Meet Blanche. She is contaminated. Cuban choreographer Marianela Boán can explain. She considers her solo Blanche Dubois (1999) to epitomize her concept: “danza contaminada” (contaminated dance) (Boán Reference Boán2021).Footnote 1 Boán saw contaminated dance as a hybrid in both form and cultural references. Formally, Blanche Dubois mixed dance and theater. Culturally, Blanche Dubois drew inspiration from Cuban and US cultures, as Boán's Cuban Blanche referenced aspects of the eponymous character from Tennessee Williams's play, A Streetcar Named Desire. Along with Boán's contaminated hybridity, Blanche nods to “contamination” in the sense posited by anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing: contamination happens because of “histories of transformative ruin” (2015, 29). Forces like imperialism and capitalism shrink the globe, devastate lives, and bring far-flung people into close encounters. According to Tsing, humans cannot escape contamination in this world of endless entanglement: “Everyone carries a history of contamination; purity is not an option” (2015, 27). Indeed, the Cuban modern dance world, which Boán and her contaminada Blanche Dubois were a part of, was also contaminated in the Tsing sense. Cuban modern dance is contaminated by colonial legacies, as are all national dance traditions. In fact, we are all implicated in these heavy histories. In some respects, we are all Blanche.

This article grapples with examples like Boán's Blanche Dubois that evidence US contamination in Cuban modern dance. I have chosen to focus on US influences rather than other equally (if not more) important foreign contaminants because it allows me to wrestle with a paradox: Cuban modern dancers and their scholars cite and continue to honor several white US dancers as forebearers in their nationalistic, anti-imperialistic, and anti-racist dance tradition that emerged in the heady months after the 1959 Cuban Revolution led by Fidel Castro and his 26th of July Movement. More specifically, Cuban choreographer Ramiro Guerra founded the first state-supported professional modern dance company. Closely tied to the company, a department of the National School of Art (Escuela Nacional de Arte, ENA) began teaching aspiring students modern dance techniques in 1965. After years of cross-generational collaboration in repertory and training, what became known as the técnica cubana de danza moderna (Cuban technique of modern dance) emerged as a valued nationalistic production, yet contaminants from the imperialistic United States continued to partially define técnica cubana. For instance, Cuban scholar Fidel Pajares Santiesteban describes the Cuban technique of modern dance as a “hybrid” that grew from Guerra's efforts to “internationalize our dance” by combining “the essence of the vanguard techniques of the era of Graham, Humphrey-Weidman, Limón, etc., with the essence of the [Cuban] dances of African origin” (2005, 15). This hybridity was cultural and racial. North American (or European) influences stood in for whiteness, while Blackness remained local, rooted in Afro-Cuban popular culture. Cuban modern dance, then, reflected national mythologies about European- and African-descended people harmoniously intermingling and producing a hybrid culture and body politic (de la Fuente Reference de la Fuente2001; Lane Reference Lane2005; Blanco Borelli Reference Blanco Borelli2016). Racial mixture, which informed repertory and a renovated technique, ostensibly made Cuban modern dance national and anti-racist, effectively overwhelming residues of US (and other foreign) contaminants.

Despite these ideals of nationalistic purity, every técnica cubana class points to historic contamination given that two staple exercises are named after US innovators (Anna Sokolow and Merce Cunningham). As I took and observed these classes for over a decade, I wondered and worried about the tricky politics of analyzing the topic. Scholars have adeptly written about the diverse and curious ways that people have danced with nationalist and cosmopolitan yearnings in concert dance in the Global South (Reynoso Reference Reynoso2014, Reference Reynoso, Ross and Lindgren2015; Manning Reference Manning and Dodds2019; Fortuna Reference Fortuna2019; Wilcox Reference Wilcox, Morris and Nicholas2017; Cadús Reference Cadús2018). However, focusing on US contaminants in a Cold War flash point like Cuba—especially as a white, cisgender, settler gringa living and writing in the belly of the beast—is fraught. I watch my step to avoid two narrative ruts: unfairly centering US dancers at Cubans’ expense, suggesting Cuban passivity in the face of foreign menaces, or concluding that Cubans heroically defied imperialism with a nationalist hybrid, suggesting Cuban mastery over foreign menaces.Footnote 2 The former is rooted in and bolsters US imperialism, whereas the latter is rooted in and bolsters official narratives that legitimate the Cuban state's authoritarian power (for examples of the latter, see Burdsall Reference Burdsall2001; Pajares Santiesteban Reference Pajares Santiesteban1993, Reference Pajares Santiesteban2005, Reference Pajares Santiesteban2011; John Reference John2012). Although dipoles, these renderings similarly flatten complex encounters, theorizations, pedagogies, and performances.

I offer contamination as a way out of trite traps, and as a way in to a complicated and, perhaps, uncomfortable topic. Such a metaphor moves away from two-dimensional struggles with hegemonic US culture acting as a homogenizing force or a vanquished one. Following US contaminants actually shows anything but Cuban passivity, as choreographers cleverly handled diverse influences to innovate dances more than the sum of their parts. Boán's danza contaminada provides a vivid example. Contamination is also useful because it connotes stink. I look beyond Cuban successes to the shadowy reaches of stylistic impurity, structural racism, historiographic neglect, revolutionary disaffection, and failure in Cuban modern dance history. In doing so, I build on trailblazing scholarship that exposes histories of racism, colonialism, precarity, and dispossession in US concert dance (Gottschild Reference Gottschild1996; Srinivasan Reference Srinivasan2012; DeFrantz Reference DeFrantz2004; Manning Reference Manning2004; Kraut Reference Kraut2016; Chaleff Reference Chaleff2018; Stanger Reference Stanger2021) to show how resonant dynamics plagued modern dance in revolutionary Cuba. Indeed, unearthing US contaminants reveals unpleasant realities that official and sympathetic histories of Cuban modern dance have left out and that memoir (namely Guillermoprieto Reference Guillermoprieto and Allen2006) and choreography (for instance, Boán's work discussed here) have insinuated. Seeing the regrettable does not discount beauty and achievement. It does provide a fuller picture of the past. Contamination allows me to underscore the foul realities that oozed from this history and its telling. This inescapable funk surrounds them and me.

The following analysis unfolds in three sections. The first quite simply shows that US contamination of Cuban modern dance happened. Although the United States has actively worked to isolate Cuba economically, politically, and culturally since 1959, modern dance has breached that divide, contaminating over and over, through a process of indeterminate encounter and translation.Footnote 3 To highlight this contamination is to challenge politicized claims by Cuban dancers and their scholars about pure national essences embodied by modern dance on the island. The second section examines how, despite the best intentions, Cuban modern dancers could not escape the racist underpinnings of the US modern dance that they internalized.Footnote 4 A noxious mixture of foreign and local prejudices informed decisions to embrace select white US modern dance pioneers, including Isadora Duncan, Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Anna Sokolow, and Merce Cunningham, while overlooking eloquent African American innovators like Pearl Primus, Katherine Dunham, and Alvin Ailey, who had ties to Cuba and Cuban modern dance leaders. Choices about who to recognize and who to ignore in a national dance origin story and canon unintentionally remapped colonialist logics in Cuban modern dance. Finally, in the third section, I discuss three performances that do not fit into conventional narratives of revolutionary inclusion, fervor, and triumph. These examples reckon with the historiographic neglect of notable teachers and exiles, revolutionary disaffection and unintentional whitening in Cuban choreography, and negative critical reviews of Cubans dancing US originated styles. I offer no tidy conclusions. My humble hope is that others can run with the loose ends as part of a larger conversation. While leaving many questions unresolved, the three sections come together to show that dance contaminants tenaciously glided through and across the US embargo and perpetuated “histories of transformative ruin” despite Cuban dancers’ commitments to the contrary (Tsing Reference Tsing2015, 29).

