1. Introduction

The Scandinavian languages are closely related and often very similar. At the same time, they are well known to exhibit relatively large variation within the nominal phrase, particularly with respect to definiteness marking. This variation has received much attention in the field of Scandinavian syntax (Taraldsen Reference Taraldsen, Mascaró and Nespor1990; Delsing Reference Delsing1993, Reference Delsing, Vangsnes, Holmberg and Delsing2003; Kester Reference Kester1993, Reference Kester1996; Santelmann Reference Santelmann1993; Vangsnes Reference Vangsnes1999; Julien Reference Julien2002, Reference Julien2005; Anderssen Reference Anderssen2006, Reference Anderssen2012, inter alia). The present article investigates variation found within Norwegian modified definite phrases.

The basic facts about Norwegian definiteness marking are as follows. Definite nouns occur with a definite suffixed article, illustrated in (1a),Footnote 1 as in all Scandinavian languages.Footnote 2 When the phrase is modified by an adjective or a numeral, Norwegian displays double definiteness, also called compositional definiteness (CD) (Anderssen Reference Anderssen2012): the suffixed article is accompanied by a prenominal determiner, as in (1b).

Across the Scandinavian languages, there is much variation in modified definite phrases like the one in (1b). While Norwegian, Swedish, and Faroese show double definiteness, there is single definiteness in the other varieties. Icelandic and the Northern Swedish vernaculars lack the prenominal determiner and only use definite suffixes. Danish uses the prenominal determiner in modified phrases, but it does not co-occur with the suffixed article, which is restricted to unmodified phrases (see Julien Reference Julien2002:264 for an overview).

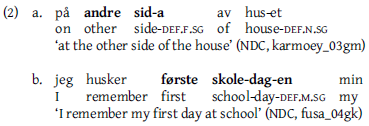

In addition to this variation across languages, there is also variation within the double definiteness languages with respect to the use of the prenominal determiner. In Norwegian, one can find examples without the prenominal determiner, as in the utterances in (2), from the Nordic Dialect Corpus (NDC) (Johannessen et al. Reference Johannessen, Joel Priestley, Åfarli and Vangsnes2009).

These examples are acceptable for most native speakers of Norwegian, and not at all infrequent, as is shown below. They indicate that although double definiteness is generally obligatory, there are cases where the prenominal determiner may be left out. This article examines the exceptions to double definiteness like the ones in (2). While the existence of these exceptions has been noted before (see Section 2), there has, to my knowledge, not been a systematic study of the use of modified definite phrases without a determiner in Norwegian. In the present article, I describe the use of the exceptions, and furthermore provide a syntactic analysis for them. By investigating variation within the language, this article contributes to the description of Scandinavian nominal phrases and to an understanding of the patterns of variation in these languages.

The article is structured as follows. In Section 2, different descriptions of double definiteness and its exceptions are discussed, followed by the questions for the present study. Section 3 briefly presents the empirical basis, which consists of both corpus data and acceptability judgments. The phenomenon of determiner omission is presented in Section 4, where three types of adjectives are identified: exceptional adjectives (4.1), quantifier adjectives (4.2), and regular adjectives (4.3). Section 5 presents my syntactic analysis of the exceptional adjectives, in which the syntactic projection containing the adjective and the definite noun moves to Spec-DP. Section 6 briefly touches upon different types of variation found in the data, including dialectal and historical variation. Finally, Section 7 provides a conclusion to the study.

2. Background: Double definiteness and its exceptions

Double definiteness is a well-known property of Norwegian, Swedish, and Faroese. This article focuses on Norwegian. Although it is generally obligatory in Norwegian to combine the prenominal determiner and suffixed article in modified definite phrases, there are also exceptions. In some contexts, only one of the definiteness markers is present.

Some Norwegian dialects are known to exhibit a phenomenon referred to as adjective incorporation, in which the adjective is incorporated in (or compounded with) the definite noun. In these phrases, there is no prenominal determiner, as in (3a). For comparison, the version with double definiteness is given in (3b).

Adjective incorporation (3a) is especially common in the dialects in the Trøndelag region of Norway (Faarlund et al. Reference Faarlund, Lie and Ivar Vannebo1997:75), and in Northern Swedish dialects (see, e.g., Sandström & Holmberg Reference Sandström and Holmberg1994; Dahl Reference Dahl2015). Typically, the adjectival inflection is lacking in these constructions (compare ny in (3a) with ny-e in (3b)), and the adjective and noun form one prosodic unit. In the present study, adjective incorporation is not discussed further. Instead, the focus is on cases where the prenominal determiner can be omitted without other processes (such as compounding) coming into play.

Before we turn to cases where the prenominal determiner is lacking, however, it should be pointed out that there are also examples of modified definite phrases without the suffixed article. An example is Det hvite hus ‘the White House’, a fixed name-like expression to refer to the American White House and not to any white house that is definite by context or discourse. A list of contexts where suffix omission is common is provided in the Norwegian Reference Grammar (Faarlund et al. Reference Faarlund, Lie and Ivar Vannebo1997:297-298, 307-313). The list includes name-like phrases and phrases without deictic or anaphoric reference. Furthermore, the omission of the suffix is more typical in the Bokmål standard, which is historically closer to Danish, than in the Nynorsk standard that would more frequently show double definiteness.

The present article focuses on another type of exceptions, namely, those in which the prenominal determiner is omitted, as in the examples in (2) above. There seem to be two types of determiner omission: situations in which the determiner is always absent, and situations in which the determiner may be absent but may also be included.

There are three contexts where the determiner is always absent, as discussed by Faarlund et al. (Reference Faarlund, Lie and Ivar Vannebo1997:301-302). First, the adjectives hele ‘whole’ and halve ‘half’ are combined with a definite noun, but not with a prenominal determiner; see (4a). Faarlund et al. (Reference Faarlund, Lie and Ivar Vannebo1997:218) point out that the adjectives in these phrases function like quantifiers. In this function, they precede demonstratives, as in (4b). I come back to the quantifier-like adjectives in Section 4.2.

A second context in which the prenominal determiner is absent is when the adjective has an “expressive meaning.” In this case, the nominal phrase does not have an anaphoric or deictic reference, but rather focuses on the descriptive content of the adjective. An example is given in (5a), where the phrase does not refer to a given black night, but rather expresses that the night is black (see also Julien Reference Julien2002:280). Finally, the prenominal determiner is absent in certain predicative constructions with, again, an expressive function (5b). Here, the nominal phrase does not refer to an element in the real world but expresses a characteristic of the subject.Footnote 3 Halmøy (Reference Halmøy2016:293-294) points out that the adjective does not convey new information in these cases, but rather reinforces the properties of the noun.

