From the First Wine to the First French Wine

When you sit with a glutton, eat when his greed has passed.

When you drink with a drunkard, take when his heart is content.

(Prisse papyrus, instructions to Kagemni fol.1, 18–21 (c. 2600 bce))

Our Paleolithic ancestors almost certainly complemented their diet with naturally-fermented fruits, including over-mature wild grapes, and possibly enjoyed the buzz that followed (Dudley Reference Dudley2014). After all, even monkeys do this and partial fermentation occurs spontaneously. But wine has been defined (Estreicher Reference Estreicher, Brodersen, Erskine and Hollander2019) as the result of the intentional fermentation of vitis vinifera grapes. ‘Intentional’ suggests a container such as a clay jar in which the fermentation can take place as well as cultivation, which guarantees a sufficient supply of grapes and grape juice to fill one or more jars. This definition of wine brings us to Neolithic times when clay jars first appeared and cultivation began. This led to the domestication of oats, rye, barley, lentils, peas, and of course v. vinifera.

The archaeological, ampelographic, genetic, and linguistic evidence of the origin of wine and viticulture points toward eastern Anatolia and Transcaucasia (Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia). The wild eastern v. vinifera sylvestris is native to this region (McGovern et al. Reference McGovern, Fleming and Katz2000; McGovern Reference McGovern2003; Myles et al. Reference Myles, Boyko, Owens, Brown, Grassi, Aradhya, Prins, Reynolds, Chia, Ware, Bustamante and Buckler2011; Estreicher Reference Estreicher2017). This dioecious grape was domesticated and evolved into the hermaphrodite v. vinifera. When viticulture was brought to Western Europe (mostly by the Phoenicians), the domesticated eastern v. vinifera vinifera probably crossed with the wild western v. vinifera sylvestris to produce many of Europe’s cultivars, which are distinct from those in Anatolia and Transcaucasia (from here on, v. vinifera will stand for v. vinifera vinifera).

The oldest pips of domesticated v. vinifera, dated c. 6000 bce, were found (McGovern Reference McGovern2003) in Anatolia (Çayönü), Georgia (Shulaveris-Gora), and Azerbaijan (Shomu-Tepe). The oldest proof (McGovern et al., Reference McGovern, Jalabadze, Batiuk, Callahan, Smith, Hall, Kvavadze, Maghradze, Rusishvili, Bouby, Failla, Cola, Mariani, Boaretto, Bacilieri, This, Wales and Lordkipanidze2017) of wine comes from the chemical analysis of the residue in a Georgian jar, also dated c. 6000 bce. The oldest evidence of wine-making in Europe, dated c. 4300 bce, was uncovered at Dikili Tash (Garnier and Valamoti Reference Garnier and Valamoti2016) in Macedonia. The oldest wine-making setup (Barnard et al. Reference Barnard, Dooley, Areshian, Gasparyan and Faull2011), Areni-1 in Armenia, was dated c. 4100 bce. Thus, wine substantially pre-dates the earliest citiesFootnote a as well as writing.

By the fourth millennium bce, wine and viticulture had spread throughout the Near East and Egypt (McGovern et al. Reference McGovern, Mirzoian and Hall2009). After 800 bce, the Phoenicians brought viticulture to Mediterranean islands, North Africa (e.g. Carthage), and southern Spain (e.g. Cádiz). The Etruscans (Tuscany, Umbria, Lazio) traded with the Phoenicians and produced (Brun Reference Brun2004) wine since at least the early eighth century bce. The Etruscans exported wine to southern Gaul in the late seventh century, including to Marseille in the first half of the sixth century. Etruscans amphorae found (Py Reference Py1993) throughout the region are the earliest evidence of wine in Gaul.

The founding story of France’s oldest city involves the daughter of king Nanus of the Segobrigii tribe. She chose a trader from the Greek settlement of Phocaea (western Anatolia) as her husband (Omrani Reference Omrani2017). He accepted and the couple founded Massilia (Marseilles) c. 600 bce. In 545 bce, the inhabitants of Phocaea were threatened by Cyrus the Great and fled. Some of them went to Massilia. This was the second, larger, wave of Greek settlers in Southern Gaul. Marseilles grew and established its own colonies in the region, such as Nikaia (Nice) and Antipolis (Antibes).

Around 590 bce (about the same time Massilia was founded), the Bituriges from central Gaul migrated (Rabanis Reference Rabanis1835) to Aquitania and established a settlement on the banks of the Garonne: Burdegala. It became the Roman Burdigala, today’s Bordeaux. But there is no proof of viticulture in that region until the first century ce (see below).

Since the Phocaeans already knew about viticulture for centuries, it is not surprising that Marseilles got involved in the wine trade. The heavy Etruscan amphora was soon replaced by the lighter Massaliote one (Py Reference Py1993; Olmer Reference Olmer2009). By the late sixth century, Massaliotes amphorae were widespread (Brun Reference Brun2004). Some were found in the tombs of wealthy Celts in northern Italy (Lomas Reference Lomas2018), suggesting that quality wine was produced in Massilia. In the fifth and fourth centuries, virtually all the amphorae in southern Gaul were Massaliote (McGovern et al. Reference McGovern, Fleming and Katz2000). Every indication is that wine was very popular and in big demand. Few remains of wine presses (Brun Reference Brun2004) dating back to these early days exist, most likely because any wooden levers and support beams have long since disappeared.

The Greeks occasionally traded with Celtic tribes as far as northern Gaul. The best-known example is the krater of Vix (Bioul Reference Bioul2002), the largest one ever found. It was discovered in the tomb of a princess or priestess buried c. 490 bce near Châtillon-sur-Seine, some 240 km south-east of Paris. A krater is a wine-mixing vase: it was partly filled with water before wine was added, and then everybody dipped their cup in the same mixture. The krater of Vix is 1.6 m high and 1.2 m wide. It has elaborate handles and its neck is carved with horses and Spartan-looking soldiers. Etruscan wine-serving jars and locally-made wine cups were also found in the tomb. The krater was probably manufactured in Taranto (a Spartan colony in southern Italy), transported to Vix in pieces, and then reassembled. There is no evidence that it was ever used or that any wine was produced in the region until Roman times. But Vix was an important trading centre, including tin from Cornwall. The coincidence of the burial date with that of the battle of Marathon suggests that the Greeks needed tin to make bronze for weapons and shields, in expectation of the next Persian invasion.

The oldest archaeological proof of wine-making in Gaul was found in Lattes (McGovern et al. Reference McGovern, Luley, Rovira, Mirzoian, Callahan, Smith, Hall, Davidson and Henkin2013), near Marseille. It is dated 425 bce. Archaeological excavations have produced a small wine press, vine pips and twigs, as well as local amphorae which had contained wine. Some of the amphorae were sealed with corks, a technique used by the Etruscans.Footnote b Few would be surprised if wine had been produced in Marseilles somewhat earlier, but the proof could be buried anywhere under the city. There is archaeological evidence of vineyards (Brun Reference Brun2004) near the ancient city. Thus, the earliest wine in today’s France was produced some 5500 years after wine was first made in Transcaucasia.

In the fourth century bce, Gallic tribes were established in Gaul and in the northern part of the Italian peninsula. The Romans referred to these regions as Gallia Transalpina and Cisalpina, respectively. These tribes frequently fought each other or formed fluid alliances. The Celtic tribes had cultural and linguistic links, but no centralized structure or leadership. Wine was a sought-after luxury, and viticulture quickly became the most important cash crop. The next major evolution in the history of wine in Gaul involves the Romans.

Roman Gaul

Young adults should take [wine] in moderation. But elderly persons may take as much as they can tolerate.

(Abū-ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn-ʿAbdallāh Ibn-Sīnā a.k.a. Avicenna (970–1037), Canon 814)

Since the eighth century bce, wine was produced (Brun Reference Brun2004; Dodd Reference Dodd2020) in the Greek colonies in the south of Italy and in Etruria. As several of the Kings of Rome were Etruscans, viticulture appeared early on around the city. Since the mid-eighth century bce, Rome had been expanding by absorbing its neighbours (Lomas Reference Lomas2018; Southern Reference Southern2014). The Romans did not win all the battles they fought, but they stubbornly came back after a loss and, in the end, managed to impose their will. Rome grew.

Around 390 bce, Rome faced an aggressive tribe of marauding Gauls led by Brennus and suffered a humiliating defeat at the river Allia, near Rome. Brennus sacked Rome for several days before returning north. Only the better-defended Capitoline Hill was preserved. This attack on Rome was the start of a long-lasting resentment of the Gauls. There were many subsequent battles between the Romans and Gallic tribes in Italy. The turning point was the (second) battle of Lake Vadimo in 283 bce, a decisive Roman victory. Yet, G. Cisalpina would not be fully pacified and become a Roman province for another two centuries.

