Introduction: bricolage with Maman’s kids

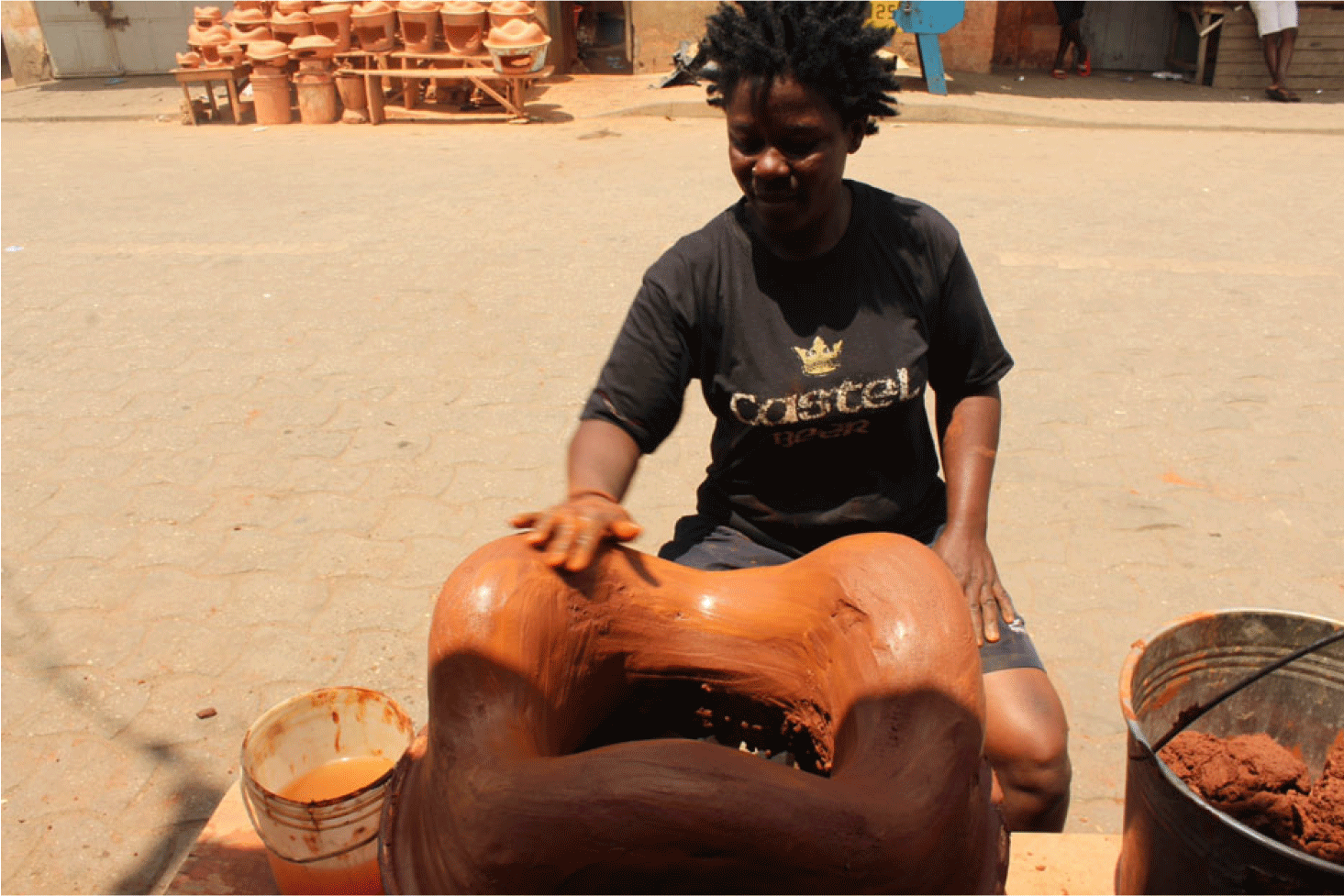

Maman has been making adokpo for more than ten years. A clay furnace used for cooking staple food such as rice and fufu, the adokpo has been part of the Togolese way of cooking since precolonial times. Maman sells her wares beside modern stoves and home appliances lining the streets of Lomé’s Tokoin quarter, and many still prefer to use adokpo due to the rising gas prices and coal being the cheaper option. As a clay maker herself (see Figure 1), she takes pride in belonging to the line of the first ‘makers’ in Togo, the blacksmiths and the potters, and is helped by her five children in the family business. Her eldest child steps on the clay before putting it in the lesso (iron mould), while her four younger boys stick around to play with the iron rods that they then bend into lesso. Maman lets her children play with the iron rods so they become familiar with the materials of the business they will eventually inherit. ‘This is how they learn,’ my friend Yao said as we watched Maman’s children ride the iron rod contraptions they were making (see Figure 2) – ‘Ils bricolent des choses’ (They tinker with things). This was also the first time I encountered bricolage as ‘trucs d’enfants’ (child’s play) in Lomé.

Figure 1. Maman making adokpo in the streets of Lomé.

Figure 2. Maman’s kids playing with the iron rods.

Stories of how Lomé’s ‘makers’Footnote 1 came to be interested in ‘making’ and the so-called Maker MovementFootnote 2 often start with them doing bricolage during their childhood. Based on Euro-American ideologies of the ‘hacker ethic’, do-it-yourself (DIY) and the commons (open source), the Maker Movement prides itself on democratizing technology by offering free tools and workshops for the community, and claims to be driven by a strong commitment to building on existing materials in order to ‘improve’ living conditions in the world (Davies Reference Davies2017; Dougherty Reference Dougherty2012).Footnote 3

In Lomé, traces of an emerging Maker Movement can be found within a few makerspaces and incubators. In these spaces, bricolage is considered by the young founders, instructors and participants as a longstanding practice that contributes to their work and to burgeoning city life. They recall stories of ‘tearing down’ computers and learning about specific parts, of putting together radio bits and pieces that don’t entirely go together, and of hacking VHS players and gaming consoles at the request of their friends. Arnaud, a coding workshop instructor in one of Lomé’s makerspaces, said that he first learned how computers work because he broke his sister’s computer while she was out with her friends. Thanks to this panic-stricken encounter and to opening and fixing the computer himself, Arnaud is now a computer engineering student at the University of Lomé and leads free coding workshops for disadvantaged kids in his spare time (see Figure 3). He looks back on this moment of assembling and disassembling the computer as crucial to his becoming a ‘maker’, and he encourages his students to do the same: to find broken things at home, and to try to take them apart and put them back together as part of the learning process.

Figure 3. Opening computers with Arnaud.

