THE CONSTRUCTION OF MASCULINITIES IN MESOAMERICA

The sculptures and iconographic representations of groups of masculine individuals, often depicted carrying out ritual activities or participating in warrior processions, have for many years stimulated a debate on the structure of power at Chichen Itza. These representations do not seem to emphasize the figure of a solitary ruler, as is typical of the Late Classic period; instead, the collective representations dominating building decorations at Chichen Itza's epicenter during the Terminal Classic period manifest a political, military, and ritual discourse that praises a mostly male collectivity. We argue that the construction of an “official” discourse on masculinities played a fundamental role in both practice and on a symbolic level among the strategies designed to support the structure of power in this emblematic pre-Columbian capital.

The numerous images of warriors on the walls of Chichen Itza's buildings attest to the military character of the city. Those representations exhibit male individuals conducting activities that naturalize their gender and their exercise of power (Joyce Reference Joyce2000a; Ringle Reference Ringle2009; Wren et al. Reference Wren, Spencer, Nygard, Wren, Kristan-Graham, Nygard and Spencer2018). The archaeological evidence presented below allows us to approach the agency, rituality, and practices of certain groups of men who were political and military pillars of their community. We will focus on particular spaces where men are represented, where they meet and carry out rituals. Our discussion will be fueled by new data recovered from Structure 2D6, a gallery-patio located in the northeastern corner of the Great Platform. Following Ringle and Bey (Reference Ringle, Bey, Fash and Luján2009), we argue that these buildings served as a venue for the preparation, instruction, and socialization of groups of warriors.

Scholarly interest in the construction of masculinities is, ultimately, a result of the feminist movement and the inclusion of gender as a category for sociocultural analyses. The changes in anthropological thought since the 1960s called into question the patriarchal system and its values, in both ancient and contemporary societies (Gutmann Reference Gutmann1997). Today, we understand that in many cultures male interest in perpetuating the so-called “universal truths” is aimed at the affirmation of male superiority and power (Carabí Reference Carabí, Segarra and Carabí2000:16). In most cultures, the ideology of masculinity includes bodily representations and symbols, a gender-specific use of space, diverse learned behaviors, and sexuality (Alberti Reference Alberti2001, Reference Alberti and Nelson2006; Gutmann Reference Gutmann and Barfield2000; Knapp Reference Knapp and Whitley1998). These aspects are culturally mythicized to create a naturalized relation between males and power. Therefore, masculinity becomes manifest through those aspects of maleness that are socially recognized as particularly powerful (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist1999:64; Gilmore Reference Gilmore1994). The quality of being a man is manifested through several material media susceptible to archaeological research, including weapons and other related military paraphernalia (Gilchrist Reference Gilchrist1999; Joyce Reference Joyce and Claassen1992; Nottveit Reference Nottveit2006). However, it is through bodily representations such as mural paintings, figurines, and sculptures, that masculinity discourses become more evident (Alberti Reference Alberti2001; Ardren Reference Ardren, Gómora and Hendon2011, Reference Ardren2015; Ardren and Hixson Reference Ardren and Hixson2006; Joyce Reference Joyce and Wright1996, Reference Joyce2000a, Reference Joyce and Klein2001; Knapp and Meskell Reference Knapp and Meskell1997).

On a conceptual level, the idea of a common ideological model that considers men and women to be complementary entities prevails among scholars conducting gender studies in Mesoamerica (Ardren Reference Ardren2002, Reference Ardren2015; Brumfiel Reference Brumfiel and Bolger2013; Joyce Reference Joyce and Claassen1992, Reference Joyce2000a, Reference Joyce and Klein2001; Miller and Taube Reference Miller and Taube1993; Rodríguez Shadow Reference Rodríguez Shadow and Shadow2007; Tate Reference Tate2004). Despite calls for caution, men and women—as well as other social realities—continue to be distinguished through productive activities, learned behaviors, distinctive use of spaces, or material elements like clothes and corporal ornaments. However, many assumptions about the qualities defining male identity in the past remain unproven. Commonly, men are depicted as dominant, aggressive, and violent beings. In addition, they were principally responsible for the exercise of political and ritual power among higher civilizations, such as the Maya, Toltecs, and Aztecs (Ardren Reference Ardren, Terendy, Lyons and Jansen-Smekal2008, Reference Ardren, Gómora and Hendon2011; Ardren and Hixson Reference Ardren and Hixson2006; Hernández Álvarez Reference Hernández Álvarez, Gómora and Hendon2011, Reference Hernández Álvarez and Shadow2013, Reference Hernández Álvarez and Cobos2016; Joyce Reference Joyce, Schmidt and Voss2000b).

Following Joyce (Reference Joyce and Wright1996), Mesoamerican gender ideology is conceived of as highly fluid, lacking the essentiality and immutable qualities present in the Western world. In the case of Mesoamerica, the conceptualization of gender is produced through an original androgyny, through creative action in mythical time, which is recreated in individual time through social media. However, throughout pre-Columbian times, this ideology was also used to construct an idea of maleness strongly associated with the exercise of power, the use of force, and the control of sexuality (Joyce Reference Joyce and Klein2001, Reference Joyce, Gustafson and Trevelyan2002). The study of archaeological materials and monumental art has led Maya scholars to recognize activities such as the participation in elaborate rituals like the ball game, dances, and both self-sacrifice and the sacrifice of prisoners as fundamental for the construction of a hegemonic idea of masculinity. This ideology describes a structure of power where patriarchy is legitimated and secures its perpetuation (Wren et al. Reference Wren, Spencer, Nygard, Wren, Kristan-Graham, Nygard and Spencer2018:259).

This was particularly true for individuals who belonged to the higher spheres of Classic Maya society and exercised political and religious power. In this sense, the analysis of the relationship between power and the representations of being a man has been used to understand the way male identity was constructed among the ancient Maya (Ardren Reference Ardren, Terendy, Lyons and Jansen-Smekal2008, Reference Ardren, Gómora and Hendon2011, Reference Ardren2015; Ardren and Hixson Reference Ardren and Hixson2006; Joyce Reference Joyce and Wright1996, Reference Joyce, Schmidt and Voss2000b). For example, Houston (Reference Houston2018) studied how elite men were “grown” and nurtured as youths among the Classic Maya because they formed a chief mechanism of governance and were the core of this culture. “Without them, there would be no future for a dynasty or a kingdom. Training and shaping young men assured elites that matters important to royal families would be reproduced, that a kingdom would not dissolve” (Houston Reference Houston2018:6–7).

Joyce (Reference Joyce, Gustafson and Trevelyan2002:336) stresses that bodily representations during the Classic period exhibit a tendency to highlight certain qualities among male individuals. They are depicted as highly active—dancing, capturing enemies, or playing the ball game. The same author argues that these representations of the male body carry marked erotic connotations, alluding to the fact that among the Maya the male body is the primary reference in matters of sexuality. The practice of self-sacrifice by means of perforating the penis is a signal aspect of the relationship between men, power, sexuality, and fertility, which reinforces the sense of male dominance symbolically. The practice of self-sacrifice acquired such importance in the conceptualization of masculinity that it was widely documented throughout the Maya area during pre-Hispanic times. Interestingly, the number of representations is considerably higher among the Maya than any other Mesoamerican culture (Joyce Reference Joyce and Klein2001). Another instance of male sexual symbolism in the Northern Maya Lowlands in particular is the presence of phallic sculptures carved in bulk. Such assemblages have been recognized as an indicator of spaces where rituals were carried out. Alternatively, sculptures are interpreted as elements that legitimize the authority of certain individuals or groups (Amrhein Reference Amrhein2003; Ardren Reference Ardren, Gómora and Hendon2011, Reference Ardren2015; Ardren and Hixson Reference Ardren and Hixson2006).