The two contexts in (5) could be taken to be non-referential nominal phrases. Julien (2002:279, Reference Julien2005:32) points out that the determiner is absent from all non-referential nominal phrases, including vocatives. Furthermore, phrases that are inherently referential because they include a personal name also lack the determiner (e.g., vesle Anna ‘little Anna’).

The cases discussed above are cases in which the prenominal determiner is always omitted. In addition, there are contexts in which the determiner is not obligatory: it may be omitted but it may also be present. Descriptions of these contexts are much less clear. Faarlund et al. (Reference Faarlund, Lie and Ivar Vannebo1997:312-313) mention a set of adjectives which may be preceded by the determiner when they are part of a definite phrase. However, the status of the determiner in these phrases, and factors that govern its absence, are not discussed in more detail. The relevant adjectives express “en lokalisering eller en ordning”Footnote 4 and the adjectives are often ordinal numbers or adjectives in comparative or superlative form (Faarlund et al. Reference Faarlund, Lie and Ivar Vannebo1997:312-313). The adjectives listed in (6) are mentioned as examples of this class of adjectives.

These adjectives and others similar to this group are also mentioned in other descriptions of the Scandinavian or Norwegian noun phrase as adjectives that do not require a prenominal determiner (Delsing Reference Delsing1993:118-120; Vangsnes Reference Vangsnes1999:135; Julien 2002:282; Reference Julien2005:33, 37; Anderssen Reference Anderssen2006:132; Halmøy Reference Halmøy2016:289; Anderssen et al. Reference Anderssen, Lundquist and Westergaard2018:750). As pointed out by Delsing (Reference Delsing1993:118), these adjectives all make the nominal phrase “unambiguous in the speech situation,” and they consequently make the nominal phrase uniquely identifiable. Other descriptions build on this analysis of the relevant adjectives: Dahl (Reference Dahl2015:125) points out that the adjectives that are optionally combined with a determiner in Swedish express a uniqueness feature. The list of adjectives that Dahl (Reference Dahl2015) provides is very similar to the one in (6), and Teleman et al. (Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999a) include the same adjectives in their discussion of omission of the prenominal determiner. Similarly, in Faroese, the prenominal determiner may be left out in non-referential phrases, in name-like expressions, and after a specific set of adjectives (Harries Reference Harries2015:166, 174; Börjars et al. Reference Börjars, Harries and Vincent2016:e23). Some examples from Swedish and Faroese are given in (7) and (8), respectively.

While exceptions are discussed by different sources, these descriptions tend to be somewhat vague. Delsing (Reference Delsing1993:120), for example, states that “the prenominal article is often optional (especially in Swedish and Faroese)” in phrases with the “special” adjectives. Similarly, Julien (Reference Julien2005:37) points out that the determiner may be omitted in front of superlatives in Swedish and then adds: “The tendency is also found in some Norwegian dialects, by the way.” Statements like these suggest that the optionality of determiners in Norwegian is unclear. The descriptions discussed above indicate that there are exceptions to modified definite phrases in which the determiner may be omitted, but the vague descriptions raise several questions. It is unclear whether all the mentioned adjectives are actual exceptions to double definiteness, and how frequently they occur without the determiner. Another question relates to the amount of variation within Norwegian with respect to omission (or inclusion) of the determiner. Finally, the descriptions so far do not provide a syntactic analysis of the phrases without the determiner. The goal of this article is to answer these questions. The description of the exceptions is discussed in Section 4, and the proposed syntactic analysis in Section 5. The discussion above indicates that Swedish and Faroese also have exceptions to double definiteness, but the remainder of the article focuses on Norwegian.

3. The empirical basis: corpus data and acceptability judgments

In the literature discussed above, several adjectives that can or should occur without the prenominal determiner have been mentioned. The present study investigates these adjectives and their occurrence with and without the prenominal determiner in a large corpus of spoken Norwegian and by means of acceptability judgments. These methods are discussed here; the findings are presented in Section 4.

I used the Nordic Dialect Corpus (NDC) (Johannessen et al. Reference Johannessen, Joel Priestley, Åfarli and Vangsnes2009) to investigate the variation in Norwegian modified definite phrases. The corpus contains recordings of spoken, dialectal language from the five Scandinavian countries (Denmark, Faroe Islands, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden); only the Norwegian dialects were included in the study. The NDC contains speech data from many different locations, and from both older and younger speakers in each location. As such, it is a valuable resource for the analysis of variation in spoken Norwegian.

The study is based on version 4 of the NDC, which contains recordings of 438 speakers from 111 locations across Norway, and almost 2 million tokens. Previously, the NDC also included recordings of dialects from an older Norwegian dialect archive (Målførearkivet); these have been moved to the Language Infrastructure made Accessible (LIA-Norwegian) corpus.Footnote 5 They are discussed briefly in Section 6.1 on historical variation; the results in Section 4 are based exclusively on present-day Norwegian.

Several separate search queries were conducted using the corpus. Each query searched for an adjective followed directly by a definite noun. This means that the results do not include cases in which another word or a hesitation appeared between the adjective and the noun. Based on the literature discussed above, the adjectives listed in (9) were included in the searches.

Note that the literature cited in Section 2 treats the adjectives in (9a–g) differently from hele ‘whole’ and halve ‘half’ (9h). With the latter, the prenominal determiner is expected not to occur at all. In addition to the searches for specific adjectives, a search for any adjective followed by a definite noun was also conducted. The results from this search (excluding the adjectives in (9) that were identified as exceptions) were used to confirm that double definiteness is generally obligatory in Norwegian. As shown in Section 4.3, this is indeed the case.

The results of each corpus search were checked manually to exclude tagging errors, instances where the element right before the adjective was transcribed as “uninterpretable,” and phrases with a place name or a proper name. The latter are well known to behave differently with respect to definiteness marking (see above), since the name makes the phrase inherently referential.

The remaining results were categorized as to whether they contained a prenominal determiner in front of the adjective, or not. The results also contain a small number of phrases with a demonstrative (10a) or a personal pronoun (10b) instead of a determiner. Phrases like these are quite infrequent.Footnote 6 In these phrases, the demonstrative or pronoun may be analyzed as an alternative to the prenominal determiner, but this has not been studied systematically yet. They were therefore excluded from the results presented here that only discuss the presence or absence of the prenominal determiner.

In addition to the corpus searches, some acceptability judgments were elicited from a group of native and naïve speakers of Norwegian. These speakers completed a judgment task consisting of 60 sentences in total. The task included 8 sentences with an adjective that requires double definiteness, and 4 sentences with such an adjective but without the prenominal determiner. In addition, the task included 4 sentences with an adjective that has been described as an exception, half of them preceded by a prenominal determiner and half without the determiner. The adjectives used were a superlative and andre ‘other, second’. See (11) for examples of sentences from the judgment task.