Yet whenever I hear makers from makerspaces introduce themselves, they often say: ‘We are makers but not bricoleurs.’ While Lomé’s makers remain passionate about bricolage as they look back fondly on their childhood experiences, there is a seeming disavowal of bricolage when introducing themselves and fashioning their ‘maker’ identity. What is it about bricolage as a concept and a practice that Lomé’s makers try to steer away from? How is bricolage in Lomé different from the way it is constructed in the Euro-American Maker Movement that openly celebrates this practice as fundamental to the movement? As the changing conceptualizations and understandings of bricolage and the Maker Movement reflect the global circulation of knowledge, ideologies and discourses (Tsing Reference Tsing2005; Swyngedouw Reference Swyngedouw2004; Appadurai Reference Appadurai1996), I unpack the tensions surrounding these ideologies-in-circulation when translated to particular urban settings such as Lomé, by foregrounding how young makers and tech innovators nuance and critique them through their own discourses and urban practices.

To do so, I adopt a multi-scalar approachFootnote 4 in unpacking the stories of Lomé’s makers: from their global presence to their lived experiences, from the global Maker Movements to their own backyards. Multi-scalar approaches allow us to see ‘the local as both saturated by and laboratory for the global’ (Piot Reference Piot2010: 18), more pertinently in exploring global neoliberal processes such as digital transformation and their influence on the everyday engagements of citizens. Given the various local and global scales they navigate, I position Lomé’s makers as agents of city making (Çaglar and Glick Schiller Reference Çaglar and Glick Schiller2018) situated within the global socio-historical conjunctures they bear witness to and try to shape, through the ways in which they make and remake present materials.

This article aims to broaden literatures on African contributions to global technological landscapes (Mavhunga Reference Mavhunga2014) by highlighting the critical perspectives and practices of everyday citizens in cities such as Lomé, which are often considered marginal and under-researched compared with tech KINGSFootnote 5 cities such as Nairobi, Abidjan and Lagos (see Newell Reference Newell2021; Kusimba Reference Kusimba2018; Osiakwan Reference Osiakwan, Ndemo and Weiss2017; Van den Broeck Reference Van den Broeck2017; Poggiali Reference Poggiali2016; Smith Reference Smith2007). More broadly, this article attempts to contribute to de-centring and decolonizingFootnote 6 ‘bricolage’ as a foundational concept of the Maker Movement and in academic discourse. Through Lomé’s makers’ practice and understanding of bricolage, I explore how ethnography affords epistemic resistance by putting the words and lived experiences of interlocutors at the centre of critique.

Vernacular practices of globally circulating ideologies on technology and innovation have a long history in the urban landscapes of African cities, for instance in ‘smart cities’ and the innovative urban practices of Kinois through ‘smartness from below’ (Pype Reference Pype and Mavhunga2017), alternatives to ‘authorized’ mobile phone repair in Kampala (Houston Reference Houston, Strebel, Bovet and Sormani2019), and local translations of the ‘right to repair’ for the informal solar grid repairers of Malawi (Samarakoon et al. Reference Samarakoon, Munro, Zalengera and Kearnes2022). While urban practices are often carried out to bridge infrastructural gaps in cities of the global South (Nielsen and Eriksen Reference Nielsen and Eriksen2022; Anand et al. Reference Anand, Gupta and Appel2018; von Schnitzler Reference von Schnitzler2013; De Boeck Reference De Boeck2011; Simone Reference Simone2004), I argue that the agentive practices of citizens are also shaped and animated by a certain self-awareness of their marginal position within the global technological landscape. In doing so, I stress the critical self-awareness of Lomé’s makers of the global inequalities and inaccessibility of technological materials that influence their participation, as well as their various forms of resistance to it through their disavowal of bricolage and their reclaiming of the practice in mastering technological materials.

From May 2019 to June 2021,Footnote 7 I worked with Lomé’s young innovators, mobile phone repairers, electricians, children, university students and craftspeople to see how Lomé’s digital transformation influences the way they make their lives and their futures.Footnote 8 I followed these ‘makers’ as they navigate the city, from coding and prototyping workshops to apprenticeships and ‘black market’ transactions. Through multi-sited ethnography circumscribed within the digitalizing city, I traced assemblages of tech practices related to the global Maker Movement in their ideological and vernacular forms, such as hacking, making, prototyping, repair and bricolage, often leading to tense and ambiguous interpretations of these practices. This article specifically focuses on bricolage whose stigmatization in the West African region and beyond serves as a significant entry point to exploring these tensions.

I begin by situating Lomé’s Maker Movement within the city’s digital transformation, which, in turn, I locate within the digital economy of the West African region. I proceed to explore the discourses surrounding bricolage in Lomé vis-à-vis existing literature on the Euro-American Maker Movement, and frame the tensions between Lomé’s makers and bricolage through the e-waste narrative surrounding Lomé’s makerspaces and through the story of Afate Gnikou, the original maker of the W.Afate e-waste 3D printer. I then turn to more vernacular forms of bricolage in the city, such as araignée, and unpack Lomé’s makers’ critique of the concept through their resistance to the ‘e-waste innovator’ narrative and through their expression ‘we deserve new things’. Likewise, I look at how bricolage is reclaimed and revalued as a didactic tool, and conclude by reflecting on the affordance of ethnography to critique foundational concepts, as Lomé’s makers attempt to arrive at a future where bricolage is no longer a necessity but a choice.

Lomé, the digitalizing city

Togo is a small country nestled between Ghana and Benin, with a population of approximately 8 million. Its deep-water port is the only deep-water port in West Africa and has been the economic centrepiece of the country since its establishment as a wharf in 1904. Lomé was created as a port city by local and foreign traders and entrepreneurs who were eager to bypass the heavy taxes imposed by British customs on imports coming through the Gold Coast Colony in Ghana (Marguerat Reference Marguerat1992). Given the strategic position of the deep-water port in provisioning inland countries such as neighbouring Burkina Faso, the Togolese government aims to leverage its ‘logistical allure’Footnote 9 by transforming the port to become the premier financial-logistics hub of West Africa. As such, digitalizing the city of Lomé is seen as a viable investment that coincides with higher mobile penetration and a burgeoning youthful populationFootnote 10 that is eager to facilitate this transformation.

