According to the early-onset hypothesis of antipsychotic drug action, Reference Agid, Kapur, Arenovich and Zipursky1 absence of an early response to medication is a stable predictor of subsequent lack of response in patients with schizophrenia. Reference Correll, Malhotra, Kaushik, McMeniman and Kane2–Reference Lin, Chou, Lin, Hsu, Chen and Lane4 Despite the importance of identifying early improvement with treatment in first-episode schizophrenia, Reference Kasper5 to our knowledge only a limited number of trials have investigated this topic. Emsley et al found response at week 6 to be one of the most stable predictors of remission after 2 years and 4 years. Reference Emsley, Oosthuizen, Kidd, Koen, Niehaus and Turner6,Reference Emsley, Rabinowitz and Medori7 Crespo-Facorro et al analysed acute treatment response in 172 patients and concluded that the identification of non-responders is the first step towards optimising therapeutic efforts. Reference Crespo-Facorro, Pelayo-Teran, Perez-Iglesias, Ramírez-Bonilla, Martínez-García and Pardo-García8 However, to date no systematic analysis finding the best definition of early response and concurrently evaluating its predictive validity for subsequent outcome has been carried out. In addition, although first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics have demonstrated a similar likelihood of achieving a favourable response in patients with first-episode schizophrenia, Reference Schooler, Rabinowitz, Davidson, Emsley, Harvey and Kopala9 data on early response have yet to be reported. Therefore, to expand prior research, we developed a valid definition of early treatment improvement that best predicts treatment response and remission. Additionally, early improvement was compared between risperidone and haloperidol treatment.

Method

Sample

The patient sample was drawn from a multicentre follow-up programme performed within the German Research Network on Schizophrenia. Reference Gaebel, Riesbeck, Wolwer, Klimke, Eickhoff and von Wilmsdorff10,Reference Möller, Riedel, Jäger, Wickelmaier, Maier and Kühn11 The entire study programme consisted of an 8-week acute study and a subsequent 2-year long-term treatment phase. The programme was conducted at 13 German university psychiatric hospitals according to the principles of good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. The study reported here covers the 8-week acute treatment phase.

Participants were selected from all individuals admitted to the in-patient departments between November 2000 and May 2004. Inclusion criteria were acute manifestation of a first episode of schizophrenia according to ICD–10 F20 criteria; age 18–65 years; adequate proficiency in the German language; no involuntary in-patient treatment up to the date of inclusion; and provision of written informed consent. Reference Gaebel, Riesbeck, Wolwer, Klimke, Eickhoff and von Wilmsdorff10 Exclusion criteria were pregnancy; unchanged psychopathological condition or worsening of symptoms during pre-treatment with risperidone and haloperidol; other contraindications for risperidone or haloperidol; intellectual disability; organic brain disease; substance misuse; history of suicidal behaviour; severe physical disease; or participation in other trials. Approval was obtained from the coordinating centre as well as the local centres.

Treatment

Patients who had already been treated with psychotropic drugs underwent a 4–7 day wash-out period. After random assignment to treatment groups in a 1: 1 ratio, patients received 2 mg of the study medication once daily. Investigators, staff and patients were masked to treatment assignment. The dose could be increased by 1–2 mg per day between day 3 and day 7 if required, and then at each weekly assessment up to a maximum of 8 mg per day, but the total dose was not to exceed 4 mg per day by week 2. Psychotropic substances were not allowed as concomitant medication, with the exception of short-acting benzodiazepines for insomnia and lorazepam to arrest agitation and psychotic anxiety. The anticholinergic drug biperiden (up to 6 mg per day) could be prescribed for extrapyramidal symptoms and the beta-blocker propranolol (up to 80 mg per day) could be prescribed for akathisia.

Assessments

The diagnoses were established by clinical researchers on the basis of the German version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV. 12 During interviews with patients, relatives and care providers, a standardised documentation system was used to collect sociodemographic and course-related variables such as age at onset or duration of untreated psychosis. Reference Cording13 To assess symptom severity, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia was used. Reference Kay, Opler and Lindenmayer14 Adverse events were assessed using the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS). Reference Guy15 The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) were applied to measure the patients' psychological, social and occupational functioning. 12,16 Ratings were performed within 3 days of admission to hospital, and weekly during in-patient treatment until treatment week 8. Interrater reliability yielded a satisfactory to good concordance which fitted to values of other publications, for example the intraclass correlation coefficient of the PANSS positive scale was 0.74 (P<0.001).