The judgment task was administered as a pen-and-paper task (n of participants = 7, age 21–66), or orally (n = 7, age 75–83). The participants were living in Oslo, or in places relatively close to Oslo (Eidsvoll, Hamar).Footnote 7 Participants in the oral judgment task were asked to repeat the sentences they heard, and then judge them. In both modalities, a three-point judgment scale was used (acceptable—marginal—unacceptable).

4. Description of determiner omission in Norwegian

The results of the corpus study and judgment task are presented in this section. In the results, three groups of adjectives can be distinguished; they are discussed separately below. Section 4.1 presents the results of the adjectives that are exceptions to double definiteness. Section 4.2 discusses the items hele ‘whole’ and halve ‘half’ that can be characterized as quantifier adjectives. Section 4.3 discusses the results for the remaining adjectives, confirming that double definiteness is obligatory in Norwegian for adjectives other than the identified exceptions.

4.1 The exceptional adjectives

The searches in the NDC yielded a total of 1,537 definite phrases with one of the adjectives that has been listed in the literature as an exception (i.e., the adjectives in (9a–g)). In this section, I discuss the results of the NDC as a whole; they are broken down by region in Section 6.2 on dialectal variation, where it becomes clear that the dialectal variation is relatively small. A prenominal determiner was present in 46.52% (n = 715) of these phrases, while 53.48% (n=822) occurred without a determiner. In other words, a small majority of the phrases with these adjectives lack the prenominal determiner. Those adjectives clearly do not require double definiteness, and as such are exceptions. I refer to them as “exceptional adjectives” in the remainder of the article.

While the results show that double definiteness is not obligatory with these adjectives, they may still be preceded by a prenominal determiner. There are differences between the adjectives with respect to how frequently they are combined with a determiner, as can be seen in Table 1. The searches did not yield any definite phrases with the adjectives øvre ‘upper’ or nedre ‘lower’. The (larger) LIA corpus with older dialect recordings contains examples with these adjectives (see Section 6.1), and results indicate that these adjectives are optionally combined with a determiner.

Table 1. Adjectives that do not require a prenominal determiner in definite phrases, Nordic Dialect Corpus. Numbers presented in parentheses

The adjectives in Table 1 are presented in descending order based on the percentage of determiner inclusion. As can be seen, there is considerable variation between the different adjectives. While superlatives are combined with determiners in the (vast) majority of the cases, the picture for ordinal numbers is completely the opposite. For most of the adjectives, it seems somewhat preferred to omit the determiner. The few results with the adjectives venstre ‘left’ and høyre ‘right’ all lacked the determiner, which may seem to suggest that these adjectives cannot combine with a determiner. However, this conclusion is too strong: all native speakers I consulted state that these adjectives can be preceded by a determiner (see also Julien Reference Julien2005:33).

To illustrate the use of the exceptional adjectives, examples are provided below. For each adjective, one example with and one example without the determiner are presented. In most cases, the topic and pragmatic context are very similar. In (12), for example, both speakers discuss the best place to live, and one phrase lacks the determiner while the other one contains it. Something similar can be seen in the examples in (13) that were both uttered while discussing the most recent soccer match. Again, one phrase includes the determiner and the other one does not. Note that all examples below are independent of each other: they are produced by speakers from different locations, in different conversations.Footnote 9, Footnote 10

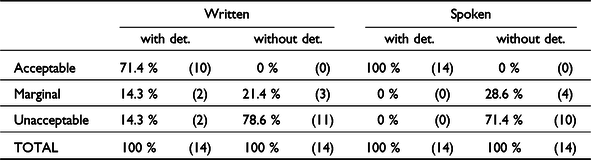

From the corpus data, it can be concluded that the prenominal determiner is optional in modified definite phrases if the adjective belongs to the class of exceptional adjectives. The same conclusion can be drawn from the acceptability judgment data. Table 2 presents the judgment data from both the written and spoken tasks.

Table 2. Acceptability judgments of modified definite phrases with an exceptional adjective, with and without determiner

The results in Table 2 clearly show that the determiner can be present with these adjectives, as virtually all phrases with a determiner were judged to be acceptable.Footnote 11 The phrases in which the exceptional adjective was not preceded by a determiner were accepted to a lesser extent, 50% in the written group and 71.4% in the spoken groups. These scores are nevertheless still high and indicate that omission of the determiner with exceptional adjectives is possible in Norwegian.

The judgment data show two interesting patterns of variation. First, the acceptability of determiner omission varies depending on the adjective used. All speakers in both groups judged the sentence with andre ‘other’ acceptable when the determiner was absent, while sentences with a superlative (største ‘largest’) were judged marginal or unacceptable when presented in written form. In the spoken task, some speakers accepted determiner omission with the superlative, but not everyone did. A similar pattern was found in the corpus data (Table 1), where superlatives were most frequently combined with a determiner, whereas andre and other adjectives were found more often without a determiner.

Second, the data show variation between the judgments on written and those on spoken sentences. Although both groups accept exceptional adjectives with a determiner (as expected), the judgments on determiner omission are stricter in the written than in the spoken modality. Phrases without the determiner were accepted more by the latter, which suggests that exceptional adjectives without a determiner are more readily accepted in spoken than in written (standardized) language.Footnote 12

Moving away from these types of variation, the corpus data as well as the judgment data indicate that the prenominal determiner may be omitted from modified definite phrases when the adjective belongs to a restricted set of exceptional adjectives. This is consistent with the observations in previous literature presented in Section 2.

4.2 Phrases with hele ‘whole’ and halve ‘half’

As discussed in Section 2 above, it has been noted that hele ‘whole’ is never preceded by a prenominal determiner (e.g., Faarlund et al. Reference Faarlund, Lie and Ivar Vannebo1997:301; Anderssen et al. Reference Anderssen, Lundquist and Westergaard2018:750). This is confirmed by the corpus data from the NDC: no single example of a modified definite phrase with hele and a determiner was found. The search query yielded 684 phrases with hele followed by a definite noun, and all of them (100%) lacked a prenominal determiner. Some examples are given in (17).

Compared to the adjectives discussed in Section 4.1, hele ‘whole’ behaves differently: while the former may occur without the determiner, the latter must occur without a determiner. In fact, in cases where a determiner is present within the phrase, hele ‘whole’ occurs in front of this determiner, as in the following examples.

The fact that hele occurs before the prenominal determiner suggests that it may not be an adjective in these phrases. Rather, it could be analyzed as a strong quantifier (similar to alle ‘all’), as noted by Faarlund et al. (Reference Faarlund, Lie and Ivar Vannebo1997:218). Strong quantifiers are located in a separate functional projection on top of the DP (see Section 5), and not in the same projection as adjectives.

A similar analysis could be made for halve ‘half’. This word can also operate as a quantifier in definite phrases, and is then not preceded by the prenominal determiner. Unfortunately, halve is not very frequent in the NDC and only 34 phrases were found. Of these, 31 (91.2%) do not contain a determiner. An example is given in (19). The remaining three phrases contain a prenominal determiner, as in (20).

