Introduction

The advent of the Eurodollar market in the 1950s is seen by scholars as representing a watershed moment in the development and evolution of postwar global finance.Footnote 1 Armand Van Dormael, for example, went as far as describing the emergence of the Eurodollar market as the “most significant monetary innovation since the banknote.”Footnote 2 The Eurodollar market, an offshore wholesale international money market denominated in dollars and the largest segment of the Eurocurrency market, emerged under the financially repressive Bretton Woods international monetary regime (1944–1971). It contributed to the demise of Bretton Woods and gave postwar financial globalization new scope and depth in the decades that followed against the background of the gradual relaxation and final removal of capital controls. The Eurodollar market was also blamed for systemic instability.Footnote 3 Furthermore, as Michael Moran argued, the Eurodollar market helped undermine the regulatory state, leading to the deregulation wave of the 1970s and 1980s.Footnote 4

Historical accounts of the origins of the Eurodollar market stress the pioneering role played by British clearing, merchant, and overseas banks in developing the market in the second half of the 1950s.Footnote 5 Catherine Schenk, for instance, wrote that “the origins of the [Eurodollar] market lay in the innovative approach of a single clearing bank,” the Midland Bank, which started accumulating Eurodollar deposits in mid-1955 as it reacted “to tight domestic liquidity” and cartel regulation in Britain that “restricted competitive bidding for domestic retail deposits.”Footnote 6 “The creation of the Eurodollar market in the City in the late 1950s,” Gary Burn claimed, “was a direct consequence of Britain’s financial elites’ determination to reestablish a regulatory order that was largely independent of the state.”Footnote 7 Pioneering this regulatory order, Burn asserts, was the Bank of London and South America (BOLSA), an overseas bank focused on South America.Footnote 8 Jeremy Green, on the other hand, emphasizes that merchant banks were the major force behind the Eurodollar market, although he does not provide any evidence to support his claim.Footnote 9 Nevertheless, it is a widely held view that merchant bankers started funding their loans with Eurodollar deposits after the UK Treasury adopted capital controls banning the financing of international trade with pounds in September 1957.Footnote 10

These interpretations, by suggesting that the Eurodollar market was a British innovation, overlook the fact that the market was developed at the same time by banks in Italy. Indeed, Italian banks were represented by contemporaries—Alan R. Holmes and Fred H. Klopstock of the New York Federal Reserve and Oscar L. Altman of the International Monetary Fund (IMF)—as being the first to have accumulated Eurodollar deposits in the very early 1950s,Footnote 11 several years before British banks.

The practice of funding foreign trade with offshore nonresident foreign-currency deposits was introduced into the Italian banking market by the country’s top banks: the Banca Commerciale Italiana (BCI), Credito Italiano, Banco di Roma, and the Banca Nazionale del Lavoro (BNL). The first three were defined by the banking law of 1936 as banche di interesse nazionale (banks of national interest [BIN]). They were owned by the Instituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale (Institute for Industrial Reconstruction [IRI]), the state-owned holding company. The BNL instead was Treasury owned.

Against the background of rapid economic change and industrialization, the BIN established a dual credit market in Italy. The first was in lire and subject to a banking cartel once this was reestablished in 1954, thus ending several years of intense competition; the other one was in foreign currencies, competitive and mostly related to foreign trade finance. Scholars of Italian banking have noted the surge in low interest rate foreign-currency credits, especially in the late 1950s.Footnote 12 Nevertheless, this development is mentioned en passant and without any reference to a dual credit market. This, thus, represents a new finding.

To cast light on the multiple origins of the Eurodollar market, this article investigates the motivations of Italian banks to fund their foreign-currency credits with foreign-owned dollar deposits (Eurodollar deposits). It argues that Italian banks established a link with the nascent Eurodollar market to meet firms’ requests for low interest rate credits and that these credits mostly financed foreign trade. It was a relationship that other European banks established with the Eurodollar market only in the 1960s. There is no evidence to suggest that other foreign banks integrated offshore finance into their banking strategies as early as banks in Britain and Italy or that they pioneered, like Italian banks, a new method of financing foreign trade.

The article also investigates how the Bank of Italy reacted to the banks’ decision to use offshore funds to finance foreign trade. It shows that, after initial opposition, the Bank of Italy endorsed the dual credit market as well as the relationship Italian banks established with the Eurodollar market. The Bank of Italy concluded in the second half of the 1950s that offshore banking enhanced the international competitiveness of Italian firms.

This article provides evidence of the evolution of the Eurodollar and Eurocurrency deposits held by Italian banks as well as their ratio to total foreign-currency deposits between 1955 and 1959. These deposits, while rather small in 1955 and 1956, have grown substantially since then. Furthermore, the nonresident foreign-currency deposits of Italian banks were higher than those of their counterparts in the City of London in 1957 and 1958, yet not in 1959. Explaining this turnaround is another aim of this article. Finally, this article provides evidence on the size of the Eurocurrency market in the late 1950s, drawing upon the secondary literature as well as the historical archives of the BCI, the Bank of Italy, including annual reports, and the Bank of France.

The article is structured as follows: in the following section, I first briefly discuss the nature of Eurodollar deposits, the channels through which these were accumulated, and the motivations leading European and American banks to enter the market in the late 1950s. In the third section, I highlight the dynamics of the Italian banking market in the 1950s. Evidence of the Bank of Italy’s attitudes toward the financing of foreign trade with foreign-owned foreign-currency funds is provided in the fourth section, and quantitative data on the foreign-owned foreign-currency deposits of Italian banks is presented in the fifth section, which also discusses the institutional changes in Italy’s international payment regime and foreign exchange markets that enabled the growing role of Eurodollar-based lending in the late 1950s and offers some qualitative evidence on some of the sources from which Italian banks borrowed. In the sixth section, I compare the nonresident foreign-currency deposits of Italian banks with those of banks based in London and Paris, propose a hypothesis of why the City of London overtook Italy in terms of Eurodollar deposits liabilities in 1959, and offer an approximate estimate of the size of Eurocurrency market in the late 1950s. The final section provides a summary and conclusion. I explain in the appendix how the size of Eurodollar and Eurocurrency deposits has been calculated.

The Nature of Eurodollar Deposits

The Eurodollar market mystified European central bankers even as they encouraged its development in the late 1950s and early 1960s by endorsing the market and providing it with funds.Footnote 13 What exactly Eurodollar deposits were was not an easy question to answer, however. The Bank for International Settlement (BIS), the main forum for central banks’ discussion on the Eurocurrency market, waited until 1965 to provide an answer. In its annual report for 1964, the BIS finally explained its thinking, with the caveat that “there are several difficulties involved in trying to say precisely what a Euro-currency is.”Footnote 14 In spite of this, the official view taken by the BIS was that a Eurodollar deposit was a “dollar deposit that has been acquired by a bank outside of the United States.”Footnote 15 Eurodollar deposits, the BIS added, were “used directly or after conversion into another currency for lending to a non-bank customer, perhaps after one or more redeposits from one bank to another.”Footnote 16 A more recent definition of Eurocurrencies is provided by Stefano Battilossi. Battilossi argued that as “a financial product, a Eurocurrency is simply time deposits (or a certificate of deposit, that is, a negotiable receipt of a deposit) yielding a fixed rate and with maturities ranging from overnight to 6 months.”Footnote 17 For the purpose of this article, Eurodollars are defined as dollar deposit liabilities at different maturities, from overnight to six months, accumulated by banks outside the United States.

