1. Introduction

Subsidies regulation is still among the most controversial aspects of WTO law, at least from an economics perspective. Distinguishing between welfare-reducing and welfare-enhancing subsidies is not an easy task, whereas analyses neglect the potential benefits of domestic subsidies for foreign producers, for instance in the case of export subsidies. In addition, the increased complexity and intermingling of subsidies regulations with tax instruments that are put in place to affect corporate decisions may lead to incoherent or, worse, arbitrary rulings by the relevant adjudicator.

With respect to a duopolistic market, such as large civil aircraft, efforts to discipline subsidies may display sector-specific peculiarities. At the outset, this industry has important economies of scale. These economies may be so significant that no more than two firms can be profitable. Thus, if natural duopoly is optimal, then prices may rise significantly above marginal costs, even in the absence of collusion. If structural factors lead to a reduction of output below the competitive level, subsidies may be an ideal policy response to increase industry output, thereby increasing welfare. In addition, aviation is a highly innovative industry. However, it is not always clear that, in this industry, innovators can at all times have reasonable returns to innovation so that appropriate incentives for investment in R&D are provided. If this is a challenge, then subsidies may be an adequate policy response.Footnote 1

In US–Tax Incentives, at stake were potential import substitution subsidies granted to Boeing by the State of Washington to incentivize the former to site its commercial manufacturing program and the final and wing assembly relating to the Boeing 777X program in the State of Washington. Interestingly, most of the case related to future manufacturing operations that had not started at the moment the Panel deliberated, as the first variant of the Boeing 777X is not expected to enter into service before the year 2020.

It seems that the siting of the manufacturing of the Boeing 777X in Washington State was anything but a coincidence. In fact, several States ostensibly offered incentives to Boeing so that the latter would establish its aircraft assembly operations in their jurisdictions. In the end, Boeing decided to locate the 777X manufacturing project in the State of Washington, which offered over $8 billion in tax breaks. For some, this is probably the largest incentives package ever offered to date.Footnote 2

While relatively short, the Appellate Body (AB) Report is quite important. It focuses on an underdeveloped concept under the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM), that is, import substitution subsidies as a matter of law (so-called ‘de jure contingency’) and as a matter of fact (so-called ‘de facto contingency’). Crucially, the Appellate Body clarified in this dispute the scope and limits of these subsidies, which are disciplined under Article 3:1(b) SCM. Viewed from this angle, US–Tax Incentives is a landmark case with respect to import substitution contingency.

In this regard, at the heart of the dispute was whether a WTO Member (in this case, the US) can circumvent its obligations under the SCM by adopting measures that focus on the siting, or location, of manufacturing activities rather than the use of domestic over imported goods. In other words, can the wording of a given measure save it from SCM scrutiny despite its competition-distorting effects? Clearly, such effects may be inextricably linked to the nature of the industry (bulky inputs; economies of scale; or significantly high transport costs that create incentives for locating production next to assembly sites); but in this case, how far should a dispute resolution body go with its analysis of the relevant market and the effects of certain measures on the marketplace? In addition, a related question raised is what would be the necessary and sufficient effects of a given measure on input sourcing decisions to trigger the application of Article 3.1(b) SCM. Finally, the dispute is of significance because it sheds light on the supply chain of the aviation sector. From a political economy point of view, the dispute is interesting because it is the most recent block of the chain relating to the transatlantic aviation dispute, with the US registering a quite clear victory.

We will argue in this article that the AB's test to determine that a measure in its application makes a subsidy contingent on the use of domestic over imported goods is too formalistic and narrow. More crucially, it blurs the distinction between contingency in law and contingency in fact. However, even if the approach proposed here is dismissed, a more careful, thorough and market-oriented look at the measures adopted by Washington State, which would also be in line with the peculiarities of the aviation sector, should still have led the AB to find that these measures promote and indeed require the use of domestic inputs, thereby meeting the threshold that Article 3.1(b) SCM requires. Section 2 discusses the measures at issue, whereas Sections 3 and 4 offer a succinct analysis of the Panel's and AB findings, respectively. In Section 5, we critically review important conceptual issues relating to import substitution subsidies. Section 6 applies the de facto contingency analysis recommended by the AB to the US–Tax Incentives dispute and Section 7 concludes.

2. The measures at issue

The EU challenged certain aerospace tax incentives promulgated by the State of Washington which offered (a) a business and occupation (B&O) tax rate of 0.2904% regarding the manufacture and sale of commercial airplanes and (b) various tax credits or exemptions relating to product development activities, property taxes, and sales and use taxes (see Table 1 for a detailed description).

Table 1. Seven separate tax measures

This dispute should be seen within the context of a long-standing rivalry between Boeing and Airbus, with several instances of cooperation but also fierce competition.Footnote 3 The Washington bill extends certain tax measures first established in 2003, which were challenged by the EU in a previous WTO dispute.Footnote 4 The first three aerospace tax measures relate to the B&O tax, which is the main business tax in the State of Washington. The next two measures are exemptions from Washington's retail sales and use taxes. The final two tax measures relate to property taxes imposed on certain leaseholds in Washington, and foresee a leasehold excise tax exemption and a leaseholder property tax exemption.

According to an amendment to Washington law that was enacted in November 2013, these tax incentives would be available to the American airplane manufacturer, Boeing (among other corporations interested to make use of the incentives), if the company adhered to two ‘siting’ provisions included in the relevant legislation, which focused on the siting and assembly activities relating to the Boeing 777X.Footnote 5

Pursuant to the First Siting Provision, for the tax incentives to take effect, a significant commercial airplane manufacturing program would have to be sited in Washington. The First Siting Provision defines ‘siting’ to entail a final decision, made on or after 1 November 2013, by a manufacturer to locate a significant commercial airplane manufacturing program in Washington State. In turn, ‘significant commercial airplane manufacturing program’ is defined as:

[A]n airplane program in which the following products, including final assembly, will commence manufacture at a new or existing location within Washington state on or after [June 30, 2017]:

(i) The new model, or any version or variant of an existing model, of a commercial airplane; and

(ii) Fuselages and wings of a new model, or any version or variant of an existing model, of a commercial airplane.

The First Siting Provision additionally defines ‘new model, or any version or variant of an existing model, of a commercial airplane’ to mean ‘a commercial airplane manufactured with a carbon fiber composite fuselage or carbon fiber composite wings or both’.