It is important to note a subtle semantic difference between these two examples (which can also be seen in the English translations). The first example does not refer to a specific half book; rather, it refers to a certain proportion or quantity of the book (viz. half of it). The second example, on the other hand, refers to a specific half hour, namely, the half hour that the participants were instructed to speak during the recording for the corpus. In other words, halve ‘half’ functions as a quantifier in (19) and thus does not co-occur with the determiner, but it is a regular adjective in (20) and is then preceded by the determiner (see Halmøy Reference Halmøy2016:291-293 for a similar observation).

Based on the data presented in this section, I argue that the words hele and halve in modified definite phrases are strong quantifiers rather than adjectives (in line with Faarlund et al. Reference Faarlund, Lie and Ivar Vannebo1997). Therefore, they cannot co-occur with a prenominal determiner. Both words can function as adjectives in indefinite phrases, as in (21), where the adjectives are inflected for gender to agree with the noun. Example (20) illustrates that halve can also occur as an adjective in definite phrases.

4.3 Regular modified definite phrases

In the previous sections, I have argued that a set of adjectives can occur without the prenominal determiner in definite phrases, and that two adjectives (hele ‘whole’ and halve ‘half’) function as strong quantifiers. However, the claim that the adjectives in Section 4.1 are exceptions depends on the assumption that other adjectives obligatorily occur with double definiteness. In this section, I therefore double-check that the non-exceptional adjectives are preceded by the prenominal determiner in Norwegian.

This investigation is even more important given that Julien (Reference Julien2005:32–33) claims that the prenominal determiner may be omitted in Norwegian when the discourse referent is strongly familiar, as in (22). However, Julien also notes that not all speakers accept determiner omission in these instances, and several native speakers I consulted judged this sentence unacceptable. In Swedish, phrases like (22) are used quite frequently.Footnote 13

As mentioned in Section 3, I conducted a search in the NDC for adjectives directly followed by a definite noun. All adjectives that were already established as exceptions are excluded from the results presented here. Phrases that directly followed the negation ikke ‘not’ were also excluded, as phrases within negative polarity items always lack the determiner and typically have an indefinite interpretation (Julien Reference Julien2011). Other non-referential phrases were also excluded.

In total, this corpus search yielded 636 modified definite phrases with a regular adjective.Footnote 14 Of these, the vast majority contain the prenominal determiner (94.03%, n = 598), see (23), and a small number occur without the determiner (5.97%, n = 38); see (24).

Out of the 38 phrases without a determiner, 26 (68.4%) could potentially be explained by the pragmatics of the utterance. In these cases, the referent of the phrase is present in the discourse or highly familiar to the speakers. The utterance in (24a) is an example of this: the speaker was just asked “will you watch the Eurovision (Song Contest) finale?” and the speaker responds by asking whether the mentioned finale is the Norwegian or international one. Thus, he refers back to something that is active in the discourse, and this is exactly the context Julien (Reference Julien2005:32, see above) refers to as a situation for determiner omission. As noted, this is not acceptable for all speakers and only occurs a few times in the corpus. To the best of my knowledge, there have been no studies on the effect of pragmatic conditions on double definiteness in Norwegian.Footnote 15 If one assumes that highly active entities may be referred to without a determiner by some speakers, only 12 (1.9%) of the modified definite phrases with a regular adjective lack the determiner (e.g., (24b)). Given this low percentage, it seems reasonable to conclude that these adjectives are obligatorily preceded by a determiner.Footnote 16 Even if a pragmatic explanation is not adopted, the number of phrases without a determiner is still low. Furthermore, native-speaker judgments indicate that the determiner cannot be omitted before regular adjectives.

In the acceptability judgment task, native speakers of Norwegian clearly judged modified definite phrases without the determiner as unacceptable when the adjective was not an exceptional adjective. Recall from Section 3 that each participant judged 8 sentences with double definiteness and 4 sentences without the determiner. The results of the judgment task are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Acceptability judgments of modified definite phrases with a regular adjective, with and without determiner

The data in Table 3 clearly show a difference between the phrases with double definiteness and phrases without a determiner. The former are all judged acceptable by native speakers. The latter, however, are generally judged marginal or unacceptable, and the written group rejects these (almost) categorically. In the oral task, there is some variation between speakers with respect to how strongly they reject the phrases without a determiner. Some speakers rate these phrases as unacceptable, while others rate them as marginal. The tendency for judgments in the written modality to be stronger than in the spoken modality was also found with exceptional adjectives (see Table 2 in Section 4.1). The acceptance rate of phrases without the determiner might be higher if the right pragmatic conditions were provided. As pointed out above, however, it is currently unclear what the exact pragmatic context should be and whether all speakers would then accept determiner omission. In isolated sentences, both groups of speakers allow only double definiteness – and not determiner omission – when the phrase is modified by a regular adjective.

Together, the corpus data and judgment data show that although determiner omission is possible with some adjectives (Section 4.1), it is also restricted to these adjectives. All other adjectives generally require double definiteness, i.e., the co-occurrence of the prenominal determiner and the definite suffix. I refer to these adjectives as “regular” adjectives, contrasting with the exceptional adjectives discussed in Section 4.1.

4.4 Summary

In the previous sections, three types of adjectives have been discussed, which all show different behavior in definite phrases. First, there are the regular adjectives that require double definiteness (Section 4.3). These adjectives are obligatorily preceded by a prenominal determiner when they combine with a definite noun. Possibly, some speakers allow this determiner to be omitted in certain pragmatic contexts, but the exact conditions for this—and how widespread this phenomenon is in Norwegian—remains a matter for future research.

As a second type, there are exceptional adjectives (Section 4.1) that do not always combine with a prenominal determiner in definite phrases. These adjectives occur both with and without the determiner, and variation is found with respect to how frequently individual adjectives are preceded by a determiner. The group of exceptional adjectives consists of superlatives, ordinal numbers, and the words første ‘first’, siste ‘last’, eneste ‘only’, andre ‘other, second’, venstre ‘left’, høyre ‘right’, neste ‘next’, and forrige ‘previous’. Potentially, there are a few more adjectives belonging to this group, as øvre ‘upper’ and nedre ‘lower’ did not provide any results in the corpus query (but see Section 6.1). Faarlund et al. (Reference Faarlund, Lie and Ivar Vannebo1997:312) mention ytre ‘outer’ as an exception, and Svenonius (Reference Svenonius, Duncan, Farkas and Spaelti1994:447) mentions samme ‘same’. Future studies can establish whether these are indeed exceptions.

