The Dissertations of Jingyi Huang, Pawel Janas, and Sebastian Ottinger 2022 Allan Nevins Prize Competition of the Economic History Association

Next year marks the 50th anniversary of the formal establishment of the Allan Nevins Prize.Footnote 1 So, with four decades worth of data on past finalists for this award, I thought it fitting to begin my discussion by looking back at their history.

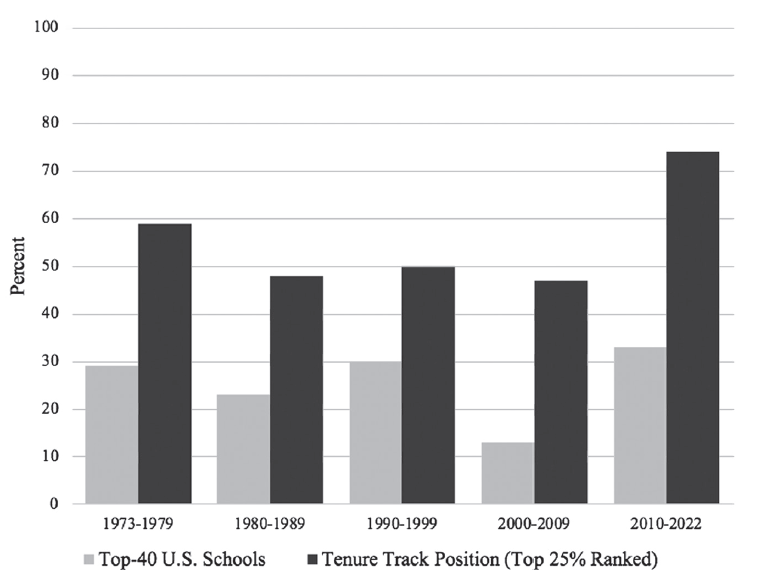

Where do Nevins finalists go? Figure 1 shows the first job placement of Nevins finalists by decade. I focus on two outcomes: the fraction who landed positions in the top-40 U.S. economics departments or equivalently ranked international schools, and the fraction who obtained tenure-track positions at REPEC-ranked departments.Footnote 2

Figure 1 FIRST JOB PLACEMENT OF NEVINS FINALISTS BY DECADE

Notes: School rankings were made based on the 2022 REPEC ranking of economics departments.

Sources: Finalists were retrieved from various issues of the Journal of Economic History. Job placements were found through online searches.

Nevins finalists have consistently enjoyed strong academic placements. Roughly one-quarter obtained tenure-track positions in top-40 U.S. departments, and more than half placed in ranked departments. These outcomes are similar to the placements of graduates from the best U.S. economics departments. For example, Oyer (Reference Oyer2006) found that between 1980 and 2002, roughly half of the graduates from top-7 economics departments placed in ranked tenure-track positions, while 30 percent placed in top-50 international departments.

Figure 1 shows no clear trends in placements over time. This is somewhat surprising, given the marked changes in the overall job market for new PhDs, and the standing of economic history within the profession. If anything, recent cohorts of finalists have enjoyed slightly better job outcomes. For example, more than 70 percent of post-2010 graduates have placed in ranked departments, as compared to less than 50 percent in the previous three decades. These patterns align with broader trends in the visibility of economic history research in recent years (Abramitzky Reference Abramitzky2015).

Where do Nevins finalists come from? Figure 2 presents the graduate schools that have produced multiple Nevins finalists. I split the sample into two equal-sized groups of finalists: those graduating from 1973–1996 and those graduating from 1997–2022.Footnote 3

Figure 2 SCHOOLS THAT PRODUCED MULTIPLE NEVINS FINALISTS

Notes: Multiple schools* with two Nevins finalists from 1973–1996 include Columbia, Harvard, MIT, UC Davis, UCLA, and UNC Chapel Hill. Multiple schools** with two Nevins finalists from 1997–2022 include Columbia, LSE, Michigan, Pittsburgh, UC Davis, and Yale.

Sources: Finalists were retrieved from various issues of the Journal of Economic History.

In both time periods, finalists are disproportionately drawn from a handful of departments. Interestingly, while the two distributions look similar, the composition of schools has shifted. Early on, the top Nevins-producing schools were Chicago, Stanford, Illinois, and Washington. More recently, schools like UCLA, Northwestern, Harvard, and Arizona have produced a disproportionate share of finalists.

Sifting through the volumes of the Journal, I was struck by how many recent dissertation summaries thanked advisors who themselves were past Nevins finalists. Indeed, although I do not have a clever instrument, I suspect the data would show a strong correlation between the placement schools of past Nevins finalists and the PhD-granting schools of subsequent cohorts. This is not surprising, given the longstanding tradition within the Economic History Association of supporting research by graduate students. Today we welcome three new researchers into the field. I am sure they will contribute, not just through their research but also by continuing to foster and mentor younger cohorts of students in economic history.

It is a great honor to present the candidates for the 2022 Allan Nevins Prize. I received ten submissions for the prize. The quality of the dissertations was outstanding, which made my task especially difficult. Nevertheless, the three finalists stood out. Let me briefly discuss their work.

JINGYI HUANG

Jingyi Huang’s dissertation is titled “The Impact of Innovation, Regulation, and Market Power on Economic Development: Evidence from the American West.” It is an impressive study of interrelated issues in the development of the American West. In the first chapter, Huang explores the impact of the refrigerated rail car on American agriculture. This invention saved substantial shipping costs for livestock, and reduced the risk of weight loss or animal death during transport. Her empirical analysis exploits differences across counties in suitability for livestock versus grain production. Huang finds that the introduction of refrigerated rail cars caused agricultural production to shift towards areas more suitable for ranching that persisted for decades.

These are interesting findings that add to our understanding of the influence of innovation in American agriculture. Whereas previous research has focused primarily on the aggregate impacts of railroads (i.e., Fogel Reference Fogel1964; Donaldson and Hornbeck Reference Donaldson and Hornbeck2016), this paper highlights how refrigeration altered comparative advantage to reshape the geographic patterns of agricultural activity. Given that the potential gains from this technology depend not just on underlying land suitability, but also on proximity to markets, I would encourage Huang to delve more deeply into the sources of these geographic patterns.

Huang’s second chapter is a detailed exploration of Chicago’s meatpacking industry in the early twentieth century. Farmers shipped livestock to be sold to a group of five meatpackers, who openly colluded to manipulate wholesale prices. Huang highlights a fascinating, dynamic element to this collusion. Given lags in shipment, farmers had to pre-commit to sell before observing the spot price, and so were vulnerable to dynamic price manipulation. Huang documents this market collusion through both narrative evidence and descriptive statistics based on weekly price data from the major stockyards.

To estimate the costs of dynamic market collusion, Huang exploits a change in the regulatory environment that caused the cartel to stop holding their weekly price-fixing meetings. Although they could still manipulate markets through static collusion, the cartel could no longer coordinate dynamic pricing. Applying a structural model, she compares outcomes across both regimes to quantify the additional costs associated with dynamic price collusion. She finds that dynamic market manipulation hurt farmers through lower wholesale cattle prices, and imposed significant costs on downstream consumers through higher food prices. This chapter provides an example of first-rate economic history that speaks to current policy, particularly in developing countries, where small rural producers often enter relationships with a handful of powerful buyers.

In her final chapter, Huang assembles county-level data on nineteenth-century fence laws across a number of western states to study how the assignment of liability rules affects resource allocation. She compares “fence out” laws, which assign responsibility to farmers to protect land from livestock incursion to “fence in” laws, which assign responsibility to ranchers. In contrast to Ronald Coase’s (1960) classic paper, her empirical results suggest that the assignment of property rights did, in fact, influence agricultural outcomes.

PAWEL JANAS

The title of Pawel Janas’s dissertation is “Financial Crises and Growth: U.S. Cities, Counties, and School Districts during the Great Depression.” I must admit that when I first read this title, I was skeptical. Given the extensive literature on the Depression, I thought, what more can be learned? I was wrong. Janas provides many fascinating new insights into this historical episode, drawing on an impressive array of novel data sources.

