John Thelwall usually traded under his own name. ‘Character’ was intrinsic to his claim to act as tribune of the people. By the time of his arrest in May 1794, he had made himself into the most visible member of the LCS through his writing and, particularly, by lecturing at a series of venues around London. In fulfilling the Godwinian criterion of standing ‘erect and independent’ in his own name, he practised his own version of print magic.1 For Thelwall, this magic was not the bodying forth of the Word in the French Revolution, as it was for Citizen Lee, but the conjuring of the people as a ‘living body’ via the power of print.2 Thelwall’s faith was in a secular magic based on materialist notions of sympathy. He was the grateful heir to an eighteenth-century belief in the improving power of magazines and debating clubs. Sympathy for Thelwall was the ‘occult’ mechanism by which rational debate was extended into a democratic engine of change.3 His radicalism was staked on his role as a conductor of these energies in two senses of the metaphor, both animating and organising ‘the people’. In this regard, he frequently played the showman, confessedly adopting ‘the attractive veil of amusement’ to arouse the interest of his audience, providing songs for LCS meetings, and even cutting the head off a pot of beer to mime the fate of kings.4 His part in the struggle against the Two Acts at the end of 1795 was focused above all on the rights of reading and discussion being kept open to the population at large. Their passing into law eventually forced him into internal exile, away from the public spaces of the lecture room, the coffee house, and the theatre. Circumstance reinforced a tendency that had always been a part of his writing. His faith in print transposed into a more intimate medium able to bring a transformation in the individual in a way that the modern reader might recognise as a version of Romanticism. Such an understanding of ‘literature’ or something like it may emerge in Thelwall’s writing after 1795, but it never lost its political ambition, nor imagined its implied audience as isolated readers.

Associated intellect

Thelwall was always ambitious of a literary career. Born into the shopkeeping classes, the biography published by Thelwall’s second wife Cecile Thelwall in 1837 noted that from early on ‘the prospect of mingling in circles of society, more correspondent to his taste and turn of mind than those to which had hitherto been confined, had altogether formed an association intoxicating’. He was among those many who saw the expansion of the press in the last quarter of the eighteenth century as an invitation. Also like many others, he discovered that freedom of speech and the liberty of the press – keystones of the supposed palladium of British liberties – were not to be taken entirely at face value. Thelwall was involved in debating societies from the early 1780s, eventually managing the debates at Coachmakers’ Hall, but early on this interest in the intellectual buzz of London included being ‘a professed sermon hunter’.5 London’s chapels and churches were intermingled in the print sociability of magazines and debating societies, but this aspect of Thelwall’s intellectual ambition was short lived. He became impatient of religious sentiment in politics and poetry alike, perhaps most famously when in May 1796 he dismissed Coleridge’s ‘Religious Musings’ as ‘the licencious (I mean pious) nonsense of the conventicle’.6 In the 1780s, Thelwall was sending poetry of an entirely secular variety into various periodicals with ‘enthusiastic perseverance’.7 Poems on Various Subjects appeared in 1787, eliciting a notice in the Critical Review still proudly remembered in his biography.8 From around 1788 until 1791, Thelwall took over the editorship of the Biographical and Imperial Magazine. He also wrote the plays Incle and Yarico (1787) and The Incas (1792), convinced his work was being plagiarised after he submitted the manuscripts to the theatre managers.9 His later political practice contested the space of the London theatre for radical culture. He may have described himself as a ‘literary adventurer’, but the arc of his story in these years is far from unique. Citizen Lee and W. H. Reid are just two others that came to the LCS through an aspiration to join the republic of letters, but neither they nor anyone else associated with the radical societies equalled Thelwall’s fame as a performer on the public stage in the 1790s.10

Originally, Thelwall was a church and king man with pro-Tory prejudices imbibed from his father. He identified his radical epiphany not with the classic instance of reading Rights of Man, but in the attempts to close down the debating societies discussing the Regency controversy in 1789–90, followed by his experiences in the Westminster Election of 1790. From working as a poll clerk, his indignation at abuses seems to have provoked him to campaigning for John Horne Tooke, who remained a central figure in his development. Experience in the debating societies is perhaps the key to his distinctive sense of radicalism as a ‘forum’, to use Judith Thompson’s term, whereby the popular will could make itself known by the active participation of the multitude.11 Thelwall always prized ‘the energy and power of graphic delineation, which, in the enthusiasm of maintaining an argument can be produced, by the excitement of a mixed audience’.12 The point is not simply that he felt a personal buzz in face-to-face debate, which he clearly did, but that he also saw in such encounters the possibility of discovering principles that none of those involved had previously held, a democratic version of the Godwinian faith in the collision of mind with mind traceable back to Isaac Watts and Milton before him.13

Where some in the radical movement predicated their politics primarily on the delineation of clear rational principles, Thelwall saw debate as a process wherein such principles were discovered. He gave a speech at Coachmakers’ Hall on freedom of discussion worth quoting in full for what it reveals about the nuances of his idea of debate:

So far is the vulgar objection against discussion from being true – to wit – that after all their wrangling, each party ends just where it began, that I never knew an instance of men of any principle frequently discussing any topic, without mutually correcting some opposite errors, and drawing each other towards some common standard of opinion; different perhaps in some degree from that which either had in the first instance conceived, and apparently more consistent with the truth. It is, I acknowledge, in the silence and solitude of the closet, that long rooted prejudices are finally renounced, and erroneous opinions changed: but the materials of truth are collected in conversation and debate; and the sentiments at which we most revolt, in the warmth of discussion, is frequently the source of meditations, which terminate in settled conviction. The harvest, it is true, is not instantaneous, and we must expect that the seed should lie raked over for a while, and apparently perish, before the green blade of promise can begin to make its appearance, or the crop be matured. But so sure, though slow, in their operations, are the principles of reason, that if mankind would but be persuaded to be more forward in comparing intellects, instead of measuring swords, I can find no room to doubt, that the result must be such a degree of unanimity as would annihilate all rancour and intolerance, and secure the peace and harmony of society. In short, between all violent difference of opinion, there is generally a medium of truth, to which the contending parties might be mutually reconciled. But how is this to be discovered, unless the parties freely compare their sentiments? – If discussion be shackled, how are discordant opinions to be adjusted, but by tumult and violence? If societies of free inquiry are suppressed, what power, what sagacity, in such an age as this, shall preserve a nation from the convulsions that follow the secret leagues and compact of armed conspiracy.14