The Second Siting Provision foresees the non-availability of the B&O tax rate only if the Washington Department of Revenue (DoR) finds that any final assembly or wing assembly of a commercial airplane (that is the basis of a siting of a significant commercial airplane manufacturing program under the First Siting Provision) has been sited outside of Washington.

Thus, to meet the First Siting Provision and the requirement for a significant manufacturing program, Boeing had to:

(a) establish the 777X production program in Washington State where the wings and fuselages are to be integrated; and

(b) (some of) 777X wings and fuselages have to be manufactured in Washington.

Both the US and the EU agreed that the requirements of the First Siting Provision had been fulfilled and thus the benefits accrued to Boeing are in effect. Indeed, the Washington State DoR determined on 10 July 2014 that Boeing made a final siting decision, which resulted in the extension of the expiration date of the relevant aerospace tax measures until 1 July 2040. Crucially, this determination is a one-time decision pursuant to ESSB 5952, meaning that the initial establishment of the program is necessary but the extended expiration date is not contingent on the continuation of such activity.Footnote 6

The Second Siting Provision stipulates that the continued (or non-) availability of the 0.2904% B&O aerospace tax rate would cease to exist if the final assembly or the wing assembly of the Boeing 777X were to take place outside the State of Washington. This again would entail a negative determination made by Washington State's DoR, which, unlike the one-time decision under the First Siting Provision, was at the discretion of the DoR. This negative determination, possible at any point, would lead to the termination of the subsidy previously granted under the First Siting Provision. Crucially, for our purposes, the EU challenged each of the two provisions separately but also requested that the WTO adjudicating bodies examine the combined effect of the two provisions applied in the case of Boeing.

3. The Panel findings

The Panel found that all seven aerospace tax measures at issue entail a financial contribution by the government of the State of Washington and a benefit is thereby conferred. Therefore, each of the seven tax measures come under the definition of a subsidy pursuant to Article 1 SCM.

With respect to the EU's complaint, the allegation of contingency, that is, the tying of the subsidy granted by the State of Washington to the actual use of domestic goods to the detriment of foreign or imported ones took central stage in this dispute already during the Panel proceedings. The EU's primary claim with regard to ‘contingency’ was that the First Siting Provision and the Second Siting Provision, considered individually or together, constitute subsidies that are contingent on the use of domestic over imported products (in this case, wings and fuselages) both in their very terms (de jure) and in their application (de facto).

3.1 De jure contingency

With respect to Article 3.1(b), the Panel first examined whether the challenged aerospace tax incentives amounting to a subsidy were de jure contingent on the use of domestic goods. In doing so, the Panel focused on the text of the relevant legislation to identify whether such contingency or conditionality is expressly enshrined in the Washington State legislation or could rather be unequivocally derived, by necessary implication, from the wording of the legislation at stake.Footnote 7 The Panel noted that the First Siting Provision was silent regarding the use of imported or domestic goods nor did it make the receipt of subsidies conditional on the non-use of imported goods. The Panel went on to deny also any de jure contingency by necessary implication. In this regard, the Panel found nothing in the language of the measure or other evidence necessarily excluding the possibility for Boeing to use wings or fuselages from outside Washington State.Footnote 8 Eventually, the Panel found that the EU failed to demonstrate that the measures at issue constituted subsidies de jure contingent on the use of domestic over imported goods with respect to the First Siting Provision.

Furthermore, the Panel considered that the EU failed to demonstrate that the B&O tax rate is de jure contingent on the use of domestic goods with respect to the Second Siting Provision. In this regard, the Panel underscored the absence of (1) any express indication that the benefit relating to the preferential tax rate would be lost if Boeing decided to import wings for its 777X production or (2) any other requirement that the goods for Boeing's production activities be sourced only from within Washington State. While the Second Siting Provision requires that manufacturing of commercial planes (including by final assembly) not be sited outside Washington State, it does not go as far in its wording, or by necessary implication, as to require the use of inputs produced in Washington State.Footnote 9

Finally, the Panel discussed the EU's claim that the two Siting Provisions jointly act to maximize trade distortions in favor of domestic inputs. In doing so, though, it took issue with the EU's claim, as it found no pertinent elements suggesting that the analysis of the two provisions if taken together should be different from that if taken separately. Thus, the Panel found that the EU unsuccessfully argued that the tax measures at issue are subsidies de jure contingent on the use of domestic goods if one considers jointly the two Siting Provisions.

3.2 De facto contingency

Unlike the claims relating to contingency based on the mere wording of the measures at issue, the result of the Panel's analysis regarding the EU's secondary and alternative claim of de facto contingency was favourable to the EU's position. The Panel agreed with the EU that, regarding the two Siting Provisions considered jointly, the B&O aerospace tax rate for the manufacturing or sale of commercial airplanes under the 777X program is a subsidy de facto contingent on the use of domestic goods. For de facto contingency to exist, the Panel noted that more factual evidence was necessary: the total configuration of the facts that constitute and surround the granting of the subsidy, including the design, structure and modalities of operation of the measure granting the subsidy, alone or taken together, would be decisive. According to the Panel, a holistic examination of all available evidence would be warranted, focusing in particular on the elements identified above.Footnote 10 As the First Siting Provision was satisfied by Boeing's 777X siting decision, the Panel was of the view that the operation of the two provisions could no longer be dissociated and thus an analysis of the joint operation of the two provisions was apposite.Footnote 11

In its analysis, the Panel appeared to dismiss the EU's claim that the use of domestic over imported goods was a condition for a positive determination by the DoR in respect of the First Siting Provision but found compelling the EU's argument that Boeing would lose access to the preferential B&O tax rate if it made use of foreign-made wings (or, for that matter, assembled wings abroad) for the 777X under the Second Siting Provision. Thus, the Panel decided to focus on the issue of input (or component) sourcing decisions with a view to identifying whether the granting of the subsidy was conditional on whether certain components are sourced from a foreign or domestic origin.

In examining the effects of the Second Siting Provision, which, as noted earlier, had never been triggered by the DoR, the Panel was wary of the negative phrasing of that measure, acting as a passive deterrent to safeguard the status quo that the First Siting Provision aimed at establishing. At the heart of the Panel's analysis was a counterfactual question as to whether the DoR would consider the use of imported wings by Boeing as amounting to siting wing assembly outside Washington State and thus a ground to terminate the subsidy.