In Chapter 1, Janas investigates how local governments responded to the decimation of their revenue base during the Great Depression. Drawing on newly collected data on city spending and municipal bonds, Janas compares changes in spending outcomes across more or less leveraged cities during the Depression. He also implements a novel strategy based on the timing of bond due dates to compare outcomes across cities with similar debt levels, that were more less exposed to debt repayment during the Depression. Janas finds that financially constrained cities faced downgraded credit ratings during the Depression, and were forced to make significant cuts across a broad category of public spending. Beyond the headline findings, the detailed spending data allow Janas to provide a first-ever in-depth portrait of the operations of local governments through this unique period of financial distress.

In his second paper, Janas studies how adolescents educational choices were affected by the Great Depression. There is a sizeable literature on the elasticity of schooling choices with respect to youth labor market opportunities (e.g., Atkin Reference Atkin2016; Baker, Blanchette, and Eriksson Reference Baker, Blanchette and Eriksson2020). Nevertheless, Janas highlights another mechanism at play during the Depression: the sharp drop in school funding temporarily reduced school quality, potentially lowering the incentive to stay in the classroom. Drawing on several new data sources, Janas provides convincing empirical evidence that the Depression did increase overall educational attainment, but that this effect was partially offset by worsening educational quality. Exploring how educational choices were influenced by within-household dynamics, such as parental job loss or migration, might be an interesting extension of the current analysis.

In his third chapter, Janas studies the role of the Atlanta Fed in affecting local access to credit and economic outcomes by acting as a lender-of-last-resort. His empirical strategy follows prior work (Richards and Troost 2009; Ziebarth Reference Ziebarth2013), but he brings several new sources of data, including county-level measures of pre-Depression financial constraints. He confirms the relationship between Fed policies and local credit conditions that has been documented by other researchers, but finds no evidence that the Atlanta Fed’s policies improved local economic outcomes. These are interesting and surprising findings. As he continues this line of research, I would like to see him delve more deeply into understanding why his results diverge from the prior literature.

SEBASTIAN OTTINGER

Sebastian Ottinger’s dissertation, “Essays on Political Economy and Economic Geography,” is made up of three distinct papers, two of which address fundamental questions in American economic history, while the third focuses on Europe. In the first chapter, Ottinger studies the role of immigrants in shaping the geographic patterns of American economic activity. In doing so, he links two seemingly distinct historical phenomena: the massive inflow of foreign workers during the Age of Mass Migration and the rise of the U.S. manufacturing belt. He motivates the analysis with several case studies, describing the role of immigrant entrepreneurs in establishing local hubs of economic activity.

His empirical analysis is based on the insight that immigrants arrive endowed with different skills depending on their country of origin. He assembles data on comparative advantage across 49 manufacturing industries in 13 European origin countries to capture the “embodiment” of skills among new arrivals. Exploiting the unequal spatial distribution of different immigrant groups across U.S. counties in 1850, he then explores how differences in this measure of “immigrant specialization” affected the geographic patterns of industrial development in the latter nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Ottinger finds that the comparative advantage embodied in new immigrants predicts the growth in specific local manufacturing industries in subsequent decades. The early establishment of these industries persisted until well into the twentieth century, potentially due to agglomeration forces that locked in an early advantage. Interestingly, he also finds evidence that greater “immigrant specialization” predicts the entry of pioneer firms into a particular county-industry, and that these new firms were disproportionately owned by immigrants.

This is fascinating research that demonstrates the critical role of immigration in the emergence of the U.S. manufacturing belt. His work also highlights the contingent nature of economic history, which, in this case, depended on the particular destination choices of millions of new arrivals to the country.

In his second paper, coauthored with Max (Winkler) Posch, Ottinger studies how local political leaders responded to the political threat of the formation of new coalitions with minority groups. They study the short-lived electoral success of the Populist Party in the 1892 presidential elections, who sought support from both poor White and Black farmers, threatening the Democratic establishment in the South. Using archival newspaper data, Ottinger finds that Democratic leaders responded to this political threat through anti-Black propaganda. The effects are particularly large in counties with high levels of wealth inequality, where elites presumably have more to lose from redistributionist policies. Sadly, it appears that this propaganda was effective, as it contributed to persistent gains for Democrats in subsequent elections. Overall, I think this work provides important new insights into the determinants of racism and political repression of African Americans in the Postbellum South.

Joshua Lewis, Université de Montréal

REFERENCES

Abramitzky, Ran. “Economics and the Modern Economic Historian.” Journal of Economic History 75, no. 4 (2015): 1240–51.

Atkin, David. “Endogenous Skill Acquisition and Export Manufacturing in Mexico.” American Economic Review 106, no. 8 (2016): 2046–85.

Baker, Richard B., Blanchette, John, and Eriksson, Katherine. “Long-Run Impacts of Agricultural Shocks on Educational Attainment: Evidence from the Boll Weevil.” Journal of Economic History 80, no. 1 (2020): 136–74.

Boustan, Leah. “Summaries of Doctoral Dissertations.” Journal of Economic History 75, no. 2 (2015): 531–62.

Coase, Ronald H. “The Problem of Social Cost.” Journal of Law and Economics 3 (1960): 1–44.

Donaldson, Dave, and Hornbeck, Richard. “Railroads and American Economic Growth: A “Market Access” Approach.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 131, no. 2 (2016): 799–858.

Fogel, Robert W. Railroads and American Economic Growth: Essays in Econometric History. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1964.

Oyer, Paul. “Initial Labor Market Conditions and Long-Term Outcomes for Economists.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 20, no. 3 (2006): 143–60.

Richardson, Gary, and Troost, William. “Monetary Intervention Mitigated Banking Panics during the Great Depression: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from a Federal Reserve District Border, 1929–1933.” Journal of Political Economy 117, no. 6 (2009): 1031–73.

Ziebarth, Nicolas L. “Identifying the Effects of Bank Failures from a Natural Experiment in Mississippi during the Great Depression.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 5, no. 1 (2013): 81–101.

The Impact of Innovation, Regulation, and Market Power on Economic Development: Evidence from the American West

This dissertation is an empirical analysis of how the interaction between innovation, market power, and regulation reshaped the American West between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. American agricultural production experienced drastic technological change and regulatory shifts during this period. I focus on the long-term effect of mechanical refrigeration on agriculture productivity, how this innovation influenced market power in the meatpacking industry, and finally, the influence of liability rules on agricultural land use and livestock production. The evolution of technology, market structure, and legal frameworks in the past century provides a valuable angle to understand current policy challenges.

LONG-TERM EFFECT OF MECHANICAL REFRIGERATION ON U.S. AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION

Despite the historical importance of refrigeration, few studies have empirically analyzed its long-term impact on American agriculture. Prior to refrigerated rail cars, livestock needed to be transported alive from farms to urban markets to be slaughtered and sold. The transportation process was costly and risked animals losing weight or dying on the trip. In 1880, meat packers in the Midwest acquired the patent to build the first refrigerated rail car. The invention significantly reduced the shipping cost of beef: carcasses could be shipped for one-third the cost of shipping live cattle. Within ten years, from 1880 to 1890, the number of cattle slaughtered in Chicago more than quadrupled, and the meatpacking industry became the second-largest manufacturing sector in terms of output value.

The research design exploits the variation in relative natural suitability for livestock versus grain production across counties to capture the impact of refrigeration. Perishable goods, such as beef, experienced a drastic reduction in transportation costs after 1880. Meanwhile, this change did not influence other non-perishable products, such as wheat. In other words, counties more suitable for livestock production were more influenced by the new technology, thus allowing an event-study analysis that compares changes in counties more or less suitable for livestock production before and after 1880.