If the Life of John Thelwall’s account is to be trusted, the speech cannot have been made later than 1792, when the debating society at Coachmakers’ Hall was shut down, but there is much in the version printed there that sounds like Godwin’s Political justice, not published until the beginning of the following year.15 The stress on the collision of mind with mind balanced against the final authority of the deliberations of the closet is typical of Godwin, as is the idea of the slow harvest of truth, but it was made in the sort of venue where Godwin rarely ventured, if at all. The most likely occasion for the speech would seem to have been the debate of 24 May 1792, just three days after the Royal Proclamation against seditious writings. According to the Gazetteer, the question was: ‘Are Associations for Political Purposes likely to promote the happiness of the people, by informing their minds, or to make them discontented without redressing their grievances?’16 For Thelwall, such debates came to be regarded not simply as a forum of exchange but as the alembic of print magic, wherein those involved in reading and discussion might come to know themselves as ‘the people’ by their interactions with each other. Over 1795–6, this aspect of his development produced a remarkable series of reflections on the formation of a collective consciousness among the labouring classes: ‘Hence every large workshop and manufactory’, he wrote in his Rights of Nature, ‘is a sort of political society, which no act of parliament can silence, and no magistrate disperse.’17

Thelwall always admitted to being enthusiastic by nature, liable to being swept up by the experience of being part of and speaking to a crowd, but his ideas on sympathetic transmission were underpinned by theoretical reflection on ‘certain immutable laws of organic matter’.18 Thelwall was immersed in debates about materialism and the relations between mind and body from at least as early as his editorship of the Biographical and Imperial Magazine.19 In the early 1790s, he was living in Maze Pond in the Borough, very close to Guy’s and St Thomas’s hospitals. Always drawn to sites of intellectual exchange, he soon became involved in a weekly medical debating club at Guy’s called the Physical Society. The apothecary James Parkinson – Eaton’s ‘Old Hubert’ – was also a member.20 Thelwall delivered two papers at the society in 1793. The first, on 26 January, vigorously debated over six weeks, was published as An Essay, Towards a Definition of Animal Vitality. Thelwall’s essay took the position that organised matter was the foundation of life, but only when united with a vivifying principle he compared to electricity. At the end of the year, another paper seems to have led to him withdrawing or being excluded from the Physical Society, at just the time he was starting to make a name for himself as a lecturer to the LCS. Materialism linked with a democratic politics was too rich a mixture for most of those at the Physical Society. Thelwall later claimed that magazines that had previously been accepting his writing enthusiastically began to reject his work at around this time. The publication of his distinctive prose medley The Peripatetic was delayed when the printer who produced the first volume threatened to withhold the manuscript if Thelwall refused to remove the politics. The second and third volumes did appear, but sold by Daniel Isaac Eaton. Four decades later, Thelwall’s biography claimed that the episode showed him that ‘he must be either a patriot or a man of letters’.21 The binary in this judgement may reflect a nineteenth-century perspective. In the 1790s, the print networks of the LCS held both paths open to him simultaneously; if, that is, one allowed that a ‘man of letters’ could thrive in its circuits of print, sociability, and performance.

The Peripatetic is shot through with Thelwall’s sentimental materialism, creating a sense of a community interlinked by natural bonds of sympathy, ‘a kind of mental attraction’, he claimed, ‘by which dispositions that assimilate, like the correspondent particles of matter, have a tendency to adhere whenever they are brought within the sphere of mutual attraction’. One of the most arresting features of The Peripatetic is the way it builds an auto-critique of the aesthetics of sensibility into its own narrative, acknowledging a debt to Sterne, then distancing itself from the idea of the ‘feeling observer’ absolved from political responsibility. ‘The subject of our political abuses’, he wrote in the preface,

is so interwoven with the scenes of distress so perpetually recurring to the feeling observer, that it were impossible to be silent in this respect, without suppressing almost every reflection that ought to awaken the tender sympathies of the soul.22

These were the aspects of the book that caused the printer to interrupt its production. Thelwall’s materialist sense of a sympathetic universe shaped not just his poetry and prose, but also his lecturing and debating. Even the King Chanticlere allegory that Eaton published in Politics for the People was originally an intervention in a debate on the life principle that clearly owed something to his discussions at the Physical Society.23

Thelwall always approached the body politic as animated by ‘that sort of combination among the people, that sort of intelligence, communication, and organised harmony among them, by which the whole will of the nation can be immediately collected and communicated’.24 His writing and lectures he understood as imparting an electrical energy to give life to a ‘public’, but he also conceived organisation to be part of the process of bringing together into a single body the dispersed members to be animated.25 An external spark can only work on matter that is internally organised:

If the people are not permitted to associate and knit themselves together for the vindication of their rights, how shall they frustrate attempts which will inevitably be made against their liberties? The scattered million, however unanimous in feeling, is but chaff in the whirlwind. It must be pressed together to have any weight.26

Thelwall later saw the importance of the LCS as its facilitation of this process:

In fact it cannot be said that up to the time of forming the societies to be mentioned hereafter, there was positively what we now call an ‘English public’, or in other words an union of opinion of the majority of all classes upon one given subject.

