The final part of the book explores the influence of the work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) on different audiences. Rolf Lidskog and Göran Sundqvist (Chapter 22) review the different ways in which the IPCC has had influence on international and domestic decision-making processes, and the extent of this influence in the post-Paris context. Jean Carlos Hochsprung Miguel and colleagues (Chapter 23) examine this same question using the concept of ‘civic epistemology’, which helps to explain the different ways in which IPCC reports are perceived in different national political cultures. They in particular show how the legitimacy and credibility of the IPCC is context-dependent. Bård Lahn (Chapter 24) uses the idea of ‘boundary objects’ to also explore the successes and limits of the IPCC’s influence over different political actors and institutions, using examples of objects that circulate between the IPCC and the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Irene Lorenzoni and Jordan Harold (Chapter 25) explore the production, role and efficacy of IPCC ‘visuals’ as a means of communicating climate change to different audiences. Warren Pearce and August Lindemer (Chapter 26) pursue this question about the effectiveness of IPCC communications by examining the IPCC’s communication strategy and the appropriation of IPCC reports by different publics. The final chapter of this section offers a more personalised view of the IPCC’s influence and its future. Clark Miller (Chapter 27) takes a broader view of the production of global knowledge for policy and its related challenges, and offers a proposal of what the IPCC should evolve into over future decades.

Overview

The explicit aim of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is to influence policymaking. By synthesising research on climate change and presenting it to policymakers, the IPCC tries to meet its self-imposed goal of being policy-relevant and policy-neutral, but not policy-prescriptive. The hallmark of the IPCC has been to offer a strong scientific voice demonstrating the necessity of climate policy and action, but without giving firm political advice. Yet scholars have contested the idea of maintaining such a strong boundary between science and policy in the IPCC, questioning whether upholding this boundary has been successful and whether continuing to do so offers a viable way forward. The Paris Agreement provides a new political context for the IPCC, implying a need for solution-oriented assessments. The IPCC itself has also argued that large-scale transformations of society are needed to meet the targets set by the Agreement. To be relevant and influence policymaking in this new political context, the IPCC needs to provide policy advice.

22.1 Introduction

The IPCC is a political organisation in the sense that its assessment reports are designed, decided upon and approved by national governments. Its ambition, however, is to determine the state of knowledge on climate change, and this knowledge assessment is undertaken by researchers. An additional aim of the IPCC is to perform this scholarly work in a way that is policy-relevant (see Chapter 21). This mainly means being relevant for political negotiations and decision-making under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which constitutes the primary political context for the IPCC. Hence the two organisations mutually influence each other.

An early study by Agrawala (Reference Agrawala1998b) qualifies the discussion on political influence by making a distinction between process and outcome. He argued that the IPCC had been influential in terms of process – generating and maintaining societal interest and concern regarding climate change – but also in terms of outcome. Without the IPCC, neither the UNFCCC nor the Kyoto Protocol, with its binding agreements on emission reductions, would have been possible. Furthermore, the many lobby groups funded by the fossil fuel industry and devoted to finding weaknesses in the IPCC reports are (indirect) evidence that the IPCC has influenced policy and politics (Agrawala, Reference Agrawala1998b: 639–640).

Other researchers have, however, questioned these conclusions, stressing that it is difficult to distinguish cause from effect when so many factors other than knowledge influence climate policies (Grundmann, Reference Grundmann2006). De Pryck (Reference De Pryck2018) argues that unilateral causal connections between the IPCC assessments and climate policies are claimed rather than shown, and that this assumed influence is an important part of the IPCC’s self-image. It is far too simple to claim that the IPCC’s First Assessment Report (AR1) in 1990 (AR1) led to the formation of the Convention (1992), the Second in 1995 (AR2) to the Kyoto Protocol, the Third in 2001 (AR3) to a focus on climate adaptation, the Fourth in 2007 (AR4) to the 2 ºC target, and the Fifth in 2013/2014 (AR5) to the Paris Agreement. This oversimplified view of how science influences policy is based on a unidirectional linear model in which scientific knowledge constrains and guides policy actors.

In this chapter we present the political context of the IPCC. This context is external to the Panel, but is also an inherent and crucial factor in the design of its activities. We are therefore critical of a linear understanding of the IPCC’s work, because it separates science from policy and politics, and assumes that knowledge is a necessary prerequisite for political action (Beck, Reference Beck2011a; Lidskog & Sundqvist, Reference Lidskog and Sundqvist2015; Mahony & Hulme, Reference Mahony and Hulme2018). Nevertheless, a linear understanding of the interplay between science and policy is an important part of the IPCC’s self-conception, and is also presupposed by many commentators (Sundqvist et al., Reference Sundqvist, Gasper, St and Clair2018). Contrary to the linear model, we hold that the work of the IPCC involves ongoing, close interaction between science and policy – something which, instead of being denied, should be fully acknowledged.

This contribution begins by presenting the relationship between the IPCC and the UNFCCC and its Paris Agreement. We argue that the Paris Agreement constitutes a new political context for the IPCC and thus imposes new conditions for how scientific knowledge can influence policy and political decision-making (see Chapter 18). We then analyse this new situation through one of the IPCC’s best-known reports: the 1.5 °C report published in 2018 (hereafter SR15) and its demand for transformative change to meet the political goal of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C. To what extent does the IPCC influence policies and politics when the crucial political task is more about initiating and governing transformative change than creating awareness of climate threats? We finally discuss our results in relation to the IPCC’s ambition of not being policy-prescriptive, which means not giving advice to policymakers.

22.2 Solution-oriented Assessments

The use of synthesised assessments is well established today and characterises the international policy landscape on global environmental issues. These global environmental assessments (GEAs) have increased in scope and complexity over time, both in terms of content and focus. A survey shows a large increase in the amount of assessed material, as well as in the number of experts involved in the assessment work. This trend toward increased complexity in content and focus has been described as a shift from scientific evaluations to solution-oriented assessments (from GEAs to SOAs) (Edenhofer & Kowarsch, Reference Edenhofer and Kowarsch2015; Jabbour & Flachsland, Reference Jabbour and Flachsland2017). SOAs require more explicit treatment of the values, objectives and assessments of policy proposals, which makes them more obviously political than GEAs (Haas, Reference Haas2017; Castree et al., Reference Castree, Bellamy and Osaka2021). The IPCC is no exception to this trend.

A radical change in the political context of the IPCC occurred with the adoption of the Paris Agreement in 2015. The Agreement stipulates that signatories must work to keep global warming below 2 ºC whilst ‘pursuing efforts’ to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 ºC. As part of the Agreement, the IPCC was asked to compile a Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 ºC (2018) (SR15), comparing the effects of temperature increases of 1.5 and 2 ºC, and describing possible ways to achieve these goals. The Panel accepted this request, even though the task was more specified than usual for the IPCC (see Chapter 5). The requested report was solution-oriented; its aim was to present possible ways to achieve the temperature target. Yet there was not much research to compile; few studies had been conducted on possible ways to reach the 1.5 ºC target (Hulme, Reference Hulme2016; Livingston & Rummukainen, Reference Livingston and Rummukainen2020).

The SR15 report states that to achieve the goal, radical measures will be needed, including new technologies (negative emissions technologies, NETs) such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). However, these technologies have not been tested on a large scale or brought up for political discussion (Beck & Mahony, Reference Beck and Mahony2018a). Being commissioned to deliver this special report created a new context for the IPCC, both in terms of knowledge evidence and of policy relevance, and necessitated a substantial change in the Panel’s working methods (Ourbak & Tubiana, Reference Ourbak and Tubiana2017; Beck & Mahony, Reference Beck and Mahony2018a; Livingston et al., Reference Livingstone2018). In SR15, the Panel compiled relevant scientific evidence to a lesser extent than in previous assessment reports, and contributed to formulating policy proposals to a greater extent. As a result, the report had a more solution-oriented and prescriptive role, which is strengthened by its strong focus on scenarios – what SR15 calls ‘pathways’. When the Panel includes large-scale investments in nuclear power and NETs as important components of many of the presented pathways, this can and will be interpreted as the Panel advocating these technologies.

