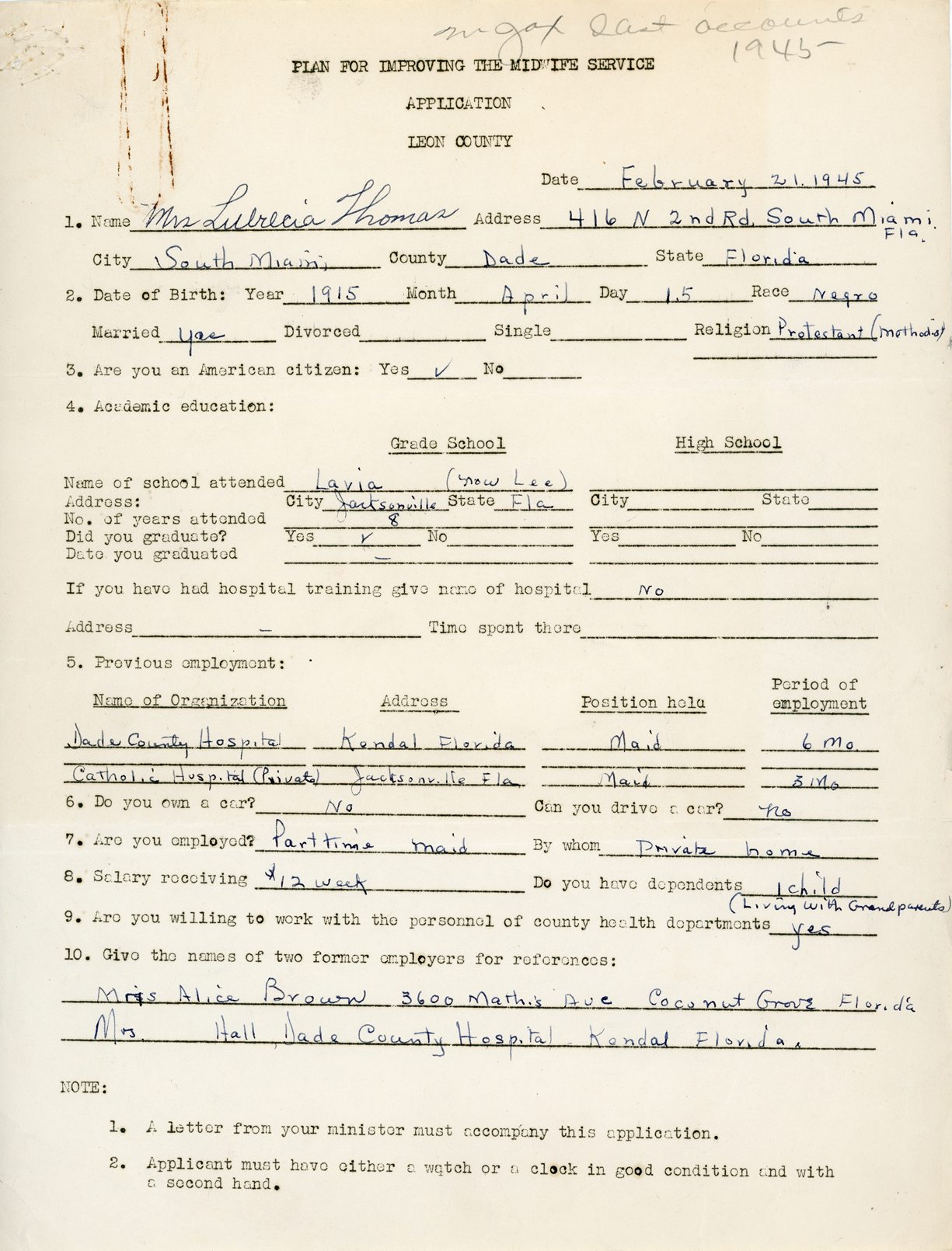

On February 21, 1945, a Black thirty-year-old woman named Lucrecia Thomas sat down with a pen and filled out the application for the Leon County “Plan for Improving the Midwife Service” program in North Florida.Footnote 1 Organized by the Florida Board of Health's Bureau of Maternal and Child Health, the Leon County Health Department, and the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical College (FAMC), the program was an intensive three-month course to license Black women to deliver babies in their local counties.Footnote 2 Living at the time in Dade County, Thomas provided typical information required about her identity in the state application. For the date of birth, Thomas filled in “April 15, 1915.” She wrote “416 2nd Road, South Miami” for her place of residence. For her birthplace, she wrote “Charleston, South Carolina.” She inserted “Black” for her “Race,” checked the “married” box, and made a special note that her one “dependent” lived with grandparents.

Lucrecia Thomas had attended grade school in Jacksonville and had ended her formal education after completing the eighth grade. Successful completion of grade school was one of the requirements for eligibility in the midwife program.Footnote 3 She had previously worked for six months as a maid in Miami's Dade County Hospital and for three months at a local Catholic Church. At the time she filled out her application to the program, she exchanged her labor for twelve dollars a week as a domestic worker for a family. Like Thomas, other applicants were also a part of a larger African American women's working-class contingent in the U.S. South. Marie Louise Patterson of Baker County filled out her application and wrote that she had worked as a “clinic aid” for the local county health department, as a laundress for Camp Blending, and as a housekeeper for Mrs. A. P. Holt. Patterson wrote that her current employer, Mrs. A.P. Holt, paid her seven dollars a week.Footnote 4

Thomas, Patterson, and other applicants presumably received information about the licensure program through their affiliation with local health departments and hospitals. Public nurses of Florida's Bureau of Maternal and Child Health advertised the midwifery program at local county health boards and contacted physicians and nurses and asked them to inform qualified candidates about the course.Footnote 5 As a significant sector of female-led, grassroots, Black health activism in the Jim Crow South, Black lay midwives were part of a broader network of Black women who were gradually aspiring to work in state and professional health care in the World War II period.Footnote 6

Yet what is most interesting to me about the application process was the space that required Thomas to provide her “Religion.” To this end, she wrote “Protestant/Methodist.”

Figure 1. Lucrecia Thomas’ Application, “Plan for Improving the Midwife Service, 1944–1946,” State Board of Health Midwifery File, Florida State Archives.