Nevertheless, it would be naive to think that a monolithic conception of a hegemonic masculinity was the norm through time. As different scholars have shown, Maya societies may have organized gender identities in terms of complementarity or fluidity, but dominant and hegemonic masculinities should be questioned in order to understand how elite male groups exercised power over women and subordinate males. In this regard, the iconographic program of the Great Terrace suggests that a shift toward dominant and hegemonic masculinities occurred at Chichen Itza in Terminal Classic times (Wren et al. Reference Wren, Spencer, Nygard, Wren, Kristan-Graham, Nygard and Spencer2018). Also, based on the examination of material evidence and under the light of new theoretical models, we believe that other forms of male identity did exist among the pre-Columbian Maya. Thus, a discussion regarding their implications on a social level needs to be started (Hernández Álvarez Reference Hernández Álvarez, Gómora and Hendon2011). We follow a multivariate archaeological approach, which allows us to tackle issues such as agency, rituality, and social practices of male individuals at a site as complex as Chichen Itza.

AGENCY, RITUALITY, AND THE SPACES OF MASCULINITY AT CHICHEN ITZA

At Chichen Itza, the representation of numerous male figures on murals and architectural features, such as benches, stages vaults, lintels, jambs, columns, pilasters, and panels, is ubiquitous. Several authors highlight the presence of individuals representing different groups or occupations, which include priests, warriors, captives, and ball players (Castillo Borges Reference Castillo Borges1998; Cobos and Fernández Souza Reference Cobos and Souza2015; Evans Reference Evans2015; Kristan-Graham Reference Kristan-Graham1993; Mastache et al. Reference Mastache, Healan, Cobean, Fash and Luján2009; Miller Reference Miller1978; Ringle Reference Ringle2009; Ringle and Bey Reference Ringle, Bey, Fash and Luján2009; Robertson and Andrews Reference Robertson and Andrews1992; Schmidt Reference Schmidt, Kowalski and Kristan-Graham2007, Reference Schmidt, Arroyo, Paiz, Linares and Arroyave2011). The most recurring actions performed are war, sacrifice—either through decapitation or by extracting the heart—the ball game, and marches or processions. The latter might include bound captives, self-sacrifice, and the exhibition of genitals. This collective identification, however, is nuanced by the visual differentiation of individuals based on their attire, portable objects, and sometimes bodily characteristics (Robertson and Andrews Reference Robertson and Andrews1992).

The possibility to identify individuals in real or historical occasions is reinforced by the scenes in which they are depicted. After analyzing the murals at the Upper Temple of the Jaguars and the Temple of the Warriors, authors like Miller (Reference Miller1978), Ringle (Reference Ringle2009), and Cobos (Reference Cobos, Cobos and Souza2011) emphasize the fact that some battle scenes depict hills or shorelines, while in other settlements under attack, houses display recognizable thatching styles or walls with characteristic features which particularize the events. Male individuals were also carved into benches, columns, and pilasters of buildings like El Mercado, apparently converging on particular accesses or stages. Hence, the scenes seem to reproduce processions or rituals in the same spaces in which they were performed (Ringle Reference Ringle2009; Ruppert Reference Ruppert1943; Wren et al. Reference Wren, Spencer, Hochstetler, Koontz, Reese-Taylor and Headrick2001). An identical pattern can be observed in the Palacio Quemado at Tula (Cobos and Fernández Souza Reference Cobos and Souza2015; Ringle Reference Ringle2009; Ringle and Bey Reference Ringle, Bey, Fash and Luján2009; Robertson and Andrews Reference Robertson and Andrews1992). Ringle and Bey (Reference Ringle, Bey, Fash and Luján2009) argue that carved benches and stages including lined-up individuals might have had semi-public or public functions. In these cases, the interior of buildings formed a scenery that framed and reinforced the ritualistic actions performed by actual men in the company of other male individuals who were carved or painted onto the surrounding walls. Far from being an anonymous crowd, several depicted individuals provide clues as to their identification (Boot Reference Boot, Colas, Delvendalh, Kuhnert and Schubart2000; Ringle Reference Ringle2009; Trejo Reference Trejo2000).

As mentioned above, groups of people sharing an occupation, such as warriors, priests, or merchants, have been inferred based on clothing, badges, or ornaments. These garments might have been the result of different military orders or ranks inside the groups (Miller Reference Miller1978; Ringle Reference Ringle2009; Ringle and Bey Reference Ringle, Bey, Fash and Luján2009; Robertson and Andrews Reference Robertson and Andrews1992). Moreover, there were prominent individuals among these people, such as Captain Sun Disc and Captain Serpent, identified in the Upper Temple of the Jaguars (Miller Reference Miller1978), who had initially been interpreted as deities or celestial beings. Ringle (Reference Ringle2009), however, argues that both were real people, who, in all likelihood, occupied specific, high-status positions in Chichen Itza's political and military hierarchy. The same author suggests that one leader, who wore the badge of the Cloud Serpent or Mixcóatl, used the Osario Group as an exclusive ceremonial compound for himself (or his rank) and his cohort.

Based upon the aforesaid iconographic evidence, we identify three types of images representing male individuals at Chichen Itza: (1) groups of men showing features relating them to the membership of an occupational group, such as warriors, priests, or ballplayers; (2) subgroups or individuals exhibiting ranks, which are identifiable through attire, insignia, or colors; and (3) specific figures representing human or mythical beings, such as Captain Feathered Serpent or Captain Cloud Serpent, or individuals who have been identified by name, such as the ruler K'ak' u Pakal. Being repeatedly represented performing in real scenarios, with very different possibilities for public access, these three types or levels reinforced, guided, and maintained the perspectives that the community at Chichen Itza held with respect to men and the roles, values, and obligations associated with masculinity.

It is worth noting that the representations of groups of male individuals at Chichen Itza are framed in a Mesoamerican context. Trejo (Reference Trejo2000), for example, proposed a series of similarities in “the image of the victorious warrior in Mesoamerica” at Chichen Itza, Tula, Tlaxcala, and Malinalco. Societies of men and military orders of eagle and jaguar warriors existed in those cities and performed strict and strong practices of training and self-sacrifice (Trejo Reference Trejo2000:235–236). Joyce (Reference Joyce2000c) and Ardren (Reference Ardren2015) discuss some ways in which Mesoamerican children, young men, and women were socialized following gender-specific parameters, with war being a matter for men (Joyce Reference Joyce2000c; Kellog Reference Kellogg1995).

The “production of adulthood” was carried out in part at home and, according to ethnohistorical sources, in part in communal institutions (Joyce Reference Joyce2000c:477). Sahagún (Reference Sahagún1985), for example, states that calmecac and telpochcalli were Aztec institutions where young men would live and work, performing the humblest tasks while slowly ascending in both dignity and rank. According to Sahagún, parents who handed their boys to one of numerous telpochcalli expected them to be raised with other young men to serve the people and be prepared for war (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1985:208–210).

In Yucatan, something similar is described by Bishop Diego de Landa (Tozzer Reference Tozzer1941:124), who claims the following about young men:

(…) they were accustomed to have in each town a large house, whitened with lime, open on all sides, where the young men came together for their amusements. They played ball and a kind of game of beans, like dice, as well as many others. Almost always they all slept together here also until they married (Tozzer Reference Tozzer1941:124).

The model of a warrior's manliness permeated and was assumed during the socialization of infants, prior to the formal education at young men's houses, as seen in Landa's reference to little boys’ games: “during the whole of their childhood they were good and frolicsome so that they never stopped going about with bows and arrows and playing with one another” (Tozzer Reference Tozzer1941:125). Landa's description of the education and organization of warriors exhibits both a communal sense and the possibility of individuals to ascend the ranks according to their abilities. This chronicler mentioned that “the captains were always two in number, one, whose office was perpetual and hereditary and the other elected with many ceremonies for three years.” This suggests that some men were born with the right of command in the military corps, while others needed to be elected. On the other hand, the actions of the soldiers were publicly recognized and celebrated: “If one of them [the soldiers] had killed a captain or a noble he was highly honored and feasted” (Tozzer Reference Tozzer1941:122, 123). Hence, we notice the existence of a fixed structure in which the group played the fundamental role. Nonetheless, the acknowledgement of certain young men's ability to stand out and rise through their own actions, independent of their origin, also offers us a view on a differentiated agent, who may have been manifested in pre-Contact art in depictions of recognizable individuals.

