The death of Charles Pigott in the early summer of 1794 coincided with the rise of Richard Citizen Lee in the LCS. The numerous 1d tracts Lee published in 1795 gave Pigott’s name a short-lived posthumous fame in the radical movement. These publications have also ensured Richard Citizen Lee frequent mention in the scholarship on popular radicalism, despite the brevity of his career. He emerged into radical print culture in May 1794 and less than two years later fled to the United States. Despite his notoriety, exactly who he was and whence he had come puzzled both his allies and enemies alike. He was one of the many who rode the wave of print that rose in the third quarter of the eighteenth century and crashed to the shore in the 1790s. More specifically, he was a product of the explosion of print as a vehicle for religious feeling. In this regard, it is hardly surprising that his fellow abolitionist Thomas Hardy remembered him long afterwards as a ‘patriot bard’, but others in the movement had no stomach for what they regarded as overzealous religious enthusiasm.1 He was either excluded or resigned from the LCS because of his warmth on such matters, but the government ensured that his name became emblematic of radicalism in the weeks that ran up to the passing of the Two Acts at the end of 1795. Citizen Lee was named several times in parliamentary debates, particularly over the question of whether he was ‘the avowed printer and publisher to the Society’.2 Members of both Houses of Parliament visited him in his shop, and even pestered his mother in order to find out more about him. If Citizen Lee was in the public eye in these weeks, he never entirely abandoned his ‘proper’ name. Richard Lee was the author of collections of evangelical, abolitionist, and radical poetry that appeared over 1794–5. Some of the most violent broadsides that issued from his shop at the Tree of Liberty contained lines by ‘R. Lee’ in them. Even his most satirical output continued to insist on the rights of God against the rights of kings, a position he maintained when he rejoined the fray of print politics in Philadelphia after 1796.

Evangelist of print

A transcription from the Treasury Solicitor’s papers of an interrogation which took place on 31 October 1795 illustrates the confusion of the authorities when trying to understand the nature of popular radicalism in the 1790s:

Q. Are these all the productions of Mr. Lee’s pen?

A. Not all, But those that have his Name to them are.

Q. You I suppose are Mr. Lee’s servant.

A. No my name is Lee.

Q. O, then you are Mr. Lee himself?

A. Yes sir.

Q. You must be very industrious to produce such a quantity of matter.

A. There are several persons employed.3

The exchange suggests the protean nature of print radicalism in the 1790s, and the government’s struggle to comprehend it. E. P. Thompson offered a brief description of Lee as ‘one of the few English Jacobins who referred to the guillotine in terms of warm approval’, but he has largely remained as much of a mystery in the historiography of radicalism as he was to the government in 1795.4 Thompson was probably unaware of Lee’s appearance in E. F. Hatfield’s the Poets of the Church (1884). Far from denouncing Lee as a Jacobin, Hatfield commends his ‘devout spirit’. Of course, he probably had no idea that his poet had also been the notorious bookseller of the Tree of Liberty. Whether those who included his poem ‘Eternal Love’ in an American collection under the name of the London Calvinist Maria de Fleury in 1803 and 1804 knew is more debatable.5 More certain is that Lee’s first ventures into print took the path of periodical publication; the route taken by John Thelwall, W. H. Reid, and others who later became involved in the LCS. Both Reid and Lee were products of late eighteenth-century networks where print and religion intertwined.6 Lee eventually flouted many of the constraints of evangelical piety, but he began writing under the patronage of the Evangelical Magazine in 1793–4 with a series of poems over the name ‘Ebenezer’.

The Evangelical Magazine was founded in 1793 by a group of dissenting and Anglican preachers of Calvinist orientation, among them David Bogue and James Steven, associates at the time of LCS-Secretary Thomas Hardy, as we have seen. The aim of the new magazine was to publish in a style ‘level to every one’s capacity, and suited to every one’s time and circumstances’, designed to protect ‘true believers, exposed to the wiles of erroneous teachers who endeavour to perplex their minds, and subvert their faith’.7 At its very inception, the Magazine was concerned to channel popular religious feeling by self-consciously exploiting a medium associated with the circulation of ideas to a new reading public: ‘on account of their extensive circulation, periodical publications have obtained a high degree of importance in the republic of letters … which produced a surprising revolution in sentiments and manners’. Bogue had already, as we have seen, anonymously addressed the court of public opinion on the repeal of the Test and Corporation Act and on the significance of the French Revolution. Like most eighteenth-century periodicals, the Evangelical encouraged its readers to become writers, especially those who were drawn from outside the ‘literate’ classes. Lee was encouraged enough to gather his poems into Flowers from Sharon, published at the beginning of 1794, now proudly using his own name as author.

Lee prefaced Flowers from Sharon with the kind of apology for its defects typical of those who had newly entered the republic of letters:

It is not from a vain Supposition of their Poetical Merit, that the ensuing Sheets are offered to the Public; but from a Conviction of the Divine Truths they contain; Truths which, I own, fallen and depraved Reason will always stumble at; and which the unregenerate Heart will never cordially receive; they are too humbling for proud Nature to be in love with; – too dazzling for carnal Eyes to behold. But they are Truths which the christian embraces, and holds fast as his chief treasure. From a real Experience of their divine Power in his Heart, he derives his only Support and Comfort in this wretched Vale of Tears.8

