‘…ɛὐιππου βασιλῆι Κυράνας…’ ‘King of well-horsed Cyrene’. (Pindar, Pyth., IV, 6–8); ‘…ἱπποβότου Λιβύης…’ ‘Libya, the horses’ pasture-land (Oppian, Cynegetica, II, 253); ‘…ἱπποτρόφος…’ The city is (Cyrene) horses feeding (Strabo, XVII, 3. 21)

Introduction

Rearing horses in Cyrenaica seems to have been an ancient tradition. The presence of this animal in the region is indicated by archaeological evidence from the prehistoric era, around, or after, the period of the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550–1352 BC), as the first piece of evidence is found in Egypt at the time of this family (Klecel and Martyniuk Reference Klecel and Martyniuk2021; Willekes Reference Willekes2013, 66). It seems that horses were domesticatedFootnote 1 by the indigenous people of Cyrenaica long before the Greek occupation, which may explain their experience of horse breeding. An engraving of a horse and a man has been found at a prehistoric rock art site called Kaf Tahr, located in the Green Mountain (al-Jabal al-Akhdar). Marini et al. (Reference Marini, De Faucamberge and Katab2010, 275) suggest that the engraved horse probably dates to the Protohistoric period (the transition period between the prehistoric and historic eras, around 2000–1200 BC), which is known in south-west Libya as the Libyco-Berberian period or ‘horse phase’ (Le Quellec Reference Le Quellec2012, 22, 23). In the Classical period, breeding horses in Cyrenaica was a topic for ancient Greek and Roman writers. They explored diverse themes telling us interesting stories about this noble animal (Abdelhamed Reference Abdelhamed2018a, Appendix. I. D. 3). Literary references to horses appear under two main categories: the first highlights their breeding and breeding traditions with direct and indirect literary references; the second focuses on the success of Cyrenaican horses and charioteers in the Greek and Roman games. These achievements were in most cases associated with the name of Cyrene.

It is important to clarify here that before the Roman period Libya means Cyrenaica – it certainly did to Pindar and his contemporaries such as Sophocles: the first Greek contact was confined to Cyrenaica, though it was also named Libya by many other writers. Herodotus, who is probably the best example, devoted his fourth book to the story of the founding of Cyrene by the Therans, featuring the names of people and places in Cyrenaica, such as Battus, the nymph Cyrene, Cyrene the city, Apollonia and others. These key names help us to recognise which part of Libya or North Africa the writer refers to. Sophocles (Electra 701–8), for instance, describes a horse race in which two competitors are from Libya. Although in this passage he does not specify that they are from Cyrenaica, it is understood from another line in the same poem where he mentions that one of them is from Barce (Electra 727). Pindar also, in his fourth Pythian (6, 7), describes Battus as the founder of crop-bearing Libya ‘…οἰκιστῆρα Βάττον καρποφόρου Λιβύας…,’. Here we can see that the writer links the name of Battus to Libya.

The quality of Cyrenaican horse-breeding skills in the Classical and Hellenistic periods

Several ancient writers comment on the high quality of the horses bred in Cyrenaica (Abdelhamed Reference Abdelhamed2018a, Appendix. I. D. 3). Pindar (Pyth., IV, 1–3) emphasises the quality of the horse when describing the king of Cyrene and his noble horse ‘…ɛὐιππου βασιλῆι Κυράνας…’, ‘King of well-horsed Cyrene’. He links good horses with Cyrenaica when he explains how Battus, the coloniser of the fruit-bearing Libya, left his island Thera in order to find the city of fine chariots [Cyrene] on a white hill ‘…Βάττον καρποφόρου Λιβύας, ἱɛρὰν νᾶσον ὡς ἤδη λιπὼν κτίσσɛιɛν ɛὐάρματον πόλιν ἐν ἀργɛννόɛντι μαστῷ…’ (Pindar Pyth., IV, 6–8). Herodotus (IV, 189) describes the customs and traditions of the Libyan tribes, and claims that the Greeks learned to drive the quadriga from the Libyans:

Καὶ τέσσɛρας ἵππους συζɛυγνύναι παρὰ Λιβύων οἱ Ἕλληνɛς μɛμαθήκασι (Herodotus IV, 189).

The Greeks have learned from Libyans to yoke four horses together [using four-horse chariots] (Author's translation).

Hyginus (Astronomia, II, 24) states that some authors, including Callimachus, reported that Berenice II, daughter of Magas of Cyrene who died in 250 BC, ruled Cyrenaica from 258 BC to 246 BC, was interested in raising horses and used to send them to Olympia. Strabo (XVII, 3.19) confirms that the Ptolemaic kings had a monopoly on horse breeding, and that the colts increased by a hundred thousand every year.Footnote 2 Although Strabo mentioned this when he was describing people living in the desert, he apparently included Cyrenaica and the surrounding area. He cites Callimachus referring to the breeding of horses in Cyrene (Strabo, XVII, 3.21): our country [Cyrene] famed for its good horses (μήτηρ ɛὐιππου πατρίδος ἡμɛτέρης).Footnote 3 Strabo also refers to the excellent quality of land which was peculiarly suitable for breeding steeds:

ηὐξήθη δὲ διὰ τὴν ἀρɛτὴν τῆς χώρας: καὶ γὰρ ἱπποτρόφος ἐστὶν ἀρίστη καὶ καλλίκαρπος

The city flourished from the excellence of the land, which is very well adapted for breeding horses and for the growth of good harvests (Strabo XVII, 3.21).

This clearly indicates that the main reasons the region was able to produce high-quality horses was its agricultural fertility, as Cyrenaica is referred to as ‘καλλίκαρπος’. It is worth mentioning that Strabo's (XVII, 3.21) account seems to be based on earlier information from Callimachus, who lived in the early Hellenistic period. Athenaeus, at the end of the second and beginning of the third century AD, may support his point. Athenaeus (Deipnosophists, I, 100f) reported the speech of Antiphanes (a comedy writer in the fourth century BC), who mentioned that any discussion of Cyrene during Ptolemy's regime was dominated by two words, ‘silphium’ and ‘horses’, presumably referring to the fact that in this period, silphium was a very significant economic resource belonging to CyrenaicaFootnote 4 (Chamoux Reference Chamoux, Barker, Lloyd and Reynolds1985, 170). If this was the case, then associating horses and this plant is perhaps a sign of its importance to the people of Cyrene at that time. Strabo (XVII, 3.19) reported that horse breeding was of special interest to the Ptolemaic kings such that colts proliferated by a hundred thousand every year. Although he does not refer to Cyrene in particular, the large number of colts reflects the value of breeding horses in general to the Ptolemaic kings.

The distinctiveness of Cyrenaica's horses and chariots in the Hellenistic era is evident from a reference made by Diodorus Siculus in the first century BC. He informs us that Cyrene sent a delegation to Egypt to meet Alexander and present him with gifts of horses and four-horse chariots (Diodorus Siculus XVII, 49 (2)):

ἐν οἷς ἦγον ἵππους τɛ πολɛμιστὰς τριακοσίους καὶ πέντɛ τέθριππα τὰ κράτιστα.

Three hundred warrior horses and five of the most excellent four-horse chariots.

Some of Pausanias’ narratives may support the view that horses and chariots in Cyrenaica were used as gifts, or as a figure or symbol to represent Cyrene, common from the time of the Battiad family (seventh century to the first quarter of the fifth century BC). Pausanias (X, 15.6) reports, while he is talking about votive offerings given by different nations at Delphi, that ‘the Cyrenians dedicated at Delphi a figure of Battus in a chariot; as he was the man who brought them in ships from Thera to Libya…’. This chariot would be led by two or four horses as Pausanias adds: ‘The reins are held by Cyrene (Nymph), and in the chariot is Battus who is being crowned by Libya (local Goddess).’ He also mentions another dedication at Delphi, which includes a chariot with an image of Ammon (Local God) (Pausanias, X, 13.5).

Pausanias's accounts mention significant political and religious figures that represent Cyrene; Battus, Cyrene (nymph), Libya (goddess) and Ammon (god). Associating horses with these figures is probably an indication that horses were one of the distinctive features of Cyrene from the seventh century BC and thereafter as he wrote about past generations. Other writers, in the fourth century BC, such as Xenophon (Cyropaed, VI, 1.27–28) and Aeneas Tacticus (XVI, 14–16) highlighted the significant use of horses in the army – the latter stressed the benefits of using large numbers of horses and chariots in the army of Cyrene and Barca. In the epigraphic evidence from Cyrene, the job of the instructor who trained horsemen is mentioned by Ptolemaios’ diagramma (IGCyr010800). All of these references suggest the availability of horses in large numbers at Cyrenaica and that rearing them was one of the essential branches of animal husbandry.

