1 Introduction

Double emulsions are droplets with one other droplet inside. Their core–shell structure has attracted wide attention in various fields (Vladisavljević, Nuumani & Nabavi Reference Vladisavljević, Nuumani and Nabavi2017). In pharmaceuticals, one common technique is to use double emulsion for drug encapsulation of highly hydrophilic molecules. It solves the low encapsulation efficiency problem faced in single emulsion techniques due to the quick partitioning of the hydrophilic molecules into the external aqueous phase (Iqbal et al. Reference Iqbal, Zafar, Fessi and Elaissari2015). Double emulsions are also suitable containers for performing chemical and biochemical reactions under well-defined conditions. Compared to bulk reactions, the greatly reduced volume needed in double emulsion techniques is beneficial for high throughput screening assays (Chang et al. Reference Chang, Swank, Keiser, Maerkl and Amstad2018). Furthermore, double emulsions can be used as templates for the synthesis of more complex colloidosomes (Lee & Weitz Reference Lee and Weitz2008; Azarmanesh, Farhadi & Azizian Reference Azarmanesh, Farhadi and Azizian2016), as well as for controlled release of the inner contents (Datta et al. Reference Datta, Abbaspourrad, Amstad, Fan, Kim, Romanowsky, Shum, Sun, Utada and Windbergs2014). To ensure the successful applications of double emulsions, one of the key issues is to provide precise control over the double emulsion structure, size and monodispersity at a sufficient production rate (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wang, Xie, Ju, Liu, Jiang, Chen and Chu2016; Shang, Cheng & Zhao Reference Shang, Cheng and Zhao2017).

Traditional double emulsion fabrication methods, such as the bulk emulsification and the membrane emulsification methods (Vladisavljević et al. Reference Vladisavljević, Nuumani and Nabavi2017), are attractive to many industries (e.g. food and cosmetic) where scalability for large production is important (Varka et al. Reference Varka, Tsatsaroni, Xristoforidou and Darda2012). However, these techniques have poor size and monodispersity control (Silva, Rodríguez-Abreu & Vilanova Reference Silva, Rodríguez-Abreu and Vilanova2016), which makes them inadequate for applications requiring high precision, such as in medical, pharmaceutical and material industries. The emergence of microfluidic technology (Utada et al. Reference Utada, Lorenceau, Link, Kaplan, Stone and Weitz2005; Whitesides Reference Whitesides2006) opens up a new horizon. It provides more detailed control over the operating conditions (Vladisavljević et al. Reference Vladisavljević, Nuumani and Nabavi2017) and offers great flexibility in designing multilayer (Abate & Weitz Reference Abate and Weitz2009) or multicore emulsions (Nisisako, Okushima & Torii Reference Nisisako, Okushima and Torii2005; Nabavi, Vladisavljević & Manović Reference Nabavi, Vladisavljević and Manović2017b). So far, the microfluidic devices for producing double emulsions can be roughly classified into a series of two T-junctions (Okushima et al. Reference Okushima, Nisisako, Torii and Higuchi2004), two flow-focusing junctions (Seo et al. Reference Seo, Paquet, Nie, Xu and Kumacheva2007; Pannacci et al. Reference Pannacci, Bruus, Bartolo, Etchart, Lockhart, Hennequin, Willaime and Tabeling2008; Abate, Thiele & Weitz Reference Abate, Thiele and Weitz2011), coaxial capillaries (Utada et al. Reference Utada, Lorenceau, Link, Kaplan, Stone and Weitz2005; Nabavi et al. Reference Nabavi, Vladisavljević and Manović2017b) and the possible combinations and variations of the aforementioned geometries (Nisisako & Hatsuzawa Reference Nisisako and Hatsuzawa2016; Zhu & Wang Reference Zhu and Wang2016).

The understanding of double emulsion formation dynamics are crucial for microfluidic control and equipment optimization. Double emulsions are commonly generated either in a two-step or one-step formation regime, depending on whether the inner part of the double emulsion is sheared simultaneously with the middle layer in the outer fluid (Utada et al. Reference Utada, Lorenceau, Link, Kaplan, Stone and Weitz2005). Due to the distinct flow details in the two-step and one-step formation regimes, the influence of flow conditions, fluid properties and geometrical parameters on each regime should be analysed respectively. For the two-step formation regime, Okushima et al. (Reference Okushima, Nisisako, Torii and Higuchi2004) have systematically showed the effect of flow rates on the double emulsion sizes and the number of internal droplet for multicore emulsions when they are formed using a series of T-junctions. The one-step formation regime is mostly encountered in coaxial microcapillary devices. Experimental studies have been carried out on the effect of flow rates (Lee & Weitz Reference Lee and Weitz2008; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Kim, Kim, Han and Weitz2013) and geometrical settings (Nabavi et al. Reference Nabavi, Vladisavljević, Bandulasena, Arjmandi-Tash and Manović2017a). Scaling laws have also been developed for the emulsion size predictions (Utada et al. Reference Utada, Lorenceau, Link, Kaplan, Stone and Weitz2005; Chang et al. Reference Chang, Serra, Bouquey, Prat and Hadziioannou2009).

Complementary to experiments, numerical studies on double emulsion formation dynamics in microfluidic channels have also garnered strong interest. For instance, great efforts were made to elucidate the effects of flow rates, interfacial tension ratios, geometry (Chen, Wu & Lin Reference Chen, Wu and Lin2015; Nabavi et al. Reference Nabavi, Vladisavljević, Gu and Ekanem2015b) and viscosities (Fu et al. Reference Fu, Zhao, Bai, Jin and Cheng2016) on the double emulsion properties and the flow regime predictions (Nabavi et al. Reference Nabavi, Vladisavljević, Bandulasena, Arjmandi-Tash and Manović2017a) for coaxial flow-focusing capillary devices. Simulations are particularly advantageous for providing accurate flow details and for allowing each relevant parameter in the system to be varied systematically. In the literature, a number of ternary fluid models have been successfully developed and applied in the study of multiple emulsion formation behaviours, including using the volume of fluid method (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wu and Lin2015; Nabavi et al. Reference Nabavi, Vladisavljević, Gu and Ekanem2015b, Reference Nabavi, Vladisavljević, Bandulasena, Arjmandi-Tash and Manović2017a; Azarmanesh et al. Reference Azarmanesh, Farhadi and Azizian2016), the front-tracking method (Vu et al. Reference Vu, Homma, Tryggvason, Wells and Takakura2013), the free energy finite element method (Park & Anderson Reference Park and Anderson2012) and the lattice Boltzmann method (Fu et al. Reference Fu, Zhao, Bai, Jin and Cheng2016, Reference Fu, Bai, Bi, Zhao, Jin and Cheng2017).

In this work, our focus is on the planar flow-focusing cross-junctions. They are promising for integration with other devices and they can be parallelized to raise the production rate of the emulsion droplets, while still ensuring good size control (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Choi, Shim, Frijns and Kim2016). Furthermore, in contrast to other microfluidic geometries, systematic parametric study is rarely reported on planar flow-focusing devices. Several works, such as Abate et al. (Reference Abate, Thiele and Weitz2011) and Azarmanesh et al. (Reference Azarmanesh, Farhadi and Azizian2016), briefly discussed the possible conversion between the two-step and one-step formation regimes and the variation of shell thickness. However, it remains unclear in which flow rate regions monodisperse double emulsions are produced, and correspondingly, how the droplet sizes can be varied in those regions. It is likely that the droplet sizes have different dependencies on the flow rates for the two-step and one-step formation processes. There are also open questions on the role of channel geometry in the formation regime conversion, and on the effects of interfacial tension ratio in determining the morphologies of the emulsion droplets, including the possibility of complete, partial and non-engulfing shapes (Pannacci et al. Reference Pannacci, Bruus, Bartolo, Etchart, Lockhart, Hennequin, Willaime and Tabeling2008; Nisisako & Hatsuzawa Reference Nisisako and Hatsuzawa2010; Guzowski et al. Reference Guzowski, Korczyk, Jakiela and Garstecki2012; Chao, Mak & Shum Reference Chao, Mak and Shum2016).

