The first Spaniards in the central Andes found a socio-political landscape organized around ayllus (e.g. Cieza de León [1554] Reference Cieza de León2020; de Matienzo [1567] Reference de Matienzo1967). Collectives that bind through a variety of ties—via kinship, economic reciprocity, shared ancestors and commonly held land—ayllus were, and remain, important actors in the region's political, economic and social affairs (Doyle Reference Doyle1988; Zuidema Reference Zuidema1973). They serve as flexible mechanisms for collective action that can encompass a few nuclear households, unite extended lineages, or embrace entire regions. All ayllus provide certain rights and responsibilities to their members, giving people a sense of what to expect from group members and what others should expect from them.

Ayllus, today and in the past, are dynamic institutions that adjust to changing circumstances (e.g. Penry Reference Penry2019; Wernke Reference Wernke2013). Contemporary emphasis on tirakuna [earth beings] in mountains and other features, for example, may be a reaction to the destruction of ancestral remains by the Spanish (de la Cadena Reference de la Cadena2015; Gose Reference Gose2018). The only constant has been an organizational model based on kin relations. The enduring importance of ayllus in the Inca Empire, Spanish colony and contemporary nation-state raises a political science conundrum. Factionalism generated by kin-based sodalities like the ayllu is traditionally understood as incommensurate with state government: shattering the power of sodalities has long been seen as a prerequisite to the centralized, coercive institutions often used to define the state. For scholars in this paradigm, the role of kinship and affinity in governance should fade over time (e.g. Childe Reference Childe1950; Flannery & Marcus Reference Flannery and Marcus2012; Trigger Reference Trigger2003).

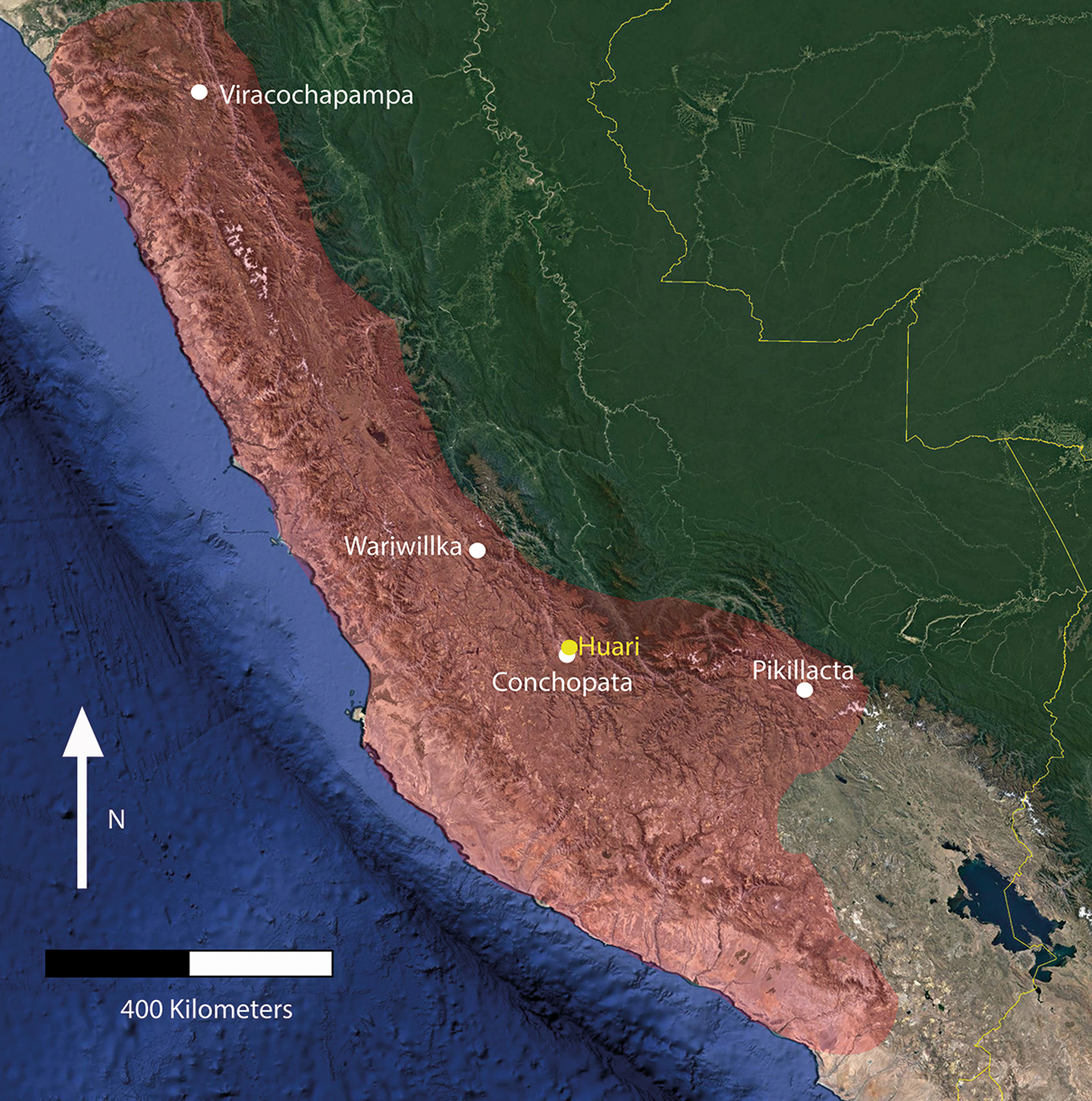

This article re-evaluates the role of kin-based sodalities in early state formation and expansion through a Middle Horizon (ce 600–1000) case study of the expansive Wari polity, centred on the sprawling conurbation of Huari in the Ayacucho Valley of Peru (Fig. 1). While some argue that ayllus were foundational to Wari, others posit that they developed later and even contributed to Wari's demise (e.g. Cook Reference Cook1992; Glowacki & Malpass Reference Glowacki and Malpass2003; Isbell Reference Isbell1997; Meddens Reference Meddens2020; Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Bettcher and Valdez2002). We suggest that these differing viewpoints can be reconciled if we approach urbanization and political centralization as dynamic, ongoing processes of assemblage creation rather than singular events (Crellin Reference Crellin2020). City and state are not fixed entities (Leadbetter Reference Leadbetter2021; M.L. Smith Reference Smith2021).

