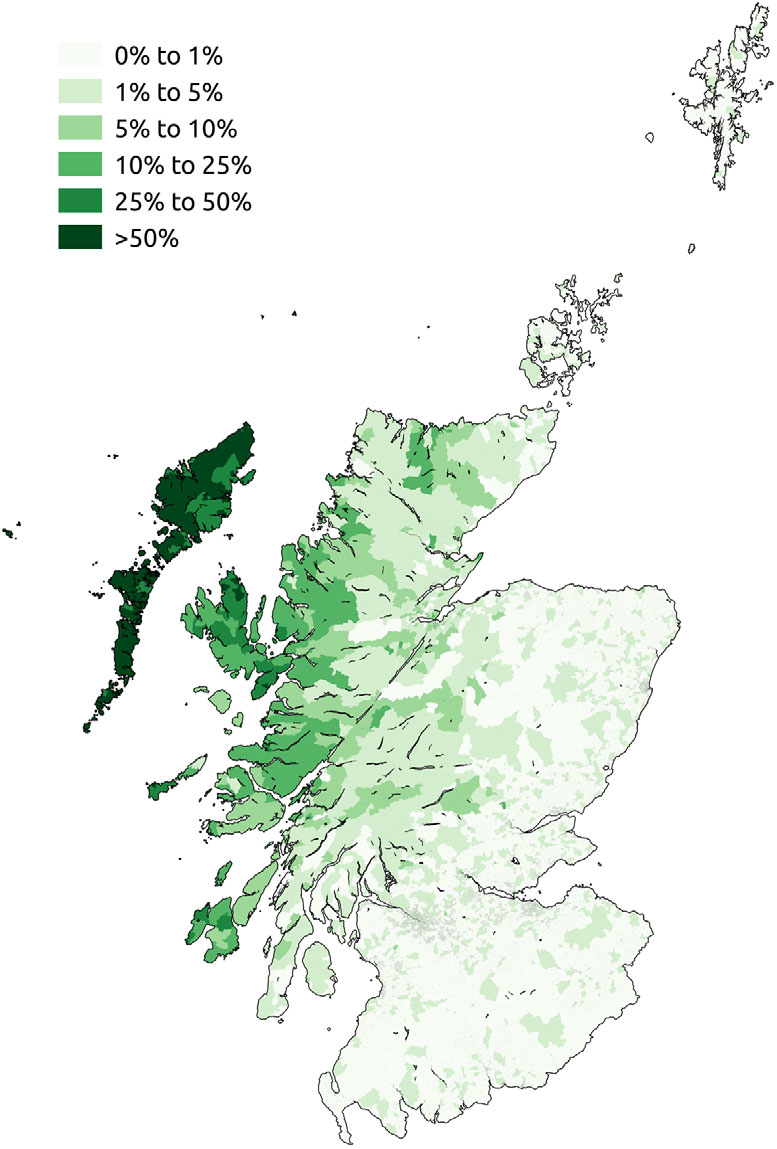

Scottish Gaelic is a minority language of Scotland spoken by approximately 58,000 people, or 1% of the Scottish population (speaker numbers from the 2011 Census available in National Records of Scotland 2015). Here, we refer to the language as ‘Gaelic’, pronounced in British English as /ɡalɪk/, as is customary within the Gaelic-speaking community. In Gaelic, the language is referred to as Gàidhlig /kaːlɪc/. Gaelic is a Celtic language, closely related to Irish (MacAulay Reference MacAulay1992, Ní Chasaide Reference Ní Chasaide1999, Gillies Reference Gillies, Martin and Nicole2009). Although Gaelic was widely spoken across much of Scotland in medieval times (Withers Reference Withers1984, Clancy Reference Clancy2009), the language has recently declined in traditional areas such as the western seaboard and western islands of Scotland and is now considered ‘definitely endangered’ by UNESCO classification (Moseley Reference Moseley2010). Analysis of the location of Gaelic speakers in Scotland and maps from the most recent Census in 2011 can be found in National Records of Scotland (2015). Figure 1 shows the location of Gaelic speakers in Scotland as a percentage of the inhabitants aged over three in each Civil Parish who reported being able to speak Gaelic in the 2011 Census.

A dialect of Gaelic in East Sutherland was once described as a prototypical case of language obsolescence (Dorian Reference Dorian1981) but the language is now undergoing significant revitalisation measures (e.g. McLeod Reference McLeod2006). These include the introduction of nursery, primary and secondary immersion schooling in Gaelic, as well as adult learning classes, more university degree courses, and many other public and private initiatives. Many of these activities are coordinated by the Gaelic Language Board (Bòrd na Gàidhlig), which was created as a result of the 2005 Gaelic Language Act (Scotland). The language act states that Gaelic holds the same legal status as English in Scotland.

The speaker in the speech samples associated with this contribution is a male in his fifties. He was born and raised in Ness, a Gaelic-speaking community in the north of the Isle of Lewis, and is currently working at the University of Glasgow. Lewis is the most northerly island in the chain of islands known as the Outer Hebrides, or the Western Isles. It is the part of Scotland where the densest concentration of Gaelic speakers resides (52% Gaelic-speaking according to the 2011 Census). His speech can be considered representative of the middle-aged generation of fluent traditional Lewis Gaelic speakers, with some more levelled features due to his time in Glasgow among speakers of other dialects. We have noted where his Lewis dialect diverges significantly from other Hebridean dialects. The recordings were made onto a laptop computer in the noise-attenuated sound studio at the University of Glasgow using a Beyerdynamic Opus 55 headset and a Sound Devices USBPre2 pre-amplifier and analogue-to-digital converter.