The IPCC chairman Hoesung Lee has argued strongly for the use of solution-oriented assessments in order to better serve the UNFCCC (Lee, Reference Lee2015). In practice, however, the IPCC has not taken advantage of this new post-Paris situation in any deeper sense (Hermansen et al., Reference Hermansen, Lahn, Sundqvist and Øye2021), and it still sticks to its original position of being policy-neutral, not policy-prescriptive.

The challenge for the IPCC is not only to present conclusions with high certainty, or projections derived from scenarios, but also to address controversial policy-relevant topics that demand greater inclusion and involvement of the social sciences. Similarly, Carraro and colleagues claim that the IPCC must become better at evaluating policy options on various scales – subnational, national and international – including alternative options for measuring equity and efficiency (Carraro et al., Reference Carraro, Edenhofer, Flachsland, Kolstad, Stavins and Stowe2015). However, this emphasis may lead to controversy; few governments would gladly have their policies evaluated by an international panel, and researchers may not be equipped to handle value-laden and politicised questions in the sensitive manner they require. According to Victor (Reference Victor2015), one of the few social scientists who served as a Coordinating Lead Author in AR5, the IPCC’s ambition to seek consensus and avoid controversial topics has increasingly made it largely irrelevant to climate policy.

In our estimation, the shift to SOA means that the IPCC needs to present policy options and possible ways forward, i.e., pathways. But it must also assess the feasibility and viability of these pathways in order to provide decision-makers with relevant knowledge. This means that social scientific studies need to be better integrated into the assessment work of the IPCC.

22.3 The National Turn in the Paris Agreement

The basic design of the Paris Agreement consists of two interrelated parts. One is national, and is based on the signatory countries’ own voluntary decisions about reducing greenhouse gas emissions – Nationally Determined Contributions, NDCs. The other is global, and sets the common target that the combined measures of the various countries should keep the global average temperature well below 2 °C, and preferably limit it to 1.5 °C.

The Paris Agreement implies a more decentralised global policy regime than previously envisaged, with a national focus and a strong, bottom-up governance system (Jordan et al., Reference Jordan, Huitema, Van Asselt and Forster2018; Aykut et al., Reference Aykut, Morena and Foyer2021). After years of conflict over global distribution principles and which countries should reduce their emissions by how much and by what year, it is now up to individual states to set their own climate targets and deliver on them. Complicated international negotiations can no longer be used as an excuse for prevarication at the national level. However, every fifth year (starting in 2023), the NDCs will be globally reviewed in a process called the Global Stocktake of the Paris Agreement.

This national turn shifts the focus towards defining potential pathways for reaching specified goals (Beck & Mahony, Reference Beck and Mahony2018a). The IPCC now finds itself in a position where national-level policy processes will be decisive, while the global level will continue to be relevant with the Global Stocktake process ratcheting up national ambitions. Of great importance is how the IPCC can fulfil its mandate and remain policy-relevant in this more complex, polycentric and nationally oriented post-Paris policy terrain, where the responses to climate change are becoming more diverse (Hermansen et al., Reference Hermansen, Lahn, Sundqvist and Øye2021). As argued earlier, in this situation characterised by a national turn, the IPCC will have to give more thought to how to support and inspire ongoing work on national and regional levels (Carraro et al., Reference Carraro, Edenhofer, Flachsland, Kolstad, Stavins and Stowe2015; Victor, Reference Victor2015; Livingston et al., Reference Livingstone2018; see also Hulme et al., Reference Hulme2010). The need for this kind of support will increase, as exemplified by NGO initiatives such as ‘Climate Action Tracker’, ‘Climate Analytics’ and ‘Climate Interactive’.

In line with the design of the Paris Agreement, it is mainly at the national level that decisions will be taken that can make the IPCC’s knowledge relevant and thereby increase its ability to influence climate policy. An important reason why the UNFCCC invited the IPCC to produce SR15 in the first place was to ‘inform the preparation of nationally determined contributions’ (UNFCCC, 2015: §20), and SR15 is accordingly expected to support policy formation at the national level, in line with post-Paris global climate policy. Thus, there is a strong link between the Paris Agreement’s national turn and the SR15 report, something which the IPCC has not reflected on to any greater extent. In our view, the IPCC needs to become more self-aware of its important role of providing support, including advice, to ongoing and future national climate-transformation efforts.

22.4 The IPCC on Transformative Change

The topic of transformation, or transformative societal change, in response to climate change has increasingly attracted research attention in the social sciences (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2012; Linnér & Wibeck, Reference Linnér and Wibeck2019). It has been argued that the IPCC plays an instrumental role in producing the visions of societal change used by those arguing for its necessity (Beck et al., Reference Beck and Oomen2021). In SR15, it is explicitly claimed that ‘limiting global warming to 1.5 °C would require substantial societal and technological transformations’ in terms of energy production, land use (agriculture and food), urban infrastructure (transport and buildings) and industrial systems (IPCC, Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai and Pörtner2018a: 56). It also states that the work of achieving a resilient future is fraught with complex moral, practical and political difficulties and inevitable trade-offs.

SR15 presents a manifold of pathways to reach the 1.5 °C target, four of which are selected as illustrative model pathways (IPCC, Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai and Pörtner2018a: Chapter 2). These involve different portfolios of mitigation measures combined with different implementation challenges, including potential synergies and trade-offs with sustainable development. At the same time, they all presuppose a decoupling of economic growth from energy demand and carbon dioxide emissions, and new low-carbon, zero-carbon or even carbon-negative technologies. The differences between the pathways are presented with the help of global indicators, such as final energy demand, renewable share in electricity, primary energy source, and carbon capture and storage. Thus, the SR15 report strongly stresses the need and opportunity to make changes in energy supply.

When it comes to necessary change in the social and economic order, which is stressed at a general level, the pathways do not propose any radical changes. Societal conditions are only taken into consideration in so far as they enable or obstruct technological development. This is the case for all the different pathways that rely heavily on BECCS, whether they are based on reduced energy demand, include a broad focus on sustainability, or imply intensive use of resources and energy. SR15 states that to implement the pathways it is crucial to strengthen policy instruments, enhance multilevel governance and institutional capacities, and enable technological innovations, climate finance, and lifestyle and behavioural change (IPCC, Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai and Pörtner2018a: section 4.4). But apart from these sweeping statements, there is no further elaboration on how to create these conditions in relation to different pathways.

SR15 thus exhibits a paradoxical view of transformative change. It stresses its necessity, but in practice places great hope in technological fixes – technical solutions that do not require structural changes in the current economic and social order. The economic and social order is reduced to a resource for facilitating technical innovation. This view is reinforced in the report’s discussion of the risks and trade-offs – for the environment, people, regions and sectors – that are associated with the pathways. For example, the novel technology of BECCS is recognised to be unproven and to pose substantial risks for environmental and social sustainability (IPCC, Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai and Pörtner2018a: 121), but it is considered manageable. It is only if BECCS and other NET options are poorly implemented that trade-offs will be required (IPCC, Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai and Pörtner2018a: 448). Similarly, risks associated with nuclear power (IPCC, Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai and Pörtner2018a: 461) are mentioned, but nothing is said about whether these should have any bearing on which pathways to choose. Thus, despite the overall stress on trade-offs in the report, there seems to be a strong belief that they will be manageable and will not constitute any substantial obstacles to implementing the pathways. This makes it possible for the IPCC to present risks and trade-offs, while at the same time not according them any implications for the suggested pathways, and thereby not politicising them.