Thomas was not alone. Other African American women also provided their religious affiliation on the application. These women were predominantly Protestants. Gertrude Brown of Gainesville: Baptist; Mabel Matthias of Perry: African Methodist Episcopal (AME); Mary Frances of Sanford: Baptist. Other applicants for the 1946 cohort, such as Ruby Kimbrough of Jacksonville, wrote “Church of God in Christ”; Ethel Long of Tallahassee, “Primitive Baptist.”Footnote 7 Alongside age, education, address, and work experience, “religion” was apparently an important bureaucratic marker of identification in modern midwifery and more broadly in public health. But this marker of identity was not simply restricted to Old Confederate states below the Mason-Dixon Line: it also included the so-called de facto North, particularly on medical school applications. On April 27, 1942, applicant Winifred Lucille Ellis filled in “Protestant” on her application for the study of “advanced obstetrics” at the Maternity Center Association in New York City.Footnote 8

Thomas and other applicants for the “Plan for Improving the Midwife Service” program had to do more than list their religion in their applications. They also were required to have a religious leader submit a letter of recommendation on their behalf. These religious leaders were predominantly African American male pastors of Protestant churches in Florida. The Reverend W. M. Everett submitted a recommendation letter on Thomas's behalf.

Figure 2. Recommendation letter from the Reverend W. M. Everett. “The Plan for Improving the Midwife Service, State Board of Health Midwifery File,” Florida State Archive.

In his recommendation letter, Everett noted that Thomas was a “believer” and “fine woman,” alluding to her “good and regular standing” in his church.Footnote 9 He suggested that her faithfulness in church work made her “ok” for the midwifery training course in the state's capital.

Other Black male pastors also submitted recommendation letters on behalf of the applicants. Reverend H. Fryer, pastor of the Stewart Memorial AME Church, submitted a letter for Mabel Mathias. Fryer wrote that Mathias was an “obedient member” and “easy to be guided by rules and regulations of this church.”Footnote 10 Everett and Fryer were part of a federal and national phenomenon in which African American religious male leaders were becoming part of the state health apparatus, and recruited into its initiatives aimed at Black people. This historical phenomenon was ignited by the institutionalization of Black health work within the federal bureaucracy in the New Deal and World War II periods.Footnote 11

Why did the Florida and Leon County Boards of Health require Thomas and other applicants to provide their religious affiliation for eligibility to the midwifery program in the aftermath of World War II? What did their religious affiliation have to do with state midwifery and the broader field of modern obstetrics? Why did state and county health boards ask male clergy to submit letters of recommendation on behalf of Black women? How did their comments about their parishioners’ religious orientation align with the standards of state midwifery and obstetrics? Lastly, what did the Board of Health assume about Black women who were not “believers” or not affiliated with a Protestant church community?

In this paper, I argue that the Bureau of Maternal and Child Welfare promoted Protestantism, and African American Protestantism in particular, to determine the moral capacity of Black women to legally practice midwifery in the Depression and World War II periods. The use of religion as a bureaucratic marker of identity, and the enlistment of Black male clergy in the Plan for Improving the Midwife Service application process, together illuminate how the Bureau operated as a parareligious organization that promoted African American Protestantism in its efforts to regulate Black women.Footnote 12 The 1945–1946 Plan for Improving the Midwife Service program was part of the Bureau's religious program that extended back to the Depression period. In the early 1930s, the Bureau began to print religious songs, prayers, and biblical verses in their state midwifery handbooks to authorize modern midwifery as an “honorable calling.” I will show that the religious program of the Bureau was the result of Florida's 1931 Midwife Law that legislated “moral character” as a criterion to determine who was fit to practice midwifery. The state department determined what constituted “moral character” and consequently what differentiated good Black religion from its bad counterpart. Florida presents a case study that demonstrates that Protestantism, and African American Protestantism in particular, was a central component in the state department's strategy to authorize and legitimate obstetrics in Black communities. Yet the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health's focus on the religious and moral fitness of Black midwives impeded any efforts to challenge directly the racial inequality that contributed to the high mortality rates among Black mothers and infants during delivery.

The Plan for Improving the Midwife Service program was part of the Bureau's long fight, extending back to World War I, to regulate midwives in hopes of standardizing reproduction in Black communities. Founded in 1918, Florida's Bureau of Maternal and Child Welfare (formerly called the Bureau of Education and Child Welfare) had joined other health departments in southern states, such as Mississippi, Texas, Georgia, and North Carolina, in a shared effort to address what was called the “midwife crisis” that was considered the main cause of the high death rates among Black women and infants during labor.Footnote 13 A part of the Progressive “maternalist movement,” the Bureau's efforts to regulate Black midwives had accelerated, particularly in Southern states, in the aftermath of the 1921 Promotion of the Welfare and Hygiene of Maternity and Infant Act, otherwise known as the Sheppard-Towner Act, the first “women's bill” and welfare policy in U.S. history.Footnote 14 Affiliated with the U.S. Children's Bureau, Florida's Bureau of Maternal and Child Welfare was composed primarily of nurse-midwives who underwent professional medical training in the Progressive period and who represented what historian Eva Payne called the “maternalist and statist feminist” that sought to police nonwhite women (and children) in protecting American motherhood.Footnote 15 Composed primarily of white female nurses, Florida's Bureau of Maternal and Child Welfare addressed the so-called “midwife crisis,” through the promotion of modern maternal and infant care through clean milk and nitrate eyedrop drives, home inspections, and prenatal and postnatal classes for mothers.Footnote 16 But the “midwife crisis” that purportedly threatened Black women and infants was cast not only as a health and medical problem but also as a religious and moral problem in modern society. Both religion and science worked to define a problem and its solution in reproduction. To this end, this essay reflects my criticisms of the shortcomings of state health policies and programs that shifted focus to the moral behaviors of Black women and not to structures of inequality that threatened the lives of Black mothers and infants. Before detailing the midwife programs in the Bureau of Maternal and Child Welfare in Florida, I first discuss my argument's intervention in the literature on science and state regulation.

Religion, Science, and State Regulation

My essay on religion and midwifery builds on and adds to contemporary scholarship that captures the role of state health departments in regulating reproduction that led to the “gradual destruction of the African American midwife tradition.”Footnote 17 The literature details the ways in which state and local health departments lobbied to legislate punitive laws and promote scientific expertise that excluded Black women from practicing midwifery in the Jim Crow South.Footnote 18 The focus on the state health department is one of the institutions in U.S. history that helped to facilitate “secularizing birthing,” along with the emergence of male obstetricians in the eighteenth century and the formation of the Children's Bureau, and later the hospital movement in the twentieth century. This literature demonstrates how state health departments and private obstetrical networks legitimated secular, scientific reproduction by creating its “superstitious” midwife.Footnote 19 Similar to the existing literature, this essay also underscores how the legitimation of scientific birthing was predicated on delegitimizing the religious cultures of Black women in the American South. The work on “secularizing birthing” provincializes state and scientific power to draw attention to the religious cultures of Black midwives that informed their orientations to reproduction and care.