Here, the stress on the unmediated experience of grace provides an unstable mix of deference and self-assertion. Compare the preface attached to James Wheeler’s posthumous The Rose of Sharon: A Poem (1790). The editor makes a great deal of Wheeler ‘being with respect to human learning an illiterate (though doubtless sincere) Christian’. The apologia goes on to suggest that the poem ‘may very probably receive the censures of the critic. Yet the serious Christian Reader will ... discern so much of real experimental religion as may afford him both pleasure and profit.’9 In Lee’s case, the Evangelical Magazine provided a review of Flowers from Sharon that praised the genuinely ‘experimental’ feeling of its former contributor, but simultaneously registered a concern over his presumption that incorrectness would be overlooked in favour of the authenticity of his religious feelings:

This is perhaps more than a writer is entitled to expect, when he claims the public attention; especially as defects in grammar, accent, rhyme, and metre, might have been removed by the previous correction of some judicious friend. However, these poems, published, apparently, ‘with all their imperfections on their head’, afford the stronger evidence of being genuine; and many of them are superior, even in correctness, to what is naturally looked for in the production of so young a person, who has received little assistance from education, and whose occupation we understand to be that of a laborious mechanic.10

Such prefaces and reviews were ways of circumscribing the possibilities available in print for the ‘laborious mechanic’. Self-taught poets could be valued for their ‘genuine’ effusions of the heart, as Reid was when brought forward by James Perry in the Gazetteer, but this was not quite the same thing as valuing them as ‘poets’ in their own right. To do so would have meant encouraging them to abandon what polite commentators perceived as their proper position within the social hierarchy, a fear repeatedly sounded by reviewers. Faced with John Thelwall’s poetry in 1801, Francis Jeffrey writing in the Edinburgh Review identified the aspirations of such men in print as ‘a pleasant a way to distinction, to those who are without the advantages of birth or fortune, that we need not wonder if more are drawn into it, than are qualified to reach the place of their destination’. His review goes on to imply that such cultural pretensions had stoked the fires of the popular radicalism of the previous decade: ‘shoemakers and tailors astonish the world with plans for reforming the constitution, and with effusions of relative and social feeling’.11

Jeffrey saw Thelwall as someone who mistakenly thought a secular version of enthusiasm could compensate for birth, education, and cultural capital more generally. Lee, for his part, added a conviction of divine inspiration into this mix. Over the course of 1794, he followed precisely the trajectory that commentators like Jeffrey feared, making his conviction the basis of plans for reforming the constitution. In Flowers from Sharon that journey is only shadowed in his fierce confidence in the saving power of grace. ‘Eternal Love’, the first poem in the collection, asserts the unity of the believer with the divine, (‘one with the father, with the spirit one’) and looks to a day when the shout ‘grace! free grace!’ shall ‘re-echo thro’ the Skies!’ Lee’s collection is pervaded by a faith in the sufficiency of his own spiritual illumination. Later in his own career, Bogue and his pupil James Bennett identified such confidence as the besetting sin of uneducated men who had never actually read Calvin, ‘the popular poison, a bastard zeal for the doctrine of salvation by grace’.12 Ironically, the Evangelical Magazine itself was criticised for giving rein to such excesses of popular religious feeling. In 1800, Reid, now writing as a turncoat after his arrest at an LCS meeting, identified ‘the Evangelical and other Magazines, still in circulation’ for stirring up a popular taste for prophetic illumination and enthusiastic conversion narratives. He would have known as he had travelled this road himself.13

The exact details of Lee’s religious affiliations in 1793–4 are not easy to trace. One of the poems collected in Flowers from Sharon mentions a lecture ‘at the Adelphi Chapel, by the Rev Grove’. Thomas Grove had been expelled from Oxford in 1768 for ‘Methodism’. He was in London in 1793–4 acting as one of several ministers preaching at the Adelphi, which had no settled preacher at the time. John Feltham’s Picture of London (1802) mentions Grove disapprovingly as one of a group of Calvinists ‘celebrated for their zeal in addressing large auditories’.14 The list of booksellers on the title page of Flowers from Sharon further helps to elucidate his religious context. They include Jordan, Matthews, Parsons, and Terry. Jordan, of course, was the original publisher of Paine’s Rights of Man. Parsons published Merry’s Fenelon in 1795, not to mention other works related to reform, but he also sold a great variety of popular religious material. In 1792, Jordan, Matthews, and Terry had also collaborated to republish an ‘old ranter’ tract from the seventeenth century, Samuel (Cobbler) How’s The Sufficiency of the Spirit’s Teaching. Reid later cited How’s book, somewhat improbably, as the source of Tom Paine’s idea that ‘every man’s mind is his own church’.15 How’s tract stresses the sufficiency of the faith of the poor believer over the knowledge of ‘the wise, rich, noble, and learned’.16 For his part, Terry was accused of peddling Paine’s Rights of Man to the congregation of William Huntington’s Providence Chapel. By 1794 he was certainly publishing millenarian tracts feeding off the sense of expectancy generated by the French Revolution.17 Flowers from Sharon participated in and encouraged this expectation, but before 1794 was out Lee had made good on its potential by emerging as a member of the LCS.

