The United States is exceptional in the most peculiar way. Since the early 1970s, the American prison population has increased by more than 500 percent, and now the United States boasts the highest incarceration rates in the world.Footnote 2 The consequences of this carceral stateFootnote 3 are similarly peculiar. African Americans are incarcerated at nearly six times the rate of whites, and Hispanics are incarcerated at almost twice the rate of whites.Footnote 4 Additionally, the injurious effects of this peculiar institution are not confined to prisons but extend into the lives of millions of people: imprisonment shackles the future of ex-felons, undercuts the health of their families and life chances of their children, and diminishes their democratic voice and the political power of their communities.Footnote 5

While scholars have, with great vigor and precision, illuminated the effects of mass incarceration, the origins of the criminal justice policies that produced these outcomes remain unclear. Explanations certainly abound. Yet many obscure as much as they reveal—in great measure because they either ignore or minimize the consequences of crime. Emphasizing the exploitation of white fears, the construction of black criminality, or the political strategies of Republican political elites,Footnote 6 prevailing theories ignore the “invisible black victim.”Footnote 7 “Any discussion of the racialized nature of crime and punishment in the United States,” Lisa L. Miller insists, “must take account of the day-to-day violence that inheres in many black and Latino neighborhoods and the political mobilization of these communities for greater public safety.”Footnote 8 Based upon his analysis of homicide data from 1950 until 1980, Charles Murray concludes, “it was much more dangerous to be black in 1972 than it was in 1965, whereas it was not much more dangerous to be white.”Footnote 9 Hence, while racial disparities in imprisonment provide keen insight into aspects of the modern American carceral state, students of mass incarceration could gain additional insight into its origins by observing racial disparities in victimization and the politicization of crime within minority communities.

In order to excavate the historical roots of the modern carceral state, this study traces the development of New York State's Rockefeller drug laws. Heeding Miller's admonition and reflecting upon Murray's observation, this analysis does not focus primarily on the construction of white victimization or black criminality. While not ignoring these questions, this study examines how African American mobilization for greater public safety in Harlem shaped the evolution of narcotics-control policies in New York State from 1960 until 1973. First, I review backlash and “frontlash” explanations of crime policy development. I then formulate an alterative approach that emphasizes the unique class dynamics of black-on-black crime and the evolving political opportunities of white political elites. Then, I chronicle the politics of narcotics-control policy from the rehabilitation-focused Metcalf-Volker Law to the punitive Rockefeller drug laws, paying particular attention to how the indigenous construction of and mobilization around crime and crime-related problems in black communities influenced policy shifts. Next, I situate the Harlem experience within a broader context, documenting how black civic and political institutions and elites in other cities drew upon indigenous class categories to frame and negotiate their experiences with crime. Finally, I conclude by discussing the implications of my findings for the study of American political development.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Interestingly, the relevance of actual crime remains a serious point of contention in the mass incarceration literature. Several influential studies vigorously dispute that a relationship exists between crime rates and the carceral state.Footnote 10 “The stark and sobering reality,” Michelle Alexander alleges, “is that, for reasons largely unrelated to actual crime trends, the American penal system has emerged as a system of social control unparalleled in world history. And while the size of the system alone might suggest that it would touch the lives of most Americans, the primary targets of its control can be defined largely by race.”Footnote 11 Indeed, a direct relationship does not exist between crime rates and mass incarceration. In his analysis of over-time crime data, Bruce Western finds: 1) “[T]here is good evidence that disadvantaged men are, at any given time, highly involved in crime and that is closely associated with the high rate of their imprisonment;” and 2) “[A]lthough high crime rates among the disadvantaged largely explain their incarceration at a given time, trends in crime and imprisonment are only weakly related over time.”Footnote 12

Given the explanatory limitations of crime rates, analysts frequently turn to politics for alternative causal theories. Western, for example, adopts the backlash model. “[T]he prison boom,” he maintains “was a political project that arose partly because of rising crime but also in response to an upheaval in American race relations in the 1960s and the collapse of urban labor markets for unskilled men in the 1970s.” He continues: “The social activism and disorder of the 1960s fueled the anxieties and resentments of working-class whites. These disaffected whites increasingly turned to the Republican Party through the 1970s and 1980s, drawn by a law-and-order message that drew veiled connections between civil rights activism and violent crime among blacks in inner cities.”Footnote 13 Western's statistical test of the relationship between social and political variables (e.g., change from a Democratic to a Republican governor) and imprisonment rates bolsters his hypothesis. He states: “The effects of partisanship were less ambiguous: there is a strong quantitative indication that Republican governors promoted the growth of the penal system.”Footnote 14

Some, however, doubt the theoretical clarity and explanatory power of backlash models. “Despite the great common sense appeal and parsimony of the backlash account,” Vesla M. Weaver avers, “it is more of a descriptive narrative and pseudo-theory for describing anti-black feeling expressed via election outcomes than a specified theory.”Footnote 15 She adds, “In other words, there are no accounts that fully theorize the backlash concept, when and under what conditions it occurs, and the distinctions between its various forms—policy, electoral, political, and general backlash.”Footnote 16 While top-down explanations for the conservative turn in American politics after the 1960s certainly feature these theoretical and conceptual flaws,Footnote 17 backlash arguments in many urban and suburban histories are not entirely without a theoretical basis.

Several urban and suburban histories have refined the descriptive history of postwar American politics and sketched an explanatory model that clarifies the timing and content of white backlash.Footnote 18 Though frequently underspecified, the causal claims at the center of these narratives are consistent with Herbert Blumer's group-position theory of racial prejudice. Blumer writes: “A basic understanding of race prejudice must be sought in the process by which racial groups form images of themselves and others. This process . . . is fundamentally a collective process. It operates chiefly through the public media in which individuals who are accepted as the spokesmen of a racial group characterize publicly another racial group.”Footnote 19 He hypothesizes that forms of prejudice can always exist, but the extent to which these attitudes are “intensified or weakened, brought to sharp focus or dulled” is historically contingent and political, frequently driven by the interests and actions of civic and political elites. Group definition, Blumer proposes, “occurs in the ‘public arena’ wherein the spokesmen appear as representatives and agents of the dominant group . . . [T]he definitions that are forged in the public arena center, obviously, about matters that are felt to be of major importance. Thus, we are led to recognize the crucial role of the ‘big event’ in developing a conception of the subordinate racial group.”Footnote 20 He adds: “[i]ntellectual and social elites, public figures of prominence, and leaders of powerful organizations are likely to be the key figures in the formation of the sense of group position and in the characterization of the subordinate group.”Footnote 21 Consistent with these propositions, several urban and suburban histories demonstrate that the timing and content of negative white reaction to liberal policies resulted from specific social and political events (e.g., black residential mobility and new housing policies), threats for which local white civic and political leaders drew upon preexisting racial notions to frame and mobilize against.

Yet applications of the backlash model within investigations of crime policy are inadequate, as they ignore the unique nature of urban change and crime during the late 1960s and early 1970s. In his history of the heroin epidemic in New York City, Eric C. Schneider notes:

The white populations in major cities began declining after 1950, the trend being most notable among middle-class families. Parents who moved to the nation's burgeoning suburbs did not have protecting their children from heroin in mind when they did so, but that was the effect. Suburbanization, at least initially, effectively separated white middle-class adolescents from the urban ills of crime and drug abuse. African American and Latino populations, located in neighborhoods where drug trading occurred, enjoyed no such immunity.Footnote 22

Crime statistics from the period bolster Schneider's observation. In 1970, the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence found that “[v]iolent crime in the cities stems disproportionately from the ghetto slum where most Negroes live” and that “[t]he victims of assaultive violence in the cities generally have the same characteristics as the offenders: victimization rates are generally highest for males, youths, poor persons, and blacks.”Footnote 23

Crime trends in New York City during the late 1960s and early 1970s are generally consistent with the commission's findings. In 1967, the New York Times reported that “almost 85 percent of the 543 murders solved in New York City last year were [murders committed] within racial groups, a figure that has remained virtually stable since the police department began compiling these statistics in 1964.”Footnote 24 In 1973, the year the state passed the punitive drug laws, the New York Times, based on their analysis of police records, found that a “black resident of New York City is eight times more likely to be murdered than a white resident of the city” and “in slightly more than four out of five New York homicides, the killer and his victim are of the same race.”Footnote 25 Accordingly, if crime generated a backlash, these data suggest that the backlash would have occurred within the black community rather than against it.