Following Landa, Ardren (Reference Ardren2015:128) analyzes archaeological structures from pre-Columbian sites in northern Yucatan and contends that men's houses were not only gender-restricted spaces, but places for the performance of activities that reinforced gendered ideals. Maya men's houses were places of intense socialization. Spaces designed to hold activities such as military and athletic training, gaming, subjugation of captives, and ritualized violence. “Men spent time in these places in the presence of other men as part of transitional rituals that solidified their identities as adult men and in activities that maintained a masculine identity” (Ardren Reference Ardren2015:142).

Baudez and Latsanopoulos (Reference Baudez and Latsanopoulos2010:17) contend that the demand of warriors at Chichen Itza should have caused the existence of several training facilities to be a necessity. This argument is inspired by Sahagún (Reference Sahagún1985:210), who claimed that Tenochtitlan held 10–15 telpochcallis in each barrio. Baudez and Latsanopoulos (Reference Baudez and Latsanopoulos2010) also propose that the carvings at the Temple of the Wall Panels show different moments in the training of warriors, and that the feline figures represent the transformation of young students into jaguar warriors. Nevertheless, these authors also stress that this temple does not seem to have the characteristics for being the place of training itself. Targeting the question of where to look for the spaces of formalized education for young men, we suggest exploring gallery-patio structures. The attempt to assign a single function for all buildings of this type remains problematic. Data recovered from the gallery-patio Structure 2D6 provide intriguing new perspectives regarding the training of warrior youths.

STRUCTURE 2D6: A COLONNADED HALL AT CHICHEN ITZA

For some time now, Mesoamerican colonnaded halls have been a source of interest and debate among scholars as to their function and role within sites. A particular type of colonnaded structure, the so-called gallery-patio, has been recurrently reported at Chichen Itza (Cobos Reference Cobos, Sanders, Mastache and Cobean2003, Reference Cobos, Demarest, Rice and Rice2004; Fernández Reference Fernández Souza, Rubio and Gubler2006; Lincoln Reference Lincoln1990; Ruppert Reference Ruppert1943, Reference Ruppert, Reed and King1950). Structure 3D11, also named El Mercado, is the best known of the gallery-patios at the site and was described and interpreted by Ruppert (Reference Ruppert1943).

Gallery-patios are structures characterized by a large frontal colonnaded space, an open sunken area surrounded by similarly colonnaded walkways, and, occasionally, an attached squarish extension proposed to have been a shrine (Fernández Souza Reference Fernández Souza, Rubio and Gubler2006; Ruppert Reference Ruppert1943, Reference Ruppert, Reed and King1950). Gallery-patio structures tend to be associated with other buildings at Chichen Itza (Figure 1), forming architectural patterns reported by Lincoln (Reference Lincoln1990; temple, palace, gallery-patio) and Cobos (Reference Cobos, Sanders, Mastache and Cobean2003; temple, altar, gallery-patio). Although relatively rare in the Maya area, structures with similar characteristics have been reported from the Preclassic until the Postclassic in Mesoamerica, at sites such as Montenegro, Monte Albán, Nohmul, La Quemada, Tula and Mitla (Acosta Reference Acosta1992; Chase and Chase Reference Chase and Chase1982; Diehl Reference Diehl and Rice1993; Fahmel Beyer Reference Fahmel Beyer1991; Healan Reference Healan and Healan1989; Hers Reference Hers, de Jordán and de Arechavaleta1995; Marcus Reference Marcus1978).

Figure 1. Map of the Chichen Itza site center (from Cobos et al. Reference Cobos, Roche, Carrillo and Cobos2016).

Several scholars have advanced proposals regarding the functions of gallery-patio structures, including locales for civic activities (Hers Reference Hers, de Jordán and de Arechavaleta1995), civic-ceremonial activities (Diehl Reference Diehl and Rice1993:265; López Luján Reference López Luján2006), or residences (Freidel Reference Freidel and Ashmore1981). Ruppert (Reference Ruppert1943) proposed a set of possibilities for the Mercado at Chichen Itza: courts of justice, rooms for dignitaries, pilgrims, sacrificial victims, prisoners, or ball players. In contrast, Lincoln (Reference Lincoln1990) assigned the productive aspect of society to gallery-patio structures with temples representing the religious and palaces the military sectors. The excavation of Structure 2A17, a patio (without a gallery) by Cobos (Reference Cobos, Sanders, Mastache and Cobean2003) and Fernández Souza (Reference Fernández Souza, Rubio and Gubler2006), located at the end of Sacbé 61, 1.2 km to the west of the city center, suggests a residential function. More recently, Osorio León and Pérez Ruiz excavated the Galería-Patio de la Luna, located in the Initial Series Group, next to the Palace of the Phalli and the House of the Snails. Its ample gallery is supported by a total of 36 columns and the authors propose it may have been used for ceremonies or communal reunions (INAH 2019).

Structure 2D6 is the only gallery-patio facing the Great Platform as part of its Northeast Group (Figure 2). It is located immediately to the north of Structure 2D7, or the Temple of the Big Tables. The building is composed of three sectors: a frontal colonnaded hall, a patio originally accessed through a doorway in the center of the rear wall, and a room with a masonry roof attached to the northern flank of the gallery (Figure 3). Only the colonnaded hall was excavated during the 2009–10 Chichen Itza Project directed by Cobos (Reference Cobos2016; Fernández Souza et al. Reference Fernández Souza, Zimmermann, de la Torre, Llanes and Cobos2016). It forms a rectangular space, 28.7 m long and 11.5 m wide, totaling an interior area close to 330 m2. The building has four rows of eight columns each, making a total of 32. The west-facing front opened into the northeastern sector of the Great Platform (Fernández Souza et al. Reference Fernández Souza, Zimmermann, de la Torre, Llanes and Cobos2016). Excavations revealed that the building had no vault, but a flat roof, possibly assembled by a combination of beams and wooden logs, which supported the small rocks, limestone rubble, and plaster covers detected in trenches. Above the columns, the façade was a plain wall, framed by upper and lower moldings. The roof was decorated with merlons in a way that resembles the Temple of the Big Tables and El Castillo. Abutting the walls which enclose the interior of the gallery runs an almost continuous bench, interrupted only by the access to the patio. This passage was closed during a late moment of occupation (Figure 4).

Figure 2. South–north view of Structure 2D6 frontal gallery. Photograph by Fernández Souza.

Figure 3. Overlay of elevation map, floor plan, and hypothetical reconstruction of the gallery of Structure 2D6. Arrows indicate key features discussed in the article. Nomenclature for column rows employs numbers (south–north) and letters (west–east). Mapping and drawing by R. Canto Carrillo and Fernández Souza; digitalization by J. Venegas de la Torre and R. Canto Carrillo.

Figure 4. Closed access in the eastern wall of the gallery. Photograph by Fernández Souza.