We have chosen to use the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM). The lattice Boltzmann method is highly favourable for the study of emulsion formation behaviours due to its simplicity in solving interface dynamics, including droplet breakups and coalescences, as well as its ability to deal with complex geometries, and its high efficiency in parallel computation (Krüger et al. Reference Krüger, Kusumaatmaja, Kuzmin, Shardt, Silva and Viggen2017). So far, three types of ternary lattice Boltzmann models have been developed, including the free-energy model (Liang, Shi & Chai Reference Liang, Shi and Chai2016; Semprebon, Krüger & Kusumaatmaja Reference Semprebon, Krüger and Kusumaatmaja2016; Abadi, Fakhari & Rahimian Reference Abadi, Fakhari and Rahimian2018; Wöhrwag et al. Reference Wöhrwag, Semprebon, Moqaddam, Karlin and Kusumaatmaja2018), colour-fluid model (Leclaire et al. Reference Leclaire, Pellerin, Reggio and Trépanier2013a; Leclaire, Reggio & Trépanier Reference Leclaire, Reggio and Trépanier2013b; Fu et al. Reference Fu, Zhao, Bai, Jin and Cheng2016, Reference Fu, Bai, Bi, Zhao, Jin and Cheng2017; Yu et al. Reference Yu, Liu, Liang and Zhang2019b), and the Shan–Chen type models (Bao & Schaefer Reference Bao and Schaefer2013; Wei et al. Reference Wei, Huang, Hou and Sukop2018).

Here we improve on the free-energy lattice Boltzmann model developed by Semprebon et al. (Reference Semprebon, Krüger and Kusumaatmaja2016). A major progress is that our model allows a wider range of interfacial tension ratios, such that all possible biphasic emulsion morphologies can be captured (Guzowski et al. Reference Guzowski, Korczyk, Jakiela and Garstecki2012), including complete and non-engulfing shapes. The model developed by Semprebon et al. (Reference Semprebon, Krüger and Kusumaatmaja2016) only allows partial engulfing shapes. Coupling the free-energy model with the advantages of the lattice Boltzmann method, we conduct a systematic study on the dynamics of double emulsion formation behaviours in planar hierarchical flow-focusing junctions. We focus on the two-dimensional (2-D) case to reduce the computational time needed for parametric studies. The major physical difference in the flow dynamics between the 2-D and the three-dimensional (3-D) systems lies in the lack of an additional Laplace pressure induced by the out-of-plane curvature (Chen & Deng Reference Chen and Deng2017). Such contribution can accelerate the droplet pinch-off process (Hoang et al. Reference Hoang, Portela, Kleijn, Kreutzer and Steijn2013), especially at large Weber number. However, we believe most of the fundamental flow physics are still involved in the 2-D system and a systematic 2-D study can still capture some of the key qualitative trends in the formation regimes and emulsion sizes as function of the flow rates of each fluid phase.

The paper is organized as follows. In § 2, we describe the improved ternary free-energy model, the lattice Boltzmann method and the boundary conditions involved. In § 3, we validate the model and boundary conditions by Poiseuille flow, moving droplet and static emulsion morphology tests. In § 4, our systematic parametric study allows us to construct a flow regime diagram, where we describe a wide range of formation regimes, including the periodic two-step and one-step double emulsion formation regimes, decussate regime, bidisperse regime and even the continuous structure with multiple inner droplets. Scaling laws are also proposed for the double emulsions produced in the one-step formation regime, and the effects of the interfacial tension ratios and the geometrical parameters are investigated. Finally, we summarize our main findings and forecast prospects for future work in § 5.

2 Numerical method

2.1 Free-energy model

The present model is developed based on the equal-density ternary free-energy lattice Boltzmann model proposed by Semprebon et al. (Reference Semprebon, Krüger and Kusumaatmaja2016). The system is described by the free-energy functional

$$\begin{eqnarray}{\mathcal{H}}=\int _{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}}c_{s}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}\ln \unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}\,\text{d}V+{\mathcal{F}}.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}{\mathcal{H}}=\int _{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}}c_{s}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}\ln \unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}\,\text{d}V+{\mathcal{F}}.\end{eqnarray}$$ The first term is the standard ideal gas term in the lattice Boltzmann method with  $c_{s}=1/\sqrt{3}$ and

$c_{s}=1/\sqrt{3}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}$ the total density. Here,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}$ the total density. Here,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}$ is the system volume. The first term does not affect the phase behaviour. To realise three fluid components, the second term

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}$ is the system volume. The first term does not affect the phase behaviour. To realise three fluid components, the second term  ${\mathcal{F}}$ is introduced and it is given by

${\mathcal{F}}$ is introduced and it is given by

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle {\mathcal{F}} & = & \displaystyle \mathop{\sum }_{m=1}^{3}\int _{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}}(E_{0}(C_{m})+E_{interface}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}C_{m}))\,\text{d}V\nonumber\\ \displaystyle & = & \displaystyle \mathop{\sum }_{m=1}^{3}\int _{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}}\left[\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}}{2}C_{m}^{2}(1-C_{m})^{2}+\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}}{2}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}C_{m})^{2}\right]\,\text{d}V.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle {\mathcal{F}} & = & \displaystyle \mathop{\sum }_{m=1}^{3}\int _{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}}(E_{0}(C_{m})+E_{interface}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}C_{m}))\,\text{d}V\nonumber\\ \displaystyle & = & \displaystyle \mathop{\sum }_{m=1}^{3}\int _{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FA}}\left[\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}}{2}C_{m}^{2}(1-C_{m})^{2}+\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}}{2}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}C_{m})^{2}\right]\,\text{d}V.\end{eqnarray}$$ It is constructed using a double-well potential form for the bulk free energy  $E_{0}(C_{m})=(\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}/2)C_{m}^{2}(1-C_{m})^{2}$ and a square gradient term for the interface region

$E_{0}(C_{m})=(\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}/2)C_{m}^{2}(1-C_{m})^{2}$ and a square gradient term for the interface region  $E_{interface}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}C_{m})=(\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}/2)(\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}C_{m})^{2}$. Here,

$E_{interface}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}C_{m})=(\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}/2)(\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}C_{m})^{2}$. Here,  $C_{m}$ (

$C_{m}$ ( $m=1,2,3$) are the concentration fractions with two minimum values at

$m=1,2,3$) are the concentration fractions with two minimum values at  $C_{m}=0$ and

$C_{m}=0$ and  $C_{m}=1$ for each component

$C_{m}=1$ for each component  $m$. In the current model, all components have the same density

$m$. In the current model, all components have the same density  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}_{m}$, which we have set to be 1.0 for simplicity. Thus the total density is related to the concentration fractions by defining

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}_{m}$, which we have set to be 1.0 for simplicity. Thus the total density is related to the concentration fractions by defining  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}=C_{1}\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}_{1}+C_{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}_{2}+C_{3}\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}_{3}=C_{1}+C_{2}+C_{3}$, which is equal to 1.0 in this model. Three physically meaningful bulk phases termed red, green and blue could be denoted by

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}=C_{1}\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}_{1}+C_{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}_{2}+C_{3}\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}_{3}=C_{1}+C_{2}+C_{3}$, which is equal to 1.0 in this model. Three physically meaningful bulk phases termed red, green and blue could be denoted by  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D63E}=[C_{1}\;\;C_{2}\;\;C_{3}]=[1\;\;0\;\;0]$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D63E}=[C_{1}\;\;C_{2}\;\;C_{3}]=[1\;\;0\;\;0]$,  $[0\;\;1\;\;0]$ and

$[0\;\;1\;\;0]$ and  $[0\;\;0\;\;1]$, respectively. Here,

$[0\;\;0\;\;1]$, respectively. Here,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$ is the interface width parameter. The interfacial tension between red–green phases

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}$ is the interface width parameter. The interfacial tension between red–green phases  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$, red–blue phases

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$, red–blue phases  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}$ and green–blue phases

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}$ and green–blue phases  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}$ are related to different

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}$ are related to different  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}$ through

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}$ through

$$\begin{eqnarray}\left.\begin{array}{@{}c@{}}\displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}=\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}}{6}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{1}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{2}),\\ \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}=\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}}{6}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{1}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{3}),\\ \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}=\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}}{6}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{2}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{3}).\end{array}\right\}\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\left.\begin{array}{@{}c@{}}\displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}=\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}}{6}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{1}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{2}),\\ \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}=\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}}{6}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{1}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{3}),\\ \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}=\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}}{6}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{2}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{3}).\end{array}\right\}\end{eqnarray}$$ To capture the interface dynamics, two order parameters  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ are introduced as