In response of the Panel's hypothetical questions, the US contended that the importation of completed wings produced outside the United States would likely trigger the application of the Second Siting Provision.Footnote 12 The Panel, however, noted that whereas the use of imported wings would lead to the loss of the preferential B&O tax rate, the use of wings produced in Washington State by another producer would not trigger the Second Siting Provision, thereby tilting Boeing's choices towards using domestic goods to the detriment of goods (in this case, wings) produced outside the US. Thus, the Panel found that the B&O tax rate is contingent de facto on the production of the 777X and its wings in Washington State but also on the non-use of wings for the 777X other than those made in Washington State.Footnote 13

Thus, despite rejecting the EU's claims that the measures at issue required the use of domestic over imported goods de jure, the Panel agreed with the EU that the two key provisions of the measure at issue, when considered together, de facto required the use of domestic inputs within the meaning of Article 3.1(b) SCM. By necessity, then, the US also violated its obligations not to grant or to maintain any local content-related subsidies under Article 3.2 SCM.

4. The AB findings

As one would expect, the EU challenged the Panel's findings relating to de jure contingency and the legal standard used in this respect by the Panel, including certain procedural issues, whereas the US was unhappy with the final verdict of the Panel Report and thus called for a reversal of the Panel's findings relating to de facto contingency; more specifically, that the Second Siting Provision requires the use of domestic over imported goods. In addition, both parties raised procedural questions, including an alleged failure by the Panel to make an objective assessment of the matter before it, thereby contravening Article 11 DSU. Due to the importance of the substantive issues and findings discussed in the AB report, we will refrain from discussing the procedural, and less controversial, claims raised in the appeal.

4.1 Consolidating the WTO case law under Article 3.1(b) SCM

The AB started by taking stock of its case law regarding Article 3.1(b) and the prohibition of local content subsidies laid out therein. It reiterated that there are various legal avenues to challenge subsidization practices: one would indeed be to invoke the existence of an export subsidy or an import substitution subsidy which are both per se prohibited but another would entail invoking adverse effects under Article 5 SCM and challenging a specific subsidy under Part III of the SCM. Later, the AB also noted that the SCM does not aim to discipline all subsidies: various domestic production subsidies would escape the scope of the SCM agreement although they can potentially have equally trade-distortive effects to prohibited subsidies in that they artificially increase the supply (and thus the use downstream) of the subsidized domestic product in the relevant market.Footnote 14 Having said this, the AB underscored that a domestic production subsidy, which is in principle exempted from the scope of the GATT under Article III:8 GATT, could still be regarded as violating Article 3:1(b) SCM if it was conditional on the use of domestic goods by domestic producers.Footnote 15

Contrary to previous cases such as Canada–Autos, whereby the AB focused on the legal standard of the provision alone, in US–Tax Incentives the AB took a step-by-step approach in examining each one of the significant concepts laid down in Article 3.1(b) other than contingency, including ‘use’, ‘goods’, or ‘domestic’ as compared to ‘imported’. The AB went on to discuss contingency emphasizing that it expects panels to conduct a holistic assessment of all relevant evidence and elements on the record, examining in the case of a de facto contingency claim, the total configuration of the facts constituting and surrounding the granting of the subsidy with a view to establishing that the use of domestic goods was required as a condition for eligibility under the subsidy scheme at stake.Footnote 16 Such a comprehensive assessment is all the more necessary when the complainant, as one would expect, claims that the measure at issue could constitute a de jure and, alternatively, a de facto import substitution subsidy.

