Introduction

Two couples, political activists from Argentina, board a plane in Madrid with 12 small children. The children are all around the same age, the oldest barely four, and they do not resemble each other much. The year is 1979, March or April. Spain is at the height of its democratisation process. One of the couples, Cristina Pfluger and Héctor ‘Pancho’ Dragoevich, seems tense. The children are obviously not all theirs and they fear they will be questioned. But they are also excited. They are going to Cuba to do their bit in the struggle against the military regime that has ruled Argentina since 1976. Their mission is to care for the children of fellow militants who are returning home to take part in an armed operation in a bid to topple the dictatorship.Footnote 1

These children in the care of adults other than their parents were participants in a political mission that was also a mission of love. It was orchestrated by the Montoneros, an Argentine guerrilla group that was being viciously persecuted by state forces. In the 1970s, and especially following the 1976 coup d’état, these state forces kidnapped, tortured and disappeared thousands of political dissidents and militants, dealing a brutal blow to both armed and unarmed opposition. In 1978, Montonero leaders had established themselves outside the country. But encouraged by a resurgence of labour protests and increasingly harsh economic conditions back home, which seemed to foreshadow social unrest despite the regime's crackdown on all forms of opposition, they launched a ‘counteroffensive’ plan, calling on all militants who had managed to escape the savage persecution in Argentina to return to the country to fight.

As many of the guerrillas who responded to the call had small children, it was arranged that these children would be taken temporarily to a childcare centre (a guardería or nursery) set up for them in Cuba. In the five years it operated (1979–83), which extended beyond the counteroffensive actions of 1979 and 1980, some 50 children passed through the nursery, where they were cared for by their parents’ fellow militants.Footnote 2 Most children were under six when they arrived, some as young as toddlers.

From the start, the counteroffensive was deeply controversial, even causing a major rift within the Montoneros. When it eventually failed, leaving nearly one hundred militants disappeared, it sparked heated discussions beyond the organisation and the Left.Footnote 3 Leaders were criticised for their top-down decision-making, their militarism and their reckless disregard for rank-and-file lives. They countered arguing that fighting the dictatorship was imperative.Footnote 4 Years later, two books and a documentary revisited these debates, but they also prompted an empathetic discussion on what the children experienced.Footnote 5 In 2021, military officers involved in crushing the counteroffensive were found guilty of crimes against humanity in a trial brought by the victims’ relatives, including some who had been in the nursery as children.Footnote 6

Despite the importance of the counteroffensive, there are not many studies on it. In one of the few, Hernán Confino analyses political and military strategy aspects, shedding light on how exiled militants were driven to heed their leaders’ call to return by feelings of defeat and survivor's guilt after the brutal repression that decimated their ranks. But he does not touch on what the operation meant for couples and children and the motivations behind the nursery.Footnote 7 Studies on the nursery itself focus on the construction of memory and representations of life there.Footnote 8 I take a different angle, exploring the political significance that affections and familial love had for one such organisation (the Montoneros) by looking at couple and parent–child relationships among exiled members and exploring these relationships in connection with the group's political strategy and the Cuban government's diplomatic and child-refugee policies.

This article provides an original approach to thinking more generally about political violence in Latin America during the Cold War, in what was ironically – given the description of this period as ‘cold’ – a heated scenario, due to the widespread bloody conflicts that characterised the region, fuelled by the rivalry between the Soviet bloc and the United States and its allies. First, I underscore the importance of the relationship between love and politics and how the two converge, positing that their intertwining is shaped by both the experiences and political practices of the individuals involved and the strategies and decisions of their political organisations, with their ideological, cultural and political constructs. I thus contribute to new studies on affections and emotions that view both dimensions – love and politics – as embodied experiences and, therefore, interconnected.Footnote 9 Second, I take the perspective of the history of children as a powerful lens for understanding history. Unlike studies that victimise children or assess the impact of conflicts on childhood, I view them here as active subjects, while recognising that, as with any other subject, their capacity for agency is conditioned by the power relations in which they are immersed and their ability to influence such relations, which is, of course, in turn connected with their age.Footnote 10 As active subjects, children offer, through their stories, an invaluable gateway for gaining historical insight.Footnote 11

My reconstruction uses complementary primary sources. These include interviews conducted with present-day adults who stayed at the nursery as children, and militants who had been entrusted with the children's care and were adults at the time, including the Cuban agent who headed Cuba's Americas Department, a government body that coordinated relations with left-wing organisations across Latin America. Additional sources include the archive of the Memoria Abierta organisation (containing over 700 interviews with political and social activists) and first-hand accounts featured in books and films or given as testimony in the counteroffensive trial.Footnote 12 I draw on these fully aware that they rely heavily on personal memory, but understanding that this does not invalidate them as sources that tell the protagonists’ stories. I thus focus on the practices these accounts reveal, and the political and cultural constructs underlying them, which take on meaning through certain discourses, images and teachings. To visualise this dynamic, I contextualised these first-hand accounts and collated them, paying attention to significant details, transcending mere specifics to use them as clues – in the sense suggested by Carlo Ginzburg – into a deeper, and in this case tragic, history.Footnote 13

Violence and the Intolerable

In the early 1970s, Argentina was in political turmoil. The armed forces had been an ongoing presence in politics since the overthrow of Juan Domingo Perón 15 years earlier and the banning of his movement, the country's leading political force. Constant military interference undermined the credibility of any elected government, so that rebellion came to be seen as a legitimate option in the eyes of certain sectors of society. Student and labour protests became increasingly frequent and intense as the influence of the Cuban Revolution grew. This accompanied a growing radicalisation among young people, who, like their peers in other parts of the world, were challenging the establishment.

This unrest spawned a number of revolutionary organisations in Argentina. One of the most important, the Montoneros, was born in 1970 as a radical youth offshoot of Peronism, the heterogeneous political movement united under the leadership of Perón. This group played a decisive role in combatting successive military governments in the first years of the 1970s. In particular, it was instrumental in the efforts to bring Perón back to Argentina and also helped secure the Peronist movement's participation and resounding victory in the 1973 elections, which had been convened by the armed forces in the hope of undermining popular support for revolutionary organisations. The elections, however, did little to curb radicalisation, and as Argentine society became increasingly polarised, so did the Peronist movement. Despite the crucial support received from the left of the movement, following his return, Perón leaned on its right-wing sectors, which would later favour and even participate in the 1976 coup.Footnote 14

In this context of acute social unrest and political conflict, any opposition to the government, whether armed or unarmed, was brutally repressed. In line with the doctrine of national security, the state identified political activists as the ‘enemy within’ that threatened Western Christian society and had to be wiped out. It thus set out to persecute, torture and kill that enemy, characterised as ‘subversive’.Footnote 15 While Argentina's left-wing organisations were aware well before the 1976 coup that state forces were torturing and murdering opponents, it was only over time that it became evident that there was a systematic plan to annihilate militants and that enforced disappearance was the primary means to carry it out. This heinous method was chosen by perpetrators because it allowed them to erase all traces of their crime, including the victims’ bodies, and it was precisely that characteristic that prevented targeted sectors from initially realising such a plan was unfolding.Footnote 16