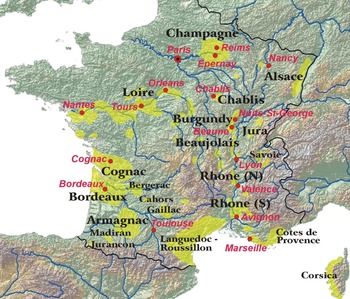

Wine production in southern Gaul was insufficient to satisfy the local demand. In the second century bce, the wine trade with Rome grew, with annual imports (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2008) reaching 10 million litres. One trade route (Lebecq Reference Lebecq, Webster and Brown1997) started in Marseilles (or Arles), then went north along the Rhône and the Saône up to Chalon-sur-Saône. The other started in Narbonne, then went along what would become the via Aquitania toward Toulouse and Bordeaux (Figure 1). Much of the wine was decanted from amphorae into barrels in Toulouse and Châlon-sur-Saône, respectively, for transport into Celtic Gaul. A few amphorae contained expensive wines, but most held cheap, mass-produced wine.

Figure 1. Two routes involved decanting wines from amphorae into barrels at Toulouse or Châlon-sur-Saône for transportation into Celtic Gaul. The trade routes themselves would soon be covered with vines.

The wine trade with Gaul was highly profitable to Rome. According to Diodorus Siculus (90–30 bce) (Diodorus Siculus): ‘The Gauls are exceedingly addicted to wine… drinking it unmixed and… without moderation… When they are drunk, they fall into a stupor or a state of madness… The traders… receive a slave for a jar of wine, getting a servant in return for a drink.’ The annual wine trade with Gaul reached two million gallons (Lebecq Reference Lebecq, Webster and Brown1997) and brought to Rome up to 15,000 slaves (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2008; Fleming Reference Fleming2001).

Wine being so desirable, theft by local tribes occurred with increasing frequency. This is one reason why the Roman Senate reacted favourably when Marseilles (a Roman ally during the second Punic war) requested assistance (Omrani Reference Omrani2017; Southern Reference Southern2014; Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2008) against the Saluvii, a tribe centred at Aix-en-Provence. Beyond protecting its wine trade and helping an ally, Rome also wished to secure a land route to Spain.

In 125 bce, Rome sent two legions north of the Alps. They defeated the Saluvii, and Aix-en-Provence became a Roman fort. Saluvii survivors sought refuge with the Allobroges (east of the Rhône) and the Arverni (west of the Rhône). The war expanded. These tribes were finally defeated by consul Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus. By 121 bce, Rome controlled southern Gaul from the western tip of the Alps to the eastern half of the Pyrenees, as well as a wide strip of land on both sides of the Rhône up to Geneva. Marseilles remained independent. Ahenobarbus ordered the construction of the via Domitia, a road connecting Italy to Spain. This territory became the Province of G. Transalpina in 81 bce, with its capital in Narbonne. It became Provincia in the days of Caesar (hence ‘Provence’) and G. Narbonensis in the days of Augustus.

Within a year of the establishment of Narbonne in 118 bce, the region was already planted (Dion Reference Dion2010) with olive trees and vines. In Rome, Cicero arguedFootnote c that the production of olives and wine by non-Romans created unwanted competition: the profits had to remain Roman! Within a few decades, Rome had monopolized the wine (and olive oil) production: only Roman citizens could be allowed to grow vines and make wine.

In 113 bce, the Germanic Cimbri and Teutones tribes migrated south-west across Gaul in search of loot and a better life. They were numerous, wild, and feared. Rome became concerned not just about looting but also about the possibility that these tribes might end up moving into Italy. Marius, first elected consul in 107, was sent to Gaul to stop them (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2008). He trained his legions to take on a much larger but disorganized force. He also introduced small fighting units, the cohorts.Footnote d Marius was unable to prevent the two tribes from entering Italy, but he convincingly defeated them there, despite being heavily outnumbered. The next major player in Gaul would be his nephew, Julius Caesar.

There were three ethnic and linguistic groups in Gaul, and no mention of viticulture by any of them. The largest group consisted of the Galli, a generic name for some 50 tribes. The territory of the Belgae (north-east of Paris up to the Rhine) included maybe two dozen Germanic tribes. Finally, there was Aquitania (from the Garonne and the Atlantic to the western half of the Pyrenees). In addition to Aquitani, this territory included groups of Vascones, a generic name for the Basque tribes, and probably people from further south in Spain (Collins Reference Collins1986).

Caesar’s invasion of Gaul started when the Helvetii migrated from Switzerland across Gaul. In 58 bce, he defeated them at Bibracte (Mont Beuvray) after a battle that lasted into the night. Then, he marched north to prevent the (Germanic) Suebi from crossing the Rhine into Gaul. And then, he took on one tribe at a time, killing, looting, and selling entire populations into slavery. By 53 bce, Caesar had conquered pretty much all of Gaul. In 52 bce, several Gallic tribes united under VercingetorixFootnote e (Jones Reference Jones2006), but he was defeated at Alesia (south of Clermont Ferrand).

Caesar left much of the surviving command structure in place with local chiefs in charge as long as they governed on behalf of Rome. Small rebellions were crushed, but Gaul was Roman and would remain so for nearly 500 years. Caesar left Gaul and crossed the Rubicon, starting a civil war in Rome. He ultimately became a dictator for life (in his case, just a few more years).

Marseilles, independent while Caesar was in Gaul, sided with Pompei during the civil war. Caesar took the city and confiscated all its territories. He also settled many veterans of his army throughout southern Gaul and along the Rhône (Omrani Reference Omrani2017; Salles Reference Salles2001). The Senate allowed them to plant vineyards and produce wine. Some of today’s Côtes-du-Rhône vineyards were planted during this period.

Gaul was divided into four provinces: G. Narbonensis, G. Lugdunensis, G. Belgica, and G. Aquitania. Roads and cities were built, education was introduced. Latin gradually replaced Celtic and a Gallo-Roman culture evolved. Over time, Gauls could achieve Roman citizenship and move up social ranks: Gnaeus Julius Agricola (ce 40–93), the general responsible for the Roman conquest of Britain, was born in Fréjus; Claudius and Caracalla were born in Lyons; the poet and teacher Decimius Ausonius (310–395), tutor of Gratian, prefect of Gaul, and consul in 379, was born and died in Bordeaux. He owned land in Naujac.

During the reign of Augustus, there was an active search for cultivars able to withstand the winters in central and northern Gaul. Wine growers crossed or grafted Roman vines with native wild species (Dion Reference Dion2010; Lachiver Reference Lachiver1988; Phillips Reference Phillips2016). The Allobroges produced a cross, the Allobrogica, a red grape that was widely planted in northern Côtes du Rhône. In the region of Bordeaux, the Biturica (or Balisca) thrived. This grape has been proposed to be an ancestor of the sauvignon family of grapes. This is quite plausible but not certain. A study (Myles et al. Reference Myles, Boyko, Owens, Brown, Grassi, Aradhya, Prins, Reynolds, Chia, Ware, Bustamante and Buckler2011) of some 1000 cultivars illustrates the complexity of establishing the ancestry of vines. For example, the central-European Traminer is a direct parent of the Pinot Noir (Burgundy), Verdelho (Madeira), Sauvignon Blanc (Bordeaux and other regions), and many others. Yet, there is no Traminer in Burgundy, Madeira, or Bordeaux. How and when the modern version of these grapes appeared is unclear. Establishing direct links between today’s and ancient cultivars is always speculative.

In ce 70, Pliny the Elder wrote (Pliny) that viticulture had spread to the territory of the Allobroges (Auvergne, Franche-Conté). There is archaeological evidence of Roman wine estates dating back to that time. The villa of St. Bézard (Mauné et al. Reference Mauné, Durand, Carrato and Bourgaut2010) was established in the first century and continued production until the fifth. It had vineyards, wine-presses, and amphora-manufacturing facilities. In the north, the remains of a first or second century Roman vineyard was found near Gevrey-Chambertin (Garcia et al. Reference Garcia, Chevrier, Dufraisse, Foucher and Steinmann2010). The vines had been planted with a geometrical distribution and characteristics precisely matching Pliny the Elder’s instructions: a large hole to plant the main trunk and a smaller hole next to it for a clone (provinage). It is the oldest proof of viticulture in Burgundy. The Roman villa ‘Mas des Tourelles’ (Omrani Reference Omrani2017) is located south-west of Avignon. A later proof of wine making in that region comes from the account of the visit of Constantine to Augustodunum in 312. Roman villas have also been found in the Graves region of Bordeaux (Podensac, Preignac, and Barsac).

Under Nero, more wine was shipped from Gaul to Italy than the other way around (Fleming Reference Fleming2001; Dion Reference Dion2010; Lachiver Reference Lachiver1988; Phillips Reference Phillips2016). The ce 79 eruption of the Vesuvius buried Pompeii and Herculaneum. It also destroyed vineyards and large stocks of wine, resulting in wine shortages. Imports of wine increased while fields that had been used for grain were planted with vines. Within a few years, this caused a wine surplus and a shortage of grain. Domitian’s ce 92 edict banned the planting of new vines and ordered half the vineyards in the provinces to be uprooted. The order was often ignored, and the uprooted vineyards were the worst and least productive ones. But most vineyards in Champagne were uprooted (Simon Reference Simon1906).

Few new vineyards were planted in Gaul for almost two centuries except in Bordeaux (from where wine was shipped to Roman troops in England and northern Gaul) and along the critical south-north corridor (Moselle, Autun, Trèves). The main wine regions were the Mediterranean coast, the Rhône valley, Bordeaux, parts of Burgundy, and the Rhine. There were vineyards along the Moselle, but large-scale viticulture in Alsace and Champagne started later (Dion Reference Dion2010).

