Multi-stakeholder initiatives (MSIs) have become a central governance mechanism of corporate social responsibility (CSR) (de Bakker, Rasche, & Ponte, Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019; Jellema, Werner, Rasche, & Cornelissen, Reference Jellema, Werner, Rasche and Cornelissen2022). Typically established to fill gaps in the regulation of social and environmental issues, MSIs are governance institutions in which corporations engage in dialogue and self-regulation with a variety of stakeholders, including civil society organisations, trade unions, and governments (Arenas, Albareda, & Goodman, Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020; Gilbert & Rasche, Reference Gilbert and Rasche2008; Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012; Rasche, Reference Rasche2012). Prominent examples of MSIs include the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC) and the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), as well as the illustrative case in our study: the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety (hereinafter the Accord).

Along with the proliferation of MSIs in recent decades, a growing body of interdisciplinary research has emerged aimed at addressing key issues arising from their operation (Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020; de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019; Locke, Reference Locke2013; Pope & Lim, Reference Pope and Lim2020). In particular, the legitimacy of MSIs as private institutions of transnational governance has attracted considerable scholarly attention (Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020; Bäckstrand, Reference Bäckstrand2006; de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019; Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2010; Bernstein & Cashore, Reference Bernstein and Cashore2007; Black, Reference Black2008; Haack & Rasche, Reference Haack and Rasche2021; Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012; Scherer & Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2011). Legitimacy has long been a central but highly contested construct not only in the political sciences (Habermas, Reference Habermas1996; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf2009) but also in organisation and management theory (Suchman, Reference Suchman1995; Suddaby, Bitektine, & Haack, Reference Suddaby, Bitektine and Haack2017). This scholarship has generally been concerned either with the social acceptance of institutions and organisations or with the procedural aspects related to the normative acceptability of social order (Suchman, Reference Suchman1995). In the context of MSIs, research focused on legitimacy has often drawn on deliberative democracy theory to analyse the conditions under which a transfer of regulatory power from nation-states to MSIs can attain normative legitimacy (Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020; Hahn & Weidtmann, Reference Hahn and Weidtmann2016; Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012; Scherer & Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2007).

In the political sciences, the literature on deliberative democracy has taken a “systemic” turn in recent years, reflecting “an understanding of deliberation as a communicative activity that occurs in multiple, diverse yet partly overlapping spaces, and emphasizes the need for interconnection between these spaces” (Elstub, Ercan, & Mendonça, Reference Elstub, Ercan and Mendonça2016: 139). By contrast, studies on the legitimacy of MSIs in the field of business ethics have so far been focused mostly on the internal characteristics of these initiatives and the interactions of MSIs with selected actors (Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020; Gilbert & Rasche, Reference Gilbert and Rasche2008; Gilbert, Rasche, Schormair, & Singer, Reference Gilbert, Rasche, Schormair and Singer2023; Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012; Pek, Mena, & Lyons, Reference Pek, Mena and Lyons2023). In this article, we draw on insights from both these fields to advocate the adoption of a systemic perspective in research on MSI legitimacy, including in business ethics studies. In making this case, we draw especially on studies that have analysed the relationships of MSIs with other actors (Fransen, Reference Fransen2012; Levy, Reinecke, & Manning, Reference Levy, Reinecke and Manning2016; Reinecke, Manning, & von Hagen, Reference Reinecke, Manning and von Hagen2012), as well as with international regulatory standards (for an overview, see Gilbert, Rasche, & Waddock, Reference Gilbert, Rasche and Waddock2011), governments (Knudsen & Moon, Reference Knudsen and Moon2017), and market intermediaries (Soundararajan, Khan, & Tarba, Reference Soundararajan, Khan and Tarba2018). Applying a systemic perspective can greatly assist researchers in exploring the ways MSIs engage with their environments, affording a theoretical framework and normative criteria with which to analyse the constituent and co-constitutive role of MSIs as parts of broader systems. From a systemic perspective, we can assess whether the larger deliberative systems of which MSIs form a part would be better off with or without these initiatives.

Given that deliberative democratic theory is “ultimately concerned with the democratic process as a whole, and therefore with the relationships of its parts to the whole” (Mansbridge et al., Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 26), analysing governance systems such as MSIs further entails adopting a “two-tier approach to evaluation” (Mansbridge et al., Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 13), i.e., an approach that assesses systems both as a whole and in terms of their individual parts, aligning with Sabadoz and Singer (Reference Sabadoz and Singer2017: 203–5). As systems within systems, MSIs and their environments mutually interact and co-constitute one another. In this article, therefore, we apply a two-tier approach to answer the following research question: How do MSIs support or undermine the deliberative capacity of overall governance systems?

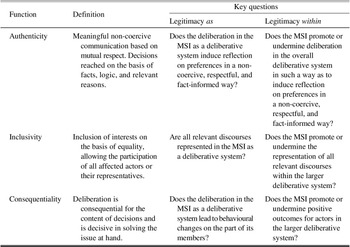

Addressing this question affords novel insights into the complex nature of legitimacy issues vis-à-vis MSIs. In particular, the normative framework we develop to evaluate the deliberative legitimacy of MSIs (Figure 1) helps reveal cases in which there are significant disparities between the legitimacy of a MSI as a system in itself and the extent to which that MSI contributes to or detracts from the legitimacy of a broader system of governance. This imbalance can work both ways. On one hand, a MSI as a deliberative system in its own right can “have low or even negative deliberative quality with respect to one or several deliberative ideals” (Mansbridge et al., Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 3) and yet nonetheless serve to broaden the deliberative legitimacy of the wider governance system within which it operates (Chambers, Reference Chambers2004). We illustrate this type of imbalance in this article by reference to the case of the Accord. On the other hand, some MSIs may have a high degree of deliberative legitimacy in themselves yet still have the effect of undermining the overall legitimacy of collaborative governance at the systemic level, including by crowding out other potentially more effective institutions. We refer to these two types as case i and case ii (again following Sabadoz & Singer, Reference Sabadoz and Singer2017), exploring these contrasting cases to demonstrate that not every part of a system needs to fulfil all the functions of deliberative legitimacy to make a valuable contribution to the broader system. On the basis of our analysis of these two cases, we develop a nuanced framework with normative criteria for assessing the contribution of MSIs to overall deliberative systems. These proposed criteria relate to the underlying functions of deliberative democracy as first elaborated by Dryzek (Reference Dryzek2010) and now established in deliberative systems theory, that is, the functions of authenticity, inclusivity, and consequentiality, which we apply to the context of MSIs.

Figure 1: Framework for Assessing the Legitimacy of MSIs from a Deliberative Systems Perspective

By elucidating these three functions as normative criteria for assessing the contribution of MSIs as deliberative systems to larger governance systems, we make one overarching theoretical contribution. Our application of a systems perspective to MSIs advances the ongoing debate on the legitimacy of multi-stakeholder governance (Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020; Bäckstrand, Reference Bäckstrand2006; Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012; Soundararajan, Brown, & Wicks, Reference Soundararajan, Brown and Wicks2019). We derive a comprehensive framework and argue that MSIs need to be evaluated from a systems perspective focusing on the analysis of their capacity to enhance or undermine the deliberative legitimacy of the larger governance systems in which they operate. Adopting this perspective further entails accepting that genuine democratic involvement in deliberation at every stage of a decision-making process is a worthwhile but ultimately impossible ideal for MSIs. As we show in our analysis of the Accord, not every institutional element of a MSI needs to be deliberative for the governance system as a whole to achieve legitimacy. On the basis of our theoretical contribution, we also derive two practical implications. Firstly, we show that our framework can meaningfully inform the design of new MSIs. Secondly, our framework can be used to better understand why existing MSIs may fail to exert a positive influence on the legitimacy of the wider governance systems in which they operate.

