Introduction

Recent immigrants to Canada are faced with a new and unfamiliar health system (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Penning and Schimmele2005; Reitmanova and Gustafson, Reference Reitmanova and Gustafson2008; Guruge and Humphreys, Reference Guruge and Humphreys2009). The transitional experiences of new immigrants and their families, requires that services within receiving communities be adaptive to their circumstances (Isaacs, Reference Isaacs2010; Lebrun and Dubay, Reference Lebrun and Dubay2010). In Canada, federally funded settlement programmes exist to assist new immigrants during their early transition years. Selected funding and programmes target individuals and families with refugee status, representing almost 10% of immigrants to Canada. (Kenney, Reference Kenney2009). The majority of immigrants will have different experiences of support during their first two years in Canada, language training and help with job searches for example (Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), 2011). Access is limited when programmes intended to assist immigrant families are over extended, or when families themselves are uninformed about the services available to them (Canadian Council on Social Development, 2000). To meet a family's health needs, the majority of immigrants are directed to use local health and social services available to the general public.

Atlantic Canada, with its relatively small immigrant population compared with other parts of the country, has a unique set of challenges. Locations of low immigrant density may have fewer services tailored to address the specific needs of new populations (Berdahl et al., Reference Berdahl, Kirby and Stone2007; Pitkin Derose et al., Reference Pitkin Derose, Escarce and Lurie2007). Providers within the available generic services, in attempting to meet the demands and needs of long-standing residents, may not always be attuned to the specific concerns of immigrants (Casey et al., Reference Casey, Blewett and Call2004; Asanin and Wilson, Reference Asanin and Wilson2008). Opportunities for developing these competencies can be missed simply through lack of exposure (Burcham, Reference Burcham2002; Campinha-Bacote, Reference Campinha-Bacote2003).

Cultural competence is a set of ‘congruent behaviours, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, agency, or among professionals that enables the system or professionals to work effectively in cross-cultural situations’ (Cross et al., Reference Cross, Bazron, Dennis and Isaacs1989: 7). In any service system still maturing in its capacities for addressing immigrant needs, sharing the resources and competencies of others in dealing with new Canadians is particularly important – this becomes a prerequisite of a culturally competent system. ‘The network model is based on the premise that collaboration and cultural competence are each essential to provide appropriate services to racial/ethnic minorities and that these concepts are related’ (Whitaker et al., Reference Whitaker, Baker and Pratt2007: 192).

The purpose of this paper is to describe how a network of community-based services collectively addressed the primary health care (PHC) needs of recent immigrant families with young children and how this was supported by a subset of broker organizations. Broker organizations are organizations that help to move things – information, resources, and people – between and across inter-organizational network members (Butts, Reference Butts2008). Broker organizations can also connect services to resources outside of their immediate services sector (Gould and Fernandez, Reference Gould and Fernandez1989; Cross and Prusak, Reference Cross and Prusak2002). The role of broker is a significant concept in this paper given that access to needed services for recent immigrant families can require negotiating with a variety of different providers.

This case study focused on the network of community-based service organizations providing services to recent immigrant families with young children, newborn to six years of age, living in a geographically bounded neighbourhood of a mid-sized urban centre in Atlantic Canada. The neighbourhood was identified because of the concentration of immigrants living in this area compared with the rest of the municipality. The three research propositions addressed in this paper are as follows:

• Organizations designated to provide PHC services are part of a network of community service organizations that interact with one another when addressing the PHC needs of children of recent immigrants.

• Brokers exist within the network of organizations that assist in connecting services to one another in order to address the PHC needs of immigrant children.

• How organizations interact with one another, and the brokers that enable these interactions, will differ depending on the type of PHC need being addressed.