Figure 1. Percentage of people over the age of three able to speak Gaelic according to the 2011 Census.

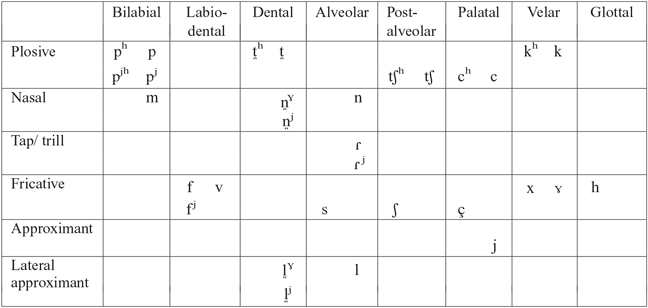

Consonants

Notes: 1. Non-palatalised consonants are shown in the top of the cell, and palatalised below.

2. Regarding the palatal Approximant, Oftedal (Reference Oftedal1956: 113) additionally reports a distinction in some speakers from the east coast of Lewis between /j/ and /ʝ/, for example in ionnsaich ‘teach, learn!’ /jɛ̃ũsɪç/ and dh’ionnsaich ‘taught, learned’ /ʝɛ̃ũsɪç/. Our participant is from the north-west of Lewis so does not make this distinction.

‘Broad’ and ‘slender’

Similar to Irish, Gaelic consonants have a palatalised and a non-palatalised series. These are often referred to as ‘slender’ and ‘broad’ consonants respectively in the Gaelic literature and teaching materials (e.g. MacAulay Reference MacAulay1992, Ó Maolalaigh & MacAonghuis Reference Ó Maolalaigh and Iain2008, Gillies Reference Gillies, Martin and Nicole2009, Bauer Reference Bauer2011). Several consonants do not take part in this alternation: /m v h/. Borgstrøm (Reference Borgstrøm1940: 17) suggests that no labial(-dental) consonants have the alternation in Scottish Gaelic but recent articulatory work on Irish confirms that in Irish /pʰ p f/ do have palatalised counterparts (Ní Chiosáin & Padgett Reference Ní Chiosáin and Jaye2012), so we follow their work and Ladefoged et al. (Reference Ladefoged, Jenny, Alice, Kevin and St.1998). See also Oftedal (Reference Oftedal1965) and MacAulay (Reference MacAulay1968) for further comments on this topic. In the Consonant Table above, we have shown the non-palatalised series on the top row of each cell, and the palatalised series on the bottom row where possible. Laterals, rhotics and alveolar/dental nasals are discussed separately below. The only sounds with actively velarised counterparts are laterals and dental/alveolar nasals, which are discussed separately below. Some accounts of Irish have suggested that some other non-palatalised sounds are velarised, specifically /pˠ bˠ fˠ mˠ t̪ˠ d̪ˠ sˠ/ (Ní Chasaide Reference Ní Chasaide1999: 35). This has not been reported for Gaelic, see Borgstrøm (Reference Borgstrøm1940: 17), Ladefoged et al. (Reference Ladefoged, Jenny, Alice, Kevin and St.1998: 3), Ternes (Reference Ternes2006:18), Gillies (Reference Gillies, Martin and Nicole2009: 239), Bosch (Reference Bosch, Moray and Michelle2010: 268–269). Ní Chiosáin & Padgett (Reference Ní Chiosáin and Jaye2012: 174) state that in Irish, the contrast is manifested as palatalised vs. non-palatalised before back vowels and palatalised vs. velarised before front vowels. In Irish, an example commonly cited is the contrast between buí ‘yellow’ /bˠi/ and bí ‘be!’ /bʲi/ (see Ní Chasaide Reference Ní Chasaide1999 for audio recordings). The analogous context in Gaelic is not produced with velarisation e.g. puing ‘point’ [pʰəin̪ʲc], buidhe ‘yellow’ [pui.ə], tuigsinn ‘understanding’ [t̪ʰikʃĩ], duine ‘anyone’ [t̪in̪ʲə], muinntir ‘people’ [məin̪ʲtʃʰəð], suidhe ‘sit’ [sui.ə].

The Gaelic broad/slender distinction manifests itself in a change of primary place of articulation for sounds produced further back than those discussed so far. For example, the palatalised dental/coronal stops are most commonly post-alveolar affricates, although some speakers produce alveolo-palatal affricates. Similarly, /ʃ/ is the palatalised counterpart to /s/. The palatalised counterparts to /kʰ/ and /k/ are produced as palatal stops /cʰ/ and /c/ respectively (e.g. Borgstrøm Reference Borgstrøm1940: 17). /x/ and /ç/ are a broad and slender pair respectively, as are /ɣ/ and /j/.

