Popular radicalism was the creature of print. It coincided with a period when newspapers, periodicals, and pamphlets, not to mention the theatre, promised to open politics up to the scrutiny of a wider public than had hitherto been known. Print was also literally understood to offer the opportunity to make a name for one’s self. The pages of the World made Robert Merry a celebrity as the love poet ‘Della Crusca’. He put this fame aside in 1790 to write high-flown odes on freedom under his own name, but continued to purvey newspaper satires in the cause of reform, either anonymously or as ‘Tom Thorne’ in the Argus. But he was not simply free to remake himself in any way he chose. ‘Robert Merry’ was denied the right to the ‘freedom of the mind’ he asserted in his poetry when he put his name to the service of popular radicalism. To write in this cause was deemed by the conservative press to be resigning the independence only a gentleman could presume to own. ‘The poet and the gentleman vanished together’ to become a creature of print in a sense his former friends thought entirely servile.1 Merry did eventually find a realm of comparative freedom in the United States shortly before he died in 1798, aged only forty-three, although even there his name drew opprobrium from loyalists like William Cobbett, who represented him as ‘poor Merry’, a man whose political enthusiasm had forced him to sacrifice his independence to the theatrical career of his wife.

Odes, dinners, toasts, and plays

On 14 July 1789, ever the cosmopolitan, Robert Merry was in Switzerland, taking a break from the reputation he had created as ‘Della Crusca’. Two weeks later, he wrote a melancholy poem ‘Inscription written at La Grande Chartreuse’. When it was published the following year, it appeared simply over the name ‘R. Merry’.2 The Della Cruscan craze had been incubated in a period of exile in the early 1780s, when Merry had struck up a friendship with various literary figures, including Hester Lynch Piozzi.3 Piozzi continued to keep an eye on his career, although she was on the watch for deficiencies of character and increasingly despaired of his radical politics. In January 1788, she had written in her journal:

Merry is a Scholar, a Soldier, a Wit and a Whig. Beautiful in his Person, gay in his Conversation, scornful of a feeble Soul, but full of Reverence for a good one though it be not great. Were Merry daringly, instead of artfully wicked, he would resemble Pierre.4

The mention of Pierre, the conspirator from Otway’s Venice Preserved, a play that proved to be controversial in the 1790s, hints at the subversive proclivities of a man who Piozzi understood as unmoored from any stake in his country’s established order. Over the winter of 1788–9, Merry dabbled in the print politics of the Regency crisis. His ode on the recovery of the king – co-written with Sheridan and recited by Sarah Siddons for a Subscription Gala at the Opera House on 21 April – was an exercise in opportunism that he tried to disown, at least to Piozzi.5 The French Revolution gave him a new direction, although the ‘Inscription’, written in July 1789, only returned to themes that had run through his earlier poetry: the condemnation of the hierarchies of the old order (‘the sumptuous Palace, and the banner’d Hall’); the illusions of Christianity (’deluded monks’), and the need for writers to champion the cause of liberty (‘But still, as Man, assert the Freedom of the mind’). Such commonplaces of the European republic of letters were easy to write in 1789, but whether they were to translate into anything more was the challenge of the Fall of the Bastille.

Perhaps the first substantial expression of Merry’s intention to take up this challenge was The Laurel of Liberty (1790), the poem that appeared under the name ‘robert merry, a. m. member of the royal academy of florence’. Published by John Bell, ‘bookseller to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales’, and at this stage at least, owner of the World, there was no necessary break here with the world of the Whig and the wit. The elegant format of the slim volume hints at Merry’s connections in the bon ton, but its dedication is ‘to the National Assembly of France the true and zealous representatives of a Free People, with every sentiment of admiration and respect’.6 Around this time, Merry started to lose interest in his connections with the World. Merry and its editor Edward Topham had shared a mutual interest in the Literary Fund in 1790, but Topham was soon begging Becky Wells, the actress who effectively managed the paper for him, to do what she could to keep Merry on board: ‘In regard to public business, you must see Merry, for he appears to me now to be doing nothing.’7 More telling of Merry’s direction of travel at this point were those he joined on the board of the Literary Fund, including David Williams and Godwin’s friend Alexander Jardine. The change was also registered in the reception of his writing. Despite some reservations about the ‘pomp of words’ in the Laurel of Liberty, the Monthly and Analytical reviews were becoming enthusiastic supporters of his work. In November 1790, Horace Walpole’s traced Merry’s political enthusiasm to ‘the new Birmingham warehouse of the original maker’. ‘Birmingham’ here is a metonym for Joseph Priestley and Dissent more generally. By 1793 the author of Political Correspondence or Letters to a Country Gentleman – tellingly a Joseph Johnson publication – could feel confident enough to list Merry among the ‘ablest pens … employed, on this occasion’, Priestley among them, ‘in vindicating the cause of Truth and Liberty’.8