Statistical analysis

Early improvement was defined as a percentage of any improvement in PANSS total score from baseline to week 2. Response was defined in accordance with Kinon et al as a minimum 40% reduction in PANSS total score from admission to week 8. Reference Kinon, Chen, Scher-Svanum, Stauffer, Kollack-Walker and Sniadecki17 For all calculations of percentage change the minimum of the PANSS total score was subtracted. Reference Obermeier, Mayr, Schennach-Wolff, Seemüller, Möller and Riedel18 Remission was defined according to the criteria recently proposed by the Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group as a PANSS rating of 3 or less on the following items: delusions (P1), unusual thought contents (G9), hallucinatory behaviour (P3), conceptual disorganisation (P2), mannerism/posturing (G5), blunted affect (N1), social withdrawal (N4) and lack of spontaneity (N6). Reference Andreasen, Carpenter, Kane, Lasser, Marder and Weinberger19 Thetimecriterion of theapplied consensus remission criteria could not be considered owing to the designated study duration of 8 weeks. Group differences regarding the outcome criteria were tested using Fisher's exact test for count data; the Wilcoxon rank sum test was applied for continuous data.

The discriminative and predictive ability of early improvement was evaluated using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. This curve combines the information of the true positive rate and the true negative rate. The area under the curve (AUC) is a measure of the overall discriminative power. A value of 0.5 for the AUC does not represent discriminative ability, whereas a value of 1.0 indicates perfect power. Reference Weinstein and Fineberg20 The optimal cut-off point is detected by maximising the sum of the true positive and true negative rates. To analyse AUC group differences a permutation test was applied. Permutation tests can be used in order to test the difference in the AUC values of a single metric variable in independent sample groups; the main advantage of this procedure is that no assumption about the distribution of the test statistics is needed.

In order to identify the most useful criterion of early improvement, total accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values were calculated for all possible early improvement cut-offs of a percentage PANSS total score improvement (1%, 2%… 98%, 99%). The total accuracy shows the proportion of patients whose psychopathological status at week 2 (early improvement or no early improvement) predicted subsequent response and remission at week 8. Reference Fawcett21 Sensitivity is defined as the correct identification of patients subsequently achieving response or remission, and specificity as the correct identification of patients subsequently not achieving response or remission. The positive predictive value is the probability that a patient with early improvement will show subsequent response and remission, and the negative predictive value reflects the probability that a patient without early improvement will show subsequent non-response and non-remission.

When estimating a confidence interval for the optimum cut-off, the optimal cut-off point is detected by maximising the sum of sensitivity and specificity. To compute a confidence interval around this parameter, an assumption regarding the distribution of the latter is needed. To avoid this, the distribution can be simulated based on the data from the sample. This is commonly known as the classical non-parametric bootstrap procedure. All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical program R version 2.6.1 for Windows. 22

Results

The patient sample available comprised 289 patients (for details see Möller et al). Reference Möller, Riedel, Jäger, Wickelmaier, Maier and Kühn11 For the analysis reported here, 101 patients had to be excluded: 56 patients (19%) discontinued the study within the first 3 weeks of treatment and for 45 patients (16%) single items were missing in the requested PANSS data. Patients excluded and patients continuing the study were compared regarding sociodemographic, psychopathological and further clinical variables (Table 1). In total, 188 patients – 111 men (59%) and 77 women (41%) – were examined in this analysis; 93 patients were treated with risperidone and 95 with haloperidol. The applied mean dosages of risperidone and haloperidol are shown in Table 2. The mean age was 31.16 years (s.d. = 9.09).

Table 1 Comparison of patients excluded from analysis and those remaining in study

| Patients excluded (n = 56) | Patients included (n = 188) | P (adjusted) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 27.18 (8.98) | 31.16 (10.00) | 0.0034 (0.0548) |

| PANSS score: mean (s.d.) | |||

| Positive scale | 21.98 (7.89) | 21.17 (5.89) | 0.5384 (0.1000) |

| Negative scale | 21.53 (9.04) | 18.53 (8.05) | 0.0352 (0.2469) |

| Global | 41.75 (15.06) | 37.44 (12.29) | 0.0593 (0.2469) |

| Total | 85.25 (28.76) | 77.14 (23.00) | 0.0617 (0.2469) |

| Insight into illness (G12): mean (s.d.) | 3.35 (1.78) | 3.24 (1.64) | 0.7833 (0.1000) |

| GAF score: mean (s.d.) | 47.30 (13.11) | 44.27 (13.81) | 0.1007 (0.3221) |

| SOFAS score: mean (s.d.) | 47.20 (12.68) | 45.69 (13.17) | 0.3599 (0.8226) |

| DUP, months: mean (s.d.) | 3.08 (2.26) | 2.94 (2.13) | 0.7556 (0.1000) |

| Female, n | 23 | 77 | 0.1000 (0.1000) |

| Medication with haloperidol, n | 29 | 95 | 0.8803 (1.0000) |

| Pre-treatment, n | 18 | 56 | 0.7426 (1.0000) |

| AIMS score >0 in week 1, n | 1 | 15 | 0.1288 (0.2577) |

Table 2 Risperidone and haloperidol dosage applied during the course of the study