PHC services in Canada are inclusive of primary care (PC) and public health (PH) programmes and services (Meagher-Stewart et al., Reference Meagher-Stewart, Martin-Misener and Valaitis2009). PC services are often provided by private practice, fee-for-service physicians paid through government insurance programmes, or by salaried health professionals working as part of multidisciplinary teams in settings such as community health centres (CHC). PH programmes are government-administered services, covering aspects of health promotion and disease prevention within different community venues. The Alma Ata Declaration (World Health Organization (WHO), 1978) and subsequent related documents that encourage inter-sectoral collaboration to address health (Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), 2007; WHO, 2008) are a natural response to how families recognize and address their own health needs (Van Olmen et al., Reference Van Olmen, Criel, Van Damme, Marchal, Van Belle, Van Dormael, Hoerée, Pirard and Kegels2010). This broader perspective that is inclusive of different kinds of supporting services, defines a PHC ‘system’ (WHO, 2008).

The PHC needs considered in this study were child nutrition, gastro-intestinal (GI) illness, and child growth and development. These PHC issues were selected because of their relevance to young children; GI illness was felt to be a potentially under-recognized concern for immigrant children arriving from countries with high-disease prevalence including chronic parasitic infections that can also affect nutritional status (Geltman et al., Reference Geltman, Radin, Zhang, Cochran and Meyers2001). Also considered were general health and a category for other concerns.

Method

Two methods of data collection were used to capture information for this case study. This follows Yin's framework for case study design, wherein either or both qualitative and quantitative approaches can be used to create different sources of data related to pre-defined study propositions (Yin, Reference Yin2003). Data collection methods used were (1) an on-line social network survey asking representatives from different organizations about their relationships with other services in the study neighbourhood and (2) key informant interviews conducted with service providers working within the service community.

Sample selection

Sample selection for the study survey followed a whole network approach used in social network analysis (SNA). In this approach all network members are targeted for inclusion (Provan et al., Reference Provan, Fish and Sydow2007). Criteria are used for setting the boundaries of the network and defining networking membership. In this case, a network member was defined as an organization serving the neighbourhood of interest and providing services to recent immigrants and/or to families with young children, newborn to six years of age. Using these criteria, a list of organizations was created starting with organizations attending a health fair for immigrants in 2009. Organizations were added to this list from a comprehensive reference catalogue of community-based services managed by a local agency. A staff member from the study neighbourhood's community health board, and the health coordinator for a local immigrant settlement service both reviewed the list. They were asked to delete or add services based on the network membership criteria. These decisions were vetted by the researcher through a review of each organization's mandates, and during initial contacts with organization representatives.

Twenty-seven organizations were identified in this way for recruitment as survey participants. In addition, four proxy organizations representing groups of organizations – family doctors, day cares, walk-in clinics, and cultural associations – were added to the organization list. It was decidedly difficult to target specific organizations or practices from these groups given that families from the neighbourhood often travelled across the city for these services. The final list of 31 organizations constituted the study network, and became the list of services appearing in the network survey instrument. Organizations were classified under the following service sectors – PH, PC, immigrant services, family outreach and drop-ins, child and legal services, family counselling, and an ‘other’ category involving services such as housing, food banks, cultural associations, and a public library.

Key informants for interviews were selected starting with recommendations from other researchers familiar with the local services offered to immigrants and young families. Other key informants were identified from the organization list and as recommended by the earliest informants interviewed. Selection was purposeful to ensure variation in the types of professions interviewed, and representation of different service types – PH, PC, settlement services and non-government organizations.

Organizations selected for either arm of the study were recruited through e-mailed invitation and follow-up phone calls to organization directors or managers. The director or manager either participated themselves or else nominated one or two designates with the criteria that designates be able to respond in an informed way concerning their organization's activities and partnerships with other agencies.

Data collection and analysis

SNA survey

The survey instrument was developed using the format and types of questions applied in previous service delivery network surveys (Kwait et al., Reference Kwait, Valente and Celentano2001; Provan et al., Reference Provan, Veazie, Staten and Teufel-Shone2005). The survey was tested with nursing students for user readability and accessibility, and for face and content validity with four epidemiology colleagues. The instrument was then assessed for relevancy and acceptability by members of two local agencies associated with the study network. The reliability of data summaries was established after running repeated trials of the software programme used to create these from the survey responses.