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ are introduced as

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=C_{1}-C_{2},\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=C_{3},\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=C_{1}-C_{2},\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=C_{3},\end{eqnarray}$$ and the original concentration fields can be reversely obtained from  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ via

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ via  $C_{1}=(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}-\unicode[STIX]{x1D713})/2$,

$C_{1}=(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}-\unicode[STIX]{x1D713})/2$,  $C_{2}=(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}-\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}-\unicode[STIX]{x1D713})/2$ and

$C_{2}=(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}-\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}-\unicode[STIX]{x1D713})/2$ and  $C_{3}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$. The order parameters and the hydrodynamics of the ternary fluid system are governed by two Cahn–Hilliard equations, the continuity and the Navier–Stokes equations

$C_{3}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$. The order parameters and the hydrodynamics of the ternary fluid system are governed by two Cahn–Hilliard equations, the continuity and the Navier–Stokes equations

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x2202}_{t}\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }(\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}\boldsymbol{v})=M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FB}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}, & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x2202}_{t}\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }(\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}\boldsymbol{v})=M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FB}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}, & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ $$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x2202}_{t}\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }(\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}\boldsymbol{v})=M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FB}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}, & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x2202}_{t}\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }(\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}\boldsymbol{v})=M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FB}^{2}\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}, & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ $$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x2202}_{t}\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}\boldsymbol{v})=0, & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x2202}_{t}\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}\boldsymbol{v})=0, & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ $$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x2202}_{t}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}\boldsymbol{v})+\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}\boldsymbol{v}\boldsymbol{v})=\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }[\unicode[STIX]{x1D702}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{v}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{v}^{\text{T}})]-\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}. & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x2202}_{t}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}\boldsymbol{v})+\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}\boldsymbol{v}\boldsymbol{v})=\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }[\unicode[STIX]{x1D702}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{v}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{v}^{\text{T}})]-\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}. & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ Here,  $\boldsymbol{v}$ is the fluid velocity and

$\boldsymbol{v}$ is the fluid velocity and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D702}$ is the dynamic viscosity. The mobility values for

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D702}$ is the dynamic viscosity. The mobility values for  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ are

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ are  $M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}$ and

$M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}$ and  $M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}$. The thermodynamic properties are related to the equations of motion via the chemical potential

$M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}$. The thermodynamic properties are related to the equations of motion via the chemical potential  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}$ and the pressure tensor

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}$ and the pressure tensor  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}$. The chemical potential is defined as the variational derivative of the free energy

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}$. The chemical potential is defined as the variational derivative of the free energy  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{q}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}{\mathcal{F}}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q$, where

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{q}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}{\mathcal{F}}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}q$, where  $q=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C},\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ or

$q=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C},\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ or  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$. The pressure tensor term in (2.8) is constructed by

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$. The pressure tensor term in (2.8) is constructed by  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}c_{s}^{2})+\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D7EC}}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}c_{s}^{2})+\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D7EC}}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D7EC}}=(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}})$. The first term

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D7EC}}=(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}})$. The first term  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}c_{s}^{2})$ is the standard ideal gas term in LBM and it is simply incorporated in the equilibrium distribution function (Briant & Yeomans Reference Briant and Yeomans2004; Zhang Reference Zhang2011). The

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}c_{s}^{2})$ is the standard ideal gas term in LBM and it is simply incorporated in the equilibrium distribution function (Briant & Yeomans Reference Briant and Yeomans2004; Zhang Reference Zhang2011). The  $\boldsymbol{F}=-\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D7EC}}$ term is treated as an external force term in the lattice Boltzmann implementation. The explicit expressions of

$\boldsymbol{F}=-\unicode[STIX]{x1D735}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D7EC}}$ term is treated as an external force term in the lattice Boltzmann implementation. The explicit expressions of  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}}$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}}$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}$ are given in Semprebon et al. (Reference Semprebon, Krüger and Kusumaatmaja2016).

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}$ are given in Semprebon et al. (Reference Semprebon, Krüger and Kusumaatmaja2016).

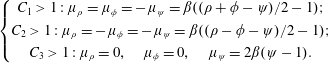

Consider now a case where a red droplet is completely engulfed by a green one and they are submerged in a blue phase fluid at thermodynamic equilibrium. According to the theoretical analysis of Guzowski et al. (Reference Guzowski, Korczyk, Jakiela and Garstecki2012), the interfacial tensions should satisfy  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}>\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$. Given the relation between the

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}>\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$. Given the relation between the  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}$ values in (2.3), one can easily find that

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}$ values in (2.3), one can easily find that  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{2}$ should be negative while

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{2}$ should be negative while  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{1}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{1}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{3}$ are positive. In the free-energy model, the negative

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{3}$ are positive. In the free-energy model, the negative  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{2}$ will invert the shape of the bulk free-energy profile

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{2}$ will invert the shape of the bulk free-energy profile  $E_{0}(C_{m})$: the two minimum values at 0 and 1.0 become two maximum values as shown by the blue solid line in figure 1. As such, setting one of the

$E_{0}(C_{m})$: the two minimum values at 0 and 1.0 become two maximum values as shown by the blue solid line in figure 1. As such, setting one of the  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}$ to be negative often leads to incorrect results or even numerical instability as the concentration value deviates significantly from [0, 1.0]. A similar situation has been encountered in other lattice Boltzmann models, and a simple remedy has been proposed by introducing an additional free-energy term (see Lee & Liu (Reference Lee and Liu2010) and Abadi et al. (Reference Abadi, Fakhari and Rahimian2018)). Inspired by these works, to solve the problem induced by negative

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}$ to be negative often leads to incorrect results or even numerical instability as the concentration value deviates significantly from [0, 1.0]. A similar situation has been encountered in other lattice Boltzmann models, and a simple remedy has been proposed by introducing an additional free-energy term (see Lee & Liu (Reference Lee and Liu2010) and Abadi et al. (Reference Abadi, Fakhari and Rahimian2018)). Inspired by these works, to solve the problem induced by negative  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}$, here we introduce an additional free-energy term given by

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}$, here we introduce an additional free-energy term given by

$$\begin{eqnarray}E_{a}(C_{m})=\left\{\begin{array}{@{}ll@{}}\displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}C_{m}^{2}, & C_{m}<0,\\ \displaystyle 0, & 0\leqslant C_{m}\leqslant 1,\\ \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}(C_{m}-1)^{2}, & C_{m}>1,\end{array}\right.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}E_{a}(C_{m})=\left\{\begin{array}{@{}ll@{}}\displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}C_{m}^{2}, & C_{m}<0,\\ \displaystyle 0, & 0\leqslant C_{m}\leqslant 1,\\ \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}(C_{m}-1)^{2}, & C_{m}>1,\end{array}\right.\end{eqnarray}$$ where  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$ is an adjustable positive parameter controlling the slope of the energy profile

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$ is an adjustable positive parameter controlling the slope of the energy profile  $E_{0}+E_{a}$ as depicted by the red dashed line in figure 1. Since we add a new free-energy term in (2.9), additional terms should be included in the chemical potentials accordingly, which are listed in appendix A.

$E_{0}+E_{a}$ as depicted by the red dashed line in figure 1. Since we add a new free-energy term in (2.9), additional terms should be included in the chemical potentials accordingly, which are listed in appendix A.

Figure 1. Illustration of the bulk free-energy profile without (blue solid line) and with (red dashed line) the additional free-energy term  $E_{a}$, given by (2.9), for a negative

$E_{a}$, given by (2.9), for a negative  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}$.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{m}$.

Figure 2. (a) Illustration of the moving droplet set-up; (b1–b3) time histories of  $X_{d}$ for

$X_{d}$ for  $u_{max}=1.5\times 10^{-3}$,

$u_{max}=1.5\times 10^{-3}$,  $3.0\times 10^{-4}$ and

$3.0\times 10^{-4}$ and  $7.5\times 10^{-5}$ with different convective boundary conditions; (c1–c3) typical snapshots of the droplet shape and velocity vectors when the droplet passes through the outlet layer with each CBC boundary at

$7.5\times 10^{-5}$ with different convective boundary conditions; (c1–c3) typical snapshots of the droplet shape and velocity vectors when the droplet passes through the outlet layer with each CBC boundary at  $u_{max}$ corresponding to (b1–b3), respectively. The

$u_{max}$ corresponding to (b1–b3), respectively. The  $X_{d}$ and time values are normalized using

$X_{d}$ and time values are normalized using  $X_{d}^{\ast }=X_{d}/D$ and

$X_{d}^{\ast }=X_{d}/D$ and  $t^{\ast }=tu_{max}/D$.