Nevertheless, other scholars propose that a white backlash did not develop from actual, local threats. Instead, national Republican political elites, these scholars claim, manufactured threats and inflamed white populations. Based on her analysis of national crime and attitudinal data, Katherine Beckett maintains: “political elites have played a leading role in calling attention to crime-related problems, in defining these problems as the consequence of insufficient punishment and control, and in generating popular support for punitive anticrime policies.”Footnote 26 Survey evidence from New York State, however, challenges this view. Consistent with top-down accounts and bottom-up backlash models, a 1970 survey of voters in New York mark a shift to the right. Almost two-thirds of respondents described themselves as conservative or moderate.Footnote 27 About 61 percent of respondents considered themselves members of the “silent majority.”Footnote 28 When asked to list the “main issues or problems” facing the nation, 44.3 percent mentioned ending the Vietnam War, 26.1 percent mentioned inflation or the high cost of living, 15.8 percent mentioned student protests, 13.8 percent mentioned drugs, 9.7 percent mentioned “law and order” or crime.Footnote 29 When asked to list the problems facing the state and local communities, 18.8 percent mentioned drugs, 17.5 percent mentioned crime, 11.2 percent mentioned pollution, and 11 percent mentioned taxes.Footnote 30

Another survey of voters commissioned by the New York Times in 1970 not only confirms these trends but also exhibits interesting cross-ethnic variation.Footnote 31 While only 13 percent of Roman Catholics identified as “liberal,” only 16 percent of Jews identified as “conservative.”Footnote 32 In fact, 77 percent of Jewish respondents reported being registered Democrats, 55 percent identified as liberal, and 76 percent gave Nixon a negative approval rating.Footnote 33 The issues of most concern to New York's ethnic groups in 1970 also reveal much about the specific social context of the period. Irish Americans rated student protests as the issue of most concern to them: 27 percent of Irish Americans mentioned this issue while only 19 percent of the entire sample mentioned it.Footnote 34 Thirty-three percent of nonwhites identified drugs and crime as major issues while only 18 percent of the entire sample mentioned either drugs or crime.Footnote 35 In addition, only 16 percent of nonwhites reported being “very happy” while 35 percent of the entire sample reported being very happy.Footnote 36 By 1970, student protests more so than drugs and crime in black neighborhoods defined Irish Catholic backlash to liberalism in New York. Nonwhites, by 1970, constituted the unhappiest population in the state, and drugs and crime fomented this anxiety. Although top-down and bottom-up models frequently lump multiple law-and-order concerns into the same category, these data indicate that New Yorkers were able to differentiate among various issues. Furthermore, variation in the salience they attached to various concerns depended upon the actual threats they experienced. Clearly, both top-down accounts and traditional backlash models are wanting.

Weaver formulates a compelling alternative. While backlash models draw attention to the emergence of popular pressures that can potentially shape crime policy development, the “frontlash” model emphasizes the discursive context that shapes the logic of policy design. First, this innovative theory refuses to minimize the significance of rising crime rates. In response to scholars that dismiss the causal significance of crime rates, Weaver counters: “While it is true that criminal justice legislation has not responded mechanically with fluctuations in crime rates, in their eagerness to dismiss crime, they have thrown the baby out with the bathwater.” She advises that “a more fruitful discussion is to understand why crime came to be politicized in the 1960s and not before” and “unearth the full quilt of motivations” driving the elevation of crime “to the status of a major national problem.”Footnote 37

Second, Weaver formulates a theory, “frontlash,” that emphasizes the causal importance of strategic political entrepreneurs. She defines frontlash as “the process by which losers in a conflict become the architects of a new program, manipulating the issue space and altering the dimension of the conflict in an effort to regain their command of the agenda.”Footnote 38 Drawing upon the logic of frontlash, Weaver hypothesizes that rising crime rates and riots created an opportunity for the losers in the civil rights struggles of the early 1960s to “sharpen the connection of civil rights to crime”Footnote 39 and, in turn, tilt the discursive space in a more conservative direction. “Strategic policymakers,” she contends, “conflated these events, defining racial disorders as criminal, which necessitated crime control and depoliticized the grievance.”Footnote 40 She adds, “Strategic entrepreneurs thus used the crime issue as a vehicle to advance a racial agenda without violating norms, attaching the outcomes of old conflict (Great Society programs and civil rights legislation) to the causes of the new problem—the breakdown of law and order.”Footnote 41

The effect of this conflation on crime policy and American political development, according to Weaver, was profound. She explains: “Along with the articulation of a new issue problematic, entrepreneurs seek issue dominance by creating a monopoly on the understanding of an issue, associating it with images and symbols while discrediting competing understandings.”Footnote 42 Thus, the strategic conflation of civil rights and crime by the losers of previous battles over racial equality shifted the discursive terrain on which political battles in the post–civil rights era were fought in favor of punitive crime policies in particular and conservative policies in general. And faced with a dramatically different discursive context, liberals relented: “The liberal social uplift approach atrophied under the weight of this powerful doctrine. Sandwiched between two traps—being soft on crime and excusing riot-related violence—liberals had to forgo their ideal outcomes and moved closer to the conservative position.”Footnote 43

Frontlash offers a compelling macro account for the conservative turn in American political development. In this way, the theory offers a potentially stronger theoretical and historical explanation for Nelson Rockefeller's ideological transformation from the late 1950s to the passage of drug laws in 1973 than the traditional backlash model. Rockefeller entered the governor's mansion a racial liberal in 1958. In fact, in order to gain Rockefeller's endorsement in his pursuit of the presidency in 1960, Nixon forged the “compact of Fifth Avenue,” agreeing to push for a serious civil rights plank at the Republican National Convention. And he did. The final civil rights plank featured: “an extensive array of civil rights' commitments, including support for equal voting rights, establishment of a Commission on Equal Job Opportunity, and a prohibition against discrimination in federal housing and in the operation of federal facilities.”Footnote 44 In 1974, Rockefeller left Albany a law-and-order conservative—a central and notorious figure in the historiography of mass incarceration. Yet crime and attitudinal data from New York suggests that the traditional backlash model cannot sufficiently explain Rockefeller's ideological transformation. The drug laws did not reflect the top concerns of whites in New York. Additionally, their punitiveness was disproportionate to the crime threat whites actually faced and the salience they attached to crime and crime-related problems.

Unfortunately, frontlash also falters, as it fails to provide a precise explanation for the specific timing of the drug laws. Weaver writes, “By 1968, the Democratic Party was clearly beginning to recognize the costs of being seen as supporting lawbreakers and their commitment to focusing on the root causes of crime had faded.”Footnote 45 Liberals in previous civil rights battles may have recognized by 1968 the emergence and dominance of a new policy image and causal story for crime, but this does not resolve why Rockefeller—a Republican and liberal in previous civil rights battles—waited until 1973 to pass the draconian drug laws. Consequently, another explanation is needed: one that accounts for the politicization of crime and the timing of specific criminal justice policies. Drawing upon key aspects of backlash and frontlash, the alternative approach formulated here emphasizes three dynamics: macrostructural shifts, the indigenous construction of crime and crime-related problems within African American communities, and the evolving incentives and opportunities of white political elites.

