Americans today live in an era in which nearly all observers of the legal process acknowledge the key role of ideology and political values in the decisionmaking processes of U.S. Supreme Court justices. As two of the most prominent analysts of the Supreme Court observed: “Simply put, Rehnquist votes the way he does because he is extremely conservative; Marshall voted the way he did because he was extremely liberal” (Reference SegalSegal & Spaeth 2002:86).Footnote 1 Even if some debate exists about the degree to which the policy choices of justices are constrained by legal and extralegal factors (e.g., Reference Bailey and MaltzmanBailey & Maltzman 2008; Reference Black and OwensBlack & Owens 2009; Reference Caldeira and WrightCaldeira & Wright 1988; Reference Richards and KritzerRichards & Kritzer 2002), no serious analyst would today contend that the decisions of the justices of the Supreme Court are independent of the personal ideologies of the judges. In this sense, legal realism has carried the day.Footnote 2 Indeed, as Reference PackerPacker (2006:83) and others (e.g., Reference PellerPeller 1985; Reference SingerSinger 1988) have put it: “We are all realists now.”Footnote 3

Yet it is not uncommon to find judges who deny that their own ideological and policy preferences shape their decisions. Justice Antonin Scalia has stated, for instance, “To hold a government Act to be unconstitutional is not to announce that we forbid it, but that the Constitution forbids it. … Since the Constitution does not change from year to year; since it does not conform to our decisions, but our decisions are supposed to conform to it; the notion that our interpretation of the Constitution in a particular decision could take prospective form does not make sense” (American Trucking Assns., Inc. v. Smith 1990, 496 U.S. 167, 201; (Scalia concurrence).Footnote 4 During her confirmation hearings, Judge Sonia Sotomayor similarly described a process of judging quite at odds with the depiction of the legal realists, most likely reflecting a strategic decision by Judge Sotomayor and President Barack Obama's political advisors to advance the image of discretionless judging and judges who merely “implement” the law, in part in reaction to attacks on President Obama's comments about needing judges with “empathy” on the Supreme Court. Judge Sotomayor's description of judicial decisionmaking—in particular, her depiction of the process as one of mechanical jurisprudence—set off some furious criticism by legal scholars (e.g., Reference MauroMauro 2009). Some even accused her of lying (Reference DworkinDworkin 2009). Asking what can be done about judges misrepresenting their actual processes of decisionmaking, Dworkin answers: “Nothing, I fear, until the idea that judges' personal convictions can and should play no role in their decisions loosens its grip not just on politicians but on the public at large” (Reference DworkinDworkin 2009: http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2009/sep/24/justice-sotomayor-the-unjust-hearings/?page=3).

There may be many reasons why the truth of judicial decisionmaking may be thought to be threatening to judges and courts, but one is certainly that the realist view of judging is in some sense a danger to judicial legitimacy, especially the legitimacy of the federal courts.Footnote 5 Reconciling extending life tenure to judges, while allowing the power of judicial review, all within the context of democratic governance, has long been a concern of legal theorists. An easy solution to judicial policymaking's legitimacy is to provide for accountability to the majority, a route most of the American states have taken, in one form or another, with their judges. A more difficult (but still not too difficult) solution is provided by theories of mechanical jurisprudence (Reference PoundPound 1908), more recently dubbed the “myth of legality”—“the belief that judicial decisions are based on autonomous legal principles” and “that cases are decided by application of legal rules formulated and applied through a politically and philosophically neutral process of legal reasoning” (Reference Scheb and LyonsScheb & Lyons 2000:929). If judges are merely interpreting and applying law, largely through syllogisms and stare decisis, the threat to judicial legitimacy dissipates; judges are simply doing what they are supposed to do (see Dworkin above).Footnote 6 Denying judicial discretion pre-empts the need for direct political accountability and enhances judicial legitimacy.

But is the realist model of judicial decisionmaking, in which judicial ideologies and values play a large role in policymaking, really incompatible with the popular legitimacy of the Supreme Court? Although this seems like a simple question, in fact little extant empirical research has attempted to provide answers. And the American people's views of how Supreme Court justices make their decisions are likely more complicated than simply specifying the answer as “yes, they rely on their own values, and are therefore not legitimate” or “no, they strictly follow the law, ignoring their own values, and therefore are legitimate.” Moreover, the empirical literature presents some important puzzles and unexplained findings and processes, suggesting that the views of the American people are more complex and perhaps even more sophisticated than typically imagined.