Benches, altars, or thrones are frequently associated with buildings at Chichen Itza, such as the Temple of the Warriors and the Court of the Thousand Columns. The bench at El Mercado shows a procession of tied warriors approaching an individual who may be a sacrificial officer (Ruppert Reference Ruppert1943). Another example is a stone table reported by Osorio León and Pérez Ruiz (INAH 2019) in the Initial Series Group. According to the authors, this reused sculpted monolith in the House of the Snails represents 18 captives with their hands tied and another 16 warriors, possibly their captors. Other Mesoamerican sites show similar features. For example, at Tula, Diehl (Reference Diehl and Rice1993) suggested that the individuals depicted on the Palacio Quemado bench were warriors, while Kristan-Graham (Reference Kristan-Graham1993) argues that those found within Pyramid B's Vestibule are merchants. At Tenochtitlan, López Luján (Reference López Luján2006) suggests that the procession of individuals shown in the benches of the House of the Eagle Warriors converges in a zacatapayolli, giving a hint to practices of self-sacrifice. The zacatapayolli was a ball of grass destined to receive the thorns of sacrifice. According to Baudez (Reference Baudez2004:258), one of the benches of the Northwest Colonnade at Chichen Itza shows a procession marching towards one of these instruments.

Despite the generally symmetrical floorplan of the 2D6 gallery, a small bench is located to the north of the building's axis, right next to the access to the patio (Figure 5). Interestingly, this altar or throne aligns with another feature found during our excavations: a fallen but apparently in situ trapezoidal stone, similar to a piece found in the Temple of the Warriors (Figures 6a and 6b).

Figure 5. Altar or throne associated with the eastern wall. Photograph by Fernández Souza.

Figure 6. (a) The sacrificial stone during excavation; (b) view of sacrificial stone aligned with throne. Photographs by Fernández Souza.

Some Maya as well as non-Maya iconographic sources contain images of this kind of stone, or they depict stones involved in sacrificial practices. Sacrificial stones have been reported in the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan (some of them were trapezoidal stones or techcatl and some were chacmool sculptures), at Mixquic, and in documents such as the Boturini, Féjérvary-Mayer, Vatican B, and Nutall codices (Beyer Reference Beyer1918; Chávez Balderas Reference Chávez Balderas2007; López Austin and López Luján 2010; López Luján Reference López Luján2006; López Luján and Urcid Reference López Luján and Urcid2009). At Chichen Itza, two archaeological cases have been documented. The first is a sacrificial stone associated with Structure 5C4 or the Temple of the Initial Series Group (Osorio Reference Osorio León2004; Schmidt Reference Schmidt1999, Reference Schmidt, Kowalski and Kristan-Graham2007), and the other is located in front of the bench of the Temple of the Warriors. There are also iconographic representations, such as the depiction of a sacrifice by heart extraction on one of the discs recovered from the Cenote of Sacrifices (Coggins and Shane Reference Coggins and Shane1984; Vail and Hernandez Reference Vail, Hernández, Tiesler and Cucina2007).

Typological analysis of ceramics provides an approximate time frame for Structure 2D6. Jiménez Álvarez (Reference Jiménez Álvarez and Cobos2016:81) states that Peto Cream sherds recovered during excavation exhibit the type's early Terminal Classic forms. Méndez Cab (Reference Méndez Cab and Cobos2016:86) adds a modal analysis of Dzitas type sherds, detecting a dominance of tecomate bowls. This suggests an association with the later facet of the Sotuta complex. Architectural data provide further chronological detail. For example, late in the occupational history of Structure 2D6, dividing walls were raised to create two discrete interior spaces that we will call “enclosures” (Figure 7). The first enclosure is found in the northeastern zone of the gallery. It was made by walling the spaces between columns of the first two rows to form a room of approximately 18 m2. The second enclosure is smaller than the first one, totaling about 10 m2 of interior space. This feature is found immediately to the south of the access to the patio and is limited to two wall panels of similar constructive patterns, arranged at a right angle.

Figure 7. Wall of the southeastern enclosure. Photograph by Fernández Souz.

Pending future vertical excavations, we are unaware of 2D6 substructures and the exact constructive alignment with the Temple of the Big Tables (Castillo Borges Reference Castillo Borges1998). However, a test pit was excavated right in front of Structure 2D6 and only one plaster floor was detected, approximately 0.10 m below the current surface. This suggests that Structure 2D6 was built on the Stage V level of the Great Terrace as part of its last amplification (Cobos et al. Reference Cobos, Roche, Carrillo and Cobos2016), therefore rendering the gallery-patio contemporary to El Castillo, the Venus Platform, and the substructure of the Temple of the Warriors. According to Castillo Borges (Reference Castillo Borges1998:192), Structure 2D7-Sub was constructed on the same final floor level and is contemporary to the Temple of the Chac Mool. Therefore, it is very likely that Structure 2D6 and the Temple of the Big Tables were occupied at the same time.