$t^{\ast }=tu_{max}/D$.

2.2 Lattice Boltzmann method

To solve (2.5)–(2.8) using the lattice Boltzmann method, three distribution functions are introduced:  $f_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)$ for the density, and

$f_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)$ for the density, and  $g_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)$ and

$g_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)$ and  $h_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)$ for the order parameters

$h_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)$ for the order parameters  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$, respectively. The distribution functions are discretized in space

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$, respectively. The distribution functions are discretized in space  $\boldsymbol{r}$ and time

$\boldsymbol{r}$ and time  $t$, according to a set of lattice velocity vectors

$t$, according to a set of lattice velocity vectors  $\boldsymbol{e}_{i}$. In the D2Q9 discrete scheme (two-dimension with nine discrete velocities) used here, the lattice velocities are given as

$\boldsymbol{e}_{i}$. In the D2Q9 discrete scheme (two-dimension with nine discrete velocities) used here, the lattice velocities are given as  $\boldsymbol{e}_{0}=(0,0)$,

$\boldsymbol{e}_{0}=(0,0)$,  $\boldsymbol{e}_{1,3}=(\pm 1,0)$,

$\boldsymbol{e}_{1,3}=(\pm 1,0)$,  $\boldsymbol{e}_{2,4}=(0,\pm 1)$,

$\boldsymbol{e}_{2,4}=(0,\pm 1)$,  $\boldsymbol{e}_{5,7}=(\pm 1,\pm 1)$ and

$\boldsymbol{e}_{5,7}=(\pm 1,\pm 1)$ and  $\boldsymbol{e}_{6,8}=(\mp 1,\pm 1)$, as shown in figure 2(a). The time evolution of the distribution functions includes the collision and streaming steps, which can be written as

$\boldsymbol{e}_{6,8}=(\mp 1,\pm 1)$, as shown in figure 2(a). The time evolution of the distribution functions includes the collision and streaming steps, which can be written as

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle f_{i}(\boldsymbol{r}+\boldsymbol{e}_{\boldsymbol{i}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D739}_{\boldsymbol{t}},t+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{t}) & = & \displaystyle f_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)-\frac{1}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{f}}[f_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)-f_{i}^{eq}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C},\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}})]\nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle +\,[f_{i}^{eq}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C},\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}})-f_{i}^{eq}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C},\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}})],\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle f_{i}(\boldsymbol{r}+\boldsymbol{e}_{\boldsymbol{i}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D739}_{\boldsymbol{t}},t+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{t}) & = & \displaystyle f_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)-\frac{1}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{f}}[f_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)-f_{i}^{eq}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C},\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}})]\nonumber\\ \displaystyle & & \displaystyle +\,[f_{i}^{eq}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C},\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}})-f_{i}^{eq}(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C},\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}})],\end{eqnarray}$$ $$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle g_{i}(\boldsymbol{r}+\boldsymbol{e}_{\boldsymbol{i}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D739}_{\boldsymbol{t}},t+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{t})=g_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)-\frac{1}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{g}}[g_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)-g_{i}^{eq}(\boldsymbol{r},t)], & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle g_{i}(\boldsymbol{r}+\boldsymbol{e}_{\boldsymbol{i}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D739}_{\boldsymbol{t}},t+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{t})=g_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)-\frac{1}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{g}}[g_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)-g_{i}^{eq}(\boldsymbol{r},t)], & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ $$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle h_{i}(\boldsymbol{r}+\boldsymbol{e}_{\boldsymbol{i}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D739}_{\boldsymbol{t}},t+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{t})=h_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)-\frac{1}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{h}}[h_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)-h_{i}^{eq}(\boldsymbol{r},t)]. & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle h_{i}(\boldsymbol{r}+\boldsymbol{e}_{\boldsymbol{i}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D739}_{\boldsymbol{t}},t+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{t})=h_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)-\frac{1}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{h}}[h_{i}(\boldsymbol{r},t)-h_{i}^{eq}(\boldsymbol{r},t)]. & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ Here, the force term is implemented through the exact difference method (Kupershtokh, Medvedev & Karpov Reference Kupershtokh, Medvedev and Karpov2009; Mazloomi, Chikatamarla & Karlin Reference Mazloomi, Chikatamarla and Karlin2015), which is expressed as the last two terms enclosed in brackets in (2.10), with  $\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}}=\sum _{i}f_{i}\boldsymbol{e}_{i}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}$, i.e. the velocity without the force term, and

$\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}}=\sum _{i}f_{i}\boldsymbol{e}_{i}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}$, i.e. the velocity without the force term, and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}}=\boldsymbol{F}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}$. The lattice time step

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}}=\boldsymbol{F}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}$. The lattice time step  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{t}$ is set to be 1.0. Here,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}_{t}$ is set to be 1.0. Here,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{f}$ is the relaxation parameter given by

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{f}$ is the relaxation parameter given by  $1/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{f}=C_{1}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{1}+C_{2}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{2}+C_{3}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{3}$, where

$1/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{f}=C_{1}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{1}+C_{2}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{2}+C_{3}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{3}$, where  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{1,2,3}$ are related to the viscosity of each fluid by

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{1,2,3}$ are related to the viscosity of each fluid by  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{1,2,3}=3\unicode[STIX]{x1D702}_{r,g,b}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}+1/2$, respectively (Krüger et al. Reference Krüger, Kusumaatmaja, Kuzmin, Shardt, Silva and Viggen2017);

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{1,2,3}=3\unicode[STIX]{x1D702}_{r,g,b}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}+1/2$, respectively (Krüger et al. Reference Krüger, Kusumaatmaja, Kuzmin, Shardt, Silva and Viggen2017);  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{g}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{g}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{h}$ are the relaxation parameters that are related to the mobility parameters

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{h}$ are the relaxation parameters that are related to the mobility parameters  $M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}$ and

$M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}$ and  $M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}$ in the Cahn–Hilliard equations through

$M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}$ in the Cahn–Hilliard equations through

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6E4}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}\left(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{g}-\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t}{2}\right), & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6E4}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}\left(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{g}-\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t}{2}\right), & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ $$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6E4}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}\left(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{h}-\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t}{2}\right), & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D6E4}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}\left(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70F}_{h}-\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t}{2}\right), & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ where  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6E4}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6E4}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6E4}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}$ are two tunable parameters. The mobility values

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6E4}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}$ are two tunable parameters. The mobility values  $M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}$ and

$M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}$ and  $M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}$ are relevant for the time scale of Cahn–Hilliard diffusion and the relaxation time of the interface. Generally, the mobility values should be sufficiently large to retain the interfacial thickness, but small enough to ensure the reasonable damping of the convective term (Jacqmin Reference Jacqmin1999; Lim & Lam Reference Lim and Lam2013). At present it remains an open problem to assign mobility values in numerical studies. Indeed most papers use comparison with experiments to set the values, and one common solution is to use mobility related dimensionless parameters, e.g. the Peclet number (

$M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}$ are relevant for the time scale of Cahn–Hilliard diffusion and the relaxation time of the interface. Generally, the mobility values should be sufficiently large to retain the interfacial thickness, but small enough to ensure the reasonable damping of the convective term (Jacqmin Reference Jacqmin1999; Lim & Lam Reference Lim and Lam2013). At present it remains an open problem to assign mobility values in numerical studies. Indeed most papers use comparison with experiments to set the values, and one common solution is to use mobility related dimensionless parameters, e.g. the Peclet number ( $Pe$). In our microfluidic study, a characteristic

$Pe$). In our microfluidic study, a characteristic  $Pe$ is defined based on the middle phase fluid as

$Pe$ is defined based on the middle phase fluid as  $Pe_{m}=(u_{m}w_{1})/(M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{2})$. The absolute values of

$Pe_{m}=(u_{m}w_{1})/(M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D705}_{2})$. The absolute values of  $Pe_{m}$ used is generally of the order of

$Pe_{m}$ used is generally of the order of  $O(10){-}O(80)$, which is of similar magnitude to those used in previous two-phase droplet behaviour studies (Menech Reference Menech2006; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Yue, Feng, Ollivier-Gooch and Hu2010; Shardt, Mitra & Derksen Reference Shardt, Mitra and Derksen2014). Moreover,

$O(10){-}O(80)$, which is of similar magnitude to those used in previous two-phase droplet behaviour studies (Menech Reference Menech2006; Zhou et al. Reference Zhou, Yue, Feng, Ollivier-Gooch and Hu2010; Shardt, Mitra & Derksen Reference Shardt, Mitra and Derksen2014). Moreover,  $M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}=M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}/3$ is considered to assign symmetric mobility for each concentration component (Semprebon et al. Reference Semprebon, Krüger and Kusumaatmaja2016).