While that realisation was hard, it was even harder for government opponents, including Montonero militants, to believe children themselves could be targeted. It was not just a matter of being confronted with facts, as it required crossing a mental threshold that would make such violence conceivable. It was not that Montonero militants and other left-wing activists did not believe children could be in danger. In 1973, for example, the Montonero newspaper had written about police and far-right brutality and how it affected poor children, citing the case of a small girl allegedly snatched from her working-class home. While the abduction proved unfounded, the report reveals the Montoneros had begun to consider it plausible that children could be victims of such violence.Footnote 17 By 1975, as knowledge of the existence of clandestine detention centres spread and it started to become clear that disappearances were not isolated events, political activists began to realise that their relatives could also be at risk. Some months later, in an operation that targeted Roberto Santucho, a top leader of the Ejército Revolucionario del Pueblo (People's Revolutionary Army, ERP, another major guerrilla group active at the time), his children were abducted along with their cousins and another child. They were held illegally for days in a clandestine detention centre, but were eventually set free and fled the country. The older children were given asylum in the Cuban Embassy, while the youngest – an infant – was taken directly to Cuba by a couple entrusted with his care.Footnote 18 Still, this alarming incident did not immediately lead militants to recognise that their children could be systematically subjected to such violence. Their full awareness was the result of a process and it only came later.

Nonetheless, during those months, fear pervaded the day-to-day life of militants with renewed intensity. As revolutionary organisations stepped up their efforts to internationally denounce Argentina's human-rights violations, renowned intellectual and poet Juan Gelman (a leading Montonero engaged in such efforts) came up with the idea of setting up a nursery in Cuba to care for the militants’ children. He feared the dangers faced by Montonero members could result in numerous orphans. According to Juan Carlos Volnovich, an Argentine psychoanalyst living in Havana who would later provide counselling for the nursery's children, Gelman told him that based on reliable information an estimated 400 to 500 children of Montonero militants could become ‘war orphans’. He asked Volnovich if he thought Cuba would agree to host a facility for these potential orphans.Footnote 19

Gelman's concern for children at risk of being orphaned reflected an imaginary shaped by the Second World War, still vivid in people's minds globally and strongly associated with the suffering of children through family loss. This is no minor detail. As the Montonero newspaper's editor-in-chief, Gelman had certainly read the articles published there (probably written by journalist Rodolfo Walsh), which denounced how police and right-wing violence affected working-class children, yet he could not conceive of – or was perhaps unable to articulate in his mind – the possibility that repressive violence could befall the youngest and that they could be victims of kidnapping.

By the time plans for the counteroffensive began in 1978, this perception had changed as awareness of the threat faced by children grew. Sometime earlier, in 1977, the mothers of disappeared militants who had come together in their search for their sons and daughters, forming the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo, found that many among them were also looking for their grandchildren. They thus joined forces and established the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo organisation, launching a specific search for those babies and infants snatched by government forces along with their mothers or born in captivity.Footnote 20 Therefore, the realisation that a repression capable of extreme cruelty – involving kidnapping, torture and disappearance – could target children required a radical mentality shift among militants and entailed the terrifying acknowledgement that the organisation was unprepared to counter that threat.

In hindsight, the conversation between Gelman and Volnovich seems almost prophetic. Through the efforts of the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, it has since been established that during this period (known as Argentina's Dirty War) repressive forces abducted some 500 babies (including Gelman's own granddaughter). The vast majority of these babies were born in captivity to militant women who were pregnant when they were abducted and were disappeared after giving birth. Instead of returning the babies to their families, they were placed with their parents’ captors or their associates and registered under false identities.Footnote 21

Baby-snatching and other such practices were not a Cold War invention. But, while children may have been treated as spoils of war throughout history, by the twentieth century the glorification of childhood as that which is held most dear by humanity had made violence against children ‘intolerable’, in Didier Fassin's terms.Footnote 22 After the Second World War, this view had gained traction, giving way to the United Nations’ adoption of the Declaration of the Rights of the Child in 1959, following a process of advocacy and strengthening of children's rights, grounded precisely on the keen awareness of the suffering children had experienced during that conflict.Footnote 23

In the Argentina of the 1970s, this view was part of the ethos of the Left (both armed and non-armed). That explains why for these revolutionary groups orphanhood was the worst imaginable fate for their children. It was only slowly, through bits of information, at times conflicting, that the awareness that babies and children could be the intended victims set in, forcing militants to acknowledge they were up against an enemy that had crossed a moral line. This raised new dilemmas, as it exposed the monstrous nature of the state's counterinsurgency repression. The fact that the Argentine state treated its opponents’ children as spoils of war, snatching them from their mothers whom they then disappeared, clearly sets the regime apart from the revolutionary forces it combatted. Stealing the left-wing opponents’ babies and placing them with families loyal to the armed forces served the dual purpose of harming the babies and their families and eradicating their worldview by preventing familial transmission of their culture and values. Such targeting of children by the dictatorial regime also invalidates what is known as the ‘theory of the two demons’, according to which the violence perpetrated by the Argentine armed forces during the period of state terrorism is comparable to the acts of violence committed by guerrilla groups such as the Montoneros (depicting them both as demons). This argument has been used by many in Argentina to equate the violence on both sides and relativise the human-rights abuses of the dictatorship.Footnote 24

In 1978, when the idea for a nursery was first raised by Gelman, the greatest fear may have been orphaned children, and that was certainly the motivation for making provisions for childcare so combatants could return to Argentina for the counteroffensive actions. But as more cases of missing babies emerged, the Montoneros had to face the fact that the dictatorship had gone beyond the acceptable in what were believed to be universal values and beliefs.

Couples and Partners

The nursery also emerged as a need because both men and women were actively involved in the organisation. The mothers were just as much potential participants in the planned counteroffensive as the fathers were. Although crucial, this element has not been considered in previous studies on the counteroffensive and the nursery.Footnote 25 This involvement of both men and women entailed radically bridging the personal and political divide, a distinction created under bourgeois culture. Globally, during the so-called ‘long sixties’ that separation was challenged by feminist demands for individual autonomy and the right to decide over one's body and identity. But in left-wing movements the politicisation of personal life was not framed in that context and legitimising process. Rather, revolutionary organisations are generally perceived in opposition to the anti-establishment movement that questioned prevailing moral and family values and as exercising a discipline over their members that negated them as individuals.Footnote 26

