system may establish a new equilibrium, albeit maladaptively, by extrusion: admission of the patient to hospital.

Vignette 3

A teenage girl is admitted to the ward for the treatment of a severe depressive illness. Subsequent assessment reveals that her father has died suddenly and that the patient is expressing grief for the whole family. This is a response to the mother's lead in never expressing sadness at their loss. The grief of the patient is intolerable for her family. Admission to hospital removes the very painful reminder of loss for the family.

Chronic disturbed behaviour may be accommodated within a social system until an event upsets the equilibrium of the system. Then the behaviour may become intolerable, with the system labelling it as deviant: the person is now seen as a patient in need of professional help. The system extrudes the scapegoated individual into hospital, closing ranks behind as this happens. The process is confirmed by the fact that the assessing professionals have deemed in-patient care to be appropriate.

Vignette 4

A teenage girl takes an overdose, her distress highlighting her mother's chronically disturbed behaviour. The mother is a long-standing drug user, and because of her habit has been unable to attend to her daughter's needs. The extended family has previously coped by substituting the grandmother's care for the daughter. When the grandmother recently died, the girl went to live with her uncle, who rapidly found the situation intolerable. Following the girl's overdose the uncle seeks professional help for the mother (his sister): her intoxicated behaviour becomes labelled as illness, and in-patient treatment is arranged. The crisis resolution team then agrees to enable early discharge from the ward, meeting with the family and providing continuing home-based treatment. The uncle renegotiates his niece's care within the extended family.

It is important to note that, although the process of labelling, scapegoating and extrusion applies to some cases of admission to hospital, it is by no means a central feature in all cases. A crisis resolution team needs to keep a watchful eye out for the phenomenon and aim to work on reversing the process when it is clear from initial assessment that it is a factor. What is needed by way of intervention will vary with the circumstances.

Once a crisis resolution team is established, all subsequent requests for admission to in-patient care should be filtered through the team. This important gatekeeping role (Reference Protheroe and CarrollProtheroe & Carroll, 2001) should identify among patients who do require in-patient care the many who might benefit from early discharge with help from the crisis resolution team (see Part 2: Reference Bridgett and PolakBridgett & Polak, 2003, this issue). The relevant social factors noted at the time of admission will include some that can be addressed immediately and others that should await future action – at discharge or later. Hence the benefits of integrating the work of the crisis resolution team with that of the ward (Department of Health, 2002a ; Reference SmythSmyth, 2003).

Crisis assessment and practical problem-solving

The crisis resolution team is sometimes styled a ‘ward on wheels’, since it travels to the patient outside of the hospital. This is misleading if it means that the same type of care is applied outside hospital as on the ward. If this is all that is achieved, there is a good chance that the quality of care will improve, but problems in the patients’ social setting might continue to be ignored almost as much as they are in routine hospital treatment.

Expertise on the ward in understanding the individual in terms of mental and physical status needs to be expanded off the ward to achieve a similar expertise in assessing and dealing with relevant social difficulties (Reference Campbell and SzmuklerCampbell & Szmukler, 1993). Those that are easiest to understand and cope with are the practical matters of day-to-day life (Box 5). All of these are immediately (and conveniently) ‘solved’, almost without thought, by admission to hospital. The new member of a crisis resolution team quickly grasps the need to recognise the opportunities to act in a common-sense and practical way to obviate admission. Having the wherewithal to take someone home from the accident and emergency department via the supermarket to buy a bag of groceries and recharge an electricity key is clearly crucial. The duty doctor or the bed manager can only offer a bed.

Box 5 Practical social problems for a crisis resolution team

Shortage of money

Inadequate shelter

Risk of accident

Danger of exploitation

Neglect of self-care and diet

Thus, within a couple of weeks of becoming operational the new crisis resolution team becomes familiar with how routine ward procedures (Box 6) can be transferred to people's homes, and how often this is welcomed by both patients and carers. The solving of practical problems and even dealing with issues of communication and internal politics surrounding the introduction of a new service quickly seem manageable.