MULTI-STAKEHOLDER INITIATIVES AND THEIR DELIBERATIVE LEGITIMACY

In the absence of effective “hard law” regulations to address global environmental and social issues (Bartley, Reference Bartley2007), combined with the increasing influence of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) on corporations, MSIs have emerged as key institutions to fill critical gaps in the governance of transnational corporate conduct, especially in the contexts of complex global supply chains (Hennchen & Schrempf-Stirling, Reference Hennchen and Schrempf-Stirling2021; Levy et al., Reference Levy, Reinecke and Manning2016; Soundararajan et al., Reference Soundararajan, Brown and Wicks2019). Although all MSIs share the characteristic of being a private form of governance, they vary significantly both in the composition of their actors and in the scope of regulation they produce (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Rasche and Waddock2011). An important difference between MSIs and other forms of private regulation, such as business-driven initiatives and codes of conduct, is that these latter forms typically include little or no stakeholder representation (de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019).

With the proliferation of MSIs, an expanding body of scholarship within and across disciplines has emerged, including in the fields of political science, sociology, law, and business ethics (Utting, Reference Utting, Mukherjee Reed, Reed and Utting2012). Scholars have analysed MSIs in terms of their impacts and outcomes (de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019; Barrientos & Smith, Reference Barrientos and Smith2007; Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Rasche and Waddock2011; Jellema et al., Reference Jellema, Werner, Rasche and Cornelissen2022; Locke, Reference Locke2013; Soundararajan et al., Reference Soundararajan, Brown and Wicks2019), complementarities and overlaps (Turcotte, Reinecke, & den Hond, Reference Turcotte, Reinecke and den Hond2014), accountability (Hennchen & Schrempf-Stirling, Reference Hennchen and Schrempf-Stirling2021; Hussain & Moriarty, Reference Hussain and Moriarty2018), and institutionalisation (de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019; Ponte, Reference Ponte2019). As de Bakker et al. (Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019) has shown in a cross-disciplinary review of research on MSIs, however, most research to date has focused on single cases, analysing the interactions of MSIs with selected actors rather than the wider systems of which these initiatives form a part.

Given that MSIs are private initiatives addressing gaps in legal governance, the question of their legitimacy has inevitably emerged as a central and highly contested issue in the literature on these initiatives (Arnold, Reference Arnold2013; Banerjee, Reference Banerjee2010; Haack & Rasche, Reference Haack and Rasche2021). In this debate, many scholars have proposed that organisational legitimacy constitutes a key precondition for the effectiveness of any self-regulation produced by MSIs, with such legitimacy being defined as “a generalized perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (Suchman, Reference Suchman1995: 574). Within this scholarship, deliberative democracy theory has been especially influential (Hahn & Weidtmann, Reference Hahn and Weidtmann2016; Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012; Scherer & Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2007) as a lens through which to examine the legitimacy of MSIs as spaces of contestation and deliberation (Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020). In their political conceptualisation of CSR, for example, Scherer and Palazzo (Reference Scherer and Palazzo2007) have drawn on Habermasian deliberative democracy in arguing that MSIs are prime examples of how corporations, together with NGOs, can lead to effective consensus on legitimate forms of industry self-regulation.

Although research on the deliberative legitimacy of MSIs has advanced greatly in recent years within the literature on business ethics (Arenas et al., Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020; Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2021; Huber & Schormair, Reference Huber and Schormair2021), this scholarship has yet to take the “systemic turn” as evident in the broader literature on deliberative democracy in the field of political science. As a consequence, the literature on deliberative legitimacy and MSIs still lacks a distinctive approach that takes full account of the interrelationships among MSIs and other actors in overall governance systems. And while adopting a deliberative systems perspective is not without precedent in the business ethics literature, with examples including studies by Sabadoz and Singer (Reference Sabadoz and Singer2017) and Felicetti (Reference Felicetti2018) on the deliberative capacity of firms, most prior research specifically focused on MSIs has not applied this perspective. For example, Arenas et al. (Reference Arenas, Albareda and Goodman2020) have focused on theorising the effects of internal contestation on the quality of deliberative democracy within MSIs. Similarly, in exploring how MSIs are held accountable, Hennchen and Schrempf-Stirling (Reference Hennchen and Schrempf-Stirling2021) have confined their investigation to criteria for assessing the internal accountability of MSIs, while Dawkins (Reference Dawkins2021) has applied an agonistic concept of political CSR to enhance our understanding of the internal processes of MSIs. We acknowledge and build on the valuable insights these studies have yielded to MSI legitimacy while at the same time emphasising that MSIs never exist in a vacuum but are influenced by and exert influence on multiple actors beyond those within the internal boundaries of any single initiative (Bernstein, Reference Bernstein2011). In this study, therefore, we start from the premise that it is the combined interactions of all these actors and institutions that constitute complex systems of governance on any given issue.

As a recent exception, Pek et al. (Reference Pek, Mena and Lyons2023) have applied the deliberative systems perspective to MSIs. They analyse how applying the concept of mini-publics from the deliberative systems literature to MSIs can improve their deliberative capacity. They find that mini-publics, which are “forums in which a randomly selected group of individuals from a particular population engage in learning and facilitated deliberations about a topic” (Pek et al., Reference Pek, Mena and Lyons2023: 102), can, under given circumstances, improve democratic representation and inclusiveness of stakeholders within MSIs.

Following their lead in applying a systems perspective and developing a normative framework to evaluate the functions and roles of MSIs within broader systems of governance, our study directly responds to calls in the literature for scholars to explore and take account of the complexity and multiplicity of actors in evaluating the legitimacy of MSIs (de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019; Jellema et al., Reference Jellema, Werner, Rasche and Cornelissen2022). In this context, we go beyond Pek et al. (Reference Pek, Mena and Lyons2023), who apply the systems perspective to improve internal stakeholder representation within MSIs, and respond to their, as well as de Bakker et al.’s (Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019), call for future research to address the implications of viewing “MSIs as but one part of a broader deliberative system of transnational governance” (Pek et al., Reference Pek, Mena and Lyons2023: 134).

In this endeavour, we can draw on a limited number of studies that have analysed the relationships of MSIs with other actors, including research by Fransen (Reference Fransen2012), Levy et al. (Reference Levy, Reinecke and Manning2016), and Reinecke et al. (Reference Reinecke, Manning and von Hagen2012). Consistent with our premise that MSIs never operate in isolation, these studies have shown that MSIs can trigger the creation of competing MSIs in what Reinecke et al. have identified as an emergent “standards market,” with multiple MSIs now jointly interacting in ways that shape and redefine the very issues being governed (Fransen, Reference Fransen2012; Levy et al., Reference Levy, Reinecke and Manning2016). We can also draw on insights from Knudsen and Moon’s (Reference Knudsen and Moon2017) work on the relationship between governments and MSIs and their analysis of how MSIs operate in the shadow of governments, with states shaping CSR initiatives and government policies supporting MSIs (and vice versa), including as a means for states to avoid regulating certain issues directly through binding legislation.