Finally, the third type of adjectives is the quantifier adjectives hele ‘whole’ and halve ‘half’ (Section 4.2). These can function as adjectives modifying the noun, but in definite phrases they typically function as quantifiers and then they are never preceded by a determiner. In fact, if a determiner or demonstrative occurs in the phrase, it appears after the quantifier adjective. The quantifier adjectives are different from the exceptional adjectives because they never appear with a determiner, while the latter optionally appear with a determiner.

5. The syntax of determiner omission

In the previous section, it was shown that Norwegian has a restricted set of adjectives that are an exception to double definiteness. This section discusses the syntax of determiner omission with these exceptional adjectives.

In this section, I follow Julien’s (2002, 2005) analysis of the Scandinavian nominal phrase. This DP structure is given in (25) in a somewhat simplified form. From bottom to top, the structure contains the noun (N), a projection for number features (Num), a projection where the definite suffix is located (Art), a projection with adjectival phrases in the specifier (αP), a projection with weak quantifiers such as numerals in the specifier (CardP) and, on top, the DP where the prenominal determiners are located. The projections αP and CardP are only present when the phrase contains an adjective or numeral, respectively, while the other projections are assumed to be present in every referential nominal phrase. On top of DP, Julien (Reference Julien2002, Reference Julien2005) assumes two more projections: DemP for demonstratives, and QP for strong quantifiers. This is illustrated in (26).

The Scandinavian DP (Julien Reference Julien2005:11)Footnote 17

A central assumption in Julien (Reference Julien2002, Reference Julien2005) is that the D-projection must be made “visible” when the referentiality of the phrase depends on D. This is the case for all phrases that are referential and act as an argument in the sentence. “Visible” in this analysis means that there is phonological material in either D or its specifier. A similar assumption is made by Delsing (Reference Delsing1993:65).

In all Scandinavian languages, N forms a complex head with Num and Art in definite phrases. In unmodified phrases, ArtP then moves to Spec-DP to make the D-projection visible and enable the phrase to be referential (see Julien Reference Julien2002:272, 276 for details). However, when an adjective or a numeral (in respectively αP or CardP) is present, this movement is blocked, and a prenominal determiner is inserted in D in the languages that show double definiteness. This accounts for Norwegian phrases like den hvite hesten ‘the white horse’. However, this analysis does not account for phrases with exceptional adjectives such as første året ‘the first year’ that were discussed in Section 4.1.

Icelandic and the Northern Swedish vernaculars have modified definite phrases that are, at least on the surface, similar to the exceptions in Norwegian. The syntax of these languages is discussed in Section 5.1 below. In Section 5.2, I propose that the analysis of Icelandic and Northern Swedish can be extended to phrases with exceptional adjectives in Norwegian. This proposal leads to two predictions, which are tested in Sections 5.3 and 5.4.

5.1 Icelandic and Northern Swedish dialects

There are two Scandinavian varieties that do not use prenominal determiners: Icelandic and the Northern Swedish vernaculars. Modified definite phrases in these languages only contain the suffixed article, as illustrated in (27)–(28). On the surface, they resemble the phrases with exceptional adjectives in Norwegian, and I argue in the next sections that they are also similar syntactically.

In modified definite phrases that include a cardinal number, Icelandic shows an interesting word order: cardinal numbers appear at the end of the phrase, as in (29). Julien (Reference Julien2005) therefore argues that αP, which includes the adjective and the definite noun, moves to Spec-DP in Icelandic. In other words, αP moves across CardP, and cardinal numbers appear at the end of the surface structure. Vangsnes (Reference Vangsnes1999:146-147) provides a similar analysis.Footnote 19

Julien (Reference Julien2002, Reference Julien2005) relates the movement of αP to Spec-DP in Icelandic to the fact that Icelandic has case marking. In my view, this is not a necessary requirement, as Northern Swedish allows for the same movement but does not have case marking. The example in (29) shows that αP can move across CardP in Icelandic. There is, however, one context in which αP cannot move to Spec-DP: When there is ellipsis of the noun, αP cannot move to Spec-DP and D is spelled out instead, as in (30).

Julien (2002:277, Reference Julien2005:29) argues that only elements with a referential index can move to the D-projection. Nouns have such a referential index, but adjectives do not. As a result, αP can only move if it contains an overt noun.

Northern Swedish is the other Scandinavian variety without prenominal determiners in modified definite phrases (see (28) above). Julien (Reference Julien2002, Reference Julien2005) argues that Northern Swedish exhibits the same movement of αP to Spec-DP as Icelandic. The same requirement that αP must contain an overt noun is active in Northern Swedish. In cases of noun ellipsis, as in (31), the adjective carries a definite suffix. This suffix can be analyzed as the realization of D (Julien Reference Julien2005:63), which indicates that D must be visible when αP does not contain a noun and cannot move to Spec-DP.

When it comes to phrases with a cardinal number, Northern Swedish is unlike Icelandic: αP cannot move across CardP in Northern Swedish and cardinal numbers precede the adjective and the noun, as in (32) (cf. (29)). The presence of CardP blocks movement of αP to Spec-DP, and the D-projection must be made visible in another way. This happens through the insertion of a (complex) demonstrative, since Northern Swedish does not have prenominal determiners.Footnote 20

To summarize, Icelandic and the Northern Swedish dialects do not have double definiteness. Instead, the requirement to make the DP-layer visible is fulfilled by movement of αP (containing the adjective and definite noun) to Spec-DP. The syntactic structure of such phrases is illustrated in (33) below. There are some restrictions on αP-to-Spec-DP movement: the noun has to be overt (in both languages), and there cannot be a cardinal number between αP and DP (in Northern Swedish).Footnote 21

5.2 Proposal for Norwegian

Although several scholars have listed adjectives which do not need to be preceded by a determiner in definite phrases, it often remains unclear what the syntax of these exceptions is (see Section 2 above). In this section, I propose that the analysis of Icelandic and Northern Swedish (αP-to-Spec-DP movement) can account for the Norwegian exceptions to double definiteness. To the best of my knowledge, this has not been proposed before. On the contrary, Julien (Reference Julien2002:281) suggests that “there is no D that is associated with overt material” in Norwegian phrases without a determiner. Considering the proposals for Icelandic and Northern Swedish, however, it seems more appealing to analyze the Norwegian exceptions along the same lines. Otherwise, it would have to be explained why Norwegian (and potentially Swedish and Faroese; see Section 2) sometimes allows for an empty D in referential phrases that function as arguments. Furthermore, there are restrictions to αP-to-Spec-DP movement, and the hypothesis thus provides testable predictions (see below). It is therefore a stronger hypothesis than the suggestion that D is simply empty.

In fact, Julien (Reference Julien2016:80) suggests that “[i]t is even possible that the adjective can move to D if nothing intervenes” in the cases with exceptional adjectives. However, I propose that it is the whole αP rather than the adjective only that moves to the D-projection. Again, this is in line with the other Scandinavian varieties and therefore more appealing than an analysis in which Norwegian sometimes shows movement of adjectives out of αP.

