Introduction: The Affective Economy of Violence

Violence Sells

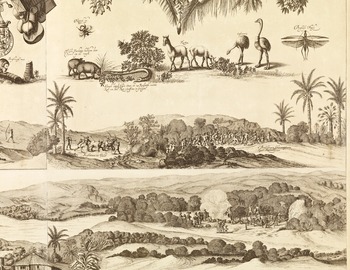

The world, as presented in Romeyn de Hooghe’s engraving Spaanse wreedheden in West-Indië (Spanish Tyranny in the West Indies) (Figure 1), is an extremely violent place. This early modern print draws the viewer into a grim explosion of violent scenes crammed into one complex image of Spanish conduct in the colonies. Attracting Western readers to the ‘exotic’ world of the West Indies, with palm trees, tree huts and volcanoes, the artist confronts the viewer with a series of examples of violence. These range from the military attacks of Alvarado and his conquistadors in Brazil, and their destruction of Indigenous buildings, via the brutal slaughtering of the women and children, thrown into a pit filled with spikes, to the ‘burning and boiling’ of chiefs and the feeding of their bodies to the dogs and birds. The cruelty and disrespect for the human body are not limited to the Spanish conquerors: the West Indian cannibals are likewise abusing human bodies. Essentially, the image suggests that violence is not only a fundamental aspect of human behaviour but an altogether natural phenomenon. Volcanic eruptions, fires and floods violate human civilisation, but human existence is also analogous to these phenomena. The dramatic, dynamic narrative of this detailed, high-quality engraving by the hand of the skilled artist Romeyn de Hooghe thus imagines the human, animal and natural world as a most violent place.

Figure 1 Romeyn de Hooghe, Spaanse wreedheden in West-Indië, in Les Indes Orientales et Occidentales, et autres lieux […]. (Leiden: Pieter van der Aa, c.1700).

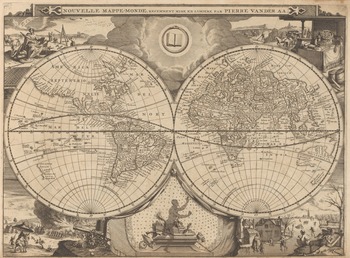

De Hooghe presented this elaborate engraving in a beautiful oblong book of around fifty folio prints, printed with care in c.1700 by the famous Leiden publisher Peter van der Aa, entitled Les Indes Orientales et Occidentales, et autres lieux […] (The West and East Indies and Other Places Represented in Very Beautiful Pictures). For this catalogue of his artistic mastery, de Hooghe re-edited various engravings he had produced decades earlier for the Curious Remarks about the Most Remarkable Matters of the East and West Indies, a multivolume ethnographic study by Simon de Vries (1682). Extracting his engravings from this previous study, in Les Indes Orientales et Occidentales de Hooghe presented images without the interference of long pieces of text. The addition of bilingual (French/Dutch) colophons helped the viewer understand what they were looking at, without the need to really take their eyes off the image. De Hooghe thus turned the reader into a spectator.

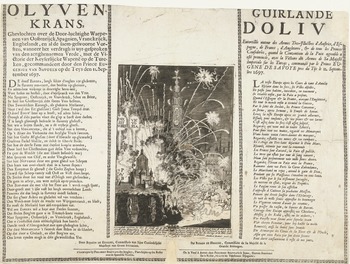

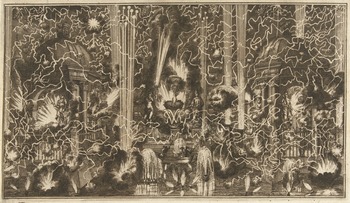

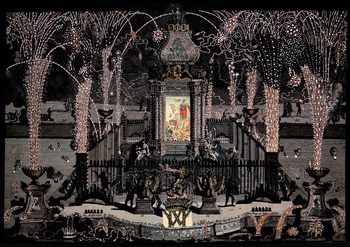

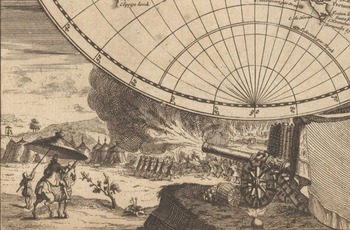

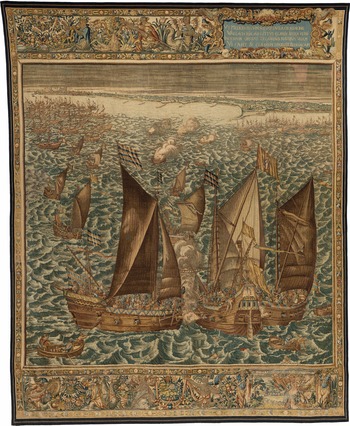

From this one depiction of Spanish tyranny, the viewer could move on to new scenes of violence: the cruel punishments of the Asian magistrates, the uncivilised medical ‘cures’ of Indian doctors, the dehumanising slave trade of the Turks, the slaughter of children in Abyssinia, human sacrifice in Mexico, the pain of poverty, the rape of women, the deafening sound of fireworks, the relentless force of natural disasters and the grotesque, devouring monsters of the Asian and African animal kingdoms (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Romeyn de Hooghe, Aziatische en Afrikaanse dieren, in Les Indes Orientales et Occidentales, et autres lieux […]. (Leiden: Pieter van der Aa, 1702).

Moving from image to image, the viewer could experience different emotions: shock, awe, anger, disgust, curiosity or pleasure. Our contention in what follows is, however, that this abundance of images engineered an affective economy in which violence played a dominant role, as it affectively bound people to not just one world but a multiplicity of worlds. In this context, prints can be analysed as affective commercial products that had a deep impact on the emotional practices and self-fashioning of early modern consumer audiences.

The prints showed all types of violence, from legitimate to illegitimate, from cruelly human to natural, from European to exotic. De Hooghe’s workshop alone produced more than 3,500 prints, of which an amazingly large proportion are extremely violent in nature (Reference NieropNierop, 2018), ranging from relatively small and detailed depictions to gigantic violent scenes. Print woodcuts, engravings and etchings for illustrated books, broadsheets, pamphlets and atlases were central to one of the key market spaces that provided the Dutch Republic and a much wider audience with an explosion of violent imagery. While Dutch paintings presented more peaceful scenes – landscapes, city scenes, still lifes, interiors, portraits – an impressive proportion of the Dutch print market concerned the visual staging of violence (Reference Michel vanDuijnen, 2019). Engravers and printing houses produced new modes of imagining atrocities, with depictions of public executions, sea battles, tales of martyrs, torture handbooks, battlefield scenes, horrifying Old Testament stories, exotic tyrannical ‘justice’, beheadings, rape, pillage, iconoclasm, furies, raids, shootings, stabbings, piracy, looting – in short, nearly every form of violence imaginable (Reference Michel vanDuijnen, 2018). Apparently, books like these were not meant to rationally reflect on the role and functions of different kinds of violence. Rather, all kinds of violence were brought together as a matter of fascination. Violence became a product that sold. Consequently, whereas in what follows different forms of violence will be addressed, we consider violence in the same way as it was sold: in all its variants.

The affective commercial product of Les Indes Orientales et Occidentales was carefully crafted and put into a narrative by de Hooghe and his publisher, Pieter van der Aa, both famous and skilled entrepreneurs at the peak of their careers (Reference HoftijzerHoftijzer, 1999; Reference NieropNierop, 2018). Both were deeply invested in bringing images of violence to the book market (Reference GottfriedGottfried, 1698). However, the impact of this violent imagery by far exceeded the intentions of their makers. The images had already travelled a long way – not only from the book of Simon de Vries to this book of prints but also from other print collections. De Hooghe’s print shop eagerly copied representations of the practices, rituals and riches of the world from older images and illustrated books (Reference SchmidtSchmidt, 2015). De Hooghe’s engravings became iconic themselves, informing other prints, frontispieces and broadsheets. His ethnographic prints, for instance, found their way into another impressive image enterprise: the Galerie agréable du monde. In this series of sixty-six volumes, Pieter van der Aa compiled around 3,000 plates from famous Dutch engravers for the ‘lovers’ – ‘liefhebbers’: amateurs – of history and geography (1725; cf. Reference PeatPeat, 2020). This collected graphic knowledge of the world and imaginative enterprise highlights the explosion of printed images which had started to flow into the European market over the course of the seventeenth century.

Capitalist Market and Affective Economy

De Hooghe’s case allows us to highlight two domains that will be of relevance throughout this Element: markets and affective economies. Dealing with the market of imaginations of violence, we will consider (calculable) material conditions of production, transport, trade, exploitation and consumption. Representations of violence can be compared to commodities such as sugar – one of the new products from the Americas that became a dominant mass commodity in Europe and which involved a new industry and system of production and trade (Reference AbbottAbbott, 2010).

In the concept of affective economy two terms come together that for a long time were studied separately: affect and economy. While economics and economic history traditionally disregarded emotions and embodiment (or talked about them to highlight how they interfered with rational economic processes), the more recent field of the history of emotions initially displayed little interest in matters of commerce (for introductions to the history of emotions, see Reference ReddyReddy, 2001; Reference Frevert and BuddeFrevert, 2011; Reference PlamperPlamper, 2015; Reference BroomhallBroomhall, 2016; Reference BoddiceBoddice, 2017). Historians of emotions hardly paid any attention to economic factors or to commercial actors using, influencing or producing emotions (Reference Bailey and BroomhallBailey, 2017).