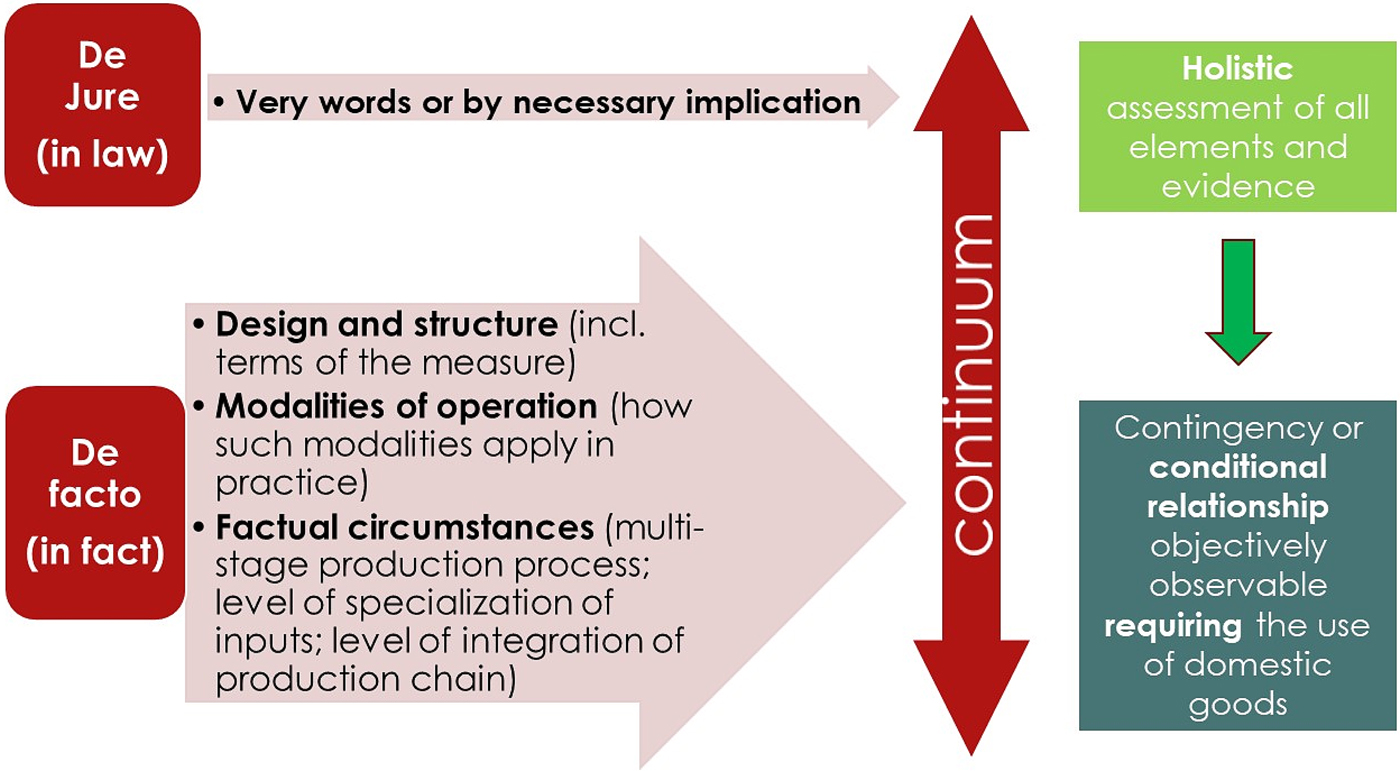

Crucially, just like the Panel earlier, the AB restated a number of factors that can be relevant in the case of examining de facto contingency in order to establish an objectively observable conditional relationship between the subsidy and the use of domestic over imported goods.Footnote 17 These include (a) the design and structure of the measure, (b) the modalities of operation, and (c) the relevant factual circumstances relating to the granting of the subsidy. Under (a) the analysis would focus on the terms of the measure. Under (b), the analysis would turn to the relevant modalities set out in the measure and how they may be applied or operate in practice. Finally, under (c), one would expect an analysis of those circumstances that inform one's understanding of all previous factors and their operation. The AB noted that relevant factual circumstances in the case of a de facto contingency analysis would include the existence of a multi-stage production process, the level of specialization of the subsidized inputs or the level of integration of the production chain in the relevant industry (see Figure 1).Footnote 18

Figure 1. The standard of review under Article 3.1(b) SCM

An interesting observation at this point is that the AB seems to be very well aware of the importance of a holistic but also case-specific analysis of the relevant market and the circumstances surrounding the subsidy as well as the characteristics of the market in which the subsidy scheme exists. While one would expect this to figure quite prominently in the subsequent analysis offered by the AB, unfortunately the highest instance of the WTO judiciary avoided delving into such, admittedly quite demanding and intensely factual, analysis.

Rather, later on, when discussing whether the Second Siting Provision entailed any de jure contingency, the AB – in a seemingly misplaced paragraph – returned to the issue to acknowledge that when subsidies are granted for the production of both the input and final good, subsidy-eligible undertakings would be inclined to both produce and use the subsidized inputs in the production of the equally subsidized final good. The AB even shared the EU's concerns that such a constellation would clearly affect the input-sourcing decisions of subsidized producers, as due to production costs and efficiency, they would likely use some of the domestically produced inputs in their downstream production activities. Such configuration of the supply/production chain is particularly likely in the production and use of specialized inputs and final goods or in the case of vertical integration between the upstream and downstream stages of production.

Finally, while the AB attempted to defend a certain degree of continuity between the AB findings in Canada–Autos and its ruling in US–Tax Incentives in that it defended the single legal standard approach for both types of per se prohibited subsidies (export subsidies and local content subsidies), it also noted that the test of contingency under export subsidies is broader and more lenient than in the case of import substitution. This is because the former would still be satisfied if the measure at issue was ‘geared to induce’ the promotion of future export performance, while the latter would seem to be more static, formalistic, and narrower, as the judicial review would need to focus on merely examining whether the measure requires the use of domestic over imported goods.Footnote 19 This point appears to be the key rationale of the AB's ensuing findings against the existence of de facto (or de jure, for that matter) contingency.

4.2 Addressing the points raised in the appeal by the EU relating to de jure contingency

In its appeal, the EU requested the AB to find that the Panel erroneously interpreted the per se prohibition of import substitution subsidy to only cover cases whereby the measure at issue requires the use of domestic goods to the complete exclusion of imported goods. Whereas the AB agreed with the EU that no such high legal standard is necessary for a violation of Article 3.1(b) to occur and thus the complainant is not required to demonstrate any particular quantity or level of displacement of imported goods by domestic goods, it rejected the EU's claim as misplaced because no such standard was endorsed in the Panel report neither in its de jure contingency analysis of the two Provisions nor in its de facto analysis of the First Siting Provision. Rather, in the AB's view, the Panel took issue with the EU's observation that the terms of the First and Second Siting Provisions necessarily required that Boeing use wings and fuselages produced in Washington State.

The AB continued by addressing the EU's claim that the Panel erred in its de jure contingency analysis of the First Siting Provision. In the EU's view, the design and structure of this measure would by necessary implication at least result in Boeing using some domestically produced wings and fuselages in 777X's final assembly. In its assessment, the AB recalled the strict and narrow reading the Panel should apply in examining whether de jure contingency exists. For such contingency to exist, the complainant would need to adduce evidence showing that the measure, by its terms or by necessary implication therefrom, entails a condition requiring the use of domestic over imported goods. The AB underscored that a mere likelihood of the use of domestic over imported goods is not sufficient to meet the high standard that the AB is looking for under Article 3.1(b). While strict, setting the bar this high can be justified by the quite severe implications of any subsidy coming within the scope of Article 3 SCM: these subsidies are prohibited per se and their immediate withdrawal is warranted as per the SCM agreement.

However, and quite crucially, the AB also noted that the First Siting Provision indirectly leads to the use of domestically manufactured wings and fuselages in the 777X's final assembly by requiring that they be manufactured domestically.Footnote 20 Arguably, this statement – and provided that the peculiar characteristics of the aviation market were taken into account – should have led the AB to reflect on the margin of maneuver that WTO Members should be allowed to have in requiring the location of certain manufacturing activities in given geographical areas, notably if such a requirement results in a circumvention of their obligations to avoid local content subsidies. At the same time, the AB reasoned that the conditionality required under Article 3.1(b) and notably its de jure form should require more explicit terms than merely obliging, even tacitly, the subsidy recipient to start manufacture of both airplanes and fuselages and wings as part of the same production program in Washington State. In the AB's view, even in this case, the use of domestic over imported inputs would be too remote to satisfy the standard of conditionality needed under Article 3.1(b) SCM, thereby agreeing with the US that the measures at issue entailed conditions on the siting of production activities without imposing the use of any goods, be it domestic or imported.Footnote 21

Finally, with regard to the Panel's de jure analysis of the Second Siting Provision, the AB rejected the EU's claim by finding that the Panel did not err or unduly restrict the scope of the available evidence. However, the AB did note that the method of the Panel compartmentalized the de jure and de facto contingency analyses and thus a more holistic assessment would be preferable, in line with its previous summary of the adequate review under Article 3.1(b) SCM.

4.3 Addressing the US appeal against the Panel's finding regarding de facto contingency

In its appeal, the US requested the AB to reverse the Panel's finding that the B&O aerospace tax rate is de facto contingent on the use of domestic over imported goods. According to the US, the Panel failed to take into account that the Second Siting Provision rather referred to the domestic siting of production activities and unduly used hypothetical scenarios that would trigger the application of Article 3:1(b) SCM. The EU, however, argued that the subsidy at stake prevents Boeing from using imported wings now and in the future.