The proposal put forward here is as follows: Like Northern Swedish (and in some respects like Icelandic), Norwegian allows for αP-movement to Spec-DP, but only with a restricted set of adjectives. These are the exceptional adjectives discussed in Section 4.1 above: superlatives, ordinal numbers, første ‘first’, andre ‘other, second’, siste ‘last’, eneste ‘only’, neste ‘next’, forrige ‘previous’, venstre ‘left’, and høyre ‘right’. I furthermore propose that movement of αP is not possible when a cardinal intervenes between αP and DP (as in Northern Swedish), and with ellipsis of the head noun (as in Icelandic and Northern Swedish). In those cases, D has to be spelled out by a determiner and double definiteness is obligatory despite the presence of an exceptional adjective. This proposal leads to two predictions, illustrated in (34) and (35).

The first prediction states that although determiner omission is possible with exceptional adjectives (34a), the determiner is obligatory when the adjective is preceded by a cardinal number (34b). Julien (Reference Julien2016:80-81) discusses determiner omission in Swedish and notes that cardinal numbers may not appear in front of the adjective “unless a preposed determiner is also present.” Julien treats Norwegian and Swedish similarly in this respect, and her observation may be seen as support of prediction 1 (34).

The second prediction states that the determiner is obligatory when there is ellipsis of the noun (35b), even if the adjective is an exception (35a). Julien (Reference Julien2005:43) points out that prenominal determiners obligatorily precede the exceptional adjective “if the noun is left phonologically empty.” She provides the example in (36), which is in line with the prediction about nominal ellipsis in (35).

In the next two sections, I test these predictions with two types of data: corpus data from the NDC and acceptability judgment data elicited on either written (7 participants) or spoken (7 participants) sentences. In the judgment data, all speakers judged four sentences with a cardinal number and four sentences with ellipsis of the noun. In each condition, half of the sentences contained the prenominal determiner while the other half did not. As for the corpus data, the data extracted to examine the exceptional adjectives (see Section 3) contained examples with cardinal numbers as well. These are used to test prediction 1. To test prediction 2 on ellipsis, another corpus search was conducted to find phrases with one of the exceptional adjectives directly followed by something other than a noun. These were manually sorted (similarly to the procedure described in Section 3) into phrases with and phrases without a determiner.

The data presented in the next sections show that both the corpus data and the judgment data provide support for the predictions in (34)–(35) and hence the αP-to-Spec-DP movement hypothesis.

5.3 Prediction 1: cardinal numbers

The proposal put forward in the present article is that determiner omission with exceptional adjectives can be syntactically accounted for in terms of movement of αP to Spec-DP. This movement is blocked if a cardinal number intervenes between αP and DP, and it is therefore predicted that determiners are obligatory in these phrases; see (34) in the previous section.

Before this prediction is checked in the data, it is relevant to have a closer look at plural phrases in general. Anderssen (Reference Anderssen2006:132) claims that determiner omission is “illegitimate with plural nouns,” and provides the example in (37)—cf. (34a) above. In other words, Anderssen claims that exceptional adjectives are always preceded by a determiner if the noun is plural. If this is the case, phrases with cardinal numbers cannot be used to check the proposal of αP-to-Spec-DP movement.

The Norwegian part of the NDC contains 311 phrases with an exceptional adjective and a plural noun but no cardinal, similar to (37) (out of 1,537 phrases with an exceptional adjective; see Section 4). The majority of these phrases contain the prenominal determiner (86.8%, n=270), as in (38a). However, a certain number have no determiner (13.2%, n=41), for example (38b).

The presence of the determiner is more frequent with plural nouns than with singular ones, and inclusion of the determiner seems preferred in plural contexts, while less than half of all phrases with an exceptional adjective contain the determiner (46.4%; see Section 4.1). However, more than 10% of the plural phrases do not contain the determiner, and it seems too strong to state that these phrases are ungrammatical in Norwegian. I therefore assume that determiner omission is also possible with plural nouns (at least for certain speakers), and it is predicted that the determiner is obligatory when a cardinal number is present.

Phrases with a numeral and an exceptional adjective are relatively infrequent in the corpus. A total of 62 phrases were found. A large majority of them contain the prenominal determiner (90.3%, n=56), while a small proportion occur without the determiner (9.7%, n=6). An example of each is given in (39).

Phrases like (39b) are predicted to be ungrammatical under the αP-to-Spec-DP hypothesis, as cardinal numbers are assumed to block this movement (Section 5.1). A few phrases with a cardinal number but no determiner are nevertheless found in the corpus data. Some of these may be speech errors (see footnote 16), but there may also be more fine-grained rules that are not yet fully understood. In this respect, it is interesting to note that 4 of the 6 counterexamples are adverbial phrases expressing time (like (39b)), which are not referential in the same way as canonical objects.Footnote 24 Potentially, factors like syntactic function (adverbial versus referential object) may account for some of the phrases that are unpredicted under the αP-to-Spec-DP hypothesis.

Very few cases without a determiner were found among those with a cardinal number. In addition, definite plural phrases with a cardinal number but no adjective obligatorily contain the prenominal determiner, as in (40). The NDC contains 67 phrases with the cardinal numbers 2 to 10 followed by a definite plural noun, and only one of them lacks the prenominal determiner (1.49%).Footnote 25

The available data in the NDC strongly suggest that the prenominal determiner is obligatory in phrases that contain a cardinal number, even if they also contain one of the exceptional adjectives. In addition to the corpus data, judgment data were collected to investigate phrases with exceptional adjectives. The judgment data on phrases with a cardinal number are more clear-cut than the corpus data. They are presented in Table 4.

Table 4. Acceptability judgments on modified definite phrases with a cardinal number and an exceptional adjective, with and without determiner

The results of the judgment task show that phrases with cardinal numbers and a determiner are generally acceptable in Norwegian.Footnote 26 These sentences are judged much more acceptable than phrases without the determiner, which were never judged acceptable. Most people in the judgment task considered sentences without the determiner unacceptable. It has to be noted that a few of the phrases presented in spoken form were judged to be acceptable. However, the participants in the oral judgment task were asked to repeat the sentence before they judged it, and some participants correct the sentence while they repeat it, as in (41) where a determiner was added to the stimulus sentence. These judgments were counted as “unacceptable” in the numbers presented in Table 4, as they provide indirect evidence for the prediction that the determiner is obligatory when a numeral precedes the exceptional adjective.

In summary, the data show that phrases with a cardinal number and an exceptional adjective obligatorily contain the prenominal determiner that may otherwise be omitted in front of these adjectives. The data thus lend support for the proposal that the exceptional adjectives allow for movement of αP to Spec-DP, unless something else intervenes (the cardinal number). It was also shown that phrases with only a cardinal number always contain the prenominal determiner, so cardinal numbers (or CardP) themselves cannot move to Spec-DP.