European banks challenged U.S. banks’ grip on international dollar finance by paying interest rates on dollar deposits above U.S. regulation QFootnote 18 and by making dollar loans at rates lower than U.S. banks.Footnote 19 Eurodollars were accumulated through several channels. Schenk noted that the Midland Bank accumulated Eurodollar deposits starting in 1955 thanks to its London office, which maintained contact with Midland’s large network of foreign correspondents,Footnote 20 while Battilossi wrote that Italian banks “were reported” in the early 1950s “to have been heavy borrowers of Eurodollars from their European correspondents as well as from international companies.”Footnote 21 In another contribution, Battilossi noted that “up to the mid-1960s” Eurocurrency business “could be easily run by banks through their traditional international functions, normally a small department that offered services related to trade finance and dealt with correspondent banks.”Footnote 22 The banks’ foreign exchange departments were equally engaged in Eurodollar transactions. In the early 1960s, bankers, whether in Western Europe or in the United States, were extremely critical of the fact that foreign exchange departments of banks handled Eurocurrency transactions.Footnote 23 This criticism reflected the risk such transactions entailed because cross-border lending was treated as foreign exchange transactions.Footnote 24 The foreign exchange departments of European banks were linked in the 1950s first by a regional network, within the area of the European Payments Union (EPU) (1950–1958), then at the international level, once currency convertibility was achieved at the end of December 1958. In the process, an international interbank market developed also as a result of the reestablishment of correspondent bank relations in the 1950s. Little attention has been paid by historians to the efforts of European banks to rebuild their foreign correspondent networks at the end of World War II. Yet this holds a significance for the reemergence of postwar international banking. Foreign-currency brokers represented an additional channel through which Eurodollar deposits were transacted and accumulated by European banks. These communicated with and maintained contact between lenders and borrowers via telephone, telex, and cable.Footnote 25

Eurodollar deposits did not represent a postwar novelty. Postwar bankers who began their careers in the interwar years, or even earlier, might have remembered that an embryonic Eurodollar market in continental Europe was cut short by the onset of the Great Depression.Footnote 26 What was new about the postwar Eurodollar market was its size and scope and the structural implications as it changed European and American banking practices, especially in the 1960s.Footnote 27

British merchant and overseas banks entered the Eurodollar market to circumvent the capital controls of late 1957, which banned sterling credits to nonresidents,Footnote 28 and to lend to British local authorities, as this article will show. Offshore banking enabled British merchant and overseas banks to sidestep the capital controls and to decouple their international bank business from the dynamics of the British balance of payments. However, the Bank of England tightly regulated inflows of Eurocurrencies.Footnote 29 Eurodollar deposits were borrowed by American banks in the late 1950s to offset to the extent possible the loss of domestic corporate deposits due to U.S. interest rates rising above regulation Q.Footnote 30 French banks were mainly in the Eurodollar market to add interest rate and foreign-currency arbitrage to their international banking business. However, most French banks entered the Eurodollar market in 1960 to take over, as the Banque de France explained in 1962, the role of their Swiss counterparts, which decided in 1960 to “strictly limit their operations in the Eurodollar market.”Footnote 31 Swiss, Dutch, and German banks were prominent in the Eurodollar market in the late 1950s as suppliers.Footnote 32 Altman, without providing evidence, suggested that German banks also borrowed in the Eurodollar market in the late 1950s to circumvent high interest rates in Germany.Footnote 33 Italian banks, therefore, were in a league of their own with regard to their relationship with the Eurodollar market, in that they were alone in accumulating Eurodollar deposits to finance foreign trade in a framework of competition in the 1950s.

The Bank of Italy’s endorsement of the use of foreign funds by Italian banks to finance foreign trade has already been mentioned. The role of the Bank of England in enabling London’s rise as the world’s leading Eurodollar center has been explored in an expansive literature.Footnote 34 Like the Bank of England with regard to the City of London, the Banque de France endorsed the establishment of the Eurocurrency market in Paris to enhance its financial center’s international reputation.Footnote 35

The Eurodollar market emerged against the background of sustained economic growth in Western Europe and the transformation of the dollar gap of the late 1940s and early 1950s into a dollar glut by the end of the decade. Postwar economic recovery, re-industrialization, modernization, and economic integration were promoted by European governments through cooperation at the international and the regional level. The Marshall Plan (1948–1952) provided governments with badly needed dollars to finance imports of American industrial technology in order to enhance the international competitiveness of European firms. The liberalization of Western European trade and payments was instead promoted by the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC), which was established in 1950 within the framework of the Marshall Plan.Footnote 36 European economic cooperation was further strengthened by establishment of the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1957. Its six founding members pursued the removal of all barriers to the movement of goods, services, capital, and labor in order to further strengthen economic cooperation on the Continent.Footnote 37 Unwilling to commit to the EEC experiment, the remaining seven OEEC members established the European Free Trade Area in 1960. Overcoming the dollar gap—namely, the low level of official dollar holdings of Western European countries—was a major aim of the Marshall Plan. The Marshall funds were replaced by the various foreign economic assistance programs launched by the U.S. government during the 1950s. Then in 1957, to the astonishment of many observers, the U.S. balance of payments entered into deficit.Footnote 38 The dollar buildup abroad and the increased demand for foreign trade finance following the liberalization of intra-Western European trade and the establishment currency convertibility in the late 1950s represented two important growth factors of postwar offshore banking.

The Dynamics of the Italian Banking Market in the 1950s

Eurodollar lending was introduced by the big banks in Italy as the economy underwent rapid structural change and internationalization. Franco Amatori characterized the economic change taking place in the 1950s as an “industrial take-off.”Footnote 39 Exports, while not initially the main growth engine, became the driving force of the economic miracle (miracolo economico) Italy experienced in the 1950s.Footnote 40 Efforts to boost exports to the Middle East, Asia, and South America were significant, although Italian exports headed mainly toward Western Europe.Footnote 41 Imports also developed significantly, thanks to the removal of import quotas in 1952, even if tariffs remained among the highest in Western Europe.Footnote 42 Price stability was another facet of Italy’s economy in the 1950s. Policies targeting price stability were implemented by the Bank of Italy starting in September 1947, when the discount rate was raised in order to reverse the inflationary dynamics that followed the war’s end in 1945.Footnote 43 The Bank of Italy raised the discount rate from 4.4 percent to 5.5 percent in September, lowered it by 1 percent in April 1949, and by another half a point in April 1950, henceforth holding it stable until June 1958, when it was lowered to 3.5 percent.