The AB started by restating the constituent elements of contingency in application (de facto) under Article 3.1(b) and the importance of finding a condition requiring the use of domestic goods at least on a de facto basis. It also pointed to the Panel's focus on wing assembly and whether the Second Siting Provision required the use of domestic over imported wings in this regard. More specifically, the AB identified as important for this inquiry the Panel's focus on whether the DoR would consider in the future (recall that the Second Siting Provision was never enforced before) that Boeing relocated 777X wing assembly outside Washington State (and thus would terminate the subsidy that the B&O tax rate entails) in case Boeing used imported 777X wings. Indeed, the Panel seemed to believe that analysis under de facto contingency boils down to the question of whether the origin of the wings could trigger the Second Siting Provision.Footnote 22

The AB criticized the Panel because, in its view, it focused on the possibility for the condition for eligibility under the B&O subsidy scheme to result in the use of more domestic and fewer imported goods rather than identifying, through an analysis of the terms, design, structure and modalities of the subsidy, a condition requiring the use of domestic goods. While the AB recognized the very possibility for the US legislator to aim through this measure to prevent the production of inputs outside Washington State, which would then be shipped to Washington State for the assembly, it still noted that the location of production appears to be the decisive element that would trigger the loss of the subsidy. Instead, in the AB's view, the Panel overly extended the scope of Article 3:1(b) to also cover measures that have a consequential import substitution effect or a detrimental impact on importation by fostering – but, crucially, not requiring – the use of subsidized domestic inputs.

Finally, the AB agreed with the Panel on the relevance of counterfactuals when the operation of a measure has not yet been triggered but took issue with the way the Panel used the hypothetical scenarios and subsequent selected replies by the US to the Panel on this occasion. Interestingly, and quite crucially for our argument regarding the AB's approach, the AB suggested that the Panel should have given more attention to the circumstances of the measure, including the existence of a multi-stage production process, or the level of integration of the manufacturing and supply chain. While we agree, we cannot help but notice that the AB did not undertake the same market analysis that it advocated for the Panel. In our view, if the WTO adjudicating bodies agree that this is necessary, then they should be looking into the functioning of such markets and the effects therein more thoroughly. However, the AB decided to refrain from such an, admittedly demanding, exercise.

Based on the above considerations, the AB reversed the Panel's finding that the Second Siting Provision entails a de facto contingency upon the use of domestic over imported products pursuant to Article 3:1(b) SCM.

5. Discussion of some critical issues in US–Tax Incentives

5.1 The concept of import substitution subsidies

Import substitution subsidies of the type described in Article 3:1(b) SCM are deemed prohibited subsidies, unlike all other domestic subsidies, which are actionable under the conditions laid down in Part III SCM. Thus, unlike in the case of actionable subsidies, for import substitution subsidies the complainant does not need to prove adverse effects or specificity. The former are presumed and the same goes for the latter. Such subsidies are considered so trade-distortive – and in this case, clearly discriminatory – that their withdrawal shall be immediate as per Article 4.7 SCM.Footnote 23 Otherwise, the products of the subsidizing WTO Member may be subject to countervailing duties up to the level of injury that other WTO Members incur. Thus, as one can infer, prohibited subsidies enshrined in Article 3.1 SCM are not only subject to stricter scrutiny, requirements, and remedies than other WTO obligations but also timelines for dispute settlement.Footnote 24

Import substitution subsidies aim at promoting the use of domestic products to the detriment of foreign inputs. As they are not contingent on exports, they are a domestic (rather than a trade-related) tool that governments may routinely use to stimulate domestic production and increase the welfare of local input suppliers (for instance, through increased production, sales or employment). This, nevertheless, has a negative impact on competing suppliers in other countries, thereby harming those countries’ terms of trade. Negative effects can also be observed at the domestic level if there are industries that compete with the subsidized inputs, provided of course that there is competition in the production of such inputs.

Thus, such a prohibition of subsidies to domestic purchasers makes full economic sense. However, as Sykes convincingly argued, a prohibition on subsidizing domestic sellers, that is, domestic producers, would make equal sense if the purpose of international trade agreements is indeed to avoid market distortions through subsidization. This is because the effect of both subsidies is the same, that is, encouraging the production of more domestic products at lower prices and thereby leading to the purchase of domestic rather than imported goods by buyers.Footnote 25 Nevertheless, WTO law generally tolerates domestic producer subsidies.Footnote 26

This would mean that a government, being well aware of the prohibition of import substitution subsidies under WTO law, could structure its subsidy program in a manner that entails payments to producers rather than payments to purchasers.Footnote 27 At the same time, one could envisage federal (or state-level) incentives, be it tax-related or not, that cover the entire supply and demand chain, for instance, in oligopolistic sectors. Subsidization in that case would be pervasive and targeted, making the case for intervention at the global level through disciplining such behavior, even more compelling.

5.2 Distinction between investment promotion subsidies and import substitution subsidies

The discussion at the end of the previous section implies that as long as subsidies to producers are made contingent on the location of economic activity but not on the use of domestic inputs over foreign inputs, those subsidies do not necessarily run afoul of the SCM Agreement. The WTO rules contain no targeted disciplines for investment promotion incentives. Of course, the possibility to treat such incentives as actionable subsidies under Part III of the SCM remains intact.

This is an important choice of the WTO membership given that these potentially trade-distorting policies are used widely and on a very large scale: the best estimates available indicate that national, province/state, and local governments in the US and the EU expend tens of billions of US dollars per year attracting investment to their jurisdictions.Footnote 28 Given the widespread use of investment promotion subsidies throughout the developed and developing world, the worldwide total could easily top US$100 billion per year. Exact figures are difficult to determine because the details and even the existence of many deals are not made public.

The political forces driving this behavior by governmental actors may not be altogether straightforward, but a key factor is that job creation and retention are a very clear indicator by which political officials believe – often rightly so – that they will be judged by the electorate. Whether or not there may be ways that are more effective to spend the public revenues, the chance at a big announcement about the attraction of a large new employer to one's jurisdiction is a difficult temptation to resist. On the flipside, an elected official's re-election chances are often significantly harmed if they are blamed for the loss of a large source of employment. Offering tangible investment promotion incentives such as the tax breaks in this case is one of the most direct ways a government official can seek to influence firm location choices.Footnote 29

5.3 Contingency de jure versus de facto

In Canada–Autos, the AB for the first time expanded the scope of Article 3.1(b) SCM to not only cover subsidies de jure contingent on the use of domestic goods but also to cover de facto contingency. In doing so, the AB reversed the Panel's finding in that case, which relied on the explicit use of the term ‘de facto’ in Article 3.1(a) SCM but its absence from Article 3.1(b). Although the AB recalled its previous case law confirming that omissions should be given some meaning,Footnote 30 it also noted that different contextual elements call for a broad interpretation of the purview of this provision.