Merry’s political enthusiasm always had to contend with his need to generate an income sufficient to support a fashionable lifestyle. Although he began to publish over his own name in the early 1790s, his social status and independence were threatened by his precarious financial position. Having squandered his inheritance in the 1770s with profligate habits he never entirely forsook, Merry was necessarily invested in the career open to talents, but underpinned by an assumption that he was in the vanguard of an aristocracy of nature. John Taylor had a straightforwardly economic account of Merry’s trajectory in this regard:

Merry was in France during the most frantic period of the French revolution, and had imbibed all the levelling principles of the most furious democrat; having lost his fortune, and in despair, he would most willingly have promoted the destruction of the British government, if he could have entertained any hopes of profiting in the general scramble for power.

Despite their political differences, Taylor frequented the same circle of wits that scribbled for the press. Given that Merry repudiated him as ‘the reptile oculist’ in the Telegraph in 1795, Taylor’s judgements were far from impartial, but he does indicate the way financial need coupled with political belief to force Merry to try a variety of experiments with print politics.9

Perhaps the most unlikely of these experiments was A Picture of Paris, a pantomime written in collaboration with Charles Bonner and the musician William Shield. Presented at Covent Garden on 20 December 1790, its plot shadowed the events of the French Revolution up to the Fête de la Federation of 14 July 1790, promising ‘an exact Representation of … the grand procession to the Champs de Mars … the whole to conclude with a Representation of The grand illuminated platform … on the Ruins of the Bastille’.10 The climax is the Federation Oath where Louis XVI swore to use the powers delegated to him by the National Assembly to maintain the new constitution. The theatre historian George Taylor sees the production as eager to present the Fête as consonant with British liberty. Building on the fact that the Lord Chamberlain licensed the piece, Taylor concludes ‘that the authorities in England shared the belief of French moderates that the Fête marked the end of the French revolution’.11 David Worrall rightly suggests that Taylor neglects the fact that the script would not have given Chamberlain too much sense of what happened on stage in the pantomime.12 Presented only a few weeks after the publication of Burke’s Reflections, A Picture of Paris was entering a rapidly changing scene. The Argus (20 December 1790) thought that ‘the Managers of the house deserve equally the thanks of the several authors, and of the public at large, for the uncommon liberality displayed in the getting up every scene of this Piece’, but then its editor, Sampson Perry, was a sworn enemy of Pitt’s. In its review of the pantomime, The Times (20 December 1790) questioned ‘the propriety of such scenes on British ground’. The theatre, it thought, ought ‘to steer clear of politics’. British liberty, it insisted on 30 December, was quite distinct from what had been celebrated on the Champs de Mars:

We should be glad to be informed what reference the statues of Truth, Mercy, and Justice, exhibited in the new Pantomime of the Picture of Paris, has to the subject of it. – Surely the author of this incoherent jumble of ideas does not mean to affirm that the Revolution in France is founded on any of these godlike virtues.

Unquestionably, The Times continued, representation of a monarch as merely the delegate of the National Assembly did not pass muster with George III: ‘As far as we could collect from looks, the Royal Visitors were certainly not of the opinion with sterne in the instance of debates at least – that “They manage these things much better in france”.’

Merry was starting to exploit any means he could to disseminate his enthusiasm for the Revolution. The preface to the Laurel of Liberty (1790) attacked complacent members of the elite ‘so charmed by apparent commercial prosperity, that they could view with happy indifference the encroachments of insidious power, and the gradual decay of the Constitution’. He was confident that the ‘progress of Opinion, like a rapid stream, though it may be checked, cannot be controuled’.13 If Merry represented ‘Opinion’ as an occluded species of print determinism here, he was also doing everything possible to shape it through the newspapers. He told Samuel Rogers in 1792 that Sheridan had asked him to write for the Morning Post during the Regency Crisis: ‘No man can conceive says he the effect of a daily insinuation – the mind is passive under a newspaper.’14 Merry was already aware of print magic as a dark art and not one to which he readily put the name of ‘Robert Merry’. In 1794, Godwin recorded that ‘Sheridan fills Merry’s hat full of arrows’, that is, Sheridan was feeding Merry with information to use as anonymous newspaper ‘paragraphs’.15 Usually biographical information of one sort or another, blackmailing or satirical ‘paragraphs’ were frequently used as political weapons. Writing in 1803, David Williams traced the use of ‘fleeting arrows’ to Fox’s manipulation of the newspapers to bring down the ministry in 1783.16 Plenty of the insider gossip useful to paragraph writers circulated at theatrical clubs where Merry mixed with Sheridan, Taylor, and others. By early 1792, however, Merry was starting to make radical connections beyond this world and becoming what his friend Samuel Rogers, not altogether approvingly, described as ‘a warm admirer of Paine’.17