The emergence of the citizen

Despite the potential overlaps in their religious affiliations, Thomas Hardy claimed in his Memoir not to have known Lee personally, conceivably the case since the poet did not gain any serious profile in the LCS until after Hardy’s imprisonment in May 1794.18 Nevertheless, Hardy’s arrest and the subsequent death of his wife clearly fired the uneven and incomplete transformation of the author of Flowers from Sharon into Citizen Lee. This development did not entail the abandonment of religion for politics. One version of what happened to Lee is found in James Powell’s letter to the Treasury Solicitor discussed in Part i. Powell claims that Lee had become well known in radical circles for his exertions on behalf of the patriots arrested in May 1794. The chronology hazily sketched in Powell’s letter implies he became acquainted with Lee at Eaton’s shop.19 Describing him as principal clerk at Perchard’s in Chatham Square, rather than the ‘laborious mechanic’ assumed by the puff in the Evangelical Magazine, Powell says Lee had been ‘very active in supporting the subscriptions for the persons imprisoned & very liberal himself. he was very popular in the society’. His most obvious contribution to raising money for the prisoners was the poem on the death of Hardy’s wife, discussed earlier. Lydia Hardy had died on 27 August 1794, while her husband was still awaiting trial. Lee had already published poetry under his proper name in Pig’s Meat, but after the arrests in May he may have thought it prudent to withhold it now. Two of the poems issued in Pig’s Meat also appeared in a cheaply produced four-page pamphlet under the title the Death of Despotism and the Doom of Tyrants, which does bear his name. Probably published much later in the year, after the acquittals, ‘The Triumph of Liberty’ appears recast as the title poem in the Death of Despotism, but ‘The Rights of God’ keeps its original title, with the addition of a fourth stanza.20 These poems were also gathered into the collection Lee next published, probably at the very end of 1794, under variants of the title Songs from the rock.21

Lee issued a handbill calling for subscriptions for Songs from the rock. The verso has an advertisement for Flowers from Sharon that includes a list of recommendations from clergymen with Hardy’s minister James Steven among them. Booksellers accepting subscriptions for the new volume were the radicals Eaton, Smith, and Symonds, along with Jordan and Parsons from among those who had sold Flowers from Sharon. The published volumes of Songs from the rock carry a note announcing that ‘several of the following Poems have suffered much through Omissions and Alterations, which the Fear of Persecution induced the Printer to make, though contrary to the Author’s wishes’. Probably for much the same reason the list of subscribers promised on the proposal did not appear. Several names are blanked out in the poems, but this scarcely reduces the seditious nature of the content.22 Some of these poems were to be reprinted or excerpted in the broadsides and pamphlets of 1795 that bear the imprint of Citizen Lee, but the collection in the form(s) it finally appeared seems to have been shaped by the optimism surrounding the acquittals at the treason trials. The collection opens with ‘The Return of the Suffering Patriots’ and the title page, which, whatever its final form, always mentions ‘a congratulatory address to Thomas Hardy’. There is also a ‘Hymn to the God of Freedom for the Fifth of November’, the day of Hardy’s acquittal. Neither is mentioned in the subscription flyer for the volume. Some versions of the volume describe the address to Hardy as ‘added’ and lists of publications for sale by Lee from 1795 have it listed as a separate item selling for 1d. The circumstantial evidence is that the volume had been in development before the acquittals, but was published with additional poems after Hardy was freed.

‘Tribute to Civic Gratitude’ insists on the centrality of Christian belief to radical politics. Hardy was a specifically ‘christian hero’ as Lee explained in a note where he confronts ‘infidelity’, and denies any idea that ‘pure Christianity is inimical to the Cause of Freedom’.23 No doubt the Lord Chief Justice – in the unlikely event he ever read them – would have felt that these words vindicated his summing up at Hardy’s trial, but they are directed as much against infidels in the LCS as against the established order. Given this account of Hardy as a specifically Christian hero, the persistence of themes from Flowers from Sharon in the volume as a whole is unsurprising. They include the abolitionism of ‘On the Emancipation of our Negro Brethren in America’ and the millenarianism of ‘Babylon’s Fall or the Overthrow of Papal Tyranny’ and ‘A Call to Protestant Patriots’. The last presents plans for British troops to be used to protect the Vatican against French Republican armies as a sign that the British government is in league with the Beast of Revelation. Possibly Lee was among those LCS members sympathetic to Gordon and the Protestant Association. ‘Retribution; or the Rewards of Benevolence and of Oppression’ is a celebration of the ‘rich Glories of free grace’ in a levelling vision of the Judgment Day when ‘Monarchs fall beneath thy Frown’.24 Hatred of monarchy as a human institution set up over against the freedom granted by God’s grace is a keynote of Lee’s radicalism, pushing beyond the respect for George III usually found – at least ostensibly – in most ‘official’ LCS publications. The zeal of Lee’s radicalism was clearly bound up with the warmth of his religious convictions, a fact that caused problems for him within the LCS. Most of the poems in Songs from the rock are characterised by violent language, an unequivocal statement of faith in divine power, and the claim to see and feel that power directly at work in the world.

Nevertheless, it would be quite wrong to suggest that Lee did not have ‘literary’ aspirations. ‘Reform offered a more practical kind of emancipation or empowerment’, as Mark Philp has suggested, ‘together with a degree of social mobility.’25 There was a distinctly literary aspect to these ambitions for some members of the radical societies. John Barrell has identified the pastoral bent of much of the poetry found in Pig’s Meat and Politics for the People with the literary and social aspirations of those who joined the societies.26 Lee’s references and allusions to the eighteenth-century poetic canon, including James Thomson and Edward Young, signals a similar desire to join the world of belles lettres. Complicating matters, but to similar effect, Lee’s religious poetry brought him out of the clerk’s office and into the public sphere. Flowers from Sharon, at 3s, looks as if it was intended for something like the better-off purchasers of the Evangelical Magazine.27 Devotional poetry offered Lee a form of social mobility and an opportunity for self-definition underwritten by the idea of a grace freely available even to the poorest members of society, but Songs from the rock also lays claim to a degree of cultural capital from more literary sources. The volume quotes lines from Joseph Addison, James Thomson, and Young, not to mention the fashionable religious verse of Salomon Gessner’s sacred poem The Death of Abel, translated by Mary Collyer in 1761, and reissued regularly thereafter.28 The collection also contains a number of love poems addressed to ‘Aminta’ (a name taken from a Tasso play). One of the Aminta poems, Lee acknowledged, had already appeared in a magazine. At one point in Songs from the rock, he even quotes from Della Crusca.29 Songs from the rock was available at 1s 6d, ‘in order to accommodate every Class of Readers’, but also in a de luxe edition on fine paper at 2s 6d. Even at his radical zenith, when he traded as the bookseller Citizen Lee, this de luxe edition remained available. Powell’s bitter account of Lee’s celebrity in radical conversazione suggests he also struck a figure as a poet of the people in the debating clubs that flourished in the mid-1790s.