SR15’s recommendations – the pathways – have a radical view of technology, putting great faith in future technological innovations, but are conservative in their view of societal change: they do not propose any transformation of the economic and social order. This is remarkable, since no connections are made between technological and social change. For decades, research in the social sciences has stressed the need for societal changes and social or socio-ecological transformation (Díaz et al., Reference Díaz, Settele and Brondizio2019), in the sense of fundamentally redirecting social organisation and human activities, including technology. SR15 on the other hand, when presenting possible pathways for limiting global warming, puts its hope in technological innovations isolated from social change. If the IPCC wants to be policy-relevant, it needs to adopt a wider and more comprehensive understanding of transformative change when developing pathways, and conceptualise society as more than just a set of conditions enabling or restricting technological innovation.

We thus find that the IPCC needs to incorporate more profound knowledge about transformative change into its assessments, including a deeper understanding of the mechanisms of social change on different spatial and temporal scales. A prerequisite to being influential is being policy-relevant, and in the post-Paris context this means presenting and assessing different options for how to initiate and facilitate transformative change without losing sight of social factors.

22.5 Achievements and Challenges

The IPCC is undoubtedly one of the most ambitious efforts ever undertaken to develop and communicate science to inform environmental policy globally. Among its greatest successes is its impressive mobilisation of the scientific community to allocate substantial resources – in the form of researchers’ time – to produce knowledge syntheses on an urgent issue. Determining whether this mobilisation has influenced policymaking, however, is more difficult. The IPCC has been surprisingly stable in its method of working: making systematic assessments and delivering – on a regular, if not frequent, basis – comprehensive reports that accurately summarise the current state of knowledge. The cornerstone of their work is not to be policy-prescriptive and thereby not to politicise the results. In practice, this means that the IPCC has primarily focused on developing and maintaining its epistemic authority, and only to a very limited extent has been interested in providing guidance to policymakers. However, this strategy is an insufficient way to proceed in the post-Paris political context.

There are several ways to further increase the relevance of the IPCC’s work to support national (and thus global) societal transformation. With the shift towards SOAs and the need for transformative change, the Panel should pay more attention to the socio-political aspects of these extremely demanding challenges, and adopt a deeper understanding of how politics (and society) works. For example, proposed technical innovations and solutions need to be embedded in realistic social conditions, otherwise the pathways will work on paper only. This demands better integration of social science in the IPCC’s assessments, which will be a challenge, because the Panel’s assessment work is not well-suited for assessing social science with its diverse epistemologies and methodologies. In the post-Paris political context, the Panel should focus more on regional and national contexts to be policy-relevant for national climate policies. This includes emphasising realistic policy options that consider regional and national variation, not least in relation to the development and implementation of technological solutions.

This does not imply that the IPCC needs to be policy-prescriptive in a narrow sense, telling governments what they should do. It is possible to assess studies on transformative change and present policy options – including evaluating their feasibility – without advocating one particular way forward. Social science has a long history of assessing policy development, analysing political experiments and exploring the conditions for transformative change, while not being prescriptive in the sense of giving firm advice. However, assessing such studies will require addressing controversial topics. To increase its policy relevance, the IPCC needs not only to outline possible policy options, but also to provide knowledge about their feasibility and viability. By utilising social science research, the IPCC can assess different options, which in fact means to give policy advice.

Overview

This chapter discusses the concept of ‘civic epistemology’ in relation to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the governance of climate change. Civic epistemology refers to ‘the institutionalised practices by which members of a given society test and deploy knowledge claims used as a basis for making collective choices’ (Jasanoff, Reference Jasanoff2005: 255). Differences in civic epistemologies seem to be directly related to how scientific climate knowledge, presented in IPCC assessment reports, relates to political decision-making at different scales – national, regional, global. The concept is especially rich because it enables a nuanced understanding of the role of IPCC assessments in national climate governance and in meeting the challenges of building more cosmopolitan climate expertise. Both of these aspects are important if emerging institutional arrangements that seek to govern global environmental change are to be understood. Through a critical review of the civic epistemology literature related to the IPCC, this chapter investigates how the cultural dimensions of the science–policy nexus, in different national and geopolitical contexts, conditions the legitimation and uptake of IPCC knowledge.

23.1 Introduction

Environmental governance regimes are enacted and legitimised by states and epistemic networks. The role of science in such regimes has been the subject of much debate, and many have considered knowledge consensus-building to be a crucial factor in shaping policy (Haas, Reference Haas1992). However, the history of the IPCC shows that the influence of climate change knowledge is not restricted to a linear idea of agreed-upon science directing policy (see Chapter 22). For example, scientific consensus often appears less relevant for policy than the persuasive powers of those speaking for science (Jasanoff, Reference Jasanoff, Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg2011). Understanding the science–policy interface therefore requires explaining how scientific claims gain policy-relevance in specific, sometimes divergent, ways across different countries (Agrawala, Reference Agrawala1998a; Hulme & Mahony, Reference Hulme and Mahony2010). At the national level, scientific consensus becomes one factor among many in the public deliberation of how to govern climate change or how to incorporate scientific claims into national or local policies (Hulme, Reference Hulme2009).

The IPCC has attempted with relative success to provide a common and reliable scientific knowledge base for international climate dialogues, but its credibility in the eyes of citizens and policymakers varies significantly from country to country. The multiplicity of modes of validation of the legitimacy of knowledge and the different forms of interaction between science and politics (Beck, Reference Beck2012) challenges the supposedly abstract universality of climate science – represented as the ‘view from nowhere’ (Borie et al., Reference Bony, Stevens, Held, Asrar and Hurrell2021) institutionally maintained by the IPCC. This poses several problems for understanding the IPCC’s role in global politics. Several authors have called for the building of a more ‘cosmopolitan climate expertise’ as a way to navigate these challenges (Hulme, Reference Hulme2010; Beck, Reference Beck2012; Raman & Pearce, Reference Raman and Pearce2020). Cosmopolitan knowledge has been defined as expertise which is comfortable with multiplicity and ambiguity, yet amenable to integration in a critical debate and a ‘reasoning together’ about a broader public good (Raman & Pearce, Reference Raman and Pearce2020: 3).

This chapter explores this challenge by using the concept of ‘civic epistemologies’ (Jasanoff, Reference Jasanoff, Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg2011), an idea which alludes to the historical, social and political dimensions of the different publicly accepted and institutionally sanctioned ways of performing trust and validating knowledge. We will explore the case of Global South nations – Brazil and India – to show how the reception and appropriation of knowledge organised by the IPCC occurs in contexts of scant public participation in the assessment and deliberation of science. We reiterate that the idea of civic epistemologies moves beyond the linear model of science for policy. We emphasise how this idea helps to understand the politics of climate knowledge not just in the Global North – for which there are many examples in the literature on the IPCC – but also in the Global South, even though there are fewer published examples available.

23.2 Civic Epistemologies and Climate Change

The concept of civic epistemologies emerged in science and technology studies (STS) and refers to ‘the institutionalised practices by which members of a given society test and deploy knowledge claims used as a basis for making collective choices’ (Jasanoff, Reference Jasanoff2005: 255). These practices include the following: institutionalised or explicit norms, protocols and systematic ways of producing and testing knowledge; tacit and implicit forms of deliberating; cultural predispositions and value judgements; and historical traditions that impinge upon the ways knowledge helps order social and institutional life. These epistemologies include ‘the styles of reasoning, modes of argumentation, standards of evidence, and norms of expertise that characterise public deliberation and political institutions’ (Miller, Reference Miller2008: 1896). They make it possible to analyse and understand the myriad ways publics and states arrive at agreements collectively regarding how knowledge can become a foundation for public decisions.