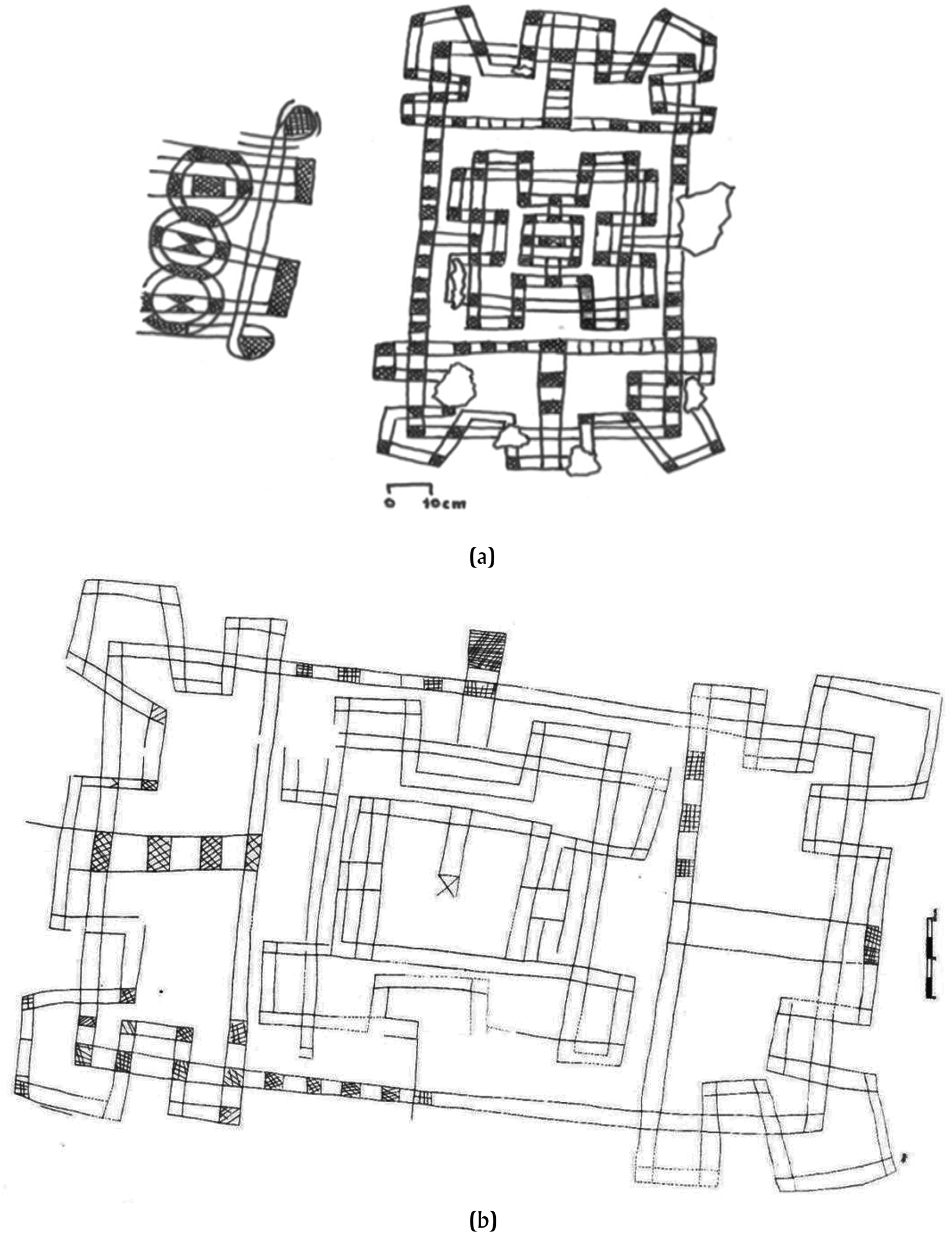

Returning to the gallery's interior, three graffiti were found scratched into the plaster floor of Structure 2D6 (Figures 8a and 8b). These engravings were found in close proximity to each other in the room's southern sector. We propose these graffiti to be game boards called patolli in central Mexico, and bul in the Maya area (Caso Reference Caso1924). Patolli 1 is the most elaborate and exhibits a slightly deeper groove compared to the other two. It measures 1.05 × 0.60 m and is comprised of six overlapping figures: one rectangle, two stylized butterflies in each extreme of the rectangle, two figures similar to a capital “H”, and a central square. The figures are connected by a path of alternating blank and hatched squares. At the very center of the board is an “X,” which possibly marks the goal of the game. Patolli 2 is located 0.25 m to the east of Patolli 1. It is a combination of three circles, straight and curved lines, forming tracks of blank and hatched squares similar to those of Patolli 1. Unfortunately, its western end was damaged. However, in its entirety it may be described as a square board with sides of about 0.50 m in length. In contrast to Patolli 1, its corners are not angular, but curved. Patolli 3, on the other hand, is more akin to Patolli 1: a rectangle with two stylized butterflies on both ends, two “H” shapes, a square, and an “X” at the center. Patolli 3 is also only slightly smaller than Patolli 1, measuring 0.90 m × 0.54 m.

Figure 8. (a) Patollis 1 and 2, Structure 2D6, Chichen Itza; (b) Patolli 3, Structure 2D6, Chichen Itza. Drawings by Fernández Souza and J. Venegas de la Torre.

Patolli have been reported at Maya sites such as Xunantunich (Verbeeck Reference Verbeeck1998; Yaeger Reference Yaeger2005), Calakmul (Gallegos Reference Gallegos Gómora1994), Lagarto Ruins (Wanyerka Reference Wanyerka1999), Dzibilchaltun and the Río Bec region (Andrews V in Swezey and Bittman Reference Swezey and Bittman1983), Uxmal, Piedras Negras (Swezey and Bittman Reference Swezey and Bittman1983), Naranjo (Morales y Fialko Reference Morales, Fialko, Arroyo, Linares and Paíz2010), Nakum (Hermes et al. Reference Hermes, Olko and Zrałka2001), and Structure 5C35 at Chichen Itza (Euan et al. Reference Canul, Gabriel, Ramos, Laporte, Arroyo and Mejía2005). In greater Mesoamerica, finds have been made at Teotihuacan (Verbeeck Reference Verbeeck1998), Tomatlán in Jalisco (Mountjoy and Smith Reference Mountjoy, Smith and Folan1985), and Las Flores in Tamaulipas (Galindo Trejo Reference Galindo Trejo2005). Especially significant, due to the architectural similarities to Structure 2D6, are six patolli from the Palacio Quemado of Tula, a structure with central patios and colonnaded halls (Swezey and Bittman Reference Swezey and Bittman1983), and the carving found in the gallery-patio structure El Mercado at Chichen Itza (Ruppert Reference Ruppert1943).

Although these patolli share features, such as tracks composed of blank and hatched or black squares, they also exhibit significant differences. Some of them, such as an Aztec example illustrated by Durán (Reference Durán1971:354), are designs in the form of an X; others, like the board located on the floor of the temple in Structure VII at Calakmul, are square (Gallegos Reference Gallegos Gómora1994:9). The El Mercado board reported by Ruppert (Reference Ruppert1943) is oval, yet two straight tracks connect the opposing sides of the perimeter, forming a cross. This is similar to a graffito reported by Andrews V at Dzibilchaltun (Swezey and Bittman Reference Swezey and Bittman1983:387, 388). Patolli 1 and 3 from Structure 2D6 are among the most complex boards reported to this day. The patolli from Las Flores, Tamaulipas (Galindo Trejo Reference Galindo Trejo2005), composed of a rectangle, two figures at the extremes, which resemble a stylized butterfly, and a figure at the center, is the only example of similar complexity.

The stylized butterfly motif is very significative because it was frequently worn by Maya, Aztec, and Toltec warriors on their helmets and as pectorals on their chests (Aguilar-Moreno Reference Aguilar-Moreno2006:202; Matos Moctezuma and Solís Olguín Reference Matos Moctezuma and Olguín2002; Ringle Reference Ringle2009:19). Seler (Reference Seler, Thompson and Richardson1996:313) mentions that butterflies were symbols of the ancestors and the deceased. Yet only dead heroes and chieftains, warriors killed in battle or sacrifice, and women who died during childbirth were revered this way. Seler also states that warriors of the Chinampaneca, in cities like Xochimilco, wore butterfly mosaics and ornaments as charms of victory. Focusing on central Mexico during the Postclassic as well as the period of Teotihuacan hegemony, Miller and Taube (Reference Miller and Taube1993:48) argue that butterflies symbolized both fire and the souls of dead warriors. López Hernández (Reference López Hernández2015:86) supplements this notion with the Nahua belief of warriors seeking death in battle in order to be transformed into hummingbirds and butterflies and live for eternity in joy and abundance, inebriated by the nectar of flowers.

As breath had a close relation with the soul in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, Taube (Reference Taube, Stanton and Kathryn Brown2020:166) suggests that stylized butterfly nose pieces found in war serpents at Chichen Itza and Tula may have denoted the souls of the warriors. At Chichen Itza, stylized butterflies also appear as ornaments on the chests of warriors, as seen in the Temple of the Big Tables, the Temple of the Warriors, the Northwest Colonnade, the Upper Temple of the Jaguars and the Palace of the Sculpted Columns (Castillo Borges Reference Castillo Borges1998; Greene Robertson Reference Greene Robertson2004; Greene Robertson and Andrews Reference Greene Robertson and Andrews1992; Headrick Reference Headrick, Stanton and Brown2020; Ringle Reference Ringle2009; Schmidt Reference Schmidt, Arroyo, Paiz, Linares and Arroyave2011). Nevertheless, not all warriors wore the insignia, reinforcing the idea of individuality or belonging to specific military groups. The jambs and pilasters of the Temple of the Big Tables contain depictions of at least 11 warriors wearing stylized butterfly pectorals (Castillo Borges Reference Castillo Borges1998:97, Figure 20). In addition, Str. 2D7 contains small Atlantean figures holding the big stone table or altar located in its rear room. Castillo Borges (Reference Castillo Borges1998:131) stipulated the existence of at least 24 of these figures. Three of the 13 atlantes that were found wear a butterfly insignia. Structure 2D7-Sub also exhibits carved warriors in its pilasters. One of them wears what appears to be a helmet in his headdress; it is painted in Maya blue and carries a stylized butterfly (Castillo Borges Reference Castillo Borges1998:180, Figure 58). This matches the at least 21 Maya blue-colored butterfly pectorals observed in the Temple of the Chac Mool, the Temple of the Warriors, and the Northwest Colonnade, which were allegedly elaborated with turquoise (Taube Reference Taube, King, Carocci, Cartwright, McEwan and Stacy2012:125).