The survey was made available on-line, took ∼15–20 min to complete, and consisted of two domains. The first domain addressed attributes of the responding organization, for example, type of organization, type of population served, and types of services offered. The second section listed the 31 network organizations and asked respondents a series of questions about their relationships with each organization on the list. Respondents were asked, ‘How frequently are you or your co-workers in contact with each organization?’ Respondents answered using a 5-point Likert scale. They were also asked, ‘Do you or your co-workers work with this organization concerning young immigrant children and [ ]?’ Substituting [ ] with the selected PHC needs GI illness, nutrition, growth and development, general health, and other concerns. Responses to this latter series of questions were coded as binomial (0,1).

All analyses of the survey data were conducted using UCINET (Borgatti et al., Reference Borgatti, Everett and Freeman2002) and NetDraw (Borgatti, Reference Borgatti2002), softwares developed to support SNA applications. The field of SNA considers the structure of the social environment, and has developed a series of methods for measuring and describing ‘patterns or regularities in relationships among interacting units’ (Wasserman and Faust, Reference Wasserman and Faust1994: 3). The SNA methods used in this study were largely descriptive, using sociograms (network maps) and tables to display relationships among organizations. Network density was calculated as a measure of cohesiveness among network members, that is, how often network members connected with one another in response to different questions. Density is equal to the total number of connections observed, divided by the total number of possible connections among network members (Scott, Reference Scott2006: 71).

Directed betweenness centrality, a value calculated for each network member, allowed for the identification of organizations that acted as brokers, linking network members to one another. Directed betweenness centrality scores were calculated based on how often each member fell along the shortest path (number of connections) between all other members of the network (Scott, Reference Scott2006: 86). The paths were directional (one way).

Key informant interviews

One-on-one interviews with key informants ran from 45 to 90 min. Interviews took place in the respondent's work setting, or as necessary by phone at the convenience of the respondent. An interview guide was used, which included questions relating to types of roles played by different organizations in the network. All interviews were transcribed verbatim and transcripts imported into NVivo 8 for analysis (QSR, 2007). A technique of constant comparative analysis was applied, starting with original propositions to categorize and code data; these were then reorganized, regrouped, and cross-referenced as new sets of data became apparent, and /or prominent themes began to take hold (Crabtree and Miller, Reference Crabtree and Miller1999).

Triangulation of results

Rigour in this study was accomplished through triangulation. Both data sources were analysed independently, and then results brought together to compare and examine within and between themselves for convergence or divergence of meaning (Miller and Crabtree, Reference Miller and Crabtree1999). Interview data were used to help explain survey findings. As results were compared and as questions arose, further examination of the original data was prompted, continuing the process of constant comparison. Different interpretations were considered for divergent findings until satisfactory explanations and continuity of the discourse was achieved. The qualitative interviews offered context for the relationships observed in the survey results, and interpretation behind the role of broker.

Ethics

Ethics approval was received for this research from the ethics boards of the sponsoring university, local health authorities, and Health Canada. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Results

Context of the case

The study neighbourhood included two adjacent city planning zones, with immigrants represented as visible segments of the population in both (15.3% of zone A and 8.9% of zone B). Visible minority groups within the neighbourhood, presented in order of magnitude, were Arab and West Asian, African descent, South Asian, and Chinese (Statistics Canada, 2007).

Twenty-one of the 27 organizations approached participated in the SNA survey, a response rate of 78%. Fourteen key informants of 19 individuals asked to participate (74%) were interviewed, 12 in person and two by phone. Those interviewed included a mix of professionals – one NGO administrator, four social workers (one hospital based, one outreach and two drop-in centres), three settlement workers (two different organizations), four nurses (three from PH and one from PC), and two PC physicians.

On the basis of both sources of data, organizations participating in the study provided a broad range of services for families with young children. These included health screening and assessment, case management, advocacy, family outreach services, group support and education, medical treatment, interpreter support and language training, and other modes of family support and counselling. Services addressed a broad range of issues – child growth and development, infectious diseases, nutrition, literacy, housing, legal and financial needs, immigration settlement adjustment, mental health, and other health concerns.