To illustrate how the idea of civic epistemologies can be applied to climate change, Jasanoff (Reference Jasanoff, Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg2011) compared three cases: the United States, Britain, and Germany. These nations share many cultural, technological and political characteristics, but have fundamentally divergent understandings of how climate science relates to climate policy. In the United States, a country ‘founded on common law’s adversary system’ (Jasanoff, Reference Jasanoff, Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg2011: 135), information is usually generated by parties with vested interests in the issues at hand and tested in public through overt confrontation, for example in courts. In opposition to the United States, ‘the British approach has historically been more consensual. Underlying Britain’s construction of public reason is a long-standing commitment to empirical observation and common-sense proofs’ (Jasanoff, Reference Jasanoff, Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg2011: 136). The trustworthiness of the individual expert is the focus of concern in Britain. In Germany, by contrast, it is believed that ‘building communally crafted expert rationales, capable of supporting a policy consensus, offers protection against a psychologically and politically debilitating risk consciousness … The capacity to form inclusive consensus positions functions as a sine qua non of stability and closure in German policy making’ (Jasanoff, 2011: 138, 140). Through this comparison, Jasanoff shows how practices of public reasoning and validation of knowledge are culturally situated. These examples demonstrate that scientific consensus does not move policy in the same directions in different countries; simple applications of the linear concept of the science–policy relationship are therefore questionable.

23.3 Brazil and India: Epistemic Sovereignty and Political Culture

One factor related to civic epistemologies that Jasanoff (Reference Jasanoff, Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg2011) did not explore concerns the geopolitical influences on the acceptance of the IPCC reports by different countries. Developed nations produce climate science that is well-represented in the IPCC’s scientific assessments. This is not the case with Global South countries, where issues related to a lack of ‘epistemic sovereignty’ over climate change knowledge (Mahony & Hulme, Reference Mahony and Hulme2018) might be far more important for influencing national policy than the existence of a ‘global consensus’.

Being represented in IPCC assessments through patterns of authorship (see Chapter 7) can begin to explain differential national uptake and trust in the assessments produced. Studies show that the United States, Britain, and Germany are the highest contributors to the IPCC in terms of the number of authors (El-Hinnawi, Reference El-Hinnawi2011). For nations like India and Brazil – albeit less present in terms of IPCC authorship – having large populations and extensive territory makes them central players in any global effort to curb climate change. One of the common characteristics of the civic epistemologies of these latter countries is that lower participation in the IPCC’s assessments – alongside other political and economic variables – may be associated with a reduced level of trust in the associated scientific conclusions and weaker engagement with the political agendas that emerge from them.

After the Fourth Assessment Report (2007) (AR4), climate change became an increasingly charged political issue in India and Brazil in different ways and with divergent consequences in terms of political action in these countries. A series of errors were discovered in the AR4 report, including one claim that Himalayan glaciers might completely disappear by 2035. This statement was challenged by the Government of India in the review process. Still, it remained in the final report and, three years later, circulated publicly in international media as a warning to the subcontinent about the perils of climate change and the need – for India as much as for the rest of the world – to act. The claim even appeared in a speech by John Kerry, then the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee chair, who argued that unchecked climate warming could reignite geopolitical tensions between India and Pakistan. The Indian Government responded by commissioning local glaciologists to conduct their own assessments of the prospects of Himalayan glaciers and by setting up what some dubbed an ‘Indian IPCC’ – the Indian Network for Climate Change Assessment (Mahony, Reference Mahony2014b). This example suggests that the absence of locally accepted knowledge on glaciers – or the presence of claims produced by an international assessment with little participation of Indian scientists and with potentially disruptive political consequences – drove the Indian state to produce counter-assessments to the IPCC. This relates both to the specificities of Indian civic epistemologies and to India’s specific political history under British colonisation.

In the case of Brazil, dissatisfaction with what some dubbed ‘Northern’ framings of climate change – most notably concerning deforestation and the role of the Amazon in the carbon cycle – caused controversy about the validity of scientific claims for directing national policy. Northern climate models used parameters that were considered inadequate by local scientists for simulating the effects of tropical forests on the carbon cycle. Among elected officials, the historical view that the Amazon region should be integrated into the national economy through economic exploitation was pervasive throughout the twentieth century. In that context, Brazilian Government officials felt that scientific assessments, such as those of the IPCC, directed deliberations over mitigation strategies towards the interests of global North countries (Lahsen, Reference Lahsen2009; Reference Lahsen and Pettinger2016). The Amazon historically occupies a sensitive spot in Brazil’s environmental policy, and fears over foreign interference have long roots (Monteiro et al., Reference Monteiro, Seixas and Vieira2014). Like elsewhere, local histories and cultures therefore condition how deliberation over technical expertise is applicable to environmental policy, specifically expertise produced outside the country in question. Brazilian civic epistemologies, like those in India, are related to longstanding concerns over sovereignty, albeit for different reasons.

The question of scientific credibility in the Brazilian case was not just about whether models and observations assessed by the IPCC were right or wrong. It was about fundamental inequities in national capacities to produce and frame knowledge (Miguel et al., Reference Miguel, Mahony and Monteiro2019). For the historically dominant Brazilian civic epistemology, local scientists working in national scientific infrastructures are seen as more trustworthy and credible than those from the global North, especially in politically sensitive issues like Amazon deforestation. The creation of a Brazilian Panel on Climate Change (BMPC) to produce systematic reviews of the scientific literature clearly reflects concerns of scientists and decision-makers about epistemic sovereignty (Duarte, Reference Duarte2019). This is in direct relation to Brazil’s role in international negotiations on greenhouse gas emissions and securitisation extended to territorial control.

One important shared idea of civic epistemologies emerging from Global North countries discussed by Jasanoff (Reference Jasanoff, Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg2011b) is that governmental decisions pertaining to climate change should be deemed acceptable by the public and directed by scientific principles. It can also be noted that these nations have well-established and well-funded scientific infrastructures, well-educated publics, and pathways of public deliberation about science. However, these political cultures and infrastructural conditions are radically different in the Global South. Issues of sovereignty, for countries like Brazil and India, play a role in different ways than in other places when technical decision-making is concerned; these issues become important elements of both scientific and political discussions related to climate change.

Civic epistemologies in Latin America for example – as part of broader political cultures – tend to be marked by top-down, non-participatory approaches to decision-making, which relate to the historical role of military dictatorships in the region. In addition, scientific systems and infrastructures were built across the continent in waves of centrally induced rapid modernisation; these mixed technocracy and the radical depreciation of local, popular forms of understanding reality. Such hierarchical patterns of deliberation are a legacy of authoritarianism and often persist intermingled with democratic processes. These structural elements weaken the inclusion of civil society in the assessment of government and expertise, and limit public participation in the decision-making processes related to climate governance. Lahsen (Reference Lahsen2009: 360), for example, argues that science and decision-making on matters of environmental risk in Brazil reflect a general attitude that assumes that ‘high-ranked decision-makers can be trusted to define national policy single-handedly, and that they better serve the common good than the processes of democratic politics’. In Brazil, a ‘technocratic civic epistemology’ keeps decision-making centralised in the hands of experts located in government bodies, which constantly alienates civil society from technically based political decisions.

In the Indian case, the emergence of civil society organisations after India’s independence – with objectives ranging from popularisation to the democratisation of science and related policy making – pressed against the Indian government’s resistance to public debate around scientific questions. The country also adopted a technocratic model of governance, directed at furthering the geopolitical interests of the state. At the same time, the memory of British colonialism in the country built a political culture focused on the search for sovereignty and the need to place political and scientific processes under the central control of the government (Agarwal et al., Reference Agarwal, Kalpana and Ravi1982; Mahony, Reference Mahony2014b).