In Life of Thelwall, these sentiments are surrounded by a discussion of the ease by which ‘the mass of the people, could be led into such acts of riot and confusion’, a fact imagined as surprising to the nineteenth-century reader. In the 1790s, there was a more radical edge to his idea of ‘the mass of the people’, not least in his insistence on its role as a constituent power that could presume to challenge the authority of the Crown-in-Parliament. For several months from November 1793 to his arrest on a charge of treason in May 1794, Thelwall devoted himself to exploiting all kinds of media in a variety of spaces to work the magic of conjuring ‘the people’ from ‘the scattered million’.27

The political showman

Thelwall’s first involvement with the societies seems to have been in April 1792 at the Borough Society of the Friends of the People, not to be confused with Grey’s aristocratic group. He was also part of the more elusive London Society of the Friends of the People, which had close relations with the Borough Society. Neither long outlasted the emergence of the SCI and LCS as the coordinated leaders of radicalism in the metropolis.28 Thelwall devoted much of his energy in 1792 to preserving the debating societies against attempts to harass them out of existence after the Royal Proclamations of May and November. He also joined the Society of the Friends of the Liberty of the Press. The published account of their meeting called to celebrate Erskine’s defence of Rights of Man describes him as ‘A Mr. Thelwall, whose oratory is well known at Coachmakers’ Hall, and other places of public debate’. His contribution was to reprobate ‘with much vehemence the dangerous conduct of those Associations, who came forward to support the allegations of the existing powers – right or wrong’.29 Despite the condescension implied in the ‘A Mr. Thelwall’, his performances at the Society seem to have brought him to the attention of the Opposition. After describing the travails faced by Thelwall in getting The Peripatetic published, Susan Thelwall’s March 1793 letter to her brother mentions that various Foxites had enquired after him and offered their support, including ‘your Mr. Edwards’.30 Gerard Noel Edwards, MP for Rutland, the county where her family lived, took the chair at the Society of Friends of the Liberty of the Press meeting in December 1792; presumably he subsequently showed an interest in The Peripatetic. Edwards did not attend the Society’s March meeting because he disapproved of transacting business ‘at places for public dinners’, but sent a letter professing support for the liberty of the press, on which Sheridan made humorous remarks from the chair. Whether out of principled qualms about such aristocratic connections or for other reasons, Thelwall did not ultimately pursue the path of patronage. Instead, he joined the LCS in October 1793, introduced to the society by Joseph Gerrald, another member of the Friends of the Liberty of the Press.31