From existing research on public attitudes toward law and courts, legal researchers know that, generally, to know more about courts is to hold them in higher esteem. This finding holds in many parts of the world (e.g., Reference Gibson, Caldeira and BairdGibson, Caldeira, & Baird 1998), including the American states (Reference BeneshBenesh 2006). But the meaning of this simple empirical relationship is far from simple to understand.

The puzzle is this. Presumably, those who know more about courts know more about the realities of how courts actually operate and how judges actually make decisions, and they therefore accept some version of legal realism because it is a veridical description of decisionmaking.Footnote 7 But if realism undermines legitimacy, how do the most knowledgeable citizens simultaneously extend greater legitimacy to the Court while at the same time believing in some version of realism? Put statistically, to the extent that increased awareness of courts is positively correlated with a more realistic understanding of how judges make decisions, and to the extent that the realist reality is that judges are policy makers who rely on their own values in making decisions, awareness should be negatively—not positively—correlated with institutional support. That positive correlations are so routinely found must indicate some sort of break in the presumed causal chain. Either knowledge does not produce a realistic understanding of decisionmaking, or legitimacy does not depend upon citizens being duped into believing in theories of mechanical jurisprudence and the myth of legality. This is the conundrum we address in this article.

The purpose of this article is therefore to investigate the relationships among knowledge of the Supreme Court, popular beliefs about the nature of judicial decisionmaking, and willingness to ascribe legitimacy to the Supreme Court as an institution. The theoretical framework for this analysis is the well-known legitimacy theory.Footnote 8 In brief, the theory asserts that: (1) courts are uncommonly dependent upon legitimacy because they have few institutional means of ensuring compliance with their decisions (no purse, no sword); (2) courts value legitimacy highly because legitimacy includes a presumption that decisions, even unpopular ones, ought to be accepted and complied with; and (3) legitimacy depends upon the courts not being viewed as just another political institution; instead, it requires that ordinary citizens distinguish between what judges do and what other politicians do. Empirically, we consider four questions: (1) Does knowledge increase institutional support? (2) Does institutional support depend on belief in the myth of legality? (3) To what view of judging do the most knowledgeable citizens subscribe? and (4) Is the knowledge-support relationship mediated by distinctive views of how judges go about making decisions? We begin with an overview of the empirical findings on the legitimacy of the Supreme Court, the ways in which knowledge enhances legitimacy, and the limited findings on popular belief in the myth of legality.

Institutional Support for the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court is a widely legitimate institution. Reference Gibson, Caldeira and BairdGibson, Caldeira, and Baird (1998) have established this conclusion in comparative perspective, and it has been reconfirmed with additional data since then (e.g., Reference GibsonGibson 2007a). The Supreme Court is not unique in its store of legitimacy—the German Federal Constitutional Court (FCC) enjoys just as much legitimacy—but few courts in the world have accumulated more institutional support than the Supreme Court.Footnote 9

That support is resistant to change. Even highly controversial decisions such as Bush v. Gore (2000) seem not to detract from the support people extend to the Court.Footnote 10 Indeed, the title of a recent paper asks the question: “Is the Supreme Court Bulletproof?” (Reference FarganisFarganis 2008). Extant research suggests few avenues through which the legitimacy of the Supreme Court might be threatened.

An exception to this general finding has recently been discovered by Reference GibsonGibson and Caldeira (2009), who found that the politicized advertisements broadcast both in favor of and in opposition to the nomination of Judge Samuel Alito to the high bench undermined the Supreme Court's legitimacy. Gibson and Caldeira speculate that the message of these ads was that the Supreme Court is just another political institution, and that citizens exposed to that argument were less likely to extend support to the Supreme Court. They contend that the Court is best able to maintain its legitimacy by pointing toward its distinctive “nonpolitical” role in the American political system.

Not all U.S. governmental institutions enjoy the same level of popular approval and support as the Supreme Court, and cross-institutional differences may have something to do with perceptions of decisionmaking processes. Congress in particular is often the object of popular disdain. According to Reference HibbingHibbing and Theiss-Morse (2001), Congress's problem is that ordinary people see its processes of decisionmaking as unprincipled and self-interested. The comparative advantage of the Supreme Court may be that its decisionmaking processes are viewed as principled and impartial and therefore to some extent fair and just (see Reference RamirezRamirez 2008). Whether people perceive this procedural fairness as grounded in mechanical jurisprudence is unclear and worthy of additional empirical investigation. What is clear, however, is that ordinary people assess Congress and the Supreme Court differently, and the way that decisions are made likely has something to do with this difference.

