The mention of Pashtunwali, a comprehensive body of customary laws, ethics, and etiquette among Pashtuns, has long become a commonplace in essays and academic studies concerning the political and social history of Pashtun tribes and their involvement in regional developments. However, even the works containing detailed recapitulations of Pashtunwali's basic components and ideologies generally describe it as a static model of required social behavior, without inquiry into its past. In available literature, the chronological framework of the function of Pashtunwali tenets in practice completely omits precolonial times, with coverage only beginning in the second half of the 19th century when the first publications of translated folklore and other original Pashto texts provided more clear insight into the Pashtunwali ethical principles most explicitly verbalized in poetry and proverbs.Footnote 1 That Pashtunwali tenets have never been systematically arranged in written form and early modern Pashto sources remain understudied accounts for insufficient knowledge of the historical evolution of Pashtun customary law and its particular legal institutions. Tom Ginsburg believes that the oral tradition of Pashtunwali prevents it from having a set of precise substantive norms and suggests that the elaboration of “a system of recorded precedent” could reduce the ambiguity of orally transmitted rules and transform Pashtunwali “from a code of honor into a real code of law.”Footnote 2

This article seeks to introduce a diachronic perspective to the studies of Pashtunwali by examining some early modern Pashto writings as primary sources of documented cases related to the nənawāte custom—a complex legal mechanism for conflict resolution. A discussion of these cases as notable historical precedents that employ Pashtunwali norms in everyday interactions between Pashtun tribesmen in the precolonial period may help to specify the nənawāte legal objectives and common procedural elements, as well as amend modern understandings of this custom and its significance for maintaining social order in the absence of state-imposed coercive instruments. References to Pashtunwali by early modern Pashtun litterateurs are very important for the reason that, unlike similar narratives of later times, they were not supposed to be the object of external investigation, and therefore were not intended to prove or refute any assumptions of outsiders. Pashto writings examined in the article reveal the intrinsic pragmatism of Pashtunwali and its genuine historical features, perfectly explaining why the oxymoronic modern description of it as a “social contract . . . at once more rigid than the dictates of Emily Post and more permissive than the Marquess of Queensberry Rules,” despite an ironic figurativeness, is not too far from the truth.Footnote 3

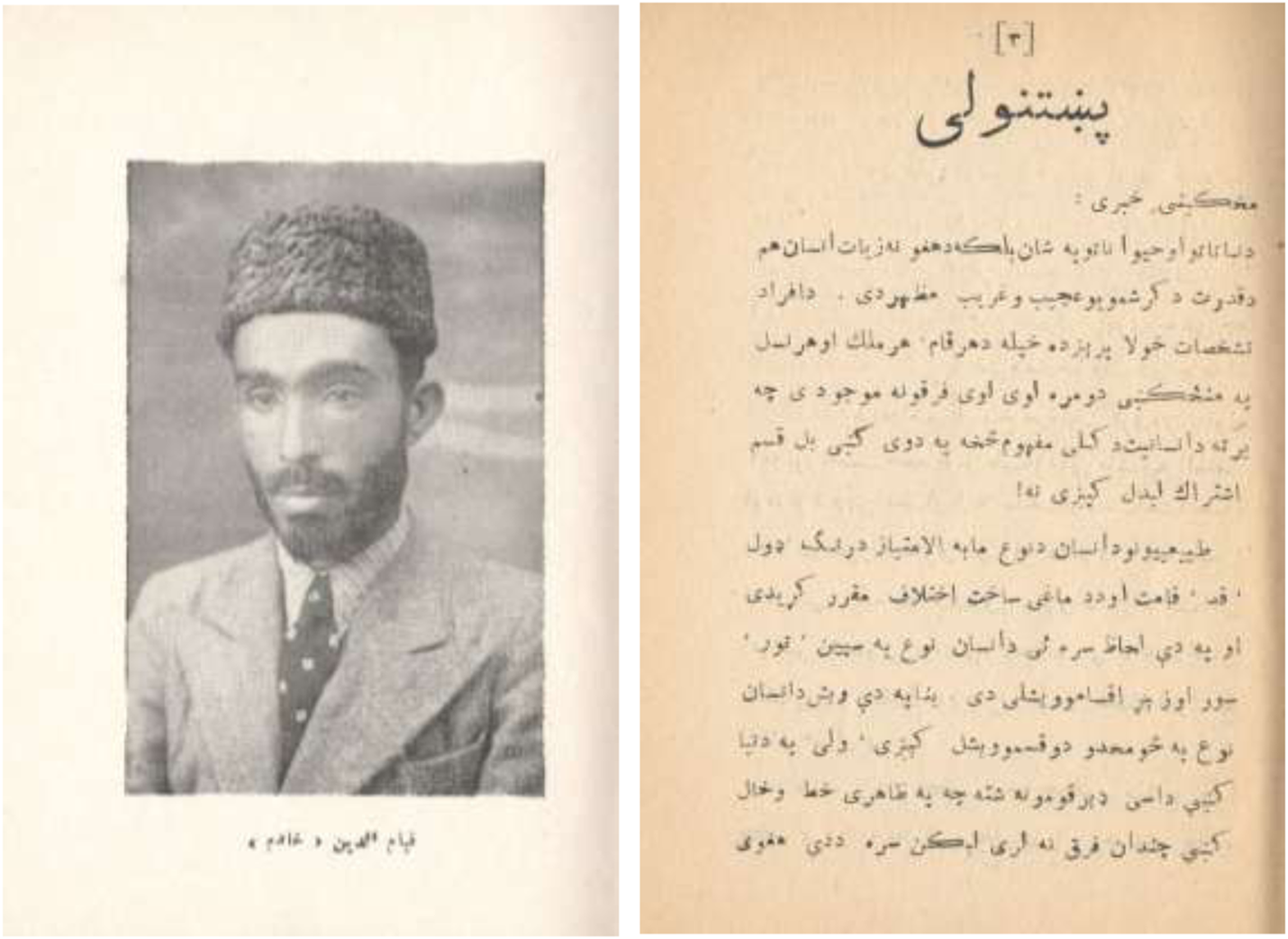

The literal meaning of Pashtunwali (“Pashtun-ness”) clearly indicates that this notion not only defines a set of social norms but also expresses the idea of self-identity.Footnote 4 This aspect of Pashtunwali was highlighted and conceptualized in the 1950s by the followers of the Awaken Youth (Wish Zalmiyan) political movement initiated by a group of Pashtun intellectuals and litterateurs. To foster ethnic solidarity by means of modern education, they “wanted to introduce a new set of ethics, some of them based on some elements of Pashtunwali.”Footnote 5 Very important in this respect was their attempt to verbalize and “codify” the Pashtunwali tenets in written form. Despite rather simplistic discursive phrasing, the pioneering didactic essays by Qiyam al-Din Khadim (1901–79) and ʿAbdallah Bakhtanay (1925–2017) not only outlined particular social practices, legal imperatives, morals, and values of Pashtunwali, but also accentuated their significance as an explicit manifestation of the Pashtun “national spirit” (qawmī rūḥ).Footnote 6 Whereas Khadim focused primarily on social and legal customs, Bakhtanay examined Pashtunwali ethical principles, which he equated with “doing Pashto” (paṡhto kawəl) and introduced, along with “speaking Pashto” (paṡhto wayəl), as a basic criterion of Pashtun identity (Figs. 1, 2). These and similar edifying works in Pashto published in the 1950s–60s stimulated later academic surveys of Pashtunwali in Afghanistan.Footnote 7

Figure 1. A photo of Qiyam al-Din Khadim (1901–79) from his book Pashtunwali (Kabul: Pashto Toləna, 1953); the beginning of the essay, page 3.