Network cohesiveness and the brokers that support this

Tables 1 and 2 present the network density and directed betweenness centrality scores for the network and organizations in this case. In relation to PHC needs, the cohesiveness of the network (Table 1) was highest when dealing with General Health concerns (density score of 0.16; 95% CIs 0.12, 0.19) and lowest for GI illness (density score, 0.03; 95% CIs 0.01, 0.04). Non-overlapping confidence intervals (CIs) demonstrated a statistically significant difference between the general health density score and all other density scores. Of the organizations listed in Table 2, PH_09, a PH programme, scored the highest as a network broker when dealing with General Health (centrality 102.30), while PH_06, another PH programme, acted as the central broker for GI illness (centrality 71.50).

Table 1 Network densityFootnote a and number of network ties given different reasons for connecting

PHC = primary health care; GI = gastro-intestinal; SD = standard deviation; SE = standard error; CI = confidence interval.

a The density is the total number of ties (connections) divided by the total number of possible ties among network members.

b Average density calculated for valued data (5-point Likert scale response).

95% CI = density score ± 1.96 × SE.

Table 2 Directed betweenness centrality scores for organizations in regular contact, or when working with others concerning the PHC needs of immigrant children (by service sector)

PHC = primary health care; GI = gastro-intestinal; SD = standard deviation.

aNon-responding organizations. 0's are expected since responses are needed to show path direction through these nodes.

Brokers supporting regular contact among network members

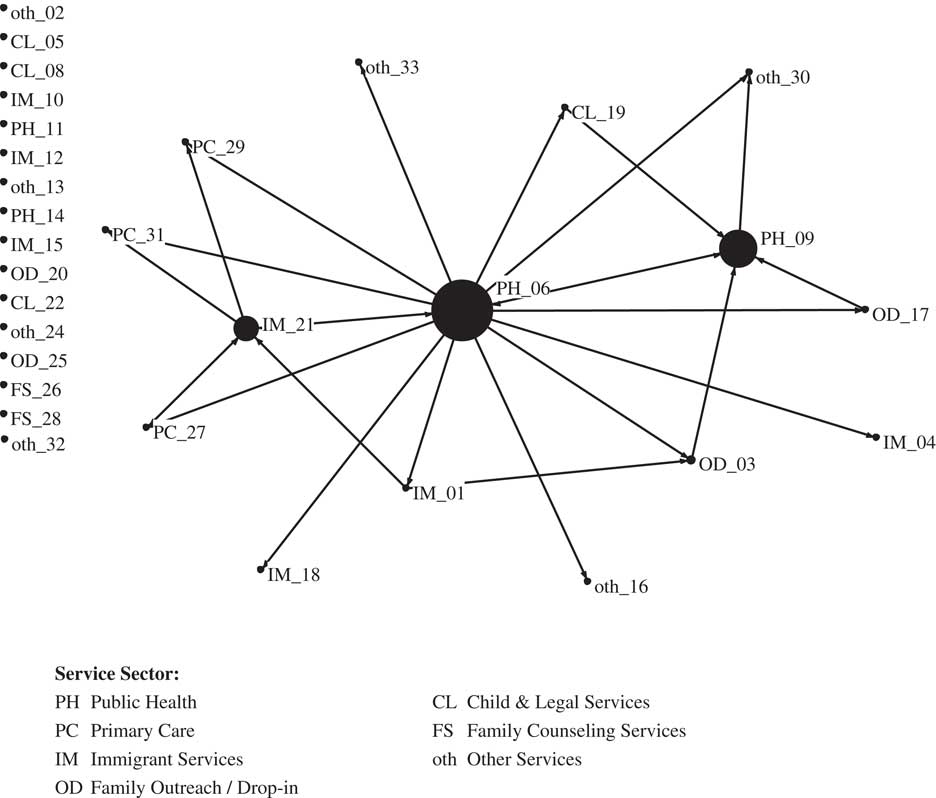

Figure 1 represents responses to the survey question, ‘How frequently are you in contact with each of the following organizations?’, and in this case maps relationships among organizations where contacts occurred more than once a month. Relationships are represented by lines between nodes (circles); the nodes represent the organizations. The size of each node is a representation of directed betweenness centrality, and a relative indication of how each organization functions as a broker within the network. On the basis of node size, one of the settlement services, IM_21, appears as the main broker in this regular contact network. Other minor brokers, a child and legal service (CL_19) and a PH service (PH_09), focused on children's needs rather than immigrants specifically, however, as demonstrated in the network map, each worked with different sets of organizations directly.