Thus, the Supreme Court profits from a large store of reasonably stable institutional support. To the extent that there is a threat to that support, it comes from events that challenge the view of the Court as a uniquely nonpolitical political institution.

To Know the Court Is to Love It

A considerable body of research, conducted throughout the world, indicates that greater knowledge of judicial institutions is associated with a willingness to ascribe greater institutional legitimacy. For instance, Reference Gibson, Caldeira and BairdGibson, Caldeira, and Baird (1998) show that the most knowledgeable citizens in about 20 countries are most likely to extend support to their high court. And the impact of knowledge is independent of satisfaction with the short-term outputs of the court.

Legal researchers also understand something of the process by which knowledge enhances support. According to positivity theory, as advanced by Reference GibsonGibson and Caldeira (e.g., 2009), greater knowledge of courts is associated with greater attentiveness to them and, concomitantly, with greater exposure to the legitimizing symbols typically attached to courts.Footnote 11 It seems that knowing about courts often means knowing that courts are special institutions, different from ordinary political institutions, and, as such, that they are worthy of the esteem of the citizenry. Whatever the precise process involved, more knowledgeable people are inevitably more supportive of courts.

Knowledge and the Myth of Legality

At the same time, however, a reasonable hypothesis posits that greater exposure to the judiciary is associated with a more realistic view of how courts and judges actually operate. Exposure to courts should be associated with the understanding that judges have discretion when they render their decisions, that decisionmaking involves far more than “applying” the law to the facts in a mechanical or syllogistic fashion, and that judging inevitably involves and implicates judges' personal values. To know more about courts is therefore to know that collegial courts like the Supreme Court often, if not typically, render divided and, on occasion, deeply and bitterly divided, decisions. If judges cannot agree on what the law is, then belief in mechanical jurisprudence is difficult to sustain (see Reference ZinkZink et al. 2009).

Paradoxically, however, the available evidence indicates that greater political knowledge is associated with a less realistic view of how courts actually operate. For instance, long ago, Reference CaseyCasey (1974) demonstrated that the more one knows about law and courts, the more likely one is to believe in the theory of mechanical jurisprudence. Something about being exposed to information about courts contributes to people embracing this traditional mythology of judicial decisionmaking (see also Reference BrisbinBrisbin 1996; Reference Scheb and LyonsScheb & Lyons 2000).

This paradox is all the more interesting in cross-institutional perspective. Reference Hibbing and Theiss-MorseHibbing and Theiss-Morse (1995) have shown, for instance, that greater awareness of the Supreme Court leads to more support for it, whereas greater awareness of Congress is associated with less support for that institution. Reference Kritzer and VoelkerKritzer and Voelker (1998) offer similar evidence. When people are exposed to judicial institutions, they apparently learn more than a single lesson: They may understand that the court has made a decision in favor of (or opposed to) their interests, but they also learn something about the institution itself. Given the dense syndrome of legitimizing symbols courts employ, it is not surprising that this exposure enhances institutional legitimacy (see Reference Gibson, Lodge, Tabor and WoodsonGibson et al. 2010).

The Myth of Legality

But do Americans actually subscribe to a mythical view of judicial decisionmaking, and does this view contribute to judicial legitimacy?Footnote 12 The evidence is not entirely clear.

Reference Baird and GanglBaird and Gangl (2006) investigate this hypothesis, although their analysis is based on the judgments of college students. They posit that perceptions of legalistic decisionmaking enhance the perceived fairness of the decisionmaking process, a key underpinning of judicial legitimacy. In their experiment, they used media reports to try to convince the students that a Court decision was based more on political (legal realism) than legal (mechanical jurisprudence) considerations. Tellingly, the experiment failed on this score, with a majority of the students believing that the justices followed legalistic considerations even when told about the role of ideological factors (2006:602). Although this result limits the value of the experiment, the finding does demonstrate the powerful framing effects of the belief in legalistic decisionmaking and how deeply embedded it is among the political beliefs of many Americans. It should be noted that their analysis also demonstrates that greater belief in the myth of legality is associated with greater perceptions of fairness (see also Reference BairdBaird 2001).

