The contract that accompanied a reel-to-reel tape of Sunday Morning Blues likely gave Cornelius Cardew a laugh. It stipulated, his biographer and long-time collaborator John Tilbury writes,

that the tape be returned ‘immediately on demand’; that Cardew ‘agrees not to perform the Tape or the actual music recorded on the Tape, publicly or for profit’; that he ‘agrees not to permit any copy of the Tape or the music on the Tape to be made on tapes or recorders or any other form of reproduction’, that he ‘agrees not to perform the Tape or any of the music recorded on the Tape at private gatherings where it has been previously announced that the Tape shall be performed’; that he ‘agrees not to permit any kind of performance, copy, or reproduction of the Tape or the music recorded on the Tape, without the express written consent of the composer’; and so forth.Footnote 1

In the contract dated 4 May 1967, La Monte Young was carefully defending from free circulation a recording he had made on 12 January 1964 with his collaborators John Cale, Tony Conrad, Angus MacLise and Marian Zazeela. Tilbury tells us that Cardew felt a ‘genuine commitment to [Young’s] music whilst at the same time keeping the composer at arm’s length’ in light of Young’s ‘anxiety that his works were being relayed to the public in a perfunctory and inappropriate fashion’.Footnote 2 Such anxiety has remained a hallmark of Young’s perfectionism; a recent profile in the New York Times tells us that Young has recorded every single rehearsal and performance of his work that he has taken part in, though he has only released six commercial recordings of his music.Footnote 3 Despite Young’s best efforts at containment, Cardew placed little value in the contract. A few weeks later, Young had to write to Cardew again to remind him of the terms of the loan: a British listener had written to Young asking how to hear more of his music after having received a copy of the tape from Cardew.

The effort to limit the free and ‘perfunctory’ circulation of his work has led to Young issuing many contracts with his collaborators. Conrad and Cale claim that it was such a contract offered up in 1987 that lifted their collaborative work as the Theatre of Eternal Music – including the Sunday Morning Blues tape – to its simultaneously mythical and polemical position. In response to an offered multi-record deal with the record label Gramavision, Young asked Conrad and Cale to sign contracts acknowledging their role on these tapes as performers in music that was composed solely by Young. Both Cale and Conrad were shocked: as they had always understood it, the Theatre of Eternal Music took on the name and performed its drones precisely to escape the archaic social role of the composer in favour of a collective ideal of composition. Indeed, they felt that tapes like Sunday Morning Blues, though physically held in Young’s Church Street archive, were their collective property and were available as copies at any time on request.Footnote 4 Conrad, Cale and others who have mentioned these contracts have never been able to show me one as archival evidence; unlike Cardew’s, they were not sent in the post. As David Rosenboom told me of his own contract with Young after he joined the re-formed Theatre of Eternal Music in 1969, Young was never in the business of providing signatories with carbon copies.Footnote 5

The very need for contracts points to the dangers of magnetic tape as a storage medium for a composer of Young’s tendencies. When Cardew and Young met at Darmstadt in 1959, for example, scores would have changed hands readily: clearly signed by its singular author and empowered through its ontological status as directions for performance, the score is itself a contract outlining mutual obligations, motivating analysis or performance under the auratic genius of the above-signed composer. The subsequent property claims made through such documents are rarely questioned. Magnetic tape is another matter altogether. With its lack of a score and its clear focus on a drone performed and rhythmically supported by five musicians, how are we to understand the authorial guarantee of Sunday Morning Blues or any of the other tapes by the Theatre of Eternal Music? Young’s anxieties were perhaps well founded, and a written contract – one that limited circulation until he found a more appropriate solution to his authorship problem – was an elegant means of ensuring the legal status of drones collectively recorded to tape in the absence of authorial documentation. The legalistic delimitations in the letter to Cardew nevertheless clearly failed Young: already by 1967 these tapes were circulating beyond his control, arriving in the hands and ears of listeners unaware of how to account for the propriety of the sounding practice that they reproduced.

This essay offers a historical account of the tapes of the Theatre of Eternal Music which have escaped Young’s control to circulate broadly online or as bootleg tapes. I pay particular attention to each bootleg’s origin to consider the tense relationship between Young’s claim that he is the sole author of the drones on the tapes and the insistence by Conrad and Cale that the tapes are material evidence of a collective politics of authorship. That is, I contend that we can often learn more from the distribution and source of the recordings than from their musical contents. We still have nowhere near the 40 hours of tape that Young told Peter Yates about in November 1965,Footnote 6 but recordings of the ensemble circulate online as a result of surreptitious leaks from other archives and bootlegs made from radio broadcasts. As a result, the Theatre of Eternal Music engages an enthusiastic community of online fans of experimental musics who share the recordings in fan-curated albums and massive torrent files that collect, in total, and despite their profusion of metadata labels, only about ten recordings from the period 1963–6. It is not in spite of but because of their cloistered public profile that these tape recordings have drawn such awed admiration. Beginning in the early 2000s, online music sharing communities like Napster and torrent websites regularly included the group’s music, the famously unwieldy titles often mislabelled by reticent admirers speaking in hushed tones of these obscure bootlegs as the holy grail of experimental music.Footnote 7 ‘How can you upload such fine music in 128kbps?’ one commenter asked of a 1.6GB torrent file that includes most of the available tapes as part of a collection of Young’s work. ‘I’m sorry, but that’s just pure destruction of art.’Footnote 8 While I avoid such reverence, I agree with these online archivists, as well as Young, Cardew and Conrad, on one central point: in the life of the Theatre of Eternal Music, it’s all about the tapes. They are much more than just a record of the group’s performance practice; through their circulation one hears testimony to Young’s secrecy, his archivists’ distaste for it, the Theatre of Eternal Music’s compositional process and the infeasibility of suppressing music while using it to build an autobiographical narrative. My core argument is that the Theatre of Eternal Music names the process by which the sole authorship claim of Young was rightly challenged and authorship was redistributed equitably across all four members of the collective. That process took place through several interrelated aesthetic and political priorities: the different, though related, prior impacts of models of textural and organizational egalitarianism in free jazz opened by Ornette Coleman; the emergent supremacy of their drone over any single performer’s virtuosity or individuality, even to the point of timbral indistinction; and their collectivist and deliberative practice of daily rehearsal and listening.

Bootlegs and tapes, public and private

Above I claim that there are about ten recordings of the Theatre of Eternal Music circulating online as bootlegs from the period 1963–6; the date of instantiation of performances under the ensemble’s name (examined below) and the changing roster of performer-participants creates some difficulty in offering an exact count. I focus on recordings of the quartet of Young, Zazeela, Cale and Conrad because this was the group that took on the name the Theatre of Eternal Music in late 1964. As I am concerned about being precise about the activities of this core group between August 1962 and August 1966, I avoid eliding changes in the ensemble’s make-up, performance practice or sounding compositions. A major fault in writings about the ensemble to date has resulted from Young – and subsequently historians who rely on his oral history – turning the supposedly ‘eternal’ drones that the ensemble performed together into the foundation of what Branden Joseph criticizes as the ‘metaphysical history of minimalism’.Footnote 9 These accounts treat the Theatre of Eternal Music as playing a single drone written by Young during its whole tenure; this monolith then becomes a consensual origin of the unchanging or repetitive nature of musical minimalism. My concern, here and in other writing, is not to challenge the originary importance of the ensemble’s drones to musical minimalism, but rather to crack open its monolithic historiography to introduce, in place of Young’s singular drones, a germinal dispute over the possibilities of collective authorship, and the sonic and discursive framing of the challenge to singular authority at the foundations of minimalism.Footnote 10

The sections below split the recordings into three historical eras based on group constitution, political organization and resulting sound: first, a single tape from 1962; second, the ‘fast saxophone’ tapes recorded between autumn 1963 and early 1964; finally, mid-1964 to summer 1966. In the first two periods, Young played sopranino saxophone and the drone was unamplified; in the third, Young joined in the drone as a singer, with all members heavily amplified as a means of ‘getting inside the sound’ through sonic disambiguation. An important transition between the second and third phases, marked by the Pre-Tortoise Dream Music tape of April 1964, is discussed at length below. Against the above monolithic ideal of Young’s drone ensemble, I track changes in the group’s sound as members came and went, thus carrying forward the sound alongside Young, rather than under his direction. The Theatre of Eternal Music names a very specific collection of performers as well as a performance practice, sound, and organizational structure, the instantiation of which can be dated specifically to late 1964. Table 1 lists the recordings accounting for date,Footnote 11 performers involved, length and origin of the tape (where known). It is not lost on me that I am including the fast saxophone recordings that Young taped before the Theatre of Eternal Music was named as such, and leaving out the recordings he made under that name after Conrad and Cale left, including commercial recordings and performances up to the present.Footnote 12 I am interested in group dynamics between Cale, Conrad, Young and Zazeela. In keeping with the widespread understanding that this group of people constitutes the historically significant Theatre of Eternal Music, I use that name as a convenient and well-known appellation while carefully articulating its historical use and appearance. I do not intend that this focus detract from future research of the later Theatre of Eternal Music, which was, by contrast, definitively Young’s ensemble.