Yet, the scholarship on state and scientific regulation of Black midwives overlooks how religion was a key component in secularizing reproduction in the United States. The literature about the state's aim to secularize birthing and regulate (and expel) Black lay midwives is often framed as a dilemma between science and religion. Moreover, the story goes that state health departments’ promotion of the power of science and bureaucracy is based on attempts to expel the religious practices of Black women from modern reproduction. In her wonderful ethnography, African American Midwifery in the South, anthropologist Gertrude J. Fraser remarks, “African American midwives had perceived their craft as a gift from God. . . . But by the 1920s, public health officials took on the task of secularizing traditional midwifery that shifted attention to commandments, that were rooted in the power of science and efficient management.”Footnote 20 To Fraser, secularizing traditional midwifery and reproduction was to project knowledge about the natural human body coupled with bureaucratic management (e.g., birth certificates and vital statistical records) that placed reproduction under the authority of physicians and state departments of health. Theologically oriented practices of Black midwives are contrasted to the scientifically oriented health bureaucrat in the story about secularizing traditional midwifery. But what is striking is that Fraser also illustrates how the state health departments adapted Black spirituals into its activities to “drive home the message of hygiene, limitation of practice, and prenatal care to midwives.”Footnote 21 Fraser's illustrations about the religious songs underscore how African American Protestantism was central to the scientific and bureaucratic “commandments” (e.g., lessons, requirements, and protocols) in secularizing traditional midwifery.

Contra to straightforward secularization narratives wherein science replaces religion in scholarship on secular midwifery, this essay argues that state agencies, such as the Bureau of Maternal and Child Welfare, also had (good) religion—God, songs, prayers, creeds, and biblical verses—too. And, more importantly, it shows that the state's religion was part of the process of secularizing midwifery to authorize the power of the state and scientific “truths” in reproduction to Black communities.Footnote 22

Lurking beneath the discussion about state health departments and secularizing traditional midwifery is a story about the rise of the power of science (i.e., biology) in modern medicine. Secularizing traditional midwifery was partly aligned with what cultural anthropologist Hans A. Baer calls the hegemony of biomedicine that presents an atomized, “mechanistic view of the body,” and focuses on “human pathology, or more accurately on physiology, even pathophysiology.”Footnote 23 While nurse-midwives of the maternal and child state and local health departments promoted the power of biology in state and private obstetrics, they did challenge and seek to reform the male-dominated field of obstetrics that viewed reproduction as a pathology. Secularized medicine and public health are often couched as a process in which the authority of natural and empirical biology was contingent on the erasure of religion—primarily meaning an allegedly supernatural worldview. Religious scholar Robert C. Fuller rightly argues that the emergence of secular biomedicine (i.e., “medical orthodoxy”) was not simply the result of “licensing legislation, medical education, advances in biological sciences, and technological innovations,”Footnote 24 but that its emergence was due to the cultural processes that constantly disentangled and distinguished itself from religion (e.g., the conception of disease).Footnote 25 But this disentanglement does not mean that the rise of the biomedical view of disease signaled the expiration or overcoming of religion in modernity. In fact, the secular process of biomedicine was an effort to properly place and determine what is good (and bad) religion in its aims to regulate the bodies and habits of a population.Footnote 26 The Bureau of Maternal and Child Welfare disclosed that midwifery was a strategy of state governance that promoted biomedical reproduction by “legitimatiz[ing] and protect[ing] certain [religious] practices and people while failing to protect—and even criminalizing—others.”Footnote 27

Thus my essay's argument about midwifery affirms recent scholarship in religion that has challenged the secular divide between religion and science in medicine and public health. Scholars have noted not only how religionists—such as Liberal Christians—have steered secular public health campaigns around sex education and global missions, but also how religious and moral codes seeped into state and scientific programs and strategies to fight against health emergencies that affect a particular demographic.Footnote 28 In his After the Wrath of God, religious historian Anthony Petro's discussion of the HIV/AIDS epidemic illuminates how “[state] biomedicine is itself a moral enterprise.”Footnote 29 In the same vein, this essay demonstrates that religion and morality are very much part of the secularization of medicine, particularly in state public health programs in the United States and beyond. The promotion and management of religion and morality are part and parcel of the secularization of reproduction and public health in modern America.

My attention to state midwifery programs in the twentieth century sheds light on the neglected role that Black religion played in the secularization of reproduction and health more broadly. While scholars have documented the antagonistic relationship between Black religionists and the state officials, midwifery also shows how representatives of African American Protestantism and state departments interacted and engaged with each other to achieve different and similar goals. And the state midwifery program is one example where federal and state health bureaucrats promoted good Black Protestantism in the liberal welfare state to confront a specific public health crisis and consequently to “medicalize” Black and low-cash communities in the New Deal and World War II periods. What this essay adds to the recent discussion about religion and state governance in modern liberal society is that Black midwifery temporarily underscored how the possibilities of the state's aim to regulate Black midwives solely depended on their cooperation. Before the total elimination of Black lay midwives in the second half of the twentieth century, the scientific and bureaucratic power of the state department was contingent on the obedience of the laborers that the health bureaucrats sought to regulate. In the end, African American religion was bureaucratized to legitimate secular birthing in the regulation of Black women and communities.

“To Supervise the Delivery Load of Midwives More Closely”: The Plan for Improving the Midwife Service

On August 1, 1945, Lucrecia Thomas and other trainees arrived at Clark Hall on FAMC's campus for the Plan for Improving the Midwife Service program.Footnote 30 Founded in 1887, FAMC was the state's first land-grant academic college for African Americans.Footnote 31 Since the first “Midwife Institute” in 1933, FAMC had been a site the Bureau used regularly to educate, register, and license Black lay midwives.

Figure 3. State Midwife Institute at FAMC in 1935.