The event study shows that after 1880, when refrigeration was commercially adopted in the meatpacking industry, counties that were relatively more suitable for ranching than farming witnessed more farmland development and higher output value. For every percentile increase in the relative suitability ranking, counties experienced a 0.1 percentage point increase in the share of land areas being developed as farmland and a 0.5 percent increase in output value and land value. The effects also differ for counties across the range of relative suitability but persist over time. The results were driven primarily by the top two quartiles, but the impact on output and land value persisted until 1960.

MONOPSONY, CARTELS, AND MARKET MANIPULATION: EVIDENCE FROM THE U.S. MEATPACKING INDUSTRY

In addition to shifting upstream agricultural production, how does the new technology affect market power and the competition structure in the manufacturing sector? In this chapter, I answer this question by analyzing the American meatpacking industry in the early twentieth century.

Due to the high fixed costs, mechanical refrigeration created a few firms with unprecedented market power in the meatpacking industry. By the early twentieth century, five firms dominated the meatpacking industry. Under weak antitrust enforcement, they formed a monopsonistic cartel to manipulate the wholesale cattle market. The cartel dominated both the input market (cattle) and product market (beef): the five packers purchased 95 percent of cattle sold at the ten largest stockyards and produced more than 80 percent of refrigerated beef for urban markets. In an era of weak antitrust enforcement, they openly colluded to manipulate the wholesale cattle market from 1893 to 1920.

Standard monopsony models focus primarily on static and immediate responses to cartel strategies. However, for markets with substantial time to ship or time to build, current market outcomes may influence future supply decisions and thus make sellers vulnerable to a more complex form of dynamic manipulation. Because sellers must make future production or shipment decisions based on current market information, they must commit to the market before observing the realized spot market price at the time of delivery. If a monopsonistic cartel incorporates the delayed supply responses in the collusive strategy, the canonical static model may fail to properly assess the cartel damage on the market.

Two factors make this historical case particularly well suited to examining the effect of a dynamic monopsonistic cartel strategy. First, because the cartel was eventually challenged in court, the resulting litigation created detailed documentation on the cartel’s manipulation strategies. The court found that the cartel members were guilty of “bidding up through their agents, the prices of livestock for a few days at a time, to induce large shipments, and then ceasing from bids, to obtain livestock thus shipped at prices much less than it would bring in the regular way.” Second, exogenous changes in the regulatory environment forced the cartel to switch from the aforementioned dynamic strategy to a static, fixed market share agreement in 1913, while other features of the market remained unchanged. Thus, I observe the market outcomes under both dynamic and static strategies, but with the same market participants. This allows me to compare the empirical outcomes under the dynamic strategy to counterfactuals suggested by the well-understood static monopsony model.

The main analyses leverage exogenous regulatory changes that forced the cartel to switch from dynamic to static strategies. I first construct and estimate a static model of the cattle wholesale market using data after 1913, when the cartel strategy coincided with the static model. I then use the estimated static model to solve for market outcomes for the dynamic period before 1913. This recovers the counterfactual cattle wholesale prices and cartel quantities as well as downstream wholesale beef prices. The difference between the observed market outcomes under the dynamic strategy and the counterfactuals suggested by the static model is, therefore, the “additional” damage of the dynamic cartel strategy not captured by standard models.

I find two sets of key results. First, regarding the wholesale cattle market, the dynamic strategy causes more damage to small sellers than what is suggested by the standard model. Without cartel manipulation, the average cattle wholesale price would increase by 23.4 percent, which would increase the profit margin by 57 percent for the sellers. The average total quantity purchased by the cartel would also increase by 14 percent, or 15,000 more heads of cattle per week sold at the four stockyards. Second, regarding the downstream wholesale beef market, the dynamic strategy hurts urban consumers by reducing the beef supply and increasing household food expenditure. However, the effects are much smaller: without cartel manipulation, downstream wholesale beef prices would reduce by 6 percent, and total household food expenditures would reduce by $3.6 per year.

FENCE LAWS: LIABILITY RULES AND AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTIVITY

This chapter uses the historical evolution of fence laws in the American West to analyze the long-term effect of liability rules on resource allocation and productivity. In his seminal article, Coase (Reference Coase1960) uses an example between a farmer and a cattle-raiser adjacent to each other to illustrate that the assignment of property damage liability does not affect the allocation of resources. Cattle may stray and destroy the crops on the farmer’s land. Regardless of whether the farmer or the cattle-raiser is legally liable for the trespassing damage, the land allocation between the two types of production should reach the same equilibrium, as long as the liability is well-defined and enforced, and the transaction is costless. However, despite the wide application, most research focuses on the effects of establishing and enforcing property rights. Few empirical works study how the assignment of property damage liability may influence resource allocation.

In the American West, counties assign the liability of protecting against animal trespassing to either farmers or ranchers. Under the “fence-out” rule, farmers can claim damage from owners of the trespassing animals only if they have enclosed the land with fences that satisfy specific regulatory requirements. Meanwhile, under the “fence-in” rule, farmers can claim damage from livestock owners regardless of whether the farms are enclosed with fences. In other words, the liability for livestock trespassing is assigned to farmers in some areas and livestock owners in others. Ranchers and farmers have long contested fence regulations. Prolonged public debates and occasional violent conflicts between farmers and ranchers suggest that this supposedly innocuous rule had profound economic implications.

I compiled data on all county-level fence-related regulation changes from the first state (or territorial) legislature until 1930. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first dataset that fully captures the legal environment for property rights protection during this period. I combine the fence law data with the decennial censuses, measuring land use, land value, output value, and productivity over the past century. This data provides a comprehensive legislative history of liability rules for the western states.

The analysis exploits the county-level fence laws variation over time to quantify the effects of liability rules on agricultural productivity. Consistent with historical accounts, the baseline difference-in-differences results show that fence-in rules incentived agricultural development. Compared to fence-out counties that required farmers to construct fences, the fence-in law increased the density of farmland and the share of improved farmland. By making ranchers liable for trespassing damages, the fence-in rule also increased grain cultivation area. This eventually translates to a higher total value of farm output for fence-in counties, although the higher productivity was not reflected in land values.

CONCLUSIONS

With newly constructed historical data and clear identification strategies, this dissertation provides new causal evidence on the persistent impact of innovation and regulation. It quantifies the long-term economic impact of some of American history’s most important technological and regulatory changes. The results also expand our understanding of the interaction between innovation and regulation and how they can influence market structure and economic development. First, mechanical refrigeration benefited upstream agricultural production, especially in places relatively more suitable for ranching. Meanwhile, the high fixed cost of the new technology also created a highly concentrated market, resulting in welfare losses for both small suppliers and consumers. Finally, while antitrust laws improved welfare by restricting market manipulation, other seemingly innocuous regulations, such as the fence laws, created persistent resource misallocation.

Jingyi Huang, Brandeis University

Jingyi Huang, Assistant Professor, Brandeis University, Lemberg Academic Center, MS 021, Brandeis University, 415 South Street, Waltham, MA 02453. E-mail: [email protected]. This dissertation was completed at the University of California, Los Angeles under the supervision of Dora Costa (co-chair), John Asker (co-chair), Michela Giorcelli, and Nico Voigtländer.

REFERENCE

Coase, Ronald Harry. “The Problem of Social Cost.” Journal of Law and Economics 3 (1960): 1–44.

Financial Crises and Economic Growth: U.S. Cities, Counties, and School Districts during the Great Depression

I study the impact of financial frictions on local public good provision and economic activity during the Great Depression in the United States. To date, research has shown that the fragility of households and firms during crises is an important determinant of their outcomes: highly indebted households and firms with fractured creditor relationships seem to bear the brunt of recessions (Chodorow-Reich Reference Chodorow-Reich2014; Mian, Rao, and Sufi Reference Mian, Rao and Sufi2013). Yet, leveraged local governments have received much less attention, despite the vast size of the municipal bond market and the economic importance of local public services.

PUBLIC GOODS UNDER FINANCIAL DISTRESS

In the first chapter of my dissertation, I ask: when faced with financial constraints during a crisis, how much do municipalities adjust local public goods, and how much of this curtailment is due to financial market frictions?