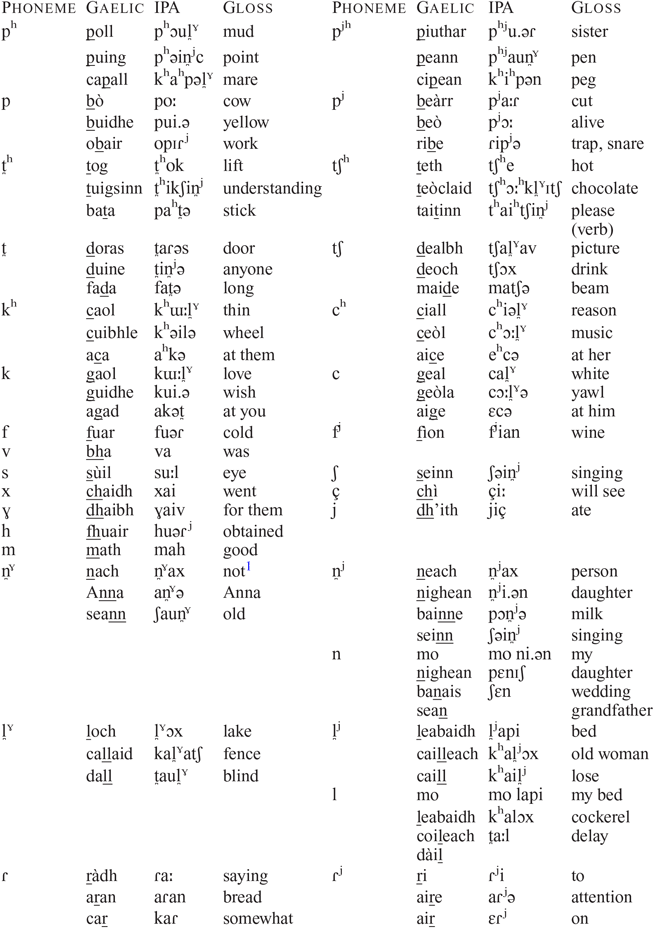

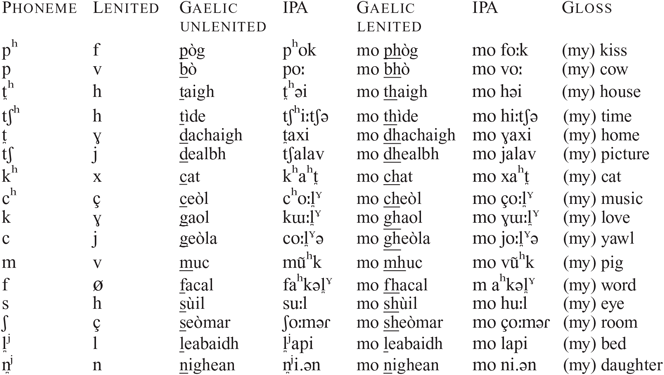

Initial consonant mutations

A feature common to all the Celtic languages is the existence of initial consonant mutations, a system of consonantal alternations under certain morphophonological conditions. The most common mutation in Gaelic, and the only one recognised in orthography, is lenition. This mutation occurs in contexts such as feminine singular nominative nouns after the definite article, adjectives modifying a feminine noun, the dative case with the definite article, and the vocative of proper nouns. For full details about the contexts where lenition occurs see Ó Maolalaigh (Reference Ó Maolalaigh1996) and Byrne (Reference Byrne2002). Examples of lenition mutations (in phonemic transcription) follow below. Where there are differences between broad and slender consonants, these are shown. Where not, the mutated variants are the same as those shown. The prefix mo means ‘my’ and causes lenition.

This list shows the broad transcription of lenited consonants; Archangeli et al. (Reference Archangeli, Sam, Jae-Hyun and Murial2014) note there may be phonetic differences between lenited and ‘underlying’ consonants i.e. incomplete neutralisation (see also Welby, Ní Chiosáin & Ó Raghallaigh Reference Welby, Máire and Brian2017 for incomplete neutralisation in Irish).

A second initial consonant mutation, not shown in orthography, and not realised in all dialects, is known as nasalisation or eclipsis. The phenomenon in Gaelic is somewhat different from the Irish phenomenon of eclipsis, which is recognised in orthography (Ó Maolalaigh Reference Ó Maolalaigh1996). In Gaelic, there is some dialectal variation in the realisation of eclipsis and its realisation is not obligatory. For details see Gillies (Reference Gillies, Martin and Nicole2009: 251–252) and Ó Maolalaigh (Reference Ó Maolalaigh1996). Eclipsis occurs after closely grammatically-related items such as nouns following the definite article an, or nouns immediately following a modifying adjective ending in a nasal consonant.

Aspiration

In word-initial position, stops are either voiceless unaspirated or voiceless post-aspirated. In word-medial and word-final position, the stop series are either voiceless unaspirated or voiceless pre-aspirated (Borgstrøm Reference Borgstrøm1940, Oftedal Reference Oftedal1956, Ladefoged et al. Reference Ladefoged, Jenny, Alice, Kevin and St.1998, Ó Maolalaigh Reference Ó Maolalaigh, Wilson, Abigail, Dòmhnall, Thomas and Roibeard2010, Nance & Stuart-Smith Reference Nance2013). Pre-aspiration is typically longest in velar/palatal stops and shortest in bilabials. The realisation of preaspiration varies from dialect to dialect. In Lewis it is typically a voiceless [h], but preaspiration can be more [x]-like, especially preceding velar stops in dialects such as Barra (see Ó Murchú Reference Ó Murchú1985). Instrumental evidence in Nance & Stuart-Smith (Reference Nance2013) suggests very little or no closure voicing even in word-medial stops which are orthographically b d g. For this reason, we follow Ladefoged et al. (Reference Ladefoged, Jenny, Alice, Kevin and St.1998) in stating that the contrast is one of aspiration rather than voicing and use the transcriptions /pʰ/ and /p/, etc.