In this regard, the AB contended that the GATT counterpart of the SCM prohibition, Article III:4 covers both de jure and de facto discrimination in the use of domestic goods over imports.Footnote 31 Furthermore, the AB referred to its Bananas case law, which extended de facto discrimination also to the interpretation of Article XVII GATS. In that case, the AB contented itself in finding that, whereas the GATS national treatment provision does not explicitly refer to de facto discrimination, its ordinary meaning does not exclude it either. In the end, the AB noted that limiting the scope of Article 3.1(b) to de jure contingency only would defy the object and purpose of the SCM agreement, as circumvention would become ‘too easy’.Footnote 32

Quite interestingly, the AB did not refer to Article III:5, which appears to be the actual equivalent in the GATT of Article 3.1(b) SCM. Even if that provision was used as context, though, the result would most likely be no different: this is so because Article III:5 is also concerned about internal quantitative regulations which, directly or indirectly, require that a certain proportion of a product must be supplied from domestic sources. In other words, this provision also covers both directly (de jure) and indirectly (de facto) discriminatory regulations.

De facto contingency in general addresses the need for some kind of insurance policy against circumvention.Footnote 33 Otherwise, Members would be allowed to nullify any market access commitments previously undertaken by providing economic incentives not to buy from foreign sources. Irrespective of the importance of addressing potential loopholes of this type, the question remains as to whether the omission in Article 3.1(b) of the term ‘de facto’ should be given meaning by WTO adjudicators, notably if one takes account of the existence of additional legal means under Part III of SCM to challenge trade-distorting subsidies.

Be this as it may, existing case law suggests that no real difference exists between Articles 3.1(a) and 3.1(b) with respect to the types of contingency required (both de jure and de facto). In US–Tax Incentives, the AB summarized this attempted coherence between the two types of per se prohibited subsidies set out under Article 3 SCM. The AB clarified that contingency means that the use of certain goods is a condition, in the sense of a requirement for obtaining the subsidy. ‘Use’ may refer to the consumption of the good during manufacturing but also to the incorporation of a component into a separate good or the use of the good as a tool in the production of a good.Footnote 34 In turn, the ‘goods’ at issue can be parts or components that are incorporated into another good, materials, or substances that are consumed in the production process of another good or tools and instruments that are utilized in the process of production. The goods would typically be tradable but this is not necessarily a condition for the application of the provision.

One could discuss the raison d’être behind advancing a single legal standard for both de jure and de facto contingency. There also seems to be an inherent incoherence in the AB's reasoning: on one side, the AB suggests that the evidentiary standard cannot be the same among the two, as de facto contingency would require a holistic assessment of various elements and thus a more comprehensive analysis showing a less straightforward (than in the case of de jure contingency) but still unequivocal relationship between the measure and the use of domestic goods. As articulated by the AB, however, i.e. that a condition requiring the use of domestic goods has to be identified, the test blurs the distinction between the two types of contingency and thus is bound to be hardly – if ever – met by the complainant. Rather, one indeed would expect that a de facto contingency test would entail an analysis very similar to the one offered by the panel focusing on the identification of import substitution effects and/or a detrimental impact on importation by fostering the use of subsidized domestic inputs. To clearly distinguish it from the category of actionable subsidies and the adverse effects analysis, one would expect in this case the introduction, for instance, of a de minimis test or similar which would look into the characteristics of the market at stake.

What we find particularly problematic is the AB's finding that, contrary to its ruling in EC and Certain Member States–Large Civil Aircraft that a de facto contingent export subsidy can also be a subsidy ‘geared to induce’ the promotion of export performance, in the case of import substitution subsidy such a test would not be apposite. Recall that in EC and Certain Member States–Large Civil Aircraft, the AB found that the ‘geared to induce’ test would be fulfilled if the incentives provided are not simply reflective of the conditions of supply and demand in the domestic and export markets undistorted by the granting of the subsidy.Footnote 35 It is submitted that the AB strengthens the test only with respect to Article 3.1(b) to identify a condition requiring the use of domestic goods for no obvious reasons and with no justification provided as to why this strengthening is necessary only with regard to Article 3:1(b).

This deviation is even harder to explain because the AB otherwise follows the line adopted in EC and Certain Member States–Large Civil Aircraft to suggest that the de facto contingency is an objective standard to be established on the basis of the ‘total configuration of facts constituting and surrounding the granting of the subsidy, including the design, structure, and modalities of operation of the measure granting the subsidy.’Footnote 36 Interestingly, the AB underscores in EC and Certain Member States–Large Civil Aircraft that such a constellation does not blur the distinction intentionally drawn by the SCM drafters between prohibited and actionable subsidies. If this is the case, as we believe it is, then it becomes quite uncontroversial that the decision by the AB to strengthen the standard of review only with regard to Article 3.1(b) does not serve the inherent logic of Article 3 SCM or consistency of WTO case law.

6. Application to the case of Boeing and the 777X program

Let us examine the three factors that both the Panel and the AB point out can be relevant in establishing an objectively observable conditional relationship between a subsidy and the use of domestic over imported goods: (a) the design and structure of the measure; (b) the modalities of operation, and (c) the relevant factual circumstances relating to the granting of the subsidy. We will take them slightly out of order since the modalities of operation depend on the factual circumstances.

6.1 The design and structure of the measure

We are concerned in this section with the Second Siting Measure, which ties the tax incentives (subsidy) to the continued siting of wing assembly within the state of Washington. The design and structure of the Second Siting Provision has been discussed in detail in previous sections, notably Section 2.