Box 6 Crisis resolution team tasks transferred from the ward

Medical assessment of physical and mental state

Prescription and dispensing of medication

Risk management

Provision of ongoing support and supervision

Communication and liaison

Social systems assessment: preliminaries

The difference between a traditional ward approach and that of a crisis resolution team using a social systems approach becomes evident when cases are presented between colleagues. On the ward, admissions are usually presented with an emphasis on mental state, differential diagnosis, safety and medication. The focus is on the patient concerned and the account he or she has given, and on information provided by the referrer – perhaps a duty doctor or duty community mental health team worker. The account will have been influenced by both what the patient thinks a professional wants to know and what the worker is used to dealing with. Such an account is clearly useful, but should be seen only as ‘the story so far’ (Box 7).

Box 7 Characteristics of ‘the story so far’

Dwells on the mental state

Considers the differential diagnosis

Refers to the need for medication

Includes risk management

Omits the social dimension

The ‘story so far’ can be profoundly enriched by asking for more information, not so much from the patient, but from significant others. Who else can say more about what is already known? How can they be contacted? How does their point of view raise further issues to discuss with the patient? With which of the patient's social systems can the referral crisis be most closely identified? (Box 8) (Reference PolakPolak, 1967; Reference FishFish, 1971; Reference Polak and KirbyPolak & Kirby, 1976; Reference Polak, Deever and KirbyPolak et al, 1977).

Box 8 Commonly involved social systems

Family

Friends

Neighbours

Colleagues

Carers

The origin of the related social systems crisis needs to be determined (Box 9). Is the ‘illness’ more a cause or an effect of the crisis? What aspects of which social systems can be identified as strengths to be harnessed in formulating a care plan?

Box 9 Common origins of crises

Bereavement and loss

Illness of the self or others

Financial and job problems

Accommodation difficulties

Legal worries

Others – key informants – therefore need to be involved in further assessment of the crisis. An initial hypothesis should then be formed concerning the nature of the crisis, to give a focus to the assessment. This can be especially useful when there seem to be many issues involved. The hypothesis should link with the initial goals of crisis resolution team involvement. Subsequent ‘drift’ in the work of the team can then be avoided.

The enquiries, often by telephone, can be particularly useful when they are made sooner rather than later – immediately after the initial referral has been taken and before any lengthy interview with the patient concerned.

Experience shows just three telephone calls can establish which social systems are involved, which social systems crisis it is practical to tackle first, and who to invite to the first social system meeting.

It must be only in exceptional circumstances, and then only after documented discussion and agreement with others, that such telephone calls are made without the informed consent of the person being referred. To the uninitiated, this preliminary exploration of the social context can seem radical and fraught with risk. It may be feared that, like opening Pandora's box, such enquiry might release further complicating, potentially dangerous and difficult-to-deal-with problems. However, it is important to consider how focusing on the wrong issue and missing the right one can be even more regrettable. Moreover, it can be reassuring to know that if an enquiry is made in a suitably sensitive manner, it is unlikely to provoke an avalanche of difficult-to-deal-with problems.

Thus, issues of confidentiality and invasion of privacy need to be balanced against the real need to understand how to help the individual concerned as appropriately as possible. It is important also to recognise the normal willingness of most people to be helpful and caring towards others, especially those within a particular social system (e.g. the family, workplace or informal social circle). In making the preliminary telephone calls, a great deal can be achieved very quickly with simple and general enquiries, coupled with careful listening to what is both said and not said in reply. It should be feasible to find out whether or not the person is willing to help further or knows of others it might be relevant to contact (Box 10). These initial telephone calls might include going back to the original referrer, especially with patients already known to the service: indeed, for long-term patients the relevant social system might involve other patients and other mental health workers (Reference Dickinson, Green and HayesDickinson et al, 2002).

Box 10 Questions to ask key informants

What do you think has happened?

Do you know why?

How were things before?

Are you able to help?

Who else might help?