Libyan experience in breeding horses in the Classical and Hellenistic periods and its impact on the Greek breeders themselves appears to have continued as a source of inspiration for some historians during the Roman period. Pausanias (VI, 12.7) provided a memorable description of the achievements of Theochrestos (Θɛόχρηστος) of Cyrene and his family winning the Olympic and Isthmian games with four-horse chariots across approximately two centuries. This account makes another interesting point underlining that the Libyans were renowned experts in horse husbandry, because Theochrestos and his family apparently bred their horses ‘in the Libyan way’:

Θɛόχρηστον δὲ Κυρηναῖον ἱπποτροφήσαντα κατὰ τὸ ἐπιχώριον τοῖς Λίβυσι καὶ αὐτόν τɛ ἐν Ὀλυμπίᾳ καὶ ἔτι πρότɛρον τὸν ὁμώνυμόν τɛ αὐτῷ καὶ τοῦ πατρὸς πατέρα, τούτους μὲν ἐνταῦθα ἵππων νίκας, ἐν δὲ Ἰσθμῷ τοῦ Θɛοχρήστου λαβɛῖν τὸν πατέρα, τὸ ἐπίγραμμα δηλοῖ τὸ ἐπὶ τῷ ἅρματι (Pausanias VI, 12.7).

Theochrestos of Cyrene bred horses after the traditional Libyan manner; he himself and before him his paternal grandfather of the same name won victories at Olympia with the four-horse chariot, while the father of Theochrestos won a victory at the Isthmus. So declares the inscription on the chariot.

Theochrestos’ grandfather won the chariot race at Olympia in 360 BC and his father at Isthmia in 300 BC. They bred their horses following the Libyan method and the fact that they won the races indicates distinctive Libyan skills in horse rearing. Even if we assume that these achievements were simply a result of a family association, with the knowledge of hippotrophia ‘ἱπποτροφία’ passed down from one generation to the next, Pausanias’ writing is very important and could support the suggestion that there were successful or noticeable traditional Cyrenaican methods of breeding horses in Libya, especially at Cyrene, the city of Theochrestos. This may have led the Greeks to adopt these skills when they bred their horses (cf. Herodotus IV, 189). Additionally, according to Pausanias, an inscription on the chariot may reflect how people were proud of this man and his city, Cyrene.

The quality of Cyrenaican horse-breeding skills in the early to late Roman periods

More details on the distinctive characteristics of the Libyan horse come from accounts of some writers who lived during the Roman period. OppianFootnote 5 (Cynegetica, I. 166–75), for instance, lists the Libyans among tribes who lived by breeding horses and had good skills in horse racing. These tribes seem to have included those who live in Cyrenaica; in another passage he observes that the Libyan horses including those from Cyrene are strong and have notable endurance on the racetrack (Oppian, Cynegetica, I, 291–99). The high speed of Libyan horses appears to be one of their most celebrated features as they excelled in both equestrian competitions and hunting, according to Oppian (Cynegetica, IV, 44–57). He also describes Libya as the horses’ pastureland or as the feeder of horses (ἱπποβότου Λιβύης) (Oppian, Cynegetica, II. 253) – as for many other authors, here ‘Libya’ means ‘Cyrenaica’. The meaning of ἱπποβότου is similar to ἱπποτρόφος, used by Strabo (XVII, 3.21) referring to Cyrenaica as an excellent place for breeding horses.

The qualities of the horses and Libyan horse-breeding skills are also mentioned in another work dating to the second century AD. The work of Aelian (AD 175–235), which provides important data about the different kinds of animals bred during the Roman period, is a good example of this. In the section on horses, Aelian (Characteristics of Animals, III, 2, cf. XIV, 10) first addresses the characteristics of Libyan horses, and compares them with Persian horses, which were well known for their quality. Aelian emphasises that Libyan horses are fast even if they are neglected by their owners, who do not rub them down, clean their hooves or wash them, and they are thin but not well-fleshed. They are obedient to the degree that after each journey the horses could be set loose to graze. He describes these horses as being like their owners, the Libyans, who are as thin and as dirty as their horses.

Although Aelian mentions that Libyan horses are dirty, he emphasises their stamina: ‘they know little or nothing of fatigue’. He mentions again, in another book, that Libyan horses gallop at a very great speed (c. XIV, 10),Footnote 6 an advantage for hunting animals: ‘Gazelles (of Libya) are swift of foot but for all of that they still cannot outrun Libyan horses.’ The quality of the Libyan grazing land for the horses is also mentioned (cf. Strabo, XVII, 3.21), making horse husbandry easier for Libyans. Even if we assume that Aelian may have used information from Oppian's account, his work is still very important, for example, comparing Libyan horses to Persian horses, well known for their high quality, and he obtained some of his information from the narratives of Libyans:

ἵππου δὲ τῆς Λιβύσσης πέρι Λιβύων λɛγόντων ἀκούω τοιαῦτα. (Aelian, Characteristics of Animals, III.2).

‘Regarding the Libyan horses, this is what I hear (learn) from what the Libyans say’(Author translation).

Libyan horses from North Africa and from Spain were famous during the Roman Empire for their participation in horse racing (Devitt Reference Devitt2019, 210). An honorific inscription from Rome, dating back to the beginning of the second century AD, records a list of racing horses and their breed, or place of origin (CIL VI.10053; Devitt Reference Devitt2019, 210). The text lists 74 names of horses, with 46 coming from North Africa, plus 28 specifically from Cyrenaica and Mauretania (Devitt Reference Devitt2019, 49, note 105). The great performance of African horses in horse racing is understood from further epigraphic evidence from Rome, dating to the second half of the second century AD (|CIL VI.10056; Devitt Reference Devitt2019, 49). This inscription records the names of 122 horses. Although the text does not mention the origin of each horse, it does indicate that the honoured charioteer won 1,378 races with Spanish horses and 584 with African horses. It is worth mentioning that some of the Spanish horses were probably of African origin. Donaghy (Reference Donaghy2014, 43) states that African horses were taken to Spain for breeding. Literary accounts and epigraphic evidence demonstrate the importance of the African horses to the Romans, in particular for horse racing.

At Cyrenaica, the various local representations of the hero cult, in particular Heracles (who was associated with athletics) and the horse on some cultural materials, are important evidence of the region's involvement with horses and their importance to society. As we know, alongside the different gods and goddesses that the Greeks and Romans worshipped were some heroes – real or mythological, such as Hercules, Achilles, Odysseus and others.Footnote 7 Cyreneans, and other Greek and Roman nations, seem to have worshipped different heroes. Battus, the founder, and Cyrene, the nymph, are good examples. Pindar (Pyth. V.94, 95) mentioned the cult of Battus: ‘he (Battus) was blessed when he dwelt among men and, thereafter, a hero worshipped by the people’.Footnote 8 Heracles was also revered by people of Cyrenaica (IGCyr022300), as seen in the dedications he received, which are mainly in contexts associated with sport, including riding horses (GVCyr015; IGCyr100700; GVCyr034). Additionally, horsemen seem to be one of the heroised figures that appeared in the region from the Hellenistic period (IGCyr134900; IGCyr118600). An interesting example of a hero equitans is represented by a relief sculpture from Cyrene, dating to the beginning of the Roman period (IRCyr.C.466; Figure 1). This is one of a number of heroised riders’ relief sculptures which have been found in the sanctuary of Demeter and Kore of Wadi bel Gadir (وَادِي بِالْغَدِير) at Cyrene (Kane Reference Kane2003, 27–34). The relief represents a figure of a man on horseback with a draped woman in front, and a boy who stands beside a cylindrical altar. There is an inscribed stele above the boy and a snake under the horse. Strong and spirited-looking, the horse resembles the native Libyan breed of horses known from antiquity, a type from which modern horses developed (Hyland Reference Hyland1990, note 6.11–14, 24–27, 177). The name of a young man is written on the stele (IRCyr.C.466, 467). Kane (Reference Kane2003, 28) suggests that the group of heroised riders reflects the traditional interest of the Cyreneans in the local hero cult. Thus, as our heroes are horse riders, this iconic representation may signify the importance of breeding horses in the society of Cyrene. Also, the relief sculpture is carved in a marble panel, possibly reflecting the social value and respect for horses and their riders in this city.

Figure 1. A relief sculpture from Cyrene showing a hero equitans type. Source: IRCyr. C.466 .