| Dosage, mg: mean (s.d.) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Haloperidol | Risperidone | P a | |

| Week 1 | 2.6 (1.0) | 2.6 (1.0) | 2.7 (1.0) | 0.524 |

| Week 2 | 3.6 (1.3) | 3.5 (1.3) | 3.7 (1.3) | 0.203 |

| Week 3 | 4.2 (1.6) | 4.1 (1.5) | 4.3 (1.6) | 0.365 |

| Week 4 | 4.5 (1.8) | 4.5 (1.8) | 4.5 (1.9) | 0.847 |

| Week 5 | 4.6 (2.0) | 4.6 (2.0) | 4.6 (2.0) | 0.934 |

| Week 6 | 4.7 (2.1) | 4.6 (2.1) | 4.8 (2.2) | 0.523 |

| Week 7 | 4.5 (2.2) | 4.3 (2.0) | 4.7 (2.4) | 0.256 |

| Week 8 | 4.4 (2.2) | 4.0 (2.0) | 4.6 (2.4) | 0.151 |

Treatment response and remission

According to the applied response criteria, 119 patients (63%) were classified as treatment responders at week 8 and 116 patients (62%) fulfilled remission criteria. Half the patients (n = 94) achieved response as well as remission, 25 patients responded but were not concurrently in remission and 22 patients achieved remission without concurrently being responders.

Divided into the two treatment groups, 59 haloperidol-treated patients (62%) achieved response and 56 (59%) achieved remission, with 46 patients being responders and remitters concurrently. In the risperidone group, 60 patients (64%) fulfilled response criteria and 60 patients (64%) fulfilled remission criteria, with 48 patients achieving response and remission concurrently. When the two patient subgroups were compared regarding differences in response and remission rates, no significant difference could be observed (for response P = 0.76, for remission P = 0.46). Additionally, when patients with an increase of dosage in the first two treatment weeks (n = 138) were compared regarding the achievement of response and remission, no significant association was found (for response P = 0.22, for remission P = 1.00).

Improvement in PANSS total score at week 2

The allocation of improvement depends on the definition applied, i.e. the required percentage reduction in PANSS total score after 2 weeks of treatment. For total sample and treatment subgroups see Table 3. No significant difference in the improvement in PANSS total score at week 2 could be detected between the risperidone and haloperidol treatment subgroups.

Table 3 Improvement in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score at week 2

| PANSS total score improvement | Total sample n (%) | Haloperidol group n (%) | Risperidone group n (%) | Odds ratio | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | 155 (82) | 77 (81) | 78 (84) | 0.82 | 0.7025 |

| 20% | 136 (72) | 68 (72) | 68 (73) | 0.93 | 0.8711 |

| 30% | 114 (61) | 57 (60) | 57 (61) | 0.95 | 0.8822 |

| 40% | 89 (47) | 47 (49) | 42 (45) | 1.19 | 0.5629 |

| 50% | 66 (35) | 33 (35) | 33 (36) | 0.97 | 1.0000 |

| 60% | 53 (28) | 27 (29) | 26 (27) | 1.09 | 0.8716 |

| 70% | 31 (16) | 17 (18) | 14 (15) | 1.12 | 0.5593 |

| 80% | 12 (6) | 6 (6) | 6 (6) | 1.02 | 1.0000 |

| 90% | 4 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (3) | 0.34 | 0.6210 |

| 100% | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0.00 | 0.4974 |

Validity of improvement at week 2 as predictor of response and remission

Response. To examine the ability of the psychopathological improvement at week 2 to predict response at week 8, a ROC curve was generated for the total patient sample (AUC = 0.707) and both treatment subgroups (haloperidol AUC = 0.677, risperidone AUC = 0.737) for the reduction in PANSS total score after the first two treatment weeks (Fig. 1). When comparing the validity of early improvement as a predictor of response between the two treatment groups, no significant difference could be observed (P = 0.43).

Fig. 1 Receiver operating characteristic curve for early improvement as predictor of response at discharge. AUC, area under the curve.