While mid-century political and socioeconomic transformations instigated new forms of conflict between African Americans and whites in certain policy arenas, these shifts also provoked new forms of conflict within the African American community. The civil rights movement and structural economic shifts (e.g., deindustrialization, technological changes, and the suburbanization of work) sparked the movement of middle-class black families out of inner cities and concentrated populations of the chronically jobless.Footnote 46 As the proportion of jobless adults in a neighborhood increased, the social organization of communities—those institutions (e.g., churches, businesses, and recreational organizations) that could curb the negative social effects of periodic economic downturns—weakened. “As these organizations decline,” William Julius Wilson theorizes, “the means of formal and informal social control in the neighborhood become weaker. Levels of crime and street violence increase as a result, leading to further deterioration of the neighborhood.”Footnote 47

Chronic joblessness of the urban black poor and concomitant “ghetto-related behavior” conflicted with the material interests (i.e., property values) and life chances (i.e., personal safety and children's futures) of middle-class black families. Still, if the black middle-class exited inner cities like their white counterparts, then this spatial separation would have frustrated the emergence of intra-group conflict. Yet Wilson and others also indicate that 1) small groups of working and middle-class African Americans remained in the inner city; and 2) those that moved were not fully detached from the lives of the urban black underclass.Footnote 48 These shifts, I argue, sharpened class boundaries and fostered intragroup resentment and antagonism within the African American community.

Given the unique historical construction of class within the black community, I must note that class distinctions within the African American community do not follow neat socioeconomic classifications but carry particular moral content and behavioral implications.Footnote 49 In 1965, St. Clair Drake noted, “Although, in Marxian terms, nearly all [blacks in the ghetto] are ‘proletarians,’ with nothing to sell but their labor, variations in ‘life style’ differentiate them into social classes based more upon differences in education and basic values (crystallized, in part, around occupational differences) than in meaningful differences in income.”Footnote 50 Delineating the boundaries of these class distinctions, Drake assayed:

Some families live a “middle-class style of life,” placing heavy emphasis upon decorous public behavior and general respectability, insisting that their children “get an education” and “make something out of themselves.” They prize family stability, and an unwed mother is something much more serious than “just a girl who had an accident” . . . Within the same income range, and not always at the lower margin of it, other families live a “lower-class life-style” being part of the “organized” lower class, while at the lowest income levels an “unorganized” lower class exists whose members tend always to become disorganized—functioning in an anomie situation where gambling, excessive drinking, the use of narcotics, and sexual promiscuity are prevalent forms of behavior, and violent interpersonal relations reflect an ethos of suspicion and resentment which suffuses this deviant subculture. It is within this milieu that criminal and semi-criminal activities burgeon.Footnote 51

While economic position certainly matters in the construction of African American class identities, it interacts with definitions of virtue to form a historically variable matrix of shared class understandings. And, within this cultural framework, criminal activity is understood in behavioral and moral terms.

Still, there is a plausible alternative interpretation of this class content. “Respectability,” Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, writes, “demanded that every individual in the black community assume responsibility for behavioral self-regulation and self-improvement along moral, educational, and economic lines. The goal was to distance oneself as far as possible from images perpetuated by racist stereotypes.” She continues: “There could be no transgression of society's norms. From the public spaces of trains and streets to the private spaces of their individual homes, the behavior of blacks was perceived as ever visible to the white gaze.”Footnote 52 Accordingly, class-based interpretations of crime and crime-related problems could have been part of a broader race-based political project: a form of social control meant to liberate the race rather than punish the poor.Footnote 53

Although it is plausible that working and middle-class African American responses to drugs and crime were rooted in a fear of the white gaze rather than the black criminal, it is also quite possible that civil rights victories and urban socioeconomic shifts in the late 1960s lessened the fear of the white gaze and increased the threat of the urban black poor. Applying the logic of Blumer's theory of race prejudice to class prejudice within the African American community, I hypothesize that intragroup class distinctions were “brought into sharp focus” by rising crime rates. Middle-class African Americans, I propose, considered drug addicts and dealers as threats to “respectable” or “decent families,” “good citizens,” and “hardworking people.” Influential black “intellectual and social elites, public figures of prominence, and leaders of powerful organizations,” drawing upon indigenous frames, articulated a causal story that attributed crime and crime-related problems to individual behavior rather than social structure, and, in doing so, reconfigured the discursive context of crime policymaking in the post–civil rights era.

While discourse can shape the content of policy, broader electoral imperatives can influence the timing of policy enactment. Policy change, John W. Kingdon argues, “usually comes about in response to developments in the problem and political streams . . . [Problem and political windows] call for different borrowings from the policy stream.” He elaborates: “If decision makers become convinced a problem is pressing, they reach into the policy stream for an alternative path that can reasonably be seen as a solution. If politicians adopt a given theme for their administration or start casting about for proposals that will serve their reelection or other purposes, they reach into the policy stream for proposals.”Footnote 54 Policy solutions and the “causal stories” on which they depend do not always experience a clear, straightforward selection process: all solutions are not created equally. Rather than floating in a “policy primeval soup”Footnote 55 until selected by a policy entrepreneur, some policy solutions, as Weaver suggests, reach the top of the agenda because they are consistent with the dominant causal story attached to a problem.Footnote 56 Politicians then select from a limited set of solutions a policy “that will serve their reelection or other purposes.”

In order to adjudicate between contending theories of crime policy formation, I trace the development of the Rockefeller drug laws. This case serves both substantive and analytic purposes. In terms of the former, mass imprisonment of racial minorities is fundamentally connected to sentencing policies associated with the “War on Drugs.”Footnote 57 The drug laws are particularly significant in this regard because they “were the first of their kind at that time, and since then, we have had virtually mandatory sentencing of a similar nature in every state in the country.”Footnote 58 The passage of the drug laws, therefore, represents a critical juncture in the expansion of the American carceral state, as the laws—both their design and the causal story—served as a conceptual precedent for subsequent criminal justice policies in states across the country.

New York State also offers additional analytic leverage. First, crime rates climbed dramatically in New York City from the late 1950s until the early 1970s. Second, one person served as governor during that entire period. The first condition allows me to explore “why crime came to be politicized.” The second condition overcomes some of the weaknesses of large-N statistical analyses of crime policy development. These studies persuasively demonstrate a strong relationship between the conservative turn in American politics (i.e., the election of Republican governors) and various measures of mass imprisonment, but they fail to isolate a particular causal process. Furthermore, since contending theories predict similar outcomes (i.e., punitive crime policy), successful adjudication among them requires examining their observable implications within the causal processes generating predicted outcomesFootnote 59 and adopting a historical approach that is analytically sensitive to the potential for complex conjunctures of relevant causal variables, including macrostructural transformations, the local politicization of crime, the evolving goals of elected officials, and the timing of policy enactment.Footnote 60

But I do not begin in Albany. This history starts in Harlem, a community hit hardest by rising crime rates and drug addiction. Drawing upon newspaper articles, archival materials, polling data, and testimony before legislative committees, this study traces how African American activists framed and negotiated the incipient drug problem in their neighborhoods and interrogates the policy prescriptions they attached to indigenously constructed frames. It will describe how African Americans facing the material threats of crime and crime-related problems drew upon the moral content of indigenous class categories to understand these threats and develop policy prescriptions. Moreover, these policy prescriptions did not attempt to “uplift the race:”Footnote 61 they sought to remove the poor. It will show that working and middle-class African Americans and their civic and political institutions and leaders defined the local discursive context from which the drug laws emerged—a discursive context that limited the political potential of structural approaches to crime, crime-related problems, and urban poverty and created a political opportunity for the ever-ambitious Rockefeller.

THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF DRUG CONTROL POLICY IN NEW YORK STATE

Metcalf-Volker (1962)

In 1961, a local television station aired an hour-long documentary entitled, “Junkyard by the Sea,” which publicized the city's growing heroin problem.Footnote 62 In its review, the New York Times praised the film's compassionate portrayal of addicts and its attention to structural causes. The paper observed: “Like some other television studies of narcotics and their users, this program included interviews with the unfortunate victims of the habit. But here sensationalism was not the purpose. The discussions were conducted intelligently and served to establish compellingly the realization that present facilities for meeting the problem are woefully inadequate.”Footnote 63 “The cameras,” the New York Times recounted, “ranged from prison to hospital to a Harlem street where, in the midst of poverty and despair, drug addiction is flourishing.”Footnote 64 While bringing attention to a growing and tragic social problem, the documentary and the review in the New York Times exposed the dominant causal story attached to drug addiction among many white elites at the time—one that considered the addict a victim of broader social forces—and the dominant policy model derived from that causal story—one that emphasized medical treatment and rehabilitation rather than punishment.

The documentary also featured a white minister, Rev. Norman C. Eddy of the East Harlem Protestant Parish (EHPP). Describing his depiction in the film, the New York Times observed: “His enlightened approach to the situation he has encountered was effectively conveyed to the viewer.”Footnote 65 What was his “enlightened approach”? He prescribed counseling, social services, and medical treatment. To respond to the growing heroin epidemic in East Harlem, Rev. Eddy and the EHPP “organized education programs aimed at informing the young about the dangers of narcotics, and formed a Narcotics Committee in 1956 to host discussions for families of addicts. Subsequently, the parish opened a storefront drop-in center and a clinic where addicts received a physician's services, referrals to hospitals, assistance in job searches, psychological counseling, and legal assistance for those facing criminal charges.”Footnote 66

Overwhelmed by the magnitude of the need, the organization lobbied local and state officials for more resources toward the end of the 1950s. Rev. Eddy and the EHPP pressured city and state government to expand the capacity behind the rehabilitative model, specifically imploring them to provide more hospital beds for heroin addicts.Footnote 67 In 1962, Rev. Eddy, driven by these concerns, “succeeded in creating a statewide coalition that agreed that heroin users required treatment, not punishment.”Footnote 68 And his efforts accomplished much. In his annual address to the legislature in 1962, Rockefeller highlighted the state's drug problem: “Narcotics addiction is a problem of most urgent human concern. Its insidious effects are tragic to the addict and his family and dangerous to society.”Footnote 69 Furnishing the dominant causal story attached to this social problem, the governor asserted: “Many arrested addicts whose crimes are related to their addiction and who are not considered incorrigible may appropriately benefit from medical and psychiatric treatment in special facilities in civil hospitals followed by aftercare in the community.”Footnote 70 By April, the legislature passed and the governor signed the Metcalf-Volker Narcotic Addict Commitment Act of 1962 into law. The law allowed addicts convicted of nonserious crimes to select in-patient treatment and aftercare rather than go to prison. The law also established a narcotics office within the Mental Hygiene Department and created a state Council of Addiction, a policy advisory board.Footnote 71

This was a unique political moment and policy outcome. Despite the concentration of the drug problem in black neighborhoods during the 1950s, white civic leaders and politicians, and white interest groups, like the Bar Association and the New York State Council of Churches, dominated this policy arena. Rev. Norman Eddy, the interest groups, and politicians emphasized structural conditions and defended the rehabilitative model, which defined the logic of Metcalf-Volker. Although he came to support the legislation, the city's drug crisis was not at the top of Rockefeller's agenda. At this point, African American civic and political leaders in Harlem were not central players in this policy arena. Though concerned, their attention was still focused primarily on civil rights.Footnote 72 All of this would soon change, of course. Soon black leaders from Harlem would assume a prominent role in this policy debate. Soon Rockefeller would put drugs at the top of his agenda. Soon the dominant causal story would change.

Narcotics Addiction Control Commission (1966)

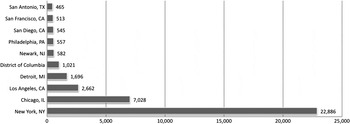

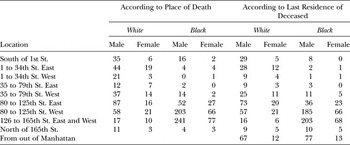

By the early 1960s, drug addiction had become a huge problem in African American communities. As Figure 1 reveals, African Americans constituted over half of all registered drug addicts in the United States. Figure 2 exposes two additional important patterns: the concentration of drug addicts within urban centers with large black populations and the staggering nature of New York City's drug problem. Half of all registered narcotic addicts in the United States lived in New York State, and most of them were located in New York City.Footnote 73 Moreover, the city's drug problem was not distributed evenly across boroughs and neighborhoods. Table 1 further clarifies the dimensions of this brewing crisis: Not only were a high number of drug-related deaths reported in upper Manhattan, but most of the victims were black.

Fig. 1. Active Narcotic Addicts Reported in the United States as of December 31, 1963. Source: “Organized Crime and Illicit Traffic in Narcotics,” Hearings before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations, United States Senate (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1964), 761. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics based these statistics on data reported to them by local agencies.

Fig. 2. Active Narcotics Addicts Reported in the United States as of December 31, 1963. Source: “Organized Crime and Illicit Traffic in Narcotics,” Hearings before the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations, United States Senate (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1964), 764. As of December 31, 1963, there were 48,535 active narcotic addicts registered by the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, in the United States. The ten cities listed above account for 78.2 percent of the total 48,535.

Table 1. Area Distribution of Drug-related Deaths by Race and Gender (1950–1961)

Source: Milton Helpern and Yong-Myun Rho, “Deaths from Narcotism in New York City: Incidence, Circumstances, and Postmortem Findings,” New York State Journal of Medicine 66, no. 18 (1966), 198. These data are reported by New York City's Office of the Chief Medical Examiner for Investigation. The diagnosis of drug-related death (acute narcotism or direct complications of narcotic addiction) is “based on a investigation of the circumstances of death, the gross and and microscopic pathologic findings of a complete autopsy, and toxicologic study” (196).

Kenneth B. Clark's Dark Ghetto vividly depicted the social and economic origins of these trends as well as their dire consequences.Footnote 74 Economic transformations hit Harlem hard, dramatically increasing the proportion of jobless adults: “About one out of every seven or eight adults in Harlem is unemployed. In the city as a whole the rate of unemployment is half that . . . [I]n 1960 twice as many young Negro men in the labor force, as compared to their white counterparts, were without jobs.”Footnote 75 The job prospects for young women were equally grim: “For the girls, the gap was even greater—nearly two and one-half times the unemployment rate for white girls in the labor force.”Footnote 76 Segregation and the disappearance of work, especially among the young, generated ghetto-related behaviors that ravaged the nation's black capital.

Among these ills, drug addiction was perhaps the worst. Clark powerfully detailed this painful reality:

Harlem is the home of many addicts; but as the main center for the distribution of heroin, it attracts many transients, who, when the “panic is on” cannot buy drugs at home. The social as well as the personal price of the drug industry is immense, for though addicts are victims of the system, so, too, are nonaddicts: Many addicts resort to crime in their desperate need for money to feed the expensive habit.Footnote 77

Unable to buy insurance to protect their property or move into white neighborhoods, nonaddicts, as victims of drug-related crimes, shared with addicts “the fact that they are all powerless to protect themselves from a complex and interrelated pattern of exploitation.”Footnote 78 One Harlemite, Mrs. Miller of 125th Street, gave voice to the anxieties of nonaddicts: “It's time someone brought out the facts about Harlem. The middle class Negro is a minority, the rampant poverty-ridden element are in the majority.”Footnote 79 Her comments also presage the social conflicts that would drive drug policymaking for the next decade.