Table 1 Recordings of The Theatre of Eternal Music available online

| Date | MacLise ‘Year’ title | Young & Zazeela title | Performers/instruments | Length | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 X 63 | fifth day of the hammer | B♭ Dorian Blues | LMY ss, MZ vd, AM hd, TC bg, JC vla | 11m 55s | Young & Zazeela (incl. on WKCR) |

| 30 X 63 | day of hummingbird night | N/A | LMY ss, MZ vd, AM hd; [unsure:] TC vln? | 12m 40s | unknown |

| 28 XI 63 | the overday | N/A | LMY ss, MZ vd, AM hd, TC bg | 18m 51s | Young & Zazeela (incl. on WKCR) |

| 17 XII 63 | the fire is a mirror | N/A | LMY ss, MZ b gong & vd, TC bg, JC vla, TJ sop s | 15m 6s | Young & Zazeela (incl. on WKCR) |

| 24 XII 63 | third day of yule | Early Tuesday Morning Blues | LMY ss, MZ vd, JC vla | 12m 56s | Young & Zazeela (incl. on WKCR) |

| 12 I 64 | the first twelve | Sunday Morning Blues | LMY ss, MZ vd, AM hd, TC bg, JC vla | 11m 35s | Young & Zazeela (incl. on WKCR) |

| 2 IV 64 | day of the holy mountain | Pre-Tortoise Dream Music | LMY ss, MZ vd, TC b strings, JC vla, TJ sop s | 34m 30s | Young & Zazeela (incl. on WKCR) |

| 25 IV 65 | day of niagra | N/A | LMY vd, MZ vd, TC vln, JC vla, AM hd | 30m 54s | Dreyblatt / Table of the Elements |

| 15 VIII 65 | day of the antler | N/A | LMY vd, MZ vd, TC vln, JC vla | 26m 9s | unknown |

| 30 VII 66 | [day of the millstone] | The Celebration of the Tortoise | LMY vd, MZ vd, TC vln, TR vd | 30m 46s | Young & Zazeela (incl. on WKCR) |

LMY = La Monte Young; MZ = Marian Zazeela; AM = Angus MacLise; TC = Tony Conrad; JC = John Cale; TJ = Terry Jennings; TR = Terry Riley

b = bowed; bg = bowed guitar; hd = hand drums; sop s = soprano saxophone; ss = sopranino saxophone; vd = voice drone; vla = viola; vln = violin

Note: All lengths refer to the most common circulating bootlegs, not necessarily to the original tape. Many vary with tape speed.

Categorizing and analysing these tapes raises issues in terms of sound quality, origin and title. They were originally made with affordable gear in the 1960s, often under the influence of a lot of drugs; copies were then made from these masters, which were broadcast on the radio; these broadcasts were then taped over the air by enthusiasts. The most notable of these broadcasts (though not necessarily the source of the bootlegs circulating online) was the 24-hour La Monte Young Festival hosted by Brooke Wentz and broadcast on Young’s forty-ninth birthday in 1984 by New York radio station WKCR. Michael Gerzon, a young tape enthusiast, recorded the broadcast off the air and deposited it in the British Library – in spite of some complaints from Young – as part of his massive collection of tapes.Footnote 13 As it was the most substantial public presentation of Young’s tape archive as sourced and curated by him, I used Gerzon’s recording of the WKCR broadcast to confirm details, titles and lengths of the dubious online versions. Lastly, the multiple generations of copies involved in circulating recordings have often resulted in them being erroneously re-labelled by online communities of file-sharers, who themselves build from the methods – who knows which – of those who pressed and sold real (that is, physical) bootleg LPs, tapes and CDs of the group’s music. Jeremy Grimshaw notes that Young’s ‘ornamental acoustic taxonomies’ create ‘hermeneutic intrigue’ for audience members kept in the dark about their meaning.Footnote 14 It is because of these titling practices – that often include idiomatic inscriptions of dates, tuning practices and other cryptic poetic allusions (often so long that I won’t reproduce any to make the point)Footnote 15 – that, for example, a bootleg cassette released by the Velvet Underground Appreciation Society (and also appearing on the bootleg Der Zweck dieser Serie ist nicht Unterhaltung) lists ‘B♭ Dorian Blues (The 28th/63 Of the Over Day) (1963)’. The person or people at the VUAS who created the tape evidently had some sense of Young’s titling practices, but probably confused his use of just intonation integer ratios with his dating conventions so that 28 XI 63 (28 November 1963) becomes ‘The 28th/63’.Footnote 16

Against Young’s own mystical proclivities, the materiality of these bootlegged tapes is an integral part of the history of this music, and minimalism more generally. As such, my attention will be more often on the source of the tapes – their audiences, listeners, bootleggers, broadcasters and commentators – than on formal analysis of the music that they contain. It is definitive of this music that most listeners are acquainted with it through poorly copied MP3s. Indeed, it is perhaps the great irony – or tragedy – of Young’s career that, directly as a result of his exceedingly high standards of recording quality and release, most people know this important era of his early career through multiply transcoded rips of bootleg LPs, cassettes and CDs that were themselves made from rips of radio broadcasts of music that was, in the first place, made under less than ideal circumstances. Young sought to stem this circulation, even as early as his 1967 letter to Cardew; the music of the Theatre of Eternal Music is defined by its status as a collection of fugitive tapes articulating a lo-fi rebuttal to Young’s effort to recreate pristine, eternal conditions for his work. The tapes attest to the impracticable fiction of Young’s conception of authorial propriety and sonic purity. I explore this issue as a music-historical one in relation to their politics of timbral indistinction in the final section and conclusion.

A brief history of the ensemble

The group that would begin performing under the name the Theatre of Eternal Music in late 1964 first performed together in a series of concerts held at New York’s 10–4 Gallery in the summer of 1962.Footnote 17 There, Young drew together a small backing band to support his extremely fast modal permutations on sopranino saxophone. His rhythmic acuity was matched by the hand drummer MacLise, and both were supported by vocal drones sung by a revolving cast that included on different occasions during their residency Zazeela, Simone Forti and Billy Name. MacLise, Young and Zazeela continued playing together regularly with other infrequent collaborators. Conrad, a mathematician and violinist with whom Young had corresponded for years, attended some of the performances at the 10–4 Gallery and joined the regular rehearsals in the spring of 1963. The Welsh musician Cale, a former student of Cardew, became part of the group the following September on droning viola. Throughout that autumn and winter, the quintet of Cale (viola and other strings), Conrad (violin and other strings), MacLise (hand drums), Young (sopranino saxophone) and Zazeela (voice drone) – often supplemented by Terry Jennings (soprano saxophone) – rehearsed daily and developed a tripartite textural structure. Young played rapid, modal saxophone permutations modelled on John Coltrane’s ‘sheets of sound’ against MacLise’s erratic, post-Beat hand drums, and Zazeela, Conrad and Cale sustained an inflexible voice+string drone.Footnote 18 The drone increased in stability and force over time as the players’ intonation became more precise, allowing their instruments’ upper harmonics to interlock and resonate together. In the spring of 1964, following MacLise’s departure from the ensemble, Young’s saxophone playing became both texturally out of place and harmonically out of tune as Conrad and Cale began heavily amplifying their strings, further enlivening the drone and its upper harmonics. Young thus joined Zazeela on voice drone that summer. It was during this period – outlined in more detail below – that all four members began performing a singular voice+string drone in sustained just intonation and the group took on the collective name the Theatre of Eternal Music. Occasional performances supplemented daily rehearsals throughout 1964 and 1965 before Cale left the group in December 1965, at which point Terry Riley joined as a third vocalist. Following a few more performances, the group ceased their regular rehearsals and performances in August 1966. The daily rehearsals had allowed members collectively to listen to, discuss and uphold their meticulously tuned drone for, reportedly, hours at a time. Precision was key, as even minute shifts in intonation or dexterity produced rhythmic beating that Conrad later described as ‘glaring smears across the surface of the sound’.Footnote 19 It was during these rehearsals in Young and Zazeela’s loft at 275 Church Street in downtown New York that most of the tapes available online were recorded, and subsequently held in their extensive archive.Footnote 20

In 1987, as part of an intended multi-album contract with Gramavision Records, Young asked Conrad and Cale to sign documents recognizing themselves as performers on their collaborative tapes, with Young as the sole composer. Conrad was incensed and began an extended and multimedia attack on Young. This included pickets at Young’s 1990 performances at the North American New Music Festival in Buffalo, interviews and writings, including the extensive booklet note essays for Early Minimalism: Volume One (Table of the Elements, 1997) and Slapping Pythagoras (Table of the Elements, 1995), the latter of which Grimshaw calls a ‘thinly disguised tirade against Young’.Footnote 21 Across these writings, Conrad insists that the ensemble articulated a politico-aesthetic concern for the drone: it was both of inherent musical interest, and simultaneously offered a challenge to the outdated role of the singular composer in that the group made compositional decisions collectively. Indeed, the drone was a vehicle for this decision-making process as compositional choices were minimized to include only which pitches to add to the drone, thus allowing group deliberation rather than monodirectional instruction from a singular composer to a group of lesser collaborators. Conrad writes that they managed to ‘dispense with the score, and thereby with the authoritarian trappings of composition, but […] retain cultural production in music as an activity’.Footnote 22 Generations of musicians working in popular forms, as well as free jazz artists in their same neighbourhood at the time, had of course done similar work.