Laterals, nasals and rhotics

Previous reports state that laterals, dental/alveolar nasals and rhotics participate in a three-way contrast (Borgstrøm Reference Borgstrøm1940; Oftedal Reference Oftedal1956; Ní Chasaide Reference Ní Chasaide and Dónall1979; Shuken Reference Shuken1980; Ladefoged et al. Reference Ladefoged, Jenny, Alice, Kevin and St.1998; Ternes Reference Ternes2006; Nance Reference Nance2013, Reference Nance2014). In earlier forms of Gaelic, it is hypothesised, there was a four-way distinction between these sounds. The alleged distinction was as follows: palatalised and velarised dental variants contrasted with palatalised and velarised alveolar variants, i.e. /l̪ʲ l̪ˠ lʲ lˠ/ (see e.g. Russell Reference Russell1995 76). This previous four-way distinction has reduced to a three-way distinction, or a two-way distinction in the case of rhotics, in most varieties of modern Gaelic (see Ternes Reference Ternes2006: 19 for details). We refer to the three sounds as ‘palatalised’, ‘velarised’ and ‘alveolar’ as shorthand for their full descriptions.

Laterals

The laterals in modern Gaelic are a velarised dental lateral, a palatalised dental lateral, and an alveolar lateral. Following static palatographic work in Shuken (Reference Shuken1980) and Ladefoged et al. (Reference Ladefoged, Jenny, Alice, Kevin and St.1998), and descriptions in Borgstrøm (Reference Borgstrøm1940) and Oftedal (Reference Oftedal1956), we consider the palatalised lateral as palatalised, rather than palatal. Acoustically, the velarised lateral is characterised by low F2 and high F1, the palatalised lateral by high F2 and low F1, and the alveolar lateral lies in between these two extremes (Shuken Reference Shuken1980; Ladefoged et al. Reference Ladefoged, Jenny, Alice, Kevin and St.1998; Nance Reference Nance2013, Reference Nance2014).

In word-initial position, our speaker produces three laterals: the velarised and palatalised laterals differ substantially e.g. loch ‘lake’ /l̪ˠɔx/ and leabaidh ‘bed’ /l̪ʲapi/. Very few lexical items, excluding recent borrowings, begin with the alveolar lateral, but this can be derived through the lenition mutation. Generally speaking, the velarised and palatalised laterals, nasals and rhotics lose their secondary articulations in lenition conditions. For example, the lenited palatalised lateral becomes alveolar e.g. leabaidh ‘bed’ /l̪ʲapi/ but mo leabaidh ‘my bed’ /mo lapi/. It has been reported that a lenited velarised lateral will become alveolar, but our speaker did not make this distinction. In word-medial position, there is a straightforward three-way contrast e.g. callaid ‘fence’/kʰal̪ˠatʃ/, coileach ‘cockerel’ /kʰalɔx/, cailleach ‘old woman’ /kʰal̪ʲɔx/. Similarly, there is a three-way contrast in word-final position e.g. dall ‘blind’ /t̪aul̪ˠ/, dàil ‘delay’ /t̪aːl/, caill ‘lose’ /kʰail̪ʲ/.

Nasals

Borgstrøm (Reference Borgstrøm1940) and Shuken’s (Reference Shuken1980) static palatography study describe the articulation of the three (dental/alveolar) nasals as /n̪ˠ/, /n/ and /n̪ʲ/. Velar and palatal variants of these sounds occur in the context of /k/ and /c/, e.g. long ‘ship’ [l̪ˠãũŋk] and taing ‘thanks’ [t̪ʰãĩɲc]. As these are the only contexts where [ŋ] and [ɲ] occur, we consider them as allophones of /n̪ˠ/ and /n̪ʲ/ respectively (see also Borgstrøm Reference Borgstrøm1940: 77).

In word-initial position, there is a contrast between velarised and palatalised nasals, e.g. nach ‘not’ /n̪ˠax/, and neach ‘person’ /n̪ʲax/. Very few lexical items begin with alveolar nasal, but this can be derived through lenition. The lenitied palatalised nasal becomes alveolar e.g. nighean ‘daughter’ /n̪ʲi.ən/, mo nighean ‘my daughter’ /mo ni.ən/. Theoretically, the lenited velarised also becomes alveolar, but our speaker did not make this distinction. In word-medial position, there is a three-way contrast e.g. Anna ‘Anna’ /an̪ˠə/, banais ‘wedding’ /bɛnɪʃ/, bainne ‘milk’ /bɔn̪ʲə/. In word-final position, there is a three-way contrast e.g. seann ‘old’ /ʃaun̪ˠ/ (produced here as [ʃãũn̪ˠ] with a very short final nasal), sean ‘grandfather’ /ʃɛn/, seinn ‘singing’ /ʃəin̪ʲ/.