Before diving in, I want to quickly address the issue of language. When Guerra founded his company in 1959, it had modern dance in the title (briefly as a department and then as the National Ensemble of Modern Dance [Conjunto Nacional de Danza Moderna]) until 1974. Around that time, the company began calling itself Danza Nacional de Cuba (National Dance [Company] of Cuba). Boán, then a young company member, wrote an essay about the rebranding, noting that “modern dance” referenced foreign European and US rebels seeking new modes of dance expression in the first half of the twentieth century, whereas “national dance” in the new name accurately indicated the successful development of “our dance” (Boán Reference Boán1975, 29; this resembles shifts in Buenos Aires, as explained in Fortuna Reference Fortuna2019, 10–12). In the early 1980s, a younger generation of choreographers, including Boán, rejected the obsession with lo nacional (the national) rooted in mestizaje (miscegenation). This approach seemed out-of-date, unnecessarily defensive (Cuba had already proven its modern dance capacity), and, worst of all, not cosmopolitan enough. Another name change followed. The company Guerra founded in 1959 became Danza Contemporánea de Cuba (Contemporary Dance [Company] of Cuba) in the early 1980s. To this day, the cosmopolitan tendencies, and the associated term “contemporary dance,” remain. However, these linguistic adjustments were never absolute. Modern dance persists in the term técnica cubana de danza moderna, which refers to the standard daily technique class for Cuban contemporary dance students and professionals to this day. In using modern dance in the title, I point to the 1960s through the mid-1970s, when the term took on meaning at the professional level, and to the ongoing use of the term to label Cuban approaches to dance training. Furthermore, as I show in the final section of this article, when I wander into the late 1990s and 2010s, the legacies of contamination in Cuba modern dance underpin and help to explain Cuban contemporary dances of the more recent past.

Continual Contamination: US Dance in Cuba

If you begin looking for US contamination in Cuban modern dance histories, it seems to pop up everywhere and constantly. Dancing US expats, visitors, and films, as well as visiting Mexicans and Cubans trained in US techniques, sustained regular Cuban encounters with US modern dance. This directly challenges conventional wisdom. For instance, Cuban dancer Víctor Cuéllar told an interviewer in 1978 that Cuban modern dance had benefited from isolation caused by “el bloqueo” (the blockade, that is, the punitive embargo that the US government implemented in the early 1960s as relations soured and formally ended with Cuba). “Being blockaded,” he reflected, “we have had to go directly to our sources, to our roots, and that has allowed us to find and identify ourselves more clearly with the true elements of our nationality” (Fernández Reference Fernández1978, 60, 61). US scholar Suki John resonantly wrote, “For many decades Cuban dance artists have had almost no contact with North American dance” (Reference John2012, 96). With all due respect to Cuéllar and John, this section shows the opposite to be true. Cubans regularly interacted with US modern dance after 1959, and this continual contamination (rather than supposed isolated purity) helped to foment a national modern dance technique that reflected Cuban cultural values.

Nothing comes from nowhere; for example, connections, dance and otherwise, tied Cuba and the United States before 1959 (Pérez Reference Pérez2012). US dancers, including Ruth Page in 1932 and 1940, Martha Graham in 1941, and Ted Shawn in 1943, stopped in Havana during performance tours (Lastra Reference Lastra1985). In 1945, Ramiro Guerra stumbled upon an exhibition of Barbara Morgan's photographs of Martha Graham in Havana. He had been taking ballet classes with Cuban Alberto Alonso and Russian Nina Verchinina, who had ended up in Havana on tour with Colonel de Basil's Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo. He later recalled how the photo exhibit of Graham touched him: “I was dazzled and I said to myself: ‘this is what I need, but how I will get there, I do not know’” (Rivero Reference Rivero1985, 52–53; quote on 53). Luckily, Guerra soon found a path to the dazzling Graham. Through Verchinina, he joined the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo's tour to Brazil and New York. In 1946, the company ended up dissolving in New York, and Guerra decided to stay for a while. Guerra cited his study of Graham technique as the “most profound” (Pajares Santiesteban Reference Pajares Santiesteban2005, 25), but he also trained with Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman, and José Limón. In 1948, a contaminated Guerra returned to Havana, where he would draw on muscle memories and continue encountering US dancers, but now in Cuba.

For instance, US expat Lorna Burdsall moved to Cuba in 1955 and lived there until her death in 2010, contaminating Cuban modern dance over many decades. In the 1940s and 1950s, Burdsall attended the American Dance Festival at Connecticut College, where she trained with Martha Graham, José Limón, Doris Humphrey, Merce Cunningham, Louis Horst, William Bales, Sophie Maslow, Jane Dudley, Pauline Koner, Yuriko Amemiya, and Robert Cohan, among others (Burdsall Reference Burdsall2001, 32). She had also performed with Pearl Primus during a research trip to Trinidad and Tobago in 1953 and had taken postgraduate modern dance courses at Juilliard in New York in 1953 and 1954 (Burdsall Reference Burdsall2001, 8, 40–42). After meeting and marrying Manuel Piñeiro, a young Cuban student at Columbia University, she accompanied him to Cuba. In 1959, Burdsall successfully auditioned for Guerra's company, where she performed, taught classes presumably based on her US training, and mounted Doris Humphrey's early works, Water Study (1928) and Life of the Bee (1929), for the company premiere in 1960 (Sánchez León Reference Sánchez León2001, 289–90). Beyond her work with professional dancers, Burdsall contaminated younger students as she taught at ENA and developed dance curricula for schools across the island (Burdsall Reference Burdsall1974b; Reference Burdsall2001, 159). Humphrey's works—and notably, not those by Pearl Primus—became Burdsall's regular pedagogical tools. “Yes, I'm mounting it again!” Burdsall admitted to her mother about Life of the Bee in 1977 (Burdsall Reference Burdsall1977b; also discussed in Burdsall Reference Burdsall1971, Reference Burdsall1974a; Manings Reference Manings1984). Burdsall also mentions using Humphrey's book The Art of Making Dances to inspire students in 1981, for instance (Burdsall Reference Burdsall2001, 184). Along with propagating US choreography and choreographic approaches, Burdsall followed the US dance scene by having her family members send her the latest copies of Dance Magazine and Dance Perspectives, which she subscribed to for decades (for instance, Burdsall Reference Burdsall1976a).Footnote 5 Burdsall contaminated by sharing lessons garnered from her engagement with past and ongoing US technical developments.