I shed new light on these questions by studying how U.S. cities responded during the Great Depression. Building upon the work of Siodla (Reference Siodla2020), I construct a historical dataset of local public good provision and debt from multiple archival sources on U.S. cities. I also supplement the city-level data with a second database of over 29,000 municipal bonds outstanding in 1929. To estimate the impact of leverage on local public good provision, I compare expenditure in more or less leveraged cities before and after the onset of the Great Depression using a difference-in-differences framework. I find that municipalities in the 75th percentile of pre-Depression leverage saw a 5 percentage point decrease across current expenditures and a 15 percentage point decrease in capital investment relative to cities in the 25th percentile. I find a significant effect on police and firefighting spending and capital investment and quantitatively smaller but significant effects on the other categories, such as health and sanitation.

I then unpack financial leverage into two distinct mechanisms: a causal refinancing supply-side channel and a non-causal demand-side channel. I study the refinancing channel by exploiting the quasi-exogenous timing of bonds becoming due right after the financial market crash of 1929, which led to a collapse of bond markets in the early 1930s (Hillhouse Reference Hillhouse1936). As a result, municipalities could not easily issue new debt to repay the principal owed on bonds that were becoming due during this time, and cities with more of these outstanding bonds were plausibly more constrained in allocating revenue between debt service and public goods. These bonds, however, were primarily issued well in advance of the onset of the Depression, such that the specific timing of these debt-repayment shocks was unlikely to be driven by the demand for new investment during the Depression (Almeida et al. Reference Almeida, Campello, Laranjeira and Weisbenner2009; Benmelech, Frydman, and Papanikolaou Reference Benmelech, Frydman and Papanikolaou2019).

I find that cities with more debt that matured during the Depression curtailed public good provision on capital investment and public service expenditure more than similar cities that did not face the same financial shock. Specifically, one standard deviation in the amount of bonds due is associated with a decline in current spending and capital investment of about 2.5 and 20 percent, respectively. Altogether, these results suggest that roughly 20 percent of the drop in expenditure can be explained through a re-allocation of budgets towards debt repayment. The lack of infrastructure demand from highly leveraged cities, on the other hand, can account for some of the leverage effects in the early years of the Depression but only a small portion of it after 1933. My findings suggest that financial market frictions played a significant role in the decrease in local public goods during the Great Depression in the United States.

CRISES AND INTERGENERATIONAL MOBILITY

In the second chapter of my dissertation, I shift my attention to the impact of reducing one particular public good during the Depression: public education. Specifically, I study the schooling behavior and intergenerational mobility of young urban males in the United States during the 1930s. Broadly, education is one mechanism through which younger generations climb the socioeconomic ladder and sever intergenerational links in economic outcomes—understanding the interaction between macroeconomic shocks and microeconomic mechanisms driving changes in human capital investment is essential for guiding education and labor policy (Goldin and Katz Reference Goldin and Katz1997; Black, McKinnish, and Sanders Reference Black, McKinnish and Sanders2005; Cascio and Narayan Reference Cascio and Narayan2015; Kerwin, Hurst, and Notowidigdo Reference Kerwin, Hurst and Notowidigdo2018). In this chapter, I take advantage of the decentralized public education system of the United States in the 1930s to study how schooling decisions are affected by changes in education quality and the opportunity cost of youth labor. When a crisis hits, do differences in quality and opportunity costs at the local level result in varying levels of educational attainment and, ultimately, intergenerational mobility? If so, who are the winners and losers of crises?

I study these questions by merging newly collected local data on youth unemployment and school quality during the Depression with linked full-count Census records (Abramitzky, Boustan, and Rashid Reference Abramitzky, Boustan and Rashid2020). First, I collect unemployment-by-occupation-by-age data from the Special Unemployment Census of 1931. Since the Unemployment Census canvassed only 18 regionally dispersed cities and 3 boroughs of New York City, I create estimates of youth unemployment for all other cities by taking a weighted average of regional youth unemployment-by-occupation rates, using 1930 occupation-by-city shares aggregated from the 1930 complete count Census as weights. Then, to obtain education quality measures, I digitize biennial records from the Census of Education from the U.S. Office of Education on revenues and expenditures at the city level from 1922 to 1938. I follow the economics of education literature and proxy quality with the change in the total real spending per pupil. I show that expenditure is closely related to the student-teacher ratio, average real teacher wages, and school term length.

My empirical strategy attempts to explain the within-city variation in high school graduation rates across cohorts using a difference-in-differences design using across-city variation in unemployment and public education spending cuts. The strategy thus compares the education outcomes of individuals on the cusp of making secondary schooling decisions during the Great Depression with those who graduated before the Great Depression within the same city, conditional on national trends and static city determinants of educational attainment.

I find that increases in the youth unemployment rate in 1931 significantly increased secondary school graduation rates: one standard deviation (4 percent) increase in unemployment caused a 1.2–1.6 percentage point increase in the graduation rate for the Depression-era cohorts and 0.9–0.12 more years of schooling. On the other hand, cuts in education spending decreased graduation rates by about a quarter of this effect. To put these numbers in perspective, I find that youth unemployment can account for 18–21 percent of the total increase in high school graduation during the 1930s, while education spending cuts attenuated this effect by 4–5 percent.

LENDER OF LAST RESORT AND LOCAL ECONOMIC OUTCOMES

In the last chapter of my dissertation, I focus on banking panics and local manufacturing activity. I use archival panel data on local manufacturing and banking conditions in the United States to investigate the link between policy, bank failures, and firm production and employment. I use the divergent policies enacted by the Atlanta Federal Reserve Bank, first brought to the literature by Richardson and Troost (Reference Richardson and Troost2009) with additional contributions by Jalil (Reference Jalil2014) and Ziebarth (Reference Ziebarth2013), as my empirical laboratory. Unlike the other Federal Reserve banks at the time, Atlanta acted as a lender of last resort inside its region by extending credit to solvent but illiquid banks to prevent bank runs.

Because the Federal Reserve borders bisect states and consumer markets, I can compare the local economic trajectories before and during the Great Depression using the quasi-exogenous incidence of bank failures.

In the first part of my analysis, I investigate the difference in bank failures between counties just outside the Atlanta border and those just inside it and explore its robustness. I find that banks failed less often inside the Atlanta region in 1929 and 1930, even after accounting for pre-existing differences in local banking conditions, excluding outliers and individual border segments, and measuring bank distress in various ways. I perform placebo randomization tests of the Federal Reserve’s borders and find that the baseline results are unlikely to have occurred by chance. Additionally, I do not find much evidence that bank distress differed across the borders of Federal Reserve districts that did not follow different lender-of-last-resort policies. The results, taken together, suggest that credit conditions were more favorable in the early years of the Depression in the counties of the Atlanta district.

I turn to local manufacturing outcomes in the second part of my analysis. By combining an industry-level credit survey with pre-Depression industry-by-county data, I construct proxies for the financial constraints of small and medium-sized manufacturers in each county around the Atlanta region border. The survey shows that most of these manufacturers relied on commercial banks to finance both working capital and long-term investment, but the degree of these constraints varied by industry. By exploiting the geographical differences in the types of manufacturing along the Atlanta border, I compare economic activity across counties with fewer and more banking failures. Since commercial banks survived at a higher rate inside the Atlanta region, I hypothesize that manufacturing output and employment shrank less and recovered quicker there than in counties just outside the Atlanta region. Furthermore, I test whether the results are strongest for counties with firms in highly constrained industries.

I do not find evidence to support this hypothesis, which contrasts with the results of the existing literature. First, manufacturing outcomes were worse, not better, in counties inside the Atlanta region, despite having more banking resources. Second, I find evidence that the county-level financing constraints, on average across all counties, predict worse outcomes after, but not before, the Depression. Yet, the combination of pre-Depression measures of financial constraints and banking panics during the Depression was not an important determinant of local economic outcomes, as one might expect. Even though the Atlanta Federal Reserve’s policies strengthened the banking sector early in the Depression, there was no positive downstream effect on firms, possibly due to the banking sector’s reluctance to extend credit.