The anonymous geographical work Expositio Totius Mundi et Gentium (LXII), written in the mid-fourth century AD, states that horses and grain were essential Cyrenaican products. Spain and Africa were recommended as among the top choices for acquiring good horses (Expositio Totius Mundi et Gentium cited in Hyland Reference Hyland1990, 210). In addition, Synesius, c. AD 370–413, (Letter, 40) emphasises the good quality of Cyrenaican horses. He provides us with additional details about Cyrenaican horses in a letter to his friend at Nesaea (in Persia). Synesius is sending a horse as a gift from Cyrenaica to Nesaea, the country of the most beautiful horses, which shows the importance of the distinctive characteristics found in Cyrenaican horses that were not found in those of Nesaea. In the same letter, Synesius discusses the versatility of the horse, which can be used for racing, hunting, chariot-racing and war. Synesius makes an important point relating to the use of horses to celebrate victories at Cyrenaica. He states that ‘the horse can be used to lead ceremonial processions in honour of victory over the Libyans…’. Synesius describes Cyrenaican horses and compares their appearance with horses from Nesaea, stating that Cyrenaican horses were less beautiful because of their big heads; they were also thinner than Nesaean horses (cf. Aelian, Characteristics of Animals, III.2; cf. XIV.10). The writer (Letter, 130) also points out that the source of wealth of most of the residents of Cyrenaica was their cattle, herds of camels and horses. He wrote this while complaining about barbarian attacks and the lack of security organised by the rulers, leading to a loss of horses in Cyrenaica. However, this only seems to have been the case during the unsettled years.

Libya, and Cyrene in particular, maintained their reputation for animal breeding during the mid-Roman and Byzantine periods, especially with regard to horses. In the middle of the third century AD, Bishop Dionysius of AlexandriaFootnote 9 (Periegetes, 213) stated: ‘Cyrene the place of fine horses’. Khan (Reference Khan2002, 64–67) argues that most of Dionysius’ work is based on previous writers; however, his statement confirms the general reputation of Cyrene, in the past or in his time, for horse rearing. Additionally, Synesius (Letter, 40) mentions the good quality of the horse that he sent to his friend, and emphasises its benefits for hunting or competitions in the hippodrome. Also, Priscian (Poetae Latini Minores, 197) in AD 500 describes the city as ‘the mother of renowned horses’– ‘clarorum mater equorum’.

Imagery depicting horses and riders continued as a favoured theme amongst Cyreneans during the sixth century AD. An image of a horse rider appears in different views on a mosaic floor at the eastern church at Qasr Libya (قصر ليبيا) (Figure 2) (Project for recording and protecting the site of Qasr Libya 2017, 13. Fig. 27; Ward-Perkins and Goodchild Reference Ward-Perkins and Goodchild2003, 266–86). Qasr Libya is located about 50 km to the west of Albaida (البيضاء). In the fifth century AD, it was called Olbia, and in the sixth century was named Theodora, after Justinian's wife (527–565 AD). As Theodora was living in Cyrenaica before her marriage to Justinian and her name was given to the city of Qasr Libya, this may suggest that she gave this city particular attention. If so, using figures of horses on the mosaic may reflect her keen interest in equestrian sport.

Figure 2. An image of a horse rider on a mosaic floor, dating to the sixth century AD, found in the eastern church at Qasr Libya. Source: Jona Lendering, Marco Prins: https://vici.org/vici/11425/ (accessed 7 August 2023).

Although there is no information about the Cyrenean horse in the accounts of the medieval Arab travellers and early modernFootnote 10 European travellers, the UK Foreign Office, in 1887, reported that horses were among the commodities exported from Benghazi to Tripoli (cited in Suliaman Reference Suliaman2017, 151). Although horses were regarded as noble animals with a high status, they were also used for ploughing land in Cyrenaica during the Ottoman and the beginning of the Italian periods. This role was generally associated with oxen in ancient times in Cyrenaica and beyond, with horses rarely being used for agricultural work in the pre-medieval period, but the horse collar for pulling ploughs and other farm implements did exist. The increased use of horses on farms in some countries appears to have started between the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries (Lambert Reference Lambert2023, 158, Figure 13). At Cyrenaica, horses may have been used on medieval farms because of their physical strength – a reasonable suggestion, given that grain has been one of the most significant export products from the region across the ages (Abdelhamed Reference Abdelhamed2018a, 74–116). Also, horses were able to plough at a greater speed (Langdon Reference Langdon1982, 40). Suliaman (Reference Suliaman2017, 166) investigated the expense of ploughing a barley field in Benghazi in 1920, including documented evidence for horse fodder. They may have been used for ploughing as well as for riding to the fields for supervising the workers, transporting the grain to storage and other functions. The use of horses in Cyrenaica to cover the oxen's job on farms during the Ottoman and then at the beginning of the Italian periods, and possibly before that during the medieval, can be explained also by the economic value of oxen: the breeding of oxen in Cyrenaica was an export trade during the nineteenth century, resulting in the need to use horses for farm work. In 1850 the French consul reported that the total annual cattle exports to Egypt and Malta sometimes reached up to 40,000 (Bresson Reference Bresson and Archibald2011, 89, 90; Wright Reference Wright1982, 22). Furthermore, in 1894, Bertrand, the French consul in Benghazi, stressed the good quality of Cyrenaican beef (Laronde Reference Laronde1987, 331). In short, the thriving Cyrenaican cattle meat market led to the increased use of horses on farms.

Cyrenaican charioteers’ achievements in the Greek and Roman games

The literary sources and the available regional epigraphic and other archaeological artifacts related to the ephebateFootnote 11 could provide us, directly or indirectly, with some information about the international and local interest in training young men to use horses for entertainment, as well as the contribution of Cyrenaican charioteers to the Greek and Roman games.

Winners and celebrations of charioteers in the Classical period

The celebration of Cyrenaican horsemen and their horses in Classical Greek contests, in particular in chariot races, was highlighted by many literary references. The earliest indications are from Pindar (Pyth. IV.1–3, 59–76; V.40–53; IX.1–4), who on several occasions reported the remarkable contribution of Cyrenaican horses in the Pythian and Olympic Games in the early fifth century BC. He gave the names of some of Cyrene's horsemen and their horses who won these famous games. Well-known examples of this can be seen in three of Pindar's twelve Pythian Odes. He was commissioned to deliver them as a reward for victory in chariot-races at Delphi. The fourth, fifth and ninth Pythians were dedicated to celebrating a Cyrenaican chariot-race victory. Pindar devoted his ninth Pythian to praising Telesicrates (Τɛλɛσικράτɛς), the Cyrenaican chariot winner of the year 474 BC (Pindar, Pyth. IX.1–4). Pindar highlighted the fame of Cyrenaican athletes in the Greek games:

ἐν πολυχρύσῳ Λιβύας ⋅ ἵνα καλλίσταν πόλιν.

ἀμφέπɛι κλɛινάν τ’ ἀέθλοις (Pindar, Pyth. IX. 68, 69).

Libya, the rich in gold, where she possesses a city most beautiful and famous for (victory in) competitions.

There can be no doubt that the city alluded to here is Cyrene, but describing Cyrenaica in this context to be ‘rich in gold’ requires some discussion. The word ‘gold’ was probably meant to imply that the city had abundant economic resources, such as agricultural products and animal husbandry. However, there are a number of reasons to believe that ‘gold’ may also have been a metaphorical expression for Cyrene's equine wealth. One of these reasons is that Pindar (Pyth. IX.6, 7) used another term in the same poem to represent the region's potential for cultivation and breeding animals when he described Cyrene's plentiful sheep (πολυμήλου) and high agricultural capacity (πολυκαρποτάτας). At the beginning of his poem, to honour a Cyrenean chariot champion, he describes the chariot of Apollo, which carried his girl ‘Cyrene’ to the city of Cyrene, as golden (…χρυσέῳ … δίφρῳ…). Gold in this context is thus associated with Cyrene's wealth and chariots. Beauvais (Reference Beauvais2015, 79; cf. Carson Reference Carson1982, 124) considers the words (…χρυσέῳ … δίφρῳ…) to be referring to the light of the hills of Cyrene, as the champion's victory makes Cyrene a dazzling place. Despite the fact that Pindar was paid to praise these particular people in the three Odes of Cyrene, he uses a particularly interesting terminology. The terms πολυμήλου, πολυκαρποτάτας, πολυχρύσῳ Λιβύας and καλλίσταν πόλιν are all clear indications that Cyrenaica possessed great economic resources (cf. Herodotus IV.155, 157, 159; Strabo XVII.3.21). These terms indirectly represent some general features associated with Cyrene from a Greek perspective, which led the Greeks to make Cyrenaica one of their colonies (Jones, A. Reference Jones1971, 64–69; Jones, G. Reference Jones, Barker, Lloyd and Reynolds1985, 27–41).