As was made explicit in the Plan National de Développement (PND) for 2018–22 and in Togo Digital 2025, the Togolese government believes that the future of Lomé lies in it becoming a logistics-financial hub fuelled by a strong banking sector, a modernized port and a robust digital economy spearheaded by the Ministère de l’Économie Numérique et de la Transformation Digitale (MENTD).Footnote 11 Lomé’s digital transformation has spurred major projects, such as the provision of wi-fi to the University of Lomé and the reinforcement of connectivity throughout the country through the West Africa Regional Communications Infrastructure Program (WARCIP).Footnote 12 In line with Lomé’s digital transformation and image branding, actors such as the US embassy and German development agency Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) have harnessed the discourses and ideologies of the Maker Movement to explore the potential of linking ‘making’ (through craftsmanship) with ‘technological initiatives’ (such as makerspaces and start-ups) in order to enhance opportunities for entrepreneurship and include both the artisanal and ICT sectors within the wider digital transformation project.

Nonetheless, the apparent lack of public funding serves as clear justification for private investments in major infrastructures. In the digital sector, Google is the major private investor through the submarine cable Equiano. The Equiano cable aims to provide internet connection throughout the African region as part of the multinational company’s US$1 billion investment, starting from Portugal and continuing all the way to South Africa. Togo is positioned as the first landing point of the cable in the region (see Figure 4) and is promised to benefit from the project through the creation of roughly 37,000 jobs and US$193 million in GDP.Footnote 13 Its claimed impacts are yet to be seen as the cable only landed in March 2022, and the majority of the population remains unable to access the internet due to its steep price, not to mention the lack of electricity to power its supply.

Figure 4. Submarine cable map of Lomé, Togo.

The belief in the messianic potentials of the digital economy is not confined to Lomé, and has spread throughout the African region. This is made visible through the proliferation of tech spaces, incubators and makerspaces, and the emergence of tech scenes in many African cities (see Pype Reference Pype and Musila2022). Led by the KINGS, which are believed to have the most advanced digital ecosystems in the African region (Osiakwan Reference Osiakwan, Ndemo and Weiss2017), the digital economy has vastly changed the continent’s digital landscapes through an upsurge of mobile penetration and internet connectivity.

However, despite the perceived potentials of the digital economy, there has also been much critique of its techno-centric discourse as an ‘ideology of the elite’ (Alzouma Reference Alzouma2005; see Graham Reference Graham2019). The internet and information society are often said to reflect colonial models and uneven relations between Euro-America and Africa, where African users are seen as disembodied ‘others’ whose subjectivities cannot be distanced from being Black and former colonial subjects (Moyo Reference Moyo, Muschert and Ragnedda2018: 136). For Clapperton Mavhunga (Reference Mavhunga2014), the importation of the Western meaning of science, technology and innovation can pose a serious threat to the African continent, as Africans have their own ways of being creative, technological and scientific. Instead, he suggests reformulating the question ‘How is technology changing Africa?’ to ‘How are Africans changing technology?’ (ibid.: 19), since Africans have long been contributing to the global technological landscape through their distinct innovations.

African governments’ focus on and investment in digital infrastructures have similarly overshadowed the provision of basic infrastructures. Through a case of leapfrogging, basic infrastructure development is believed to follow only as a consequence of digital infrastructure development. The lack of basic infrastructures continues to distress citizens through the presence of potholed streets, intermittent power supply, lack of access to potable water, and substandard health services. Vernacular manifestations of creativity and technological innovation nonetheless exist (Pype Reference Pype and Mavhunga2017; De Boeck Reference De Boeck2011) to counter the inaccessibility of basic infrastructures as well as the colonial and marginal experiences of African innovators in the global digital landscape. As the need to provincialize and decolonize global urbanisms becomes more pressing (Hart Reference Hart2018; Sheppard et al. Reference Sheppard, Leitner and Maringanti2013), postcolonial urban geographies such as Lomé serve as vantage points to advance critiques of the (neo)colonial globalization of digital technologies and its ideologies, through the existing urban practices of citizens who are taking matters into their own hands.

Bricolage in Lomé and the Maker Movement

Bricolage plays a foundational role in the Euro-American Maker Movement as a movement that is based on the DIY ideology of finding solutions through tinkering, repurposing or making something out of available resources (Resnick and Rosenbaum Reference Resnick, Rosenbaum, Honey and Kanter2013). Activities carried out within Euro-American makerspaces are often automatically identified as bricolage, and they possess the DIY dimension of putting together available materials without necessarily having any level of craftsmanship (Beltagui et al. Reference Beltagui, Sesis and Stylos2021). Bricoleurs are known to ‘scavenge’ resources from items discarded by others, and are keen on improvising, experimenting and innovating through a type of ‘frugal innovation’ performed out of economic necessity when optimal resources remain unavailable (Corsini et al. Reference Corsini, Dammicco and Moultrie2021). The bricoleur carries a strong Lévi-Straussian (Reference Lévi-Strauss1962) distinction from the engineer who systematically and scientifically plans their projects – a distinction that is recognized and even explicitly expressed by makers, innovation scholars and researchers of the Maker Movement (Beltagui et al. Reference Beltagui, Sesis and Stylos2021; Corsini et al. Reference Corsini, Dammicco and Moultrie2021; Resnick and Rosenbaum Reference Resnick, Rosenbaum, Honey and Kanter2013).

Bricolage, a word of French origin, is practised in makerspaces that bear similarities to ‘l’atelier du bricoleur’ in the 1950s (see Figure 5). L’atelier du bricoleur was a space established by the French magazine Système D (Le Système Débrouillard), a magazine for DIY projects founded in 1924 by the Société Parisienne d’Édition long before Make magazine and the Maker Movement brand (see Figure 6). Système D has a longstanding socio-cultural meaning in the French and Francophone contexts (Murphy Reference Murphy2015), stemming from its origin as a military concept for survival tactics used by the North African colonial army and during the First World War. The term eventually acquired its contemporary meaning of circumventing French bureaucratic red tape, as well as referring to various types of workarounds, ‘hacks’ or ways out of dire situations.

Figure 5. Rules for the atelier in Système D magazine, 1953.

Figure 6. Système D first print cover.

In Francophone Maker Movement circles, the Maker Movement is often translated as ‘le mouvement bricoleur’, the makerspace as ‘l’espace bricoleur’, maker-centred learning as ‘l’apprentissage centré sur le bricolage’ and the maker identity as ‘l’identité bricoleur’ (Cotnam-Kappel et al. Reference Cotnam-Kappel, Hagerman and Duplàa2020; Weber and Duplàa Reference Weber and Duplàa2018). Maker Movement scholars in Francophone Canada embrace the term bricolage to bridge the difficulty in translating the rather specifically American concept and ideology of ‘making’ in order to capture the essence of the ‘maker’ in its more democratic sense, as suggested by the tagline ‘Tout le monde peut faire du bricolage’ (Everybody can do bricolage). In their article ‘La formation bricoleur’, Cotnam-Kappel, Hagerman and Duplàa (Reference Cotnam-Kappel, Hagerman and Duplàa2020) argue that translating the Maker Movement to ‘le mouvement bricoleur’, instead of the more commonly used ‘le mouvement maker’ or ‘le mouvement des makers’, is a nod to the democratic spirit of the movement due to the wide range of activities that can be subsumed under the term ‘bricolage’. Calling the Maker Movement ‘le mouvement bricoleur’ allows for a certain sense of cognitive flexibility that can be adopted in various contexts, and can include activities that may or may not involve the use of technological tools.