Merry’s name added lustre to the political dinners discussed in Chapter 1. His Ode for the fourteenth of July – again elegantly published by Bell – was written for performance at the dinner for the friends to the French Revolution held at the Crown and Anchor, as we saw earlier. The festivities were presided over by the Whig MP George Rous. William Godwin seems to have been there, but only as part of the crowd. By this stage, the World was no friend to Merry. He was probably intended as a target of its hostile description of the diners as ‘men whose profligacy has become proverbial – whose fortunes are desperate, and whose minds are daring and corrupt’.18 The remark may have been provoked by a provocative jibe at his former colleagues in the opening stanza of the ode:

The pun on the name of the newspaper may affirm Merry’s new disposition towards an audience beyond the fashionable daily, but more generally the ode retains the high poetic mode of the Laurel of Liberty. This was the poetry of liberty to which Merry lent his proper name. The ode, especially the stanzas celebrating the ‘animating glass’ discussed earlier in the context of the dinner, was reprinted in the newspapers soon after it was performed and later in various anthologies.20 It provided a vibrantly positive rebuttal of Burke’s fear of electric communication everywhere, but sublimates the medium of print it wishes to exploit into an immediacy that moves from ‘hand to hand’ and then from ‘soul to soul’. In its obituary for Merry in 1799, the Monthly represented him as ‘one of those susceptible minds, to which the genius of liberty instantaneously communicated all its enthusiasm’.21 In the poetry published in his own name, Merry continually presented himself as the authentic conduit of this genius of communication overleaping the complicated terrain of print transmission.

Neither Merry’s reputation for homosocial conviviality, nor the popularity of his ode, protected him from the charge that he was losing his identity as a gentleman in his new political personality.22 On the contrary, he seemed in some quarters to be daringly dispersing his social identity into the mob through the medium of print. In his satires the Baviad (1791) and Maeviad (1795), William Gifford spatialised Merry’s poetry as a ‘Moorfields whine’.23 The tendency of his journalism, not issued over his own name, was also starting to trouble those who wished for moderate reform under aristocratic leaders. At the end of November 1791, Fox reportedly complained that ‘our newspapers … seem to try & outdo the Ministerial papers, in abuse of the Princes, the Morning Chronicle is grown a little better lately, but the others are intolerable, the Gazeteer [sic] particularly, Mr Merry has got that I am told’.24 Merry was certainly still networked into the overlapping worlds of newspapers and theatre. The Times noted (10 January) that a new comic opera called The Magician No Conjuror was in rehearsal at Covent Garden.25 The play did not appear until 2 February, but ran for a respectable four nights, garnering Merry a substantial benefit. The songs sold in pamphlet form, and remained popular enough to be republished in periodicals and anthologies over the course of the year.26 The plot is a standard tale of young love thwarted by old foolishness in the guise of Tobias Talisman, who has retreated to the country to practice the art of necromancy, keeping his daughter Theresa under close confinement. The Gothic possibilities of the female incarceration plot were a favourite of Merry’s, one he scouted in his first play the tragedy Lorenzo (1791), where the heroine is forced into a loveless marriage by her father, and even earlier in A Picture of Paris where it is played for comedy. Much of his writing fantasises about the release of female sexual energies into the arms of a hero somewhat like himself. The hero’s victory in the Magician – where the incarceration plot is again given a comic twist – is guaranteed when he saves Talisman from a resentful mob. There seems to be a loose commentary here on the role of the government provoking the loyalist mob against Priestley, with Merry projecting an idea of himself as the dashing saviour of the situation for the benefit of all.

Most of the newspapers expressed a dim view of the proceedings in their 3 February editions.27 Werkmeister believes that Thomas Harris, the manager of Covent Garden, stopped the play because of its ‘stinging ridicule of Pitt, who, it was all too evident to the audience, was in fact “The Magician”’.28 Although she provides little evidence for this assertion, the idea of Pitt as a conjuror was familiar from earlier Opposition satires. Political Miscellanies (1787) compared him to the popular Italian conjuror Signor Guiseppi Pinetti who had performed in London from 1785.29 Contemporary newspaper commentary does not seem to confirm so specific an identification, but it is clear that responses to it were ideological in general terms. The Earl of Lauderdale’s support for the play, for instance, was noted in the press. Anne Brunton, married to Merry early in 1792, was not re-engaged at Covent Garden after the 1791–2 season, despite her great success in Holcroft’s the Road to Ruin in the spring. By this stage, anyway, the couple were being increasingly drawn towards France. Merry was throwing himself into the radical societies and writing for the radical newspaper the Argus rather than the fashionable pages of the World.