Though not central players in the passage of Metcalf-Volker in 1962, Harlem's leaders and working and middle-class residents began to bring out the “facts about Harlem” and press government officials for action in the early 1960s. The October before the 1961 mayoral election, Robert F. Wagner, Jr., the incumbent, visited the Amsterdam News. The paper's headline emphasized race, but the meeting focused on crime and drugs. The daily had recently reported that one of the mayor's commissioners was a member of a club that discriminated against African Americans. Wagner informed the board that the commissioner would “have to make a choice:… [The commissioner] is either going to have to resign from that club or resign as Commissioner of Commerce.”Footnote 80 The two-hour meeting, however, covered much more, “ranging from the Wagner record on housing and schools to plans for increased efforts to clean up vice and crime in Harlem.” The publishers “pointedly called the Mayor's attention to the number of drug addicts and prostitutes found in certain Harlem areas.”Footnote 81

As Rev. Eddy and others embraced a structural analysis of growing drug addiction and aggressively lobbied state leaders for rehabilitation-oriented policies, an alternative causal story and policy approach started to take shape in Harlem. Mark T. Southall, a key figure in the city's black political establishment,Footnote 82 lobbied city and state leaders to focus on Harlem's narcotics problem. At a public hearing organized by the state Democratic Party to hear proposals for the party's platform in 1961, Southall, then Democratic leader of Harlem, told a most foreboding tale: “[Harlem] is slowly and surely becoming a cesspool of the dreadful narcotics racket and disease . . . Irreparable harm is being done to the community . . . Churches are constantly being robbed by addicts and property is being destroyed . . . Ministers and other citizens of the community are being mugged, beaten and robbed by addicts, who also are guilty of rapes, pickpocketing and many other crimes, daily and nightly.”Footnote 83 Given this stark assessment, Southall requested “mandatory prison sentences for convicted dope pushers, creation of a narcotics hospital in Harlem, and compulsory commitment and treatment of addicts.”Footnote 84 Southall also initiated a petition drive to pressure Rockefeller to adopt more aggressive antidrug measures.

As time passed, Harlem's drug and crime problems intensified. Because Metcalf-Volker did not appear to arrest the city's growing narcotics problem, African American leaders continued to press local and state officials for action. Their pleas grew desperate, their prescriptions harsh. James Booker regularly used his column in the Amsterdam News to decry Harlem's dope problem and shame white political leaders into action. Months after the passage of Metcalf-Volker, Booker remarked, “Narcotics conditions getting worse with summer coming. You can help by writing the Mayor and the President, demanding a local narcotics hospital now and less conferences and press releases.”Footnote 85 A few weeks later, an item in his column read: “Leading officials inform us they are about to crack down on one of Harlem's biggest dope and numbers rings . . . Which reminds us that still not enough is being done to curb the narcotics menace uptown.”Footnote 86 After the 1962 election, Booker wondered: “What happened to all that campaign talk about people doing something about the growing narcotics problem. It's getting worse, and after-care and rehabilitation are badly needed. What about it Mr. Attorney General, Mr. Governor, and Mr. Mayor?”Footnote 87

Other African American civic and political leaders employed more aggressive tactics. They held rallies and marches.Footnote 88 They circulated petitions to educate white political leaders and offer their own solutions. In the fall of 1962, Rev. O. D. Dempsey led a seven-week, “anti-dope drive.” Toward the end of the drive, thirty civic leaders signed a four-point plan: “1. Urge President Kennedy to push Congress to provide funds for the construction of a hospital in the New York area to treat, cure, and rehabilitate addicts. 2. Also urge the president to mobilize all law-enforcement agencies to unleash their collective fangs on dope pushers and smugglers. 3. Urge Gov. Rockefeller to also push a similar crackdown. 4. Spur Mayor Wagner and Police Commissioner Michael Murphy to turn loose the city's police, including the transit and housing lawmen, on criminals and narcotics dealers.”Footnote 89

In late 1965, the Amsterdam News broached several issues with then mayor-elect John Lindsay. They chatted about housing and education. They discussed drugs and crimes. Specifically, Lindsay and the board explored “putting suspected narcotics pushers under a 24-hour surveillance and opening drug-store type clinics to launch a neighborhood street-level attack on addiction.”Footnote 90 After John Lindsay won the mayoralty in 1965, Rev. Dempsey continued to press his “anti-dope” agenda. He circulated petitions urging the newly elected mayor to take the following steps: “1. Declare all habitual narcotics users to be sick people in need of medical assistance. 2. Empower the city and state to construct a huge facility to house and treat them. 3. Set up rehabilitative centers to train cured addicts in employable skills and help re-integrate them into society. 4. Call for a voters' referendum in 1966 to possibly enable the city to do the last two of the above.”Footnote 91 Dempsey's 1966 petition differs from the 1962 version in one very significant way: while the 1962 petition evinced some compassion for addicts and urged political leaders to marshal all of the powers of the state against “dope pushers and smugglers,” this petition beseeches political leaders to marshal the powers of the state against the addict. The petition certainly champions rehabilitation and job training, but Dempsey made the provision of these services contingent upon the state labeling addicts “sick” and removing them from the community.

Rockefeller frequently consulted African American leaders on drug policy starting in the mid-1960s. In 1965, several black leaders, as the governor developed his legislative agenda, sent him their policy requests. A. Philip Randolph requested a raise in the minimum wage and a local civil rights leader in the Bronx asked for more education funding to decrease class size.Footnote 92 Mark T. Southall, then state assemblyman from Harlem, sent the governor a telegram asking him to introduce “bills to strengthen the state's narcotics program and to takeover Ellis Island to house narcotics addicts to aid in their rehabilitation.”Footnote 93 In late 1965, the governor held meetings with “Harlem officials and a follow-up closed session with an influential group of Negro leaders” to discuss the community's drug and crime problem.Footnote 94 At a public meeting with the governor at Harlem's Salem Methodist Church, members of the community decided to tell “him like it is.” The audience included Rev. David Licorish of the Abyssinian Baptist Church and Dr. M. Moran Weston of St. Philip's Episcopal Church. Rockefeller asked Weston, “Would you feel people would accept the isolation of addicts together with training to prepare them to come back?” Moran refused to speak for others, but he “personally felt hospitalization to withdraw addicts from drugs and training them in skills once they've been treated would be helpful.”Footnote 95

While the comments speak for themselves, the congregations represented at this meeting bespeak brewing class tensions in Harlem. These were no ordinary churches. “Throughout the nineteenth century,” Gilbert Osofsky noted in 1966, “St. Philip's was reputed to be the most exclusive Negro church in New York City.” He elaborated: “Its members were considered ‘the better element of colored people.’. . . This reputation as a fashionable institution made membership in St. Philip's a sign of social recognition . . . St. Philip's was also recognized as the ‘wealthiest Negro church in the country,’ and this reputation has continued to the present.”Footnote 96 Not only was the “Mighty Abyssinian” one of the largest protestant congregations in the nation by the 1940s and served as the religious home for many prominent African Americans, but it also operated as an organizational center for civil rights activism in New York.Footnote 97 Even though Salem Methodist, like the other two, served as “one of the most significant social institutions in Harlem,” its culture of worship did not cater “to the tastes of the black bourgeoisie.”Footnote 98 Instead, it welcomed migrants from the south as well as other elements of Harlem's working class.Footnote 99 This meeting, then, symbolizes the formation among Harlem's working class and “better element” of a common “perception of threat” posed by “junkies” and “pushers.” The meeting also signals the deployment of the resources of the “most significant institutions in Harlem” against that threat.