These aspirations do not mean Lee was simply self-interested, but involved in a species of self-fashioning in print. Lee’s notion of his right to participate in the public sphere rested not simply on what we might recognise as personal improvement through education, or the universality of private judgement, or even on the power of his imagination as such, but primarily on his confidence in the gift of free grace. Lee himself described Songs from the rock as an attempt ‘to Promote the united cause of God and Man’.30 Nearly everything he later published continues to affirm the confidence in the sufficiency of his own spiritual illumination over ‘unregenerate reason’ set out in Flowers from Sharon. Thelwall usually identified such attitudes with the retrograde enthusiasm of the Civil War, but Lee cannot simply be regarded as a throwback to the 1640s. His writing is the product of a complex interaction between such tendencies and emergent aspects of late eighteenth-century print culture. The literary effects of the cult of poetic sensibility, running through his poetic references to Addison, Thomson, Young, and Della Crusca, who inspired so much magazine verse between them, informs both the love poetry and the more general celebration of benevolence in Songs from the rock.

In 1795, Lee even published a translation of an excerpt from Rousseau’s Emile, under the title The Gospel of Reason. Carefully culled and translated from the confession of faith of the Savoyard vicar, it presents Rousseau as an advocate of a religion of free grace rather than an Enlightenment philosophe:

the majesty which reigns in the sacred writing, fills me with a solemn kind of astonishment; and … the sanctity of the Gospel speaks in a powerful and commanding language to the feelings of my heart.

The initial reception of Rousseau in England had stressed the ‘heat of enthusiasm’ in Emile and often represented him as a brave defender of Protestant freedom of conscience. The Gospel of Reason goes further, presenting Rousseau as a radical apostle of the sufficiency of the spirit’s teaching, or regenerate reason.31 If Merry and Pigott presented their readers with an unstable cocktail of sensibility and French materialism in the cause of reform, Lee’s poetry combines sentimentalism with homegrown religious enthusiasm. Merry and Pigott also shared a particular and often personal animus towards Pitt, possibly because they knew and were familiar with the Prime Minister’s social world. They were capable of attacking the Crown’s encroachment on the authority of Parliament, and sometimes even the institution of monarchy itself, at their most republican, but Lee’s radical Protestant imagination provides his writing with a sense of the fundamental wickedness of monarchy. Kingship becomes a form of idolatry. Pitt is its high priest. Lee’s confidence in the voice of God speaking directly to his heart enabled him to publish some of the most incendiary material put out by radical presses in the 1790s, underwritten by what the Monthly Review called ‘the divine right of republics’:

Spence printed these lines in Pig’s Meat, perhaps because he and Lee shared an inheritance in this kind of religious feeling. Both of them saw the compact of church and state as a blasphemous usurpation of the rights of God. This perspective suffused everything Lee published in 1795, including some very black satire.33

The Tree of Liberty, 1795

Broadsides and short pamphlets, seldom costing more than a penny, poured from Lee’s press over the course of 1795. Although it is not exactly clear when he set up as a bookseller, his shop soon became famous as the Tree of Liberty, or sometimes the British Tree of Liberty. A series of addresses in central London were its home: first, at a shop his mother seems to have owned in St Ann’s Street, Soho; then at the Haymarket some time before the end of March 1795, before moving back to Soho in Berwick Street; finally coming to rest in October 1795 on the Strand. Hostile attention from church and king supporters played their part in these shifts. Lee issued a handbill from the Haymarket on 21 March 1795 accusing them of ‘maliciously attempt[ing] to deface and obliterate the good name and honourable Title of citizen lee’. It seems the government’s supporters had taken to attacking his shop sign, possibly only recently put up to advertise the new premises in the Haymarket. In one sense, ‘the good name and honourable Title’ of ‘Citizen’ distinguished the cheap radical publisher from the literary aspirations of ‘Richard Lee’, except that his poetry did appear on the playbills and other penny publications, sometimes with his name attached. ‘R. Lee’ was also used in the colophon of some pamphlets issued from the Tree of Liberty.34 He did not, then, neatly dissociate his literary ambitions from his radical politics. Instead the cheap publications he issued from the Tree of Liberty combine the violence of the poems of Songs from the rock, sometimes explicitly invoking divine aid, with a grotesque sense of carnival, delighting in imagining the death of Pitt, and even – perhaps Lee’s trademark – the demise of the king.