Political societies, 1792–3

‘The Argus is the paper in their pay’, wrote an informer on an LCS meeting at the end of October 1792, ‘and they will have nothing to do with any other.’30 Although the Argus increasingly supported the LCS, its closest relationship was with the SCI. On more than one occasion the Society ordered a copy of the paper to be sent to each of its members. Paine, Horne Tooke, and Merry, who joined the SCI in June 1791, all wrote for it; ‘in short’, remembered Alexander Stephens, ‘it was the rendezvous of all the partizans and literary guerillas then in alliance against the system of government’31. Perry had launched the Argus in 1789 as editor and proprietor: ‘a scandalous paper’, reported the Gentleman’s Magazine in his obituary, ‘which, at the commencement of the French revolution, was distinguished for its virulence and industry in the dissemination of republican doctrines’.32 The Argus certainly insisted that the political elite was betraying the people in terms that echoed Merry’s Laurel of Liberty: ‘You have suffered your Constitution to be gradually invaded, till you are now reduced to a state of the most abject slavery.’33 Pitt was the target of particularly fierce attacks, not least from the satires Merry published in the paper as Tom Thorne:

On 8 May 1792, the same day it printed this squib, the Argus published a paragraph arguing that ‘the present House of Commons … is not composed of the real representatives of the people’. An ex officio information was served on Perry for libelling the House of Commons within the fortnight.

Perry was still in the King’s Bench serving time for previous libels. The date of his release is not clear, but Merry and Perry seem to have collaborated on the paper from at least spring 1792. The poet had successfully proposed Perry’s SCI membership in April 1792.34 ‘During the last months of that paper’s existence’, remembered Merry’s obituarist in the Monthly Magazine, ‘a certain rose was never without a thorne’. The reference was to the controversy surrounding George Rose’s management of elections for Pitt, a row that the Argus covered closely. Merry’s obituary reprinted several of his contributions:

and

The loyalist press even tried to appropriate the Tom Thorne pseudonym to Merry’s evident delight:

The appropriation of the ‘tom thorne’ pseudonym by loyalist newspapers points to difficulty of controlling such shape-shifting productions. ‘His native power’, observed Merry’s obituary, ‘flames out in his odes’, assigning his authentic voice to the poetry that came out under his own name.36 Perry finally fled to Paris before his trial commenced on 6 December to the glee of the World:

The Sampson of the Argus was found too weak to carry off the pillars of the Constitutional Fabric, although he made several ineffectual attempts.37

There he rejoined his colleagues from the SCI, Merry and Paine, among the group of expatriate radicals that met at White’s Hotel. 38

Over the course of 1792, Merry had traced his own uneven course from the Society of the Friends of the People to this much more radical set of associates, some of whom had made similar journeys. Merry’s name is included in the list of those who signed up at the first meeting of Charles Grey’s group of reform Whigs on 11 April, but does not re-appear in later accounts of any of their meetings.39 By May 1792, Grey’s Society had become emphatic in repudiating any association with Paine. On 28 May, Godwin’s diary records that his friend Holcroft was dining with Paine and Merry, although he seems not to have met the poet by this stage himself. Merry was at the SCI on 1 June, when the society received a letter from the LCS recording its ‘infinite satisfaction to think that mankind will soon reap the advantage …[of] a new and cheaper edition of the Rights of Man’. SCI minutes show Merry to have been a very visible presence in the intense period of cooperation between the two societies.40

Merry was working equally hard to open channels of communication between the British and French societies. The Oracle of 15 June reported that ‘Mr and Mrs. merry have taken the Laurel of Liberty with them to France. – The Poet presents his Ode to the national assembly.’ Sounding a note that was to echo across many hostile accounts of Merry that followed, the paper commented: ‘The merry poet has now dwindled into a sad politician!’41 On 28 September, he was present at the SCI meeting when another LCS letter proposed a supportive address to the National Convention. Merry was elected to the committee asked to consult on a joint version. In the same month, he also seems to have begun actively supporting the French move towards a republic in the British press. Advertisements appeared for an apology for the August days and the September Massacres: “a particular account of the Rise, and also of the Fall of Despotism in Paris, on the 10th of August, and the Treasons of Royalty, anterior and subsequent to that period. By Robert Merry, Esq.” I have not been able to trace any pamphlet under this exact title, but it may be A Circumstantial History of the Transactions at Paris on the Tenth of August, plainly showing the Perfidy of Louis XVI. LCS members Thomson and Littlejohn published it from their Temple Yard press with H. D. Symonds. Symonds was given as the publisher of the Merry pamphlet advertised in the newspapers.42