In 1966, Rockefeller used his annual message to the legislature to sketch a more aggressive approach to the city's drug problem. “We must,” he exhorted “remove narcotics pushers from the streets, the parks and the school yards of our cities and suburbs.” He then announced: “I shall propose stiffer, mandatory prison sentences for these men without conscience who wreck the lives of innocent youngsters for profit. Society has no worst enemy.” The governor also remarked, “Narcotics addicts are said to be responsible for one-half the crimes committed in New York City alone—and their evil contagion is spreading into the suburbs.” Rockefeller then disclosed that he would recommend “legislation to act decisively in removing pushers from the streets and placing addicts in new and expanded state facilities for effective treatment, rehabilitation, and after care.”Footnote 100

In April 1966, the legislature passed the governor's proposal. The new law created the Narcotics Addiction Control Commission in the Department of Mental Hygiene. The legislation gave the new committee the power “to conduct the narcotics addict rehabilitation program, and provides for addicts to be certified to the rehabilitation program (i) civilly, (ii) after conviction of certain crimes, and (iii) after arrest but before trial.”Footnote 101 The legislation appropriated $75 million for the construction of rehabilitation centers. The law also increased the “sentences for ‘pushers’ of narcotics. For example, under this bill a person convicted of selling to a minor would be subject to a minimum sentence of 10 years.”Footnote 102 Even though the governor considered this “a balanced approach” and suggested it “would help addicts return to normal, useful and healthy lives,” liberals thought otherwise. Liberal Democratic Manhattan Assemblyman Albert Blumenthal warned: “We're deluding the public if we say we're going to cure addicts by locking them up for three years. Perhaps we should tell the public that we're faced with a threat as great as the bubonic plague, and until we find a cure we're going to set up a concentration camp in every community.” Percy Sutton, an African American assemblyman from Harlem, shared this sentiment: “The Governor calls this human renewal . . . I call it human removal.”Footnote 103

Over a month later, Mayor John Lindsay and several other state and local officials joined Rockefeller's effort. The joint effort attempted to raise $75 million from state and federal sources to implement major components of Rockefeller's plan.Footnote 104 At the press conference, Rockefeller directly addressed the African American community. After noting that half of the nation's addicts reside in New York City, specifically in Harlem and other minority sections, the governor stressed his desire to “rescue thousands of citizens from lives of degradation and crime.”Footnote 105 The city's African American political establishment welcomed this approach.Footnote 106 The Amsterdam News hailed the plan: “We congratulate Governor Rockefeller on the high priority he is giving to the fight on narcotics . . . We agree wholeheartedly with the Governor. There is nothing so crippling in certain areas of New York as the misery connected with drug addiction.” The editorial ended: “We believe New Yorkers from the split level homes to the cold water tenements will join with the governor in his fight against narcotics addiction. We pledge our support! This involves us all!”Footnote 107 The editorial board especially liked compulsory treatment for addicts. The paper proclaimed, “We are for any move that will take addicts off of the streets and subject them to treatment and aftercare supervision.”Footnote 108

Sutton's description of the new policy as human removal was correct—just what many Harlem leaders desired. Beginning in the early 1960s, African American civic and political leaders began articulating an alternative causal story for the city's drug epidemic that increasingly placed blame for the crisis on individual moral failings and increasingly rejected the rehabilitative model advocated by Rev. Eddy and others. By 1966, sympathy for the addict had dissipated. While their drug addiction may have hastened their social death, their threat to what to Mrs. Miller of 125th Street called “the middle-class Negro” caused many African American civic and political leaders to advocate for their civil death—if only temporarily. Despite Blumenthal's inflammatory rhetoric, members of Harlem's political establishment advocated to the mayor, governor, and the president of the United States that addicts should be forcibly removed from the community and placed in isolated camps. Some tempered their proposals with suggestions of treatment, rehabilitation, and job training, but these proposals also made the loss of civil rights a prerequisite for these services.

Despite disagreement over the appropriate policy approach to addicts, a consensus had emerged on the appropriate treatment of “pushers.” Back in 1961, Mark Southall advocated mandatory sentences for “dope pushers.” By the mid-1960s, leaders, like Rev. Dempsey, wanted law enforcement at all levels of government to “unleash their collective fangs on dope pushers and smugglers.” Consequently, in the arguments they crafted to defend their policy prescriptions, a core segment of Harlem's civic and political establishment laid the discursive terrain from which the carceral state would grow. Many of New York's African American leaders, who believed addicts and dealers jeopardized the health of the community and the lives of “decent” and “industrious” people, developed a particular causal story for the drug problem—a simple one consistent with temporary mass incarceration. By the late 1960s, many African American leaders, both those focused on rehabilitation and those decided on punishment, countenanced, if not lobbied aggressively for, an emboldened police state, and most were, explicitly and implicitly, building arguments for an expanded penal system.

The Drug Laws (1973)

By the late 1960s, Harlem's drug and crime problems had become dramatically worse, which generated a black middle-class backlash to liberal approaches to addiction and crime. Rockefeller “was repeatedly confronted with the drug problem by angry residents at his ‘town meetings’ in black communities.”Footnote 109 The residents of Lenox Terrace, a black middle-class bastion, used their voice to do a “little cleaning up.” In December 1967, residents held a meeting to mobilize against crime in Harlem. They were “concerned about a crime problem that has emptied the neighborhood's tenement-lined side streets at night, forced merchants to close their shops early and brought armed civilian patrols into the streets.”Footnote 110 Residents of Harlem's luxury developments, like everyone else, blamed “addicts for the purse snatchings, the muggings, the burglaries and the beatings.”Footnote 111 Consequently, the group agreed to petition for more police and seek meetings with Mayor Lindsay, the Police Commissioner Howard R. Leary, and Manhattan Borough President Percy Sutton.Footnote 112 They were not alone. While the residents met, another group, Petitions for Protection, were circulating their petitions for a greater police presence in the area.

African American ministers also continued to lobby government for more police to protect their churches and congregants from what Rockefeller called the “invading army” of addicts. Ministers protested “that drugs were being openly sold on the streets of Harlem without police interference and demanded action.”Footnote 113 Additionally, ministers complained that drugs and crime were ruining religious life in the community. And they were. Churches were victims of crime:

Burglars broke into Salem Methodist Church . . . and stole 15 typewriters used in a job training program sponsored by the church and Eastern Airlines. They came back two weeks ago and stole a tape recorder and a record player . . . A block away, burglars stripped the Williams Institutional Christian Methodist Episcopal Church . . . of its public-address system and microphone . . . [A]lthough the church had hired a night watchman, they broke in again and made off with the chancel carpet.Footnote 114

Drugs and crime also affected church attendance. Many churches reduced the number of nighttime services and activities because “many residents refuse to leave their homes at night.”Footnote 115 Rev. E. G. Clark, pastor of Harlem's Second Friendship Baptist Church, estimated that “90 percent of the people refuse to come out at night . . . even on Sunday” because of fear.Footnote 116

Local businesses told similar stories. Andrew Gainer, whose Harlem hardware store had been burglarized fourteen times in two years, vented, “To hell with civil liberties! . . . People are being destroyed by dope and crime every day. Yes, let's bring back the Tactical Police Force. I'd even bring in mounted police.”Footnote 117 Gainer also disclosed that a group of local business leaders called “Harlem Citizens for Safer Streets” would lobby Gov. Rockefeller for a program of free narcotics for addicts, a three-year rehabilitation program, and job training.Footnote 118 Mrs. Cleo Weber, owner of a local beauty parlor, indicated that her “shop had been burglarized twice in less than three months.”Footnote 119 Vocalizing her own consternation with Harlem's drug and crime problem, Weber griped: “You have a little business and you struggle so hard, and you can't even carry your money home at night . . . And you can't say anything to these people. You're afraid to. They're dangerous.”Footnote 120 Lou Borders, whose clothing store had been burglarized twelve times in twenty years, remarked, “That soul brother stuff—you can forget it.”Footnote 121 Borders, owner of one the oldest black stores in Harlem, asked, “How much can a man take?”Footnote 122 Soon the governor would respond to these fears and frustrations and respond in dramatic fashion.