In the fifth century BC, Sophocles also refers to Cyrenaican charioteers (Electra, 701–708). The value of this testimony lies in its interesting description of a four-horse race and Sophocles’ viewpoint. He indicates that there were ten competitors, two of whom were from Cyrenaica in Libya, while the remaining eight each represented a different Greek city, including Athens:

ɛἷς ἦν Ἀχαιός, ɛἷς ἀπὸ Σπάρτης, δύο

Λίβυɛς ζυγωτῶν ἁρμάτων ἐπιστάται⋅

κἀκɛῖνος ἐν τούτοισι, Θɛσσαλὰς ἔχων

ἵππους, ὁ πέμπτος⋅ ἕκτος ἐξ Αἰτωλίας

ξανθαῖσι πώλοις⋅ ἕβδομος Μάγνης ἀνήρ⋅

ὁ δ’ ὄγδοος λɛύκιππος, Αἰνιὰν γένος⋅

ἔνατος Ἀθηνῶν τῶν θɛοδμήτων ἄπο⋅

Βοιωτὸς ἄλλος, δέκατον ἐκπληρῶν ὄχον (Sophocles, Electra 701–708).

One was an Achaean, one from Sparta; two masters of yoked cars (chariots) were Libyans; Orestes, driving Thessalian mares, came fifth among them; the sixth was from Aetolia with chestnut colts; a Magnesian was the seventh; the eighth, with white horses, was of Aenian stock; the ninth hailed from Athens, built of gods; there was a Boeotian, too, manning the tenth chariot.

Sophocles’ description reflects the importance of the Libyan chariots (Cyrenaican) in the Greek world as two of them were competing against others from famous places such as Athens. The account also suggests that Cyrene was not the only Cyrenaican city to produce skilled charioteers. Sophocles (Electra, 727) states that one of the Libyans was from Barce, calling to mind the observation of the military writer Aeneas Tacticus, who lived in the mid-fourth century BC. He (XVI.14, 15) states that Barce and Cyrene were examples of Cyrenaican cities known for their use of large numbers of chariots in warfare – for battle, for quickly deploying combatants and their equipment to the field of the battle, for transferring the wounded to the city and for many other purposes. He also reports that chariots were used for protecting the heavily armed troops when they attacked the enemy. Despite the fact that the Libyan chariots were eliminated very soon in this competition, it seems they were quite confident and had high expectations for winning. More than one Libyan may have participated in each horse-racing competition, as suggested by Arcesilaus of Pitane (Nelson Reference Nelson2020, 5, 6), who lived at the end of the fourth/beginning of the third centuries BC: ‘Many chariots came from Libya…’ ‘[πο]λ̣λὰ μὲν ἐγ Λ[ι]βύης ἦλθ’ ἅρματα,…’ The Greeks may have considered the Libyans as strong charioteer competitors.

Cyrenaican participation in horse-racing competitions from the Classical period is represented by Panathenaic amphorae found in the region. The competitors in the Panethenaia at Athens were ephebes who represented cities from different places in the Greek world. Prize amphorae have been found in the excavated tombs at Tocra and other places in the region, such as Alslaia near Barce (El-Marj), Cyrene and Euesperides (Dennis Reference Dennis1970, 177–79; Elrashedy Reference Elrashedy, Barker, Lloyd and Reynolds1985, 406, 407; Laronde Reference Laronde1987, 143, 145–48, figure 38; Vickers and Bazama Reference Vickers and Bazama1971, 69–84). The earliest Cyrenaican Panathenaic amphora is that of Alslaia, which shows a view of an athletic completion. The tomb of Alslaia almost certainly related to victory in the games, suggested by the Panathenaic amphora and olive wreath found there (Vickers and Bazama Reference Vickers and Bazama1971, 69–84), dated to the end of the sixth and beginning of the fifth centuries BC. Although the amphora of Alslaia does not have scenes of equestrian sport, this evidence signifies the region's early involvement in the Panathenaic games. However, the most interesting example of these is a Panathenaic prize amphora found at Tocra and dated to the end of the fifth century BC. This seems to have been given to a winner of the four-horse chariot race in the Panathenaia. A view of a four-horse chariot race is represented on one side of the amphora and the goddess Athena appears on the other side.Footnote 12 This archaeological evidence confirms the involvement of the Cyrenaican cities in the Panathenaic games at least from the fifth century BC and supports relevant literary references. Non-Athenian citizens were allowed to participate in the Panathenaic Games during the Classical period, as demonstrated by Panathenaic vases found in different places such as Taranto, Chiusi and Vulci in Italy, Kouklia on Cyprus and Naukratis in Egypt and other places in the Mediterranean world (Merante Reference Merante2017, 16; Popkin 2012, 228). Finding these amphorae in non-Athenian contexts can be explained by trade or their use as gifts. The winner of the four-horse chariot race received the largest number of amphorae (up to 140), each of which was filled with sacred olive oil (Mann and Scharff Reference Mann and Scharff2020, 165) that the winner sold at Athens instead of making payment for shipping these vases to his home. Nevertheless, the Panathenaic amphora found at Cyrenaica was most probably brought by Greek winners from Libya. The data highlighting the participation of Cyrenaican horses in the Panathenaic games can be seen in the list of Cyrenaican winners in Table 1, with six names out of eleven charioteer winners in different Greek games dating to the fifth and fourth centuries BC. Furthermore, Theochrestos II of Cyrene was one of seven victors in the four-horse chariot race in the third century BC as listed by Moretti (cited in Remijsen Reference Remijsen2009, 250).

Table 1. Cyrenaican charioteer winners, historical dates and the names of the festivals or their locations (for the literary sources accounts, see Abdelhamed Reference Abdelhamed2018a, Appendix. I. D. 3).

It is important to mention that the horse is among the most common representations on different cultural materials in Cyrenaica from the Classical era or before. Brandt (Reference Brandt2012, 169, 170) examined seven visual themes represented on pottery discovered in three different sanctuaries in Athens, Samos and Cyrene, dated to the period between the seventh and fifth centuries BC.Footnote 13 His investigation focused on Attic black-figure ware. This includes vessels for storage, serving, cooking and ritual usage. Heroes, especially Heracles, and horse scenes, such as hunting, racing and cavalry fighting, were among these different subjects. Both themes are well represented in the data from Cyrene, particularly the horse themes. Comparing the data provided by Brandt (Reference Brandt2012, 170. Table 5.4), the theme of horses is represented on 23 vases out of 420 at Athens (5%), 20 out of 63 at Samos (32%) and 25 out of 60 vases at Cyrene (42%). Horse themes were thus most frequent in Cyrene, appearing on about half of the vases (Figure 3). This also demonstrates that horses were important in Cyrenaican society and may have been associated with luxury. Brandt (Reference Brandt2012, 170) states that the high distribution of Heracles themes is linked to varied occasions including those related to cult. Perhaps the Heracles cult at Cyrene is evidence of an interest in sport, including equestrian sports.

Figure 3. An illustration of the percentages of horses on Attic black-figure vases collected from Athens, Samos and Cyrene. Source: data from Brandt Reference Brandt2012, 170.