However, this assessment is not entirely accurate. Leftist militants were predominantly very young and alongside their revolutionary activities they were exploring romantic and sexual relationships. They had intense love lives, furtive affairs, one-night passions, and short but often indelible liaisons. Although there were some long-lasting relationships, stable unions sanctioned through marriage and other formalities were often disrupted by government persecution and the need to go underground. Even in such trying circumstances, militants were no strangers to the discussions about couples and sexuality that were stirring young people around the world, as I have examined at length in other works.Footnote 27 But in the Left, these stirrings took on specific forms, giving way to a complex intertwining of emotional and political commitments that was absent from the global counterculture of the 1960s. Sara Ahmed argues that love is crucial for understanding how individuals align themselves with collectives and how it becomes part of their connection to a group, securing that connection. In the revolutionary ethos that affective bond was part of a transference relationship with no pre-established target, fusing together sexual love, romantic/familial love and political love.Footnote 28 The word compañero (partner) expressed that fusion: it was the term used by militants to refer to those who embraced the same political cause, but also to their romantic partners.Footnote 29 That merging of self-fulfilment, romantic love and revolutionary struggle was eloquently expressed in an early poem by Uruguayan writer Mario Benedetti: ‘If I love you, it is because you are my love, my partner, my everything, and in the street, shoulder to shoulder, we are more than just two.’Footnote 30 Countless couples saw themselves reflected in these lines and when they were disappeared – as many were – their meaning was conveyed to their children by relatives.Footnote 31

This overlapping of love and politics caused some conflicts. The traditional nuclear family (based on the indissolubility of marriage, biological kinship and the gendered roles of breadwinner husband and homemaker wife) was part of the structures the revolutionaries sought to change, and, as such, it was an area of contention. The specific direction such transformations would take was not predefined. Disputes involved almost all orders of life and, in particular, different ways of understanding the place of love and commitment, although the value of heterosexuality was never contested.Footnote 32

While for militants the political meaning of relationships and family and their experiences were guided by revolutionary ideals and shaped by conscious choices, they were also impacted by the course history was taking and the weight that the association between family, nation and social order had in the policies and discourses of the ruling military. The whirlwind of political events and the risks they faced daily, including the possibility of dying or being forced to resort to violence, placed militants in extreme situations, lending new meaning and urgency to their amorous relationships. These became more fluid and passionate, but often also short-lived and with abrupt break-ups. Moreover, life underground and in exile rendered privacy difficult for couples, so whatever intimacy they had was all the more intense. While Montonero leaders tried to control these experiences through collective discussions, disciplinary measures and even the imposition of codes of conduct, their efforts only revealed the unrestrained nature of their members’ sexual and romantic experimentations and the absurdity of any attempts to rein them in. As repression intensified, these efforts to control sexual relationships were stepped up, even as escalating violence made the emotional support from romantic partners, friends and family even more vital. In these extreme circumstances, disagreements within couples were also exacerbated.Footnote 33 These difficulties could bring couples closer together, but also tear them apart.

Political bonds were imagined as blood ties that connected fellow militants in their common will to sacrifice their lives for the cause, making them all part of a political family. Fellow combatants were considered brothers and sisters, forming a family by political decision, affective choice and shared lives. It was also not unusual for political ties to overlap with actual blood relations. Decisions and experiences were made and shaped in this multiple intertwining of affections and politics. While the counteroffensive plan rested on a political assessment, it was driven by the militants’ emotional state, as Confino shows. Recruitment efforts played on their feelings of defeat, their guilt for having survived when fellow militants had not, their distress over the breakdown of everyday life and the prospects for the future, and their nostalgia for the country they had left behind.Footnote 34 Recognising the intertwining of the affective and the political is crucial for understanding that emotional backdrop. Many militants were summoned to participate as a couple, they discussed the decision together and, in some cases, felt pressures that had to do with their relationship as a couple. There is no information that can elucidate whether the organisation made a conscious decision to recruit and appeal to couples as such, but it is a logical conclusion, given how couples were seen as a space that was essentially part of the political structure and how both partners participated, together or individually, in the organisation. In some situations, one of the partners – often the man – was expected to answer to the organisation for their partner.

The participation of women in the Montonero counteroffensive contrasted with a similar plan organised around the same time by Chile's Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria (Revolutionary Left Movement, MIR) known as ‘Operación Retorno’, which involved exiled members slipping back into the country to carry out guerrilla actions against the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship. In the MIR operation women appear to have been included only after, and in response to, feminist demands, while Argentina's armed organisations in general had by then naturalised women's participation in high-risk actions.Footnote 35 Many women were, nonetheless, still relegated with respect to their male partners in terms of the political responsibility assigned to them, and in most cases women continued to bear the brunt of household and childcare duties. But with the organisation's ranks much thinned in 1979, recruiting couples for the counteroffensive meant doubling the number of exiled militants that could potentially return to fight in Argentina. Moreover, if it was possible to call on couples, it was because the revolutionary couple combined their political and personal lives to the point of taking for granted that the decision to join the counteroffensive involved them both, regardless of who actually returned to Argentina to fight. This is not to say couples did not argue over the decision. According to Edgardo Binstock, the decision to return from exile and participate in the counteroffensive could spark strong disagreements between partners, even leading to separation. This is evidenced by the letters of Ricardo Zuker and Marta Libenson, a couple exiled in Spain, who ultimately went back to fight and were disappeared.Footnote 36 Theirs is a specific case that mirrored that of many other militant couples faced with the decision to respond to the counteroffensive call.

For these couples, bringing children into the world was a difficult decision. According to revolutionary ideals, children were the reason these militants fought for a better world. The new generations would also be in charge of furthering the revolution in the future. As Daniel Viglietti, a politically committed Uruguayan singer-songwriter, declared in a popular song written in Buenos Aires in 1971, ‘the new dawn needs children’.Footnote 37 As with other revolutionary groups, children were the link connecting the affective and political legacies of the Montoneros. Thus, while many were intentionally conceived, those who were the result of unplanned pregnancies were equally welcomed as the expression of that communion. Numerous examples illustrate this. Mónica Pinus – who was one of the nursery caregivers, along with her husband Edgardo Binstock – believed that children were part of ‘a life project’. That is how she explained to her obstetrician her decision to have a baby. In 1980, Pinus was kidnapped in Brazil and disappeared, but almost 40 years later, when testifying in court, her partner echoed the idea that ‘having children meant continuing to bet on life’.Footnote 38 While this view of children as the future of the revolution was held by all militants, the decision was ultimately personal and there were many militants who postponed having children. Among the women who did become mothers, many avoided taking greater risks after giving birth.Footnote 39

All these different situations notwithstanding, the number of militant couples with children who decided to join the counteroffensive was large enough to warrant making provisions for their care. Many militants disobeyed their leaders’ orders and brought their children back with them to Argentina. Others who could not bear to be separated from them found another way to do their bit. That was the case with Pfluger and Dragoevich, one of the couples accompanying the group of children on that plane from Madrid to Cuba in 1979. They were exiled in Sweden and engaged in denouncing the human-rights abuses in Argentina when a fellow militant approached them about joining the counteroffensive. They discussed the possibility as a couple. Pfluger recalls how they wanted to return but were reluctant to leave their children. So they were invited to contribute as caregivers in the nursery. Due to logistics, they could not have their own children with them while training for this assignment, and that separation enabled them to empathise with how difficult it would be for fellow parents to leave their children behind with others.Footnote 40

The idea for a nursery was also in line with the express wish of many militants that, if something were to happen to them, their children would be cared for by comrades – their political family – thus guaranteeing that they would be raised according to their parents’ identity and values. This was not exclusive to the Left, as in the 1960s collective childcare among like-minded peers, rather than by blood relatives, was common in the counterculture movement around the world.Footnote 41

In short, couples, and couples with children, played a decisive role in the counteroffensive. Key to understanding the experience is recognising that both militants and the organisation were sustained by that intertwining of political, romantic and familial relationships, and that the boundaries between these were blurred, although never fully erased. Straddling those different dimensions caused profound and devastating conflicts and pain for individuals, couples and the group, opening wounds that can still be felt today.