Another US expat, Elfriede Mahler, worked in Cuban dance from 1960 until her death in 1998. She contaminated Cuban dancers with her US training and by recruiting US dancers to teach for fixed terms in 1970 and 1984. Mahler had trained in modern dance with a student of Isadora Duncan, as well as with Doris Humphrey, José Limón, Martha Graham, and Louis Horst. She also worked with Alwin Nikolais's company before visiting Cuba in 1960 and staying indefinitely (Velázquez Carcassés Reference Velázquez Carcassés1995, 7–8, 13). Like Burdsall, she became a formative figure in Cuban dance, working with Guerra's company in the early 1960s, teaching nonprofessional dancers in the eastern cities of Santiago de Cuba and Guantánamo, and directing ENA for a period of time (Veitia Guerra Reference Veitia Guerra1992, 24; Velázquez Carcassés Reference Velázquez Carcassés1995, 19, 40; Triguero Tamayo Reference Triguero Tamayo2015, 196). Mahler also brought New York–based dancers Muriel Manings, of the New Dance Group, and Alma Guillermoprieto, who was working with Twyla Tharp and training with Merce Cunningham, to teach at ENA in 1970 (Guillermoprieto Reference Guillermoprieto and Allen2006; Manings Reference Manings1970). Manings would return in 1984 to teach some classes in Guantánamo, and in her honor, Mahler's students performed the choreography Fire and Water that Manings had staged in 1970. It had “changed but [the] outline [was] there,” Manings (Reference Manings1984) recorded with delight. Thus, Mahler extended contamination beyond her singular offerings, perhaps knowing that traces of passing encounters with guest US teachers Manings and Guillermoprieto would linger and take on new forms after they left.

Without a doubt, short visits by US dancers contaminated. In 1969, Morris Donaldson staged three works about racial violence and social inequality in the United States, becoming the first Black US choreographer to set work on a Cuban modern dance company and remaining the only one until Ronald K. Brown in 2013 (for more, see Schwall Reference Schwall2021b). Longtime Graham dancer, Yuriko Amemiya, taught classes in Havana, probably in 1974 (Alonso, Reference Alonson.d.). Alvin Ailey visited Cuba in 1978 and left three videotapes, which included repertory from Martha Graham and Twyla Tharp (Burdsall Reference Burdsall1978). Anna Sokolow visited Havana in 1981 (Así Somos 1990), and two years later, the Danza Nacional de Cuba performed Sokolow's La jaula y el estanque (The Cage and the Pond), a four-minute fragment from a larger work titled Escenas en el parque de Nueva York (Scenes in the Park of New York) (Repertorio general ilustrado 2011). As this cursory listing shows, every couple of years a US dancer was teaching, sharing materials, observing, or choreographing in Cuba, allowing diverse US dance contaminants to layer on top of the presence of Graham via Guerra, Burdsall, Mahler, Manings, and Guillermoprieto.

Contamination spurred a process of translation. Havana publishers produced Spanish versions of Doris Humphrey's The Art of Making Dances in 1962 and Louis Horst's Pre-Classical Dance Forms in 1971 (Hernández Reference Hernández1982, 119). Selections by Limón, Graham, Walter Terry, and voice-overs in the Graham film A Dancer's World appeared in an informal 1970 typewritten compilation (La Escuela de Danza Moderna 1970). Translation was also about adapting US movement practices that felt foreign. Guerra reflected on this process most rigorously over the years, thinking about how he felt drawn to and disoriented by Graham:

When I began to study the Graham technique, I had to put my body in another frequency. Although I had adequate physical preparation, I had to rearrange my posture and … the placement of my arms and hands. Moreover, my relationship with space was completely different. It was not like moving in it, but facing it, transcending it, and taking possession of it. Barre work was not very extensive, but floor work was. That section of class was extremely difficult for me. (quoted in Pajares Santiesteban Reference Pajares Santiesteban1993, 47)

Even though Graham classes pushed Guerra to reconfigure his body and its relationship with space, he also jettisoned elements of the technique. As he later shared, “When I left a class, I thought intensely on what had been assimilated or not, and how to adapt it to fit my own sensibility [sentir]” (quoted in Pajares Santiesteban Reference Pajares Santiesteban1993, 48). Guerra was wary of, but willing to wrestle with, the foreign; and, assimilation, like contamination, involved active decision-making. Like rearranging English words and phrases to make sense in a Spanish translation, Guerra and his fellow Cuban collaborators used their bodies to process US contaminants until they began to feel right. In short, contamination involved indeterminate degrees of translation based on individual sensibilities and tapping into the ineffable qualities of fit and feel.

Translation also involved taking creative liberties and imagining the Cuban despite and through US contaminants. None other than Isadora Duncan allows us to see this process in action. Despite Duncan's US origins and elitist and racist aesthetics (for instance, Duncan contrasted her Greek-inspired moves to those of “African primitives,” as discussed in Daly Reference Daly2002, 16), Cuban critics, choreographers, and dancers remade Duncan in Cuba's revolutionary image. This process began in the years immediately following the 1959 revolution. In the press, Cubans described Duncan as “rebellious and iconoclastic” (González del Valle Reference González del Valle1964, 4). They admired how she “broke with all romantic conventionalism of tutus, pointe shoes, stories of swans and sylphs, and virtuosity alien to the pure expression of artistic emotions” (Guerra Reference Guerra1959b, 14). One commentator noted that Cuba and Duncan shared rebelliousness: in 1895, the same year that Cuba began its final war for independence against Spain, the dancer rejected the “asphyxiating bourgeois mentality” in her San Francisco home and eventually “created a dance movement of extraordinary liberty and vigor” (Casey Reference Casey1963, 37). Also admired by Cuban commentators, Duncan reportedly “‘discovered’ the spirit of the Nation in dance” (de la Torriente Reference de la Torriente1960, 75). Duncan's rejection of ballet and capitalist bourgeois culture, as well as her promotion of a vigorous, free modern dance that captured national essences, aligned with the political and artistic goals of revolutionary Cuba.

A Cuban rendition of Duncan took on theatrical proportions with the 1978 premiere of Isadora, Jesús López's solo for Isabel Blanco about the historic iconoclast. López studied sketches of Duncan, her writings, photographs, testimonies, and the film Isadora (1968), starring Vanessa Redgrave (Alonso Reference Alonso1978, 4). The Cuban dance production Isadora had three parts that depicted a global and almost timeless artist. The first section focused on how she drew inspiration from ancient Greece; the second section staged her dances about “water, air, pleasure, [and] love”; and the third section featured her before a red flag, a “symbol of the proletariat with which she danced in Moscow” (López Reference López1978). Lenin reportedly attended her historic performance, which involved the dancer moving to the grandiose sounds of “The Internationale.” A Cuban review explained that the Soviets had promised her resources to create a school, “and it is precisely the image of that commitment that closes the work” (Carrera Reference Carrera1978, 17). In the 1970s, the Cuban-Soviet relationship reached new heights in terms of closer economic and political collaboration, and Isadora reflected this camaraderie by leaving audiences with the impression that the historic dancer was a consummate Soviet ally (Mesa-Lago Reference Mesa-Lago1978, 10–29; for more on Duncan's complex relationship with the Soviet Union, see Daly Reference Daly2002, 197–204). The piece reconfigured a US-born modern dancer into “a revolutionary and social fighter” (López Reference López1978), meaning a committed communist and Soviet ally who inspired rebel art, just like Cuba after 1959. Even the movement vocabulary had Cuban accents. As one reviewer described it: “The movements and poses alternate between hip insinuations as Ramiro Guerra liked … always based on the graphic testimonies that remain from Duncan” (Carrera Reference Carrera1978, 17). A Cubanized Duncan shows how contamination worked both ways. The North American may have intervened in Cuban imaginaries, but Cubans took liberties in remaking the individual in their own image.