Rhotics

The rhotics also historically participated in the three-way distinction between velarised, alveolar and palatalised phonemes (Borgstrøm Reference Borgstrøm1940, Oftedal Reference Oftedal1956). Traditional descriptions indicate that the velarised rhotic is produced as a velarised trill (Borgstrøm Reference Borgstrøm1940, Oftedal Reference Oftedal1956), but most speakers now produce the velarised/alveolar rhorics as taps or approximants, and trills are very rare in contemporary production (Ó Dochartaigh Reference Ó Dochartaigh1997, Nance et al. Reference Nance, Wilson, Bernadette and Stuart2016). The palatalised rhotic is often produced as a dental fricative [ð] in Lewis and in other dialects. There is, however, substantial variation across dialects in the production of this sound, with many dialects and individuals producing some kind of tap or fricated tap (Ó Dochartaigh Reference Ó Dochartaigh1997). We have represented the current two-way contrast as a distinction between /ɾ/ and /ɾʲ/ but it should be noted that there is substantial variation in the production of these sounds.

In word-initial position, the palatalised variant is almost non-existent so the contrast is effectively neutralised. The preposition ri ‘to’ /ɾʲi/ is reported to use the palatalised variant, but our speaker did not produce this rhotic substantially different to the rhotic in, for example, ràdh ‘saying’ /ɾaː/. In word-medial position, there is a two-way contrast e.g. aran ‘bread’ /aɾan/, aire ‘attention’ /aɾʲə/ (produced as [aðə]). In word-final position there is also a two-way contrast e.g. car ‘somewhat’ /kʰaɾ/, air ‘on’ /ɛɾʲ/ (produced as [ɛð]).

In the dialect presented here, clusters with rhotics, dental/alveolar stops, laterals, and nasals tend to be produced as retroflex, and the rhotic as a retroflex approximant, e.g. thuirt ‘said’ [hʉɽʈ]. In -rs clusters, the rhotic and sibilant are often produced as retroflex, e.g. carson ‘why’ [kʰaɽʂɔn]. In the vast majority of other Gaelic dialects, an audible [ʃ] or [ʂ] occurs in -rt clusters, e.g. thuirt ‘said’ [hʉɽʂʈ]; in some dialects this also occurs in -rd (Watson Reference Watson1990).

Vowels

Monophthongs

Gaelic has nine oral monophthongs, which can be long or short. Acoustic measures of the first two formants in the monophthongs from the sample words in this Illustration are shown in Figure 2 below. For acoustic analysis of a larger dataset focussing on the high back vowels, see Nance (Reference Nance2011).

Figure 2. Formant measurements of the Gaelic monophthongs (Bark).

Long vowels are indicated by an accent grave in orthography. Generally, the long vowels are of similar acoustic quality to the short vowels, although they tend to be slightly more peripheral. The ‘high back’ vowels /ɤ ɯ/ are acoustically more central, or even front in the dialect represented here (Nance Reference Nance2011). Borgstrøm (Reference Borgstrøm1940: 11) describes these vowels as phonologically, rather than phonetically, back. The two previous dialect descriptions of Lewis Gaelic, Borgstrøm (Reference Borgstrøm1940) and Oftedal (Reference Oftedal1956), do not use the modern IPA. We follow Ladefoged et al. (Reference Ladefoged, Jenny, Alice, Kevin and St.1998) in interpreting their symbols as /ɤ/ and /ɯ/. The vowel /u/ has two allophones: back [u̠], occurring in the environment of velarised sonorants, and central [ʉ], occurring elsewhere, e.g. sùil ‘eye’ [sʉːl], but ubhal ‘apple’ [u̠.əl̪ˠ]. The formant distribution of these two allophones is strikingly different; see Ladefoged et al. (Reference Ladefoged, Jenny, Alice, Kevin and St.1998) and Nance (Reference Nance2011). Similarly, /a/ is auditorily [ɑ] in the environment of velarised sonorants, e.g. latha ‘day’ [l̪ˠɑ.ə], but leat ‘at you’ [laʰt]. Long /ɛː/ is not common and has merged with /eː/ for some speakers, including our participant. In Lewis, a group of words containing orthographic ea before g are pronounced with /ɤ/, but /ɛ/ or /e/ in other dialects, e.g. beag ‘small’ [pɤk], eaglais ‘church’ [ɤkl̪ˠɪʃ].

Nasal monophthongs

There are disagreements in the literature on the number of nasal vowels in Gaelic, and their nature. Borgstrøm (Reference Borgstrøm1940: 13) reports five short nasal vowel phonemes, and six long nasal vowel phonemes. Oftedal (Reference Oftedal1956: 40), who was reporting on a dialect on the eastern side of Lewis, describes nine short and seven long nasal vowel phonemes. It is also important to note that Borgstrøm and Oftedal recorded participants born in the 1880s and before, and thus their reports may not represent the contemporary situation. Oftedal (Reference Oftedal1956: 40) notes that nasality in vowels in ‘one of the most elusive features’ of the phonemics of the dialect under investigation, and suggests that nasality has ‘little distinctive value’, referring to its very low functional load. Similarly, Borgstrøm (Reference Borgstrøm1940: 13) states that nasality has ‘not a great functional value’. The degree of nasality appears to vary from dialect to dialect and is also to some extent speaker-specific. Oftedal (Reference Oftedal1956: 41) notes that even between two of his participants, who were from the same village and married, there was great variation in the degree of nasality among their vowels. One person, he claimed, had nasal vowels perceptibly similar to nasal vowels in French, whereas the other speaker had nasal vowels similar to a speaker of General American (see also Ó Curnáin Reference Ó Curnáin2007 for analysis of individuals in Irish). An impressionistic auditory analysis of our sample sound files suggests that there are variable amounts of nasality in different words, shown (in phonemic transcription) in the following list (potentially nasal vowels are underlined):