Figure 2. A photo of ʿAbdallah Bakhtanay (1925–2017) from his book Pashtani Khoyuna [The Pashtun Mores] (Kabul: Də Nashriyato Loy Mudiriyyat, 1955); the cover of the book.

On the other side of the Durand Line, regular discussion of the same ideas began a few decades earlier as part of the educational and political activities of the “Frontier Gandhi,” ʿAbd al-Ghaffar Khan (1890–1988), and his supporters, especially within the framework of the Servants of God (Khuday Khidmatgar) movement (1929–48). Mukulika Banerjee argues that the political doctrine of this movement incorporated a number of the ideological provisions of Pashtunwali reinterpreted for reconciliation with both Islam and Gandhi's nonviolence strategy.Footnote 8 Emphasis on Pashtun nationalism and Pashtunwali values with a more conventional perception, without allusions to the Hindu ideology of ahimsa, prevailed in the political message of the “Young Pashtun” (Zalmay Pashtun), an offshoot of Khuday Khidmatgar founded in 1947.Footnote 9 Ongoing social and scholarly discourses on Pashtunwali among Pakistani Pashto-speaking intellectuals do not seem to have resulted in any sort of systematic study, however the idea of Pashtunwali being tightly related to Pashtun identity has been constantly reasserted. Proclaiming that Pashtunwali and the Pashto language are two basic constituents of Pashtun identity, Raj Wali Shah Khattak, for example, compares the former to “the unwritten constitution” of Pashtun culture and reiterates his predecessors’ belief that, if not a religion, “it is a very sacred code of conduct.”Footnote 10

Scholarly Definitions of Pashtunwali

In his seminal work on Pashtun identity, Fredrik Barth confirmed the indigenous perception of Pashtunwali as its fundamental attribute and briefly discussed what he assumed to be three “central institutions” of “a body of customs which is thought of as common and distinctive to all Pathans,” namely hospitality (melmastyā), council (jirga), and seclusion of women (purdah).Footnote 11 Barth overlooked the very term “Pashtunwali” but mentioned its folk interpretation as “doing Pashto.” His understanding of Pashtunwali as the “native model” that provides Pashtuns with a “self-image” was elaborated later by Bernt Glatzer, who preferred the definition “ethnic self-representation” (or “Selbstportrait”).Footnote 12

The books by Akbar S. Ahmed (1980) and Willi Steul (1981) offered more detailed socio-anthropological analysis of Pashtunwali as both an ideal model and a living practice. These studies not only contributed to deeper examination of particular elements of the Pashtuns’ “common cultural code,” but also demonstrated its suppleness, adaptability, and regional character.Footnote 13 The study of Pashtunwali's psychological dimensions contemporaneously initiated by Charles Lindholm confirmed the necessity of differentiating Pashtuns’ ideal standards of conduct from everyday practices resting on interpersonal relations.Footnote 14 Developing this approach, Andrea Chiovenda in a more recent study even abandoned the term “Pashtunwali” in favor of its original meaning “Pashtunness.”Footnote 15 A new promising facet of Pashtunwali studies was addressed in the sociological research by Muska Haqiqat, who discussed ambiguities in the awareness and reception of ethnic cultural and social traditions among the Pashtun diaspora in present-day Germany.Footnote 16

Political realities of the 1980s–90s turned the complicated problem of the interrelations between Pashtun tribal customs and Islam into one of the most urgent issues.Footnote 17 As a reaction to cultural misunderstandings and ensuing operational complications faced by the mission of the International Security Force (ISAF) in Afghanistan (2001–14), surveys of Pashtunwali also appeared in military journals.Footnote 18 Among the works with more detailed overviews of the content and ideology of Pashtunwali, a summary by Lutz Rzehak may be recommended as the best introduction to the topic, as it offers the most methodical and balanced overall analysis of the Pashtuns’ system of values and societal guidelines, with indigenous construal and a diachronic perspective.Footnote 19

The prevailing scholarly definition of Pashtunwali as “the Pashtun traditional code of behavior,” quoted from Ludwig W. Adamec's dictionary, has a range of minor variations, which are scattered throughout Thomas Barfield's book.Footnote 20 The still popular figurative counterpart, “the way of the Pathan,” was coined by James W. Spain.Footnote 21 Spain also reaffirmed the 19th-century postulate that Pashtunwali was founded on three main “commandments”—badal (retaliation), melmastyā (hospitality), and nənawāte (asking for forgiveness or asylum). This triad, despite its logical inconsistency and the lack of a corroborative formal source, has been regularly called the cornerstone of Pashtunwali in various publications of the colonial period and, after Spain's essay, has been accepted almost as an axiom.Footnote 22

Since the 1970s it has been widely acknowledged that the essence of both moral and legal aspects of Pashtunwali is largely determined by the fundamental characteristics of Pashtun traditional society as a conglomerate of segmentary (tribal), acephalous (decentralized), and basically egalitarian communities.Footnote 23 This means that inevitable alterations of these characteristics (influenced by various effects of continuous, lingering integration, or “encapsulation” in Ahmed's terminology, of Pashtun tribal areas into state-regulated social environments) affect the practical application of Pashtunwali, changing the dynamics of the interplay between its ideal model and real-life implementation.

Without denying the role of Pashtunwali as a manifestation of self-identity based on a value system, one can fully agree with opinions of specialists in legal studies who assess its main pragmatic function as that of “a decentralized system for maintaining order” and “an effective conflict resolution mechanism.”Footnote 24 From this point of view, the key Pashtunwali concept of honor (nang) conforms well with the notion of personal status that must be constantly maintained and defended to ensure one's individual and one's family's survival.