Figure 1. Map showing the approximate extent of Wari and Wari-influenced artifacts, as well as the location of some of the sites mentioned in the text.

As with early polities elsewhere, interpretations of Wari political organization tend to posit a single static model of governance, fully formed from its inception. Wari was a monarchy (Isbell Reference Isbell2004), a collective of powerful ayllus (Cook Reference Cook1992), or a system of client states (Meddens Reference Meddens2020). This article, in contrast, emphasizes the contingencies of unfolding political processes. We argue that the gradual development of ayllus in the Wari heartland correlates with incipient urbanization in the sixth century ce. These work-in-progress social mechanisms helped people navigate the new collective action problems of city life, a still inchoate countryside and a far-flung web of long-distance entanglements. Ayllu formation led to the development of a heterarchical political organization rife with internal competition that initially constrained greater political centralization. As circumstances changed, so did the ayllu, eventually allowing for the paradoxical growth of a ruling class.

All political projects are rife with tension. Solutions to today's problems inevitably bear unexpected consequences for future generations. In the case of Wari, development of ayllus in the sixth century ce shaped how families interacted with each other over the next four centuries. Ongoing construction and maintenance of these kin-based sodalities was both foundational to what many consider to be the first state in the Andes and a significant factor in its eventual ruin. In this paper, we demonstrate how sodality construction facilitated ongoing, often freighted, negotiations about identity, labour and sovereignty that force us to re-evaluate long-held conceptualizations of the city, state and civilization.

Kin, clan, class and the making of states

Kinship organizations have traditionally been seen as anathema to the state. Henry Maine (Reference Maine1861), Johannes Bachofen (Reference Bachofen1861), Lewis Henry Morgan ([1877] Reference Morgan1963) and other nineteenth-century scholars drew a distinction between kin- and class-based societies. Although their various evolutionary models differed in detail, authors of this era suggested that blood ties organized the earliest groups. Maine posited that patriarchs oversaw the original form of society, Bachofen thought it was a matriarchy, and Morgan said that few rules applied in an era of ‘primitive promiscuity’. From these (and other) proposed initial conditions, scholars mapped a progression, incorporating larger and larger kin-based (or kin-inspired) groupings until they were replaced by class-based distinctions.

These early scholars agreed that blood and ancestral ties were a deterrent of the state—in Morgan's words ([1877] Reference Morgan1963, 6), certain kinship organizations were ‘obstacles which delayed civilization’—and this sentiment would continue into the twentieth century. Weber ([1915] Reference Weber1951, 237), for example, argued that the power of influential extended families had to be shattered for a state to form and, for Childe (Reference Childe1950), a ‘Neolithic revolution’ was needed. More recent work continues to draw a distinction between kin- and class-based societies and argues that the ‘cage of norms’ in the former inhibited growth of the latter (Acemoglu & Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2019, 18; also see Fukuyama Reference Fukuyama2011, 51; Migdal Reference Migdal1988, 14; Trigger Reference Trigger2003, 46), while attributing failures of state-building in places like Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya to difficulties in overcoming ‘tribal’ divides.

We suggest that these approaches suffer by trying to draw clear lines between kin, clans, class and other groupings. All are social constructions, albeit with different rationales provided for group membership and varying expectations for behaviours. Sahlins (Reference Sahlins2013, ix) defines kinship as ‘mutuality of being’ with kinfolk being those ‘who participate intrinsically in each other's existence’. The same broad definition can be applied to other social groupings, with each person in society negotiating various identities to determine how others should be treated and how they should be treated in different situations. We expect ‘family’ or ‘fellow Americans’ to act in a certain way, and so considerable efforts are made both to patrol group memberships and—‘Workers of the World, Unite!’—cultivate within-group solidarity. Seen in this way, differences between kin, clans, class and other groupings are primarily of scale, cohesion, internal organization and invented rationales authorizing membership (Southall Reference Southall and Gutkind1970; Reference Southall, Levinson and Ember1996).

Such groups function as units of collective action whose members can be put to work to achieve a shared goal within a given social sphere (Hardin Reference Hardin2013). Governance—legitimate acts by which individuals are directed, controlled and held accountable (Bevir Reference Bevir2013)—is dynamic and varies between groups. Different social groups come together into an unruly societal assemblage of often competing interests that remains fluid in its organization (DeLanda Reference DeLanda2006; Reference DeLanda2016). Acts of extending sovereignty—claiming the right to make and enforce decisions on others’ behalf (Philpott Reference Philpott1995)—may create a sustained shape to this assemblage by either increasing membership of a pre-existing faction or inventing new identities that incorporate various groups into a broader collective. Violence, gift giving, charisma, propaganda and taxation all serve as tools to extend sovereignty and manufacture consent (Graeber & Wengrow Reference Graeber and Wengrow2021, 431). The archaeological ‘state’ thus emerges as a concept that allows us to think through the ‘entire complex of practical and theoretical activities with which the ruling class not only justifies and maintains its dominance but manages to win the active consent of those over whom it rules’ (Gramsci Reference Gramsci, Hoare and Nowell Smith1971, 244).