Roman interest in the Bordeaux region started during the reign of Augustus. Until then, the region was a wine-trading centre but no wine was produced: it was either imported via Marseilles or Narbonne and transported overland to Toulouse, or shipped from GaillacFootnote f on the Tarn and the Garonne. Strabo (c. 63 bce–ce 24) reported to Augustus that there were no vines along the Tarn toward the Garonne into Burdigala. Yet, he wrote about the vineyards along the Rhône. But in ce 71, Pliny the Elder (ce 23–79) described vineyards near Bordeaux. Thus, it is likely that the earliest vineyards in Bordeaux and Cahors were planted mid-first century (Dion Reference Dion2010).

During the third century, wooden barrels replaced amphorae throughout Gaul (Twede Reference Twede2005). The barrel was likely a Celtic invention which the Romans adopted for the overland transport of wine and other goods. In his Natural History, Pliny wrote (Pliny): ‘In the vicinity of the Alps, they put their wines in wooden vessels hooped around […] In more temperate climates, they place their wines in dolia, which they bury in the earth.’

Around ce 100, Christianity arrived in Marseilles and gradually reached all of Gaul. As wine was required for mass, Christianity contributed to the expansion of viticulture wherever it established itself. There was a Christian community in Reims in the mid-third century and a bishop of Bordeaux attended the council of Arles in 314. The persecution of Christians started after the fire of Rome in 64, which Nero blamed on them, and peaked under Diocletian. But by the fourth century, Christianity had become the official religion of the empireFootnote g (Kulikowski Reference Kulikowski2016).

Domitian’s restrictions on new vineyards survived until 280, when Probus allowed all free men in Gaul to own vineyards and make wine. This boosted the economy in regions that had to import wine until then. A substantial expansion of vineyards occurred. Gibbon (Reference Gibbon1993) writes that Probus ‘exercised his legions in covering with rich vineyards the hills of Gaul’. Vines were planted in and around Paris. Julian, wintering in Paris in 358, noted (Gibbon Reference Gibbon1993) that ‘with some precautions […] the vine and fig tree were successfully cultivated’.

But Rome’s slow and inexorable decline was well under way. The huge empire required considerable resources. The army, stretched over vast distances, was involved in frequent wars. The men had to be paid, equipped, and fed. The government in Rome was hungry for resources. The heavily taxed provinces were expected to produce the needed goods (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2008). The system could be sustained as long as the economy was sound, the population healthy, and the birth rate high enough to satisfy the needs of the army, agriculture, and manufacture. The Romans also hoped that the Barbarians east of the Rhine and north of the Danube would be kind enough to remain there, or at least not to cross the border too frequently.

This structure was vulnerable. Eventually, everything went wrong. In order to increase the money supply, some emperors debased the currency. The percentage of silver in denarii dropped (Cunliffe Reference Cunliffe2008) from 97% (in 50) to 4% (in 270). By then, nobody used such coins anymore, and even taxes had to be paid in kind. It took considerable effort to re-instate a credible Roman coinage. And then, the population collapsed. This was due in small part to low birth rates and in large part to the Antonine plague (166–180) and the plague of Cyprian (249–262), both of which caused some 5 million deaths. The population of the Empire did not recover.

Starting around 250, barbarians penetrated the empire with increasing frequency. They were confederations of small Germanic tribes such as the Alemanni (Lebecq Reference Lebecq, Webster and Brown1997) (‘all people’), Vandals (‘wandal’ means wanderer, Jones Reference Jones2006), and Franks (not yet united). The first incursions were looting expeditions but, a few decades later, the barbarians returned with families and domestic animals looking for places to settle. In 274–275, the Franks and Alemanni overrun most of Gaul. Probus spent years fighting them, to the point that he called himself ‘Germanicus Maximus’. In response to the barbarian raids, many towns in Gaul built defensive walls. Bordeaux enclosed 34 hectares on the south side of the city (Cleary Reference Cleary, Brodersen, Erskine and Hollander2019).

Probus was the first to settle Germanic tribes in selected regions of the Empire in exchange for service with the Roman army. In 297, the Franks were allowed to settle in the territory of the Batavians (north-west of The Netherlands). Julian also settled Frankish tribes in exchange for military service. By the end of the fourth century, more than half the officers in the Roman army were of barbarian origin, some in senior positions (Pohl Reference Pohl, Webster and Brown1997): the half-Vandal Stilicho was general under Honorius; the Frank Merobaudes was consul twice and served as Master of the Infantry in the West from 375 to 388; the Suevi Ricimer ruled parts of the Western Empire from 461 to 472. Many of the tribes that had settled in the Western Roman Empire converted to Christianity, but often with Arian beliefs. They would eventually convert to Catholicism. Franks, Burgundians, Alamanni, Visigoths, and others all knew about wine and enjoyed it. They did not destroy vineyards and wine-making hardware, but often protected them (Phillips Reference Phillips2002, Reference Phillips2016).

After sacking Rome in 410, the Visigoths were settled in south-western Gaul (418), in return for military service. Their capital was Toulouse. They quickly conquered much of Southern Gaul, and later the Iberian Peninsula. Flavius Aëtius, a senior officer under Valentinian III, settled the Burgundians near Lyons in 443, again in return for military service. The Champagne region remained under Roman control for another 35 years but, by then, the western Roman empire was gone: its last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, had been deposed in 476. The population of the city of Rome had dropped by about three-quarters from its peak of about 1 million under Augustus. It further dropped to maybe 50,000 by the end of the sixth century (these numbers are estimates).

Martinus (c. 316–397), a Roman cavalry officer and the future St. Martin (patron saint of winemakers) must be mentioned here. He became famous for slicing his red cloak (Latin: capa) and giving half of it to a beggar in Amiens. The legend says that Jesus visited him the following night to give him his full capa back. A red capa, believed to be his, became a precious relic. Almost five centuries later, it was cared for by Charlemagne’s clerks of the Chapel (Riché Reference Riché1978). Hugues Capet (Charlemagne’s maternal grandson and founder of the Capetian dynasty) could have been named after this capa. After the beggar incident, Martin left the army and, around 360, became a hermit near Poitiers. He soon ruled a small community of hermits, which became the first ‘monastery’ in Gaul. In 372, the people of Tours asked him to become their (third) bishop. He is credited with many accomplishments, such as domesticating the wild grape in Touraine or planting the first Vouvray vineyard. His donkey is even said to have shown local winegrowers how to prune vines. Some of these stories may be true, but who knows which ones?

From the Fall of Rome to the Turn of the first Millennium

The church is near, but the road is icy. The bar is far, but we can walk carefully.

(Old Russian proverb)

In late fifth-century Gaul, there was no central state, law, or order. There were no large cities and the infrastructure was not maintained. International trade and the large-scale production of wine had stopped. Gregory of Tours (1974) mentions wines from ‘Gaza, Ahkelon, and Laodicea’, but these were rare. From Toulouse, the Visigoths controlled southern Gaul, including Aquitaine. The centre-west was occupied by the Burgundians, based in Lyon and Geneva. The north was controlled by the Franks (James Reference James1988), still a collection of semi-independent tribes at the time. Their territory extended from Belgium west to the edge of Brittany and north of the Loire. As usual, Brittany remained very independent. The Alemanni were in control east of the Rhine. For a long time, people’s priority was simply survival.

Merovingian Kings

The Salian Frank domination of Gaul began with Clovis (r. 481–511), grandson of Merovech (hence ‘Merovingian’). He defeated the Roman Syagrius at Soisson (486), moved against the Burgundians and married Clotilde (493), the Catholic daughter of the Burgundian Chilperic. Then, Clovis defeated the Alemanni and converted (probably from Arianism) to Catholicism. His baptism in Reims by bishop Remigius (later, St. Rémi) in December 496 marked the beginning of the intimate link between the Church and Merovingian (and later Carolingian) kings. The wealth and authority of the Church increased rapidly following Clovis’ conversion. He is said to have become royally drunk (Vizetelli Reference Vizetelli1882) on wines from vineyards planted by Remigius outside the city walls. Remigius possessed the earliest documented (Nouvion Reference Nouvion2018) vineyards in Champagne.

With Burgundian support, Clovis moved against the Visigoths in southern Gaul. In 507, he defeated them decisively at Vouillé (near Poitiers). Alaric II was killed during the battle, allegedly by Clovis himself. The Franks went on to plunder Toulouse and then took Bordeaux. Within a few years, the Visigoths permanently left Gaul for Spain. Clovis was the first Frankish king to try to establish a foothold in northern Spain. When that failed, he consolidated his power in Gaul. He accomplished this by killing those of his relatives who might have preferred to remain independent. Clovis eventually established himself in Paris, which remained the capital of Gaul (and then France) except during the reign of Charlemagne. By the end of his reign, Clovis had unified Gaul. His territory included most of France, Belgium, parts of the Netherlands, a wide track of western Germany, and Switzerland. But Burgundy, Brittany, Aquitaine, and the Mediterranean coast of France maintained some degree of independence.