Pawel W. Janas, California Institute of Technology

Pawel W. Janas, Assistant Professor, California Institute of Technology, 135 Baxter Hall, MC 228-77, Pasadena CA 91125. E-mail: [email protected]. This dissertation was completed at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern University under the supervision of Paola Sapienza, Carola Frydman, Joel Mokyr, and Scott Baker.

REFERENCES

Abramitzky, Ran, Boustan, Leah, and Rashid, Myera. Census Linking Project: Version 1.0 [dataset], 2020.

Almeida, Heitor, Campello, Murillo, Laranjeira, Bruno, and Weisbenner, Scott. “Corporate Debt Maturity and the Real Effects of the 2007 Credit Crisis.” NBER Working Paper No. 14990, Cambridge, MA, May 2009.

Benmelech, Efraim, Frydman, Carola, and Papanikolaou, Dimitris. “Financial Frictions and Employment during the Great Depression.” Journal of Financial Economics 133, no. 3 (2019): 541–63.

Black, Dan, McKinnish, Terra, and Sanders, Seth. “The Economic Impact of the Coal Boom and Bust.” Economic Journal 115, no. 503 (2005): 449–76.

Cascio, Elizabeth U., and Narayan, Ayushi. “Who Needs a Fracking Education? The Educational Response to Low-Skill-Biased Technological Change.” ILR Review 75, no. 1 (2015): 56–89.

Chodorow-Reich, Gabriel. “The Employment Effects of Credit Market Disruptions: Firm-Level Evidence from the 2008–9 Financial Crisis.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 129, no. 1 (2014): 1–59.

Goldin, Claudia, and Katz, Lawrence F.. “Why the United States Led in Education: Lessons from Secondary School Expansion, 1910 to 1940.” NBER Working Paper No. 6144, Cambridge, MA, August 1997.

Hillhouse, Albert M. Municipal Bonds: A Century of Experience. New York: Prentice-Hall, Incorporated, 1936.

Jalil, Andrew J. “Monetary Intervention Really Did Mitigate Banking Panics during the Great Depression: Evidence along the Atlanta Federal Reserve District Border.” Journal of Economic History 74, no. 1 (2014): 259–73.

Kerwin, Kofi C., Hurst, Erik, and Notowidigdo, Matthew J.. “Housing Booms and Busts, Labor Market Opportunities, and College Attendance.” American Economic Review 108, no. 10 (2018): 2947–94.

Mian, Atif, Rao, Kamalesh, and Sufi, Amir. “Household Balance Sheets, Consumption, and the Economic Slump.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 128, no. 4 (2013): 1687–726.

Richardson, Gary, and Troost, William. “Monetary Intervention Mitigated Banking Panics during the Great Depression: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from a Federal Reserve District Border, 1929–1933.” Journal of Political Economy 117, no. 6 (2009): 1031–73.

Siodla, James. “Debt and Taxes: Fiscal Strain and US City Budgets during the Great Depression.” Explorations in Economic History 76 (2020): 101328.

Ziebarth, Nicolas L. “Identifying the Effects of Bank Failures from a Natural Experiment in Mississippi during the Great Depression.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 5, no. 1 (2013): 81–101.

Essays on Political Economy and Economic Geography

Can historical accidents explain regional specialization in manufacturing? Can politics be a source of hateful media content? Did national leaders before Napoleon matter? These are the questions in the fields of economic geography and political economy that I study in the three chapters of my dissertation. Throughout, historical settings provide quasi-experimental variation to identify causal effects.

IMMIGRANTS, INDUSTRIES, AND PATH DEPENDENCE

Manufacturing industries cluster in space. Examples abound—in the past and present, in the United States and elsewhere. Detroit emerged as the nation’s center of the automobile industry and remains so today. In the twentieth century, San Francisco Bay became “Silicon Valley.” In the twenty-first century, Shenzhen—on a bay on the other side of the Pacific—became a global center of smartphone production. Jena, a medium-sized city in eastern Germany, arose as a center of the optics industry in the nineteenth century and remains so today.

Why do specific manufacturing industries end up clustering in particular regions? Economists have advanced three explanations and tested two empirically. The first emphasizes the natural resources of an area that might render it particularly suitable for specific industries. Second, a region’s market access to consumers and suppliers of crucial inputs might do so as well. However, while these explanations can account to some extent for why particular regions specialize in specific industries, a considerable amount of regional specialization remains unexplained by both. A third, hitherto untested explanation is commonly advanced in a diverse plethora of case studies for specific industries (Krugman Reference Krugman1992), supported by established economic theory (Arthur Reference Arthur1990). Take two identical regions. Suppose, randomly, one of them gets an early start in a particular industry, and agglomeration forces are sufficiently strong. In that case, this region will emerge as a center of that industry and remain so. Co-agglomeration of industries along this industry’s supply chain further cements the “lock-in” of this industry there. However, empirical evidence supporting these theories and anecdotal accounts is scarce.

In the first chapter of the dissertation, I provide such empirical evidence, leveraging the co-occurrence of two major developments in U.S. economic history in the nineteenth century. From this century on, the United States emerged as the most technologically advanced nation in the world, with a high degree of geographic specialization across its regions. Simultaneously, the United States attracted large numbers of immigrants from all over Europe. I create a measure of the potentially embodied industries of early or later immigrants that affect local employment patterns. This measure, henceforth immigrant specialization, combines the settlement patterns of all European origins in 1850 with the immigrants’ origin specialization in all manufacturing industries based on their international trading patterns.

Immigrant specialization was a significant, sizable, and robust factor in employment patterns across U.S. counties in the early twentieth century, holding fixed initial employment patterns as of 1850, as well as other well-documented determinants of local specialization, such as market access or natural resource endowments. This baseline association is stronger in the novel industries of the Second Industrial Revolution and for immigrants from Germany, which was emerging as an industrial powerhouse in those industries only after 1850.

I show that this was more than an episode of immigrants bringing their industries immediately. Rather, early immigrants induced local specialization through exchange with their origins after arrival and by attracting later immigrants. Several pieces of evidence support this. First, the baseline association is even stronger for some industries that did not exist by 1850, such as electrical manufacturing or the auto industry. Second, on the frontier of settlement around 1850, the association between immigrant specialization and employment patterns is negative, indicating, if anything, negative selective migration to those counties. An instrumental variable strategy based on the movement of the frontier and the aggregate arrivals of European origin in the prior decade supports this. So does the historical record. Early immigrants to this frontier mainly were farmers, and major cities and industry specialization in these only formed decades after 1850.

The rich data available in the complete count census allows me to provide direct evidence for the mechanism underlying the baseline association of how early immigrants induced local specialization. To do this, I identify the pioneer entrepreneurs in each county and industry, that is, the first individual recorded as an owner or manager in a particular industry for each county. Immigrant specialization predicts the pioneers’ entry, mostly after 1880. Their early entry helped select equilibria in county industries, shaping their destinations’ specializations for generations.

The traces of the early immigrants can still be found in specialization patterns today. Immigrant specialization remains a strong predictor of employment patterns in 2000 for those industries that emerged after 1850, particularly on the frontier of settlement then, where early immigrants found a tabula rasa and had the most opportunity to imprint local specialization.

This paper exploits only one of potentially many shocks that might lead some locations to have an early start in an industry and build their comparative advantage in those to form a cluster. It lends direct empirical support to the importance of such early shocks and subsequent path dependence in shaping regional specialization in manufacturing.

THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF PROPAGANDA: EVIDENCE FROM U.S. NEWSPAPERS

The second chapter of the dissertation, co-authored with Max (Winkler) Posch, studies the origin of hateful media content, drawing on the U.S. South after Reconstruction.

The People’s Party, with its aim of redistributing from rich to poor, posed a threat to the Democratic establishment in the South. The Populists, as the People’s Party was known, too, remained ambiguous regarding their position on race. This provided the segregationist Democratic establishment in the South with an incentive to fan racial outrage to alienate white voters from the Populists.