However, sovereignty and consent always remain circumscribed, multi-stranded and never fully achieved. Thinking in terms of identity construction, institutional organization and sovereignty extension dissolves many hard-and-fast stages of societal development made by nineteenth-century cultural evolutionists. Although there is a general trend over the past 20,000 years towards larger population aggregates organized within more complex societies (Blanton 2016; Feinman Reference Feinman and Carballo2013), the lines drawn to define ‘cities’ and ‘states’ by archaeologists are arbitrary ones that can obscure humanity's ongoing socio-political response to shifting circumstances. As more people spent more time in one place, a range of challenges ensued from food allocation to waste management, conflict resolution and wealth accumulation. One way of dealing with these challenges is to reassess the meaning of kinship.

A larger unit of collective action can help to coordinate activity within urbanized settings. To hold together, these larger units require integrative mechanisms and the extension of sovereignty to previously unaffiliated groups (Carballo Reference Carballo2013; DeMarrais & Earle Reference DeMarrais and Earle2017). We call this process sodality construction. The rules of group membership change as sodalities coalesce, such that one's ‘kin’ can shift to encompass those sharing a more vaguely defined descent from a biological or fictive common ancestor. Previously held groupings, such as nuclear families, often continue to matter, but one's rights and responsibilities to other members of a community are in flux as new kin-based sodalities join others based on occupation, gender, religion and other criteria (Carsten Reference Carsten2004; Terpstra Reference Terpstra2000).

Early urbanized settings can therefore be seen as ‘tribal’ in Radcliffe-Brown's ([1922] Reference Radcliffe-Brown1948, 23) sense of the term as ‘loose aggregates of independent local groups’. Maximal group memberships often remain fluid, with little coercive pressure applied towards cohesion except under specific circumstances of warfare or ceremonialism (Graeber & Sahlins Reference Graeber and Sahlins2017; Graeber & Wengrow Reference Graeber and Wengrow2021). A coalition may nonetheless find ways to stabilize relationships across various sodalities to form a more overarching assemblage, thus extending the reach of sovereign power across an emerging city and countryside. Methods of doing so are varied and dynamic, leading to the wide number of hierarchical, heterarchical and egalitarian political organizations documented across early complex societies (Blanton & Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2007; M.E. Smith Reference Smith2011). ‘City’ and ‘state’ are just two of many labels that we attach to some of the footprints of these broader collectives. They provide a name for some of the moments of greater coherence wherein sovereignty was extended and sustained through a ‘political machine’ that temporarily bound diverse peoples and other things into an unruly assemblage (A.T. Smith Reference Smith2015).

Urbanization and regional polity formation often proceed rapidly on an archaeological timescale. Within a couple of generations, nominal group membership could expand from 50 to 500,000 people (Birch Reference Birch2013). ‘City’ and ‘state’, however, did not crystallize into static forms during this time. Instead, emerging leaders were engaged in ongoing efforts to coordinate activities across a dynamic assemblage composed of often antagonistic components. The most familiar social identities were often those that had developed at smaller scales. Expanding and adapting pre-existing sodalities was an intelligible and pragmatic solution to many challenges associated with urbanization and regional polity formation. Their constructions were bottom-up responses to a shifting social landscape lacking both a strongly held civic (and polity-wide) identity and overarching political sovereignty.

City, polity and sodality thus developed together in a frenetic few decades of becoming urban and would continue to do so as population aggregation slowed and eventually reversed. Those who sought to extend sovereignty across a nascent polity of shifting people, animals and things therefore navigated a fraught political landscape of entrenched intermediate groupings to achieve their goals (e.g. Angelback & Grier Reference Angelbeck and Grier2012). Integrative ceremonies, public works, redistribution of wealth and monumental building projects were among the mechanisms used to enlist a broader coalition and extend authority (e.g. Kowalewski Reference Kowalewski and Birch2013). Shared interests abroad could also align interests at home, encouraging development of institutions capable of more firmly bridging sodality divides.

The centralized and specialized coercive institutions often used to define the state by archaeologists, when they occur at all, thus emerge from an ongoing interplay with the sodalities structuring the first decades in cities and regionally organized polities (see Wang Reference Wang2022 for the enduring influence of kinship). The Inca Empire, for example, was organized around a group of royal ayllus, each with claims to territory and the spoils of conquest (Conrad Reference Conrad, Demarest and Conrad1992; Zuidema Reference Zuidema1964; Reference Zuidema and Decoster1990). Home and family were also used as metaphors to help organize entire neighbourhoods and cities in early Mesopotamia (Ur Reference Ur2014), and ‘kinship-based groups were the basis of both Shang identity and socio-political action’ in early China (Campbell Reference Campbell2018, xxv). The ancient city of Tiwanaku in Bolivia was built by competing kin-related and geographically defined groups (Janusek Reference Janusek2002), and similar mechanisms were integral to the development of Rome and Teotihuacan (Fulminante Reference Fulminante2014; Manzanilla Reference Manzanilla2013).

Rather than being anathema to urbanization and polity organization, clans and other kinds of intermediate sodalities were often fundamental to the formation and ongoing coherence of those institutions that structured collective action in early cities and more complex societies (Fleming Reference Fleming2004; Jennings Reference Jennings2016; McIntosh Reference McIntosh2005; Porter Reference Porter, MacGuire and Bolger2013; Yoffee Reference Yoffee2005). Similar processes unfold into the present, with Cohen (Reference Cohen1981) emphasizing the construction of kinship networks—both fictive and biological—as integral to coordination and control of governance in Sierra Leone, and Varoufakis (Reference Varoufakis2017) characterizing the internal operations of the European Union as a network of kin-like backroom alliances relying on exclusivity and opacity.