The land-grant college provided racially segregated living accommodations for African American trainees. At the time of the licensing program, FAMC also had the only hospital that served Black communities between Pensacola and Jacksonville.Footnote 32 Catering to some Black women and infants in an area of over 350 square miles, the college offered one of the few maternity wards where Lucrecia Thomas and other trainees could learn.Footnote 33 Paying their own way, the trainees came to the campus with their luggage filled with required items for their three-month stay: “four [bed] sheets, two pillow cases, one bed spread, four towels, and four cotton dresses.”Footnote 34 They were the first cohort to participate in the licensure program in the state capital.Footnote 35

The program was short-lived. By May 1946, Ruth Mettinger, Florida's Resident Nurse-Director of the Division of Public Nursing, notified potential applicants that the decision to “dis-continue” the licensure program had been made.Footnote 36 Mettinger also informed applicants about the possibility that African American public state nurse-midwife Ethel Kirkland could visit their homes and offer “close supervision on premature and deliveries.” Before and after the program, state nurse-midwives often traveled to remote areas to inspect and train lay midwives and educate parturient women.

The records do not have exact details on why the state bureau discontinued the program in the spring of 1946.Footnote 37 The time and financial requirements of the program—a three-month residency and travel expenses—would have been almost impossible for most Black working-class women to satisfy because of the multiple and daily demands for their labor. These requirements indicate the extent of racial and economic barriers that hindered many Black women from aspiring to work in professional health care in the American South.

Lucrecia Thomas and other trainees had to spend three months attending lectures and demonstrations. Director of Leon County Health Department Paul Coughlin and Public Health nurse-midwives Miss Margaret Johnson and Miss Lille Mae Chavis together taught a range of courses on topics in modern obstetrics: anatomy, physiology, abnormalities, the midwife setup in the home, and prenatal and postnatal care.Footnote 38 But, similar to the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health's prior home inspections and “Fit for Midwife Certification” classes, the planners of the 1945–1946 program emphasized cleanliness (e.g., personal hygiene and antiseptic tools and techniques) for the trainees who would mostly be delivering babies in private homes in their communities. Many Black families did not have access to hospitals or medical care in North Florida. Other southern state health departments and bureaus also followed suit by prioritizing cleanliness and sanitation in the training of Black women. Besides that, trainees were required to observe five cases and five deliveries in the hospital. To complete the program, they also had to pass oral and written examinations. There was also a “practical” component to the evaluation: trainees reportedly had to deliver approximately twenty babies under the observation and evaluation of a physician or nurse.Footnote 39 On one occasion, Lucrecia Thomas was evaluated by FAMC's Black hospital director, L. H. B. Foote.

The evaluation did not end with the completion of the oral, written, and practical evaluations. Trainees also had to undergo a six-month probationary period under the supervision of a physician affiliated with their local county's health department. For a trainee to obtain a license, the supervisor-physician had to write a satisfactory report that conveyed that trainees were “fit” or capable to be state-certified lay midwives. A Dade County health officer and a physician agreed to supervise and evaluate Lucrecia Thomas. After successfully completing the probationary period, candidates had to sign a pledge that they would properly “notify their county physician-supervisor and/or arrange a hospital emergency visit should abnormalities arrive prior to, during labor, or following labor.” The midwifery certification program required Lucrecia Thomas and other Black females to “cooperate with the County Medical Society, physicians, and the State Board of Health and County Commission.”

In November 1946, Thomas applied for and received her state license to practice midwifery and pledged to cooperate with the state health department. This pledge explained why trainees were required to pass an evaluation test on filling out state birth and death certificates.Footnote 40 Licensed lay midwives like Thomas then became representatives and extensions of state and modern medicine in their local communities. Not only were they expected to implement modern birthing practices in their local communities, they presumably were also tasked with assisting the state health department with further surveilling and supervising all midwives to make sure that all reproductive activities in the community accorded with state laws and obstetrical standards. But these Black lay midwives were representatives of the state medicine in their communities that ironically lacked access to medical care and resources because of entrenched racial segregation and economic inequality in modern health care.

The purpose of the program was to subsume all maternal and infant care under state and medical control. The planners sought to implement their purpose at every stage of the midwifery program. In the summer of 1944, Leon County director and surgeon Paul J. Coughlin sent a rough outline of the program to the director of Maternal and Child Welfare, Lucille J. Marsh, and explained that its purpose was to “supervise the midwife delivery load more closely.”Footnote 41 His desire to enhance state supervision was ignited by his assertion that “[t]he total of [Black] midwife delivery load for the last two years has averaged about 480, approximately 45% of all deliveries in [Leon] county, [alone].”Footnote 42 In the 1940 Florida Health Notes, Marsh reported that, since 1940, approximately 80 percent of all nonwhite births were attended by a midwife, compared with 13 percent of white births. Both Coughlin and Mathias used statistics to shed light on the delivery load that the professional medical community and national government considered a distinctly racial, class, and regional problem in the early- to mid-twentieth century. Contemporary historian Susan Smith noted that Black lay midwives were delivering over 50 percent of Black babies throughout the South before the numbers started to decline in the 1950s.Footnote 43 The licensing process was designed to supervise the midwives and consequently to authorize professional physicians and other care workers to take the lead in all matters pertaining to reproduction in Black communities.

Yet the Florida Health Department's efforts to modernize reproduction by subsuming it under obstetrical and hospital care was in fact a broader federal government policy initiative in the New Deal and World War II periods. Following the lead of the Children's Bureau, the federal government had started to intervene in the health of mothers and babies with the 1921 Sheppard-Towner Act. The New Deal administration had extended the 1921 Sheppard-Towner Act by legislating the 1935 Social Security Act (i.e., articles V and VI) that provided states with nearly $15 million annually of federal funds to encourage married pregnant mothers or mothers of infants to consult a physician, receive prenatal and postnatal care, and deliver in hospitals.Footnote 44 These federal efforts were strengthened during World War II. Following the lead of the Children's Bureau, Red Cross, and Veterans of Foreign Affairs, in 1943 Congress legislated the Emergency Maternal and Infant Care (EMIC) Act to provide federal funds to cover the obstetrical and hospital care for mothers and infants of servicemen in the “four lowest pay grades.”Footnote 45 The emergency welfare act was designed not only to boost the morale of soldiers but also to usher America's nuclear family into the habit of accessing modern reproductive care. Director of the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health Lucille J. Marsh gladly reported that Florida's EMIC had already assisted more than 1,500 mothers and infants in 1944.Footnote 46 The EMIC was one example of how the New Deal's social security insurance was legislated to strengthen and preserve the predominantly white, nuclear, middle-class family—meaning the domestic and childrearing mother and breadwinning father.Footnote 47 Toward the end of the program, the 79th Congress in 1946 legislated the Hospital Survey and Construction Act, otherwise known as the Hill-Burton Act, to strengthen the hospital movement. Race and gender structured welfare and health policies (i.e., social insurance) that were under the jurisdiction of Jim Crow state legislation.