The major obstacle to the analysis of Pashtunwali as a historical phenomenon that has evolved over time is the absence of an authorized written exposition or a corpus of systematized documented precedents. Although in both scholarly and nonacademic literature there are a large number of dispersed picturesque stories, often poorly distinguishable from legends and anecdotes, that tell of the practice of Pashtunwali tenets, these accounts hardly offer reliable material for compiling a coherent book of statutes. Primary sources on Pashtunwali always have been and remain predominantly oral. The recently abolished Frontier Crimes Regulation (1872–2018), which was intended to adjudicate criminal offenses among indigenous populations of the former Frontier in accordance wth Pashtun and Baloch customary laws, did not include any references to Pashtunwali or its provisions.Footnote 25

The authors of the first handbooks on Pashtunwali, composed in the 1950s, admitted that their essays were based on their personal life experiences, knowledge of folk traditions, and reading of the classical Pashto writings of early modern times. The earliest written source explicating rules of behavior required from educated Pashtun nobility is the didactic treatise in Pashto Dastar-nama (The Book of the Turban, 1665) by Khushhal Khan Khatak (1613–89). However, this book belongs to the “mirror for princes” (naṣīḥat al-mulūk) genre and is modeled after the Persian medieval exemplary essay Qabus-nama (1082) of Kaykawus ʿUnsur al-Maʿali, therefore it is not a rudimentary manual of Pashtunwali but a revision of Islamic pedagogical traditions and cultural values that prevailed within the Persophone ecumene by a learned representative of the Pashtun military administrative elite.Footnote 26 More consistent with the Pashtunwali ideology are some of Khushhal Khan's verses composed after writing Dastar-nama, as well as his miscellaneous records and diaries in prose, fragmentarily preserved in the historiographical compilation Tarikh-i Murassaʿ (The Ornamented History) by his grandson, Afzal Khan Khatak (1665/66–1740/41).

It is very likely that Khushhal Khan's political testament Wasiyyat-nama (The Testament), dated 16 March 1666 (10 Ramazan 1076) is the first extant document in which the term “Pashtunwali” (here paṡhtūnwāla) is mentioned. Among other admonitions, in this text the Khatak chieftain instructed his eldest son Ashraf Khan (1635–94) to care about the welfare of two friendly Yusufzay clans—Bayizay and Ranizay—“both in doing Pashtunwali (də paṡhtūnwāle pə kār) and serving the Mughals.”Footnote 27 His other statements concerning similar matters prove that in the 17th century Pashtunwali already displayed its ethnocentric nature as an identity marker in consequence of the growing political confrontation between Pashtun tribes and the Mughal imperial establishment.Footnote 28 On the other hand, in Khushhal's time Pashtunwali continued in its main practical function as a body of tribal customs. It was this function that was noticed by the British colonial official Mountstuart Elphinstone (1779–1859), who introduced “Pooshtoonwulee” as “a rude system of customary law” to European readership.Footnote 29

Khushhal Khan's works and other early modern writings in Pashto can help trace factual operation of Pashtunwali regulations in everyday practice in the era in which they had not yet become a subject of interest to outsiders—travelers, military staff, political agents, administrative officials, and scholars. A more careful reading of still understudied original Pashto sources allows us not only to outline the documented history of Pashtunwali in the precolonial period, but also to correct present-day interpretations of its ideology and tenets. These sources also may challenge some modern hypercritical definitions of Pashtunwali, such as “a great repository of Pashtun stereotypes if ever there was one.”Footnote 30

The Nənawāte Custom

Along these lines, Khadim and ʿAtayi explained nənawāte (pl. of nənawāta) as a ritualized legal custom of appealing for forgiveness to settle a conflict.Footnote 31 In modern scholarship it also is often interpreted as a mechanism of conflict resolution. However, the very meaning of this term (from nənawatəl, “to enter”) implies that originally it designated the practice of seeking refuge in another's homestead. This understanding is widely common as well, and in Adamec's Historical Dictionary nənawāte is defined as “the obligation to afford protection or asylum to anyone in need or assist in mediation to help the weaker in a feud who seeks peace with someone he has injured.”Footnote 32 Under the concept of the Pashtunwali “triad,” nənawāte is considered one of its key elements, and in James Darmesteter's explications “loi d'asile (nanavatai),” the law of asylum, precedes even “loi de revenche (badal),” the law of revenge, and “loi d'hospitalité (mailmastai),” the law of hospitality.Footnote 33

Varying definitions of nənawāte do not contradict each other but indicate that historically it is a complex legal custom that relates to three institutions: protection, mediation, and reconciliation. The primary legal objective of nənawāte is a peaceful settlement of a conflict resulting from damage to life, health, dignity, or property. In this respect, it works as an alternative to retaliation (badal): the status quo ante is restored through the established procedure of reconciliation rather than retaliation with equal or similar damage. Both Khadim and ʿAtayi, as well as many other authors, have rightly emphasized that in Pashtun tribal society nənawāte functions as an efficient legal instrument for maintaining social order without recourse to violence or resorting to external law enforcement. Badal is the lawful right of the injured party to retaliate, whereas nənawāte is the right of the guilty or accused party to avoid retaliation. The definition of nənawāte by Khadim and ʿAtayi posits a situation in which the guilty or accused party requests forgiveness and reconciliation directly from the injured one. The understanding of nənawāte as refuge implies that the guilty or accused first appeals for protection to a third party who later may or even must act as a mediator in the reconciliation process. In the early 19th century, Elphinstone understood the idea of “Nannawautee,” which he believed to be the most remarkable Pashtun custom, as a request for a favor that cannot be declined, and particularly a plea for help in a quarrel.Footnote 34 Lindholm also remarked that nənawāte “implies more than simple protection” and “can be applied as a lever to force a favor.”Footnote 35

The institutions of protection and mediation are sometimes regarded as independent of nənawāte. In ʿAtayi's dictionary, for example, these are introduced in separate entries as panā (refuge) and myāndzgaṙay (mediator).Footnote 36 The description of panā fully corresponds to what other sources identify as the refuge afforded under the rules of nənawāte. According to Rzehak, “the nənawāta ritual is based on the concepts of hospitality (melmastiyā) and asylum (panā kawəl).”Footnote 37 This echoes Olaf Caroe's opinion that nənawāte is an “extension” of melmastyā “in an extreme form.”Footnote 38 Although some elements of nənawāte and melmastyā do intersect, these customs certainly have different societal functions and legal characteristics. Whereas the former is the right to request protection, mediation, and reconciliation with the goal of resolving a conflict, the latter is the obligation to provide shelter and sustenance upon request without necessarily partaking in conflict resolution. Panā, from the Persian panāh, is clearly a conceptualization of one of nənawāte's original constituents. This approach accords with interpreting nənawāte in a narrower sense, as only a ritual of asking forgiveness.