Our starting point, therefore, is that any systemic evaluation and corresponding assessment criteria of MSI legitimacy must account for the mutual interaction and influence of MSIs with other systems around them, that is, the ways in which MSIs interact with other initiatives and regulatory institutions to co-constitute complex governance systems. Accordingly, we build our analysis here on the criteria of legitimacy established by John Dryzek (Reference Dryzek2010), one of the founders of deliberative systems theory, referring to his functions of authenticity, inclusivity, and consequentiality. Dryzek’s work has evolved in parallel with Scharpf’s (Reference Scharpf1997, Reference Scharpf1999, Reference Scharpf2009) theorising of legitimacy in political science, whose criteria have been commonly applied in business ethics (see, e.g., Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012). Scharpf and Dryzek build on each other’s insights (Dryzek, Bächtiger, & Milewicz, Reference Dryzek, Bächtiger and Milewicz2011: 39; Scharpf, Reference Scharpf1998: 3; Reference Scharpf2009: 188; Reference Scharpf2012: 10). Whereas Scharpf (Reference Scharpf1997, Reference Scharpf1999, Reference Scharpf2009) has focused primarily on the political legitimacy of institutions that can be perceived and evaluated as legitimate in themselves (“input legitimacy”) and/or as producing legitimate outcomes (“output legitimacy”), Dryzek (Reference Dryzek2010) has developed a more intricate approach to the deliberative legitimacy of institutions in the context of global governance, conceptualising institutions as deliberative systems embedded within and interconnected with other systems. The different criteria of legitimacy elaborated by these scholars are nonetheless closely related. Indeed, according to Dryzek et al. (Reference Dryzek, Bächtiger and Milewicz2011: 39), any deliberative process fulfilling the aforementioned functions of deliberative legitimacy would contribute equally substantially to what Scharpf (Reference Scharpf1997) terms output and input legitimacy “inasmuch as it would promote goals that a body of citizens value” (output) and “in that it would involve a pioneering avenue for representative citizens of the world to have a say in global governance” (input). Although prior research on business ethics has more often applied Scharpf’s criteria (Mena & Palazzo, Reference Mena and Palazzo2012; Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2022), we opt for Dryzek’s (Reference Dryzek2010) criteria as being better suited to conceptualising legitimacy in the context of MSIs as deliberative systems. Notably, although Dryzek formulated his deliberative systems approach to conceptualise legitimacy in the context of global governance, his work has only in passing addressed MSIs in deliberative systems. We argue that applying his approach to the context of MSIs yields valuable insights.

DELIBERATIVE DEMOCRACY AND THE TURN TOWARDS DELIBERATIVE SYSTEMS

Foundations of Deliberative Democracy

As a theory of democratic legitimacy, deliberative democracy holds that the “legitimacy of collective arrangements … rests on mutual justification through deliberative practices among free and equal citizens” (Erman, Reference Erman2016: 265). Unlike aggregative accounts of democracy focused on how collective decisions are arrived at merely by aggregating preferences, deliberative democracy theory is concerned with how individuals arrive at their preferences and how these can potentially be transformed through “informed, respectful, and competent dialogue” (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2010: 3).

According to Mansbridge et al. (Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 25), in the early phase of deliberative theory, an ideal proceduralism “of political justification requiring free public reasoning of equal citizens” was initially established as the “regulative” ideal for deliberative democracy, most influentially by Habermas (Reference Habermas1996), though also by Cohen (Reference Cohen, Hamlin and Pettit1989) and Gutmann and Thompson (Reference Gutmann and Thompson2004). In applying this theory, however, scholars faced the problem that giving equal access to all those affected by a decision to participate in deliberation is simply not feasible in real-world processes of decision-making (Gutmann & Thompson, Reference Gutmann and Thompson1996; Holst & Moe, Reference Holst and Moe2021). Indeed, it was this difficulty that prompted what Dryzek (Reference Dryzek2010: 7) has coined the “systemic turn” in deliberative democracy, with scholars now turning their focus to “whole systems, of which any single deliberative forum is just a part.” An important corollary of this conceptualisation is that deliberative processes cannot be studied in isolation but must be examined in relation to their systemic contexts (Parkinson, de Laile, & Franco-Guillen, Reference Parkinson, de Laile and Franco-Guillen2022). Whereas deliberative democracy theory at the outset was tied to liberal democracies, in recent years, deliberative theory has in particular been drawn on to theorise how a deliberative approach can help global governance institutions address democratic deficits (Dryzek, Bowman, Kuyper, Pickering, Sass, & Stevenson, Reference Dryzek, Bowman, Kuyper, Pickering, Sass and Stevenson2019; Habermas, Reference Habermas2022).

Deliberative Systems: Deliberative Democracy on a Large Scale

The turn towards deliberative systems has shifted the focus in assessments of deliberative legitimacy from “the extent to which particular types of institutions do or do not meet standards of deliberative democracy” to the analysis of how individual institutions can be combined in such a way as “to ensure that the norms of deliberative democracy are prevalent across the deliberative system as a whole” (Elstub & McLaverty, Reference Elstub, McLaverty, Elstub and McLaverty2014: 190). According to Mansbridge et al. (Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 4–5), deliberative systems are characterised by a talk-based approach to political conflicts on issues of common concern. The different parts of these systems include both “formal” parts, such as state institutions or official fora, and “informal” parts, such as civil society initiatives (Mansbridge et al., Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 12). As Elstub and McLaverty (Reference Elstub, McLaverty, Elstub and McLaverty2014: 190) noted, “it is then the interconnected nature, interdependence and division of labour between these parts, that become key to systemic analysis.” From this perspective, it is not necessary for every single part to be deliberative but only that their combined impact serves to strengthen the overall system as democratic (Elstub & McLaverty, Reference Elstub, McLaverty, Elstub and McLaverty2014).

As to the factors that make systems deliberatively democratic, theorists have offered a variety of contrasting accounts (Holst & Moe, Reference Holst and Moe2021; Maia, Hauber, Choucair, & Crepdale, Reference Maia, Hauber, Choucair and Crepdale2021; Mansbridge et al., Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012). In this article, for reasons cited earlier, we base our criteria on Dryzek’s (Reference Dryzek2010: 10) three normative functions of authenticity, inclusivity, and consequentiality. Dryzek highlights these functions as criteria to assess the deliberative capacity of a system, along with a set of items that can be used to describe deliberative systems. Because, in this article, we are interested primarily in a normative evaluation of the legitimacy of MSIs in a deliberative democratic sense, in our analysis, we focus not on the descriptive elements of Dryzek’s approach but on these three underlying functions, which are introduced in more detail subsequently. We apply the functions in a “two-tier approach to evaluation” (Mansbridge et al., Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 13) that acknowledges the interconnected nature of sites, actors, and institutions in systems. Though Dryzek’s (Reference Dryzek2010) primary concern, and thus level of analysis, is whether and how systems of governance as a whole possess deliberative capacity, from this interconnectedness, it follows that the same set of criteria must be applied to both the inner system and the outer system to ascertain whether the external environment compensates for shortfalls on the part of the MSI as a deliberative system (or vice versa) (Mansbridge et al., Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012) and thus whether the overall deliberative system is better off with or without the MSI in question.

DEVELOPING A DELIBERATIVE SYSTEMS PERSPECTIVE ON MSIS

A deliberative systems perspective on MSIs affords researchers a theoretical framework for analysing whether and to what extent the legitimacy of a particular MSI serves to enhance or undermine the deliberative capacity and legitimacy of the overall system of which it forms a part. In proposing this distinction between the legitimacy of a MSI as a deliberative system and within a deliberative system, our approach aligns with the argument Haack and Rasche (Reference Haack and Rasche2021) advanced that legitimacy in MSIs invariably comprises different forms of legitimacy that coexist and evolve in complex ways. Applying this distinction reflects and highlights the importance of boundaries and their deliberation for MSIs. Thus we propose three steps for evaluating the legitimacy of a MSI from a deliberative systems perspective: 1) identify the boundaries of the deliberative system, 2) evaluate the legitimacy of the MSI as a system, and 3) assess the legitimacy of the MSI within an overall system.