In October, Merry wrote from Calais to his ‘friend and fellow labourer’ Horne Tooke to tell him that the armies of the Republic needed shoes more than muskets.43 In Paris, Merry seems to have been part of the most radical faction of the British Club – opposed by John Frost – calling on the Convention to invade Britain and provoke a popular uprising in support. Frost thought it a misjudgement of the political mood in Britain. Merry’s universal enthusiasm for a democratic republic extended to making his own proposals for the new constitution of France. His obituary in the Monthly Magazine mentions ‘a short treatise in English, on the nature of free government … translated into French by Mr Madget’, almost certainly Merry’s Réflexions politiques sur la nouvelle constitution qui se prépare en France, adressées à la république (1792).44 Understandably enough never published in Britain, Merry’s pamphlet calls for popular participation at every level of the political process, recommending a role for primary assemblies in confirming laws (an issue debated in France that found an echo in LCS discussions of the relation of the divisions to the central committee). There is also a section on the neglect of literary men under despotism, a personal concern expressed in his work for the Literary Fund. The pamphlet leaves the reader in no doubt that Merry thought Britain just such a despotism. Merry shows little patience for the mixed British constitution. The proposed constitution is based on the classical virtues of an active citizenship. If its foundations were formed by a classical education under Samuel Parr, then the pamphlet was unequivocal about the democratic example of France as the only hope for the regeneration of Britain.

Internal exile, Godwinian, and satirist

At the end of 1793 the European Magazine published a pen portrait of Merry:

Having passed the greater part of his life in what is called high company, and in the beau monde, he became disgusted with the follies and vices of the Noblesse, and is now a most strenuous friend to general liberty, and the common rights of mankind.45

Compared with most accounts of Merry published by the polite press in 1793, this one is curiously sympathetic. By the time it appeared in print, Merry had been back in Britain for nearly six months. As France under Robespierre became increasingly suspicious of foreigners, the situation had become hostile for cosmopolitan radicals who had made the pilgrimage to the Revolution. His friends Paine and Perry were in prison in Paris. Merry had managed to get back to London in May with the help of Jacques-Louis David.46 Having kept their readers apprised of Merry’s activities in France, the English newspapers took particular delight in retailing the story of his retreat back to Britain, but other circles were making Merry more welcome. Godwin’s diary records that he and Holcroft dined with Merry on 11 August, but despite these budding support networks Merry had no obvious source of income and the derision of the press must have made life in Britain insupportable. He borrowed money from Maurice Margarot against a bill for £130.47 In September, Merry decided to flee for Switzerland with his wife and Charles Pigott, funded by a bank draft for £50 from Samuel Rogers. On 2 September, still keeping their erstwhile star contributor under surveillance, the World reported that the trio had crossed to the continent. The information was false. They had turned back at Harwich before even boarding ship.

Merry separated from Pigott and retreated to Scarborough. He wrote to Rogers asking for more money and begged that his presence be kept secret, but by mid-October the newspapers had found him out.48 Merry outlined his current projects in a series of nervous letters to Rogers and asked for help finding publishers. He seems to have been in a state of shock, not least about the prospects for political change. On 3 November, mentioning fears that his letters were being opened, he was writing an ‘Elegy upon the Horrors of War’. A month later, he provided an insight into the mental turmoil caused by the dashing of his political hopes:

Yet still am I troubled by the Revolutionary Struggle; the great object of human happiness is never long removed from my sight. O that I could sleep for two centuries like the youths of Ephesus and then awake to a new order of things!

Then on 18 December, Merry sends ‘a little theatrical Piece, which I mean to conceal being Mine not to be exposed Aristocratical Malice’. He described it as ‘a free translation of the French Play, of Fenelon, reduced to three Acts’, but suspected its subject and his name would prevent it being staged:

I do not suppose it will be performed, on account of its coming from that democratic country … if you think it has any merit – get it published for me I beg of you not to mention my being the Translator in case it should be played – as the name of a Republican would damn any performance at this time.49

The Godwin circle provided succour in these difficult months. Merry appears regularly in Godwin’s diary from summer 1794, especially in the vicinity of the radical stronghold of Norwich. Anne Brunton had family connections with the area. Her father, John Brunton, managed the theatre. Thomas Amyot reported Merry’s presence there in May.50 By 15 June at least Merry was ranging further afield, dining with Godwin and Holcroft in London. Merry also started to exert a particular fascination on Amelia Alderson, brought up in these Norwich circles. Her ‘curiosity’ was raised ‘to a most painful height’ when in 1794 Charles Sinclair revealed that Anne Brunton was a ‘firm’ democrat and ‘a great deal more’. Two years later, in November 1796, she admitted to Godwin

Poor Merry! – Will you not wish to box my ears when I venture to say, that I do not think his mind at all matched in his matrimonial connection? Mrs. Merry appears to me a very charming actress, but, but, but – fill it as you please.