We use text data from local newspapers to identify hateful anti-Black content and show that its prevalence increased after the 1892 Presidential election, at which the Populists first ran on a nationwide platform, and in counties in which the Populists likely gained votes at the expense of the Democrats.

Additional results suggest a strong political motive behind this increase, indicating that Democratic political elites supplied this hateful content to further their electoral prospects and remain in control of local politics. All of the increase is driven by newspapers affiliated with the Democrats, and triple-difference results document that even within counties where at least one Democrat-affiliated newpaper and other newspapers are available, this increase is present in Democrat newspapers only. On the other hand, we find no effect for independent newspapers, which should have (profitably) reacted to local swings in demand as well. This and a battery of other results suggest that political elites used newspapers affiliated with them to supply propaganda to split their competitors’ potential electorate.

While politics may remain a source of hateful media content in the present day and other contexts, the setting of the U.S. South after Reconstruction, with newspapers as tightly politically controlled media (Gentzkow et al. 2015), the lack of alternative media forms—since radio and TV had yet to be invented—and the fact that newspapers served highly local markets, offers an optimal testing ground for theories of divide and rule by elites for political gain (Glaeser Reference Glaeser2005).

HISTORY’S MASTERS: THE EFFECT OF EUROPEAN MONARCHS ON STATE PERFORMANCE

The third and final chapter of my dissertation, co-authored with Nico Voigtländer, is set in European economic history and studies the effect of national leaders on the performance of the states they govern. While scholars since the nineteenth century have pondered the importance of national leaders, economists have brought identification to this debate (Jones and Olken Reference Jones and Olken2005), exploiting the accidental deaths of modern heads of state. We turn to the historical leaders before Napoleon and advance a new identification strategy to identify the effect of national leaders’ cognitive ability on the performance of their states.

We create a novel reign-level dataset for European monarchs, covering all major European states between the tenth and eighteenth centuries. We document a strong positive relationship between rulers’ cognitive ability and state-level outcomes. To address endogeneity issues, we exploit the facts that (i) rulers were appointed according to hereditary succession, independent of their ability, and (ii) the widespread inbreeding among the ruling dynasties of Europe over centuries led to quasi-random variation in ruler ability. We code the degree of blood relationship between the parents of rulers, which also reflects “hidden” layers of inbreeding from previous generations. The “coefficient of inbreeding” is a strong (negative) predictor of ruler ability, and the corresponding instrumental variable results imply that ruler ability had a sizeable effect on the performance of states and their borders.

This supports the view that “leaders made history,” shaping the European map until its consolidation into nation-states. We also show that rulers mattered only where their power was largely unconstrained. In reigns where parliaments checked the power of monarchs, a ruler’s ability no longer affected their state’s performance. Thus, the strengthening of parliaments in Northern European states (where kin marriage of dynasties was particularly widespread) may have shielded them from the detrimental effects of inbreeding.

Sebastian Ottinger, Assistant Professor, CERGE-EI, a joint workplace of Charles University and the Economics Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences, Politickych veznu 7, 111 21 Prague, Czech Republic. E-mail: [email protected]. This dissertation was completed under the supervision of Nico Voigtländer, Christian Dippel, Paola Giuliano, and Romain Wacziarg at the Anderson School of Management, University of California, Los Angeles.

REFERENCES

Arthur, W. Brian. “‘Silicon Valley’ Locational Clusters: When Do Increasing Returns Imply Monopoly?” Mathematical Social Sciences 19, no. 3 (1990): 235–51.

Gentzkow, Matthew, Nathan Petek, Jesse M. Shapiro, and Michael Sinkinson. “Do Newspapers Serve the State? Incumbent Party Influence on the US Press, 1869–1928.” Journal of the European Economic Association 13, no. 1 (2015): 29–61.

Glaeser, Edward L. “The Political Economy of Hatred.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 120, no. 1 (2005): 45–86.

Jones, Benjamin F., and Olken, Benjamin A.. “Do Leaders Matter? National Leadership and Growth since World War II.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 120, no. 3 (2005): 835–64.

Krugman, Paul. Geography and Trade. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992.

The Dissertations of Hanzhi Deng, Victoria Gierok, and Mark Hup 2022 Alexander Gerschenkron Prize Competition

I begin with an overview of some key characteristics of the submissions for the 2022 prize and then discuss the process I used to narrow down the submissions to finalists and then to select the prize recipient. I then discuss each finalist’s dissertation in brief.

I received 24 valid dissertation submissions from graduates of economics, economic history, and history departments. The majority of dissertations came from institutions located in England, Europe, and the United States, but Europe is leading. Dissertations from U.S.-based institutions included several from history departments, with only four coming from U.S. economics departments. Nearly half (11) covered geographic areas of Europe and the United Kingdom. The next best-represented region was Asia (7), and an additional four explored international and comparative topics. Striking was the dearth of coverage of Africa and South America, with only one dissertation each.

The submissions covered a broad span of time periods—ranging from the late thirteenth to the twenty-first century—with nearly equal numbers exploring pre-industrial (7), nineteenth to early twentieth century (8), and post-World War I (7) topics. Two dissertations explored multiple or very long time periods. The range of topics was even more impressive and provided me with a “Summer Course on World Economic History Since 1282.” The non-exhaustive list includes the following examples: Economic and political causes and consequences of migration; entrepreneurship under Russian socialism; wealth inequality, poverty, inheritance, political power (multiple); state fiscal capacity and related political institutions (multiple); India’s caste system, income inequality, and social mobility; war reparations and sovereign debt; maritime rules, risk sharing, and trade in early modern Genoa (two); the role of regulation in banking and financial crises; communism, labor productivity, and economic efficiency; early modern globalization, empire, trade, and public debt; tropical agriculture, cash crops, globalization, and climate change; global currency unions and international monetary systems.

A couple of other patterns caught my eye: the gender breakdown and the extent of co-authorship of dissertation chapters. On the first topic, based largely on name identification and photos where names were not clearly gendered (to me), I found only 3 women in the pool of submissions, compared with 21 men. Given the gender breakdown in the economics profession and in the field of economic history more narrowly, I found this result surprising and concerning.

The other notable finding was the widespread practice of co-authorship in part and even in all of the dissertations submitted. Eleven candidates co-authored at least one chapter. Of those, five co-authored at least half of their dissertations, and one of those co-authored the entire dissertation. With the exception of one of the finalists, co-authored dissertations did not generally seem more complex or to involve substantially more involved data collection. Since the prize goes to an individual, I gave greater weight to the accomplishment of a sole-authored work.

THE CRITERIA

First off, it is important to emphasize that every dissertation submitted for the 2022 prize constituted a package of high-quality research and industrious efforts on the part of the candidates. For that, I congratulate each and every candidate. In order to begin to differentiate among the submissions, I set up a rubric of sorts and then rated each dissertation on a scale of 1 to 5.

My rubric assessed the originality of the topic or question being asked, the novelty of the data collection, empirical and analytical rigor, and quality of writing. I paid special attention to the demonstration of intellectual breadth and independent work and looked for dissertations that employed the methodological approaches of both economics and history and, preferably, would answer questions of wide interest. In other words, the ideal dissertation would be a sole-authored piece of work that took up an enduring dilemma or raised a new question that the field should be grappling with but has not. This model dissertation would then develop an integrated approach based on the latest methods from economics, combined with rich, historical, and institutional detail, and then proceed to unearth and analyze novel data sources. Indeed, it is a tall order to even conceive of such a dissertation, never mind execute it successfully. More than three of the dissertations submitted actually cleared this hurdle, but three of them stood out as truly outstanding examples of the best of what economic history research can offer.

THE FINALISTS

I give a very brief overview of the major contributions of each finalist’s dissertation, presented in alphabetical order.