The high cost of money, although necessary for balance of payments reasons and non-inflationary growth, was contested by Italian firms. Large and medium-sized firms added strong pressure on the banks for loan accommodation at interest rates “more closely related to those outside of Italy,” as Altman noted.Footnote 44 Firms also shopped for credits with multiple banks. As Giuseppe Conti reported, “It was convenient for firms to borrow with several banks in order to make them compete with each other and to obtain the best credit conditions from each of them.”Footnote 45 The weakening of screening and relationship banking were important consequences of firms’ relationships with the banking system.Footnote 46 The bankers, however, also courted the firms. Alfredo Gigliobianco, Giandomenico Piluso, and Gianni Toniolo noted that the slack demand for bank loans in 1946–1947, 1952, and 1958–1959 sent bankers to knock “at firms’ doors rather than the entrepreneur searching for financing.”Footnote 47 The bankers’ unsolicited overdraft offers are understood by Gigliobianco, Piluso, and Toniolo as evidence of the strong bargaining position of firms vis-à-vis the banks.Footnote 48

The strong bargaining position of firms reflected the high ratio of reinvested profits and cutthroat intra-bank competition. The Italian banking market was nominally regulated by a banking cartel setting interest rates payable on deposits and loans. Nevertheless, bank competition in the late 1940s and early 1950s led to cartel violations and, ultimately, to the cartel’s de facto downfall. Competitive lending occurred in lire and foreign currencies and extended to relations with foreign correspondents. How the credit market functioned during those years was explained by Raffaele Mattioli, the managing director of the BCI, in September 1954:

Money—the fungible commodity par excellence—was becoming something extremely individualized, with prices varying from case to case. In fact, we had arrived at fixing the price through individual agreements according to the importance of the customer, his economic weight, the extent of his relations, and also his cunning and the boldness of a competitor. In the resulting confusion, a peculiar form of “annuity” was created in favor of certain customers and it became increasingly difficult to predict where it would end up.Footnote 49

The BCI lambasted the competition between the banks in regard to relations with foreign correspondents in a letter sent to the Associazione Bancaria Italiana (Italian Banking Association) in late May 1953. “Indecorous,” “foolish,” and a “present to foreigners” are some of the words the BCI used to denounce the “state of unease in our banking system.”Footnote 50 To bring the banks to the fold, the BCI suggested a written agreement setting equal rates for correspondent services. It also suggested that the agreement should be upheld by the Ufficio Italiano Cambi (Italian Foreign Exchange Office [UIC]).Footnote 51 The BCI was also a major force behind the accordo interbancario, the interbank agreement of 1954 that reestablished the cartel. Giorgio Albareto suggested that recurrent violations led to tighter cartel regulations in 1960.Footnote 52 Furthermore, Albareto noted that the competition in the lira loan market shifted from price to size once the cartel was reestablished, and this is also argued by Gigliobianco, Piluso, and Toniolo.Footnote 53

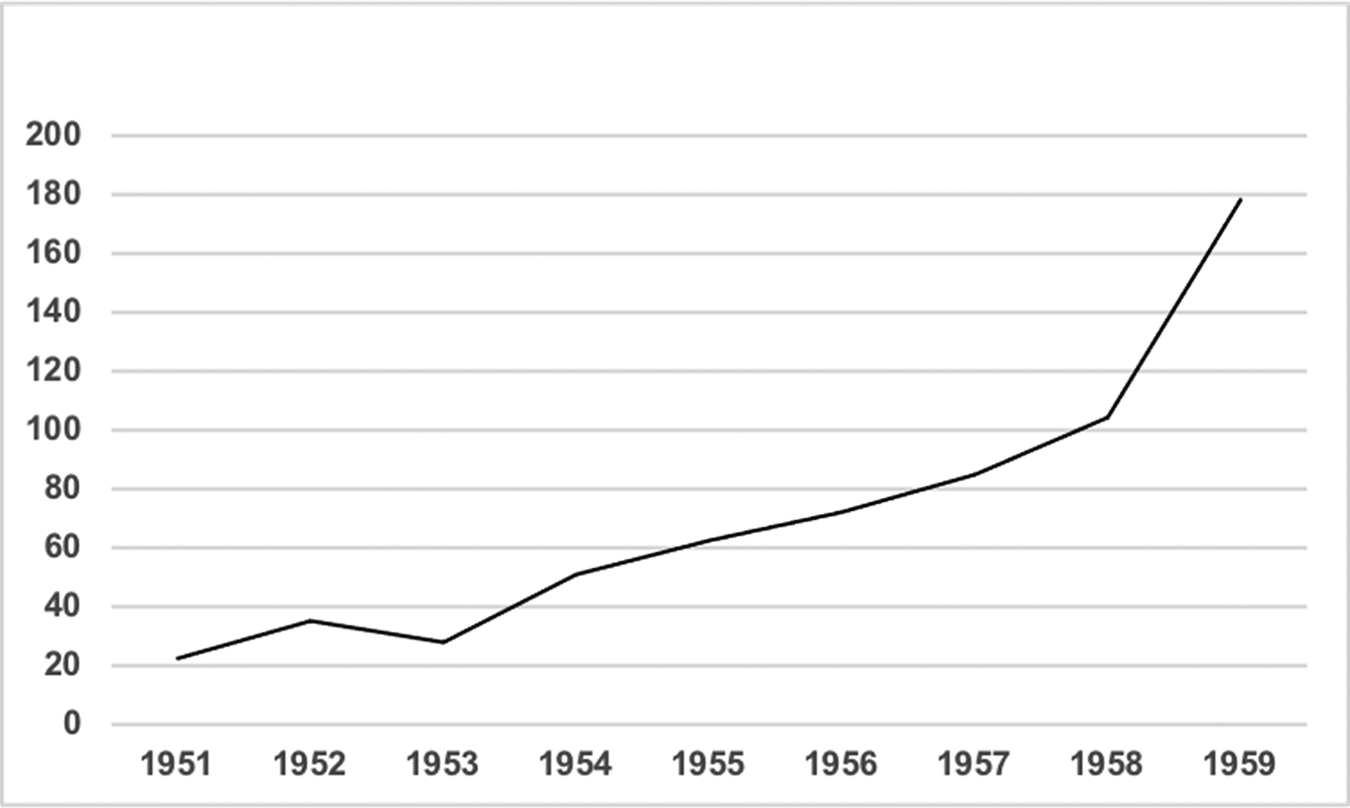

Lending in foreign currencies remained outside the remit of the intrabank agreement, however. Whether deliberately or not, a dual credit market was set in motion by the banks’ decision: one in lire and cartelized, in spite of frequent violations, and another one, until it was finally cartelized in March 1960, competitive and in foreign currencies.Footnote 54 Figure 1 plots the evolution of foreign-currency lending during the 1950s. While standing at $200 million in 1951, the market deflated the following year, stagnated in 1953, and started growing from 1954 onward, and especially since 1957.

Figure 1. Foreign trade–related foreign-currency credits of Italian banks, 1950–1959 ($ million).

Source: Bank of Italy, Relazione Annuale, 1950–1959.

The foreign-currency credit boom starting in 1957 was almost exclusively financed with Eurodollars and Eurocurrencies, which, as will be shown in the fifth section, reached critical size the previous year. Unlike deposits in lire, reserve requirements were not applied to foreign-owned deposits. These funds, therefore, held the significant competitive advantage of keeping competitors at bay while expanding the banks’ client portfolios.