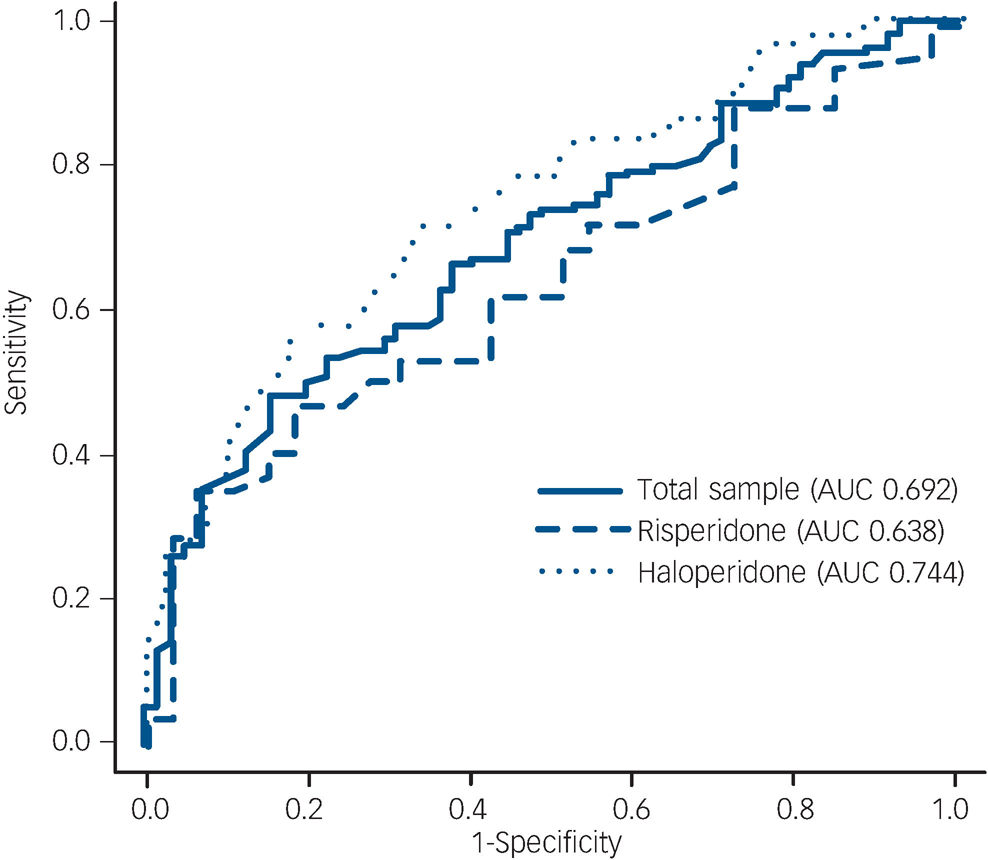

Remission. To examine the ability of improvement at week 2 to predict remission at week 8, a ROC curve was generated for the total patient sample (AUC = 0.692) and patient subgroups (haloperidol AUC = 0.744, risperidone AUC = 0.638) for the reduction in PANSS total score after the first two treatment weeks (Fig. 2). When the validity of early improvement as a predictor of remission was compared between the two treatment groups, no significant difference could be observed (P = 0.16).

Fig. 2 Receiver operation characteristic curve for early improvement as predictor of remission at discharge. AUC, area under the curve.

Optimum cut-off points of early improvement as predictor

Response. Total accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of different cut-off points (percentage improvement in PANSS total score) for predicting response at week 8 are shown in online Table DS1. A cut-off point of 46% showed the highest score for sensitivity (55%) and specificity (80%); the positive predictive value was 82% and the negative predictive value 50%.

Remission. Total accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of different cut-off points for predicting remission at week 8 are shown in online Table DS2. A cut-off point of 50% showed the highest score for sensitivity (47%) and specificity (85%); the positive predictive value was 83% and the negative predictive value 50%.

Optimum cut-off estimated by a confidence interval using bootstrap

Response. The bootstrap procedure led to a cut-off confidence interval of 26–60% (0.258–0.606).

Remission. The bootstrap procedure led to a cut-off confidence interval of 28–62% (0.276–0.615).

As the 95% confidence intervals for the optimal cut-offs in both treatment groups heavily overlap and include the optimal cut-offs, one can assume that those cut-off points and therefore their intervals do not significantly differ, with P>0.05 between risperidone and haloperidol. Reference Cumming23

Comparison of patients achieving or not achieving the proposed 30% improvement at week 2