Inside/Outside in the Cold War

Launching the counteroffensive and establishing the nursery in Cuba involved crossing geographical borders. Borders were crucial spaces in the counterinsurgency efforts conducted through continental and international alliances. These allied repressive conservative forces deployed an anti-subversive rhetoric based on the figure of the ‘enemy within’, which was used as an argument to banish those considered ‘subversives’.Footnote 42 This figure of an enemy who threatened Western society served to materialise the dividing lines that separated capitalism from socialism. And it had concrete implications, as it made crossing national borders and meeting the legal requirements for residing in a foreign country extremely difficult. For the children of militants, this meant living under transient and provisional conditions, as their parents moved from country to country, following the dictates of their political commitments and their organisation and eluding persecution by allied counterinsurgency forces that operated across the continent.

Leaving Argentina, the possibility of returning, and, especially, entering Cuba involved going through immigration controls. Like other Latin American left-wing organisations, the Montoneros had developed resources and skills to elude these, including forging passports – crucial elements in the global efforts by governments to identify individuals. But this did not guarantee militants would be any less vulnerable when crossing borders. In 1978, at just ten years old, Mariana Chaves crossed from Argentina to Brazil, fleeing persecution with her parents, in what was the first of many times. She recalls waiting in line at baggage check and seeing an officer slashing open another passenger's large stuffed animal – a seemingly minor but nonetheless powerful symbolic violence that stayed with her. Even after several years underground, there was nothing more frightening for her than waiting in line for immigration control and baggage check. She felt completely vulnerable and feared for her parents.Footnote 43 Her experience gives us a glimpse of how fear of repression and security measures operated on intergenerational relationships and led children to feel their parents’ vulnerability.

At the same time, the region's repressive forces operated outside legal frameworks, beyond their national jurisdictions. In this sense, ‘territoriality’ as a criterion for the jurisdiction of sovereign states, with their rights and obligations, as defined by Seyla Benhabib, was challenged by the international alliance that operated covertly and in violation of international law, with repressive agents crossing national borders to persecute and eliminate those perceived as subversives.Footnote 44 As militants were in danger even outside Argentina, the leaders turned to Cuba as a safe haven.Footnote 45 They believed there was no better country than the ‘socialist homeland’ to care for their children, the most valuable asset of the revolutionary project. In this context, the children's care gained new political significance. While in the past there had been daily individual efforts to protect and support their children, with the counteroffensive in the works the Montoneros devised a specific strategy that included creating a facility for them. Both women and men were engaged as carers, because the idea was for children to be looked after by couples in a family setting. At the same time, it entailed a shift in childcare duties, as these no longer fell exclusively on women.

The choice of Cuba to host the nursery was also significant because of the space Cuba's revolutionary government had carved out for itself in the confrontation between socialism and capitalism. It had put itself at the centre of the ‘heated scenario’ of the Cold War, furthering alliances and strategies in places like Africa and promoting Third Worldism, often in tension with the aims pursued by its socialist-bloc allies.Footnote 46 The Caribbean island became a crucial political and subjective space for Latin American insurgents and for resistance against the region's dictatorships. It offered refuge to militants who, once there, forged strong political and affective ties with Cuba, creating a transnational community spawned by internationalist solidarity efforts but cemented by bonds formed in the everyday. In line with Benhabib, we could say its members were brought together by shared political and ideological affiliations that transcended national borders.

Refugee children in Cuba embodied – like no other group – that transnational political community and identity. The sanctuary given to these children expressed, concretely and symbolically, the network of ties and solidarity that existed between Cuba and Third World revolutionary organisations. Cuba's support for liberation movements across Latin America and Africa included a policy aimed specifically at protecting their militants’ children. As part of that effort, youth summer camps (colonias de verano) were set up for the many refugee children who were brought to the island from around the world.Footnote 47

These spaces thus contributed to consolidate a transnational left-wing identity that did not entail a loss of national identity and partisan loyalties. Individuals can have different identities that give meaning to their subjective experiences according to the various dimensions of their lives. Children, in particular, can easily accommodate these different identities. For reasons that had to do with the relationship between Cuba and the Montoneros (as explained below), Montonero children did not participate in the collective everyday activities organised for other exiled children from the Southern Cone, but they were nonetheless influenced by the Latin American and internationalist identity furthered by Cuba, as their own experience intersected with their socialisation in local schools and life and with the political culture of their parents’ organisation. Chaves, for example, participated in the Varadero Pioneers International Camp representing Argentina, and today she remembers being awed by the sense of belonging she found there, a combination of national, Latin American and internationalist sentiments. These children's ability to seamlessly fuse those different identities did not, however, mean they did not experience deep ruptures – from school, friends, crushes – that left a painful mark, as Chaves explains.Footnote 48

Underlying the Montonero children's care were Cuba's complex ties with the Argentine exile community. Following the 1976 coup, Cuba did not sever diplomatic relations with Argentina, due to both economic and political reasons. Among the former was the fact that Argentina was the Soviet Union's leading wheat supplier, and among the latter was Cuba's desire to hold on to the few diplomatic relations it had in Latin America, after being expelled from the Organization of American States in 1962.Footnote 49 The Argentine dictatorship thus had an embassy in Havana, a circumstance that did not sit well with many exiled revolutionaries from that country. They felt they enjoyed less solidarity from Cuban authorities as compared to other Southern Cone exiles. The fact that the Montonero office in Havana operated as an informal embassy and that Fidel Castro himself even visited it occasionally did nothing to appease them.Footnote 50

These tensions were offset by the Montonero children, who catalysed Cuba's internationalist solidarity. Cuba furthered its internationalist aspirations through its solidarity efforts, associating such efforts with the feelings evoked by children. As Martha Nussbaum argues, every political principle and the forces that uphold it require some kind of emotional support to survive.Footnote 51 Children lent the revolutionary project that support – emotionally and affectively as well as concretely. The Montonero children received an avalanche of attention, no doubt also facilitated by the funds the organisation deposited in Cuba's coffers.Footnote 52 In contrast to other children, such as those from African nations, who were apparently sent to youth summer camps or boarding schools, the Montoneros chose to set up a separate house for their children. And Cuba accepted. The first group of children arrived from Madrid in 1979, followed by a second group from Mexico some weeks later. There were initially eight or ten children, who would be joined by others who came to Cuba or were there already with their parents. Subsequently, new children were often being brought in as others left. The caregivers also changed. In 1980, when the first counteroffensive operation was defeated and the second one was underway, Susana Brardinelli – whose partner Armando Croatto, a former congressman and Montonero labour leader, had been murdered in September 1979 – was put in charge of the nursery children, including her own, Virginia and Diego. She was assisted by Estela Cereseto, who had been imprisoned until recently in Argentina.Footnote 53