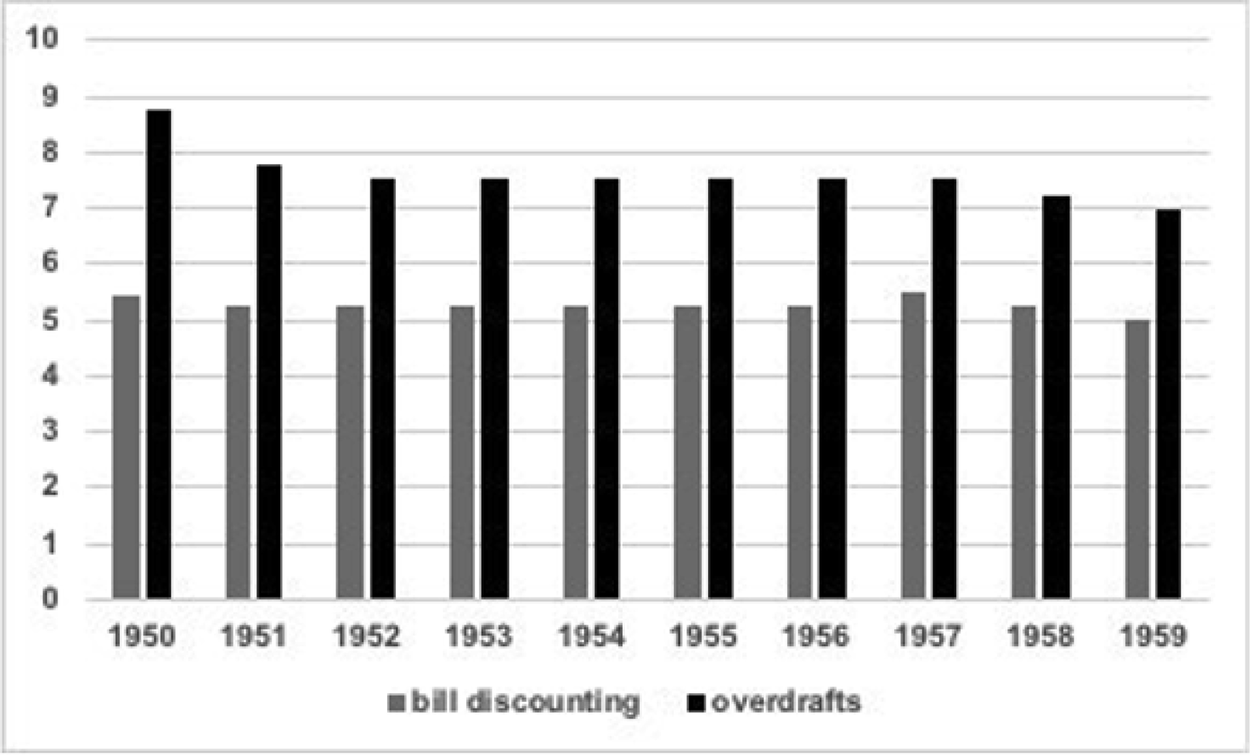

Foreign-currency advances were issued at interest rates that were several percentage points lower than advances in lire—the cartel-regulated interest rates are shown in Figure 2. For instance, dollar advances carried an interest rate of 3 percent–3.5 percent in 1954,Footnote 55 4.5 percent in 1958, and 5.5 percent in 1959,Footnote 56 even if the banks continued in special cases to provide their largest clients with dollar advances at interest rates of 3.5 percent and thus at a loss.Footnote 57

Figure 2. Minimum cartel-regulated interest rates in Italy, 1950–1959.

Source: “Statistiche Creditizie,” in Cotula, ed., Stabilità e Sviluppo negli anni Cinquanta, 3, table 12, p. 940.

The average costs of collecting funds in the domestic market are illustrated in Figure 3, while Eurodollar deposits interest rates are presented in Table 1, which shows the prevailing rates in London between 1956 and 1959. As Table 1 illustrates, interest rates on Eurodollar deposits in the second half of the 1950s were above interest rates on lira deposits. The surge in foreign-owned deposits in the late 1950s triggered a significant decline in foreign credit lines, as will be shown in the fifth section.

Figure 3. The average cost of banking funds in Italy, 1950–1959 (interest rates of a big national bank).

Source: “Statistiche Creditizie,” in Cotula, ed., Stabilità e Sviluppo negli anni Cinquanta, 3, table 12, p. 940.

Table 1. Eurodollar deposit interest rates in London, 1956–1959 (%)

Source: Holmes and Klopstock, “The Continental Dollar Market: A Report Based on Visits to European Bank in June 1960,” marked “Confidential,” August 26, 1960, BFA 1495200501-577.

The emergent offshore markets also enabled the top banks to mitigate the “crisis of involution”Footnote 58 they were dealing with because of insufficient capital. The lack of bank capital was a salient issue in the relationship of the BIN with IRI due to the latter’s reluctance to comply with the banks request for additional capital until 1959.Footnote 59 “From whatever angle we look at our situation” IRI’s managers were told by the BCI, “we are struck by this ‘bottleneck,’ this ‘bottleneck’ of capital, which limits the expansion of deposits, restrains the natural provision of credit, and imposes continuous and dangerous efforts on the treasury.”Footnote 60 The Banco di Roma and Credito Italiano were in a position similar to that of the BCI. A comparative analysis of March 1957 by the BCI found that the capital of the BIN as a group, although seven times larger in 1956 than in 1938, was far behind that of the other categories of banks, which during the same years increased by a factor of twenty-five.Footnote 61 Another study of November 1958 underscored the significant contraction of the aggregate deposits of the BIN since 1954, when the decline was set in motion. Whereas the BIN ranked first as a group in 1954, they ranked fourth in 1956. Between 1954 and the end of May 1958, the ratio of deposits of the BIN to total deposits declined from 23.4 percent to 19.8 percent.Footnote 62

The BCI was Italy’s leading international bank. In 1957, it financed a third of Italian foreign tradeFootnote 63 and played, according to Guido Carli, the Bank of Italy’s governor between 1960 and 1975, a crucial role in the development of the export industry.Footnote 64 The BCI’s trade-related, mostly dollar credits are illustrated in Figure 4. The BCI operated abroad through a network of representative offices in the world’s leading international financial centers, through a subsidiary, the Banque française et italienne pour l’Amérique du Sud (Sudaméris), in South America and through minority shareholdings in Western European and Middle Eastern banks.Footnote 65

Figure 4. Approximate size of the trade-related mostly dollar credits made by the BCI, 1951–1959 ($ million).

Source: Verbali Consiglio di Amministrazione, AS BCI, 1951–1959.

The BNL was a newcomer to international banking. The decision to develop as an international bank was taken in late 1949, soon after the BNL’s board of directors was reestablished.Footnote 66 Under Giuseppe Imbriani-Longo as managing director (1945–1967), the BNL developed a broad network of representative offices and subsidiaries in the United States, Western Europe, and South America.Footnote 67 These efforts paid off: by the end of the decade, 15 percent of foreign trade was financed by the BNL. Taken together, therefore, the BCI and the BNL financed close to half of Italy’s foreign trade. The two banks, then, were Italy’s Eurodollar pioneers.