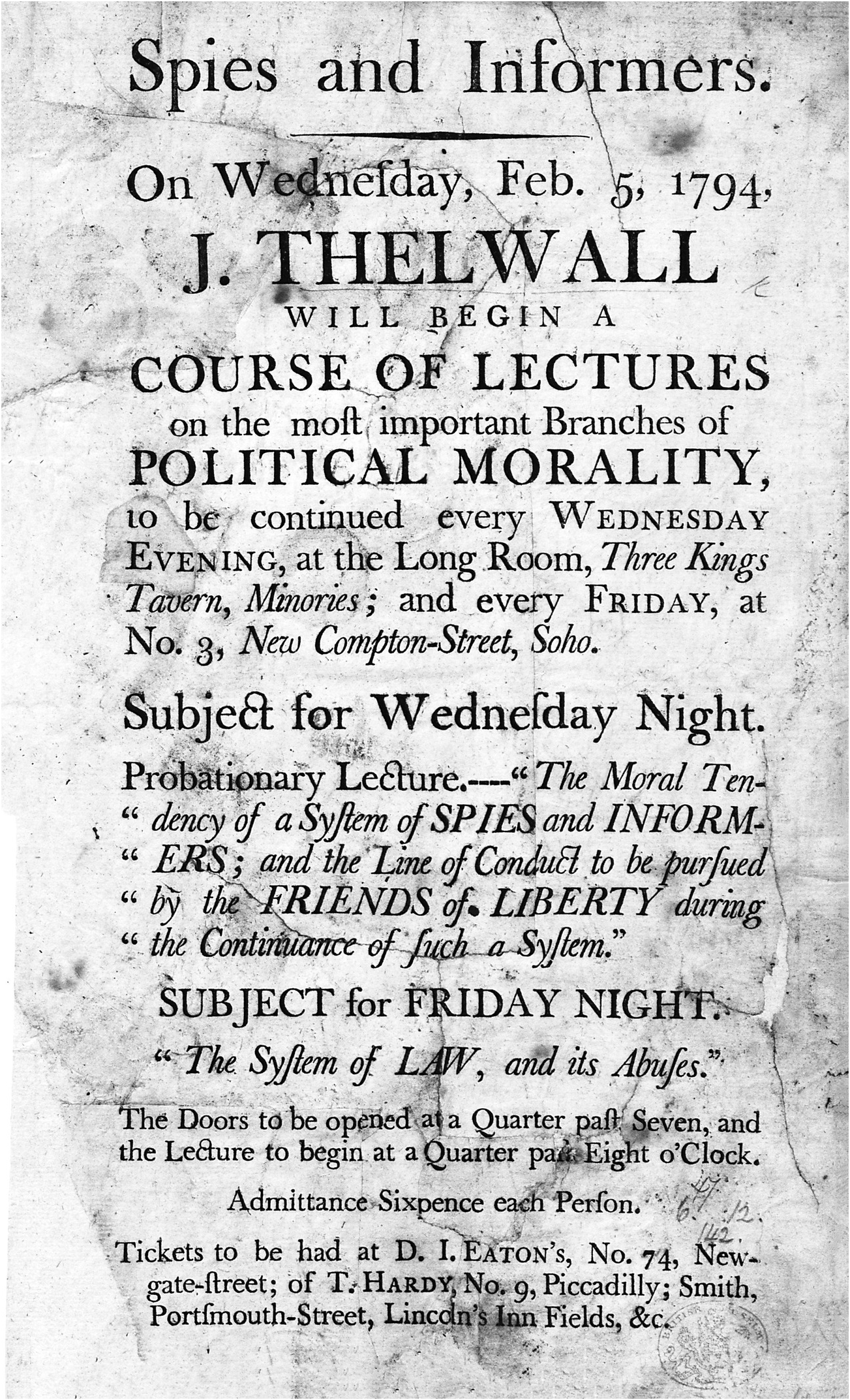

Thelwall stood for election as a delegate to the Edinburgh Convention soon after joining the LCS, but his candidacy fell on the rule excluding those who had been members for less than three months. Instead in November 1793, the month he made his striking intervention at the debating society at Capel Court, he offered to lecture from Godwin’s Political justice to raise money for the expenses of the delegates. Given initially at 3 New Compton Street in Soho, these lectures made his name in the LCS.32 From at least early 1794, he began offering repeat shows of the lectures north and south of the river. The venue north of the river continued to be Compton Street, an address friendly to the LCS because a member – John Barnes – ran a coffee house there.33 The other was in Thelwall’s home ground of the Borough, at the Park Tavern, in Worcester Street, where he also tried to set up a society for ‘free political debate’. The Morning Post (10 February) announced a repeat performance of his popular lecture on ‘the Moral tendency of a System of Spies and Informers’. There was also to be a debate on the relative harm of the principles and conduct of the American War as opposed to the struggle against France. The advert only alerted his enemies to the event at the Park Tavern and a riot broke out. Thelwall soon gave an account of what happened as a triumph of self-restraint in the face of loyalist attempts to provoke a violent response, but he was driven north of the river to the Three King’s Tavern in the Minories. The respite was only brief. The landlord there was threatened with the loss of his licence.34 On 19 February, Thelwall took out newspaper advertisements announcing that he would now lecture twice a week in Compton Street, until ‘a proper Room can be provided and fitted up for the purpose’. His ambition was a venue where ‘the best Accommodations will be established for Ladies and Gentlemen’, an ambition perhaps only finally met when he took up residence in Beaufort Buildings in April 1794.

During these months of uncertainty, Thelwall received a letter from a former member of the Southwark Friends of the People named Allum, who had migrated to the United States.35 This letter accused Thelwall of backsliding from the cause of liberty. A wounded Thelwall began drafting a reply on 13 February – never sent – in which he defended himself as ‘for the 4 or 5 months past, almost the sole labourer upon whom the fatigue, the danger, & the exertions of the London Corresponding Society (the only avowed sans culottes in the metropolis) have rested’. If this somewhat exaggerated his role, then it did provide a reasonable summary of his activities since the end of 1792:

I have been frequenting all public meetings, where anything could be done or expected; have been urging & stimulating high & low, & endeavouring to rally & encourage the friends of Freedom. I have been constantly sacrificing interest, & security, offending every personally advantageous connection, till ministerialists, oppositionists & moderées hate me with equal cordiality.

To the charge that he was a ‘Brissotist’, he gave a more equivocating answer. First, he defended Brissot and his colleagues as true republicans whose virtues and abilities he appreciated. Next, Thelwall argued that ‘the prevailing party [in France] are too ferocious, & too little scrupulous about shedding human blood’, although like many others, Merry included, he thought allowances should be made ‘for the situation in which the despots of Europe had placed them’. He went on to blame Robespierre and his allies for acting with the ‘bigoted vices of the Priesthood, they would silence our doubts with their loud & injurious dogmas’. Nevertheless, Thelwall insisted to Allum, ‘I am a Republican, a downright sans culotte though I am by no means reconciled to the dagger of the Maratists’.

For Thelwall, typically, it was less important to identify a specific political position in relation to Brissot or Marat, than to argue and fight for ‘the right of public investigation upon political subjects’. The newspaper advertisements were a self-conscious strategy in this regard. Thelwall told Allum he understood his lectures to be ‘until lately given privately, that is to say without advertisement’. He was identifying the moment when he switched from ‘private’ lecturing to the membership of the LCS to a broader audience of ‘Ladies and Gentlemen’. More mundanely, the letter notes he was forced into the newspapers because the magistrates ‘have stripped the town of my posting bill’. (see Figure 10). Then Thelwall gave a full account of the events at the Park Tavern. Having failed to intimidate the landlord, the magistrates sent constables and a motley crowd to interrupt discussion by roaring out ‘God Save Great Jolter Head’. The letter ends with a promise to send the latest political pamphlets across the Atlantic, but cannot resist a dig at the state of society and politics in America: ‘I fear you are somewhat short of the true sans culotte; that you have too much reverence for property, too much religion, & too much law.’ At Thelwall’s trial, the letter was produced in court as evidence of his commitment – not in ‘abstract speculation’, as Serjeant James Adair put it, but as an avowed sans culottes – to a Convention. The prosecution ignored the reservations about Brissot and Marat. The final sentence was used to show that Thelwall’s politics had gone even beyond anything espoused in the new republic of the United States: ‘Republicans of this country had hitherto viewed America with an eye of complacency, but according to Mr. Thelwall, she had too great a veneration for property, too much religion, and too much law.’36 Appearing in Thelwall’s defence, Erskine insisted that the letter had never been sent because it did not reflect his settled opinions. He put its tone and temper down to Thelwall’s habitual enthusiasm, an aspect of his character repeatedly stressed by defence witnesses at the trial.37 The prosecution presented this enthusiasm as revealing the real intentions behind Thelwall’s lecturing.

Fig 10 John Thelwall, Spies and Informers. On Wednesday, Feb. 5. 1794, J. Thelwall will begin a course of lectures on the most important branches of political morality, etc. [A posting bill.]

The government and their supporters piled up the evidence that Thelwall had tried to reach the widest possible audience across a range of media. They produced copies of the songs he had circulated in the LCS (on sale at the doors of the lectures); brought up anecdotes like the decapitation of the pot of beer; and provided detailed accounts of his lectures from the spies. The treason was in the performance, they effectively argued, although, of course, this made it difficult to bring as evidence against him. The same difficulty faces anyone writing on any performance history, where what happened has to be pieced together from eyewitness accounts, published scripts, and other sources. The irony of the government’s surveillance of Thelwall, as with much of the archive of the LCS, is that it leaves a rich and diverse performance record for 1794–5.