Winners and celebrations of charioteers in the Hellenistic and Roman periods

Celebrating winners in horse racing from Cyrenaica in the Greek games seems to continue in the Hellenistic period, as indicated by some ancient sources, such as mention of the region's women in the Panathenaic games. The most interesting example of this is the poem The Victory of Berenice, written by Callimachus in honour of Berenice II (267 or 266 BC–221 BC), the daughter of Magas of Cyrene (Fantham Reference Fantham1995, 146). It is the first known poem written to celebrate a woman's achievement in athletic activities. Callimachus celebrated the victory of her quadriga at the Nemean games and frequently stated that this ode was devoted to the victory of her horses:

ἡμ[ɛ]τɛρο.[……].ɛων ἐπινίκιον ἵππων.

our epinician for your horses’ victory (Callimachus, Aetia, III, Fr. 54. 3, 4)

Despite the fact that Berenice II was a queen, acting as a ruler, her honour reflects the importance of the horse in Cyrenaica's culture to the extent that even women were associated with the region's horse-riding events. It is important to mention that the winner of chariot races was not the man who drove the chariot, but the owner of the horses and chariot. This explains why women could also win. This was made possible if the owners were wealthy, the more so if they were queens. Such people had the financial potential to train contestants at a high level. It seems that Ptolemaic dynasts, including the female members, had a great history of equestrian victories, reflecting the importance of breeding horses and training them to participate in the different Greek games. At the beginning of the Hellenistic period members of the Ptolemaic family, especially the females, were able to show that they were proud of their victories (Mann and Scharff Reference Mann and Scharff2020, 172, 173). This can be understood from the victor epigrams of Posidippus of PellaFootnote 14 (Hippika, 78, 79, 82, 87, 88), which were found in Egypt. Five out of the 18 victor epigrams are devoted to victors of the Ptolemaic family. The poems reflect the involvement of Ptolemaic royal women in equestrian and Greek athletic games. Mann and Scharff (Reference Mann and Scharff2020, 179, note 70) suggest that two royal epigram fragments, among the 18, could also have belonged to Ptolemaic victors (Epigrams 80 and 81).Footnote 15 The difference between the work of Posidippus and that of Callimachus is that Berenice II appears to be the speaker in the first epigram of Posidippus, which may suggest that the epigrams were requested by Berenice. However, in Callimachus’ poem, it looks as if he dedicated his work to celebrate Berenice's victory.

Callimachus may have been paid to praise the victory of Berenice in his poem, or perhaps his loyalty to his city was his motivation, but there are other interesting local Hellenistic metrical epigraphic data on the practice of equestrianism in the region. These include dedications, celebrations and honouring of athletes made by ordinary people on different kinds of stones. In some cases, low-quality local limestone was used, as in the case of the inscription GVCyr036, but its place in the temple of Apollo suggests its value.

Cyrenaican ephebes equestrian training during the Hellenistic and Roman periods

Equestrian training for youths seems to have been practised at Cyrenaica during the Hellenistic and Roman periods or possibly before. Terminologically, even though the expression ‘horse-riding’Footnote 16 (ἡ ίππασία) has not been attested in Cyrenaica, the cavalry instructor who was appointed to train the ephebes in equestrianism had the local name ἀπορυτιάζων, at least during that time. This regional word was present in a number of the ephebic inscriptions of Cyrene dating to both Hellenistic and Roman periods. The inscriptions IGCyr015200 and IRCyr.C.145 are good examples dating to that time. Dobias-Lalou (Reference Dobias-Lalou2000, 244–46) provides a clear explanation of the origin and meaning of the word ‘ἀπορυτιάζων’, which was rather ambiguous before. In the context of training young future citizens, we have ῥυ to mean ‘to draw, to drag, to pull’ that developed into a number of specialised vocabularies: in archery, ῥυτήρ, ῥύτωρ, ῥῦμα; and in horse-riding ‘to pull a horse’, whence ῥυτήρ ‘rein’, τὰ ῥυτά same meaning, and also ῥυταγωγɛύς ‘leading-rein’. Therefore, the word ‘ἀπορυτιάζων’ represents an officer training either archers or cavalrymen.Footnote 17 Both specialities are indeed found in Ptolemaios’ diagramma, which dates to 320 BC (IGCyr010800) and mentions several public officers, including ‘trainers in archery, horse-riding and fighting in arms’.

The earliest occurrence of ‘ἀπορυτιάζων’ is in an ephebic dedication inscription dating to the beginning of the second century BC (IGCyr015200): Apollonidas son of Damatrios (Ἀπολλωνίδαν Δαματρίω) is listed as the master of riding (ἀπορυτιάζων). This indicates that the cavalry instructor seems to have been a member of the teaching staff, which included the names of four τριακατιάρχαι (leaders of ephebes) and three γυμνασίαρχοι. Additionally, an ephebic instructor was appointed to train the older ephebes (πρɛσβυτέροι) (IGCyr015200; cf. IGCyr103900, IGCyr104000). The inscription IGCyr015200 also listed nine of the dedicators as ephebes, but there were probably more. This suggests that horsemanship was an important part of the training programmes for ephebes during the second and at the beginning of the first centuries BC.

The term ἀπορυτιάζων among staff appointed for training ephebes is also attested in other ephebic inscriptions from Cyrene, dating from the first century AD (IRCyr.C.145, IRCyr.C.701; Abdelhamed Reference Abdelhamed2018a, App, II. E. 3). All of the inscriptions from both Hellenistic and early Roman eras contain the names of three gymnasiarchs supervising the younger and one for the older ephebes (|IGCyr103900, 104000; IRCyr.C.145). They also employ the local term for ephebes (τρικάτιοι), perhaps suggesting the continuation of at least the organisational structures used for equestrian training.

Moreover, in some cases the inscription was embellished with relief sculptures of horses. The most interesting example of this is an ephebic inscription dated to the beginning of the first century AD (IRCyr.C.145; Figure 4). This includes the term ἀπορυτιάζων among the trainer's staff and a list of about 78 ephebic names on a marble stele.

Figure 4. A relief sculpture of a horse's head on the reverse face of a marble panel including an ephebic list from Cyrene. Source: IRCyr.C.145.

As well as the two inscriptions which mention a cavalry instructor, (ἀπορυτιάζων) (IRCyr. C.145, IRCyr C.701), there are other ephebic inscriptions which include iconographic features related to horse riding. The Roman ephebic inscriptions of Cyrene in IRCyr include about 26 inscriptions and graffiti, dateable to between 100 BC and AD 700. Of these, around 11 are decorated with different features of the horse. If we add these items to the inscriptions which specifically mention cavalry training, 13 out of 26 (50%) of the ephebic inscriptions refer to horses. The most significant one is a relief of a horse's head engraved on the reverse face of the marble stele bearing the ephebic list C.145 (see Figure 4). All of this epigraphic data signifies the interest of Cyrenean society in horsemanship. The term ἀπορυτιάζων confirms that the full mastery of the skills of equestrianism was essential to the ephebes in successfully completing the athletic course.

Other reliefs show horses with quadrigae. Ten informal ephebic inscriptions, dated to different times between the first century BC and second century AD, were inscribed on multiple sides of one free-standing monumental base decorated with two different views that included horses. On the front face, a relief sculpture of a four-horse chariot with a driver was found (Figure 5). On the left face of the same block, a figure of a boy leading a horse is depicted (IRCyr.C.76–85). These informal ephebic texts – essentially names of individuals – suggest that they wished to be associated with the image, and that the horse was their preferred logo.

Figure 5. A relief of a four-horse chariot with a driver depicted on one face of an informal ephebic inscription. Source: IRCyr.C.76.

A similar example is a pair of inscribed marble bases embellished with reliefs on all faces of four-horse chariots and a driver (IRCyr.C.123, 124). The names of ephebes were inscribed informally on two faces: above the relief and on the necks of the horses (Figure 6). The scene demonstrates the quadriga in a chariot race as can be understood from the representation of the horses and the charioteer. These examples suggest Cyrenaican pride in their horses. Among the formal ephebic texts, several that survive are incomplete and lack the preamble which is the most important part of the text, because it usually includes the names and roles of the directors of the ephebes; some of these may originally have indicated horse-riding activities. As the names of ephebes were written on these bases in different periods, this highlights the importance of equestrian training in the ephebic programme at Cyrene over time. These inscriptions also show that horsemen had great prestige within Cyrenaican society – both owners of horses and riders.

Figure 6. Marble base with reliefs of drivers in quadrigae on all faces with an informal ephebic inscription. Source: IRCyr.C.124.

There is some epigraphic evidence of verses praising the victories of the horse riders beyond the region. These verses are among the most important indications of the region's high-quality horsemanship. They were written to celebrate two winners of horse-chariot races (GVCyr034). The epigraphic evidence probably dates from the end of the second or the beginning of the first century BC and was discovered some time before 1979, at the sanctuary of Apollo at Cyrene. The content of the verses confirms that the base originally stood in the Hellenistic gymnasium, but was moved to Apollo's sanctuary for re-use at a later date (Dobias-Lalou (Reference Dobias-Lalou2002, 145–49). The first poem highlights the victory of an athlete whose name is Neon, son of Dionysios:

πάντɛσι δ’ ἆρ’ ὀνύχɛσσιν δῶκɛν (granted) οἱ ὠκέσιν (quick) ἵππος

στɛψαμένωι (crowning) τɛλέαν ἅρματι (chariot) καμμονίαν⋅

οὐδέ μιν Ἑρμɛίαο σόφων ἀδαήμονα μύθων

πατρὶς ἐνὶ λιπαροῖς ἔτρɛφɛ γυμνασίοις,

ɛὖ δὲ καὶ Ἡρακλῆϊ μɛμηλότα⋅ τοιγὰρ ἀέθλωι

ἔργα καὶ ἐκ Μουσᾶν ɛἶσα διανύσατο⋅

οὗ σ’ ἵππω, τόσα φαμί, Νέων Καρνηί̈ω ἇδος,

[ɛἰκό]να τυπ[ῶσαι] ὤ̣πασαν Ο̣ὐ̣ρ̣ανίδαι (GVCyr034).