Paul Coughlin and other state health planners understood the midwifery program to be continuing the state health department's efforts to address the relative high mortality rates among African Americans in Florida. Lucille J. Marsh reported that the year 1944 had the lowest rates of maternal deaths in state history. By the 1940s, the national rates of maternal and infant mortality were gradually declining in the United States. Despite the decline in mortality among Florida Black mothers in particular, Marsh noted that maternal mortality among Black mothers was “still too high” in comparison with their white counterparts.Footnote 48 In her 1945 Forty-Sixth Annual Report on the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health, Marsh reported that, of 2,167 infant deaths, 1,356 were of Black infants, so a rate approximately 63 percent higher than their white counterparts.Footnote 49 By the time of the 1945–1946 midwife program, Black maternal and infant mortality had become a federal and national concern. In 1940, Time magazine featured an article on “Negro Health,” and reported that Black maternal and infant death rates were over 60 percent higher than their white counterparts.Footnote 50 The article identified Black maternal and infant mortality as “America's Number 1 public health problem.”Footnote 51

The Florida planners spoke of the disproportionate rates of Black maternal and infant mortality within the framework of the “midwife problem.” Untrained Black lay midwives bore the brunt of the blame for the relatively high rates of mortality because of what the state and professional health community considered to be their uncleanness, ignorance, and immorality. Professional and state health care workers viewed lay midwives as engaged in reproductive practices outside of proper obstetrics and biomedicine. They deemed Black lay midwives to be responsible for the health crises in their local communities, specifically causing toxemia (i.e., preeclampsia) among Black mothers and premature births among their infants. Thus the “midwife problem” captured the personal and behavioral deficit model in public health that largely blamed Black people for their enduring health problems. At times, the “midwife problem” minimized the roles of policy makers, private physicians, and community leaders in contributing to the mortality and morbidity rates among Black people. Yet public nurse-midwives who understood the racist roots of Black morbidity and mortality were powerless in the face of the state legislators’ propensity to favor privatized medicine and endorse racial segregation in Jim Crow Florida.Footnote 52 The midwifery courses and programs that I noted at the beginning of this paper also highlighted the overall constraints of health and social reform that mainly concentrated on trying to change Black people's behaviors while the systemic racial and structural inequality continued without challenge or protest.Footnote 53 Moreover, the causes underlying the health disparities of Black mothers and infants were not addressed. For example, state and professional health care representatives and organizations did not attend to the racial violence inflicted on Black southern women's bodies that shaped their experiences and memories of what was “modern” in medical gynecology and obstetrics in their lived history.Footnote 54

Ultimately, the Bureau organized courses and programs to eliminate all lay midwives from involvement in reproductive care. Florida Health bureaucrats yearned for the day when there would be enough trained professional nurses and physicians so that there would no longer be any need for lay midwives and their services.Footnote 55 Yet the shortage of medical personnel and resources made their elimination impractical. In the 1920s, former director of Florida's Bureau of Child Welfare and Public Nursing Laurie Reid noted that the limited health personnel and resources among Black and lower-class communities made Black lay midwives a “necessary evil.”Footnote 56 In 1944, the same year in which the planners began organizing the midwifery courses, Lucille Marsh also referenced the shortage in her report in light of the enlistment of physicians and nurses in the service of soldiers and families in World War II. Moreover, the shortage of health personnel underscored the Florida Department of Health's dependence on lay midwives to fulfill its mission in modernizing reproductive care in Black communities.

Although the planners could not eliminate all lay midwives, they focused on removing from modern reproductive care what they referred to as the “old granny” midwife. On August 4, 1944, Paul Coughlin told Marsh that the aim that the midwifery program was to eliminate the “old granny.” This sentiment was echoed by another planner, state public nurse consultant Ruth Mettinger, who told a representative of the Atlanta Children's Bureau that the program sought “[t]o eliminate the old granny midwife and that [she], Dr. Marsh [and] Dr. Coughlin worked out a program for younger negro women with eighth grade education, graduate preferably, interested in this particular type of work.”Footnote 57 The planners understood that the old grannies (i.e., elderly women) were typically the ones who selected and trained their successors in reproductive care in local communities. Both Coughlin and Marsh used a metonym that had been familiar in state and professional obstetrics and reproduction. The elimination of the old granny had been a long-time mission of the Bureau. In the 1930s, public nurse-midwife Jule O. Graves and others had organized retirement receptions at which nurse and lay midwives would gather to celebrate the service of the old granny midwife. In addition to receiving a monetary “gift,” the granny midwife received a certificate noting her “honorable discharge” that she was required to sign after vowing not to practice midwifery in the community. According to Graves, these ceremonies were organized so as not to hurt the feelings of the granny midwife.Footnote 58

The 1945–1946 program sought to eliminate the granny under the 1931 Midwife Law. Not only did the law require lay midwives to have a state license to practice, it also authorized state and local health departments to establish criteria for license eligibility. Moreover, the planners sought to weed out the old granny midwives by establishing age, educational, and health requirements of eligibility for participation in the 1945–1946 program. Applicants had to be between the ages of twenty-five and forty, have completed the eighth grade or equivalent, and be literate. Applicants were also required to pass a physical exam that conveyed that they had relatively good eyesight, hearing, and lung capacity, and were not infected with hookworm or syphilis. These bureaucratic requirements were institutionalized to determine who was qualified to be a state lay midwife.

But what is particularly interesting to me is that the 1931 law went further: under section 3c, the 1931 law also stated that the midwife had to “present evidence satisfactory to the State Health Officer of good moral character.”Footnote 59 The legislation of “moral character” provided the conditions for the significance of religion in regulating midwifery and eliminating the old granny. Religion was used as a bureaucratic mechanism by which to determine the “moral character” of lay midwives and to eliminate the old granny who supposedly had improper (or no) religious practices and immoral traits. Moreover, the state bureaucratized Protestantism to determine who was morally fit to be a Black lay midwife. Before discussing the uses of African American Protestantism in Florida state midwifery and broader American state health, I first turn my attention to how religion was configured as “good” or “bad” to question the moral capacity of Black elderly women and the broader lay midwife tradition in Black life in the South. Thus the use of the old granny helps to make sense of the 1931 Midwife Law that bureaucratized Protestantism in the 1945–1946 program to supervise Black women and communities by evaluating their religious and moral character. The religion of the granny was configured as a threat to the state and to the livelihoods of Black (and poor white) communities.