Thus, in contrast to the usual practice of interviewing the patients before any other action is taken, the crisis and social systems approach is facilitated by time spent finding out more about a referral before the first interview with the patient. This might reveal that it would be very useful to have present at the first assessment others particularly familiar with the issues involved.

The first interview is best done in the place where the patient is at the time of the referral, rather than arranging for him or her to go elsewhere. Alternatively, if not already at home, it might be acceptable to take one patient home before a full interview. The social context of the initial contact can be revealing, and knowledge about it might contribute to an assessment. During assessment, the behaviour of patients and of significant others is often influenced by the social context of the assessment. Assessment in the real-life situation should therefore always occur as soon as possible, before important elements of the crisis have a chance to evaporate (Reference Sutherby, Szmukler, Phelan, Strathdee and ThornicroftSutherby & Szmukler, 1995). Once this process has started, however, there is no advantage in hurrying: a slow assessment can become the first and most significant intervention. Time is a commodity a crisis resolution team can use to advantage, especially during assessment. Others dealing with urgent referrals are often under pressure to make decisions quickly and move on. By working more slowly, the crisis resolution team can sometimes identify and clarify the essential issues to be tackled, ensuring that interventions are appropriate.

Despite the early contact with significant others, at initial assessment the emphasis needs to be on the point of view of the patient, rather than that of anyone else (Reference PolakPolak, 1970; Reference Relton and ThomasRelton & Thomas, 2002). Reference to Maslow's hierarchy of needs (Reference MaslowMaslow, 1998) may be useful: some needs take precedence over others. It is important to work with the patient's own priorities: setting up another agenda can prove futile. The first interview should both allow the patient to give a subjective account as freely as possible and introduce the need for connections to be made with his or her social systems. Which of these is relevant may become evident in what is presented spontaneously, and if so they should be noted for future elaboration. If nothing is revealed, it might be necessary to apply a checklist of direct questions to explore thoroughly the possible ramifications of the presenting problem. These questions are easily generated from knowledge of which social systems are most likely to be relevant and what are the most common upheavals to be expected in each of these systems (Boxes 8 & 9).