See Morrison (Reference Morrison2015) and Warner et al. (Reference Warner, Daniel, Jessamyn, Andrew, Muriel and Michael2015) for analysis of nasal airflow data. The quality of the nasal vowels is similar to that of their oral counterparts, presented in Figure 2 above; hence we do not offer a separate nasal vowel quality figure here.

Nasal vowels in Gaelic generally arose due to coarticualtion with an original nasal consonant, e.g. tàmh ‘rest’ /t̪ʰãːv/. In this word, the orthographic m suggests that there was a bilabial nasal consonant historically, which is no longer pronounced. See Ó Maolalaigh (Reference Ó Maolalaigh2003) for an account of nasalisation processes in Gaelic. Some accounts suggest that the final fricative in words such as tàmh is also nasalised (Borgstrøm Reference Borgstrøm1940, Ternes Reference Ternes2006), but aerodynamic work suggests that this is not the case phonetically (see Warner et al.’s Reference Warner, Daniel, Jessamyn, Andrew, Muriel and Michael2015 work on Skye, but see also Morrison Reference Morrison2015), and it has been suggested that these are unlikely in articulatory terms (Ohala Reference Ohala, Charles, Larry and John1975: 300).

Diphthongs

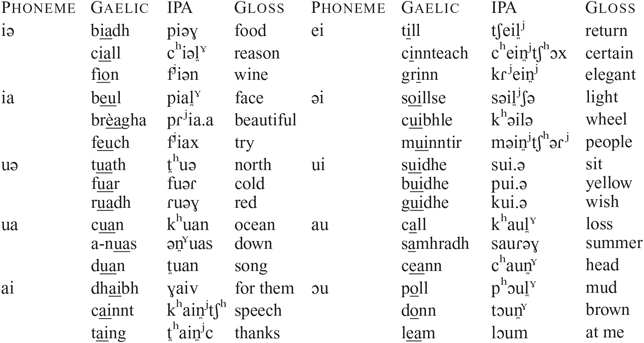

Gaelic has a rich diphthongal system. Borgstrøm (Reference Borgstrøm1940: 37) describes 14 phonemic diphthongs, /ai ɛi ei ui ɤi au ɛu ɔu iə ia iɛ uə ua uɛ/, and Oftedal (Reference Oftedal1956: 44) describes 10, /ei ui əi ai ɔu au iə ia uə ua/. We find that Oftedal’s account best describes contemporary Gaelic. Sample words are listed above (in phonemic transcription).

These two previous descriptions do not specifically mention whether or not nasality in diphthongs should be considered a phonemic aspect or not. However, both give examples of nasal diphthongs. We asked our speaker to produce a large number of words listed by Borgstrøm and Oftedal as containing nasal diphthongs, but they were not consistently audibly nasal. We consider the contemporary situation to be that some words contain diphthongs with nasalisation, but nasalised diphthongs are not phonemic in the language.

Prosody

Syllables, svarabhakti and hiatus

Gaelic syllable structure has been described as typically VC rather than the typologically much more common CV (Clements Reference Clements, Koen and Harry1986, Bosch Reference Bosch1998, Smith Reference Smith, Harry and Elizabeth1999). See Ní Chiosáin, Welby & Espesser (Reference Ní Chiosáin and Jaye2012) for experimental work on syllabification in Irish and similar discussion. Two classes of Gaelic words will be described in more detail here because they behave unusually within Gaelic phonology: words containing a svarabhakti vowel, and ‘hiatus’ words. Certain consonant sequences in Gaelic are broken up by a svarabhakti vowel, which is not represented in the orthography, e.g. arm ‘army’ [aɾam], ainm ‘name’ [anam], balg ‘belly’ [pal̪ˠak], dorcha ‘dark’ [t̪ɔɾɔxə], Alba ‘Scotland’ [al̪ˠapə]. Usually the svarabhakti vowel is a copy of the preceding vowel (Borgstrøm Reference Borgstrøm1940, Clements Reference Clements, Koen and Harry1986, Bosch & de Jong Reference Bosch and Kenneth1997, Hall Reference Hall2006). Svarabhakti vowels in Gaelic occur where (i) the consonant preceding the svarabhakti vowel is a sonorant, (ii) the preceding vowel is short, (iii) the consonant cluster is non-homorganic, and (iv) the second consonant is not a pre-aspirated plosive. Previous descriptions state that svarabhakti vowels do not contribute to the syllable count of a word, e.g. falbh ‘going’ [fal̪ˠav] is monosyllabic, but falamh ‘empty’ [fal̪ˠ.u] is disyllabic (Borgstrøm Reference Borgstrøm1940, Oftedal Reference Oftedal1956, Bosch Reference Bosch1998). Recent experimental work (Hammond et al. Reference Hammond, Natasha, Andrew, Diana and Muriel2014) suggests that speaker perceptions are more complex: words such as falbh were perceived as not quite monosyllabic, but not quite disyllabic either. The svarabhakti vowels are described as stressed, which is unusual for stress-initial Gaelic and also typologically (Borgstrøm Reference Borgstrøm1937: 77; Bosch & de Jong Reference Bosch and Kenneth1997).