Protestantism, Immorality, and the “Old Granny” in State Midwifery

Leon County Health Department director Paul Coughlin and Ruth Mettinger used the “granny” label to justify surveilling and managing Black lay midwives. Old age here determined medical unfitness, said the state in effect. The training and licensing of younger midwives was a battle waged by the health department to wrest authority in reproduction from elder Black midwives to younger state and professional health care workers. And yet Coughlin and other planners implicitly acknowledged the authority of the old granny in Black communities. During the planning stages, Coughlin even recommended that the planners incorporate old grannies into the program by “coaxing them into thinking that they are helping to train the new ones.”Footnote 60 He further noted that the old granny would still “retain their cases and receive fees,” although it was clear that it would be the trainees who would actually be doing the bulk of the work. On a practical level, the granny midwives (and their trainees) were easily accessible and affordable for Black and lower-class communities in remote counties and areas. And many granny midwives had already won the trust of their local communities. Furthermore, the granny lay midwife had already expanded the public's perception of what they did, well beyond “catching babies,” to include also domestic and labor duties of the household for bed-ridden mothers and their families.

The old granny roles highlighted a significant historical and religious dynamic in midwifery and the broader Black doctoring tradition.Footnote 61 The granny label underscored how Black midwifery was never devoid of religion in Black history.Footnote 62 The authority of the granny midwife was religious in nature. The grannies were understood to have spiritual power that enabled them to heal and care for infants and mothers in and outside of their communities.Footnote 63 Theirs was a religious vocation. In 1938, Alabama lay midwife Lula Russeau told the Works Progress Administration interviewer that the fact that she was born with the caul (amniotic sac) covering her face signified to her family and community that she possessed the spiritual gift to be a midwife. The “caul” was one of the spiritual signs that signaled that she was born and called by God.Footnote 64 The religious aspects of Black lay midwifery also captured the theological underpinnings of birthing. In deliberate contrast to modern obstetrics, the granny midwife understood birthing as a divinely natural process that did not require specialized human and technological intervention (e.g., forceps, anesthesia, and surgery). They did not interpret the birthing experience as a pathological condition. Instead, the granny midwives viewed themselves as vessels through whom the Divine worked to “catch babies” and care for mothers. In a co-written autobiography on Alabama lay midwifery, Margaret Charles Smith and Linda Janet Holmes noted that Smith and other Black lay midwives anchored their delivery practices in religion and spiritual discourse: “putting God ahead,” “taking the Lord into their insides,” “having some kind of feeling knowing they are always blessed,” “not working with nothing unless God is in it,” and “much communication with the spirit.”Footnote 65 The religious orientation of some granny lay midwives fueled their expansive view of care for mothers and families in their communities.Footnote 66 Reproduction was an important material locus to understand the unique religion of Black women in history.Footnote 67 Black southern midwives were part of a larger history where bondswomen took some control of their bodies, sociality, and ritualistic practices in reproduction in the face of racial violence, exploitation, and objectification that extended back to the colonial and antebellum periods.Footnote 68

Florida's Paul Coughlin and the planners did not use granny to acknowledge their spiritual power and systems of care for mothers, infants, and families who were neglected by state government and medical communities. They relied on its usage in the Florida State Board of Health. From the standpoint of state and professional health care practitioners, the “granny” served as a racial metonym to delegitimate the skill of Black laywomen in reproductive care. Thus state and professional medical practitioners used the label to identify the premodern forms of reproduction that they considered superstitious in nature. The category of “superstition” was a state and medical marker to separate professional and granny lay midwives, as well as good and bad religion.

But modern obstetricians and public nurses also used the superstition category to mark the religious and moral difference between them and granny midwives. The label demonstrates how biomedicine depended on religious and moral frameworks to achieve and demarcate its own legitimacy and authority. The label helps to shed light on the religious aspects of the 1931 midwife law that questioned the moral capacity of the granny midwife, for it marked Black women as improperly religious (or irreligious) and consequently immoral. Coughlin, Ruth Duran, and other planners did not expound on their use of the superstition undergirding the granny label. But frankly they did not have to because it was a part of the state and medical nomenclature of the Florida and other state health boards at the turn of the century. Indeed, in his address at the 1912 American Public Health Association conference, Jacksonville's municipal Health Officer, C. E. Terry, used the label to identify the unscientific and hence superstitious nature of the Black granny midwife.Footnote 69 Terry alluded to the granny's “worthless concoctions.” But he also used references to superstition to highlight such women's immoral character who, he said, were “devoid of responsibility and honesty of purpose, with their worthless concoctions.”Footnote 70 He further alleged that the granny lay midwife was a charlatan who deliberately “play[ed] on the superstitions of their race” for monetary gain, and who manipulated the ignorance of her race and dissuaded her patients from “calling a physician.” He referred to these “worthless concoctions” to classify their unscientific knowledge and techniques (e.g., putting a “knife or sharp objects under the bed to prevent sharp pain”) and their so-called bad religious practices. Terry's comments unearth how the health state evaluated what constituted good and bad religion, by what religious scholar Charles McCrary notes as the sincerity and veracity test of beliefs.Footnote 71 With their “worthless concoctions,” the state health department rendered the religion of granny midwives “bad” because of their so-called immorally insincere and fraudulent beliefs that were intentionally used to manipulate their so-called naïve patients for material gain. By Terry's logics, the granny midwife lacked religious and moral character because she knew her superstitious concoctions were worthless and ineffective.Footnote 72 The granny label was used to classify fraud and evil character and captured how the public health departments used religion to racialize Black women.