$M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}=M_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}/3$ is considered to assign symmetric mobility for each concentration component (Semprebon et al. Reference Semprebon, Krüger and Kusumaatmaja2016).

Here,  $f_{i}^{eq}$,

$f_{i}^{eq}$,  $g_{i}^{eq}$ and

$g_{i}^{eq}$ and  $h_{i}^{eq}$ are the local equilibrium distribution functions, which are given by

$h_{i}^{eq}$ are the local equilibrium distribution functions, which are given by

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle f_{i}^{eq}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}[1+3\boldsymbol{e}_{i}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}}+{\textstyle \frac{9}{2}}(\boldsymbol{e}_{i}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}})^{2}-{\textstyle \frac{3}{2}}\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}}^{2}], & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle f_{i}^{eq}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{i}\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}[1+3\boldsymbol{e}_{i}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}}+{\textstyle \frac{9}{2}}(\boldsymbol{e}_{i}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}})^{2}-{\textstyle \frac{3}{2}}\widetilde{\boldsymbol{u}}^{2}], & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ $$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle g_{i}^{eq}=\left\{\begin{array}{@{}ll@{}}\displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{i}\left[3\unicode[STIX]{x1D6E4}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}+3\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}\boldsymbol{e}_{i}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v}+\frac{9\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}{2}(\boldsymbol{e}_{i}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v})^{2}-\frac{3\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}{2}\boldsymbol{v}^{2}\right], & i=1{-}8,\\ \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D719}-\mathop{\sum }_{i=1}^{8}g_{i}^{eq}, & i=0,\end{array}\right. & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle g_{i}^{eq}=\left\{\begin{array}{@{}ll@{}}\displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{i}\left[3\unicode[STIX]{x1D6E4}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}+3\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}\boldsymbol{e}_{i}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v}+\frac{9\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}{2}(\boldsymbol{e}_{i}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v})^{2}-\frac{3\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}}{2}\boldsymbol{v}^{2}\right], & i=1{-}8,\\ \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D719}-\mathop{\sum }_{i=1}^{8}g_{i}^{eq}, & i=0,\end{array}\right. & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ $$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle h_{i}^{eq}=\left\{\begin{array}{@{}ll@{}}\displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{i}\left[3\unicode[STIX]{x1D6E4}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}+3\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}\boldsymbol{e}_{i}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v}+\frac{9\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}{2}(\boldsymbol{e}_{i}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v})^{2}-\frac{3\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}{2}\boldsymbol{v}^{2}\right], & i=1{-}8,\\ \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D713}-\mathop{\sum }_{i=1}^{8}h_{i}^{eq}, & i=0,\end{array}\right. & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle h_{i}^{eq}=\left\{\begin{array}{@{}ll@{}}\displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{i}\left[3\unicode[STIX]{x1D6E4}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}\unicode[STIX]{x1D707}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}+3\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}\boldsymbol{e}_{i}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v}+\frac{9\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}{2}(\boldsymbol{e}_{i}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v})^{2}-\frac{3\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}}{2}\boldsymbol{v}^{2}\right], & i=1{-}8,\\ \displaystyle \unicode[STIX]{x1D713}-\mathop{\sum }_{i=1}^{8}h_{i}^{eq}, & i=0,\end{array}\right. & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ where the weight coefficients  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{i}$ are given by

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{i}$ are given by  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{0}=4/9$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{0}=4/9$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{1-4}=1/9$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{1-4}=1/9$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{5-8}=1/36$. The macroscopic variables are related to the distribution functions through

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{5-8}=1/36$. The macroscopic variables are related to the distribution functions through

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}=\mathop{\sum }_{i}f_{i},\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}\boldsymbol{v}=\mathop{\sum }_{i}f_{i}\boldsymbol{e}_{i}+\frac{\boldsymbol{F}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t}{2},\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=\mathop{\sum }_{i}g_{i},\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=\mathop{\sum }_{i}h_{i}.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}=\mathop{\sum }_{i}f_{i},\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}\boldsymbol{v}=\mathop{\sum }_{i}f_{i}\boldsymbol{e}_{i}+\frac{\boldsymbol{F}\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t}{2},\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D719}=\mathop{\sum }_{i}g_{i},\quad \unicode[STIX]{x1D713}=\mathop{\sum }_{i}h_{i}.\end{eqnarray}$$2.3 Boundary conditions

The boundary conditions involved in the present study contain the no-slip boundary, the wetting boundary and the inlet–outlet boundary. The no-slip boundary condition is used on the solid walls, which is realized by the halfway bounceback rule (Ladd Reference Ladd1994). The solid walls should have a preferential affinity with the continuous phase fluid to generate stable droplets/emulsions (Abate et al. Reference Abate, Thiele and Weitz2011). Fu et al. (Reference Fu, Zhao, Bai, Jin and Cheng2016) successfully implemented the wetting boundary condition by setting a fictive density on the walls in a lattice Boltzmann ternary colour-fluid model. Similarly for the free-energy model used here, the macroscopic values of  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ on the walls are designated to be the same as those of the continuous phase fluid that is assumed to completely wet the walls. For the velocity inlet, the Zou–He velocity boundary condition (Zou & He Reference Zou and He1997) is applied to solve the unknown density distribution functions of

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ on the walls are designated to be the same as those of the continuous phase fluid that is assumed to completely wet the walls. For the velocity inlet, the Zou–He velocity boundary condition (Zou & He Reference Zou and He1997) is applied to solve the unknown density distribution functions of  $f_{i}$. To obtain the unknown

$f_{i}$. To obtain the unknown  $g_{i}$ and

$g_{i}$ and  $h_{i}$ values at the inlet, the method used by Hao & Cheng (Reference Hao and Cheng2009) and Liu & Zhang (Reference Liu and Zhang2011) is adopted. Take figure 2(a) for instance, given an inlet boundary with the inflow direction pointing to the right,

$h_{i}$ values at the inlet, the method used by Hao & Cheng (Reference Hao and Cheng2009) and Liu & Zhang (Reference Liu and Zhang2011) is adopted. Take figure 2(a) for instance, given an inlet boundary with the inflow direction pointing to the right,  $g_{1,5,8}$ and

$g_{1,5,8}$ and  $h_{1,5,8}$ are unknown after the streaming step. We assume that one pure single fluid exists at the inlet, where the prescribed values of

$h_{1,5,8}$ are unknown after the streaming step. We assume that one pure single fluid exists at the inlet, where the prescribed values of  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ are

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ are  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}_{in}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}_{in}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}_{in}$, respectively. The sum of the unknown distribution functions can be solved according to (2.18), and then

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}_{in}$, respectively. The sum of the unknown distribution functions can be solved according to (2.18), and then  $g_{1,5,8}$ and