US contamination acted like a constant drip into Cuban wellsprings even after 1959. Picture a cup of this metaphoric contaminated water. It would be impossible to discern from where one drop originated. The murky mix takes on new hues, smells, and consistencies. As a result, a thin, flowing liquid may become thick and viscous or vice versa. That is to say, the actual movement of the water changes with contamination. Same with contaminated dance. Cuban modern dance flowed differently as a result of encounters with Duncan, Graham, Humphrey, Weidman, Limón, Cunningham, Burdsall, Mahler, Donaldson, Manings, Guillermoprieto, Sokolow, Ailey, and others, just as these US dancers undoubtedly moved in new directions as a result of their experiences with other cultures. The process of translating US sources for Cuban audiences involved concerted efforts to integrate particular political and cultural ideals, as Isadora showed. This curatorial process also manifests in the técnica cubana class, a living, breathing archive that I now look to.

Curating Contamination: “Sokolow” and “Merce” instead of “Dunham” and “Alvin”

During the seven years I intermittently spent in Cuba conducting archival research, I took as many técnica cubana classes as possible. I was always struck when the teacher yelled out “Sokolow,” and a bit later in class, “Merce,” to begin sequences inspired by their namesakes Anna Sokolow and Merce Cunningham. These exercises at least existed as early as the mid-1970s, based on photographic and filmic evidence.Footnote 6 How did the exercises get there, why did they stick, and what do they tell us about Cuban modern dance histories? I see the technique as a crucial archive of information, in line with what scholar Judith Hamera has argued. She writes, “The voices of and in technique are not only those of the here and now; they are also those of the there and then” (Hamera Reference Hamera2011, 7). This framing helped me realize that my approach to official paper archives—attention to what was left out as much as to what was left in—needed to be applied to técnica cubana. All archives are selective. What shows up in an archive has a direct relationship with the amount of power that the creator of the document or gesture possessed (Hartman Reference Hartman2008). For example, técnica cubana archives Cuban interest in the white US choreographers Sokolow and Cunningham. It is no accident that these exercises appear, instead of any called “Dunham” and “Alvin” after the Black US choreographers Katherine Dunham and Alvin Ailey, for instance, who had connections to the island. The técnica cubana archive evidences a curated contamination that effectively remapped racialized citation and erasure in line with what happened in US modern dance.

To understand why key exercises in técnica cubana were named “Sokolow” and “Merce,” it is helpful to revisit the writings of Ramiro Guerra, particularly when he discussed how the Cuban modern dance style and technique needed to reflect a nationally mythologized racial mixture. Toward this end, Guerra believed that Cuban modern dance depended on the contributions of African-descended dancers in collaboration with white dancers. Right before auditions for his new company, Guerra opined that crucial to “creating dance with national expression is the direct intervention of individuals of the black and mestiza [mixed] race” (Reference Guerra1959a, 11). Put slightly differently, he declared in an interview, “A national dance … must contemplate racial integration. Between whites, mulatos, and blacks emerge unexpected nuances of our dance's characteristic movements” (Arrufat Reference Arrufat1960, 15). To realize this fruitful exchange, Guerra created a group “formed by the three colors of our nationality. Whites, blacks and mulatos” (quoted in Sánchez León Reference Sánchez León2001, 232). Diverse modern dancers became a collective embodiment of Cuba's national identity predicated on ideals of a conflict-free racial mixture as well as newer revolutionary anti-racist aspirations (de la Fuente Reference de la Fuente2001).

Although Guerra never explicitly defined US modern dance as an expression of whiteness, he implied this racialization when discussing how North American movement vocabularies imperfectly “fit” Cuban bodies, which ostensibly bore the genetic or cultural imprint of Blackness. Speaking from his own experience, Guerra claimed, “When I studied in the United States, I noted that my body responded with a different movement.… The Cuban as a body [cubano como cuerpo] seeks gravity. Black dance, for example, is one of disintegration” (Arrufat Reference Arrufat1960, 15). Although Guerra does not further explain this “disintegration,” he presumably refers to a weighted, grounded quality typical of African diasporic dances, which differed from the more angular extremes of the white Graham technique (Gottschild Reference Gottschild1996, 8; Manning Reference Manning2004, 115–42). Elsewhere, he more explicitly described using “foreign techniques” as the first step in a complex process that involved figuring out

how to express … a sense of “national dance,” a search, to create a style, a way of moving according to the ethnic circumstances of our nationality, with a body that has to do with mestizaje [miscegenation], with a body that has a lot to do with black, with white, which has received the genetic influence of the African, as well as that of the Spanish and has, at the same time, a way of combining both forms; with a definitely rhythmic body, very given to a special type of relaxation and concentration to form a way and a style of movement. (quoted in Pajares Santiesteban Reference Pajares Santiesteban2005, 30)

From his white Cuban body, Guerra intuited movement patterns different from those of his white US counterparts because of the Afro-Cuban culture that he believed all citizens, regardless of racial background, internalized to some degree. In these discourses, Guerra essentialized and subsumed racial differences into a generic Cuban body. This transformed African-descended dance and dancers into tools for building a national dance project and elided historic and ongoing racial inequalities in Cuba (resonant with what happened with Cuban folkloric dance, as discussed in Berry Reference Berry2010). Also true, his ideas developed relationally and transnationally. That is, through encounters with US modern dancers, he realized the possibilities of creating national dance that celebrated “the Cuban as a body,” which ostensibly sprang from a combination of Black African and white Spanish patrimony.

Given the significance of African diasporic cultures in técnica cubana, trailblazing choreographers like Katherine Dunham and Alvin Ailey, who explored Blackness in critically acclaimed concert dance productions, seem like natural interlocutors. Indeed, championing Dunham and Ailey by drawing upon their technical and choreographic innovations would have continued and extended Guerra's activities in Cuba. More precisely, Guerra encouraged talented African-descended principal dancers in his company, like Eduardo Rivero, to choreograph (Pérez León Reference Pérez León1986, 24). Arguably, Guerra, Rivero, and other Cuban choreographers, along with Dunham and Ailey, similarly excavated “the Africanist presence” that already existed in US modern dance techniques like Graham's, as Brenda Dixon Gottschild (Reference Gottschild1996) has compellingly shown.Footnote 7 As a result, it seems reasonable to imagine Cuban modern dancers viewing Dunham and Ailey as comrades in a struggle to honor Black culture in and through modern dance.