Comparing the Indian and Brazilian cases with the UK, United States, and Germany, two factors emerge as distinct in their respective civic epistemologies. First, for nations of the Global North the issue of the authorship of scientific works assessed by the IPCC is not seen as a problem of legitimacy. In contrast, in many nations of the Global South, epistemic sovereignty is an important factor in the legitimacy of science in politics. Second, while the Global North frames climate science as an object of public scrutiny, Global South countries tend to frame climate science as a ‘science for the administration of the state’ and thus as part of the geopolitical process. These examples illustrate the different ‘epistemic geographies of climate change’ (Mahony & Hulme, Reference Mahony and Hulme2018) and the importance, for users and observers of the IPCC, of knowing about different civic epistemologies. Box 23.1 offers another case – that of Russia – which helps to illustrate the diversity of climate change civic epistemologies in non-Western nations.

Elena Rowe (Reference Rowe2012) discusses how internationally produced expert knowledge claims are taken up domestically in climate policy-making and debates in Russia. This provides an example of the national reception of international expert knowledge such as offered by the IPCC and ‘the role of experts in a quasi-democratic State’ (Rowe, Reference Rowe2012: 712). Rowe’s argument is that Russia’s successful engagement in international climate policy is likely to be based on appeals to the country’s political and economic interests and power aspirations, rather than on scientific knowledge that involves Russian authors or scientific institutions (Rowe, Reference Rowe2012). According to Rowe, Russian IPCC participants ‘did not seem to play a role in deliberative processes leading to key decision-making moments’ (Rowe, Reference Rowe2012: 713). However, ‘these experts were certainly called to legitimise decisions taken for other political and economic reasons’ and also to provide ‘input and guidance’ to Russian policy-makers in ‘navigating’ international forums and deliberative processes (Rowe, Reference Rowe2012: 713). The international scientific consensus is thus received in Russia as part of a ‘political package deal’ (Rowe, Reference Rowe2012: 723). Rowe concludes: ‘in a climate-politics “follower” State like Russia, the intervention of Russian experts was not needed to ensure that international science would diffuse into Russian policy circles’ (Rowe, Reference Rowe2012: 723).

23.4 Achievements and Challenges

In this chapter, we have shown the rich potential of the concept of civic epistemology to make sense of difficulties in enacting global climate governance through the IPCC. We have illustrated the need for further comparative research into how global environmental assessments result in robust policy impact across different countries, notably in non-Western ones. From our discussions about different civic epistemologies of climate change, a central question arises: Can the IPCC stimulate a more effective scientific and political arena for climate governance in the face of such globally diverse civic epistemologies?

Authors have suggested that the IPCC could prioritise a more cosmopolitan climate expertise (Raman & Pearce, Reference Raman and Pearce2020). The promise of cosmopolitan knowledge is to recognise the diversity and ambiguity of forms of knowledge-making and knowledge appropriation as a strength rather than a weakness for engaging with climate change. However, matters of epistemic sovereignty pose a more profound question related to inequality in the production of global climate science. How can the IPCC deal with the claim that climate science produced in developed countries does not fully represent underdeveloped nations in global climate governance? Global governance means dealing with global inequalities on several levels, two of the more important ones being unequal means of producing knowledge, and unequal access to economic and scientific resources that are essential to adaptation and mitigation of climate change. These inequalities condition how countries enter global climate debates and engage with policy development. They also influence the variety of civic epistemologies that condition how international scientific assessments, such as the IPCC, and global governance structures are accepted, deemed legitimate, and incorporated into national and local governance.

Overview

Research on the interaction between climate science and policy has pointed to the production of so-called ‘boundary objects’ as one way in which the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has influenced climate policymaking and broader climate discourses. By providing a common framework that enables interaction across social worlds, while still allowing more localised use by different groups of actors, such objects have been key in bringing together climate science and policy, in turn shaping the trajectory of both. This chapter reviews several concepts that have been analysed as boundary objects – such as the concept of climate sensitivity and the 2 °C and 1.5 °C targets – and explains how they have been productive of new science/policy relations. It also points to new challenges for the IPCC as climate policy development moves towards implementation and increases demand for more ‘solution-oriented’ knowledge.

24.1 Introduction

Much analysis of the IPCC – and indeed the IPCC’s traditional self-understanding – assumes that its influence and authority is premised on a strong demarcation between science and policy. In practice, however, the ways in which the IPCC may come to influence policy development or wider public perceptions of climate change is by making connections across these two spheres of science and policy (see Chapter 22). This presents a puzzle that requires solving in order to understand the IPCC’s influence: How can ideas about a clear separation between science and policy coexist with practices that constantly criss-cross or undermine the presumed boundary between them (cf. Sundqvist et al., Reference Sundqvist, Gasper, St and Clair2018)?

One way of attending to this puzzle is by analysing the specific objects that bring the IPCC and its contributing scientists into contact with policymakers, political activists or other groups of actors on different sides of the presumed boundaries. The notion of boundary object, originally proposed by Star and Griesemer (Reference Star and Griesemer1989; Star, Reference Star2010), describes some ‘thing’ – whether concrete or abstract – that holds together across different social worlds, allowing actors with different interests and views to act without the need for consensus on the object’s precise meaning. In studies of the IPCC and its relationship to publics and policymaking, the notion of boundary objects offers a way of focusing not simply on the construction of boundaries between social worlds or on how actors on one side of the boundary influence the other. Rather, the idea of boundary objects begins to explain how these actors produce new realities together. Analysing boundary objects is thus a way of going beyond general assertions about ‘co-production’ to study what exactly is produced at the intersection of science and policy, and with what effects.

This chapter employs the notion of boundary objects to show how the work of the IPCC has been closely intertwined with climate policy development, and how this interplay has shifted over time. It reviews existing studies of boundary objects that have been important for the IPCC’s influence on climate policy – and that have simultaneously worked to influence the IPCC’s own assessments and the wider trajectory of climate science. Two sets of such objects are identified. The first one represents features of the physical climate system, namely the concepts of Equilibrium Climate Sensitivity (ECS) and Global Warming Potentials (GWP). These objects illustrate the influence of the IPCC on the early features of the emerging international climate policy regime.

The other set of objects is a series of future-oriented limits, targets and scenarios, which have come to strongly structure both IPCC assessments and climate policy discourse in recent years. Most prominent among these are the 2 °C and 1.5 °C targets. These objects serve to connect the IPCC more closely to policy goals and explicitly normative considerations of desirable futures. They thereby increase the potential influence of IPCC knowledge on policy development. At the same time, they challenge the idea of a strong demarcation between science and policy on which the IPCC’s self-understanding has been premised. The concluding section discusses what this challenge might mean for the IPCC’s future role, and how the notion of boundary objects may help in understanding the influence of the IPCC more broadly.

24.2 Climate Sensitivity and Emission Equivalents: Epistemic and Governable Things

A key challenge in assessing climate change for policy purposes is how to align a scientific understanding of climate change – as a complex and insufficiently understood phenomenon – with the certainty and simplicity required for policymaking and governing. Knowledge about future climate change originates in complex models that are not easily understood outside the community of modellers (see Chapter 14). Research on the interaction between climate science and policy has pointed to the production of boundary objects as one way in which knowledge from climate models has become stabilised and taken up in policy processes.

Van der Sluijs and colleagues (Reference van der Sluijs, van Eijndhoven, Shackley and Wynne1998) analysed the concept of climate sensitivity as a case of a particularly stable boundary object. The IPCC defines climate sensitivity as ‘the change in the surface temperature in response to a change in the atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration or other radiative forcing’ (IPCC, 2021a). The concept emerged as a way of comparing and summarising model results in a way that enabled new forms of interaction between climate modellers, other scientific communities and policy actors. It was initially used as a heuristic tool for comparing different climate models, as modellers tested the sensitivity of models by comparing the temperature response of a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration. With the need to communicate model results to policymakers through assessment reports, the concept was deployed for a different purpose – as a shorthand for summarising the expected magnitude of climate change given continued carbon dioxide emissions.