Planners of the 1945–1946 midwifery program were concerned about the money granny midwives made from their services. Their allegedly questionable moral character was presumably why Ruth Mettinger recommended creating and circulating a “survey among the granny midwives in Leon County and among the patients whose children they delivered to determine the amount paid to the grannies for delivery and the number of women delivered who actually pay the fee.”Footnote 73 The religious and moral underpinnings of the superstition category in the granny label was circulated nationally in state-sponsored modern reproduction. For instance, Mississippi's director of the Board of Health, Flex J. Underwood, noted that Black granny midwives specifically and lay “midwives [more broadly] were not far removed from the jungles of Africa, laden with its atmosphere of weird superstition and voodoo.”Footnote 74 What the granny label disclosed was that religion and race combined to classify and delegitimate Black women in state midwifery. The label demarcated certain religious orientations of Black women as immoral, unscientific, and consequently as a dangerous threat to the life of Black and lower-class communities. Furthermore, the label underscored how secular management of the religion of Black women was a state and scientific matter.Footnote 75

In light of the 1931 law, the so-called immoral character of the granny midwife underscored that they were not properly religious and consequently immoral. The law set the criterion of moral character that bureaucratized Protestantism to weed out the immoral and irreligious character of Black women—particularly the granny midwife. The Florida Board of Health privileged a specific form of modern Protestantism as a mode of fostering the appropriate character traits that purportedly enabled Black women to be state-sponsored midwives and care for mothers and infants. The granny label showed the ways in which modern Protestantism contributed to the racialization of Black women to mark them as morally unfit for midwifery.

Good Black Protestantism and Medical Statecraft in Florida Midwifery Programs

Protestantism had already been incorporated into state midwifery activities and programs prior to the Plan for Improving the Midwife Service program. Florida public health nurse-midwives, such as progressive Jule O. Graves, deliberately adopted religious expressive culture to elevate midwifery into a moral practice. This was a way to legitimate state and professional obstetrical standards through law and programs. What is interesting about the use of Protestantism in the state midwifery programs was its progressive-liberal framework that emphasized moral character deemed suitable for those who engaged in secular medicine and that, by extension, earned its authority.Footnote 76 Their emphasis on moral character promoted a version of good religion that oriented midwives to acknowledge the power of state-sponsored scientific reproduction. Following the passing of the 1931 Midwife Law, Graves wrote state midwifery handbooks that were geared toward the predominantly Black lay midwives, incorporating biblical verses, creeds, prayers, and songs to reflect and imply the moral stakes of reproductive work. For instance, in the 1945 state midwifery handbook, the first page contained Exodus 1, a biblical story of Shiprah and Puah and their decision to follow God and reject Pharaoh's decree. The biblical narrative was designed to illustrate that midwifery was an “honorable calling.”

Figure 4. A Manual for Midwives (Jacksonville: Florida State Board of Health, 1945). “Plan for Improving the Midwife Service,” FSA.

In the 1936 State Midwife Handbook, lay midwives would have found the “Midwife Creed” and the “Midwife Prayer.”

Figure 5. “The Midwives’ Creed” and “The Midwives’ Prayer,” E. Bryant Woods, Midwife Manual (Jacksonville: Florida State Board of Health, 1936).

Christianity in Florida's midwifery pamphlet actually reflected a broader phenomenon of federal bureaus and organizations incorporating religion in health welfare policies and programs around birthing and parenting (i.e., motherhood) in the World War II period. The 1940 White House Conference entitled “Children in Democracy” was the first meeting of its kind that emphasized the significant role of religion in child birthing and rearing.Footnote 77 Yet, unlike the Florida midwifery program, the White House meeting subscribed to a form of religious ecumenism. The conference associated religion—specifically Christianity and Judaism—with morally cultivating children in particular and the nation more broadly to manufacture public morale during war. Other religious traditions were not mentioned in relation to childcare and rearing at the conference. On January 18, the first lecture and group discussion on religion was led by Baltimore's Har Sinai Congregation's Rabbi Edward L. Israel on the subject “Religion and Children in Democracy.”Footnote 78 In a 1940 radio address, Franklin D. Roosevelt expressed his concern about children “who were outside the reach of religious influences and denied help in attaining faith in an ordered universe and in the Fatherhood of God.”Footnote 79 However, Jule O. Graves and Florida public nurse-midwives did not include other religious traditions outside of Christianity in their work among lay midwives in North Florida.

African American Protestantism also held a prominent place in Florida's midwifery programs and literature. Prioritizing the behavioral model of public health reform, public nurse-midwives appealed to Black vernacular religious practices to legitimate modern obstetrics and biomedicine. For instance, the state midwifery handbooks deliberately included gospel hymns popular among Black Protestant churches. The lyrics of the hymns were often revised to promote state and obstetrical authority and standards. For example, the 1936 handbook featured a song, “Midwife Indeed,” based on the tune, “Since Jesus Came Into My Heart” with lyrics about modern health.Footnote 80 Such print practices were not confined to Florida state midwifery. Mississippi's Midwife Manual also included Black vernacular religious cultural expressions to try to regulate Black midwives. It featured a Black lay midwife on the front cover and illustrations of Black women inside, along with gospel songs and prayers. The Georgia State Board of Health did so too, well into the 1950s. In the 1953 midwife documentary entitled, All My Babies: A Midwife's Own Story, sponsored by the Georgia State Board, the musical director, Louis Applebaum, selected the popular spiritual “Good News” to promote modern birthing practices through the religious practices of the main character, lay midwife Mary Cooley, an African American Pentecostal.Footnote 81

Black Protestant culture was incorporated in other state and private health programs and initiatives in the United States. Beyond midwifery, state and private health organizations such as the Public Health Services and the Committee on Tuberculosis among Negroes employed Black Protestant music from African American concert choirs, such as the William Dawson and Tuskegee choirs, to promote their educational programs on syphilis and tuberculosis.Footnote 82 State health bureaucrats often used these cultural practices with their understanding of what they took to be the religious nature of Black people in the American South. For instance, Jule O. Graves explained that Black lay midwives formed voluntary clubs and organized their meetings like a religious service. Held in local churches, the midwifery meetings included prayer, singing, and testimony. For Graves, these voluntary clubs both reflected and capitalized on what she described as the “intensely religious” orientation of Black midwives.Footnote 83 Lucrecia Thomas and other candidates mentioned earlier were thus participating in a state midwife program in which Black Protestantism was already a bureaucratized and a central aspect of the state health apparatus aimed at Black communities.