For by means of all their quick hooves, his horses gave him with his chariot the perfect victory with which he crowned himself; Hermes’ wise discourses were not failing in the education given by his home-city in its luxurious gymnasiums, neither was he deprived of Heracles’ concern; he thus accomplished through gymnic competition feats equal to those provided by the Muses. That is why – be it my last word – you, Neon, Karneios’ delight, were granted by the Ouranian gods the modelling of an equestrian image (GVCyr034).

The poem indicates that he won because of the highly skilled trainers at the gymnasia, which were under the care of Hermes and Heracles. The victory appears to have been achieved at a local horse race. The interesting point is that it seems there was more than one gymnasium (γυμνασίοις) in Cyrene, and these were provided with the necessary facilities. Neon was considered as an ideal equestrian model because of his great performance.

The second poem names a competitor who won two chariot races. The text describes the charioteer sailing over the sea, which means that he participated in games outside his home city of Cyrene (Dobias-Lalou (Reference Dobias-Lalou2002, 145–49). However, the most important phrase highlights Cyrene as the place from which those great contestants graduated:

Δ̣ο̣ίας Θɛ̣υ̣χρήστοιο Νέωνα κλɛιτὸν̣ [ὑπ' ὠδᾶς?]|

γράμμα καὶ ἐσσο̣μένοις φθέγγɛται ὧ[δɛ βροτοῖς],

αἰνɛτὸν ἐν Μούσαισι, μɛμηλότα δ’ Ἡρακλῆϊ,

στɛψάμɛνον διδύμας κλῶνα διφρηλασίας

πάππου Ἀριστάρχοιο φɛρώνυμον⋅ ἦ γὰρ ὁ φύσας

υἱɛῖ πατρώιαν τάνδ’ ὀνύμανɛ φάτιν·

ὦ πρὶν ἱαραὶ [.] ɛ[..] ιαι Ἑλλάδος ἁνυσθɛῖσαι

καὶ διὰ κυανέας στέλλɛται αὖθις ἁλός·

οὗ σɛ πάλαι μέγα θάμβος ὄρωρɛν’ δῖα Κυράνα,

ἀθλητᾶν τοίους παῖδας ἀɛξομέναν (GVCyr034).

Through a second poem here the famous Neon son of Theuchrestos is also celebrated through the inscription for the mortals to come: praised amongst the Muses, cared for by Heracles, he crowned himself with the palm of a double chariot race, wearing the name of his grandfather Aristarchos; indeed his father, when naming him, spelled for his son the ancestral fame: ‘Oh, the sacred [---] of Greece once accomplished!’ And [on the spot] he fits himself out for sailing through the dark blue sea. That is why a great amazement has long since arisen towards you, [divine Cyrene], who brings up such sons of athletes (GVCyr034).

Theochrestos, the name of Neon's father, reminds us of the Cyrenean family that included three generations named Theochrestos (Pausanias VI, 12.7). They were all winners, using four-horse chariots, in Greek athletic games during the fourth–third centuries BC. When Pausanias was talking about this family, he praised the Libyan methods of breeding horses in the past. This poem also highlights the ephebes’ equestrian training at the gymnasia of Cyrene.

Horse imagery and the quadriga seem to have been a favoured theme on Cyrene's golden coins in the Classical and Hellenistic periods (Buttrey Reference Buttrey and White1997; Caltabiano Reference Caltabiano, Catani and Marengo1998, 97–112; Robinson Reference Robinson1927, Pls. XIII, XIV, XIX, XX). The quadriga is well represented on coins of the period 375–308 BC (Robinson Reference Robinson1927, 25–33) and was depicted on the obverse of golden staters, while Ammon appeared on the reverse (Figure 7). Horseman/silphium also appeared on the golden drachmas. However, horses were not illustrated on less valuable coins, such as the Attic hemidrachmas and tenths. According to Robinson, 61 Cyrenaican golden coins of this period have been recorded. A horse figure appeared on 22 staters and 10 drachmas. These comprised 52% (32 out of 61) of the total coins of this period (Figure 8). The quadriga was not represented on other artifacts in Cyrenaica, but it was a preferred gift dedicated to gods and people in high positions (see above, Diodorus Siculus, XVII, 49 (2); Pausanias, X, 13.5; X, 15.6).

Figure 7. Golden stater. Obverse: Quadriga driven by Nike. Reverse: Ammon. Late fourth century BC. Source: Cyrenaica – Coin Archives; see also Robinson Reference Robinson1927: Pl.XIV. 1–10.

Figure 8. The percentages of horse representation on 61 coins from Cyrene dating to 375–308 BC.

During the Roman period, Cyrene was perhaps still proud of her equestrians and their great achievements. A poem dated to the second–third centuries AD was written to celebrate the victory of the citizen Markos and his horses (GVCyr036). This poem demonstrates that Markos became famous because of his victories in horse races. Markos was honoured by a poem placed in the temple of Apollo at Cyrene, although the competition is more likely to have been held at Delphi since Markos was crowned with Apollo's laurel:

| ἀμφιθαλῆα κλυτὸν [Μ]ᾶ[ρ]κον | θαλέθοντα ⸢γ⸣ ο[ν]ɛ̣ῦ̣σιν

| Μαρκιανῷ τɛ πατρὶ καὶ γɛινα|μένῃ Κλɛοπάτρηι

| (5) σαῖσιν, Ἄπολλο[ν], [ἐ]γὼ ταῖσδɛ | [ἐ]π̣έ̣γραψα̣ θ̣[ύρα]ις. ❧

| [ˉ ̆] Α [ ˉ ] α τɛ ˉ [Μ]ᾶρκον φίλον, | [ὦ] ἄνα, Ι̣ [ ˉ ± ]

5 | [ˉ ̆̆|ˉ ̆ ] ρ̣ι τɛ̣ὴν [δ]ά̣φνην | (10) [ˉ ̆̆| ˉ ] [ἵ]π̣π̣οις (GVCyr036).

The famous Markos, blossoming for his parents both flourishing, Markianos his father and Kleopatra who gave him birth, I write down his name here by your doors, oh Apollo. [---] my dear Markos, oh lord, [---] [---] the laurel which belongs to you [---] with his horses - - - - - -? (GVCyr036).

Although the poem does not provide a lot of information about the contest, the plural form of the word ‘horses’ (ἵπποις) suggests a quadriga or a synoris (συνωρὶς), a chariot race using two full-grown horses or two foals. This poem can be considered as important evidence of the region's continuing interest in horses and chariot-racing during the Roman period.

The poems which survive in the literary record emphasise the region's great reputation in the four-horse chariot race in both Greek and Roman periods (Abdelhamed Reference Abdelhamed2018a, Appendix. I. D. 3). The Libyan Cratisthenes, the son of the runner Mnaseas, represented Cyrene in the Olympian games in the fifth century BC and won a chariot race, as reported by Pausanias (VI, 18.1). Pausanias (VI, 8.3) tells us also about Eubotas (Εὐβώτας) of Cyrene who won the chariot race and running race in the Olympian games in 408 BC. Cyreneans seem to have been very confident that he would win the competitions as they made a portrait statue for him in advance, according to Pausanias. The writer also reports how Cyrenaican competitors were successful in chariot races during the Hellenistic period (Pausanias VI, 12.7).