When we played together it was always stressed that we existed as a collaboration. Our work together was exercised ‘inside’ the acoustic environment of the music, and was always supported by our extended discourse pertinent to each and every small element of the totality […] Much of the time, we sat inside the sound and helped it to coalesce and grow around us […] In keeping with the technology of the early 1960s, the score was replaced by the tape recorder. This, then, was a total displacement of the composer’s role, from the progenitor of the sound to groundskeeper at its gravesite.Footnote 23

For Conrad, then, the group’s efforts differed in that they imagined themselves as staging a revolution within the discursive and organizational realm of art music, replacing the heteronomous power of the composer with a form of collective autonomy, articulated through listening, deliberative discourse and creating the sound as a space in which to live and work.

Young refused this collectivist and anti-composer articulation of the narrative. The dispute reached its peak in 2000 when the Table of the Elements record label released, without Young’s permission, a 1965 tape called Day of Niagara (discussed below).Footnote 24 Young responded with a 27-page open letter attacking the release and Conrad’s position. In the letter, Young places his own understanding in historical and legal context:

Perhaps in part because of the stability that notation provided, Western music has also produced the most radical departures from what has been conventionally understood to be composition. For instance, we have the extreme example of aleatoric music, such as the music of John Cage, in which the composer may instruct the performer to ‘play any sound,’ yet Cage remains the composer of the sounds performed, albeit not the creator of the sounds! There is no definition of music composition to be found in Grove’s or Harvard, and we are still researching to see if we can turn up a clear legal definition of composition. In any case, at the time that The Tortoise and the other works were being performed by The Theatre of Eternal Music, a work had to be submitted in written form to be registered with the Copyright Office. Since the Copyright Act revision of 1978, sound recordings can be used as deposit copies when registering music compositions, and I have registered the copyright on the composition embodied in the Original sound recording of ‘April 25, 1965 day of niagra’ [sic] from The Tortoise, His Dreams and Journeys, aka ‘day of niagara’.Footnote 25

A discursive eruption ensued, including open letters from both Conrad and composer and artist Arnold Dreyblatt (who had copied one of Young’s tapes in the 1970s and given it to Jim O’Rourke before it arrived in Conrad’s hands),Footnote 26 glowing reviews of the album, stories in The Wire on Conrad, Cale and Young and Zazeela,Footnote 27 and an overview in the New York Times. Footnote 28

Across his writings and interviews, Conrad has consistently argued for the ensemble as a collective, with their political organization and musical focus interconstituted in relation to the potential of drone to limit composerly authority. What Young considered a composer’s inherent rights – that one could write down ‘play any sound’ and then claim ownership of the sounding result – Conrad marks as a core problem of Western art music’s authorial concept. In the late 1980s and 1990s, protest became a central medium for how Conrad undertook his work, often focused on public access to media resources, education and egalitarianism. When Young performed in Buffalo in April 1990 as part of the North American New Music Festival, Conrad picketed the venue, holding a placard headed ‘Composer La Monte Young Does Not Understand “His” Work’.Footnote 29 A seven-point critique followed, outlining what Conrad considered Young’s (mis)understanding of the Theatre of Eternal Music, an ensemble that was ‘collaboratively founded’ in 1964, ‘and was so named to deny the Eurocentric historical/progressivist teleology then represented by the designation composer’. The group performed ‘carefully structured improvisation and long durations’ in just intonation, but Young suppressed recordings of their work which he considered unflattering to him. He subsequently, the placard continues, enacted a ‘conservative gutting’ of each of these radical elements to instead ‘perpetuate’ the ensemble as solely ‘his exploitative and artistically minded enterprise’. For Conrad, in the wake of Young’s contractual effort to outline and demarcate legally their hierarchical obligations as composers and performers, public action became the obvious means by which to bring to light what he considered Young’s regressive ‘gutting’ of their collective dream.Footnote 30

The dispute between Young and Conrad was ongoing when the first histories of minimalism were written, and its terms have thus coloured that history precisely in its absence:Footnote 31 first, because the ensemble always appeared as a moment in the biography of Young; secondly, because Young’s oral history was always the dominant source used by scholars like Strickland, Mertens, Potter and Schwarz; and thirdly, because nearly every one of those histories was written after his dispute with Conrad and Cale over the authorial propriety of their work together.Footnote 32 Critical perspective on its evaluation thus requires movement outside the literature of minimalism; in this vein, I have found recent archival work on experimentalism valuable in framing my approach. Scholars like Benjamin Piekut, Brigid Cohen, Kwami Coleman, Michael Heller and George E. Lewis have turned to unconventional archives of improvised musics that often lack or refuse to create any archival documentation, thus drawing together a partial picture of experimentalist practices from even the most nebulous primary materials.Footnote 33 In contrast to prominent efforts to achieve collective performance and organization during the mid-1960s – AMM, MEV, the Jazz Composers’ Guild or the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians – there is no clear political position to the Theatre of Eternal Music that makes it a model of collectivism in music.Footnote 34 If anything, the ensemble provides a cautionary tale. It does not seem to be the case that Young was out to assert a new model of collectivism with sounding drone as the vehicle. That he and Conrad came into dispute over this fact is both less remarkable than that they ever collaborated so effectively in the first place and, indeed, a testament to the possibility of close partners speaking and acting at cross-purposes, even through daily conversation and rehearsal. The Theatre of Eternal Music offers a rare opportunity through which we can witness, within a demarcated collaborative network, the transition from an early 1960s ‘composer-led ensemble’ to a mid-1960s collectivist band formation – precisely in its ambiguity and tension. In the decades since the last of the tapes discussed below was recorded, in 1966, ‘the Theatre of Eternal Music’ has become recognized as naming a dialectic between a repressive, anxious and paranoid last grasp at the supreme authority of the composer and a public-minded egalitarianism grounded in expanding technologies of circulation and 1960s discourses of collectivism.

‘Somewhere between Bismillah Khan and Ornette Coleman’: intersections with free jazz, August 1962

In the summer of 1962, Young performed a series of concerts at the 10–4 Gallery in New York City. When one considers the relevant collaborative networks, audience constitution and sounding music, these performances draw attention to the close relationship – largely overlooked – between the ensemble that would become the Theatre of Eternal Music and the emergent free jazz scene.Footnote 35 The artist Henry Flynt has been one of the few writers to draw attention to Young’s relationship to free jazz’s major performers.Footnote 36 For Flynt, Young’s saxophone performance style, focused on harmonic stasis, should be considered a third approach to free jazz saxophone alongside Coltrane’s advanced continuation of conventional changes and Coleman’s move into free-form improvisation. Young had sent Flynt a letter in 1959 in which he claimed that ‘Coltrane was the most exciting thing to him that was happening at that time and he also liked Cecil Taylor’. Despite this dual admiration, Young was sceptical towards Coleman. ‘I liked Coleman a lot,’ Flynt told WKCR host Wentz in 1984, ‘La Monte didn’t so much.’Footnote 37

Young’s claimed disinterest nevertheless draws attention to several very close parallels between his career and Coleman’s. First, we can note some close biographical overlap between the two, including having made the move, both stylistic and geographical, from the West Coast cool jazz of the late 1950s to the free jazz of downtown New York in the years 1959 and 1960. Several acetate recordings of Young’s Los Angeles jazz quartet from 1955–6 make the case that Young did indeed have an affinity and public engagement with West Coast bop during the mid-1950s.Footnote 38 The group consisted of Young on alto saxophone, supported by Dennis Budimir or Buddy Matlock on guitar, Hal Hollingshead on bass and Billy Higgins on drums. Within a few years, Higgins became Coleman’s drummer, beginning with his seminal 1959 albums Something Else!!!! and Tomorrow Is the Question, made just prior to the quartet’s move to New York. Young followed that move a few months later.Footnote 39 If Young was not directly influenced by Coleman, he may have been alone; A.B. Spellman wrote that in 1962, New York witnessed an explosion of Coleman-inspired saxophone players.Footnote 40 Young and Coleman also shared not only some side players but, more importantly, elements of their musical approach.