Godwin seems to have been scarcely less fascinated, particularly by Merry’s connections with Sheridan and his easy facility as a writer. ‘Mr. Merry boasts that he once wrote an epilogue to a play of Miles Peter Andrews, while the servant waited in the hall’, he told Wollstonecraft in 1796, ‘but that is not my talent.’51 According to his diary, on 26 June Godwin read an ode by Merry. Two days later, the pair dined at the Alderson home in a company associated with Norwich radicalism. Merry read to Godwin ‘specimens of 2 novels’ on 30 June. Merry’s pressing need to make money from his writing drew scornful commentary in the press. Former friends like Piozzi described him as begging for subscriptions, but Godwin seems to have taken his talk seriously, listening to his opinions of Political justice while revising it in July 1796.52 Quite possibly Godwin also helped Merry place his final major poem, Pains of Memory (1796) with his publishers, the Robinsons. During this period, Holcroft wrote a joshing letter to Godwin mentioning ‘our good friend Robert Merry, once an [sic] squire and now a man’, pointing up the poet’s social and political journey from Whig gentleman to radical democrat.53 If Holcroft was celebrating a political butterfly emerging from the pupae of the fashionable Whig, then the oncoming treason trials were reason for alarm to both men. Merry’s name appeared in the SCI minute books used as evidence in the prosecutions of Hardy and Horne Tooke.54 On 11 October, Merry told Rogers that ‘existing circumstances … appear to me hastily advancing to some great catastrophe’. Only four days earlier, Holcroft had surrendered himself in to the court. ‘As things now stand’, Merry told Rogers, ‘I feel some inclination for going with Mrs. Merry to America, and perhaps if I should do so you would put me in a way how to proceed.’55

