Introduction

Archaeological theory today finds itself at a complex crossroads with many promising theoretical turns but few methodological bridges. Relentlessly driven by the ontological and material turns in the social sciences and humanities, in recent years a number of archaeologists have shifted from focusing on material culture, meaning and representation to a more direct engagement with things, materiality, materialisms and human–non-human relations (Alberti Reference Alberti2016; Domanska Reference Domanska2006; Gosden Reference Gosden2005; Hicks and Beaudry Reference Hicks, Beaudry, Hicks and Beaudry2010; Fowler and Harris Reference Fowler and Harris2015; Harrison-Buck and Hendon Reference Harrison-Buck and Hendon2018; Hodder 2012; Reference Hodder2016; Hodder and Lucas Reference Hodder and Lucas2017; Jones Reference Jones, Chapman and Wylie2015; Knappett and Malafouris Reference Knappett and Malafouris2008; Malafouris Reference Malafouris2013; Meskell Reference Meskell2008; Olsen Reference Olsen2003; Reference Olsen2007; Reference Olsen2010; Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Shanks, Webmoor and Witmore2012; Robb Reference Robb2015; Shanks Reference Shanks2007; Skibo and Schiffer Reference Skibo and Schiffer2008; Thomas Reference Thomas2007; Tilley 2007; Reference Tilley2017; Webmoor Reference Webmoor2007; Webmoor and Witmore Reference Webmoor and Witmore2008; Witmore Reference Witmore2007). This variety of recent theoretical concepts can be seen as positively contributing to a diversity of approaches in archaeology (Harris and Cipolla Reference Harris and Cipolla2017). There is, however, limited bridge building between deep theory and the tangible material evidence of archaeology itself. Moreover, the atomization and insularization, terminological impenetrability and particularistic applicability of many new concepts only make their methodological operationalization and widespread use in the discipline all the more difficult.

Here we propose the conceptual framework of the assemblage of practice as a middle-range attempt to flesh out and provide methodological rigour to a number of innovative and promising recent theoretical concepts concerned with human–thing relations. We seriously take up archaeologist John Robb’s (Reference Robb2015, 167) call for an ‘applicable theory’ that ‘necessarily mediates between high level philosophies and systematic material culture analysis’. Entanglement (Hodder 2012; Reference Hodder2016), assemblage (Fowler 2013a; Reference Fowler2013b; Harris Reference Harris2014; Harrison Reference Harrison2011; Jervis Reference Jervis2019; Lucas 2012; Reference Lucas, Alberti, Jones and Pollard2013; Normark Reference Normark2010), and correspondence (Ingold 2015; Reference Ingold2017) may seem to have more differences than commonalities, yet we argue that they can be productively framed, organized and operationalized to practically aid archaeologists in accessing, scrutinizing and comparing human–thing relations through time. In lieu of an approach where theory deductively dictates the need for particular kinds of evidence, and carefully eschewing inductive naïveté, our framework has developed abductively (see Marila Reference Marila2017; Peirce Reference Peirce and Turrisi1997, 282). It arises from an intimate engagement with the evidence itself and a simultaneous philosophical wrestling with deep theory – out of what we perceive as the pressing necessity for past humans, things and their relations to be studied at once holistically and from the ground up. Rather than being another new theoretical concept that attempts to explain human–thing relations, our assemblage of practice is a heuristic analytical tool that marshals current and past concepts within a productive esemplastic framework that bridges data and theory and provides archaeologists with new explanatory power.

To explain what assemblages of practice are, we first define the fundamental concept of thing upon which our entire framework rests. We then introduce humans into the dynamic and vibrant panorama of things and briefly discuss the concept of human–thing entanglements, proposing a quantitative valuation of their scale through space and time. The assemblage of practice is then introduced and its practical usefulness as a spatiotemporal analytical tool in archaeological research is illustrated with examples from our research.

Some of the current debates in archaeological theory centre on the ontology of things and their importance to the discipline (see Hillerdal and Siapkas Reference Hillerdal and Siapkas2016). So, to begin laying the groundwork of our framework, what are things to us, the authors?

What are things?

Within the ontological and material turns, the concept of thing has received wide-ranging treatment by philosophers, literary and social theorists, anthropologists and archaeologists (Bennett Reference Bennett2010; Brown 2001; Reference Brown2003; Henare, Holbraad and Wastell Reference Henare, Holbraad, Wastell, Henare, Holbraad and Wastell2007; Hodder Reference Hodder2012; Holbraad Reference Holbraad2011; Holbraad and Pedersen Reference Holbraad and Pedersen2017; Ingold Reference Ingold2015; Knappett 2010; Reference Knappett and Ingold2011; Latour 1993; Reference Latour2005; Santos-Granero Reference Santos-Granero2009; among others). In parallel, exponents of the speculative realist movement in contemporary philosophy subscribing to object-oriented philosophy (or ontology (OOO)) have instead focused their attention on objects (Barad Reference Barad2003; Bogost Reference Bogost2012; Bryant Reference Bryant2011; Edgeworth Reference Edgeworth2016; Garcia Reference Garcia, Ohm and Cogburn2014; Harman 2010; 2011; Reference Harman2013a; Meillassoux Reference Meillassoux2008; Morton Reference Morton2013; Shaviro Reference Shaviro2014). Broadly speaking, these two approaches follow different philosophical trajectories regarding the ontology of things and objects. Although a new definition of thing is beyond the purview of this article, we are strongly inclined to consider any definition of thing (and by extension the one presented here) as ‘thing-as-heuristic’ rather than ‘thing-as-analytic’ (Henare, Holbraad and Wastell Reference Henare, Holbraad, Wastell, Henare, Holbraad and Wastell2007, 5; Witmore Reference Witmore2014). In this way, any attempt at defining things intends to only adumbrate the contours of things rather than forcefully tidy them into a predetermined and neatly packaged taxonomy. We maintain that it is precisely this open-ended approach to things that makes the concept especially useful to our framework of assemblages of practice.

In this paper, we focus primarily on two comparable approximations to defining things. To archaeologist Ian Hodder (Reference Hodder2012, 4–5, 8), things are ‘flows of matter, energy and information’ that come together for a period of time in a ‘heterogeneous bundle’ and are only ‘stages in the process of the transformation of matter’. This is broadly in line with anthropologist Tim Ingold (Reference Ingold2012, 439), who defines things as ‘gatherings of materials in movement’. We do, however, note that replacing ‘matter’ in Hodder’s definitions with ‘material’ is imperative to avoid associations with the hylomorphic model critiqued by us further below. Both these authors ground their conception of thing in the work of philosopher Martin Heidegger (Reference Heidegger and Hofstadter1971) and his concepts of gathering and the fourfold, as well as in his distinction between thing and object (Davis Reference Davis2014, 209–10). As heterogeneous groupings of materials, energy and information in movement, things are therefore not inert and isolated but interdependent and connected. They are gregarious and draw themselves and other things together (Hodder Reference Hodder2016, 4); in fact, ‘things are their relations’ (Ingold Reference Ingold2011, 70, 87). It also follows that things can seem more or less complex depending on the vantage point from which they are perceived (Hodder Reference Hodder2012, 219).