Besides resonant dance projects, Dunham and Ailey had concrete connections to Cuba. Dunham visited Cuba several times in the 1940s and 1950s, befriending Fernando Ortiz and Lydia Cabrera, two Cuban anthropologists and specialists in Afro-Cuban culture. During these trips, Dunham scouted for Cuban musicians to play for her company and tried, albeit ultimately unsuccessfully, to arrange a performance tour stop in Havana (Dunham Reference Dunham1955 [1956]).Footnote 8 Two Afro-Cuban dancers, one who later danced in Guerra's company, had their professional concert dance start with Dunham (discussed further in Schwall Reference Schwall2021a, 55–65). Ailey, meanwhile, forged post-1959 connections, meeting and dining with Burdsall in 1976 (when they overlapped at an international festival in Spain), planning a trip in 1977 (though visa trouble meant only his executive director, Ed Lander, could view a showing by Danza Nacional de Cuba), and visiting Cuba in 1978 (Burdsall Reference Burdsall1976b, Reference Burdsall1977a, Reference Burdsall1978). Also in 1978, principal dancer Judith Jamison performed Ailey's Cry in Havana as part of the biennial International Ballet Festival (González Freire Reference González Freire1978). Thus, Dunham and Ailey had more direct and ongoing connections with Cuba than the warmly embraced “Merce” (Cunningham), for instance, who never visited or showed his work on the island during his lifetime, as far as I can tell.Footnote 9

Connection with and contamination by Dunham and Ailey may have happened, but such encounters remained uncited. I can only hypothesize an explanation. I wonder if Guerra and other Cuban creators dismissed Dunham and Ailey as staging productions that focused entirely on African diasporic culture. As Guerra made clear, Cuban modern dance diversity must have a mix of Blackness and whiteness, or else it becomes foreign. Just as Graham did not “fit,” perhaps for feeling too entirely white, Dunham and Ailey may have appeared too entirely Black. However, Graham is referenced repeatedly, and Dunham and Ailey not at all. It is possible that, as Afro-Cuban culture became a metonym for “Cubanness” and distinguished modern dance on the island from US and other foreign varieties, US Blackness threatened to undermine national essences. In other words, the equation that Cubans developed for técnica cubana allowed for importing US whiteness embodied by the likes of Sokolow and Cunningham, but not the US Blackness staged by Dunham and Ailey.Footnote 10 Also, assumedly, Cuban modern dancers must have adhered to the racialization of modern dance as white and distinct from the racially and ethnically marked “Negro Dance” (Manning Reference Manning2004). To create Cuban modern dance, Guerra and others looked to US modern dancers, not those labeled as something else, like Dunham. As these explanations reveal, racism and exclusion in US concert dance also contaminated Cuban modern dance. Cuba, of course, had local forms of prejudice, but anti-Black racism was reiterated through a transnational dialogue about modern dance. Ultimately, Cuban modern dancers missed out by not embracing intercultural connections with Dunham and Ailey.

Although Dunham and Ailey did not leave a mark, or at least not a cited one, Anna Sokolow did. How and why? Mexican colleagues and eventually Sokolow herself likely brought elements of “Sokolow” to Cuba. Starting in 1939 and through the 1980s, Sokolow spent considerable time in Mexico, performing, directing a short-lived company, teaching, and choreographing (Kosstrin Reference Kosstrin2017, 85–156). One of her former students, Elena Noriega, went on to play a “decisive” role in Cuban modern dance, bringing her considerable training with Sokolow (quote in Alonso Reference Alonso1984, 46; on Noriega as Sokolow's student, see Kosstrin Reference Kosstrin2017, 155). Burdsall recalled about Noriega, “She applied many of Anna's principles, but the results she achieved reflected her own personality and her strong support for the Cuban Revolution” (Reference Burdsall2001, 159). According to Guerra, Noriega helped Cuban modern dancers systematize their technique and fuse different influences (Pajares Santiesteban Reference Pajares Santiesteban2005, 26; Reference Pajares Santiesteban2011, 28). In addition to this secondhand encounter with Sokolow through Noriega, the choreographer herself visited the island in the 1980s. The trip hinted at Sokolow's revolutionary politics, which as scholar Hannah Kosstrin convincingly argues, involved “communist coalitions [that] underwrote her political personhood” and her art (2017, x). This investment in revolutionary causes allowed Sokolow to connect with postrevolutionary Mexican artists starting in 1939 and may have endeared her movement vocabulary to revolutionary Cuban modern dancers. Although I have not found Cuban discussions of Sokolow's politics or the appeal of her work, the fact that the “Sokolow” exercise persists in daily técnica cubana classes archives a kinesthetic clue as to how Cubans perceived the choreographer.

Looking at the movement itself, a dramatic sternum proves that Sokolow indeed contaminated Cuban modern dance. At the beginning of the “Sokolow” exercise, dancers melt into a demi plié, with their hands behind the small of their backs. As their hands push slowly downward, they stretch their legs, turn out their feet into first position, and throw their heads back and their sternums up. They then unleash their clasped hands and taut arms, which move through low curved bras bas to the high curved fifth position before bursting open, with gazes and sternums raised (“Danza Contemporánea de Cuba – 1” 2011).Footnote 11 Kosstrin (Reference Kosstrin2021) watched a representative clip of the Cuban “Sokolow” exercise and observed, “A specific upward thrust of the sternum at the beginning of each movement phrase strikes me as ‘Sokolow.’” A still image from her book on Sokolow shows a similar sternum thrust by dancers in Tel Aviv in 1954 (Kosstrin Reference Kosstrin2017, 192). Although arms and cultures differ considerably, Israeli and Cuban dancers have similarly released upward over the years, kinesthetically evidencing their shared contamination.

That leaves “Merce”: how the exercise got to Cuba and why it stuck. Like “Sokolow,” the precise origins of “Merce” remain something of a mystery; however, it is possible that in 1970, Alma Guillermoprieto brought the initial kernel of the exercise to Cuba. Guillermoprieto was training at Cunningham's studios when she was recruited to teach at ENA in 1970. In a memoir about her months in Havana, she described the challenge of teaching Cunningham technique to the Cuban students:

During class I stood in the center of the studio and tried to make the students see stillness … and it was futile. It made no sense to seek stillness in the middle of a Revolution, and the kids looked bored.… It was best to try to generate some enthusiasm by teaching them about the freedom of movement in the legs Merce gave, which Martha [Graham]'s exercises did not impart: the marvelous adagios, the swiftness in the feet, the impossible shifts in direction. Perhaps through these technical achievements the students would manage to grasp one of the essential qualities of Merce's work: its extreme modernity. For what else did the Revolution aspire to but the latest, most advanced, most perfect modernity? (Guillermoprieto Reference Guillermoprieto and Allen2006, 94)

Although stillness seemed incomprehensible in 1970, elements of Cunningham lingered in Cuba, as evidenced in “Merce.” I bet that Guerra fostered this contamination in no small part because he saw common cause with the New York counterpart. Guerra later claimed that he was like Cunningham because they both broke with their teacher, Graham, to find their own artistic voices (Pajares Santiesteban Reference Pajares Santiesteban2005, 29).

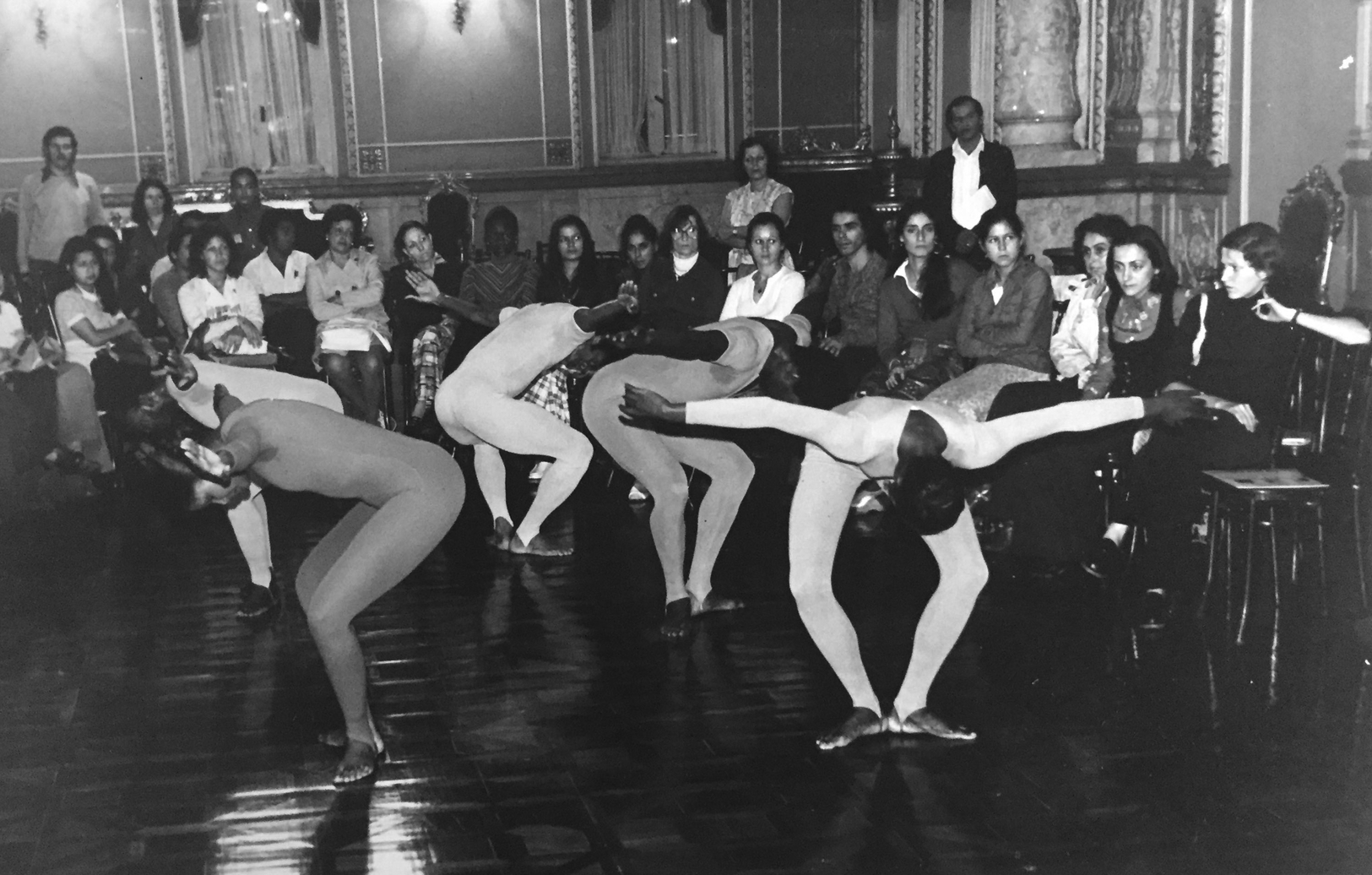

Like “Sokolow,” “Merce” holds kinesthetic clues that archive Cunningham's contamination of Cuban modern dance. Dancers begin by rotating their arms downward until their shoulders and upper backs slightly curve forward. They then transition to a tabletop position, with arms in a V shape above their heads. While pitched forward, they manipulate their upper backs and shoulders by rotating and curving up and inward (see photo 1), only to straighten their spine back out into a tabletop position. Eventually, upright once more, they lean to the left, bringing their arms into an S shape with the left arm curved and facing up, right arm curved and facing down, and gazing above the right shoulder. Continuing to articulate the back, they move to make the same S shape on the other side (“Danza Contemporánea de Cuba – 1” 2011). When I spoke with Guillermoprieto about what, if anything, invoked the namesake in a representative clip of “Merce,” she guessed that the dancers did a variation of “exercises on 6” (Merce Cunningham Trust 2015). The isolation of the upper back, the twists from one side to another, the inward rotation of the arms to bring the torso into a slight, hovering contraction, and the movement of the back from dropped down to upright indeed resonates with the Cuban “Merce.” Guillermoprieto (Reference Guillermoprieto2018) concluded, “What I love about seeing this is that it is so completely Cuban, but they call it ‘Merce,’ because what is ‘Merce’ is the isolation of the upper torso.” Cunningham's interest in the upper torso appears in Cuban modern dance by way of a contaminated “Merce.” The exercise archives encounters and translations across generations of Cuban students, teachers, and professionals.

Photo 1. Cuban dancers demonstrate técnica cubana exercises while visiting Costa Rica, probably in 1975. They are in the midst of “Merce,” manipulating their upper back while pitched forward. Photographer unknown. Archivo de Danza Contemporánea de Cuba, Teatro Nacional de Cuba, Havana, Cuba. Courtesy of Danza Contemporánea de Cuba.

Contamination was definitely curated, but the choices, people, and timing involved remain fuzzy. However, each time students in a técnica cubana class carry out the exercises “Sokolow” and “Merce,” they offer intriguing clues. Prompted by their movements, I hypothesize that US modern dance was coded as white in Cuba. Cubanizing these foreign contaminants meant integrating Afro-Cuban Blackness. By contrast, Cubans stayed away from US Blackness theorized and performed by Dunham, Ailey, and other African American choreographers. “Sokolow” and “Merce” do not necessarily cancel out the anti-racist objectives underpinning Cuban modern dance, but they certainly did not further such ideals. Contamination by Dunham and Ailey may have. Alas, I can only speculate.

Contaminated Performances: Incongruous Histories

Continuing in this speculative space, I draw attention to three performances, all around twenty years apart: Arnaldo Patterson's 1976 Elaboración técnica (Technical Elaboration), Marianela Boán's 1999 Blanche Dubois, and the Cuban company Malpaso's 2019 performance of Cunningham's Fielding Sixes. Each performance is contaminated and incongruous. Existing Cuban modern dance histories tend to highlight revolutionary inclusion, fervor, and triumph, and by contrast, these performances point to marginalization, disaffection, and disappointment. Teasing out US contamination in Cuban modern dance led me to these dissonant performances, only to discover that each offers a slightly different insight into what existing histories lack. The patchwork is patchy on purpose.Footnote 12 Rather than providing a comprehensive discussion of historical developments from 1976 to 2019, these contaminated performances offer snapshots, leaving large gaps for others to move around and beyond. I close with them because they made me wonder; they might strike others as well.

The first contaminated performance, Patterson's Elaboración técnica (Technical Elaboration) featured a theatricalization of Cuban modern dance technique. This undoubtedly drew inspiration from earlier works that brought class to the stage, including Mexican choreographer Elena Noriega's Técnica de un bailarín (Technique of a Dancer, 1964) and Ramiro Guerra's Ceremonial de la danza (Dance Ceremonial, 1969). I suspect that Graham's A Dancer's World (1957), a filmic meditation on daily training in the studio, factored into Noriega's, Guerra's, and then Patterson's staging of a stylized class for audiences.Footnote 13 Regardless, Patterson's thirty-minute Elaboración técnica was, according to one critic, “an exhibition of the interpretive possibilities of modern dance, from the elaborated inventions of Martha Graham to the incorporation of Afrocuban dance” (González Freire Reference González Freire1976, 25). Another article described it as exhibiting the “Cubanization of the Graham technique through dynamic, rhythmic, spatial changes and axial designs” (Burdsall Reference Burdsall1979, 12). Contamination was the point, as Patterson intentionally elaborated on an implicitly incomplete Graham by incorporating distinctly Cuban features.

Patterson conducted an assiduous “search for lo negro [Blackness], a fusion of lo negro with [modern] dance” (Borges and Maytín Reference Borges and Maytín2017). As one of the ten founding Black members of Guerra's company, he had the opportunity to play a formative role. The pelvis was key. As Boán, one of his students noted,

The Graham technique … propose[s] certain principles such as contraction, fall, relaxation, the motor center, etc. We accept the organicity of movement from a motor center, which in our case is the pelvic plexus and not the solar plexus. Our movement, especially the black influence, is marked by the presence of the pelvis, the hips. Ramiro Guerra and fundamentally Patterson have worked on this. (quoted in Pino Pichs Reference Pino Pichs1980, 20)

Patterson watched Cubans move through their daily lives. Using what his colleague Isidro Rolando described as extraordinarily expressive hands, Patterson choreographed moves inspired by Cubans’ highly gestural way of talking. Spirals also became very important, according to dancer Regla Salvent. A scene from Patterson's Elaboración técnica features Salvent enacting these spirals in a duet with Pablo Trujillo. They mirror each other in a twisted pose, bending one arm in front of themselves while reaching out with the other. Their upper bodies curve down as their heads hover above their folded arm. Adding to the sense of poised stretching, they stand on one leg with the other extended to match the arm reaching to the side (above based on footage in Borges and Maytín Reference Borges and Maytín2017). Salvent and Trujillo, like Patterson, are of African descent, and these dance makers demonstrated how elaborating Graham in Cuba meant making space for Cuban gestures, spirals, and Blackness.

Patterson's Elaboración técnica sparks questions about modern dance histories, which privilege choreographers rather than teachers and those who lived entirely in Cuba—a tendency not unique to Cuba. Patterson had become a highly venerated teacher whose classes served as “a base of all our work,” according to his student Rosario Cardenás (Alonso Reference Alonso1979). His methods continue to feel the “best” to professional modern dancers, according to company director Miguel Iglesias (Borges and Maytín Reference Borges and Maytín2017). However, Patterson has remained a shadowy figure in Cuban modern dance histories. African-descended choreographers like Eduardo Rivero and Víctor Cuéllar attract more attention. In 2017, scholar Mercedes Borges created a documentary about Patterson, implicitly acknowledging this gap by addressing it. Besides being mainly a pedagogue rather than a choreographer, Patterson migrated to Spain in 1981, choosing to stay while on tour with Danza Nacional de Cuba (Borges and Maytín Reference Borges and Maytín2017). High-profile defections were and are embarrassing for Cuba. This helps to explain why Patterson comes up less. However, what if Patterson came to mind first, or at least alongside prominent choreographers like Guerra or Rivero? What if those who study Graham obligatorily knew something about Patterson, who theorized an elaboration of her technique? I imagine that focusing on Patterson and other teachers, who do the sweaty work of translating to diverse students over decades, would provide crucial information about how modern dance developed transnationally on a daily basis as students and teachers co-created movement practices together.

Moving on to Boán's 1999 Blanche Dubois, featuring the eponymous protagonist that you already met. The premise is that Blanche stayed behind while family members fled Cuba, and she continued to cling to unraveling revolutionary ideals, similar to how the US Blanche retained her aristocratic air despite financial and moral hardship in Williams's play. Based on a 2002 performance of Blanche Dubois in Peru, the highly theatrical forty-two-minute solo uses dance, song, and spoken text to convey the emotional turmoil of Blanche as she vacillates between flirtatious and confident to anguished and insecure. Waving a flag and goose stepping, she looks absurd, even pitiful. At one point, Blanche clings to a certificate that awards her “outstanding work,” a common moral incentive (in lieu of material ones) handed out in socialist Cuba (Boán Reference Boán2002). On Boán's website, she claims Blanche Dubois “articulates the principles of ‘Contaminated Dance’ [Danza Contaminada] through … attention to details of voice, bodies, objects, and space … that becomes a true hybrid of dance and theater” (Boán Reference Boán2021). In the production, Boán used the tragic US Blanche to speak to Cuban experiences with ideological desperation. This Blanche is unseemly. She embodies contamination and disaffection instead of national purity and patriotism.

Where did this Blanche come from? Boán trained at ENA in técnica cubana and performed a repertory that shaped the technique during her early years in Danza Nacional de Cuba in the 1970s. However, she found the self-conscious determination to Cubanize foreign techniques through Blackness to be “rigid” (Pajares Santiesteban Reference Pajares Santiesteban2005, 97). Rather than relying on Afro-Cuban culture to convey nationality, she saw her training and interest in commenting on everyday Cuban experiences as enough. As she later put it, “I think my work is Cuban. One does not have to worry about being Cuban … because in fact it is” (quoted in Pajares Santiesteban Reference Pajares Santiesteban2005, 98). Boán's generational rebellion confirms that US contamination in Cuban modern dance, which prompted choreographers like Guerra and Patterson to Cubanize foreign techniques with Afro-Cuban influences, had been so thorough and complete as to become blasé. Ironically, the contaminated Cuban modern dance that had developed in previous decades became an expression of national stylistic purity that Boán rejected in favor of new forms of contamination.

Toward this end, Boán searched for language to articulate her objectives and landed on contamination, in part to push back against hegemonic labels. As she put it,

I cannot call myself a postmodern artist, because I do not live in the United States, or in Europe. I am not a typical artist of postmodernism… . I think that from Cuba, socialism, the Caribbean, that which is Latin America, one is nothing exactly… . I try to listen as much as possible to my environment and my individuality, to make my own experience, perhaps letting myself be stimulated by all that, modernism, postmodernism, the contemporaneity, to make art that in the end is nothing like that, but a series of things that none of these tendencies have… . Therefore, for me, postmodernism, what has been called contemporary, are names that do not belong to me. (quoted in Pajares Santiesteban Reference Pajares Santiesteban2005, 102)

Identifying the labels “postmodern” and “contemporary” with the United States and Europe, Boán invented a new term for her art: “I call it ‘contaminated dance.’ It is not a pure style, it can be mixed, it can assume, assimilate everything.” She acknowledged learning from “North American postmodern dance” as well as European trends but contended that she offered “a third point of view” due to her geographic location “from the Caribbean” (quoted in Pajares Santiesteban Reference Pajares Santiesteban2005, 177).

Boán's rejection of nationalist Cuban modern dance and US and European postmodern and contemporary dance, as well as her theorization of contaminated dance offers rich ground to explore. Boán, who is white, others in her generation, and those who came after have indeed moved away from searching for lo negro in Cuban modern dance. This ceases to instrumentalize Blackness in the service of nationalist projects; but, has this unintentionally enabled an implicit whitening of modern and contemporary dance in Cuba? Danza Contemporánea de Cuba tends to commission mostly foreign (white) choreographers, and the most prominent resident Cuban choreographers with the company also happen to be white.Footnote 14 Perhaps this shows how global exclusionary forces contaminate Cuban dance. Speaking of contamination, Boán welcomes the stink. Nothingness and omnivorous borrowing go from spineless to clever or even inevitable tactics. How does contamination, this “third point of view,” relate to notions of the postmodern or contemporary? What can we learn from Boán and other choreographers from the Caribbean about nationalism, individuality, race, exile, and generation in concert dance? What if scholars of US postmodern dance thought about Blanche Dubois as connected in contamination? I can only wonder what that might open up.

Last stop, Malpaso's 2019 performance of Cunningham's Fielding Sixes at the Joyce Theater in New York. Osnel Delgado and Daileidys Carrazana, both former members of Danza Contemporánea de Cuba, founded the company in 2012. Malpaso is an outlier for not receiving state funding and regularly performing in the United States. The relatively small size of the ensemble (eleven dancers) and institutional connections to the Joyce have allowed Malpaso to navigate bureaucratic hurdles still in place for Cuban travel to the United States.Footnote 15 This unique status facilitated bilateral encounters that resulted in the contaminated performance of Fielding Sixes. The work originally lasted twenty-eight minutes and premiered in 1980 with thirteen dancers. The version performed by Malpaso was a shortened rearrangement drawn from the first eleven minutes of the dance and set on eight dancers. Former Cunningham company member Jamie Scott staged the shortened version (Malpaso Dance Company 2018; “Cuba Festival” 2019). In December 2018, Scott went to Havana for two weeks to set Fielding Sixes. Each day, instead of Malpaso's typical warm-up, Scott gave a Cunningham technique class before several hours of building the piece. She taught all the phrases to everyone and then organized who performed what (Scott Reference Scott2019). Approximately four weeks later, the company performed Fielding Sixes at the Joyce. It was part of hundreds of events to celebrate Merce Cunningham's centennial from September 2018 through December 2019 (Merce Cunningham Trust 2019).

This process was a learning experience filled with convergences and divergences. According to Scott, the company already danced well as a unit and had strong rhythm, both of which are important for Cunningham repertory (Scott Reference Scott2019). Osnel Delgado saw some similarities between Cuban movement vocabularies and the Cunningham class and choreography, such as “the movement of the torso, [work] in the center, [and] the contraction” (Delgado Reference Delgado2019). Scott agreed. She took a técnica cubana class and found the technique more familiar than she expected, especially “in the use of torso,” making her feel that Cunningham was “actually not such a stretch for them” (Scott Reference Scott2019). However, there were undeniable differences. When I asked dancer Beatriz García (Reference García2019) about the relationship between “Merce” in standard técnica cubana classes and what they encountered while working with Scott, she laughed. With a bright smile, she reflected, “What they give in técnica moderna cubana, the ‘Merce’ exercise, has many Cuban elements. After taking a Merce technique [class] one realizes that [the Cuban ‘Merce’ exercise] is already contaminated with many Cuban things. [Laughs] Very, very contaminated” (García Reference García2019). Using language inadvertently resonant with Boán, García describes the Cuban “Merce” as undeniably different from the source, “contaminated” by Cuban bodies and cultures over the decades.

Watching the performance live, talking to the dancers backstage, and reading US reviews, I struggled to wrap my brain around this contaminated performance. Scions of técnica cubana performing Cunningham in New York felt big, but instead, I found shrugs. In particular, critic Brian Seibert dismissed Malpaso for lacking technical purity, since “they didn't have the clean coordinations [sic] and cool affect of Cunningham dancers—a peril of attempting a difficult and well-known style. Instead … they looked conscientious and proud, happy to be sharing their competence in a foreign tongue” (Reference Seibert2019). If only Seibert knew that Cunningham was not so foreign—it was encountered and translated in Cuba long ago—and this contaminated performance evidences a Cuban interpretation, valid for its difference.

This performance made me reflect on the enterprise of restaging canonic choreographers’ work. Cuban modern dancers created multiple Duncans, Grahams, Humphreys, Sokolows, and Cunninghams that existed and continue to exist well beyond sanctioned companies, trusts, licensed performances, legacy projects, and unsanctioned imitators in the United States (Yeoh Reference Yeoh2012; Van Camp Reference Van Camp2007; Lepecki Reference Lepecki2010, 40–44). Versions of these figures have danced in Cuba for decades and likely dance elsewhere as well. What can they tell us about the problems and possibilities of choreographic circulations and re-encounters, understandings of national style and cosmopolitan skill? What would happen if people like Seibert or anti-imperialist Cuban scholars appreciated the diversity of contamination rather than idolized stylistic purity of one type or another? Maybe a framework like contamination might offer ways of seeing dances for what they are and what they can be.

Parting Thoughts

Blanche started us off, and she returns before we part ways. Blanche Dubois was Boán's invention—a contaminated performance drawing upon US culture to create something else. The construct of Cubanness was there, I suppose, but why restrict choreographers to national boxes?Footnote 16 Boán herself has recently argued, “Now, as ever, my country is my body… . Our bodies are nations unto themselves, full of contradictions and silences” (Reference Boán2022). Refusing to worship national idols or be confined by national stereotypes, Boán sees each body as an autonomous, complex political entity.

Similarly blasting through national frameworks, Blanche Dubois sprang from a longer history of constant and curated US contamination in Cuban modern dance after 1959. This historical process shows how dancers stubbornly forage for useful ideas, even in the choreographic wreckage of people from an ideologically opposed bully. Contamination can be ugly, as seen in the racialization of modern dance as white and the privileging of white creators like Sokolow and Cunningham over Dunham and Ailey. Contamination is also messy and confusing. Pulling at the threads hanging off the edges of contaminated dances like Patterson's Elaboración técnica, Boán's Blanche Dubois, and Malpaso's Fielding Sixes results in more questions than answers.

Although leaving those questions unresolved, Blanche conveys an important final message of this article. In the beginning, she sits folded in half with her heeled feet propped up along the wall of a coffin-like box standing upright. As dramatic music plays, she awkwardly twitches in the box and bursts out of it with scrambles, slides, crawls, cowers, flops, and falls. We see the raw and frayed, unsightly and pathetic, in her from beginning to end (Boán Reference Boán2002). I find eloquence in this realness. Looking for the places where dancers flail and fail are a necessary addition to our stories of poise and excellence. Blanche is vulnerable, so very human. In some ways, we are all Blanche; dancing histories could dwell more on this shared damage and destructibility.