The 1945–1946 midwifery program also drew on the authority of African American Protestantism by asking Black male clergy to participate in the training and licensing of Black lay midwives. We saw earlier that Black male clergy were asked to “vouch for the moral character” of the female applicants. This was part of a larger national trend as well. In the 1930s and 1940s, Black male clergy were gradually becoming brokers by serving as meditators between the Black communities and state health departments to fulfill the health and social needs of the former. Black male clergy were thus in essence becoming part of the state health apparatus amid the institutionalization of Black health work in federal bureaucracy in this period.Footnote 84 The U.S. Public Health Service's Office of Negro Health Work also often recruited educated and professional Black Protestant ministers to participate in National Negro Health Week, for example to preach sermons to promote modern understanding of infectious diseases and cures for “Health Sunday.”Footnote 85 For instance, during Negro Health Week in April of 1939, in Washington, DC, Reverend F. Rivers Barnwell, Director of Health Education Among Negroes in Texas Tuberculosis Association, preached a sermon based on Matthew 7:12 that emphasized the church's role in teaching Black people how to live under the laws of modern health and sanitation as Moses did for Israel. Footnote 86 In 1942, the Florida State Board of Health also started soliciting Black clergy to champion its programs aimed at addressing Black health, specifically tuberculosis and syphilis. Often educated and middle-class, Black ministers were incorporated into a limited moral and behavioral model of state health that sought to convert Black communities to modern medicine. In his 1942 editorial, “The Minister, the Church, and Health Education,” Tampa's AME pastor W. F. Foster noted that “we [Black ministers] feel that the church is a definite channel through which attitudes and objectives toward major problems in health should be developed and carried into the home.” He further explained that he and his colleagues were “interested in cooperating with the program as outlined by the Bureau of Health Education.”Footnote 87 Public health officials relied on the ministers to instill trust and faith in modern medicine and health practices among their congregants and the broader community. Ministers partnered with the state health department and its bureaus to fight for improving the health of their congregants and broader community. From the angle of state health bureaucrats, the ministers helped their crusade to legitimate and authorize modern medicine among Black communities.

In the Plan for Improving the Midwife Service program, Black clergymen were representatives of what the state considered modern African American Protestantism. Since the eighteenth century, modern obstetrics was partly based on the rise of the male physician in the birthing experiences amid the broader hospital movement that gained traction in the United States in the 1940s and 1950s.Footnote 88 But the insertion of African American male clergy into this hospital movement and health practices more broadly underscored how morality was a significant aspect of modern reproduction practices and mores. The recommendation letters from Black male clergy highlighted what the state health practitioners considered to be good African American Protestantism, which state health bureaucrats perceived as cultivating the specific moral character traits they deemed necessary for state licensing. The words in the recommendation letters illuminate what Florida Board of Health considered good Black religion in state-sponsored midwifery. Not only did the board exclude other orientations outside of Protestantism, but its promotion of good Protestantism was definitely based on the idea of a church led by a male leader. African American pastors used terms such as honest, dependable, industrious, and kind in their description of the female applicants. Reverend D. E. White submitted a recommendation letter on behalf of Gertrude Brown, whom he had known for twenty years. White noted that he “found [Brown] to be honest and reliable.”Footnote 89 Pastor M. M. Lindsey noted that Ethel McClary was “honest, energetic, diligent, and industrious.”Footnote 90 Other Protestant male pastors acknowledged the candidates’ “dependability, trust, and friendly disposition.” Whether Brown, McClary, and other applicants actually exemplified these character traits is of secondary importance. What matters primarily is that secular state officials and medical professionals legitimated these specific character traits and used them to determine who was morally fit to practice midwifery. These character traits exhibited in Black Protestant churches revealed that Black women selected for the program had the moral capacity to adhere to state health protocol and consequently to defer to physicians and nurses in reproductive care. The fight for state public health for Black women and infants was thus based on a Protestant male gaze that vouched for the moral character traits of Black women, traits that the state considered an appropriate benchmark for their capacity to train as a midwife and to obey state regulations around women's and infants’ health. This benchmark was based on the attempt to erase exclusively local forms of Black Protestant and other spiritual practices that these state bureaucrats considered inadequate for reproductive care. Yet the planners knew that there were no guarantees that the trainees would adhere to state-sponsored midwifery or that they would completely abandon local knowledges and techniques of the Black lay midwifery tradition. Twentieth-century Alabama midwife Margaret Smith noted that she simultaneously adhered to state midwifery protocols and at the same time never abandoned the methods and techniques of reproductive care she had learned from her mentor, Ella Anderson, a “granny midwife.” Before the second half of the twentieth century, the Florida health state was limited in completely regulating Black women and their religious cultures.

Conclusion

Florida's Plan for Improving the Midwife Service gives a glimpse into the historical significance of religion, and Black Protestantism in particular, in state health initiatives and programs. Black Protestantism was a significant mechanism in modern obstetrics and state health. The 1945–1946 midwife program relied on male African American religious leaders vetting candidates on behalf of the state to ensure that candidates were morally fit and could be expected to be obedient and acquiesce to the state's intentions around midwifery and female reproduction. Yet how the state administered this single program also underscores the limits of the moral behavioral model, for it blamed Black people for their health plight, and not policymakers, private physicians, and other leaders involved in the systemic evils of Jim Crow governance. Moreover, the program unveiled the interactions, partnerships, and engagement between African American Protestants and state government. Surely, the training of Black midwifery highlighted the racial implications of the “Protestant-secular” that exposed the relationship between church and state in liberal democracy.Footnote 91

By such means, the planners of the program obscured the communal networks and structures of care already in place in local Black communities in the American South. In fact, the planners depended on the very communal networks and structures in Black communities that they denigrated. Black lay midwives were significant figures in the communal networks and structures of care, serving Black mothers and infants whom the dispensers of modern medicine largely neglected, exploited, and abused in the larger U.S. history. Black lay midwives willingly mediated between modern health organizations and Black communities by shouldering the responsibilities and workload of the limited welfare states during Jim Crow. Religion was a significant part of these networks and structures of care in the broader female-led Black health activism in the twentieth century. Black religion was a central part of the local health activism. Moreover, midwives already had the religious and moral frameworks that animated their birth practices. They also already knew that midwifery was an honorable calling before state programs strategically began to enlist and incorporate Protestantism. To be sure, many lay midwives were frustrated by the state-sponsored reproductive programs and laws.Footnote 92 But the example of Florida nurse-midwife Jule O. Graves attests to the ways in which lay midwives willingly participated in the state programs and consequently elevated midwifery for the sake of Black mothers and infants.Footnote 93 Local networks of care provided care for the well-being of Black mothers and infants and consequently challenged racial death and inequality in modern medicine.