According to such an open definition, things can rightly be anything from a piglet to a paddock and from beer to bartenders. Humans, therefore, are also things (Webmoor and Witmore Reference Webmoor and Witmore2008). The concept of human–thing entanglement (discussed further below), however, clearly sets humans apart with the goal of studying human entanglements with things other than themselves and human–thing interdependence (Hodder 2012, 10; Reference Hodder2016, 5). The separation of human and thing has been criticized by those advocating for a new materialism, a flat ontology and a symmetrical archaeology, as being arbitrary and perpetuating pervasive Cartesian dualisms (Coole and Frost Reference Coole, Frost, Coole and Frost2010; Olsen Reference Olsen2003; Reference Olsen2010; Olsen and Witmore Reference Olsen and Witmore2015; Olsen et al. Reference Olsen, Shanks, Webmoor and Witmore2012; Shanks Reference Shanks2007; Webmoor and Witmore Reference Webmoor and Witmore2008; Witmore Reference Witmore2014). These approaches draw heavily on the work of philosopher of science Bruno Latour (Reference Latour1993), who has championed a democratic, horizontal and flat ontological approach, whereby humans and non-humans are co-equals or co-actants. We agree that in archaeology an ontologically symmetrical and flat analytical approach to the study of things – be they potsherds or people – is fundamental, and approaches that treat material things as backdrops, texts, or mere conduits to meaning can suffer from partiality and incompleteness. Nevertheless, although some archaeologists may reject anthropocentrism, inevitably, to us archaeology is a discipline concerned with humanity and humanness and for ethical, political and epistemological reasons humans must not be sidelined or ignored (Barrett 2014, 68; Reference Barrett2016; Fowles Reference Fowles2016; Lucas Reference Lucas, Hillerdal and Siapkas2016, 190–91; Hillerdal Reference Hillerdal, Hillerdal and Siapkas2016; Silliman Reference Silliman, Der and Fernandini2016, 44; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2013, 13–14; Thomas Reference Thomas, Hillerdal and Siapkas2016; Vigh and Sausdal Reference Vigh and Sausdal2014). In short, humans are central to archaeology but need not be its primary or only matter of concern (Lucas Reference Lucas, Hillerdal and Siapkas2016, 191). We agree here with Craig Cipolla (Reference Cipolla2018, 64) when he asserts that archaeology can be anthropocentric without ‘wholly betraying the flat or symmetrical starting point of our analyses’. The reasoning for this is further explained in the section on entanglement. To continue illuminating the farraginous nature of things let us briefly explain why we cling to things rather than employ any of the terms often used in their place.

Itinerating things, not static objects

It is the case that thing, artefact, material culture and object are terms all too often interchangeably and uncritically used in the social sciences and humanities, and for that matter in much anthropological and archaeological literature. Our framework eschews terminological muddiness and rests upon clear definitions and understandings of these terms. The first term, artefact, is not a term at odds with our definition of ‘thing’ as it is a material thing with which humans engage and which becomes incorporated into human temporality through action and/or language; artefacts ‘maintain evidence of human agency’ (Chazan Reference Chazan2019, 5–7, 18). We nevertheless consider the widely used term material culture out of keeping with our framework as it has been critiqued for arbitrarily and artificially dividing culture into ‘material’ and ‘immaterial’ domains, thereby only deepening the often problematic rift of Cartesian dualisms. Material culture, moreover, perpetuates a hylomorphic model that proposes that objectification – the process of making objects by humans – begins with a mental blueprint, derived from cultural understandings, that is then turned into a materialized form of that mentalization (for a classic definition see Shanks and Tilley Reference Shanks and Tilley1987, 130; for recent discussion see Ingold 2007b; Reference Ingold2013, 94–96; Jones Reference Jones, Cunliffe, Gosden and Joyce2009, 98; Miller Reference Miller2010, 54–68; Preucel and Meskell Reference Preucel, Meskell, Meskell and Preucel2007, 14–15; Thomas Reference Thomas2007, 18–22; Tilley Reference Tilley, Tilley, Keane, Küchler, Rowlands and Spyer2006). In contraposition to such hylomorphism stands the position that culture is never congealed but is always movement, process and undergoing, rather than the material repetition of frozen preconceptions (Thomas Reference Thomas2007). Consequently, we contend that the material should not be artificially separated from the cultural as they are intimately entangled and are mutually transformational.

Object is an even more pervasive term in archaeology. To many, an object implies its dialectic counterpart – the subject. This dualism has its basis in the philosophical legacy of Descartes, Kant, Hegel and Marx, among others, and their foundational approaches that have structured much of Western dialectical thought. As intimated above, object also tows in its wake the long-standing discussion on objectification. The qualitative shift from object to thing can be likened to the way scholarly discourse has shifted from notions of space to those of place, and from the idea of environment to that of landscape (Hodder Reference Hodder2012, 10; Ingold Reference Ingold1993; Tilley Reference Tilley1994).Footnote 1 Objects exist as static entities whereas things occur – they are dynamic and vibrant (Bennett Reference Bennett2010); simply illustrated, if objects are nouns then things are verbs (Ingold Reference Ingold2015, 124). Moreover, the world is a world of things,Footnote 2 since ‘[o]bjects and subjects can exist only in a world already thrown, already cast in fixed and final forms; things, by contrast, are in the throwing’, and ours is ultimately a world without objects (Ingold 2013, 94; Reference Ingold2015, 13–17).

The congealed and impermeable boundedness of the concept of object (Bogost Reference Bogost2012; Harman Reference Harman2013b, 29) is the aspect most difficult to reconcile with a world in constant motion. While humans experience limited linear life histories, other things often outlive us. Things can exhibit simultaneous itineraries that run concurrently to our lives as they become relationally knotted with the lifelines of other persons and the itineraries of other things (Fontijn Reference Fontijn, Hahn and Weiss2013, 192; Hahn and Weiss Reference Hahn, Weiss, Hahn and Weiss2013; Joyce 2012a; Reference Joyce and Shankland2012b, 124; Joyce and Gillespie Reference Joyce and Gillespie2015, 11–12; Skousen and Buchanan Reference Skousen, Buchanan, Buchanan and Skousen2015). The itineraries of things can therefore extend over a series of human lifetimes (for example, in the case of heirlooms or ancient oaks) (Hahn and Weiss Reference Hahn, Weiss, Hahn and Weiss2013; Hodder Reference Hodder2012, 5; Joy Reference Joy2009, 543). Clearly, many things from the past persist within human–thing relationships, changing hands, and often itinerating indefinitely within frames, cases and drawers in museums (Fontijn Reference Fontijn, Hahn and Weiss2013, 186), or perduring by acting as analogues to chronotopes in the form of temporally charged buildings in the landscape (Bakhtin Reference Bakhtin, Holquist and Austin1981, 84–85; Ingold Reference Ingold1993, 169). Like humans, other things also change. A case in point is Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, which has dramatically transformed through the centuries as a result of both natural and human-induced, environmental, chemical and mechanical processes (Domínguez Rubio Reference Domínguez Rubio2016). Since things are only gatherings of materials in motion, they can also become some-thing else. Solid material things are often reused, re-mended, reconstituted and reassembled into new and often hybrid things: kettle spouts can be refashioned into smoking pipes, wine bottles washed and used to store water, and cracked pots mended with wire to be used once more. These qualities that many things possess also mean that they can complicate, layer and unravel linear time and many of them can be seen as constituting palimpsests (Hodder Reference Hodder2012, 98; Lucas Reference Lucas2005, 117; Pauketat Reference Pauketat, Robb and Pauketat2013).

Moreover, not only do many things perdure and change physically, they also exhibit restless and ever-itinerating ‘lives’ as they move through different social, cultural, economic and ideological regimes of value (Appadurai Reference Appadurai and Appadurai1986; Hoskins Reference Hoskins1998; Keane Reference Keane1997; Kopytoff Reference Kopytoff and Appadurai1986; MacKenzie Reference MacKenzie1991; Munn Reference Munn1986; Thomas Reference Thomas1991). Things itinerate, most often accompanied by humans. For example, the coca leaf assumes a vastly different existence when it is used by a Peruvian highlander as part of a religious ceremony or just masticated with lime as a stimulant. The humble coca leaf also enters vastly different regimes of value once it is processed into transgressive cocaine and illegally itinerates thereafter. Likewise, the Mona Lisa’s significance has changed through time as it has itinerated, and continues to do so, through changing regimes of meaning, value and power, from Leonardo’s last brushstroke to the painting’s current hyper-curated position in the Louvre (Domínguez Rubio Reference Domínguez Rubio2016). In this way, in our framework, things (including humans) are not seen as self-contained entities (objects) but as lines, and therefore to us the world is not as ‘a layout of interconnected objects but as a tapestry of interwoven lines’ (Anusas and Ingold Reference Ingold2013, 66, original emphasis).