His lecture notes are preserved in the Treasury Solicitor’s papers with the letter to Allum and other personal papers seized at his arrest. Thelwall had published some of the lectures in early 1794 and again after his acquittal, but he was left complaining that others – seized by the Bow Street Runners at his arrest – were never returned.38 The printed versions of Thelwall’s lectures need to be treated with an awareness of their distance from what went on in the lecture room. Years later Hazlitt staked his distinction between ‘writing and speaking’ on recollections of Thelwall’s ‘very popular and electrical effusions’.39 In the published versions, Thelwall admitted tidying up for ‘stile’; and sometimes backed away from the ‘levity’ left in some of the printed texts, including his joke about ‘those wicked sans culottes having taught the new French bow to the innocent and unequivocating Louis’.40 Spy reports offer another glimpse into the asides and extempore comments that gave his performances some of their spice, even if their accounts were gingered up for consumption of the law officers. John Taylor’s reported that Thelwall’s fast-day lecture began with ‘a strain of pointed irony’. This included reading from Isaiah 58 on the true spirit of fasting. Apparently Thelwall stopped to ask his audience sarcastically whether one could be charged with sedition for reading from the Bible. Thelwall frequently read from other authors, including Gibbon and Godwin, and commented on what he read as he went along.

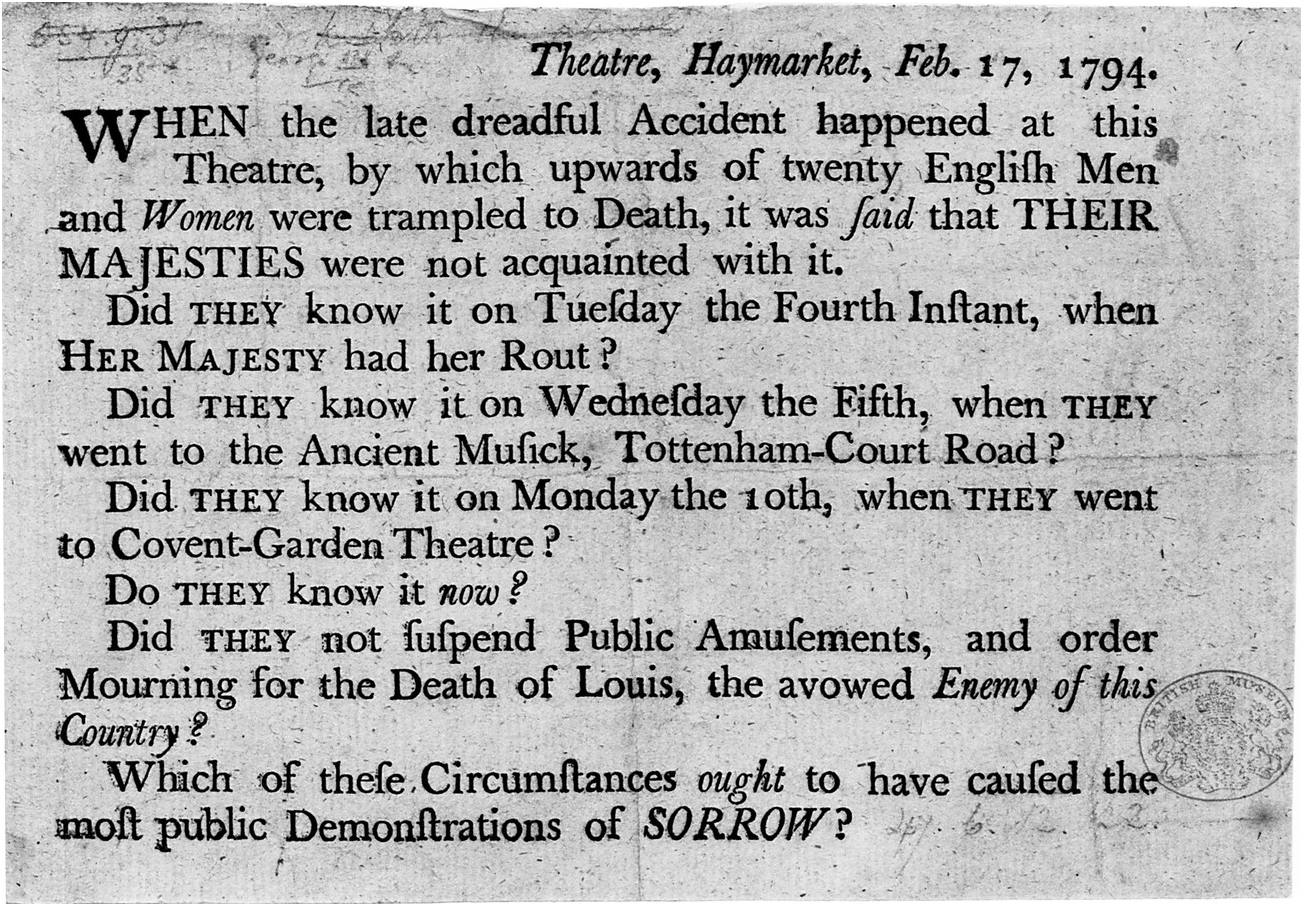

Taylor reported in detail on Thelwall’s lectures and gave evidence at the treason trials, including a full account of his attempts to exploit a performance of Venice Preserved at Covent Garden. At the Compton Street lecture on 31 January, Thelwall apparently feigned surprise at a play being granted a licence when so ‘full of patriotic and republican sentiments’. Originally written ‘with a view of paying his [Otway’s] court to Charles II’, as Thelwall recognised, sections had already been appropriated for the radical canon.41 Thelwall told his audience that he would attend Covent Garden with his friends and then read a conspiratorial dialogue between Pierre and Jaffeir aloud, because he was certain the words of ‘some hireling Scribbler’ would be interpolated. He promised to stand up in the pit if that were the case and give the dialogue in its proper form. Taylor went to the theatre on 1 February, where he heard an undoctored version of the dialogue performed. Thelwall and twenty of his friends encored it loudly.42 Only a few days later, tragic events at the Royal Theatre, Haymarket, gave Thelwall a further opportunity to exploit the theatre for radical publicity. On 3 February, the king and queen and the six princesses all attended the newly reopened Haymarket for the first time. According to The Times the next day, such was the rush of the crowd to see the Royal Family that fifteen or more people died in the crush. Taylor reported that Thelwall commented on the tragedy at his next lecture: ‘though there was no sorrow expressed for the loss of 20 English subjects, yet there was mourning for Louis, who had been a determined enemy to this country’. He did not stop there, but printed slips and distributed them in the theatre a fortnight later (see Figure 11). Did the Royal Family not know what had happened at the Haymarket, Thelwall’s printed sheet asked the theatregoers? Why did they not show the same grief for their own subjects, it continued, they had shown for the death of the king of France? Outraged by Thelwall’s effrontery, John Reeves sent to the law officers one of ‘a great Number which were dropped upon the stair case of the first gallery at the Haymarket theatre this evening’.43