Trouble started after Clovis’ death in 511. For the Franks, the kingdom was not the Roman res publica (‘public thing’) but the personal property of the king. Clotilde insisted that each of Clovis’ four sons got his part. This gave rise to four kingdoms: Austrasia (‘East Land’, German speaking, Ripuarian law) with major cities Reims and Metz; Neustria (‘New Land’, later ‘Francia’, Latin speaking, Salic law), with Paris and Soisson; Aquitania, with Toulouse, Bordeaux, and Poitiers; and Burgundy, with Lyon and Geneva. Divisions of kingdoms among all the male sons of a king became the Frankish norm. This worked as long as each son could conquer new (non-Frankish) territory to secure the wealth he needed to remain in power and give land to each of his sons upon his death. Clovis’ sons tried to conquer new land in Spain and Italy, without success. So they turned on each other (James Reference James1988).

Thus, the death of a Frankish king with more than one son was often followed by a civil war, as each son wanted supremacy over his brothers. Kingdoms were subdivided, occasionally merged, while those parts that were used to being more or less independent increasingly resisted subordination to one or the other king. The details are complicated (James Reference James1988) and poorly documented. There were 30 Merovingian kings, most of them in the ‘forgettable’ category. Clothar II briefly re-united the kingdom in 613. His son Dagobert was the last powerful Merovingian king. Following his death in 639, there was a succession of young kings who required a regent for guidance. Some of them died before being able to consolidate power. Since their own children or heirs were very young themselves, executive power permanently shifted from the king to the mayors of the palace, a title comparable to that of prime minister today. This title became hereditary and new kings could not even pick their own mayor. They no longer engaged in the extensive travel required to confirm their authority throughout their lands, resulting in greater local independence. The later Merovingian kings have been labelled rois fénéants (do-nothing kings). In truth, there was not much they could do.

In 732, the Austrasian mayor Charles Martel defeated a Muslim expeditionary force (moving north from Spain) between Poitiers and Tours. The battle established Charles as the de-facto ruler of the kingdom even though the Arabs maintained a strong presence in Southern Gaul for several more decades (Chebel Reference Chebel2011). Interestingly, the Spanish ‘Chronicle of 754’ refers to Martel’s army as consisting of ‘Europenses’, possibly the first use of this name. The battle of Poitiers revived the interest of the Franks in the now quasi-independent Aquitaine. Martel imposed his authority in the region, but died in 741. His son Pepin (later, ‘the short’) became mayor. In 751, Pepin asked Pope Zachary to recognize that the actual power was in the hands of the mayor and depose the last Merovingian, Childeric III. Zachary agreed and Pepin became the first Carolingian king. The same year, in Italy, the Lombards took Ravenna.

Kingdom, Monasticism, and Wine

Throughout the Merovingian period, Gaul experienced near-continuous warfare at one location or another. The population was mostly rural. Society was divided into laboratores (those who work, the overwhelming majority), with a few percent oratores (those who pray) and bellatores (those who fight: the nobility). The limited wine trade involved shipping on rivers. The roads, mostly the old Roman ones, were not maintained and brigandage was common. Travel was dangerous, especially while transporting saleable wares. The production of most goods, including wine, was intended for the local market. Wines, essential everyday food (Garrier Reference Garrier1995), were poured unfiltered into barrels within hours of being pressed. They contained some fruit matter and residual sugars. Such wines were low in alcohol (below 10%), more nutritious than they are today, but also more unstable. They turned sour within months: a one-year-old wine was probably undrinkable.

The Frankish kings used their own income to pay for the needs of their army. The soldiers themselves were not paid but were guaranteed basic supplies and a share of the loot. Some commanders received land (Pohl Reference Pohl, Webster and Brown1997). This resulted in an armed and landed aristocracy. Small landowners and peasants had to pay all sorts of taxes and fees to use the mill or wine press that belonged to the local lord, bishop, or abbot. There were tolls on services as well as bridges – including for navigating under them. Landowners also had to pay the tithe to the local bishop or abbot. The bishops, usually Gallo-Romans appointed by the king, were the local spiritual and temporal leaders. They collected taxes on behalf of the king and played the role of judges. The law was the local custom. The bishops also organized health care, provided hospitality, and sometimes ordered the construction or repair of defensive walls. If there was a count nearby, he and the bishop would split these tasks among themselves. The dukes, usually Franks, were military commanders in charge of a large territory.

Neither Clovis nor his Merovingian successors were crowned by a pope or bishop: they did not owe their crown to the Church. Instead, the king appointed bishops and abbots, and used the institutions of the Church for political purposes. In return, the bishops and abbots received protection, privileges, and donations of land, including vineyards. Thus, bishops and monasteries accumulated vineyards and wealth. In Bordeaux, the archbishop and the establishments associated with the Church were the principal owners of vineyards. They needed wine for communion which, until the thirteenth century, involved both bread and wine. They were also expected to take care of visitors, travellers, and the sick. All this involved large quantities of wine.

The Paris region was covered with vineyards, many of which were owned by the Abbeys of St. Germain-des-Prés (south of Paris) and St. Denis (north and within Paris, including the hill of Montmartre). The king owned vineyards on the ‘Ⓘle de la Cité’, but these disappeared in the mid-twelfth century as the city grew. Since the days of Dagobert, St. Denis had a famous fair on October 9, on time to sell the new wine. In the twelfth century, the nearby port-city of Rouen on the Seine became one of the largest wine-trading port in Western Europe.

Monasticism (Melville Reference Melville2016) began in the third century, as hermits in Egypt and Syria started to attract followers. This was a life of isolation, contemplation, and self-sacrifice. The early monastic communities in Gaul such as the one founded by St. Martin de Tours near Poitiers involved eremitical life. A rule for monastic communities by Augustine of Hippo (354–430) focused on chastity, poverty, obedience, and detachment from the world.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, monasticism provided some security. Food was available and someone would take care of you if you were sick. New monasteries emerged, including institutions for women, such as the Abbey of the Holy Cross founded by Queen Redegund (c. 520–587). A monastic revolution (Melville Reference Melville2016; Seward Reference Seward1979) began with Benedict of Nursia (c. 480–547) who led the monastery of Monte Cassino. Benedict’s Rule organized every aspect of monastic life based on chastity, poverty and obedience, with equal time for prayer, work and rest. The concept of working monks was new. Agricultural work included viticulture, as wine was required for Mass. Indeed, since 397, canon law forbade the use of apples or other fruits as substitutes for fermented grape juice: … nec amplius in sacrificiis offeratur quam de uvis et frumentis (Concilium Carthaginienses III, can. 24). After his death, Benedict and his Rule briefly faded from memory and Monte Cassino was destroyed by the Lombards in 577. Benedict and his accomplishments were revived by Gregory the Great (590–604). The Rule of St. Benedict was adopted by many monasteries in the seventh century.

The Rule (chapter 40) allowed moderate drinking (Seward Reference Seward1979): the daily ration was a hemina of wine. This is about half a pint, roughly the volume associated with the Roman hemina. The second-in-command at a Benedictine monastery was the cellarer described as ‘wise, of mature character, sober, not a great eater, not haughty, not excitable, not offensive, not slow, not wasteful, but a God-fearing man who may be like a father to the whole community’. He was in charge the ‘cellar’ – not a wine cellar but the colder location where food reserves were kept, including the wine barrels. During one of his expeditions in Italy, Charlemagne visited the (rebuilt) monastery of Monte Cassino and obtained a copy of the Rule. He and his son Louis tried to enforce strict adherence to it by all monasteries, with only partial success.

In Merovingian and Carolingian times, abbeys or monasteries (Melville Reference Melville2016; Seward Reference Seward1979) were established by the king or the nobility. Land and vineyards were given in exchange for prayers to facilitate whatever pesky negotiations with St. Peter might be required when the donor reached the Pearly Gates. The appointed Abbot would often be a close relative to the donor, without involvement from the pope or local bishop. The ‘royal’ monasteries received rich agricultural lands (with serfs attached to it) and benefited from the direct protection of the king. In exchange, they were expected to provide lodging and feed the king with his (usually huge) retinue when he was travelling. They also had to provide military support, often led by the local bishop or abbot in full armour. Monasteries also served as prisons. The king could get rid of an annoying competitor by forcibly shaving his head and locking him up in some distant monastery, never to be heard of again.

Among many examples of donations (Seward Reference Seward1979), Gontran of Burgundy gave land and vineyards in Dijon to the Abbey of St. Benignus in 587; Duke Amalgaire of Lower Burgundy founded the Abbey of St. Pierre and St. Paul in Bèze with vineyards at Gevrey, Vosne, and Beaune in 629; the Royal monastery of Lorsch, founded in 764 by Pepin the Short, received land and vineyards all over South Germany. These were not just vineyards and agricultural land, but also houses, woodlands, pastures, watermills, serfs, and entire villages. Monasteries sometimes paid the tithe to their bishop, but no other taxes, and often enjoyed free navigation. ‘Franche nef’ was first granted to St. Mesmin, a monastery endowed by Clovis. In 799, Charlemagne granted (Simon Reference Simon1906) free shipping in Rouen to the abbey of St.-Germain-des-Prés.