It is important at this point to note that to archaeologists, objects often are things that have been severed from their past relational contexts (including past social contexts (Nativ Reference Nativ2018a, 8–10)) and temporarily ‘frozen’ in the present for scientific analysis by being placed in an artificial object-state as objects of perception or attention – or simply as objects of study. We contend that there are no objects outside the mind, only things. The material remnants of the past we recover through archaeological investigations may initially appear to us as mute objects severed from their vibrant past relational contexts (Cornell and Fahlander Reference Cornell and Fahlander2002, 23), yet trying to keep things in an object-state is unnatural, difficult and problematic, since objects naturally tend towards inherent and unruly thingness. If objects are only temporary and artificial mentalizations, then the duty of archaeologists is to ultimately ‘return’ these to their vibrant and natural (as opposed to artificial) state of relational thingness and reinsert them as things within our subsequent archaeological interpretations of the past – not just leave them as detached, orphaned and inert analytical objects.

Furthermore, things, unlike objects, are not mere representational intermediaries to something else beyond them – namely human intention and meaning. We want to make clear that we are not advocating throwing objects and object studies out with the proverbial bathwater. Objects, as shall be discussed further below, are necessary and inevitable steps in archaeological analysis and interpretation; moreover, it may be argued that the ability to mentalize objects is one of the things that makes us uniquely human. Outside our minds, things, however, are inevitably and inescapably just that – things. The emphasis on things in our framework once again stresses a symmetrical ontological approach to things and humans whereby archaeologists do not solely seek out objects because of what they can tell us about humans. Rather, a focus on things as things moves archaeologists beyond an interest in hermeneutics and semiotics alone and into the territory of the dynamic itineraries of things themselves and their entanglements with other things and humans. These multiple considerations provide the basis of our ultimate pursuit of things over objects in this paper and their use in the relational concept of entanglement.

Entanglement

In anthropology and archaeology various formulations of the non-representational relationship between humans and things have been proposed in recent years. Among these are entanglement (Hodder Reference Hodder2011; Reference Hodder2012; Reference Hodder2014a; Reference Hodder2014b), assemblage (Fowler Reference Fowler, Alberti, Jones and Pollard2013a; Reference Fowler2013b; Harris Reference Harris2014; Harrison Reference Harrison2011; Jervis 2018; Reference Jervis2019; Lucas 2012; Reference Lucas, Alberti, Jones and Pollard2013; Normark Reference Normark2010), constellation (Roddick and Stahl 2016a, 9–11; Reference Roddick and Stahl2016b; Wenger Reference Wenger1998, 126–27), meshwork (Ingold 2007a; Reference Ingold2011), correspondence (Ingold 2015; Reference Ingold2017), material engagement (Gosden and Malafouris Reference Gosden and Malafouris2015; Malafouris Reference Malafouris2013), bundle (Pauketat Reference Pauketat, Robb and Pauketat2013), entrainment (Bauer and Kosiba Reference Bauer and Kosiba2016), and network (Knappett 2011; Reference Knappett and Knappett2013; Latour 1993; Reference Latour2005). As we already pointed out, we consider this diversity in approaches to be productive and agree with archaeologist Chris Fowler (Reference Fowler, Alberti, Jones and Pollard2013a, 237) that each of these concepts has been created to address specific issues and each has been effective in this regard. In this paper, we nevertheless seek to reconcile the concepts of entanglement, assemblage and correspondence (as well as meshwork) to each other. We then tie them into a larger useful conceptual framework that methodologically operationalizes and fleshes out these concepts by means of assemblages of practice. Let us begin by briefly explaining entanglement.

Entanglement is a concept that seeks to illustrate and explain the relationship between humans and things and has been applied to archaeology in recent years by Hodder (Reference Hodder2011; Reference Hodder2012; Reference Hodder2014a; Reference Hodder2014b; Reference Hodder2016) and from there on adopted by a number of archaeologists (see Der and Fernandini Reference Der and Fernandini2016). Entanglement has its roots in anthropologist Nicholas Thomas’s (Reference Thomas1991) seminal study of gifts and commodities and their colonial and imperial entanglements with Westerners and Pacific Islanders. Although Hodder’s theory of entanglement may be in many ways indebted to Thomas, it goes much further to formulate a novel and holistic approach to the study of humans and things in archaeology. His concept of entanglement begins with human–thing relations and focuses on the dependence or reliance linking humans and things and their resulting dependency or constraint (Hodder Reference Hodder2016, 5). Entanglement thus explores how things create specific practical entrapments between humans and themselves.

Humans and things are relationally produced in entanglements and they become entrapped within these relations in mutual dependencies. To Hodder, dependencies have two aspects: on the one hand dependence (reliance and contingency) is helpful and enabling to humans; on the other, dependency (one-way constraint) and co-dependency (two-way constraint) are negative and entrapping (Hodder Reference Hodder2014b, 20). Naturally occurring things such as moss, glaciers and raccoons have their cycles of birth, life and death, yet human-dependent things cannot reproduce on their own. They require humans. Moreover, they often need further things to function, as in the case of a ceramic pot that needs a kiln to be fired. It is in this way that humans rely upon things and are involved in their itineraries, effectively becoming increasingly entrapped in new and denser entanglements from which it becomes harder to disentangle through time.

As has been mentioned previously, the primary goal of symmetrical archaeology and the New Materialisms movement is to bring other-than-human things to an equal footing with humans. We have argued above that an analytically symmetrical approach to things and humans in archaeology is fundamental since it correctly challenges long-standing practices of treating things merely as representations or conduits to hidden meaning. Analytical symmetry, however, is quite different from relational symmetry. Whereas at times in prehistory humans had the ‘upper hand’ over things, in more recent human history the tables turned as dependency crept in and the ‘sticky entrapments’ created by things in fact made things influential and dominant in human–thing relations (Hodder Reference Hodder2014b, 27–30). The reality is that humans and things do not operate on a symmetrical relational footing – humans can become enthralled, entrapped and obliged to become part of the itineraries of things. Human–thing relations, therefore, are inescapably asymmetrical and humans often become wholly dependent on things, addicted and even subservient to them (Harman Reference Harman2014; Hodder and Lucas Reference Hodder and Lucas2017). Entanglements (as well as disentanglements) can therefore not only be empowering, productive and beneficial, but also disempowering, destructive and violently unequal as they assume different natures when viewed from different social positions and in relation to differing interests (Antczak Reference Antczak2017, 146; Bauer and Kosiba Reference Bauer and Kosiba2016; Hodder Reference Hodder2012, 214). Let us now turn to discuss how we analytically conceptualize the scales of entanglement.

Scales of entanglement

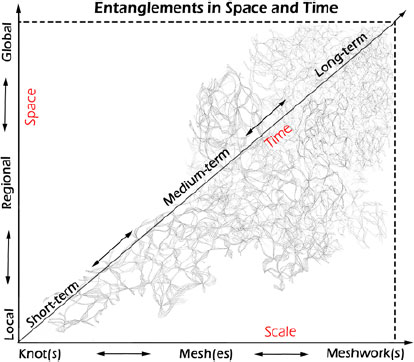

The actor-network theory (ANT) of Latour (1993; Reference Latour2005) has been widely applied yet also criticized as regards its usefulness in accurately representing and analysing the complexity of social interactions (Mol Reference Mol2010). One ANT critic has been Ingold (2007a, 80–82; 2008; Reference Ingold2011, 85), who argues that life does not occur in a series of interconnected nodes, as is often represented in ANT, but rather life is lived along linear trails. Ingold’s alternative idea of the meshwork, based on French philosophers Henri Lefebvre’s (Reference Lefebvre and Nicholson-Smith1991, 117) meshwork and Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s (Reference Deleuze, Guattari and Massumi2004, 290) rhizome, is born from an organic lifeworld where relationality between humans and things is not bounded by networks of nodes and lines but rather occurs, again, along lines. In this way, as represented in Figure 1, in our conception the lives of humans and the itineraries of things radiate outward through space and time along trails beginning at birth or origin as they become entangled in knots with the lifelines of other persons and the itineraries of other things. The result is ‘not so much nodes in a network as knots in a tissue of knots’ comprising a meshwork (Ingold Reference Ingold2011, 71). Therefore (as seen in figure 1), human lives and the itineraries of things are perceived as radiating from a centre in the manner of an asterisk or a fungal mycelium (Ingold Reference Ingold2011, 87; Latour Reference Latour2005, 177; Pauketat Reference Pauketat, Robb and Pauketat2013, 51–52). The outer edges of these tangled knots and meshes are not bounded, as things are not bounded in themselves; rather the knots are frayed and open, constantly ‘ravelling here and unravelling there’, ‘trailing innumerable loose ends at the periphery’, and ‘groping towards an entanglement with other lines, in other knots’ (Ingold 2011, 71, 85; 2013, 132; Reference Ingold2015, 13–17, 22–25; Lefebvre Reference Lefebvre and Nicholson-Smith1991, 118).