$g_{1,5,8}$ and  $h_{1,5,8}$ are allocated by their weight factors as

$h_{1,5,8}$ are allocated by their weight factors as

$$\begin{eqnarray}\left.g_{i}\vphantom{\Big|}\right|_{i=1,5,8}=\frac{g^{\ast }\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{1}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{5}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{8}},\quad g^{\ast }=g_{1}+g_{5}+g_{8}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}_{in}-\mathop{\sum }_{i}\left.g_{i}\vphantom{\Big|}\right|_{i=0,2,3,4,6,7},\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\left.g_{i}\vphantom{\Big|}\right|_{i=1,5,8}=\frac{g^{\ast }\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{1}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{5}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{8}},\quad g^{\ast }=g_{1}+g_{5}+g_{8}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}_{in}-\mathop{\sum }_{i}\left.g_{i}\vphantom{\Big|}\right|_{i=0,2,3,4,6,7},\end{eqnarray}$$ $$\begin{eqnarray}\left.h_{i}\vphantom{\Big|}\right|_{i=1,5,8}=\frac{h^{\ast }\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{1}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{5}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{8}},\quad h^{\ast }=h_{1}+h_{5}+h_{8}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}_{in}-\mathop{\sum }_{i}\left.h_{i}\vphantom{\Big|}\right|_{i=0,2,3,4,6,7}.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\left.h_{i}\vphantom{\Big|}\right|_{i=1,5,8}=\frac{h^{\ast }\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{i}}{\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{1}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{5}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D714}_{8}},\quad h^{\ast }=h_{1}+h_{5}+h_{8}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}_{in}-\mathop{\sum }_{i}\left.h_{i}\vphantom{\Big|}\right|_{i=0,2,3,4,6,7}.\end{eqnarray}$$ For the outlet boundary, the convective boundary condition (CBC) (Lou, Guo & Shi Reference Lou, Guo and Shi2013; Chen & Deng Reference Chen and Deng2017) is used for its good performance in multicomponent flow simulations. In the present model, the CBC is harnessed in two aspects. One is for the unknown distribution functions  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}_{i}=f_{i}$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}_{i}=f_{i}$,  $g_{i}$ and

$g_{i}$ and  $h_{i}$ at the outlet layer (

$h_{i}$ at the outlet layer ( $x=L_{x}$):

$x=L_{x}$):

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}_{i}(L_{x},y,t+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t)=\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}_{i}(L_{x},y,t)+\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}(L_{x}-1,y,t)\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}_{i}(L_{x}-1,y,t+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t)}{1+\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}(L_{x}-1,y,t)}.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}_{i}(L_{x},y,t+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t)=\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}_{i}(L_{x},y,t)+\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}(L_{x}-1,y,t)\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}_{i}(L_{x}-1,y,t+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t)}{1+\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}(L_{x}-1,y,t)}.\end{eqnarray}$$ The other is for the macroscopic quantities, such as  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}^{\prime }=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}^{\prime }=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70C}$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D719}$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D713}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D7EC}}$ on the ghost layer right outside the outlet, i.e.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D64B}_{\unicode[STIX]{x1D7EC}}$ on the ghost layer right outside the outlet, i.e.  $x=L_{x}+1$, which is needed to compute the derivative terms at the outlet fluid layer:

$x=L_{x}+1$, which is needed to compute the derivative terms at the outlet fluid layer:

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}^{\prime }(L_{x}+1,y,t+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t)=\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}^{\prime }(L_{x}+1,y,t)+\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}(L_{x},y,t)\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}^{\prime }(L_{x},y,t+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t)}{1+\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}(L_{x},y,t)}.\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}^{\prime }(L_{x}+1,y,t+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t)=\frac{\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}^{\prime }(L_{x}+1,y,t)+\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}(L_{x},y,t)\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}^{\prime }(L_{x},y,t+\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FF}t)}{1+\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}(L_{x},y,t)}.\end{eqnarray}$$ Here,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$ is the characteristic velocity normal to the outlet boundary. For simplicity, we have explicitly computed

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$ is the characteristic velocity normal to the outlet boundary. For simplicity, we have explicitly computed  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}_{i}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}_{i}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}^{\prime }$ through

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D712}^{\prime }$ through  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$ at time

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$ at time  $t$. Three common choices for

$t$. Three common choices for  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$ in convective boundary conditions are the average velocity (CBC-AV), local velocity (CBC-LV) and the maximum velocity (CBC-MV) (Lou et al. Reference Lou, Guo and Shi2013).

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D701}$ in convective boundary conditions are the average velocity (CBC-AV), local velocity (CBC-LV) and the maximum velocity (CBC-MV) (Lou et al. Reference Lou, Guo and Shi2013).

3 Model validation

3.1 Convective outlet boundary conditions

In this section, the performance of the CBC in the present model is tested by simulating a single-phase Poiseuille flow and a Poiseuille flow with a moving droplet. In the single-phase Poiseuille flow settings, a fluid with viscosity of 0.167 flows in the  $x$ direction with a maximum velocity of

$x$ direction with a maximum velocity of  $u_{max}=0.0015$ in a computational domain of

$u_{max}=0.0015$ in a computational domain of  $L_{x}\times L_{y}=99\times 39$. No-slip boundaries are used both on the top and bottom walls. The Zou–He velocity inlet is applied with a parabolic velocity distribution given as

$L_{x}\times L_{y}=99\times 39$. No-slip boundaries are used both on the top and bottom walls. The Zou–He velocity inlet is applied with a parabolic velocity distribution given as

$$\begin{eqnarray}u_{x}(y)=\frac{-4u_{max}(y-y_{1})(y-y_{2})}{(y_{2}-y_{1})^{2}},\quad 1\leqslant y\leqslant L_{y}-1,\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}u_{x}(y)=\frac{-4u_{max}(y-y_{1})(y-y_{2})}{(y_{2}-y_{1})^{2}},\quad 1\leqslant y\leqslant L_{y}-1,\end{eqnarray}$$ where  $y_{1}=0.5$ and

$y_{1}=0.5$ and  $y_{2}=L_{y}-0.5$ are the locations of the bottom and top walls. All three options of the CBC mentioned above are implemented at the outlet, and their accuracy is quantified using the relative velocity error computed by

$y_{2}=L_{y}-0.5$ are the locations of the bottom and top walls. All three options of the CBC mentioned above are implemented at the outlet, and their accuracy is quantified using the relative velocity error computed by  $E_{u}=\sqrt{\sum ((u_{x})_{ana}-(u_{x})_{simu})^{2}/\sum ((u_{x})_{ana}^{2})}$, where

$E_{u}=\sqrt{\sum ((u_{x})_{ana}-(u_{x})_{simu})^{2}/\sum ((u_{x})_{ana}^{2})}$, where  $(u_{x})_{ana}$ is the analytical velocity given by (3.1) and

$(u_{x})_{ana}$ is the analytical velocity given by (3.1) and  $(u_{x})_{simu}$ denotes the simulated velocity. The obtained values of

$(u_{x})_{simu}$ denotes the simulated velocity. The obtained values of  $E_{u}$ under CBC-AV, CBC-LV and CBC-MV conditions are

$E_{u}$ under CBC-AV, CBC-LV and CBC-MV conditions are  $1.449\times 10^{-4}$,

$1.449\times 10^{-4}$,  $1.151\times 10^{-4}$ and

$1.151\times 10^{-4}$ and  $2.254\times 10^{-4}$ in the middle of the channel, i.e.

$2.254\times 10^{-4}$ in the middle of the channel, i.e.  $x=49$, and

$x=49$, and  $1.454\times 10^{-4}$,

$1.454\times 10^{-4}$,  $5.4\times 10^{-3}$ and

$5.4\times 10^{-3}$ and  $3.144\times 10^{-4}$ at the outlet layer. It is seen that all three outlet boundaries give satisfactory results for flow far away from the outlet. However, the accuracy at the outlet layer varies: the CBC-AV provides the highest accuracy, CBC-MV is slightly lower and CBC-LV shows the poorest performance.

$3.144\times 10^{-4}$ at the outlet layer. It is seen that all three outlet boundaries give satisfactory results for flow far away from the outlet. However, the accuracy at the outlet layer varies: the CBC-AV provides the highest accuracy, CBC-MV is slightly lower and CBC-LV shows the poorest performance.

In the moving droplet test, a droplet with radius  $R=20$ is centred at

$R=20$ is centred at  $(60,49.5)$ in a channel of

$(60,49.5)$ in a channel of  $L_{x}\times L_{y}=199\times 99$, as illustrated in figure 2(a). The two fluid phases have the same viscosity of 0.167 and their interfacial tension

$L_{x}\times L_{y}=199\times 99$, as illustrated in figure 2(a). The two fluid phases have the same viscosity of 0.167 and their interfacial tension  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}$ is 0.005. All the boundary conditions are the same as those in the single-phase Poiseuille flow simulations. The whole fluid domain is initialized with a uniform parabolic velocity profile as given by (3.1). Three different values of

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}$ is 0.005. All the boundary conditions are the same as those in the single-phase Poiseuille flow simulations. The whole fluid domain is initialized with a uniform parabolic velocity profile as given by (3.1). Three different values of  $u_{max}$ are tested, i.e.