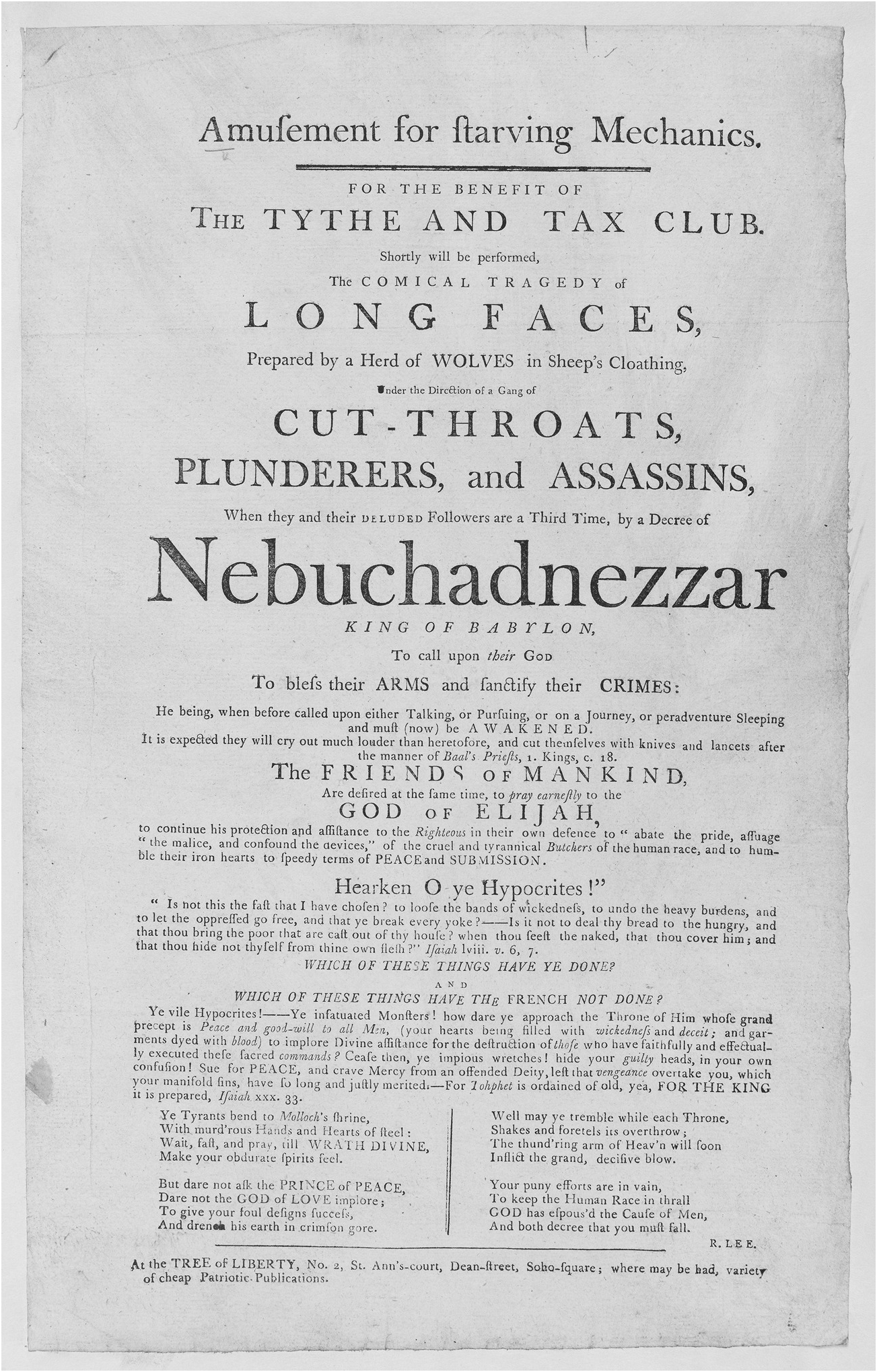

In February, Lee reissued a mock playbill ‘for the benefit of the Tythe and Tax Club’. (Figure. 8). An earlier version of the bill had been discussed at Thelwall’s trial because of its identification of the king with Nebuchadnezzar. Lee now added additional matter: ‘For the Amusement of Starving Mechanics’. Possibly Lee was exploiting the buzz surrounding the millenarian prophecies of Richard Brothers.35 Brothers identified George III with Nebuchadnezzar in a series of prophecies issued in 1794. London’s downfall as the modern Babylon was prophesied. While there is nothing to suggest that Lee was a follower of Brothers, his poetry participated in and helped sustain the air of millenarian expectancy the Paddington Prophet had generated at the end of the previous year. Apart from giving the Tythe and Tax Club its new title, Lee also added four quatrains of verse above his own name:

If these lines perpetuate the idea of the ungodliness of monarchy that runs through Songs from the rock, generally speaking the publisher Citizen Lee was much more of a satirist than the poet Richard Lee.

Fig 8 Amusement for Starving Mechanics. For the benefit of the Tythe and Tax Club. Shortly will be performed, the comical tragedy of Long Faces, etc. [A squib.] [1795?].

From around the middle of July, the Tree of Liberty was the prime depot for the dissemination of Pigott’s satires in various short compilations, beginning with the Rights of Kings.36 The author died before the treason trials came on, but Lee used his words to poke fun at the idea that imagining the king’s death had been construed as treason there. ‘Monarch’, was simply, ‘a word which in a few years is likely to be obsolete.’37 The lack of prosecutions for sedition in 1795 may have given Lee a sense of safety from the law on sedition. The satires on the Prime Minister built to a crescendo when the Telegraph issued a series in late August. They began with an account of Pitt in the throes of ‘a violent diarrhoea’. He is imagined passing away after two days of humiliating confessions. Dissection reveals Pitt’s tongue to be ‘quite hollow; and in short, the most deceiving tongue in all respects that ever came under the operator’s knife’. Using a joke continually made against the Prime Minister in the newspapers, ‘the sexual distinctions in this case were not easily to be discerned’.38 Printed in full as Admirable Satire on the Death, Dissection, and Funeral Procession, & Epitaph of Mr. Pitt!!! from the newspaper’s office, the joke was extended by the addition of a ‘dreadful apparition’. Lee was one of several publishers competing over who could offer the best edition. The Voice of the People, published by Lee at the end of September, closes with an advertisement for the ‘only genuine Edition, corrected by the Author’.39 By late November, Lee had a sixth edition out from the new shop on the Strand, with additional material ‘by another hand’ purporting to be taken from Pitt’s last will and testament. In the will, John Bull is bequeathed Pitt’s ‘curious Magic Lanthorn, with which he has for many years past amused or alarmed his said honest, simple-minded friend, by showing him conquests abroad, or plots at home’. Advertisements for Poems on Various Occasions by Lee and a new edition of Wollstonecraft’s Rights of Woman appeared on the last page. Neither seems ever to have been published, unless the first was another repackaging of Songs from the rock.40