Figure 1. Diagram of the scales of entanglement in space and time. The arrows show recursion where the long-term and large-scale meshwork(s) can impact new local events of knotting, and vice versa; thus the global can also become nested within the local.

We propose that changes and continuities in entanglements through space and time can be analytically conceptualized in three scales of entanglement, and these scales can be useful to further understand how entanglements operate through space and time (figure 1). Every entanglement begins with a knot. Knots of entanglement are the foundational elements of meshes and the meshwork. Knots are where – for the purposes of this paper – the lifelines of humans and the itineraries of things interlace to later splay and tangle anew or fray, disentangle, and reach a dead end. It is also within such knots of entanglement that humans and things initially become caught up in relations of enabling dependence and constraining dependency. The particular actions, occurring within the short-term timescale, which create knots between people and things can be as simple as an 18th-century ship’s captain purchasing a ceramic punch bowl in a British port, or a group of merrymakers drinking at a fancy New England supper, imbibing punch and eating roast mutton (Beaudry Reference Beaudry and Symonds2010).

The intermediate scale of entanglement is that of the mesh. Meshes, then, are groupings of knots where the number of HH, HT and TT entanglements increases (figure 1). Meshes can involve groups or communities of people related by task, relations of production or practice, usually within localized spatial contexts. A tight example of a mesh is the seafarers on board a ship during a voyage, principally related through their seafaring occupation and confinement in space and living with a limited set of available material things, whether they be a hammock, a hogshead of salted peas or a pair of breeches. Most meshes are created by events or series of events (during the medium-term timescale) that may occur in the span of various months or years. Furthermore, these meshes of entanglement are a product of the practices of everyday life with its habitual actions involving maintenance activities (Montón-Subías and Hernando Reference Montón-Subías and Hernando2017), as well as innovation and change (Robin Reference Robin2013). As shall be discussed in the following section, meshes of entanglement in the archaeological record can be fleshed out through assemblages of practice.

Finally, the meshwork is the entire skein of entanglements composed of a multiplicity of meshes and countless knots of humans and things, fraying and entwining in all directions (figure 1). The entire meshwork in its complexity can only be perceived and studied from the time perspective of the long term. Styles change (Deetz Reference Deetz1996, 89–124); empires rise and fall; humanist philosophy and science push aside religion and begin to percolate into society at large; and capitalism, globalization and modernity increasingly infiltrate people’s lives. On the other hand, countering these changes, are the short- and medium-term agential forces of resistance, persistence, survivance and residence (Panich Reference Panich2013; Silliman Reference Silliman2009; Reference Silliman, Ferris, Harrison and Wilcox2014; Vitelli Reference Vitelli2011) which perpetuate equally important sociocultural continuities within the meshwork (Montón-Subías and Hernando Reference Montón-Subías and Hernando2017) in all their nuance (Brumfiel Reference Brumfiel2006). The meshwork therefore absorbs the local, regional and global spatial scales within its vast structure, bringing to light changes and continuities in the core and peripheral parts of entanglements through time (Hodder Reference Hodder2012, 109).

The reason for our insistence on defining the three scales of entanglement goes to the core of anthropological inquiry itself – namely the understanding of the roles of human agency within social structure, the exploration of the consequences of the particular for the universal, and the investigation of change and continuity in the short, middle and long term. Entanglements may occur at different temporalities and spatial scales, and change can be initiated by events anywhere within an entanglement (Hodder Reference Hodder2012, 159). For example, entanglements running into the past can have effects on events of entanglement occurring in the present and may affect new entanglements into the future. It also follows that human–thing entanglements occurring during specific events and in the practices of everyday life contribute in one way or another to the creation of the entire meshwork. In turn, recursively, the meshwork affects the creation of new events of entanglement between humans and things on local, regional and global spatial scales, and these often paradoxically manifest themselves as situated globalities (Blok Reference Blok2010, 509) or world sites (Vasantkumar Reference Vasantkumar2017), where the global is nested in the local.

In the following section, we explain our approach to archaeologically identifying changes and documenting continuities in medium-term meshes of entanglements. Because entanglement as an abstract concept must be made analytically accessible to and operational by archaeologists, we now turn to putting flesh on meshes of entanglements by first defining the assemblage.

Assemblage

As we have suggested above, entanglements exist at multiple spatiotemporal scales, yet they originate through concrete human actions, during events and in quotidian life. One way to connect past events and the archaeological record is via the concept of assemblage, which owes much of its development to philosophers Deleuze and Guattari (Reference Deleuze, Guattari and Massumi2004). More recently, philosophers Manuel DeLanda (Reference DeLanda2006, 12–16) and Jane Bennett (Reference Bennett2010, 23–24) have built upon their ideas to propose assemblage theory. Assemblage theory has in turn been adopted, among others, by archaeologists Chris Fowler (2013a; 2013b; Reference Fowler2017), Ben Jervis (2018; Reference Jervis2019), Gavin Lucas (2012; Reference Lucas, Alberti, Jones and Pollard2013; Reference Lucas2017), and Johan Normark (2006; Reference Normark2010), each with their own definitions and theoretical and methodological particularities (Van Vliet Reference van Vliet2015; see also Hamilakis and Jones Reference Hamilakis and Jones2017). Among these definitions, Lucas (Reference Lucas, Alberti, Jones and Pollard2013, 375) proposes that assemblages are ‘collectives or systems of usually familiar entities (which include humans, pots, arrowheads etc.) that cohere in stronger or weaker ways and for longer or shorter durations’.Footnote 3 We broadly adhere to this definition, yet in our reading of the concept we stress that assemblages are not merely artificially cobbled-together heterogeneous bits and pieces. Rather, they are dynamic gatherings of corresponding things entangled through human practice.

Events are the catalysts of assemblages, which in material terms can be thought of as the way in which things ‘come together and disperse at specific times and places’ – it follows that every thing needs to be seen as the product of one or multiple events (Aldred and Lucas Reference Aldred, Lucas and Bolender2010, 191). The reality, however, is that few such assemblages leave archaeological traces. Yet as archaeologists ‘we must be able to situate these elements within an archaeologically discernible set of relations’, these relations being the entanglements between individual humans or human communities of the past and the material things we recover (Aldred and Lucas Reference Aldred, Lucas and Bolender2010, 191) (figure 2). It is imperative that the reconstruction of these relations begins with the material things themselves, since, ‘If everything is relational, mixed, heterogeneous, messy, then analysis must proceed in a bottom-up way, refusing to consider things out of their contexts, always building up from the daily practices of everyday life and the mundane fixes that people find themselves in’ (Hodder Reference Hodder2016, 10). As archaeologists, we first observe inert objects in the excavation trench, and upon extracting them we analyse such objects of study on our lab tables. We then temporarily bring them together into collections of associated objects (these can be conceptualized as networks) through contextual, depositional, or in situ spatial associations – in the ground itself – as well as organize them into intra-site associations with other objects (figure 2) (Hodder Reference Hodder1986).Footnote 4 Such groupings, as shall be discussed in two case studies further on, can, for example, involve all the archaeologically and textually recoverable paraphernalia of 18th-century Anglo-American punch drinking, or the combination of material and organic residues that reflect the character and quality of past meals.