The nursery merited special attention from Cuba because of the political importance it had for the Montoneros and for Cuba's strategy of solidarity with Third World leftist movements. This is reflected in how the children were received. They were welcomed by two top Cuban officials: Saúl Novoa, a member of Castro's private guard (known as the Special Troops), and Jesús Cruz, who was in charge of relations with the continent's armed organisations through his position in the Americas Department. Cruz had worked alongside Argentine revolutionary Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara in the Ministry of the Economy; headed missions to France and Argentina, where he succeeded in establishing diplomatic relations; and eventually became the officer who handled Argentine affairs. His duties included ensuring the children's safety, acting as political liaison, and facilitating logistics.Footnote 54

Because the presence of Montonero militants on the island could cause a diplomatic crisis with Argentina if the dictatorial government were to object to Cuba harbouring them, the identity of both Montonero children and adults was a source of political tension. It was also an issue for the children on a personal level. Being in a socialist country did not eliminate the risks faced by revolutionaries, as Argentina's repressive forces could still get to them, and this was not lost on the children. While the rules that had governed their clandestine lives in Argentina and elsewhere were not as strictly enforced in Cuba, they still needed to be careful and take certain security precautions. Living under a socialist government may have made them feel more protected, but the truth was that Argentina's intelligence services were, in fact, watching them, as there are references to the nursery in their reports.Footnote 55

Many Argentine children and adults thus entered Cuba with Uruguayan papers and the children were enrolled in school as Uruguayans. Besides their caregivers, only Montonero leaders and Cuban authorities knew the children's true identities. At home they were called by their first name or a nickname. Cuban officials even suggested that, for security reasons, the nursery children should refrain from bringing schoolmates or neighbourhood friends home. To compensate, they arranged outings and group activities with their own children.Footnote 56

Many of the children were too young to remember the strict security of their past lives. But, while for some of the older ones – such as Diego, who had spent much of his childhood in hiding – the more relaxed environment could be daunting after years underground, most of them would later recall how they revelled in it. They could openly express how proud they were of their parents and their history, collectively sharing their experiences with Argentine peers and Cuban children. The younger children sometimes forgot even the more lenient rules they now had to observe and would disclose their nationality and sing the Montonero anthem in public, believing it to be Argentina's national anthem (a confusion that reveals the complete symbiosis between national and political identities).

As they grew older, and especially after teenagers arrived in 1982, the rules were enforced even less vigorously and were more frequently ignored. Chaves recalls how, at 14, she came and went as she pleased. She invited friends over and roamed Havana freely, feeling she could be herself. This created some conflict within the nursery, forcing the adults to yield. The rules, however, were reinstated when it came time to leave the island. As in earlier departures, they were forbidden to take anything with them that contained identifying information (letters, photographs, diaries, keepsakes from friends or sweethearts). Nonetheless, Mariana and her brother always managed to take something with them, because, as she put it, ‘we had a clandestine life within our clandestine life’. In short, the children circumvented the rules, thus showing the possibility they had of countering the authority of the adults and the organisation itself.Footnote 57

Their integration into Cuban everyday life brought about another tension in connection with their national and political identity. As one of the carers at the nursery now recalls, ‘we didn't want to become a ghetto’.Footnote 58 The children thus went to school and to groups organised for the little ones (known as ‘circles’) with other Cuban children, where they learned about socialism and revolutionary heroes. Having fought in the Cuban Revolution, Che Guevara embodied the bond between Cuba and Argentina and allowed the children to see their parents as continuing his legacy. Many everyday activities served to forge a transnational identity among the children, one that was internationalist, Latin American and revolutionary, but which coexisted with a strong sense of belonging to their Argentine homeland. It was the adults who found that multiplicity of identities conflicting, and it triggered concerns over the children's feelings for their mother country and their parents’ political movement.

These fears led the adults to focus more firmly on conveying the Argentine and Montonero identity to their children. Thus, the children absorbed their heritage in their daily life and the adults raised them according to their shared values and ethos. Argentine culture was present in the parties they celebrated, the meals they ate, the sweets they enjoyed and the games they played.Footnote 59 Today those who stayed at the nursery as children recall very vividly the Argentine children's stories and songs they heard there, particularly those by María Elena Walsh, an Argentine writer and musician beloved by many generations.Footnote 60 This cultural transmission was accompanied by deliberate political and patriotic teachings. The Argentine flag was raised every day and there was a map of the country hanging on a wall. The children learned about historical events and the feats of national heroes. This was combined with the Peronist and Montonero identity. José de San Martín, the hero of Argentina's national independence, was a key link between the country's history and the revolution. Paradoxically, to foster a sense of national belonging in them, the children received mainstream magazines published in Argentina, such as the children's monthly Billiken, known for expressing the government's military ideology.Footnote 61 These were delivered with other items through the Montonero contact in Mexico or came directly from Argentina in the Cuban diplomatic pouch, in what Cruz called ‘Operation Nostalgia’. In this way, Cuba's diplomatic relations with the dictatorship were, ironically, used for the emotional wellbeing and patriotic education of Montonero children.Footnote 62

Care and Pain

The adult carers, concerned with the children's welfare, faced an impossible dilemma: their decision to fight against a force capable of intolerable cruelty exposed the children – who gave meaning to their struggle and represented the future of the revolution – to irreparable suffering. The experiment they embarked on with the nursery demanded that all involved – children and adults, parents and sons and daughters – cross yet another emotional and affective border: living and caring for one other while having death on the horizon.

The nursery was intended as something temporary, framed in the Montoneros’ exile experience and in the policies implemented to find refuge during that time. The idea was for the children to live in a home that reproduced family life, hence the recruiting of couples. As Pfluger recalls, when she was approached it was stressed that they were not meant to replace the parents. She explains, ‘We were to be the compañero aunts and uncles. We talked about that all the time.’Footnote 63 This emphasis on the importance of assuming certain maternal and paternal roles without replacing the biological parents was in line with prevailing psychological ideas of the time, linked to a functionalist view that insisted on the importance of ‘roles’ over the individuals who played them. Many Montonero militants were psychologists or psychology students, including Silvia Tolchinsky, who performed administrative tasks for the leaders and whose children later stayed in the nursery when she returned to Argentina to fight in the counteroffensive.Footnote 64