The 10–4 Gallery performances remained something of a pre-historical mystery until quite recently – perhaps in part because accounts of Young’s career take him at his word, outlined to Richard Kostelanetz in 1966, that by the time of his movement to New York, he had stopped performing jazz.Footnote 41 Conrad has commented on having been at some of the 10–4 Gallery concerts, describing them as ‘hysterical and overwrought’: ‘While Young played saxophone, (somewhere between Bismillah Khan and Ornette Coleman), Angus MacLise improvised on bongos, Billy Linich (Billy Name [of Warhol’s Factory]) strummed folk guitar, and Marian Zazeela sang drone.’ He continues, ‘They went on for hours in overdrive, with frequent breaks for the musicians to refresh themselves offstage or in the john. The music was formless, expostulatory, meandering; vaguely modal, arrhythmic, and very unusual; I found it exquisite.’Footnote 42 The recent discovery of a copy of a tape recorded at the 26 August 1962 performance in the papers of Amiri Baraka finally provides an opportunity for this ensemble to be heard.Footnote 43 Whether Baraka himself was present at the concert is unclear;Footnote 44 what seems likely is that Young or Zazeela gave him a copy of their own recording of the performance, at which Baraka may or may not have been originally present. Baraka and Zazeela had already worked together; she designed the lighting for the 1961 production of his play Eighth Ditch, and was a regular contributor to the poetry newsletter The Floating Bear, which Baraka edited with Diane Di Prima.Footnote 45 When Baraka left his editorship, he was briefly replaced by Billy Name, another performer in the 10–4 Gallery concerts. These connections multiply in all directions among the community, which Zazeela described as ‘incestuous’.Footnote 46

Whereas Conrad found the concerts ‘exquisite’, Baraka was less interested. At some point in the following weeks he decided that the concert recording was as good as a blank tape and recorded over most of it with an interview with his friend the saxophonist Archie Shepp.Footnote 47 The conversation largely revolves around whiteness and racism in the jazz industry, referring in particular to Benny Goodman’s 1962 tour of the Soviet Union as an ambassador for American jazz. Shepp nevertheless highlights his respect for white players like Coleman’s bassists Charlie Haden and Scott LaFaro. LaFaro plays so well, Shepp argues, because ‘he must have come face to face with himself at some point and found himself humble before his own slave’. Of Haden, he similarly notes, ‘The only reason Haden could play that way was because he knew he was playing with black men and he knew they could play the music better than he knew it and he went along with it.’ Such commentary leads Baraka to a question – largely inaudible on the tape – in which he certainly mentions the name of the white trumpet player Don Ellis and the idea of ‘Happenings’. Shepp’s response is worth quoting at length:

Yeah. I don’t put Ellis down because of professional ethics or some shit like that. As far as Happenings are concerned, I feel free to talk about them and I think that’s anti-jazz. And I think that it’s being created, for the most part, by people who realize, unfortunately, that they’ll never be able to play jazz. They try to create another image in its place, or else to destroy the aesthetic qualities or the beauties of jazz vicariously through these negative images. Happenings, you know. And again, I think it’s because many whites have never been able to come to grips with the American reality with themselves and with the fact that the negro has seen them probably much better than they see themselves, you know?Footnote 48

Anti-jazz had become a common term in the white-authored and -owned jazz press to label the work of ‘New Thing’ and free jazz players like Coltrane, Coleman, Taylor, Shepp and Eric Dolphy.Footnote 49 In particular, white critics like John Tynan were troubled by these artists’ ‘anarchic’ refusal to swing. The response from contemporary black critics is best summarized in Spellman’s response to these white critics: ‘What does anti-jazz mean and who are these ofays who’ve appointed themselves guardians of last year’s blues?’Footnote 50 Shepp’s use of the term ‘anti-jazz’ redirects the discursive energy; while taking care to note white players whom he respects, specifically for their humility before black collaborators, Shepp insists that ‘Happenings’ are jazz-adjacent performances by white players out to destroy jazz. In the summer of 1962, likely during the weeks of Young’s residency at the 10–4 Gallery, and perhaps in relation to having heard the tape over which his words were being recorded, Shepp is likely commenting directly on trends in performance potentially represented by Young’s quartet.

The fragment of the 26 August performance remaining on the tape shows a clear push and pull between two trajectories: remainders from more song-oriented bebop that Young performed in Los Angeles during the mid-1950s, and emergent trends in New York’s free jazz. He has transitioned from alto to sopranino saxophone, first of all; and rather than soloing over changes as on the Los Angeles recordings, he draws on Coltrane, aspiring to make a chordal aggregate hum through his ‘extremely fast sets of combination permutations’.Footnote 51 Moreover, Young’s playing expands in the 1962 tape into the squealed, vocally inflected shrieks and extended techniques so fundamental to the New Thing sound. This timbral experimentation is balanced by a formal design that indicates, in brief, a relationship to Young’s earlier jazz affiliations. A four-minute span (about one third of the total twelve-minute fragment on Baraka’s tape) finds Young sitting out (something that never happens in the available Theatre of Eternal Music tapes). During this gap, the two vocalists briefly take on a more active role, moving through vowel formants to alter the timbre and overtones of their voices. This ‘drone solo’ is only brief: after Young’s departure has left the voices alone for about ten seconds, MacLise re-enters quietly. Little of MacLise’s erratic performance was ever supportive of Young in any conventional sense, but this is certainly now a solo. MacLise’s improvisation is full of interspersed gaps in which the voices fill the silence with pulsating, buzzing, slightly dissonant, unison droning, more active than what had happened in the full ensemble texture. While certainly not in a conventional bop framework, texturally and formally this certainly recalls traded solos, just as a slow melodic fragment – F–A♭–G–E♭ at 21:32 on the Baraka tape – points to the possibility of a head motif or at least thematic material from which the group was working.

It is impossible to determine the form of an hour-long performance from a 12-minute fragment, but the theme-like content and the traded solos – as well as Young’s stated improvisatory predilections at the time – suggest that the performance was likely a more or less conventional song form on an expanded durational scale.Footnote 52 The tape reveals a push and pull from two directions, neither of which is art music: on the one hand, the group is still emerging out of the mellow, tonal and song-form-reminiscent West Coast jazz of the late 1950s; on the other, they are drawn towards current trends in the emergent free jazz. The music performed at the 10–4 Gallery takes place solidly within the discursive, sonic and social world of downtown jazz in 1962. The difference is that it was presented by a white ensemble, in an art gallery, to a likely predominantly white audience as a concert of avant-garde music.

It is precisely this kind of fugitive escape from the closed Young–Zazeela archive – the discovery of a tape copy in an unexpected archive – that I insist we must follow to pull together an effective history of the Theatre of Eternal Music. While hearing Young’s saxophone playing and textural conception in the summer of 1962 is valuable in itself, we gain even more from the recognition that Baraka had a copy of the tape – and, moreover, that he placed little value on it. Such context has been absent in past writing on the ensemble. One can certainly listen to the 10–4 Gallery performance for how it predicts aspects of the group’s later work – a particularly compelling option for scholars who have taken Young’s claim about leaving jazz behind when he moved to New York as an interpretative imperative rather than a bit of misdirection. But attention to the material history of this tape insists upon the group’s tense entanglement with the black avant-garde. Those elements of the group’s later sound evident in the tape, then, should be heard as inseparable from textural, timbral and formal concepts inherited from free jazz. For players like Coleman or Shepp these practices were the musical trace of political attachment to racial equality. As Stephen Rush has argued, Coleman’s harmolodics has often perplexed readers because it is not a purely formalist-musical concept, but it is simultaneously about racial equality. It has as much to do with band hierarchy – indeed, hierarchy in general – as it does with improvisation and harmonic thinking: ‘Harmolodics is about race. It is about human equality. Equality of tones is about race.’Footnote 53 More recently, Kwami Coleman has rethought Ornette Coleman’s contributions on his 1960 album Free Jazz through the contrast between Eurocentric critical concerns for polyphony (as an imperative to assimilate textural difference into a cohesive order) and heterophony as ‘the dense and opaque sound of decentralized simultaneity’. Indeed, Kwami Coleman clearly articulates how white critics of free jazz aspired to separate the music from ‘the social reality of black musicians’ so as to then reunite them by understanding the music as ‘“noise” that […] could only be explained in the racialized terms of black grievances’.Footnote 54