Small landowners were at a substantial disadvantage. They had to pay the tithe (the best 10% of the crop before harvest) and were the last in line to rent the wine press. They were not allowed to sell their wine until their lord’s wine was sold out. Transporting wines to a market involved fees and tolls. The vineyards owned by the nobility, bishops, or monasteries had no such issues. They had the best grapes and pressed them first. Their wines were better and often had good reputations.

Carolingian Kings, Vikings, and the Division of Europe

In November 753, Stephen II crossed the Alps to anoint Pepin (the Short) in St. Denis and request his help against the Lombards who threatened Rome. For the first time, the pope crowned a Frankish king, thus establishing the superiority of the Church over monarchs. In 755–756, Pepin led his army into Italy and defeated the Lombards. In Rome, he was presented with a forged document, the ‘donation of Constantine’ (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlin1993), which he approved (Charlemagne later confirmed it). It is not clear if Pepin knew how to read, much less recognize a fake, but his approval gave birth to the Papal States. The pope became a secular leader with a large tax base.

Pepin fully exerted his authority and strengthened his hold on power. He invaded Aquitaine in 763 and destroyed many vineyards. He did it again in 766, after which he received oaths of loyalty and hostages. Pepin died in 768, and his kingdom was divided between his two sons: Carloman and Charles (later, Charlemagne). Carloman conveniently died in 771 and Charlemagne (Riché Reference Riché1978; Chamberlain Reference Chamberlin1986) became the sole ruler. He would extend the Frankish kingdom into an empire.

Charlemagne went to war almost every spring. His soldiers were not paid: once in enemy territory, looting was profitable. If resistance was encountered, the soldiers would not hesitate to kill. Parts of Aquitaine, Brittany, and Saxony needed decades to recover from the destruction. Almost every year from 772 to 802, Charlemagne fought the Saxons and other pagan tribes east of the Rhine, finally conquering and forcefully Christianizing Germany all the way to the Elbe.

In 773–774, Charlemagne conquered the Lombards. In 778, he moved into Spain (without much success) where he suffered his only major defeat when his rearguard was massacred by the Basques at the Roncesvalles pass. His son Louis would ultimately conquer Barcelona from the Muslims in 801. In the east, Charlemagne defeated the Avars in 796 and returned to his capital Aachen with an enormous booty. In Rome, on Christmas Day 800, he was crowned Emperor by Leo III. By the end of his reign, Charlemagne’s empire included Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Switzerland, Austria, Northern Italy, and a part of northern Spain.

In the late eighth century, Rome had an estimated 20,000 inhabitants, but Paris only about 4,000. About 90% of the population of Gaul was rural. Just as in Merovingian days, the towns were ruled by a bishop appointed by Charlemagne. He also appointed abbots, usually among people close to him. His biographer, Einhard, became the head of six monasteries, which guaranteed him a substantial personal income. Monasteries and bishoprics played important roles as representatives of the king and repositories for food and wine. There was a constant fear of lack of supplies. Floods, droughts, or plagues were common, resulting in famines such as those in 793, 805, and 807. Monks provided medical care and refuge for travellers: the roads were not safe from brigands. Merchants carrying grain, salt, iron, and wine by water on the Seine, Loire, Rhine, and smaller rivers were charged numerous tolls along the way.

Charlemagne reformed the monasteries and tried to enforce the Rule of St. Benedict. He donated much land and vineyards to monasteries. The royal abbey of St. Ricarius in north-eastern France, founded by St. Ricarius in the seventh century, grew considerably when Angilbert, Charlemagne’s son-in-law, became its Abbot. Most famously, Charlemagne gave part of the hill of Corton to the Abbey of Saulieu in 775. The wine produced there became the famed Corton-Charlemagne. In 814, the Benedictine abbey of St. Germain des Prés near Paris owned (Dion Reference Dion2010; Phillips Reference Phillips2016; Seward Reference Seward1979) some 20,000 ha of land with 300 to 400 ha under vines, most of which was leased to tenants. St. Germain des Ores possessed over 30,000 ha; St. Bertin over 10,000; Fulda over 15,000.

Charlemagne encouraged wine production and drunk moderate amount of wine himself during meals, sometimes even sharing his goblet following the Frankish tradition (Dion Reference Dion2010; Riché Reference Riché1978). But he did not approve of excessive drinking in his presence. Yet, most people at the time drank heavily, including abbots and bishops. Theodulf, poet and bishop of Orleans, pointed out: ‘A bishop who keeps his gullet full of wine should not be permitted to forbid it to others. He ought not to preach sobriety who is drunk himself’ (Riché Reference Riché1978). Wine taverns could be found in many locations, sometimes within monasteries, some of which also had their own brewery. ‘Without a doubt, this was an age obsessed with wine’ (Riché Reference Riché1978). The wine accessible to the common people was probably not very good, but it was a safe drink (Garrier Reference Garrier1995). It was nutritious and an integral part of people’s diet. Wine was also used as a cure for all sorts of ailments. But the wine trade remained local, limited to towns accessible by rivers. Viticulture was the most important cash crop but was the privilege of the wealthy. Bishops, abbots, and princes all had carefully tended vineyards. Tenants did the work. They would typically be paid with half the harvest but had to pay taxes on it.

Charlemagne outlived all of his sons but one, Louis. In 813, Charlemagne crowned him co-emperor in Reims, the city where Clovis was baptized. The city would become the regular site of coronation of French kings. The banquets always included generous volumes of local wine. Thus, early on, the wines from Champagne were associated with royalty. Of course, in the days of Charlemagne, they did not resemble today’s sparkling champagne. The wines were praised, but we do not know what they were compared with.

By the late eighth century, the Viking (Chamberlain Reference Chamberlin1986; Ferguson Reference Ferguson2010) threat appeared. They attacked the monastery of Lindisfarne (Northumberland) in 793. They sacked the monastery of Iona (west coast of Scotland) in 795, 802, 806 and 807, after which the monastery was abandoned. In Carolingian territory, the Vikings attacked the monastery of Noirmoutier (on an island off of Nantes) in 799. Monasteries – wealthy and poorly defended – were obvious and easy targets. Gradually, the Vikings expanded their reach by navigating up rivers, stealing horses when needed, and attacking small towns, then cities. They wanted silver and slaves, but gladly took barrels of wine and other goods as well. Charlemagne was getting old and did not organize a major resistance against this threat. Viking raids continued almost every spring and summer, with increasing frequency. In the 830s and 840s, they established short-term winter settlements instead of returning home. In 841, the city of Rouen was sacked and the monastery of Jumièges burnt.

Charlemagne died in 814. Louis I (the Pious) tried to maintain the Empire, but he was no Charlemagne. He had three children by his first wife: Lothar, Pepin, and Louis (later: the Germanic). Hoping to avoid future inheritance fights, he declared early on how his Empire would be divided after his death: Lothar would get the Emperor title and the bulk of the land, Pepin and Louis would get Aquitaine and Bavaria, respectively. Only Lothar liked this division. The tension among the brothers came to a boil when Louis the Pious re-married and had a fourth son, Charles (later: the Bald). Charles’ territory now had to be carved out of lands already promised to his other three sons. When Pepin died in 838, Louis the Pious decided to give Aquitaine to Charles. But Pepin’s own son expected this inheritance for himself. The civil war exploded at Louis’ death in 840, while the Vikings were sacking many parts of the country.

After two years of war, Charles and Louis swore loyalty to each other in Strasbourg (842). The fighting ended with the Treaty of Verdun the following year. The Empire was divided into three parts: Charles the Bald took the west (later: France); Louis the Germanic the east (later: Germany); the imperial title and a thick slice of land between France and Germany went to Lothar. It extended from the Netherlands to Provence and about half of Italy. Dion (Reference Dion2010) claimed that Louis the German specified his ownership of some parcels of land on the west side of the Rhine propter vini copiam (for the culture of the vine), but no copy of the treaty of Verdun has survived.

This is the period when a community of Benedictine nuns was established at Château Chalon in the Jura (Lorch Reference Lorch2014). It was conceded to the Church in Besançon by Lothaire II in 869. At its prime, would-be novices had to demonstrate 16 degrees of nobility to be admitted. Since the early days of the abbey, the nuns produced wine. They are often credited for producing the first ‘vin jaune’ for which this region is so famous. However, it is not known if, when, or how these nuns created it. The community was permanently dissolved after the French Revolution (some ruins are still visible in the village).

In the meantime, the Vikings pillaged Nantes (843), attacked Toulouse (844), sacked Paris (845), and St. Germain des Prés (861). They repeatedly attacked Aquitaine, and Bordeaux was virtually abandoned mid-ninth century. Orléans was pillaged in 868. Charles the Bald could not respond fast enough to the multiple Viking raids in different locations. He asked his counts and dukes to maintain military forces and build fortresses against the Vikings. The counts and dukes then kept local taxes and tolls to cover the costs. By the late tenth century, they had become independent, had their own army and castles, considered their title to be hereditary, and appointed abbots and bishops themselves. The king had lost much of his power as well as most of his land and tax base.