Baird and Gangl also report an unexpected finding for which they have no explanation. Perceptions of legalistic decisionmaking enhance fairness judgments, but perceptions of political decisionmaking do not detract from fairness. Political decisionmaking is portrayed in their experiment by the belief that the “members of the Court engaged in bargaining and compromise to reach this decision.” Whether the students believed that bargaining was involved had no impact on perceived procedural fairness (2006:605).Footnote 13

We suspect that the reason for this finding lies in the Baird and Gangl conceptualization. They postulate a unidimensional continuum ranging from legalistic to political decisionmaking.Footnote 14 Legalistic refers to relying upon the law in making decisions; political decisionmaking involves bargaining and compromise. What Baird and Gangl seem not to appreciate, however, is that two forms of political decisionmaking exist: principled and strategic. Bargaining and compromise can be sincere and principled, and hence not necessarily objectionable; this process of decisionmaking can focus on real issues and generate legitimate ideological, philosophical, and legal disagreement. But bargaining and compromise can also be strategic, especially when the actors are attempting to maximize some form of their self-interest (e.g., political ambition) rather than reach a negotiated solution to the issue at hand (see Reference RamirezRamirez 2008). We hypothesize that, to the extent that the American people view discretionary and ideologically based decision-making as principled, those beliefs will not undermine the Supreme Court's legitimacy.

This then leads to the puzzle with which this article is concerned: Greater attention to courts is most likely associated with greater exposure to legitimizing symbols and therefore with enhanced judicial legitimacy. But greater exposure is also associated with a more realistic view of judicial decisionmaking, a view emphasizing discretion and policymaking, and that view may tend to undermine judicial legitimacy. Reconciling this paradox is important for developing a more thorough understanding of citizen beliefs about the judiciary.

Logically, then, these findings can be explained by only two processes. First, people must know little about the Court and therefore accept the myth of legality, which leads to the ascription of legitimacy. Or, second, knowing more about the Court must produce realistic understandings of judicial decisionmaking that do not undermine the legitimacy of courts. Thus, one of the most important questions this research seeks to answer is whether institutional support is undermined by holding a realistic understanding of the role of discretion and values-based decisionmaking when it comes to the Supreme Court. Our overriding hypothesis in this research is that so long as the exercise of discretion is perceived to be constrained by principles, the perception of discretion and policymaking is not a threat to judicial legitimacy.

The Survey

This research is based primarily on a nationally representative sample interviewed three times in 2005 and 2006. The initial interviews were conducted face-to-face from mid-May until mid-July 2005; the second-wave interviews were fielded from mid-January 2006 through mid-February 2006; and the final interviews were conducted a few months later, in May or June 2006. Additional details about the panel survey are available in the Appendix. None of the variables utilized in this analysis is drawn from the t3 interview.

Analysis

Measuring Institutional Legitimacy

Six items were used as the indicators of institutional loyaltyFootnote 15:

1 If the U.S. Supreme Court started making a lot of decisions that most people disagree with, it might be better to do away with the Supreme Court altogether. (75.6 percent supportive of the Court)

2 The right of the Supreme Court to decide certain types of controversial issues should be reduced. (49.7 percent supportive of the Court)

3 The Supreme Court can usually be trusted to make decisions that are right for the country as a whole. (70.7 percent supportive of the Court)

4 The U.S. Supreme Court gets too mixed up in politics. (35.9 percent supportive of the Court)

5 Judges on the U.S. Supreme Court who consistently make decisions at odds with what a majority of the people want should be removed from their position as judge. (54.9 percent supportive of the Court)

6 The U.S. Supreme Court has become too independent and should be seriously reined in. (59.2 percent supportive of the Court)

At the aggregate level, these items seem to indicate fairly high levels of support for the Court, a finding consistent with recent literature (e.g., Reference GibsonGibson 2007a).Footnote 16 The six-item pool has an alpha of 0.67, indicating a reasonable level of reliability.

Measuring Judicial Knowledge

Knowledge of the Court at t2 was measured by a set of three items. The items asked how Supreme Court justices are selected (appointed), their term (life), and which national institution has the “last say” in interpreting the Constitution (the Court). We created an index on the basis of the responses to these items; the index varies from 0 to 3. As we have noted elsewhere (Reference GibsonGibson & Caldeira 2009), these questions do not tax the American people: Fully 43.1 percent of the respondents answered all three questions correctly, and the average number of correct answers is 2.0 (median=2.0).Footnote 17

Replicating the Knowledge-Support Relationship

The correlation between knowledge and institutional support is 0.36, which is of course highly statistically significant (p<0.000) and substantial.Footnote 18 Those who know more about the Supreme Court are substantially more likely to express support for it. This finding confirms the conventional wisdom on the connection between knowledge and support and provides the beginning point for our analysis of the interrelationship between realism and institutional support.Footnote 19

Perceptions of Supreme Court Decisionmaking

How do the American people perceive decisionmaking on the Supreme Court? One possibility is that most Americans accept the theory of mechanical jurisprudence—as Reference PoundPound (1908) put it, the perception that judges have little discretion in decisionmaking; that law, not judicial philosophies, ideology, and partisanship, structures decisionmaking; and that courts are distinctively nonpolitical institutions.