The BCI and the BNL continued to expand their multinational banking network in the 1960s, parallel to their integration into the Eurodollar market. By the end of the 1960s, Eurodollars were the main source of financing Italian foreign trade. In 1967, for example, 75 percent of imports were financed through the Eurodollar market, compared with only 12 percent of exports.Footnote 68 Eurodollar lending in Italy in 1969 was “structurally linked to imports,” the Bank of Italy observed in its annual report for that year.Footnote 69

The Bank of Italy’s Attitude toward Financing Foreign Trade with Foreign Funds

The dual credit market in Italy developed because it received the endorsement of the Bank of Italy, even if the Bank twice banned foreign-currency lending funded with foreign-owned dollar deposits only to reverse both bans. The first ban of October 1954 was adopted because, among other factors, such lending:

led to an inflow of foreign currency … in advance of the actual settlement of exports and consequently caused, on the one hand, an increase in monetary circulation and, on the other hand, an increase of the overdraft by the UIC on the lire account it holds with [the Bank of Italy], with a related increase in interest rates.Footnote 70

The Bank of Italy, as already mentioned, had focused since 1947 on monetary stability. Donato Menichella, the governor of the Bank of Italy from 1948 to 1960, believed that monetary stability would strongly benefit Italy’s industrial modernization and economic integration in the context of a stable balance of payments.Footnote 71 The Bank of Italy therefore carefully monitored the evolution of the balance of payments. Nevertheless, the bank reversed its ban on short-term foreign-currency inflows soon afterward due to the phalanx of complaints raised by firms that lobbied against the ban.Footnote 72

The bank’s views on such lending changed in the following years. It recognized in 1957 that foreign-currency inflows increased the “competitiveness of the Italian economy.”Footnote 73 Italian banks were therefore authorized to “continue to finance imports and exports using foreign currencies of which they [acquire] from foreign correspondents. In this way Italian companies have been given the opportunity to obtain credit at the lowest international interest rates.”Footnote 74

The precipitating factor leading to the second ban was the sudden withdrawal of funds by Swiss banks in late 1959. According to Holmes and Klopstock, who related the episode, Swiss banks recalled in November a substantial part of the Swiss francs and dollar claims on Italian and British banks, as they needed the funds for end-of-year window-dressing operations and cash demand.Footnote 75 Holmes and Klopstock wrote that, while the British banks meet the Swiss demands without any problem, Italian banks reimbursed the Swiss with funds drawn on the UIC. Holmes and Klopstock alleged that the UIC’s intervention was probably indicative of the fact that the banks had used the short-term funds borrowed in Switzerland to grant loans at longer maturities.Footnote 76 This is doubtful. Indeed, the Bank of Italy explained that it intervened to “avoid forcing Italian banks to request sudden repayments [of foreign-currency loans] from customers.”Footnote 77 In January 1962, Carli told Julien‐Pierre Koszul, the general director of Foreign Services of the Banque de France, that the UIC swaps supplied the banks with $77 million in November.Footnote 78 The Bank of Italy also decided to cut off the banks’ links to the Eurodollar market and to have them finance foreign trade by drawing on official reserves. Instructions thus were given to the banks in August 1960 to eliminate their net foreign debt at the end of December, a deadline that was then extended to the end of January 1961,Footnote 79 and to shift the sources of funding foreign trade from Eurodollar deposits to official reserves.

Unfortunately, neither the board minutes of the BNL nor those of the Banco di Roma provided any hint of managers’ attitudes regarding the Bank of Italy’s decision. The view of the BCI, however, was that such a heavy-handed intervention went too far and risked damaging the banks’ relations with foreign banks. Mattioli, in fact, told IRI president Giuseppe Petrilli in March 1961 that the Bank of Italy’s new course of action risked creating a “‘closed circuit’ [….] which limits its functionality and consequently, also causes difficulties with foreign banks, disappointed not to see us use the credit lines that had opened up to us as in the past.”Footnote 80 In addition, the bankers’ minds were set on competing with other foreign banks in international banking. The bankers “anxious”Footnote 81 and “legitimate desires to participate more widely in the field of international trade finance”Footnote 82 were supported by the Bank of Italy. The Bank of Italy, in fact, encouraged the banks to build their Eurodollar asset portfolios by providing them, thanks to the UIC swaps, with official dollar reserves in exchange for domestic deposits. Then, in February 1961, the Bank of Italy removed the ban on financing residents with foreign funds.Footnote 83

The UIC swaps became an important tool for the Bank of Italy during the 1960s, as they allowed it to pursue three objectives. First, by using the foreign-currency swaps to recycle official reserves in the Eurodollar market via the banks, the Bank of Italy was returning to international markets the liquidity subtracted due to the balance of payments surpluses of 1958–1962 and 1965–1971, thus helping to ease international pressure on the dollar.Footnote 84 Second, the UIC swaps helped drain domestic liquidity, which was required to neutralize the inflationary effects of the large balance of payments surpluses. To preserve the domestic monetary stability achieved by Menichella in the 1950s, the UIC swaps, like those of the Bundesbank, required that the banks cede domestic deposits in exchange for foreign-currency deposits. Finally, and equally important, the swaps were aimed at insuring against a replay of the Swiss incident, as they insulated “the domestic market from the potentially disturbing effects of certain short-term capital movements.”Footnote 85 In September 1963, in fact, Emilio Ranalli, head of the foreign relations department, told Carli that the banks continued to borrow Eurodollar “deposits at sight and at one month, in order to lend at a longer maturity, without any sudden withdrawals of funds from abroad being a cause for concern.”Footnote 86 Ranalli noted that in case the banks failed to reimburse foreign credits by additional borrowing in the Eurodollar market, they could, to that end, “turn to [the UIC] to use the spot and forward plafond.”Footnote 87 The UIC, therefore, became the lender of last resort. The Swiss withdrawals marked a point of connection between the 1950s and the 1960s, because the debate they triggered led to the banks’ integration in the Eurodollar market as both lenders and borrowers.

Eurocurrency Deposits in Italian Banks

The previous two sections discussed the main features of the Italian banking market in the 1950s, the motivations of the top Italian banks to accumulate nonresident foreign-currency deposits, and the views of the Bank of Italy regarding the use of these funds to finance foreign trade. In this section, I provide quantitative evidence on the size of the aggregate Eurodollar and Eurocurrency deposits in Italy. Furthermore, I explain the institutional changes enabling their rapid surge in the second half of the decade and provide some qualitative evidence on some of the sources of these funds.

According to the Bank of Italy, foreign-owned dollar deposits grew in 1951 and “increased consistently” in 1952.Footnote 88 Altman, on the other hand, wrote that reports abroad that Italian banks borrowed Eurodollar deposits were already circulating in 1950 and 1951.Footnote 89 According to Altman, “Banks in Italy were, perhaps, the first in Europe to borrow dollars in what has since come to be called Euro-dollar transactions.”Footnote 90 Finally, he implied continuity between these first reports and the borrowing by Italian banks in the late 1950s, noting that the demand for Eurodollar deposits increased “substantially in 1957 and 1958 and even more after the lira and other major European currencies were made convertible at the end of 1958.”Footnote 91