In 845, Charles the Bald paid the Vikings a ransom of 7000 pounds of silver to lift the siege of Paris by drawing from Church treasures as much as fortune has bestowed upon them. The Vikings left. When Louis the Stammerer became king, the Vikings returned. In 885, they again besieged Paris which was heroically defended by Odo of Paris. When Charles the Fat came to the rescue, he did not fight the Vikings as expected but offered them another ransom instead. He was forced to abdicate in 888 and died the following year. Odo (an ancestor of the Capetian) was acclaimed king. After the Siege of Chartres in 911, his successor Charles III (the Simple, a Carolingian) offered to a group of Vikings the land between the mouth of the Seine and Rouen. In exchange, their leader Rollo agreed to end the brigandage, swear allegiance to the king, convert to Catholicism, and defend the Seine from further Viking raiders. Rollo became Count Roland and his land became Normandy (later, a duchy).

The Viking raids stopped in the 930s. By then, many monasteries had been abandoned after being sacked or destroyed, and the rights of ownership transferred back to the nobility. The old Merovingian and Carolingian monasteries, tools of the king or emperor, no longer existed. The first sign of an independent monasticism appeared in 863: Girard de Vienne founded a monastery on his land under the pope’s authority. The abbot was to be elected by the monks rather than appointed by him or the king. This was new. And then, in 910, William the Pious (duke of Aquitaine) installed monks on his land at Cluny in southern Burgundy and placed this abbey under the authority of the apostles Peter and Paul: it answered directly to the Pope. The last Carolingian of Francia, Louis V, died in 987. The Capetian dynasty took over as Hughes Capet (987–996) was crowned in Reims.

From the Year 1000 to the Renaissance

A barrel of wine can work more miracles than a church full of saints.

(Old Italian proverb)

By the year 1000, the climate had improved and would stay so for three centuries, a period referred to as the medieval warm epoch. The growing seasons became longer and catastrophic weather events less frequent. Better crops meant greater availability of food. The population grew. Market towns became cities. An increasingly wealthy merchant middle-class emerged, thirsty for higher-quality wines. Forests were cut, watermills and windmills constructed. Gothic cathedrals were built. New vineyards were planted near cities (close to markets) and along rivers (for easy access to markets). Large-scale viticulture was developed in Alsace. Universities were created in Bologna, Paris, Oxford, Cambridge, and other cities. The first crusade (1096–1099) established the kingdom of Jerusalem, but later crusades failed to preserve it. They had little impact on the history of wine except for donations of vineyards to monasteries by departing crusaders in exchange for much-needed prayers. Banking and credit became available. Marco Polo visited China. Dante Alighieri wrote the Divine Comedy.

The early Capetian kings had the support of the Church but little else: they only controlled the Ⓘle-de-France region around Paris, a very small tax base indeed. Dukes and counts often had more land and power than their king, in particular those of Aquitaine, Burgundy, and Normandy. William of Normandy (the Bastard, and then the Conqueror) invaded England in 1066 and became its king. Members of another Norman family, the Hauteville conquered Apulia, Calabria, and Sicily, and Roger II was crowned king of Sicily.

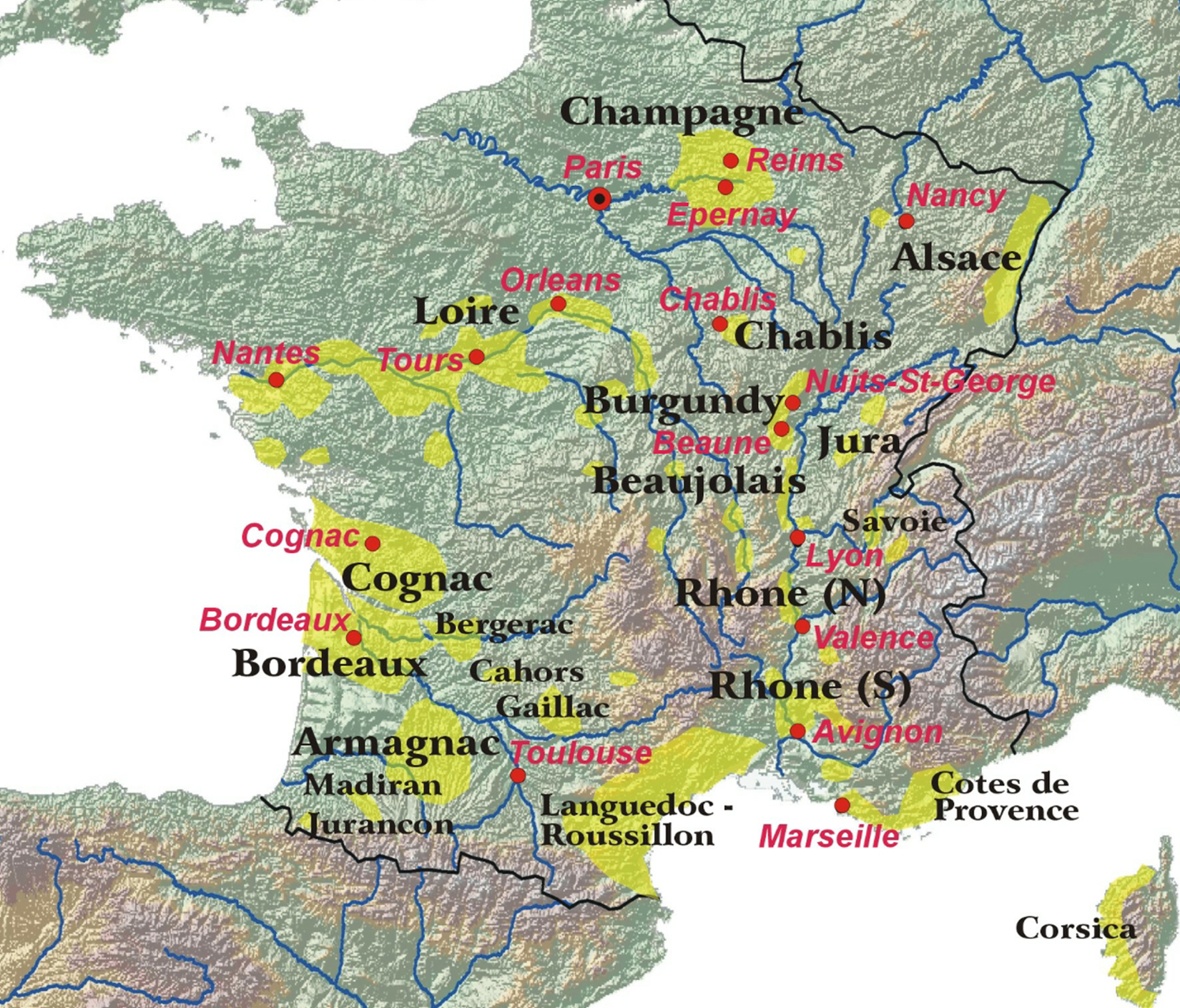

The Capetian kings gradually re-conquered French land from the English. The south was absorbed following the Albigensian Crusade. The concept of France emerged. Cistercian abbeys acquired many prestigious vineyards, especially in Burgundy. The papacy moved from Rome to Avignon. Clement V and then John XXII expanded the vineyards nearby. The Châteauneuf-du-Pape wine has been famous ever since. The centre of the all-important wine trade with England moved from Rouen to La Rochelle, and then to Bordeaux. By 1300, the populations of Paris, Rouen, and Bordeaux were about 200,000, 50,000, and 40,000, respectively, as compared with 45,000 for Rome.

The calamitous (Tuchman Reference Tuchman1978) fourteenth century began with the onset of the Little Ice Age (Behringer Reference Behringer2015). During the medieval warm epoch, the cereal crops were good-weather plants: wheat, barley, oats, and rye have tall stems and a heavy top. Strong rains and winds break the stems, leaving the cereals to rot on the ground. The Baltic sea froze in 1303–1304 and 1306–1307; the Venice lagoon froze in 1311 and 1323 (it would freeze 30 times until 1800); the vintage in Bordeaux was miserable in 1315; there was a vintage failure throughout France in 1316; 1322 was the coldest winter in memory. A famine of biblical proportions hit Western Europe from 1315 to 1322. And then, the Hundred-Years’ War caused misery in France, especially during the periods of peace, as ‘companies’ of unemployed soldiers pillaged the country. The Black Death (Benedictow Reference Benedictow2006) arrived in 1347. Within a couple of years, it killed more than a third of the population. The plague returned in 1361, and then again in 1369, 1373–1374, 1388–1390… albeit with smaller death rates.

Following the Black Death, the population of France dropped from ∼16 million in 1340 to ∼11 million in 1400. This resulted in wage increases as the demand for labour vastly exceeded the supply. Vineyard workers paid 8d (deniers) par day in 1345 received up to 20d in 1350 and 30d later that century. Urgent or difficult work could be paid as much as double that amount (Autrand Reference Autrand2001).

Many areas previously under cultivation (including vineyards) were now used to raise farm animals. Cultivation continued only in the most appropriate locations. In the 1400s, because of increased yields associated with better soils and the availability of manure, the cost of basic food items dropped. For a while, the general population had more available income and consumed greater amounts of expensive foods such as meat and higher-quality wine. By the 1500s, the populationFootnote h of France had rebounded to 16 million or so. It reached about 20 million in 1700 and 28 million by the Revolution of 1789.