It is important to note, however, that the bricoleur figure and the bricolage perspective in the Maker Movement remain largely based on the Lévi-Straussian definition (Beltagui et al. Reference Beltagui, Sesis and Stylos2021). In The Savage Mind, Lévi-Strauss (Reference Lévi-Strauss1962: 16–17) makes the distinction between the bricoleur and the engineer: the bricoleur is seen as someone who ‘makes do with whatever is at hand’ whereas the engineer carefully conceives of and reflects upon a given project prior to execution. The bricoleur is not entirely confined to the prescribed use of materials lying around but is adept at looking at the possible relations and alternative uses of existing materials – an ingenuity that is celebrated and extensively encouraged in the Maker Movement, especially in resource-constrained environments (Baker and Nelson Reference Baker and Nelson2005). Nonetheless, Lévi-Strauss stresses that the engineer ‘is always trying to make his way out of and go beyond the constraints imposed by a particular state of civilization’ (Reference Lévi-Strauss1962: 19), as opposed to the bricoleur, who, by inclination or necessity, is unable to surmount those constraints. It is this bricoleur figure and its various applications in the Maker Movement that Lomé’s makers nuance and complicate, through the various perceptions and practices of bricolage in Lomé and the (West) African region.

Système D and bricolage in Francophone Africa and Lomé

As is often the case with Western concepts in circulation, this rather celebratory understanding of the term ‘bricolage’ does not necessarily translate to the Lomé context. Bricolage in Togo possesses a more historical, socio-cultural and even colonial root of the term. For Togolese science and technology studies (STS) philosopher Yaovi Akakpo (Reference Akakpo2021), the Lévi-Straussian distinction between the bricoleur and the engineer is a result of colonial expansion and modernity, which positions, contrary to precolonial times, the ingénieur (engineer) as the highest form of profession.

Akakpo (Reference Akakpo2021) considers that the more artisanal forms of ‘débrouillardise’ (making do), given minimal resources, are a consequence of colonial expansion and economic liberalization, whose extractive nature in favour of imperial powers has left certain parts of the world ‘sous-développé’ (underdeveloped). Bricolage became an ingenious way of survival through improvisation that brought forth informal livelihoods and ‘professions’, such as taxi-moto drivers, poubellistes (rubbish collectors), walking sellers and repairers of shoes and second-hand electronics – and, to an extent, the unauthorized mobile phone repairers of the so-called ‘black market’ neighbourhood of Dékon. With the creation of professions involving bricolage, the distinction now lies between those who informally learn and practise bricolage technologique (technological bricolage) and those who formally learn technological practices in universities and technical schools.

Bricolage as débrouillardise is also common in other parts of Francophone Africa. Système D refers not only to the French magazine-cum-atelier but is considered a daily improvisational strategy and a way of life for those who live in precarious conditions and occupy ‘inferior social positions’ (Kleinman Reference Kleinman2019: 103). As the French magazine Système D also drew its name from the French approach to life, Système D became synonymous with bricolage and the hodgepodge of existing materials, of making something out of nothing through cunning ways of navigating the scarcity of resources in the region.

As the concept of Système D or la débrouillardise travelled and was translated into practice in Francophone colonial and postcolonial regions, it is depicted as a form of African inventiveness in the face of precarity. In Mali and Senegal, for instance, la débrouillardise became a means of navigating the strictures and pauperization caused by the structural adjustment programmes of the 1990s to the point of it entering popular culture through cartoon characters such as Goorgoorlu (débrouillard in Wolof) (Murphy Reference Murphy2015; N’Diaye-Correard et al. Reference N’Diaye-Correard, Daff, Mbaye and Ndiaye2006). In the Democratic Republic of Congo (then Zaire), Système D was translated into the imaginary Article 15 of the Mobutu constitution that states: ‘Débrouillez-vous pour vivre’ (Make do to survive) (Murphy Reference Murphy2015; MacGaffey Reference MacGaffey and Nzongola-Ntalaja1986). Just as Filip De Boeck and Sammy Baloji (Reference De Boeck and Baloji2016) make use of ‘suturing’ to refer to the reworking and reassembly of the degrading postcolonial urban fabric in Congo, la débrouillardise, bricolage and the reworking of existing materials became the sine qua non of navigating the urban African landscape.

Bricolage also possesses a rather distinct socio-historical function for apprenticeships in Togo that goes beyond mere débrouillardise. As outlined by Akakpo (Reference Akakpo2021), bricolage is associated with the customary ways of learning artisanal métiers (crafts) such as blacksmithing, weaving, carpentry and pottery. Bricolage is used to describe the workings of the apprentice who is still in the process of learning and mastering a craft. The difference between bricolage and professional craftsmanship is a matter of technical competence, with the master being the professional and the apprentice the bricoleur. While a hierarchy seems to remain between the master and the apprentice, craftsmanship in Togo is seen as a collective effort that recognizes the necessity of the master and apprentice working together – the former with professional expertise, and the latter with bricolage.

This understanding of bricolage as identified with learning and apprenticeship is also one that is shared by Lomé’s makers. In the words of one makerspace founder, ‘Making is not bricolage, but makers make use of bricolage.’ As a didactic tool for exercising creativity, prototyping workshops are often called ‘l’atelier du bricolage’, where the makers stand as facilitators and the participants as bricoleurs. In such instances, bricolage remains a process-oriented activity and the participant-bricoleur identifies as someone who tries but has not quite mastered his craft. ‘Bricolage, ce n’est pas un métier. Ce n’est rien [Bricolage is not a craft. It’s nothing],’ said one of the workshop facilitators. ‘Il n’y a pas de valeur dans le bricolage [There is no value in bricolage].’ It is within this understanding of bricolage in Lomé as an engagement associated with apprentices and as an undervalued response to the scarcity of resources that I frame the ambiguous relationship of Lomé’s makers with this specific practice.