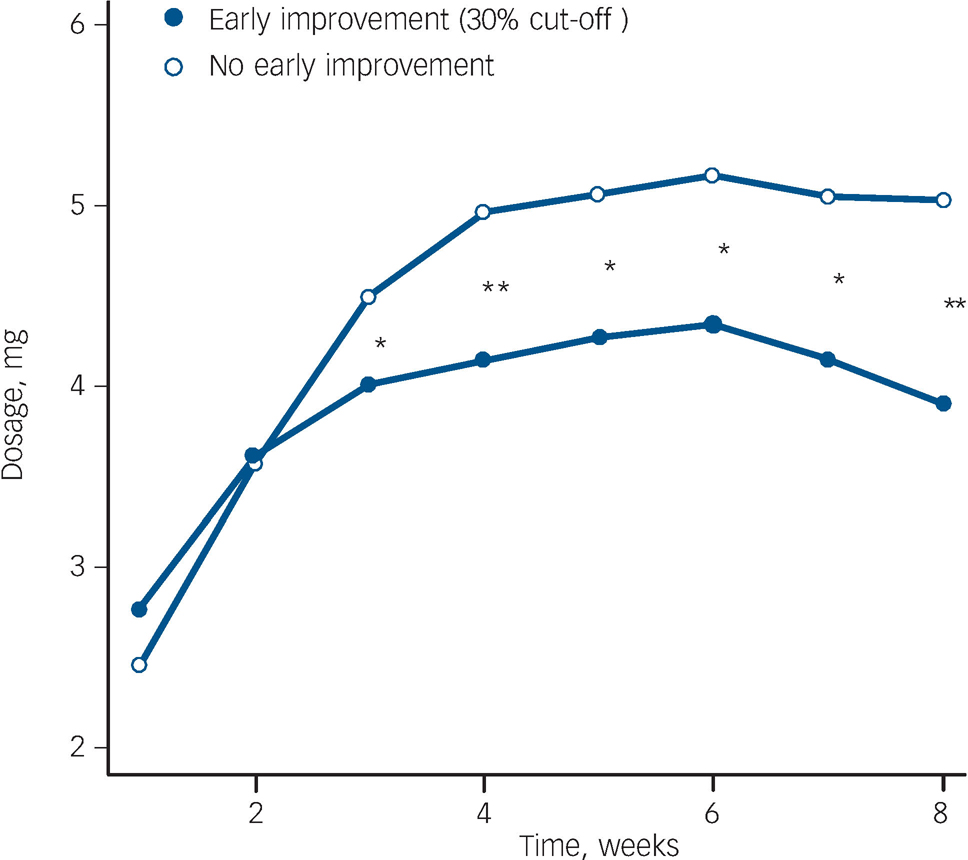

The confidence intervals of a 26–60% PANSS total score improvement to predict response and a 28–61% improvement to predict remission seem rather impractical. Therefore, we propose a 30–60% reduction as definition of early improvement, suggesting that a patient should improve by at least 30% in PANSS total score. The time course of the PANSS total score comparing patients with early improvement and those without early improvement (30% reduction) is shown in Fig. 3. Patients achieving this cut-off v. those not achieving it were further compared regarding the mean dosage of antipsychotic medication prescribed (Fig. 4). Patients with early improvement were significantly more likely to become responders (P<0.001) as well as remitters (P<0.01) compared with patients not achieving the 30% improvement. No significant difference was found in a comparison of the two subgroups in terms of duration of current hospital treatment (P = 0.72) and gender (P = 0.29). Patients with early improvement were found to be significantly older than patients not achieving early improvement (P<0.01).

Fig. 3 Comparison of mean Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total scores of patients achieving or not achieving the proposed 30% cut-off score. LOCF, last observation carried forward.

Fig. 4 Comparison of mean antipsychotic dosages applied in patients achieving or not achieving the proposed 30% cut-off score. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (Wilcoxon rank sum test).

Patients fulfilling the proposed improvement criteria at week 2 and achieving subsequent response and remission