$u_{max}$ are tested, i.e.  $u_{max}=1.5\times 10^{-3}$,

$u_{max}=1.5\times 10^{-3}$,  $3.0\times 10^{-4}$ and

$3.0\times 10^{-4}$ and  $7.5\times 10^{-5}$. To make a quantitative comparison, the time history of the distance

$7.5\times 10^{-5}$. To make a quantitative comparison, the time history of the distance  $X_{d}$ measured from the inlet to the leftmost point of the droplet is recorded and shown in figure 2(b1–b3). The

$X_{d}$ measured from the inlet to the leftmost point of the droplet is recorded and shown in figure 2(b1–b3). The  $X_{d}$ and time are normalized using

$X_{d}$ and time are normalized using  $X_{d}^{\ast }=X_{d}/D$ and

$X_{d}^{\ast }=X_{d}/D$ and  $t^{\ast }=tu_{max}/D$, where

$t^{\ast }=tu_{max}/D$, where  $D$ is the droplet diameter. The

$D$ is the droplet diameter. The  $X_{d}^{\ast }$ curve of the droplet moving in a longer channel (

$X_{d}^{\ast }$ curve of the droplet moving in a longer channel ( $L_{x}\times L_{y}=399\times 99$) computed with CBC-AV is used as the reference result for each flow condition. Note in figure 2(b1–b3) that the sharp decrease of

$L_{x}\times L_{y}=399\times 99$) computed with CBC-AV is used as the reference result for each flow condition. Note in figure 2(b1–b3) that the sharp decrease of  $X_{d}^{\ast }$ occurs when the droplet completely moves out of the channel.

$X_{d}^{\ast }$ occurs when the droplet completely moves out of the channel.

It is seen in figure 2(b1–b3) that the  $X_{d}^{\ast }$ increases linearly with time and agrees with the reference line before the droplet interface touches the outlet boundary for each of the tested flow conditions. The option of the convective boundary conditions has little effect on the flow behaviours away from the outlet. Deviations in

$X_{d}^{\ast }$ increases linearly with time and agrees with the reference line before the droplet interface touches the outlet boundary for each of the tested flow conditions. The option of the convective boundary conditions has little effect on the flow behaviours away from the outlet. Deviations in  $X_{d}^{\ast }$ curves from the reference lines occur at around

$X_{d}^{\ast }$ curves from the reference lines occur at around  $t^{\ast }=4$ when the droplet passes through the outlet. Compared to the reference lines, the case with CBC-AV slightly lags behind, and the case with CBC-MV moves a bit faster. Also, the case with CBC-LV gives the most accurate results for moderate characteristic velocities, as illustrated in figure 2(b1,b2). The deviation in

$t^{\ast }=4$ when the droplet passes through the outlet. Compared to the reference lines, the case with CBC-AV slightly lags behind, and the case with CBC-MV moves a bit faster. Also, the case with CBC-LV gives the most accurate results for moderate characteristic velocities, as illustrated in figure 2(b1,b2). The deviation in  $X_{d}^{\ast }$ increases as

$X_{d}^{\ast }$ increases as  $u_{max}$ decreases for the cases with CBC-AV and CBC-MV. When the

$u_{max}$ decreases for the cases with CBC-AV and CBC-MV. When the  $u_{max}$ is of the same order of magnitude as the spurious velocities of the present model, i.e.

$u_{max}$ is of the same order of magnitude as the spurious velocities of the present model, i.e.  $u_{max}=7.5\times 10^{-5}$ in (b3), numerical instability arises for the case with CBC-LV, whereas the cases with CBC-AV and CBC-MV show better robustness. Due to the low velocity often encountered in double emulsion generation, the robustness of the outlet boundary at low velocities is of great significance. On the other hand, for low velocity cases shown in (c2,c3), the velocity in regions close to the walls is less affected for the case with CBC-AV than that with CBC-MV. The momentum deficit or surplus around the outlet region could be attributed to the momentum imbalance at the outlet, which is not fully ensured by the CBC when the external force term is solved in the potential form (Li, Jia & Liu Reference Li, Jia and Liu2017). The resulting velocity profile is also affected by the form of the characteristic velocity used in the CBC. Considering all the above tests, CBC-AV generally shows better performance and it is therefore used in the following studies.

$u_{max}=7.5\times 10^{-5}$ in (b3), numerical instability arises for the case with CBC-LV, whereas the cases with CBC-AV and CBC-MV show better robustness. Due to the low velocity often encountered in double emulsion generation, the robustness of the outlet boundary at low velocities is of great significance. On the other hand, for low velocity cases shown in (c2,c3), the velocity in regions close to the walls is less affected for the case with CBC-AV than that with CBC-MV. The momentum deficit or surplus around the outlet region could be attributed to the momentum imbalance at the outlet, which is not fully ensured by the CBC when the external force term is solved in the potential form (Li, Jia & Liu Reference Li, Jia and Liu2017). The resulting velocity profile is also affected by the form of the characteristic velocity used in the CBC. Considering all the above tests, CBC-AV generally shows better performance and it is therefore used in the following studies.

In addition, since we find the flow behaviours are unaffected away from the outlet, we always use channel length which is much larger compared to the typical emulsion droplet, in order to minimise any undesirable effect from the outlet boundary condition.

Figure 3. (a) Morphology diagram for two equal-sized droplets with  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}=0.001$; (b) emulsion shape with

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}=0.001$; (b) emulsion shape with  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}=0$ for

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}=0$ for  $(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg},\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg})=(1.4,0.35)$; (c) emulsion shape with

$(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg},\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg})=(1.4,0.35)$; (c) emulsion shape with  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}=0.0001$ for

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}=0.0001$ for  $(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg},\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg})=(1.4,0.35)$.

$(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg},\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg})=(1.4,0.35)$.

3.2 Morphology diagram

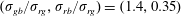

Since the interfacial tension relations are crucial in determining ternary emulsion morphologies (Pannacci et al. Reference Pannacci, Bruus, Bartolo, Etchart, Lockhart, Hennequin, Willaime and Tabeling2008; Guzowski et al. Reference Guzowski, Korczyk, Jakiela and Garstecki2012), another validation test is conducted to show the capability of the current model in simulating a wide range of interfacial tension ratios. Following the theoretical analysis of Guzowski et al. (Reference Guzowski, Korczyk, Jakiela and Garstecki2012), two equal-sized red and green droplets are initially put next to each other and dispersed in the outer blue fluid. Three typical thermodynamic equilibrium morphologies can be obtained depending on the interfacial tension ratios of  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$ and

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$, as divided by the solid lines shown in figure 3(a): (I-A), complete engulfing with the red droplet inside the green one for

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$, as divided by the solid lines shown in figure 3(a): (I-A), complete engulfing with the red droplet inside the green one for  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}>1+\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$; (I-B), complete engulfing with the green droplet inside the red one for

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}>1+\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$; (I-B), complete engulfing with the green droplet inside the red one for  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}>1+\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$; (II), non-engulfing, for

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}>1+\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$; (II), non-engulfing, for  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}<1$, where the red and green droplets tend to separate from each other; (III), partial engulfing (Janus droplet), for

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}<1$, where the red and green droplets tend to separate from each other; (III), partial engulfing (Janus droplet), for  $|(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg})-(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg})|<1$ and

$|(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg})-(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg})|<1$ and  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}>1$, where the interfacial tensions satisfy a Neumann triangle.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}+\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}>1$, where the interfacial tensions satisfy a Neumann triangle.