Fig 11 When the late dreadful accident, etc. [A handbill charging the king with callousness in regard to the accident at the Haymarket Theatre, 3 February 1794.] [London, 1794]

This was precisely the period that Thelwall started taking out advertisements in the newspapers for his lectures, some of them appearing in the same columns as Monsieur Comus’s ‘New Philosophical Deceptions’, another possible source for Merry’s Pittachio pasquinade. Thelwall was a showman himself. A performance of his lecture ‘On the Moral tendency of a System of Spies and Informers’ used the theatrical device of telling readers it would be ‘positively the last time’. He had already been doing repeat performances ‘on account of the great overflow’, as he put it in an advertisement that also offered The Peripatetic and the Essay on Animal Vitality for sale at 9s and 2s 6d respectively. Self-consciously appearing in the newspapers, as we know from the Allum letter, Thelwall was reorienting to an audience beyond the LCS, but not simply as self-advertisement. His lectures covered familiar ground comfortably within the pantheon of British liberties, such as the trial of Russell and Sydney, but associated them with Margarot and Gerrald, not to mention his own resistance to state power. He inserted himself in the martyrology along with Gerrald, Muir, and the others prosecuted for their part at the Edinburgh Convention. By going ‘public’ with his lectures, as he put it, Thelwall was standing forth not as someone involved in the private cabals of conspirators – as the LCS were soon to be presented at the treason trials – but in the open discussion of political principles, defending the liberty of the press, and free to contest spaces of publicity like the theatre and other venues in the contact zone of urban sociability.

Alarm at the success of the lectures grew over the early months of 1794. Their heady mixture of indignation and comedy prospered. At Thelwall’s trial, Taylor reported that the Tythe and Tax Club handbill had been read out as part of the mockery of the fast day at the lecture of 28 February.44 An account of his lecture at Compton Street on 21 March noted the presence of Eaton, lately acquitted for the Chanticlere allegory. He and the foreman of his jury were radical celebrities in the audience. The growing sense of the lectures as public events is palpable. An audience, not just radicals, was drawn to see what the fuss was about. A friend of Sir Joseph Banks was induced by the newspaper advertisements to go to Compton Street, close to the scientist’s house in Soho Square. He wrote to Banks shocked at what he had heard and seen, torn between contempt and the reluctant admission that he had been impressed by Thelwall’s oratory. The expectation had been to hear ‘the low jargon of some illiterate scoundrel’. Instead Thelwall delivered ‘a most daring & biting Philippic against Kings, Ministers, & in short all the powers that be, deliverd in bold energetic terms, & with a tone and manner that perfectly astonish’d me’. The letter credits Thelwall with deploying a ‘force of argument, & an enthusiasm of manner scarcely to be resisted, indeed the effect was but too visible on the audience, many of whom were by no means to be rank’d with the lowest Order of the people’. A genuine fear of Thelwall’s communicative power comes off the page. Banks forwarded the letter to the law officers and revealed ‘Mr Reeves & myself have Frequently convers’d on the subject of Mr. Thelwall’s lectures & we agree wholly in opinion that their Tendency is dangerous in the extreme’. He assumed that Reeves had already discussed the matter with government.45 In May, Reeves attempted to bring a charge of seditious libel to the court of the Liberty of the Savoy, in whose jurisdiction Beaufort Buildings stood. When the court threw the application out, Reeves tried again with a charge of public nuisance and even arranged for a newly sworn jury to attend Thelwall’s next lecture.46 Aware of what was happening, Thelwall wrote for advice to John Gurney, fresh from his success defending Eaton. ‘Avoid any harsh observations upon the King or Monarchy, & Aristocracy’, Gurney advised. ‘You may say what you please of Reeves’s Associations.’47 Conscious of Thelwall’s tendency to extemporise, he also told him to immediately explain away anything he said that might be construed as seditious; to employ a short-hand writer to guard against misrepresentation; and to speak coolly. With the help of Joseph Ritson, who held a legal office in the Liberty of the Savoy, Thelwall escaped this charge, but the reprieve did not last long.48

Just five days after the charge of public nuisance was thrown out, Thelwall was arrested. Charged with treason, he now faced the death sentence if found guilty rather than the lighter penalties that came with the earlier charges. Taken into custody at an LCS meeting at Beaufort Buildings called to discuss the arrest of Hardy, the government also seized his papers and books, including Godwin’s Political justice, Johnson’s Dictionary, Darwin’s Botanic Garden, and Blackstone’s Commentaries.49 The government’s case, as we have seen, was that the convention proposed by the LCS was an attempt to usurp the authority of Parliament by claiming to represent the people directly. Thelwall had publicly alluded to the possibility of such a meeting in his lectures and played a leading part in drawing up plans.50 He prepared a defence while he was in prison, but Erskine dissuaded him from giving it in court. He published it after his acquittal as Natural and Constitutional Right of Britons (1795). Although later in life he claimed to have argued against calling the convention at the LCS–SCI meetings, his published defence turns more on the meaning of the word and the question of whether calling a ‘convention’ really constituted an overt act of treason. Characteristically, Thelwall insisted that ‘we attempted so to organize the public opinion that it might be made known to the representative, and Ministers, if that opinion really is in favour of Reform, might have no pretence for refusing our just desire’.51 No wonder his defence team did not want him to make this speech in court, as he was conceding the idea that the LCS saw itself as able to organise the will of the people into an articulate form, precisely the role Parliament supposed itself to fulfil.