Morgan, Weber, Childe and the contemporary scholars who follow them are right to underline potential tensions between existing sodalities and political institutions claiming a broader mandate. Although emerging sodalities often provided building blocks to make life within growing cities and regionally organized polities possible, the resulting factionalism also may serve as a curb to greater political centralization (Clastres Reference Clastres and Hurley1990). Indeed, efforts to build the institutions that we associate with the state have in many cases resulted from attempts to break the entrenched power of elite factions, in societies from medieval Angkor (Coedès Reference Coedès1968; Pollock Reference Pollock and Houben1996) to the Depression-era United States (e.g. Baum & Kernell Reference Baum and Kernell2001; Burk Reference Burk1990). The more centralized and specialized coercive institutions that scholars often associate with the state act less to initially extend sovereignty than to enforce and maintain it (Bondarenko Reference Bondarenko2014). Since these institutions often significantly infringe upon the power and autonomy of existing sodalities, they tend to develop only after other integrative mechanisms emerge (Jennings Reference Jennings2016; Jennings et al. Reference Jennings, Frenette, Harmacy, Keenan and Maciw2021). The ‘state’ arrives after the ‘city’ has formed.

Institutions associated with states do not emerge by shattering a ‘cage of norms’ (contra Acemoglu & Robinson Reference Acemoglu and Robinson2019, 18). They are built by the inmates re-fashioning its bars, retooling their assemblage over time to coordinate, circumvent, or capture more distributed political institutions. These earlier institutions coalesced around sodalities in the initial pulse of urbanization by melding local traditions with foreign ideas and novel inventions (Jennings Reference Jennings2016; Reference Jennings2021; Jennings et al. Reference Jennings, Frenette, Harmacy, Keenan and Maciw2021). Later leaders, from either established or emergent sodalities, may recognize in this flux the opportunity to begin a new political project, altering urban forms to enact emerging notions of identity and proper order. Rewiring a society's power relationships is nonetheless provocative, risking the decline or even destruction of cities and regionally organized polities centuries after their formation (Bondarenko Reference Bondarenko2014; Jennings & Earle Reference Jennings and Earle2016). Aspirational political projects often devolve into factionalism (Anderson Reference Anderson1994; Leach Reference Leach1954; Haider Reference Haider2020). Shattering the ‘cage of norms’ thus leaves societies in pieces, leaving people adhering to only their most deeply felt identities.

We argue that similar processes played out at Wari, a regionally organized polity that rapidly coalesced during the sixth century ce in the central highlands of Peru. We suggest that lineage-based identities were still weakly developed at the beginning of the Middle Horizon in the Wari heartland, and communities thus reformulated the exogenous concept of an ayllu to provide the social scaffolding required to organize activities in the city of Huari, its surrounding communities and more far-flung colonies. Among the results of ayllu construction was the creation of a set of Wari ancestors: honoured individuals associated with particular groups. These ancestors, who were individuals separated and elevated from the common dead (e.g. Whitley Reference Whitley2002), are emblematic of an emergent, dynamic heterarchical political structure inhibiting development of coercive state institutions during the early Middle Horizon. Although the ayllu would endure in other forms, the downplaying of these ancestors in art and other changes in the late Middle Horizon suggest an attempt by one faction to consolidate power and extend authority that may ultimately have led to the polity's demise.

Importing the ayllu

At its height in the eighth century ad, Huari was the largest city in the Pre-Columbian Andes. The site sprawled across 10 square kilometres and housed as many as 40,000 residents (Isbell Reference Isbell, Manzanilla and Chapdelaine2009, 215). Huari had grown rapidly near the end of the Early Intermediate Period (200 bce–ce 600) by attracting migrants from the surrounding region (Schreiber Reference Schreiber1992, 87–91; Valdez & Valdez Reference Valdez and Valdez2017, 10). Economic specialization surged and status differences widened (González Carré & Gálvez Pérez Reference González Carré and Gálvez Pérez1981; Isbell & Vranich Reference Isbell, Vranich and Silverman2004; Spickard Reference Spickard and Sandweiss1983; von Hagen & Morris Reference von Hagen and Morris1998). Since there was no previous urban tradition in the region, families at Huari could not lean on prior knowledge to navigate the challenges associated with incipient urbanization (M.E. Smith Reference Smith and Gyucha2019).

In the centuries prior to Huari's urbanization, people in Ayacucho primarily lived in small, dispersed villages (Leoni Reference Leoni2005; Reference Leoni2013; Lumbreras Reference Lumbreras1959; Reference Lumbreras1974; MacNeish Reference MacNeish, MacNeish, Cook, Lumbreras, Vierra and Nelken-Terner1981; Ochatoma & Cabrera Reference Ochatoma and Cabrera2010; Pérez Calderón & Carrera Aquino Reference Pérez Calderón and Carrera Aquino2015) (Fig. 2). Artifact assemblages and settlement locations suggest an agropastoral lifestyle and, at most, only muted status differences across families. Nuclear families lived largely in discrete households represented by a single structure often associated with an external patio. Tombs tended to be single inhumations located in or around the home. When large groups of people gathered, they did so in the region's scattered ceremonial centres (Cavero Palomino & Huamaní Díaz Reference Cavero Palomina and Huamaní Díaz2015; Leoni Reference Leoni2005; Reference Leoni, Isbell and Silverman2006; Peréz Calderón & Paredes Reference Pérez Calderón and Paredes2015; Vivanco & Mendoza Reference Vivanco and Mendoza2015). Differences in ceremonial architecture across space and time in Ayacucho are striking, suggesting that sites competed for followers with a range of ideologies and practices. The best understood of these ceremonial centres was Ñawinpukyo, a mountain cult with an emphasis on communal feasting that served as a ‘community integrative mechanism’ (Leoni Reference Leoni, Isbell and Silverman2006, 300).

Figure 2. House structures excavated from the Huarpa village of Huaqanmarka. (Courtesy of Lidio and J. Ernesto Valdez.)