In the mid-1400s, the Renaissance had begun in Florence under the Medici. It would spread throughout Europe and profoundly change the way people view the world. The availability of paper combined with Gutenberg’s invention of movable type allowed the rapid propagation of new ideas. The Ottoman Turks took Constantinople (1453), marking the end of the Eastern Roman Empire. Granada fell to Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabelle of Castille (1492), marking the end of Islamic Spain. Later that year, Columbus sailed to the New World, marking the beginning of new European wealth, viticulture in the New World, but also mass African slavery. Medieval Europe was history.

Eleanor and English rule in Bordeaux

At the age of 15, Eleanor (Seward Reference Seward1978; Markale Reference Markale1979) inherited the duchy of Aquitaine from her father, William X. Aquitaine was much larger than it is today, extending from the Loire to the Pyreneans. Eleanor’s guardian, Louis VI (the Fat) married her to his son Louis, and then promptly died. Thus, in 1137, Louis VII began his reign with a young, beautiful wife and a much-enlarged kingdom. But Eleanor, known for her feistiness, did not get along with Louis: she complained about having married a monk. In 1145, she travelled with him on his ill-fated crusade, where Louis justified one of his nicknames: the Incompetent. In March 1152, the marriage of Eleanor and Louis was dissolved on grounds of consanguinity. Two months later, she married Henry Plantagenet who would become Henry II, king of England, in 1154. All of a sudden, the territory of the French king had considerably shrunk while the English crown controlled the north and west of France: Henry II was count of Anjou, Touraine, and Maine, duke of Normandy and Aquitaine – all wine-producing regions. As for Louis VII, the best he ever did was to re-marry and father Philip II (Augustus), who would recover much of that territory.

Eleanor and Henry spend their first year together in Aquitaine (Gradis Reference Gradis1888). They ultimately had five daughters and four sons, two of whom would become kings: Richard I (Lionheart) and John (Softsword, a lesser nickname). Henry’s sons rebelled against him about power sharing. Eleanor supported them and ended up confined in various castles for 16 years. By then, France was led by Philip Augustus. Henry died in 1189 and Richard I released his mother from custody. Eleanor governed the Plantagenet empire while he was on crusade and then held for ransom. She later returned to Aquitaine where she died in 1204.

Richard I made Bordeaux the base of his French operations. He issued an ordinance that included severe punishments for the theft of a cluster of grapes: 5s (sous) (a substantial fine) or one ear (a painful loss). This suggests that stealing grapes was a significant problem at the time, and also that viticulture was a business worthy of special protection.

Few Bordeaux wines were exported to England at that time. Most French wines found in England came from Rouen (‘French’ meant produced in the Ⓘle-de-France, along the Seine, and the Marne) while Rhine wines came from Cologne. These wines were sold at the same price: £2 5s per tun (∼900-liter barrel). Light red and white wines from Anjou were shipped on the Loire and made their way to England as well as Paris. These wines were popular (Dion Reference Dion2010; Simon Reference Simon1906; Lavaud Reference Lavaud2010; Higounet et al. Reference Higounet, Etienne and Renouard1973) with Eleanor, Henry, and Richard. Yet, all of them did spend time in Bordeaux and knew its wines. After Richard’s death in 1199, the throne of England was taken by John. He imposed a maximum price on wines sold in England. His edict (Dion Reference Dion2010) listed Poitou, Anjou, as well as ‘French’ wines, but not the wines from Bordeaux or Gascony.

After Philip Augustus confiscated Normandy, Maine, Anjou, Touraine, and Poitou, John wasted considerable resources fighting back, without success. The battle of Bouvines (1214), a resounding victory of Philip over John and the Holy Roman Emperor Otto IV, secured the Capetian gains. England was left with just Aquitaine and Gascony. Rouen, until then the most important wine-shipping port to England, lost its tax privileges. The centre of the English wine trade moved to La Rochelle.

Having raised taxes and then exhausted the treasury while losing most of his father’s possessions in France, John was forced to put his seal on the Magna Carta in 1215. That same year, he ordered 120 tuns of Bordeaux wine for his personal use. That was probably the first large-scale order of Bordeaux wine. But John had little time left to enjoy them. In addition to a strong rebellion by the English nobility, he had to fight a French invasion led by Prince Louis. Few lamented his death in 1216.

In twelfth-century Bordeaux, the majority of the vineyards and the wine production were centred on the city itself. The vineyards covered just a small portion of today’s Graves.Footnote i Most of them were owned by the Church (especially the archbishop of Bordeaux) and a few wealthy families. The actual work was done by tenants under contract: they kept up to two-thirds of the harvest for their efforts but had pay the tithe on their share, often in wine. The grapes were sold to winemakers who dealt with coopers and merchants. In the end, most people in Bordeaux were directly or indirectly involved in the wine trade. A wealthy bourgeois middle-class emerged. These bourgeois were exempt from some taxes and enjoyed free navigation on the Garonne. Over time, they acquired nearby land and planted their own vineyards, in particular in the swampy but fertile ‘palus’ along the banks of the Garonne. These were drained and planted with vines.

A wine policy, the ‘police des vins’, was established: the wines produced in the ‘haut-pays’ (in practice, any vineyards not owned by the bourgeois or the diocese of Bordeaux) were not allowed within city limits before St. Martin’s day, November 11. After 1373, this date was pushed back to Christmas (Lavaud Reference Lavaud2010; Higounet et al. Reference Higounet, Etienne and Renouard1973). Thus, only local wines were sold in the fall following the harvest. The production from farther away could not reach the market until spring. This policy was ignored when the local harvest was insufficient to satisfy the demand. The ‘haut pays’ wines arriving in the fall were stored in warehouses along the river, outside the city: les Chartrons.

Three taxes (Trabut-Cussac Reference Trabut-Cussac1972) were levied per tun of wine: Grande Coutume (an export tax), Issac, and Petite Coutume. The first two were determined after each harvest: in 1302, 7s 6d for the Grande Coutume and 3s 9d for the Issac. They went up to 16s and 8s, respectively in 1304, but then dropped in 1305. In 1203, John exempted Bordeaux, Bayonne, and Dax from the Grande Coutume. The following year, La Rochelle was also granted this exemption. The Petite Coutume, fixed at 2d1o (obole), applied to wines from the ‘haut pays’: In addition to transport and storage costs, these wines were also charged more taxes. Not surprisingly, only 12 to 20% of the land was under vines in Barsac, Preignac, Sauternes, and other regions (Lavaud Reference Lavaud2010). This was enough for the local needs but not for commercial quantities of wine. Virtually none of Médoc was under vines.

In 1224, Louis VIII took La Rochelle, Saintonge, Limousin, Périgord, and part of the Bordelais. But Bordeaux resisted and the French army did not cross the Gironde. Since the wines from La Rochelle and Anjou were now French in the eyes of the English king, they could not reach the English market or were taxed at a very high rate. This is when Bordeaux became the most important wine-shipping port to England.

Philip IV (the Fair) took control of Bordeaux from 1294 to 1303. Following the Auld Alliance (1295), the wine merchants from Scotland, a French ally, were granted privileges. When Aquitaine returned to English rule, Bordeaux enjoyed a golden age in terms of wine trade with England. Edward II ordered 1000 tuns of Bordeaux wines for his coronation in 1307.

In 1308–1309, some 100,000 tuns of wine were shipped (Harris and Pépin Reference Harris and Pépin2015) to England, three-quarters of which came from Bordeaux. The wines were shipped to London, Bristol, Cork (Ireland), and Hull (Yorkshire). Bordeaux also shipped to the Baltic region, Spain, and Portugal (Phillips Reference Phillips2016). But only about 10,000 tuns were produced by the city’s bourgeois. The rest came from a growing list of towns such as Barsac, Langon, St. Macaire, Cahors, Moissac, Montauban, Dax, and Bayonne. The wines from the north bank of the Garonne (Bergerac, Fronsac, Saint Emilion, etc.) were shipped from Libourne, which exported some 11,000 tuns to London that year. The entire region was engulfed in the wine trade.

A dynastic dispute precipitated the Hundred-Years’ War (1337–1453). The last Capetian, Charles IV, died without a heir in 1328. Philip of Valois (a nephew of Philip IV) and Edward III (a grandson of Philip IV through his mother) claimed the throne. Edward had the stronger claim but with a fatal flaw: he was English. The French nobility argued that the throne cannot be inherited through a woman and chose Philip (VI, the Fortunate). He confiscated Aquitaine in 1337 and the war began. Thanks to a better military organization and technology (the longbow), England prevailed at the battle of Crécy (1346). In 1355–1356, the dreaded ‘chevauchées’ of the Black Prince (Edward’s eldest son, prince of Wales and Aquitaine) devastated the south-west of France: towns, granaries, mills, barns, and haystacks were burned, wine vats smashed, vines and fruit trees cut, bridges destroyed, women and children abused. He won the battle of Poitiers (1356) where he captured John II (the Good). The resulting treaty of Brétigny (1360) saw John II renounce his rights to Aquitaine and Edward III his rights to the crown of France.

Edward’s successor, Henry V, crushed a superior French force at Azincourt (1415) thanks again to the longbow and the lack of unified leadership on the French side. Tensions between the Bourguignons and Armagnacs escalated and Burgundy allied itself with England. The treaty of Troyes (1420) promised the crown of France to the son of Henry V: France almost became English. It took a young woman, Joan of Arc, to turn things around. In 1429, she relieved the siege of Orléans, won at Patay, and brought Charles VII to Reims to be formally crowned, reversing the treaty of Troy. Joan was then captured by the Burgundians, sold to the English, and burnt at the stake (1431).