5.4 Prediction 2: ellipsis

The second prediction related to the proposal that αP moves to Spec-DP is that this movement is only possible when an overt noun is present within αP, because only elements with a referential index can move to the DP-layer (see Section 5.1). In cases of nominal ellipsis, the movement is impossible, and the determiner is predicted to be obligatory. Thus, I expect that when an exceptional adjective is found in a phrase with ellipsis, it will be preceded by a determiner (see (35) and (36) above).

This prediction is confirmed by the corpus data. The search for exceptional adjectives followed by something other than a noun yielded 1,474 phrases with ellipsis. The vast majority of these phrases contain the prenominal determiner (n=1,363, 92.5%), as in the examples in (42). Less than 10 percent of the phrases lack the determiner (n=111, 7.5%); see (43) for an example.

As noted above, even native speakers occasionally produce unacceptable phrases. It is also interesting to observe that half of the phrases without the determiner occur with the adjective eneste ‘only’ (n=56). From these, most have a very abstract meaning, as in (44).Footnote 28 In cases like these, it is hard to know which noun was elided, apart from ‘thing’, while the other examples (see (42) and (43)) clearly refer back to a specific child or bird, respectively. One might wonder whether phrases like (44) are truly referential. If the cases of eneste with an abstract meaning are excluded, only 4.4% (63 out of 1,426) of the phrases with ellipsis and an exceptional adjective lack the determiner.

When it comes to the judgment data on ellipsis and determiner omission, the results are more clear-cut than the corpus data (as was the case for cardinal numbers as well; see Section 5.3). The judgment data are presented in Table 5 below. The speakers accepted the phrases with the prenominal determiner, while none of the phrases without a determiner were accepted. This pattern is found across modalities (written and spoken), and most speakers commented explicitly on what was “wrong” with the phrases.Footnote 29

Table 5. Acceptability judgments on modified definite phrases with an exceptional adjective and ellipsis of the noun, with and without determiner

In summary, the data on ellipsis strongly suggest that determiners are obligatory in this context, even when the adjective is an exception and could otherwise appear without a determiner. Although a few cases of ellipsis without a determiner were found in the corpus data, the acceptability judgments categorically exclude them. This is in line with the predicted limitations of αP-movement as outlined in Section 5.2.

Together, the data on cardinal numbers and ellipsis indicate that there are restrictions on the omission of the determiner in front of exceptional adjectives. When a cardinal number precedes the adjective or when there is ellipsis of the noun, the prenominal determiner is obligatorily present. This can be taken as support for the syntactic analysis of exceptional adjectives proposed here. Normally, αP can move to Spec-DP when the AP contains an exceptional adjective. However, with cardinal numbers or no overt definite noun (i.e., ellipsis), this movement is prohibited, and D is spelled out as a determiner instead.

6. A note on variation

In Section 4, I distinguished different types of adjectives. While regular adjectives are always preceded by the prenominal determiner, the quantifier adjectives hele ‘whole’ and halve ‘half’ always occur without the determiner. The exceptional adjectives take an intermediate position: they may combine with a determiner but do not necessarily do so. As a result, much variation is found with respect to these exceptional adjectives.

Two types of variation have already been observed in the previous sections. First, there is variation between the different exceptional adjectives. Some adjectives typically occur without the determiner (e.g., ordinal numbers and venstre ‘left’ and høyre ‘right’), while others more frequently combine with the determiner (e.g., superlatives; see Table 1 above). In addition, there is variation between spoken and written language. In the judgment task, participants who judged spoken sentences accepted determiner omission to a higher degree than those who judged written sentences. Both types of variation show variation in preferences, not in (im)possibilities. In other words, what varies is not whether determiner omission is possible, but how frequently the determiner is omitted.

In the next two sections, I consider historical and dialectal variation. An in-depth study of the historical and dialectal variation with respect to the use of exceptional adjectives falls outside the scope of this article. Both are therefore discussed only briefly. As with the other types of variation, a variation in preference is observed.

6.1 Historical variation

This section briefly looks at variation across time in the use of determiners. To simplify the picture, all adjectives were studied together and tendencies for individual adjectives were not considered. Given the present-day variation among exceptional adjectives, variation in the historical development may also exist, but this is left for future studies.

To study historical variation, differences between age groups in the NDC were analyzed. The speakers in the NDC fall into two age groups: those younger than 30 (“group A” in the corpus) and those older than 50 (“group B”). In addition, the Language Infrastructure made Accessible (LIA) corpus was included, which is a corpus with historical recordings of dialectal speech. The recordings were made between 1937 and 1996, and the LIA corpus became available in 2019 (see footnote 5). Just like the NDC, the LIA contains recordings from all across Norway, but the LIA is bigger both in terms of speakers (1,374 vs. 438 in the Norwegian part of the NDC) and number of tokens (almost 3.5 million vs. almost 2 million).

Table 6 shows the use of exceptional adjectives with and without determiner in the LIA corpus, the old speakers in the NDC and the young speakers in the NDC. For ease of comparison, the results from the NDC as a whole (see Section 4) are also added. The picture of the two age groups in the NDC is quite similar to the corpus as a whole: In both groups, the determiner is more frequently omitted than included with exceptional adjectives. This tendency is somewhat stronger in the younger age groups, but the difference is not large. For the data from the LIA corpus the situation is different. In the older dialect recordings, more than half of the phrases with an exceptional adjective contain the determiner (54%, n = 1,770).

Table 6. Modified definite phrases with an exceptional adjective in the LIA corpus and the two age groups in the Nordic Dialect Corpus

The pattern in Table 6 may suggest that the omission of the determiner in front of the exceptional adjectives has become somewhat more frequent over time. In both the LIA corpus and NDC many examples of determiner omission can be found, however, and the difference is not very big. The recordings in the LIA corpus come from a rather wide time span, and could be divided into decades, as in Table 7. Note that the total amount of phrases is lower than in Table 6, because the year of recording is not known for all recordings and because the recordings from 1937 contained too few phrases to draw conclusions from.

Table 7. Modified definite phrases with an exceptional adjective in the LIA corpus, presented by decade based on year of recording. Total number of phrases = 2,852

The data in Table 7 do not show a clear pattern of change. In most decades, there seems to be a preference to include the determiner (apart from the 1950s). In contrast, the preference in present-day speakers (NDC; see Table 6) is to omit the determiner. This may constitute a change, but the data in general do not show a clear decline in the use of the determiner.