‘World leaders in e-waste management’: Lomé’s makers and media narratives

Feature stories run by international media outlets cemented the global presence of Lomé’s makers as ‘world leaders in e-waste management’ or as ‘innovators’ who turn the ‘world’s junk’ and ‘toxic e-wastes’ into robots and 3D printers.Footnote 14 Stories about Lomé’s innovative e-waste practice feature how the invention and global recognition of W.Afate, an e-waste 3D printer from makerspace WoeLab, has inspired other young makers, tech entrepreneurs and bricoleurs to join the makerspace in the hopes of making their own 3D printers and participating in the global Maker Movement. These stories often contextualize Togo as an agriculture-centred country where the majority lack access to resources and technological equipment. E-waste is romanticized as a formidable, albeit toxic, alternative to boost young makers’ creativity in coming up with innovative tech projects.

In these media narratives, the becoming of Lomé as ‘la ville de demain’ (the city of tomorrow) is led by WoeLab and its many techno-utopian projects for waste management such as HubCité and UrbanAttic.Footnote 15 The focus on changing the face of the city through the reworking of wastes is said to turn ‘Lomé la poubelle’ (Lomé the trash), a slight coined by the Loméans to refer to the city’s waste mismanagement, to ‘Lomé la belle’ (Lomé the beautiful), the city’s actual promotional tagline. The international reputation that WoeLab and other makerspaces have created for themselves through W.Afate and other e-waste prototypes has unwittingly contributed to the image branding of the city as the ‘next digital hub of West Africa’.

Despite Lomé’s makerspaces being consulted for the city’s digital strategy, they are rarely considered as key players in its digital transformation. The success stories media outlets portray of these makerspaces contribute to a certain level of misrepresentation of their actual state, as they often feel pressured to live up to the expectations the media has generated. For the makerspace founders, media narratives mask the struggles Lomé’s makerspaces face on a daily basis, which often include funding shortages, lack of government support, inability to connect with the local population, and the dwindling interest in the Maker Movement itself – something that has been happening globally, as evidenced by the closing down of major makerspace brands such as Techshop in 2017.

The depiction of Lomé’s makers as forerunners of e-waste innovation likewise overshadowed their other projects, such as free coding workshops for disadvantaged children, robotics and design thinking workshops, sustainable urban gardening initiatives and start-up pitching clinics, among others. The painting of an overly rosy picture of Lomé’s makerspaces masks the reality that the spaces remain empty and inaccessible for the majority of Loméans who are more preoccupied with making ends meet than learning new digital skills. ‘Lomé is not ready for a Maker Movement,’ as one makerspace founder said. ‘People still need to find food to eat before participating in robotics workshops.’ Lomé’s makerspaces struggle to keep their spaces afloat, only to be replaced by start-ups and incubators, some of which are government-sponsored and are geared more towards money making, compared with the community-driven tinkering practices at the core of makerspaces since their inception.

Afate’s story: the ‘maker’ and bricolage

The relationship between the ‘maker’ and bricolage in Lomé is an ambiguous one, primarily due to the socio-historical construction of the concept and the inequality and underdevelopment it reveals as a necessary practice. It is also through this ambiguous relationship with bricolage that Lomé’s presence in the global Maker Movement is established. This ambiguity is nicely captured in Afate Gnikou’s story, the original maker and inventor of the e-waste 3D printer W.Afate.Footnote 16 He shared his story with me in his makerspace WouraLab, which he was slowly building by hand, one concrete block at a time.

As in most origin stories of Lomé’s makers, Afate Gnikou was fascinated with bricolage as a young boy. He remembers watching his older brother tinker with the radio and was inspired to put together electronic parts himself even without formally learning how to do so. While he went on to obtain a baccalaureate in arts and letters, and to graduate with a degree in geography from the University of Lomé, his love for bricolage did not leave him. He would make montages of computers and collect and stack CPU frames until he had a good use for them. He has the air of an engineer who obsesses over the details of things that interest him, and he admits to having a particular fascination with 3D printers after attending a 3D printing workshop in 2012 in the then newly opened WoeLab. ‘The thing that attracted me to 3D printers is their simplicity,’ he said. This led him to volunteer to make a 3D printer project for WoeLab, which he worked on together with three friends who share the same interest (see Figure 7). But alas, the 3D printer kit that they were supposed to assemble did not arrive, and so they chose to build the 3D printer with the materials they had at hand, including the CPU frames he was collecting.

Figure 7. Afate Gnikou in WouraLab, with maker friends Bataba Bawelé and Ousia Foli-Bebe.

Impressed by Afate’s dedication to the project, WoeLab founder Senamé Koffi Agbodjinou started a crowdfunding campaign and connected with media journalists to run the story about the ‘e-waste’ 3D printer Afate was making. Afate was hired by WoeLab and given a salary for six months just to work on the 3D printer prototype. His friends, who later built their own makerspaces across West Africa, worked on the software for the 3D printer – software that had to accept the e-waste parts and not reject them, as is often the case with Euro-American 3D printing software. The prototype was finished in 2013 and was first exhibited in Côte d’Ivoire. After receiving positive feedback, it was presented at the Global Fab Lab Awards in Barcelona in 2014, where it won the Best Innovation award – and the rest was history. W.Afate remains open source to date and can be freely recreated (see Figure 8). The reason behind this is simple, Afate says: ‘I developed W.Afate thanks to open source. I’m just giving back [to open source] so that others can improve on it and make other projects.’

Figure 8. W.Afate recreated by Ecotec Lab.

As a result of ‘making do’ with available resources, Afate’s re-reading of the e-waste material – the discarded CPU frames and wires he was collecting – made his 3D printer prototype a success in Maker Movement circles. The irony, though, at least according to Afate’s story, is that it was not his original intention to build the 3D printer from e-waste. The materials for the 3D printer simply did not arrive. Afate was both limited and empowered by his circumstances of not having access to optimal materials, and he surmounted these limitations through his ability to imagine alternative readings and assemblages of existing materials to come up with an ‘e-waste innovation’ that has never been attempted or materialized in other makerspaces. This combination of necessity and ingenuity through bricolage that exposes inequalities more than it hides them is exemplified not just by Lomé’s makers but also by the citizens at large, as can be seen in the remarkable example of araignée (the French word for ‘spider’).

Bricolage in the city and beyond: the case of araignée

Fozie, Yao and I were walking one Sunday afternoon from Fozie’s house on the outskirts of Lomé to the taxi-moto rank that would bring us back to the city. Fozie’s father invited us to visit their home after we were introduced to him in Dékon,Footnote 17 where he works as a seller of car spare parts, and Fozie as a mobile phone repairer. Fozie’s mother prepared a sumptuous meal of beef and red sauce with sorghum flour, which we happily devoured under the sun with fresh soft drinks and ice water. The meal was more than enough for us and we were ready for our trip back to the city, but not until we took a few photographs and a selfie with Fozie’s little brother, who unfortunately passed away a few months later at the height of the Covid-19 pandemic.