Early on in his imprisonment, Thelwall asked the prison authorities to provide him with pen and paper. He used them to prepare a new course of lectures; wrote the defence published as Natural and Constitutional Right; and composed a series of poems published in sympathetic newspapers, including the Politician.52 As the Politician quickly folded, only two of those Thelwall promised appeared, but he prefaced them with a letter to the editor that denied he ever represented himself as ‘without comfort, and almost without hope’, as some of the newspapers had reported. This issue he saw as ‘certainly of considerable consequence to my own reputation, that my conduct and sentiments upon that occasion, should be accurately represented’, but also insisted upon ‘the importance of character in the present crisis’.53 Personal moral integrity was to be of increasing importance to Thelwall’s identity as an author. He staked much on his ‘heart’, as Coleridge recognised in 1796, when he told Thelwall he would trust his morals but not those of many other radicals on that basis.54 Thelwall’s self-representations acknowledged – as he had in court – that he was sometimes apt to run away into enthusiasm with the strength of ‘social ardor’, but frequently used the admission as a vindication of the authenticity of his feelings.55

The poems finally gathered together as Poems written in Close Confinement (1795) were devoted to the idea of an imaginative sympathy that bound Thelwall to his comrades. Print is the medium of dissemination, but its magic is imagined to transcend media and enter into the immediacy of a connection between persons. ‘Stanzas, Written on the Morning of the Trial, and Presented to the Four Prisoners Liberated on the Same Day’ celebrates the ability of the individual consciousness to reach beyond its own condition and partake in the benefits of ‘social joy’ felt by his liberated compatriots:

From these social considerations, he moves on to imagine the power of his own sufferings ‘To benefit mankind’. The expansive movement is implicitly staked on the authority of his own character, understood as a tuning fork that vibrating in harmony with the animated universe. From this period, Thelwall’s many invectives against spies and informers intensified in relation to an idea of the integrity of his private character and the authenticity of his domestic relations. Often intrusions into this sphere were represented as form of ‘Gothic intrigue and exploitation’, as McCann puts it. Merry and Pigott exploited the same trope, but their French materialist ideas of a domain of free nature opposed to aristocratic domination were often represented in terms of erotic release. Thelwall lectures and writing were much more focused on the domestic arrangements of the family unit, ‘a model of unmediated communality’, as McCann describes it, ‘free from the distorting effects of power relations’.56 Susan Thelwall may have styled herself a ‘female democrat’, as we saw in Chapter 1, but Thelwall’s writing in 1794–5 only occasionally acknowledged the idea of a ‘female citizen’ in any explicit sense.57

Acquitted felon

When he emerged from court Thelwall was understandably exhausted and decided to withdraw from the LCS. Although he claimed to have become a full convert to its goals of universal suffrage and annual Parliaments in the Tower, the early months of 1795 saw him acting on his own behalf. Horne Tooke, whom he considered in the light of his ‘political father’, advised him to withdraw from politics entirely, but he did not.58 The poems were gathered together with others under his name and brought out as a single volume with an epigraph from Milton’s Comus. The paratext might seem to signal a reorientation to an idea of literary culture as a form of leisured reading in private, but the poems scarcely point in that direction, as we have seen. In his first lecture On the moral tendency of a system of spies and informers, reprinted early in 1795, he had told his audience that this was ‘no season for indulging the idle sallies of the imagination’. He explicitly ‘renounced myself those pursuits of taste and literature to which from my boyish days, I have been devoted’.59 Interestingly, as McCann points out, these renunciations were immediately followed by a poem in the published version of the lecture.60 Elsewhere in his lectures Thelwall explicitly identified the category of ‘literature’ with the rise of the printing press as we saw in the first chapter. His sketch of the history of prosecutions for political opinions celebrated ‘the morning star of literature, the harbinger of the light of reason’.61 Implicitly he was opposing the idea that the ‘man of letters’ could not properly be a politician, just as he had critiqued aesthetic ideas of sensibility that excluded the sufferings of the poor in The Peripatetic. In line with this set of assumptions, when Thelwall published his poems from the Tower in 1795, he also recommenced his lectures at Beaufort Buildings, advertised in the volume of poetry.62 The lectures themselves, published together in the Tribune from March, urged his listeners and readers to think of themselves – ‘the whole body of the people’ – as the constituent power of the nation.63 Popular discussion, stimulated by the lectures themselves, was the crucible in which the people would make itself known as this ‘whole body’.

Thelwall rejoined the LCS in response to the mass meeting it called for 26 October, three days before the opening of Parliament. He spoke at the meeting along with those who had risen to the fore in his absence, like John Gale Jones, and old allies (sometimes adversaries) like Richard Hodgson. It was in the midst of this struggle that he received a blow from an unexpected quarter in the form of Godwin’s Considerations on Lord Grenville’s and Mr Pitt’s bills (1795). On the face of it, Godwin wrote as an ally in the struggle against the Two Acts. His strategy was to present the acts as unnecessary measures against philosophical inquiry, but in the process Godwin reiterated the doubts about popular assemblies from Political justice. The absence of men of ‘eminence’ from LCS meetings, according to Godwin, meant that there was no one to ‘temper’ their excesses. He goes on to imply that Thelwall himself, like an errant magician’s nephew, could not direct the spells he was raising. Granting at least that Thelwall always showed ‘uncommon purity of intentions’, Considerations suggests that Thelwall was not able to exercise the control Gurney had recommended to him back in 1794:

The lecturer ought to have a mind calmed, and, if I may be allowed the expression, consecrated by the mild spirit of philosophy. He ought to come forth with no undisciplined passions, in the first instance; and he ought to have a temper unyielding to the corrupt influence of a noisy and admiring audience.