In our numerical test, the red and green droplets are both initialized with radius  $R=60$ surrounded by the blue fluid in a domain of

$R=60$ surrounded by the blue fluid in a domain of  $L_{x}\times L_{y}=399\times 399$. All the fluid viscosities are 0.167. The initial concentration fractions for three fluids are given by (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Liu, Liang and Zhang2019b)

$L_{x}\times L_{y}=399\times 399$. All the fluid viscosities are 0.167. The initial concentration fractions for three fluids are given by (Yu et al. Reference Yu, Liu, Liang and Zhang2019b)

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle C_{1}(x,y)=0.5+0.5\tanh \left[\frac{R-\sqrt{(x-199.5)^{2}+(y-199.5-R)^{2}}}{2\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}}\right], & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle C_{1}(x,y)=0.5+0.5\tanh \left[\frac{R-\sqrt{(x-199.5)^{2}+(y-199.5-R)^{2}}}{2\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}}\right], & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ $$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle C_{2}(x,y)=0.5+0.5\tanh \left[\frac{R-\sqrt{(x-199.5)^{2}+(y-199.5+R)^{2}}}{2\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}}\right], & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle C_{2}(x,y)=0.5+0.5\tanh \left[\frac{R-\sqrt{(x-199.5)^{2}+(y-199.5+R)^{2}}}{2\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FC}}\right], & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ $$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle C_{3}(x,y)=1-C_{1}(x,y)-C_{2}(x,y). & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$

$$\begin{eqnarray}\displaystyle & \displaystyle C_{3}(x,y)=1-C_{1}(x,y)-C_{2}(x,y). & \displaystyle\end{eqnarray}$$ Periodic boundary conditions are used for all boundaries. To reproduce all the possible morphologies, simulations are performed at various groups of ( $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$): (I-A), complete engulfing with red droplet inside – (0.3, 1.35), (0.75, 1.8), (1.0, 2.05); (I-B), complete engulfing with green droplet inside – (1.4, 0.35), (1.75, 0.7), (2.0, 0.95); (II), non-engulfing – (0.48, 0.48), (0.25, 0.72), (0.75, 0.23); (III), partial engulfing emulsions – (1.0, 1.0), (1.0, 1.5), (1.0, 0.5), (0.5, 1.0), (1.5, 1.0), (100, 100). The interfacial tension

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$): (I-A), complete engulfing with red droplet inside – (0.3, 1.35), (0.75, 1.8), (1.0, 2.05); (I-B), complete engulfing with green droplet inside – (1.4, 0.35), (1.75, 0.7), (2.0, 0.95); (II), non-engulfing – (0.48, 0.48), (0.25, 0.72), (0.75, 0.23); (III), partial engulfing emulsions – (1.0, 1.0), (1.0, 1.5), (1.0, 0.5), (0.5, 1.0), (1.5, 1.0), (100, 100). The interfacial tension  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$ is fixed at 0.005 except for the case with

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$ is fixed at 0.005 except for the case with  $(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg},\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg})=(100,100)$, where

$(\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg},\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg})=(100,100)$, where  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}=0.00001$ is used to reach the high interfacial tension ratio. The value of the coefficient

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}=0.00001$ is used to reach the high interfacial tension ratio. The value of the coefficient  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$ is set to be 0.001 for the additional free-energy term. The simulated equilibrium morphologies are shown by the insets in figure 3(a). Good agreements with theoretical morphologies are achieved for all types of emulsions. Moreover, Pannacci et al. (Reference Pannacci, Bruus, Bartolo, Etchart, Lockhart, Hennequin, Willaime and Tabeling2008) experimentally investigated the equilibrium states of compound emulsions. Their results are presented as a function of the spreading coefficients, i.e.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$ is set to be 0.001 for the additional free-energy term. The simulated equilibrium morphologies are shown by the insets in figure 3(a). Good agreements with theoretical morphologies are achieved for all types of emulsions. Moreover, Pannacci et al. (Reference Pannacci, Bruus, Bartolo, Etchart, Lockhart, Hennequin, Willaime and Tabeling2008) experimentally investigated the equilibrium states of compound emulsions. Their results are presented as a function of the spreading coefficients, i.e.  $S_{i}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{jk}-\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{ij}-\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{ik}$ with

$S_{i}=\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{jk}-\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{ij}-\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{ik}$ with  $i,j,k=r,g,b$, respectively. By converting the values of the interfacial tension ratios tested in figure 3 to spreading coefficients, our numerically obtained emulsion morphologies are also consistent with their experimental observations.

$i,j,k=r,g,b$, respectively. By converting the values of the interfacial tension ratios tested in figure 3 to spreading coefficients, our numerically obtained emulsion morphologies are also consistent with their experimental observations.

It is worth noting that we have investigated the optimal value of the coefficient  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$ in the additional free-energy term introduced in (2.9), varying

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$ in the additional free-energy term introduced in (2.9), varying  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}=0$, 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1 and 1.0 for one typical double emulsion morphology at (

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}=0$, 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1 and 1.0 for one typical double emulsion morphology at ( $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{gb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$) = (1.4, 0.35). The obtained result at

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rb}/\unicode[STIX]{x1D70E}_{rg}$) = (1.4, 0.35). The obtained result at  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}=0$ (corresponding to the model without the additional term) is shown in figure 3(b). As highlighted by the dashed squares in figure 3(b), two unphysical light blue regions caused by negative

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}=0$ (corresponding to the model without the additional term) is shown in figure 3(b). As highlighted by the dashed squares in figure 3(b), two unphysical light blue regions caused by negative  $C_{1}$ appear around the three-phase contact line and lead to incorrect result. The incorrect region is also observed for

$C_{1}$ appear around the three-phase contact line and lead to incorrect result. The incorrect region is also observed for  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}=0.0001$ in figure 3(c). For

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}=0.0001$ in figure 3(c). For  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$ varying from 0.001 to 0.1, the complete engulfing morphology could be successfully reproduced and invisible difference is observed for different values of

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$ varying from 0.001 to 0.1, the complete engulfing morphology could be successfully reproduced and invisible difference is observed for different values of  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$. However, further increasing

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$. However, further increasing  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$ to 1.0 induces numerical instability, which indicates that the

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$ to 1.0 induces numerical instability, which indicates that the  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$ value cannot be large enough to dominate the double-well potential terms. Meanwhile, for the partial engulfing cases, correct morphologies could be captured even without the additional term, and they are generally unaffected by a small additional term. Based on the above findings,

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}$ value cannot be large enough to dominate the double-well potential terms. Meanwhile, for the partial engulfing cases, correct morphologies could be captured even without the additional term, and they are generally unaffected by a small additional term. Based on the above findings,  $\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}=0.001$ will be used in subsequent simulations.

$\unicode[STIX]{x1D6FD}=0.001$ will be used in subsequent simulations.

4 Results and discussion

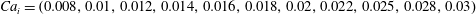

4.1 Previously observed formation regimes and grid independence test

The two-dimensional set-up of the hierarchical flow-focusing device is illustrated in figure 4. The inner red fluid is injected through the leftmost inlet with a width of  $w_{1}$, and the middle green and outer blue fluids are injected by two vertical side inlets with widths of

$w_{1}$, and the middle green and outer blue fluids are injected by two vertical side inlets with widths of  $w_{2}$ and

$w_{2}$ and  $w_{3}$, respectively. All the inlet widths are set equal in this section, i.e.

$w_{3}$, respectively. All the inlet widths are set equal in this section, i.e.  $w_{1}=w_{2}=w_{3}$. The channel connecting the two side inlets has a width of

$w_{1}=w_{2}=w_{3}$. The channel connecting the two side inlets has a width of  $w_{4}=w_{1}$, and the main channel width is

$w_{4}=w_{1}$, and the main channel width is  $w_{5}=1.6w_{1}$. The length of the first inlet is

$w_{5}=1.6w_{1}$. The length of the first inlet is  $w_{6}=2w_{1}$, and the distance between the two side inlets is

$w_{6}=2w_{1}$, and the distance between the two side inlets is  $w_{7}=3w_{1}$. Considering the symmetry of the flow problem in the

$w_{7}=3w_{1}$. Considering the symmetry of the flow problem in the  $y$ direction, only a half of the geometry is simulated and the domain size is

$y$ direction, only a half of the geometry is simulated and the domain size is  $L_{x}\times L_{y}=30w_{1}\times 2w_{1}$. The Zou–He velocity inlet boundary condition (Zou & He Reference Zou and He1997) is used for all the inlets, and the CBC-AV is applied for the outlet. In addition to the no-slip boundary condition, the wetting boundary condition is also imposed on the solid surfaces, where the first and second junctions are fully wetted by the middle and outer phase fluids, respectively.

$L_{x}\times L_{y}=30w_{1}\times 2w_{1}$. The Zou–He velocity inlet boundary condition (Zou & He Reference Zou and He1997) is used for all the inlets, and the CBC-AV is applied for the outlet. In addition to the no-slip boundary condition, the wetting boundary condition is also imposed on the solid surfaces, where the first and second junctions are fully wetted by the middle and outer phase fluids, respectively.

Figure 4. Illustration of the geometry and boundary settings of the planar hierarchical flow-focusing device in this work.

In the following, the subscripts  $i$,

$i$,  $m$ and