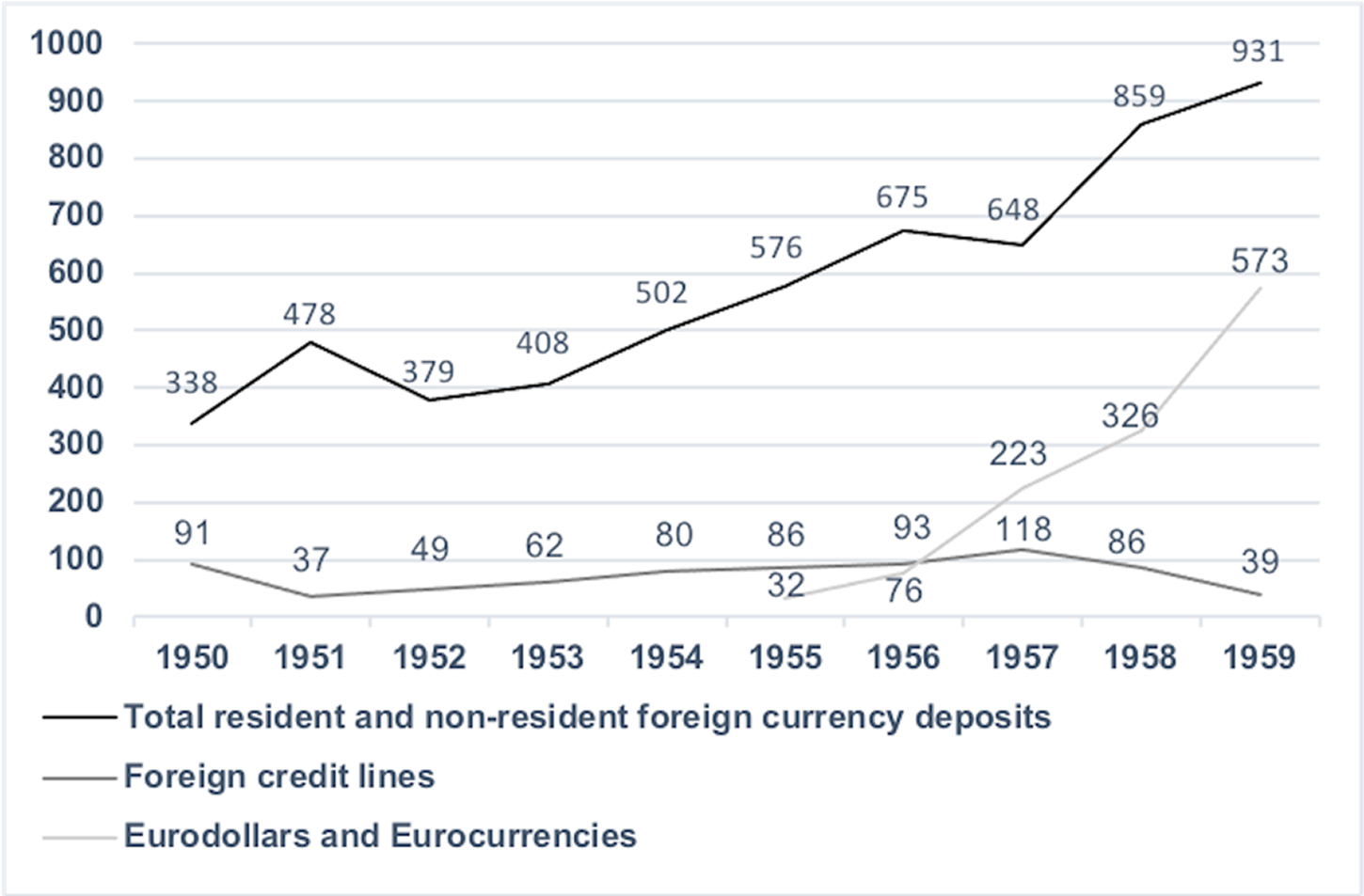

Figure 5 illustrates the evolution of Eurodollar and Eurocurrency deposits held by Italian banks between 1955 and 1959, including foreign credit lines and total foreign-currency deposits in the 1950s. It underlines that Eurodollar funds surged significantly in 1956 when they stood at $76 million or 16.4 percent of total foreign-currency deposits. Ersilio Confalonieri, a BCI board member, commented on the surge:

The occurrence of a fact, which is new and curious for me…. namely, the supply by foreign banks of larger than before amounts of foreign currency, [this] in my opinion, represents a comfortable element, also because it can be interpreted as a major trust of foreign banks in our country.Footnote 92

Figure 5. Total resident and nonresident foreign-currency deposits, foreign credit lines, and nonresident foreign-currency deposits of Italian banks, 1950–1959 ($ million).

Source: Bank of Italy, Relazione Annuale, 1950–1959, 1965.

By 1959, offshore foreign-currency deposits accounted for an impressive 73 percent of the total foreign-currency deposits held by Italian banks. The steep decline of foreign-currency credits and the parallel sharp increase in Eurodollar deposits has already been mentioned. It can be seen in Figure 5 that foreign credit lines nosedived by two-thirds following 1957. In other words, in just two years, foreign credit lines shifted from the highest to the lowest volume in the decade. Table 2, on the other hand, illustrates that American banks had the most to lose from the decline in the use of foreign credit lines by Italian banks.

Table 2. U.S. credits and acceptances to Italian banks and firms, 1955–1959 ($ million)

Source: Holmes and Klopstock, “The Continental Dollar Market: A Report Based on Visits to European Bank in June 1960,” marked “Confidential,” August 26, 1960, BFA 1495200501-577.

The surge in Eurodollar deposits since 1956 coincided with Italy adopting a new foreign-currency law that year and with the establishment of foreign-currency convertibility in Western Europe in December 1958. The foreign exchange law decentralized and privatized the foreign exchange market in order to catch up with similar legislation in the EPU area. It enabled the multilateralization of payments in lire within the EPU, thus making the lira convertible within the area, and integrated Italy’s foreign exchange market within the EPU area’s foreign exchange markets. The end of bilateralism and beginning of multilateralism in Italy’s payments relations began in August 1956, when Italy joined the multilateral payments system for transactions with Brazil (the Hague Club) and Argentina (the Paris Club) and signed “agreements in multilateral lire” with almost all of its trading partners.Footnote 93 Furthermore, the banks were authorized in September 1957 to also receive and extend credit lines from banks outside the EPU area—hitherto, credit lines from the dollar area required ministerial authorization.Footnote 94

An obviously important question is the source from which Italian banks borrowed dollar deposits. This is a difficult puzzle to solve. It has not been undertaken by historians of early British Eurodollar banking.Footnote 95 European central bankers only learned about the geography of the Eurodollar market in 1963, when the first statistics of the Eurodollar market were collected by the BIS. Nevertheless, there seems to have been consensus among contemporaries that French banks and banks from the Communist bloc were important Eurodollar lenders early on. Scholars also agree, yet without providing any evidence, that Communist bloc countries were among the earliest suppliers of Eurodollars.Footnote 96

Information on Eurodollar lending by French banks emerged from two different sources. First, there is Altman, who noted that French banks were the sources of the first Eurodollar deposits Italian banks allegedly borrowed in 1950 or 1951.Footnote 97 Second, Chase National and Schroder informed the Banque de France in early December 1957 that “French banks lend dollars to German and Italian banks.”Footnote 98 Holmes and Klopstock also point at Communist central banks and foreign trade banks as suppliers of Eurodollars. They wrote that “inquiries were made by these banks in the mid-1950s among potential borrowers, notably the Italian banks, whether these would be interested in taking on dollar balances for limited time periods at attractive interest rates.”Footnote 99 They added that “several Italian banks were quick to see to the advantages of covering their dollar requirements out of these offerings.”Footnote 100 The Banque de France believed that the Soviet-owned but Paris-based Banque Commerciale pour l’Europe de Nord (BCEN) was an important Eurodollar supplier and Eurodollar innovator. It traced that supply to “around 1953/1955” and explained it as being driven by BCEN’s wish to lend dollar deposits to foreign correspondents in order to “get the best returns on them.”Footnote 101 Allegedly, the BCEN accumulated dollar deposits by selling Soviet gold on the London gold market and kept the proceeds of these sales to finance Soviet imports.Footnote 102 Evidence that Soviet-owned banks lent Eurodollars is provided by the BCI. For instance, the BCI’s executive committee noted in March 1957 that the bank had borrowed from the BCEN “since many years between $10–30 million.”Footnote 103 The committee also noted the $2 million deposit placed that year by Gosbank, the Soviet state bank, with the BCI head offices in Milan.Footnote 104