John Barrell has suggested that once the Two Acts were introduced into Parliament radical imaginings of the death of those in authority increased in intensity and started to target the king himself.41 In the radical societies, the Two Acts were widely regarded as a kind of treason against traditional liberties. If Pitt and Grenville defended them as a response to a state of exception, so radicals used them to suggest that the compact between the state and the people was being broken. Addressing the inhabitants of Westminster petitioning against the passage of the bills on 16 November, Sheridan caught the mood in a speech published by Lee: ‘the day will come, when the law, weak as it is said to be at present, will be found strong enough to bring to the scaffold your corrupt oppressors’.42 Fox was reportedly alarmed at the violence of the speech and pulled him back to his seat. The list of items for sale at the Tree of Liberty issued with the account of this meeting, in contrast, was pushing further and further forward with the idea that Pitt’s government was destroying the constitution it purported to defend. The Happy Reign of George the Last, for instance, addressed to ‘the little tradesmen and labouring poor’, calls for the people to throw off the monarchy and set up ‘parochial and village associations’, after the manner of Spence’s land plan.43 Lee did not write most of the pamphlets and broadsides he published. There were too many of them. He told the Privy Council that there were numerous people employed in his shop, but he was also fed material – directly or indirectly – by the circle at the Telegraph or those with connections to the Sheridan circle, like Merry and Joseph Jekyll, who provided Pittachio copy.44 The satires on the death of Pitt suggest a degree of insider knowledge, despite – or perhaps, because of – their evident delight in the evisceration of Pitt. Lee encouraged aspiring satirists, whoever they might be, to send work to him at the Tree of Liberty: ‘Communications of Merit, either in Prose or Verse, will be gratefully acknowledged, if directed (post paid) to R. LEE.’ Sheridan later claimed many of them were written and distributed by spies and informers to provide the justification for the Two Acts. No doubt some of them were. Lee may not have enquired too closely into the authorship of what he published, as the misattribution to Merry of the sophisticated pastoral satire Pitti-Clout & Dun-Cuddy suggests. Lee’s primary concern was to put as much into circulation as possible that undermined respect for things as they were.