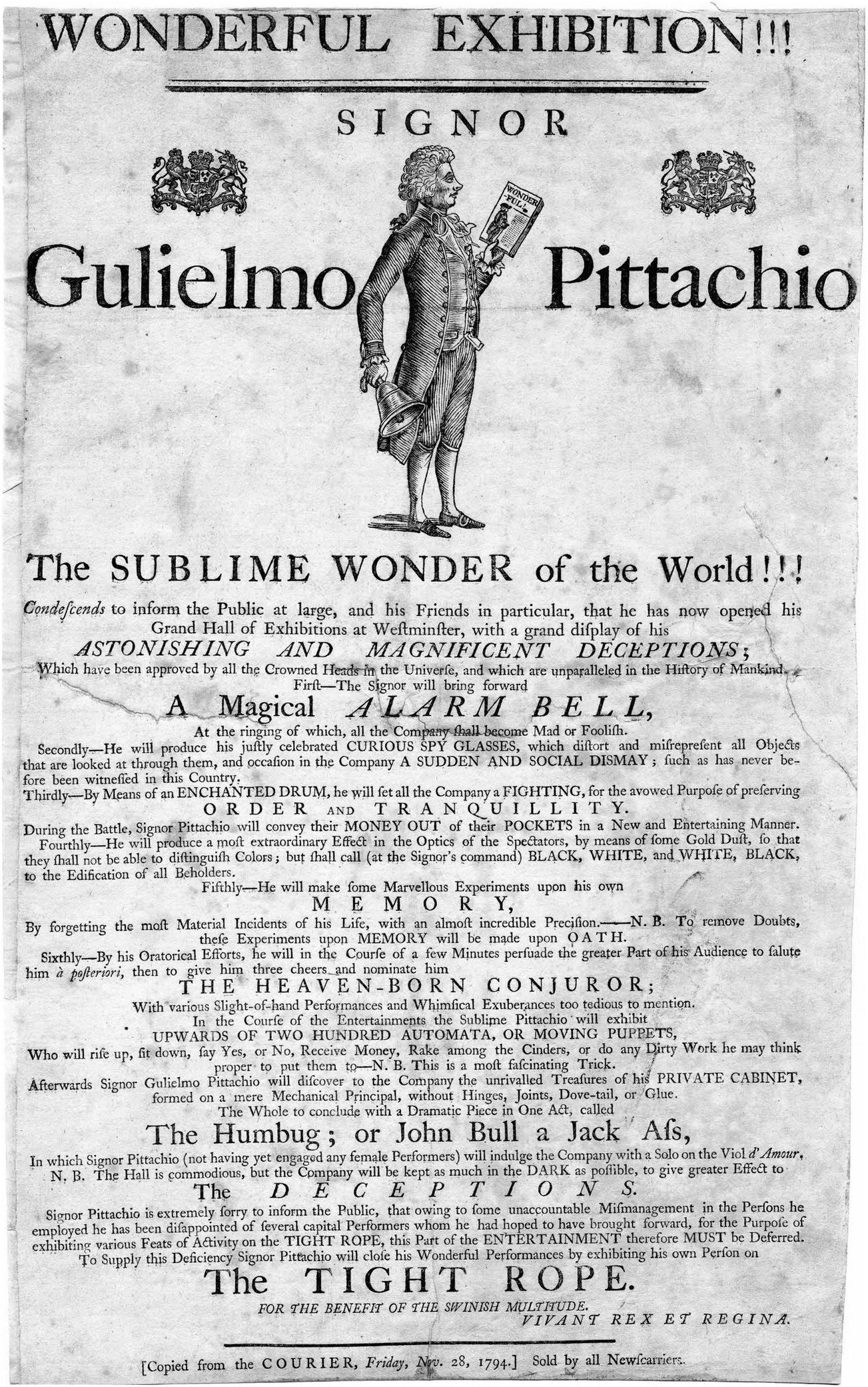

The acquittals of Hardy and Horne Tooke seem to have given Merry a new lease of life as a satirical journalist, just as they powered a surge of activity in the LCS. Although it is impossible to know exactly what part he played in the cheap productions that poured off the radial presses in 1795, he was remembered long afterwards for the great triumph of Wonderful Exhibition!!! Signor Gulielmo Pittachio, the first in a series of pasquinades that followed the acquittal of Horne Tooke on 22 November (Figure 5). ‘No minister in any age had been so ridiculed before’, Merry’s obituary in the Monthly remembered. First appearing in the pages of the Courier on 28 November, Pittachio exploited a trope that went back to the Political Miscellanies (1787) and Merry’s own Magician no Conjuror (1792).56 Developing the satire on Pitt’s ‘surprising tricks and deceptions’ from Political Miscellanies, Pittachio presents Parliament in thrall to Pitt’s ‘magical alarm bell’:

upwards of two hundred automata, or moving puppets, Who will rise up, sit down, say Yes, or NO, Receive Money, Rake among the Cinders, or do any Dirty Work he may think proper to put them to.

‘Unaccountable mismanagement’ means Pittachio is unable to bring forward ‘several Capital Performers … for the Purpose of exhibiting various Feats of Activity on the tight rope’. Pitt had not been able to manage the guilty verdicts against Hardy and Horne Tooke, but the satire ends by flipping this scenario and imagining that he would instead ‘close his Wonderful Performances by exhibiting his own Person on the tight rope for the benefit of the swinish multitude’. The Pittachio series was part of a proliferating number imagining the Prime Minister being hanged for his crimes against the people.

Fig 5 Wonderful Exhibition!!! Signor Gulielmo Pittachio (1794). Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved.

The most striking of these were the death and dissection of Pitt satires that appeared first in the Telegraph in August 1795. Whether Merry had a hand in these is unknown, but on 27 June 1796 Godwin recorded visiting the offices of the Telegraph, where he found ‘Merry, Este, Robinson, Chalmers & Beaumont’. Founded in December 1794, the Telegraph had succeeded the Argus and joined the Courier as the most radical of the English dailies.57 Merry’s obituary in the Monthly Magazine claimed ‘some of the best poetry in the Telegraph was the production of his pen’.58 D. E. MacDonnell, the editor, acted as go-between for Merry with John Taylor in the dispute over the satirical paragraph attacking ‘the reptile oculist’.59 If Merry didn’t write the Death and Dissection of Pitt satires, then he was certainly in the thick of the group of collaborators closely involved in the Telegraph where they first appeared.

Fenelon and The Wounded Soldier – the play and the poem he had told Rogers about late in 1793 – were also published in 1795. Fenelon was never produced, but it was published under Merry’s name and dedicated to Rogers. A partial translation of a play by Marie-Joseph Chénier, Fenelon saw Merry return to the Gothic incarceration plot. Release for the heroine is obtained by the intervention of Archbishop Fenelon, an interesting switch from the dashing hero of the Magician. The choice may indicate the shared interests of the Godwin circle, since Fenelon was one of their acknowledged heroes. In Political justice, it is Fenelon who Godwin imagines saving from a fire – in the interests of humanity – in the famous passage that caused a storm over his utilitarian version of universal benevolence. Holcroft’s account of Merry’s play in the Monthly Review began by praising the role of Fenelon’s book ‘in enlightening mankind’.60 Merry was writing The Wounded Soldier at about the same time Wordsworth was first addressing the same themes in his ‘Salisbury Plain’ poems. Hargreaves-Mawdsley notes that Merry's language ‘is like that of a tract ... intended for the simplest reader’. The effect is surely intentional, even if Merry described his poem to Rogers as ‘to avoid offence … very tame’.61