Beside murals, carved pilasters and columns, the stylized butterfly insignia appears sometimes as part of chacmool attires. These stone sculptures have been located at Chichen Itza and other Mesoamerican sites, like Tula, Tenochtitlan, Tlatelolco, Mixquic, and Ihuatzio (Carlson Reference Carlson2013; González de la Mata et al. Reference González de la Mata, Ruíz, León, Schmidt, Arroyo, Salinas and Rojas2014; López Austin and López Luján Reference López Austin and Luján2010; López Luján and Urcid Reference López Luján and Urcid2009; Maldonado Cárdenas and Miller Reference Maldonado Cárdenas, Miller and Góngora2017; Miller Reference Miller1985; Schmidt Reference Schmidt, Kowalski and Kristan-Graham2007). Chacmool sculptures represent male individuals laying on their back, with their legs bent, their hands over their belly, usually holding a receptacle; the head is turned to the side to face the spectator. According to López Austin and López Luján (Reference López Austin and Luján2001:69), chacmoolo'ob had at least three basic ritual functions: as a table for offerings like food, flowers or incense; as a cuauhxicalli or container for the blood and hearts of human sacrifices; and as a techcatl, the stone of sacrifices themselves. At Chichen Itza, Maldonado and Miller (Reference Maldonado Cárdenas, Miller and Góngora2017) have documented 18 of these sculptures. Among those exhibiting butterfly insignias are Chacmool 7, located in El Castillo-sub, Chacmool 12, located at the Temple of Small Tables, and Chacmool 15, found in the interior of the Platform of Venus at the Great Terrace. Chacmool 8 and 13 were found near sacrificial stones (Maldonado and Miller Reference Maldonado Cárdenas, Miller and Góngora2017:93).Withal, the identity of the chacmool remains enigmatic: scholars have proposed that they represented victims for human sacrifices (Miller Reference Miller1985), companion deities of the Maize God (González de la Mata et al. Reference González de la Mata, Ruíz, León, Schmidt, Arroyo, Salinas and Rojas2014:1042), ball players (Carlson Reference Carlson2013), or warriors like those depicted in the murals and carvings at Chichen Itza (Maldonado and Miller Reference Maldonado Cárdenas, Miller and Góngora2017).

Independent of their particular form and constituting elements, most patolli have a relation with the cardinal directions, four corners, or a division of four spaces through cruciform designs. Brinton (Reference Brinton1897:100) stated that games like the patolli, the Indian parcheesi, the game “of promotion” from China, and the “game of goose” from Europe share the concept of four as the corners of the world and the cosmos. He also considered that the game was related to calendrical and divine issues in Central America. The relation of patolli or similar boards with the calendar has been promoted by Digby and Stephenson (Reference Digby and Stephenson1974), Mountjoy and Smith (Reference Mountjoy, Smith and Folan1985), and Voorhies (Reference Voorhies2012). Swezey and Bittman (Reference Swezey and Bittman1983:413) point out that some of the boards require players to pass through 52 squares, possibly linking the game to the number of years in the Mesoamerican calendar round.

An addition to their religious and calendrical purposes, patolli had a mundane and ludic aspect, even including gambling:

… los señores por su pasatiempo jugaban un juego que se llama patolli que es […) como el juego de los dados, y son cuatro frijoles grandes que cada uno tiene un agujero, y arrójanlos con la mano sobre un petate […) donde está hecha una figura; a este juego solían jugar, y ganarse cosas preciosas, como cuentas de oro, piedras preciosas, turquesas muy finas (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1985:460).

Accordingly, Walden and Voorhies (Reference Walden, Voorhies and Voorhies2017:212) argue that patolli might have been played during the Classic period in men's houses. We propose that the interior of Structure 2D6 was, in effect, a stage for this kind of male activity, which exemplified the role of men and the conception and construction of masculinities at Chichen Itza. To support our hypothesis, we complement the study of architectural and archaeological features with chemical residue data from the building's plastered surfaces.

CHEMICAL RESIDUE ANALYSES

At different sites around the globe, chemical residue analyses have been employed as a proxy to artifact and structure function (Barba Reference Barba2007; McGovern et al. Reference McGovern, Zhang, Tang, Zhang, Hall, Moreau, Nuñez, Butrym, Richards, Wang, Cheng, Zhao and Wang2004; Powis et al. Reference Powis, Valdez, Hester, Hurst and Tarka2002). Semi-quantitative analyses have been used specifically to trace concentrations of substances once spilled over exposed surfaces of soil or lime plaster floors (Barba Reference Barba2000; Barba et al. Reference Barba, Ludlow, Manzanilla and Valadez1987). Compared to artifactual data, chemical residues present certain advantages: they were not recycled by occupants; they are invisible and intangible, and therefore safe from looting; and they show a minimum of horizontal and vertical movement (Barba Reference Barba2007:444).

In Mesoamerica, chemical residue analyses have been incorporated into studies of a series of apartment compounds at Teotihuacan (Barba et al. Reference Barba, Ludlow, Manzanilla and Valadez1987; Manzanilla Reference Manzanilla1993, Reference Manzanilla, Manzanilla and Chapdeleine2009; Ortiz and Barba Reference Ortiz, Barba and Manzanilla1993; Pecci Reference Pecci2000), as well as at several Maya sites (Barba and Manzanilla Reference Barba, Manzanilla and Manzanilla1987; Hutson and Terry Reference Hutson and Terry2006; Parnell et al. Reference Parnell, Terry and Golden2001; Pierrebourg Reference Pierrebourg, Laporte, Arroyo and Mejía2007; Terry et al. Reference Terry, Parnell, Inomata, Sheets, Laporte, Escobedo, Arroyo and de Suasnávar2000). The most relevant comparative example for Structure 2D6 is the House of the Eagle Warriors at Tenochtitlan (Barba Reference Barba2000; Barba et al. Reference Barba, Ortiz, Link, Luján, Lazos and Orna1996; López Luján Reference López Luján2006). This Aztec building shares some architectural traits with Structure 2D6, among which figure talud-style benches and semi-open colonnaded spaces, as well as the lime-plaster covering of floors and benches (Barba et al. Reference Barba, Ortiz, Link, Luján, Lazos and Orna1996:141; López Luján Reference López Luján2006:40). Floor samples at Structure 2D6 were taken based on a control grid, with units of 1.2 m in length over a north–south axis, and 1.1 m in width over an east–west axis. In proximity to the “sacrificial stone,” an extra 16 samples were taken, applying a grid with 30 cm units. The bench samples, on the other hand, were taken every 50 cm, alternating along two parallel lines. The altar or throne was covered by five samples corresponding to each of the four corners and its center, as well as one additional sample coming from its front. Unfortunately, in some areas across the floor and benches the plaster was damaged, making it impossible to retrieve the corresponding samples.