Figure 2. Diagram illustrating the process of reassembling assemblages of practice. (I) First, whether through excavation, laboratory analysis or collection studies, the archaeologist observes objects of study (be they teapot sherds or a stone wall); on the other side are the often unknown humans of the past who interacted with these static objects which were (and still are) dynamic and vibrant things. (II) Next, in a midway interpretive step, the objects of study are organized into relational groupings of objects by utilizing contextual, depositional and other independent lines of evidence and these are re-entangled with past human communities which can be, among other things, reconstructed through textual, visual, ethnographic and oral historical evidence. (III) The outcome of this process of re-entangling is vibrant reassembled assemblages of practice in which humans and things corresponded during events and in the situated activities of everyday life in the past.

These groupings of objects, however, are by no means the goal and end result of our approach. Groupings of objects linked by archaeologists are merely relational associations between objects; they are in fact a bricolage of agglutinative accretions (Ingold Reference Ingold2015, 23). Moreover, these objects of study are in reality ‘uncanny’ or ‘haunted’ things, ‘because they once formed part of a world that no longer fully exists, part of an assemblage that once included human beings who are no longer alive’ (Thomas Reference Thomas, Hillerdal and Siapkas2016, 161). Groupings of objects are artificially and temporarily severed from the past living individuals and dynamic communities which, through their practices, engaged with vibrant things, not static objects.Footnote 5 Grouping or associating objects is, therefore, only an analytical and interpretive step midway toward reassembling assemblages of practice (figure 2).

Assemblages of practice

Practice theory, developed through the works of sociologists and anthropologists Pierre Bourdieu (Reference Bourdieu and Nice1977), Sherry Ortner (Reference Ortner1984), and Marshall Sahlins (Reference Sahlins1985), as well as Anthony Giddens’s (Reference Giddens1979) theory of structuration, and took up the challenge of bridging the opposition of structure and agency by means of its central idea of practice, namely that people ‘enact, embody and re-present traditions [structures] in ways that continuously alter those traditions [structures]’; those ways being practices or ‘people’s actions and representations’ (Pauketat Reference Pauketat2001, 74, 79; Ortner Reference Ortner2006). Practice-based or historical-processual models have been used effectively to understand the past by, among others, archaeologists Timothy Pauketat (Reference Pauketat2001), Rosemary Joyce (Reference Joyce, Mills and Walker2008; Joyce and Lopiparo Reference Joyce and Lopiparo2005), and Stephen Silliman (Reference Silliman2001; Reference Silliman2009). The concept of communities of practice applied in recent years to archaeology has also highlighted the situatedness of everyday learning in communities dedicated to particular practices (e.g. pot making, weaving, trading, etc.) (Mills Reference Mills, Roddick and Stahl2016; Sassaman and Rudolphi Reference Sassaman and Rudolphi2001).Footnote 6 These archaeological approaches are also concerned with events and everyday life as these are manifested in material patterns of practice (Gilmore and O’Donoughue Reference Gilmore, O’Donoughue, Gilmore and O’Donoughue2015, 15). Practices, however, do not always leave notable material traces in the archaeological record, yet we argue that many can be discovered by retracing the entanglements of things and humans and by reassembling inert groupings of objects into vibrant assemblages of human–thing practice (figure 2).

Historical archaeologist Mary Beaudry has in recent years devised the term ‘assemblages of practice’ to describe the complex association of humans and things involved in foodway practices in 18th- and 19th-century North America. She has advocated for looking beyond archaeological collections composed only of groupings of objects to view:

an archaeological collection not just in terms of what fits back together literally and can be mended and included in a vessel count, but also to discover what fits back together in terms of practices and to attempt to comprehend what the intended outcomes of various practices might have been. This requires considering more than just the individual artefact or artefact type used, but attempting to reconstruct, for want of a better phrase, ‘assemblages of practice,’ or perhaps, ‘ensembles of practice’ (Beaudry Reference Beaudry2013, 187).

In our conception, an assemblage of practice is a mesh of human–thing entanglements that correspond in stronger or weaker ways, developing relations of dependence and dependency, for longer or shorter durations during events and in the practice of everyday life. It has been proposed by Silliman (Reference Silliman2009, 216) that past everyday life and practice can be inferred or interpreted from the archaeological record since ‘objects are constituents and proxies of practice’. We challenge this statement and argue that although archaeologically recoverable material things (not objects) are certainly constituents of past practice – since assemblages of practice are composed of human–thing entanglements – a thing cannot be a proxy of practice by itself, bereft of its relational entanglements with humans and other-than-human things.

Assemblages of practice are not cobbled together from individual entities as if in a ‘cosmic bricolage’ (Ingold Reference Ingold2014, 232). Rather, they are composed of meshes of lines where the majority of relations between things are based on correspondence, which means they are sympathetically with, not additively and in nature (Ingold Reference Ingold2015, 23).Footnote 7 Correspondence is therefore central to assemblages of practice as it constitutes the ‘dynamic in-between-ness of sympathetic relations’ rather than the ‘static between-ness of articulation’ (Ingold Reference Ingold2015, 148).Footnote 8 It is for this reason that we must stress at this point that, even though we insist on using the word ‘assemblage’ for the sake of maintaining continuity with the growing discussion of assemblage theory, the conception of assemblage that we have already espoused is much more in line with the original French term agencement used by Deleuze and Guattari. Translating agencement into English is impossible since the English word ‘assemblage’ principally refers to an articulated and static configuration such as that of lines connecting nodes, whereas agencement refers to assembly and fitting together and stresses ongoing process and movement, and the dynamic in-between-ness and sympathetic relations like those of interwoven lines (Ingold Reference Ingold2017, 13, 14; Jervis Reference Jervis2019, 36; Manning Reference Manning2016, 6, 123–124; Nail Reference Nail2017, 22–23; see also Van Dyke Reference van Dyke2018). Within our term ‘assemblage of practice’, we dovetail this understanding of ‘assemblage’ as agencement with ‘practice’ not only to reference the dynamism, process and constant change addressed by anthropological practice theory but also to terminologically centre our framework around human activity without compromising analytical symmetry between humans and things.

The vibrant entanglement of humans and things within assemblages of practice also produces properties that often exceed their components (DeLanda Reference DeLanda2006, 5; Robb Reference Robb2015, 177; Witmore Reference Witmore2014, 207), or rather their ingredients (see Ingold Reference Ingold2014, 232). Assemblages of practice are therefore theatres of correspondence par excellence. As has been explored by Antczak (Reference Antczak2018), 17th- to 19th-century assemblages of practice on the salt pans of the Venezuelan Caribbean islands synergistically entangled such disparate things as humans, their tools (wooden rakes, shovels, wheelbarrows and pumps) and the structures they erected on the salt pans (dikes, walkways and inlet channels) with the rhythms of the microorganisms (brine shrimp, algae and prokaryotes), the chemical compounds, the tides and the clouds in the practice of salt cultivation. In this way assemblages of practice deliberately dismantle the ‘conventional boundary between culture and nature, so that both ecologies and societies can, together and independently, be assemblages’, thereby dissolving pervasive Cartesian dualisms (Thomas Reference Thomas2015, 1294).