We formulated several propositions about judicial decisionmaking and asked our respondents to indicate their degree of agreement or disagreement with each on a 5-point Likert response set. The first such statement has to do with discretion:

Since the Constitution must be updated to reflect society's values as they exist today, Supreme Court judges have a great deal of leeway in their decisions, even when they claim to be “interpreting” the Constitution.

To this statement, 65.1 percent agreed; thus, perceptions of available discretion in Supreme Court decisionmaking are widespread.Footnote 20

But on what basis do judges exercise their discretion? We offered three possibilities to the respondents:

Judges always say that their decisions are based on the law and the Constitution, but in many cases, judges are really basing their decisions on their own personal beliefs.

Judges' values and political views have little to do with how they decide cases before the Supreme Court.

Judges' party affiliations have little to do with how they decide cases before the Supreme Court.

Most Americans (57.3 percent) agree that judges actually base their decisions on their own personal beliefs, even while a smaller plurality (48.4 percent) recognizes that values and political views influence how decisions are made. On the question of partisan influences on decisionmaking, the balance of opinion changes, with a slim plurality believing that party affiliations have little to do with judges' decisions (43.9 versus 39.2 percent).Footnote 21

In general, belief in the theory of mechanical jurisprudence—indicated by disagreeing with the first two statements but accepting the second two—is not particularly widespread. Of the four propositions concerning the exercise of discretion, on average, only 1.4 of the items were endorsed by the respondents, with a median of only a single statement.Footnote 22 Only 1.9 percent of the sample subscribed to the theory of mechanical jurisprudence in response to all four of the propositions. Most Americans have a fairly realistic view of how Supreme Court justices make their decisions (54.9 percent endorse one or none of the mechanical jurisprudence positions). Thus, from the responses to these questions, it appears that most Americans reject the mechanical jurisprudence model: Most believe that judges have discretion and that judges make discretionary decisions on the basis of ideology and values, even if not strictly speaking on partisanship. These are beliefs we associate with legal realism.

Yet a majority of Americans—albeit a slim one (50.4 percent)—reject the view that “judges are just politicians in robes.”Footnote 23 The correlation between the four-item mechanical jurisprudence index and the belief that judges are politicians in robes is only 0.12. Thus, for many, discretionary and value-based decisionmaking is not synonymous with the politician's function. Instead, something more is required. Those who believe that judges are politicians are more likely to perceive discretionary decisionmaking, but those more likely to perceive discretionary decisionmaking are not necessarily more likely to view judges as politicians.

These findings suggest a typology based upon two factors: (1) whether judges are seen as having discretion in their decisionmaking, and (2) if so, whether the exercise of discretion is “political” or not. For the latter, we define “political” primarily in terms of whether discretion is exercised in a principled or self-serving or strategic fashion. We do so relying heavily on the work of Reference HibbingHibbing and Theiss-Morse (2001), who argue that disapproval of Congress is largely grounded in the perception that members of Congress are typically advancing their self-interest above all else. If people do not recognize discretion, the question of how discretion is exercised is not relevant; we term this position the Mechanical Jurisprudence Model. We dub the exercise of principled discretion the Judiciousness Model.Footnote 24 It recognizes the availability of discretion, but that discretion is exercised in a principled manner. The “Typical Politician Model” describes discretionary but self-interested decisionmaking. We posit that the dominant view of American judges is the Judiciousness Model and that the most prevalent view of parliamentarians and executives is the Typical Politician Model. Thus, we identify three main types when it comes to perceptions of the judiciary: Those who perceive relatively high discretion but believe that judges exercise discretion in a relatively principled fashion; those who see relatively high discretion but believe that judges tend toward being strategic politicians of the ordinary sort; and those who perceive relatively low discretion as available to judges.