This local epigraphic evidence therefore adds two new names of winners in the quadriga from the region to those known from the literary record. Laronde (Reference Laronde1987, 146) listed 15 names of known Cyrenaican athletes who had won a variety of contests; the list includes four victors in a chariot race. Adding to them those two new names (Neon, son of Theuchrestos, and Markos) and that of Berenice II (267 or 266 BC–221 BC), the daughter of Magas of Cyrene mentioned by Callimachus (Fantham Reference Fantham1995, 146), there would be seven names in total. These seven names, in addition to other names mentioned by the literary sources (excluding Neon, son of Dionysios who had won a local contest), make up 56% (10 out of 18) of the total number of Cyrenaican winners of the Greek and Roman games (Table 1). This is a significant indication of Cyrenaican interest in horsemanship during the Classical, Hellenistic and Roman periods, which is not surprising as Cyrenaica is part of North Africa, famous in the Roman period for its successful charioteers. Gaius Appuleius Diocles, the Roman African, is the best example, ‘most outstanding of all drivers’ (omnium agitatorum eminentissimus) (Bell Reference Bell2020, 46–49; Hyland Reference Hyland1990, 205, 206). He started racing from the age of 18 and achieved massive success over the 24 years of his career. The longest honorific inscription of this type was erected for his victories at Rome in 146 AD. This text states that he participated in 4,257 races and won a total of 1,462. Of these successes, 1,064 were in single races (CIL VI.10048). Races included different-sized teams of chariots: two-, three-, four- and even six- or seven-horse teams. When Diocles retired, he was very rich as he had gained more than 35 million sesterces in winnings (Bell Reference Bell2020, 46–49).

The many horse-racing winners from Cyrenaica must have had intensive practice. One question that needs to be asked, however, is whether each city had its own racetrack. In earlier periods this may have been a simple grass track, leaving very little archaeological trace. Gradually, however, it would have become necessary to have a hippodrome built, with provision for spectators, at least from the fifth century onwards, especially if one bears in mind the different documentary references which praise the Cyreneans’ skills in breeding and riding horses (Abdelhamed Reference Abdelhamed2018a, Appendix. I. D. 3; GVCyr034,036; IGCyr134900; IGCyr118600). Unfortunately, because of the lack of excavations and studies, few building remains in Cyrenaica have been identified as horse-racing courses. Wright (Reference Wright1963) refers to a hippodrome at Tocra, though its existence is not yet proven. Similar unexcavated buildings were also reported at Cyrene (Figure 9), Apollonia and Ptolemais (Davesne Reference Davesne1978–1979, 245–54; Humphrey Reference Humphrey1986, 520–23; Kraeling Reference Kraeling1962, 95; Stucchi Reference Stucchi1975, 137, 295–96; Wright Reference Wright1963). Although the exact date of the hippodrome of Cyrene is still uncertain, Dobias-Lalou (Reference Dobias-Lalou2016, 39–61) suggests it probably dates back to the middle of the second century BC. However, Kenrick (Reference Kenrick2013, 255) suggests a date in the Hellenistic period, or before. Dating can be supported by the information mentioned in the honorific inscription celebrating two athletes named Neon (GVCyr034). This text refers to the existence of luxurious gymnasia in Cyrene. As the probable date of this text lies between the end of the second or the beginning of the first century BC, one may expect that the Cyreneans built gymnasia in Cyrene at the beginning of the second century BC, or even before. Also, the occurrence of the term ἀπορυτιάζων ‘cavalry instructor’ in an ephebic inscription dating back to the beginning of the second century BC may suggest the existence of a hippodrome for training the youths (IGCyr015200).

Figure 9. Plan of hippodrome at Cyrene. Source: Google Earth © 2023 Airbus.

It is worth mentioning that the hippodrome of Leptis Magna, a Libyan city located 120 km to the east of Tripoli, is one of the greatest examples in the Mediterranean region. The Leptis circus was elaborately constructed in the first century AD, providing a variety of interesting architectural decorations. Its construction was considered to be comparable to the Circus Maximus at Rome (Humphrey Reference Humphrey1986, 25–55; Humphrey et al. Reference Humphrey, Sear and Vickers1977, 25–115). A mosaic floor from Villa Selene at Leptis Magna, which is located close to this hippodrome, shows a view of a chariot race in a hippodrome dating to the second century AD (Figure 10). This scene could reflect a horse race taking place in the city's circus.Footnote 18 The villa belonged to a rich man so equestrian games were clearly for the entertainment of the wealthy. At Cyrenaica, if the substantial numbers of ephebic inscriptions are taken into consideration, one might expect that future excavations will provide us with better evidence from the remains of hippodromes in the region.

Figure 10. Horse racing at a hippodrome on the mosaic floor of Villa Selene in Leptis Magna. Source: Villa Selene Hippodrome © Ab Langereis https://www.livius.org/pictures/libya/silin-villa-selene/villa-selene-mosaic-of-the-hippodrome-1/ (accessed 7 August 2023).

The word ‘horse’ in the Cyreneans’ onomastic culture

The pride of the people of Cyrene in their horse-breeding, ‘ἱπποτροφί’, can be understood from the common use of the word ‘horse’ ‘ἵππος’ in the personal names dating to both Greek and Roman periods. Christidis (Reference Christidis2007, 687) states that Personal names offer a picture of ancient Greek society, reflecting as they do languages, …, family tradition and relations, the highest professions and …, cultural values…’. Epigraphic local evidence indicates many personal names that include the word ‘horse’ in their construction in both the Greek and Roman periods.

The use of the word ‘ἵππος’ in personal names in Cyrenaica was discussed in a previous paper and a comparison of the numbers of such names found in the epigraphy in this province and others demonstrated how common they were in each region (Abdelhamed Reference Abdelhamed2018b, 103–108). The comparison was based on data from Crete, Cyprus and Cyrenaica from the period between the fifth century BC and the third century AD.Footnote 19 This included ten personal names that consisted of a changeable adjective as a prefix followed by a fixed noun (horse), such as Κάλλιππος (beautiful horse), or composed from a fixed noun (horse) followed by a changeable noun as a suffix, such as Ἱππόνικος (who has winning horses) (Abdelhamed Reference Abdelhamed2018b, 103–108; Dubois Reference Dubois, Hornblower and Matthews2000, 43, 48, 50). The comparison shows that the overwhelming majority of horse-related names from the three areas were in use in Cyrenaica. To indicate how common horse-themed names are in other regions of the Greek world, the use of a group of names will be traced in Thessaly and the Peloponnese, since both regions are part of the Greek mainland, and Thessaly in particular was famous for its well-bred horses.

The wide usage of personal names which consist of the word ‘horse’ in Cyrenaica can be seen in some names listed in the local epigraphic evidence. A list of names from Cyrene dated to 280 BC is a case in point (IGCyr065200). An interesting name constructed from the word ‘horse’ recorded in this evidence is Μɛλάνιππος Τɛλɛσίππω (Melanippus son of Telesippos). This incorporated the word ‘horse’ in the names of both the son and the father, a terminology which continued into the Roman period. Three examples, in which the father and son names included the word ‘horse’, can be seen in one list of ephebes dating to the first century AD (IRCyr.C.145). These are Ἄρχιππος Ἀρχίππω (Archhippos son of Archippos), Κάλλιππος Νɛικίππω (Kallippos son of Neikippos) and Ἀρίστιππος Ἀριστίππω (Aristippos son of Aristippos). Looking to the meaning of the names, Ἄρχιππος and Νɛικίππω may indicate how proud they are to be well skilled in riding horses. Ἄρχιππος is composed of two parts: ἀρχή from the verb ἄρχω’ (I rule, I control, I lead) and ίππος (horse). The name means the horse-ruler or the master of the horse. Regarding Νɛικίππος, it is another version of Νίκιππος, constructed from νίκη (victory, success) and ἳππος (horse). Νίκιππος means the winning horseman or he who wins with his horse(s). The name is very well represented in Cyrenaica; in both versions, see: IGCyr006800, IGCyr009100, IGCyr033100. It is worth mentioning that this name appears ten times in the epigraphy of Cyrenaica, once in that of Macedonia and three times in the data of Thessaly (Fraser and Matthews Reference Fraser and Matthews2018: LGPN, online version). Although both Macedonia and Thessaly were known horse-breeding regions, the name Νίκιππος (winning horseman) was more common in Cyrenaica.

The extensive use of the word ‘horse’ for forming personal names is perhaps evidence that many Greeks in Cyrenaica were horse-owners and horse-breeders. However, some names may reflect noble attributes such as Φίλιππος (horse-loving). Such a name was perhaps also given to children because of the influence of Macedonian names (Philip I–Philip VI). Nevertheless, other personal names, such as Μɛλάνιππος (black horse), may reflect the strong relationship between the people and the horses.