If French and Communist banks were important lenders in the early to mid-1950s, by the late 1950s, Italian banks could borrow funds from Swiss, Dutch, and German banks.Footnote 105 The Bank of Italy, in fact, noted that the threefold increase in foreign credit lines and nonresident deposits in 1957 over 1956 was due to borrowing mainly in the “United States and the OEEC countries, excluding the United Kingdom with which … there was a decrease in the use of available credit.”Footnote 106

Nonresident Foreign-Currency Deposits in Italian Banks versus London and Paris Banking Institutions

Holmes and Klopstock noted that Italian banks also lent in the Eurodollar market. The two economists wrote that banks “in Paris and Milan do a fairly substantial business in ‘jobbing’ dollar and other deposits.”Footnote 107 The BCEN and the Société Générale were the most active Eurodollar banks in Paris, while in Milan the BNL dominated. Regarding the BNL, Holmes and Klopstock wrote that its Milan branch engaged “actively in interest arbitrage and serve[d] as a clearing centre for its headquarters and all other branches, covering their exchange needs or disposing of surplus exchange.”Footnote 108 The two Americans added that “several other Milan banks also engaged in such operations, but on a smaller scale.”Footnote 109 They were quite likely referring to the already discussed foreign-currency swap lines that were activated by the UIC in November 1959. Holmes and Klopstock, however, also underlined the City of London’s dominant role in offshore finance. They wrote that, as of June 1960:

Approximately a dozen banks—merchant banks, foreign banks, British overseas banks but not the clearing banks—serve as intermediaries in accepting and putting out foreign exchange deposits, quite apart from using the deposits acquired for their own trade financing needs and for other ordinary banking transactions.Footnote 110

They further noted that the dominant London Eurodollar “jobber” was BOLSA, but that Brown Shipley & Company and Samuel Montagu were also active in Eurodollar banking.Footnote 111

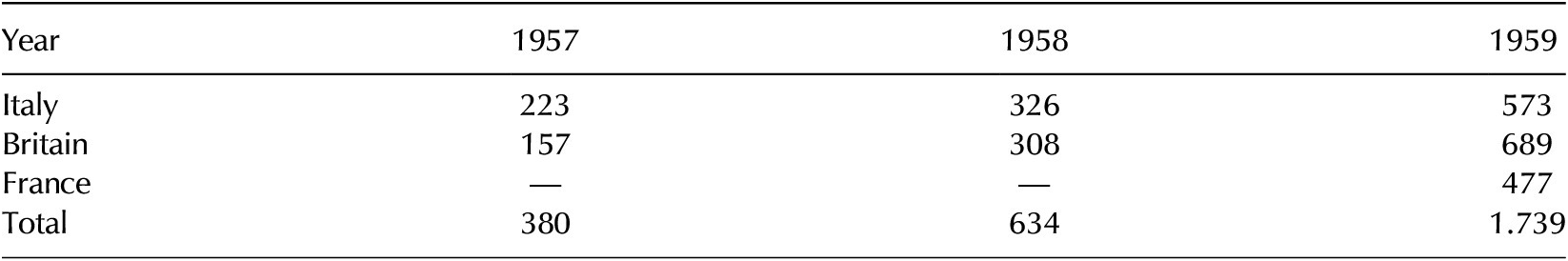

Although the City of London dominated Eurodollar transactions by the time Holmes and Klopstock wrote their study in the summer of 1960, it ranked first in offshore banking only in 1959. As shown in Table 3, the nonresident foreign-currency deposit liabilities of Italian banks outstripped those of banks based in the City of London by $66 million in 1957 and by $18 million in 1958. The Eurocurrency deposits of the City, however, increased substantially in 1959, outstripping by $116 million those of Italian banks, which also grew that year.

Table 3. Eurocurrency deposits of Italian-, French-, and London-based banks in 1957, 1958, and 1959 ($ million)

Sources: Author’s calculations; “Les Banque Françaises et le marché de l’Euro-dollar,” September 20, 1962, DGSE 1495200-501; Roberts, Take Your Partners.

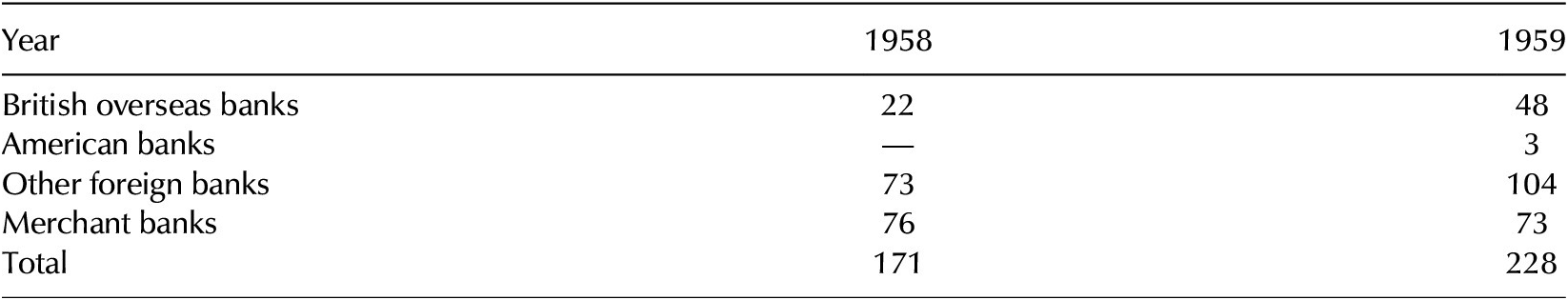

The near doubling of the Eurocurrency deposits in the City in 1958 over 1957 related to American banks entering the Eurodollar market and to an increase in borrowing by British local authorities rather than because of increased demand for offshore finance by nonresidents other than American banks. British local authorities borrowed $171 million in 1958,Footnote 112 while American banks borrowed $51 million.Footnote 113 Summed up, the liabilities of these two groups of borrowers stood at $221 million, or 57 percent, of a total of $308 million in Eurocurrency liabilities the City held in 1958, as calculated by Roberts based on Bank of England data.Footnote 114 The remaining $87 million roughly coincided with the Eurodollar deposits held by BOLSA, which Burn claims stood at $106.2.Footnote 115 BOLSA thus seems to have held 35 percent of the total Eurodollar deposits in 1958 and 27 percent in 1959—according to Burn, BOLSA held $190.91 in Eurodollar deposits that year.Footnote 116 British local authorities remained important borrowers in 1959, when they borrowed $228 million.Footnote 117 The Bank of England data on foreign borrowing by local British authorities in 1958 and 1959 also provides evidence on the lenders, illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4. Foreign currency loans to British local authorities in 1958 and 1959 ($ million)

Source: “Deuxième réunion sur l’Euro-Dollar à Bale 9–11 Novembre,” November 14, 1963, BFA 1495200501-578.