In sum, the data presented in this section suggest that there has been variation in the use of the determiner with exceptional adjectives from the earliest available recordings until the present day. The preference for inclusion versus omission of the determiner may have shifted, but the only conclusion that can be drawn safely is that the variation has existed for quite some time. It is not the case that exceptional adjectives always (or never) combined with the determiner in earlier recordings of spoken Norwegian.

6.2 Dialectal variation

In addition to variation over time, variation across dialects may also be found in the inclusion (or omission) of the determiner with exceptional adjectives. The Norwegian part of the NDC contains recordings from 111 locations across Norway. An in-depth analysis per place falls outside the scope of this article, and is also problematic given the low number of exceptional adjectives per location. In this section, I look at variation across areas and regions.

The “areas” in the NDC correspond to the (former) division of Norway into 18 fylker. These form five “regions” which align more or less with the five dialect groups, Northern Norway, Trøndelag, Eastern Norway, Southern Norway, and Western Norway. Although the number of phrases with an exceptional adjective is not equally distributed over the areas and regions, some observations can be made.

Recall from Section 4.1 that, overall, 53.5% of the phrases with an exceptional adjective lacked the prenominal determiner. In each area (fylke), there is a substantial proportion of phrases with and without the determiner. In other words, there are no areas in which the determiner is obligatorily included (or omitted); rather, the exceptions appear to behave as exceptions in all areas. At the same time, there is some variation. The area with the highest proportion of determiner omission is Nord-Trøndelag (78.4%, 29 out of 37), and the area with the lowest proportion of determiner omission is Rogaland (37.2%, 35 out of 94). When Norway as a whole is considered, there is a slight preference for determiner omission. There are, however, six areas with the opposite tendency, where more than half of the phrases occur with a determiner: Akershus (41.7% omission), Aust-Agder (38.9%), Buskerud (45.7%), Finnmark (45.6%), Rogaland (37.2%), and Telemark (45.8%).

Table 8 presents the dialectal variation for each region. Three of the regions are similar to Norway overall, with a small preference for determiner omission. In these regions, just above 50% of the phrases with an exceptional adjective lack the determiner. In the Trøndelag region, this preference is even stronger: here, about two-thirds of the phrases lack the determiner. In Southern Norway, on the other hand, the small majority of the phrases include the determiner. In general, the differences between the regions are not very large.

Table 8. Dialectal variation: modified definite phrases with an exceptional adjective in the NDC, presented by dialectal region

In summary, the picture arising from the data is one of dialectal variation, but all dialects have exceptional adjectives. There are some differences with respect to how frequently the determiner is included in different areas and regions, but none of them categorically includes or omits the determiner. This is similar to the other types of variation discussed in this section: There is variation along certain dimensions (adjective, modality, time, location), but all variation relates to how frequently the determiner can be omitted. The optional inclusion of the determiner is a clear pattern in all the data analyzed for this study.

7. Concluding remarks

This article has investigated exceptions to double definiteness in Norwegian. Although double definiteness is generally obligatory in Norwegian modified definite phrases, there are exceptions where the prenominal determiner may be left out. Several adjectives that do not require the determiner have been mentioned in the literature, but they had not been studied systematically. In this article, I describe these exceptions and furthermore provide a syntactic analysis of phrases without a determiner.

An analysis of the Norwegian part of the Nordic Dialect Corpus (NDC) reveals that three types of adjectives can be distinguished. First, there are regular adjectives that are always preceded by a prenominal determiner and hence occur with double definiteness (Section 4.3). In addition, there are what I refer to as “exceptional adjectives.” These may be preceded by the determiner, but this does not have to happen (Section 4.1). The following adjectives belong to this group: superlatives, ordinal numbers, første ‘first’, siste ‘last’, eneste ‘only’, andre ‘other’, neste ‘next’, forrige ‘previous’, venstre ‘left’, and høyre ‘right’. In the NDC, these adjectives occur without the prenominal determiner in slightly more than half of the occurrences (53.5%). Variation between the adjectives is found, but determiner omission is not at all infrequent. Finally, there are the adjectives hele ‘whole’ and halve ‘half’ that behave like strong quantifiers and are never preceded by a determiner (Section 4.2).

The exceptional adjectives may appear with a determiner, and this leads to much variation. Some adjectives are more likely to appear with the determiner (e.g., superlatives) while others tend to occur without one (e.g., venstre ‘left’ and høyre ‘right’). In addition, acceptability judgments suggest that determiner omission is more acceptable in spoken than in written language. Exploratory investigations of the adjectives over time and across dialects shows that the variation has existed for at least several decades and all over Norway. Variation is found, but determiner omission with exceptional adjectives is found in historical dialect recordings from the LIA corpus and in all areas in the NDC. In this study, more detailed investigations of the variation were not conducted. Future research may establish the factors that influence the inclusion versus omission of the determiner in these constructions.

An additional factor that was not investigated systematically in the present study is the role of pragmatics and discourse factors. It has been suggested by some, including Julien (Reference Julien2002, Reference Julien2005), that the prenominal determiner may be omitted with all adjectives if the referent is active in the discourse. Indications for this can also be found in the data of the present study (see Section 4.3), but future studies including carefully designed acceptability judgments may be able to provide conclusive evidence for the role of pragmatics.

The Norwegian modified definite phrases without a determiner look similar to the Northern Swedish vernaculars and, to some extent, to Icelandic. In Section 5, I propose a syntactic analysis of the phrases with an exceptional adjective that follows Julien’s (2002, 2005) analysis of these other Scandinavian languages. Both the spoken language in the NDC and acceptability judgments support this proposal, although there are a few counterexamples that currently cannot be accounted for. I therefore analyze the phrases without the determiner as a case of αP-movement. In these phrases, αP – which includes the adjective and definite noun – moves to Spec-DP, such that the D-projection contains phonological material and D does not need to be spelled out by a determiner. There are limitations on this movement: when there is a cardinal number or ellipsis of the definite noun, αP cannot move and D is spelled out. In this respect, Norwegian is more similar to Northern Swedish than to Icelandic, as αP can move across cardinals in the latter.

In this article, I argue that some aspects of Icelandic and Northern Swedish syntax are also found in Norwegian. However, αP-movement in Norwegian is only found with certain adjectives, i.e., the exceptional adjectives. The regular adjectives occur in double definite phrases, while hele ‘whole’ and halve ‘half’ appear above DP in the projection for strong quantifiers. By investigating variation within a language and comparing the patterns to closely related languages, this article contributes to the description of Scandinavian nominal phrases and an understanding of the patterns of variation therein. For the other double definiteness languages, Faroese and Swedish, exceptional adjectives have also been described in the literature (see Section 2). In future work, it could be investigated whether these can also be accounted for by αP-to-Spec-DP-movement.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to two anonymous reviewers and Terje Lohndal for their helpful comments and suggestions on this paper. I would also like to thank the participants of the acceptability judgment tasks, and all colleagues who have shared their intuitions about double definiteness with me.