For most of the Early Intermediate Period, we see little evidence in Ayacucho for a well-developed means to organize people into intermediate groups resting between the nuclear family and a community-at-large defined by the catchments of various ceremonial centres. Archaeologists have documented only a few large domestic compounds and no clearly defined neighbourhoods (Pérez Calderón Reference Pérez Calderón2019a, 193–4). There are also no ancestral shrines, minimal anthropomorphic depictions in art and few collective tombs (Knobloch Reference Knobloch1976; Pérez Calderón Reference Pérez Calderón2019b). Although determining ayllu relationships—and those of other kinds of sodalities—can be difficult without archaeological evidence (Berquist Reference Berquist2021; Ibarra Asencios Reference Ibarra Asencios2021; Lau Reference Lau2002; Mantha Reference Mantha2009), mid-range social groupings were not as necessary for village life when only a few dozen people spent significant time together. This pattern began to change in the fifth century ce as more people moved into Huari, Ñawinpukyo and other ceremonial centres (Fig. 3). We see the first evidence for communal burials, multi-family households, intensive agriculture, marked status differences and inter-community violence (Alvarez Reference Alvarez2014; Anders Reference Anders1986; Leoni Reference Leoni, Isbell and Silverman2006; Lumbreras Reference Lumbreras1974; MacNeish et al. Reference MacNeish, Cook, Lumbreras, Vierra and Nelken-Terner1981; Pérez Calderón Reference Pérez Calderón, Pérez, Aguilar and Purizaga2001; Reference Pérez Calderón2019a; Valdez Reference Valdez2017). Sodalities were beginning to form by extending kinship relations to encompass larger groups of people.

Figure 3. Site plan of Ñawinpukyo, with most buildings probably dating towards the end of the Early Intermediate Period. (Courtesy of Juan Leoni.)

In the sixth century ce, leaders from rival ceremonial centres competed for residents and followers. Huari, and to a lesser extent Conchopata, ultimately triumphed. Villages had emptied by the end of the century, with families packing into these two centres (Isbell Reference Isbell1977; Isbell & Schreiber Reference Isbell and Schreiber1978; Pérez Calderón Reference Pérez Calderón, Pérez, Aguilar and Purizaga2001; Valdez & Valdez Reference Valdez and Valdez2021). Many more people were now living together, facing novel social concerns in growing cities and navigating a developing countryside (Jennings Reference Jennings2016; Yoffee Reference Yoffee2005). Spanning the end of the Early Intermediate Period and beginning of the Middle Horizon, the first decades of urban life at Huari and Conchopata (as well as aborted efforts at sites like Nawinpukyo) were a period of further experimentation in new ideologies, living arrangements, ceremonial structures and funerary practices (e.g, Cook Reference Cook and Bergh2012; Ochatoma Paravicino et al. Reference Ochatoma Paravicino, Cabrera Romero and Mancilla Rojas2015; Pérez Calderón Reference Pérez Calderón2019b; Valdez et al. Reference Valdez, Bettcher and Valdez2002). This experimentation, at least in part, reflects attempts to address urbanization's collective action problems (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Ceramic models of kancha architecture probably dating to the sixth or seventh century ce. (Courtesy of William Isbell.)

As is often the case (Carballo Reference Carballo2013), high-status families appear to have taken a decisive role in these efforts both to consolidate their own power and limit the power of rivals (Isbell Reference Isbell, Christie and Sarro2006). Amid this experimentation, emergent sodalities attempted to reinforce their political positions at home by extending their sovereignty beyond Ayacucho through a mix of warfare, colonization, negotiations and exchange (Isbell Reference Isbell, Manzanilla and Chapdelaine2009; Schreiber Reference Schreiber1992). When people returned to the valley from their travels, they brought back new ideas that could be married to local traditions. Iconography from the Lake Titicaca region, for example, would be used to support a developing Wari ideology of violence, fertility and elite status (Cook Reference Cook1994), and Ayacucho's D-shaped temple tradition was adapted to host new ceremonies incorporating the dead (Cook Reference Cook and Bray2015). By the end of the seventh century ce, a constellation of ideas had gained favour throughout the heartland that would shape how people interacted with each other in Ayacucho and abroad (Isbell Reference Isbell, Silverman and Isbell2008; Reference Isbell and Jennings2010). One of these ideas was the ayllu.

Kin-based sodalities had previously developed elsewhere in the Andes in response to population aggregation, expanding exchange networks, schismogenesis and other factors. As Berquist argues elsewhere (Reference Berquist2021), an iteration of the ayllu was well developed in the northern highlands at the time of Huari's urbanization. Many larger sites in that region were organized around multiple kanchas, composed of long halls flanking a central patio (e.g. Herrera Reference Herrera2005; Narvaez & Melly Cava Reference Narváez, Melly Cava and Narváez2010; Segura Rivera Reference Segura Rivera and Ibarra Asencios2016) (Fig. 5). The kanchas were spaces for feasting and ancestor veneration among families who resided together during the time ceremonies were being conducted (Berquist Reference Berquist2021; Lau Reference Lau2010; Topic & Topic Reference Topic and Topic2001; Reference Topic, Topic and Jennings2010). Some of the dead were buried within the walls of kanchas and large niches in the halls may have been used to showcase mummified remains or deposit offerings to the dead (Herrera Reference Herrera2005; Lau Reference Lau2010; Topic Reference Topic1998; Reference Topic, Marcus and Williams2009; Topic & Topic Reference Topic and Topic2001; Reference Topic, Topic and Jennings2010). Other ancestors were often buried in accessible collective tombs nearby (Ibarra Asencios Reference Ibarra Asencios2021; Orsini Reference Orsini2014; Ponte Reference Ponte2015). The region's art depicts honoured ancestors, as well as feasts and other rituals taking place at collective tombs and kanchas (Lau Reference Lau2002; Reference Lau2011; Reference Lau2016) (Fig. 6).

Figure 5. Compounds c40 and c41 at the Recuay site of Yayno in the highlands of Ancash. Note the marked resemblance of the structures to later Huari patio groups. (Courtesy of George F. Lau.)

Figure 6. Communal tombs at Marcahuamachuco in the northern highlands.