In early climate assessments reports, the sensitivity of different models was summarised in an estimated range for climate sensitivity of between 1.5 °C and 4.5 °C for a doubling of atmospheric carbon dioxide (van der Sluijs et al., Reference van der Sluijs, van Eijndhoven, Shackley and Wynne1998: 299). When IPCC chair Bert Bolin delivered the IPCC’s statement to the first Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Berlin in 1995 (COP1), this estimate was among his key messages from the scientific community to the attending government representatives. In this way, the understanding of climate sensitivity as a measurable property of the physical climate system became a key reference point for climate policy discussions (van der Sluijs et al., Reference van der Sluijs, van Eijndhoven, Shackley and Wynne1998: 311).

Making the climate sensitivity relevant for policy actors in this way, impacted not only policy and public understandings of climate change. It also influenced the further scientific use of the concept, since it created a new demand for estimating and constraining climate sensitivity – not just as a metric for comparing models, but as an actually existing property of the climate system – in order to better inform policymaking (van der Sluijs et al., Reference van der Sluijs, van Eijndhoven, Shackley and Wynne1998).

Climate sensitivity originated from climate modelling, but was made relevant in new ways for policy communities. A different example from the IPCC’s early years illustrates that boundary objects may also originate from a specific policy need. When international discussion about how to govern climate change began in the late 1980s, some countries – the United States in particular – favoured a ‘comprehensive approach’ which dealt not only with carbon dioxide emissions, but also with other greenhouse gases (Shackley & Wynne, Reference Shackley and Wynne1997: 91). To address the need for a simple way of comparing the climate effects of different gases, the metric of Global Warming Potentials (GWP) was developed and published in the IPCC’s First Assessment Report (AR1). The GWP metric allows for a conversion of gases by calculating their ‘CO2-equivalent’ warming effect. The metric was later adopted by the UNFCCC to underpin quantified emission reduction commitments and international carbon trading (MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2009).

Among IPCC scientists, GWP was understood as an ambiguous and potentially problematic simplification (Shackley & Wynne, Reference Shackley and Wynne1997). For example, because the warming effects of greenhouse gases differ depending on their atmospheric lifetime, the choice of time-horizon for comparing them greatly influences the result.1 In AR1, GWPs for three different time horizons were presented ‘as candidates for discussion’ (quoted in Shackley & Wynne, Reference Shackley and Wynne1997: 91). Thus scientists saw the development of GWP as opening up a scientific area of inquiry – a discussion of how gases could usefully be compared in order to inform policy. Meanwhile, in the policy arena, the GWP metric was quickly adopted and put to use as an unambiguous fact of the climate system, as a basis for calculating exact amounts of allowable emissions, or the price at which carbon credits can be sold in international markets (MacKenzie, Reference MacKenzie2009).

Similar to the concept of climate sensitivity, the GWP metric became an object that stabilised and simplified complex and ambiguous knowledge. The objects thereby enabled interaction between different social worlds, while also generating new problems and practices both in scientific and policymaking circles. Crucially, however, although both objects were flexible enough to mean something rather different in policy discussions among climate modellers, they also maintained their distinct use in both arenas (van der Sluijs et al., Reference van der Sluijs, van Eijndhoven, Shackley and Wynne1998). In this way, the boundary objects that resulted from the interaction between the IPCC and policy communities in the organisation’s early years held a dual role – on the one hand enabling scientific knowledge-production about the climate system, and on the other hand underpinning new projects for governing it.

In the first role, these objects are similar to what Hans-Jörg Rheinberger (Reference Rheinberger1997) has labelled ‘epistemic things’. These are objects to be studied and worked on through the scientific process, which are characterised partly by the things not yet known and the questions they open up for study. In this sense, they embody an ‘irreducible vagueness’ (Rheinberger, Reference Rheinberger1997: 28). On the other hand, for policy purposes these objects take on a much more definitive character, representing something that is already known, and that can therefore be governed. They become objects or technologies of government, imbued with quantified precision and premised on a belief in scientific certainty and rigour (Porter, Reference Porter1995; cf. Asdal, Reference Asayama and Ishii2008).

This ‘tacking back-and-forth’ (Star, Reference Star2010: 601) between a ‘weakly structured common use’ and a ‘strongly structured individual-site use’ (Star and Griesemer, Reference Star and Griesemer1989: 393) is what makes climate sensitivity and GWP usefully understood as boundary objects. Their value lies in enabling the IPCC to interact with non-scientific actors through a common language, while at the same time meeting the requirements of each group necessary to uphold internal credibility and thereby the idea of a clear separation between science and policy.

24.3 Targets and Pathways: Dangerous Anthropogenic Objects?

The examples above show how boundary objects enabled the IPCC to influence the early stages of the international climate regime. As policy development has progressed, however, a different set of objects have emerged, which are directed less towards the physical climate system and more towards future policy action. Most prominent among these is the target to keep warming below 2 °C (and later the ambition of 1.5 °C), which has frequently been analysed as a boundary object (Randalls, Reference Randalls2010; Cointe et al., Reference Cointe, Ravon and Guérin2011; Lahn & Sundqvist, Reference Lahn and Sundqvist2017; Morseletto et al., Reference Morseletto, Biermann and Pattberg2017; Livingston & Rummukainen, Reference Livingston and Rummukainen2020).

The UNFCCC in 1992 established the goal to avoid ‘dangerous anthropogenic interference’ with the climate system, yet without specifying at which level climate change would be considered ‘dangerous’. Partly informed by the concept of climate sensitivity – which summarised the climate system in the metric of temperature rise – discussions about how to define ‘dangerous’ and ‘tolerable’ levels of climate change came to centre on a global temperature limit (Randalls, Reference Randalls2010). The EU adopted the 2 °C limit in 1996, and was its main proponent internationally until its formal adoption in the UNFCCC in 2010 (Morseletto et al., Reference Morseletto, Biermann and Pattberg2017).

The EU adopted the 2 °C target based on ‘trust in the underlying scientific content’ (Morseletto et al., Reference Morseletto, Biermann and Pattberg2017: 661), regarding the target as derived from scientific knowledge about climate impacts. In public discourse, it has also been widely represented as a ‘scientific’ target, often with implicit reference to the IPCC (Shaw, Reference Oppenheimer and Petsonk2013: 567). In the scientific literature, however, it is usually considered a political target, and has even been critiqued as not sufficiently scientifically grounded (e.g. Knutti et al., Reference Knorr Cetina2016). In other words, while the target provides an intuitive and simple metric capable of bringing together a range of actors, its precise meaning varies widely among them.

The IPCC has arguably played an important role in enabling and upholding this multiplicity of meaning. Although IPCC reports have never endorsed any specific temperature limit as a marker of ‘dangerous’ climate change, they have increasingly been framed around temperature increase as a unifying metric. This is seen, for example, in the so-called ‘Reasons for Concern’ framework, which was introduced in the Third Assessment Report (AR3) and lent credibility to the idea of considering climate impacts in relation to global temperature rise (Mahony, Reference Mahony2015; Asayama, Reference Asayama2021; see Chapter 21).

In this way, the 2 °C target became established as a unifying object that is ‘neither scientific nor political in essence, but instead co-produced by both’ (Livingston & Rummukainen, Reference Livingston and Rummukainen2020: 10). Its influence on climate policy discourse has been such that even criticism of it came to be framed in the same terms. Thus, developing countries or activists arguing that 2 °C represents an ‘unsafe’ level of warming did not criticise the framing of IPCC reports around temperature targets. Rather, they asked for alternative targets such as 1 °C or 1.5 °C to be included for scientific analysis and policy debate, both in IPCC assessments and in UNFCCC negotiations (Cointe et al., Reference Cointe, Ravon and Guérin2011: 18; Lahn, Reference Lahn2021: 21; for more on the 1.5 °C target, see Guillemot, Reference Guillemot, Aykut, Foyer and Morena2017; Livingston & Rummukainen, Reference Livingston and Rummukainen2020).