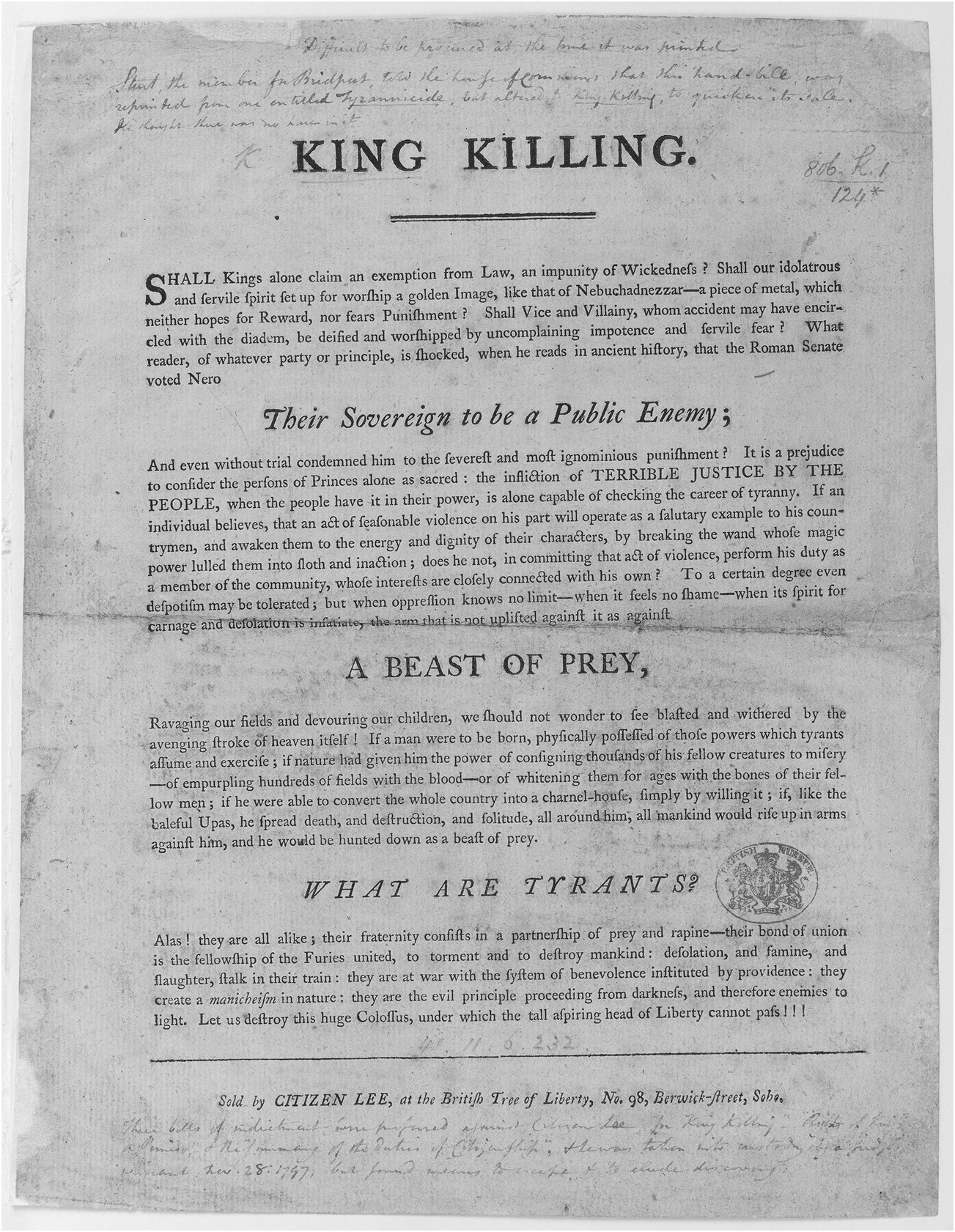

His eagerness to challenge the legitimacy of monarchy was to prove his undoing, or, at least, provided the government with an opportunity it had been preparing. The handbill primarily responsible for bringing Lee to the government’s attention bore the title King Killing (see Figure. 9), but he did not write it on his own. The paragraphs are culled from an essay ‘On Tyrannicide’ written by John Pitchford, early in 1795, for the first issue of The Cabinet.45 Far from itself advocating king killing, ‘On Tyrannicide’ is primarily a discussion of the execution of Louis XVI that concludes that most advocates of king killing ‘have been dazzled by a few splendid names’. Lee completely distorts his source, omits its view that tyrannicide is ‘unlawful, useless, and pernicious’, and simply reprints as republican polemic the few paragraphs The Cabinet provided, perhaps mischievously, as examples of imprudent ‘declamation’. King Killing as published by Lee was consonant with the view that monarchy was a form of blasphemy expressed in many of the poems in Songs from the rock. The same theme appears as black comedy in the satirical Rights of the Devil, available from the Tree of Liberty at the same time, which presents Hell as the ‘fountain head’ of all terrestrial monarchies and identifies religious establishments as ‘the greatest enemies to religion and morality’.46

Fig 9 King Killing [A hand bill, reprinted from one entitled ‘Tyrannicide’.] [London, 1797 [1795?]].

Lee wanted to reach as wide an audience as possible with his cheap publications. He often subdivided his material in order to bring out cheaper versions, as for instance with the separate sale of his poetic address to Hardy or the series derived from Pigott. Charles Sturt claimed that ‘Tyrannicide’ was dropped as a title in favour of King Killing, ‘because the people otherwise would not buy it’.47 Lee seems to have been hawking King Killing along with his other wares at the huge LCS rally held in Copenhagen Fields on 26 October, where a hostile crowd shouted anti-Pitt slogans, called for the end of the war, and complained at the economic distress of a virtual famine year. On 29 October, the king’s coach was attacked on the way to the opening of Parliament, when a stone was thrown through one of the windows. Someone in the crowd wrenched open a door. Pitt’s government used the incident to move against the radical movement and bring the Two Acts before Parliament. Lee was the most flagrant example of radical extremism available. On 16 November, the Attorney General, John Scott, came to Parliament to name him as ‘printer to the London Corresponding Society’.48 The aim was to represent King Killing and the other pamphlets as official publications of the LCS. Scott read the definition of Royalty from Rights of Princes: ‘the curse of God in his wrath to man’. He was careful not to read other parts that might have brought guffaws from the benches. The next day Lord Mornington told the House of Peers that he had visited Lee’s shop and come away with The Happy Reign of King George the Last.49 Mornington insisted that the various imaginings of the death of the king amounted to ‘French treason’. During a brief period of temporary and uneasy cooperation with extra-parliamentary reformers to campaign against the Two Acts, the Opposition tried to defend the LCS by distancing it from Lee.50 Presenting a petition against the two Bills from Sheffield, Charles Sturt rose in Parliament to confirm that Lee’s mother had told him that her son was no longer a member.51 Several other sources, as we have seen, suggest that Lee had fallen out with the leadership over the spread of infidelity in the movement. Reid later claimed that

Bone and Lee, two seceding members, and booksellers by profession, were proscribed for refusing to sell Volney’s Ruins of Empire, and Paine’s Age of Reason; and that refusal construed into a censure upon the weakness of their intellects.52

The LCS issued a statement distancing itself from the bookseller the day after Mornington’s speech, but the next day his name still appeared among those booksellers accepting signatures on the LCS petition against the Two Acts.53

After a year in which there had been no prosecutions for seditious libel in London, true bills were found against Lee on 28 November.54 The pamphlets named on the indictments were King Killing, the Rights of Princes and a Summary of the Duties of Citizenship. Lee was arrested the same evening. He did not stay in prison long. By 19 December, the True Briton was announcing his escape. The Times provided detail:

The escape of Citizen Lee, from the house of the Officer in Bow Street, was thus effected. Three women, or persons in women’s cloaths, went to visit him. Their number having been unnoticed by the attendants, four persons in women’s cloaths quitted the house. One of these was the person called Citizen Lee, who has not since been heard of.