Thirty-five years later, Pfluger was interviewed for the nursery documentary. ‘You kids were our treasure’, she tells director Virginia Croatto, who was one of the oldest girls in the nursery. ‘It was for you that we fought, to achieve the country we dreamed of, a socialist country, a country of social justice.’Footnote 65 That idea was enormously powerful, perhaps because it was so straightforward and no doubt because it connected with long-standing ideas: modern constructs regarding childhood; the Peronist tradition for which children were the ‘sole privileged ones’; and the revolutionary and socialist culture of the Latin American Left, which viewed children as political subjects. It was that intersecting of ideas that placed children at the heart of the Montoneros’ rhetoric, actions and political strategy from the start. Children expressed, concretely and profoundly, the reason they fought for a radical transformation of society. At the same time, they represented the future of the revolution, as they were the ones who would build a revolutionary society.Footnote 66

These ‘treasures’ were also their own children, and they found themselves in extreme circumstances. The children felt the risk, although with varying degrees of consciousness. ‘We all knew they could die’, Croatto says about their parents. In contrast, Eva Rubio recalls, ‘I had no real sense of death, no idea what dying meant, but what I did know was that they weren't coming back for us.’ Perhaps the difference in memories has to do with their different ages and levels of maturity at the time. As Volnovich explains, it is only at age six or seven that children can truly grasp the irreversibility of death. In any case, these accounts show the distress they felt over their parents’ absence, combined with fear that they would never return. These were not fantasies. At least seven of them lost one or both parents while they were at the nursery as children.Footnote 67

The adults were aware of the extreme nature of these experiences. Hugo Fucek, one of the carers, says, ‘I knew the kids hadn't chosen to be there, life had put them there; it had been their parents’ decision. But I had made a conscious decision to be there. I knew I had to do everything in my power to help those kids deal with that situation in the best way possible.’Footnote 68 Providing emotional care was the adults’ greatest challenge. It demanded recognising the unequal balance of power in adult–child relationships, which in that context was intensified. As the first adult in charge of the nursery, Edgardo Binstock recalls that initially their priority was addressing the children's emotional and physical needs to help them cope with their new circumstances. Then, when Brardinelli took over, that commitment was expanded to include psychological counselling provided by Volnovich.Footnote 69 As Volnovich recalls it, there were only a few children who showed worrying signs of distress. According to him, in Cuba the children saw their parents as revolutionary heroes and did not feel abandoned by them, as they were often in contact. At the same time, they benefitted from the care provided by the adults and the friendship of their peers. However, the carers were still concerned about how the situation would affect the children. ‘I was afraid they would hate us’, one of the adults told me. When they see them again today, they are relieved to learn that this was not the case.Footnote 70

The very notion of a nursery can be thought of as a collectively shared fiction, which masked both an orphanage-like institution and orphanhood as a possible fate for the children – if not a reality. That masking was prompted by the meaning orphanages evoked in Argentina, as they had been spaces for poor children whose parents could not care for them or had been declared unfit by the state. Orphanages had long been criticised. Over the years there had been countless efforts, always unsuccessful, to make them more like a home and less like an institution. During the first two Perón governments (1946–55), as part of that leader's goal to dignify the working classes and the disadvantaged, the state implemented childhood policies that focused on improving the situation of poor children, including turning orphanages into ‘homes’. In the 1970s, however, orphanages and institutions for the care of minors were far from that. Montonero militants denounced the abuse children suffered there and even rejected them completely.Footnote 71 In keeping with the Peronist and Montonero identity, the nursery had to be a radically different place, one that did not evoke the negative images associated with traditional orphanages.

Essential in this masking was the quality of the care given to the children, how it was administered, the facilities where they were housed, and the comforts provided. ‘We were privileged’, Croatto recalls, using the term associated with the Peronist view of childhood.Footnote 72 When the first contingent of children arrived, they were greeted in temporary facilities that included a room full of toys. Six months later, they moved into two spacious and comfortable buildings that were child-friendly and especially conditioned for them, with small toilets in the bathrooms and a sandbox in the backyard. Two Cuban militants, Bella and Mirella (whose last names have been forgotten, unlike those of the men in charge) helped with the running of the house, and while they comforted the children and cleaned and cooked for them, their role was also political. Special Troop agents delivered their groceries, including food available only to foreigners, as well as supplies from Mexico brought by the bimonthly contact.Footnote 73 Although these privileges set them apart from their Cuban peers, none of the children flaunted them or took advantage of their situation.

Such care and facilities gave material substance to the notions of ‘family’ and ‘home’, dispelling the ‘orphanage’ spectre. The nursery, however, did not mean the same for everyone. Miguel Binstock, who was in the nursery as a child, explains now that each child incorporated it into their identity and emotional experience in their own unique way, according to their individual circumstances.Footnote 74 Some were there with one parent, sometimes both. The adults who had their children with them felt guilty, going out of their way to treat them like the rest, Brardinelli recalls self-critically.Footnote 75 In practice, however, the circumstances led them to relax that self-imposed rigidity and contemplate the differences between the children in order to treat them accordingly. For some, many of whom were very young when they were there, the nursery was where they last saw one or both parents, so it represents a very painful moment in their lives. There are also those who were reunited with their mother and father, even if in some cases one or both were later killed or disappeared.

Thus, the nursery cannot be separated from the rest of their history. As Chaves reflects, for most the experience was a brief part of a much longer history. She, like others, does not want her story to be seen as a ‘terrible childhood’. It had its happy moments, filled with games and friends. She knows that many children who are not the sons and daughters of armed militants suffer losses. While she is right, the experience of these individuals as refugee children in Cuba requires acknowledging those painful periods and extreme situations that extended beyond their life in the nursery but also included it.Footnote 76 They were ‘extreme’ because of the very tension between the adults’ political and affective commitment to a cause and their parental love and duty of care for their children. But also because many of these adults were cruelly murdered and disappeared for wanting to change the world and they were taken from their children without giving them the chance to bury and properly mourn them. This is another aspect of the tragedy.

How did the nursery children react to their circumstances? Under the term reactions I include a wide range of unpremeditated, often unconscious, attitudes through which they coped with or expressed pain, fear and distress. Discussions in the field of childhood studies have tended to read these types of reactions in terms of reasserting the agency of children. However, rather than merely lending support to that idea – which has been so overused to explain any reaction or attitude to power as to have been drained of all meaning – I am concerned with understanding the nature of these reactions and the fact that they were limited, variable and framed in relationships of power. By relationships of power, I not only mean the relationships between parents/caregivers and the children, where the former were in a position of power with respect to the latter. They also include, more importantly, the power relations those adults found themselves in, where they were not in a position of power, as they were targeted by a systematic plan to annihilate political militants, which was supported by international alliances and deployed globally.

While according to Volnovich's recollection the nursery's carers did not have to deal with cases of serious distress among their charges, accounts by those who were there as children show that they did express certain emotional pain and anxiety in obvious ways, although differently and with varying intensity. Bed-wetting and nightmares were common reactions. While we have no way of knowing if these occurred more or less than in other contexts, the adult caregivers and those who were in the nursery as children remember these reactions as something that began there. Other kids refused to eat, and in some cases more serious effects were reported. Some suffered night terrors, one hardly spoke at all (he had been born in the woods and spent his early years hiding there with his family), and another rocked back and forth staring into space.Footnote 77 The fear they felt for their parents’ fate reveals an inversion of the traditional roles of adults and children, with children now worrying about their parents, and sometimes also caring for their younger siblings. The older children expressed those feelings differently. Some rebelled against the rules and what was expected of them, as they were required to help out and set an example. They neglected their schoolwork and ignored curfews and schedules. But there were also others who over-adjusted and denied themselves the possibility of expressing their fears.Footnote 78 Thus, the diversity of reactions had to do with the psychological characteristics of each child, which were also significantly conditioned by their age and ensuing resourcefulness, as well as their degree of autonomy, which, in any case, is always relative.