The Wounded Soldier enjoyed a fairly wide circulation, but first appeared as a penny pamphlet from T. G. Ballard, the author’s name appearing only as ‘Mr. M–y’. By 1795 Ballard was becoming one of the LCS’s regular printers, advertising ‘a great Variety of Patriotic Publications’.62 Ballard also brought out a late version of the Death and Dissection of Pitt satire as Pitt’s Ghost (1795). Citizen Lee also published many of the Pittachio broadsides and various editions of the Death and Dissection of Pitt. He attributed one satire – Pitti-Clout & Dun-Cuddy (1795) – to ‘Mr. M-r-y’, but then later acknowledged an error of attribution.63 Lee’s mistaken use of Merry’s name may have been an over-eager attempt to exploit what glamour, at least in radical circles, remained of it. These publications were probably as close to the LCS as Merry came after he returned from France in 1793. 64 He never took sanctuary there, unlike his friend Charles Pigott. Merry may have felt safest among journalists like those in the offices of the Telegraph, or Dissenting literati like the Aldersons, Godwin, and Holcroft. Such groups often flowed into each other, as Godwin’s visit to the office of the Telegraph suggests, but ultimately they could not provide him with a context to continue writing in Britain.

Transatlantic laureate

Merry continued to see Godwin, especially with Holcroft and sometimes with the moneylender John King, financial troubles making Merry’s residence in England increasingly untenable. The pattern of sociability intensified in January and February 1796 – Godwin seems to meet Merry at a Philomath supper on 12 January – and they see each other several times in April and in June, leaving together for East Anglia on the Ipswich mail on 1 July. A week later Merry was arrested for debt in Norwich. Godwin and James Alderson helped extricate him, but the episode may have determined Merry to leave for the United States.65 Although the emigration of the Merrys had been trailed in the press for some time, it still came as a surprise to Godwin and Amelia Alderson when they left in September 1796. Godwin wrote to Merry too late:

Yesterday evening I heard of your expedition, & heard of it with much pain. I could not forget it all night. I cannot endure to think that a man, whom I regard as an honour & ornament to his country, should thus go into voluntary banishment. If you had thought proper to consult me, I would have endeavoured to dissuade you.

Alderson’s letters to Godwin in October and November 1796 advert to the matter more than once. She found it hard to believe that Merry could possibly be happy in the United States:

I wish much to know how he looked & talk'd when he bade you adieu - whether he was most full of hope, or dejection – My heart felt heavy when I heard he was really gone, & gone too where I fear the charms of his conversation, and his talents will not be relished as they desire to be.

Alderson’s estimation of Merry’s chances of happiness was not untypical of opinion even in progressive circles.66 Writing for prospective emigrants in 1794, Thomas Cooper took the view that ‘literary men’ did not yet exist there as ‘what may be called a class of society’.67 The question of whether the new republic could sustain a literary career was an issue Merry had debated for several years before finally deciding to go. He seems to have seriously considered the option at least twice before he set sail: first, in the summer of 1792, according to the actor James Fennell, when Merry expected the forces of counter-revolution to succeed in their invasion of France; secondly, on the eve of the treason trials, when he asked Rogers for advice about the move.68 His friend Holcroft’s opinion that the United States remained ‘unfavourable to genius’ and uncongenial to ‘energy and improvement’ must have weighed on his mind, but his hand was forced by financial necessity compounded by the political context after the Two Acts had passed into law.69

As it transpired, there was literary culture enough to greet Merry’s arrival with great enthusiasm. Della Cruscanism had been and was to continue to be an important influence on the poetry of the early republic. Pains of Memory was to become one of its most reprinted poems and guaranteed that his arrival garnered various poems of acclaim in response:

Fleeing Britain only a few months before Merry, Citizen Lee published these lines in his American Universal Magazine. Not everyone was as pleased to see him. Bristling in the American press as Peter Porcupine, William Cobbett attacked both men as part of a conspiracy intent on spreading Jacobinism to the United States:

Poor Merry (whom, however, I do not class with such villains as the above) died about three months ago, just as he was about to finish a treatise on the justice of the Agrarian system. He was never noticed in America; he pined away in obscurity.71

The last claim is debatable to say the least.

John Bernard knew Merry from his pomp in the convivial clubs of London, but thought he thrived in America, even enjoying the rough and tumble of electoral politics: ‘exposed to actual collision with the crowd … Merry was the only man I knew for whom it had a relish.’72 A page Merry added to the Philadelphia edition of Pains of Memory suggests he saw the possibilities of a democratic literary culture in the new republic:

Merry seems to have been engaged in thinking about these issues when he died suddenly in 1798, leaving behind him his own dissertation on ‘the State of Society and Manners’, addressed to ‘the curiosity of the European reader, respecting the comparative situation of the United States’.74 Over the course of the 1790s, Merry’s experiences in Britain, France, and the United States had given him ample material for such a study. In the process, Thomas Holcroft thought, he laid aside his elite identity as a squire and emerged as a properly independent man. His remaking of himself as he engaged with the implications of the French Revolution was somewhat more complex than Holcroft’s perspective allowed. If the poet and the gentlemen were not entirely sacrificed to the politician, as his enemies proposed, then they did become part of a complex process of self-fashioning in print that ended only with his death in exile.