While the three of us were walking, I was stopped in my tracks by a contraption of overhead power lines that seemed to be connected in no logical way. It reminded me a bit of my home town in Manila, where I find similar contraptions, usually created by illegally connecting to neighbours’ electricity transmission through electrical jumpers. My friends followed my gaze as I looked at the lines of electricity wires with both awe and confusion. ‘C’est l’araignée, hein [It’s araignée]!’ they explained to me. ‘Ils ont bricolé tout ça [They made a bricolage out of it]!’

According to my companions, araignée is an ingenious and artisanal but rather illegal way of connecting electricity lines (see Figure 9). The confusing array of cables and the artisanal ‘finish’ made araignée a type of bricolage, a means of ‘making do’ for those who would not have access to electricity if not for this type of illegal contraption. One of the makerspace founders in Lomé even commended the ingenuity of araignée and compared it to how they also try to hack their neighbour’s wi-fi to power their makerspace through what they call a ‘handshake’, or the decrypting of wi-fi passwords via wireless access points.

Figure 9. Araignée in Lomé’s outskirts.

As Akakpo (Reference Akakpo2021) writes on the societal role of bricolage, the phenomenon of araignée contributes to the urban planning (aménagement du territoire) of rural peripheries as a bottom-up response to state neglect in providing basic infrastructures:

It is important to note that these ‘technologies de bricoleur’ have a massive social function, because the rural or peripheral areas that are inhabited by social categories employed in all national economic sectors are not covered by electricity or water services. (Akakpo Reference Akakpo2021: 11, my translation)

While araignée as bricolage serves its function, it remains devalued as something that is not professionally, legally or skilfully done. When I asked a friend who started working as an electrician about bricolage in electric wiring, he said that if someone has not done a good ‘finish’ when installing electric wires in a house, even if they were a professional, they would still call it bricolage in the same vein that they would call araignée a type of bricolage. If someone points to electric wiring in the house that seems haphazardly done, despite the wiring being fully functional, one might say ‘Tu as bricolé ça [Did you make a bricolage out of this]?’ For electricians, this is never to be taken as a compliment.

Being a form of ‘African inventiveness’ for those confronted with the absence of basic infrastructures, bricolage consequently contributes to modernity (Akakpo Reference Akakpo2021) through the innovations and personal initiatives people take to access resources out of necessity. As several infrastructure scholars have pointed out, bricolage becomes a response to infrastructural gaps as people try to hack infrastructures or make infrastructures out of their social networks to circumvent the lack of resources in certain situations (Nielsen and Eriksen Reference Nielsen and Eriksen2022; Anand et al. Reference Anand, Gupta and Appel2018; von Schnitzler Reference von Schnitzler2013; Simone Reference Simone2004). Nonetheless, bricolage also motions towards a certain aesthetics, or lack thereof, that relegates it as a practice of low or inferior quality made solely to transcend limitations within resource-constrained environments by ‘making do’ with what is available.

As a practice of inferior quality that settles for mere functionality in instances of lack, bricolage as African inventiveness can also appear as a romanticized practice. What bricolage actually stresses is the underlying contradictions of digital infrastructure development and the unequal access to materials and infrastructures that has made bricolage a necessary engagement for survival (Akakpo Reference Akakpo2021: 11). While the conception – and, to an extent, the stigmatization – of bricolage in Lomé relates to differentiating technical competence, another understanding of the concept to which Lomé’s makers are also responding through disavowal is the global inequality and underdevelopment that necessitates bricolage. Lomé’s makers want to break away from the e-waste innovators stereotype in order to assert their participation in modernity – a participation that is neither purely African nor purely Western (Wiredu Reference Wiredu and Wright1984), but one that is cognizant of Lomé’s makers being creative innovators and entrepreneurs living in a milieu that allows them to be cosmopolitan, and to engage in global modernity through their own capacity and understandings of it, and where they can work with optimal materials and not just waste.

