German engineer Ernst Ruska designed and built the first electron microscope, a device that far surpassed previous resolution capabilities and allowed scientists to view things too small to be seen with a light microscope. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1986 for the feat, an honor he shared that year with Heinrich Rohrer and Gerd Binnig, who co-developed the scanning tunneling microscope.

Born on December 25, 1906 in Heidelberg, Germany, Ruska was the son of an Asian studies professor and the fifth of seven children. Many of his closest relatives were academics, and his parents believed that he too might follow such a path. He studied at the Technical University of Munich from 1925 to 1927 and then moved to Berlin to attend the Technical University located there. While still enrolled in school, Ruska began to lay the groundwork for the achievement that would be his legacy. Under the tutelage of Dr. Max Knoll, Ruska developed an interest in the idea of electron microscopy. Realizing that optical microscopes were limited by the wavelength of the light beams used to view a specimen, Ruska determined that since electrons have much shorter wavelengths than light, they could be used to obtain greater resolving power.

In 1931, working closely with Knoll, Ruska built the first electron lens, an electromagnet that could focus a beam of electrons as if it were light. Using several such lenses, he was able to construct a prototype of an electron microscope, though with only the ability to magnify a meager 17 times. Yet, he had proven that the task was possible, and he continued to improve his design. By 1933, Ruska's electron microscope, termed a transmission microscope, was much more powerful. The instrument worked by passing electrons through a thin slice of the specimen to be studied, which were then deflected to a photographic film emulsion or projected onto a fluorescent screen, generating an image at high magnification. In fact, the device was capable of magnifying specimens up to 10 times more than a contemporary light microscope.

To build a commercial version of his microscope, Ruska was forced to briefly leave the academic world and delve into private industry. He joined the Siemens Company as an electrical engineer in 1937, and the company released its first marketable electron microscope, based on Ruska's design, in 1939. Ruska continued an association with the company until 1955 but concurrently held various academic posts. After departing from Siemens, he became director of the Institute for Electron Microscopy of the Fritz Haber Institute, a position he held until 1972.

When Ruska was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1986, the Committee described his electron microscope as one of the most important innovations of the 20th century. By that time further improvements of the device had made it capable of magnifying an object up to 1,000,000 times its original size. A staple in upper-level laboratories, the electron microscope has made it possible for scientists to study miniscule structures, such as viruses, proteins, and even atoms. Although Ruska passed away two years after he was honored with the prestigious award, his work continues to have a lasting effect on science and humanity.

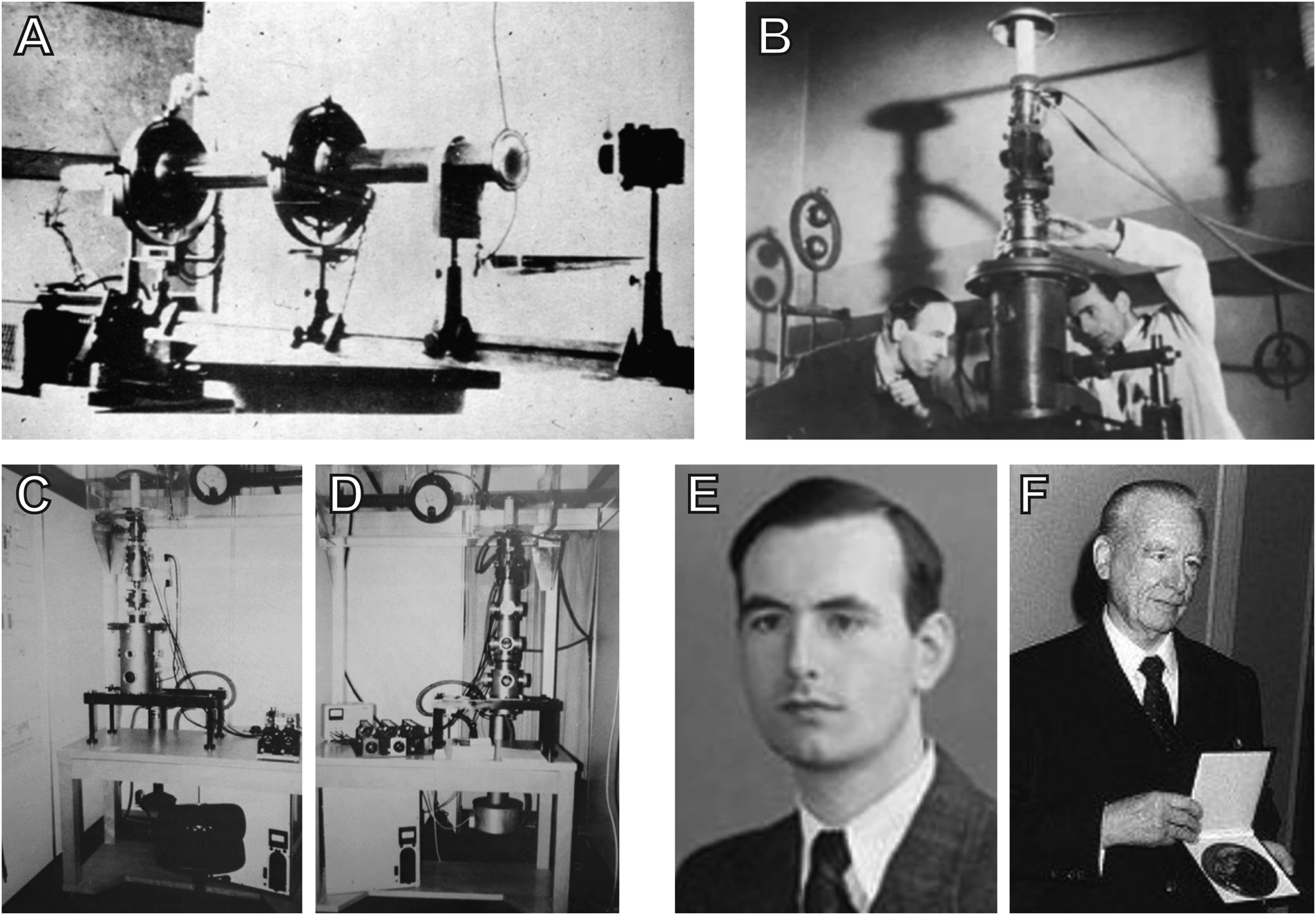

Timeline of Ernst Ruska and the development of the TEM. A. The first instrument, developed in 1931. B. The second instrument in 1931. Pictured here with his mentor, Max Knoll. C. The second instrument in 1931. D. The third instrument in 1933, capable of higher magnification than a light microscope. E. Ernst Ruska, 1939. F. Ernst Ruska with the medal for the Nobel Prize in Physics, 1986.