Table 4 makes for some fascinating reading. First, it confirms what contemporaries argued and historians have noted: namely, that a lot of Eurodollar deposits were drawn to London because of demand by British local authorities.Footnote 118 Second, it shows that the major lenders to British local authorities were foreign banks and British merchant banks, while British overseas banks ranked as the less important lenders. Data on the share of Eurodollar and Eurocurrency deposits of the merchant banks as a group is unfortunately lacking. It is nonetheless striking that as a group, merchant banks were major lenders to British local authorities, especially given the heavy emphasis put on the fact that these banks entered the Eurodollar market to overcome the capital controls of September 1957.Footnote 119

American banks took an even larger share of Eurodollar deposits in 1959. Holmes and Klopstock noted that the dollar deposit liabilities of American banks, mostly to their London branches, increased between April 1959 and June 1960 “by as much as $670 million.”Footnote 120 Holmes and Klopstock explained that the Eurodollar market helped American banks offset the loss of time deposits, which that year “began really to hurt.”Footnote 121 According to Holmes and Klopstock, “much of the money” American banks borrowed offshore came from European central banks “that until 1959 used to be important holders of time deposits in New York City banks.”Footnote 122 American banks played a crucial role in the stunning growth of the Eurodollar market in the second half of the 1960s when they arrived en masse in London. Their massive move offshore has been explained by literature as an “escape” from the capital controls adopted by the United States starting in 1963.Footnote 123 However, as seen, U.S. banks had been major actors in Eurodollar banking since 1959. Nevertheless, only ten U.S. banks had branches in London in 1960.Footnote 124 The bulk of American banks thus only played a role in later growth of the Eurodollar.

If the data presented in Table 4 are to be taken as an approximate estimate of the size of the Eurocurrency market as this took off in the late 1950s, then the market’s size in 1957 stood at $380 million and at $634 million in 1958. The market was even larger in 1959, standing at $1.739 billion, but this estimate also includes French nonresident foreign-currency deposits. Therefore, the size of the Eurocurrency market in 1959, even if approximate, was only $200 million short of representing half of the U.S. balance of payments, which that year stood at $3.8 billion.Footnote 125 The market, thus, was larger than the $500 million estimate by Chase Manhattan and the $800 million estimate by Maurice Theron of the Banque de France.Footnote 126 Even the $1 billion estimate of Klopstock and Holmes is off the mark.Footnote 127

Conclusion

This article casts a new light on the rise of the Eurodollar market. It argues that the advent of offshore markets in the second half of 1950s was also due to developments in Italy, rather than only in Britain as claimed in the literature. Both countries were members of the EPU and both reestablished currency convertibility within the EPU area, Italy in 1956, Britain the previous year. The liberalization of foreign exchange markets within the EPU area represented a major step toward the reestablishment of foreign-currency convertibility, which was achieved at the end of 1958. By then, the size of the Eurocurrency market was already significant and set to grow even more the following year, when its approximate size represented close to half of the U.S. balance of payments deficit. Such a large volume of offshore transactions highlight that Bretton Woods was already not as restrictive in the 1950s as might be expected, given the widespread use of capital controls.

The Italian foreign-currency credit market was as competitive as the Eurodollar market. Nonresident foreign-currency deposits were not subject to reserve requirements. Access to these funds therefore enabled Italian banks to offer loans at interest rates below rates offered for loans in lire. The interest rate asymmetry was the result, on the one hand, of stringent monetary policy and collusive behavior between the banks in the lira loan market after 1954, and on the other hand, of the competitive behavior that prevailed in the foreign-currency market until September 1960. The logic of capital controls was to drive a wedge between domestic and foreign interest rates so that any existing asymmetry between these two sets of interest rates would not undermine domestic monetary policy autonomy. In Italy, the inflow of foreign funds (Eurodollar deposits) was only temporarily obstructed by the Bank of Italy. Rather than take the view that short-term capital inflows could disrupt monetary policy, the Bank of Italy encouraged such inflows on the grounds that they increased the competitiveness of the Italian economy, which was undergoing economic change and industrial modernization in a context of gradual internationalization. The demand by Italian banks for offshore foreign-currency deposits led to the gradual demise of foreign credit lines as funding sources. Italy therefore pioneered a method of financing foreign trade that other countries adopted in the 1960s. That method established a direct link between offshore banking and foreign trade finance in the 1950s.

The large Eurocurrency and Eurodollar deposit holdings of Italian banks in the second half of the 1950s also recalibrate the view that the City of London was the leading offshore financial center from the outset. Gary Burn places great emphasis on the pioneering role BOLSA played in the development of the Eurodollar market and is rather critical of American banks, which in his view came to the Eurodollar market rather late, in 1959.Footnote 128 Be that as it may, it was borrowing by branches of American banks that explains the City’s rise as the leading Eurodollar international financial center.

The joint forces of Italian, French, British, American, and other foreign banks operating from the City of London coalesced to develop offshore finance in the 1950s. The case study of Italian banks, but also the sectoral analysis of Eurodollar lending in the City of London in 1958 and 1959, strongly suggests that the rapid rise of postwar offshore banking related primarily to demand from the domestic clients of Italian and British banks and from head offices of American banks. From the standpoint of British and Italian borrowers, the attractiveness of the Eurodollar market came from the low interest rates on loans it offered relative to the domestic market. Head offices of American banks, on the other hand, tapped the emerging Eurodollar liquidity pool to evade New Deal regulations. Foreign borrowers also came to the Eurodollar market because of the attractive loans British merchant and overseas banks offered. Eurocurrency banking enabled these banks to engage in external intermediation and thus evade the capital controls of late 1957.

Although the Eurodollar market was the brainchild of bankers, central banks in Italy and Britain were part of the Eurodollar origin story. They helped Eurocurrency banking to gain steam in order to finance Italian foreign trade more efficiently and to revive London as international financial centers.

The Eurodollar market developed at a time of strong economic growth in Western Europe and of renewed hope for the future after the hardship of the Great Depression and World War II. The history of the rise of postwar offshore finance, therefore, represents an essential aspect of the Golden Age of Capitalism.

Acknowledgments

The author expresses warm thanks to the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments.

Appendix The Measurement of Nonresident Foreign-Currency Deposits

The annual reports of the Bank of Italy measured each year the level of foreign indebtedness in foreign currencies of Italian banks. These funds were calculated between 1950 and 1953 as “Eximbank” (i.e., the loans granted to Italy by the Export-Import Bank of the United States) and “foreign banks” (banche estere) and between 1954 and 1959 as “foreign financing” (finanziamenti esteri; i.e., the foreign funds borrowed abroad by the specialized credit institutions, foreign credit lines, and since 1956, nonresident foreign-currency deposits). The foreign-currency funds the banks borrowed abroad were calculated as part of the of the “ancillary funds” (mezzi di provvista sussidiari) of the specialized credit institutions and the commercial banks.

The Bank of Italy published in its annual reports the size of the foreign-currency funds borrowed abroad by the specialized credit institutions,Footnote 129 those of the foreign credit lines of the commercial banks between 1950 and 1953, their yearly variations in 1955, 1956, and 1959 and their size in 1957 and 1958, while, as mentioned, it did not publish the size of nonresident foreign-currency deposits (Eurodollars and Eurocurrencies). Therefore, nonresident foreign-currency deposits cannot be measured between 1950 and 1954.Footnote 130

The size of nonresident foreign-currency deposits for 1955–1959 have been calculated by subtracting from the total “foreign financing” funds the size of foreign-currency funds of the specialized credit institutions and foreign credit lines. The resulting difference represents nonresident foreign-currency deposits. The sums have been converted from lire to dollars at the Bretton Woods rate of $1 = ₤625.