The Boundaries of Deliberative Systems

When considering and evaluating the deliberative legitimacy of a MSI as a deliberative system in itself, we define its internal boundaries as comprising all those actors who consider and publicly declare themselves part of that institution (Sabadoz & Singer, Reference Sabadoz and Singer2017). Defining the external boundaries of MSIs when considered as systems within overall deliberative systems is far less straightforward. Most comprehensively, these external boundaries can be defined “by reference to a particular issue” (Mansbridge et al., Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 8), thereby encompassing the heterogeneous constituency of all actors affected by that issue, including all those engaged in communicative exchanges with members of MSIs involved in the governance of that particular issue. Reflecting the complexity of the challenges they are set up to address, the overall deliberative governance systems in which MSIs operate vary greatly in scope and scale, ranging from systems governing local issues in which a limited local public constitutes the external boundary to transnational issues affecting and engaging multiple publics. The complexity of this notion of an overall deliberative system is well captured in an analogy Mansbridge et al. (Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 10) draws, in which they suggest “a map of nodes in the deliberative system.” In short, these external boundaries are open to interpretation, depending on how a “particular issue” is defined (Mansbridge et al., Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012). Within any particular supply chain, industry, or topic, these boundaries can be defined either at a transnational level or close up, “at the coalface” (Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2021a). Researchers should thus give this definition careful consideration. For, whereas narrower demarcations of external system boundaries have the advantage of making empirical analysis more manageable, the external systemic aspects of a MSI will ultimately be rendered more or less visible, depending on the scope of this definition.

Because MSIs usually emerge in global governance voids, governments are often external to MSIs yet nonetheless play an important role in their effectiveness through their responses to such initiatives. And because governance voids proliferate through globalisation, the boundaries of the external systems of MSIs can often extend to the global scale (Scherer, Palazzo, & Seidl, Reference Scherer, Palazzo and Seidl2013). Given the vast expansion in the number of MSIs addressing corporate conduct over recent years (Jellema et al., Reference Jellema, Werner, Rasche and Cornelissen2022), different MSIs often deal with similar issues and hence also interact in particular ways as parts of the same systems (de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019). In evaluating each case, therefore, what needs to be established is the extent to which a MSI contributes to upholding or undermining the functions of the deliberative system overall through its interactions with other nodes in that system.

The Legitimacy of MSIs as Deliberative Systems

Evaluating the legitimacy of a MSI as a deliberative system involves assessing how it performs in terms of the functions of deliberative democracy within its internal boundaries, that is, the extent to which the authentic, inclusive, and consequential functions, which are the three dimensions “to assess the completeness and effectiveness of actual and potential deliberative systems” Dryzek (Reference Dryzek2010: 10) introduced, can be considered as having been realised among the internal members of the MSI.

According to Dryzek (Reference Dryzek2010), the authentic function of a deliberative system refers to its capacity of enabling the members participating in that system to reflect on preferences in a non-coercive manner. This function resonates largely with Mena and Palazzo’s (Reference Mena and Palazzo2012) input legitimacy of MSIs. It entails that communications be meaningful, understandable, and acceptable for all parties, including for those who do not agree with the argument (Gutmann & Thompson, Reference Gutmann and Thompson2004). As part of this function, mutual respect is vital in ensuring that individuals are treated as autonomous agents, that is, as subjects actively taking part in governance and not merely as objects of regulation (Gutmann & Thompson, Reference Gutmann and Thompson2004). For a MSI’s internal deliberative system to be considered legitimate in terms of authenticity, therefore, it must facilitate substantive consideration of relevant reasons and a relative balance of power between competing interests (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2010: 10).

The inclusive function of a deliberative system relates to “the opportunity and ability of all affected actors (or their representatives) to participate” (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2010: 10), which again shows similarities to Mena and Palazzo’s (Reference Mena and Palazzo2012) input legitimacy of MSIs. As such, a deliberative system should “promote an inclusive political process on terms of equality” (Mansbridge et al., Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 12), meaning that for an organisation’s internal democratic system to be adjudged functional and legitimate, it must actively promote inclusion and only exclude actors with justifications “that could be reasonably accepted by all … including the excluded [since] for those excluded, no deliberative democratic legitimacy is generated.” When it comes to setting criteria for inclusiveness, therefore, Dryzek (Reference Dryzek2010: 30) has advocated “letting go of the idea that legitimacy must be based on a head count” and instead applying the concepts of “discursive representation” and “discursive legitimacy” in evaluating a system’s inclusive function, with these discursive qualities being understood in the sense of discourse “as a shared way of comprehending the world embedded in language.” What matters for the quality of deliberation is thus not that as many individuals as possible are represented but that “all relevant discourses get represented” (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2010: 44). Ensuring the representation of discourses is thus one way to resolve the “scale problem” in cases in which it is not feasible for a decision-making process to include all those affected by that decision. Applied to MSIs as internal deliberative systems, this means that all discourses relevant to the issue governed by the initiative need to be represented by members of the MSI.

The consequential function of a deliberative system relates both to the actual behavioural changes of its members and to the normative claim that deliberations within a system must be “consequential in the sense of influencing the content of collective decisions” (Erman, Reference Erman2016: 267). It thus resonates with Mena and Palazzo’s (Reference Mena and Palazzo2012) output legitimacy of MSIs. Consequential deliberation must hence be decisive in effectively addressing the particular issue of common concern at hand; that is, it must “somehow make a difference when it comes to determining or influencing collective outcomes” (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2010: 11). For a MSI as a deliberative system to be considered internally consequential, therefore, it needs to produce rules, norms, and regulations that have tangible impact on its members’ conduct of business in ways that address the issue of concern, for example, by improving working conditions. By this criterion, there are differences in the consequentiality and hence legitimacy of different types of MSI, that is, between those that build primarily on ambitions (e.g., the UNGC), those that produce certification standards (e.g., SA 8000), and those that include legally binding regulations (e.g., the Accord) (Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Rasche and Waddock2011; Gilbert & Rasche, Reference Gilbert and Rasche2007; Jellema et al., Reference Jellema, Werner, Rasche and Cornelissen2022).

The Legitimacy of MSIs within Deliberative Systems

Assessing the legitimacy of a MSI vis-à-vis its role within a deliberative system essentially involves appraising the extent to which the MSI promotes or undermines the three functions of deliberative democracy of the system as a whole. This comprehensive account of the whole deliberative system of governance, in our view, represents Dryzek’s (Reference Dryzek2010) level of analysis. Combining his perspective with the two-tier approach as suggested by Mansbridge et al. (Reference Mansbridge, Bohman, Chambers, Christiano, Fung, Parkinson, Thompson, Warren, Parkinson and Mansbridge2012: 13) enables us to apply Dryzek’s (Reference Dryzek2010) functions to both the internal deliberative system (MSI as a system; see the preceding section) and the external deliberative system of MSIs (MSI within a system; see this section).

Analysing a MSI within a system entails evaluating how other parts of the overall system interact with the MSI and addressing how these interactions affect the functions of deliberative democracy to determine whether the overall system would be better off with or without that MSI. Given the complex, dynamic, and contingent interplay among the multiple discrete deliberative parts of any such system, evaluating the overall effect of a MSI as an individual deliberative institution on the particular system within which it operates is inevitably a daunting task. Indeed, theorists have only recently set about devising ways of empirically assessing institutions from a deliberate systems perspective (e.g., Dryzek et al., Reference Dryzek, Bächtiger, Chambers, Cohen, Druckman, Felicetti, Fishkin, Farrell, Fung, Gutmann, Landemore, Mansbridge, Marien, Neblo, Niemeyer, Setälä, Slothuus, Suiter, Thompson and Warren2019; Engelken-Jorge, Reference Engelken-Jorge2017; Holst & Moe, Reference Holst and Moe2021; Maia et al., Reference Maia, Hauber, Choucair and Crepdale2021; Niemeyer, Reference Niemeyer2016). In what follows, we provide detailed guidance on how to conduct such analysis, again applying Dryzek’s (Reference Dryzek2010) three functions of a legitimate deliberative system.