Connecting Beliefs About the Process of Judging to Institutional Support

Table 1 reports the results of regressing institutional support on these various measures of perceptions and judicial knowledge.Footnote 25 Several interesting findings emerge from this table. First, Model I reveals that support is greatest among those who reject the view that judges' political views are irrelevant to their decisionmaking, and this is a fairly substantial (and of course highly significant) relationship (β=−0.28). In seeming contradiction, Model I also indicates that support is higher among those believing that no leeway in decisionmaking exists (β=0.12) and that judges do not base their decisions on their personal beliefs (β=0.16).

Table 1. The Impact of Perceptions of Decisionmaking Processes on Support for the U.S. Supreme Court

Note: Significance of standardized regression coefficients (β): ***p<0.001; **p<0.01; *p<0.05.

Model II clarifies these relationships considerably. Only two of the decisionmaking assessments are significantly related to institutional support: Support is highest among those disagreeing that political views are irrelevant (i.e., asserting that such views are relevant) and among those asserting that judges are not simply politicians in robes. The latter item reduces the impact of the two propositions connected to judicial insincerity to statistical insignificance, which seems to confirm the view that responses to these items are picking up the belief that judges are like “ordinary politicians” in describing their decisionmaking processes in insincere ways. The results in Model II support two basic but quite important conclusions: Support for the Court is not damaged by acceptance of the basic tenets of legal realism, but support depends upon seeing judges as different from ordinary politicians, in part because, unlike politicians, they are principled in their decisionmaking.

Finally, the addition of knowledge to this equation (Model III) changes the findings little, except to reiterate that knowledge itself has a substantial positive and direct impact on institutional support.Footnote 26

For only one of these perceptions is its impact conditional upon knowledge: As knowledge increases, the connection between the belief that judges are not merely politicians in robes and institutional support increases. Indeed, over the range of the knowledge indicator (0 through 3), the impact of the robes variable doubles, which is of course statistically significant (p=0.014).Footnote 27 Perhaps this is an indication that knowledgeable people understand better what it means not to be a politician in robes, and, consequently, that this understanding more readily translates into institutional support.

Connecting Political Knowledge to Beliefs About the Process of Judging

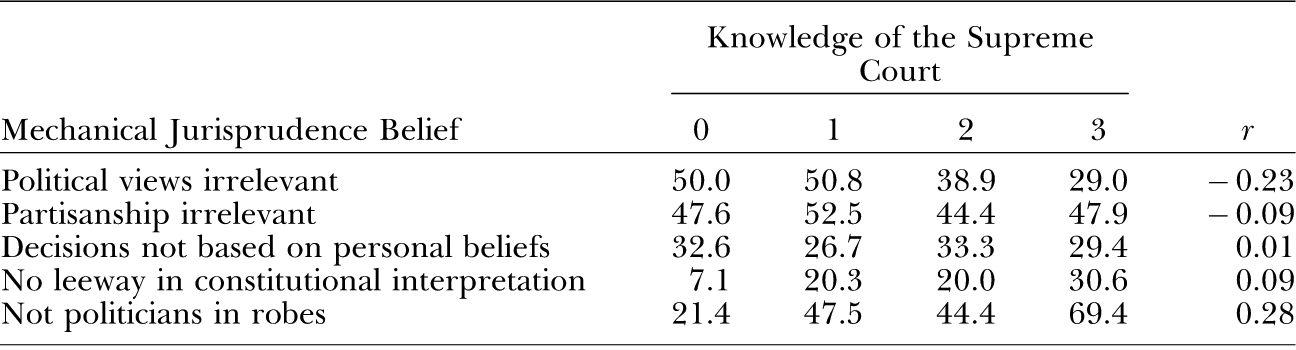

To what degree do these beliefs about judging reflect varying levels of knowledge about the operation of the Supreme Court? As we have noted, this is a crucial linkage in the institutional support model. Table 2 reports the relationships.

Table 2. The Relationship Between Court Knowledge and Belief in Mechanical Jurisprudence

Note: The table entries are the percentages of respondents at each level of court knowledge who endorse the mechanical jurisprudence viewpoint. Both knowledge and support for mechanical jurisprudence were measured at t2. 330≤N≤336.