I contend that with the 10–4 Gallery performances, Young followed a parallel white (mis)reading of Ornette Coleman’s proposed integration of the relationship between political and aesthetic organizational praxis. While the two musics differ markedly, Young and his collaborators followed Coleman’s heterophonic ideal under a collective nomination, oriented towards musical drone rather than a post-bop improvisatory framework. They ignored the racial motivations, choosing instead to treat the formal elements as their own apolitical formalist-positive musical concepts. Baraka warned readers in 1963 about precisely this modality of appropriation. White artists tend to treat black responses to given conditions as ‘universal’ formal ideals; they approach ‘jazz as an art […] that has come out of no intelligent body of socio-cultural philosophy’.Footnote 55 As I will continue to show, Young’s group had moved away from any direct audible connection to free jazz by 1963 and 1964. Nevertheless, the Theatre of Eternal Music drew upon this heterophonic or harmolodic ideal as part of its collectivist poetics; that is to say that the group’s collectivism and heterophony find not only a more compelling musical genealogy but even a more cohesive political one by being read through this connection to post-Coleman jazz rather than through Cageanism and Fluxus. By the time the band began using the collective name in 1964, Young’s ideas about group interaction will have been severed from their racial, stylistic and political underpinnings. Young can join the many white avant-gardists of this period whom George Lewis has discussed in distancing themselves from jazz as a label while holding tight to its many conceptual innovations as pure formalisms.Footnote 56 I am hesitant to treat the group’s borrowing from Coleman as pure appropriation, because I think there is something like a political influence occurring here – an effort to recognize and extend the revelations of Coleman’s band-concept; to treat him, in a sense, as a ‘theorist’ of their sound. At the same time, one cannot deny the structural inequalities in play when we consider that Young could put on such performances free of the accusations of simply expressing racial grievance.Footnote 57 Around the time of these performances, Coleman’s self-produced 1962 performance at New York’s Town Hall included not only his new trio, but also a string quartet that he composed as part of a broader effort to escape the confines of ‘jazz’ discourse and institutions.Footnote 58 The attendant frustrations and difficulties of leaving jazz behind as a black experimentalist in 1962 contributed to his resigning entirely from public performance for two years.

The fast saxophone tapes: October 1963–January 1964

We get a clear sense of Young’s understanding of the Theatre of Eternal Music, and his mobilization of his tape archive to represent it, from a 24-hour radio broadcast on New York’s WKCR in celebration of Young’s forty-ninth birthday. Programme host Wentz was rather prophetic when she told listeners at the start of the show, ‘Tonight you’ll hear lots of music never before heard, and possibly never to be heard again.’Footnote 59 Wentz heroically guided listeners through the entire marathon, joined by a range of guests including Young and Zazeela, Riley, Flynt, Daniel Wolf, C. C. Hennix and others. A substantial portion of the broadcast was given over to tapes of Young’s fast saxophone music, which all participants regularly referred to under the name the Theatre of Eternal Music, including six tapes in the early hours of the show and then – in the only instance of this in the broadcast – a reprise of three of them later on when Young and Zazeela joined the broadcast. (‘The Celebration of the Tortoise’ was played on its own late in the show.) Table 2 lists the recordings aired on the broadcast; while it includes some of Young’s official releases and material commonly available online as bootlegs, it also includes rare material still not circulating online, including the recordings of Young’s 1955–6 jazz quartet discussed above, and Young’s January 1962 piano improvisations alongside Flynt (on the violin) or Jennings (on the soprano saxophone).Footnote 60

Table 2 Track list for WKCR-FM 89.9 La Monte Young Festival (1984)Footnote 63

| [opens with brief excerpt from The Well-Tuned Piano] |

|

Hennix introduces the Theatre of Eternal Music recordings by noting the influence of Coltrane: ‘The idea of playing in modal scales on a short saxophone and for a long and very intense time was established by John Coltrane and picked up by La Monte in a very particular way.’ To best exemplify this, Hennix suggests they listen first to ‘third day of yule’, as it features a pared-down ensemble of Young on sopranino saxophone, Zazeela on voice drone and John Cale on viola. (This is the only recording from 1963–6 that does not feature Conrad, and thus also the only one that features Cale without Conrad.) The recording, at just under 13 minutes, fades in with Zazeela joining Cale’s drone and then, a few seconds later, Young joining immediately in fast saxophone mode; this is paralleled at the conclusion as Young drops out about 14 seconds before the end of the tape, followed by Zazeela and then Cale. Hennix encourages the audience to listen to Young’s ‘rhythm’ and his ‘technique of phrasing’, meaning the incredible speed of his unmetered, modal playing. Against the image of performances lasting for hours on end, the tape is a reminder that the group also regularly performed brief explorations of the drone and permutations concept.

While ‘third day of yule’ was not the earliest recording chronologically, Hennix introduces it first to listeners of the WKCR broadcast because of its drastically pared-down texture. The presence of MacLise on the drums, Hennix notes, ‘will increase the complexity of the music enormously which you may not be prepared for if you haven’t heard La Monte without percussion first’.Footnote 61 When introducing the ensemble before the next tape, ‘19 X 63 / fifth day of the hammer’, Hennix sounds uncertain about those present: ‘So let us now introduce Angus MacLise on hand drums and La Monte Young on sopranino saxophone and I guess who else is on this tape, it’s John Cale and Tony Conrad, what about Terry Jennings or Terry Riley?’ Wentz offers the correct personnel, presumably reading from Young’s notes on the tapes: Young (sopranino), Zazeela (voice drone), Conrad (bowed guitar), Cale (viola) and MacLise (hand drums), and then they begin the tape. ‘fifth day of the hammer’ does not capture a complete performance – most online versions fade out around the 12-minute mark. The background drone is fuller than that of ‘third day of yule’ thanks to the additional presence of Conrad’s bowed strings. Indeed, Conrad, Cale and Zazeela’s drone requires heightened attention to parse distinct instruments or performers – something that will become a definitive theme of their work later. Hennix’s tentative reporting on Conrad’s presence, and indeed choosing as a first tape the only one from which he was absent, suggests that the dispute between Young and Conrad had already begun creeping in even as early as 1984.

‘the fire is a mirror’ stands entirely apart from the other tapes as Cale, Conrad, Jennings, MacLise and Young perform alongside Zazeela on a bowed gong rather than her usual vocal drone.Footnote 62 The complex harmonics produced by the gong (a gift from the sculptor Robert Morris) make it even more difficult to recognize individual instruments on this tape, apart from Young’s saxophone. Indeed, the strings are mostly audible in how they alter the overtones present on the recording: the atmosphere shimmers with shifts in bow pressure, dynamics or pitch as the strings play on what little audible space is left for them within the gong’s sound spectrum. Despite the overwhelming impact of Zazeela’s bowed gong, the tape also paradoxically calls to attention the incredible importance of her strong, firm vocal drone on all other tapes. Indeed, the only unifying sonic element across all of the tapes discussed in this article (with the exception of the bowed gong tape) is Zazeela’s unwavering voice, which Conrad described to me as ‘very fucking good’.Footnote 64 This is particularly clear on ‘12 I 64 / the first twelve / Sunday Morning Blues’, probably the most widely shared Theatre of Eternal Music tape. The drone is on an equal standing in the mix with Young’s saxophone through the force of Zazeela’s voice, which on various tapes can range from near inaudibility, perhaps indistinguishable from the strings, to pervasively sounding a bee-like buzzing that overpowers everything else, as here. Young briefly drops out around six and a half minutes into this performance, but Zazeela’s voice is unwavering, as are MacLise’s percussion and the uncommonly active playing from Conrad, who (uniquely, compared with all other tapes) abandons the held drone in favour of frantic, driving bowing. When Young returns at 7:00, Cale joins him, delivering a strong, low fundamental on E♭. At about eleven and a half minutes, the tape fades out over a quiet drone and sporadic strikes from MacLise. Potter describes the tape as 29 minutes long and in a three-part structure; the bootlegs available online thus give only a partial glimpse of the total recording length.Footnote 65

While no known bootleg lasts for more than about thirty minutes, online communities of fans have consistently simulated the ensemble’s supposed tradition of performing for hours at a time by editing together selections of fast saxophone tapes. For example, a video formerly uploaded to YouTube under the title ‘the fire is a mirror 1963’ creates the impression of a single, hour-long performance by editing together four distinct tapes: ‘third day of yule’, ‘fifth day of the hammer’, ‘the overday’ and ‘the fire is a mirror’.Footnote 66 The pieces are notably in the same order (with omissions) as the portion of the WKCR broadcast devoted to the fast saxophone music.Footnote 67 These (meta)bootlegs – taken down as fast as they appear on sites like YouTube – show that members of the online community were sufficiently engaged with the mythology of this music not only to promulgate its circulation, but also to compile the tapes into fictionalized, extended performances that aim to reflect the rumoured hours-long concerts.Footnote 68 The level of ownership of and responsibility for the music that online communities have shown raises ontological questions about these tapes: must we consider the short versions of ‘the first twelve’ that circulate broadly among numerous fans to be ‘unofficial’ or incomplete versions simply because of the existence of a tape in Young’s archive only heard by a handful of loyal scholars and ‘disciples’?