Explanations of the nənawāte custom usually include notes on its specific ceremonial provisions and attributes. In the case of a conflict caused by a serious offense such as homicide, it is expected that resolution will be more effectively achieved through the mediation of men of religion (mullahs or members of spiritual lineages, stāna), elders and respected community leaders (spīnżhīrī, white-bearded), or women. The rejection of the appeal brought by these mediators on behalf of the offender may affect honor (nang), and thereby social status. Carrying the Qurʾan and bringing along sheep or cattle for slaying and collective consumption are traditional ceremonies often performed by the nənawāte supplicants or their intercessors. The payment of compensation (narkh) for the inflicted damage also may be included in the nənawāte ritual, although its legal framework and method of calculation share strong similarities with the payment of blood money (diya) according to Islamic penal law. In fact, narkh is an element of Pashtunwali that clearly testifies to the influence of Islamic legal doctrine (shariʿa) on Pashtun custom. In modern research, such elements are accepted as intrinsically pertaining to Pashtunwali, but the case of narkh points to the need for a more accurate historical approach. If the very idea of a material compensation for murder, bodily injury, or insult may have its origins in Pashtun ideology and custom, its fusion with particular Islamic norms was undoubtedly a long process that evolved unevenly over time in different tribal areas alongside Islamization.

Like Pashtunwali in general, the nənawāte custom usually has been discussed in academic literature as an ideal model: a standardized ritual with a set of widely acknowledged regulations, sometimes illustrated by semilegendary or plainly anecdotal cases. A typical example is quoted by Bruce L. Benson and Zafar R. Siddiqui “from an interview of a Mohmand tribesman.” In this story, a woman gives shelter in her house to bandits who have just killed her two sons in a raid on the village, and even demonstrates an intent to defend them by appearing with a gun in the doorway, explaining that “they have come Nanawatey to my house and are under my protection. I guard them over my life while they are in my house.”Footnote 39 David Edwards rightly identifies stories like these as “a common narrative motif in Pakhtun culture,” emphasizing that strict abidance with nənawāte and melmastyā principles is an important criterion for assessing “the virtues and merits of individuals.”Footnote 40 However, in the tribal story of a Pashtun informant recorded by Edwards, its main character, a “hero of the age,” Sultan Muhammad Khan, bluntly violates the “sacrosanct” principles of hospitality and protection.Footnote 41 A similar incident is said to have led to a great tribal uprising against the British in Waziristan in 1897.Footnote 42 A more recent and officially documented case of the murder of a supposed “guest,” a Canadian junior officer, during an ordinary tribal meeting in the Qandahar province in March 2006 motivated Major R. T. Strickland to address the issue of the “limited understanding” of Pashtunwali in an article written for the Canadian Army Journal.Footnote 43 Such real-life cases, devoid of any romantic connotations, prove that the actual practice, historical development, and true emic perception of Pashtunwali customs and principles require more detailed analysis to correct a monochrome picture of an imagined ideal model of Pashtun behavior.

The nənawāte custom deserves more thorough investigation because of its authentic tribal origin, complex legal nature, and particular significance as an effective mechanism of conflict resolution. Having definitive pre-Islamic roots, this mechanism is still widely used among Pashtuns; nevertheless, in view of the dearth of scholarly studies on the topic, its nature and history have been traced principally through sporadic and passing remarks in recorded stories about everyday life experiences in Afghanistan and Pakistan. In such stories, nənawāte is often mentioned as a routine practice. For example, in a story told to Chiovenda by a young Pashtun man from a rural district in Nangarhar province, nənawāte appears to be a common means of avoiding a serious conflict over land. The young man's grandfather, the elder of his family, decides “to go nanawatay” after his relatives, protecting their farming land, have wounded four members of another Pashtun family in a firefight. The incident occurred sometime in the 2000s. No details about the nənawāte are reported in the story, except the informant's comment that appealing for reconciliation under the nənawāte rules does not necessarily involve a damage to the guilty party's communal status or reputation.Footnote 44 In two cases recorded by Ahmed during his fieldwork in the Mohmand Agency (Pakistan) in the mid-1970s, the nənawāte rules were applied to prevent the escalation of conflicts. One of the conflicts arose from a petty brawl over a lost snuffbox; another was caused by a misunderstanding about the loan of a ferryboat and almost became a large-scale clash between two village communities. In both cases, details of the nənawāte procedure are not provided. But if in the first one the nənawāte appeal was finally accepted with difficulty through the mediation of village elders and ensuing nervous, two-day talks about compensation, in the second one the nənawāte tactic apparently failed, as aggravation of the dispute led to the interference of the local police.Footnote 45

Although the nənawāte custom continues to be operative in the Pashtun homelands in Afghanistan and Pakistan, it is among those Pashtunwali tenets that are less known among non-Pashtuns and Pashtun diasporas. According to a sociological study by Haqiqat, the majority of present-day Pashtun migrants in Germany are not at all aware of the term nənawāte, although the general concept of a specific reconciliation procedure without recourse to official jurisdiction is familiar to some of them. Without knowing of the custom itself, one of Haqiqat's interviewees, for example, recalled a nənawāte case that happened in Qandahar. After the death of a ten-year-old boy in a hit-and-run accident, the guilty driver escaped and appealed for protection and mediation to a third party who helped achieve a peaceful agreement by which the former was to pay to the boy's family compensation, consisting of a plot of land and ten slaughtered sheep, the number of animals symbolizing the age of the perished child.Footnote 46

The Case of Adam Khan and Durkhaney

Although Elphinstone's remark on “Nannawautee” still remains a starting point for scholarly inquiries into the past of this custom, early modern sources in Pashto allow us to trace its practical application in the period prior to the foundation of “the Kingdom of Caubul” in the mid-18th century. Occasional mentions of nənawāte in these sources are similar to those in contemporary essays and life stories in that, being also cursory and brief, they detail neither procedural nor legal aspects of the custom. However, these brief mentions reflect the firsthand experience of Pashtun tribesmen, in their traditional segmentary society unaffected by modern nation–state political and administrative ideologies, and help to fill lacunae in the documented history of Pashtun social and legal traditions.

One of the earliest mentions of nənawāte has been preserved in the famous folk legend about Adam Khan and Durkhaney. A version of this tragic love story recounted by Elphinstone as told by an “Afghaun” informant has little in common with popular Pashtun variants of the legend and misses a crucial episode in which the main characters resort to the nənawāte custom.Footnote 47 But, in another case, it is this episode that provides a basis for the plot of two short poems of the Pashtun folk poet Burhan, recorded in 1886–87 by Darmestster.Footnote 48 These literary pieces well exemplify the spirit of Pashtunwali (here paṡhto kawəl), but the term nənawāte is not found in the original Pashto texts.