The propositions (and the mechanical jurisprudence responses) are:

Judges' values and political views have little to do with how they decide cases before the Supreme Court. (Agree)

Judges' party affiliations have little to do with how they decide cases before the Supreme Court. (Agree)

Judges always say that their decisions are based on the law and the Constitution, but in many cases, judges are really basing their decisions on their own personal beliefs. (Disagree)

Since the constitution must be updated to reflect society's values as they exist today, Supreme Court judges have a great deal of leeway in their decisions, even when they claim to be “interpreting” the constitution. (Disagree)

Supreme Court judges are little more than politicians in robes. (Disagree)

The correlations in this table are all over the map. At one extreme, those who are more knowledgeable are less likely to assert that the political views of the justices are irrelevant, with only 29.0 percent of the most knowledgeable respondents subscribing to this viewpoint. This percentage contrasts with roughly one-half of those with low knowledge asserting that the political views of justices are irrelevant. On this item, knowledge is associated with rejection of the mechanical view of judging and acceptance of a realistic view of judicial decisionmaking.

At the other extreme, those most knowledgeable are most likely to reject the view that judges are merely politicians in robes. The contrast between the percentages is striking, with 69.4 percent of the most knowledgeable but only 21.4 percent of the least knowledgeable rejecting this statement. To the extent that the mechanical view asserts that what judges do is different from what ordinary politicians do, knowledge contributes to belief in the mechanical theory. However, the “politicians in robes” item may actually have a different meaning to these respondents.

For the other three items, the differences are less stark, and indeed, on the question of whether judges rely on their personal beliefs in decisionmaking, those at all knowledge levels accept that personal beliefs are important. The more knowledgeable are slightly less likely to believe that the partisan affiliations of judges are irrelevant (r=−0.09) and slightly more likely to accept the view that there is no leeway in constitutional interpretation (r=+0.09). These relationships are, however, quite weak. By noting the percentages in the column pertaining to the most knowledgeable respondents, one can readily see that the most knowledgeable respondents do not generally embrace the theory of mechanical jurisprudence.

Knowledgeable respondents seem to have fairly complicated views of judging. They do not believe that the political views of the judges are irrelevant, and only a minority denies discretion in judicial decisionmaking; at the same time, they see judging as different from ordinary politics. Perhaps the key to understanding their views can be found in the item on whether leeway in constitutional interpretation exists.

The leeway item was designed to measure perceptions of the availability of discretion in decisionmaking. But perhaps that is not what the question actually taps. Among the most knowledgeable, responses to this item are completely uncorrelated with the other statements (maximum r=0.05), with the exception of the statement about politicians in robes, with which the correlation is 0.22. We suspect that at least some respondents viewed this statement as more about judges being disingenuous than about discretion. It is possible that these respondents are keying on the phrase “even when they claim to be ‘interpreting’ the constitution.” Perhaps some view this as a statement about whether judges are strategic or not, in the sense of doing one thing but claiming to do another. The failure of this item to correlate with the other discretion questions while having a positive correlation with the politicians-in-robes item may indicate that this proposition is measuring perceptions of insincere activity on the part of judges. The data, however, do not allow further analysis of this possibility.

To recap: The most knowledgeable respondents recognize discretion and accept that judges rely on their political values in decisionmaking, even while seeing judges as different from ordinary politicians, especially in not being insincere and strategic. It appears that this conception of principled but discretionary judicial policymaking renders realistic views compatible with judicial legitimacy.

Discussion and Concluding Comments

The most certain and important conclusion of this analysis is that the legitimacy of the Supreme Court does not depend on the perception that judges merely “apply” the law in some sort of mechanical and discretionless process.Footnote 28 The American people know that the justices of the Supreme Court exercise discretion in making their decisions—what better evidence of this is there than the multiple and divided judgments by the group of nine? They are also aware that the justices' discretion is guided to at least some degree by ideological and even partisan considerations. None of these understandings seem to contribute to undermining the legitimacy of the Supreme Court. Instead, legitimacy seems to flow from the view that discretion is being exercised in a principled, rather than strategic, way.

These findings should not be taken to mean that the American people reject the rule of law (indeed, empirical evidence indicates that Americans are unusually strongly attached to the rule of law—see Reference GibsonGibson 2007b), nor that judicial legitimacy would be maintained were the Court to eschew the trappings of law. Indeed, it seems likely that a key source of the belief that judges engage in principled decisionmaking is the association of courts with symbols of fairness and legality (Reference Gibson, Lodge, Tabor and WoodsonGibson et al. 2010). Just as revisionist judicial scholars are today suggesting ways in which law is important to decisionmaking—thereby challenging the extreme variant of the attitudinal modelFootnote 29—we suspect the American people do not view law as irrelevant to judging, nor that judges engage in completely unconstrained policymaking. Of course, all of this is a matter of degree—to reject mechanical jurisprudence is not necessarily to assume unfettered discretion but only to recognize that, within the context of the rule of law, judges have choices in their decisions and that their choices often if not typically reflect their own ideological predispositions.