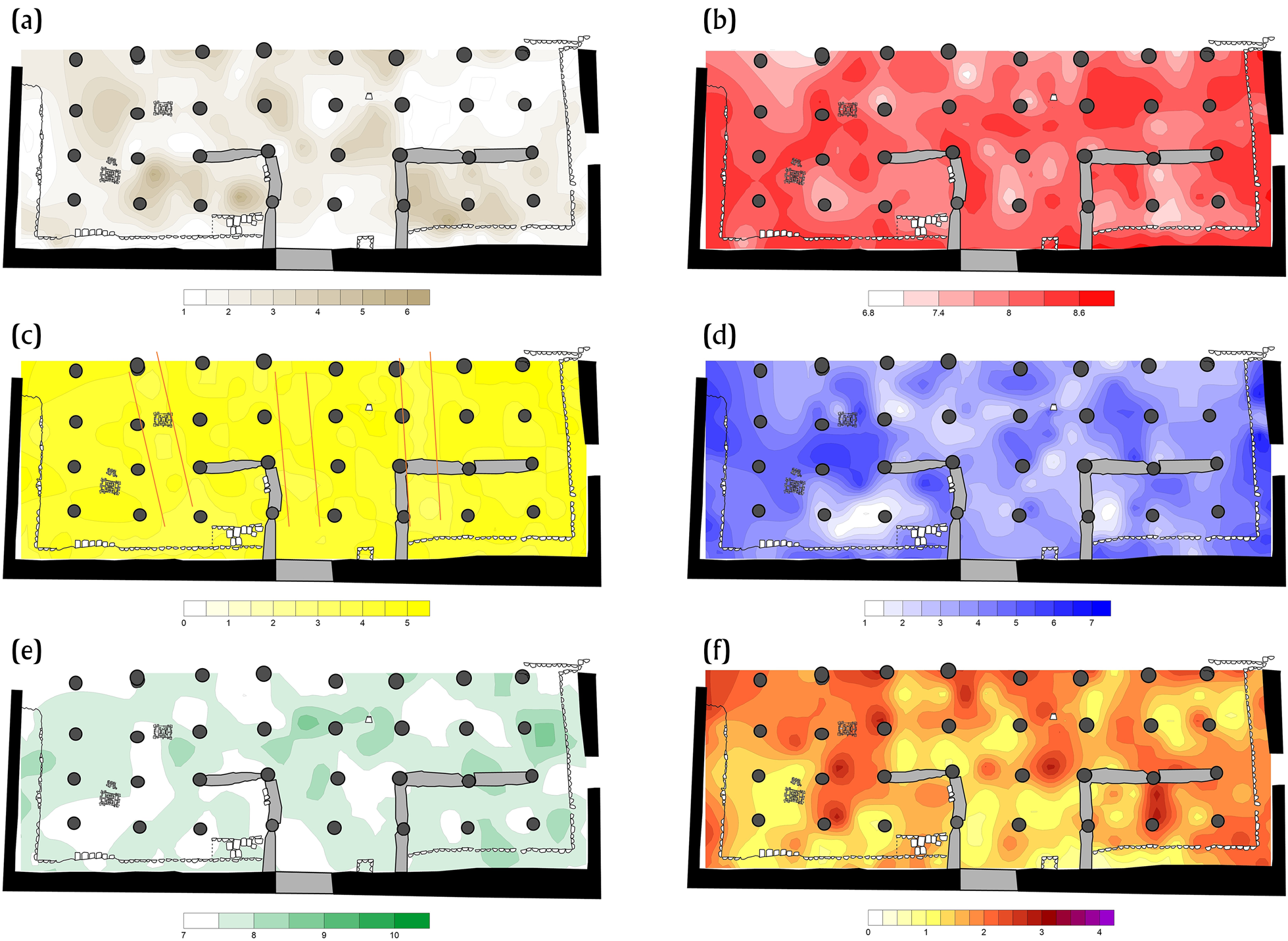

In order to contrast chemical residues with architecture and features, we followed protocols developed by Barba and colleagues (Barba Reference Barba2000; Barba et al. Reference Barba, Ludlow, Manzanilla and Valadez1987). Sediment color was registered using a Munsell© scale, and pH values were determined applying Merck© special indicator strips. Semi-quantitative tests were conducted to trace carbonate, phosphate, protein, fatty acid, and carbohydrate concentrations. Distribution maps were created using Golden Software Surfer 14©. Given the interval-based nature of the resulting datasets, we did not standardize values and project patterns individually (Figure 9). Variations in lime plaster coloration provide first insights into possible variations in sediment composition. Higher pH values are associated with the action of fire, such as in censers or hearths (Barba Reference Barba2007). When studying plastered surfaces, carbonate analyses can be used to trace wear due to frequent foot traffic. Phosphates residues are a general indicator of organic matter (Barba Reference Barba2007), while proteins, fatty acids, and carbohydrates provide a more precise perspective on the latter's origin.

Figure 9. Distribution maps for chemical residues. (a) Sediment color; (b) pH value; (c) carbonates; (d) phosphates; (e) protein residues; and (f) carbohydrates. Courtesy of J. Venegas de la Torre.

The comparison of sediment color shows considerable homogeneity in the lime plaster employed in Structure 2D6, with darker expanses mainly limited to the two enclosures on both sides of the altar (Figure 9a). In contrast, the distribution of pH values displays strong peaks alternating with patches of low values over the entire interior. Focusing on higher values alone, they characterize all the benches, as well as the altar. There are also two nearly symmetrical floor areas that seem to be associated with the northern and southern benches respectively. On both sides of the building, wider central areas with higher levels were also recorded. Connecting with the patio access is a narrow zone that extends over more than half of the gallery's width. To the east of the sacrificial stone there is another long and narrow zone running north to south (Figure 9b).

Three corridors of slightly lower values can be perceived in the carbonate chart. The first one runs between Column rows 2 and 3, from the open entrance area to the southern section of the eastern bench. The other two, situated between Column rows 4 and 5, and 6 and 7, respectively, maintain the same general orientation. Corridor 2 approaches the patio access and Corridor 3 targets the northern section of the eastern bench, while crossing the northern room on its way (Figure 9c). The faint nature of these corridors, in comparison to the use-wear areas observed in the House of the Eagle Warriors at Tenochtitlan (Barba et al. Reference Barba, Ortiz, Link, Luján, Lazos and Orna1996:Figure 4), is likely a result of different plaster mixtures. While central Mexican floors contain significant amounts of sand, and lime is a minor ingredient (Barba et al. Reference Barba, Blancas, Manzanilla, Ortíz, Barca, Crisci, Miriello and Pecci2009), plaster mixtures in the Maya area are primarily based on different types of oxidized and carbonated calcium (e.g., burnt limestone, sascab). Thus, even worn by foot traffic, carbonate tests of floor samples manifest less depletion.

Similar to pH values, the highest phosphate peaks were recorded covering the northern and southern benches of Structure 2D6. The altar samples also showed mostly higher results (n = 6; μ = 3.83). With just one exception, the floor is less enriched. The floor area with the highest values is located at the center of the gallery's southern sector, in close proximity to the zone where the patollis were found. Other areas with intermediate levels coincide with the sacrificial stone, the northwestern corner of the southern room and an elongated area at the center of the gallery's northern sector, which also seems to cross the northern enclosure's lateral wall (Figure 9d).

Protein residue analyses resulted in groups of higher values clustering around the sacrificial stone, as well as some meters to the south. Enrichments were also recorded in front of the northern bench, in the northeastern corner of the northern room, in the central area of the gallery's northern sector, again on both sides of the aforementioned dividing wall, and, to a minor extent, around the patolli (Figure 9e). In turn, carbohydrates were concentrated along the entrance area, to the north of the patollis and to the east of the sacrificial stone, as well as in the center of the northern room (Figure 9f).

The relative homogeneity in Structure 2D6's plaster color contrasts with architectural data. Excavation along the base of the enclosure walls resulted in observations of floor folding onto the vertical panel, as well as instances in which new segments of wall were just set atop the existing layer of plaster. Supporting evidence for the latter comes, above all, from the northern enclosure's lateral wall, which crosses residue stains from several chemical proxies. Altogether, this suggests that the gallery's floor was only partially renovated during later remodeling events. The last set of data, possibly related to the gallery's occupational history, concerns the widespread spots of elevated pH values. Based on observations made during the excavation, we suggest that the beam and mortar roof fell victim to a fire at the time of or after abandonment. The observed deposits of ashes could possibly mask previously formed activity areas.

Despite the apparent late spatial reorganization of Structure 2D6, there were no consistent chemical data that could assign a domestic function to the northern and southern enclosures. Even with the presence of several areas of enrichment, this kind of classification does not seem appropriate here. For example, cases of higher phosphate concentration located on the benches may suggest activities involving organic substances were carried out on these features. However, despite the correspondence of higher pH values, which may indicate the presence of fire, it is hard to imagine benches were places of food preparation. Maya art incorporates countless examples of scenes depicting lords on thrones and benches consuming food and beverages, but lack any individual dedicated to its preparation. In his analyses of Dzitas pottery of Structure 2D6, Méndez Cab (Reference Méndez Cab and Cobos2016:86–87) reported the presence of bowls, jars, and molcajetes. However, tecomate bowls presented the highest percentage (63 percent), suggesting large quantities of food were served at the structure. Evidence of food preparation is not-existent: no grinding stones were found in situ, and no hearths were unearthed.