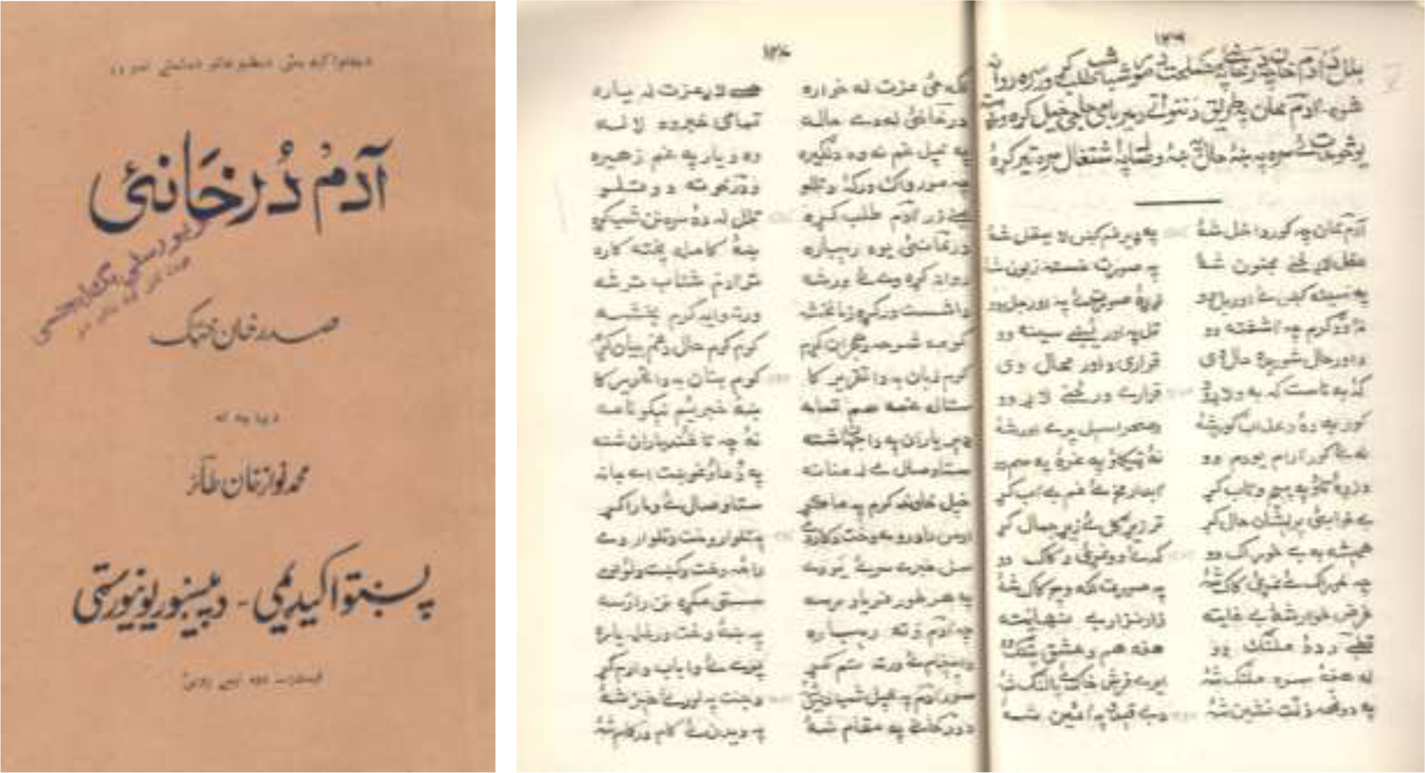

The first and now classical written version of the legend was composed in 1706/7 in the form of a masnawī poem (about 2680 distichs) by Sadr Khan Khatak (b. ca. 1654/55, d. after 1712), Khushhal Khan's son, whose mother was a daughter of the Yusufzay chieftain from the Bayizay clan (Fig. 3). Sadr Khan's descent is to be taken into account as the legend also was of Yusufzay origin, and the poet had close ties with his mother's relatives and fellow tribesmen. In the introduction to the poem, Sadr Khan relates that the story of Adam Khan and Durkhaney was extremely popular among the Yusufzay bards. Based on true events, which had occurred most likely toward the end of the 16th century, it circulated in different variants. The version Sadr chose for his poem was related to him by a certain Tatay, a great connoisseur of poetry, who purportedly had heard the story from the son of Mirogay, a friend of Adam Khan and a direct participant in the events.Footnote 49 Of course, the poet may have deviated from the original plot of the tribal drama by either ignoring or not accentuating some facts, considered by him too mundane or questionable for a work of belles lettres. Nevertheless, Sadr Khan's poem retained all the key episodes of the story, and included the reference to nənawāte.

Figure 3. The cover of the first edition of the poem by Sadr Khan Khatak (d. after 1712), Adam Durkhaney (Peshawar, 1959); the beginning of the poem's section with the nənawāte episode (pages 126–27).

The story goes that Adam Khan and Durkhaney—passionate lovers from the neighboring Yusufzay clans—took advantage of the nənawāte custom after their illicit relationship was exposed to the girl's family.Footnote 50 The main obstacle to a rightful and socially acceptable outcome of their romantic liaison apparently was Durkhaney's official engagement to another man, whom she did not love. This important circumstance is mentioned by Sadr Khan in passing in the episode telling of the first clandestine rendezvous of Durkhaney and Adam Khan: when the latter sneaks at night into Durkhaney's chambers, the half-asleep girl takes him in the darkness for her betrothed Payaway and reveals her dislike for that man in a few berating words. Also in passing, the author of the poem informs the reader that by that time Adam Khan already had a “beautiful wife” (ṡhkəle mankūḥa) named Tutya, but this sensitive detail in no way impinges on the plot of the story.Footnote 51 One day, a secret visit of Adam Khan to his beloved was disclosed by her male relatives and nearly ended with a bloody fight. Durkhaney insisted that Adam Khan should flee and not risk his life. After this incident, Durkhaney was not severely punished by her family, as may have been expected in light of later and modern interpretations of Pashtunwali norms, but only had a difficult conversation with her mother who finally appreciated her daughter's feelings and forgave her, displaying motherly wisdom in the words, “What has happened has passed; what has passed is forgotten.”Footnote 52 Moreover, it was Durkhaney's mother who found a solution to the trouble, giving her daughter permission to run away with Adam Khan.Footnote 53

The lovers made their escape and took refuge in the manor of Mirbamay, a powerful khan of the Hajikhel clan, who, according to Taʾir's commentaries, is even introduced in some folk versions of the story as the father of Adam Khan's first wife Tutya. Sadr Khan writes that late at night Adam and Durkhaney “brought nənawāte to the house of Mirbamay.”Footnote 54 Abiding by hospitality laws and demonstrating his status as a wealthy khan, Mirbamay provided the fugitives with a mansion (sarāy) and strong guard. This turn of events made the reprehensible love affair widely known and discussed at tribal assemblies. Compelled to respond to this insult, the clan of Durkhaney's betrothed Payaway—the Khasikhels—preferred to resolve the conflict by bribing Mirbamay and taking the girl away without fuss. In the poem, Mirbamay explains his consent to the deal with the Khasikhels and his breaking of the Pashtunwali principles as follows: “Honor and reputation (nām-u nang) are a futile boast; gold (zar) ensures respect and prosperity. The one who turns his face to honor and his back to gold is a mad man. I am not unripe, nor crazy, nor deprived of mind to reject gold, begin a feud, and lose my brothers for futile honor.”Footnote 55 In a meditative digression, Sadr Khan then discusses a common dichotomy between honor and wealth, coming to an honest if pessimistic conclusion, “Honor is strong among Pashtuns, but they ruin it by money.”Footnote 56

To accomplish his part of the deal, Mirbamay sends Adam Khan with a group of young men to escort a cattle drive, and when Durkhaney is left alone hands her over to the Khasikhel envoys, who deliver the girl to Payaway's house. Adam Khan learns about this treachery on the way back, but does nothing against Mirbamay except for harshly cursing him. Then he has to return home and soon falls ill with a fatal disease, reportedly caused by love pangs. In a later poem by the folk bard Burhan, the violation of the nənawāte rules by Pirmamay (Mirbamay), which is central to the plot of the story, ends with a more dramatic finale. Pirmamay's son Gujar Khan kills his father for the betrayal that “disgraced generations of Pashtuns.”Footnote 57 Sadr Khan's earlier and calmer version of the story seems to have been closer to the historical truth than Burhan's purposely scenic account, illustrating how a tribal story can be adorned over time with enthralling details.