Figure 1 Regular contact network. Relative betweenness centrality (directed) scores are represented by node size. Contacts, represented by connecting lines, are considered regular if frequency of contacts is greater than once per month. (How frequently are you in contact with each of the following organizations?)

From interview data, organizations most noted for their engagement in the needs of immigrant families were settlement services, family drop-in centres, PH, and a CHC. Settlement service IM_21 was the most frequently mentioned organization, acknowledged by interviewees as a lead broker around the needs of immigrants. This organization acted primarily as an intermediary with Canadian immigration authorities for arriving refugees and other high need immigrants, and facilitated the integration of immigrants into the local society. Their role was to ‘network’ on behalf of immigrants and to connect families to services that could meet their needs:

… It is important for people to get connected to everything possible… So we help our clients register their children to school. We help them access health care, whether it's the primary health care through family doctors …even by accompaniment, going to the children's hospital.

(Settlement worker 011)

Different brokers for different PHC needs

Reduced network cohesiveness around selected PHC needs as measured by density scores in Table 1, was paralleled with a visible increase in network fragmentation (fewer ties and fewer engaged members) as illustrated in Figures 2 to 6. Figure 2 portrays the relationships among network members when addressing general health concerns. Public health (PH_09 and PH_06) and settlement services (IM_21 and IM_01) are all placed in relatively strong positions as brokers concerning this issue. IM_01 was not previously identified as a broker in the regular contact network. IM_01 was, however, described in interviews as a source of referral for other organizations dealing with health and related concerns for immigrant families attached to the school system.

Whatever the family asks about (we) will try to find out. So if they're looking for a job, we would try to access employment services; if they're looking for a house, we would try to get information about housing.

(Settlement worker 19)

Figure 2 General health concerns network

As stated by informants, this school-based programme had a unique opportunity for connecting with recent immigrant families. Settlement workers were available to the entire family, not just to the children in school. Principals of schools actively identified new arrivals and referred them to settlement staff. Most immigrants with children attending school did not have connections to other settlement services: ‘… they are people that are getting care mostly on their own, that are using the health care system as it is, with not really having immigrant agencies as advocates’ (Settlement worker 017). Orientation to services was still needed by many of the families, with language continuing to be a major barrier ‘If a person is not within their mandate and if maybe they don't speak English, well they might really struggle…’ (PHN 020). Although families were connecting to PHC services when children were born locally, families with children born outside of Canada could be missed.

Figure 3 displays interactions among network members concerning child growth and development. Public health (PH_09) played a central broker role in addressing child growth and development concerns. Child and legal services (CL_19) also acted as a broker, that is, as a ‘cutpoint’ bringing otherwise disconnected organizations into the network (Burt, Reference Burt2000; Mueller-Prothmann and Finke, Reference Mueller-Prothmann and Finke2004).

Figure 3 Growth and development network

Both PH_09 and CL_19 were part of larger, established institutions, with broad geographic boundaries for service delivery. Both fell under the administration and mandates of the regional and provincial governments. Smaller, less historically based programmes with reliance on volunteers, had less capacity for building relationships. One informant associated with a small, relatively new outreach programme stated, ‘So we go, we network, we tell them about our service but at the same time there's always this clause that your client may not get a volunteer and they may not get us…’ (Outreach worker 012).

Settlement service IM_21 and PH_09 also acted as brokers for nutritional concerns (Figure 4). In addition, one of the drop-in centres, OD_03, was essential as a cutpoint connecting CL_08 and CL_05 into the network. IM_21considered nutritional concerns for refugees, an important reason for seeking out family doctors to assume the medical care of families with young children: ‘…more and more of what we are seeing is many of them [ ] have high, complex health issues [ ] and with the children, malnourishment’ (Settlement worker 017).