Firstly, in evaluating the extent to which a MSI promotes or undermines the overall deliberative system of which it is part, we need to consider how the initiative impacts the authenticity of discourse in that system (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2010). For example, a MSI that hosts and fosters meaningful, understandable, respectable, and respectful communication for all its internal parties but does not do the same when communicating with external actors could not be considered as contributing to the overall authenticity of a deliberative system. This can happen because of a lack of transparency, for example, if the internal documents of MSIs are not accessible or not understandable to the public.

Secondly, we need to consider whether a MSI promotes or undermines the inclusiveness of the deliberative system as a whole (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2010). Here it is important to bear in mind that although a particular initiative may provide a fairly inclusive and open forum for different actors to assert and debate their positions internally, this same forum can also have the effect of crowding out alternative and more radical undertakings, for example, street protests that could be valuable for highlighting a particular issue or interest and for effectively inducing changes in public debate. On the other hand, a MSI that seems defective in terms of inclusivity when judged as a system in itself may nonetheless serve to compensate for deficiencies in other parts of the wider system and thus promote and enhance deliberation overall, for example, by sharpening a public debate.

Thirdly, considering the consequential function of a MSI within a wider deliberative system entails taking account of whether the initiative serves to promote or undermine the outcomes of the external deliberative system (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2010). Such outcomes may include changes in formal legislation, public policy decisions, or treaties, as well as more informal measures of change (Dryzek, Reference Dryzek2010). As Dryzek noted, private governance initiatives often fail because of the lack of consequentiality of certain parts of their overall deliberative systems.

Table 1 provides a summary of the normative functions of MSIs as and within deliberative systems.

Table 1: Three Normative Functions of MSIs as and within Deliberative Systems

Note. MSI = multi-stakeholder initiative. Based on Dryzek (Reference Dryzek2010).

Towards a Framework for Assessing the Legitimacy of MSIs in the Context of Deliberative Systems

On the basis of our central distinction between the legitimacy of MSIs as and within deliberative systems, we derive a framework comprising four possible configurations of MSIs (including the aforementioned cases i and ii). The four possible “cases” depicted in the framework in Figure 1 result from assessing MSIs along the different dimensions of their legitimacy as deliberative systems and their legitimacy within wider deliberative systems. Given the growing multiplicity of MSIs (de Bakker et al., Reference de Bakker, Rasche and Ponte2019; Gilbert et al., Reference Gilbert, Rasche and Waddock2011; Jellema et al., Reference Jellema, Werner, Rasche and Cornelissen2022), when applying our framework to practical examples of MSIs, it is important to understand the proposed scales between low and high legitimacy not as “black-and-white” categories, whereby a MSI has either full legitimacy or none, but rather as depicting a continuum (see Figure 1). There are many shades of grey on these scales, and most real-life MSIs will be placed somewhere between the extremes. For this reason, two examples of MSIs of the same category may still differ significantly in set-up and legitimacy.

With our proposed framework, we are better able to undertake a systemic analysis of how a MSI interacts with its contexts and the implications of these interactions for the legitimacy of the overall deliberative system in which it operates. In this way, we can further determine how a particular MSI can be adapted to improve the legitimacy of that overall system.

The top right corner of Figure 1 depicts a situation in which a MSI exhibits a high degree of legitimacy as a system by hosting authentic, inclusive, and consequential deliberations within its organisational boundaries, while at the same time exhibiting a high degree of legitimacy within a larger system, that is, contributing to the legitimacy of the overall deliberative system by promoting that system’s authenticity, inclusiveness, and consequentiality. We term this pattern the deliberative ideal to indicate that in this case, the norms of deliberative democracy are fulfilled both at the level of the MSI as a single deliberative system and within the overall system of governance of which it forms a part. No practical examples of MSIs can be given of this ideal form, however, because meeting all standards of legitimacy both as and within a system is not realistic; similar to the “ideal speech situation” postulated by Habermas (Reference Habermas1996: 322), this is an ideal for which MSIs should strive despite being unlikely or impossible to attain. On this basis, we contend that MSIs applying our framework can analyse their shortcomings regarding legitimacy as systems within systems and use the framework to inform their efforts to approximate more closely the deliberative democratic ideal. In what follows, we elucidate how such analysis can take place by showcasing examples of MSIs falling within the other three categories of the framework and through our discussion of the illustrative case of the Accord.

In the bottom left corner of Figure 1, deliberative silencing represents the opposite of the deliberative ideal, denoting a situation in which a MSI not only exhibits low deliberative legitimacy as a system, for example, because it disregards relevant voices or relies on bargaining instead of deliberative decision-making, but also cannot or does not compensate for these deficiencies at the systemic level. We call this “deliberative silencing” to indicate cases in which deliberation fails to live up to internal or external normative standards and remains indecisive for collective outcomes, thereby silencing fruitful deliberation at the level of the overall system. Although it may seem harsh to label an actual MSI as a case of deliberative silencing, there are indeed examples that have purposefully excluded critical stakeholders, for example, by only including them in advisory roles with no decision-making power. Such exclusion can result from power imbalances and/or from the proclaimed aim of a MSI to ensure efficiency, typically in the case of organisations that label themselves “business initiatives.”

One example of an initiative exhibiting such tendencies is Amfori BSCI. Founded in 2003, this initiative is composed mostly of European apparel brands and retailers and their importers, with major brands like ALDI, Lidl, Tom Tailor, and Tommy Hilfiger. The collective aim of Amfori BSCI members is to reduce the quantity and costs of social audits conducted in the shared factories of their suppliers in developing countries and emerging economies (Knudsen, Reference Knudsen2013). The initiative is governed by a general assembly and a board of directors, the composition of which reflects the diversity of its members, including retailers, importers, brands, and associations from different countries and businesses. Although stakeholders cannot be members of these bodies, there is a stakeholder council that advises. Initially, in its founding years, Amfori BSCI was efficient and effective in combining buyers’ auditing efforts and starting a debate on social conditions in global supply chains. However, it has since become an initiative that makes less and less of a positive contribution to the overall deliberative system, merely creating the illusion of an “easy solution” for regulating sustainability across global supply chains without actually engaging with the critical voices of relevant stakeholders. This MSI thus scores low in terms of its legitimacy as a system, especially regarding the function of inclusivity, because it purposefully excludes stakeholders like NGOs, trade unions, manufacturers, and workers from participation in decision-making. In addition, it also scores low as a system within a system in terms of its contribution to the legitimacy of the overall system, falling short in all three functions of inclusivity, authenticity, and consequentiality. For, though Amfori BSCI does produce internally consequential outcomes in the form of a social auditing code of conduct, this code can hardly be considered consequential as an outcome for the overall deliberative system. There is also evidence that many of Amfori BSCI’s audits may be forged (Schrage & Rasche, Reference Schrage and Rasche2022), especially in Chinese contexts, lulling the buyers among Amfori BSCI’s member firms into a false sense of security while blocking any real changes in the industry. As members of this MSI, “large buyers expect to be ‘off the hook’ if their suppliers are found to be violating basic labor rights” (Knudsen, Reference Knudsen2013: 394), because with the help of Amfori BSCI audits, they can push the responsibility for social sustainability down the chain onto smaller suppliers that do not have sufficient leverage to make changes (Knudsen, Reference Knudsen2013; Schrage & Rasche, Reference Schrage and Rasche2022). Unsurprisingly, there are doubts as to whether the code of conduct–based audits conducted by such business initiatives produce any evidence that truly helps the overall industry to transition to more sustainable production (O’Rourke, Reference O’Rourke2003, Reference O’Rourke2006; Raj-Reichert, Reference Raj-Reichert2013).