The formal adoption of 2 °C in 2010, and the further inclusion of 1.5 °C as an additional ambition in the Paris Agreement, marks a (provisional) end to discussions about how to define ‘dangerous anthropogenic interference’. Attention has thereby shifted from overall goals towards scenarios, pathways and technologies that may achieve those goals. Bringing together policy goals and scientific knowledge in a common representation of futures to be achieved or avoided, such as pathways and scenarios, may well be seen as new boundary objects in the making (cf. Garb et al., Reference Garb, Pulver and VanDeveer2008).

Examples of such new boundary objects are the Representative Concentration Pathways and the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways, which have been produced for, but organised independently from, the IPCC (see Chapter 15). The goal of these new scenarios is explicitly to provide a common framework through which different groups within the IPCC can work together, thus producing an ‘epistemic thing’ that links (for example) climate modelling, integrated assessment modelling and research on climate impacts. At the same time, as Beck and Mahony (Reference Beck and Mahony2018a, Reference Beck and Mahony2018b) have shown, the new pathways also bring new governable objects into being. By legitimising new technologies such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS), they serve to make some mitigation measures ‘politically legible and actionable’ while potentially obscuring others (Beck & Mahony, Reference Beck and Mahony2018a: 8).

This double character makes the new pathways similar to the boundary objects from the IPCC’s early years, as described earlier. However, in contrast to concepts such as climate sensitivity – which came to be seen as a feature of the physical climate system – the future-oriented and goal-directed character of the pathways make them explicitly ‘anthropogenic’ in origin. They are directly implicated in the ‘world-making’ work of rendering certain futures more or less thinkable or desirable. For this reason they challenge any notion of a clear-cut divide between scientific fact and political or societal values – thus ‘raising new questions about the neutrality of climate science’ (Beck & Mahony, Reference Beck and Mahony2018a).

Following international agreement on how to define ‘dangerous anthropogenic interference’, then, a new class of ‘dangerous anthropogenic objects’ are rising to prominence in the work of the IPCC. What makes them ‘dangerous’ to the IPCC is not so much that they make scientists engage more explicitly with policy goals in a ‘solution-oriented’ mode. Rather, the danger lies in how they challenge the IPCC’s self-understanding based on a strong demarcation between science and policy, thus potentially forcing a reassessment of the IPCC’s role in relation to policy development. This is illustrated in the controversy that arose around the Bali Box (see Box 24.1).

In the Fourth Assessment Report (2007) (AR4), the IPCC presented a box quantifying the emission reductions that would be required by developed countries as a group in order to achieve the 2 °C target. The numbers became key to discussions about equitable effort-sharing between developed and developing countries during the UNFCCC negotiations in Bali, and was subsequently dubbed the ‘Bali Box’ (Lahn & Sundqvist, Reference Lahn and Sundqvist2017).

In their analysis of the Bali Box as a boundary object, Lahn and Sundqvist (Reference Lahn and Sundqvist2017) show that the numbers of the box initially enabled a relatively broad group of actors to come together around a common understanding of effort-sharing. However, the IPCC scientists who developed the numbers later published an analysis that also quantified emission reductions required by developing countries. At this point, the numbers were contested from an equity perspective and the Bali Box became a source of controversy both in UNFCCC negotiations and in the scientific literature.

The disagreement that ensued can be seen as a form of ‘ontological controversy’, as described in Chapter 16 – a disagreement over the underlying values and presuppositions of scientific findings. The result was that the Bali Box – initially successful in bringing together actors around a shared understanding of a difficult issue – did not retain its authority when the interdependencies of science and policy became exposed. It thus eventually failed to do the coordinating work of a successful boundary object.

24.4 Achievements and Challenges

As the examples above have shown, the IPCC’s influence has in part been enabled by the establishment of boundary objects that allow different groups of actors to interact while maintaining their distinct identities and commitments. The notion of boundary objects, however, also points to a broader understanding of ‘influence’ than a simple one-way transmission of scientific knowledge to policymaking. Indeed, the objects described in this chapter produce new realities in both spheres, simultaneously raising new scientific questions and enabling new forms of governing.

An important aspect of several boundary objects reviewed in this chapter is that they have allowed for close interaction and mutual influence between science and policy, while still permitting an understanding of the two spheres as clearly separated. With new demands being placed on the IPCC for solutions and roadmaps for achieving societal goals, this may no longer be the case. Rather than upholding the idea of separation, new boundary objects emerging in the post-Paris terrain of climate science and policy – such as pathways towards global or national targets – may instead prompt recognition of how climate science and policy are intricately interlinked. This presents an obvious challenge to the IPCC’s traditional self-understanding (Hermansen et al., Reference Hermansen, Lahn, Sundqvist and Øye2021).

Beck and Mahony (Reference Beck and Mahony2018b) have suggested that the IPCC could deal with this challenge by substituting its self-understanding as ‘neutral arbiter’ with the goal of producing ‘responsible assessment’. This would include ‘opening up to a broader and more diverse set of metrics, criteria and frameworks’ for assessing responses to climate change (Beck & Mahony, Reference Beck and Mahony2018b: 6). Analysing the IPCC from the perspective of boundary objects shows that influence and relevance is achieved through mutual adjustment and the development of shared meaning across various groups of actors. However, as the controversy around the Bali Box illustrates, such achievements stand in danger of being eroded if the interdependencies between science and policy are denied or ignored. This suggests that the IPCC should be more reflexive about how it helps bring about new science–policy realities. It should therefore think through what kinds of objects might result from a new and more ‘responsible’ assessment mode in the future.

Overview

This chapter reviews the types, use, production, accessibility and efficacy of data visuals contained in the assessments and special reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), drawing upon available published literature. Visuals of different types are key to the communication of IPCC assessments. They have been subject to academic interest among social and cognitive scientists. Furthermore, wider societal interest in the IPCC has increased, especially since the publication of its Fifth Assessment Report (AR5). In response, the IPCC has revisited its approach to communication including visuals, which has resulted in a greater professionalisation of its visualisations – involving information designers and cognitive scientists – and in new forms of co-production between authors and users.

25.1 Introduction

IPCC visuals1 are integral to the communication of IPCC assessments, and have been the subject of academic research since the late 1990s. Visuals provide diverse representations of evidence, primarily in the form of graphs, maps, diagrams, tables, and more recently, icons and infographics, such as those in the Technical Summary of the IPCC’s Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate (IPCC, Reference rtner, Roberts and Masson-Delmotte2019f). The focus of research on this topic has broadly addressed four questions:

What types of visuals are used in reports, and how?

How have they changed over time and why?

How are visuals produced?

How well do they convey the messages they intend to, and how well are they understood by different audiences?

As societal interest in the work of the IPCC has expanded, the accessibility of IPCC communications has been scrutinised in more detail (see Chapter 26). Studies by social and cognitive scientists have explored the effectiveness of IPCC visuals and how they are interpreted and understood by a variety of users, including policymakers and non-experts. This chapter explores these aspects in detail, with reflections on how these intersect with the nature, role and authority of the IPCC and on its response to calls for change in its communication processes.