Figure 4 Nutrition network

The GI Illness Network (Figure 5) displays a small number of services engaged around GI diseases affecting immigrant children. The role of broker played by the PH communicable disease team (PH_06) was critical given the fragmentation of services around this issue. For GI Illness, PH_06 was needed to connect organizations responsible for child growth and development programmes (PH_09, and Drop-in Centres OD_03 and OD_17) with PC services (PC_31, PC_29, and PC_27).

Figure 5 Gastro-intestinal illness

Interview participants spoke of infectious disease concerns for immigrant families generally, not just GI illness, however, the broker role of PH was still evident within this broader context, ‘…There would be a flag maybe that this child or the family member needs to see the PH nurse immediately or get connected as soon as possible’ (Settlement worker 011). PH mostly relied on the receipt of a laboratory result as follow-up to a physician's diagnostic screening before becoming involved with a family. However, according to the interviews, many recent immigrant families found it difficult to negotiate for health services or see a physician on their own. Even when connected to a PC practitioner, interpretation and advocacy was often still needed:

I just had a client that has hepatitis B, [who] came to my office and says I think ‘I'm going to die. … If I start this medication I'll have to do it for the rest of my life. It costs a lot of money’. I didn't even know that she was not accessing the Pharmacare Programme ….

(Settlement worker 011)

In the Other Needs Network (Figure 6) one of the legal service organizations, CL_05, was identified as the most prominent network broker. Settlement service respondents described some of their involvement with legal services. The need to secure immigrant status for family members was a primary concern. Other concerns related to child protection and the need for advocacy and cultural interpretation by settlement workers in these situations, particularly where cultural differences in child rearing practices arose. The central role of legal services in this network of ‘other needs’, and the connections made into the network through this node by almost all other services, attests to the importance of legal concerns for recent immigrant families and their well-being.

Figure 6 Other needs network

Brokers for PC services/PC as brokers

Physicians in private practice tended not to be actively involved in the broader network of services concerned with immigrant families. Availability of time and work for no pay were identified as disincentives for their involvement. Referrals and phone intake or case conferencing were the most common mechanisms for engaging physicians. Many of these connections were initiated by a PHN and/or settlement worker around a variety of issues requiring the services of a PC physician. ‘[T]here are situations where we will contact the doctor … maybe the mom's milk isn't coming in or we're concerned about weight gain, something like that… .’ (PHN 20). In relation to refugees, ‘… because they come with huge needs or maybe concerns because they spent a lot of time in a refugee camp or being displaced … a lot of parents would require their children to be checked by doctors …’ (Settlement worker 017).

PC physicians, despite their lack of engagement in the network, were recognized by respondents as a link to other needed services outside the study boundaries including diagnostic services and specialists. ‘I mean you don't see a specialist just because you're having a baby. It's just not the way it's done here. So, yeah, children see family doctors, not paediatricians generally’ (PC Physician 16). In this regard, PC physicians also played a major broker role for the entire network, and were in a controlling position as cutpoints for accessing this alternate network of health resources.

The CHC represented in this study also had a different network of resources other than those identified in the network survey; these were co-located services within the CHC contracted with another organization to provide services on site, ‘We operate within the [district health authority] to share mental health care, which includes a couple of psychiatrists and psychiatric nurses that offer counselling, both for adults and for children. Their services include dieticians. We have occupational therapists (and) physiotherapists…’ (CHC physician 30). As a location with access to a different set of services, the CHC was acting as a broker to resources otherwise unavailable, or limitedly so, to the study neighbourhood and the organizations involved.