In this article, we are especially interested in MSIs that fall into the remaining two quadrants of Figure 1, that is, those whose legitimacy as systems does not align with their legitimacy within systems. This accords with our contention that most practical examples of MSIs will fall into one of these two categories or some grey area in between. Those initiatives that cluster in the bottom right quadrant (described earlier as case i) possess low legitimacy as systems yet still contribute to furthering one or more of the deliberative functions within the overall system of which they form a part. We label this pattern one of deliberative enrichment, because such MSIs ultimately compensate for internal deficiencies by playing a valuable role at the systemic level, whether by including voices that would otherwise go unheard, by bringing expertise to bear on a topic in ways that enhance the authentic legitimacy of societal decisions, or even by contributing to more consequential outcomes, such as legislation at the overall systems level. As one of the two MSIs included as examples of this pattern in Figure 1, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) is a largely business-driven initiative that provides important guidelines for sustainability reporting yet performs poorly according to the criterion of inclusivity as a system insofar as it only takes advice on strategic issues from a stakeholder council (Levy, Szejnwald Brown, & de Jong, Reference Levy, Szejnwald Brown and de Jong2010). Despite falling short on this criterion as a system in itself, however, the expertise of the members of the GRI on the issue at hand, combined with the entrepreneurial skills of its founders (Levy et al., Reference Levy, Szejnwald Brown and de Jong2010), has accumulatively contributed to the production of authentic and consequential outcomes for the larger deliberative system, including ambitious sustainability reports that have had a significant impact on corporate sustainability strategies across industries. The GRI thus constitutes an important voice that has provided substantial input into the larger system surrounding the regulation of reporting on environmental and social issues. As such, the GRI’s contribution to the function of external authenticity can be considered as compensating for its lack of internal inclusivity. In the following section, we focus in more detail on the Accord as another example of deliberative enrichment.

By contrast with MSIs that promote and enrich the legitimacy of wider deliberative systems despite their internal democratic shortcomings, other initiatives undermine the legitimacy of the overall systems of governance in which they operate even while exhibiting a high level of internal deliberative legitimacy. This can happen, for example, when a MSI crowds out other, more deliberative practices. In Figure 1, such types of MSIs (described earlier as case ii) are clustered in the top left quadrant, labelled deliberative detraction. Within this quadrant and category, we include the FSC, a MSI set up for regulating social and ecological standards for sustainable forests. The FSC was founded in 1993, after successive governments had failed to develop joint forest protection standards at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. Pioneering the governance of previously existing MSIs, such as the Marine Stewardship Council, with its three chambers of decision-making representing environmental, social, and economic interests, the FSC has succeeded in developing a set of principles for sustainable global forest management that are respected and adhered to by several multinational corporations, including IKEA, Home Depot, and OBI (Scherer & Palazzo, Reference Scherer and Palazzo2007). However, Dryzek (Reference Dryzek2010) has nonetheless identified the FSC as one of many private governance initiatives that exhibit high levels of internal legitimacy but have not proven to be externally consequential for the overall deliberative systems to which they belong. Commenting specifically on the FSC’s lack of consequentiality, Dryzek noted that this initiative covered only 2 per cent of the world’s commercial forests, while “the forests that are covered are those least in need of regulation” (129), as they are mostly state-run forests in northern Europe. Other forests genuinely in need of regulation, including rainforests, are barely represented in the FSC’s network (Bell & Hindmoor, Reference Bell and Hindmoor2012; Moog, Spicer, & Böhm, Reference Moog, Spicer and Böhm2015). On this basis, Dryzek (Reference Dryzek2010: 130) concluded from his analysis of this MSI that “however deliberative the [FSC] regulatory network, it is not decisive in producing collective outcomes for the world’s forests.” This assessment has since been confirmed in a study by Moog et al. (Reference Moog, Spicer and Böhm2015: 469), showing that the FSC has “failed to transform commercial forestry practices or stem the tide of tropical deforestation” and attributing the impotence of the initiative to “broader [external] market forces and resource imbalances between non-governmental and market actors.” Despite being the most widely accepted standard for sustainable forestry in the Western world and furthering important dialogue between corporations and international social and environmental NGOs, the FSC has not only failed to contribute to the global governance system for forestry but has also arguably had the opportunity cost of crowding out other voices, such as local stakeholders and even member NGOs (Moog et al., Reference Moog, Spicer and Böhm2015). Such “crowding out” includes constraining the capacities of its corporate members to advocate for and adopt more effective alternative measures to address forestry issues. One such alternative measure, for example, would be the “model forest” approach first developed in Canada and since applied in Sweden and Russia. This approach is based on stakeholder collaboration for meeting social and environmental needs in a way that is both targeted at specific geographic areas and adaptive to uncertainty and change. Scholars have advocated the adoption of such model forest initiatives as a promising bottom-up approach based on “collaborative learning by continuous evaluation, communication, and transdisciplinary knowledge production” among local and international stakeholders (Elbakidze, Angelstam, Sandström, & Axelsson, Reference Elbakidze, Angelstam, Sandström and Axelsson2010: 1). Adopting parts of this approach, and above all its bottom-up mode of governance, which gives a voice to local stakeholders and provides adaptability to local circumstances, might be a key way to transform the management of rainforests by building on existing local initiatives in rainforest countries.

Overall, our framework highlights the fundamentally ambivalent character of MSIs, indicating that there is no panacea for the transnational governance of social and environmental concerns. Rather, we argue that the potential of a MSI either to enhance or undermine legitimacy at the larger systemic level depends only partly on the internal deliberative legitimacy of the MSI as a system in itself. To illustrate the value of applying a deliberative systems perspective to the evaluation of MSI legitimacy, we now assess in more depth a MSI that aims to improve working conditions in the garment sector of Bangladesh, that is, the Accord.

A DELIBERATIVE SYSTEMS PERSPECTIVE ON THE BANGLADESH ACCORD ON FIRE AND BUILDING SAFETY

The Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety was an initiative devised in 2013 in response to the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory in Bangladesh, which killed more than eleven hundred garment workers and left more than two thousand injured (Schuessler, Frenkel, & Wright, Reference Schuessler, Frenkel and Wright2019). Initiated through the advocacy work of the Clean Clothes Campaign (CCC), together with other NGOs and global unions (IndustriAll and UNI Global Union), the Accord was signed by more than two hundred fashion brands and retailers and constituted a legally binding agreement between corporations and unions to address the precarious safety conditions in the Bangladeshi ready-made garment (RMG) industry.

Like many MSIs, the Accord had its peculiarities. For example, although it was based on multi-stakeholder collaboration, the Accord was founded as a time-bound collective agreement and was not intended to become a permanent MSI (Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2015). Initially running for five years, from 2013 to 2018, the Accord was extended into a Transition Accord in 2018, before all its operations were transferred to the RMG Sustainability Council in 2020 (Accord on Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh [Accord], 2021). In September 2021, the international brands and trade unions involved agreed on a new International Accord for Health and Safety in the Textile and Garment Industry (hereinafter referred to as the new Accord). Because all these transitions have involved changes to the internal and external governance of the Accord, and because the new Accord’s development is ongoing, our focus in this illustrative case is primarily on the Accord during the early period between 2013 and 2018. This phase is of particular interest for our research purposes as having been characterised by significant shifts and dynamics in power and institutions in the external deliberative system surrounding the Accord, which are also due to the work of staff and members of the Accord. By analysing these shifts, we can judge the legitimacy of this MSI as a system within a system. For each of the functions of our framework, therefore, we show how the early phase of the Accord (2013–18) constitutes an illustrative case of deliberative enrichment (hence its placement in the bottom right quadrant of Figure 1). Such cases have shortcomings in terms of legitimacy as internal systems yet nevertheless contribute to the overall deliberative systems in which they operate.