Being part of a group also shaped their reactions. Having to be with other people all the time, with little privacy, and following strict rules was certainly difficult for many children. But it also meant they could share their circumstances, see themselves in each other and participate together in an everyday life deeply marked by politics. It was a defining experience for the children's identity at that time and, later, at every stage in which they processed it. It also meant that the older children would sometimes care for the younger ones, even though this could feel like a responsibility they were not yet mature enough to take on. Overall, they found comfort in each other, were aware of one another's pain, and could lend support and, at the same time, feel they were not alone. Footnote 79

Their reactions also included games, as another way of processing their experience and coping. Those who were just toddlers in the nursery retain only sensations and brief flashes, many connected with pleasurable things: the fish tank they had in the house, a water fight, a fragment of a song they listened to, the afternoon heat at nap time.Footnote 80 Those who were a little older remember playing at being grown up, which, for them, was as young as ten, the age of their eldest peers in the nursery (which reveals their perception of maturity). They wrote grand statements, organised mock marches and fought with toy weapons – in short, they played at being their parents. There was, however, one game in which they did not mirror their parents’ world, a game that put them in a position of power. They imagined that when they turned the ‘mature age’ of ten they would build a ‘super machine’ that would bring people back to life.Footnote 81 This fantasy no doubt expressed their desire to rescue those who they knew were dead or could die, including their parents. It reveals the unique way in which the children processed what they knew, repairing in their imagination what was impossible to repair in real life. Their collective playing thus comforted them.

Their shared children's universe gained such significance for them that it overshadows the memory of the adults in the recollections of some former nursery children. Without denying that there were grown-ups in charge, looking back now the present-day adults who were in the nursery as children are unable to evoke those adults in their mind's eye as physical presences. Some who were actually very small back then (as young as three or four) remember feeling ‘big’ and responsible for the littlest ones. This evidences the relative nature of age, which takes on different meanings depending on the circumstances.

The adult figure they most remember is that of ‘Tía Porota’, a sassy aunt character created by Fucek, who dressed up as a woman to distract the children when they felt especially sad. The character was so effective it won over some high-ranking leaders who had initially frowned upon such frivolousness. This brings us to a dilemma that adults faced: How could they give the children emotional support in such circumstances? We can identify four different measures they adopted in this sense.

The first had to do with the value they placed on truth. Before separating, parents were required to explain to their children that they were leaving to join the struggle, but that they would come back for them. This information was connected with the children's knowledge of the revolutionary project. The explanation was naturally adapted to contemplate each child's age. If they were three or four, they were told that their mother and father had to go fight the ‘bad guys’ who ruled Argentina, so that all children could have the same possibilities in life. Children also had to be told when they lost a parent. Unlike many relatives, who would try to spare them any suffering, carers at the nursery had clear instructions that even the youngest children had to know when a parent died, and that information had to be conveyed either by the surviving parent or by another relative.Footnote 82 This approach to the truth reveals how seriously children were taken, and it can be viewed as part of this militant culture, no doubt influenced by psychoanalysis. It was later reflected in the strategy of the Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, as they insisted on the right of stolen children and babies to learn their true identities.