6.2 The relevant factual circumstances relating to the granting of the subsidy

6.2.1 The industrial organization of the large civil aircraft duopoly

The nature of the production process for extremely large jets such as those in Boeing's 777X program is crucial for understanding the nuances of this case. Indeed, a main justification given by the AB in overturning the Panel's finding of de facto contingency is that

the circumstances present in this dispute – such as the existence of a multi-stage production process, the level of specialization of the subsidized inputs, and the level of integration of the manufacturing and assembly chain in the aircraft industry – should have received more careful consideration by the Panel.Footnote 37

There are only two firms in the world – Boeing and Airbus – that produce aircraft comparable to the Boeing 777X. Boeing has the 787 and the out-of-production McDonnell Douglas MD-11 (later produced by Boeing) and Airbus has the A330-300 and the A350-XWB as well as the out-of-production A340.Footnote 38 The main evidence we can gather as to the possibilities for the organization of the supply chain come from the actual supply chain organization for these comparable aircraft and the statements of these firms in WTO proceedings and elsewhere. The firms’ statements should not necessarily be taken at face value given the context in which they were made and what is at stake.

It seems clear that the level of specialization of the inputs is such that Boeing will not buy completely assembled wings or fuselages from an arm's length supplier. It currently does not do so and neither does Airbus, although the wings for the Boeing 787 purchased from Mitsubishi Heavy Industries were imported from Japan in almost complete form. The United States makes this claim very clearly in its submissions in this case.

The United States also argues that it is not possible for Boeing to import completed fuselages and wings for use in the production of the 777X.Footnote 39 It is not clear whether the US means that there is no arm's length firm which can supply the assembled wings or that it makes a stronger statement that the assembled wings are simply too large to ship. The latter claim, while conceivably true – the wingspan of one of the 777X models is 235 feet – is at least not obviously true since Airbus imports the wings for the A350-XWB, first from England to Germany to have the leading and trailing edges added, and then to France for final assembly – that is, to add the wings to the plane.Footnote 40

We should note that if Boeing could and did import assembled wings for the 777X, the transportation costs would be significant because of the size of the wings. While Boeing's previous large aircraft program – the 787 Dreamliner – imported almost all wing components from unrelated firms in Australasia, Boeing appears to have decided to source wing components at least domestically, if not entirely within Washington State, for the 777X.Footnote 41

Unusually high transportation costs are not the only barrier to importing assembled parts for large aircraft; conformity assessment requirements are significant in aircraft manufacturing and these costs rise with the number of distinct regulatory environments from which a firm sources components. For Airbus, to source wings within the EU for final assembly in the EU is less costly from a conformity assessment standpoint than for Boeing to import wings or wing parts from outside the US.Footnote 42

Taking for granted the US's claim that it is not feasible to buy assembled wings at arm's length, it does seem possible that Boeing could site a wing assembly plant at some distance from the final assembly plant in Washington state and import the wings within the boundaries of the firm. Whether or not it would have done so in the absence of the Second Siting Provision is a counterfactual to which we do not have an answer.

However, the existence of the Second Siting Provision is suggestive evidence that Washington State legislators were worried that Boeing might site wing assembly away from the final assembly location and in fact outside the state. If this were not possible, there is no reason for the legislature to include ‘wing assembly’ in the provision. This, however, would seem to be at odds with arguments made by the US as summarized in the Panel Report (7.258),

the United States ‘acknowledges that wing fabrication, wing assembly, and fuselage assembly are all production activities conducted in the manufacture of an airplane’Footnote 43, but argues that fuselages and wings are ‘features or elements of the finished aircraft, which are generated only through the final assembly process of the airplane itself – not inputs into the production process’.Footnote 44

These claims do not appear consistent with the fact that Boeing imports near-finished composite wings for the 787 Dreamliner and Airbus transports finished wings from Germany to Toulouse for final assembly of the A350-XWB. Furthermore, if there can be no ‘final wing’ assembly separate from final assembly as Boeing claims, then it is not clear to what activity concerning wings the Siting Provisions apply.

But the US raises a crucial question here: when is a good at one stage in the supply chain different from those at a previous stage(s) of the supply chain? We must look through the lens of modern supply chain theory to answer this question, and the SCM Agreement was written only as the personal computing revolution on which modern supply chain management is based was getting underway and thus does not necessarily clearly embody the will of the membership for industries that have complex supply chains.

For customs purposes in the United States, constituent parts must be ‘substantially transformed’ by the production process in order to be treated as a different product. When dealing with an assembly process, the courts have ruled that this standard requires that the assembly operation be sufficiently complex and require some substantial level of expertise.Footnote 45 Once a wing is attached to an otherwise fully assembled plane, it clearly stops being a wing and becomes a plane. Further, the process of assembling an aircraft from constituent parts requires a well-trained and highly skilled workforce and the process almost surely passes the ‘substantial transformation’ threshold.

6.2.2 Political economy of Boeing activity in Washington State

Boeing is the largest employer in Washington State by far. In 2013, it had more than twice as much employment as Microsoft, the second-largest employer in the state. It is hard to understate the impact of Boeing's business decisions on the Washington State economy.

Thus, when Boeing announced its intention to site a new aircraft program that would likely eventually displace at least significant parts of the current programs that are primarily based in Washington State, it is almost inconceivable that local officials would not try to attract that new program. The choice was between retaining this current high-tech employer with its tens of thousands of high-paying jobs and developing new economic activity from scratch to take its place.

Although not all of Boeing's jobs in Washington are directly related to the 777X program, the incentives offered for the siting of the 777X program could be viewed as a broader retention effort since the incentives apply to the aircraft industry and not just to the 777X program. Thus, it is up to the total of Boeing's 81,939 Washington State jobs in 2013 that politicians and/or the electorate may have seen to be at stake.Footnote 46

As context, both Boeing's total employment and its employment in Washington State had been growing and peaked in 2012 at 175,742 and 87,032 respectively. This implies that the negotiations over this incentives deal were taking place in an atmosphere of sharp employment reductions by Boeing, potentially increasing the firm's leverage. With the incentives in place since 2014, Boeing employment has continued to drop. In January 2018, Boeing's Washington State employment rested at 65,829 out of 141,322 total employees, down 24.4% from its peak, and falling to 46.6% from 49.5% of total Boeing employment in 2012.Footnote 47 In 2017, Washington lawmakers began consideration of legislation that would claw back some of the incentives if Boeing continued to cut jobs in Washington State.Footnote 48

In its report, the Panel noted ‘statements made by the Governor of Washington about the goal of keeping 777X wing production in Washington’ (para. 7.366). These kinds of political statements seem perfectly reasonable given the economic importance of Boeing to the state.

6.3 The modalities of operation

In order to evaluate whether the measures that are the subject of this dispute were per se prohibited import substitution subsidies, it is important to know the details of how Boeing might have organized its supply chain in the absence of the incentive package. However, that counterfactual is hard to determine given that Boeing likely designed its production process to take advantage of the tax incentive environment that is under examination in this case. Again, we cannot rule out that the incentive scheme was designed to take into account Boeing's supply chain plans.