Assemblages of practice also entangle affective fields and the sensorial and sensuous aspects of everyday human life (Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis2017; Harris and Sørensen Reference Harris and Sørensen2010, 150–51). Entanglements not only knot humans and material things, they also involve immaterial things such as ideas, thoughts, emotions, desires and sensory perceptions (Hodder Reference Hodder2016, 9). The practices of everyday life produce affective relations. The events of the past were ‘“total events” that engage[d] all the senses: sight, sound, smell, taste, touch’ (Beaudry Reference Beaudry2013, 185; cf. Harris and Sørensen Reference Harris and Sørensen2010, 150). It is important here to note that the human sensorium with its five distinct senses (among which sight (Thomas Reference Thomas, Thomas and Jorge2008) and hearing are considered the most important) is an Aristotelian construct and part and parcel of the Western Cartesian world view, whereas sensory experience is in reality always synaesthetic and intersensorial (Hamilakis 2011, 210; Reference Hamilakis and Day2013, 410). There has been a concerted effort in recent years to stress not only the importance of emotion and the senses in archaeology, but also how these can be appropriately studied (Day Reference Day2013; Fahlander and Kjellström Reference Fahlander and Kjellström2010; Fleisher and Norman Reference Fleisher, Norman, Fleisher and Norman2016; Hamilakis 2011; 2013; Reference Hamilakis2017; Harris and Sørensen Reference Harris and Sørensen2010; Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2010; Loren Reference Loren2008; Mills Reference Mills2014; Pellini, Zarankin and Salerno Reference Pellini, Zarankin and Salerno2015; Skousen Reference Skousen2018; Tarlow Reference Tarlow2012). As Antczak (Reference Antczak2017, 147–48) has urged, part of reassembling assemblages of practice involves the reassembling – where possible – of emotion and sensory perception. This must, however, be done with great caution to avoid the common pitfalls of reading contemporary emotions back into pasts where they were felt differently, if at all, and misunderstanding the historical context of emotions (ahistoricism) (Fleisher and Norman Reference Fleisher, Norman, Fleisher and Norman2016, 4; Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis and Insoll2011, 208).

The often rich contextual sources of textual and oral information available to some archaeologists make accessing emotion in the more recent past attainable. Past emotion, such as grief, for example, is discussed in the analysis of a song composed by a Dutch sailor upon the violent death of his comrades at the hands of the Spaniards on the salt pan of La Tortuga Island, Venezuela, in 1638 (Antczak, Antczak and Antczak Reference Antczak2015). Although emotion is exceedingly difficult to elicit from material remains alone (where documentary and oral historical evidence is available it is much more approachable), sensory experience is itself material in the sense that it requires materiality or material things to be activated (Hamilakis Reference Hamilakis and Insoll2011, 209). In conclusion, assemblages of practice invariably include such sensory realities as the raspy sound of a wooden rake being scraped over a dry crust of salt on a salt pan, the mouthwatering smell of roast mutton at supper, and the haziness and disinhibition resulting from drinking too much rum punch.

Change, continuity and transformation in assemblages of practice

Humans and things become relationally entangled in assemblages of practice for shorter or longer durations during events and in everyday life. Even though these assemblages principally express correspondences between human lifelines and the itineraries of things, much as individual entanglements, they are often asymmetrical and do not always prove helpful and enabling to humans. Structure is produced by the knotting and subsequent entrapping of humans and things in stronger or weaker entanglements, establishing relations of enabling dependence or constraining dependency (Hodder Reference Hodder2012, 213). We argue that examining assemblages of practice, which are inherently heterogeneous, has the potential to illuminate this interplay of dependence and dependency, change and continuity, and agency and structure, because ‘the locus of agency is always a human–nonhuman working group’ (Bennett Reference Bennett2010, xvii).

Since assemblages of practice exist during events and in the situated activities of quotidian life, it is at this medium-term timescale that changes and continuities in structures can be elicited, and their gradual or more punctuated transformation can be better understood. Issues of the micro and macro scale permeate and polarize archaeological investigation (for recent discussion see Beaudry Reference Beaudry, Casella and Symonds2005; Robb and Pauketat Reference Robb, Pauketat, Robb and Pauketat2013; Voss Reference Voss2008). In recent years, numerous archaeologists have turned to studying past events in an effort to move from considerations of protracted evolutionary processes to those of punctuated change occurring in historical events (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Bolender, Brown and Earle2007; Bolender Reference Bolender2010; Gilmore and O’Donoughue Reference Gilmore, O’Donoughue, Gilmore and O’Donoughue2015; Lucas Reference Lucas2008). Many of these approaches draw upon the influential definition of events by historian William Sewell (Reference Sewell2005, 227), who proposes that events are ‘sequences of occurrences that result in transformations of structures’, with these occurrences being mostly of relatively short duration (Lucas Reference Lucas2012, 182). In a similar vein, Silliman (Reference Silliman, Oland, Hart and Frink2012) develops a multi-scalar approach to time, proposing a bridging meso scale that prevents archaeologists from falling into the problematic dichotomies of what he calls the ‘short purée’ and the longue durée. Furthermore, archaeologist Cynthia Robin (Reference Robin2013; see also Overholtzer and Robin Reference Overholtzer and Robin2015), inspired by French scholars Henri Lefebvre (2004; Reference Lefebvre and Moore2008) and Michel de Certeau (Reference de Certeau and Rendall1984; de Certeau, Giard and Mayol Reference de Certeau, Giard, Mayol and Tomasik1998), has proposed focusing on people’s everyday lives since at this timescale social change happens as people ‘accept and question, consciously or unconsciously, the meaning of existing social relations’ (Robin Reference Robin2013, 6, 44). Our assemblages of practice offer a way in which to interpret events in the archaeological record in terms of things (Lucas Reference Lucas2008, 62) as well as their traces (Joyce Reference Joyce2015). Assemblages of practice are therefore positioned within the temporal meso scale, where during events and through the situated practices of everyday life people entangle and disentangle with things which enable and constrain them, and in the process, people establish, challenge and transform structures.

Not all assemblages of practice enact changes in the larger meshwork or structure; some perdure and persist, whereas others cease. How some assemblages of practice create change in structures can be likened to a rock thrown into a pond; some ripples quickly fade from sight while others of greater amplitude may exert transformative change on near or distant shores (Anderson Reference Anderson, Gilmore and O’Donoughue2015, 223; Swenson Reference Swenson2018, 81) and at different temporal scales (see Crellin Reference Crellin2017). At the core of such changes are entanglements between humans and things because ‘the conjunction of temporalities from anywhere within entanglements can produce events that elicit response and change’ (Hodder Reference Hodder2012, 160). Consequently, human–thing entanglements may transcend timescales and can enable humans and communities; but in so doing they also pull people further into new relations of care and dependency (Rizvi Reference Rizvi2017). It is important to underscore that entanglements begin as practical, situated and everyday events of knotting. As these entanglements become denser, however, it is hypothesized that not only does change accelerate; entrapment does as well (Hodder Reference Hodder2012, 177).

Reassembling assemblages of practice

In contrast to Fowler (Reference Fowler2013b, 53–63) and Oliver Harris (Reference Harris2017), who argue that assemblages can become increasingly larger, differing in size according to scale (we reduce such assemblages to their constituent entanglements and term the largest entanglements the meshwork (figure 2)), we maintain that they persist as principally local and historically contingent phenomena bounded by events and the situated practices of everyday life. Delimiting time in the past, nonetheless, as indicated above, is an enormously difficult task for archaeologists. Due to obdurate limitations constraining the final resolution of available evidence (archaeological, documentary, oral-historical, etc.), we argue that, for the most part, it is difficult – although not impossibleFootnote 9 – to archaeologically (even with the aid of numerous evidentiary sources) investigate events of a day or a week with their accompanying material residues (Robin Reference Robin2013, 7). By reassembling vibrant things into series of past events and the dynamics of everyday life we can begin to view the practices that operated within a landscape (Aldred and Lucas Reference Aldred, Lucas and Bolender2010, 197). We are, however, cautious and aware that no matter the extent of our efforts to present the archaeological record as a sinuous flow of constitutive events, it will always remain a fragmentary ‘palimpsest of residues of such events’ (Lucas Reference Lucas2012, 183).

In various places throughout the paper we have already made short references to case studies from our own research. Therefore, rather than talk a lot about ‘cups of coffee, institutional organisations, books in an academic’s office, Melanesian pigs, and the 2003 blackout in eastern North America’ (Knapp Reference Knapp, Pierce, Russell, Maldonado and Campbell2016, 245), we want to prove the applicable worth of reassembling assemblages of practice through two of our historical archaeological examples.