25.2 Types of IPCC Visuals

IPCC visuals are provided to communicate data and information, consonant with the tradition in scientific literature of illustrating specific evidence through visuals. Visuals are bespoke to Summary for Policymakers (SPM) reports, but typically evolve from figures contained in Working Group (WG) chapters or in Technical Summaries, which in turn may have their origins in published literature. The bespoke nature of SPM visuals reflects the purpose and format of IPCC assessments. Although visuals are embedded within the written narrative of the reports, there is a paucity of research exploring how readers use text and visuals in isolation or in relation to each other, and the effectiveness of these approaches.

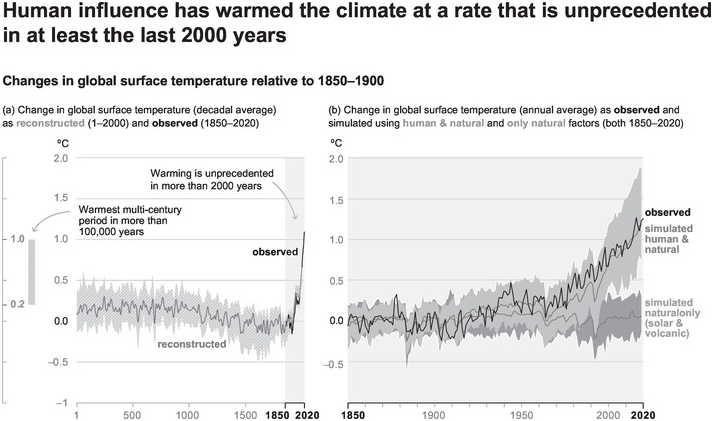

There is wide variation in the type and content of visuals used within and between reports and over time. Box 25.1 shows an example for the changing visualisation of observed global temperature between the First Assessment Report (AR1) in 1990 and the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) in 2021. These differences are related in part to scientific and social advances – knowledge, modelling capacity, understanding of uncertainty, data availability – and partly to representational choices (discussed later). The visuals provide representations of a range of topics – for example, observational data (in time series format or geographically referenced), projections, processes, comparisons of change, model outputs, risk assessments – drawing upon a variety and diversity of data sources as well as expert judgement. Multiple aspects of climate change are often represented in a visual – for example the ‘burning embers’ diagram, discussed later – reflecting the need to synthesise information as part of an assessment. The media through which visuals in IPCC reports are disseminated has evolved over time – from print-only copies of the earlier assessments to more recent digital online availability supported by multimedia (for example WGI’s short video of its AR6 contribution, FAQs, an Interactive Atlas, Regional Fact Sheets, Data Access, and Outreach Materials).

These two visuals (Figures 25.1 and 25.2) – with original captions included – drawn from IPCC SPM reports in AR1 (1990) [top panel] and in AR6 (2021) [lower panel], show the evolution in the way IPCC has depicted observed trends in global temperature. The visual from the AR6 WGI SPM denotes the causes, as well as the changes, of recent warming. It uses titles and annotations to help guide the reader, and includes a detailed caption about the data presented. Reproduced here from AR1 WGI (IPCC, Reference Houghton, Jenkins and Ephraums1990a: SPM, p. 23, original greyscale), and AR6 WGI (IPCC, Reference Masson-Delmotte, Zhai and Pirani2021a: SPM, p. 6, original in colour).

Figure 25.1 Reproduction of Figure 11, plus original caption, from the IPCC SPM for AR1 WGI in 1990.

Figure 25.2 Reproduction of Figure SPM.1, plus original caption, from the IPCC SPM for AR6 WGI in 2021.

25.3 Presentation and Use of Visuals

The varied foci and key messages contained in visuals, as well as the need to convey these to multiple audiences effectively, can be challenging for their production. Doyle (Reference Doyle2011) and Nocke (Reference Nocke, Schneider and Nocke2014) mention that the production and presentation of visuals in the first four of the IPCC’s assessment reports were influenced by a focus at the time on datasets capturing global observations to monitor and project global change, facilitated by the emergence of institutions with a global remit. Observational data in early IPCC visuals is often presented in graphs showing temporal change on one axis, with environmental and ecological variation depicted as linear change, its complexity thus constrained by the representational medium used (see Doyle, Reference Doyle2011).

In maps, variation in ecological processes is expressed in spatial terms. These have until recently lacked regional specificities (Doyle, Reference Doyle2011; Nocke, Reference Nocke, Schneider and Nocke2014) and have been critiqued for removing the local relevance of change and connection to a sense of place. Temporal change was also more challenging to present in maps of earlier IPCC reports. It has been argued that the use of these formats denotes the power of western cartography in terms of which features are represented and how (see discussion in Doyle, Reference Doyle2011). To enhance the accessibility of visuals for wider audiences, choices were made in regard to presentation, style and aesthetics (Doyle, Reference Doyle2011: 57). For example, the graphs in the AR3 Synthesis Report included a wider range of colours; this was accompanied by specific choices for typeface and borders to draw attention to specific content.

Static visuals may be useful for presentational purposes, although these can be perceived as being simplistic (Nocke, Reference Nocke, Schneider and Nocke2014). More in-depth and comprehensive exploration of data can be enabled through interactive options, made possible through recent digital advances. Conversely, interactive data platforms can be challenging for users if they lack knowledge of how to navigate the complex datasets and portals available (Hewitson, et al., Reference Hewitson, Waagsaether, Wohland, Kloppers and Kara2017). In recognition of the potential for interactive data visual products displaying tailored information, the AR6 WGI assessment developed an Interactive Atlas (IPCC, 2021d). This enabled users to customise representations of regional information and access the underpinning data.

Studies have highlighted how the representation of visuals in IPCC reports is affected by the complex relationships between those who create, review, shape and use such visuals. Visuals may evolve over time, acquiring diverse social and political significance. One well-known visual that was produced to represent and convey the likelihood of future risk and uncertainty is the ‘burning embers’ diagram (see Figure 25.3; see also Chapter 21). Mahony’s (Reference Mahony2015) study of the origins and development of the visual examines how its representation of thresholds at which climate change may become dangerous was revisited, debated and embraced/rejected, through processes underpinned by a range of interpretations and ‘political objectives’ (Mahony, Reference Mahony2015: 153). These were, he concludes, indicative of tensions and debates among different knowledges and practices of sense-making. Recognising these differences opens up opportunities for further understanding the iterative creation of visual forms of knowledge through multiple disciplinary perspectives. Zommers et al. (Reference Zommers, Marbaix and Fischlin2020) note how lessons learnt from debates about the burning embers diagram have translated into more formalised processes – protocols, standardised metrics for risk thresholds – in recent IPCC reports that aim to increase transparency. Another contested visual is ‘the hockey-stick’ graph in AR3, showing a significant rise in temperatures in the twentieth century in the context of the last thousand years. Its visual presentation and the statistical methods used to represent the data (Walsh, Reference Walsh2010) received criticism, in part fomented by the rise of internet communications (Zorita, Reference Zorita2019).

Figure 25.3 Risks associated with Reasons For Concern at a global scale are shown for increasing levels of climate change.

Research on visuals has mainly focused on the physical science of climate change, typically reports produced by WGI. As a point of departure, Wardekker and Lorenz (Reference Wardekker and Lorenz2019) evaluated the content and framing of visuals in WGII from AR1 to AR5. Their work shows that the majority of the over 700 visuals examined focus on impacts (problems), but few on solutions and adaptation. The authors point to the importance of understanding how visual information is framed (presented), given its influence on how information is interpreted, perceived and used in decision-making. Wardekker and Lorenz (Reference Wardekker and Lorenz2019) also acknowledge the potential for debating the visual framing of information in internal IPCC processes. Such debates can be highly politicised with competing interests at stake. The aforementioned authors note how opportunities may arise for tailoring visuals – for example more specific national and regional foci in regional chapters or increased interaction across drafting teams earlier in the SPM process – and for learning from the use of visuals in other contexts, for example on climate adaptation by national agencies.

25.4 Accessibility and Efficacy of Visuals