As discussed above, multiple family patio groups and open-sepulchre mortuary monuments can be found in Ayacucho from at least the fifth century ce. However, their sporadic distribution suggests that people in the region were only beginning to form larger kin-based sodalities. As Wari interactions with the northern highlands increased during the seventh century ce, aspects of the northern highland idea of the ayllu with its kanchas, funerary practices and associated art gained traction, dovetailing with Ayacucho's own social experiments in sodality construction. Kin relationships changed, and a unique kind of Wari ayllu began to develop within the rapidly growing, cosmopolitan city. Visions of a larger ayllu-based collective may have inspired builders of Viracochapampa, a 30-hectare site in the northern highlands with repetitive cellular architecture that mimicked that region's kanchas (Topic Reference Topic, Isbell and McEwan1991; Topic & Topic Reference Topic and Topic2001; Reference Topic, Topic and Jennings2010) (Fig. 7). Pikillacta in the southern highlands was another seventh-century Wari site with similar inspirations. At Pikillacta, the vision of an expansive ayllu that incorporated outsiders was put into practice, with multiple residential compounds enlisting local groups via feasts, ancestor worship and other mechanisms (McEwan Reference McEwan1998; Reference McEwan2005). These sites, located near two extremes of Wari influence, may have been aspirational blueprints for assembling a new political machine, the spatial manifestation of an idealized social order (Berquist Reference Berquist2021). The reality of creating ayllus from previously independent families and coordinating action between them was far messier, particularly in the sprawling city of Huari.

Figure 7. Composite orthophoto of Virachochapampa, in Huamachuco.

Ayllus and Wari state-making

While builders may have imagined an idealized organization of society in the architecture of Viracochapampa and Pikillacta, Huari and Conchopata were places of ‘spatial confusion’ marked by ‘enclosure and redundancy’ (Isbell & Vranich Reference Isbell, Vranich and Silverman2004, 176). Rapid urbanization of the latter two settlements had created a dense warren of architectural spaces (Isbell Reference Isbell and Millones2001a; Reference Isbell, Manzanilla and Chapdelaine2009; Ochatoma Paravicino Reference Ochatoma Paravicino2007; Ochatoma Paravicino et al. Reference Ochatoma Paravicino, Cabrera Romero and Mancilla Rojas2015; Pérez Calderón Reference Pérez Calderón1999), a jumble of ‘repetitive, apartment-like cells’ and small open spaces (Isbell Reference Isbell, Manzanilla and Chapdelaine2009, 209). There was no royal palace, main temple complex, great plaza, or other core feature to unite residents—no one seemed in charge of the cities writ large and there were few places for large groups to gather. Excavations at Conchopata nonetheless reveal an early Middle Horizon city being organized at a more intermediate level around expansive residential compounds with internal patios and narrow galleries that resembled kancha architecture from the north (Isbell Reference Isbell2001b; Ochatoma Paravicino Reference Ochatoma Paravicino2007) (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Early Middle Horizon architecture at Conchopata. (Courtesy of William Isbell.)

Bioarchaeological research suggests that these compounds housed extended families anchored by a cohort of closely related females (Tung Reference Tung2012, 203). Blacker and Cook (Reference Blacker and Cook2006) call the multi-room compounds ‘lineage houses’ and Isbell (Reference Isbell, Christie and Sarro2006) refers to them as palaces. Whatever term used, these compounds were carving out their place within a dense urban landscape—sometimes levelling structures that had been there before—with more vernacular dwellings crowded around them in remaining spaces. Lineage houses hosted feasts and other rituals celebrating shared ancestors (Nash Reference Nash and Klarich2010; Reference Nash and Bergh2012). Residents of the vernacular structures contributed resources and labour to events held within the lineage houses, where interior patios ensured sustained face-to-face interactions (Jennings et al. Reference Jennings, Alaica and Biwerin press; Nash Reference Nash and Klarich2010; Rosenfeld Reference Rosenfeld2012; Sayre & Whitehead Reference Sayre, Whitehead, Sayre and Bruno2017). People dined with, and sometimes intentionally smashed, symbolically laden jars, cups and bowls, and drank hallucinogen-laced beer for a shared psychotropic experience (Biwer et al. Reference Biwer, Yépez Álvarez, Bautista and Jennings2022; Cook & Glowacki Reference Cook, Glowacki and Bray2003; Nishizawa Reference Nishizawa2011).

Another space of collective action were D-shaped temples (Fig. 9). By now ubiquitous at Huari and Conchopata, these buildings had curved walls with niches, a single entrance in their straight wall and, typically, a small courtyard around the entrance (Bragayrac Reference Bragayrac, Isbell and McEwan1991; Cook Reference Cook, Benson and Cook2001). The link between the lineage houses and D-shaped enclosures remains unclear, but the latter spaces also served as locations for feasts and other group rituals (Sayre & Whitehead Reference Sayre, Whitehead, Sayre and Bruno2017; Tung & Knudson Reference Tung and Knudson2010). D-shaped temples and their courtyards could generally fit more people than an individual lineage house's internal patio, but associated events could still gather just a small subset of a city's population. If the niches were used to display mummy bundles, then only select dead were honoured at the events (Cook Reference Cook, Benson and Cook2001; McEwan Reference McEwan1998).

Figure 9. A D-shaped structure at Huari. (Courtesy of the ROM-Vanderbilt Huari Mapping Project.)

The shared social space of lineage-house patios and D-shaped structures allowed intersecting group identities to cohere. Sodalities were forming through collective tasks and face-to-face interaction. By preparing food, worshipping together, tending the dead and other activities, they were building trust and reiterating the rights and responsibilities of sodality membership. The activities that took place within lineage-house patios and D-shaped structures hint at different sodality types (and scales), reflecting the multiplication of identities in early urban settings (M.L. Smith Reference Smith2010). The emphasis on these spaces during the early Middle Horizon also suggests that most sodality construction was happening at this intermediate level. Although attempts were probably being made to forge more encompassing identities, focus remained on assembling the ayllu to coordinate collective action.