Assemblages of practice and fashionability on 18th-century La Tortuga Island, Venezuela Antczak’s (Reference Antczak2019) historical archaeological analysis of assemblages of dining and drinking practice at the site of Punta Salinas, by the salt pan of the Venezuelan island of La Tortuga, reveals significant changes through time in the early modern entanglement of seafarers with things. Beginning in the late 17th century and up until 1776, this desolate and uninhabited island belonging to the Spanish Crown became an unexpected and temporary annual gathering point for the captains and crews of dozens of Anglo-American ships that sailed there to harvest solar sea salt from its saltpan. Constrained by the island’s hostile desert landscape, the seafarers set up camp at Punta Salinas, turned into salt rakers, and interacted here with one another and the things they brought down on land for weeks on end.

In his research at Punta Salinas, Antczak recovered and identified a total of 790 individual vessels by performing meticulous minimum-number-of-vessel (MNV) counts, with vessels being then categorized by function. The abundant contextual archaeological evidence and faunal remains, as well as detailed historical documents relating seafaring practices and listing perishable items brought to the site, meant that, among other things, the assemblages of dining and drinking practice could be thoroughly reassembled. Among these identified vessels were 142 ceramic punch bowls. Antczak’s research reveals that specifically sea captains – who at Punta Salinas were unhindered by the four walls of a traditional seaport tavern and brought along their own crockery – had a unique opportunity to display their material possessions and fancy ingredients, many of which were associated with punch drinking. The assemblage of punch drinking at Punta Salinas sympathetically entangled the colourful ceramic bowls, their intoxicating and exotic contents (spirits or wines, citrus fruit, spice, sugar and water), and the diverse paraphernalia of punch drinking (ladles, punch strainers, nutmeg graters, etc.), with the revelling captains. In the resulting correspondence of punch, bowls and sea captains the vibrant ‘tavern’ by the salt pan not only enabled jovial socialization but also provided a stage on which captains could display their acquisitive power, interact with peers and construct their individual social identities (Antczak Reference Antczak2015).

Antczak determined that most of these ceramics, including the punch bowls, dated to after the late 1720s, a time when British industrial ceramics were becoming increasingly available and were in fact quickly incorporated into the sea chests of Anglo-American captains who often sailed back and forth across the Atlantic to Britain. These fancy and fragile ceramics effectively replaced the trusty and durable wooden and pewter shipboard wares used until then. Furthermore, creamware, a refined British earthenware, provided a clear case of change in the assemblages of practice at Punta Salinas. Creamware is the second most abundant ware type (107 individual vessels) at the site and could have only been brought there during a period of no more than 14 years. The earliest creamware entered the British market in 1762 and was dark yellow in hue, until in 1767 it was lightened (Miller Reference Miller2015, 1–2). A large part of the creamware from Punta Salinas is this early dark yellow. Moreover, the last known arrival of an Anglo-American ship at the island was in 1776. This large presence of early creamware in the assemblages of dining practice at Punta Salinas in the short 14 years between 1762 and 1776 is therefore a very compelling marker of the fashionable consumer choices and immediate purchasing opportunities of sea captains. In the 1760s creamware had effectively replaced most other ceramic wares in the sea captain’s chest, before the ‘creamware revolution’ swept through the British colonies of North America in the 1770s (Martin Reference Martin, Shackel and Little1994).

So reassembling the dynamic assemblages of practice from Punta Salinas and diachronically comparing them reveals that once Anglo-American captains began to acquire fashionable refined ceramic vessels in the late 1720s and early 1730s, they never stopped. These were binding and entrapping entanglements, creating relationships of enabling socio-economic dependence, but also of constraining acquisitive dependency. These largely footloose and untethered cosmopolitan consumers who constantly navigated spatial scales were through their consumer practices creating nested spatial relationships. At the campsite of Punta Salinas on the uninhabited island of La Tortuga, situated globalities in the form of fashionable British delftware punch bowls with their exotic alcoholic contents, or fresh-caught boiled lobster served on trendy creamware plates, became commonplace. Within these vibrant assemblages of dining practice, the global became conflated in the local.

Assemblages of practice and experiences of mealtimes in 19th-century Lowell, Massachusetts An example from Beaudry’s work in progress (Beaudry Reference Beaudryn.d.) invokes assemblages of practice as a means of comprehending meals and mealtimes as ‘total experiences’ drawing upon case studies of 19th-century mill workers and their supervisors and late 18th-/early 19th-century New England merchants. This involves evaluating in combination various categories of material things (e.g. ceramics, glass, bone, seeds, etc.) that have already been subjected to scientific and quantitative forms of analysis and reanalysing them qualitatively in terms of how they were used in combination to carry out projects in everyday life – for instance as both special and everyday rituals of dining – to gain an intimate understanding of bodily practices and engendered identities. This involves going beyond counts and percentages of seeds, bones, sherds and glass fragments to consider the ways in which the lines of evidence can be conceptually combined, something archaeologists are undertaking with increasing regularity (see, e.g., VanDerwarker and Peres Reference VanDerwarker and Peres2010). The aim is to establish the social context of meals by delineating where meals take place (setting); the sorts of food prepared and consumed; the material things deployed in serving, eating and fashioning the ambiance of the meal; and the ‘who’ of a particular meal – who is present, who dines, who serves, and why. Considering meals and mealtimes as ‘projects’ by following multiple lines of evidence (archaeological artefacts and other data, images, things in museum collections, documentary evidence and secondary sources, alongside insights gained through the efforts of people who prepare and cook food using period gear and foodstuffs) contextualizes and enlivens interpretations of the sensory aspects of preparing, serving and consuming a meal.

Beaudry and a team of researchers conducted the Lowell Boott Cotton Mills project in the 1980s. Relevant data come from excavations of 19th- and early 20th-century deposits associated with boarding houses occupied by unmarried unskilled operatives, as well as family-occupied tenements for skilled workers, housing for mid-level managers, and a duplex that housed the agents of the Boott and Massachusetts mills and their families (Beaudry and Mrozowski 1987a; 1987b; Reference Beaudry and Mrozowski1989). Assemblages of practice involving ceramics, glass, faunal remains and other food- and drink-related items differ across the various contexts; analysis focused on the nature and ambience of communal meal taking in boarding house dining rooms and looked for differences that may have arisen when Lowell’s early unskilled workforce of female (‘mill girl’) operatives was replaced by Irish and Eastern European immigrants after the middle of the 19th century (Mrozowski, Zeising and Beaudry Reference Mrozowski, Ziesing and Beaudry1996).

Archaeology, oral history and many other sources indicate that by the time the Boott Mills boarding houses opened in 1845, the city boasted many ‘warerooms’ offering furnishings for boarding houses for sale or rent, including furniture (beds, tables, chairs), eating utensils, crockery and glassware. Keepers tended to buy in bulk, especially when it came to dinnerware, cutlery and glasses; excavations turned up very few examples of refined earthenwares or colourful printed wares. These were so small in number that it seems likely that only the keeper had nicely decorated dinner- and teawares.

In the boarding house setting, domestic expectations as to dinner table comportment and the appropriate practices and manners of the dinner table were undermined at the very time when New Englanders and Americans more generally assigned important aesthetic significance to the dinner table. Sarah Josepha Hale wrote in her Reference Hale1852 manual, The ladies’ new book of cookery, ‘The TABLE, if wisely ordered, with economy, skill and taste, is the central attraction of HOME’ (1852, iii), conveying a clear sense of table and home as synonymous. At a time when ‘table aesthetics’ were being upheld as markers of civility and progress, the situation of the boarding house, potentially at least, fostered behaviours at odds with notions that table manners distinguished the civil from the savage. This has been immortalized in the phrase ‘boarding house reach’ as a shorthand for rude manners brought about by a free-for-all competition for a share of the contents of communal serving dishes as they were placed on the table.

Boarding house residents for the most part were served and ate from plates, dishes and bowls of plain, serviceable ceramic vessels, often of ironstone or other durable types of refined white earthenware. Residents of the tenements and of the agents’ and supervisors’ houses were family households and tended to select transfer-printed dinnerware, and each had a much greater number of specialty vessels that did not appear in boarding house assemblages.