These fast saxophone tapes define the public perception of the Theatre of Eternal Music. The WKCR broadcast suggests that we should consider many of the circulating bootlegs as representing Young’s curated selection for broadcast, rather than as random scraps that mysteriously escaped from Young’s archive into public attention. They are thus examples of which recordings best represent their work together and, importantly, his narrative of it. Even in advance of the ensemble taking on the collective name, or the sonic and organizational characteristics that impelled them to do so (discussed below), the fast saxophone tapes represent the major body of work associated with the collaborative and drone-oriented activities undertaken by Cale, Conrad, Young and Zazeela in the mid-1960s. What’s more, these tapes make up more than half of the recordings by the quartet and their accomplices circulating online. The tapes’ stylistic consistency and their strong representation in the unofficial archives stands in contrast to the rest of the available archival tapes. We can surmise, then, that it is these tapes that Young considers representative of his collaboration with Conrad, Cale and Zazeela. During this period the group was indisputably a droning vehicle for upholding Young’s sopranino saxophone improvisations, as historians, and Young himself, have claimed, and they were not yet using the collective nomination. It was only from mid-1964 that the balance shifted both musically and politically.

Pre-Tortoise Dream Music: ‘2 IV 1964 / day of the holy mountain’

In the three months of archival silence that follow ‘the first twelve’, the group underwent many changes in performance forces. In February, MacLise left New York to travel to India and Morocco, forcing the remaining members to rethink their organization. Conrad, who had recently graduated from Harvard in mathematics, had over the previous year introduced his collaborators to the means by which just intonation renders pitches as whole number ratios. This contribution already had a decisive impact on how Cale, Conrad and Zazeela understood their choice of pitches. Now Young began sustaining pitches on his saxophone for longer durations in place of his earlier rapid modal permutations as a means of participating in the new orientation towards just intonation. On 29 February, Young made his first venture into composing through numerical tuning ratios, and on 23 March he retuned his spinet piano into something resembling the tuning system later used in his composition Well-Tuned Piano. Footnote 69 That is, he continued solo, compositional work inspired by but separate from the collaborative work of the Theatre of Eternal Music. A few days later, on the night of 2–3 April 1964 (‘day of the holy mountain’ in MacLise’s calendar, which they continued to use in his absence) Cale, Conrad, Jennings, Young and Zazeela recorded another tape that was included in the WKCR marathon. I contend that this tape, which Young and Zazeela have retroactively titled ‘Pre-Tortoise Dream Music’, marks a boundary between Young’s early composer-led ensemble and the emergent, collectivist drone band that would take on the name the Theatre of Eternal Music a few months later.

Despite relying on essentially the same players, the band’s harmonic and textural conception has changed on ‘2 IV 1964 / day of the holy mountain’. In place of an ensemble of droning musicians supporting rhythmically driven duelling improvisations by sopranino saxophone and hand drums, the sound is now centred on a drone around which Young and Jennings weave a melodic line of long, sustained pitches. In his 2000 open letter, Young writes, ‘Without the excitement of [MacLise’s] remarkable drumming technique to play my saxophone rhythms against, I discontinued the rhythmic element.’ He continues, ‘[C]arrying on the inspiration of my previous work with sustained tones, I began to hold longer sustained tones on saxophone.’Footnote 70 Kyle Gann has shown that Young’s performance of a long, repeated melody drastically increases the number of pitches used per octave in contrast to the earlier recordings’ fast modal permutations. The tape also includes the first appearance of Young’s lifelong interest in the thirty-first partial.Footnote 71 Impressive as Young’s playing and Gann’s analysis of it are, listeners unfamiliar with the intricacies of just intonation could be excused for joining contemporary audiences in thinking that Young was simply out of tune: ‘We gave a concert once at Rutgers University while La Monte was still playing saxophone,’ John Cale writes in his autobiography. ‘He stopped playing fast and spent all his time trying to get in tune and couldn’t […] There was a riot; people booed’.Footnote 72 Young’s intention to play within and around what Joseph calls ‘the iron triangle’ of the Cale–Conrad–Zazeela drone by simplifying his rhythmic approach was only a partial success. As Young told Kostelanetz a few years later, pure intervals are available ‘to the singer and the violin player’, though surely not to a saxophone player.Footnote 73 As the audience at Rutgers learnt, intonational difficulties would have been endemic to attempting to escape equal temperament with a sopranino saxophone.

During that same three-month gap, Conrad and Cale each added ‘cheap contact microphones, the kind […] which were available from any street corner electronics store’ to their string instruments.Footnote 74 This increased not only the volume but also the distortion and timbral blend of the ensemble. The importance of this shift in amplification and timbre cannot be overstated in considering the trajectory the ensemble carried into the next two years. Pickups and amplification allowed for more precise – though rudimentary – mixing, and moreover drew attention to the expanding presence of combination and difference tones on the rehearsal tapes.Footnote 75 This had the secondary effect of exacerbating the difficulty in distinguishing who (if anyone) was performing a given pitch audible on the tape. The ensemble’s sound was suddenly dominated by the iron triangle: the exponential, combined power of Conrad and Cale’s strings with Zazeela’s increasingly obdurate vocal drone, all compounded by amplification of their instruments’ harmonics, produced a clashing array of wildly beating timbral and psychoacoustic effects.Footnote 76 This was the beginning of the period that would later allow Cale to describe his viola as sounding ‘like a jet engine’ as a result of his flattened bridge (to bow three strings simultaneously), amplification and heavy guitar strings. ‘It became clear that if he and I droned together that there was no stopping us,’ Conrad told me; ‘that it was as powerful a sound as heavy metal.’Footnote 77

If the drone was no longer a supportive, homophonic background to Young’s saxophone virtuosity, what was it? In her essay on the Varèse–Mingus Greenwich House tapes, Brigid Cohen repeatedly asserts that because neither figure made a proprietary or autobiographical claim over the sonic labour they recorded, the tapes remained historically unmarked.Footnote 78 The ‘day of the holy mountain’ is, in contrast, a site of deep contestation over the potential of the drone it records. It marks a clear shift in Young’s original ensemble intention as a result of both technological changes and available performing forces. As part of a proleptical effort later to claim the history of the Theatre of Eternal Music as their own, Young and Zazeela inscribed the tape within the history of their work – perhaps the pre-history of their work – by giving it the alternative title ‘Pre-Tortoise Dream Music’. This title sets the ‘day of the holy mountain’ tape as a historical precedent to Young’s theoretically unending work The Tortoise, his Dreams and Journeys. In giving the tape a new name, separate from the MacLise dates used to identify most of the other tapes (that is, the specific iterations of The Tortoise, his Dreams and Journeys), Young and Zazeela draw it out of the otherwise unmarked tapes in the archive as evidence of a particular narrative thread they wanted to present on WKCR in 1984. Perhaps most significantly, thinking purely in terms of musical analysis, the tape is a testament to Young’s departure from his Coltrane- and Coleman-inspired ‘fast saxophone’ playing. Any remaining attachment to the free jazz scene had been excised – rather paradoxically in that in fully articulating the drone as the sole content of their performance practice, they also came nearer to the collectivist and egalitarian textural conceptions that gave rise to the free jazz revolution (and to Coleman’s conception of Harmolodics).

For Cale, in contrast, the tape attests to his and Conrad’s newfound successes as equals in its compositional direction, particularly as it marked a transition into the next phase of their work together. ‘Eventually we just drove La Monte off the saxophone […] so he started singing. […] To this day he refuses to acknowledge our contributions.’Footnote 79 The ‘day of the holy mountain’ tape, I contend, establishes a historiographical boundary in understanding the ensemble: for Conrad and Cale, it marks their first major victory over Young’s solitary ensemble conception (modal saxophone+drone) and is thus a movement towards the Theatre of Eternal Music collective; for Young and Zazeela, it marks another incremental step towards his ‘lifelong’ composition The Tortoise, his Dreams and Journeys and helps articulate his rational progression between stylistic territories. In marking this chiastic historical inscription, it is the most significant tape for both the institutional canonization of Young as a composer and marking the emergence of the collectivist politics of the Theatre of Eternal Music that has drawn so many artists and musicians to their sound in the last two decades.