‘Hiatus’ words in most cases refer to a class of words in which historic intervocalic consonants are no longer pronounced, e.g. leabhar ‘book’ [l̪ʲɔ.əɾ] compared to gu leòr ‘enough’ [kə l̪ʲɔːɾ], rathad ‘road’ [ɾa.ət̪] compared to ràdh ‘saying’ [ɾˠaː]. In the word accent system of (Lewis) Gaelic (see below), words with a svarabhakti vowel such as falbh ‘going’ [fal̪ˠav] are produced with the accent for monosyllabic words and words with hiatus such as leabhar ‘book’ [l̪ʲɔ.əɾ] are produced with the accent for polysyllabic words. In other dialects, hiatus is produced with an inserted glide, a period of creaky voice or a glottal stop (Holmer Reference Holmer1938; Jones Reference Jones2000; Ternes Reference Ternes2006: 138).

Tone, intonation and stress

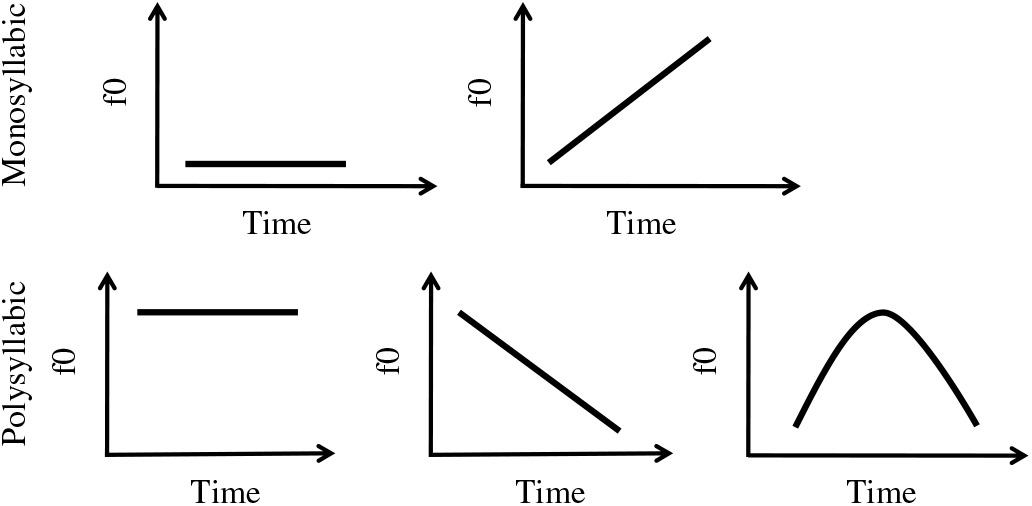

The Lewis dialect of Gaelic, along with north-west mainland dialects such as Applecross, is described as having contrastive word accents (Borgstrøm Reference Borgstrøm1940, Oftedal Reference Oftedal1956, Dorian Reference Dorian1978, Bosch & de Jong Reference Bosch and Kenneth1997, Ladefoged et al. Reference Ladefoged, Jenny, Alice, Kevin and St.1998, Ternes Reference Ternes2006, Iosad Reference Iosad, Janet, Christine, Jan-Ola and Michael2015, Nance Reference Nance2015a, Morrison Reference Morrison2019). Southern Hebridean and other mainland dialects are not reported to use this prosodic feature (see Ternes Reference Ternes2006: 138 for details). Ternes (Reference Ternes2006) provides the most extensive description of the Lewis Gaelic system. In this account, word accents correspond to differences in syllabicity: monosyllabic words have a rising or level low pitch, whereas polysyllabic words have a level high pitch, falling pitch, rising–falling pitch. This is schematised in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Schematised pitch traces for Gaelic word accents.

In general, speakers are often not consciously aware that their dialect uses pitch contrastively. When Gaelic is taught, the dialects of Skye or Uist are used as models, so tone is rarely, if ever, explicitly taught. Example pairs of words illustrating the word accent contrast are given below (in phonemic transcription). Monosyllabic words are to the left, polysyllabic comparison words to the right.

Spectrograms of the contrast between falbh ‘going’ [fal̪ˠav] and falamh ‘empty’ [fal̪ˠ.u] are shown in Figure 4. Analysis of the word accent system from a corpus of spontaneous speech is presented in Nance (Reference Nance2013, Reference Nance2015a).

In terms of sentence intonation, the default pattern in declaratives is a fall in pitch (Oftedal Reference Oftedal1956: 36; Dorian Reference Dorian1978: 37; MacAulay Reference MacAulay and Dónall1979). Borgstrøm (Reference Borgstrøm1940: 53) additionally states that if the last syllable has a (lexical) rising word accent, the rise is often very reduced. MacAulay’s (Reference MacAulay and Dónall1979) descriptive account of common pitch patterns in Lewis intonation suggests that interrogatives may be realised with rising pitch.