In January of 1973, the governor sent the legislature a series of “stern measures”Footnote 123 aimed at finally curbing the state's drug crisis. The central components of the new approach included life prison sentences for “all pushers” convicted of selling heroin, amphetamines, LSD, hashish, and other dangerous drugs; life prison sentences for addicts that commit violent crimes while under the influence of illegal narcotics; and, the removal of protections for youthful pushers so teenagers caught selling illegal narcotics would receive the same penalty as adult offenders.Footnote 124 The address, which the New York Times editorial board called “the lock-‘em-up-and-throw-away-the-key speech,”Footnote 125 enraged liberals. Blumenthal described the plan as a “cheap shot”—a very simplistic approach to a “very complicated problem.”Footnote 126 The New York Civil Liberties Union characterized the proposal as “a frightening leap towards the imposition of a total police state.”Footnote 127

The legislature eventually altered the bill after various law enforcement agencies protested the potential challenges of implementation. The final measure included mandatory minimum sentences, limited plea-bargaining power, a system of mandatory life sentences that would allow for parole and lifetime supervision, and removed hashish from the list of dangerous drugs. Liberals remained unhappy. Senate Democrats responded with a bit of hyperbole: “We are handmaidens of tyranny and the arrogance of the executive branch.”Footnote 128 Not sparing invectives, the New York Civil Liberties Union called it “one of the most ignorant, irresponsible, and inhuman acts in the history of the state.”Footnote 129 Despite the objections of liberals and law enforcement groups, the measure passed the Assembly by a vote of 80 to 65 and the Senate by 46 to 7.Footnote 130

The 1973 drug laws represented a dramatic shift for Rockefeller. His speech at the 1964 Republican National Convention was a clarion call against conservative extremism: “These extremists feed on fear, hate and terror. They have no program for America—no program for the Republican Party. They have no solution for our problems of chronic unemployment, of education, of agriculture, or racial injustice or strife.” Rockefeller pressed: “There is no place in this Republican party for such hawkers of hate, such purveyors of prejudice, such fabricators of fear, whether Communist, Ku Klux Klan or Bircher. There is no place in this Republican party for those who would infiltrate its ranks, distort its aims, and convert it into a cloak of apparent respectability for a dangerous extremism.”Footnote 131 By 1973, liberal New Yorkers began to view their governor as the very embodiment of the extreme conservatism he derided in 1964. Liberals condemned him for the Attica massacre, a prison riot that ended with the death of twenty-nine inmates and ten hostages. For his part, Rockefeller gladly embraced extreme measures to end what he considered the “reign of fear” created by drug trafficking and addiction.Footnote 132

As “frontlash” and the argument advanced here suggest, the punitive drug laws passed after a systematic discursive shift in crime-policy making. The causal story that undergirded Metcalf-Volker—the notion that addiction was a sickness that was rooted in structural conditions and that required a medical approach—collapsed under the weight of a new causal story, one that considered the addict a criminal—victims of their own moral failings. Writing about the atmosphere within the Rockefeller administration, Joseph E. Persico, an aide to the governor, confessed, “I never fully understood the psychological milieu in which the chain of errors in Vietnam was forged until I became involved in the Rockefeller drug proposal. . . . This experience,” he reflected, “brought to life with stunning palpability psychologist Irving Janis's description of groupthink: ‘the concurrence-seeking tendency which fosters overoptimism, lack of vigilance and sloganistic thinking about the weakness and immorality of outgroups.’”Footnote 133 Persico speaks to more than groupthink. He attests to the discursive context from which the drug laws emerged—the monopoly of the new policy image in which addicts were not deemed worthy of rehabilitation.

Furthermore, this “lack of vigilance and sloganistic thinking” followed, not led, indigenously constructed causal stories within the New York's black community. In the “lock-‘em-up-and-throw-away-the-key speech” in which Rockefeller outlines the drug laws, he appropriated the black vernacular when he said he was going to “tell it like it is,” and offered a veiled reference to news reports of black audiences continually “telling him like it is” on the issues of drugs and crime. Accordingly, when the governor identified protecting “law-abiding citizens” as the main purpose of the drug laws, the declaration lacked invidious racial distinctions. Rockefeller defined “citizens,” like so many African American leaders before him, in class terms—in moral terms.

This moral reasoning also permeated the statements of opponents. A brief colloquy during the debate over the drug laws between Vander Beatty, an African American senator from Brooklyn, and Robert Garcia, a Puerto Rican senator from the South Bronx, is instructive. Garcia said, “Look, I said last week, Senator, that as far as I am concerned, there are some junkies whom we will never be able to help, and they are no damn good, but the key is that we have to go after those people and try to help those people who have a chance, and that is all I'm doing.”Footnote 134 Notwithstanding his protestations, Garcia ceded much ground to the new causal story. His arguments carved out little policy space for the “deserving” addict while bolstering the basic logic of the punitive laws.

Although Beatty was the only black legislator to vote for the drug laws, the final vote tally concealed the monopoly of the causal story attached to them. By March of 1973, a consensus had emerged among minority legislators. Most of them embraced harsher methods, “such as mandatory life for major drug traffickers and compulsory treatment for addicts.”Footnote 135 For example, Queens Assemblyman Guy Brewer approved of mandatory life sentences for drug traffickers. Brewer was himself once a victim of crime. According to the assemblyman, drug addicts invaded his home and “walked off with various appliances and a considerable liquor stock that they packed off in my brand new suitcase.” Given his experience and his general understanding of the drug crisis, Brewer lamented: “You must understand . . . I cannot stand by and watch my community go down the drain.”Footnote 136 Frequently near tears during the debate on the bill, Assemblyman Woodrow Lewis of Brooklyn disputed the governor's claims, bemoaning that “efforts in matters of treatment had not been exhausted” and that “addicts are already imprisoned by the ills of our society.”Footnote 137

In Harlem, some were more skeptical. A public school principal believed that a “firmer stand” was needed, but she did not “want to violate the civil liberties of these people.”Footnote 138 According to her, Rockefeller's plan represented a purposeful attack on racial minorities: “I really feel it's another way of destroying us.”Footnote 139 “[W]e see him now for what he is,” a state employee said. He explained: “When [the Governor] starts talking about narcotics, he's talking about the minority population.” Echoing this sentiment, Barbara Jackson, an Africanist at the American Museum of Natural History, believed that the government was trying to “round up young black kids, young black boys and put them in concentration camps.”Footnote 140

Opponents, however, were in the minority. A poll taken in late 1973—after the passage of the controversial proposals and after the virtues of the laws would have been adjudicated in the mainstream and black press—confirmed the findings in previous polls: blacks were the group most concerned about crime and drugs and supported punitive solutions. Blacks (and Puerto Ricans) were least likely to describe their neighborhoods as safe or safer than other neighborhoods in the city, and 71 percent of blacks favored life sentences without parole for “pushers.”Footnote 141 Illuminating the contours of these attitudes, Beny Primm, director of Bedford-Stuyvesant's Addiction Research Treatment Corporation conceded, “I'm not a civil libertarian anymore when it comes to the destruction of lives. I hate to sound so conservative, man, but this is from five years in the field. I see it every day. People say, ‘Lock pushers up, even if they're my son or daughter.’”Footnote 142 A civil servant and a recent grandmother said “I'm very much a liberal and a militant most of the time, but in terms of [the governor's proposal] I'd like to see it happen.”Footnote 143 “I'm in favor of burning them alive,”Footnote 144 Les Matthews, columnist for the Amsterdam News, admitted. Dr. Benjamin Watkins, the “Mayor of Harlem,” disclosed that he had been robbed “at least six times” and had not used his car because his hubcaps would be stolen and “sold back to me.” Given these experiences, the “mayor” believed that the “harshest” approach would be necessary in order to “remove this contagion from our community.”Footnote 145 Only a few weeks after the passage of the law, the Amsterdam News called it “a powerful weapon against the wholesale use of drugs.” After describing the arrest of twenty-seven individuals charged with “dope conspiracy,” the piece avowed the legislation's appropriateness and timeliness: “This is what we need. This is what we want. This is the kind of police work which will make our city a better place to live.”Footnote 146 Despite some opposition, most middle-class African Americans endorsed a “firmer stand” and the removal of “this contagion” from their neighborhoods.