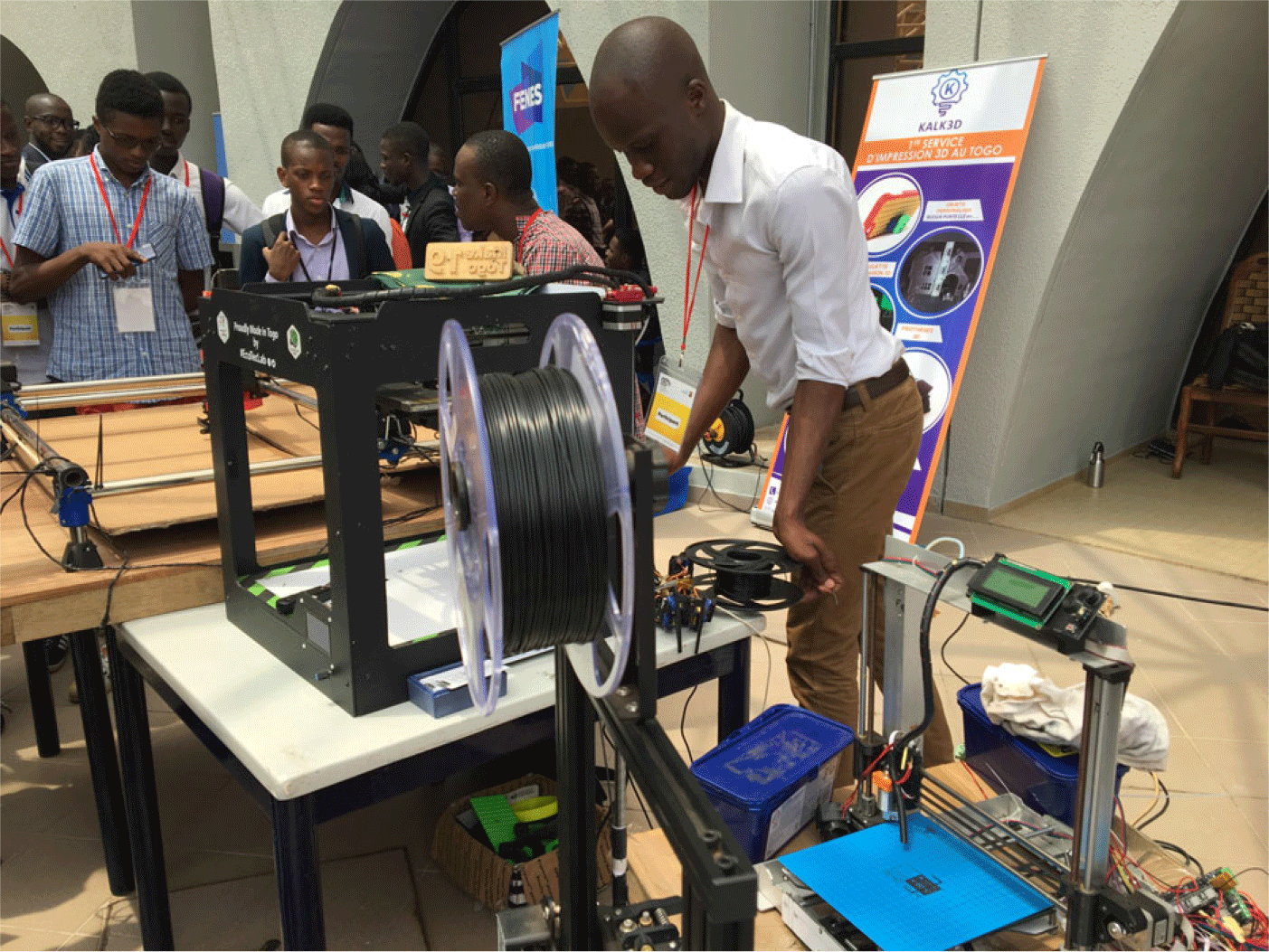

Ousia Foli-Bebe, one of Afate’s friends who helped with the W.Afate prototype, established his own makerspace after their brief stint with WoeLab. As an environmental scientist, Ousia combined his knack for tinkering and his passion for addressing ecological issues to establish Ecotec Lab (Ecology Technology Lab), a makerspace that aims to promote environmentally oriented projects such as air pollution sensors and solar panels. Eager to break away from the e-waste stereotype, Ousia decided to build his own 3D printer whose parts were printed using the W.Afate (see Figure 10). He goes around secondary and technical schools in Lomé to promote the ‘maker culture’, bringing both the W.Afate e-waste printer and the newer ‘shinier’ 3D printer with him to showcase how both can be made using old and new materials. As he demonstrates, bricolage can pave the way for accessing new materials through the reassembly of old ones. With the W.Afate, new 3D printers and other prototypes are now being built in Lomé from scratch.

Figure 10. Ousia mounting his new 3D printer prototype at Lomé’s Tech Expo 2019.

‘We deserve new things’: (anti-)bricolage for Lomé’s makers

When I first came to Togo to visit the makerspaces, I also naively fell into the trap of the e-waste narrative and began by asking about their e-waste prototypes and their influence on the community, as I initially intended to do with the research project. It caught me by surprise when one of the founders openly said, ‘We don’t want our stories to be about e-waste any more, we can do more than that. They should stop sending us e-waste to see what we can do with them. We deserve new things.’ As I spent more time with Lomé’s makers, many other things with which they do not wish to be associated became clearer. ‘We are makers, but not bricoleurs’ is how they introduce themselves to workshop participants, students at the lycée technique, and all those interested in working with them, but who are also familiar with the notion of bricolage in vernacular discourse.

For the students and workshop participants who are familiar with Lomé’s makerspaces, they immediately understand the intentional distancing of Lomé’s makers from bricoleurs and bricolage. As a form of débrouillardise, of ‘making do’ to survive, the disavowal of the term appears more as a critique of the practice employed by those living in precarious conditions that sacrifices quality for functionality in order to achieve the bare minimum. Citing araignée as an example, one of the makerspace founders mentioned that this settling for functionality over quality is because people are ‘looking for the easy way out’, a band-aid fix even if they know and deserve better. In addition, the stigmatization of the concept is also something that is seen as a product of an educational system that has reinforced the primacy of theory over practice, and where craftsmanship and working with the hands is valued less and less. As one university engineering student puts it: ‘C’est l’école qui efface la concept de bricolage [It is schooling that erases the concept of bricolage].’

Formal education in Togo remains largely patterned after the colonial Francophone educational system that has been widely criticized by Lomé’s makers, students and educators for asserting the primacy of theory over practice. According to one of the early members and co-founders of Ecotec Lab, Bruno Kataba, this preference for theory over practice contributes to the diminishing status of bricoleurs and craftspeople and influences the initiative of a person to do and repair things themselves. It also hinders students from finding practical solutions to problems as they are limited by their theoretical orientation, rarely seeing the objects and tools they are studying in order to apply what they learn in practice. Because of this, Ecotec Lab started promoting what they call ‘maker-based learning’ to schools through hands-on workshops and demonstrations, bringing with them prototype 3D printers and circuits for the students to learn and tinker with. In these demonstrations, they also begin by writing ‘maker’ on the board to introduce themselves as ‘makers but not bricoleurs’ (see Figure 11).

Figure 11. Ecotec Lab doing a 3D printing demo in a lycée technique.

This dissociation from bricolage not only applies to Lomé’s makers, but also to the ‘professional bricoleurs’ Akakpo refers to – those whose professions are by-products of ‘making do’, such as the mobile phone repairers of Dékon. The mobile phone repairers do not identify the way they repair phones as bricolage despite it appearing as such, given that they rely on second-hand phones or tout risque (all risk) phones for spare parts. Tout risque phones are mobile phones disposed of in Europe or the USA and are no longer properly functional, but they can still be salvaged and reworked for spare parts and are bought by mobile phone repairers in bulk for 30,000 CFA (US$50) a box. Similarly, tout risque phones are the materials used to teach apprentices about the inner workings of mobile phones in order to master the material without the risk of doing further damage. As such, the mobile phone repairers and apprentices consider their work to be a real profession, worth the time and effort they have put into honing their skills. Mobile phone repair in Dékon, despite being labelled as ‘unauthorized’ (non-autorisée) by official service centres, has value and can be exchanged for a price, and is not at all a form of bricolage – an undervalued practice that repairers and makers think nobody is willing to pay for.

Anti-bricolage as a critique on global inequalities

Lomé’s makers both embrace and disavow bricolage as a means of positioning themselves within Lomé and in the global Maker Movement. Lomé’s ‘makers’ (who make use of the term in English) confront the contradictions of bricolage by negotiating its value and their relation to it. While their disavowal exacerbates the stigmatization of the practice as a devalued engagement that sacrifices quality over functionality, they similarly recognize that their being in the global margins of access to technological materials makes bricolage inescapably necessary.