In the vast majority of Gaelic words, the word-initial syllable is stressed. Exceptions are generally borrowings, such as buntàta [punˈt̪ʰaːʰt̪] ‘potatoes’, and some adverbs, such as an-diugh ‘today’ [ənˈtʃʉ] and days of the week, e.g. Didòmhnaich ‘Sunday’ [tʃiˈtõː.niç]. Words containing a svarabhakti vowel (see above) are unusual in terms of stress and it has been claimed that both vowels bear stress (Bosch & de Jong Reference Bosch and Kenneth1997).

Figure 4. Spectrograms and pitch traces illustrating the word accent contrast between falbh ’going’ (monosyllabic) vs. falamh ‘empty’ (polysyllabic).

Airstream mechanisms

A final notable feature of Gaelic prosody is the extensive use of the ingressive airstream mechanism, especially in the last word of a phrase and discourse markers expressing agreement (Lamb Reference Lamb2003, Thom Reference Thom2005, Eklund Reference Eklund2008). This use of ingressives is informally referred to as the ‘Gaelic gasp’.

Sociolinguistic variation

Gaelic’s endangered and minority status means that the language is susceptible to rapid and extensive change. This illustration discusses the phonetic and phonological characteristics of conservative Gaelic as spoken by older or middle-aged speakers from (at least formerly) Gaelic-dominant communities. Younger speakers may sound substantially different to the variety of Gaelic described here. For example, nasal vowels are rare in the speech of younger speakers (see also Ó Curnáin Reference Ó Curnáin2007: 333 for Irish). The word-accent system described above is not used by younger speakers from any background (Nance Reference Nance2015a, b). Some younger speakers do not produce the three-way lateral contrast (Nance Reference Nance2014, Nance published online 14 February 2019).

Transcription of the recorded passage

Phonemic transcription

va ə ɣɯː ə t̪ʰuə akəs ə ɣɾʲiən ə tʃɛspət̪ kʰoː aʰkə ə pu t̪ʰɾɛsə n̪ˠuəɾʲ ə n̪ˠɔxk n̪ʲax ʃu.əl ə va ɛɾʲ ə xoː̃t̪əx aun̪ˠ ən kʰloːʰkə pl̪ˠaː ‖ ɣɯːn̪ˠt̪ʰɪç iət̪ kə pɾʲi kʰoː ə vɛɾʲəɣ ɛɾʲ ən n̪ʲax ʃu.əl ə xloːʰkə ə xuɾ je ən̪ˠ t̪ʰɔʃɔx kəɾ i ə viɣ ka mɛs na pə t̪ʰɾɛsə na ən tʃʰeː elə ‖ ən uəɾʲ ʃɪn heːtʃ ə ɣɯː ə t̪ʰuə xɔ l̪ˠaːtʃɪɾʲ s ə purɪn̪ʲ ji ax maɾ ə pə võ.ə ə heːtʃ i paun̪ˠ na pə tʃʰen̪ʲə ə façkəɣ ə n̪ʲax ʃu.əl ə xloːʰkə tʃʰimɪçəl̪ˠ ɛɾʲ heːn ɤkəs mu jɛɾʲəɣ lec ə ɣɯː ə t̪ʰuə ʃaxət̪ ən ɤɾʲʰpʲ ‖ ən uəɾʲ ʃɪn jaːrs ə ɣɾʲiən əmax kə pl̪ˠaː ɤkəs sə vat̪ xuɾʲ ə n̪ʲax ʃu.əl je ə xloːʰkə ‖ ɤkəs maɾ ʃɔn peːt̪əɾ t̪ɔn ɣɯːi ə t̪ʰuə atʃɔxəɣ kəm pi ə ɣɾʲian ə pə t̪ʰɾɛsə jɛn tʃi.iʃ aʰkə ‖

Orthographic version

Bha a’ ghaoth a tuath agus a’ ghrian a’ deasbad cò aca a bu treasa nuair a nochd neach-siubhail a bha air a chòmhdach ann an cleòca blàth. Dh’aontaich iad ge brith cò a bheireadh air an neach-siubhail a chleòca a chur dheth an toiseach gur i a bhiodh ga meas na bu treasa na an tè eile. An uair sin shèid a’ ghaoth a tuath cho làidir ’s a b’urrainn dhi, ach mar a bu mhotha a shèid i b’ ann na bu teinne a phaisgeadh an neach-siubhail a chleòca timcheall air fhèin agus mu dheireadh leig a’ ghaoth a tuath seachad an oidhirp. An uair sin dheàrrs a’ ghrian a-mach gu blàth agus sa bhad chuir an neach-siubhail dheth a chleòca. Agus mar sin, b’fheudar don ghaoith a tuath aideachadh gum b’ i a’ ghrian a bu treasa den dithis aca.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to our speaker for contributing the recordings, to Sm Innes (University of Glasgow) for assistance in preparing the translation of the North Wind and the Sun passage, and to Cassie Smith-Christmas (University of Galway) for comments on the materials used. Thank you to Glasgow University Laboratory of Phonetics for use of their facilities while recording. Thank you to Amalia Arvaniti, the anonymous reviewers, Sam Kirkham and Adrian Leeman for their helpful and constructive comments.

Supplementart material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S002510031900015X.