The bridge

The information presented so far has illustrated how network members realigned with one another depending on the issue, and how different organizations assumed broker roles accordingly. Some organizations were engaged in multiple issues and associated relationships with others. To identify the strongest organizational linkages for dealing with immigrant family concerns, organizations involved with at least one other organization in three or more types of PHC concerns were selected. This created the ‘backbone’ network map illustrated in Figure 7. In this map of strongly tied organizations, PH and immigrant services have the greatest number of ‘strong’ connections to other partners; however, each connects strongly to a separate set of organizations. The drop-in centre in the middle, although it has fewer direct connections compared with others in this map, plays a particularly powerful role for immigrant families with young children. This centre represents a bridge (Valente and Fujimoto, Reference Valente and Fujimoto2010) between other prominent members and their associated linkages, bringing the network together on multiple issues faced by immigrant families.

Figure 7 Organizations with three or more ties (Primary Health Care need connections) to one another

The co-location of services within family drop-in centres was identified as one of the primary mechanisms through which PH was able to link with other partners in the delivery of child and family programmes to immigrants and their young children. Other services located within centres included immigrant services providing English as a Second Language (ESL) classes, while nurse practitioners provided wellness clinics for young mothers.

The purpose behind brokerage

Three distinct purposes attached to brokerage emerged from the key informant interviews: (1) brokerage on behalf of clients, connecting services to meet the needs of families with young children directly, (2) brokerage for the purpose of building partnerships around issues related to immigrant needs, and (3) brokerage for the purpose of building systems competencies. The last two purposes can be combined under a single construct – building capacities.

All three of the brokerage functions were carried out by settlement service IM_21. IM_21 was described as a hub for information concerning immigrant needs, as a source of referral for immigrant families, and as a partner in the delivery of services to high need families, particularly newly arriving refugees. ‘… I have to take my hat off to [IM_21]. I mean they're really the framework that helps get families directed whether it's towards us, whether it's toward …’

IM_21 took time to promote competencies in other partnering organizations through workshops or presentations, or by attending joint sessions with families, using these as teachable moments for other providers. One settlement worker explained, ‘So that motivates me. Motivates me to go and dig more and look for people that can be allies in this system and that maybe are interested in [a] conversation with us and that are interested maybe in changing …’ (Settlement worker 011). An annual immigrant health fair, originally initiated by IM_21, presents an example of an effective mechanism for developing systems competencies through networking and the engagement of multiple partners.

So luckily we were able to start up a little committee to plan the Health Fair which ended up to be an ongoing network and it kept growing. .. We have people from public health, from the children's hospital, from parent resource centre, from other immigrant serving agencies …

(Settlement Worker 017)

Others within the services network (eg, outreach and drop-in centres) also promoted capacities in their partnering agencies, however, these were less strategic as organizational objectives, and more about supporting families during interactions with other less culturally skilled service providers. Most organizations when acting as brokers stood out primarily for their pragmatism in making things happen for their clients. A CHC nurse described a situation where an immigrant mother and newborn had an inaccessible family doctor. PH supported them with a referral to the CHC. Another example involved a family drop-in centre:

… this public housing area has become particularly attractive for newcomer clients… this particular organization is doing a great job in providing internal services to the clients as well as connecting them to the larger community…

(Settlement worker 011)

Discussion

This case study took into account an inter-sectoral and determinants of health perspective applied to health and social services delivery, and what has been encouraged to be optimal PHC practice at the local level (WHO, 2008; Van Olmen et al., Reference Van Olmen, Criel, Van Damme, Marchal, Van Belle, Van Dormael, Hoerée, Pirard and Kegels2010). Literature describing how different service sectors coordinate their activities locally in support of immigrant communities was found to be scarce. Whitaker et al. (Reference Whitaker, Baker and Pratt2007) provided a description of a network model that promoted cultural competency and collaboration among agencies delivering services to Latino women exposed to intimate partner violence in two US communities. The findings from their review demonstrated an improved service system for addressing client needs and promoting access to services using bicultural network coordinators. In another example, a county PH department in Washington State was instrumental in establishing a collaborative network of 26 agencies tasked to collectively develop systemic cultural competencies and capacities tailored for six different marginalized groups including selected ethnic minorities. Results from key informant interviews and focus groups again showed improved systems capacities and expanded collaborative initiatives (Garza et al., Reference Garza, Abatemarco, Gizzi, Abegglen and Johnson-Conley2009).