We selected the Accord as an illustrative case for this article as it is one of the more insight-yielding constellations of non-alignment between legitimacy as a system and legitimacy within a system. The collapse of Rana Plaza is “widely considered a turning point in global efforts to protect workers and ensure fair working conditions” (Cahn & Ahmed, Reference Cahn and Ahmed2020: 1). This is especially so as Bangladesh is the world’s second-largest producer of RMG (after China) and was also the location of some of the world’s worst working conditions in the RMG sector at the time. What was unique about the Accord as a MSI, however, was that it included an enforcement clause whereby brands were to be held legally accountable for their voluntary commitments (Ashwin, Kabeer, & Schüßler, Reference Ashwin, Kabeer and Schüßler2020; Leitheiser, Reference Leitheiser2019; Schuessler et al., Reference Schuessler, Frenkel and Wright2019). In analysing the Accord to address our research question of how this initiative contributed to or undermined the deliberative capacity of the overall deliberative system of governance of the issue it was set up to address, we conduct a comparison of the overall deliberative system for regulating working conditions in Bangladesh before and after the Accord.

Our case analysis draws on publicly available documents provided by the Accord and its member organisations, as well as press coverage and research studies. These documents helped us draw conclusions about both the Accord itself and its institutional environment. Documents were collected between 2013 and 2022 and analysed in a deductive manner against the conceptually established normative functions of MSIs as and within deliberative systems.

The Boundaries of the Accord as a Deliberative System

We define the internal boundaries of the Accord as encompassing all those actors that declared themselves formal members of the Accord: more than two hundred apparel brands, retailers, and importers from more than twenty countries in Europe, North America, Asia, and Australia; two global trade unions; eight Bangladeshi trade unions; and four NGO “witnesses.” These members engaged in deliberation with other nodes in the surrounding deliberative system on the particular issue of the Accord, that is, fire and building safety for workers in RMG supply chains in Bangladesh. The focus issue of the initial Accord was quite narrow, addressing only fire and building safety in the RMG sector and only Bangladeshi factories that directly produced for the export market.

To define the boundaries of the overall system of which the Accord formed a part, we draw attention to the main actors and initiatives with which the Accord interacted as part of a complex deliberative system on the issue of fire and building safety for workers in the Bangladeshi RMG sector. This definition enables us to compare the overall deliberative system at the time when the Accord initially took effect in 2013 to the system as it had developed by the time it expired in 2018.

When the Accord took effect in May 2013, some of the most important actors in the larger deliberative system included retailers sourcing from Bangladesh, consumers, governmental institutions, the International Labour Organization (ILO), NGOs, trade unions, workers, and two Bangladeshi garment export associations: the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) and the Bangladesh Knitwear Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BKMEA). Note, however, that these were only a few of the many diverse actors affected by this issue.

The Accord emerged against the background of a governance void in the regulation of building standards, with the collapse of the Rana Plaza building directly attributed to the Bangladeshi government’s failure to uphold its own standards. In response to the disaster, the government installed a National Action Plan on Fire Safety and Structural Integrity in July 2013, that is, shortly after the Accord came into effect. Other governments, including the US government, reacted to the disaster by withdrawing preferred trading status from Bangladesh (Godfrey, Reference Godfrey2013). Meanwhile, the European Union responded by launching a Sustainability Compact to promote improvements in factory safety in the RMG industry. Beyond these specific responses, the collapse of Rana Plaza triggered an intense debate in the media on the responsibilities of multinational firms in global supply chains. A number of NGOs engaged in this wider debate, for example, the CCC.

Applying our proposed framework, we now evaluate whether and to what extent the Accord as a system within a system ultimately served to promote or undermine the deliberative capacity of the system as a whole, that is, how it impacted and changed the deliberative system for regulating fire and building safety for workers in RMG supply chains in Bangladesh between 2013 and 2018.

Legitimacy of the Accord as a Deliberative System

Assessing the Accord with regard to its legitimacy as a deliberative system entails evaluating how well it fared internally in terms of the three functions of deliberative democracy, that is, authenticity, inclusiveness, and consequentiality. Evaluating authenticity here involves assessing whether the deliberations of the actors within the Accord induced reflection on preferences in a non-coercive way, promoted mutual respect, and were informed by facts and logic. This assessment requires some knowledge of the MSI’s internal structure, starting with the executive organ of the Accord, which consisted of a steering committee (SC) comprising an equal number of representatives from trade unions and company signatories, chaired by a neutral observer from the ILO. An advisory board brought together representatives of the government of Bangladesh, factory owners, and civil society. Importantly, however, this board had no decision-making authority (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2021).

The parity of representation in the SC of the Accord ensured that any decisions could only be arrived at by convincing others. Moreover, the parties in the SC were dependent on each other for the duration of the Accord to an extent that ensured conflicts needed to be solved in a communal and mutually respectful manner. The standards the Accord promoted built on and adapted the previously existing building standards of the national Bangladeshi Building Code, simplified by international building experts to make the code more operational (Accord, 2015). As such, these adapted standards were the result of considering relevant facts and logic. Moreover, both the transparent communication of factory audit reports and the instalment of organisational health and safety committees in factories can be seen as a significant improvement of the traditional audit approach to social standards that had so tragically failed to prevent the collapse of the Rana Plaza building complex (Clean Clothes Campaign, 2013). In terms of its fulfilment of the authentic function of legitimacy as a system, therefore, we argue that the Accord performed reasonably well (Accord, 2017).

Evaluating the inclusive function of the Accord as a deliberative system in itself entails assessing the extent to which this initiative promoted the inclusion of all relevant actors while only excluding those that voluntarily accepted their own exclusion. Given the equal representation afforded on the SC to workers’ representatives and corporations alike, it is clear that considerable effort was exerted to include interests based on equality. Moreover, the Accord’s complaint mechanisms gave workers a voice to demand immediate improvements of unsafe working conditions in their factories (Donaghey & Reinecke, Reference Donaghey and Reinecke2018). However, this does not necessarily mean that all relevant actors and discourses were included; indeed, there are several reasons to believe that not all relevant actors were included in the Accord (Dawkins, Reference Dawkins2021). Firstly, because the unionisation of workers in Bangladesh was still at a very early stage at the time of the Accord’s formation, and especially as women were still vastly underrepresented in unions at this time, despite comprising the majority of the workforce in the country’s RMG sector (International Labour Organization [ILO], 2009), it is questionable whether many workers’ concerns were duly represented in the Accord. Secondly, the SC of the Accord did not include the factory owners who actually needed to implement the factory upgrades stipulated by the initiative. This non-representation was the result of excluding the BGMEA and BKMEA export initiatives (van Buren, Greenwood, Donaghey, & Reinecke, Reference van Buren, Greenwood, Donaghey and Reinecke2021). Thirdly, the Bangladeshi government was not part of the SC and only took an advisory role on the advisory board. The exclusion of factory owners and the minimal role afforded to the Bangladeshi government in particular served to make the situation of the Accord more difficult in the long run, because neither factory owners nor the government supported the continuation of the initiative beyond 2018, even publicly delegitimising the Accord and blaming the MSI for certain problems in the industry (Zajak, Reference Zajak2017). Overall, despite its efforts to balance the power of trade unions and corporations within the SC, the Accord’s under-representation of female workers, factory owners, and the Bangladeshi government led to a power imbalance in favour of Western actors in the supply chain. On this basis, we conclude that the Accord suffered from shortcomings in terms of its inclusiveness as a deliberative system.