It is widely claimed that the incentives package granted to Boeing by the State of Washington is the largest on record, at $8.7 billion.Footnote 49 This tax incentive package was specifically designed to convince Boeing to site the new program in Washington state, in competition with other locations, in advance of the beginning of the program. If the First Siting Provision was created to lure the 777X program to Washington state, the Second Siting Provision seems to have been specifically designed to keep it there. Recall that the very significant cut – by about half – in the B&O aerospace tax rate is withdrawn if any wing assembly or final assembly is sited outside the state of Washington. It is this wing assembly that the European Union claims forces Boeing to choose domestic over imported goods – i.e. wings.

If we take for granted the claim that Boeing cannot outsource wing assembly, as evidenced by the United States’ arguments before the Panel and the production structure of the Airbus A330-XWB, then Boeing's siting decisions for wing assembly completely determine whether the wings that are used in the 777X aircraft will be domestic or imported.

As noted above, the SCM agreement allows production subsidies that may displace imports but do not require the use of domestic over imported goods. When overturning the Panel's ruling that the subsidies are de facto import substitution subsidies, the AB's argument seems to hinge on the idea that siting of production will likely displace imports indirectly, but that siting decisions don't specifically require imports over exports so subsidies to siting are in principle allowed. However, in this case, given that all wing assembly sites must be in Washington, and Boeing will not buy wings at arm's length, it appears that the use of domestic goods is necessarily required and imports are necessarily displaced.

Here it is useful to note that the Second Siting Provision does not only privilege domestic goods over foreign goods, although that margin is the one with which the WTO's SCM Agreement is concerned. It also discriminates against wings produced in US states other than Washington. This brings the Dormant Commerce Clause of the US Constitution into play. Hellerstein and Coenen (Reference Hellerstein and Coenen1996) argue that ‘a tax which by its terms or operation imposes greater burdens on out-of-state goods, activities, or enterprises than on competing in-state goods, activities, or enterprises will be struck down as discriminatory under the Commerce Clause.’ Thus, given the AB's unwillingness to strike down the Second Siting Provision as a per se prohibited import substitution subsidy, the Dormant Commerce Clause line of attack remains open.

7. Conclusions

US–Tax Incentives is a welcome addition to the by now rich – but not always coherent – case law of the WTO adjudicating bodies relating to the scope of the SCM Agreement. This dispute raises various questions, the most important of which appears to relate to the treatment of investment promotion measures by WTO law. It also shows the potential limits that WTO adjudicating bodies may face in their mission to serve the objective of the SCM agreement to eliminate trade-distorting interventions of pecuniary or other nature in the marketplace.

Domestic content or import substitution subsidies are a clearly defined (in the WTO treaty) but quite controversial type of subsidy that the SCM agreement prohibits, along with export-inducing subsidies. The concept has become even less straightforward after the ruling in US–Tax Incentives, at least as far as the definition of contingency in fact (de facto) is concerned. We argued in this article that the AB unnecessarily blurred the distinction between contingency in law (de jure) and contingency in fact by ruling that identifying a condition requiring the use of domestic inputs would be a necessary element for a determination of a de facto contingency. This appears to be an unduly formalistic view of Article 3.1(b) that leaves little legal space for any de facto contingency claim in the future.

In addition, we believe that there was room for a sector-specific market-oriented analysis of the different elements of de facto contingency – the modalities of the measure, its design and structure, and the factual circumstances – but the AB decided to dispose of this opportunity. Rather, for the AB, this type of more meticulous analysis should be reserved for actionable subsidies which can be challenged under Part III of the SCM Agreement. In this respect, the AB may have wanted to also express indirectly its discontent that the EU did not raise an additional claim based on Article 5 SCM but instead decided to place all its bets on a rather expansive interpretation of import substitution subsidies.

However, if one takes proper account of the nature of production for large aircraft – most notably the complexity of the production process – the subsidy at stake, which is contingent on siting of wing assembly, appears to be in direct violation of Article 3.1(b). Interestingly, it is not the investment promotion incentives themselves that are a clear per se prohibited subsidy. The First Siting Provision by itself does not run afoul of SCM Article 3.1(b). But the two siting provisions, taken together, require investment in two parts of the supply chain whose relationship in this industry is such that there is no way for Boeing to use imported goods and keep the subsidy in the Second Siting Provision. It is this linking of investment promotion incentives that creates the violation. Without the Second Siting Provision, Boeing could assemble wings in, for instance, Korea or Japan where most of the wing parts are produced and then import the assembled wing to Washington State for final assembly. Under current law, if Boeing assembles any of its wings outside the state of Washington, a determination under the Second Siting Provision would mean that the reduced B&O aerospace tax rate of 0.2904% would cease to exist.

The AB overturned the Panel's ruling at least in part because it found that there was not a complete consideration of the circumstances of the dispute such as the one supplied in the previous section. Essentially, the AB ruled that the Panel did not adequately support the claim of de facto contingency. However, from our analysis above, it appears fairly hard to argue that the AB's analysis of de facto contingency was more meticulous or, even more importantly, that a de facto contingency does not exist.

The bottom line is that now that Boeing has located the final assembly facility in Washington State, if Boeing ever chooses to site any wing assembly location outside the state, the reduced B&O tax rate will be lost. The assembled wings could – in principle – either be imported within the firm or assembled locally. By requiring in the Second Siting Provision that the wings be assembled locally, Washington State is necessarily requiring this piece of the supply chain be domestic instead of foreign.

Although the SCM has been interpreted to allow domestic production subsidies that might displace imports as long as they do not require the use of domestic over imported goods, the nature of the supply chain for large aircraft means that, here, there is no difference between displacing imports and requiring the use of domestic goods. The difficulty in applying Article 3.1(b) SCM to this case arises at least in part because the Agreement was not written with a view to addressing import substitution subsidies in industries with complex modern supply chains. If it is the will of the WTO membership to address the gap that has been opened in subsidies disciplines by this case, the SCM agreement may have to be modified significantly, perhaps already by expanding the category of per se prohibited subsidies. While this appears to be secondary in the current uncertain landscape surrounding the multilateral trading system, proposals in this direction have been submitted in previous years, including by the US. This is of course not a task that can be taken lightly; important supply-chain-related considerations would need to be taken into account to ensure that the new disciplines are sufficiently future proof.