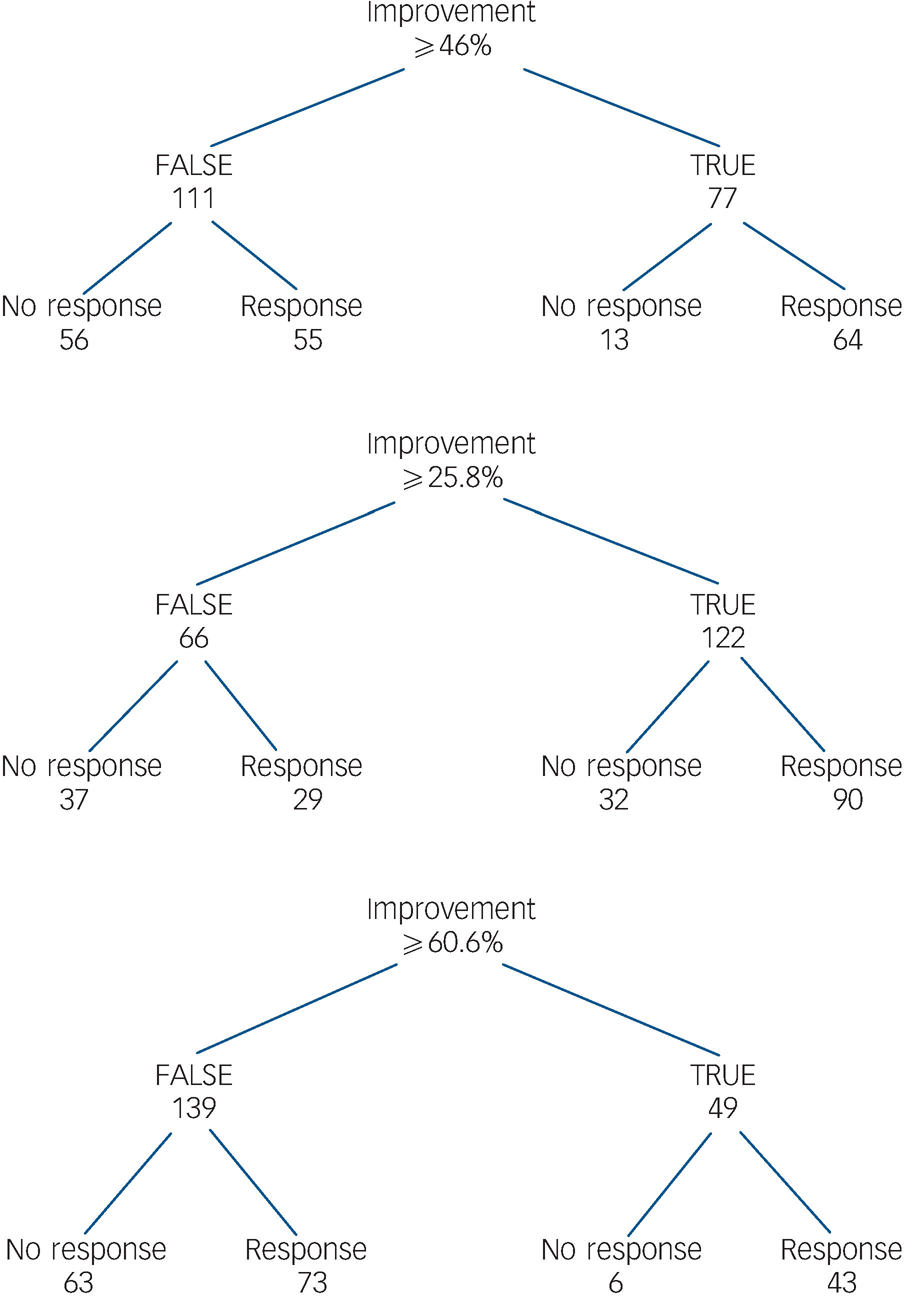

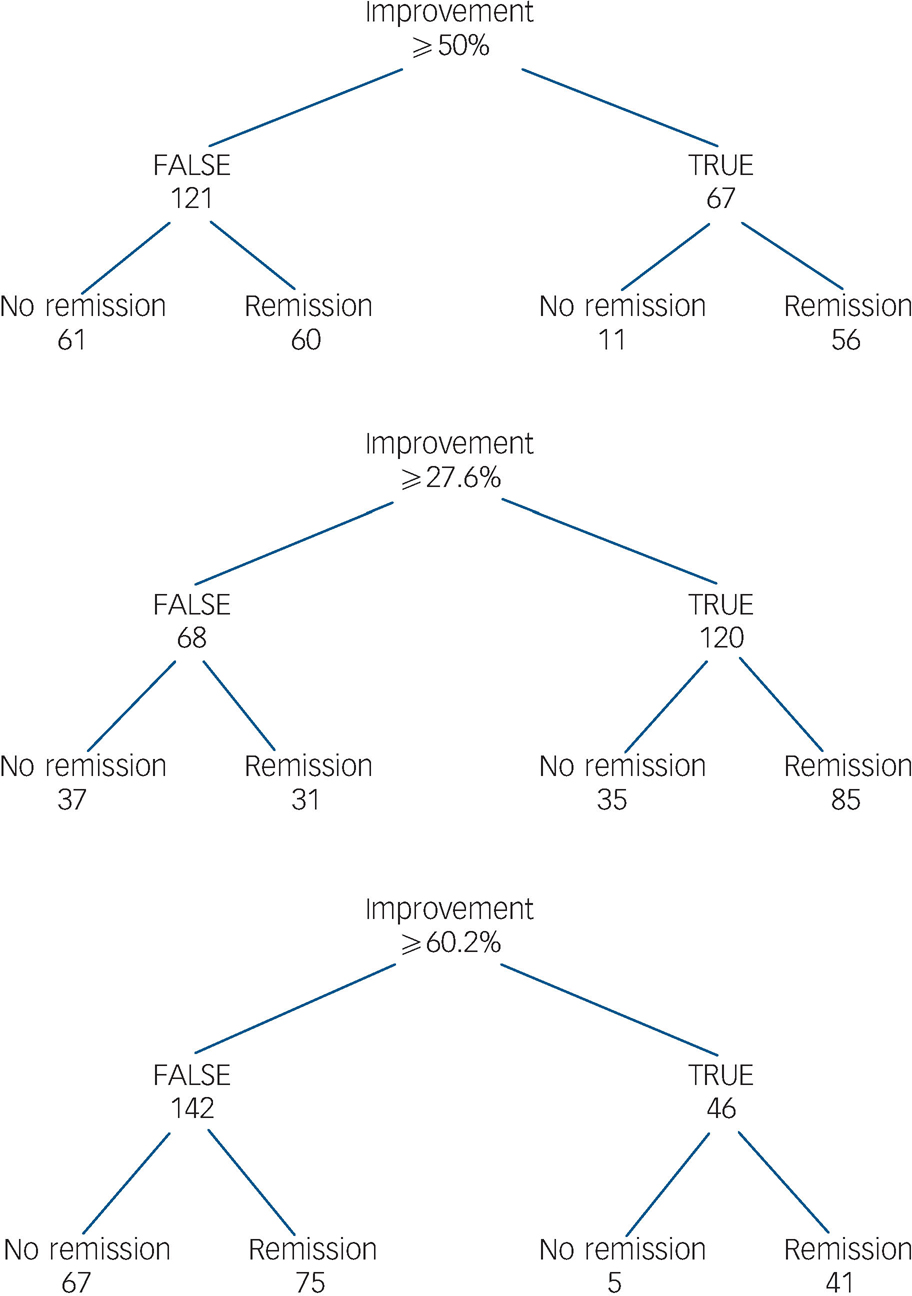

Patient subgroups were formed according to achievement of the proposed cut-offs (numerical cut-off, lower and upper cut-off of the proposed cut-off interval) and subsequent response (Fig. 5) and remission (Fig. 6).

Fig. 5 Patients with early improvement and subsequent response/non-response.

The figure shows early improvers at week 2 who achieved the numerical cut-off, the lower cut-off of the proposed interval and upper cut-off of the proposed interval and those patients who concurrently achieved response/non-response.

Fig. 6 Patients with early improvement and subsequent remission or non-remission.

This figure shows early improvers at week 2 who achieved the numerical cut-off, the lower cut-off of the proposed interval and upper cut-off of the proposed interval and those patients who concurrently achieved remission/non-remission.

Discussion

The rates of treatment response (63% of patients) and remission (62% of patients) at week 8 are in good agreement with those reported by other authors. Reference McCreadie24 Additionally, we were able to replicate results of recent studies demonstrating that early improvement is a valid predictor of subsequent response and remission. Reference Correll, Malhotra, Kaushik, McMeniman and Kane2,Reference Leucht, Shamsi, Busch, Kissling and Kane3,Reference Chang, Lane, Yang and Huang25,Reference Leucht, Busch, Kissling and Kane26 It is well known that patients with a first psychotic episode will more often respond to antipsychotic treatment and show a favourable treatment outcome compared with those who have multiple episodes. Reference Ceskova, Prikryl, Kasparek and Ondrusova27 Almost 80% of the examined patients achieving response or remission achieved both outcome criteria concurrently, which might be surprising at first. Again, this may be due to the homogeneity of the patient sample, and to the fact that only the symptom severity component of the remission criteria was applied. Comparative literature examining response and concurrent remission is sparse. However, results from the European First Episode Schizophrenia Trial report response and remission rates differing by about 15–20%. Reference Boter, Peuskens, Libiger, Fleischhacker, Davidson and Galderisi28 It has to be kept in mind, however, that patients had to maintain the symptom severity component for 12 months rather than 8 weeks as in our study, which might explain the different results.

Comparison of first- and second-generation antipsychotics

We found no significant difference between first- and second-generation antipsychotics in response or remission rates, or concerning the predictive validity of early improvement. When examining the percentage reduction in the PANSS total score at week 2 we found no significant difference between the two medication groups, suggesting no difference with respect to early improver rates. These results resemble data deriving from clinical as well as double-blind controlled trials which have found almost no significant differences in efficacy when comparing a first- and a second-generation antipsychotic. Reference Schooler, Rabinowitz, Davidson, Emsley, Harvey and Kopala9,Reference Crespo-Facorro, Perez-Iglesias, Ramirez-Bonilla, Martínez-García, Llorca and Luis Vázquez-Barquero29,Reference Emsley30

Developing a valid definition of early improvement as predictor

Different definitions of early response, such as a Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale positive score reduction of 4 at week 1 to best predict response at week 4, Reference Lin, Chou, Lin, Hsu, Chen and Lane4 or a <20% or >20% PANSS total score improvement at week 2 to best predict subsequent response, Reference Correll, Malhotra, Kaushik, McMeniman and Kane2,Reference Chang, Lane, Yang and Huang25 point out current inconsistencies in the definition of such response. In addition, some proposed cut-off points were chosen arbitrarily, emphasising the need for a systematic analysis. Therefore, sensitivity and specificity analyses were performed to find the most suitable cut-off that predicts response and remission. At week 2, a 46% improvement in the PANSS total score was found to best predict response and a 50% improvement to best predict remission.

Proposal of a cut-off interval as definition of early improvement

Despite the common use of such sensitivity and specificity ROC analyses, this procedure also has its disadvantages. The main problem is that the results often cannot be generalised because they depend heavily on the patient sample. Even small changes in the data can change the resulting cut-off enormously. In our view this can also explain the diversity of proposed definitions of early improvement. In order to adjust for the dependency of the underlying sample we additionally computed bootstrap intervals by using resample methods. Reference Efron and Tibshirani31 The results are confidence intervals that by definition cover the true cut-off for the population of patients with a first psychotic episode with a probability of 95%. In addition, a cut-off interval provides a minimum score, meaning that this percentage reduction in the PANSS total score should at least be achieved by the patient. By presenting an upper range the cut-off interval demonstrates that there is a variety of appropriate cut-offs to predict subsequent outcome and with this it indicates a trend more than an all-or-nothing condition.

Interval of 30–60% of early improvement

Statistical analysis found a confidence interval of a 26–60% PANSS total score improvement to predict response and a confidence interval of a 28–61% improvement to predict remission. Owing to the heavily overlapping intervals it appears that response and remission can be predicted using the same range. This can partly be explained by finding similar response and remission rates. Besides, in first-episode schizophrenia early improvement seems almost equally important regarding treatment response and improvement in core symptoms.

As mentioned above, since both 26% and 28% are impractical, we suggest instead an interval of 30–60%. Our results indicate that a patient with a first psychotic episode should achieve at least a 30% PANSS total score improvement after 2 weeks to best predict treatment response or remission. This empirically derived cut-off value is high compared with recently proposed cut-off values which usually rely on a 20% improvement. Reference Kinon, Chen, Scher-Svanum, Stauffer, Kollack-Walker and Sniadecki17,Reference Scher-Svanum, Nyhuis, Faries, Kinon, Baker and Shekhar32 In particular, the 60% improvement after two treatment weeks seems too strict at first glance, even for first-episode schizophrenia. However, in our study we found that 23% of the patients who had achieved a 60% PANSS total score improvement at week 2 were concurrently responders at week 8, and that 22% of the patients were in remission (see Figs 5 and 6). This suggests that a 60% improvement at week 2 predicting subsequent response and remission is not unrealistic in first-episode disorder, indicating that it might be more appropriate to choose stricter cut-offs in such cases, thereby maybe falsely ‘overtreating’ early responders rather than missing early non-responders.

The possibility of a comparison with other trials evaluating antipsychotic treatment response in a double-blind design with risperidone and haloperidol in first-episode schizophrenia is limited. Examining the time course of antipsychotic treatment response, Emsley et al found a total of 47% patients achieving a PANSS improvement of at least 20% by week 2. Reference Emsley, Rabinowitz and Medori33 In our trial 70% of the patients improved by at least 20% at week 2. This discrepancy in response rates may be explained by several trial- and protocol-specific reasons. Reference Emsley, Rabinowitz and Medori33 Interestingly, when using sensitivity and specificity analysis in a naturalistic study design examining a heterogeneous patient population, Jäger et al found a 30% PANSS total improvement at week 2 to best predict subsequent response. Reference Jäger, Schmauß, Laux, Pfeiffer, Naber and Schmidt34 This also supports the conclusion that the proposed cut-off interval is a suitable landmark to evaluate early treatment improvement and thereby optimise treatment outcome.

Clinical implications of using 30% improvement to predict outcome

Our results imply that patients should improve by at least 30% in PANSS total score to achieve subsequent response and remission. We did not find significant differences in the dosage applied comparing patients with or without 30% early improvement in the first two treatment weeks or in the type of antipsychotic drug. As can be seen in Fig. 2, clinicians intuitively treated those not showing early improvement with significantly higher doses from week 2 on. Interestingly, despite receiving significantly more antipsychotic medication, these patients still achieved response and remission significantly less often. This suggests that a dosage increase might not be enough, and that a change in antipsychotic compound or the implementation of further treatment strategies is necessary to ensure a satisfactory outcome. Future studies need to evaluate the proposed cut-off interval and to reassess the benefit of treatment adjustment for patients not improving initially.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study include the fact that all patients examined had first-episode disorder, as well as the use of standardised assessment, the chance to test early improvement for both a typical and an atypical antipsychotic, and the double-blind design. Limitations are the strict study protocol reducing the generalisability of the results, as well as the small number of participants. The time criterion of the applied consensus remission criteria was not considered. Unfortunately, it was only possible to evaluate early improvement and its predictive validity within the first 8 treatment weeks, thereby excluding long-term data. Although a simple dosage increase seemed an insufficient strategy for those who did not show early improvement, we did not examine whether a change of treatment in such patients would influence subsequent outcome, because the treatment applied at admission was continued. The flexible dosing again presents both an advantage, in meeting clinical practice, and a limitation, in eliminating examination of the time to respond to a specific dosage.

Funding

This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research BMBF (grants 01 GI 0032, 01 GI 0232). Risperidone and haloperidol, and the blinding and randomisation procedure, were provided by Janssen-Cilag, Germany. This study was conducted within the framework of the German Research Network on Schizophrenia, which is funded by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all those who were involved in the study, especially Mrs Thelma Coutts for editing the manuscript.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.