In Euro-American Maker Movements, bricolage is celebrated for being innovative and is seen as an alternative to industrial production and corporate value capture through DIY thinking and tinkering, and even as a political choice (Davies Reference Davies2017; Kostakis et al. Reference Kostakis, Niaros and Giotitsas2015). It is often depicted as a choice or a personal initiative where one can ‘make’ or ‘repair’ something oneself and exercise or hone problem-solving skills. In comparison, bricolage is seen as a necessary engagement in cities such as Lomé where inaccessibility can be countered through informal, ingenious and sometimes illegal ways. The necessity of bricolage becomes symptomatic of wider structural issues, of the lack of basic infrastructures, and of a notable digital divide that Lomé’s makers attempt to straddle. Makerspaces operate on hacked wi-fi and make use of e-waste 3D printers, exemplary products of bricolage that carry with them a contradiction particular to Lomé’s makers: they make innovations that are on a par with global standards, accomplishing feats that merit international recognition, yet they remain within the margins of access, only to reveal the inequalities within which their innovations were birthed. As one makerspace founder claims, ‘They [international media outlets] want us to appear successful so they don’t have to help us or acknowledge our problems. But in reality, we struggle every day.’

As bricolage is devalued through its association with mere functional practice for creative survival, moving away from the concept can be seen as a radical response that moves to the fore what Lomé’s makers are really distancing themselves from: the necessity of having to settle for meagre available resources in their unequal access to technological materials. Anti-bricolage is an expression of their desire for a future where bricolage is no longer a necessity, where materials are readily available, and where the playing field for tech innovation is levelled because Lomé’s makers also ‘deserve new things’.

Reclaiming the value of bricolage

One of the students participating in l’atelier du bricolage suggested that bricolage should be revalued and reclaimed as a venue for creativity in makerspaces, and as a practice that has been part of the Loméan way of life. Lomé’s makers try to redefine ‘making’ as ‘bricolage but quality’ to negotiate the ambiguity and reclaim its value. As Ecotec Lab founder Ousia Foli-Bebe explains:

Because people perceive bricolage not as a good thing or something valuable, we tell them, ‘Okay, what we do here is “making”. And making is bricolage, but quality.’ We try not to equate bricolage with low quality but more like finding solutions with existing material. Bricolage, in a way, is ‘to try’ … which is a good start.Footnote 18

This revaluing of bricolage is made more apparent in how it is employed as a didactic tool in Lomé’s makerspaces in the spirit of its socio-historical value in apprenticeship. There is an affective-sensorial quality to learning through a practice that has inspired them as children, and that they have carried out not just to ‘make do’ but also ‘to try’: to explore, to make mistakes and to make something new out of materials lying around. Bricolage provides for a more hands-on approach to learning, as can be seen in prototyping workshops called ‘l’atelier du bricolage’, often involving trial and error without the pressure of having to arrive at a finished product. This is similarly the role of tout risque phones for the mobile phone repair apprentices of Dékon, which give them the liberty to tinker, hack, disassemble and repair.

Despite bricolage being revalued for its didactic promise, the inaccessibility of materials remains a hurdle that sometimes makes learning through bricolage an unpleasant experience. In one of the vacances utiles (summer workshops) for children aged eight to fourteen, they were asked to make a prototype of a mini traffic light using the available tools. At that time, there was only a very limited range of tools and equipment the makerspace could provide: only red LED lamps for the three lights and cardboard for a circuit board. This lack of materials to make a traffic light prototype was evidently frustrating for the children. The three red lights refused to function and the cardboard was not a good conductor for the circuit. Disheartened by the exercise, they kept saying: ‘On a essayé, essayé, essayé, ça ne marche pas [We tried and tried and tried, but it still did not work]!’ In this instance, creativity can only do so much amidst the lack of materials. Bricolage was no adequate solution to the shortage of resources; appropriate teaching materials could have allowed the children to explore their creative potential to its fullest and revel in a fully functioning traffic light prototype.

Conclusion: decolonizing bricolage

Lomé’s makers’ ambiguous relationship with bricolage is premised on its socio-historical function, and on it being a necessary practice for creative survival that sacrifices quality over functionality. In contrast to its Euro-American conception as a form of creative tinkering exercised within makerspaces, bricolage in Lomé is seen as a necessary engagement carried out by those living in precarious conditions and at the margins of access to materials and infrastructures. Yet it is also through bricolage and the ingenious use of existing materials such as e-waste that Lomé’s makers made a name for themselves in the global Maker Movement, forcing them to confront the role of bricolage in their maker identity through their own understanding and interpretations of it.

As Lomé’s makers insist on moving away from bricolage through their clamour for new things, their disavowal of the concept stands as a political critique of its being a mark of underdevelopment and inequality brought about by (neo)colonial expansion (Akakpo Reference Akakpo2021). What Lomé’s makers are pointing towards in their anti-bricolage stance is a future where bricolage is no longer a necessity but a choice, where they have access to optimal materials and not just discarded ones, and where their world-class skills are recognized through the levelling of the digital landscape and their positioning as central cosmopolitan innovators, not just as e-waste innovators from the global digital margins.

Lomé’s makers employ bricolage as a means of exploration in order to learn and master technological materials. They reclaim the value of bricolage as a didactic tool through l’atelier du bricolage and their redefinition of ‘making’ as ‘bricolage but quality’. This redefinition recognizes that, despite bricolage being ‘trucs d’enfants’ or child’s play, it is also an engagement that has been inspirational for makers since their first encounters with it during their childhood, learning from their own creativity and imagination just as Maman’s kids learn by playing with iron rods.

More importantly, Lomé’s makers offer a critique on bricolage by nuancing a particularly foundational concept in the global Maker Movement and in academic discourse. Their resistance to being labelled ‘bricoleurs’ and their attempts to counter narratives that celebrate their marginal access to materials give insight into the agentive capacity of critical self-awareness, and the possibility to co-produce critique in making central the words and lived experiences of our interlocutors. By unpacking Loméans’ identification as ‘makers but not bricoleurs’ and their demand for deserving ‘new things’, I explore how ethnography affords epistemic resistance to foundational concepts and their inherent coloniality (Akakpo Reference Akakpo2021; Bejarano et al. Reference Bejarano, López Juárez, Mijangos García and Goldstein2019; Wiredu Reference Wiredu2002) in order to contribute to the decolonial moment in anthropology and other disciplines. As tides begin to shift through digital and decolonial transformations, only time will tell where critique and creative imaginations might lead.

Janine Patricia Santos is a PhD candidate from the Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology, KU Leuven Belgium. She is part of the wider research project CityLabs – Inventing the Future, which looks at ‘making’ in/of cities and futures in four African cities: Accra, Nairobi, Cape Town and Lomé.