A diachronic perspective further highlights the ongoing process of ayllu construction. As Tschauner and Isbell note for Conchopata (Reference Tschauner and Isbell2012, 137, translation JJ):

both the rectangular complexes [the lineage houses] and the disorderly agglutinated constructions were dynamic, integrating new rooms, entrances, patios, and plazas as the spaces were renewed by demolition and reconstruction, which involved processes of careful burial of architectural structures—activities that were at once ritual and functional.

A room might be remodelled with a new floor, then filled with selected ceramics, dug out and reused for another activity—all within a few generations (Groleau Reference Groleau2009; Reference Groleau2011; Isbell & Groleau Reference Isbell, Groleau and Klarich2010). The glut of room and patio renovations, terminations and fillings suggests a population on the move across the site, with ayllu affiliations constantly in flux and leaders striving to create a cohesive assemblage from families who had been far more autonomous a few generations earlier.

We argue that Wari cities were sputtering engines of ayllu construction. Kancha enclosures helped forge new kin ties, producing self-aware political actors. D-shaped temples did similar work at a slightly larger scale, creating more overarching sodalities that, at least temporarily, bridged higher-status lineages with allies and followers. In turn, high-status lineages actively promoted ancestor cults through the construction of mausolea and public performance of ceremonies, rendering these sodalities legible as descent groups and naturalizing bonds of shared interests (Fig. 10). Larger plazas and platforms may have constituted attempts to create a broader civic identity or unite rival families into an urban elite (Bragayrac Reference Bragayrac, Isbell and McEwan1991; Peréz Calderón Reference Pérez Calderón1999). However, none of these monuments occupies a central location or dominates the urban landscape through size alone, as did the massive mud-brick pyramids of Peru's north coast. The seeming lack of coordination of activities across Huari and Conchopata during the early Middle Horizon suggests settlements experienced in a decentralized manner. The process was ongoing, unruly and occasionally antagonistic, just as urbanization unfolds in many past and present fast-growing cities (Jennings Reference Jennings2016).

Figure 10. Two of the collective Middle Horizon tomb types found in the Wari heartland. (Courtesy of William Isbell.)

Wari ayllus were distinct from those that had developed under northern highlands conditions, as well as those that had emerged around the same time in the Tiwanaku sphere. The emphasis on status and face-to-face interaction in Wari cities spurred the development of a political structure composed of rival factions that were internally hierarchical while remaining fluid in their relationships with each other (e.g. Crumley Reference Crumley1995; see Makowski Reference Makowski2016 for a related view). This heterarchical organization is mirrored in iconographic depictions of individuals who are identifiable by dress, facial markings and other features (Knobloch Reference Knobloch and Makokwski2010; Reference Knobloch and Bergh2012; Reference Knobloch2016; Nash Reference Nash, Isbell, Uribe, Tiballi and Zegarra2018; Vasquez de Arthur Reference Vasquez de Arthur2020). Who these agents represent remains unclear, but many appear to depict distinct individuals—whether a leader, ancestor, or a composite figure standing for a group—associated with Huari and its environs (Fig. 11). The same agents are depicted on art found throughout the central Andes and on a wide variety of media. By tracking actions across depictions, one can begin to reconstruct biographies of certain agents whose histories sometimes read as sagas of friendship, conflict and betrayal (Knobloch Reference Knobloch2016).

Figure 11. Agents depicted on Wari-era art. (Courtesy of Patricia Knobloch.)

Wari politics may have been put on display in two sets of stone figurines interred at Pikillacta in the late seventh century (Cook Reference Cook1992). Although some likely represent foreigners, Cook argues that many figurines were meant to depict known Wari actors whose relative status was displayed by their size and costume. Cook suggests that 20 figurines with matches in each set represent ‘Huari ayllus or the mythical ancestors of the 20 highest-ranked descent groups’. The bronze bars found in their midst served as ‘a metonym’ for their collective authority in Wari society (Cook Reference Cook1992, 358–9). Although Cook's argument is intriguing, different groupings of individuals occur in other figurine sets—Knobloch (Reference Knobloch2015) has documented 120 different agents in miniatures. The wide array of depicted agents may be, in part, a product of Wari coalition building. Stories would alter as ayllu rankings changed; artists could pursue their own agenda. Each group likely saw the political landscape around them differently and would promote their vision in those areas where they held more power.

A social network analysis of agents depicted on Wari art provides further confirmation of early Wari's heterachical political structure (Gibbon et al. Reference Gibbon, Knobloch and Jennings2022). Rather than an apical agent through which all others connected, the Wari social network was composed of coalitions whose members were associated with different parts of the central Andes. Perhaps it was the external-facing actions of these coalitions—warfare, diplomacy, trading missions—that temporarily formed larger collective action groups above lineage house-based ayllus. Working together on a shared mission of a limited duration, they imagined at places like Pikillacta what their society could be. Centralized, more coercive mechanisms may have developed to organize those involved in some of Wari's distant interactions with foreigners (e.g. Honeychurch Reference Honeychurch and Honeychurch2015). If true, the seeds of the state were sown by tinkering with novel political forms that, at least initially, remained unacceptable at home.