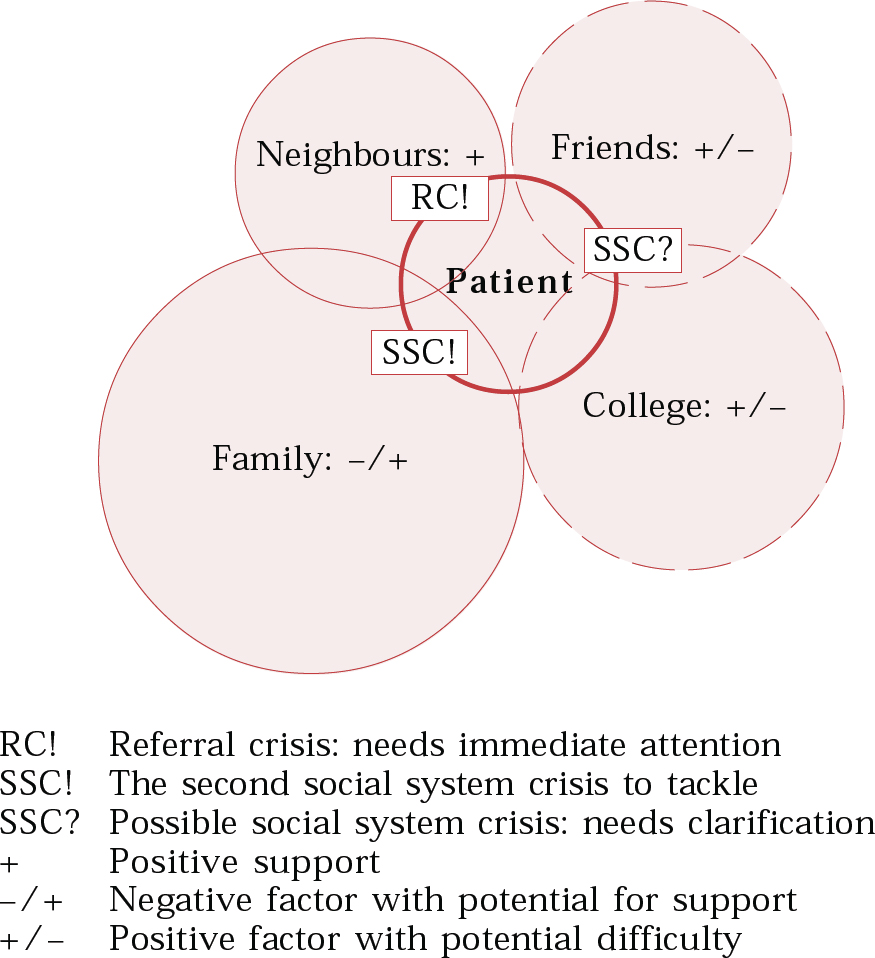

Once an initial assessment of the issues involved has been achieved, it is useful to record in diagrammatic form the social relationships involved: the overlapping social systems that seem relevant, where the sources of difficulty are, where the strengths remain, and what interventions are indicated. This mapping exercise (e.g. Fig. 1) may be particularly useful for in-service training.

Fig. 1 A mapping exercise for vignette 5. The circles indicate the patient and her social systems, and their sizes indicate estimated relative psychological significance. Solid circles indicate current work, broken work to be undertaken later.

Vignette 5

A 20-year-old female student who lives alone is brought to the accident and emergency department by neighbours after an attempt at suicide. Mental state examination reveals depressed mood, command auditory hallucinations, thought disorder and passivity delusions. A provisional diagnosis of acute schizoaffective disorder is made by the duty doctor and, without the crisis resolution team, admission to the ward is indicated.

When home treatment by the team is agreed as a safe alternative to admission, the patient's family – who live abroad – come to London and meet with the team. A complex story emerges. Before attending college the young woman had felt that her abilities and talents – which are considerable – were not valued by her parents, who seem motivated principally by commercial interests and success in business. She had previously attended a boarding school, where she enjoyed good support from her peers. During her first year at college she has been slow to make new friends, but has been very successful with her course: it emerges this success is a major stress for her. Early work with the family focuses on enabling them to recognise her predicament and provide appropriate support.

The dramatic referral crisis, described to the crisis resolution team by the duty doctor in ‘story so far’ format, conceals a background social systems crisis in the young woman's maturation and in her relationships within the family, especially with her parents: the family system seems most involved. Denial and communication difficulties were soon clear – but the need also to involve her college and her new friends is also evident (Fig. 1).

This overview of social systems intervention is continued in Part 2 (Reference Bridgett and PolakBridgett & Polak, 2003, this issue), which covers the first social system meeting, interventions, early discharge from in-patient care, the auditing of outcome, and questions to be explored by both informal in-service evaluation and formal research.

Multiple choice questions

-

1 Understanding social context:

-

a is irrelevant for Mental Health Act assessments

-

b contributes to risk assessment

-

c helps choice of neuroleptic medication

-

d is necessary to reduce inappropriate in-patient care.

-

-

2 The following are characteristics of most crisis intervention:

-

a mental health services are involved

-

b medical assessment is carried out

-

c the intervention deals with emergencies

-

d the intervention facilitates ‘healthy coping’.

-

-

3 Social systems:

-

a can be expected to be supportive

-

b vary in size and permanence

-

c overlap and interact

-

d are part of informal rather than formal care.

-

-

4 Psychiatric in-patient care:

-

a is appropriate only for medical problems

-

b is increasingly associated with compulsion

-

c can be shortened by crisis resolution team involvement

-

d can be combined with social systems intervention.

-

-

5 Labelling, scapegoating and extrusion:

-

a are central features of all psychiatric admissions

-

b can be emphasised by service intervention

-

c should be explored at social systems meetings

-

d may follow a crisis in a social system.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | F | a | F | a | F | a | F | a | F |

| b | T | b | F | b | T | b | T | b | T |

| c | F | c | F | c | T | c | T | c | T |

| d | T | d | T | d | F | d | T | d | T |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.