Powell later claimed, as we know, that Lee fled with his wife.55 The government may not have done much to prevent his escape. He had served his purpose in terms of the Two Acts being piloted through Parliament. Lee made for Philadelphia, like many others who fled from Pitt’s system of spies and informers. Durey places Lee among those émigrés who contributed to the development of Jeffersonian ideology.56 Federalists hated their democratic politics, and the Alien and Sedition Acts were in part directed against them. One historian has commented of this period of American politics that ‘foreigners seemed to get one sniff of printers’ ink and become loyal Jeffersonians’, but Lee was not quite so comfortable a fit and continued to insist on the rights of God over the compromises of earthly institutions.57

Written on the Atlantic Ocean

Lee arrived in Philadelphia to find himself in the febrile atmosphere building up to the passing of the Alien and Sedition Act. He seems quickly to have been drawn towards the democratic wing of the anti-Federalist movement. He attracted enough notice to win a place in Cobbett’s scathing attacks on what he saw as American Jacobinism, unsurprisingly, as Lee was starting his bookshop up right under Cobbett’s nose in downtown Philadelphia.58 Cobbett’s vicious attacks on Lee – ‘a man who publickly preached Regicide and Rebellion’ – are predicated on his knowledge of the English context, but insist that such men had no place in thinking about politics on either side of the Atlantic. Cobbett places Lee squarely among Philadelphia’s crowds of ‘raggamuffins, tatterdemalions, and shabby freemen, strolling about idle’.59 Dismissed as one of the ‘animals … hardly worth naming’, Cobbett could not resist mentioning the fact that he ‘like a true sans-culotte slipped out of Newgate in petticoats’. In September 1798, Cobbett pithily summarised Lee’s American career in a note: ‘Citizen Lee first attempted a magazine, then a book, and then he tried what could be got by travelling, and he is at last comfortably lodged in New-York jail.’ Probably Lee was in debt, but he may also have been picked up under the Alien and Sedition Act of 1798.60

Jane Douglas suggested that Lee must have died soon after arriving in the United States, but the broad outline of Cobbett’s claim seems to be corroborated by the trail left in print.61 The ‘magazine’ was the American Universal Magazine (AUM). First published on Monday, 2 January 1797, the AUM is a familiar eighteenth-century blend of original essays, tales, poetry, scientific news, much recycled material, and reports of proceedings in Congress. Running as a weekly over its first four issues, it directly encouraged the debate of democratic forms and principles. The very first issue published an essay insisting on the importance of the periodical press for the diffusion of knowledge. Reiterating in theory Lee’s own practice, it insisted ‘that much more service is done in the aggregate mass of periodical publications than evil is occasioned by particular parts’.62 Lee was aligning himself with the democratic idea of the republic as a nation of ‘citizen readers’ described by Cotlar. Lee’s name appeared, for instance, on the subscription list for Thomas Carpenter’s American senator (1796–7). Stocked in Lee’s shop on Chestnut Street, the American senator was designed to ensure the population at large had access to the democratic process for purposes of discussion and debate (contradicting the more limited Hamiltonian notion of participatory democracy as properly confined to election day).63 Certainly the account of presidential inauguration given in the AUM sharply contrasts the visibility of Congress with the pomp and awe of Parliament:

This ceremony and spectacle must have afforded high satisfaction and delight to every genuine Republican. To behold a fellow citizen, raised by the voice of the People to be the First Magistrate of a free nation, and to see, at the same time, he who lately filled the Presidential Chair, attending the inauguration of his successor in office, as a private citizen, beautifully exemplified the simplicity and excellence of the Republican system, in opposition to hereditary monarchical governments, where all is conducted by a few powerful individuals, amidst all the pomp, splendor and magnificence of courts, independent of the great body of the People.64

AUM subscribed to the more radical line sketched out in Rights of Man that ‘the independence of America, considered merely as a separation from England, would have been matter but of little importance, had it not been accompanied by a revolution in the principles and practice of governments’. Congress is imagined as Paine’s ‘open theatre of the world’.

Lee maintained a notion of a transatlantic radicalism, a sense of the Revolution controversy as a universal struggle that transcended national boundaries. His religious affiliations, as with Thomas Hardy, helped maintain this internationalist perspective. The providential basis of Lee’s thinking gave his publications in Britain and the United States their uncompromising edge, but he had become openminded enough now to advertise forthcoming editions of Volney’s Ruins and Godwin’s Political justice in the very first number of AUM, presumably because they provided ammunition for his campaign against the compact of church and state. At least one poem published in AUM, ‘Providence, saving the oppressed and working the destruction of Tyrants’, contained all the millenarian ire of his own poetry. A subtitle describes it as ‘Written on the Atlantic Ocean’. Given the emphasis on ‘deliverance from the tyrant’s rage’ and the general tenor of its language, it may well have been composed by Lee himself:

The AUM also maintains the abolitionist principles that permeate Lee’s London publications, printing letters on the subject of American slavery from Morgan John Rhees and Edward Rushton: ‘Of all the slave holders under heaven those of the United States appear to me the most reprehensible; for man never is so truly odious as when he inflicts on others that which he himself abominates.’66 Lee joined the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery in December 1796, only a few months after his arrival. If his religious enthusiasm had caused difficulties for him with the LCS, the same may well have been true for his position within American democratic circles, especially where it sustained his firm abolitionist position.67 Lee was a print evangelist. His was perhaps the most uncompromising version of the Protestant myth of print magic from the radicalism of the 1790s, but one that resisted any attempt to let the idea of a disinterested public usurp the word of God as the spirit that informed its transformative power. For someone like John Thelwall, the subject of my final chapter, such attitudes represented a disgraceful throwback to ‘enthusiasm’ that embarrassed his idea of popular radicalism as the expression of a popular enlightenment based on reason and benevolence.