Evaluating the consequentiality of the Accord as a deliberative system entails assessing the extent to which it led to tangible outcomes, including changes in the behaviour of its signatories and improvements in the working conditions of the approximately two million workers employed in the 1,650 factories or more covered by the MSI (Accord, 2017). Here it is crucial to note that the possibility afforded in the Accord for legally binding arbitration significantly enhanced the consequentiality of the initiative (Levine & Ambast, Reference Levine and Ambast2020), especially when compared to other MSIs. This power enabled the Accord to stipulate with effect that all signatory retailers and brands must 1) conduct independent inspections of the factories from which they source, 2) publicly report the results of these inspections, and 3) implement and finance any necessary corrective measures. The Accord thus brought about impressive changes in the sourcing strategies of its signatory firms (Huber & Schormair, Reference Huber and Schormair2021; Schuessler et al., Reference Schuessler, Frenkel and Wright2019), leading to major improvements in the fire and building safety of the factories it covered (Wiersma, Reference Wiersma2018). Notwithstanding these achievements, the Accord’s annual report for 2017 acknowledged that health and safety issues were still outstanding in some eight hundred factories by the end of the five-year duration of the 2013 agreement (Accord, 2017: 4): “The Accord signatories realised that the objective of achieving full remediation at all 1,600+ Accord factories by 31 May 2018, the expiry date of the 2013 Accord agreement, was not realistic.” Overall, however, the consequential function of the Accord as a system can be evaluated as having performed reasonably well, especially when compared to other MSIs without legally binding outcomes.

In sum, we evaluate the legitimacy of the Accord as a system as falling short mainly on account of its lack of inclusiveness, despite its authenticity and consequentiality. What needs to be established next is how the Accord interacted with the larger deliberative system of which it formed a part and the extent to which it influenced the deliberative capacity of this overall system.

Legitimacy of the Accord within the Wider Deliberative System

As indicated earlier, the Accord was only one of many actors associated with the governance of fire and building safety in the Bangladesh RMG sector. In this section, we highlight some of the shifts that took place in the wider deliberative system during the period in which the Accord was in effect, again with reference to the criteria of deliberative legitimacy proposed in our framework.

Regarding the authentic function of the Accord within the larger deliberative system, the question that concerns us here is whether the initiative served to promote the capacity of this system to host and facilitate deliberation based on mutual respect and authenticity on issues related to fire and building safety in the Bangladeshi RMG sector. In brief, we conclude that the Accord succeeded in triggering a number of developments that served to redress power imbalances and foster greater mutual respect in the overall deliberative system in favour of workers at the national and international levels. For example, at the national level, the Accord was instrumental in inducing the Bangladeshi government to amend the country’s labour laws to make the process for registering labour unions more transparent (Westervelt, Reference Westervelt2015; Wichterich & Khan, Reference Wichterich and Khan2015). Between 2013 and 2018, the number of registered trade unions increased (Abrams & Sattar, Reference Abrams and Sattar2017), as did the number of participation committees elected by workers within factories (ILO, 2017). In the long run, the Accord also paved the way for the RMG Sustainability Council and the new Accord, both of which have continued efforts to give workers a voice and to promote dialogue on fire and building safety for RMG workers in Bangladesh. Indeed, the new Accord even aims to internationalise these issues.

At the international level, the ambitions of the Accord prompted a number of mainly US retailers to form a company-controlled initiative called the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety (hereinafter the Alliance). Similar to the Accord, the Alliance aimed to improve factories through inspections and upgrades. Although neither as inclusive as the Accord nor as consequential on account of its being a voluntary business initiative and thus not legally binding (Donaghey & Reinecke, Reference Donaghey and Reinecke2018), the Alliance has contributed overall to improving multinational firms’ respect for workers and authentic dialogue with workers.

Evaluating the Accord’s contribution to the authenticity of the overall deliberative system on this issue also entails assessing whether the initiative served to distil, synthesise, and convey to the wider public relevant reasons for its actions derived from fact and logic. On one hand, the Accord did contribute to authentic and respectful deliberation in the wider system, especially in its active engagement with the Alliance and the National Action Plan on joint assessment standards in an effort to avoid the duplication of inspections and align expectations (ILO, 2013). On the other hand, one can argue that there was still a long way to go in this respect, as is clear from the oppressive manner in which the Bangladeshi government handled labour protests for higher wages in 2016 and 2019, resulting in the detention and firing of many unionised workers (Abrams & Sattar, Reference Abrams and Sattar2017). Notwithstanding these important concerns, we conclude that the Accord in its early phase from 2013 to 2018 did make a positive net contribution to improving authentic deliberation within the overall system in which it operated.

We further find evidence that the Accord contributed to the inclusivity of this larger deliberative system, mainly in terms of the greater inclusion of workers as a result of the aforementioned improvements in Bangladeshi labour law and easier access to trade unions. The Accord itself succeeded in improving worker inclusion in unprecedented ways, moreover, not only at the shop floor level but also at the national and transnational levels (Reinecke & Donaghey, Reference Reinecke and Donaghey2021b: 20). At the level of the shop floor, the Accord led to the foundation of new trade unions and participation committees, while at the national level, not only the government but also the BGMEA became more active on the issue of fire and building safety in Bangladesh between 2013 and 2018. At the international level, the Accord triggered the inclusion of workers in a number of MSIs on other worker-relevant issues, including the ACT initiative on living wages (Ashwin et al., Reference Ashwin, Kabeer and Schüßler2020), the German Partnership for Sustainable Textiles on general social and ecological sustainability issues in the RMG sector (Grimm, Reference Grimm2019), and various initiatives by the Ethical Trading Initiative in the United Kingdom.

Focusing more specifically on the extent to which the Accord improved the representation of workers within the overall system, a mixed picture emerges. On one hand, the Accord and the Alliance together did cover the great majority of workers in the Bangladeshi RMG sector, accounting for some twenty-three hundred factories, mainly in the top tiers of the country’s export-oriented RMG factories (ILO & International Finance Corporation [IFC], 2016). According to Anner and Bair (Reference Anner and Bair2016: 11), over 70 per cent of textile workers were covered by inspections through these initiatives, while as few as 11 per cent were completely uncovered by any inspections. On the other hand, this still left some fifteen hundred smaller factories under the auspices of the National Action Plan and a number of factories producing for the domestic market under no supervision at all (ILO & IFC, 2016). Lamentably, those who have suffered most from this marginalisation are the female workers in these factories (Labowitz & Baumann-Pauly, Reference Labowitz and Baumann-Pauly2014). A study conducted by Bossavie, Cho, and Heath (Reference Bossavie, Cho and Heath2019) concluded that the average hourly wages of female workers had fallen significantly within just a few years after the Rana Plaza disaster:

While effects on females’ wages were initially positive right after Rana Plaza in 2013, presumably reflecting the effects of the new minimum wage, females’ wages declined in the following years: they had declined by 10 percent by 2015, and by 20 percent by 2016, compared to pre-Rana Plaza levels (19).

Other studies, by contrast, have discerned positive impacts of the Accord on wages. For example, Kabeer, Huq, and Sulaiman (Reference Kabeer, Huq and Sulaiman2020) found that workers employed in Accord and Alliance factories have generally been more likely to receive the wages they perceive as fair.

Notwithstanding these concerns, in toto, we judge the Accord to have improved the inclusiveness of the overall deliberative system. From this analysis of key shifts in the overall deliberative system from 2013 to 2018, it is clear that the purposeful exclusion of the Bangladeshi government and the BGMEA and BKMEA export initiatives from the SC of the Accord as a system almost certainly served to improve the inclusion of workers within the larger deliberative system.