It is perhaps more instructive to contrast this nomenclature in Cyrenaica with that of a Greek mainland area, such as the Peloponnese and Thessaly for the reasons mentioned above (Fraser and Matthews Reference Fraser and Matthews1997).Footnote 20 This includes the personal names formed from two words (one of them being the word ‘horse’ used as a prefix or suffix) in the Peloponnese and Thessaly from the fifth century BC to the first century AD (see Table 2 and Figure 11). However, it is important to note the gap of a decade between Fraser and Matthews’ collections relating to those regions. They published the volume which includes Greek personal names from Cyrenaica in 1987 and the one that includes names from the Peloponnese and Thessaly in 1997. Also, the lack of recent excavations at Cyrenaica is another matter which should be taken into account in this comparison and the larger number of Greek cities in the Peloponnese. Nevertheless, the data analysis in this paper demonstrates that Cyrenaica has yielded a higher number of these compound personal names than the Peloponnese. For Cyrenaica there are 124 names against 107 for the Peloponnese. However, the comparison shows in total an equal number of names coming from the data of Cyrenaica and Thessaly at 124. The name Φίλιππος comprises the lion's share in the listed names from the Peloponnese and Thessaly. This name represents 40 (41%) out of 107 from the Peloponnese and 64 (52%) out of 124 from Thessaly. However, in Cyrenaica, it represents only 28 (23%) out of 124. As has been mentioned above, the name Φίλιππος was perhaps given to children because of the influence of Macedonian names (Philip I–Philip VI) and, therefore, it would be logical to exclude this name from the three lists of the three regions. If so, the largest horse-related number of names represented by the data derived from Cyrenaica comprises 41% of the total number of names (Table 2; Figure 12). Κάλλιππος (beautiful horse) and Ἀρίστιππος (best horse) seem to have been common names in both the Peloponnese and Cyrenaica, though Ἀρίστιππος has a higher number in Cyrenaica.

Table 2. A comparison of Greek personal names formed from two words (one of which is the word ‘horse’) in the Peloponnese and Cyrenaica from the fifth century BC to the first century AD (based on data collected from Fraser and Matthews Reference Fraser and Matthews1987 and Reference Fraser and Matthews1997).

Figure 11. A comparison of the occurrences of horse-related Greek personal names in Peloponnese, Thessaly and Cyrenaica from the fifth century BC to the first century AD (nos. correspond to the names shown in Table 2). Based on data collected from Fraser and Matthews Reference Fraser and Matthews1987 and Reference Fraser and Matthews1997.

Figure 12. A comparison of the total occurrences of horse-related Greek personal names excluding Φίλιππος in Peloponnese, Thessaly and Cyrenaica from the fifth century BC to the first century AD (nos. correspond to the names shown in Figure 11 and Table 2). Based on data collected from Fraser and Matthews Reference Fraser and Matthews1987 and Reference Fraser and Matthews1997.

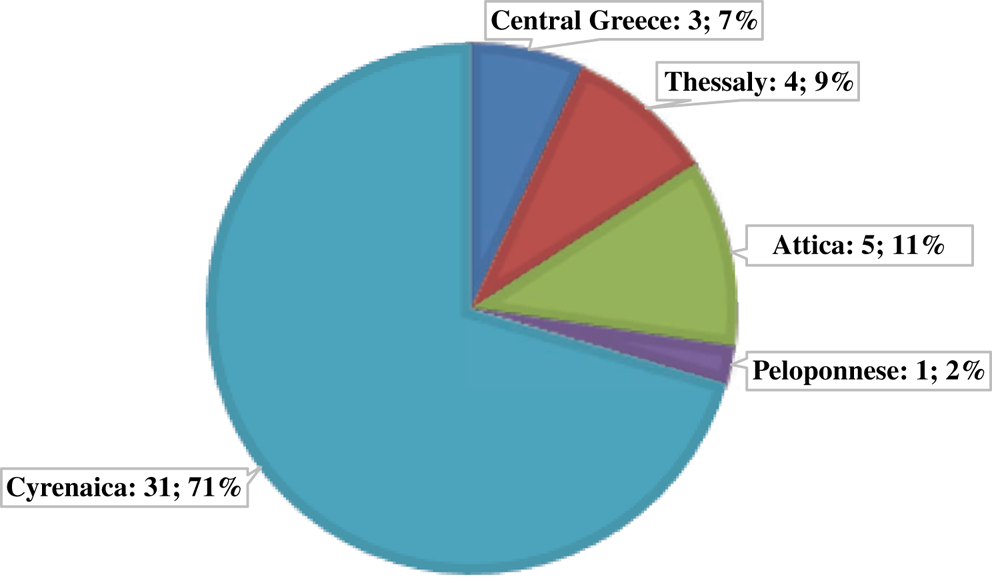

However, the most interesting point is the clear attestation of the name Μɛλάνιππος (black horse) in Cyrenaica (Figure 13). The number of names collected from Cyrenaica is 31, while only one example has been recorded from the Peloponnese. This may reflect that the black horse was widely bred in Cyrenaica, or it may indicate something relating to the good quality of these horses, especially in the Greek and Roman games. This view can be supported by the modest presence of this name in the other regions. For example, there are three names from Central Greece, four from Thessaly and only five from Attica itself, as shown in Figure 13 (see Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Osborne, Byrne and Matthews1994; Fraser and Matthews Reference Fraser and Matthews2000). Overall, the evidence strongly suggests that the use of the name Μɛλάνιππος (black horse) had special importance in Cyrenaica's nomenclature.

Figure 13. The number of occurrences of the personal name Μɛλάνιππος (black horse) found in the epigraphy of five different provinces from the fifth century BC to the first century AD. Based on data collected from Fraser and Matthews Reference Fraser and Matthews1987 and Reference Fraser and Matthews1997.

Comparing the total number of Greek personal names formed from the word ‘horse’ in the Peloponnese, Thessaly and Cyrenaica is quite difficult since there is no list of names in Volume I (Fraser and Matthews Reference Fraser and Matthews1987), which includes Cyrenaica, Cyprus and the Aegean Islands, and Volume IIIA (Fraser and Matthews Reference Fraser and Matthews1997) includes a list of names from the Peloponnese alongside other regions. Also, using the online version of LGPN to compare the names was not possible for the reasons mentioned above (note 10). The name Κάλλιππος (beautiful horse) has been selected to test their percentages among the names starting with kappa ‘κ’ in the Peloponnese and Cyrenaica. This name, in particular, has been selected because there is an equal number (22) of occurrences from the two regions as shown in Table 2 (Fraser and Matthews Reference Fraser and Matthews1987, Reference Fraser and Matthews1997). The total number of names starting with kappa (κ) in the Peloponnese is 1,489; 22 including the word/element ‘horse’ comprise c. 1.5% of the total names. Meanwhile, those from Cyrenaica number 353 names and 22 names associated with the word ‘horse’ represent 6.2%. Obviously, these percentages can provide only an approximate indication of the overall trend, but the results suggest that horse nomenclature may have been four times as common in Cyrenaica as in the Peloponnese.

Conclusion

This paper has examined horse rearing in Cyrenaica and the charioteers’ participation and achievement in the Greek and Roman athletic contests. The literary references provide us with interesting figures about the high quality of their horses and their experience in rearing this animal. This picture is highlighted by both Greek and Roman writers from the fifth century BC to the fourth–fifth centuries AD. Most of the writers never visited the region and some may simply have repeated the descriptions of previous writers, hence the analysis here of epigraphical and archaeological data to test to what extent these indications are true. Studying the history of horses can only be implemented via tracing the relevant linguistic indications and iconographic representations. Local epigraphic evidence, in particular the ephebic inscriptions, confirms the Cyreneans’ investment in breeding and training horses. It also indicates the great reputation of Cyrenaican horses especially in Greek and Roman athletic competitions. The honorific poems from Cyrene dedicated to the winners show how proud they are of the region's distinctive equestrian victories in overseas events. In addition, the assessment of the use of the word ‘horse’ in the region's onomastic culture demonstrates a great connection to this animal. It has been noted that the name, Μɛλάνιππος (black horse) appeared frequently in other regions, but it was very common in Cyrenaica. In short, the ancient literary sources and archaeological evidence together tell us a vivid story about the importance of breeding horses in Cyrenaica during the Classical, Hellenistic and Roman periods.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my deepest gratitude to Professors Charlotte Roueché and Catherine Dobias-Lalou for their continuous support and encouragement. They were always ready to answer my questions related to the inscriptions, especially those published in IGCyr and IRCyr. Many thanks should also go to all the team members of these corpora, who enabled me to enrich my knowledge of the horses of Cyrenaica through the rich epigraphic information lurking within those digital resources. I would also like to extend my thanks to Victoria Leitch and Ahmed Buzaian for their different kinds of support, and to my neighbour, Nicholas Brown, and my son, Kamal Buzaian, for their support and for proofreading parts of this work.