Recent trends, however, show more interest in the intersections between emotions and economies. Studies describe the role of emotions in the origins of capitalism, the psychology of market behaviour and the cultural values, imaginations and moral issues which influence market behaviour (Reference SchleiferSchleifer, 2000; Reference McCloskeyMcCloskey, 2006, Reference McCloskey2016; Reference GoldgarGoldgar 2008; Reference YazdipourYazdipour, 2011; Reference FontaineFontaine, 2014; Reference MargócsyMargócsy, 2014; Reference Leemans and GoldgarLeemans & Goldgar, 2020). Sociology and cultural philosophy studies analyse emotional labour and the marketing of private life (Reference HochschildHochschild, 1983; Reference IllouzIllouz, 2007). In political theory, emotions are studied for their cognitive potential and their potential to create or split social bonds within political systems (Reference NussbaumNussbaum, 2013). If, in this context, we say the Dutch Republic witnessed the emergence of a capitalist market, this was, obviously, not the industrialised version of the nineteenth century. The Republic’s version of capitalism is characterised by the cycle of production and consumption and the materialisation of a mass market. The immense production of images did not answer to the demand from a mass audience; it called on that demand and made the mass audience possible. This form of capitalism did not serve the individual needs of consumers; it bound them to a market, which is precisely why recent studies have put forward the concepts of ‘emotional economies’ and ‘affective economies’ (Reference AhmedAhmed, 2004a; Reference Leemans and GoldgarLeemans & Goldgar, 2020).

The cultural theorist Sara Ahmed employs the concept of affective economies as an analytical tool to understand the workings of collective identities. Although she uses the words ‘emotion’ and ‘affect’ sometimes interchangeably, the term ‘affect’ seems more apt, as it underlines the fact that emotions do not work just on an individual level but are mediating, communicative tools, connected to expressions of feelings, which help to shape society. A ‘theory of emotion as economy’ may show that emotions work as a form of capital: ‘affect […] is produced only as an effect of its circulation’ (Reference AhmedAhmed, 2004b: 120). The role of the media was crucial in this context because they defined ‘how bodies and ideas become aligned with each other’ (Reference Lehmann, Roth, Schankweiler, Slaby and von ScheveLehman et al., 2019).

These recent studies interpret affective economies, however, mostly on an abstract level. Economic terms such as production, exchange and accumulation are mainly used metaphorically, describing psychological ‘emotional households’ and ‘moral economies’ balancing different emotions and accumulation value in terms of human capital (Reference Frevert and BuddeFrevert, 2011). We would rather steer the concept towards economics and sociology, where it is used to understand the workings of modern-day consumer societies and the emotional investment that capitalist societies require from their participants (Reference Casey and TaylorCasey & Taylor, 2015). If violence, as an issue of emotional investment, became a marketed product, how did creative producers tap into the affective imagination of projected consumers to ‘invent’ and stimulate their desires for horror and adventure? Can we map the emotional-commercial components of the affective market of imaginations of violence?

By choosing to work with the concept of ‘affective economies’ rather than ‘emotional economies’, we aim to highlight that we are interested not (only) in individual desires and responses but also in the embodiment (the sensorial aspects) and in the social and spatial aspects of commercial processes (Reference Trigg and BroomhallTrigg, 2016). The term ‘affect’ allows us to analyse, firstly, how image markets put the mind, the body and its sensations into different states. Watching violent scenes may cause the body to tremble with anxiety, shake with disgust or seriously lose control – for instance, by causing nausea. Accordingly, as early modern artists displayed bodily sensations through various media, they mediated affective relations that went beyond the confines of a ‘dialogue’. Producers and consumers together explored the body language of violence and the embodied sensations that violent imagery could bring.

Secondly, affect underlines the social, communicative, binding and splitting aspects of emotions (cf. Reference BroomhallBroomhall, 2016; Reference BoddiceBoddice, 2017). Emotions can act as emotives: they communicate, investigate and connect (Reference ReddyReddy, 2001). Once expressed, an emotion requests a response. ‘emotions do things, they align individuals with communities — or bodily space with social space — through the very intensity of their attachments’ (Reference AhmedAhmed, 2004b: 119). Thus, emotions can be at the basis of interest, in that they bring people into interrelation. Shared feelings can be a strong basis for shaping communities, just as they can split communities. The emotional communities of image markets are, as we will show, bound by interest – by the self-interest of the satisfaction of desires but also by the invested interest of shared experiences (see Section 3). Thirdly, and finally, affects are embodied, at work between bodies, and enacted through different media, in spaces such as theatres and anatomical theatres, in maps, on frontispieces, in public manifestations such as firework displays and so forth.

The Affective Economy of Images

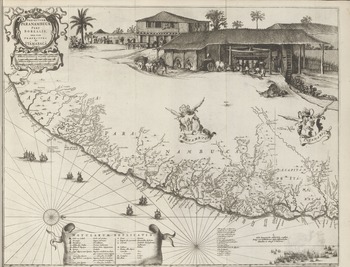

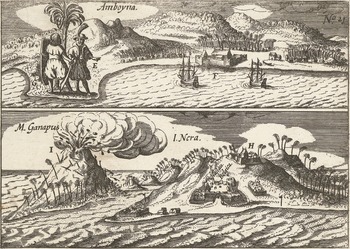

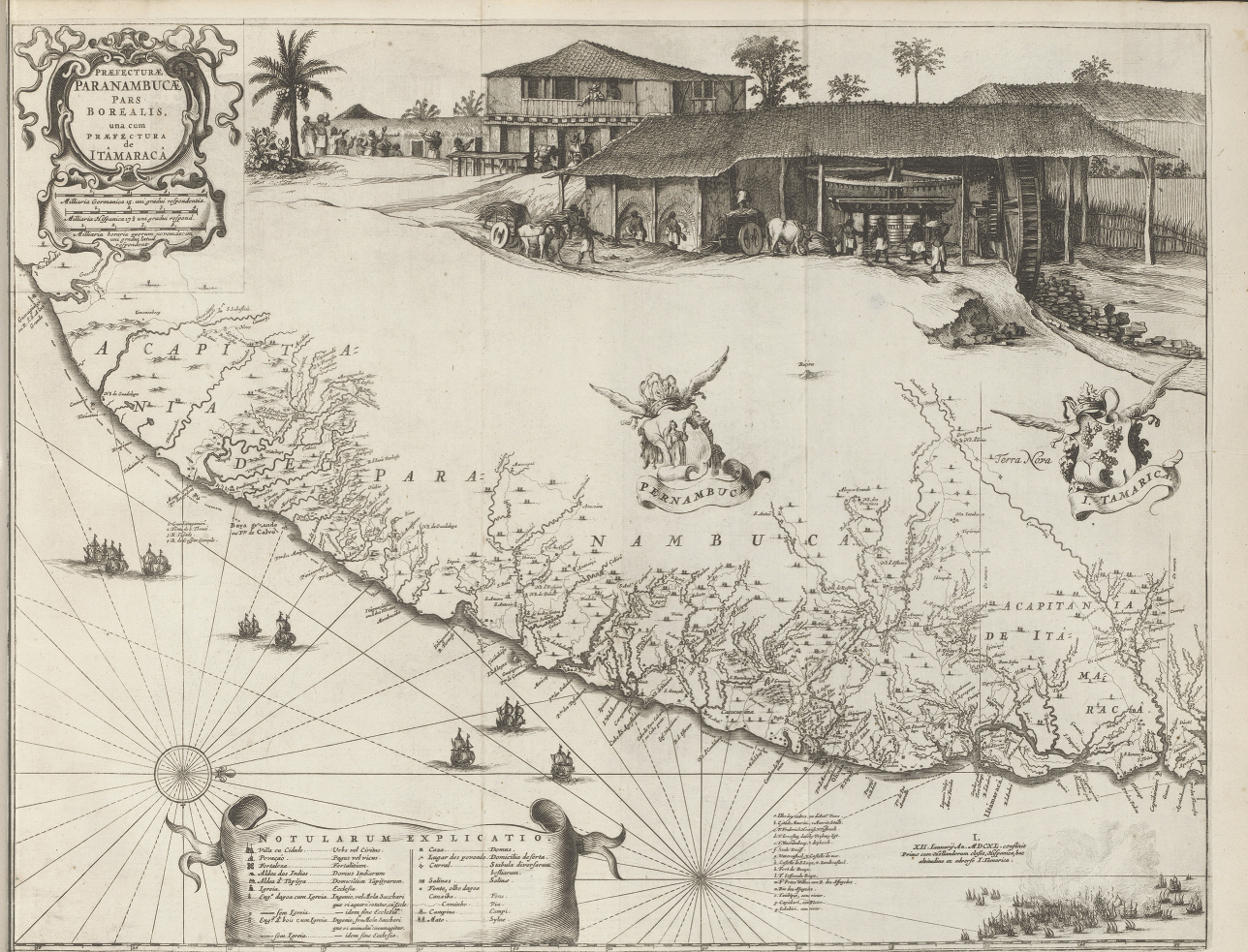

The map in Figure 3, from around 1647, shows Pernambuco, a region in northern Brazil which at the time was controlled by the Dutch West India Company. The map was created as part of a series of fifty-five maps and accounts of the travels of Count John Maurice of Nassau to Brazil in the years 1636–44. In terms of representation, it is hard to speak of one image. Rather, it is a set of different kinds of images with some explanatory text. To a general audience of consumers, the horrors connected with sugar production were consciously concealed to avoid spoiling the desires and pleasures connected with sugar. In the upper, empty part of the map, almost as a symbol of the idea of terra nullius that would legitimate colonial appropriation, a sugarcane mill is represented, with people working peacefully, and, in the left-hand corner, a social community is eating and playing.

Figure 3 Salomon Savery, Map of the Coast of Pernambuco (1645–7), in Caspar Barlaeus, Rerum per octennium in Brasilia (Amsterdam: Johannes Willemsz Blaeu, 1647).

Economically and ecologically speaking, sugar production involved a set of new lifeworlds, which took the shape of a plantation culture that affected all actors deeply and was not restricted to the Americas (Reference AbbottAbbott, 2010). Seventeenth-century Amsterdam, for instance, witnessed the growth of more than 100 sugar refineries that redefined urban space, changed technologies, attracted people and came with their own affective economy (Reference PoelwijkPoelwijk, 2003). The sugar industry produced new ‘bodies of interest’: connecting sweet-addicted consumers with the blood and sweat of the (enslaved) labourers in the Netherlands and overseas. The production, distribution and consumption of sugar were in turn connected to the production of a wide variety of (decorated) sugar pots and other imaginative sales products, with their own affective forces of appeal. The violence needed to produce sugar was conspicuously absent from such luxury commodities, which serves to show that affective economies can work with asymmetrical distributions. However, for some observers – Europeans who had helped to construct and oversee the plantations or former slaves and other black immigrants – the violence behind the seemingly peaceful scene might have been more visible or even painfully embodied. The working of affective economies depends on the perspectives of the participants.

In the case of the map of Pernambuco, violence is explicitly presented in a low-key manner in the lower right-hand corner, where a sea battle is depicted between Dutch and Spanish-Portuguese fleets close to the island of Itamaraca in January 1640. The battle was part of an expedition led by John Maurice (see Section 5) that would not only lead to the WIC’s conquering parts of Brazil but also provide a decisive impulse to the Dutch slave trade. Though the violence is explicitly thematised here, the aim and goal of the battle remain implicit again, or are a matter of epistemic violence, as when the territory of Indigenous people is suddenly captured by projections that follow the logic of compass roses, producing a map that represents northern Brazil as owned by European powers. In the context of affective economies, one question, then, is how the set of images, with a map of the region, a scene of a sea battle between the Dutch and the Spaniards and the depiction of a sugar plant, affected people at the time. Another question is how this entire set of images propelled a circulation of affects that was intrinsically connected to a much wider field of imageries.

If violence in itself became something that sells, or that was to be avoided for the sake of selling things, this was both a matter of markets and affective economies. Violent prints, like the ones we have dealt with so far, informed and were informed by paintings, maps, plays, coins and even luxury objects, such as porcelain cups (Reference JörgJörg, 1997; Reference DijkstraDijkstra, 2021). The prints also stood in dialogue with live performances, such as public festivals, firework displays, lotteries, fairs or public executions. That is, violent images circulated among a large variety of sectors, causing a situation where viewers could be confronted with, or would be seduced to seek, particular kinds of imagery again and again, imprinting the mind and body with certain forms, typologies and knowledges concerning violence. The circulating images were a matter of what we called, in a previously published article, ‘imagineering’ – on which more in Section 1.

Aim of This Element

One may ask, obviously, whether the market for, and marketing of, violent imagery was a new phenomenon. Have not humans been confronted with violent images for centuries? We contend that a fundamental shift took place in the early modern period, with the emergence of modern, capitalist economies, the commodification of images and the expansion and interconnection of different image industries and markets. These developments not only led to an explosion of images; they also caused shifts in the affective impact of images, on the individual level and on the level of societies at large. This shift merits scholarly attention, not least since it represents an essential stage in the development of our modern-day visually oriented societies.

In this Element, we aim to showcase what happened in the seventeenth century when images started to circulate widely as marketed products, in and between various sectors of society, connected with staged scenes and visual materials and driven by commercial impulses and marketing strategies. The staple market of images was analogous, here, to the staple market of all goods – or entrepôt market – as the cornerstone of the fast-expanding and globalising Dutch economy (Reference WallersteinWallerstein, [1980] 2011: 56). The more the Republic and its hub Amsterdam got involved in a wider European network of trade first and then a global one, the more voluminous and diverse this storage market became (Reference Jan de and Ad M. van derVries & Woude, 1997). The profitable bulk trades in grain and fish were followed by less bulky but very profitable ‘rich trades’, with spices and silk as paradigms. The Dutch East India Company (VOC) was a massive supplier in this context and sent 4,700 ships out to Asia between 1595 and 1795, with close to a million people involved (Reference LucassenLucassen, 2004). This staple market depended on high-volume storage (bulk), technologies (bigger ships that could be built more quickly, at lower cost and equipped by a smaller crew), information exchange, trading agents and means of distribution (Reference LesgerLesger, 2006; Reference Jan Luiten vanZanden, 2009).

Similar factors propelled the ‘staple markets of images’. Our question is what it did to people. What affective economy did these image markets develop? What media technologies and social techniques were used by producers to create desires, attracting readers and spectators and keeping them interested? Why did people invest in visual products and productions? How did images engineer specific impacts and mobilise embodied reactions? What profit or interest did they bring? We will show how images engineered not only individual responses but also collective forms of behaviour and how images tried to control the affects they aroused.

In the early modern period, the development of the print industry, the advancement of the art market and the market for luxury goods, as well as the commercialisation of other cultural sectors, such as theatres, resulted in the production of a swirl of images (Reference Haven, Frans-Willem and LeemansHaven et al., 2021). One dominant body of images was extremely violent in nature. As we will argue, it was through and in connection with this ‘spectacle of violence’ that new ways of looking and embodied experiences were introduced. As the public manifestation of violence by ruling powers became less dominant, violence could become a matter of private yet mass consumption as a commodity to be enjoyed. Readers could become addicted to scenes of horror and war or consume images to help understand humankind’s violent nature. Affective communities could develop around the collective consumption of violent images, rendering specific affective practices.

Marketing Violence will give the modern-day reader a sense of the wide spectrum of the early modern representation of violence by discussing various types of violence in a variety of cultural sectors, ranging from gigantic paintings of sea battles to bloody plays, peepshows presenting battlefields, anatomical atlases, prints of public beheadings, poems, maps and ethnographic prints of cruel customs – such as the frontispiece of The Marvelous History of Cannibals (1696) (Figure 4). This frontispiece is an example of remediation: different media are translated into one another. It is first of all a book’s frontispiece, with the publishing house named below. Secondly, the print is a visual equivalent of what will be described in the book. Thirdly, the cloth above suggests that the curtain has been raised to reveal a theatrical scene. Working together, the imagery brings violent histories to life. In this Element, we aim to analyse what kinds of violent images the different sectors of the early modern cultural market produced, explain how these different sectors intersected and show how images were constantly remediated.

Figure 4 Abramah Magyrus, De wonderlijke historie der mensche-eeters, verhandelende haren aart, oude woonplaatsen (Amsterdam: Jan ten Hoorn, 1696).

Our underlying thesis is that the seventeenth-century shift towards a commercial market of the imagination helped develop a new affective economy. We chose to analyse this phenomenon in the Dutch Republic as a paradigmatic case. The early modern Northern Netherlands offers an excellent example of both an economy that was capable of producing and consuming violent imageries and an affective economy of violent imagery. It was one of the first states to develop into a modern, capitalist economy, with a cultural market that served as a magazin de l’univers that produced and distributed maps, illustrated books, paintings, luxury objects and other imagery throughout European markets and beyond (Reference Jan de and Ad M. van derVries & Woude, 1997; Reference IsraelIsrael, 1998; Reference Jan Luiten vanZanden, 2009).

Although we see violence as just one possible example of the development of an affective economy based on the commercial production of imageries, we will also argue that the imagination of violence played an essential role in the forging of the Dutch Republic and its imperial, colonial programme. The stunning abundance of violent imagery that inundated Dutch markets in the course of the seventeenth century can be interpreted as an instrument of mediation between (1) the urgent commemoration of the violent past from which the Republic had matured; (2) the decline of explicit scenes of violence in the public sphere in most of the provinces; and (3) the advancement of an ideal of a moderate, peaceful, tolerant, commercial Republic that was at the same time (4) a military power at the centre of a new commercial empire.

Sections

Section 1 introduces the reader to the early modern staple market of images and will present the market strategies, media technologies and the social and affective techniques of early modern image production and consumption. Section 2 analyses desire as a driving force in the affective economy. The section focusses on a fundamental transformation in the early modern world from theatrical regimes closely coordinated by sovereign powers into a culture of spectacle, driven by commercial market mechanisms. Desire, in this context, is considered as a common affective drive that can be propelled and used by market actors. Section 3 follows this line of investigation but now with interest as a pivotal term. The section asks why people became so invested in scenes of violence. What interest was involved for producers, consumers and sociopolitical parties? Here, we investigate fireworks, peepshows, battlefield scenes, public uprisings and their remediation. Starting from personal profit-seeking and self-interest, we will discuss interest as an embodied force and as a social drive, which operate in gift economies and webs of investment.

Section 4 wonders how the affects were controlled. The issue is both how people were controlled by violence and how the vehement affects aroused by scenes of violence could be made productive. We will discuss different agents of enactment and control of violence, ranging from the markets in general to specific stock markets, or from stadtholders to burgomasters, and all somehow connected to a powerful and familiar source of both excessive violence and control: divine violence. The underlying thesis is that both governmental and civil market control came to be more and more connected to people’s self-control, which implied controlling the passions. Among other media, the section investigates cartoons and poems. Section 5 brings us back to the question as to why the Dutch Republic was so involved in depicting and staging violence. Through a discussion of atlases, illustrated ethnographies, architectural façades, depictions of sea battles and scenes of slavery, we will show the inherent tension underlying the Dutch political and imperial project. On the one hand, it flaunted its strength and colonial might through visual power plays, while, on the other hand, it tried to avoid explicit references to violence inflicted on humans and nature or tried to push this to the margins. Exploitation thus incorporated the interplay between pride and unease.

Finally, we present a conclusion on what we call ‘the affective loop’. Desires, anxieties, fears and hopes drove markets, just as much as these emotions and affects were driven by the market. Here, we propose an integrated approach to affects and emotions, not isolating them to the domain of the psyche, the body, the private, the collective or any one of the domains of life. As the seventeenth-century Dutch marketing of violence shows, affects run throughout, or connect, the whole gambit of societies and lifeworlds.

1 Engineering Images: Commercial Remediations of Violence

Selling Violence: An Entrepôt of Images

The production of images, whether in visual or rhetorical imaginations, provided the Amsterdam entrepôt market of goods with an equivalent in a staple market of images, with traders getting them in, producing them, storing them, selling them and distributing them in relation to the demands of the market and the day (Reference MontiasMontias, 2002; Reference De Marchi and MiegroetMarchi & Miegroet, 2006). Over the course of the seventeenth century, the Dutch Republic developed into a cultural hub for the Republic of Letters and established itself as le magazin de l’univers – ‘the bookshop of the world’. It is estimated that Dutch printing houses published more than 350,000 editions (Reference Pettegree and Der WeduwenPettegree & Der Weduwen, 2018).

The Dutch knowledge economy, perceived as the first knowledge economy of Europe, filled the European book market with printed texts, propelled by an advanced creative industry of printers, artists, engravers and map-makers (Reference Jan Luiten vanZanden, 2009; Reference Kolfin and VeenKolfin & Veen, 2011; Reference HaksHaks, 2013; Reference RasterhoffRasterhoff, 2017). During the seventeenth century, the Calvinist-dominated Republic slackened its religious hesitance towards images. It is estimated that a total of no fewer than 5 million paintings were produced in the Golden Age Dutch Republic. Most Dutch households had paintings or other kinds of imagery hanging on their walls (Reference MontiasMontias, 1982; Reference BokBok, 1994; Reference Loughman and MontiasLoughman & Montias, 2000). The Dutch book market embraced the visual, printing illustrated Bibles and providing all kinds of illustrated books to an apparently profitable market (Reference StronksStronks, 2011). Images were everywhere.

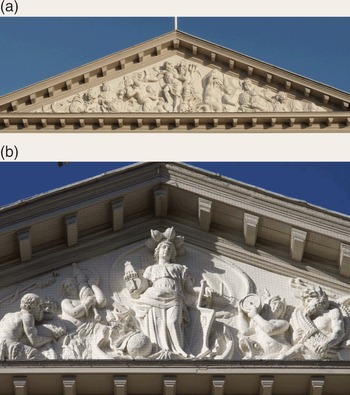

These images – prints but also architecture and decorations – proudly presented the Dutch Republic’s powerful place in the world (Reference Bussels, Eck and OostveldtBussels, Eck & Oostveldt, 2021; Reference SchamaSchama, 1988; Reference IsraelIsrael, 1998; Reference PrakPrak, 2005). One telling example is the majestical Amsterdam Maritime Warehouse of the Admiralty, built in 1655–6. The visual theme of the façades of this building, attributed to Artus Quellinus, is Janus-faced. One tympanum entitled ‘Zeevaart’ (shipping) is oriented towards the sea, and the tympanum ‘Zeebewind’ (sea rule) is oriented towards land (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Tympanums of the Amsterdam Maritime Warehouse: (a) ‘Zeevaart’ oriented towards the sea; (b) ‘Zeebewind’ oriented towards land. Pictures: Klaas Schoof.

‘Zeevaart’ shows an allegorical representation of Holland’s maritime endeavour. A water nymph, the symbol of the city of Amsterdam, begs Neptune to bring her the treasures of the sea – and they are brought, almost naturally, although all packaged. Here, the representation of violence is absent. ‘Zeebewind’, however, expresses the ruling authority of the Admiralty, symbolised by a woman wearing a crown of ships and standing on a shell that is safely anchored while being served by sailors who carry a flag, a sword, a cannon, a gun carriage and gunpowder. The two frontispieces taken together were an explicit illustration of how a commercial centre, the hub of an impressive fleet of commercial ships that sailed the seven seas, was at the same time a centre of military power. The Republic had a fleet, consisting of different building blocks but united under one flag and capable of defending itself and the commercial bodies under its protection. It was also eager to attack others to open up new markets. The tympana thus proudly present a net of commerce and violent power.

Poets such as Antonides van der Goes and Joost van den Vondel explained how the Maritime Warehouse and its frontispieces should be read. Their texts added new images to what the frontispieces already showed. Vondel’s eulogy, for instance, depicts the function of Dutch maritime power as follows:

As can be seen, image is added upon image in a logically arranged association of forms of violence connoting defence and attack that ground the Republic’s use of violence in the law of nature. Nature is there from the start, with the foam of the sea. Yet the foam shifts into foam caused by a fleet of warships that comes rushing in, carrying the spoils of war. To play down the possible aggression inherent in this image, Vondel immediately adds that violence is natural when caused by the Dutch nood: ‘need’, ‘distress’, ‘want’ and ‘necessity’. To safeguard beings against need, divine providence has equipped all natural beings, including all flora, with forms of protection. Such forms of protection easily become forms of attack, when necessary. A snake can use its deadly poison, and a lion will first protect its cubs by hiding them but will use its deadly claws and formidable teeth when pushed.

The image of the lion is a dominant one: the lion was the symbol of the province of Holland and in general for the new Dutch Republic (Figure 6). As this image makes clear, the lion was partly a symbol that could ground the use of violence in natural law. At the same time, the sword carried by this lion and its inscription ‘Patriae dei’ indicate that the newly installed Republic had divine support and was well equipped with instruments of war.

Figure 6 Claes Jansz. Visscher, Comitatus Hollandiæ denuo forma Leonis (1648).

Although the rise of a vibrant visual culture in the Dutch Republic has been studied previously, few studies have examined the imagery of violence separately, and few studies have researched the technologies employed across different media with the aim of understanding the affective impact of these webs of images on early modern audiences. Two characteristics of the new cultural industries and markets were their capacity to innovate technologically and to remediate the material at hand, constantly renewing topics, themes and motives by rearranging them, redesigning them, translating them to other media or bringing them up to date according to new quality standards (Reference DavidsDavids, 2008). One theme that is especially apt to illustrate this was the recycling of the visual representation of so-called tyrannieën, or furies, such as the Spanish fury – whether in the Southern Netherlands or in the Americas – the Turkish fury or the French fury (followed in the eighteenth century by the English fury). These furies formed a counterpoint to the image of the noble but forceful lion in that they could not be captured metaphorically by one image but instead by a multiplicity of images.

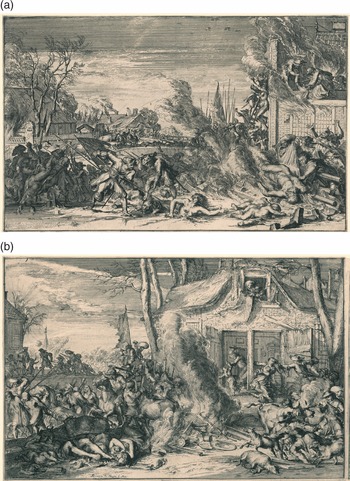

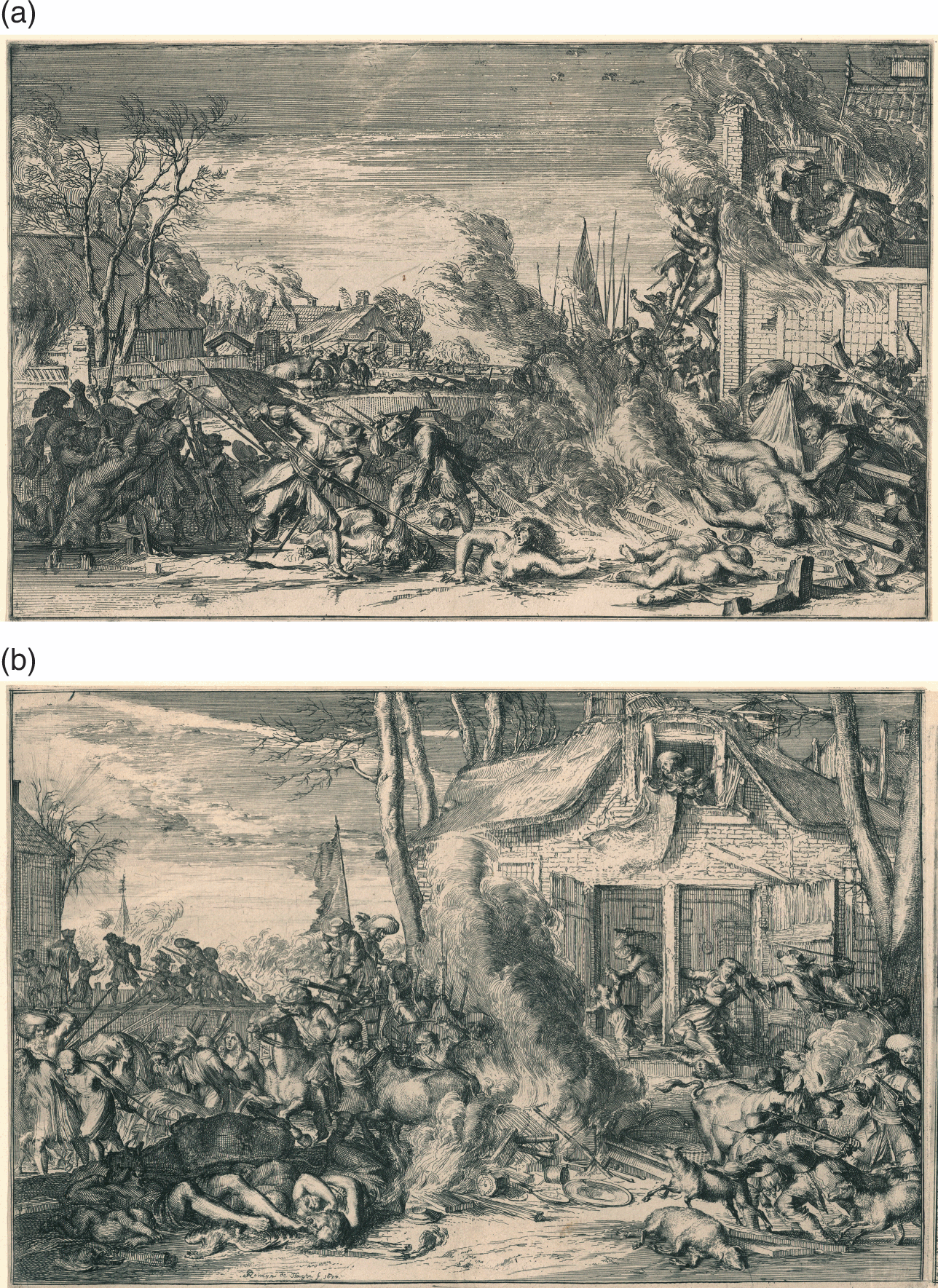

Images, Media and Remediation: Recycling Furies

In 1672, the Republic experienced a decisive moment in its history when England and France shortly after one another (and in close consultation) declared war. Whereas the war with the English was mainly a matter of sea battles, German and French troops almost effortlessly invaded the provinces – though in the course of no more than a year the Dutch water defences exhausted them and they were forced to retreat (Reference Hale, Gosman and KoopmansHale, 2007; Reference ReindersReinders, 2010; Reference Prud’homme van ReinePrud’homme van Reine, 2013). In several instances, atrocities occurred that were instantly thematised and marketed. For instance, the atelier of Romeyn de Hooghe started to put out broadsheets which covered the news events in changing combinations of scaffold scenes, crowd action, tableaux vivants, portraits and texts. Figure 7 shows two such prints, which were part of a series entitled French Tyranny in Dutch Villages. The scenes present a catalogue of atrocities inflicted on Dutch men, women, children and livestock, and on their lifeless bodies, as part of the devastation of wealth and property. The images are constructed in such a way that the viewer’s eyes cannot rest but are drawn from horror to horror.

Figure 7 Romeyn de Hooghe, (a) French Tyranny in a Dutch Village (1672). Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, RP-P-OB-77.197; (b) French Tyranny in a Dutch Village (1672).

Not only did de Hooghe ‘staple’ violent images within one broadsheet, in the context of the series of cruelties, almost all his prints were also copied frantically, transformed and reprinted. This was often done anonymously by publishers profiting from the fame of the master of violent images but also by famous artists such as Jan Luyken and Bernard Picart. These violent scenes remained popular, moreover, until the end of the eighteenth century. People could buy the series of prints, separate scenes taken from them or other combinations with or without textual explanations.

While being innovative both technologically and artistically, these prints by de Hooghe were the product of a longer tradition of prints depicting cruelty which were entangled with the coming of age of the young Dutch Republic. For instance, in 1633 a set of eighteen etchings was published under the title Les grandes misères et malheurs de la guerre, or The Great Miseries and Misfortunes of War (Figure 8). This work by Jacques Callot is commonly considered a first powerful statement in the history of European art against the atrocities of war, comparable to Goya’s pieces on the issue in the early nineteenth century. Callot’s images started to travel through Europe in different versions. One set was republished in Amsterdam somewhere between 1677 and 1690 under the title The Sad Miseries of War: Very Nicely and Craftily Depicted by Jacques Callot (Reference SchenkSchenk, 1670–90).

Figure 8 Jacques Callot, Les grandes misères et malheurs de la guerre (1633).

The considerable number of studies of these etchings pay almost no attention to the differing status and power of the printing press between 1633 and 1690 (Reference Goldfarb, Goldfarb and WolfGoldfarb, 1990). Yet, although the set published at the end of the century was the same as the one from 1633, it was defined by a radically different cultural and political infrastructure, with different affective implications. The more general problems of atrocities of war had become more specific because the Republic had been invaded by French forces. As a consequence, Callot’s etchings were taken up intertextually in new sets of images, such as de Hooghe’s depictions of the French Tyranny in Dutch Villages (1672), thus recycling the theme of furies.

Growing out of the revolt against Spanish rule, the Republic had put violent prints to good use, enticing anger about Spanish ‘tyranny’ and its cruel furies, creating support and enthusiasm for the revolt and, later on, imprinting these historical atrocities on the minds of later generations (Reference BaudartiusBaudartius, 1610). The continuity and shifts in the tradition of atrocity propaganda in Dutch popular print and the repetitive character of scenes of atrocities have been described and catalogued (Reference Cilleßen and VogelCilleßen, 2006; Reference Michel vanDuijnen, 2020). From the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre, via the Spanish tyranny and the ‘black legend’, to the French fury, we find comparable depictions of plundering, stabbing, shooting, the slaughter of women and children in the marketplace, rape, the cutting up of female bodies, hanging, men being thrown out of windows, burning, ransacking houses, destroying property and the piling up of bodies. The function of these images resided partly in their informative quality, distributing news about the war. They had persuasive influence – for instance, to keep the provinces involved in military campaigns. And they could function as instruments for memorialisation politics, as when they had a role in the development of a national myth in which the free and tolerant Calvinist Dutch Republic was counterpoised against ‘black legend’ Catholic Spain (Reference NieropNierop, 2009; Reference PollmannPollmann, 2017; Reference Kuijpers and van LieburgKuijpers, 2018).

On a more general level, the images also appear to have explored violence as a concept, presenting inventories of cruelty and analysing violence as a cultural phenomenon. In the second half of the seventeenth century the violent narratives became more intimate and personal, shifting away from scenes of mass executions, bird’s-eye views and cartoon-style pamphlets with multiple scenes towards depictions of more isolated moments of violence, zooming in on the affects aroused in the participants (Reference Michel vanDuijnen, 2019). Such images were produced by, and for, a market. Both the repetition of and the variation between images indicate an advanced cultural market, where any possible saturation of the market was met with diversification. By the middle of the seventeenth century, the Dutch book-and-print market seems to have reached its peak in terms of producers and production, offering cultural products and luxury goods that were almost endlessly varied (Reference RasterhoffRasterhoff, 2017). We can analyse this in terms of ‘familiar surprises’: products that combine familiarity and comfort with novelty and thrill, and can therefore both cater to known publics as well as specify new target groups (Reference Hutter, Beckert and AspersHutter, 2011: 204; Reference Rasterhoff, Beelen, Leemans and GoldgarRasterhoff & Beelen, 2020). Repetition and variation thus sustained the image market.

The repetition and variation were often also a matter of remediation. Remediation takes place when images are taken up, or repeated, through other media, with each new medium incorporating contents and forms of previous media (Reference Bolter and GrusinBolter & Grusin, 2000). For instance, prints in books often followed a theatrical logic in how the scene was represented. Callot’s scene presented in Figure 8 followed the characteristics of a tableau vivant, as it was staged in theatres. Images from one medium could be translated to another medium, then. For instance, when in 1672 the republican leaders of the Republic, the De Witt brothers, were slaughtered, their capture, killing and lynching were depicted through prints and paintings. The prints travelled through different media, including books, booklets and broadsheets. Coins, yet another medium, were minted following a design based on the printed images, while other coins later appeared in print. Repetition and remediation led to a multitude of visual and textual stagings of the event, allowing the public to relive and absorb it from every possible angle and perspective by reading about, watching and, in the case of coins, touching it. Such remediation could facilitate so-called hypermediacy – that is, a reflective awareness of the medium or media used (Reference Bolter and GrusinBolter & Grusin, 2000: 11–14). For instance, the Callot print’s use of a theatrical frame may have led the audience to reflect on the image as if staged and theatrical.

The seventeenth century witnessed the development of an extensive, transnational, commercial and representational infrastructure of images in different media. This infrastructure involved technologies that, although developed for one medium, could easily be adopted by others, such as when paintings were turned into engravings, prints formed the basis of tableaux vivants or the logic of the theatre was transformed into portable miniature theatres by travelling showmen. This led to different balances between forms of immediacy and hypermediacy. How did this material and representational infrastructure of images come to affectively redefine the way in which subjects understood and felt themselves to be actors in the world?

Constructing Selves and the Articulation of the Real

All the diverse technologies of representation that shaped consumers’ affective intertwinement with images were connected to specific agents: printers, engravers, machine builders, shop owners, consumers. Yet their actions taken together were a matter of what we called elsewhere imagineering – a present participle that is a contraction of imagining and engineering (Reference Haven, Frans-Willem and LeemansHaven et al., 2021). In the first instance, the term ‘imagineering’ was coined in the domains of urban studies and the creative industries, albeit with different meanings. The origin of the term can be traced back to an advertisement from 1942 by Alcoa, The Aluminum Company of America, in Time Magazine, which states: ‘Imagineering is letting your imagination soar, and then engineering it down to earth’ (Reference SailerSailer, 1957; see also Reference SuitnerSuitner, 2015). In this context, imaging came to be defined as a strategic use of images to represent urban environments, whereas imagineering indicated a process in urban development ‘where discursive meaning-making functions as a legitimation and stabilization of certain material practices in planning’ (Reference SuitnerSuitner, 2015: 98). In other words, in the fields of urban studies, theme parks and game design, the term refers to the translation of imaginary representations of an environment into material reality.

Yet another form of imagineering is at work when people talk about ‘Disney imagineers’ (Reference BestBest, 2010: 196). The latter term was not chosen at random: the research and development branch of the Walt Disney Company, which designs and creates its theme parks and attractions, is called ‘Imagineering’, which is why Disney has trademarked the use of the term – which is also why the publisher asked us not to use the term in the title of this Element and as a main concept. In relation to Disney, one definition of imagineering was: ‘The conscious creation of places with characteristics similar to other places (as in Disneyland). Often seen as the creation of a superficial veneer or façade of culture’ (Reference Knox and PinchKnox & Pinch, 2010: 328). The terms used in this quote, ‘superficial’ and ‘veneer’, suggest that imagineering is considered the postmodern counterpart, here, of the lucidity, or the materially ‘real stuff’, of modernist architecture.

Central to our study is a baroque kind of image production. In the context of the early modern entrepôt market of images, the material production of images constituted collective forms of imagination that worked as a cultural technique producing distinct historical selves. This is not only a matter of engineering imaginations into materiality (prints, paintings, plays, staged spectacles); it is also a powerful cultural technique that defines how people find themselves affectively embodied in the world. The aspects of this cultural technique are:

a set of formal technologies, such as those of painting, etching and printing or making theatre, spectacular shows and so on that allow for different forms of mediation and remediation;

a set of market strategies, which allow for a complex interaction between producers, consumers, cultural agents and media; and

both individually customised and collective techniques, aimed at serving but also construing individual and collective selves. That is, readers or viewers were taking in circulating images that, in turn, had an influence on how they found themselves in the world.

Just as the early modern commercial market in goods was possible only due to new technologies – for instance, in shipbuilding and wind-driven woodcutting – the market for images depended on technological and aesthetic innovations. If Dutch printers produced more extensive and expensive atlases, for instance, these were based on new technologies in printing, cartography, engraving, binding and so forth. Likewise, the realisation of the first Amsterdam theatre concerned not just the construction of a building but a building that facilitated new technologies of representation. In turn, these functioned as cultural techniques producing historical selves (Reference Yannice DeBruyn, 2021).

The scale of the cultural industry that materialised in the course of the seventeenth century gave rise to a form of power that depended on this distinct form of engineering images – not just sets of them but entire networks of them – that came to form a major aspect of cultural life and daily reality. In this context, prints were not just to be looked at, although this was part of the experience. Rather than constituting mere objects for viewing, they invited forms of dramatic re-enactment. We describe this historical shift, in which new technologies were deployed to make images speak to the public and to one another, thereby technically construing specific forms of individual and collective selves. Images formed an entire infrastructure by means of which people were staging themselves but that also encircled them: a network of images and imaginations that defined their world.

Affectively speaking, the process resulted in a new kind of self, similar to Greenblatt’s ground-breaking study on the technical construction of the early modern self: Renaissance Self-Fashioning (1980). In scholarly usage, self-fashioning sometimes became a term that indicated the conscious self-presentation of players in a cultural market, as if this self were some sort of Homo economicus. Yet Greenblatt’s point was that human selves are fundamentally made in a complex and dynamic field of practices and discourses (Reference Pieters and PietersPieters, 1999; Reference Pieters and RogiestPieters & Rogiest, 2009). No single subject was, ultimately, in control of or even steering what was happening. This is captured by the term imagineering as we used it elsewhere: a verb without a subject. Or, as will become clear in the sections that follow, images could be cut loose from the directive control of political powers through a commercial image market that constantly sought new connections with the institutions of power, aligning itself with regional, national, religious, commercial, republican, royal, private or imperial political programmes and ideologies. Through the print industry, a new visual domain had come to life that manifested itself not only in public space but also in the privacy of homes. Both in the public domain and in the privacy of homes, viewers found themselves taken up in a swirl of images, developing a desire to tap into this experience again and again.

As a present participle that can be turned into a continuous tense, image engineering emphasises that it was continuously at work, both externally and internally, in what people saw publicly and what they saw privately, in terms of the machineries that propelled such imaginations and in terms of how people came to behave as a consequence of them. In this context, the making, reproduction and consumption of images were not about reality – or not only, in any case. They rather articulated the real (Reference SiegertSiegert, 2015). The cultural techniques used were aimed at involving onlookers in a more sustained, embodied way, inviting them to enjoy private pleasures or anxieties, which in turn would allow them to be ‘taken up’ into the reality depicted.

Violence and Its Affordances

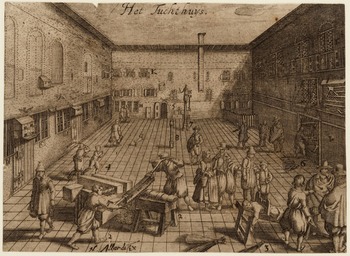

The print shown in Figure 9 represents a Kinder-spel or children’s game. It appears to depict a public, festive manifestation of children playing in the centre of The Hague, the political centre of the Dutch Republic. The print was made and published in 1625 and was part of a set of images that were set alongside the educational poems written by Jacob Cats.

Figure 9 Adriaen van de Venne, Children’s Games, in Jacob Cats, Houwelyck (Middelburg, Wed. Jan Pietersz. van de Venne, 1625).

It may seem a coincidence that, among the many games the children are seen to be engaged in, they are surely also mimicking a military company that marches across the square to the rhythm of a drum. They do so, moreover, underneath one kite flying above them and one falling because its string has been cut. As innocent as the image may appear, the poem underneath the image sheds a different light. Witness its first stanza:

In explaining the image, the text again adds new images. Apparently, the kite string is not only the power that holds the kite up against the wind; it is also the power that ensures that it remains in the air. When the string breaks, the kite floats down and changes from ‘wondrous beast’ into nothing but ‘dirty paper’ (Reference Johannes and LeemansJohannes & Leemans, 2020).

Read emblematically, the lines appear to say that he who strives for vanities loses the connection to grounding moral principles and is bound for disaster. The second stanza makes something else explicit, however:

Here, the ambitious, vain man is someone who failed to realise that the prop or pillar of his position does not consist of his own ambition but exists by the grace of the prince. It now becomes telling that the children are playing in The Hague, in the Lange Voorhout, with the house of Johan van Oldenbarnevelt on the left at the back, one of the most important political actors of the young Republic, who had been beheaded just around the corner in 1619, after a show trial set up by stadtholder Maurice of Orange-Nassau. Image and text taken together reflect on the nasty fate of a powerful political actor who had lost the sympathy of the prince. In both the first and the second stanzas, he has turned from being a respected actor into someone who is mocked, from someone who filled the headlines to someone who was trampled on, like filthy paper. Two different domains of the imagination are combined, then: one explicit and upfront, another one implicit; and both connect this print and the text to sets of other images.

The play between the explicit and the implicit will be a recurring theme. For instance, the young Republic was often represented as a tolerant and fragile new state, reluctant to engage in violent action, while at the same time it was a rather aggressive global actor that was quite capable of using violence (see Section 5). One metaphor that aimed to define the young commercial nation was that of the cat: shy and prudent and only violent when attacked by more aggressive animals. The inventor of the metaphor-image, Pieter de la Court, responded to Machiavelli’s famous distinction between two modes of exercising power: that of the lion and the fox. In Interest van Holland: ofte gronden van Holland’s Welvaren, de la Court reconsidered the proverb that a defensive war is one that consumes the one engaging in it. He argued that this proverb was wrong: to him, defensive wars were the only legitimate ones. Yet, with his metaphor of the Dutch Republic as a cat, he again introduced an ambiguous or double set of images that combined the image of a cat shying away with one that would fly at your throat if necessary. So, through the Dutch image market, the young Republic was represented and performed as both a peaceful, joyful entity and a violent one.

The market of images helped to glorify Dutch imperial and military power and helped create a sensorial regime in which customers, readers and viewers could attune themselves affectively to a world of violence and enjoyment and be taken up in embodied emotions such as fear, anger, disgust, hate, horror, glory, lust and pride. Focussing on violence, we aim to make clear that this was not just a theme with legal, moral, religious, political or societal implications. Violence offered chances, or it embodied a set of affective affordances. It could be worked smartly by downplaying overly nasty aspects of Dutch violence and suggestively emphasising the violence of others. It offered forms of violence that could be studied in more detail and more depth; to be explored with a wider overview through multiple events; to be combined in a field of associations, with the one shifting into another; to be produced, sold and consumed as a matter of profit and aesthetic experience. The next section will study this dynamic as an instance of desires propelled by distinct economic factors and constituting affective economies.

2 Desire: From Theatrical Accumulation to Deep Spectacle

Desire can be seen as one of the main driving forces behind the affective economy of the commercial Dutch Republic. Entrepreneurs and entertainers increasingly understood the art of triggering desire. Theatres were developing new techniques, raising a new generation of consumers, who, through the consumption of spectacle, came to look for more intense, collective and individualised experiences. Conceptually speaking, desire was elaborately discussed by philosophers such as Spinoza, who in his Ethics associated desire primarily with the idea of self-preservation. Desire, for Spinoza, was a specific form of ‘appetite’. Whereas appetite defined all bodies as striving bodies, desire was the human awareness of this appetite. The new culture of consumerism tapped into this new self-awareness, as it tried to capture and reshape people’s appetites and desires, inviting consumers to understand themselves as desiring individuals.

In this section, we will demonstrate, through the specific case of the Amsterdam Schouwburg, how theatre sought to arouse in the spectator the desire to experience representations as if for real, using violence to create immersive experiences. Throughout the seventeenth century, the theatrical representation of violence became more and more a matter of commercially produced desire. And for this, the theatre – the building itself but also the technologies present in the building – would have to evolve to remain an attractive player in the rapidly growing market of cultural representations.

Theatre As a Cultural Technique

In his preface to Medea, the author Jan Vos, the director of the Amsterdam theatre from 1647 to 1667, defended the omnipresence of violence in his tragedies, emphasising at the same time the importance of the credible depiction of violence. In doing so, Vos questioned the Aristotelian poetical paradigm and explicitly presented Seneca as his poetic reference to legitimise his predilection for theatrical horror. The requirement of ‘probability’ – a central concept of Horace’s laws of drama – is historically determined, according to Vos. When he reflects on how Seneca made Medea slaughter her children on stage, Vos contends:

That Horace could not believe that this imitation could be depicted on stage so vividly as it had happened, is no wonder: of old the Romans […] were used to seeing in their theatres lions, tigers and bears tear apart people, so that the torn intestines, still half alive and dripping with blood, poured out from the murderous wounds on stomach and chest. This made them so cruel at heart, that everything they saw presented otherwise was not believed by them, and therefore hated. So he wrote his laws not for us, but for the Roman playwrights, for I believe that the representation of people being murdered, if shown intensely, can move the feelings of the people by seeing it.

A Roman audience, Vos appears to say, had already seen all forms of horror in the gladiator fights, so the same horror on stage could only be laughable. The Amsterdam audience, on the other hand, is not hampered by this habituation and can therefore be effectively and fully moved by theatrical horror. The depiction of violence in the theatre is thus especially effective in a society where physical violence is regulated by an administrative system of trial and punishment in which new commercial opportunities arise for spectacular representations of violence. Such great commercial successes were achieved by plays with murders, duels or battles. The Spanish theatre in particular suited the taste of the public of the time. Spanish tragedy offered love, honour, revenge, disguises and so on, or more generally ‘turmoil’ (woelingen), the turmoil of the passions but also of the drama itself, with changing identities and plot twists. Yet the theatrical capability to capture the attention of audiences was more than a matter of twists and turns in the plot. It was also a matter of what the theatre was technically capable of.

In 1667, the playwright and theatre director Jan Vos opened the renovated Amsterdam theatre, a théâtre à l’italienne. Vos’s Medea aimed to demonstrate the new possibilities of the theatre, effectively putting his spectacular ambitions into practice. Juxtaposition and accumulation had been the basic dramaturgical principles in the first half of the seventeenth century, when spectacular, violent moments were shown ‘horizontally’ next to one another, often even within the same period of time. Yet, as the century progressed, the emphasis emphatically shifted to a ‘vertical’ experience, or an experience in terms of a depth that drew the spectator into the fictional world. With the new theatre it became possible to ‘work magic’. The viewing regime within which violence was shown had moved from a horizontal, accumulative theatricality to a more immersive form of spectacle that used depth (Reference Yannice DeBruyn, 2021).

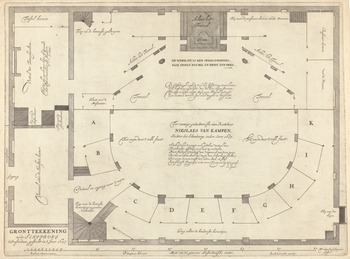

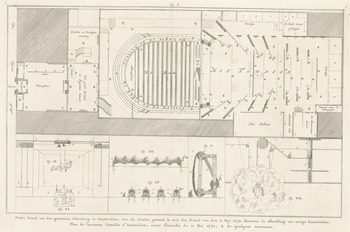

The first Amsterdam theatre, which had opened in December 1637 with Vondel’s Gijsbrecht van Aemstel, was rebuilt in the second half of the same century. It opened again in 1665 and offers a well-documented and paradigmatic example of a cultural transformation (Reference HummelenHummelen, 1967; Reference AlbachAlbach, 1977a, Reference Albach1977b; Reference ErensteinErenstein, 1996; Reference Porteman and Smits-VeldtPorteman & Smits-Velt, 2008; Reference Eversmann, Bloemendal, Eversman and StrietmanEversmann, 2013). We have five extensively studied images available for the first theatre: a 1658 engraving of the floor plan by Willem van der Laegh; two 1653 engravings by Salomon Savery, showing the view of the stage and the auditorium; a painting by Hans Jurriaensz van Baden, also from 1653, showing the stage from the side of the auditorium during a performance; and, finally, the painting The Triumph of Folly: Brutus in the Guise of a Fool before King Tarquinius (1643) by Pieter Jansz Quast (Figure 10).

Figure 10 Pieter Quast, The Triumph of Folly: Brutus in the Guise of a Fool before King Tarquinius (1643).

Quast based his depiction of the scene on P. C. Hooft’s description of a series of tableaux vivants presented on 5 May 1609 on the occasion of the Twelve-Year Truce, which together tell the story of Brutus’s revolt after the rape and suicide of Lucretia (Reference KorstenKorsten, 2017: 181). The work demonstrates concisely how horizontal theatricality functioned in the early seventeenth century: the tableau brings together, at a standstill, various scenes from the course of action and allows the spectator to navigate, as it were, through the story with his gaze. The protagonist in the middle looks at the spectator and thus breaks through the illusion or the fourth wall: he makes the spectator aware of the theatrical construction (Reference KorstenKorsten, 2017: 182).

This first theatre, designed by Jacob van Campen, was, from the perspective of European theatre history, a unique building that brought together different cultural influences and theatrical traditions. Further on in this section we will see how this same infrastructure, however, very quickly reached its own limits. In terms of technical capacity, it responded less and less to the needs of the early modern culture of spectacle. Jan Vos, among others, experienced these limitations at first hand. The rebuilding and furnishing of the theatre by Philip Vingboons in 1665 was a response to a cultural and economic development that had already been going on for some time. From that moment on, Amsterdam had a fully fledged spectacle machine at its disposal. This machine offered new possibilities for responding more efficiently to the spectators’ desires or, more so, for producing these desires and then exploiting them commercially. The omnipresence of violent representations in the theatre of that period (though violence is not the only spectacular effect exploited) and the horror they initiated are an integral part of this growing affective economy, with the desire for spectacle as one of the driving forces.

Accumulation and Juxtaposition

In 1648, the year of the Peace of Münster, the Spanish tragi-comedy De beklaagelycke dwang (The Pitiful Coercion) had its premiere, a translation and adaptation of La fuerza lastimosa by the Spanish author Félix Lope de Vega (Reference VegaVega, 1648). The actor and playwright Isaac Vos was responsible for the adaptation, which was based on an intermediate prose translation by Jacob Barocas. De beklaagelycke dwang was to become one of the big successes of the Amsterdam theatre. It was a typical Spanish baroque play: complicated love intrigues, betrayals and misunderstandings, cross-dressing, changes of location, jumps in time, ruses and violence continually postponed, including executions only just averted and a duel as the dramatic climax of a complicated story built on false accusations and a multitude of actions and passions. The many plot twists that succeeded each other in a play such as De beklaagelycke dwang connected seamlessly with the ‘changes of state’ (staatveranderingen) of the characters: they were hurled from one frame of mind to another, from one emotion to another, from one social status to another ‘like a rudderless ship at sea’ (Reference Blom and MarionBlom & Marion, 2021: 29). In short, this is a play full of ‘turmoil’ (woelingen). With the constant changes in time and space, the authors not only capitalised on the public’s desire to be constantly surprised; the narrative instability inherent in these plays perfectly symbolises the instability of the baroque world view.

In his preface, Isaac Vos emphasises that the play is in keeping with the spirit of the age: ‘it seems to me […] incongruous, in the rhyming of plays for the present time, to pay attention to the past; now that the eye, as well as the ears, wants to have a share in what is shown to it’ (Reference Blom and MarionBlom & Marion, 2021: 29). The adaptation by Vos is a telling example of the ‘hispanisation’ of the Dutch stage from the 1640s onwards. Indeed, recent research describes how important authors such as Lope de Vega and Pedro Calderon de la Barca were for the Amsterdam theatre (Reference Blom and MarionBlom & Marion, 2021: 67). For the first period of the theatre, between 1638 and 1672, Blom and van Marion count 43 Spanish plays in the repertoire, often quite spectacular and violent plays, with Sigismundus, Prinçe van Poolen (after Calderon’s Het leven een droom) as the big success, with 133 performances.

The complicated narrative structure of The Pitiful Coercion runs as follows. The love of the couple Dionysia, daughter of the English king, and Henryck, a count, is thwarted by the courtier Octavio. The latter disguises himself as Henryck and spends a sweet night with the crown princess. Henryck, for his part, waits for his beloved in vain and leaves desperate. Octavio’s deception leads Henryck to think that Dionysia has betrayed him (the court is full of rumours about the princess’s night of love), and she in turn thinks that her lover has left her because he has fled to his original wife Rosaura. The audience watches everything happen, knows the true facts (having witnessed Octavio’s ruse) and sees how a spiral of shame, false accusations and revenge unfolds. When the king (for the audience obviously hinting at his own daughter) asks Henryck what he would do with a man of lower rank who leaves a crown princess for his wife after a night of love, the latter condemns himself to death with his answer: ‘by the murder of his wife; in punishment of his evil and wicked deed’ (Reference VegaVega, 1671: 42, quoted in Reference BlomBlom, 2021: 238). The audience then knows how things stand. Henryck’s wife, Rosaura, however, will come to her husband’s rescue: she will sacrifice herself. Henryck, however, cannot cope with that and sends her out to sea.

The scene between the third and fourth acts shows Rosaura floating at sea in a small boat. Rosaura then disguises herself as a servant – before 1655, when the first female actresses enter the stage, the audience thus sees a man playing a woman disguised as a man. In the final scene, the moment of the execution of (a blindfolded) Henryck has arrived. When the sword is about to strike, Rosaura steps forward, disguised as a guard, to reveal the true cause of all the misunderstandings and expose Octavio as the guilty party. A duel ensues between Rosaura (still in disguise) and Octavio, who does not want to be insulted by a servant. Octavio wounds his opponent, who is brought down but still breathing, whereupon Vos inserts the following dialogue between the bystanders on stage:

Alt(enio): Oh, no, there is still life there.

Fab(io): Depart, my lord, depart, and please give him breathing space / Untie his bosom. So, alright now, I trust / it will get better.

Klen(ardo): Oh wonder! It’s a woman.

Cel(inde): In fact, it’s Rozaura, my hope is deceived.

Clearly, with such a wide range of characters, disguises and twelve musketeers, the play ‘switches’ constantly by fluctuations and turns that together represent the ‘turmoil’ or capriciousness of baroque existence.

Whereas in de Vega’s version a number of things are revealed only through the characters’ discourse, Vos adds three performances accompanied by music (Reference BlomBlom, 2021: 234–47), a series of visual effects, including a tableau (non-existent in the Spanish tradition) and a duel. The audience’s attention must be fed with ever-new twists. This accumulative dramaturgy fitted in perfectly with the possibilities but also the limitations that the Amsterdamse Schouwburg had to offer at that time (Reference Yannice DeBruyn, 2021).

The Amsterdam theatre of 1637, where De beklaagelycke dwang had its premiere, was ‘a curious mixture of old-fashioned and modern’ (Reference Hummelen and ErensteinHummelen, 1996: 202). Its circular form was reminiscent of the Elizabethan theatre. Just as in the French jeu-de-paume theatre, there was no strict separation between the stage and the audience. At the same time, the floor plan suggests the Italian influence of Palladio’s Teatro Olympico in the northern Italian town of Vincenza. The influence of the rhetorician theatre, with the system of the ‘open camer’, is also unmistakable. The architect van Campen explicitly fell back on Roman models for his design, which allowed him to draw a parallel between Amsterdam and Rome. This parallel was also picked up by Vondel in his foreword to the play Gysbreght:

The classical arrangement of the theatre suggested a certain degree of equality between the citizens, fitting in nicely with the self-image of Amsterdam as the epicentre of a self-confident bourgeoisie. Significantly, though, van Campen would add two rows of boxes to his Roman inspiration, providing a space for the burgeoning commercial elite to distinguish itself socially and spatially from the rest of the public.

Van Campen provided a semi-circular auditorium with a 16-metre-wide stage (Figure 11). The auditorium was surrounded by galleries that faced the parterre rather than the stage (Figure 12). The stage is organised horizontally – that is, in breadth rather than in depth (Figure 13). At the back of the stage there was a removable rear wall with a system of screens, turning the stage into a flexible instrument, which allowed the theatrical space to be adapted to various types of play (Reference KuyperKuyper, 1970; Reference Hummelen and ErensteinHummelen, 1996; Reference ErensteinErenstein, 1996). The polytopic model made it possible to present action in different places on the same stage at the same time. That same stage could also be transformed into a monotopic space via the screens. The wide, horizontal stage opening fitted in perfectly with the accumulative structure of the play: the spectators could let their gaze navigate over a synthetic representation of the action. A play such as De beklaagelycke dwang fits in perfectly with this theatrical space: van Campen’s model made it possible to bring together a wide range of characters on stage and to navigate smoothly from one intrigue to another.

Figure 11 Floor plan for the rebuilding of the theatre in Amsterdam, 1658. Willem van der Laegh, after Philips Vinckboons (II), after Jacob van Campen, 1658 engraving.

Figure 12 Auditorium of the 1637 Amsterdam theatre on the Keizersgracht.

Figure 13 Salomon Savery (1658), stage of the 1637 Amsterdam theatre.

Immersion and Depth

The new theatre opened in 1667 with the appearance of the sorceress Medea on its stage. The choice of this play was no coincidence: the abundance of violent scenes required new techniques which would have been impossible to show in the old theatre. The new theatre and its spectacular machinery enabled sorcery through the creation of immense, credible experiences and the use of a perspective of depth. In this context, the character of Medea may be perceived as the symbolic start of a new theatrical regime.

Jan Vos published his version of Medea with the telling subtitle Treurspel met Konst- en Vliegh-werken (Tragedy with Artifice and Airborne Techniques; 1667). That same year, the sorceress Medea appeared for the second time, in Lodewijk Meijer’s Gulden Vlies (Golden Fleece), which added a good deal of spectacular effects. The play by Jan Vos reads like a programme statement. Not only did he put his personal poetics into practice; he also showed what the theatre could achieve as a new dream machine. Vos presented Medea as a force of nature, from a foreign country, defying all laws. Just as Medea is not constrained by the limitations of reality, Jan Vos sets aside the limitations of the outdated theatrical regime. He performed magic not only with the character of Medea but with reality itself. Explicit theatricality thus made way for magical immersion.

In his Medea, Vos opts for fierce violence, with the fourth act its undoubted climax. Medea, ‘on a chariot pulled through the air by two fire-breathing dragons’ (Vos, 1667: 55), throws her children from the chariot, smashing them on the stage:

Iaz.: O give me my children, hear how thy Jazon flatters.

Med.: There are thy children: is Jazon now flattered?(She flies with the chariot into the air, and throws the children on the ground; the ghosts sink.)

Iaz.: I hear, O gods, I hear their skulls cracking.

Vos makes eager use of the possibilities of the depth of the new stage and the machinery offered by the new theatre. He has Medea change the pleasure garden of the first act into a wild mountain landscape, ‘Here the pleasure garden, at the stamping of her foot, must turn into mountains’ (Vos, 1667: 28), and then back again: ‘Here the mountains turn into a pleasure garden again’ (Vos, 1667: 28). In this way, Vos introduced the audience to the coulisse theatre, which made it possible to replace one scene with another, as if the theatre were a slide projector – in contrast to the spatial and dramaturgical stacking of the old theatre. In the same act, Medea turns the two guards into a tree and a pillar:

And still, it is not enough. Because the guards keep talking, to Medea’s great irritation, she changes them into a bear and a tiger. And so, Medea becomes the mirror image of Vos’s poetics: unbridled, untameable, a force of magic and artifice.

The need for a new theatre in Amsterdam, less than four decades after the first one opened, seems to have been informed by the growing interest in immersive theatrical experiences. According to one of the theatre directors, the old theatre was ‘much too wide and short’, and ‘because of its heaviness and solidity, it cannot be quickly and easily changed time and again, easily, according to the demands of the play’ (Domselaer, 1665: 207, quoted in Reference BlomBlom, 2021: 354). The new theatre should be able to ‘work magic’ by expanding its technical capacity through the architecture of the building and the integration of new theatrical techniques. The design by Philip Vingboons followed the latest trends in European, specifically Italian, theatre architecture. It was informed by Nicola Sabbatini’s famous Pratica di fabricar scene e machine ne’ teatri (1638), which circulated widely in Europe and provided many designers with the blueprint for their new theatres. The Roman-inspired semi-circular auditorium, with its wide, short stage, was replaced by a horseshoe-shaped hall with a deep-winged stage. The auditorium and stage were separated by a stage arch, with a spacious orchestra pit. The proscenium could be closed off with a curtain. In contrast to the old theatre, the new model was aimed at an individual viewing experience. The spectators were invited to immerse themselves in the peepshow reality that unfolded on stage. The new design thus can be seen as an attempt to transform the stage into an autonomous reality through monotopic spatiality.

Spectators no longer entered from the side but from the back. The parterre (bak) held ten rows of benches. At the back there were a limited number of standing places. The cheap seats were located at the top. The regents’ loge, accessible from the regents’ room, was close to the stage and offered an ideal view of the scene. Vingboons’s design thus brought the Republic in line with other European, monarchical regimes, whereby the theatrical reality was adapted to the perspective of a sovereign (l’oeil du prince) and the spectator space was hierarchically arranged according to the distance from that ideal perspective (Reference SurgersSurgers, 2009; Reference HewittHewitt, 1958).

At the opening of the new theatre on 26 May 1665, Jan Vos had an allegorical poem performed in dialogue form, entitled ‘Inauguration of the Theatre of Amsterdam’. In that poem he not only highlighted the social, educational and charitable function of the theatre but especially praised the new technical possibilities, presenting them to the reader to arouse the spectator’s desire to see the same techniques used more extensively in other plays: ‘Here one sees the sea and the beach, surrounded by steep mountains. […] Now you see tents, which surround a large city […] Here art shows a forest in which the light never shines. […] Here a building, full of glory, is shown to you’ (Reference Amir and ErensteinAmir, 1996: 258). The new theatre offered a whole range of new techniques, some of which were depicted in van Frankendaal’s print (Figure 14): seven trapdoors for appearances and disappearances, a machine for a raging sea, the possibility of working with fire and smoke, and especially a series of ‘flying works’. In Medea, Jan Vos used a ‘heavenly globe’, a flying cloud in which actors could travel: