Several general population surveys (Reference Regier, Narrow and RaeRegier et al, 1993; Reference Jenkins, Lewis and BebbingtonJenkins et al, 1997; Reference Bijl and RavelliBijl & Ravelli, 2000; Reference Andrews, Henderson and HallAndrews et al, 2001a ; Reference Andrade, Caraveo-Anduaga and BerglundAndrade et al, 2003, Reference Kessler, Berglund and DemlerKessler et al, 2003; Reference Demyttenaere, Bruffaerts and Posada-VillaDemyttenaere et al, 2004) have indicated a high prevalence of mental disorders. In addition, many individuals with mental disorders report not using health services for their mental disorder (Reference Regier, Narrow and RaeRegier et al, 1993; Reference BebbingtonBebbington, 2000; Reference Demyttenaere, Bruffaerts and Posada-VillaDemyttenaere et al, 2004). These data have raised concerns about potentially high levels of unmet need for mental healthcare. Studies of such unmet needs have taken place in the USA (Reference Regier, Narrow and RaeRegier et al, 1993; Reference Kessler, Demler and FrankKessler et al, 2005), Canada (Reference Lin, Goering and OffordLin et al, 1996), the UK (Reference BebbingtonBebbington, 2000), The Netherlands (Reference Bijl and RavelliBijl & Ravelli, 2000), Australia (Reference Andrews, Henderson and HallAndrews et al, 2001a ) and Northern Ireland (Reference McConnell, Bebbington and McClellandMcConnell et al, 2002) and have found levels of unmet need in the population ranging from 3.6% in Northern Ireland (Reference McConnell, Bebbington and McClellandMcConnell et al, 2002) to 15.5% in The Netherlands (Reference Bijl and RavelliBijl & Ravelli, 2000). However, we should be wary about making comparisons between studies because of the variability in the methods and designs used.

Determining the need for care is a complex process (Reference AndersenAndersen, 1995), and the ‘mere’ presence of a mental disorder may not, in fact, indicate a need for care. Some authors have suggested that it is necessary to measure not only the presence of mental disorders but also the clinical significance of those disorders in terms of their impact (Reference Narrow, Rae and RobinsNarrow et al, 2002). At the population level, need has also been defined as the population's ability to benefit from services, rather than being a question of demand and supply (Reference Stevens and RafteryStevens & Raftery, 1994). However, the problem with this definition is that there is no good public health indicator of the impact of treatment (Reference Aoun, Pennebaker and WoodAoun et al, 2004). All of these issues complicate the definition and measurement of need for healthcare.

In this paper, we use data from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project to estimate the level of unmet need for mental healthcare from a population-based perspective. We considered there to be a need for mental healthcare only if a 12-month mental disorder had been present and it was disabling or had led to use of health services in the year prior to the interview. Our contribution to previous work is to estimate need for mental healthcare in a large and diverse sample of the general population using a feasible and conceptually sound measure of unmet need.

METHOD

A detailed description of the ESEMeD project is provided elsewhere (Alonso et al, Reference Alonso, Angermeyer and Bernert2004a ,Reference Alonso, Angermeyer and Bernert b ). Briefly, this was a cross-sectional, home-based, computer-assisted personal interview study of representative samples of the non-institutionalised adult population (aged 18 years or older) of Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands and Spain (representing about 213 million Europeans). A stratified, multistage, clustered area probability sample design was used. In total, 21 425 respondents provided data for the project between January 2001 and August 2003. The relevant institutional review boards in each country approved the research protocol. The overall response rate for the six countries was 61.2%, with the highest rates in Spain (78.6%) and Italy (71.3%) and the lowest in France (45.9%) and Belgium (50.6%). The project is part of the World Health Organization (WHO) World Mental Health Survey Initiative (Reference Kessler and UstunKessler & Ustun, 2004).

A two-stage interview procedure was used. In phase 1, respondents were screened and asked additional questions for the assessment of some mood and anxiety disorders as well as detailed questions about their use of health services, health status and main demographic characteristics. In phase 2, only individuals found to have specific mood and anxiety symptoms at phase 1 (‘high-risk’ individuals) plus a 25% random subsample of respondents without these symptoms (‘low-risk’ individuals) were asked about additional disorders, health-related information and risk factors. In this paper we present data only from respondents who completed phase 2 of the interview schedule (n=8796).

Measures

Mental disorders

We used the CIDI 3.0 (Reference Kessler and UstunKessler & Ustun, 2004), a modified version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI; Reference WittchenWittchen, 1994) to identify respondents with any of the following:

-

(a) mood disorders (major depressive episode and dysthymia);

-

(b) anxiety (social phobia, specific phobia, generalised anxiety disorder, agoraphobia with or without panic disorder, panic disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder);

-

(c) alcohol abuse or dependence.

The CIDI 3.0 was developed by the World Mental Health Survey Consortium (Reference Kessler and UstunKessler & Ustun, 2004) and analytic algorithms for the instrument are periodically reviewed. Prevalences were estimated for the following mutually exclusive mental morbidity groups: any 12-month disorder; any lifetime disorder (but not a 12-month disorder); any lifetime sub-threshold morbidity; and no lifetime disorder (including no sub-threshold mental morbidity) (Reference Pincus, Davis and McQueenPincus et al, 1999). In this paper the latest available version of the analytical diagnostic algorithms for the CIDI 3.0 were used (updated September 2006).

Need for mental healthcare

Individuals who reported that their mental disorder had interfered ‘a lot’ or ‘extremely’ with their lives or their activities or who had used formal healthcare services in the 12 months prior to the interview for their disorder were defined as having a need for mental healthcare services. These criteria were considered to ensure that a conceptually sound indicator of healthcare need was used which would also be appropriate for the general population. An approximation of the validity of this definition was assessed by comparing the health-related quality of life, measured by the 12-item Short Form Health Survey (SF–12; Reference Ware, Kosinski and KellerWare et al, 1996), and the disability days, measured by the WHO Disability Assessment Schedule II (DAS–II; Chwastiak et al, 2003), with the other mental morbidity groups.

Use of health services and unmet need for mental healthcare

All respondents were asked to report their lifetime use of healthcare services for their ‘emotions or mental health’, as well as their use of such services in the 12 months prior to the interview. Individuals reporting any such use of services were then asked to select whom they had consulted from a list of formal healthcare providers (psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker, counsellor, general family doctor or any other medical doctor) and informal providers (e.g. religious or spiritual advisors or other healers). For each of the providers consulted, participants were asked about the number of visits they had made in the previous 12 months. Two levels of health services utilisation were specified: use of any formal health services; and visits to any mental health specialist (psychiatrist, psychologist, social worker or counsellor). Unmet need for mental healthcare was defined as the lack of use of any formal healthcare among individuals defined as having a need for care. This is a low-threshold definition, since evidence-based guidelines require a more intensive use of services to consider that care received is appropriate (Reference Wang, Demler and KesslerWang et al, 2002).

Other measures

Information on chronic physical conditions was collected for all participants who had received the second part of the interview schedule. Information collected included presence of the condition in the previous 12 months, the degree of interference with daily life and the number of visits to health services because of the condition. Respondents were also asked to complete the SF–12 and the work loss days scale of the WHO DAS–II. The SF–12 consists of 12 items which measure eight dimensions of health and produces a physical component summary score and mental component summary score. The original US population weights (Reference Ware, Kosinski and KellerWare et al, 1996) were used to derive the two summary measures, and the final scores were normalised and transformed to a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10 for the overall ESEMeD sample. Mean values above and below 50 represent better and worse health status respectively compared with the general population of the six countries studied here. The work loss days index is a self-report instrument, measuring the proportion of days in the previous 4 weeks that an individual was totally unable to work or carry out normal activities, or had to cut down on the quality or quantity of work because of physical health, mental health or use of alcohol or drugs. Scores range from 0 to 100, with higher scores representing greater impairment.

Statistical analysis

The proportion of individuals using health services (any formal health services or mental specialists) in the previous 12 months and the mean number of visits per individual were estimated for each mental morbidity category. Individuals’ data were weighted to account for the known probabilities of selection as well as to restore age and gender distribution of the population within countries and the relative dimension of the population across countries (Reference Alonso, Angermeyer and BernertAlonso et al, 2004a ).

Logistic regression analyses were carried out to assess the likelihood of not using mental healthcare in the previous 12 months. Two models were built. The dependent variable was, for the first model, unmet need (the lack of use of any formal health services) and for the second model it was the lack of use of mental specialists. Both models were restricted to individuals who needed mental healthcare in the previous 12 months. Variables included in the model were socio-demographic (age, gender, education, marital status, urbanicity, employment, income and country) and clinical (years since onset of the first mental disorder). In addition, we considered whether or not the individuals had a chronic physical condition, since this might modify the likelihood of using health services for mental reasons. The corresponding odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals were estimated, adjusting by socio-demographic and clinical variables. We tested the interactions among all variables judged to be relevant and the adjusted odds ratios were computed when significant. Data were analysed using SAS version 8 for Windows and SUDAAN software version 8.01 was used to estimate standard errors and regression coefficients using the Taylor series linearisation method (Reference Shah, Barnwell and BielerShah et al, 1997). Data analyses were carried out at the ESEMeD data analysis centre of the Institut Municipal d'Investigació Mèdica.

RESULTS

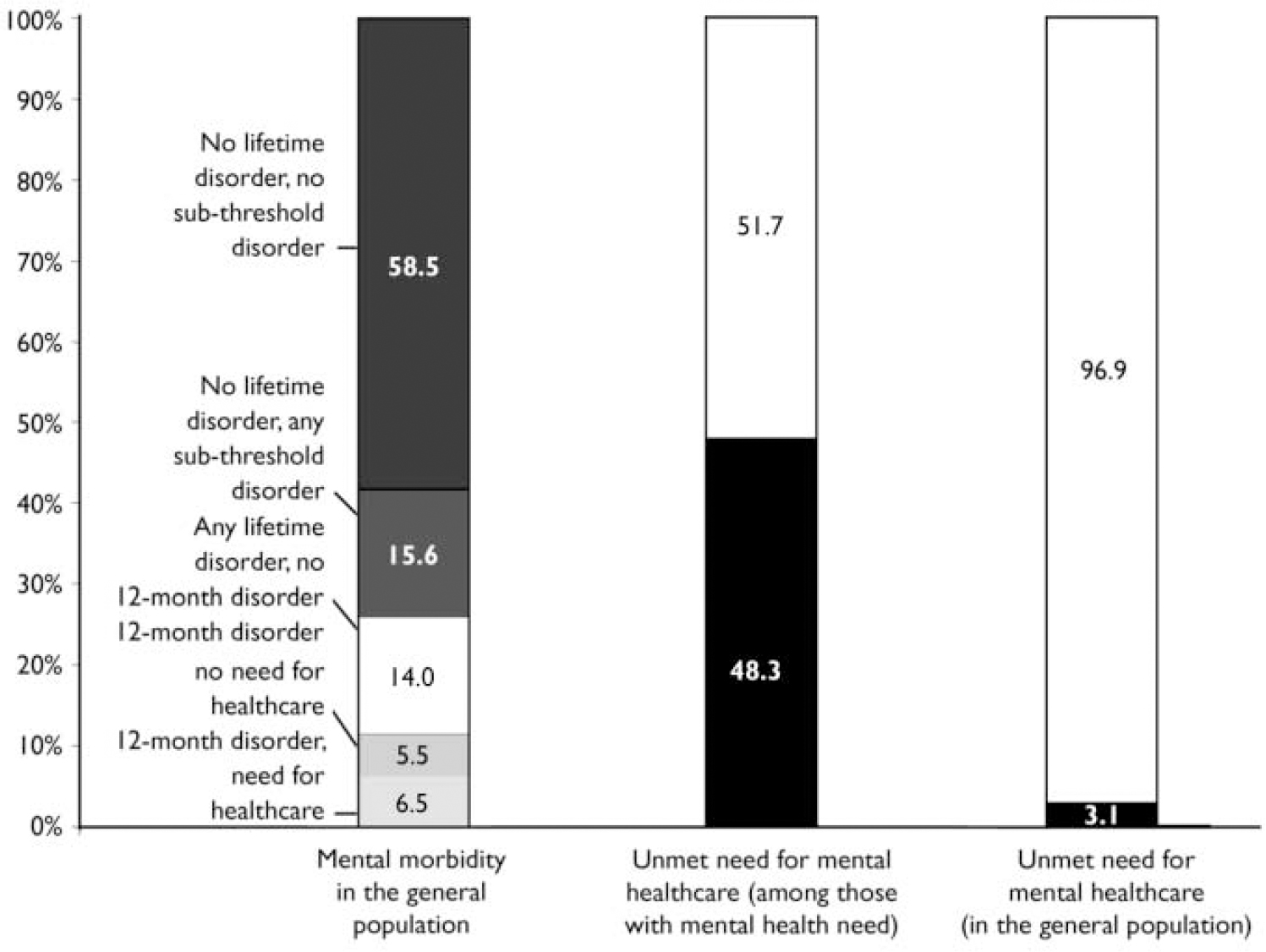

As shown in Table 1, 51.8% of the sample were women; the mean age of the sample was 47 years, 34.6% had over 12 years of education, and two-thirds of the sample were married or living with someone. A total of 11.9% of the sample (95% CI 11.1–12.9) had a 12-month mental disorder and 6.5% (95% CI 5.9–7.0) were defined as having a need for mental healthcare (i.e. a 12-month disorder that was disabling or had led to health services use in the year prior to the interview). Additionally, 14.0% had a lifetime mental disorder, but not in the previous 12 months, and 15.6% had sub-threshold mental morbidity.

Table 1 Characteristics of the study sample at phase 2: raw numbers, weighted proportions and 95% confidence intervals (n=8796)

| Total (n=8796) | % | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age categories, years1 | |||

| 18-24 | 664 | 11.4 | 10.3-12.7 |

| 25-34 | 1599 | 18.3 | 17.1-19.6 |

| 35-49 | 2669 | 27.8 | 26.4-29.2 |

| 50-64 | 2197 | 21.8 | 20.5-23.1 |

| 65+ | 1667 | 20.7 | 19.3-22.1 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 3689 | 48.2 | 46.6-49.9 |

| Female | 5107 | 51.8 | 50.1-53.4 |

| Education categories | |||

| 0-12 years of education | 5515 | 65.4 | 63.8-66.9 |

| >13 years of education | 3281 | 34.6 | 33.1-36.2 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married or living with someone | 5788 | 66.8 | 65.2-68.3 |

| Previously married | 1327 | 11.1 | 10.2-12.2 |

| Never married | 1681 | 22.1 | 20.7-23.6 |

| Urbanicity2 | |||

| Large urban | 2431 | 28.1 | 26.6-29.6 |

| Mid-size urban | 3840 | 38.7 | 37.1-40.4 |

| Rural | 2525 | 33.2 | 31.5-34.9 |

| Employment | |||

| Paid employment | 4863 | 56.5 | 54.9-58.1 |

| Student | 172 | 2.8 | 2.3-3.3 |

| Homemaker | 986 | 9.1 | 8.3-10.0 |

| Retired | 1881 | 23.5 | 22.1-25.0 |

| Unemployed | 520 | 6.3 | 5.5-7.2 |

| Other | 374 | 1.8 | 1.5-2.1 |

| Income quintiles | |||

| 0-20% | 1668 | 19.8 | 18.5-21.2 |

| 20-40% | 1682 | 19.9 | 18.6-21.3 |

| 40-60% | 1700 | 19.7 | 18.4-21.1 |

| 60-80% | 1797 | 20.4 | 19.1-21.7 |

| 80-100% | 1949 | 20.2 | 18.9-21.5 |

| Country | |||

| Belgium | 1043 | 3.8 | 3.3-4.3 |

| France | 1436 | 20.5 | 19.5-21.6 |

| Germany | 1323 | 31.5 | 30.3-32.7 |

| Italy | 1779 | 22.4 | 21.1-23.8 |

| Netherlands | 1094 | 6.1 | 5.7-6.6 |

| Spain | 2121 | 15.6 | 14.8-16.5 |

| Mental health status | |||

| No disorder | 3315 | 58.5 | 56.9-60.1 |

| Lifetime sub-threshold, no lifetime disorder | 1334 | 15.6 | 14.4-16.8 |

| Lifetime disorder, no 12-month disorder | 2296 | 14.0 | 13.1-14.9 |

| Any 12-month disorder | 1851 | 11.9 | 11.1-12.9 |

| 12-month mental disorder | |||

| Need for mental healthcare | 1279 | 6.5 | 5.9-7.0 |

| No need for mental healthcare | 572 | 5.5 | 4.8-6.3 |

Table 2 shows that individuals defined as having a need for mental healthcare had lower mean scores on the mental component of the SF–12 than all other morbidities groups, including those with a 12-month disorder but with no need (i.e. with a non-disabling disorder) for mental healthcare (41.2 v. 45.8, respectively; P<0.01). Similar differences were found on the work loss days index (mean score of 23.4 v. 17.2 respectively; P<0.01).

Table 2 Physical and mental component summary scores of the 12-item Short Form Health Survey and work loss days index according to category of mental disorder (n=8796).

| PCS—12 | MCS—12 | Work loss days | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental morbidity group | Mean | (95% CI) | Mean | (95% CI) | Mean | (95% CI) |

| No lifetime disorder, no sub-threshold disorder | 50.7 | (50.4-51.0) | 51.5 | (51.2-51.8) | 6.4 | (5.2-7.7) |

| No lifetime disorder, any sub-threshold disorder | 49.6 | (49.0-50.3) | 49.5 | (48.9-50.1) | 9.6 | (7.2-12.1) |

| Any lifetime disorder, no 12-month disorder | 49.3 | (48.9-49.8) | 48.7 | (48.2-49.1) | 9.6 | (7.0-12.2) |

| 12-month disorder, no need for mental healthcare | 49.9 | (47.9-50.4) | 45.8 | (44.7-47.0) | 17.2 | (10.2-24.2) |

| 12-month disorder, need for mental healthcare | 46.3 | (45.5-47.1) | 41.2 | (40.3-42.2) | 23.4 | (20.3-26.6) |

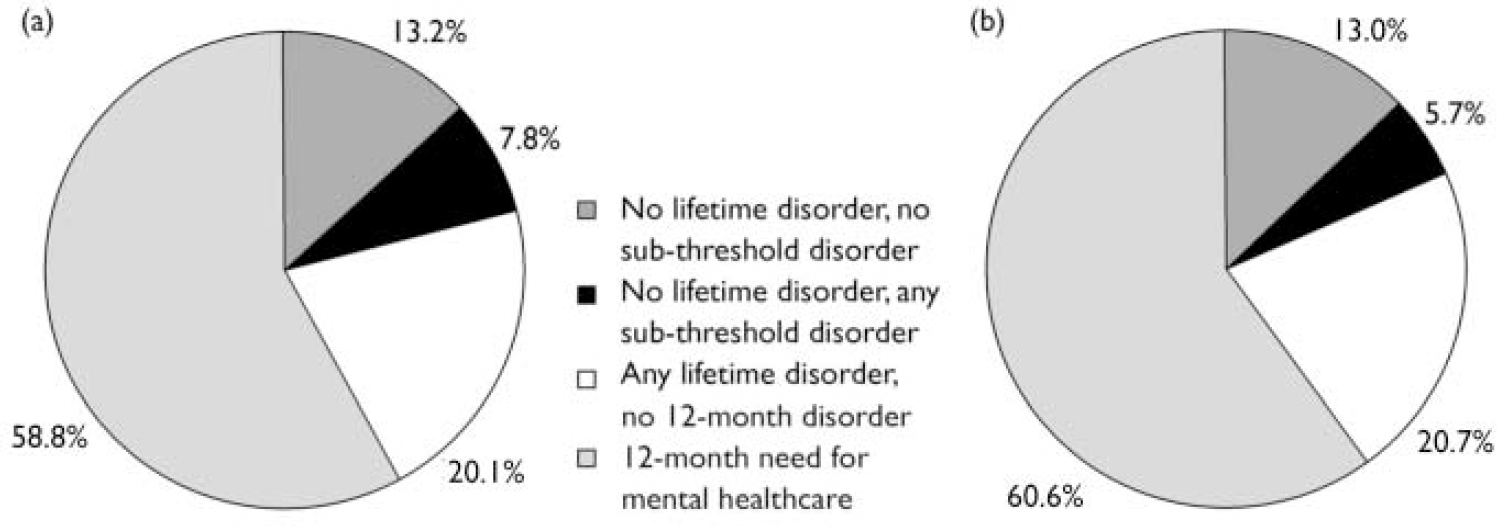

Among those defined as having a need for mental healthcare, 51.7% (95% CI 47.5–55.9) reported using any type of formal healthcare and 25.1% (95% CI 21.9–28.4) reported seeing a mental health specialist in the 12 months prior to the interview (Table 3). By combining the prevalence of need for mental health services and the proportion of those with a need for care who did not receive any formal healthcare, we estimated that 3.1% (95% CI 2.7–3.6) of the adult population had an unmet need for mental healthcare in the overall sample (Fig. 1). Across participating countries, the raw level of unmet need varied between 1.6% (95% CI 1.2–2.2) in Italy and 5.8% (95% CI 4.3–7.6) in The Netherlands.

Fig. 1 Prevalence of 12-month need for mental healthcare and unmet need in the European population.

Table 3 Use of any formal health services and mental health specialists in the previous 12 months, according to category of mental disorder

| Visits to formal health services | Visits to a mental health specialist | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of visits3 | Number of visits3 | ||||||||

| n 1 | Percentage use2 (95% CI) | Total sample Mean (95% CI) | Those who visited Mean (95% CI) | Total visits4 (95% CI) | Percentage use2 (95% CI) | Total sample Mean (95% CI) | Those who visited Mean (95% CI) | Total visits4 (95% CI) | |

| Total sample | 8796 | 7.4 (6.8-8.1) | 0.67 (0.56-0.77) | 9.00 (7.75-10.25) | 5863 (4938-6788) | 3.7 (3.2-4.2) | 0.46 (0.36-0.56) | 12.41 (10.11-14.72) | 4042 (3192-4893) |

| No lifetime disorder, no sub-threshold disorder | 33 319 | 2.7 (2.1-3.6) | 0.15 (0.06-0.24) | 5.53 (2.44-8.60) | 776 (308-1244) | 1.4 (0.9-2.1) | 0.10 (0.01-0.19) | 7.40 (1.43-13.37) | 526 (73-980) |

| No lifetime disorder, any subthreshold disorder | 1340 | 5.3 (3.8-7.3) | 0.34 (0.17-0.51) | 6.32 (4.02-8.62) | 460 (224-696) | 2.4 (1.6-3.6) | 0.17 (0.06-0.27) | 6.97 (3.15-10.79) | 230 (88-373) |

| Any lifetime disorder no 12-month disorder | 2342 | 11.8 (10.0-13.8) | 0.96 (0.66-1.26) | 8.17 (6.14-10.20) | 1180 (810-1550) | 6.4 (5.1-8.1) | 0.68 (0.41-0.95) | 10.57 (7.32-13.81) | 836 (499-1173) |

| Any 12-month disorder | 1795 | 28.0 (25.1-31.0) | 3.28 (2.63-3.93) | 11.74 (9.80-13.67) | 3447 (2772-4121) | 13.5 (11.7-15.6) | 2.33 (1.73-2.93) | 17.21 (13.81-20.61) | 2449 (1826-3073) |

| 12-month need for mental healthcare | 1524 | 51.7 (47.5-55.9) | 6.07 (4.94-7.19) | 11.74 (9.80-13.67) | 3447 (2772-4121) | 25.1 (21.9-28.4) | 4.31 (3.24-5.38) | 17.21 (13.81-20.61) | 2449 (1826-3073) |

A total of 3447 visits to formal healthcare services were reported by those with any 12-month disorder (an average of just under 12 visits per individual), compared with 2449 visits to a specialist (approximately 17 visits per individual). More than half of all visits reported were made by individuals with a 12-month mental health need, and only 13.2% (any formal health services) and 12.9% (mental specialist) were made by individuals with no reported mental morbidity (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2 Visits to (a) any formal health services (5863 visits) and (b) mental health specialists (4042 visits) in the previous 12 months categorised by type of mental disorder.

Among those individuals interviewed about the presence of chronic physical conditions, arthritis or rheumatism in the previous 12 months was reported by 11.8% (95% CI 10.8–12.8), high blood pressure was reported by 13% (95% CI 11.9–14.2) and diabetes by 4.1% (95% CI 3.4–4.8). Of these, 66.7% (arthritis or rheumatism), 88.4% (high blood pressure) and 91.9% (diabetes) reported using healthcare services because of their condition in the 12 months prior to the interview.

The first column of Table 4 shows the adjusted odds ratios of unmet need for mental healthcare (i.e. the absence of use of any formal health service among those with a need for care in the previous 12 months). Compared with the youngest age groups (18–24 years), all age groups had a substantially lower risk for unmet need (0.2 for those aged 50–64 years and those 65+, 0.3 for those aged 35–49 years and 0.5 for those aged 25–34 years; statistically significant differences). Homemakers and retired individuals had a substantial and statistically significant risk of unmet need (odds ratios 2.4 and 3.4 respectively) in comparison with those in paid employment (the reference category). Individuals whose onset of their mental disorder took place more than 15 years previously had more than twice the likelihood of unmet need for mental care. Some international variation in the level of unmet need was observed, with a higher level of unmet need in The Netherlands and a lower level of unmet need in Spain in comparison with the mean of the six countries considered. The only statistically significant interactions were found between living in Belgium and having a chronic condition, showing a protective effect on the likelihood of having unmet need for mental healthcare.

Table 4 Factors associated with the lack of use of formal health services (unmet need) and lack of use of mental health specialised care among those with a 12-month mental health need (n=8,796).

| Odds ratios (95% CI)1 | ||

|---|---|---|

| No use of formal health services (n=1212) | No use of specialised care (n=1215) | |

| Age categories, years | ||

| 18-24 | Reference | |

| 25-34 | 0.5 (0.2-0.9) | 0.4 (0.2-1.0) |

| 35-49 | 0.3 (0.1-0.6) | 0.4 (0.2-1.0) |

| 50-64 | 0.2 (0.1-0.4) | 0.3 (0.1-0.9) |

| +65 | 0.2 (0.1-0.7) | 0.8 (0.2-3.3) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | Reference | |

| Female | 0.7 (0.5-1.0) | 0.8 (0.3-1.3) |

| Education categories | ||

| 0-12 years of education | Reference | |

| > 13 years of education | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married or living with someone | Reference | |

| Previously married | 0.9 (0.5-1.5) | 0.8 (0.5-1.3) |

| Never married | 1.2 (0.7-2.0) | 0.8 (0.4-1.4) |

| Urbanicity | ||

| Large urban | Reference | |

| Rural | 0.7 (0.4-1.1) | 1.1 (0.7-1.8) |

| Mid-size urban | 1.0 (0.7-1.5) | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) |

| Employment | ||

| Paid employment | Reference | |

| Student | 0.4 (0.1-1.5) | 0.7 (0.2-2.4) |

| Homemaker | 2.4 (1.4-4.3) | 1.2 (0.6-2.3) |

| Retired | 3.4 (1.7-6.9) | 1.8 (0.8-4.1) |

| Unemployed | 0.9 (0.5-1.9) | 0.6 (0.3-1.3) |

| Other | 0.5 (0.3-1.0) | 0.4 (0.2-0.7) |

| Income Quintiles | ||

| 0-20% | Reference | |

| 20-40% | 1.3 (0.7-2.2) | 1.0 (0.6-1.8) |

| 40-60% | 1.7 (1.0-2.8) | 1.4 (0.8-2.4) |

| 60-80% | 1.0 (0.6-1.8) | 1.1 (0.6-2.0) |

| 80-100% | 1.6 (0.9-2.8) | 1.1 (0.6-2.0) |

| Country2 | ||

| Belgium | 0.8 (0.5-1.2) | 0.9 (0.5-1.4) |

| France | 1.2 (0.9-1.7) | 1.3 (0.9-1.9) |

| Germany | 1.1 (0.8-1.5) | 0.9 (0.6-1.3) |

| Italy | 0.8 (0.6-1.1) | 1.3 (0.9-2.0) |

| Netherlands | 1.9 (1.3-2.8) | 1.4 (0.9-2.1) |

| Spain | 0.7 (0.5-0.9) | 0.5 (0.4-0.7) |

| Chronic disease | ||

| No | Reference | |

| Yes | 1.3 (0.9-1.9) | 1.3 (0.9-2.0) |

| Years since disorder onset | ||

| 0-4 years | Reference | |

| 5-15 years since onset | 1.5 (0.8-2.7) | 0.8 (0.5-1.4) |

| 15 years since onset | 2.3 (1.3-4.0) | 1.4 (0.8-2.5) |

| Model calibration | ||

| Hosmer-Lemeshow Wald P value | P=0.1561 | P=0.1902 |

Column 2 of Table 4 shows a similar multivariate logistic regression model, with the dependent variable being the lack of use of a mental specialist among those with a need for mental healthcare. Results were similar in overall trends but some of the previous differences were no longer statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional study in six European countries, we estimated that 3.1% of the adult populations had an unmet need for mental healthcare. That would represent about 6.6 million adults from a total population of 213 million in those countries. This is a fairly high level of unmet need, especially given that need for care was calculated using only a limited number of common mental disorders and the criterion for defining a need as being met was quite conservative. Several groups had a higher risk of unmet need for mental healthcare, particularly the youngest, retired people and homemakers, and those with a mental disorder that had started a long time before. There was also international variation in the level of unmet need, with living in The Netherlands being associated with a higher risk of not using services when there was a need for healthcare and living in Spain being associated with a lower risk of not using services when there was a need for healthcare. Women presented a trend towards a lower level of unmet need but the trend was not statistically significant. Although women use services more often than men (Reference Young, Klap and SherbourneYoung et al, 2001), it might well be that the relative excess use is predominantly due to disorders that do not comply with our criteria of need for care.

Estimating need for mental healthcare

The level of unmet need for mental healthcare that we have estimated for the European general adult population is lower than previously reported values (Reference Regier, Narrow and RaeRegier et al, 1993; Reference Lin, Goering and OffordLin et al, 1996; Reference Bijl and RavelliBijl & Ravelli, 2000; Reference Andrews, Henderson and HallAndrews et al, 2001a ; Reference McConnell, Bebbington and McClellandMcConnell et al, 2002; Reference Kessler, Demler and FrankKessler et al, 2005). This was expected, given the more stringent definition of need used in our study, which required the presence of considerable level of disability and/or the use of services because of a mental disorder. Although there is no consensus about how to measure psychiatric disability (Work Group on Major Depressive Disorder, 2000), our approach seems conceptually and empirically justified, in that considerable interference with life and activities should be considered a relevant criterion for the use of healthcare among those with a mental disorder (Reference Mojtabai, Olfson and MechanicMojtabai et al, 2002; Reference MechanicMechanic, 2003). In our study, contacting the health services in regard to a mental health problem was also considered to be an indicator of the clinical relevance of a mental health disorder (Reference Narrow, Rae and RobinsNarrow et al, 2002). Including individuals who had already used services in relation to their disorder in the definition of need for care may imply some risk of circularity, but these individuals tend to have more severe illness. Clearly their disorder might have become less disabling owing to the treatment received. Therefore, by definition, individuals with a 12-month disorder who had their need for care met could not be ignored in the estimation of need.

Increase service provision

In this study, individuals defined as having a need for mental healthcare had substantial and statistically significant higher levels of disability and lower quality of life than individuals with a non-disabling 12-month mental disorder. These differences were even more noticeable in comparison with the first group of individuals with no morbidity or sub-threshold morbidity. These findings suggest that the measure of mental morbidity and its impact used in this study was valid as well as being feasible for use in a large population sample. This approach could potentially also be used to monitor the evolution of access to mental health services. A noteworthy finding of this study is that the utilisation of healthcare is much higher for chronic physical conditions such as arthritis or rheumatism and diabetes than for mental disorders. Such differences also suggest underuse of care among those with mental disorders, in comparison with physical conditions, perhaps owing to a lack of perception of need for care by those with mental disorders (Reference Mojtabai, Olfson and MechanicMojtabai et al, 2002).

A strength of our study is that we considered other levels of mental morbidity in our analysis of the utilisation of health services (i.e. people with lifetime disorders or with sub-threshold mental morbidity). Sub-threshold depression, for instance, has been shown to be associated with an elevated risk of subsequent depression and suicidal behaviours (Reference Andrews, Issakidis and CarterAndrews et al, 2001b ). Taking into account additional mental health morbidity allowed us to refine the evaluation of the current use of health services for mental health reasons. In particular, we identified that only a minority (about 13%) of the visits made for mental health reasons to any formal healthcare provider were made by individuals with no mental morbidity. This suggests that even if we were able to diminish or even eliminate the probably unnecessary visits made by individuals with no mental morbidity, it would be impossible to accommodate the visits for those with unmet need for care. This is in contrast to what we had previously suggested, that reallocating current services used for psychiatric disorders might contribute substantially to diminishing the proportion of unmet need for mental healthcare (Reference Demyttenaere, Bruffaerts and Posada-VillaDemyttenaere et al, 2004). It is more likely that the necessary increase in use of health services for those in need of care should be obtained at the expense of more services. The participation of primary care services in general and of specialised nursing staff and/or social workers might be a viable alternative (Reference Clarkson, McCrone and SutherbyClarkson et al, 1999).

Limitations

Some limitations of this study deserve mention. First, the response rate in some countries was low. The prevalence of mental disorders among non-responders may be higher than among responders (Reference Graaf, de Bijl and SmitGraaf et al, 2000), which might have led us to underestimate the real level of need for care. Additionally, non-responders may use healthcare services differently from responders. This could be particularly important in the case of France and Belgium, which had the lowest participation rates. Similarly to other surveys, we used self-reports to assess need for care. Although comparability of data generated by health interviews is assured, the results might not be consistent with other sources of information. In addition, self-reports may underestimate health service use (Reference Ritter, Stewart and KaymazRitter et al, 2001) and thus we might have overestimated unmet need for care. Previous work suggests that the underreporting of use of healthcare services tends to be lower or even non-existent among those with current disorders or those with more severe psychiatric disorders (Reference Rhodes, Lin and MustardRhodes et al, 2002). On the other hand, it is more likely that we have underestimated unmet need, for at least two reasons. First, we used a very low threshold for categorising met need: just one visit to any formal services or to a mental health specialist. Evidence-based recommendations of effective treatment for several disorders including major depression (Work Group on major Depressive Disorder, 2000), panic disorder and agoraphobia (Reference Lin, Goering and OffordLin et al, 1996) require a series of clinical visits and specific drug treatment, well beyond the minimal approach considered in our study. This may be a particular concern with visits to primary care providers because the reason for the visit may be less clear. Second, we note that among our respondents with a 12-month disorder who used health services, more than a fifth (21.2%) had not been prescribed any active treatment (Reference Alonso, Angermeyer and BernertAlonso et al, 2004b ). Finally, we deliberately did not consider the adequacy of the treatment received, which deserves specific, deeper analyses.

Implications

The size of the treatment gap described here implies that many actions should be taken to control mental disorders at the population level. In addition to an increase in service provision, an increase in the access, use, effectiveness and efficiency of existing services is necessary. This might be achieved through improvements in the distribution of work between primary care and specialist services, more use of shared care between primary and secondary care, more use of best-practice tools and methods (such as clinical guidelines and computer-assisted techniques) and continuing professional development. In addition, other societal and attitudinal variables influence the rates of unmet need (Reference Andrews, Issakidis and CarterAndrews et al, 2001b ). Educating individuals in need for mental healthcare may be as important as expanding the services. According to our results, the youngest patients, homemakers and retired people, as well as those with a longer evolution of their disorder, need to be more specifically targeted in these efforts. There is also a need for more qualitative research to aid us in understanding why people underuse mental healthcare services.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the European Commission (Contract QLG5-1999-01042, SANCO 2004123), the Piedmont Region (Italy), Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain (FIS 00/0028), Ministerio de Ciencia y Tecnología, Spain (SAF 2000-158-CE), Departament de Salut, Generalitat de Catalunya, Spain, and other local agencies and by an unrestricted educational grant from GlaxoSmithKline. The European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) is carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. We thank the latter's staff for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork and data analysis. The ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 investigators are: Jordi Alonso, Matthias Angermeyer, Sebastian Bernert, Ronny Bruffaerts, Traolach S. Brugha, Giovanni de Girolamo, Ron de Graaf, Koen Demyttenaere, Isabelle Gasquet; Josep Maria Haro, Steven J. Katz; Ronald C. Kessler, Viviane Kovess, Jean Pierre Lépine, Johan Ormel, Gabriella Polidori and Gemma Vilagut.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.