Charles VII re-organized the French administration, established a formal system of taxation and a permanent army under the king’s control. He used canons (for the first time) to defeat the English at Formigny (1450) and Castillon (1453), ending the Hundred-Years’ War. England permanently lost its possessions in France, except for Calais (until 1558). Bordeaux lost its tax advantages with England, starting a long period of sluggish sales. England would soon be devastated by internal conflicts (the Wars of the Roses). The people of Aquitaine and Gascony, used to considerable independence since Clovis, found themselves under the authority of the king of France. The wine trade continued but on a much reduced scale. The next boost for Bordeaux wines came decades later and involved the Dutch.

The Cistercian Revolution and Burgundy

In the ninth and tenth centuries, many monasteries were sacked, destroyed, or abandoned (Melville Reference Melville2016). They later rebounded but, at the turn of the Millennium, monasteries had become quite different from what they were under the Merovingians and Carolingians. They were no longer an arm of the monarchy, funded by the crown and led by appointees of the king. Instead, they were under the supervision of local bishops and their abbots were often chosen by the monks themselves.

For some 500 years, almost all the monasteries had been Benedictines. But in the late eleventh century, the Carthusian (1086) and Cistercian (1098) orders were created, and then the military orders (Hospitallers and Templars) followed by friars (Franciscans and Dominicans). In the twelfth century, the Cistercians dominated the monastic landscape. As far as French wine is concerned, they played the most important role, especially in Burgundy and Champagne.

Their adventure began when some monks in the wealthy abbey of Molesme (Burgundy) decided on a more austere religious experience, away from comfort. They moved about 100 km south and, in 1098, established the abbey of Cîteaux (Williams Reference Williams1998, Leroux-Dhuys and Gaud Reference Leroux-Dhuys and Gaud1998). The name comes from ‘cistelle’, a reed common to the area. The habit of the new order was made of undyed wool, hence ‘white monks’. The monks spent about eight hours a day working, the rest was prayer and rest. They hired poor lay brothers to help with (and later do all) the hard work: construction, agriculture, and pastoralism (Leroux-Dhuys and Gaud Reference Leroux-Dhuys and Gaud1998). Their third abbot, Stephen Harding, finalized the constitution of the new order, based on a strict interpretation of the Rule of St. Benedict. In 1119, the charter was approved by Calixtus II, officially establishing the Order of Cîteaux: the Cistercians.

As their number increased, groups of at least 13 (in reference to Christ and his 12 disciples) would leave, find a new location, and start a daughter abbey: the first were La Ferté (1113), Pontigny (1114), Morimond (1115), and Clairvaux (1115). They generated more daughter abbeys. Each abbey was autonomous, financially independent, and had its own abbot, but was annually supervised by its mother abbey. The first abbot of Clairvaux, the very ascetic Bernard (later, St. Bernard), had enormous influence with kings and popes.

This was a time of strong religious feelings and the Cistercian model attracted many. New daughter-abbeys were built in or near Burgundy and then further out, from Portugal to Russia, from Sicily to Scotland. There were 322 abbeys by 1150, 531 by 1200, 651 by 1250, and 697 by 1300. Concurrently, 158 Cistercian nunneries were founded. This phenomenal growth slowed down with the onset of the Little Ice Age and stopped with the Black Death.

The Cistercians rarely cleared new land but acquired properties that were already cultivated (Hoffman Berman Reference Hoffman Berman1992). They enjoyed papal privileges such as immunity from local episcopal jurisdiction and exemptions from ecclesiastic tithes. They negotiated with local authorities permissions to travel and move goods toll-free. At a time when salt was a heavily-taxed royal monopoly, they received grants of salt, which is essential for preserving foods and in the diet of animals. Most abbeys had plenty of them: in 1316, Poblet (Catalonia) had 40 horses, 111 cattle, 2,215 sheep, 1,500 goats, 172 pigs… Their manure made fields very productive. The Cistercians acquired mills and wine presses. In 1143, Longpont received a wine press and 100 casks for their wine.

On the other hand, peasants had to pay tithes to the Church, which decided (just before harvest) which ten percent of the crop it wanted. The lord (who could be an abbot or bishop) had the droit de ban: the right to declare the earliest date for the grape harvest. This often was just after his own vineyards would be harvested. The peasants then had to pay a fee to use their lord’s wine press but they were the last in line to access it, therefore producing late and often oxidized wines. They were not allowed to sell any wine until their lord had sold his own. And then they were charged tolls to transport it. Competing with the Cistercians was daunting.

Many peasants and small landowners found it preferable to donate their land to an abbey and continue to work on it in exchange for guaranteed food and protection. Non-affiliated monasteries and hermitages also joined Cistercian abbeys, sometimes simply to benefit from their tax exemptions. The Cistercian holdings kept growing and growing. By the late thirteenth century, they had profitable ‘granges’. These were large agricultural units with buildings but no church. Clairvaux had eight granges, Morimond 15, Fontfroide over 20… The spectacular Clos de Vougeot itself was a grange.

The abbeys also received gifts of land and vineyards. The monks of the Abbey of Pontigny were the first to plant Chardonnay in Burgundy. In 1098, Cîteaux received part of the Meursault vineyard from the duke of Burgundy. Its monks also created the famous Clos de Vougeot. The Cistercians acquired vineyards at Meusault (e.g. Perrières), Beaune (e.g. Cent Vignes), etc. The Cistercian nuns (‘Bernardines’) of Notre-Dame de Tart made wine at Bonne-Mares (originally bonnes mères), Clos de Tart, Chambolle-Musigny, and so on.

By the mid-fourteenth century, the Cistercians owned hundreds of hectares of vineyards in Beaune, Pommard, Nuits, Corton, etc. In the late twelfth century, they were selling wine in bulk and shipping it on rivers using their own barges. By the mid-thirteenth century, wine was openly retailed in monastic precincts, even though no monk was directly involved in the financial transactions. The Cistercians became amazingly wealthy.

The biggest impact of the Cistercians was in Burgundy and Champagne, but they were also present (Seward Reference Seward1979) in Bordeaux (e.g. Château La Tour Ségur). In 1309, Grandselve (near Figeac) shipped 300 tuns of its wine down the Garonne for sale in Bordeaux. The Cistercians were present along the Loire (Clos de la Poussie is one example) and the Rhône (vineyards in Vacqueyras and Gigondas). They were also active in Switzerland, Germany, Italy, Spain, Portugal and other countries. Cistercian abbeys even produced wine in the north of Poland (Williams Reference Williams1998) albeit just enough for their own needs.

The Cistercians were not alone. By 1275, the Benedictines of Cluny owned all the vineyards around Gevrey, including the famous Clos de Bèze. Cluny became the biggest landowner in Burgundy. From 1232 to 1246, the wife of Odo II (Duke of Burgundy), donated several vineyards to the priory of Saint-Vivant (dependent of Cluny). This donation added up to a little more than 6 ha of the current Romanée St-Vivant. The priory also received the ‘Cloux (clos) des Cinq Journaux’, now Romanée-Conti. ‘Journaux’ (old French for journées) referred to the area one worker could till or prune in one day (in this case, Cinq Journaux was an area that required five man-days of work). The Carthusians had connections to wine throughout France, especially in Cahors and Châteauneuf-du-Pape. The famous Quai des Chartrons in Bordeaux, where much wine was stored, is named after a Carthusian charterhouse founded in 1383. The Templars had vineyards in Bordeaux (such as Clos les Templiers in Saint Émilion or Château de l’Eglise in Pomerol), along the Loire (Clos des Templiers), and in Champagne. The Carmelites of Beaune owned La Vigne de l’Enfant Jésus. The list goes on. Seward (Reference Seward1979) lists over 100 wine appellations of monastic origin in France.

The progress achieved by various monks in the art of viticulture and vinification has been poorly recorded (Williams Reference Williams1998, Hoffman Berman Reference Hoffman Bermann.d.), if at all. The Cistercians are often credited with establishing the concept of terroir, Footnote j possibly because Citeaux’s Clos-de-Vougeot was the first large vineyard to be surrounded by a stone enclosure (‘clos’) in 1212. Its grapes were probably vinified separately, producing a wine characteristic of this specific vineyard. But there is no Cistercian document discussing the concept of terroir. The Cistercians returned the marc (leftover in the wine press) to the vineyard as a fertilizer, but they were not the only ones doing it (Seward Reference Seward1979). They built vaulted cellars to store their wine barrels. These may well have been the first wine cellars. They learned to compensate for evaporation by topping off the wine in the barrels (ullage). But who first realized the importance of ullage is also not known.

The dominant red grape in Burgundy was the ‘Noirien’, also called ‘Morillon’ or ‘Auvergnat’. It became (Phillips Reference Phillips2016) Pinot Noir after 1395. The reason for the name-change is unclear, but ‘pinot’ refers to the shape of the clusters, which is reminiscent of a pine cone (Dion Reference Dion2010) (pomme de pin).