In the story, the nənawāte custom is presented as a means of obtaining shelter and protection. However, one may imagine that Mirbamay was subsequently expected to play the role of mediator in settling Adam Khan's conflicts with Durkhaney's relatives and the family of her betrothed. The fact that nənawāte is used in this story to protect the doubtful relationship between unmarried individuals contradicts modern precepts that this custom is not applicable in cases involving any presumed offense against a woman's status and dignity (nāmūs).Footnote 58 It should be noted that in Sadr Khan's poem the term nənawāte also is employed figuratively to mean coming in supplication to ask a favor. For example, the phrase “I have come by nənawāte” is pronounced by the mother of the bride-to-be, Basey, when she pays a visit to Durkhaney's father asking him to permit his daughter to attend the wedding celebration.Footnote 59 In the episode when Adam Khan secretly steals into Durkhaney's house at night with the help of his friend Mirogay, the latter tries to persuade an awakened servant, Bucha, to let them in by suborning him and rather cynically asking him to accept their intrusion as nənawāte.Footnote 60 These uses of the term recall Elphinstone's explanation of its core meaning as an insistent request for a favor.

Nənawāte in “The Khataks’ Chronicle”

The prevalence of the nənawāte custom among Pashtuns in early modern times is more convincingly attested by occasional references to it in the narratives constituting “The Khataks’ Chronicle” (Ẕikr də Khaṫak də oləs), a collection of records by Afzal Khan Khatak and his grandfather Khushhal Khan in the corpus of the Tarikh-i Murassaʿ. As a rule, the Khatak chieftains refer to this custom using the expression pə nənawāte rātləl (“to come by nənawāte”) without going into details about its legal and procedural aspects.

Many nənawāte cases in the accounts of the “Chronicle,” which cover the period from the late 16th century up to 1724, are unambiguously related to the practice of appealing for protection. For example, in the autumn of 1673, after the official declaration of his disloyalty to the Mughal authorities, Khushhal Khan dispatched his family by the nənawāte rules to the southern areas of the Khatak domain under the protection of the Taray and Bolaq clans. At the end of the winter of 1682, Khushhal's sons ʿAbd al-Qadir Khan and Shahbaz Khan took refuge by way of nənawāte in the house of their brother, Yahya Khan, when their nephew and rival, Afzal Khan, for a short period seized administrative power in Saray-Akora (present-day Akora Khattak, Pakistan), the residence of the Khatak rulers. In March 1724, after losing a battle with Afzal Khan for political leadership in the tribe, the Khatak shaykhs Qiyas al-Din and Muhammad Ghiyas escaped with their families to Nawshahr (present-day Nowshera) where under the nənawāte rules they obtained shelter and protection from a certain Hasan Khan.Footnote 61

In the late 1670s, chieftains of the Bangash Malikmiray clan came by nənawāte to Khushhal's eldest son and Afzal's father Ashraf Khan, the Khatak ruler at that time, to ask for protection against the other Bangash clans and local tribes who were encroaching on their lands. Afzal states that Ashraf Khan very unwillingly accepted nənawāte from the Malikmirays, his old enemies, since this was against his own interests and entailed a risk of conflict with the Mughals. Describing the scene in which the Malikmiray khans come by nənawāte to Ashraf Khan in a place named Bagh-i Sharif, Afzal writes that Laʿl-Beg, one of these khans, stood in front of Ashraf in a pose of submission (lit. “with his hands on his belly”), weeping and saying, “Today is the day of our reward whether you kill or defend us.”Footnote 62 Under the nənawāte agreement, Ashraf Khan provided the Malikmirays with a safe passage through the Khatak territories and granted them a part of the Shagey district for temporary accommodation. He also fulfilled his hospitality obligations by sending to the Malikmirays rich gifts—“five hundred rupees, many rams and cows, and a large number of sheep.”Footnote 63 This nənawāte case is particularly noteworthy since refuge is given here not to an individual or several supplicants, but to a large tribal group.

A brief mention of nənawāte as an instrument of reconciliation is found in Afzal Khan's account of events in the winter of 1705–6. Due to the weakening of his position in the ongoing conflict with his political rivals in the tribe, Afzal Khan was forced to move his family to the village of Jalbey located in the northern areas of the Khatak domain, on the border with the Yusufzays. A neighboring Yusufzay clan of Kamalzay, who had always had complicated relations with the Khatak chieftains, soon tried to expel Afzal's family from the territory. According to Afzal, the Kamalzays first planned to set a fire to Jalbey, but then opted for cattle rustling. The Khataks took retaliatory action. The conflict stopped only after the Kamalzays lost too much property in mutual forays. Afzal writes, “At last they understood that they are ravaged. So they came to me by nənawāte and made a peace agreement (rogha).”Footnote 64

In the long narrative about the political conflict between Afzal Khan and the Khatak shaykhs in 1724, the nənawāte custom is mentioned twice: in one case as a realized and in the other as a proposed form of dispute settlement.Footnote 65 After the shaykhs Qiyas al-Din and Muhammad Ghiyas took refuge under the nənawāte rules in Nawshahr by Hasan Khan, they allegedly appealed with a written request for mediation to the aforementioned Kamalzays, who at the time were Afzal's allies: “We committed a great fault. If there is a way for us to reach reconciliation [with Afzal] through your mediation, we would bring you our nənawāte.”Footnote 66 Afzal recounts that the Kamalzay chieftains persuaded him to make a peace agreement with the shaykhs, and he even consented to give the latter a special honor: he personally came over to Hasan Khan's house in Nawshahr and secured the safe return of the shaykhs to the Khatak lands.