Once animated, the interest of the crowd – constituted of ‘persons not much in the habit of regular thinking’ – kindles into enthusiasm, and the infection overwhelms the speaker. Literature requires leisure to consume, and Godwin saw as integral to the reading process a system of regulation lacking from the unreflective sphere of the lecture and other public assemblies:

Sober inquiry may pass well enough with a man in his closet, or in the domestic tranquility of his own fire-side: but it will not suffice in theatres and halls of assembly. Here men require a due mixture of spices and seasoning. All oratorical seasoning is an appeal to the passions.64

There was much here for Thelwall to take offence at, not least because Godwin had attended his lectures at least twice and knew they attracted a mixed audience of curious gentlefolk, Amelia Alderson among them.65 She shared something of Godwin’s view, but better anticipated the response it would meet in radical circles: ‘I fear my admiration of them has deprived me in the opinion of many of all claims to the honourable title of Democrat.’66 Thelwall complained that ‘the bitterest of my enemies has never used me so ill as this friend has done’.67

The sting must have been even sharper because Godwin spoke to a fear Thelwall sometimes acknowledged himself.68 In his speeches, including the one he made at Copenhagen Fields, Thelwall constantly urged orderliness on his listeners. He conceded in his answer to Godwin that the philosopher-politician had to act with ‘a caution bordering on reserve’ in case, ‘by pouring acceptable truths too suddenly on the popular eye, instead of salutary light he should produce blindness and frenzy’.69 Thelwall had a complex sense of the irrationality of the mob. Usually, he identified it with popular religious feeling or ‘enthusiasm’ in the most common eighteenth-century sense of the word. His lectures had pointedly contrasted the principles of the French Revolution with those of seventeenth-century Puritans:

They had light indeed (inward light) which, though it came not through the optics of reason, produced a considerable ferment in their blood, and made them cry out for that liberty, the very meaning of which they did not comprehend. In fact, the mass of the people were quickened, not by the generous spirit of liberty, but by the active spirit of fanaticism.70

No wonder, he was particularly furious that Godwin implicitly compared him with Lord Gordon, whose spectre had haunted the LCS throughout its brief life. Thelwall thought his own materialism was a more rational form of belief, even if he also recognised his own tendency to be overwhelmed by ‘social ardor’. Underneath this general anxiety about the mob was also a more particular question about the workings of a democratic culture. Convention politics, as we saw in Part I, necessarily raised the question of how to represent the will of the people, as Thelwall himself put it, ‘with the greatest purity’.71 From at least Natural and Constitutional Right onwards, Thelwall showed he understood this issue not just in terms of the articulation of a prior will by the radical orator, but also a necessary process of shaping and mediating the population at large into an understanding of itself as ‘the people’. Nevertheless, he remained firm in his belief that the crowd could form itself into a public without the help and assistance of the radical societies and its spokesmen. ‘I am a sans culotte!’ he declared,

one of those who think the happiness of millions of more consequence than the aggrandisement of any party junto! Or, in other words, an advocate for the rights and happiness of those who are languishing in want and nakedness! For this is my interpretation of a sans culotte:- the thing in reality which Whigs pretend to be.

The equivocations in this passage are pure Thelwall, shifting between the poles of a British tradition of liberty and the French example, but always insisting that ‘the thing in reality’ would only ever be made manifest by freedom of association and discussion.

Thelwall’s faith that this transformation could be managed pushed him to continue his lecturing under various guises until he was beaten into an internal exile.72 In the letter he wrote to accompany copies of his Rights of Nature sent to the divisions at the end of 1796, he had insisted on seeing reading as more than a privatised exercise.73 His book was to be read and discussed within the context of a popular association. Pushed further into exile, when he began an important dialogue with Coleridge and Wordsworth, it would hardly be surprising to see him internalise this pattern, to look within him to a paradise happier far, and abandon the idea of the reader-citizen of the debating societies and lectures. When in February 1801 Thelwall wrote to Thomas Hardy about the imminent publication of his Poems Chiefly Written in Retirement (1801), he framed the letter in terms of ‘the Age of Paper Circulations’. Developing the pun on the paper currency and print culture, Thelwall told Hardy that he intended to trade ‘under the Firm of the Apollo & the Nine Muses’ and sought advice ‘as to the means of getting as many of notes negociated as possible’. He explained to Hardy that ‘having bought a house with my credit’, he would ‘pay for it with my brain’.

The preface to the published volume presents the poet as the natural man casting the radical aside: ‘It is The Man, and not The Politician, that is here presented.’ Thelwall seems to accept the very terms used against Merry, associating the man with the poet against the erring radical, explicitly identifying the independent poet and man with the individual property owner. In one sense, the orbit of Thelwall’s sympathy had shrunk to an attenuated form of ‘paper circulation’, cut off from the culture of discussion and debate that he imagined animating the reception of Rights of Nature.74 Within the volume many of the poems also dwell on the sanctity of the family, but not in any simple sense as a domain of authenticity opposed to the political. As Andrew McCann and Judith Thompson have shown, the poems continually advert to the contingencies that have forced Thelwall into retreat. The Two Acts had largely closed down the terrain of reading and debate that framed his most expansive definitions of ‘literature’. Moreover, his correspondence with Hardy still implies an active if vestigial network of readers, clustered, perhaps sheltered against the storm, in particular places, certainly, but still imagined as connected to a larger circuit of sympathy.

The networks of readers for the poems were to provide the audiences for the provincial lecture tours Thelwall undertook from 1802, disparaged, with the poetry, by Francis Jeffrey.75 Poems written Chiefly in Retirement may hint at the idea of literature as a distinctive agency of change in itself, bringing about an epiphany of sorts within individual readers familiar from the literature of Romanticism, but this development was never absolute and Thelwall never snapped his baby trumpet of sedition, to use Coleridge’s phrase. The first in the series of ten effusions published in Poems written Chiefly in Retirement as ‘Paternal Tears’ was dedicated to Joseph Gerrald, as McCann points out, explicitly linking his private grief to the political relationships of the 1790s. Even when closest to Coleridge, Thelwall seems to have refused the poet’s low estimation of Gerrald’s moral character.76 The significance of Thelwall’s relationship with Coleridge and Wordsworth has been the subject of much recent debate.77 It lies beyond the scope of this chapter and of this book, but any account of Thelwall among the poets needs to engage with the complexity of his earlier situation in the LCS. As an orator and writer in the 1790s, Thelwall did not simply act in the name of ‘the people’, but wrestled with difficult issues of how to create and address a ‘public’ for a democratic culture. Not the least among the issues facing the beleaguered and diverse experiments with democracy undertaken by Thelwall and his colleagues in the radical societies was how to define ‘literature’ in relation to their aspiration for a culture of reading and debate that would play an active part in defining who ‘the people’ were.