Drones for voices+strings: the Theatre of Eternal Music 1964–5 (and 2000)

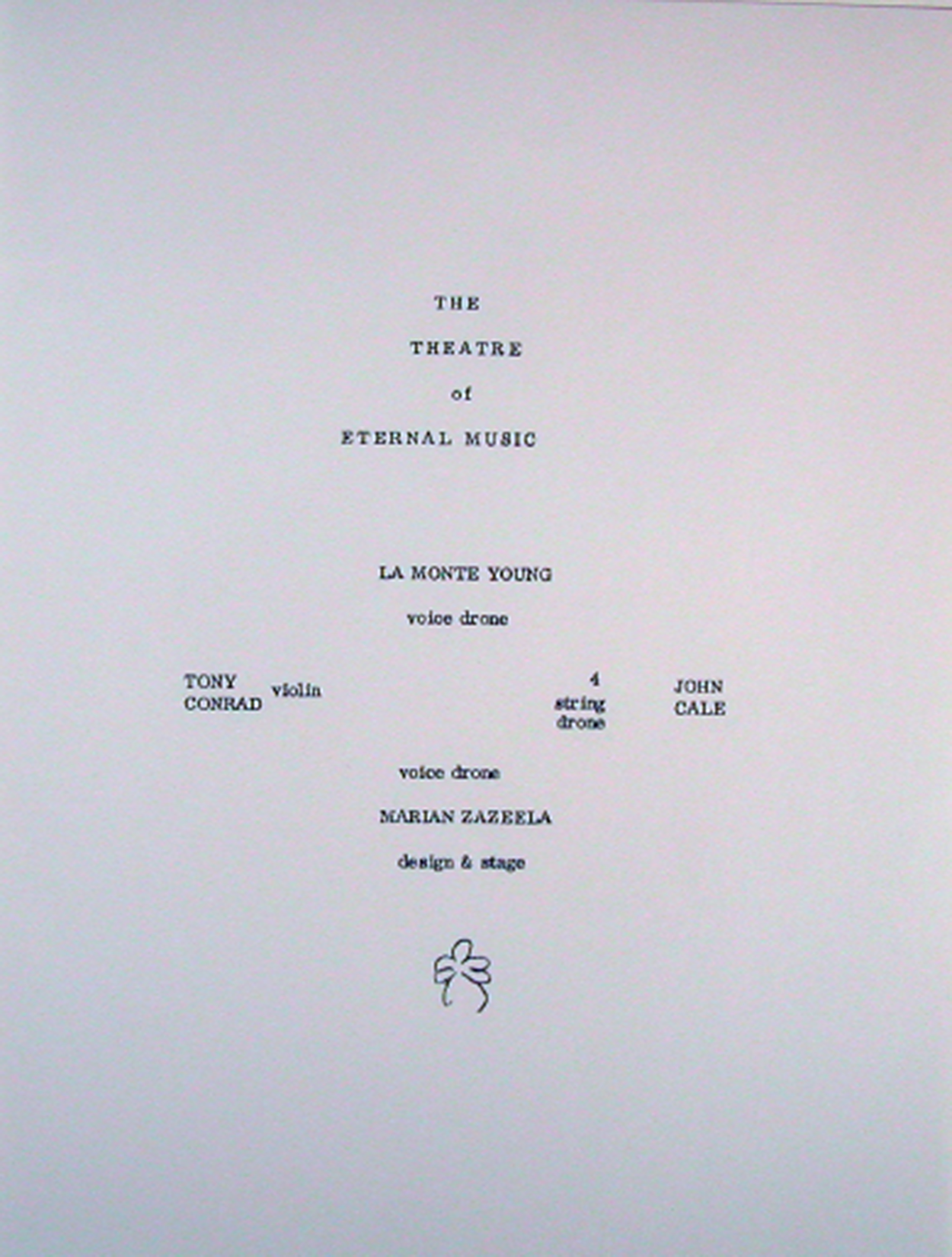

At some point in the months following April 1964, Young abandoned the saxophone and began singing as part of the drone in recognition of the new direction the ensemble had taken. There is no publicly available recording, however, of the first performances in this formation; for example, the WKCR broadcast has a gap between ‘day of the holy mountain/Pre-Tortoise Dream Music’, and the August 1966 tape The Celebration of the Tortoise. Where the audible record is silent, documentation speaks volumes. In contrast to the focus, in 1963 and 1964, on developing their practice in rehearsal, late 1964 and 1965 saw the group performing regularly around New York and the surrounding area. As Conrad’s and Cale’s choice to add contact microphones made the sound increasingly homogeneous, they raised ‘a problem [Young] never dreamed of’:Footnote 80 how to bill equally several participants in egalitarian compositional activity in a field that typically relies on the inscription of a single authorial name at the top of scores and in programmes. The inscription of collective responsibility and even collective authorship is not an issue in relation to which Western art music has traditionally excelled. As such, they had to improvise. The group came to the conclusion that their ideal of distributed and collaborative authority was best represented by graphically inscribing all four members’ names in what Young calls a ‘diamond shape’, as a means of ‘giving the musicians billing as performers with no mention of a composer’ (see Figure 1).Footnote 81 On programmes and concert announcements, Zazeela’s calligraphic inscription of the diamond visually symbolized a growing awareness of the collective’s egalitarian political and textural organization, even in the absence of audio documentation, by orienting the four names equidistant (top and bottom, left and right) from the title of the performance.Footnote 82

Figure 1 Inside cover of East End Theatre programme, 4 March 1965.

Despite their omission from the WKCR broadcast, there are two tapes from 1965 that circulate broadly. As mentioned above, in 2000 the record label Table of the Elements released Day of Niagara, the first and only commercial recording of the Theatre of Eternal Music in the quartet formation I am examining here. The release of Day of Niagara aided in complicating the history of minimalism beyond the ‘metaphysical’ narrative pervasive in the 1990s.Footnote 83 Drawn from a leaked copy of a 25 April 1965 tape recorded (and archived) in Young and Zazeela’s Church Street loft, the release drew widespread praise and enthusiasm, despite its low quality. Pitchfork described the group as the origin of all manner of experimental impulses ranging from Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music to Sonic Youth’s ongoing series of experimental EPs; another critic referred to it as ‘the most important historical release of the year’.Footnote 84 Despite the critical reception, the recording was released without permission from Young and Zazeela, leading to their public condemnation and the most focused period in the public feud over the authorial status of the drones captured on these tapes. Conrad had aspired to making his disagreement over the ensemble public since his 1990 pickets; in 2000 he delighted in telling Peter Margasak of the New York Times, ‘If I had all of these tape copies sitting on my shelf right now, you’d probably not have the advantage of all this rich discourse.’Footnote 85

The public existence of this tape points to other figures beyond Conrad and Cale who rejected Young’s secrecy. In an open letter, Dreyblatt acknowledged that he had made the copy while he was working as Young’s tape archivist from 1974 to 1976.Footnote 86 Frustrated at his inability to hear the music, and as the only person with access to the tapes, Dreyblatt made a copy for his own private listening. The tape was chosen somewhat at random: he had a Revox machine which could only play 7.5 inch per second tapes, so he chose one at hand from the archive that fit the format of what he knew to be their most important period.Footnote 87 He later gave a copy to Jim O’Rourke, who at some point turned it over to Conrad when he found out that he had not heard the music he had been involved in making. Conrad then passed it onto Jeff Hunt of Table of the Elements who, after much consideration of possible legal ramifications, released it. Day of Niagara was a major release for the revered experimental record label. ‘What really frustrated me about the whole bruhaha over Day of Niagara’, Hunt told me in 2018, ‘is that I often got the impression that nobody actually read Early Minimalism. The essays in it. Tony anticipated – correctly – and addressed all the things that you read in La Monte’s 27-page diatribe – years in advance of La Monte’s response being made public.’Footnote 88 Like Conrad in his Early Minimalism essay, Hunt is biting in his critique of Young: ‘What La Monte is most determined to assert is this role of the composer. As far as Tony was concerned they were demolishing it, and as far as La Monte was concerned, he was its epitome.’Footnote 89

Young’s open letter articulates several critiques of the release: it does not meet the high standards for recording quality and packaging that Young and Zazeela set for their work; it includes MacLise, despite the fact that he had not been taking part regularly in rehearsals at that point (and sounds as if he is having a hard time positioning his drumming in relation to the cohesive, solid voice+string drone); and the tape speed is incorrect, as evidenced by the pitch of the underlying electric drone around 82 Hz, which Young notes should sound a solid 80 Hz, a perfect fourth above the 60 Hz hum of the North American power grid.Footnote 90 For Hunt, the commercial release was a political intervention parallel to Conrad and Cale’s original insistence upon their collaborative involvement: making the tape commercially available was intended to give historical evidence and theoretical sound to Conrad’s ongoing challenge to the necessity of the role of the composer. Conrad and Cale regularly refer to the Theatre of Eternal Music as ‘the Dream Syndicate’ for this reason, calling upon the long history of syndicalist factory occupations in which workers continued production under their own autonomous organization as proof of the non-necessity of heteronomous management.Footnote 91 In much the same way, with the release of Day of Niagara Conrad and Cale polemically insisted upon their equal rights to the tapes that Young had, they suggest, locked away from both the performers and their potential listening public. In officially releasing Dreyblatt’s copied tape, Table of the Elements for the first time inserted into the public consciousness the collective sound of the Theatre of Eternal Music as a droning collective. This is the period that Young elided on WKCR, between what he calls ‘Pre-Tortoise Dream Music’ and ‘The Celebration of the Tortoise’; it is also the period during which they specifically took on the collective name, beginning in December 1964.Footnote 92