Hanzhi Deng: A History of Decentralization: Fiscal Transitions in Late Imperial China, 1850–1911

Dr. Hanzhi Deng completed his doctorate in economic history at the LSE under the supervision of Prof. Kent Deng. Motivating Dr. Deng’s research is the long-standing, general question of state capacity, or the ability of governments to achieve policy goals, such as economic development and improving the well-being of the population. More narrowly, he wants to understand how China transitioned to a modernized fiscal state through evolving fiscal regimes. The originality of Dr. Deng’s dissertation comes in the re-framing of China’s political-economic development, particularly the causes and consequences of internal political and religious strife in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Encompassing seven chapters and two appendices, Deng’s dissertation helps us understand the role of and regional variation in local governments’ fiscal capacity and bureaucratic strength within a centralized, dynastic political system that was, at that time, relatively weak and struggling with political upheaval.

Dr. Deng begins the work with two chapters to set up the theoretical and historical contexts for his analysis. This careful attention to institutional details not only motivates the study for the reader but also allows him to improve the specification of his quantitative analysis. Then, using multifaceted, detailed, local-level data from novel sources, he employs multiple analytical approaches to grapple with causal relations.

In his first empirical analysis (Chapter 3), Deng studies the effects of the Taiping Rebellion of 1851–64 to understand the role of political disorder in fiscal state development and redirects the focus from the standard “Western” view to the impacts of indigenous shocks. He collects a prefectural-level dataset on the newly-created internal trade (“lijin”) taxation for 18 provinces, along with a detailed accounting of Taiping warfare, also by prefecture, on a monthly basis. The fascinating analysis of battles demonstrates dramatic cross-sectional and temporal variation in intensity. Deftly weaving together the evidence, Deng is able to elucidate the role of local governments and conclude that the unusual level of local autonomy granted by the Qing central court in the early 1850s created a “bottom-up” fiscal restructuring and led to significant expansion. Highlighting the incentives and informational advantages of local governments, Deng traces the rapid transformation from a centralized, land-based tax regime into a decentralized and flexible system based on goods production and trade.

Deng then explores additional modes of indirect taxation (Chapter 4), comparing domestic and maritime customs and highlighting the effect of the ongoing warfare on destroying customs infrastructure and leading to greater dependence on the lijin. Meanwhile, the loss of the Second Opium War led to a Western-run maritime customs system. Deng argues that this dual system improved efficiency and ultimately benefited fiscal balances compared to the old direct, land-based system. In the last two empirical chapters, Deng considers changing patterns of public borrowing (Chapter 5) and expenditures (Chapter 6), and connects the new, local orientation and control to a growing responsiveness and accountability in public goods provision and economic growth.

Deng’s collection of Late Qing era fiscal reports, in combination with data on indirect taxation, foreign borrowing, public spending, and local industrialization, as well as atlases of late Qing rebellions and wars, will form the basis for a range of ongoing studies and contribute much needed data for future researchers studying this turbulent period in Chinese history. Deng’s dissertation also contributes to the ongoing debates over the “fiscal Great Divergence” between China and Europe and, in so doing, demonstrates how China’s development of local fiscal capacity spurred industrialization. Given the ongoing debates over the “Great Divergence,” I anticipate that Hanzhi Deng’s novel contribution will make a lasting impression on the field.

Victoria Gierok: The Development of Wealth Inequality in the German Territories of the Holy Roman Empire, 1300–1800

Dr. Gierok completed her doctorate in history at Oxford University under the supervision of Stephen Broadberry. Her work contributes to an area of research, both long-standing and of increased recent interest, into the drivers of inequality and the relationship between inequality and economic growth. Based on a wealth of original data and spanning seven chapters and six appendices, Dr. Gierok’s dissertation provides a completely new understanding of patterns and drivers of inequality and poverty in Germany during the pre-industrial age. In the process, she adds to new research that extends and revises the patterns famously laid out by Simon Kuznets in his model of inequality over the arc of the industrial revolution (the so-called “Kuznets Curve”).

Gierok’s approach is to develop a ground-up characterization of wealth inequality and poverty rates—comparing rural versus urban—and to assess the impact of disease, war, gender discrimination, economic institutions (guilds), and fiscal extraction. As the core of the work, she develops two massive new databases (one collaborative) on household wealth taxes and municipal budgets. The household-level dataset covers more than 35 urban and over 100 rural communities at 25-year intervals between 1300 and 1850, amounting to over 100,000 observations. The city-level dataset covers over 30 city budgets. The samples represent the demographics and politics of pre-industrial Germany.

Dr. Gierok provides an extremely thorough institutional and statistical analysis, employing careful modeling of distributions and identifying causal influences. She provides several new insights into long-term patterns of poverty and wealth inequality in pre-industrial Germany (Chapter 3). First, taking the very long-term view, she shows that inequality passed through two extended waves: a decline following the Black Death of the mid-1300s; an upswing starting around 1450 until the start of the Thirty Years’ War in 1618; another decline until 1700; followed by another increase. Gierok’s new characterization starkly differentiates Germany’s experience from that of other European regions throughout the early modern period, where wealth inequality increased more steadily. The clear culprit is the dramatic, deleterious impact of the Thirty Years’ War and its corollaries of plagues and famines.

Next, Gierok develops poverty estimates and demonstrates how poverty generally followed a similar path as inequality, with the notable exception of the peak during the Thirty Years’ War, when both poverty and inequality rose (Chapter 4). She also highlights the disproportionately negative impact of the war on rural communities, where combatants destroyed cultivated land and livestock.

In a deeper dive into the detailed records of one city, Freiburg, Gierok takes on the issue of gender discrimination in the guild system and its effects on economic growth from the late fifteenth to the late seventeenth century (Chapter 5). Again, the tax registers reveal clues, in this case pointing to low rates of female headship in this guild-dominated city. With the onset of the Thirty Years’ War, however, women began to gain traction in the guilds and especially in the textile trade. Overall, women fell disproportionately into poverty and found meager economic opportunity. This strikingly rich study could form the basis of a broader analysis of the impact of economic institutions, such as guilds, on gender disparities over an extended trajectory.

Gierok’s penultimate chapter (Chapter 6) provides a range of new estimates of fiscal extraction for a representative sample of 49 German cities from 1300 to 1800 and highlights the role of taxation in driving inequality and poverty. Her novel measures of per capita “fiscal pressure” shows that these forces remained relatively low throughout the late Middle Ages but increased over the decades leading up to the Thirty Years’ War—causing Germany to overtake even more advanced areas of England, the Netherlands, and France. The benefit of the new fiscal data is that it will aid in explaining the coincident increase in wealth inequality and the connection to the widespread and enduring impacts of pandemic disease and war.

This dissertation far exceeds the more common standard of three papers “stapled” together and surely sets the stage for a full-length monograph. Moreover, the databases she presents should provide material for Gierok and many other researchers to exploit and expand on for years to come.

Mark Hup: Essays on Fiscal Modernization, Labor Coercion, State Capacity and Trade

Dr. Hup completed his PhD in economics at the University of California at Irvine under the supervision of Dan Bogart. Another dissertation addressing the problem of state capacity, the three papers in his dissertation take on various aspects of the tax system in Colonial Indonesia of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Hup undertakes a political economy analysis of the institutional and trade-related drivers behind the shift from coerced labor to monetary taxation to provide a new understanding of the centralization and monetization of fiscal extraction in Indonesia. He first creates a novel, longitudinal database of provincial-level coerced labor, taxation, and trade and then provides careful quantification of institutional factors with attention to identification issues.

Beginning with a study of fiscal modernization from 1874 to 1905, Hup finds countervailing forces that pushed the Indonesian state toward centralization of financing through monetary poll taxes, but also delayed such a transition away from forced labor (corvee) due to indigenous officials working to expand state capacity on the local level. In the subsequent decades, as Hup shows in his second chapter, labor-intensive trade expansion propelled further reductions in forced labor. As workers could buy out of corvee stipulations, they effectively converted labor into monetary tax revenues. Hup also shows that the drop in trade during the Great Depression reversed the trend, creating a relatively flexible system that allowed workers to opt in and out of monetary versus labor-based taxation, thereby alleviating information-collection requirements on the state.