Contemporary writings and documents strengthen interpretations of the archaeological evidence of boarding house life. Diet and food preferences were given moral weight, sometimes negative, sometimes positive – and debates around these issues played out in many of the cookery books and household advice manuals that proliferated in 19th-century America. Boarding house residents were fed well but fed differently than families living in supervisory and managerial housing. Foodstuffs, including meat, were purchased by boarding house keepers in bulk and broken down into manageable portions on site. At the boarding houses, meat tended to be stretched out in dishes such as stews, while skilled workers and supervisors consumed higher-quality meat, and families living at the agents’ house ate cuts of meat such as chops and steaks. Table settings varied by type of household, as did quality of foodstuffs and manner of preparation, but the actual components of the diet were highly similar.

Figure 3. A speculative comparison of the sensory aspects of dining at a Lowell boarding house, skilled-worker’s tenement and agent’s house, based on archaeological and archival evidence.

Figure 3 offers a comparison of the ways in which the sensory experience of mealtimes differed in the contexts of boarding house, tenement and agent’s house, aligning olfactory and auditory aspects of the meals to the material assemblages of dining practice. Up and down the scale of company housing in 19th-century Lowell, the ‘total experience’ of mealtimes involved highly different sensory experiences that served to construct and enact different roles, identities and forms of personhood. The materiality and sensoriality of dissimilar settings inscribed different values to different ways of consuming a meal, values that had very little to do with nutrition. The 19th-century expectation was that, ideally, group meals at regular times each day afforded a daily re-enactment of family life that reinforced family values among unrelated individuals. Dining in a boarding house on boarding house food was a form of enforced sociality that signified for unskilled workers a lack of social and economic mobility. It was otherwise for skilled workers and managers, whose ritualized family meals reinforced middle-class tastes through mannerly behaviour, polite conversation and a well-set table with carefully prepared foods served on decorated dishes.

Considerations on the process of reassembling assemblages of practice Reassembling assemblages of practice from the information available to archaeologists is invariably a meticulous, long-term and detailed abductive undertaking. We contend that the qualitative resolution of data necessary for reassembling assemblages of practice cannot be obtained through archaeological survey or quantitative sherd counts alone. Rather, all elements of the archaeological ‘toolkit’ available in each scenario must be sought and utilized, since such reassembling requires juxtaposing all available independent lines of evidence. These include contextual and depositional archaeological data; textual, visual, ethnographic and oral-historical evidence; and data derived from quantitative, computational, experimental, biological/physical, landscape and environmental archaeology; as well as archaeometry, GIS and archaeological science, among other things. The greater and broader the evidentiary detail available, the more vibrant the assemblages of practice that may be reassembled. Historical archaeology, and other archaeologies with access to textual and oral-historical evidence, are especially well suited for such an undertaking (Beaudry Reference Beaudry, Symonds and Herva2017; Beaudry and Symonds Reference Beaudry, Symonds, Beaudry and Symonds2010, xiii–xiv; Wilkie Reference Wilkie, Majewski and Gaimster2009, 338). When possible, performing minimum-number-of-vessel counts (MNV) where individual cross-mended vessels, not sherds, are categorized by function (Voss and Allen Reference Voss and Allen2010) is one way of enriching archaeological evidence to enable the reassembling of assemblages of practice. Finally, it must be underlined that reassembling assemblages of practice is in many ways a creative exercise (Marila Reference Marila2017) in ‘telling a story’ (Joyce Reference Joyce, Hicks and Beaudry2006, 61–64) using the ‘archaeological imagination’ (Shanks Reference Shanks2012) to create compelling, meaningful and memorable interpretations and presentations of the past not only for academics but also for the public(s) (Van der Linde, Van den Dries and Wait, Reference van der Linde, van den Dries and Wait2018).

We stress that no matter the evidentiary detail, the assemblages of practice we reassemble are never final, and are inevitably fragmentary and open-ended. They are never entirely the way events of human–thing entanglement occurred in the past. Rather, they are our speculative and abductive archaeological interpretations of often ambiguous data (Tringham Reference Tringham2018), and the vagueness and lack of clarity of these interpretations is in no way antithetical to the discipline (Marila Reference Marila2017; Sørensen Reference Sørensen2016). More so, we ultimately concur that if, to archaeologists, ‘the past is accessible at all, it is only through those venues that the archaeological affords’ (Nativ Reference Nativ2017, 672). Thereby, by marshalling all available evidence in a productive conceptual framework, assemblages of practice bridge data and theory and draw us nearer to scrutinizing the heart of past human–thing entanglements. They provide us with a heuristic with which we can make informed comparisons across space and time to shed new light on nagging questions of anthropological and archaeological import.

Concluding remarks

In summary, the notion of assemblages of practice charted in this paper is an effort to flesh out and provide methodological rigour to recent explorations of entanglement and correspondence by broadening the promising concept of assemblage. These and other terms are all too often either buzzwords sprinkled over archaeological evidence like magical pixie dust, or the focus of philosophical ruminations untethered from material realities and precariously far out at sea. Our conceptual framework originated abductively, by wrestling with the messiness and vibrancy of archaeological things and disorderly yet illuminating deep theory. We are well aware that developing the framework has been an exercise in what some archaeologists may negatively perceive as theoretical ‘borrowing’ (Pétursdóttir and Olsen Reference Pétursdóttir and Olsen2017). Deliberately, and perhaps controversially, we have sympathetically fitted together ostensibly disparate concepts from the social sciences and humanities according to their compatibilities rather than exclude them based on their perceived incongruencies. We do not present any new concepts, which is why ours is not a new theory but rather a new esemplastic conceptual framework where known concepts are revised and grounded in our definitional understandings (for example, our insistence on thing over object), woven together, and operationalized in a fresh way. In an increasingly atomized and insularized theoretical scene in archaeology,Footnote 10 such borrowing and bridge building are, however, to us inevitable and necessary to keep our discipline in step with humans and things, and we assure it continues to be actively provocative and relevant to our societies (González-Ruibal, González and Criado-Boado Reference González-Ruibal, González and Criado-Boado2018).

To us an assemblage of practice is a dynamic gathering of corresponding things entangled through human practice. The assemblage of practice is the nexus where humans and things become entangled through situated daily and eventful relations of correspondence. It is a conceptual framework and analytical tool that helps reveal changes, continuities and transformations in human–thing entanglements and not only their impacts on local and short-term sociocultural developments, but also their repercussions on phenomena of much larger spatiotemporal scale. We propose that, where data and evidentiary sources are propitious, framing archaeological analyses around assemblages of practice can only enrich our archaeological interpretations and discussions.

We do not pretend here to have reinvented the wheel or offered a theoretical and methodological master key that fits all archaeological data and suits all archaeologists. Assemblages of practice, as we have laid them out, require a particular set of detailed evidentiary sources to be effectively, albeit never completely or accurately, reassembled. Ours, however, is a proposal of bridge building in archaeology. The assemblage of practice aims to be a pluralistic, integrative and evolving middle-range conceptual framework. Where many see insurmountable theoretical differences, we see promising congruencies; while some may expend energy on fortifying entrenched and polarizing philosophical positions, we seek to foster dialogue in pluralism and build common ground. Clearly, in certain philosophical aspects we have taken a stance, and that may not be to everyone’s liking. However, we firmly believe that in a time of many turns, theoretical clarity, terminological precision and conceptual accessibility and applicability are necessary roads forward in our discipline.

Acknowledgements

We thank Joanna Brück for patiently curating the editorial process. We are also greatly indebted to two anonymous reviewers for their incisive and detailed critique which has greatly benefited this paper. Any responsibility for errors or opinions is solely ours. This work was supported by the Institute of Heritage Sciences (Incipit-CSIC).

Konrad Antczak’s current research focuses on the historical archaeology of 16th- to 19th-century commodities, seafaring mobilities and identities in the south-eastern Caribbean. In his research he explores the theoretical contours of human–thing entanglements, the itineraries of things, and assemblages of practice. Recent publications include Islands of salt. Historical archaeology of seafarers and things in the Venezuelan Caribbean, 1624–1880 (2019) and ‘The asymmetries of disentanglement’, a commentary in this journal.