Our empirical evidence suggests that being informed about courts may mean that one understands that judges make decisions in a principled fashion; they are not merely politicians in robes. The mistake of some research might be to assume that principled decisionmaking can only be understood as discretionless or mechanical decisionmaking. The most important argument of this article is that the American people seem to accept that judicial decisionmaking can be discretionary and grounded in ideologies, but also principled and sincere. Judges differ from ordinary politicians in acting sincerely, and their sincerity adds tremendously to their legitimacy and the legitimacy of their institution.

So in the end, the generation of political scientists who have propounded legal realism and the attitudinal model seems to have done little to undermine the legitimacy of the Supreme Court. The American people seem quite capable of understanding the true nature of decisionmaking in the third branch but at the same time regard courts as highly legitimate within the American political scheme. Judges are certainly politicians—what distinguishes judges in the minds of the American people is that judges exercise discretion in a principled fashion. Were other politicians to act more like judges, perhaps the legitimacy of all American political institutions would be elevated.

Appendix: Survey Design, the 2005–2006 Panel Survey

This research is based on a nationally representative sample interviewed face-to-face during summer 2005. The fieldwork took place from mid-May until mid-July 2005. A total of 1,001 interviews were completed, with a response rate of 40.03 percent (American Association for Public Opinion Research [AAPOR] 2000: Response Rate #3). No respondent substitution was allowed; up to six callbacks were executed. The average length of the interview was 83.8 minutes (with a standard deviation of 23.9 minutes). The data were subjected to some minor “post-stratification,” with the proviso that the weighted numbers of cases must correspond to the actual number of completed interviews. Interviews were offered in both English and Spanish (with the Spanish version of the questionnaire prepared through conventional translation/back-translation procedures). This sample has a margin of error of approximately±3.08 percent.

During the course of Judge Alito's confirmation process, we attempted to re-interview by telephone the respondents from the 2005 survey.Footnote 30 The fieldwork began on January 19, 2006, and was completed on February 13, 2006. A total of 335 individuals from the 2005 survey were re-interviewed. If we were to treat this as an entirely new survey, not a re-interview, and apply the AAPOR criteria to calculate the widely used Modified Response Rate #3, the rate would have been 53.2 percent.

Because t2 interviews were completed with only one-third of the original respondents, questions about the representativeness of the subsample naturally arise. We have considered this issue in some detail.

One way in which the representativeness of the t2 sample can be assessed is to determine whether those who were interviewed in the second survey differ from those who were not interviewed. The null hypothesis (H0) is that no difference exists between the two subgroups.

We have investigated this hypothesis by examining the level of knowledge the respondents held about the Supreme Court. Table A1 reports the relevant statistical analysis. For instance, the first entry in the table reports that 72.8 percent of the t1 respondents who were interviewed at t2 knew that Supreme Court justices are appointed to the bench, whereas only 61.7 percent of those not interviewed were similarly informed. This difference is highly statistically significant (p<0.001), but the strength of the relationship is not very strong (phi=0.11). Overall, the t2 subsample is slightly more knowledgeable about the Supreme Court than those who were not interviewed. The differences are not great, nor are they entirely trivial. Consequently, some statistical adjustments to the t2 sample are necessary.

Table A1. Differences Between Those Interviewed and Those Not Interviewed in 2006

* Knowledge was measured during the 2005 interview. These data are weighted by t1 post-stratification weights.

The initial 2005 sample was subjected to minor post-stratification, adjusting the sample on a handful of demographic attributes (as is conventional these days). When we apply exactly the same methodology to the t2 data, using the frequency distributions for the demographic variables from the 2005 survey, the gap between interviewed and not-interviewed decreases considerably. For instance, without t2 weighting, the mean number of correct answers to the three knowledge questions among the interviewees is 2.03. With weighting, that mean falls to 1.87, which is much closer to the mean of 1.72 for those who were not interviewed. Consequently, we have weighted the t2 data by this factor, and, after doing so, the t2 sub-sample is reasonably representative of the initial sample.

Thus, we draw two general conclusions from that analysis. First, the t2 subsample is reasonably representative on its face, and second, with minor post-stratification, the 2006 sub-sample closely mirrors the 2005 population from which it was drawn. We therefore believe inferences can confidently be drawn from our analysis, even if the confidence intervals of this relatively small subsample are larger than we might prefer.

A t3 survey was conducted with these respondents, but none of the data in this article were drawn from that interview.