Hup’s third essay takes up the issue of tax farming—the privatized collection of taxes on behalf of the state—that was widely used in earlier periods and is still used today in some places. Using a novel province-level dataset of tax revenues and state officials in colonial Java from 1874–1905, he shows how Indonesian state capacity expansion led to less reliance on tax farming around the turn of the twentieth century. Further, consistent with his hypothesis, he finds that the majority of indigenous populations, who were traditionally excluded from tax farming, pushed to convert tax collection to state collection bureaucracy.

Overall, Hup’s three essays, complete with well-documented institutional details, provide a new understanding of the emergence of the modern fiscal state in Indonesia, an area whose economic history has received relatively little attention. This case also highlights the complexity and importance of optimal taxation schemes and how they evolve with state capacity, as well as the interplay and consequent political power dynamics between colonial administrators and the populations they ruled.

COMMON ELEMENTS OF EXCELLENCE

To summarize briefly the accomplishments of the three finalists for the 2022 Gerschenkron Prize, I underscore the common elements of excellence across the three works. All of the finalists asked big and deep questions, demonstrating intellectual curiosity and an unusual level of independent and richly-detailed work. Only one chapter of one of the three dissertations had co-authorship, and that stemmed from an enormous, externally-funded, collaborative data collection effort. The three dissertations all opened up a “black box” of aggregate, long-run patterns with the painstaking collection of truly novel micro- or municipal-level data and the use of rigorous analysis, both statistical and institutional. By coincidence, all three dissertations related to taxation, either as the topic itself or as the evidentiary basis that elucidated the topic of concern, such as wealth inequality. This fact points to the treasure trove of original source material that likely awaits diligent and energetic economic historians willing to undertake the painstaking work of unearthing, cleaning, and analyzing such records in myriad countries over a span of many centuries.

It was a real challenge to decide on and then among the finalists for the 2022 Gerschenkron Prize. I extend my congratulations to all 24 candidates who submitted their work, the three finalists, and especially to Dr. Hanzhi Deng as the ultimate recipient of the prize.

Caroline Fohlin, Emory University

A History of Decentralization: Fiscal Transitions in Late Imperial China, 1850–1911

A key question regarding the state building of late Qing China (1850–1911) is why a precarious central court led not to a collapse but to the remarkable transformation of its fiscal-military regime. It offers us an opportunity to speak to the spectacular state capacity literature, where the making of a fiscal state is a time-honored theme.

Pioneering historians outline a Whig-style roadmap for state evolution, including the phases of a tribute, domain, tax, and fiscal state,Footnote 1 while explaining such transitions is quite challenging. The financial history scholarship identifies several clusters of driving forces, such as the early takeoff of financial sectors (Dickson Reference Dickson1967; Brewer Reference Brewer1990), ex ante commercial prosperity (Mathias and O’Brien 1976; Mathias Reference Mathias1979; O’Brien Reference O’Brien1988), and professional bureaucracy (O’Brien and Hunt Reference O’Brien, Hunt and Bonney1999). Meanwhile, historical sociologists stress the role of a common geopolitical factor in Europe—international wars—in the making of fiscal-military states.Footnote 2 Furthermore, new institutional economics establishes a more coherent framework: the combination of historical and rational-choice institutionalism not only incorporates structural factors and shocks but also accepts multiple potential outcomes of institutional evolution; this enables the actors in the repertoire to rationalize their behaviors in a dynamic way.Footnote 3

The aforementioned literature broadly defines a “fiscal state”: first, a unified legal and bureaucratic system with state sovereignty; second, monetized taxation with a broad tax base; and third, adoption of public credit tools with long-term commitment from the state. However, this definition suffers from external validity problems when applied from European nation states to other regimes such as city states and empires.Footnote 4 Heterogeneities of regimes force us to rethink the current framework, and it can be particularly helpful to reexamine the following four issues.

The first is the role of wars: international wars were indisputably important in modern Western Europe, but this pattern may not apply in other geopolitical environments.Footnote 5 Furthermore, the role of internal insurrections is usually understated, while existing studies suggest contradictory results.Footnote 6 The second issue is the pattern of political participation: representative institutions occupy a central place in European narratives, whose importance may be overstated in other contexts.Footnote 7 The third issue is tax base: indirect taxation enjoyed remarkable growth in the modern Western world; for contemporary times, contrastingly, direct taxation has become increasingly important as a channel of redistribution and welfare provision.Footnote 8 However, this temporal pattern may not be accepted as a global law. The final issue is the principal-agent problem, the severity of which is mainly determined by country size and distance from the periphery to the power center. The literature on nation states underlines the efficiency and economy of scale brought by centralization.Footnote 9 However, what a giant bureaucratic or colonial empire needed was not absolute centralization, but a sophisticated trade-off between centralization and decentralization.Footnote 10

This thesis revises the current fiscal-military state theories by reexamining fiscal changes of late Qing China, a key observation in the Great Divergence debate. It employs the new institutionalist framework and investigates how both pre-1850 socioeconomic conditions, such as demographic patterns and fiscal infrastructure, and post-1850 shocks, such as the Taiping Rebellion (1851–64), ultimately reshuffled the imperial fiscal regime; it also examines how central and local agents reconsidered their endowments and constraints and thereby rationalized their behaviors.Footnote 11 This thesis avoids treating Qing China as a single research unit;Footnote 12 instead, it deconstructs the political hierarchy into multiple layers and emphasizes the spatial and temporal variations of fiscal practices at the provincial and prefectural levels.

By emphasizing the role of local governments, this thesis concludes that local fiscal-military autonomy granted by the precarious Qing central court in the early 1850s served as the ultimate impetus for bottom-up fiscal restructuring and expansion. Rational local agents with strong incentives and information advantages transformed the over-centralized, rigid, and land-tax-based fiscal regime into a decentralized and dynamic one within several decades. This local-centered fiscal regime became increasingly responsive to socioeconomic challenges and accountable for public goods provision and economic growth.

This thesis aims to make several contributions. First, it transcends the current nation-state benchmarks by analyzing a bureaucratic empire whose regime accountability, elite structure, and geopolitical condition differed greatly. Secondly, it provides more conceptual nuance about state capacity by identifying and distinguishing “central/local capacity” and “taxation/spending capacity.” Thirdly, it reinterprets the paths and mechanisms of China’s modernizationFootnote 13 and develops a coherent narrative for various bottom-up fiscal phenomena. Finally, it offers general implications on how fiscal capacity triggered and facilitated industrial modernization, a key theme in the Great Divergence literature.

FORCED DECENTRALIZATION: TAIPING REBELLION AND LOCAL INDIRECT TAXATION

The early-nineteenth-century Qing public finance had suffered a chronic malaise, and the abrupt Taiping Rebellion (1851–64) triggered the unprecedented transitions. The rebellious regime failed to attract gentry elites and mass people, whereas the Qing state took this opportunity to strengthen its legitimacy and capacity. The precarious central court abandoned the ancien régime and granted local governments the greatest fiscal-military autonomy in exchange for dynastic longevity. Hence local governments not only established new armies and militias but also introduced a novel tax, the lijin, to finance their military actions. Lijin was an indirect tax on transported goods, usually levied at the transportation hubs on key roads and waterways.Footnote 14 The Qing regime survived the Taiping crisis with timely lijin income, and local governments firmly preserved their lijin funds in the postwar decades.

This chapter quantifies the prefectural intensity of Taiping warfare with archival materials;Footnote 15 it uses available surveys to map the rise, spread, and postwar persistence of the lijin institutions at the local level, too.Footnote 16 It presents an internal “war making state” story by constructing the link between the Taiping Rebellion and the rise of indirect taxation, through which the de facto local fiscal system gradually took shape.

INDIRECT TAXATION: DOMESTIC CUSTOMS, MARITIME CUSTOMS, AND LIJIN INSTITUTIONS

This chapter continues discussing indirect taxation and expands the scope to all types of late imperial indirect taxation, namely lijin, domestic customs (changguan) and maritime customs (yangguan).Footnote 17