However, a few months later, the conflict between the Khatak chieftains and shaykhs flared up with renewed vigor and prompted the intervention of a number of high-ranking religious figures from Peshawar. Afzal Khan began to negotiate the possibility of reconciliation by using the nənawāte procedure again. This time he tried to coax some leading Peshawar theologians and spiritual teachers into acting as mediators on behalf of Sarfaraz-Gul, the head of the Khatak shaykhs. Afzal promised that he would accept the nənawāte of the shaykhs if it was offered to him by the renowned men of religion.Footnote 67 Although he asserts in the “Chronicle” that the theologian Akhund Qasim, an influential individual and the author of the popular Pashto religious handbook Fawaʾid-i Shariʿat (Benefits of Shariʿa), agreed to take part in the mediation process, it seems very unlikely that the reputable spiritual leaders of Peshawar were eager to be involved in resolving an infamous and legally dubious dispute between the Khatak elites. Additionally, Afzal's initiative was undoubtedly doomed to failure from the outset because it implied that Sarfaraz-Gul and his adherents had to plead guilty and resort to the nənawāte custom under external pressure despite the fact that they publicly declared themselves the injured party and obtained wide support among the Mughal authorities and local tribes.

As an expedient but unrealized option of settling disputes, the nənawāte custom also is referred to in the account of wars led by Khushhal Khan in the 1650s against the Yusufzays. It is said here that the large-scale armed conflict between the tribes could have been averted if the Yusufzays had come to Khushhal Khan by nənawāte.Footnote 68 Of course, the narrator, Afzal Khan, expresses the Khatak chieftains’ point of view, that is, that it was the Yusufzays who had to seek reconciliation and forgiveness as the guilty party, and not vice versa.

An interesting nənawāte case is reported by Afzal in the story of his clashes with a certain Atash Mastikhel in 1681/82. When Afzal was about to launch an assault on a Bangash village where his enemy was hiding, a group of local women came to him by nənawāte to inform him that Atash had already left their village and to propose an agreement whereby Afzal would abandon his plan of attack and the villagers would pledge never to let Atash in.Footnote 69 Apparently, the Bangash villagers had earlier provided refuge for Atash Mastikhel under the same nənawāte regulations. This episode of the “Chronicle” is unique in its description of the role of women as the nənawāte mediators.

In a few cases, the nənawāte custom is mentioned in the “Chronicle” without specifying its actual purposes. For example, in the account of his conflict with the Bangash chieftain Qabil Malikmiray, who in 1706/07 committed a betrayal and sided with his political adversaries, Afzal Khan expresses resentment against Qabil in the phrase, “Even though many times he came to my house by nənawāte and burdened me with his numerous troubles, now what a villainy has been exhibited by him!”Footnote 70 These “numerous troubles” may have been requests for both protection and mediation in disputes. Two years later, Qabil appealed by nənawāte for mediation to Afzal's uncle Najabat Khan, but this time his request was followed by a truce between him and his rival Ismaʿil Khan, another Bangash chieftain.Footnote 71

Some details of the nənawāte ritual are provided by Afzal Khan in the story of his peace agreement in 1713 with the Radzars, a Yusufzay subdivision partly affiliated with the Khataks. According to Afzal, in earlier armed confrontations between the Khataks and a coalition of local Pashtun tribes, the Yusufzay-Radzar fighters had committed robberies and homicides with excessive cruelty. Afzal maintains that this is why he decided to take revenge on them, although his passing remarks hint that he considered the Radzars the better object of retaliation because they were weaker than the others and had no blood relationships with the Khataks. To prevent his revenge, the Radzars appealed for mediation to the Yusufzay Kamalzays, who then had family ties with the Khatak chieftains. The term nənawāte does not occur in the narrative, but the author employs instead the Pashto idiom “to throw at the feet” (tər pṡho preīstəl or pṡho-ta rāwustəl) which means “to bring a guilty to repent.”Footnote 72 Afzal writes, “Jalal and Mahabbat, [the Kamalzays], were mediators. They threw the Radzars at my feet. The latter swore an oath (qasam) and asked forgiveness (istiʿfā)—first confidentially (lit. “among friends”), then publicly (lit. “in the yard”). I forgave them and said, ‘Well, I shall take the revenge of the Khataks on the Muhmandzays, but only for the sake of Jalal and Mahabbat, and because of [your] public disgrace (lit. “shame of the yard”).’ Then I displayed my hospitality to them. I gave each one a turban according to his rank (qadr) and let them go.”Footnote 73

This story presents a typical pattern of the nənawāte process as a means of conflict resolution. The resort to nənawāte here seeks to prevent retaliation for a series of murders and consists of two interconnected actions: an appeal of the guilty to the third party for mediation and a ritual of repentance of the guilty. The repentance is defined by the idiomatic expression that suggests that the guilty was supposed to beg for mercy kneeling down or bowing low in front of the aggrieved. An important constituent of this ritual in the case of a serious felony was the public demonstration of shame and humility of the guilty. It is the “shame of the yard” (sharm də gholī)—an acknowledgment of guilt and plea for forgiveness in the open—that becomes a decisive factor in Afzal Khan's agreement to the reconciliation with the Radzars (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. The nənawāte scenes from the feature film Jirga (2018, dir. Benjamin Gilmour, Felix Media). In the first photograph a former Australian soldier (Sam Smith, right) returns to an Afghan village to ask for forgiveness from a widow (Arzo Weda, left), whose husband he mistakenly killed three years earlier on a mission against the Taliban. The widow, stricken with grief, entrusts the killers’ fate to the village jirga, which pardons him according to the decision of the widow's adolescent son. The guilty soldier performs the nənawāte ritual, kneeling both before the widow at the door of her house (in private) and, in the second photograph, in front of the jirga in the village square (in public).

Another significant element of the nənawāte procedure in this story is the taking of an oath by the guilty party. Afzal Khan's other accounts indicate that as a rule the oath of reconciliation was sworn on the Qurʾan. In the narrative about his recurring conflicts and short-lived peace agreements with his younger brother Namdar and uncles ʿAbd al-Qadir Khan and Shahbaz Khan in 1710–13, Afzal cites the oath of ʿAbd al-Qadir (b. 1653, d. after 1713), who was among the leading Pashto litterateurs of that period: “In the future, I shall be faithful and honest. I do not deserve an allowance (rūzmāhyāna). I shall be occupied with books and keep loyalty.”Footnote 74 In some cases, an oral oath might be accompanied by a written one (ʿahd-nāma). A short text of such a document, composed by Afzal's uncles, is quoted in the “Chronicle,” as follows, “The generosity of the Khan is great. Let our former wrongdoings be forgiven. In the future, we shall do nothing else but care about faithfulness, allegiance, and concord.”Footnote 75 Although Afzal nowhere in these accounts refers to the nənawāte custom, it is very likely that peace agreements were concluded within its framework. In one case, Afzal's uncles, before appealing for reconciliation, take refuge in the house of a certain Shaykh Muhammad Fazil and obviously try to engage him as a mediator. According to Afzal, they brought repentance (tawba) to him “with great humiliation” (pə ḋere khwārəy) and in their oath even used a vulgar idiom, “If we reject your friendship, we shall smear our beards with dog excrement” (that is, we shall be disgraced).Footnote 76

Both an oath and humiliation are present in the nənawāte procedure related to Afzal's peace agreement with shaykhs Qiyas al-Din and Muhammad Ghiyas in 1724. Afzal describes his meeting with these shaykhs in the house of Hasan Khan in Nawshahr as follows, “Disgraced Qiyas al-Din could not raise his head in shame. But Muhammad Ghiyas, such a silly and mindless windbag—did so many bad things and now, more than before, cherished hope for our kindness and mercy as if he had fought on our side—he chuckled at every word. He made oaths. He talked all kinds of nonsense. A man with no mind and no shame!”Footnote 77 The humble position of Laʿl-Beg Malikmiray, who in the late 1670s by way of nənawāte beseeched Ashraf Khan for refuge, is highlighted by Afzal, who states that at the moment of supplication the former stood in a pose of submission, and even wept, as previously described.