The SNA techniques used in this study helped to illustrate relationships among service organizations and to identify brokers within the network. The qualitative data helped to describe the organizational relationships as witnessed by key informants, corroborated information portrayed in the network maps, and then furthered our understanding concerning what brokers do in supporting the activities of the network overall. The social network methods in this study have been used in previous research involving other types of services delivery systems that addressed chronic diseases such as HIV/AIDS, mental health, and diabetes (Tausig, Reference Tausig1987; Kwait et al., Reference Kwait, Valente and Celentano2001; Provan et al., Reference Provan, Milward and Isett2002; Rivard and Morrissey, Reference Rivard and Morrissey2003; Provan et al., Reference Provan, Veazie, Staten and Teufel-Shone2005). Eisenberg and Swanson (Reference Eisenberg and Swanson1996) demonstrated the brokerage role played by NGO's for maternal–child services in four different communities. No studies were found applying these methods to services networks for immigrant families.

Limitations

Personal biases may have been introduced into the selection of organizations for this study by the local providers involved in this process; however, the researcher did vet these choices against documented programme descriptions, and later with those interviewed or surveyed. Non-participants (asterisked organizations in Table 2) were more often organizations without a stated mandate to work with immigrants or with the explicit health concerns of young families in the study neighbourhood. For these reasons, organization representatives declined participation in the study, although their opinions may have offered different insights into the workings of the network overall. No information was available to demonstrate how non-participants related to one another. Despite a response rate of 78% (a participation rate of 68% or 21 of 31 when the four proxy organizations are considered part of the denominator) the researcher was able to accommodate missing data by using directional measures of betweenness centrality, a technique supported empirically (Costenbader and Valente, Reference Costenbader and Valente2003). Organizations directed at the needs of immigrant men were not included in this study as the focus concerned services for immigrant families with young children as an exemplar of how services work together. However, exploring services for male immigrants would be another valuable area for future research. Immigrant families themselves did not participate in the study. Without their insights into how families access and use services, the role of organizations as brokers in supporting access to services may have been inflated. More research is needed in other kinds of settings to determine if the findings of this case study apply within different context.

In summary, settlement service IM_21 in this case study was represented in all network relationships considered, sharing the role of network broker with different organizations at different times. This organization was also unique in its strategic capacity building function within the network. PH and PC services had strong links to IM_21, with opportunities for tapping into the knowledge, experiences, and client base of this resource. This, however, was still insufficient in terms of immigrant access since most of this settlement service's activities were focused around the needs of refugees. This deficiency points to the need for different kinds of brokers and services to fill gaps as individual services are often restricted by their mandates, specializations, and/or resource capacities. As demonstrated, PH's associations with family physicians, and another settlement service's association with schools, each provided opportunities for linking immigrant families to needed services. As an accelerator for making connections, family drop-in centres also provided a venue for providers from different organizations to come together in the delivery of services to the local neighbourhood.

A summary of key findings and their application to policy, practice, and future research are provided in Table 3. By supporting network interactions, brokers within this service delivery system helped to mobilize a PHC system for recent immigrant families. This was the most salient finding applied to the local context. Although brokering to build network capacities largely fell to the local settlement service, the results of this study bear witness to the fact that no one agency or agency group was fully responsible for connecting recent immigrants to the services they need. Improved access for immigrant families means all agencies take responsibility for understanding and utilizing the different strengths and assets within the network. The pivotal role in capacity building played by settlement services, as in this case, is an essential ingredient for a coordinated approach wherein assets and knowledge are shared, and all members of the services network are enabled to make a difference for immigrant families.

Table 3 Key findings and their application to policy, practice, and future research

PHC = primary health care.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the dedication of those working in community-based services who strive to address the needs of recent immigrant families, and to thank those who were able to find the time to contribute to this research by sharing their experiences with us. This work was supported by the Dorothy C. Hall Chair in Primary Health Care Nursing, McMaster University, and by the Public Health Agency of Canada.