The chemical enrichment around the patolli is also significant. They exhibit relatively high levels of phosphates, indicative of organic substances. In addition, the northern board is surrounded by spots of protein residues, and carbohydrates. Ethnohistoric and ethnographic sources report on the participation of men playing and drinking around patolli boards (Miller and Taube Reference Miller and Taube1993:132; Verbeeck Reference Verbeeck1998). Even though the distribution maps suggest additional activity areas across the gallery, our data support this perspective of a social activity involving foodstuffs.

At Tenochtitlan, Barba et al. (Reference Barba, Ortiz, Link, Luján, Lazos and Orna1996) perceive the House of the Eagle Warriors as a ritual building and considered the possibility of self-sacrifices and the worship of gods like Mictlantecuhtli in its interior. Ritual activity was also an interpretative proposal for Structure 2D6 as soon as the sacrificial stone was found. The analyses of chemical residues support this hypothesis too. Blood spilling should result in enrichment of organic material in general, and proteins more specifically. Our data sustain both arguments. Interestingly, the area of enriched protein concentrations associated with the sacrificial stone almost forms a complete circle. This kind of radial pattern is to be expected if blood is spilled by a larger body that is being mutilated. However, at this point, the presence of blood has yet to be confirmed, as the mineral matrix of the plaster floor poses difficulties for the corresponding specific tests. Finally, the altar presents moderate concentrations of phosphates and high pH values, suggesting the placing of a brazier or censer, similar to examples reported by Barba et al. (Reference Barba, Ortiz, Link, Luján, Lazos and Orna1996) at the House of the Eagle Warriors.

CONCLUDING REMARKS

The diverse ideas concerning the concept of masculinity allow us to understand how the construction of a hegemonic male gender ideology was used to support the power structure of the city of Chichen Itza. Through the naturalization of carved and painted discourses exalting the qualities of manliness, and the diversity of the archaeological record in the city, it is possible to establish a symbolic link between men and their role as warriors, priests, and dignitaries. Together, artwork and practices materialized the relationship between certain kinds of male bodies and legitimacy, power, and authority. However, it is not only in monumental art that we can find clues about the particularities of ancient Maya male gender ideology. It is the dynamic and persistent performance of a specific type of masculinity that creates the link between gender, ritual action, authority, and power. As performative action, Itza masculinity became featured in popular art, games, and diagnostic activity areas. The archaeological evidence obtained by excavating a gallery-patio structure shows how those spaces could have been used for purposes of communal living, training, amusement, sacrifice, and ritual practice of groups of men.

Although Structure 2D6 does not feature monumental artwork, its architectural characteristics may be confidently compared with other buildings at Chichen Itza and additional Mesoamerican cities. For example, the benches are quite similar to those found at El Palacio Quemado (Tula), El Templo de las Águilas (Tenochtitlan), and El Mercado and the North East Colonnade (Chichen Itza), which show rows of male individuals practicing ritual actions. Evans (Reference Evans2015:39) proposes that these images resemble processions performed in colonnaded spaces. In the case of Tula, Jiménez García and Cobean (Reference Jiménez García and Cobean2015) stress the military and sacred character of the processions depicted in structures like El Palacio Quemado, suggesting that the ceremonies strengthened the Toltec society's cohesion. At Chichen Itza, carved and painted scenes showing rows of male individuals in processions, sometimes converging to probable sacrifice or self-sacrifice scenes, always depict male figures, warriors, priests, and occasionally ballplayers (Baudez Reference Baudez2004; Cobos and Fernández Souza Reference Cobos and Souza2015; Ringle and Bey Reference Ringle, Bey, Fash and Luján2009).

Archaeological evidence found at Structure 2D6's gallery strongly suggests a place dedicated to male activities. It was a colonnaded, wide, semi-open space, exhibiting visibility and communication with public spaces at the central plaza of Chichen Itza. While the gallery occupies an intermediate state between the public and the private, the structure has additional, more private areas, such as the patio and the northern room that were hidden from the public's view. The gallery was a performative space, whose theatricality included a straight line between the throne (or altar) and the sacrificial stone, clearly visible from the front, and framed by the rows of columns. While this trapezoidal stone refers to heart extraction sacrifice, the similarity of Structure 2D6 to the House of the Eagle Warriors at Tenochtitlan, as well as other buildings at Chichen Itza, opens the question about self-sacrifice when considering the carved and painted images of processions of warriors walking toward zacatapayollis. On the other hand, the patolli at Structure 2D6 suggests the presence of groups of men involved in gambling. The carved butterflies that are part of the boards’ design emphasize the military and masculine character of the game, as this insignia is common in warriors at Tula, Chichen Itza, and Tenochtitlan.

Chemical analyses of the plaster floors evidence intense activities associated with the benches. Both the benches and the floor surrounding the patolli could have been the place for eating and drinking, and the high frequency of tecomate bowls suggests there was food for a large number of people. High pH values on benches and on the throne may be the result of braziers, similar to the House of the Eagle Warriors. Peaks of protein residues may indicate areas in which blood sacrifices were performed or meat-heavy dishes were eaten.

Structure 2D6 seems to conform to the message expressed in many other buildings at Chichen Itza, as well as greater Mesoamerica. Despite the lack of sculptured reliefs and painted murals, its spatial design, architecture, and associated features lead to a shared representation of masculinity: blood, gambling, warrior butterflies, and possibly feasts. A space for victorious warriors that were part of the powerful community of Chichen Itza and, at the same time, took place and action in and specific spot of the city as a differentiated group from other men at the site. Gallery-patios such as Structure 2D6 resemble Landa's descriptions of the big, whitewashed houses as places for the gathering and education of young men. Our discussion suggests that we should explore along those lines, testing this hypothesis in similar buildings, such as El Mercado, which also has at least one patolli and may still have many secrets to reveal about the sense of masculinity at Chichen Itza.

RESUMEN

La estructura del poder que subyace al control hegemónico que Chichén Itzá sostuvo sobre las tierras bajas mayas del norte ha sido debatido por décadas. En este trabajo, presentamos la idea de un discurso dominante acerca de masculinidades que jugaron un papel fundamental, tanto en la práctica como a nivel simbólico, entre las estrategias diseñadas para soportar esta capital prehispánica emblemática. Nuestra discusión de la evidencia arqueológica se enfoca en un espacio particular donde los hombres se reunían y realizaban rituales. Proponemos que los patios-galería, como la Estructura 2D6, sirvieron como lugares para la instrucción y la socialización de grupos de guerreros. La configuración arquitectónica de este edificio se asemeja claramente a la de lugares de reunión, tanto en Chichén Itzá como en otras ciudades mesoamericanas. En estos espacios, la iconografía asociada representa individuos masculinos en procesiones y prácticas rituales que incluyen el sacrificio y auto-sacrificio. Argumentamos que la galería de la Estructura 2D6 fue un espacio semi-público, performativo, cuya teatralidad combinó la alineación central de una piedra de sacrificio y un trono o altar con la presencia de varios tableros de patolli grabados en el piso del edificio. Los análisis químicos de muestras de superficie dan testimonio de la realización de actividades intensivas en torno a cada uno de estos rasgos.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The research described in this article was carried out with the permission of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH). We want to acknowledge the then president of the Consejo de Arqueología, the late Roberto García Moll, for all of his support. The excavations and analyses were conducted as part of the “Chichén Itzá: Estudio de la comunidad del clásico tardío” project, directed by Rafael Cobos, who we also want to thank for his support and encouragement. The field and laboratory work sustaining this article were funded by INAH and the Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán. In addition, the authors acknowledge Dylan Clark for his invaluable work at Structure 2D6 during the 2009 field season, and Luís Joaquín Venegas de la Torre and Rodolfo Canto Carrillo for the digitalization of maps and drawings. Finally, a huge thank you goes to all the wonderful workers from Piste, Xcalacoop, and San Felipe Nuevo, Yucatán, Mexico.