There is little to say about the recording itself. It is of extremely poor quality, even by the standards of these bootleg tapes. As Young notes, this is certainly more of a ‘rehearsal’ tape than a performance. MacLise had not been performing regularly with the ensemble at this point; a listener with little context for what this recording is would be excused for thinking his drumming was just the hissing and popping of tape noise. Cale’s strings are extremely present, stable and unwavering, and Conrad locks in tightly with him. The four regular members hold together with precision, but the tape’s most prominent feature is nevertheless its distortion and poor fidelity. While it is imperfect, I hear the shabbiness of the recording as being representative of Conrad’s rejection (shared by Cale and now also Hunt) of Young’s eternal, metaphysical articulation of not only the Theatre of Eternal Music, but also, by extension, minimalist music. That is, the tape (im)perfectly captures the sound of the ensemble as subtending something radically different from what Young’s selective tape leaks and self-narrative had suggested to date. It is more an insurrectionary political argument against Young’s concept of authorship than a strong musical statement.

The only other 1965 recording I am aware of, the ‘15 VIII 65 / day of the antler’, is one of the few tapes (along with ‘day of hummingbird night’) that I have been unable to track down ‘in the wild’, as it were, and thus whose source I cannot verify. It is also their only tape for which a score exists in public circulation.Footnote 93 Young’s choice to transcribe that tape suggests that it was a particularly accurate representation of what Young considered the group’s intended sound in 1965. Moreover, as it was included in Potter’s Four Musical Minimalists in 2000, it is very likely that Young allowed publication of the score on the grounds that, if his dispute with Conrad over authorial propriety should ever actually end up in court (a distinct possibility around the time of the release of Day of Niagara and Four Musical Minimalists), a score bearing his name and included in a book published by Cambridge University Press would offer potentially unimpeachable evidence within the burdens of proof set by American copyright.

The tape is most notable for its sustained precision: this is likely the sound that most writers imagine when they describe the group as holding an unchanging drone. Young sings relatively low, though audibly, in opposition to Conrad’s violin, which plays changing dyads over Cale’s incredibly stable viola; Zazeela’s voice is strong and present, though it becomes particularly audible when she and Conrad, operating in the same range, clash, producing a rhythmic beating. Potter describes the piece as outlining ‘an unclassifiable mode in just intonation including flattened fourths and sevenths, very flat sixths, plus very sharp fourths and sevenths’.Footnote 94 The pitches included in the score align well with those audible on the circulating recording, offering pretty solid confirmation that it is the same tape – or at least that the group had a consistent sound during the summer of 1965. The ensemble is clearly stratified throughout, with Young, Zazeela and Cale sharing eight pitches, all relations of 7, 3 or 2 to the fundamental, between 120 Hz and 320 Hz. Young and Zazeela each rock back and forth between an octave of the fundamental and a variety of just sevenths close below it. Conrad is nimbler, covering, often in double stops, eight pitches ranging in the octave from 320 Hz to 640 Hz. This tape likely represents the quartet at its performative peak in the middle of a year of numerous live performances (see Table 3). Young did not present a tape from this period on WKCR, and few circulate online. Considering the fact that he chose to transcribe this tape, it is likely that Young, too, recognizes that this is the group at its best. I contend that the relative rarity of recordings from this period attests to Young’s anxieties about presenting this sound as the work of the Theatre of Eternal Music.

Table 3 Known live performances by the Theatre of Eternal Music

| Date | Venue |

|---|---|

| 15, 22, 29 July; 5 August 1962 (afternoon & evening sets); 12, 19, 26 August 1962 | 10–4 Gallery, New York |

| 19 May 1963 | George Segal’s farm, North Brunswick, New Jersey |

| 14 June 1963 | 3rd Rail Gallery, 49 East Broadway, New York |

| 21 June 1963 | Hardware Poets Playhouse, 115 West 54 Street, New York |

| 22, 23 June 1963 | 3rd Rail Gallery |

| 27 June 1963 | Hardware Poets Playhouse |

| 19 August 1963 | The Pocket Theatre, New York |

| 27, 28, 29 September; 4, 5, 6 October 1963 | Hardware Poets Playhouse |

| 19 November 1963 | Music Activities Building, Rutgers University, New Jersey |

| 9 October 1964 | Courtyard Studio, Philadelphia College of Art |

| 30, 31 October; 1, 20, 21, 22 November; 12, 13 December 1964 | The Pocket Theatre |

| 25 February; 4 March 1965 | The East End Theatre, 85 East 4th Street, New York |

| 7 March 1965 | Home of Henry Geldzahler, New York |

| 16 October 1965 | The Theatre Upstairs, The Playhouse, Pittsburgh |

| 4, 5 December 1965 | Filmmakers’ Cinematheque, 80 Wooster Street, New York |

| 24, 25, 26, 27 February 1966 | Larry Poons’s loft, ‘The Four Heavens’, 295 Church Street, New York |

| 30 July 1966 | Christophe de Menil’s farm, Amagansett, Long Island, New York |

| 20 August 1966 | Sundance Festival, Upper Black Eddy, Pennsylvania |

The ensemble’s interaction and sounding stability in the recording makes a clear case for Conrad’s claim of leaderless collectivity. For me, the interest of this sound is its collective articulation and its organization around listening together, ‘inside the sound’, to the beating upper harmonics and working on them together. To hear this and imagine a singular composer having conceived and directed that novel practice of listening, performance method and collective interaction is to refuse to hear the granular detail of deliberative relationships developed through extensive devotion to time spent producing sound together. The goal is to listen to this as a singular sound, multiply articulated. I can readily imagine an autonomous, egalitarian collective developing this sound through deliberation, practice, time and trust; to imagine this as one person’s compositional plan instead calls me into an obfuscating space of mystification, one in which conceptual clashes are not directly considered, but evaded through the alibi of a single author.Footnote 95 This again calls upon the difference, outlined by Kwami Coleman, between polyphony and heterophony. Indeed, Coleman’s framing allows us to imagine this distinction as not only musical, but also political; this is very much how Conrad used the term heterophony in his booklet notes to Slapping Pythagoras, though for him the contrast is not with polyphony but homophony. He writes that homophony is ‘repressive’, its ‘“perfection” debases the performer’. By contrast, heterophony imagines ‘each person sounding their own voice; no blending into one; no overarching sound packaging; no universal understanding’.Footnote 96 In short, the difference between heterophony and more normative Euro-American textural ideals can be registered not only as a primary difference in the music ‘itself’, but also as a secondary difference in how one understands the organization of many voices. Hearing heterophonically means insisting on hearing the interaction of voices as multiple, equivalent, and decentralized. It means historians not starting by asking who is singularly responsible for writing what they hear.

Timbral indistinction as compositional and political principle: 1966

At different points during their tenure, Young and Conrad each described the timbral indistinction of their drones in similar language that prioritized the combined impact of high amplification, intense focus on tuning and intonation, difference tone production and ‘getting inside the sound’. In a 1966 essay, Conrad wrote, ‘After the years pass, we fail to have consciousness of the changes: the voices sound like something else, the violin is the echo of the saxophone, the viola is by day frightening rock ‘n [sic] roll orchestras, by night the sawmill.’Footnote 97 These innovations could only have come from ‘the first generation with magnetic tape, with proper amplification to break down the dictatorial sonority barriers’.Footnote 98 That same year Young told Kostelanetz, ‘There can never be any dissonance in this system, unless things get out of hand – somebody wavers, somebody misses his pitch, the machinery goes haywire.’Footnote 99 In a 13 November 1965 letter to Yates, Conrad wrote,

The only way to convert such a bewildering array of material [20 or more pitches to the octave] into a mosaic so fine that it seems nobody even changes pitch is to maintain extremely exact intonation. When overtones and especially difference tones are artificially made loud enough to contribute significantly to the total sound [via amplification], they must be kept in tune as surely as the fundamentals, or their audibly recognizable relationships will be lost in a torrent of pulsating arbitrary beat rhythms.Footnote 100

Dreyblatt used much the same language in our conversation: