Introduction

As the market economy fails to provide adequate insurance against income risks to which workers are exposed, different forms of labour regulation become an institutional response to those risks (Reference BertolaBertola, 2009). Minimum wages are a nearly universal policy instrument – they are applied in more than 100 countries (ILO, 2008). Empirical studies focus on effects of the level of the minimum wage (or the ratio of the minimum wage to the average/median wage – the Kaitz index), on unemployment, poverty and wage distribution (Reference BetchermanBetcherman, 2012). Far less attention has been paid to different types of minimum wage fixing mechanisms and their possible economic consequences. One of the most cited studies that investigate the link between the mechanism for minimum wage setting and its level is the article by Reference BoeriTito Boeri (2012). Boeri finds that government-legislated minimum wages are significantly lower than minimum wages set through collective agreements (Reference BoeriBoeri, 2012). The quality of industrial relations is an important determinant of the minimum wage setting mechanism (Reference Aghion, Agan and CahucAghion et al., 2008). In systems with advanced industrial relations, national employers’ organisations and trade unions are influential, and collective wage bargaining covers the majority of workers and there is little need for government-legislated minima. Government intervention becomes a necessity when the trade unions are weak and employers are fragmented.

Unfortunately, time-series data on variation in minimum wage levels (relative to average wages) and, especially, its relationship to wage fixing regimes are very low in most countries. In this article, we undertake a case study of the reform of the minimum wage setting mechanism in Russia. This reform, introduced in 2007, involved the decentralisation of minimum wage setting, which gave Russian regions the power to set their own regional minima above the federal floor. It was followed, not accidentally, with extremely large increases in the federal minimum wage (FMW). Our main objective is to explore the determinants of changes in Russia’s minimum wage policy, its main features and the consequences for the labour market.

The rest of the article is organised as follows. The section ‘The institutional framework of minimum wage fixing in Russia and the role of social partners’ describes the institutional background of minimum wage setting in Russia after the collapse of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). The section ‘Why did the reform of minimum wage fixing became an urgent problem in Russia?’ details the major drawbacks of this system. The section ‘Reform of the minimum wage setting mechanism and its consequences’ outlines the key feature of the 2007 reform of the minimum wage setting and discusses whether the reform has reached its goals, and it is followed by the conclusion.

The institutional framework of minimum wage fixing in Russia and the role of social partners

The minimum wage has existed since the Soviet period. The former USSR belonged to the group of countries with government-legislated minima. The rate was set by the central government and approved by the Supreme Soviet (the USSR parliament). Negotiations with unions on the minimum wage rate were predominantly of a token or ceremonial character. The relative value of the minimum wage during the Soviet times was comparable to that observed in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) economies. In 1985, the minimum wage was equal to 70 rubles. Given the average wage of 190 rubles (Goskomstat, 1987), this wage level yields a Kaitz ratio of about 37%. Even in 1991, the Kaitz ratio was equal to 25% (Figure 1). However, wages of Russian workers during the communist period were very low by international standards.

Figure 1. The federal minimum wage as a percentage of the average wage, 1992–2013.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on Rosstat data.

Minimum wages are not adjusted for regional coefficients.

The minimum wage fixing mechanism that emerged after the start of market reforms in Russia inherited many features from the central planning system. The country had a single FMW that was applied and combined with a rigid mechanism for its regional differentiation. During the Soviet era and the early period of transition, minimum wages were differentiated across Russian regions via regional coefficients. In Northern and Far Eastern territories but also in some continental regions with adverse climate conditions, the FMW was multiplied by regional coefficients. The regional coefficients were used as a financial instrument to attract labour to highly industrialised but low-populated areas rich in natural resources. The system was inflexible because regional authorities could not influence either the value of the FMW or the size of the coefficients.

The minimum wage was applied universally to all groups of workers, regardless of age, occupation or industry. This means that wages of both teenage workers and employees with long tenures were subject to equal minima. However, that was not entirely true for every occupation, as the minimum wage related to gross monthly earnings net of mandatory regional wage supplements, shift pay, other compensations and bonuses (hereafter, we refer to this wage concept as the ‘tariff’ wage). The labour safety legislation specified dozens of special compensating coefficients for work in hazardous and hard conditions. This framework introduced certain differentiation of minimum wages across occupations and industries. As opposed to most countries, small firms and micro-businesses were not excluded from the regulation.

The Labour Code adopted in 2002 set an explicit target to increase the level of the minimum wage and equalise it with the national subsistence minimum.Footnote 1 This provision was a result of bitter negotiations between the government and trade unions. When introduced into the legislation, it did not take into consideration any economic factors. At the same time, the Labour Code states that this legislative provision should be implemented by a special legal act, which has been constantly delayed. This delay has been used as an indirect way to take account of economic conditions. Actually, the process of minimum wage fixing still lacks a binding target. The legislation has not identified the periodicity of minimum wage adjustments. Since the early 1990s, adjustments of the minimum wage have been irregular and have varied greatly in size.

Formally, the value of the mandatory minimum wage is set by a law passed by the parliament based on the proposal by the federal government. However, first of all a consensus about the level of minimum wage must be achieved within a tripartite Commission, which consists of representatives of employers’ peak associations, trade unions and the federal government. The tripartite Commission sits on a permanent basis, but it is especially active during the preparations for and signing of a 3-year general agreement. The process serves as the ideological symbol of social partnership in Russia. According to the classification of Reference BoeriBoeri (2012), the Russian system of minimum wage determination is a ‘consultation process’ where the new level of the wage minimum is the result of negotiations between the state and the social partners.

It should be admitted that in comparison with the centrally planned economy, the role of the social partners is no longer merely formal. At the same time, Russian trade unions and employers’ organisations have not become equal partners to the government. The government plays still the leading role in the tripartite Commission in deciding the level of the wage floor. The prominence of the federal government is partly justified by the fact that the state remains a large employer: in 2012, 29% of all employees worked in the state and municipal sector of the economy and an additional 6% worked in mixed (state-private) enterprises (Rosstat, 2013a).

From a formal point of view, Russian unions may be proud of high density rates. The majority of Russian unionised workers are members of the Federation of Independent Trade Unions of Russia (FITUR) which is a successor to the traditional communist unions. The FITUR suffered from a severe membership decline from almost 100% in the communist period to 33% of total employment in 2013.Footnote 2 Nonetheless, the federation remains the most powerful trade union organisation in modern Russia. Other independent trade unions established over the transition period are small and make up only 5% of the total union membership (Reference ChetverninaChetvernina, 2009). Nominally, the FITUR represents all Russian workers in the central tripartite Commission.

Along with traditional reasons for decline in union membership (globalisation, disappearance of blue-collar industrial jobs, growth of the service economy), there are some explanations that are specifically relevant to post-communist countries. They witnessed declining density because of the transformation from obligatory to voluntary union membership. The trade union movement as a whole is increasingly confined to the residues of the old state industrial sectors of the economy. The most highly unionised members of the FITUR are large companies in manufacturing and mining where density rates approach 70% of all employees. The FITUR has made little effort to recruit new members in the emerging private sector, especially in the expanding segment of the service economy and small- and medium-sized enterprises.

The current situation with collective bargaining agreements in Russia is characterised by a weak regulatory impact of unions on wage policy and working conditions at the enterprise level. The system of wage setting in Russia can be called ‘managerial’ as managers determine wages in Russian enterprises. Russian trade unions are not effectively able to determine the wages and working conditions of their members at the grassroots level and adhere to the strategy of negotiating these issues with the government, rather than directly with employers. Many FITUR leaders share the hope that legislation and government regulation will grant what unions are unable to achieve by their own efforts. The traditional unions have embraced the principles of social partnership as collaboration with the state. This collaboration provides them with some guarantee of retaining their former privileged status and neutralising the challenges of the alternative trade unions.

The fragmentation of employers’ organisations is another barrier to the development of social partnership in Russia. They are unable to serve as an effective unions’ counterpart in negotiations. Unlike trade unions, which existed in the Soviet times, employers’ organisations were established only after the start of the transition period. Naturally, the first employer organisations represented the largest state and former state enterprises. The main purpose of these organisations was not to present the enterprises as employers but to provide them with a channel for lobbying the federal and regional authorities for tax credits and other privileges and establish personal connections with government officials. In subsequent years, several hundred employers’ organisations have been set up at the national, regional and industry level. As a result, the employers’ side has more fragmented organisational structure than the workers’ side does.

Over the transition period, Russian employers experienced enormous difficulties in establishing umbrella organisations. Now, the Russian Union of Industrialists and Entrepreneurs (RUIE) is the leading employers’ organisation. It acts on behalf of large and some medium-sized enterprises. The RUIE, as the most powerful peak organisation, is the main social partner in the central tripartite commission. Small- and medium-sized enterprises are united in a number of separate organisations that also participate in the work of the tripartite Commission. However, they do not possess any real power, either politically or in industrial relations matters.

Summing up, Russia entered a market economy with a rigid government-dominated mechanism for setting the minimum wage that was previously based on a single minimum, but complicated by hundreds of coefficients aimed to adjust for regional diversity and differences in working conditions. The limited membership of employers’ organisations, on one hand, and the lack of ‘fighting spirit’ among Russian trade unions, on the other hand, have led to the situation when both social partners look to the state rather than to their immediate counterparts to undertake the obligations of social partnership including the setting of the minimum wage.

Why did the reform of minimum wage fixing became an urgent problem in Russia?

Low level of the minimum wage

The levels of minimum wages relative to average wages vary widely across countries, but there is a relatively high frequency at around 40% of average wages (ILO, 2008). In post-reform Russia, this indicator has never reached this level. Figure 1 shows that, for most of the transition and post-reform period, the minimum wage in Russia was so small that it can be defined, using the expression of Reference SagetSaget (2008), as a ‘mini minimum wage’ (p. 27). During the first decade of economic transition, the Kaitz index demonstrated a downward trend with short-lived upsurges at the points of minimum wage hikes. The low of 4% was reached in 2000.

In the economic literature, low minima are usually found to be unintended consequences of the link between minimum wages and social benefits including pensions, maternity and unemployment benefits (Reference SagetSaget, 2008). Indeed, over the 1990s, the wage minima in Russia were used as a reference value for several welfare provisions, tax exemptions and some fees (e.g. traffic fines). The linkage of the minimum wage with social benefits increased potential budgetary costs of the minimum wage increases. In 2000, the government decoupled the minimum wage setting mechanism from the social security and tax systems, introducing two types of ‘minimum wages’. The first type is traditional minimum wage used as a floor in the wage setting. The second type functions as the basic tariff for taxes, penalties and other administrative payments (Reference BolshevaBolsheva, 2012). Both types of minimum wages are still called ‘minimum wages’, causing certain confusion in the legislation. Throughout this article, we are talking exclusively about the first type of minimum wage.

Given the low level of the minimum wage, it is not surprising that only a small share of the workforce had wages at or below minimum wage.Footnote 3 The group of minimum wage earners represented 1.6%–2.4% of all workers in 1996–2005 (Reference Vishnevskaya, Gimpelson and KapelyushnikovVishnevskaya, 2007: 171). The incidence of the minimum wage varies substantially across industries. In 2006, the proportion of workers with wages at or below the minimum ranged from 0.2% in mining to 15.6% in agriculture (Rosstat, 2007).

The majority of low-paid workers are concentrated in the public sector of Russian economy (Reference LukiyanovaLukiyanova, 2011) and the budget bears the financial burden of minimum wage increases. Additionally, for a long time the FMW was equal to the lowest grade of the Unified Tariff Scale (UTS). The UTS was the basis of the payment system for employees of all government levels. Base salaries of all budgetary sector workers and civil servants were defined as the product of the minimum wage and the grade coefficient fixed in the UTS for each occupation and qualification level. Therefore, any up-rating of the FMW triggered, through the UTS coefficients, an increase in the all tariff wages in the budgetary sector. The UTS coefficients gave rise to significant spillover effects on the entire wage distribution, including the top deciles (Reference Gimpelson and LukiyanovaGimpelson and Lukiyanova, 2009).

The Russian model of social partnership is based on a weak form of tripartism which leaves the minimum wage largely an instrument of local and national politics (for more detailed discussion, see Reference CrowleyCrowley, 2002). In this model, the FMW increases were infrequent and motivated by political factors. The FMW was raised 11 times between 1992 and 1997 – seven revisions occurred in the pre-election periods.

High earnings inequality and high incidence of working poverty

The introduction of market reforms led to an immediate increase in wage inequality. The sharp growth of wage dispersion was observed in the early stage of transition, but later it slowed down. The Gini coefficient for wages rose from 0.22 at the beginning of transition period to 0.5 in 1996 (Reference Flemming, Micklewright, Atkinson and BourguignonFlemming and Micklewright, 2000). The peak of inequality was recorded in 2001. Less skilled workers lost substantially both in real terms and relative to skilled workers. The large increase in inequality in the bottom part of the distribution reflects the erosion of the minimum wage during the reform period (Reference BrainerdBrainerd, 1998).

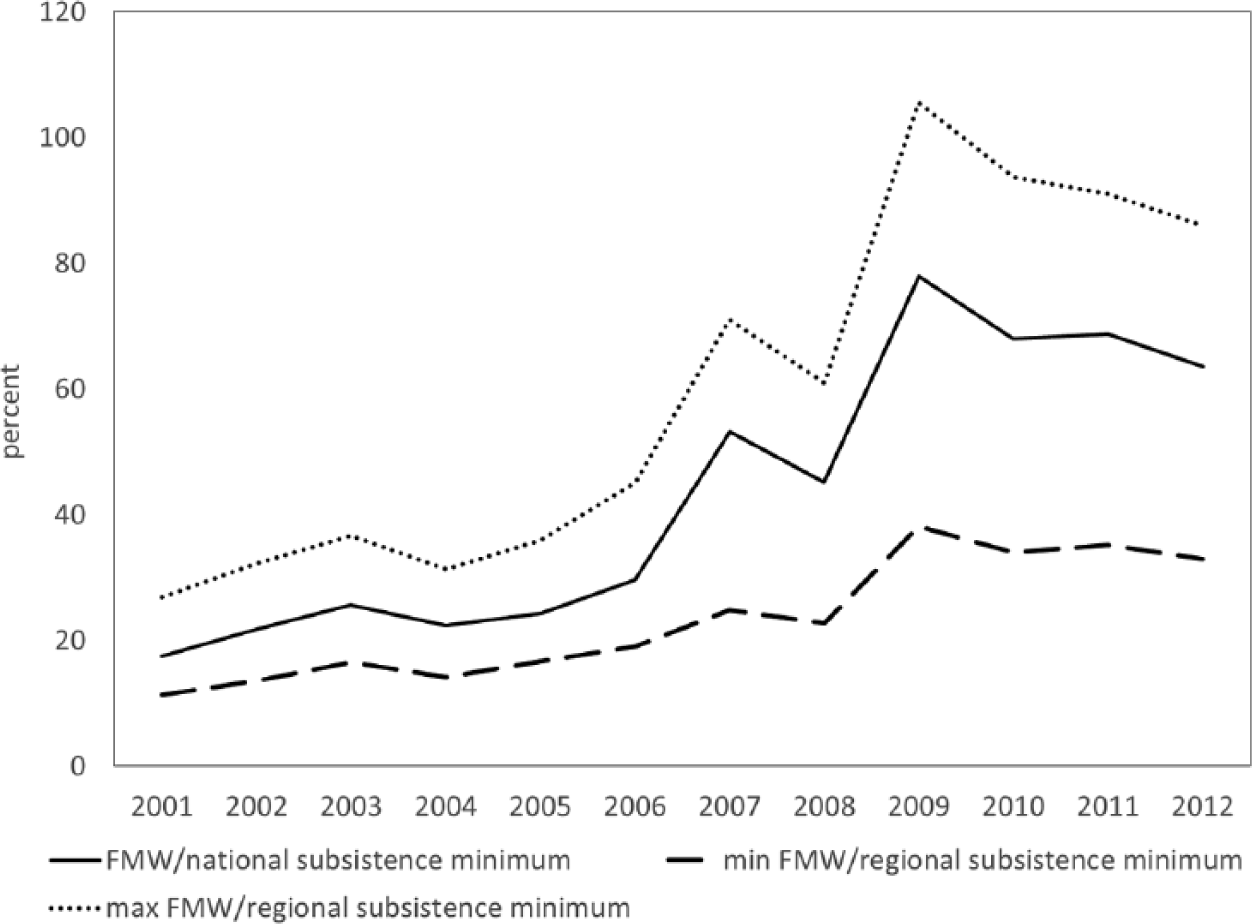

The minimum wage does not cover the basic needs of workers as it has always been below the poverty line (Figure 2). In 2006, the FMW marked up less than 30% of the national subsistence minimum used as a poverty line in Russia. For the whole period between 2001 and 2008, it failed to reach the poverty line even in poor regions. The share of workers with a wage below the subsistence level was equal to 22%–24% in 2005–2006. The wages of another 30% of workers were in the range of one to two subsistence levels, implying a high risk of absolute poverty for their families. Of course, the link between low pay and poverty is not straightforward, and low-paid workers are often supplementary earners in multiple-earner households or trainees who work to gain job experience. Nonetheless, the incidence of poverty among the low-paid (with a wage of less than two-thirds of the regional median wage) is almost 30% higher than the average, and they constitute a quarter of those in poverty (Reference DenisovaDenisova, 2012).

Figure 2. Federal minimum wage as percentage of the subsistence minimum – working age population, Russia.

Source: Authors’ calculations from the Rosstat data.

Minimum wages are adjusted for regional coefficients in 2001–2006 (as required by the law), for later years – without adjustment. Based on data for the fourth quarter of each year.

Inadequate regional differentiation

The overall dynamics of the minimum wage masks strong differences across Russian regions. The group of high-wage regions includes the major cities (Moscow and St-Petersburg) and surroundings, and regions rich in natural resources. The lowest average wages are paid in the regions of North Caucasus, South Siberia and some parts of Central Russia. Most of the regional disparities (e.g. in wages, life expectancy) peaked in the early 2000s and began to decline thereafter, reflecting changes in budgetary policy to redistribute huge oil revenues (Reference ZubarevichZubarevich, 2011).

The divergence of regions in terms of economic performance is to a large extent related to geographical position and the concentrated industrial structure inherited from a command economy. Many small towns and even entire regions still depend on the performance of a single enterprise or single industry and therefore are very sensitive to various negative economic shocks. Several political and institutional factors contributed to widening of regional disparities. During the early period of the economic transition, a weak federal government and lack of legislation allowed large companies governed by ‘oligarchs’ to ‘capture the state’ and influence the pace and direction of economic reforms according to their interests. Over time, with the growing power of the state, the situation evolved into a form of elite exchange in which large companies receive favourable treatment in return for providing benefits to state agents, including corruption (Reference FryeFrye, 2002). The power of large companies is mostly strong at the regional level. Moreover, dysfunctional incentives created by the interaction of electoral pressures with the system of fiscal federalism led to excessive growth of public employment in economically depressed regions (Reference Gimpelson and TreismanGimpelson and Treisman, 2002).

Figure 3 shows that the national Kaitz ratio can be misleading in assessing the regulatory pressure of the minimum wage. In the richest regions, the Kaitz ratio was well below 5% for the entire period before 2007 while it exceeded 20% in poor regions. This finding suggests that the FMW created very diverse institutional settings at the regional level, with lowest wages facing the most unfavourable regulatory environment.

Figure 3. The FMW as percentage of average regional wage.

Source: Authors’ calculations from Rosstat data.

Minimum wages are adjusted for regional coefficients.

The purchasing power of the FMW varied dramatically across regions (Figure 2). The generosity of the minimum wage tends to be lower in the rich regions, while in poor regions it provides higher (albeit, extremely low) living standards. In Q4-2006, the FMW (adjusted for regional coefficients) covered 19% of the regional subsistence minimum in Moscow and about 45% of the regional subsistence minimum in Kemerovo region. Adjustment for mandatory regional coefficients had limited equalising effect: the unadjusted ratios of the minimum wage to the regional subsistence minimum varied from 13% in Chukotka to 42% in Dagestan. The reason is that the regional coefficients were designed for the needs of a command economy with full control over prices and large fringe benefits. They reflected climate differences and disregarded the contributions of other location amenities and differences in the level of economic development and costs of living.

Reform of the minimum wage setting mechanism and its consequences

Description of the reform

In 2007, the Russian government, with the support of social partners, initiated a reform of the minimum wage setting mechanism. The reform had several objectives, but one of the main aims was to increase living standards and differentiate the real minimum wages across Russian regions with regard to differences in wages, prices, costs of living and financial capacities. The reform also was intended to shift the financial burden of raising the minimum wages from the federal to regional budgets. The low level of the minimum wage became unacceptable for political reasons during the period of economic growth. Finally, high oil prices and budget surpluses made it possible to increase the wages of the public sector workers who constitute the majority of minimum wage recipients in Russia. The upgrading of the minimum wage was eased by the reform of wage setting in the budgetary sector. The UTS was abandoned in 2008 and replaced with a more flexible system delinked from the minimum wage. In the new system, wages are determined by collective agreements and local legal acts that establish the base salary, payments for qualification levels, compensations and bonuses. Managers of budgetary organisations received much more flexibility in determining wages and employment numbers (OECD, 2011).

Until 2007, the Russian model of the minimum wage setting was highly centralised since regions were completely deprived of the opportunity to influence its level. Following the 2007 reform, all Russian regions were empowered to define their own regional minimum wages (RMWs) with the only condition being that the RMWs should be set above the federal floor. This development was in line with international experience showing that the centralised model does not account to the specifics of regional economies.

The implementation of reforms demands for active cooperation between local authorities and social partners at the regional level, as the rate of the regional wage floor is now established by consent of all parties: regional employers’ associations, trade unions and local authorities. A very important aspect of the process is agreement among the parties on the wage floor which is acceptable for the majority of local employers. It means that one of the expected consequences of the reform is the strengthening of social partnership at the regional level.

Simultaneously with the introduction of regional sub-minima, the procedure for calculating the minimum wage was modified. It was made to neutralise the possible negative impact of the rapid increases in the minimum wages. Until 2007, it was the basic tariff rate that must be not less than the minima and all compensations and bonuses were paid in excess of the wage floor. The introduction of a new approach to the calculation of the minima can be explained by the peculiarities of wage formation in Russia. In Russia, the use of the variable wage component is much more frequent, and the share of bonuses in wages is much higher than in other countries reaching 40%–50% of total wage bill in the mid-2000s (Reference Vishnevskaya and KulikovVishnevskaya and Kulikov, 2009). Thus, if the use of regional minima led to the increase in the minimum wage rate, the changes in the definition of the wage floor were aimed to suppress its growth. The 2007 reform has not changed the coverage of the minimum wage: it remained universally applied regardless of worker age, firm size, ownership type and legal status.

The implementation of the reform and its consequences

The rapid rise of the real minimum wage was the most apparent consequence of the reform. The minimum wage was increased four times since September 2007 when the reform provisions came into legal force. Two increases were particularly large. The nominal minimum wage was raised by 109% in September 2007 and 88% in January 2009. Later increases were much smaller in magnitude (6.5% in 2011 and 12.9% in 2013). In total, the FMW rose by a factor of 4.7 in nominal terms and by a factor of 2.9 in real terms between January 2007 and January 2013. The Kaitz index, which was equal to 8%–9% in the year preceding the start of the reform, rocketed to 25% in the beginning of 2009 (Figure 1).

The 2007 reform of the minimum wage setting removed the link between the minimum wage and the regional coefficients. This change generated additional variation in the minimum wage increases across regions. In particular, most regions experienced an increase in the nominal minimum wage by 109% in September 2007. Some Northern territories like Chukotka had a small increase of 5% (Reference Muravyev and OshchepkovMuravyev and Oshchepkov, 2013).

Figure 4 maps the ratios of the FMW to average regional wages in August 2007 and January 2009. The decentralisation reform increased the variation in the regional Kaitz indices based on the FMW. Before the reform, the Kaitz ratio varied from 4% to 5% in the oil-rich Tyumen region to 15%–20% in ethnic regions of Caucuses and South Siberia, with substantial clustering of regions in the 8%–10% range. The doubling of FMW and elimination of the regional coefficients led to a considerable increase in the regulation burden. The pressure hardly changed in Northern areas, where the Kaitz ratios increased to 6%–7% and doubled in the depressed regions where the Kaitz ratios reached 30%–40%. The next upgrading in January 2009 further increased the variation in the ‘bite’ of the FMW. In Russia’s highest wage regions, the minimum wages were equivalent to 12%–15% of average wage. By contrast, in 15 of the lowest wage regions the figure exceeded 50%. This means that at least in some regions, the minimum has become binding at sufficiently high percentiles of the earnings distribution. Additionally, some regions received ample room for increases at the regional level without fears of causing unemployment, while other regions had to cope with a shock change in the regulatory pressure. However, for most regions, the Kaitz index was in the range between 25% and 30% with the unweighted average of 28%, which is not high compared to other countries. In 2010–2013, increases in the FMW were gradual and lagged behind the growth of the average wage leading to substantial decline in the Kaitz ratio in the most affected regions. By January 2013, the maximum of regional Kaitz ratios declined to 36% and the unweighted average to 24%.

Figure 4. The FMW as percentage of average regional wages, Russia, 2007: (a) August 2007 and (b) January 2009.

Source: Authors’ calculations from the Rosstat data.

Minimum wages are adjusted for the regional coefficients for August 2007; no adjustment is made for other periods.

The degree of toughness of the minimum wage is measured by the proportion of workers paid at or below the minimum. The average proportion of affected workers is very small: it peaked in 2009 at 3% of all workers and declined to 1.8 in 2011 and 1.2% in 2013.Footnote 4 The minimum wage incidence is significantly lower than in many developed and emerging economies, where this share often exceeds 5%–15% (OECD, 2015: 44). Generally, regions with higher Kaitz ratios also have larger shares of minimum wage earners. However, regional variation is significant (Figure 5). For example, in 2009, 11.3% of workers had wages at or below the minimum in Dagestan (the darkest region on the map) compared to 0.1% in the Northern regions. Although evidence is not available, in the poorest regions like Dagestan the minimum wage may have larger effects increasing incentives for non-declaration and under-declaration of wages.Footnote 5 The agricultural sector should be particularly concerned as, in Dagestan, the minimum wage exceeded 130% of actual average wages in agriculture before its hike in 2009 (OECD, 2011).

Figure 5. Share of full-time workers at or below the FMW: Russia, 2011.

Source: Rosstat, results of the April Survey of earnings distribution, 2011.

The minimum wage increases introduced in 2007 and 2009 led to a substantial increase in the purchasing power of minimum wages. In Q1-2009, the FMW increased to 80% of the national subsistence minimum of the working age population (Figure 2). The improvement of pay standards was impressive in the poor regions where the regional subsistence minimum is below the national level. In the poorest regions with relatively low prices, the minimum wage stayed above the regional poverty line for 2009 and for part of 2010. The regions with higher prices did not gain much from the minimum wage hikes. First, many of these regions are located in northern areas and the Far East; therefore, they experienced only modest increase in the minimum wage after elimination of the regional coefficients. Second, the implicit intention of the policy makers was to trigger the introduction of RMWs set through collective bargaining at the regional level.

The Russian regions actively took advantage of the right to set their own sub-minima. Regional tripartite agreements, in setting the wage floor, take into account the economic and social situation in the particular region and the phase of the economic cycle as well. By the end of 2007, 27% of all Russian regions had introduced the regional minima, which were higher than the federal wage floor (FITUR, 2015). By the end of 2008, the share of regions with their own minima reached 49%. The RMWs proved to be very sensitive to the economic cycle. Moreover, in some regions, the regional sub-minima was surpassed by the FMW after its increase in January 2009. As a result, the share of regions with regional sub-minima declined to 32% in the beginning of 2009. Later on, with the improvement of the economic situation in Russia, the regions returned to the practice of setting their own minima. In 2013, regional sub-minima existed in 62% of all Russian regions.

The co-existence of the FMW and regional sub-minima has led to new imbalances. Workers employed by federal establishments and enterprises are exempt from the RMW legislation. In some regions, regional and municipal employees are also excluded from regional regulation and the regional wage floor applies only to private sector workers.Footnote 6 In 2012, coverage was limited to the private sector in half of all regions that had introduced the regional sub-minimum (in 25 regions out of 53 regions that introduced regional sub-minima). Several other regions set different sub-minima for the private and public sectors. This means that in the same region substantial groups of workers have relied on a lower minimum wage. Such frameworks seem to be a compromise between the willingness of local elites to be popular among the public and safeguarding regional budgets.

Detailed examination of the determinants of minimum wages at the regional level is beyond the scope of this article and deserves a separate study. The first impression is that economic concerns have limited impact. Table 1 shows that the decentralisation reform failed to increase regional variation of minimum wages measured by the coefficient of variation.Footnote 7 Regional variation in minimum wages dropped abruptly after the elimination of the regional coefficients (compare the numbers for 2005 and 2007). An extremely generous increase in the FMW in January 2009 further reduced the variation since it surpassed many of existing regional sub-minima. Regional variation increased moderately in later years following the decline in the real value of the FMW and recovery from the 2008–2009 global economic crisis. The rapid fall of regional variation in 2009 suggests that this increase was of excessively high magnitude, and that a more gradual approach to increasing the minimum wage should be advocated.

Table 1. Variation of regional minimum wages (RMWs), October.

FITUR: Federation of Independent Trade Unions of Russia.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from Rosstat and FITUR monitoring.

Regional minimum wages in each region are corrected for differences in coverage.

a Unweighted average.

Figure 6 shows the relationship between regional sub-minima and regional wages in Q4-2012. Dashed vertical and horizontal lines depict the national average wage and the FMW, respectively. There is a positive correlation between the minimum wage and the average wage at the regional level. High-wage regions are more likely to introduce regional sub-minima that cover all workers. Poor regions have a higher probability of staying with FMW or of limiting the coverage of regional sub-minima to private sector workers. However, the correlation between two variables is far from being perfect. Several high-wage regions have not introduced the minimum wage. Businesses face a very different regulatory environment in poor regions: the Kaitz ratio can be 1.5–2 times higher in some regions than in others with similar average wages. According to our estimates, regional wage sub-minima increase the Kaitz ratio, on average, by 9% points in the regions that have introduced the RMW. Reference LukiyanovaLukiyanova (2011) estimates that on average the RMWs led to an additional 3.3% point increase in the share of minimum wage earners in such regions.

Figure 6. The relationship between regional sub-minima and regional average wages, Q4-2012.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on data from Rosstat and the FITUR monitoring.

*Regions that introduced minimum wages only for the private sector.

In 2002, the Labour Code set the value of the subsistence minimum as a long-term target for the minimum wage. This provision has not been implemented at the federal level (the introduction of the relevant article was conditional on the adoption of a special federal law that had not yet been adopted by 2015). However, the value of subsistence minimum seems to be a natural target for legislation at the local level, because regional minimal consumer baskets are cheaper than the national substance minimum. In fact, it is not a common practice to tie the regional sub-minimum to the regional subsistence level. In 2012, only 18 regions had this provision in regional agreements (including those that limit its coverage to private sector workers). They make up about 30% of all regions that have introduced the minimum wage. About half of all regions had wage sub-minima that were equal or exceeded the regional subsistence minima, at least, for public sector workers. At the same time, many regions with high costs of living either have not introduced the regional sub-minimum or have relatively low regional sub-minima.

Table 2 shows that low-wage workers benefited from the minimum wage hikes, especially in poor regions. Minimum wages are better related to the costs of living. Even in the worst performing region, the minimum wage covers about 39% of basic living costs compared to 24% in 2005. In a most generous region, this proportion increased from 64% to 141%. Interestingly, the most generous regions are found among the regions with relatively low costs of living; they usually limit the coverage to the private sector workers. Therefore, such generosity is largely populist because the majority of low-paid employees work in the public sector. More generally, poor regions with low costs of living benefited mainly from increases in the FMW. Regions with high costs of living had to increase the RMW. However, the overall regional variation in this indicator hardly changed between 2005 and 2011.

Table 2. The ratio of RMWs to regional subsistence minima.

RMW: regional minimum wage; FITUR: Federation of Independent Trade Unions of Russia.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on wage data from Rosstat and data on regional minimum wages from FITUR monitoring.

RMWs are corrected for differences in coverage.

a Unweighted average.

Enforcement of the regional sub-minima is especially difficult for several reasons. First, there is much uncertainty about the meaning of provisions set in many of regional agreements. For example, some regions have declared that the RMW is tied to the regional subsistence minimum but have not specified the exact procedure of its adjustment to changes in the subsistence minimum. Therefore, it is not clear how often the indexation should be made, or what time lag should be taken for the subsistence minimum. Second, issues of minimum wages are not the priority for monitoring agencies. The monitoring of labour legislation, including the minimum wage agreements, is carried out by state inspectors. Labour inspections are under-staffed, small businesses are rarely inspected, sanctions are low and play little role in preventing violations of the law. Third, the co-existence of different minimum wages at the regional level reduces the regulatory transparency and complicates enforcement.

What impact the 2007 reform had on the Russian labour market in terms of employment and wage inequality? Very few studies have investigated these effects empirically. Reference Muravyev and OshchepkovMuravyev and Oshchepkov (2013) found significant negative effects of the recent minimum wage hikes expressed in increased youth unemployment and higher incidence of informality. In contrast, employment of prime-aged workers was not affected by the minimum wage increases. However, the magnitude of the reported negative coefficients is so small that adverse employment effects are offset by positive effects on the wage distribution and incomes of low-wage workers. Reference LukiyanovaLukiyanova (2011) reported the earnings distribution has changed shape markedly in response to the minimum wage. According to her estimates, about 50% of the compression of lower tail inequality in the overall wage distribution is attributable to the increase in the real value of the minimum wage.

Conclusion

In this article, we study the minimum wage setting reform in Russia that aimed to decentralise the fixing of the minimum wage and to increase the involvement of the social partners in this process. The old system of minimum wage setting, inherited from the communist era, was based a single nationwide minimum wage which was differentiated across regions and occupations via a cumbersome framework of coefficients. The level of the minimum wage was determined by the government, with token ceremonial roles played by the parliament and social partners. The reform, which started in 2007, eliminated all coefficients. Instead, it gave regions the power to set their own minimum wages above the federal minimum through tripartite agreements at the regional level. The reform was not comprehensive in a sense that the procedures for setting the minimum at the federal level remained unchanged. Therefore, the new system is a mixture of the government-set minimum wage at the federal level and collective agreements at the regional level. The synchronised reform of pay in the public sector weakened the link between the minimum wage and wages in the public sector. These changes reduced the financial burden and the risks of minimum wage hikes and triggered a number of generous instances of upgrading the minimum wage.

The real FMW doubled over the period of less than 2 years. However, owing to the elimination of the regional coefficients, northern regions experienced moderate changes in both nominal and real minimum wages, whereas other regions faced a shock change in the regulatory environment. In 2009, the minimum wage reached the level of 40%–50% of the average wage in the low-wage region compared to 15%–20% before the reform. However, the increase in the share of minimum wage earners was small and short-lived even in the depressed regions, suggesting that regions – probably with few exceptions – are comfortable with the current level of the FMW. There is scope in richer regions to pay more than the FMW without employment effects.

Many regions took the opportunity to introduce their own wage sub-minima. In the beginning of 2013, regional wage sub-minima existed in 62% of all Russian regions, but the coverage was limited to the private sector in half of all regions that introduced the regional sub-minimum. Therefore, the generosity of regional sub-minima is largely populist because the majority of low-paid employees work in municipal establishments. The reform achieved its goal of raising the real value of the minimum wage and increase earnings of low-paid workers without causing considerable negative effects in terms of employment. RMWs now have a better correspondence with regional costs of living. Additionally, the minimum wage increases led to substantial compression of the earnings distribution which is notoriously high in Russia.

The assessment of institutional changes is more problematic. The system of minimum wage setting has become more flexible. Given the lack of a tradition of collective bargaining over the minimum wage at the regional level, it is amazing that there are only a few regions which can ‘afford’ a regional sub-minimum but do not have one. The reform contributed to the strengthening of social partnership at the regional level. However, peak trade union organisations seem to have little confidence in collective bargaining in the regions and continue to campaign for further substantial increases in the rate of the FMW. Surprisingly, the decentralisation reform did not cause an increase in the regional variation of minimum wages. In fact, the variation in the regional sub-minima is lower than it used to be before the reform, but is trending towards an increase. This may reflect the fact that variation induced by the regional coefficients was excessive for the most remote regions. Additionally, time is probably needed for social partners at the regional level to find the balance between conflicting interests of the parties.

Co-existence of different minimum wages reduces the regulatory transparency and complicates enforcement. The system of minimum wage setting has the advantage of increased flexibility that, however, is associated with greater complexity and higher demands for the capacity of both government and non-governmental institutions. Complex wage structures are effective in OECD countries because they are based on institutions that allow for appropriate wage setting, proper evaluation and effective enforcement. The design of the 2007 reform completely overlooked these issues. The major challenge in coming years is to strengthen the institutions of collective bargaining, introduce evidence-based evaluation and boost the capacities of government and trade union monitoring agencies.

Funding

This work is supported by the Basic Research Programme of the National Research University – Higher School of Economics.