The drug laws, though certainly embraced by many African Americans, cannot be reduced simply to black politics. The punitive policies emerged from a complex configuration of forces, of which African American activism was a crucial part, and, deciphering the interaction of these variables requires isolating Rockefeller's motivations. Accomplishing this task demands attention to the specific timing of the measures: is it important to know why he promoted the drug laws when he did. As the traditional backlash model predicts, the measures passed after the political climate had shifted. By 1973, liberalism had grown unpopular, and the local and national political fortunes of Rockefeller had diminished by the end of the 1960s. When Rockefeller decided to run for an unprecedented fourth term as governor in 1970, Democratic polls exposed Rockefeller's weaknesses in four policy areas: “keeping taxes down, controlling narcotics addiction, aiding mass transportation, and providing adequate aid to cities.”Footnote 147 Local headwinds pushed “High Tax Rocky” to the right. In fact, the governor told friends that “he could not hope to hold the 35 percent of Jewish and Negro votes his polls showed him he had received in the past and that he would have to make up for them by increasing his vote in places like Bay Ridge and Buffalo.”Footnote 148 Rockefeller's local political future, then, rested in the hands of white ethnics increasingly disenchanted with liberalism. These electoral dynamics, however, do not explain the timing of the drug laws. If white backlash to liberalism drove policy change, then Rockefeller would have proposed the punitive drug laws earlier. To the extent that an inchoate white ethnic backlash was discernable, it was discernable well before Rockefeller proposed the drug laws; rightward shifts were apparent in 1968, but the drug laws were not proposed until 1973.

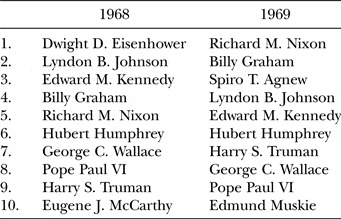

Perhaps the national electorate rather than the local electorate defined Rockefeller's incentives, as he coveted the White House more than the governor's mansion. And the national electorate had also changed. Table 2 suggests a dramatic ideological shift in the late 1960s. The Gallup Poll's 1968 list of the “Most Admired Men” displays the ideological diversity of the nation; it also betrays the nation's lingering liberal sensibilities. The 1969 poll announces the conservative turn. Rockefeller, who always pursued the national stage, realized conservative politicians and moral leaders had replaced the nation's liberal lions as the most admired men in the United States. But, once again, these data predict that the punitive drug laws would have been proposed much earlier than 1973.

Table 2. Most Admired Men in the United States

Source: “Nixon Heads List of Most ‘Admired Men,’” New York Times, 4 Jan. 1970, 53.

Ultimately, random events created an opportunity for the punitive measures. In March of 1972, Rockefeller ran into William Fine, president of a department store and chairman of a drug rehabilitation program, at a party. The governor asked Fine to visit Japan to learn why the nation had one of the lowest addiction rates in the world. Fine agreed, flew to Japan, spent a weekend meeting with health officials, and returned “with the apparent secret to the Japanese success against drugs—life sentences for pushers.”Footnote 149 He submitted his findings to the governor but received no response for two months. At another party attended by Fine, Rockefeller, and Ronald Reagan, the governor of California, Fine and Reagan discussed the trip. An intrigued Reagan requested the report. Fine then sought permission to share it with the governor of California. Rockefeller declined: “This thunderbolt was to be hurled by him.”Footnote 150 Not to be outdone by his main competition for the Republican nomination for president, Rockefeller soon unveiled the draconian laws inspired by Fine's fact-finding mission.

By the time chance encounters at parties had generated a draconian policy proposal and rushed the timetable for its release, “pushers” and addicts had already been made enemies of the state's “citizens,” and previous attempts at punishing pushers and disciplining addicts were considered failures. When Rockefeller decided to “tell it like it is”Footnote 151 in his address to the legislature in January of 1973, he captured the essence of the causal story attached to the punitive policy: “We have achieved very little permanent rehabilitation—and have found no cure.” He charged: “The crime, the muggings, the robberies, the murders associated with addiction continue to spread a reign of terror. Whole neighborhoods have been as effectively destroyed by addicts as by an invading army. We face the risk of undermining our will as a people—and the ultimate destruction of our society as a whole.”Footnote 152 Drug “pushers” deserved the maximum punishment. Because addicts were incorrigible and jeopardized the welfare of the state's citizens, they also deserved extreme punishment. Succumbing to their own class bias and motivated by material interests, black civic and political elites spent a decade drawing attention to what Persico called “the weakness and immorality” of the “outgroup” that was the urban black poor. As a result, they, more so than Irish Catholics in the state or national Republican elites, created a discursive context conducive to punitive crime policy. By the 1970s, the new causal story had achieved its monopoly because of black middle-class political and civic leaders “telling it like it is.” Ultimately, the confluence of this monopoly, Fine's fact-finding mission, and Republican Party politics produced the most punitive drug policy in American history in 1973.

HARLEM IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

The Harlem story is important in and of itself. To the extent that this punitive model spread across the country and was adopted by different levels of government, civic and political elites in Harlem played a crucial role in the development of a central policy feature of the modern carceral state. At the same time, the Harlem story is not all together unique. The socioeconomic forces that drove increases in crime rates and crime-related problems in New York City during the 1960s and 1970s also plagued other cities with large black populations.Footnote 153 Additionally, middle-class African Americans and black civic and political institutions and elites in these cities understood and responded to these shifts in similar ways as their counterparts in New York City.

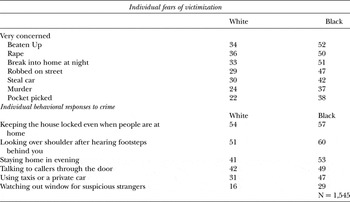

Baltimore is a case in point. In 1969, Jack Rosenthal, national urban affairs correspondent for Life magazine, penned a penetrating exposé on crime in Baltimore. Among many stunning observations, Rosenthal discovered that guard dogs, specifically German shepherds and Doberman pinschers, at a large pet store were selling fast and that African American families purchased 90 percent of the German shepherds.Footnote 154 The Harris survey of Baltimore residents commissioned for article is equally illuminative. Table 3 shows stark racial differences in individual perceptions of potential victimization and behavioral responses to perceived criminal threats. Over 50 percent of black respondents feared being beaten up, raped, or having their homes broken into, while only a little over 30 percent of whites feared they would experience these crimes. Almost 50 percent of black respondents feared being robbed on the street, while only 29 percent of whites shared this concern. Most startling, 37 percent of black respondents feared being murdered, while less than a quarter of whites expressed this fear. Unsurprisingly, these threats caused blacks and whites in Baltimore to alter their behavior—blacks more so than whites, however. Sixty percent of African American respondents reported looking over their shoulder when hearing footsteps, and over 50 percent of African American respondents reported, “staying home in evening” and “talking to callers through the door.”

Table 3. Individual Evaluations of and Response to Crime in Baltimore, 1969

Source: “The Improvement and Reform of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice in the United States,” Hearings before the Select Committee on Crime, United States House of Representatives, (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1969), 25–26.

The critical question then is: How did African Americans in Baltimore frame these experiences? What causal stories did they attach to them? In 1970, the Sun ran a story about residents in a black section of the city who were “caught in the overwhelming nightmare of heroin addiction, fear, and violence.”Footnote 155 The story opened with a quote from Mr. Frank Jenkins of the 300 block of East 21st Street: “If you want to buy heroin, all you have to do is put a $5 bill in your hand and walk down the street waving it.” His daughter chimed in: “The street is full of drug addicts. You can see them walking around with the [heroin] packets in their hands.”Footnote 156 William Chinn, who lived on a disability pension, bemoaned the neighborhood's condition: “There are a lot of dope addicts around here . . . I wish somebody would break it up.” Chinn, also from the 300 block of East 21st Street, groused: “A lot of people around here have lost television sets . . . The addicts will take anything they can pawn. I don't go out at night. There ain't nothing in the street, nothing but trouble.”Footnote 157 One woman, defending her decision to remain anonymous in the article, said: “It's not so much that we don't want to get involved, but we've got to live with these people. We don't know what they are going to do. They could kill us.”Footnote 158