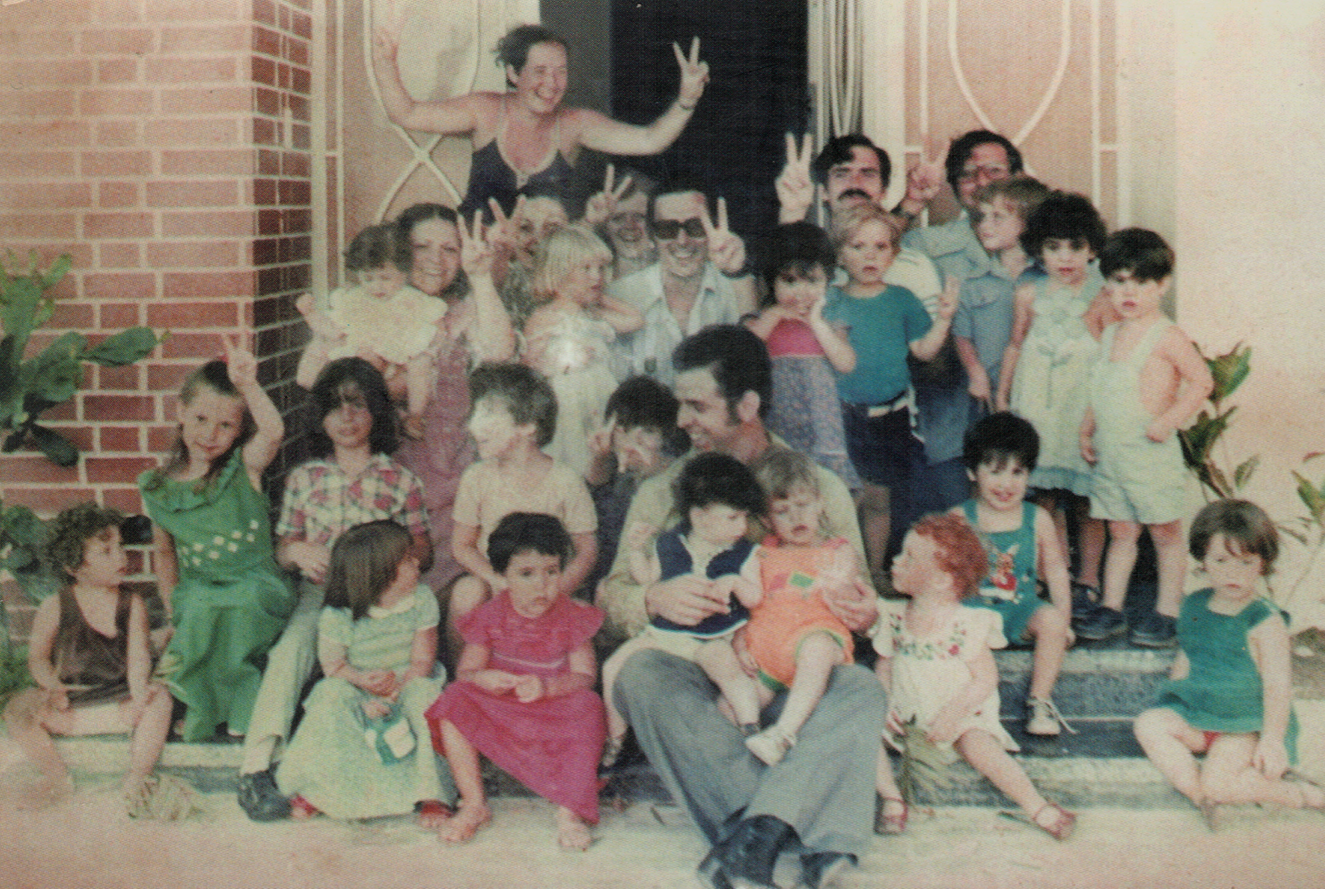

The second measure was related to the children's participation in the forging of political bonds and in rituals, expressed in the militaristic ethos of the organisation and the authority of the leaders (exacerbated in exile with the use of uniforms and the military salute). At the same time, the children provided the other side of this highly structured life. They allowed the often very rule-oriented and dogmatic leaders to display tenderness, accepting the irreverent nature of children. This prompted different reactions, depending on the connection established between them and the children. For example, it was reflected in the games some children engaged in, dressing up as guerrillas and playing at armed struggle. That connection served to reaffirm the political ties with their parents, the concept of fraternity and the sense of belonging to one large family. Figure 1, showing a group of leaders surrounded by children, all of them relaxed and smiling, illustrates the tight bonds that held the political family together and the role of leaders as aunts and uncles. As one of the founders and commanders of the Montoneros, Mario Firmenich's position at the centre of the group speaks of a certain self-perception as pater familias and maximum leader.

Figure 1. Children and Adults Surround the Montonero Leader Mario Firmenich

Source: Photographer unknown. Images reproduced in Argento, Guardería Montonera.

The third measure involved sustaining the figure of the children's parents, for which specific instructions were given. The parents had to leave letters, photographs and cassettes, which the children kept in a space of their own they were assigned from the start. And while they initially shared some household items, each had their own personal belongings. This helped them develop their own identities and express their personalities.

The fourth measure had to do with the children's autonomy, the celebration of their carefree nature, and the fostering of recreational activities. ‘Those crazy little people’ was the expression used by Fucek to refer to the pibes (the Argentine word for kids), echoing a popular song by Catalan singer-songwriter Joan Manuel Serrat, to convey the acknowledgement of the playfulness typical of children. In doing so, he exhibited a critical self-awareness of how grown-ups imposed their views on the world of children.Footnote 83 This was complemented by the incorporation of psychological and psychoanalytical approaches to help the children deal with their suffering. In this sense, in addition to the therapeutic game with the Tía Porota character, the adults – who were themselves very young – suggested other forms of entertainment (water fights, guitar playing, singing, drawing), which were meant to distract the children but may have also helped the adults process what they were going through and forget, if only momentarily, their own distress (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Games Became Crucial to Face and Process the Suffering

Source: Photo taken by Nora Patrich, circa 1978. Courtesy of Nora Patrich.

There is a notable difference between the games suggested by the adults and those made up by the children. The fantasies invented by the latter did not obliterate their own anguishing reality, but operated on it, and by doing so they processed and relieved their distress. Their games allowed them to imagine themselves as adults, capable of acting for themselves as the grown-ups they looked up to did, but also with a power that those adults lacked: the power to beat death with their ‘super machine’. In contrast, the games proposed by the adults were aimed at momentarily dispelling their distress and creating a parenthesis of joy.

Conclusions

Feminist theory has taught us that there is always a political dimension to love. But that dimension is not fixed; it depends on the historical context. In the heated scenario of the Cold War – that is, in the spaces marked by a violent and even bloody struggle to change the status quo – the political dimension of love had very specific implications. The brutal repression militants faced under a plan to annihilate them – which involved torture, murder and disappearance – compromised every aspect of their lives and meant that the love they felt for their partners, their families and even their children had explicit and strategic implications. This was particularly so when state terrorism began targeting children. Acknowledging that children could be direct victims entailed a major mentality shift among militants, who had to individually and collectively accept that such inconceivable cruelty was possible. By targeting children, counterinsurgency repression crossed a boundary that was part of globally shared values, thus refuting the claim held by many in Argentina that the violence of the revolutionary groups can be equated with the violence perpetrated by the state in seeking to annihilate them.

Revolutionary organisations were no strangers to the politicisation of private life that characterised the 1960s and 1970s, expressed in two converging but distinct movements: women's liberation and the questioning of prevailing relationship and family dynamics. These global movements sparked intense discussions among militants in their everyday lives, in what was already a close intertwining of affections and ideological convictions that structured their political practices and strategies. The spaces of the couple and the organisation were further fused under a repressive context of mass kidnappings and disappearances, reaffirming a dynamic in which political relationships were firmly intermeshed with love and friendship, and even blood ties, and in which the couple, as a unit cemented by both love and politics, became crucial for the organisation's military strategies. For militants, as individuals, this intertwining of love and politics was not without complications, prompting intense discussions and distressing situations that challenged the various interconnected dimensions of their bonds. The organisation's decisions affected couples and vice versa, often causing ruptures or increasing the risks and suffering they faced, more so when decisions involved the wellbeing of children.

In that context, childcare took on a whole new political dimension. The political nature of childhood had been a foundational aspect of various political and ideological projects, including those of revolutionary left-wing groups, where children were the reason for the revolution, representing the future and guaranteeing the group's continuity. The repression's ruthlessness gave new political meaning to the protection and survival of children, leading the Montoneros to devise a strategy that allowed both members of a couple to return to Argentina to fight while their children were placed safely in the organisation's care.

Finding a way to safely care for the children was thus framed in a political and military strategy and entailed a shift in how relationships between militants and their children were understood. This was reflected in Cuba's internationalist and solidarity alliances, and in its diplomatic relations. The children were elements that were taken into account when shaping those alliances and they served to relieve the tensions that existed between Montonero leaders and the Cuban government due to the latter's decision not to sever diplomatic relations with the Argentine dictatorship. They also revealed that, even in an internationalist, like-minded environment, there was still concern among Montonero militants that their children would lose their national identity, while the children themselves were able to incorporate a multiplicity of identities seamlessly.

The adult−child dynamics in the nursery expressed the intertwining of affections and politics in everyday life. The children lived with the awareness that their parents were collectively in danger. They had their own active ways of coping with that knowledge, ways typical of childhood, such as the importance they attached to play. This at the same time reveals that their agency cannot be understood without considering the power relations in which they were embedded. The adults entrusted with the children's physical, psychological and emotional wellbeing devised various daily strategies (fostering a sense of collective belonging, providing parental figures, forging political and affective bonds, offering release through play) to shelter them from the pain caused by their extreme circumstances, which nonetheless also evidenced the limits of their protection in the face of an increasingly brutal persecution.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank JLAS reviewers and editors, participants at the various seminars where I presented my ideas, and Silvina Merenson for their comments; and Laura Pérez Carrara, my friend and translator, for skilfully rendering my words into English. I am also grateful to the people I interviewed, especially Virginia Croatto and Mariana Chaves, for opening up their memories to me and sharing their thoughts. Finally, I thank the Gerda Henkel and Tinker foundations for their support to different parts of this project.