The mid ninth century ce saw a ‘marked increase in the representation of zoomorphic supernatural beings’ in Wari art (Knobloch Reference Knobloch and Bergh2012, 131). The downplaying of human agents came amid what Dorothy Menzel (Reference Menzel1964, 70) called ‘a severe crisis’ in governance. An urban renewal process razed much of Huari's architecture, agricultural production was centralized and colonies were abandoned, founded, or re-organized (Isbell Reference Isbell and Millones2001a; Reference Isbell, Manzanilla and Chapdelaine2009; Lumbreras Reference Lumbreras1974; Pérez Calderón Reference Pérez Calderón, Pérez, Aguilar and Purizaga2001; Schreiber Reference Schreiber, Alcock, D'Altroy, Morrison and Sinopoli2001). These efforts may relate to a bid to end heterarchy by replacing a political organization based on a shifting coalition of rival groups with a more centralized, coercive and hierarchical government (see Jennings Reference Jennings2016 for a similar trajectory in other early cities). If this was the case, then the late Middle Horizon attempt to create the institutions the archaeologists commonly associate with the state was ultimately unsuccessful. The ninth-century renovations of Huari were never completed and, if neighbouring Conchopata can serve as a guide, the city was in steep decline during the tenth century (Isbell Reference Isbell, Manzanilla and Chapdelaine2009, 114–15).

Re-thinking Wari politics

Although nineteenth-century evolutionary paradigms have been soundly criticized in archaeology (Feinman & Neitzel Reference Feinman and Neitzel1984; McGuire & Saitta Reference McGuire and Saitta1996; Yoffee Reference Yoffee, Yoffee and Sherratt1993), there remains a pernicious tendency to think in stages of cultural development (Jennings Reference Jennings2016; Jennings et al. Reference Jennings, Frenette, Harmacy, Keenan and Maciw2021). Shifts from one kind of organization to another are still often glossed as a ‘sharp transition’ (Yoffee Reference Yoffee2005, 230) or fit of ‘paroxysmal change’ (Possehl Reference Possehl1990, 275), echoing the tempo of earlier evolutionary schema. This is particularly the case for analysis of what used to be called the ‘civilization’ stage of development, where more fine-grained chronological data now show that urbanization and regionally organized political formation could develop within the space of a few generations (Cowgill Reference Cowgill2015; Kenoyer Reference Kenoyer, Marcus and Sabloff2008; Sauer Reference Sauer2021). Taken to its logical extreme, this viewpoint suggests a build-up of societal pressures before—Bang!—city, state and civilization unfurl together in an archaeological instant. The Olmec, Shang, or Wari appear suddenly on the scene with an enduring, fully formed political structure defining the period.

Few archaeologists today consciously subscribe to this model of culture change. Recent scholarship emphasizes ongoing political experimentation to solve the many challenges generated by incipient urbanization and regional polity formation (Birch Reference Birch2013; Gyucha Reference Gyucha2019). The important role of lineages, clans and other kinds of sodalities in these societies are also routinely highlighted (Campbell Reference Campbell2018; Carballo Reference Carballo2013; Fox et al. Reference Fox, Cook, Chase and Chase1996). There is nonetheless a greater focus on variation between early cities and states than on change occurring over time within these entities (Feinman & Marcus Reference Feinman and Marcus1998; Yoffee Reference Yoffee2015). Political, economic and social tools to manage life under these new conditions were works-in-progress for centuries, and we have failed to explore adequately the implications of this ongoing societal construction on long-accepted ideas about the relationship between city, state and civilization. A passing familiarity with early Athenian or Roman history reveals that ongoing factional battles, regime changes and political reorganizations produced the Classical forms by which we typically characterize these cities. We must assume that a similar dynamism unfolded at Huari.

In the sixth century, Huari grew by ‘virtually inhaling’ surrounding populations in the Ayacucho region (Schreiber Reference Schreiber2005, 265). Along with those living in Conchopata, Huari's citizens struggled with many novel coordination problems of urban life. Since they lacked well-developed sodalities that could serve as critical mechanisms of organizing collective action (i.e. Blanton/Fargher Reference Blanton and Fargher2016), those living in the Wari heartland adopted elements of an ayllu concept from the northern highlands, melded these elements with local traditions and then continued to adapt the concept to fit changing circumstances. Over time, Wari affairs, both in heartland cities and abroad, unfolded through ayllus constituted by co-residence, reciprocity, group ceremonies and shared ancestry. Resulting political arrangements were inherently messy. Coalitions were fragile and limited; they would fragment and re-form in new ways. The unruly assemblage was probably unmanageable at a macro-level, and as a few families grew in wealth and power it might have been tempting to encourage development of more centralized and specialized coercive institutions (Fig. 12). Efforts to consolidate power in the ninth century ce may have been temporarily successful but appear to have triggered the decline of the cities over the next century. Attempts to form broader, more coercive institutions led to Wari's ruin.

Figure 12. A ceramic effigy of a Wari-era elite being carried on a litter. The vessel was reportedly found in the central highland site of Wariwillka. (Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.)

We argue that our discussion of Wari's political development fits with available data. Although our colleagues working in the region may dispute some details, few would argue against the fundamental role played by ayllus—in the general sense of the term as kin-based sodalities—in organizing life at Wari sites or that a ninth-century disruption produced significant changes across the polity. Our interpretation can nonetheless be read as counter-intuitive because long-held assumptions create a tendency to feel that the arrival of what we have long categorized as ‘cities’ and ‘states’ should be intertwined. The state, with its constellation of centralized and coercive institutions, needs to be there from the beginning, since cities have long served as an indication that the state-level stage of development has been reached. If we replace conceptualization of static stages of socio-political development with dynamic assemblages, then we can more clearly see how politics unfolded within eras.

There is an unresolved tension in the study of Wari and many other early regionally organized polities. On one hand, researchers recognize the great importance of sodalities in these polities and the cities often associated with them. On the other hand, we assume that there must be a state hidden behind, and working against, these sodalities, pulling the strings to keep city and polity together. This tension is resolved when we see sodality construction as a common reaction to challenges of rapid population aggregation. Creating these larger units of collective action was an extended political project that, in the short term, curbed centralization and in the long term allowed for state-associated institutions to emerge sometimes. Although we have difficulty tracking the change in the absence of historical records, the assemblage that constituted Wari was always in flux. The ‘Wari’ of 900 ce was not the ‘Wari’ of 700 ce. An obvious point, but one that is elided when we assume city, state and civilization emerge as one.