The ritualized form of asking for forgiveness with a symbolic demonstration of humility and submission to the injured party's will is mentioned in a story retold by Afzal, taken from the records of his grandfather Khushhal Khan. In this event from the life of Khushhal's great-grandfather Malik Akoray, the latter comes to the Peshawar governor Shah-Beg Khan in person, without mediators, to repent for the murder of the governor's brother. Malik Akoray's full submission to the will of the governor is expressed in his words, “This sin is committed by me. Now I came to you [with] knife and shroud (chāṙə aw kafan darlara rāghləm).”Footnote 78 Allegedly impressed by this noble deed, Shah-Beg Khan spared the Khatak chieftain and even gave him a robe of honor (khilʿat) and some money, but at the same time warned that in retaliation for his brother's blood he would send the Mughal troops to raid the Khatak settlements. According to the “Chronicle,” these raids were very fierce and caused many casualties on both sides. It is emphasized in the “Chronicle” that Malik Akoray went to Shah-Beg Khan with repentance only under pressure from his tribe, because it “was not strong yet at the time” (i.e., in the late 16th century). His repentance by voluntarily bringing himself to the trial of a Mughal administrative official did not result in reconciliation, and probably for this reason it is not called nənawāte in the Pashto text of the source. The expression “to come [with] knife and shroud” may be interpreted in the text both literally and figuratively as an idiom meaning “to surrender to someone's justice.” The idiom may well have been based on an ancient practice in which the repenting guilty would actually bring a blade and a winding sheet.Footnote 79

In a more extravagant and humiliating version of demonstrating repentance for a felony, blade and shroud could be replaced with other symbols of submission to the will of the injured party—a rope on the neck and grass between the teeth of the guilty, signifying a sacrificial animal. Khadim states that these attributes of the nənawāte procedure have survived to modern times, but Steul and Rzehak remark that the practice of using them is known only from folk traditions.Footnote 80 There is not enough evidence to prove the historicity or prevalence of this practice over the centuries, but the earliest recorded source is likely the memoirs of Zahir al-Din Muhammad Babur (1483–1530). After a skirmish with Pashtun tribesmen on the road between the towns of Kohat and Hangu in January 1505, Babur left the following note, “We had been told that when Afghāns are powerless to resist, they go before their foe with grass between their teeth, this being as much as to say, ‘I am your cow.’ Here we saw this custom; Afghāns unable to make resistance, came before us with grass between their teeth.”Footnote 81 However, “The Khataks’ Chronicle” does not provide evidence that this ritual was used by Pashtuns in later times.

Conclusion

Since the first attempts of European scholars and administrative officers in the 19th century to summarize the essence of Pashtunwali, the nənawāte custom has been routinely identified as one of its three pillars, the other two being retaliation and hospitality. In the mid-20th century, Pashtun intellectuals shifted emphasis to the function of Pashtunwali as an ethnic identity marker. However, hardly any available essay on Pashtunwali can claim to be a fundamental study of its interconnected legal, ethical, and etiquette elements with a clear distinction between ideal norms and flexible practices, tribal legacy and Islamic influence, inner local specificities and imprints of external administrative pressures. The history and evolution of Pashtunwali ideology and institutions, especially in precolonial times, remain little researched. The absence of inquiries into the historical precedents of the custom of nənawāte also accounts for the uncertainty about its primary legal meaning.

The earliest authentic data on practicing nənawāte and other Pashtunwali customs in the Pashtun tribal areas may be extracted from a number of early modern Pashto writings, foremost the original narratives by the Khatak chieftains Khushhal Khan and Afzal Khan in the Tarikh-i Murassaʿ. These texts indicate that in the 17th and 18th centuries the idea of nənawāte included several legal actions pertaining to conflict resolution procedures. The right of “coming by nənawāte” meant that the guilty, or accused, or weaker party to a conflict could initiate its settlement by appealing for reconciliation directly to the injured party, or for protection and mediation to a third party. Direct appeal to the injured party implied asking forgiveness, that is, unconditional recognition of guilt, which in the case of a serious felony required ceremonial repentance with public demonstration of humility, and sometimes swearing an oath. Seeking protection from a third party was a means of avoiding immediate retaliation or aggravation of conflict, and did not necessarily presume pleading guilty in the future. This is why nənawāte is still often understood as simply taking refuge. A protector was generally considered a potential mediator, but the mediation also could be performed by other individuals. The Khatak authors write that the involvement of reputed men of religion in mediation procedures was a common tradition but not a rule, and laymen with high social status, tribal elders or nobility, regularly acted as mediators. Only in one story is mediation performed by women. The popular legend about Adam Khan and Durkhaney, versified by Sadr Khan Khatak, challenges modern precepts that nənawāte is not applicable in cases involving reprehensible gender relationships that can be interpreted as assaults on a woman's, and therefore her male relatives’, honor. Normally, employing nənawāte should not entail any substantial damage to one's honor. However, the Khatak authors’ narratives attest that tribal aristocracy preferred to avoid being in the position of those asking for protection or reconciliation, as this was perceived as “losing face” because of admission of both guilt and the need for another's help. The nənawāte agreements, like other deals, first and foremost those related to sociopolitical matters, were often short-lived, their survival being dependent on considerations of expediency.

On the whole, the Khatak chieftains’ records prove that resorting to the nənawāte custom was an ordinary, everyday practice among Pashtuns in early modern times. Regulating a number of particular legal interactions in conflict situations, this custom developed from an insistent ceremonial request of a conflicting party for a favor. Contrary to stories about exciting nənawāte cases in colonial and later times, the narratives from “The Khataks’ Chronicle” appear to be closer to real life, describing the operation of this custom as a routine procedure devoid of any romantic connotations or captivating details. The historicity of the facts reported by the Khatak authors about nənawāte and other Pashtunwali customs is seen through their generally pragmatic attitude to legal and ethical imperatives that make up an ideal model of behavior but nonetheless must serve practical purposes.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses his sincere appreciation to the readers of the article's draft and the IJMES editors for their valuable comments, suggestions, and corrections.